Abstract

Quantum process tomography (QPT) is a crucial technique for characterizing unknown quantum channels. However, traditional QPT methods encounter scalability problems as the particle numbers increase, requiring exponentially more state preparations and measurement operators. The characteristics of sparse target channels (e.g., multiqubit phase-shift gates) can be obtained by measuring only a few specific matrix elements without requiring global QPT. Therefore, direct quantum channel characterization is vital. This paper proposes a direct protocol for both qubit and qudit systems that extracts specific process matrix elements without full reconstruction. The measurement operator requirements remain independent of system size and dimensionality. Notably, the proposed protocol uses nondestructive measurements and preserves qubits after evolution through unknown processes for potential reuse, making it uniquely promising for applications such as real-time monitoring of noise processes in quantum error correction and real-time feedback control requiring quantum state preservation. To validate the theoretical correctness of our approach, we conducted experimental demonstrations of both the unitary and non-unitary processes of single qubits using a nuclear magnetic resonance system on the SpinQ quantum cloud platform. The experimental results confirmed the correctness and effectiveness of the proposed method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum process tomography (QPT), a cornerstone technique in quantum information science, aims to characterize the dynamical evolution of quantum systems1,2,3. However, the standard QPT methods suffer from severe dimensionality challenges. As the number of particles or the dimensionality of quantum states increases, the required number of quantum-state preparations and measurement bases increases exponentially4,5, making the dynamical characterization of many-body quantum systems highly challenging. For unitary evolution processes, QPT is equivalent to characterizing the Hamiltonian that generates the evolution, i.e., Hamiltonian tomography. In recent years, a Hamiltonian tomography method based on quantum quench protocols has been developed and applied6,7. This protocol involves preparing the system in a simple initial state, allowing it to evolve under the Hamiltonian of interest, and reconstructing the Hamiltonian parameters by tracking the temporal changes of a series of local observables. This method has demonstrated its potential in systems such as ultracold atoms.

Notably, in practical applications, extracting specific matrix elements from the process matrix rather than the complete information is often sufficient. In such cases, employing standard QPT methods inevitably leads to resource inefficiency8,9,10. Therefore, developing characterization protocols capable of directly retrieving targeted matrix elements is of significant theoretical and practical importance because it can streamline the characterization workflow and enhance the efficiency of many-body quantum systems.

In the field of direct characterization, Mohseni et al.11 pioneered the direct scheme to characterize quantum dynamics, which employs auxiliary states combined with bipartite entangled basis measurements to characterize target quantum processes. Subsequently, Schmiegelow et al.12 developed selective and efficient quantum process tomography (SEQPT), which was not only successfully implemented on photonic platforms13 but also extended to arbitrary Hilbert space dimensions14. Parallel advancements have been achieved through weak-value-based characterization approaches15,16,17. Lundeen et al.18 directly measured pure-state wave functions. Pan et al.19 experimentally verified the weak-value theory using two-photon polarization states. Ren et al.20 significantly refined this method, demonstrating that the direct measurement of density matrix elements can be achieved with only a single auxiliary state and one-time coupling. This theoretical framework was subsequently generalized to characterize quantum measurement operators21 and quantum processes22. Xu et al.23 introduced a direct coherence quantification scheme for quantum measurement operators based on sequential weak-value measurements. Feng et al.24 and Wang et al.25 independently developed auxiliary-free direct quantum-state characterization methods. Notably, Kim et al.26 achieved direct quantum-process characterization via sequential weak measurements, whereas Gaikwad et al.27 proposed a protocol requiring only one auxiliary state and a pointer state to complete quantum-process measurements. Their approach offers distinct advantages, including the elimination of sequential measurements, simplification of quantum interactions, and reduction of projective measurements. Furthermore, Di Colandrea et al.28 introduced Fourier quantum process tomography, which enables the complete characterization of quantum processes with dimensions 2d (d > 0) using only seven measurements. These innovative methodologies provide new technical pathways for characterizing quantum processes.

Note that existing characterization methods based on weak-value measurements generally have two critical limitations. First, they rely on post-selection processes, resulting in the discarding of a significant number of quantum states during measurement and significantly reducing the efficiency of quantum-resource utilization. Second, these schemes are inherently destructive because the measurement process entirely destroys the target quantum qubits, rendering them unusable for subsequent quantum information processing tasks.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a direct characterization scheme for quantum processes based on non-destructive measurement. This scheme presents two distinct advantages: it completely preserves the target qubits after their evolution through an unknown quantum process, thereby offering reusable quantum resources for subsequent computational tasks; moreover, it eliminates the need for post-selection and relies on a number of projective measurements that remain independent of both the particle count and system dimensionality, highlighting its exceptional scalability. To validate the correctness of this scheme, we conducted experimental demonstrations using a single-qubit system as an example of the nuclear magnetic resonance quantum computer provided by the SpinQ quantum cloud platform. The results confirmed the correctness and practicality of the proposed method. The non-destructive direct characterization protocol proposed in this paper, with its two key features of preserving the principal quantum state and efficient measurement resource utilization, is particularly well-suited for addressing two core challenges on the path to large-scale quantum computing: quantum error correction and precise quantum control.

Results

Protocol for nondestructive direct tomography of multi-qubit channels

To directly access arbitrary matrix elements of the quantum process matrix, we propose a measurement protocol that entails performing direct measurements on the output state using a complete set of measurement operators and subsequently constructing the desired process matrix elements through linear combinations of the measured output state matrix elements. In this work, we implement a nondestructive measurement scheme to characterize the target process matrix element. The protocol involves preparing ancillary quantum states, enabling controlled system-ancilla coupling, and performing quantum state measurements on the ancilla subsystem.

The target process matrix element \({\chi }_{JK}^{MN}\) of an unknown quantum process Λ can be formally expressed as

In the above formulation, the subscripts s and a denote the target system and ancilla, respectively. We employ the eigenstates |J〉, |K〉, |M〉, and |N〉 to substitute \(|{j}_{1},\cdots {j}_{N}\rangle\), \(|{k}_{1},\cdots {k}_{N}\rangle\), \(|{m}_{1},\cdots {m}_{N}\rangle\), and \(|{n}_{1},\cdots {n}_{N}\rangle\), respectively, with \({j}_{1}\cdots {j}_{N},{k}_{1}\cdots {k}_{N}\), \({m}_{1}\cdots {m}_{N},{n}_{1}\cdots {n}_{N}\) being the binary representations of J, K, M, and N. \({\hat{\mu }}_{\beta }\) represents the projection operator acting on the ancillary qubits. Ui denotes the joint unitary evolution between the target system and ancilla. ηα corresponds to the expansion coefficients in the operator basis decomposition. \(|{\psi }_{{\rm{s}},j}\rangle\) indicates the required target input state. Here, the decomposition of \({\chi }_{JK}^{MN}\) is not unique. A good decomposition should minimize the number of measurement operators and input states as much as possible while simplifying the measurement process. To obtain a quantum circuit that non-destructively and directly characterizes a quantum process, the next step is to decompose the required specific input states and projection operators into basic quantum logic gates. Th specific input states can be obtained by applying certain quantum gates to the ground state \({|0\cdots 0\rangle }_{{\rm{s}}}\). The input states \(|{\psi }_{{\rm{s}},j}\rangle\) can always be achieved using some parameterized unitary operations, and the target quantum state can be expressed as

Similarly, the required projective measurement operator μβ can be systematically decomposed into a sequence of parameterized unitary operations, followed by projection onto the computational basis \({|0\cdots 0\rangle }_{{\rm{a}}}\langle 0\cdots 0|\), which is formally expressed as

where \({M}_{\beta }({\theta {\prime} }_{0},{\theta {\prime} }_{1}\cdots {\theta {\prime} }_{n})\) represents a parameterized unitary transformation.

