Abstract

van der Waals materials are exceptionally responsive to external stimuli. Pressure-induced layer sliding, metallicity, and superconductivity are fascinating examples. Inspired by opportunities in this area, we combined high-pressure optical spectroscopies and first-principles calculations to reveal piezochromism in MnPS3. Dramatic color changes (green → yellow → red → black) take place as the charge gap shifts across the visible regime and into the near infrared, moving systematically toward closure at a rate of approximately −50 meV/GPa. This effect is quenched by the appearance of the insulator–metal transition. In addition to uncovering an intriguing and tunable functionality that is likely to appear in other complex chalcogenides, the discovery that piezochromism can be deterministically controlled at room temperature accelerates the development of technologies that take advantage of stress-activated modification of electronic structure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

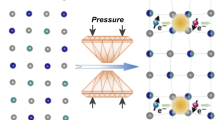

Chalcogenides are exceptionally sensitive to external stimuli. Tuning parameters like pressure and strain can alter the balance of energy scales and drive these materials into new areas of phase space where exotic properties can emerge1,2,3,4. Transition metal phosphorus trisulfides with chemical formula MPS3 (M = Mn, Ni, Fe) display a number of intriguing properties under compression, including (i) insulator–metal transitions, (ii) sliding transitions, and (iii) superconductivity5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Another appealing aspect is pressure-induced color change [Fig. 1]. While it is not uncommon for compression to modify electronic structure, it is unusual for the response to be controllable within the visible portion of the electromagnetic spectrum16,17. Pressure-induced color change in the complex magnetic chalcogenide MnPS3, shown in Fig. 1, can loosely be considered as a visible analog of piezoelectricity, although the mechanisms that underlie piezochromism in complex materials18,19,20,21,22,23,24—beyond donor–acceptor complexes, polymers, and molecular systems25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35—are highly under-explored36. Here, we use a combined spectroscopic and theoretical approach that builds upon recent transport, magnetic, and X-ray properties work in the MPS3 family of materials5,9,10,11 to reveal the electronic structure of MnPS3 under compression, unraveling the microscopic origin of stress-activated color change, the connection of this effect to the stacking sequence, and the nature of chemical bonding in the high-pressure metallic state. At the same time, we unveil a functionality that is likely to emerge in other complex chalcogenides under pressure or strain control.

Results and discussion

Force-activated color change in MnPS3

Figure 2a displays the optical response of MnPS3 as a function of pressure. At ambient conditions, the absorbance increases rapidly above 2.64 eV, in reasonable agreement with prior determinations of the direct band gap37,38,39,40. As discussed in greater detail below, the absorption edge is comprised primarily of charge transfer excitations from the 3p valence band of sulfur to the localized 3d manganese bands37,38,39,40. The literature also reveals that the spectrum contains vibronically activated d-to-d on-site Mn2+ excitations at 1.92, 2.40, and 2.64 eV37,38,39,40. These features are relatively weak in our data due to optical density effects. Thus, the color properties of MnPS3 are primarily defined by the charge transfer excitations that determine the fundamental band gap. The absorption edge moves to lower energy with increasing pressure.

a Optical absorbance of MnPS3 as a function of pressure. The curves are offset for clarity. b Direct band gap analysis under compression. c Band gap as a function of pressure. A number of different data types are included: (i) direct gap values from panel b, (ii) photographic evidence at 20 GPa (when MnPS3 turns black as the gap moves out of the visible range), (iii) infrared results with the band gap above 0.9 eV at 23.8 and 25.2 GPa and (iv) the presence of a Drude signature at 28.2 and 30.5 GPa. d Schematic representation of the sequence of events occurring under pressure in MnPS3. Quasi-linear color control is achieved between 0 and ~28 GPa.

The band gap of MnPS3 can be extracted from the optical response using Tauc plots as:

where α(E) is the absorbance, Eg,dir is the direct gap energy, Eg,ind is the indirect gap energy, Eph is the mediating phonon energy, and both A and B are constants41,42. This model was originally developed for traditional semiconductors with simple single parabolic band structures. More recently, it has been extended to accommodate a variety of more complex materials43. Plots of [α⋅E]2 or [α⋅E]0.5 vs. energy reveal direct or indirect band gap character, respectively41,42. We carried out this analysis for MnPS3 and find a 2.64 eV direct gap at ambient conditions—in excellent agreement with prior work37,38,39,40. We also find that the direct band gap of MnPS3 decreases systematically from 2.64 eV at ambient conditions to 2.15 eV at 11.5 GPa [Fig. 2a, b]. In other words, it closes at the rate of –50 meV/GPa through the optical range. This trend is consistent with the images in Fig. 1.

