Abstract

Absorption and emission, fundamental interactions between light and matter, enable the regeneration of a quantum state of light via matter through concatenated quantum state transfer based on the principle of quantum teleportation. This transfer is enabled by electron spin-orbit entanglement and electron-nuclear spin entanglement inherent within the material. Here, we demonstrate that a photon quantum state imprinted in polarization is transferred to another photon emitted from a nitrogen vacancy (NV) center. This transfer is heralded by the result of the Bell state measurement between the electron and nitrogen nuclear spins. We show that the minimum number of incident photons needed to achieve transfer is, on average, only 0.1 photons, enabling quantum teleportation over 10 km. This demonstration paves the way for a quantum repeater that is robust against phase and intensity errors, unlike the conventional photon interference scheme, thereby facilitating practical quantum networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Remote quantum entanglement is essential not only for demonstrating the nonlocal nature of quantum correlations1,2 but also as a key resource for practical applications, such as quantum repeaters, based on the principle of quantum teleportation3. Recent advances have enabled the demonstration of the key principles of a first-generation quantum repeater4, in which remote entanglement generation is heralded and operational errors are probabilistically corrected by purification. Schemes for generating remote entanglement are categorized primarily into photon interference schemes, where photons entangled with quantum memories interfere at an intermediate node5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, and scattering schemes that create entanglement through photon scattering between quantum memories14,15,16,17. These schemes have been implemented in various physical systems, including ions5, atoms6,7, color centers in diamond8,9,10,11,14,15,17, and quantum dots12,13. Among these systems, the nitrogen-vacancy (NV) center in diamond has been extensively studied, as the electron in the vacancy serves as a mediating quantum bit and the surrounding nuclear spins serve as long-lived quantum memories18. The NV center is a solid-state system in which high-fidelity quantum operations have been demonstrated19, and several long-lived quantum memories have been successfully manipulated with high-fidelity18,20,21. Moreover, the NV center has interactions not only with optical fields but also with microwave-frequency fields such as magnetic, electric, and strain fields. These properties make the NV center a promising candidate for a high-efficiency quantum transducer, capable of converting microwave photons into optical photons22,23. Owing to these advantages, the NV center has successfully facilitated several demonstrations aimed at developing quantum repeaters, including remote entanglement generation via photon interference8,9, quantum teleportation24, quantum entanglement distillation25, and three-node quantum networking10. In the meantime, research on the emission-absorption scheme, where remote entanglement is generated by emitting a photon entangled with one quantum memory and absorbing it with another26,27, is also making significant progress. Key achievements in this area include quantum state transfer from photon polarization into the nitrogen nuclear spin via absorption28,29,30, entanglement generation between photon polarization and electron spin31,32, and complete Bell state measurements (BSM) using nitrogen or carbon nuclear spins33,34,35,36. The photon interference and scattering schemes require precise frequency tuning because resonance frequency matching between quantum memories is crucial37,38,39. In contrast, the emission-absorption scheme is robust against frequency fluctuations induced by the two-level system around the NV center, as the absorption of the photon functions as a frequency filter40. This scheme shares common elements with the conventional quantum teleportation protocol that employs an entangled photon source and a beamsplitter. However, in this scheme, the NV center itself fulfills the roles of both the entangled photon source and the beamsplitter. The entangled photon source is effectively replaced by the spin-orbit interaction of the electron, generating photon-spin entanglement rather than photon-photon entanglement. Meanwhile, the beamsplitter is substituted by the electron-nuclear spin-spin interaction, enabling a BSM between the electron and the nuclear spin instead of between two photons.

In this study, we demonstrate that the polarization state of a photon incident on an NV center is transferred to the polarization state of an emitted photon, based on the principle of quantum teleportation, via the electron and nitrogen nuclear spins of the NV center. Quantum repeaters play an important role in constructing large-scale quantum networks based on long-distance entanglements. We integrate key components of the photon emission-absorption-based quantum repeater that have been demonstrated individually in previous studies28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Through this study, we validate the functionality of a quantum repeater node and estimate the achievable quantum repeater rate under feasible conditions, including losses during wavelength conversion and long-distance fiber propagation. This demonstration represents a crucial step toward realizing quantum repeaters based on the emission-absorption scheme.