The parameters \(({\theta }_{0},{\theta }_{1}\cdots {\theta }_{n})\) and \(({\theta {\prime} }_{0},{\theta {\prime} }_{1}\cdots {\theta {\prime} }_{n})\) are optimized to minimize the circuit depth. In the presented formalism, the operator \({S}_{j}({\theta }_{0},{\theta }_{1}\cdots {\theta }_{n})\) constitutes the state preparation module of the quantum circuit model, whereas \({M}_{\beta }({\theta {\prime} }_{0},{\theta {\prime} }_{1}\cdots {\theta {\prime} }_{n})\) forms the measurement module. These two fundamental components collectively establish the quantum circuit architecture for direct quantum-process characterization.

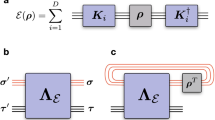

Following the aforementioned approach, we have derived the circuit scheme depicted in Fig. 1 using the specific circuit structures of the operators \({S}_{\mu }({\phi }_{1},{\theta }_{1})\) and \({T}_{\nu }({\theta }_{2},{\phi }_{2})\), as shown in Fig. 2a–f. To characterize an arbitrary N-qubit unknown quantum process, this scheme employs N auxiliary states. The target quantum state to be prepared satisfies \(|{\psi }_{{\rm{s}}}\rangle =\,\cos \,{\phi }_{1}|M\rangle +\,\sin \,{\phi }_{1}{{\rm{e}}}^{{\rm{i}}{\theta }_{2}}|N\rangle\), which can be a product, partially entangled, or fully entangled state and can be prepared using the methods illustrated in Fig. 2a–c, respectively. The operator required for the projective measurements of the N auxiliary states is \({\mu }_{\beta }=|\varPhi \rangle \langle \varPhi |\), where \(|\varPhi \rangle =\,\cos \,{\phi }_{2}{{\rm{e}}}^{-{\rm{i}}{\theta }_{2}}|J\rangle +\,\sin \,{\phi }_{2}|K\rangle\) can represent a product, partially entangled, or fully entangled state. They can be prepared using the approaches shown in Fig. 2d–f, respectively. After executing the circuit as shown in Fig. 1, the resulting projection probability \(P({\phi }_{1},{\theta }_{1},{\theta }_{2},{\phi }_{2})\) satisfies

In this scheme, both the system state and the auxiliary state are initialized to the zero state. Subsequently, the system state undergoes a state-preparation module \({\hat{S}}_{\mu }({\phi }_{1},{\theta }_{1}),\,\mu \in \{1,2,3\}\), and then passes through the target quantum process Λ. The corresponding output state is coupled with the auxiliary state through a series of controlled-NOT gates (where X represents a single-qubit NOT gate), and these controlled-NOT gates constitute a unitary process\(\hat{U}\). Afterward, the auxiliary state undergoes an evolution of \({\hat{T}}_{\nu }({\theta }_{2},{\phi }_{2}),\,\nu \in \{1,2,3\}\), and finally, the projection operator \(\hat{O}=|0\cdots 0\rangle \langle 0\cdots 0|\) is used to measure the auxiliary state and obtain the corresponding projection probabilities. By varying the values of the parameter combinations (θ1, δ1, δ2, θ2), different projection probabilities are obtained. The matrix elements of the target process are then calculated by linearly superposing these projection probabilities.

Circuit architectures for a \({\hat{S}}_{1}({\phi }_{1},{\theta }_{1})\), b \({\hat{S}}_{2}({\phi }_{1},{\theta }_{1})\), c \({\hat{S}}_{3}({\phi }_{1},{\theta }_{1})\), d \({\hat{T}}_{1}({\theta }_{2},{\phi }_{2})\), e \({\hat{T}}_{2}({\theta }_{2},{\phi }_{2})\), and f \({\hat{T}}_{3}({\theta }_{2},{\phi }_{2})\). Here, X represents a single-qubit NOT gate, which satisfies \({X}^{m}|j\rangle =|m\oplus j\rangle\), m, j ∈{0, 1), where ⊕ denotes binary addition. Ry is a single-qubit gate that rotates around the y-axis. Given an arbitrary rotation parameter ϕ2, it satisfies \({R}_{y}({\phi }_{2})=\exp (-{\rm{i}}{\phi }_{2}{\sigma }_{y}/2)\), where σy is a Pauli matrix. Rz is a single-qubit gate that rotates around the z-axis. Given an arbitrary rotation parameter θ2, it satisfies \({R}_{z}({\theta }_{2})=\exp (-{\rm{i}}{\theta }_{2}{\sigma }_{z}/2)\), where σz is a Pauli matrix. \({R}_{y}^{\dagger }\) is the Hermitian conjugate of Ry.

By strategically selecting the control parameters (ϕ1, θ1, θ2, ϕ2), we obtain distinct projection probabilities. Through appropriate linear combinations of these measured probabilities, arbitrary matrix elements of the target quantum process can be reconstructed.

For convenience, Table 1 relabels these projection probabilities as \({P}_{\mu ,\nu }^{t}({\phi }_{1},{\theta }_{1},{\theta }_{2},{\phi }_{2})\). Here, the superscript s represents the serial number of the projection probability, whereas μ, v denotes the serial number of the circuit module required for measuring the target process matrix elements (the circuit modules are illustrated in Fig. 2). Tables 2–6 present the expressions for calculating any specific matrix element (particularly the non-diagonal matrix elements of quantum processes) and the selection of parameters in the quantum circuits.