Figure 2c displays the band gap of MnPS3 as a function of pressure. The gap traverses most of the visible range in a systematic manner. Hence, this complex chalcogenide is an agile and controllable piezochromic material with an operating range from bright green (at ambient conditions), to yellow-green (at 3 GPa), to ruby red (at 8 GPa), and to midnight black (above 20 GPa). These effects are reversible within our sensitivity. As it has a precisely controllable piezochromic response over a wide range of the visible and into the near infrared, MnPS3 is a promising candidate for opto-electronics, spintronics, catalysis, and pressure sensor applications6,44,45,46.

A simple linear extrapolation of the band gap vs. pressure trend reveals two interesting energy scales. First, the gap moves outside the visible range at 20 GPa, consistent with our photographic data [Fig. 1]. Second, if the band gap were to continue closing at the same rate (−50 meV/GPa), we would anticipate full closure near 55 GPa—in reasonable agreement with theoretical predictions for the formation of metallic Mn dimers from the ambient pressure phase11. Of course, MnPS3 probably undergoes a sliding transition that aligns the sulfur centers along the c-axis, similar to that in the Fe analog10. As discussed below, we expect that (i) the sliding transition raises the symmetry of MnPS3 due to removal of monoclinicity by layer stacking and that (ii) the electronic structure of this phase collapses at much lower pressure. Consistently, our measurements reveal that the band gap drops very suddenly across the insulator–metal transition9, which we find to occur at 28.2 GPa. These events, including the development of metallicity, are shown schematically in Fig. 2d. Deterministic and promptly reversible control of the pressure-induced color change is achievable all the way from ambient conditions to the insulator–metal transition.

Interplay between electronic and lattice effects under pressure

In order to better understand the band gap trend and insulator–metal transition, we performed complementary infrared and Raman scattering spectroscopies of MnPS3 under compression. These data allow us to examine and test the role of the lattice across the (i) sliding and (ii) insulator–metal transitions and, at the same time, (iii) reveal the development of metallicity9,10,11. We find two very different but highly inter-related effects. The sliding transition determines how, when, and why the band gap collapses by establishing the space group and interlayer stacking sequence from which the insulator–metal transition takes place.

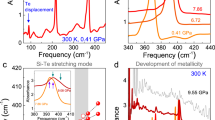

We begin by examining the Raman scattering response of MnPS3 under compression. Evidence for sliding is indirect because the localized phonon modes are nearly decoupled from layer sliding. In other words, the phonons are governed by intra-slab interactions rather than inter-slab proximity effects. As a result, traditional peak coalescence due to restoration of the three-fold axes of rotation47 is replaced by subtle crossover features in the phonon spectra. These small but important frequency shifts occur between 8 and 10 GPa [Fig. 3a], in agreement with our theoretical calculations that show how gradual layer sliding is made manifest in the Raman response. Full details are given in the Supplementary Materials. Interestingly, the band gap vs. pressure trend is relatively linear in this regime [Fig. 2c]—an indication that the electronic properties of MnPS3 are decoupled from the sliding transition as well. This is because the charge transfer excitations that define the gap are local (rather than long-range) in nature and therefore mostly unaffected by the relative positioning of the two-dimensional chalcogenide layers. Nonetheless, the sliding transition renormalizes the critical pressure for band gap closure as discussed below.

a Raman-active vibrational mode frequency vs. pressure across the sliding transition. The gray bar denotes the crossover range, and closed/open circles denote data from two different runs. b Infrared reflectance spectra at ambient conditions and in the metallic phase, depicting the appearance of a Drude. The dashed lines guide the eye—eliminating the diamond signature from the response. c Close up view of the P–S stretching mode, which is sharp and strong at ambient pressure and screened in the metallic state by the Drude.