Results

Principle

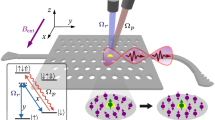

The electron of the NV center has spin-orbit and spin-spin interactions that generate spin-orbit entangled states41, allowing for the generation and measurement of an entangled state between the electron spin and photon polarization. In the same way, the nitrogen nuclear spin has a hyperfine interaction with the electron spin, allowing for the generation and measurement of an entangled state between the electron and nitrogen spins. Through these entanglements, the polarization state of a photon absorbed by the NV is transferred to that of a photon emitted from the NV (Fig. 1a). The transfer process is decomposed into four steps (Fig. 1b): (i) An electron-nitrogen spin entangled state \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({\left\vert +1,+1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}+{\left\vert -1,-1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}})\) is first generated, where \({\left\vert \pm 1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S(N)}}}}\) represents the electron spin (nitrogen nuclear spin) states with z component Sz = ±1 for a total spin quantum number ∣S∣ = 1. (ii) A photon with an arbitrary polarization state, \({\left\vert \psi \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}}=\alpha {\left\vert +1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}}+\beta {\left\vert -1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}}\), is then incident on the NV, attempting to excite the orbital ground state to the excited state \(\left\vert {A}_{2}\right\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({\left\vert +1,-1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,L}}}}+{\left\vert -1,+1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,L}}}})\), which is one of the spin-orbit entangled eigenstates. Here, \({\left\vert \pm 1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{P}}}}\) represents right- or left-handed circular polarization states, while \({\left\vert \pm 1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{L}}}}\) represents the electron orbital states with z component Lz = ±1 for a total orbital quantum number ∣L∣ = 1. Due to the angular momentum selection rules governing the optical transitions between the ground states \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{L}}}}\) and the excited state \({\left\vert \pm 1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{L}}}}\), absorption into the \(\left\vert {A}_{2}\right\rangle\) state occurs only if the incident photon polarization is entangled with the electron spin28,42, thereby effectively serving as a conditional BSM. After these two steps, the polarization state of the absorbed photon \({\left\vert \psi \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}}\) is transferred and stored in the nitrogen spin based on the principle of quantum teleportation29,30, resulting in \(\left\vert {A}_{2}\right\rangle \otimes {\sigma }_{x}{\left\vert \psi \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{N}}}}\). (iii) The excited state \(\left\vert {A}_{2}\right\rangle\) relaxes to the ground state by emitting a photon, generating a polarization-spin entangled state between the emitted photon and the relaxed electron, \({\left\vert {\Psi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{out},S}}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({\left\vert +1,-1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{out},S}}}+{\left\vert -1,+1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{out},S}}})\), based on the angular momentum selection rules31,32. Note that the polarization of the emitted photon is independent of that of the absorbed photon at this stage. The quantum state of the entire system is given by:

(iv) The nitrogen spin state is then transferred to the polarization state of the emitted photon via a unitary operation that corresponds to the measured state within the four Bell states between the electron and nitrogen spins \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{\pm }\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({\left\vert +1,+1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\pm {\left\vert -1,-1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}),{\left\vert {\Psi }^{\pm }\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({\left\vert +1,-1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\pm {\left\vert -1,+1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}})\). Through these four steps, the polarization state of the absorbed photon is transferred to that of the emitted photon. Note that steps (iii) and (iv) are the reverse processes of steps (ii) and (i), respectively.

a Schematic principle of quantum state transfer of the polarization state from the absorbed photon to the emitted photon. b Transfer process consisting of four steps: (i) generation of electron-nitrogen spin entanglement, (ii) transfer of the polarization state of the absorbed photon \({\left\vert \psi \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}}\) to the nuclear spin state of the nitrogen \({\left\vert \psi \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{N}}}}\) via the photon-electron Bell state measurement (BSM) upon absorption, (iii) generation of photon-electron entanglement upon emission, and (iv) transfer of the nuclear spin state of the nitrogen to the polarization state of the emitted photon \({\left\vert \psi \right\rangle }_{{{{\rm{P}}}}_{{{\rm{out}}}}}\) via the electron-nitrogen BSM.