Protocol for nondestructive direct tomography of multi-qudit systems

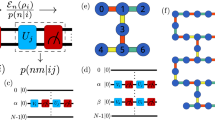

High-dimensional quantum computing improves computational complexity and security, facilitating advances in quantum communication and error correction. Fortunately, this scheme is applicable not only to multi-particle two-dimensional systems but also to multi-particle high-dimensional systems, namely, qudit systems. For measurements in high-dimensional quantum systems (e.g., photon orbital angular momentum), we need only replace the qubit quantum gates with high-dimensional qudit gates. Figure 3a illustrates the measurement circuit for the non-destructive measurement of an N-particle qudit state, with the specific circuit structures of unitary operations R1 and R2 shown in Fig. 3b, c, respectively. Here, Ud (θ1) and Ud (θ2) represent high-dimensional controlled phase-shift gates (see Fig. 4a, e). The specific circuit structures of the operators Sd,μ(ϕ1) and Td,v(ϕ2) are shown in Fig. 4b–d and f–h, respectively. The operators \({X}_{d}^{m}\) and \({R}_{d}^{\dagger }\) correspond to a high-dimensional NOT gate and rotation gate, respectively, satisfying \({X}_{d}^{n}{|m\rangle }_{d}={|m\oplus n\rangle }_{d}\) and \({R}_{y}{|0\rangle }_{d}=({|m\rangle }_{d}+{|n\rangle }_{d})/\sqrt{2}\), where \(m,n\in \{0,\cdots d-1\}\). The subscript d denotes a d-dimensional quantum system.

a Complete quantum circuit for nondestructive direct characterization of d-dimensional systems; b quantum gate of unitary operation R1; c circuit of unitary operation R2. In this scheme, both the system state and the auxiliary state are initialized to the zero state. Subsequently, the system state undergoes a state-preparation module \({\hat{S}}_{d,\mu }({\phi }_{1})\) and \({\hat{U}}_{d}({\theta }_{1})\), where the subscript d represents a d-dimensional quantum system, μ∈{1, 2, 3}, with d being the dimension of a single qudit and satisfying d > 2. Afterward, the system state passes through the target quantum process Λd. The corresponding output state is then coupled with the auxiliary state via a series of controlled-NOT gates (here, Xd denotes a single-qudit NOT gate, satisfying \({X}_{d}^{m}|j\rangle =|m\oplus j\rangle\), \(m,j\in \{0,1,\cdots d-1\}\), where ⊕ represents base-d addition). These controlled-NOT gates collectively constitute two unitary processes R1 and R2. Subsequently, the auxiliary state undergoes an evolution described by \({\hat{U}}_{d}({\theta }_{2})\), \({\hat{T}}_{d,\nu }({\phi }_{2})\), v∈{1, 2, 3}. Finally, the projection operator \(\hat{O}=|0\cdots 0\rangle \langle 0\cdots 0|\) is employed to measure the auxiliary state, and the corresponding projection probabilities are obtained. By varying the values of the parameter combinations (θ1, δ1, δ2, θ2), different projection probabilities are acquired. The matrix elements of the target process are then determined by linearly superposing these projection probabilities.

Circuit structures of a the high-dimensional controlled phase-shift operator \({\hat{U}}_{d}({\theta }_{1})\), b \({\hat{S}}_{d,1}({\phi }_{1})\), c \({\hat{S}}_{d,2}({\phi }_{1})\), d \({\hat{S}}_{d,3}({\phi }_{1})\), e the high-dimensional controlled phase-shift operator \({\hat{U}}_{d}({\theta }_{2})\), f \({\hat{T}}_{d,1}({\phi }_{2})\), g \({\hat{T}}_{d,2}({\phi }_{2})\), and h \({\hat{T}}_{d,3}({\phi }_{2})\). Here, Xd represents a single-qudit NOT gate, satisfying \({X}_{d}^{m}{|j\rangle }_{d}={|m\oplus j\rangle }_{d}\), \(m,j\in \{0,1,\cdots d-1\}\), where ⊕ denotes base-d addition. Rd represents a single-qudit rotation gate. Given an arbitrary rotation parameter ϕ1, it satisfies \({R}_{d}({\phi }_{1}){|0\rangle }_{d}=({|m\rangle }_{d}+{|n\rangle }_{d})/\sqrt{2}\). \({R}_{d}^{\dagger }\) is the Hermitian conjugate of Rd. The black dot indicates that when the control qubit is in the state |1〉, the corresponding high-dimensional operation is performed on the target qudit. If a numerical value appears above the black dot, e.g., m1, it signifies that when the control qubit is in the state |m1〉, the corresponding high-dimensional operation is executed on the target qudit.

Numerical results

To provide a more intuitive illustration of the implementation procedure of our scheme, we take the measurement of a two-qubit controlled rotation-gate C−Ry(γ) as an example and elaborate on it in Fig. 5. When the experimental objective is merely to obtain the rotation angle γ of this quantum gate, conventional full QPT is not only redundant but also highly resource-intensive. In contrast, our scheme enables the precise extraction of the target parameter by directly measuring specific process matrix elements (specifically, \({\chi }_{10,11}^{10,10}\)) that contain information about the rotation phase angle γ. Based on the formulas provided in Table 2, the real and imaginary parts of this matrix element can be fully determined using only four projective measurement probabilities.

Here, X represents a single-qubit NOT gate, Ry is a single-qubit rotation gate about the y-axis, and Rz is a single-qubit rotation gate about the z-axis. C − Ry(γ) denotes the target quantum process. After executing the quantum circuit depicted in this figure, the projection measurement \(|00\rangle \langle 00|\) is performed on the auxiliary qubit to obtain the corresponding projection probabilities. Subsequently, the target rotation angle γ is determined through a linear superposition of these probabilities.

Subsequently, we executed the circuit depicted in Fig. 5 on a quantum simulator provided by the quantum computing cloud platform. The resulting projection probabilities are shown in Fig. 6a1–a4, where the blue solid lines represent the theoretical values of the projection probabilities and the red data points denote the simulated values obtained from running the circuit on the quantum simulator. During the simulation, the number of experimental repetitions was set to 3000 to ensure sufficient iterations in obtaining more accurate simulated values. The simulated values exhibited excellent agreement with the theoretical prediction curves, and this close match validated the correctness of our proposed scheme in the experimental implementation.

Theoretical and simulated values of the projection probabilities a1 \({P}_{1,1}^{8}\), a2 \({P}_{1,1}^{12}\), a3 \({P}_{1,1}^{16}\), and a4 \({P}_{1,1}^{20}\). b Real and imaginary components of the characterized process matrix element \({\chi }_{10,11}^{10,10}\). c Comparative analysis of rotation angle extraction. In Figures (a1)–(a4), the blue solid lines represent the theoretical values of probabilities, while the red data points denote the simulated values. In Figure (b), the blue solid line and the red solid line respectively represent the theoretical values of the real and imaginary parts of the target process matrix elements. The yellow hexagrams and purple hexagrams respectively denote the simulated values of the real and imaginary parts of the target process matrix elements. In Figure (c), the blue solid line represents the theoretical values of the target rotation angles, while the red hexagrams denote the simulated values of the target rotation angles.

After the required projection probabilities are obtained, the real and imaginary parts of the target matrix element \({\chi }_{10,11}^{10,10}\) can be derived based solely on the theoretical formulas presented in Table 2 (as shown in Fig. 6b), from which the target rotation angle γ can subsequently be determined (as depicted in Fig. 6c).