Next, we consider the spectroscopic properties of MnPS3 across the insulator–metal transition9. It is important to realize that a true metal will sport free carriers and a Drude response (along with strongly screened phonons), a weak metal will show an over-damped response, and a semiconductor will reveal strong phonons riding on a low, flat electronic background. A pressure-driven insulator-to-metal transition ought, therefore, to unveil the development of a Drude response with well-screened phonons. The infrared response of MnPS3 is displayed in Fig. 3b, c. At ambient pressure, the reflectance is low and flat, with a prominent P–S stretching mode near 580 cm−1. The dashed black line guides the eye, omitting the well-known signature of the diamond anvils. These features are very consistent until the level starts to rise slightly near 26 GPa. A metallic Drude response that completely screens the aforementioned vibrational mode develops quite suddenly in our hands at 28.2 GPa. Figure 3c highlights the simultaneous disappearance of the infrared-active P–S stretching mode in the high-pressure phase, consistent with the development of metallicity. The full trend is shown in Supplementary Materials. Based upon these data, we can add several more points to the band gap vs. pressure plot in Fig. 2c. Two of the points have large asymmetric error bars denoting both the size and direction of the positional uncertainty. The asymmetry is because we can estimate only lower limits of the band gap at 23.8 GPa and 25.2 GPa. At the other two pressures (28.2 and 30.5 GPa), the band gap has collapsed to zero, so these values are precise.

We therefore see that there are two aspects to the story of force-induced color change in MnPS3. The first is piezochromism itself. The second is the series of underlying structural distortions that eventually trigger the insulator–metal transition. This is pertinent to the story of piezochromism because it is when the band gap plunges to zero across the insulator–metal transition that deterministic control of piezochromism ends. In other words, the insulator–metal transition defines the upper limit of control.

Expedited gap closure due to the sliding transition

In order to clarify the role of the interlayer structure in determining the rate of band gap closure, we performed first-principles density functional theory (DFT) and dynamical mean-field theory (DMFT) calculations for three different structural models: (i) the monoclinic C2/m structure at ambient conditions with a staggered phosphorous-dimer arrangement across the layers [Fig. 4a], (ii) the intermediate-pressure structure after the sliding transition with an aligned phosphorous-dimer configuration [Fig. 4b], and (iii) the high-pressure structure, similar to the aligned P-dimer phase in terms of stacking but with an aligned phosphorous-chain structure across the layers [Fig. 4c]. The lattice was fully relaxed in each case to minimize energy with the given structural (symmetry and volume) constraints. An enthalpy comparison from DFT + U calculations reveals that the aligned phosphorous-dimer structure is almost as stable as the staggered P-dimer structure even at ambient conditions. It becomes the ground state above ≈10 GPa (see Supplementary Materials). We expect the sliding transition to occur across a fairly broad pressure range as evidenced by the gradual change in the Raman spectra of MnPS3 as well as the X-ray diffraction in FePS310, but for simplicity we chose the staggered and aligned phosphorous-dimer and chain structures as extremal cases for this analysis.

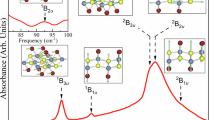

a–c MnPS3 crystal structures with a, monoclinic (C2/m) staggered P-dimer (SPD) structure at ambient pressure, b hexagonal (\(P\bar{3}1m\)) aligned P-dimer (APD) structure in the intermediate-pressure regime (5 ≲ P ≲ 45 GPa), and c aligned P-chain (APC) structure with the monoclinic space group (C2/m). In the APD and APC structure, phosphorus ions in neighboring layers are located on top of each other, forming a chain-like structure in the APC phase above 45 GPa. d–e k-resolved and orbital-projected spectral functions calculated with the structures shown in b and c, respectively, showing the discontinuous nature of the APD to APC transition. f Evolution of the band gap size (obtained from DMFT) as a function of pressure, where the red and green curves represent the band gaps of the SPD and APD/APC structures, respectively. The blue dash-dotted curve shows the anticipated gap size of the APD phase between 28 and 40 GPa, where the gap closes around 30 GPa. g Calculated optical conductivity of MnPS3 in the APD and SPD structures at ambient conditions and under pressure (P = 18.9 and 21.2 GPa, corresponding to the APD and SPD structures, respectively).

In the ambient to small pressure range, most of the charge excitations take place within individual MnPS3 layers. The absence of any sudden change in the optical band gap as a function of pressure below 20 GPa is thus attributed to the local nature of the charge transfer. As pressure is enhanced, the interlayer distance decreases and the system starts to recognize the two different layer stackings. Because of the one-dimensional (dimerized) chain-like structure of phosphorous along the layer-normal direction in the aligned P-dimer structure [Fig. 4b], the band gap is more susceptible to pressure compared to that deriving from a staggered phosphorous-dimer structure. Eventually, collapse of the Mott-character (i.e., disappearance of the imaginary self-energy peak at zero energy) in the aligned P-dimer structure occurs near 45 GPa. It is accompanied by a sudden reduction of the c-axis spacing and an abrupt jump in the phosphorous-dimer distance, which induces the one-dimensional chain-like character of phosphorous centers along the layer-normal direction [Fig. 4c].