Preliminary experiments

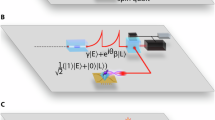

The experimental sequence for the quantum teleportation of a photon via absorption and emission is shown in Fig. 2a, with a preliminary experiment for each step (Fig. 2b-e) corresponding to the processes shown in Fig. 1b. (i) Electron-nitrogen spin entanglement is generated by applying microwaves and radio waves. Under a zero magnetic field, the electron and nitrogen spins split into doubly degenerate levels \({\left\vert \pm 1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S(N)}}}}\) and \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S(N)}}}}\) due to zero-field splitting and nuclear quadrupole splitting, respectively, forming a V(Λ)-type three-level system. Transitions within this system follow the angular momentum selection rules associated with the magnetic polarization of microwaves or radio waves. First, the electron and nitrogen spins are initialized to the \({\left\vert 0,0\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) state and then transitioned to the \({\left\vert 0,+\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) state by horizontally polarized radio waves. Subsequently, microwaves are used to transit the \({\left\vert 0,+\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) state to either the hyperfine-split \({\left\vert \pm 1,\pm 1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) or \({\left\vert \pm 1,\mp 1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) states selected by energy, generating the electron-nitrogen spin entangled states \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) or \({\left\vert {\Psi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\), respectively. For high-fidelity manipulation, the microwave pulse waveforms are optimized using the GRAPE algorithm43 (see Supplementary Information). The fidelity of the generated entangled states is 0.930 for \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) and 0.954 for \({\left\vert {\Psi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) (Fig. 2b). (ii) A weak laser pulse with an average photon number of 1 is incident on the NV, transferring the polarization state of the absorbed photon to the nitrogen spin. Conditioned by the success of photon detection after the absorption, the state fidelity of the nitrogen spin is 0.796 and 0.760 for the polarization states of the absorbed photon \({\left\vert \pm \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}}\), respectively (Fig. 2c). Here, \({\left\vert \pm \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({\left\vert +1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}}\pm {\left\vert -1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}})\) represent horizontal and vertical polarization states. (iii) Upon successful absorption in step (ii), an entangled polarization-spin state \({\left\vert {\Psi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{out},S}}}\) is generated between the emitted photon and the relaxed electron, with the photon measured in the \({\left\vert \pm \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{out}}}}\) polarization basis using a polarizer and detector. The state fidelity of the electron spin is 0.806 and 0.699 for the polarization states of the emitted photon \({\left\vert \pm \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{out}}}}\), respectively. Note that the order of the photon detection and the BSM does not affect the experimental results. (iv) Upon detecting a photon in step (iii), a conditional BSM is carried out between the electron and nitrogen spins. The electron-nitrogen spin Bell states \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{\pm }\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) or \({\left\vert {\Psi }^{\pm }\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) are transferred to the \({\left\vert 0,\pm \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) states using energy-selective microwaves, thereby converting the relative superposition phase of the electron-nitrogen spin entanglement to that of a nitrogen nuclear spin. Subsequently, the \({\left\vert 0,+\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) or \({\left\vert 0,-\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) state is selectively transitioned to the \({\left\vert 0,0\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) state using polarization-selective radio waves, effectively converting one of the Bell states to the \({\left\vert 0,0\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) state. A photon is detected only if the \({\left\vert 0,0\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) state is successfully converted and excited to the \(\left\vert {E}_{x}\right\rangle\) state by laser irradiation, serving as a conditional BSM44. The fidelities of the BSM are 0.879 for the \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) state and 0.884 for the \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{-}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) state, which are generated in step (i) (Fig. 2e).

a Overview of the sequence. Corresponding to the transfer processes shown in Fig. 1b, the sequence comprises (i) electron-nitrogen entanglement generation, (ii) photon-electron BSM upon photon absorption, (iii) photon-electron entanglement generation upon photon emission, and (iv) electron-nitrogen BSM. Purple lines show microwaves or radio waves, and red lines show optical photons. Steps (ii)-(iii) are repeated N times until photon detection succeeds. While the \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) state is shown in (i), the \({\left\vert {\Psi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) state is also generated by tuning the microwave frequency to match the energy gap between \({\left\vert 0,0\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) and \({\left\vert \pm 1,\mp 1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\). b Reconstructed density matrices \({\rho }_{{{\rm{SN}}}}\) in the \({\left\vert \pm 1,\pm 1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) subspace for the electron-nitrogen spin entangled states in (i) with state fidelities 0.930 (top, for \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\)) and 0.954 (bottom, for \({\left\vert {\Psi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\)). c Density matrices ρN in the \({\left\vert \pm 1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{N}}}}\) subspace for the nitrogen spin generated in (ii). The nitrogen spin is transferred into the \({\left\vert \pm \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{N}}}}\) state when a linearly polarized photon \({\left\vert \pm \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({\left\vert +1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}}+{\left\vert -1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}})\) is absorbed with state fidelities of 0.796 (top, for \({\left\vert +\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}}\)) and 0.760 (bottom, for \({\left\vert -\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}}\)). d Density matrices ρS in the \({\left\vert \pm 1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S}}}}\) subspace for the electron spin upon detection of a \({\left\vert \pm \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{out}}}}\) polarized photon in (iii) with state fidelities 0.806 (top, for \({\left\vert +\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{out}}}}\)) and 0.699 (bottom, for \({\left\vert -\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{out}}}}\)). e Probabilities for the electron-nitrogen BSM used in (iv) with fidelities of 0.879 (top, for \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\)) and 0.884 (bottom, for \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{-}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\)), respectively. Error bars represent standard deviations derived from photon shot noise.

To improve the transfer rate, steps (ii)-(iii) are repeated until photon detection succeeds, without reinitializing the electron and nitrogen spins after failed photon detection trials. However, due to interactions between the electron spin and carbon isotope nuclear spins, the coherence of the electron-nitrogen spin entanglement gradually decays. To suppress this decoherence, we implement a dynamical decoupling (DD) method for the electron-nitrogen spin entanglement, improved from the methods shown in refs. 45,46. In the DD sequence, the electron-nitrogen spin entanglement \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) is generated by using the optimized waveform, as shown in Fig. 2b. Subsequently, microwave decoupling pulses are applied to counteract the interactions with carbon spins. Although the coherence of entanglement decreases due to operational errors in decoupling pulses, we set the microwave pulse phases to (0, π) − (0, π) − (π, 0) − (π, 0), which provides robustness against the operational error45,46. The electron-nitrogen spin entanglement \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) is then transitioned to \({\left\vert 0,+\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\). This DD sequence is repeatedly applied until photon detection succeeds. To enhance robustness against operational error, we alternately generate the electron-nitrogen spin entanglements \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) and \({\left\vert {\Psi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\). The incident photon is inserted between the decoupling pulses, with 10 times per DD cycle (Fig. 3a). Although the operational errors increase with the number of DD cycle repetitions NDD (Fig. 3b), the fidelity of the electron-nitrogen spin entanglement is maintained even at NDD = 500 (Fig. 3c). In the demonstration, the maximum number of repetitions is set to NDD = 200 (corresponding to 2000 repetitions of steps (ii)–(iii)), with an average state fidelity of 0.777 for the electron-nitrogen spin entanglement.