Like all direct characterization schemes, our protocol is inherently sensitive to certain types of noise, particularly those that disrupt the coherence between the ancilla and the system (such as phase damping noise). Next, we take the measurement of a single-qubit gate Ry(β) on a quantum simulator platform with adjustable noise intensity as an example. Through numerical simulations, we demonstrate the functional relationship between the measurement fidelity of our scheme and the probability α of phase damping occurring. The proposed scheme can obtain the matrix elements of a single-qubit gate via projection probabilities P(0,0,0,π/2), P(0,0,π,π/2). When phase damping noise is present in each quantum gate used, the actual values of the obtained projection probabilities will deviate from their ideal values, causing the finally acquired process matrix to deviate from the ideal case.

Figure 7a–c, respectively, shows the deviations of the obtained projection probabilities P(0,0,0,π/2) and P(0,0,π,π/2) from the ideal cases (α = 0) when β = π,π/6,π/2). It can be observed that when the ideal values of both P(0,0,0,π/2) and P(0,0,π,π/2) are close to 0.5, the proposed scheme exhibits good robustness against phase damping noise, achieving a relatively high fidelity F (see Fig. 7d). However, when the ideal values of both P(0,0,0,π/2) and P(0,0,π,π/2) deviate significantly from 0.5, the proposed scheme fails to effectively resist phase damping noise, resulting in a decline in the fidelity F. In such cases, we can employ advanced error mitigation techniques to enhance the performance of the protocol on noisy quantum devices. For quantum gate errors, we can use techniques such as probabilistic error cancellation to improve the fidelity; for measurement errors, we can apply measurement error mitigation to correct the original readout results.

The functional relationship among the projection probabilities P(0,0,0,π/2), P(0,0,π,π/2), and the probability α of phase damping noise occurrence when a β = π, b β = π/6, c β = π/2. d The functional relationship between the fidelity F and the probability α of phase damping noise occurrence. In Figures (a–c), the blue hexagrams represent the simulated values of the probability P(0,0,0,π/2), while the red pentagrams also represent the simulated values of the probability P(0,0,π,π/2). In Figure (d), the blue pentagrams, black hexagrams, and red diamonds respectively represent the fidelities of reconstructing the target process matrix using the proposed scheme when the angles of single-qubit rotation gates are set to β = π/6, π/2,π. It can be observed that when the ideal values of both P(0,0,0,π/2) and P(0,0,π,π/2) are close to 0.5, the proposed scheme exhibits good robustness against phase damping noise, achieving a relatively high fidelity F. However, when the ideal values of both P(0,0,0,π/2) and P(0,0,π,π/2) deviate significantly from 0.5, the proposed scheme fails to effectively resist phase damping noise, resulting in a decline in the fidelity F.

Theoretical principle comparison: Interferometric QPT, ancilla-assisted QPT, classical shadows, and other characterization methods

Interferometric/auxiliary-system-assisted QPT29 belong to full quantum process characterization schemes. Even when we only need to obtain one or a few process matrix elements, using these full characterization schemes still requires reconstructing the entire process matrix to acquire the specific matrix elements. These schemes obtain full information by jointly measuring the system and auxiliary qubits, which is destructive. Classical shadow methods adopt a universal framework of “comprehensive sampling first, followed by classical answers”, with the advantage of answering multiple different questions about a process from a single dataset.

Compared to interferometric/auxiliary-system-assisted QPT, our scheme non-destructively infers arbitrary process matrix elements by only measuring an auxiliary system. This realizes a paradigm shift in measurement. Compared to classical shadow methods, our scheme follows a direct route "tailored to specific problems", with the advantage of achieving the highest measurement efficiency and quantum state preservation capacity when scientific questions focus on a few specific matrix elements. Our scheme is a resource-optimal specialized tool, while classical shadow methods are functionally comprehensive universal tools.

Compared with existing direct quantum process characterization schemes, we have creatively integrated the core design principle of "measuring only auxiliary qubits" with the objective of "directly extracting process matrix elements," resulting in a quantum process characterization protocol that simultaneously exhibits the following features: non-destructiveness, the absence of post-selection, constant-scaling measurement resources, and universality for both unitary and non-unitary processes.

Existing schemes typically can only incorporate one or two of these advantages. For instance, the schemes by Mohseni/Schmiegelow11,12 are efficient and do not require post-selection but are destructive. Weak-value schemes26,27 rely on post-selection and are inefficient. Our scheme is specifically designed to address these remaining challenges simultaneously. It does not merely make minor improvements but instead offers a new pathway that is more advantageous in terms of resource utilization and quantum state preservation. The content of this comparison is presented in the Table 7, accompanied by detailed textual discussions.

Comparison of measurement resources with existing direct characterization protocols

SEQPT proposed by Schmiegelow et al.12 significantly influenced the development of QPT. This method requires the preparation of quantum states that constitute a two-design state set. It involves sequentially evolving the quantum states through a reference process and a target process, and finally projecting them onto the initial state for measurement. Notably, this method requires up to 240 measurement readouts for a two-qubit system. To optimize this scheme, Gaikwad et al.30 proposed a modified, selective, and efficient quantum process tomography (MSEQPT) method, and successfully implemented it in a nuclear magnetic resonance system. The improved scheme enhances the efficiency. MSEQPT enables the measurement of a two-qubit system that requires only 15 state preparations and 60 readouts, significantly reducing the experimental complexity. The weak-value scheme proposed by Zhang et al.22 adopts a different technical approach. Although this scheme requires only 16 readouts, it requires a post-selection process and additional resources in the form of four auxiliary quantum states. Each of these methods has unique characteristics that offer a diverse range of technical options for quantum process characterization. As for quantum quench protocol6,7, it requires the system to undergo continuous evolution over a period of time and indirectly infers Hamiltonian parameters by fitting the temporal curves of observables. The number of measurements required is typically related to the interaction range, but for local Hamiltonians, its scaling may be superior to traditional QPT. However, it necessitates high temporal resolution measurements and potentially complex curve fitting. The quantum quench protocol requires time tracking of multiple observables. Each observable may necessitate dozens or even hundreds of time points to capture its dynamic behavior and achieve sufficient fitting accuracy. Consequently, the total number of readouts (i.e., the total number of measurement sampling points) can easily reach the order of hundreds. The standard quantum quench protocol does not require any auxiliary qubits. It directly performs state preparation, time evolution, and final measurement on the system under test itself. It involves destructive measurements. Each projective measurement conducted at a specific time point completely collapses the quantum state of the system.

Next, we will elaborate in detail on the number of projection probabilities required by our scheme to obtain a specific matrix element. For an arbitrary N-qubit system, the number of projection probabilities needed varies depending on the mathematical form of the target process matrix elements.