Figure 4d, e show the spectral functions A(k, ω) and projected density of states A(ω) for the aligned phosphorous-dimer state at 40.3 GPa and aligned phosphorous-chain state at 45.6 GPa, respectively. While the aligned P-dimer phase maintains Mott-insulating character [Fig. 4d], robust metallicity is observed in the aligned P-chain structure [Fig. 4e]. The appearance of dispersive band character along the layer-normal direction (Γ–Z line) near the Fermi level in Fig. 4d is another feature signaling the transition from a quasi-two-dimensional Mott insulating to three-dimensional metallic phase in the aligned phosphorous-chain structure of MnPS3.

The symmetry lowering across the insulator–metal transition deserves additional comment. Our calculations reveal that the phosphorous-dimer-to-chain transition (\(P\bar{3}1m\) to C2/m) takes place with a spin-state transition and Mott-type metallization. The collapse of the high-spin (S = 5/2) character leads to partial occupancy of the Mn t2g orbital, which breaks the three-fold symmetry in each MnPS3 layer due to the tendency towards Mn-Mn covalency (see Supplementary Materials for further information). This physical picture is different than in FePS310. Here, the high-pressure metallic phase has a d6 (Fe2+) low-spin configuration and, as a consequence, prefers restoration of the three-fold symmetry.

The precise value of the charge gap, as well as the type of structural distortion, that is predicted to take place across the insulator–metal transition is highly sensitive to our choice of starting structure as shown by the evolution of charge gaps of the two different stacking sequences as a function of pressure [Fig. 4f]. Use of an aligned rather than staggered phosphorous-dimer structure reduces the critical pressure from 64 GPa11 to ~45 GPa. In view of the small energy differences between phases, we believe we are justified in identifying this with the insulator–metal transition. In addition to being much closer to the experimental value of the critical pressure, this model takes layer sliding into account10. As the pressure-induced Mott transition occurs simultaneously with an abrupt separation of phosphorous dimers and restoration of the phosphorous-chain structure normal to the Mn layers in the aligned phosphorous-dimer structure, it is clear that layer stacking order and interlayer overlap between phosphorous centers are playing a crucial role in MnPS3 under compression. Thus, we find a clear distinction between conventional layered transition metal chalcogenides and phosphorus trisulfides, which surely deserves further investigation.

Lastly, we comment on the difference between the measured optical gap and calculated electronic gap [Figs 2b and 4f]. The measured optical gap is larger than the calculated electronic gap by ≈0.6 eV at ambient pressure. On the other hand, the simulated optical conductivity σ1(ω) from the same DMFT calculations [Fig. 4g] reveals an optical gap of ≈3 eV. Despite the slightly larger value of the calculated optical gap compared to the experimentally estimated gap, the rate of gap closure vs. pressure is ~0.5 eV per 10 GPa, in very good agreement with our measurements. Unlike the electronic gap, the optical gap is mostly unaffected by layer sliding. Likewise, the calculated optical conductivities of the SPD and APD structures are relatively insensitive to layer sliding. Analysis of the spectral functions reveals that the optical gap originates primarily from transitions between d-p-hybridized states at Mn sites within the same MnPS3 plane, whereas the electronic gap is determined by the sulfur p-bands, which become dispersive under pressure because of the inter-plane overlap between sulfur p-orbitals located in adjacent layers. This difference between the electronic and optical gaps along with the insensitivity of optical gap to structural change emanates from the quasi-two-dimensional character of MnPS3—perhaps opening the door to independent control via pressure and/or epitaxial strain.