a Experimental sequence of dynamical decoupling (DD) for the electron-nitrogen spin entangled state. The sequence is divided into two parts in one repetition of the DD cycle. In the first part, the electron-nitrogen entangled state \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({\left\vert +1,+1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}+{\left\vert -1,-1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}})\) is generated, followed by the periodic application of electron spin bit-flips, consisting of pairs of microwave pulses alternating in phases 0 (purple) and π (cyan). In the second part, the electron-nitrogen entangled state \({\left\vert {\Psi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({\left\vert +1,-1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}+{\left\vert -1,+1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}})\) is generated and the same procedure is repeated. Incident photons are inserted between the bit-flip pulses 10 times per repetition of the DD cycle. b Dependence of the readout probability of electron-nitrogen spin entanglement on the number of repetitions (NDD). By varying the polarization angle ϕ of the radio waves along the equatorial plane \({\left\vert \psi \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{P}}}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({\left\vert +\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{P}}}}+{e}^{i\phi }{\left\vert -\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{P}}}})\), the readout entangled state is varied. When the electron and nitrogen spins are in the maximally entangled state, the readout probability of the entangled state is unity. The coherence of the entangled state decreases as the number of repetitions increases, due to the accumulation of operational errors. c Dependence of the fidelity of the electron-nitrogen spin entanglement on the number of repetitions (NDD). The fidelity is estimated from the visibility of the entanglement coherence. Although the fidelity decreases with an increasing number of repetitions, it does not reach a completely mixed state (F = 0.5) even after 500 repetitions. Since each repetition consists of 10 incoming light pulses and the number of repetitions is limited to 200 (blue line), steps (ii)–(iii) in Fig. 2a are repeated up to 2000 times.

Main experiments

Using the above sequence (Fig. 2a), we demonstrate the correlation between the polarization states of the absorbed and emitted photons. Depending on the heralded BSM outcome \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{\pm }\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) between the electron and nitrogen spins, a positive or negative correlation is obtained between the polarization state of the absorbed photon \({\left\vert \pm \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}}\) and that of the emitted photon \({\left\vert \pm \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{out}}}}\), in accordance with Eq. (1) (Fig. 4a, b). The transferred state fidelity \({F}_{\psi }^{{\Phi }^{\pm }}=(1+V)/2\) in the polarization state \({\left\vert \psi \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}}\) conditioned on the BSM outcome \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{\pm }\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) is calculated with the visibility V = ∣C+ − C−∣/(C+ + C−), where C± represents photon counts obtained with the detection bases of the emitted photon \({\left\vert \pm \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{out}}}}\). The fidelities are estimated to be \({F}_{+}^{{\Phi }^{+}}=0.621,{F}_{-}^{{\Phi }^{+}}=0.670,{F}_{+}^{{\Phi }^{-}}=0.562\) and \({F}_{-}^{{\Phi }^{-}}=0.659\). The dependence of the transfer rate on the average number of incident photons (Fig. 4c) shows that the transfer is feasible even when the absorption probability is much smaller than one. Nevertheless, to ensure the fidelity of the transfer, it is crucial that the transfer rate surpasses the dark count rate of the detector. Even with an average number of incident photons of 0.1, corresponding to a 10 dB loss equivalent to that of 10 km of optical fiber transmission (as discussed later), a transfer rate of 0.2 Hz is achieved, which is higher than the dark count rate. Considering the transfer to the zero-phonon line (ZPL) emission, which constitutes only about 3% of NV emissions47,48, improvements in both absorption and emission efficiencies are necessary to achieve a transfer rate above the dark count rate of the detector. Next, the dependence of transfer fidelity on the average number of incident photons is also measured. We estimate the transfer fidelity \({F}_{+}^{{\Phi }^{+}}\) from the probability that the polarization of the emitted photon is the same as that of the absorbed photon, \({\left\vert +\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{P}}}}\), when the electron-nitrogen spin entanglement is in the \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) state (Fig. 4d). As the average number of incident photons increases, the probability of detecting emission from a second absorption also increases. However, following a failed emission detection after the first absorption, the electron-nitrogen spin entanglement is destroyed, leading to a deterioration in fidelity (see Supplementary Information).