Measuring the diagonal matrix elements \({\chi }_{J,K}^{M,N}(M=N,J=K)\) of the process matrix is relatively straightforward, as it only requires projection measurements using the corresponding single eigenbasis vector. The main challenge lies in measuring the real and imaginary parts of the off-diagonal elements. The number of projection probabilities required to obtain off-diagonal elements with different mathematical forms varies. For the measurement of process matrix elements such as \({\chi }_{J,K}^{M,N}(M=N,J\ne K)\) and \({\chi }_{J,K}^{M,N}(M\ne N,J=K)\), only 4 projection probabilities are needed for each matrix element. The specific projection probabilities required are listed in the left or right columns of the last row in Tables 2, 3, and 4, respectively. For example, when the target matrix element is \({\chi }_{J,K}^{M,N}(M=N,J\ne K)\), only 4 projection probabilities (e.g., P1, P2, P3, P4 or P21, P22, P23, P24) are needed. For the measurement of the real and imaginary parts of \({\chi }_{J,K}^{M,N}(M\ne N,J\ne K)\), 16 projection probabilities are required for each matrix element. The specific projection probabilities required are listed in the last row of Tables 5 and 6, respectively. From the above, it can be seen that, depending on the specific mathematical form of the target matrix element to be obtained, our scheme requires at most 16 projection probabilities to obtain any single matrix elements (as detailed in Table 8). Since our scheme is independent of the system size and the particle dimension d when acquiring a specefic process matrix, the number of projection probabilities (or the number of measurement bases) required has a complexity of O(1) with respect to both the number of qubits N and the qubit dimension d.

To further clarify the number of projection probabilities, we will use the measurement of a two-qubit quantum process as an example (with a total of 256 process matrix elements) to illustrate the required number of projection probabilities.

For the measurement of the diagonal elements of a two-qubit process, only one corresponding eigenbasis is needed to obtain each of the 16 diagonal elements. Thus, a total of 16 projection probabilities are required. Regarding the measurement of off-diagonal elements that satisfy the mathematical form \({\chi }_{J,K}^{M,N}(M\ne N,J\ne K)\), there are 144 matrix elements that fit such forms. Acquiring each of these matrix elements requires 16 projection probabilities. Therefore, the total number of projection probabilities needed to fully measure these matrix elements is 16 × 144 = 2304. For the remaining matrix elements, each of which requires only 4 projection probabilities, there are 96 such elements. Hence, the number of projection probabilities needed to measure these matrix elements is 4 × 96 = 384. Finally, leveraging the Hermitian property of the process matrix elements, the total number of projection probabilities required to fully acquire the two-qubit process matrix elements using our direct characterization method can be simplified as 1 × 16 + 16 × 144/2 + 4 × 96/2 = 1360. As the number of qubits N and the qubit dimension d increase, although the number of measurement bases required to obtain a single process matrix element remains constant, the total number of matrix elements contained in the process matrix grows exponentially. Consequently, if a direct characterization scheme is employed to obtain the entire process matrix, the number of measurement bases R required also increases exponentially, i.e., R = O(d4N). It may seem that using the direct characterization method (including all existing schemes and our scheme) to fully characterize the process matrix requires more projection probabilities than Standard QPT. But it should be emphasized that the advantage of the direct characterization method lies in acquiring one or a few process matrix elements, rather than in fully acquiring the entire process matrix.

Compared with existing approaches, the quantum circuit scheme proposed in this paper demonstrates significant advantages in terms of resource utilization and measurement efficiency. In particular, when acquiring the specific process matrix elements of two-qubit systems, our scheme only requires the introduction of two auxiliary quantum states and involves a maximum of 16 measurement readouts. Notably, the measurement complexity of this scheme is dimension-independent, meaning that the required number of measurements does not increase with an increase in the number of particles or dimensionality of the Hilbert space in the quantum system. More groundbreaking is the fact that our scheme enables non-destructive measurements, a feature that makes it perfectly suited to satisfy the stringent requirements for quantum state preservation in fields such as quantum error correction and quantum control. To illustrate the advantages of our scheme visually, Table 9 provides a comparative analysis of our scheme and existing representative approaches using a two-qubit system as an example. These comparative results fully substantiate the remarkable superiority and application potential of our scheme for the characterization of multi-qubit systems.

We provide an approximate discussion on the comparison of statistical errors between existing characterization schemes (mainly including SEQPT and weak-value-based schemes) and our proposed scheme.

As for the proposed scheme, we take the quantum process of a single-qubit system as an example and present the mathematical expressions for the measurement variances of the real and imaginary parts of a specific matrix element \({\chi }_{jk}^{mn}\), as shown in "Method" section, by utilizing error transformation formulas. These formulas indicate that the statistical errors of the real and imaginary parts of the matrix element are related to its own value. In these formulas, W represents the number of measurement samples. A larger sample number leads to smaller statistical errors. It is worth mentioning that since our measurement scheme is independent of the system size and the dimension of the Hilbert space, the statistical errors of the measurement results are also independent of the system size and the dimension of the Hilbert space. The statistical error of the proposed scheme is proportional to \(\sqrt{1/W}\). In other words, to ensure that the statistical error remains within ε, the required number of samples W must satisfy W = O(1/ε2).

For SEQPT schemes, the number of measurement readouts is O(D2), where D is the dimension of the system's Hilbert space. Thus, when the total number of measurement samples is W, the average number of samples allocated to each measurement readout is approximately W/D2. Consequently, the statistical error associated with each measurement readout is \(\varDelta \chi \propto \sqrt{{D}^{2}/W}\). With a fixed total sample size W, the number of samples available for measuring each readout decreases, leading to an increase in the statistical error for each measurement readout result. In contrast, for our scheme, the number of measurement readouts required is fixed and independent of the system's Hilbert space dimension. Our scheme requires a maximum of only 16 measurement readouts (or projection probabilities). Therefore, our scheme exhibits lower statistical errors when characterizing systems composed of large-scale particles compared to SEQPT schemes.

Regarding the weak-value-based characterization scheme, it necessitates post-selection, where only samples meeting the selection criteria are measured. This implies that a portion of the measurement samples is discarded. When the total number of measurement samples is W, the actual number of samples used for statistical measurement is WPf (where Pf is the post-selection probability, satisfying Pf < 1. Consequently, the statistical error \(\varDelta \chi \propto \sqrt{1/W{P}_{f}}\). Our scheme eliminates the post-selection process. Therefore, the statistical error of our scheme is improved by at least a factor of \(\sqrt{1/{P}_{f}}\) compared to the weak-value-based scheme. Additionally, the number of measurement readouts required by the weak-value scheme increases polynomially, whereas the number of readouts in our scheme is independent of the system's Hilbert space dimension. This further reduces the statistical error in our scheme.