Structure–property relations in piezochromic materials

In order to better articulate strategies for the development of piezochromism, we compare the overall pressure scale for force-activated color change in MnPS3 with that in related materials. It is well-known that chalcogenides are relatively soft and sport large volume collapses under pressure48. These and other van der Waals materials are therefore reasonable platforms to search for piezochromic effects. The nature and size of the band gap is also important. It should not be too low or too high. 2H-MoS2, for instance, has a 1.2 eV indirect band gap that is in the near infrared region even before compression, and it closes near 50 GPa49,50. As another example, the layered semiconductor CrSiTe3 displays a 0.4 eV indirect gap and a 1.2 eV direct gap51, so it will suffer from a similar lack of dynamic range. Turning to the lead halide perovskites, systems like CH3NH3PbI3 are known to sport highly tunable electronic structures. The size of the gap at ambient conditions is on the order of 1.6 eV, which is below the visible range, and it closes in a non-linear manner—resulting in a challenge for property control52. The Pb-free halide double perovskites, on the other hand, exhibit band gaps in the visible range and are therefore more promising piezochromics53. Compression also closes the 2.7 eV optical gap in BiFeO3 at a rate of −12.2 meV/GPa—with eventual metallization54,55. As2S3 is another good example, with a 2.7 eV gap that closes rapidly56. What makes MnPS3 particularly attractive is that it has a direct band gap in the visible range57,58. With a −50 meV/GPa shift of the gap under compression, the Mn compound is both agile and linearly responsive—until metallicity develops at 28.2 GPa. Similar work on the Ni and Fe analogs will allow the development of structure–property relations. Finally, we point out that the majority of currently known piezochromics are donor–acceptor complexes, polymers, molecular systems, and liquid crystals25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. The development of this functionality in chalcogenides is therefore significant and potentially useful.

We combined diamond anvil cell techniques, optical spectroscopies, and first-principles electronic structure calculations to reveal piezochromism in the transition metal phosphorus trisulfide MnPS3. Under compression, the charge gap red-shifts across the visible and into the near infrared at a rate of −50 meV/GPa, plunging to zero at the insulator–metal transition—the upper limit of control. The mechanism at 28.2 GPa therefore appears to proceed as a structural distortion that triggers (i) metalization and (ii) the low-spin-state. In addition to accelerating the discovery and fundamental understanding of stress-activated color changes in complex van der Waals materials, this striking effect is reversible and occurs at room temperature, which may pave the way for interesting applications, including opto-electronics, sensors, and low power memory devices6,44,45,46. Coverage of the full visible range and boosting sensitivity while maintaining linearity of control will advance these goals.

Methods

Crystal growth and loading the diamond anvil cell

MnPS3 single crystals were prepared by chemical vapor transport techniques as described previously59. Polycrystalline material was loaded into a symmetric diamond anvil cell along with an annealed ruby ball. Care was taken to optimize the optical density in order to reveal the excitations of interest. KBr or vacuum grease were used as pressure mediums depending on the measurement. This assured a quasi-hydrostatic environment for the sample. Fluorescence from the ruby ball was used to determine pressure60. Various diamond anvil cells, each equipped with different sized diamond culets, were employed depending upon the needed pressure range and whether low fluorescence or Type II diamonds were required for Raman scattering or infrared spectroscopy, respectively.

Spectroscopic measurements

Optical measurements were performed using a Perkin Elmer Lambda-900 grating spectrometer between 1 and 6 eV with 3 nm resolution. Absorbance was calculated as \(\alpha (E)=-\mathrm{ln}\,({\mathcal{T}}(E))\), where \({\mathcal{T}}(E)\) is the measured transmittance. The diamond anvil cell was carefully positioned in the beam, and pressure was increased systematically. Compression was reversible within our sensitivity. We complemented the optical properties work with both synchrotron based infrared spectroscopy (50–8000 cm−1; 2 or 4 cm−1 resolution; both transmittance and reflectance geometries) and Raman scattering (λexcit = 532 nm; ≈1 mW power; 30 s integration, averaged three times) under pressure. These experiments were performed using the 22-IR-1 beamline at the National Synchrotron Light Source II at Brookhaven National Laboratory. All data were collected at room temperature.

First-principles calculations

We employed state-of-the-art embedded dynamical mean-field theory (eDMFT) combined with density functional theory (DFT), which implements forces on atoms and allows relaxation of internal atomic coordinates61. For the optimization of the unit cell size and shape, we performed density functional theory calculations augmented by the on-site Coulomb repulsion U (DFT + U)62. The Vienna ab-initio Simulation Package (vasp) was employed for the DFT + U calculations to optimize the cell shape and lattice parameters63,64, after which eDMFT optimizations of internal atomic coordinates were performed11,61. A continuous-time quantum Monte Carlo method in the hybridization-expansion limit was used to solve the auxiliary quantum impurity problem65, where the full 5 d-orbitals of Mn2+ were chosen as our correlated subspace in a single-site DMFT approximation. Additional computational details are available in the Supplementary Materials and in ref. 11.