The correlation between the polarization states of the absorbed and emitted photons, conditioned on the BSM outcome, is shown as a, \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{+}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) and b, \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{-}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\). Depending on the BSM outcome, the polarization states of the absorbed and emitted photons exhibit either a positive or negative correlation. The state fidelities \({F}_{\psi }^{{\Phi }^{\pm }}\) of the emitted photon polarization, given the BSM outcome \({\left\vert {\Phi }^{\pm }\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,N}}}}\) and the absorbed photon polarization state \({\left\vert \psi \right\rangle }_{{{\rm{{P}}_{in}}}}\), are as follows:\({F}_{+}^{{\Phi }^{+}}=0.621,{F}_{-}^{{\Phi }^{+}}=0.670,{F}_{+}^{{\Phi }^{-}}=0.562\) and \({F}_{-}^{{\Phi }^{-}}=0.659\). c Dependence of the transfer rate on the average number of incident photons. The transfer rate decreases as the average number of incident photons decreases. When the average number of incident photons numbers is above 0.1, the transfer rate exceeds the detector dark count rate (blue dotted line). The combined efficiency of absorption and emission per incident photon, estimated from the linear fit (red line), is 2.4 × 10−6. Considering the transfer of the absorbed photon polarization state to a zero-phonon line (ZPL) emission photon, the emission efficiency is ~3% of that of the phonon sideband (PSB), resulting in an estimated transfer rate of approximately 3% of that of the PSB (orange line). d Dependence of the state fidelity \({F}_{+}^{{\Phi }^{+}}\) on the average number of incident photons. Red circles represent experimental results, and the blue line represents simulation. The state fidelity improves as the average number of incident photons decreases. Error bars represent standard deviations derived from photon shot noise.

Discussions

In this study, we use the sample with solid immersion lens49,50 milled around the NV center to enhance both absorption and emission efficiencies. Diamond photonic crystal cavities51,52,53,54,55 enable further improvement of these efficiencies, which results in the improvement of the transfer rate. We detect the photon entangled with the electron immediately after absorption. By heralding the transfer of the absorbed photon polarization into the nitrogen spin, the rate of generating remote entanglement in the emission-absorption scheme increases with the aid of the nitrogen spin, by emitting photons repeatedly until detection is successful while maintaining the nitrogen spin state. Moreover, by introducing a complete BSM33,34,35,36, which deterministically projects the nitrogen and electron spins into one of the four Bell states with a single preparation, scalable quantum repeaters can be realized. Furthermore, for the development of long-distance quantum repeaters, we implement quantum wavelength converters (QFC), which convert the visible photon emitted from the NV into a telecom-band photon via a difference frequency generator (DFG) and then reconvert it to the visible band via a sum frequency generator (SFG) for absorption by another NV center. The losses for the fabricated DFG and SFG processes are approximately 3 dB each (see Supplementary Information). Combined with the 2 dB loss along a 10 km length of optical fiber, this results in a total loss of approximately 10 dB. Additionally, by developing polarization-independent QFCs using devices such as Mach-Zehnder56 or Sagnac interferometers57, quantum repeater schemes that leverage the photon polarization are realized.

To enable long-distance quantum communication, the implementation of a quantum repeater protocol across multiple segments is essential. In practical scenarios, an incident photon is replaced by the photon entangled with the electron spin at the sender node, followed by absorption of emitted photons from the repeater node in the electron at the receiver node. To repeat this process multiple times, it is necessary to separate the steps of transferring the entangled photon state into the quantum memory and emitting entangled photons. To satisfy this requirement, the memory state must be maintained while entanglement between repeater node and receiver node is successfully generated.

The achieved teleportation fidelity is sufficient for demonstrating the generation of remote entanglement, but remains insufficient for practical applications. The primary factor contributing to decrease of the fidelity is the decoherence of the electron-nitrogen spin entanglement during DD sequence. This issue can be mitigated by optimizing DD parameters and enhancing Rabi frequency.

Synchronization between remote nodes is a critical requirement for the generation of remote entanglement. Previous studies have demonstrated the remote entanglement generation by the photon interference with the aid of sophisticated synchronization techniques11. In the photon interference schemes, photons are simultaneously incident into a beamsplitter. Moreover, the relative phase of excitation lasers directly affects the entanglement fidelity in certain interference schemes. In contrast, in the photon emission-absorption scheme, the relative phase corresponds to the global-phase of Λ-type three-level system spanned by \({\left\vert {A}_{2}\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,L}}}},{\left\vert +1,0\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,L}}}}\) and \({\left\vert -1,0\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S,L}}}}\), which does not have any effect on the fidelity. Similarly, the photon arrival time does not contribute to the fidelity as long as the coherence of entanglement is maintained40. For these reasons, the photon emission-absorption scheme does not require strict synchronization between remote nodes, compared to the photon interference scheme.