Experimental demonstration

This section presents the experimental validation of the proposed scheme using the SpinQ quantum computing cloud platform, focusing on single-qubit unitary and non-unitary processes. The nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) quantum computing system provided by this cloud platform supports the user-defined design and verification of quantum circuits. It should be emphasized that we employ an NMR system as the experimental platform and only verify the correctness of the circuit architecture by measuring auxiliary states, rather than validating the single-shot non-destructive measurement. We select a two-qubit system (utilizing a chloroform molecule as the physical substrate, with the carbon atom serving as the target qubit Q0 and the hydrogen atom serving as the auxiliary qubit Q1) to validate the characterization scheme for single-qubit unitary processes.

As depicted in the experimental platform shown in Fig. 8a and the quantum circuit shown in Fig. 8b, our scheme achieves direct measurements through the following steps: First, rotation and phase-shift operations are applied to the target qubit Q0. Next, the unitary gate U is implemented as the target quantum process, satisfying

a Molecular model of chloroform; b Circuit structure of measurement performed solely on the ancillary system for a single-qubit unitary quantum process. Here, C represents the target qubit; H represents the auxiliary qubit; U denotes the target unitary process; C-NOT stands for the two-qubit controlled-NOT gate. Ry and Rz represent single-qubit controlled rotation gates about the y-axis and z-axis, respectively; M signifies the measurement process. After executing the circuit depicted in Figure (b), the projection measurement \(|0\rangle \langle 0|\) is performed to obtain projection probabilities. By adjusting the rotation angles of Ry and Rz, different projection probabilities are acquired. The matrix element \({\chi }_{0,0}^{0,1}\) of the target process is then determined through a linear superposition of these probabilities.

Then, coupling interactions between Q0 and Q1 are established. Afterward, phase-shift and rotation operations are performed on the auxiliary qubit Q1. Finally, projective measurements are executed on Q1.

Notably, when measuring the specific matrix element \({\chi }_{0,0}^{0,1}\), only four projective probability measurement values are required to accurately extract the real and imaginary parts of the matrix element based on the conversion relationships listed in Table 3. This streamlined measurement scheme demonstrates the high efficiency and practicality of the proposed method. Experimental results indicate that this scheme accurately characterizes quantum processes.

Figure 9a, b presents a comparison between the experimental data and theoretical predictions. The blue solid lines represent the theoretically calculated values, whereas the red data points denote the experimental measurement results obtained using the SpinQ cloud platform. To ensure the reliability of the experimental results, we subjected each data point to four independent repeated measurements and calculated the statistical mean and standard deviation (depicted as error bars) calculated accordingly. The experimental observations exhibited excellent agreement with the theoretical prediction curves, and this close match validated the correctness of our proposed scheme in the experimental implementation. Notably, all measured data points were within a reasonable deviation range, as theoretically anticipated. This outcome not only confirms the accuracy of the theoretical model but also demonstrates the feasibility of the experimental approach.

Theoretical and experimental values of projection probabilities a P1 and P2 and b P3 and P4. c The functional relationships between the real and imaginary components of the target process matrix elements with respect to the parameter δ. In Figures (a, b), the solid lines denote theoretical values, while the data points correspond to experimental values. In Figure (c), the blue solid and red solid lines respectively represent the theoretical values of the real and imaginary parts of the target process matrix element \({\chi }_{0,0}^{0,1}\), with the experimental data points indicating the experimentally measured values. The red area represents the 95% confidence interval of the theoretically predicted values. Here β = π/2, γ = 0.

Figure 9c presents a comparison between the experimentally measured results and theoretical predictions for the real and imaginary parts of the target process matrix element, \({\chi }_{0,0}^{0,1}\). The blue solid lines represent the theoretical calculation curves, the red data points denote the experimental measurement values (each data point was obtained by averaging four independent repeated measurements, and the error bars indicate the standard deviation).

To validate the applicability of our scheme in characterizing non-unitary quantum processes, we conducted further experimental verification using a three-qubit system on the SpinQ cloud platform (with trichloroethylene molecules serving as the physical substrate). The specific configuration of the experimental platform is illustrated in Fig. 10a, where the 1H nuclear spin acts as an auxiliary qubit, 13C2 nuclear spin serves as the target qubit, and 13C1 nuclear spin is employed to simulate environmental noise.

a Molecular model of trichloroethylene; b Circuit structure of measurement performed solely on the ancillary system for single-qubit non-unitary quantum processes. C1 represents the environmental qubit; C2 denotes the target qubit; H stands for the auxiliary qubit; Λ(γ) represents the target non-unitary process; C-NOT signifies the two-qubit controlled-NOT gate. Ry and Rz represent single-qubit controlled rotation gates about the y-axis and z-axis, respectively; M indicates the measurement process. After executing the circuit depicted in Figure (b), the projection measurement \(|0\rangle \langle 0|\) is performed to obtain projection probabilities. By adjusting the rotation angles of Ry and Rz, different projection probabilities are acquired. The matrix element \({\chi }_{0,0}^{0,1}\) of the target process is then determined through a linear superposition of these probabilities.

As illustrated by the quantum circuit in Fig. 10b, the experimental procedure begins with an initial rotation and phase modulation applied to the target qubit. This is followed by the introduction of a controllable amplitude damping channel, where the parameter γ corresponds to the amplitude damping probability, implemented via coupling with an environmental qubit. Subsequently, coherent coupling is established between the auxiliary and target qubits, and the process concludes with a final rotation and projective measurements carried out on the auxiliary qubit.

Taking the characterization of the specific matrix element \({\chi }_{0,0}^{0,1}\) as an example, a comparison between the experimental data and theoretical predictions verifies the correctness of the scheme. Notably, this scheme successfully achieves the precise characterization of non-unitary processes, thereby providing a novel experimental tool for the study of open quantum systems.

Figure 11a1–a4, respectively, displays the experimentally obtained projection probabilities and their theoretical counterparts. The solid blue lines represent the theoretical values and the red scattered points denote the experimental data. Each data point was measured four times and the mean values and variances were calculated. Within the allowable margin of error, the experimental values were generally consistent with the theoretical predictions, thereby demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed scheme. Figure 11b, c systematically shows the experimental characterization results of the real and imaginary parts of the non-unitary process matrix element \({\chi }_{0,0}^{0,1}\). The solid blue lines represent the theoretically predicted values and the red data points denote the experimental measurement results. Notably, this scheme achieves high-precision measurements of the complex matrix elements of non-unitary processes, marking a breakthrough that provides a new experimental paradigm for the precise characterization of open quantum systems.

Theoretical and experimental values of the projection probabilities a1 P2, a2 P3, a3 P1, and a4 P4. b Real part of the target matrix element\({\chi }_{0,0}^{0,1}\). c Imaginary part of the target matrix element \({\chi }_{0,0}^{0,1}\). Here, the solid lines represent theoretical values, and the data points denote experimental values. The red area denotes the 95% confidence interval of the theoretically predicted values. Notably, the width of the confidence interval for the theoretical value of probability P1 is zero.