Data availability

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The Vienna ab-initio Simulation Package (vasp, Ver. 5.4, see https://www.vasp.at) and Wien2k (Ver. 2019, see http://www.wien2k.at) are commercial codes, while DFT+embedded DMFT Functional code (see http://hauleweb.rutgers.edu/tutorials/) is an open-source one which runs on top of the Wien2k package.

References

Grochala, W., Hoffman, R., Feng, J. & Ashcroft, N. The chemical imagination at work in very tight places. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 3620–3642 (2007).

Flórez, J. M. & Recio, J. M. In An Introduction to High-Pressure Science and Technology (eds Recio, J. M., Menendez, J. M. & Otero de la Roza, A.) 49–73 (Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, 2016).

Snow, C. S. et al. Quantum melting of the charge density wave state in 1T-TiSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 136402 (2003).

Friedemann, S. et al. Large Fermi surface of heavy electrons at the border of Mott insulating state in NiS2. Sci. Rep. 6, 25335 (2016).

Toyoshima, W. et al. Pressure dependence of the magnetic properties of MnPS3. Low. Temp. Phys. 150, 042215 (2009).

Hashemi, A., Komsa, H.-P., Puska, M. & Krasheninnikov, A. V. Vibrational properties of metal phosphorus trichalcogenides from first-principles calculations. J. Phys. Chem. 121, 27207–27217 (2017).

Susner, M. A. et al. Metal thio- and selenophosphates as multifunctional van der Waals layered materials. Adv. Mater. 29, 1602852 (2017).

Sivadas, N. et al. Magnetic ground state of semiconducting transition-metal trichalcogenide monolayers. Phys. Rev. B 91, 235425 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Pressure-driven cooperative spin-crossover, large-volume collapse, and semiconductor-to-metal transition in manganese(II) honeycomb lattices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 15751–15757 (2016).

Haines, C. et al. Pressure-induced electronic and structural phase evolution in the van der Waals compound FePS3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 266801 (2018).

Kim, H. S., Haule, K. & Vanderbilt, D. Mott metal-insulator transitions in pressurized layered trichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 236401 (2019).

Yonggang, W. et al. Emergent superconductivity in an iron-based honeycomb lattice initiated by pressure-driven spin-crossover. Nat. Commun. 9, 1914 (2018).

Coak, M. J. et al. Isostructural Mott transition in 2D honeycomb antiferromagnet V0.9PS3. NPJ Quant. Mater. 4, 38 (2019).

Zheng, Y. et al. Ab initio study of pressure-driven phase transition in FePS3 and FePSe3. Phys. Rev. B 100, 174102 (2019).

Bhutani, A. et al. Strong anisotropy in the mixed antiferromagnetic system Mn1−x FexPSe3. Phys. Rev. Mat. 4, 034411 (2020).

Jaffe, A., Lin, Y., Mao, W. & Karunadasa, H. Pressure-induced conductivity and yellow-to-black piezochromism in a layered Cu-Cl hybrid perovskite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 1673–1678 (2015).

Barreda-Argüeso, J. A. et al. Pressure-induced spin transition and site-selective metallization in CoCl2. Sci. Rep. 9, 5448 (2019).

Gupta, S., Pandey, T. & Kumar-Singh, A. Suppression of Jahn-Teller distortions and origin of piezochromism and thermochromism in Cu-Cl hybrid perovskite. Inorg. Chem. 55, 6817–6824 (2016).

Jaffe, A., Lin, Y. & Karunadasa, H. I. Halide perovskites under pressure: accessing new properties through lattice compression. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 1549–1555 (2017).

Ferrara, M. & Bengisu, M. Intelligent design with chromogenic materials. J. Int. Color. Assoc. 13, 54–66 (2014).

Andrzejewski, M. & Katrusiak, A. Piezochromic topology switch in a coordination polymer. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 929–935 (2017).

Andrzejewski, M. & Katrusiak, A. Piezochromic porous metal-organic framework. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 279–284 (2017).

Kearney, J. et al. Pressure-tuneable visible-range band gap in the ionic spinel tin nitride. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 11623–11628 (2018).

Kormondy, K. et al. Piezoelectric modulation of nonlinear optical response in BaTiO3 thin film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 113, 132902 (2018).