We have demonstrated proof-of-concept experiments for teleportation-based quantum state transfer of photon polarization via straightforward scheme of photon absorption and emission, mediated by nitrogen spin. We have also demonstrated that this quantum state transfer remains feasible even under conditions involving quantum frequency conversion (QFC) and long-distance optical fibers. This demonstration has integrated all the essential technologies of the emission-absorption scheme. As a near-term demonstration, the remote entanglement can be generated by preparing another diamond NV center whose resonance frequency can be tuned by an electric field. By applying the demonstrated processes across multiple nodes, quantum repeaters can be realized, enabling the generation of remote entanglement, which is fundamental to quantum information processing. Furthermore, the error correction codes such as three-qubit code58,59,60,61 and five-qubit code62, which have already been demonstrated in NV center by using several nuclear spins, thereby opening a pathway to the realization of next-generation quantum repeaters4. As the emission-absorption scheme is robust against frequency fluctuations, it offers a new approach for generating high-fidelity remote entanglement, paving the way toward constructing a scalable quantum network, which is not only for long-distance quantum communication but also for distributed quantum computation22.

Methods

Geometric qubits control in NV center

We operate the NV center in the absence of a magnetic field by canceling the geomagnetic field using a three-axis coil attached to the cryostat. The electron spin in the NV forms a spin-1 triplet, represented by mS = 0, ±1, constituting a V-type three-level system in the absence of a magnetic field. Similarly, the nitrogen spin adjacent to the vacancy also forms a spin triplet, represented by mI = 0, ± 1, forming a Λ-type three-level system. We refer to the degenerate states \({\left\vert {m}_{{{\rm{S}}}} = \pm 1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S}}}}\) and \({\left\vert {m}_{{{\rm{I}}}} = \pm 1\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{N}}}}\) as geometric qubits28,29,30,32,35,36,61,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70, which are used to encode information, while \({\left\vert {m}_{{{\rm{S}}}} = 0\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{S}}}}\) and \({\left\vert {m}_{{{\rm{I}}}} = 0\right\rangle }_{{{\rm{N}}}}\) are treated as ancillas for spin state manipulation and readout. The optical transitions in the NV are driven using a 637 nm laser. The electronic orbital excited states used in this study are \(\left\vert {E}_{x}\right\rangle ,\left\vert {E}_{12}\right\rangle\), and \(\left\vert {A}_{2}\right\rangle\), responsible for electron spin state readout, electron spin initialization, and photon absorption and emission, respectively. Among these, the \(\left\vert {A}_{2}\right\rangle\) orbit is entangled with the spin state. Moreover, electron spin manipulation is achieved by applying microwave radiation resonant with the electron spin zero-field splitting (D0/2π = 2.88 GHz). Similarly, nitrogen spin manipulation is achieved by applying a radio frequency resonant with the nuclear quadrupole splitting (Q/2π = 4.945 MHz). These MW and RF fields are simultaneously applied to antennas orthogonally arranged to the diamond sample, providing polarization freedom for arbitrary operations on the geometric qubits.

Experimental setup

The experimental setup includes a home-built confocal microscope and microwave circuit. Incident photons are generated from a 1550 nm laser, chosen to minimize optical fiber loss. The laser light is directed through a 10 km fiber spool in the laboratory to simulate remote nodes and then combined with a 1082 nm pump light in an SFG module to achieve wavelength conversion to 637 nm, resonant with the NV. The wavelength-converted photons are attenuated to single-photon levels using a variable optical attenuator and prepared in arbitrary polarization states with a polarizer and variable waveplate. To enable optical transitions resonant with the NV, the laser beams are combined at a beam splitter and further reflected by a dichroic mirror into the NV excitation path. A 515 nm laser for NV charge initialization is reflected by a different DM with a different reflection wavelength to join the NV excitation path. A single NV center is excited by focusing the laser light through an objective lens with a numerical aperture of 0.95, and the emitted phonon sideband photons are measured by a single-photon detector. To enhance the efficiency of both NV excitation and photon collection, a solid immersion lens is fabricated on the diamond surface49,50.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

The code used for generating data of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aspect, A., Dalibard, J. & Roger, G. Experimental test of Bell’s inequalities using time-varying analyzers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 1804 (1982).

Hensen, B. et al. Loophole-free Bell inequality violation using electron spins separated by 1.3 kilometres. Nature 526, 682–686 (2015).

Briegel, H.-J., Dür, W., Cirac, J. I. & Zoller, P. Quantum repeaters: the role of imperfect local operations in quantum communication. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 5932 (1998).

Azuma, K. et al. Quantum repeaters: from quantum networks to the quantum internet. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 045006 (2023).

Lago-Rivera, D., Rakonjac, J. V., Grandi, S. & Riedmatten, H. D. Long distance multiplexed quantum teleportation from a telecom photon to a solid-state qubit. Nat. Commun. 14, 1889 (2023).

van Leent, T. et al. Entangling single atoms over 33 km telecom fibre. Nature 607, 69–73 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. Long-lived quantum memory enabling atom-photon entanglement over 101 km of telecom fiber. PRX Quantum 5, 020307 (2024).

Bernien, H. et al. Heralded entanglement between solid-state qubits separated by three metres. Nature 497, 86–90 (2013).

Humphreys, P. C. et al. Deterministic delivery of remote entanglement on a quantum network. Nature 558, 268–273 (2018).