In NMR-based quantum computing experiments, the observed deviations between theoretical and experimental values, along with the relatively large error bars, primarily stem from some inevitable experimental non-idealities. Although the SpinQ platform achieves an average single-qubit gate fidelity of 99%, the fidelity of two-qubit gates (e.g., controlled-phase gates) ranges from 95% to 98%. The non-unitary process characterization circuit depicted in Fig. 11 involves multiple quantum gate operations, and these gate errors accumulate and propagate through the circuit, causing the final projected measurement probability distribution to deviate from the ideal theoretical expectations.

Energy relaxation (T1) and phase relaxation (T2) processes in quantum systems lead to the decay of quantum state information over time. The preparation, evolution, and measurement of quantum states in experiments all require a certain amount of time. During this process, particularly in three-qubit systems (used for non-unitary process characterization), relaxation effects introduce significant signal attenuation and phase shifts, thereby increasing measurement fluctuations and systematic biases.

Quantum state readout on NMR platforms is subject to measurement errors, including shot noise and electronic noise. These noise sources introduce uncertainties in the estimation of projection probabilities, which are reflected as error bars in the data points. We calculate the mean and standard deviation from four independent repeated measurements, and these error bars represent the statistical fluctuations of the measurement results.

Despite the deviations of individual data points from the theoretical curves, the overall distribution of experimental data points (red scatter points) clearly follows the variation pattern of the theoretical prediction curves (blue solid lines). This indicates that our theoretical model effectively captures the essential characteristics of the quantum process, and the experimental scheme is conceptually correct and feasible. The relatively large error bars, which cover a significant portion of the probability range, are primarily attributable to the systematic biases introduced by gate errors and relaxation effects over multiple experimental runs, as well as the statistical fluctuations caused by measurement noise. Additionally, circuits for characterizing non-unitary processes (involving environmental coupling) are typically more complex than those for unitary processes and are more sensitive to environmental noise and parameter fluctuations, further amplifying the fluctuation range of experimental results.

Discussion

This paper proposes a non-destructive direct characterization scheme for quantum processes. This enables the preservation of quantum states evolved through unknown processes, facilitating their reuse in subsequent tasks, and thereby laying the foundation for measuring quantum processes in quantum error correction and quantum control. The design philosophy of our scheme paves the way for realizing non-destructive characterization on experimental platforms capable of manipulating individual particles (such as single-photon polarization qubits, superconducting qubits, and other physical systems).

In quantum error correction, continuous measurement of qubits is required to diagnose errors without destroying the stored logical quantum information. Traditional measurement schemes are destructive. Our non-destructive characterization protocol offers a viable technical pathway to achieve this goal. By treating the stabilizer operators or noise channels in quantum error correction codes as the quantum processes to be characterized, our scheme can directly extract noise intensity information without disrupting the quantum state of the data qubits, thereby laying the foundation for implementing non-destructive error correction cycles.

In quantum feedback control, real-time monitoring of a quantum system's state and real-time adjustment of control parameters based on measurement results are essential. The "non-destructive" nature of our scheme allows the principal quantum state to be preserved after characterization, enabling it to be immediately used for subsequent computational steps or control operations. For example, in variational quantum algorithms, our scheme can non-destructively monitor the fidelity of specific quantum gates and provide feedback to optimize parameters accordingly, without the need for frequent re-preparation of the initial state. This significantly enhances learning efficiency and resource utilization.

Note that during the characterization experiments based on the quantum circuit model, the system inevitably suffers from the effects of quantum gate operation errors and projective measurement errors. We can adopt a systematic error-mitigation scheme to address these two types of errors. For quantum-gate operation errors caused by decoherence effects, the probabilistic error cancellation algorithm31 can be employed for correction. By accurately modeling the gate noise and constructing and applying inverse noise operations within the circuit, we can effectively increase the gate operation fidelity to above 99%. Regarding projective measurement errors, measurement error mitigation techniques32,33 to construct an error confusion matrix. Matrix inversion methods can then be used to correct the raw measurement results, thereby reducing the measurement error by an order of magnitude. By integrating high-performance quantum hardware with software post-processing algorithms, a comprehensive error-suppression system was established. This "hardware–software" collaborative optimization-based error-mitigation strategy provides a novel technical paradigm for quantum process characterization.

Methods

Mathematical relationship between the process matrix elements and the state density matrix

The characterization of multi-qubit quantum channels can be fundamentally decomposed into the preparation of specific quantum states, followed by a linear combination of projective measurements. Specifically, these state preparation and measurement operations can be implemented using appropriate combinations of single-qubit and multi-qubit gates.

To establish a quantum circuit theoretic model for direct quantum process characterization, we first decompose the target process matrix elements into linear superpositions of specific input states and projective measurement outcomes. Consider an N-qubit system whose dynamical evolution can be described by the following fundamental equation:

In the above expression, ρs and ρout denote the input and output states, respectively, and lrepresents a positive integer. The operator Kl is expanded using the basis vectors \(\{|{j}_{1},\cdots {j}_{N}\rangle \langle {m}_{1},\cdots {m}_{N}|\}\), where \({j}_{1},\cdots {j}_{N},{m}_{1},\cdots {m}_{N}\in \{0,1\}\). For notational convenience, we employ \(\{|J\rangle \langle M|\}\) to substitute \(\{|{j}_{1},\cdots {j}_{N}\rangle \langle {m}_{1},\cdots {m}_{N}|\}\), with \({j}_{1}\cdots {j}_{N},{m}_{1}\cdots {m}_{N}\) being the binary representation of J,M. The explicit form of Kl is given as follows:

In the above expression, \({e}_{JM}^{l}\) represents the matrix element of the operator Kl. The superoperator Λ(ρs) can be expressed as follows:

For notational simplicity, we employ \(\{|K\rangle \langle N|\}\) to denote \(\{|{k}_{1},\cdots {k}_{N}\rangle \langle {n}_{1},\cdots {n}_{N}|\}\), where \({k}_{1}\cdots {k}_{N},{n}_{1}\cdots {n}_{N}\) represents the binary encoding of K, N. In this framework, the superoperator Λ(ρs) can be formally represented by a process matrix \({\boldsymbol{\chi }}=\{{\chi }_{JK}^{MN}\}\). Notably, \({\boldsymbol{\chi }}\) constitutes a Hermitian matrix, whose explicit form is derived from the above Equation.

Mathematical expression of statistical error

In this section, we take the quantum process of a single-qubit system as an example and present the mathematical expressions for the measurement variances of the real and imaginary parts of a specific matrix element \({\chi }_{jk}^{mn}\), as shown below, by utilizing error transformation formulas. These formulas indicate that the statistical errors of the real and imaginary parts of the matrix element are related to its own value. In these formulas, W represents the number of measurement samples. A larger sample number leads to smaller statistical errors.