Schmidtke, J. P. et al. Optical spectroscopy of a polyfluorene copolymer at high pressure: intra- and intermolecular interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 167401 (2007).

Kunzelman, J. et al. Oligo(p-phenylene vinylene)s as a new class of piezochromic fluorophores. Adv. Mater. 20, 119–122 (2008).

Sagara, Y. & Kato, T. Mechanically-induced luminescence changes in molecular assemblies. Nat. Chem. 1, 605–610 (2009).

Yu, L. Polymorphism in molecular solids: an extraordinary system of red, orange, and yellow crystals. Acc. Chem. Res. 43, 1257–1266 (2010).

Seeboth, A., Loetzsch, D. & Ruhmann, R. Piezochromic polymer materials displaying pressure changes in bar-ranges. Am. J. Mater. Sci. 1, 139–142 (2011).

Kwon, M. S., Gierschner, J., Yoon, S.-J. & Park, S. Y. Unique piezochromic fluorescence behavior of dicyanodistyrylbenzene based donor-acceptor-donor triad: mechanically controlled photo-induced electron transfer in molecular assemblies. Adv. Mater. 24, 5487–5492 (2012).

Pawle, R. H., Haas, T. E., Muller, A. P. & Thomas III, S. W. Twisting and piezochromism of phenylene-ethynylenes with aromatic interactions between side chains and main chains. Chem. Sci. 5, 4184–4188 (2014).

Qi, Q. et al. Piezochromic materials: remarkable turn-on and color-tuned piezochromic luminescence: mechanically switching intramolecular charge transfer in molecular crystals. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 4171–4171 (2015).

Inoue, T. & Inokuchi, M. Red-shifted photochromism of diarylethenes induced by shear stress. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 89, 671–680 (2016).

Wang, L., Ye, K.-Q. & Zhang, H.-Y. Organic materials with hydrostatic pressure induced mechanochromic properties. Chin. Chem. Lett. 27, 1367–1375 (2016).

Sui, Q. et al. Piezochromism and hydrochromism through electron transfer: new stories for viologen materials. Chem. Sci. 8, 2758–2768 (2017).

Wu, W. et al. Piezoelectricity of single-atomic-layer MoS2 for energy conversion and piezotronics. Nature 514, 470–474 (2014).

Grasso, V., Neri, F., Perillo, P. & Sillipigni, L. Optical-absorption spectra of crystal-field transitions in MnPS3 at low temperatures. Phys. Rev. B 44, 11060–11066 (1991).

Piryatinskaya, V. G., Kachur, I. S., Slavin, V. V. & Yaremenko, A. V. Temperature behavior of the fundamental optical absorption band in quasi-two-dimensional crystalline MnPS3. Low. Temp. Phys. 338, 870–873 (2012).

Kinyanjui, M. K. et al. Spectroscopic properties of a freestanding MnPS3 single layer. Phys. Rev. B 98, 035417 (2018).

Gnatchenko, S. L., Kachur, I. S. & Piryatinskaya, V. G. Exciton-magnon structure of the optical absorption spectrum of antiferromagnetic MnPS3. Low. Temp. Phys. 37, 144–148 (2011).

Tauc, J. Optical properties and electronic structure of amorphous Ge and Si. Mater. Res. Bull. 3, 37–46 (1968).

Pankove, J. I. Optical Processes in Semiconductors. Ch. 3 (Dover, New York, 1971).

Sun, Q.-C. et al. Optical band gap hierarchy in a magnetic oxide: Electronic structure of NiFe2O4. Phys. Rev. B 86, 205106 (2012).

Zhang, X. et al. MnPSe3 monolayer: a promising 2D visible-light photohydrolytic catalyst with high carrier mobility. Adv. Sci. 3, 1600062 (2016).

Sivadas, N., Okamoto, S. & Xiao, D. Gate-controllable magneto-optic Kerr effect in layered collinear antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 267203 (2016).

Li, X., Wu, X. & Yang, J. Half-metallicity in MnPSe3 : exfoliated nanosheet with carrier doping. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 11065–11069 (2014).

Neal, S. et al. Near-field infrared spectroscopy of monolayer MnPS3. Phys. Rev. B 100, 075428 (2019).

Kimber, S. A. J. et al. Giant pressure-induced volume collapse in the pyrite mineral MnS2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 5106–5110 (2014).