Pompili, M. et al. Realization of a multinode quantum network of remote solid-state qubits. Science 372, 259–264 (2021).

Stolk, A. J. et al. Metropolitan-scale heralded entanglement of solid-state qubits. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp6442 (2024).

Delteil, A. et al. Generation of heralded entanglement between distant hole spins. Nat. Phys. 12, 218–223 (2016).

Stockill, R. et al. Phase-tuned entangled state generation between distant spin qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 010503 (2017).

Bhaskar, M. K. et al. Experimental demonstration of memory-enhanced quantum communication. Nature 580, 60–64 (2020).

Bersin, E. et al. Telecom networking with a diamond quantum memory. PRX Quantum 5, 010303 (2024).

Welte, S. et al. A nondestructive Bell-state measurement on two distant atomic qubits. Nat. Photonics 15, 504–509 (2021).

Knaut, C. et al. Entanglement of nanophotonic quantum memory nodes in a telecom network. Nature 629, 573–578 (2024).

Bradley, C. E. et al. A ten-qubit solid-state spin register with quantum memory up to one minute. Phys. Rev. X 9, 031045 (2019).

Rong, X. et al. Experimental fault-tolerant universal quantum gates with solid-state spins under ambient conditions. Nat. Commun. 6, 8748 (2015).

Jung, K. et al. Deep learning enhanced individual nuclear-spin detection. npj Quantum Inf. 7, 41 (2021).

Bartling, H. et al. Universal high-fidelity quantum gates for spin qubits in diamond. Phys. Rev. Appl. 23, 034052 (2025).

Kurokawa, H., Yamamoto, M., Sekiguchi, Y. & Kosaka, H. Remote entanglement of superconducting qubits via solid-state spin quantum memories. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18, 064039 (2022).

Neuman, T. et al. A phononic interface between a superconducting quantum processor and quantum networked spin memories. npj Quantum Inf. 7, 121 (2021).

Hermans, S. et al. Qubit teleportation between non-neighbouring nodes in a quantum network. Nature 605, 663–668 (2022).

Kalb, N. et al. Entanglement distillation between solid-state quantum network nodes. Science 356, 928–932 (2017).

Ritter, S. et al. An elementary quantum network of single atoms in optical cavities. Nature 484, 195–200 (2012).

Delteil, A., Sun, Z., Fält, S. & Imamoğlu, A. Realization of a cascaded quantum system: heralded absorption of a single photon qubit by a single-electron charged quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 177401 (2017).

Kosaka, H. & Niikura, N. Entangled absorption of a single photon with a single spin in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 053603 (2015).

Yang, S. et al. High-fidelity transfer and storage of photon states in a single nuclear spin. Nat. Photonics 10, 507–511 (2016).

Tsurumoto, K., Kuroiwa, R., Kano, H., Sekiguchi, Y. & Kosaka, H. Quantum teleportation-based state transfer of photon polarization into a carbon spin in diamond. Commun. Phys. 2, 74 (2019).

Togan, E. et al. Quantum entanglement between an optical photon and a solid-state spin qubit. Nature 466, 730–734 (2010).

Sekiguchi, Y. et al. Geometric entanglement of a photon and spin qubits in diamond. Commun. Phys. 4, 264 (2021).

Pfaff, W. et al. Demonstration of entanglement-by-measurement of solid-state qubits. Nat. Phys. 9, 29–33 (2013).

Pfaff, W. et al. Unconditional quantum teleportation between distant solid-state quantum bits. Science 345, 532–535 (2014).

Reyes, R. et al. Complete Bell state measurement of diamond nuclear spins under a complete spatial symmetry at zero magnetic field. Appl. Phys. Lett. 120, 194002 (2022).

Kamimaki, A., Wakamatsu, K., Mikata, K., Sekiguchi, Y. & Kosaka, H. Deterministic bell state measurement with a single quantum memory. npj Quantum Inf. 9, 101 (2023).

Bassett, L., Heremans, F., Yale, C., Buckley, B. & Awschalom, D. Electrical tuning of single nitrogen-vacancy center optical transitions enhanced by photoinduced fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 266403 (2011).

Meesala, S. et al. Strain engineering of the silicon-vacancy center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 97, 205444 (2018).

Stolk, A. et al. Telecom-band quantum interference of frequency-converted photons from remote detuned nv centers. PRX Quantum 3, 020359 (2022).

Ito, D. et al. Robust transfer of a quantum state from an absorbed photon into a diamond spin. Opt. Lett. 50, 5073–5076 (2025).

Doherty, M. W. et al. The nitrogen-vacancy colour centre in diamond. Phys. Rep. 528, 1–45 (2013).

Maze, J. R. et al. Properties of nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond: the group theoretic approach. N. J. Phys. 13, 025025 (2011).

Khaneja, N., Reiss, T., Kehlet, C., Schulte-Herbrüggen, T. & Glaser, S. J. Optimal control of coupled spin dynamics: design of NMR pulse sequences by gradient ascent algorithms. J. Magn. Reson. 172, 296–305 (2005).