Experimental platform

This study employed the SpinQ quantum cloud platform to conduct a preliminary experimental validation of the proposed quantum circuit model. This platform offers an NMR experimental setup with 2 and 3 qubits and a 24-qubit quantum simulator. For the NMR system provided by this cloud platform, the average fidelity of single-qubit gates reaches 99%, whereas the average fidelity of two-qubit gates (such as the controlled phase-shift gate) remains consistently between 95% and 98%. Additionally, the quantum system on this cloud platform features a relatively long decoherence time, with a longitudinal relaxation time T1 on the order of 1 s and a transverse relaxation time T2 typically around 10 ms.

The NMR quantum computing architecture available through this cloud platform enables the custom design and experimental validation of quantum circuits. To verify our single-qubit unitary process characterization protocol, we employed a two-qubit system (based on a chloroform molecule, with the carbon nucleus functioning as the target qubit Q0 and the hydrogen nucleus serving as the auxiliary qubit Q1).

To assess the capability of the scheme to characterize non-unitary quantum operations, we extended the experimental validation to a three-qubit configuration on a SpinQ platform (utilizing trichloroethylene molecules as the physical system). The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 10a. The 1H nuclear spin served as an auxiliary qubit. A 13C2 nuclear spin was designated as the target qubit, and a 13C1 nuclear spin was incorporated to emulate environmental noise. The operational sequence, as outlined in the quantum circuit of Fig. 10b, begins with initial state preparation involving rotation and phase calibration of the target qubit. This is followed by the implementation of a tunable amplitude damping channel, parameterized by γ which is proportional to the damping probability, through environmental qubit coupling. Subsequently, a coherent interaction is established between the auxiliary and target qubits, and the procedure concludes with a final rotation of the auxiliary qubit and its subsequent projective measurement.

This structured experimental framework enables systematic investigation of both unitary and non-unitary quantum process characterization methodologies.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ahmed, S., Quijandría, F. & Kockum, A. F. Gradient-descent quantum process tomography by learning Kraus operators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 150402 (2023).

Torlai, G. et al. Quantum process tomography with unsupervised learning and tensor networks. Nat. Commun. 14, 2858 (2023).

Levy, R., Luo, D. & Clark, B. K. Classical shadows for quantum process tomography on near-term quantum computers. Phys. Rev. Res 6, 013029 (2024).

Gorlach, A. et al. Photonic quantum state tomography using free electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 250801 (2024).

Lundeen, J. et al. Tomography of quantum detectors. Nat. Phys. 5, 27–30 (2009).

Li, Z., Zou, L. & Hsieh, T. H. Hamiltonian tomography via quantum quench. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 160502 (2020).

Cole, J. H. Hamiltonian tomography: the quantum (system) measurement problem. N. J. Phys. 17, 101001 (2015).

Huang, Y. et al. Direct entanglement detection of quantum systems using machine learning. NPJ Quantum Inf. 11, 29 (2025).

Leone, L., Oliviero, S. F. E. & Hamma, A. Nonstabilizerness determining the hardness of direct fidelity estimation. Phys. Rev. A 107, 022429 (2023).

Qin, H. et al. Experimental direct quantum fidelity learning via a data-driven approach. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 190801 (2024).

Mohseni, M. & Lidar, D. A. Direct characterization of quantum dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 170501 (2006).

Schmiegelow, C. T., Bendersky, A., Larotonda, M. A. & Paz, J. P. Selective and efficient quantum process tomography without ancilla. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 100502 (2011).

Schmiegelow, C. T., Larotonda, M. A. & Paz, J. P. Selective and efficient quantum process tomography with single photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 123601 (2010).

Perito, I., Roncaglia, A. J. & Bendersky, A. Selective and efficient quantum process tomography in arbitrary finite dimension. Phys. Rev. A 98, 062303 (2018).

Aharonov, Y., Albert, D. Z. & Vaidman, L. How the result of a measurement of a component of the spin of a spin-1/2 particle can turn out to be 100. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 1351 (1988).

Wagner, R. et al. Quantum circuits for measuring weak values, Kirkwood-Dirac quasiprobability distributions, and state spectra. Quantum Sci. Technol. 9, 015030 (2024).

Yang, G., Yang, R., Gong, Y. X. & Zhu, S. N. Direct measurement of nonlocal quantum states without approximation. Chin. Phys. B 32, 110306 (2023).

Lundeen, J. S., Sutherland, B., Patel, A., Stewart, C. & Bamber, C. Direct measurement of the quantum wavefunction. Nature 474, 188–191 (2011).

Pan, W. et al. Direct measurement of a nonlocal entangled quantum state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 150402 (2019).

Ren, C., Wang, Y. & Du, J. Efficient direct measurement of arbitrary quantum systems via weak measurement. Phys. Rev. Appl 12, 014045 (2019).

Xu, L. et al. Direct characterization of quantum measurements using weak values. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 180401 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Zhu, X., Wu, S. & Chen, Z. Direct quantum process tomography with coupling-deformed pointer observables. Ann. Phys. 378, 13–23 (2017).

Xu, L. et al. Direct characterization of coherence of quantum detectors by sequential measurements. Adv. Photon. 3, 066001 (2021).

Feng, T., Ren, C. & Zhou, X. Direct measurement of density-matrix elements using a phase-shifting technique. Phys. Rev. A 104, 042403 (2021).

Wang, Z., Zhang, Z. & Zhao, Y. Direct measurement for general quantum states using parametric quantum circuits. Commun. Theor. Phys. 75, 010501 (2023).

Kim, Y. et al. Direct quantum process tomography via measuring sequential weak values of incompatible observables. Nat. Commun. 9, 192 (2018).

Gaikwad, A., Singh, G., Dorai, K. & Arvind. Direct tomography of quantum states and processes via weak measurements of Pauli spin operators on an NMR quantum processor. Eur. Phys. J. D. 77, 209 (2023).

Di Colandrea, F., Dehghan, N., D’Errico, A. & Karimi, E. Fourier quantum process tomography. NPJ Quantum Inf. 10, 49 (2024).

Altepeter, J. B. et al. Ancilla-assisted quantum process tomography. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 193601 (2003).

Gaikwad, A., Rehal, D., Singh, A., Arvind & Dorai, K. Experimental demonstration of selective quantum process tomography on an NMR quantum information processor. Phys. Rev. A 97, 022311 (2018).

Temme, K., Bravyi, S. & Gambetta, J. M. Error mitigation for short-depth quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 180509 (2017).

Bravyi, S., Sheldon, S., Kandala, A., Mckay, D. C. & Gambetta, J. M. Mitigating measurement errors in multiqubit experiments. Phys. Rev. A 103, 042605 (2021).

Cai, Z. et al. Quantum error mitigation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 045005 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support from Zhongyuan University of Technology and Harbin Institute of Technology. This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhongyuan University of Technology (grant no. K2026YB002) and Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (grant no. 62075049).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Wang wrote the main manuscript text. Q. He and Z. Zhang conducted verification and revision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., He, Q. & Zhang, Z. Efficient non-destructive direct characterization of arbitrary many-body quantum channels. npj Quantum Inf 12, 11 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01153-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01153-3