Hromadová, L., Matonak, R. & Tosatti, E. Structure change, layer sliding, and metallization in high-pressure MoS2. Phys. Rev. B. 87, 144105 (2013).

Rifliková, M., Martonak, R. & Tosatti, E. Pressure induced gap closing and metallization of MoSe2 and MoTe2. Phys. Rev. B. 90, 035108 (2016).

Casto, L. D. et al. Strong spin-lattice coupling in CrSiTe3. APL Mater. 3, 041515 (2015).

Jaffe, A. et al. High-pressure single-crystal structures of 3D lead-halide hybrid perovskites and pressure effects on their electronic and optical properties. ACS Cent. Sci. 2, 201–209 (2016).

Volonakis, G. & Giusino, F. Surface properties of lead-free halide double perovskites: possible visible-light photo-catalysts for water splitting. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 243901 (2018).

Gavriliuk, A. G., Lyubutin, I. S. & Struzhkin, V. V. Electronic transition and the metallization effect in the BiFeO3 crystal at high pressures. JETP Lett. 86, 532–536 (2007).

Gavriliuk, A. G. et al. Another mechanism for the insulator-metal transition observed in Mott insulators. Phys. Rev. B. 77, 155112 (2008).

Zallen, R. Effect of pressure on optical properties of crystalline As2S3. High. Pres. Res. 24, 117–118 (2004).

Kim, S. Y. et al. Charge-spin correlation in van der Waals antiferromagnet NiPS3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 136402 (2018).

Foot, P. J. S., Suradi, J. & Lee, P. A. Optical and electronic properties of the layered semiconductors NiPS3 and FePS3. Mat. Res. Bull. 15, 189–193 (1980).

Nitsche, R. & Wild, P. Crystal growth of metal-phosphorus-sulfur compounds by vapor transport. Mat. Res. Bull. 5, 419–424 (1970).

Mao, H. K., Xu, J. & Bell, P. M. Calibration of the ruby pressure gauge to 800 kbar under quasi-hydrostatic conditions. J. Geophys. Res. 91, 4673–4676 (1986).

Haule, K. Structural predictions for correlated electron materials using the functional dynamical mean field theory approach. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 87, 041005 (2018).

Dudarev, S. L. et al. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: an LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1506–1509 (1998).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Haule, K. Quantum Monte Carlo impurity solver for cluster dynamical mean-field theory and electronic structure calculations with adjustable cluster base. Phys. Rev. B 75, 155113 (2007).

Acknowledgements

Research at the University of Tennessee is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Science Division under award DE-FG02-01ER45885 (J.L.M). Work at Rutgers University is funded by National Science Foundation DMREF Grant No. DMR-1629059. D.M. acknowledges support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s EPiQS Initiative, Grant GBMF9069. Work at the National Synchrotron Light Source II at Brookhaven National Laboratory was funded by the Department of Energy (DE-AC98-06CH10886). Use of the 22-IR-1 beamline was supported by COMPRES under NSF Cooperative Agreement EAR 11-57758 and CDAC (DE-FC03-03N00144). H.-S.K. acknowledges support from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2019R1G1A1100614), and also the support of computational resources, including technical assistance from the National Supercomputing Center of Korea (Grant No. KSC-2019-CRE-0036). A.V.H. acknowledges funding from the Center for Materials Processing, a Tennessee Higher Education Commission (THEC) supported Accomplished Center of Excellence, for crystal synthesis work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This project was developed by J.L.M., K.H., D.V., H.-S.K., and N.C.H. Crystal growth and basic characterization of the samples were carried out by A.V.H. and D.M., spectroscopic measurements were performed by N.C.H., A.J.C., K.R.O., K.A.S., Z.L., and J.L.M., and first-principles calculations were carried out by H.-S.K., K.H., and D.H.V. The manuscript was written by N.C.H., H.-S.K., D.H.V., and J.L.M. All authors commented on the final document.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Harms, N.C., Kim, HS., Clune, A.J. et al. Piezochromism in the magnetic chalcogenide MnPS3. npj Quantum Mater. 5, 56 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-020-00259-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-020-00259-5

This article is cited by

-

Pressure-tuned plethora of ferroelectric phases in CuInP2S6

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2026)

-

Insulator–metal transition in CrSiTe3 triggered by structural distortion under pressure

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2023)

-

Symmetry progression and possible polar metallicity in NiPS3 under pressure

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2022)