Robledo, L. et al. High-fidelity projective read-out of a solid-state spin quantum register. Nature 477, 574–578 (2011).

Vetter, P. J. et al. Zero-and low-field sensing with nitrogen-vacancy centers. Phys. Rev. Appl. 17, 044028 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. Zero-field quantum sensing via precise geometric controls for a spin-1 system. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 054011 (2024).

Siyushev, P. et al. Low-temperature optical characterization of a near-infrared single-photon emitter in nanodiamonds. N. J. Phys. 11, 113029 (2009).

Faraon, A., Santori, C., Huang, Z., Acosta, V. M. & Beausoleil, R. G. Coupling of nitrogen-vacancy centers to photonic crystal cavities in monocrystalline diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 033604 (2012).

Hadden, J. et al. Strongly enhanced photon collection from diamond defect centers under microfabricated integrated solid immersion lenses. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 241901 (2010).

Siyushev, P. et al. Monolithic diamond optics for single photon detection. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 241902 (2010).

Riedel, D. et al. Deterministic enhancement of coherent photon generation from a nitrogen-vacancy center in ultrapure diamond. Phys. Rev. X 7, 031040 (2017).

Riedel, D. et al. Efficient photonic integration of diamond color centers and thin-film lithium niobate. ACS Photonics 10, 4236–4243 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Coherent spin control of a nanocavity-enhanced qubit in diamond. Nat. Commun. 6, 6173 (2015).

Burek, M. J. et al. Fiber-coupled diamond quantum nanophotonic interface. Phys. Rev. Appl. 8, 024026 (2017).

Ruf, M., Weaver, M. J., van Dam, S. B. & Hanson, R. Resonant excitation and Purcell enhancement of coherent nitrogen-vacancy centers coupled to a fabry-perot microcavity. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 024049 (2021).

Kaiser, F. et al. Quantum optical frequency up-conversion for polarisation entangled qubits: towards interconnected quantum information devices. Opt. Express 27, 25603–25610 (2019).

Ikuta, R. et al. Polarization insensitive frequency conversion for an atom-photon entanglement distribution via a telecom network. Nat. Commun. 9, 1997 (2018).

Waldherr, G. et al. Quantum error correction in a solid-state hybrid spin register. Nature 506, 204–207 (2014).

Taminiau, T. H., Cramer, J., van der Sar, T., Dobrovitski, V. V. & Hanson, R. Universal control and error correction in multi-qubit spin registers in diamond. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 171–176 (2014).

Cramer, J. et al. Repeated quantum error correction on a continuously encoded qubit by real-time feedback. Nat. Commun. 7, 11526 (2016).

Nakazato, T. et al. Quantum error correction of spin quantum memories in diamond under a zero magnetic field. Commun. Phys. 5, 102 (2022).

Abobeih, M. H. et al. Fault-tolerant operation of a logical qubit in a diamond quantum processor. Nature 606, 884–889 (2022).

Kosaka, H. et al. Coherent transfer of light polarization to electron spins in a semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 096602 (2008).

Sekiguchi, Y. et al. Geometric spin echo under zero field. Nat. Commun. 7, 11668 (2016).

Sekiguchi, Y., Niikura, N., Kuroiwa, R., Kano, H. & Kosaka, H. Optical holonomic single quantum gates with a geometric spin under a zero field. Nat. Photonics 11, 309–314 (2017).

Zhou, B. B. et al. Accelerated quantum control using superadiabatic dynamics in a solid-state lambda system. Nat. Phys. 13, 330–334 (2017).

Ishida, N. et al. Universal holonomic single quantum gates over a geometric spin with phase-modulated polarized light. Opt. Lett. 43, 2380–2383 (2018).

Nagata, K., Kuramitani, K., Sekiguchi, Y. & Kosaka, H. Universal holonomic quantum gates over geometric spin qubits with polarised microwaves. Nat. Commun. 9, 3227 (2018).

Sekiguchi, Y., Komura, Y. & Kosaka, H. Dynamical decoupling of a geometric qubit. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 051001 (2019).

Sekiguchi, Y., Matsushita, K., Kawasaki, Y. & Kosaka, H. Optically addressable universal holonomic quantum gates on diamond spins. Nat. Photonics 16, 662–666 (2022).

Acknowledgements

H. Kosaka acknowledges the funding support from Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) Moonshot R&D grant (JPMJMS2062) and JST CREST grant (JPMJCR1773). H. Kosaka also acknowledges the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) for funding, research and development for construction of a global quantum cryptography network (JPMI00316) and from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (20H05661, 20K20441). R.Reyes acknowledges Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (23KJ0983).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.R. designed and performed the experiments. Y.S. also designed the experiments. D.I., T.F. and K.W. also performed the experiments. T.M. and H. Kato contributed to the fabrication of the solid-immersion-lens structure. H. Kosaka supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reyes, R., Sekiguchi, Y., Ito, D. et al. Quantum teleportation of a photon via absorption and emission for quantum repeater nodes. npj Quantum Inf 12, 25 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01169-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01169-9