Abstract

Quantum spin liquids are materials that feature quantum entangled spin correlations and avoid magnetic long-range order at T = 0 K. Particularly interesting are two-dimensional honeycomb spin lattices where a plethora of exotic quantum spin liquids have been predicted. Here, we experimentally study an effective S = 1/2 Heisenberg honeycomb lattice with competing nearest and next-nearest-neighbour interactions. We demonstrate that YbBr3 avoids order down to at least T = 100 mK and features a dynamic spin–spin correlation function with broad continuum scattering typical of quantum spin liquids near a quantum critical point. The continuum in the spin spectrum is consistent with plaquette type fluctuations predicted by theory. Our study is the experimental demonstration that strong quantum fluctuations can exist on the honeycomb lattice even in the absence of Kitaev-type interactions, and opens a new perspective on quantum spin liquids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetism arises because of the quantum mechanical nature of the electron spin, yet for the understanding of many materials, particularly those used in today’s applications, a classical approach is sufficient. Materials with strong quantum fluctuations are rare, but attract significant research attention since they hold enormous potential for future technologies1 that make use of the long-range entanglement for quantum communication2,3. Fault-tolerant quantum computers are proposed to operate with anyon quasi-particles2 which exist in a class of quantum spin liquids4,5.

Quantum spin liquids (QSL) are caused by quantum fluctuations which reduce the size of the ordered magnetic moment of static magnetic structures and can affect the dynamics of the spin excitations. This happens in the S = 1/2 frustrated antiferromagnetic square lattice, with competing nearest and next-nearest-neighbour interactions, J1, J2, where the zone boundary spin-waves develop a dispersion due to the presence of quantum dimer-type fluctuations between nearest neighbours6. These fluctuations are similar to the resonant valence bond fluctuations predicted in the frustrated triangular lattice7, which are believed to be relevant for high-temperature superconductors8. Frustration can be induced by competing interactions and depending on their relative strength, incommensurate magnetic phases, valence bond solids with periodic ordering of local quantum states, or QSLs with different symmetry are theoretically predicted4,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. In particular, it is expected that frustration enforces a quantum phase transition at which fractionalization of magnons into deconfined spinons occurs16.

It has been a challenge to identify and understand appropriate model systems to study QSLs. In general, lowering the dimension will increase quantum fluctuations. In one-dimension QSLs have been identified in antiferromagnetic (AF) spin chains. Case in point are KCuF317 and Cu(C6D5COO)2 ⋅ 3D2O18. In two- and three-dimensions, quantum fluctuations can be enhanced by frustration, and there are several routes to achieve this: The inherent geometrical frustration of kagome19, triangular20, spinel21 and pyrochlore22 lattices may prohibit long-range ordering at low temperatures. Another promising candidate is the honeycomb lattice which has received relatively little attention until Kitaev’s work4 when it was realized that bond-dependent anisotropic interactions can stabilize a new form of QSL whose properties are known exactly. Representatives materials are α-RuCl323, Li2IrO324 and H3LiIr2O625 which show signatures of spin correlations due to quantum entanglement.

Quantum fluctuations are enhanced in the honeycomb lattice compared to the square lattice since the number of neighbours of each spin is lower, thus placing it closer to the quantum limit. When next-nearest-neighbour frustrating exchange interactions are sufficiently large compared to the nearest-neighbour exchange, theories predict a quantum phase transition from a Néel ground state into a quantum entangled state. However, there is no consensus on the nature of this ground state: Theories predict either a QSL11,12 or a plaquette valence bond crystal (pVBC)13,14,15 with different magnetic excitations which include spinons11, rotons15 or plaquette fluctuations26.

Here, we study the magnetic properties of the trihalide two-dimensional compound YbBr3 that forms a realization of the undistorted S = 1/2 honeycomb lattice with frustrated interactions. Short-range magnetic correlations between the Yb moments develop below T ≈ 3 K, but the correlation length is only of the order of the size of an elementary honeycomb plaquette at T = 100 mK, consistent with a QSL ground state. Despite this short correlation length, inelastic neutron measurements reveal well-defined dispersive low energy magnetic excitations close to the Brillouin zone centre. At high energies and at the zone boundary, we observe a continuum of excitations that we interpret as quantum fluctuations on an elementary hexagonal plaquette.

Results

Crystal structure and susceptibility

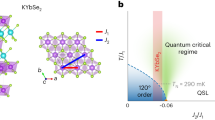

YbBr3 crystallizes with the BiI3 layer structure in the rhombohedral space group \(R\bar{3}\) (148), where the Yb ions form perfect two-dimensional (2D) honeycomb lattices perpendicular to the c-axis, as shown in Fig. 1. The atomic positions are given in Table 1 in Supplementary Note 1. The temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility has a broad maximum around T = 3 K, but as shown below, there is no evidence for long-range magnetic order down to at least T = 100 mK. In the low-temperature regime below 10 K we observe χa ≈ 1.3χc which reflects a small easy-plane anisotropy.

a View along [210] on the unit cell of YbBr3. b Yb3+ honeycomb layer. c Temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility χ of YbBr3 for field orientations along the a- and c-axes. Solid lines are the calculated single-ion susceptibilities based on the crystal-field (CEF)-parameters (see Supplementary Note 2). Inset: Measured low-temperature susceptibility showing a rounded peak around T = 2.75 K. Error bars are standard deviations but are smaller than the data points.

The rare-earth ion Yb3+ features a J = 7/2 ground-state multiplet that is split by the crystal-electric field (CEF), giving rise to a total of four Kramers doublets with the three excited CEF levels being observable via neutron scattering. The first excited level is observed at ~15 meV (see Supplementary Fig. 1) and the ground-state doublet is an effective S = 1/2 state. From an analysis of the measured susceptibility and the inelastic neutron data, we obtain the CEF parameters listed in Supplementary Note 2. They result in ground state expectation values of 〈J⊥〉 = 1.2 and 〈J∥〉 = 0.8 where the subscript indicates spin orientations measured relative to the c-axis.

Magnetic ground state

Figure 2a shows the neutron diffraction pattern of the energy integrated magnetic scattering of Yb3 that was determined as the difference between diffraction patterns taken at T = 100 mK and T = 10 K in order to eliminate the contributions of nuclear scattering. No magnetic Bragg peaks are visible in the diffraction pattern, demonstrating that YbBr3 avoids magnetic order down to at least this temperature.

a Magnetic diffuse scattering in YbBr3 in the [h, k, 0] plane at T = 100 mK, after subtraction of the nuclear Bragg contribution. b Calculated magnetic diffuse scattering based on the spin-wave model including exchange and dipolar interactions. c Cut through the diffuse scattering along the (h, 0, 0) direction. The line is a fit to the data with a Lorentzian function convoluted with the instrumental resolution approximated by a Gaussian. [Note that the presence of paramagnetic scattering at 10 K leads to a negative background in the 100 mK data after subtraction.] Error bars are standard deviations. d Constant-energy scan for \(\hbar\)ω = 0.4 meV in YbBr3 at T = 250 mK showing well-defined low energy excitations. The solid line represents the computed inelastic neutron scattering cross-section. Observed small peaks are due to spurious scattering and are not included in the model calculation. Error bars are standard deviations.

Diffuse magnetic scattering is centred at (1, 0, 0) and equivalent wave-vectors, which implies that the short-range correlations are described by a propagation vector Q0 = (0, 0, 0). Figure 2b shows the diffuse scattering as obtained from the 2D spin-wave theory described below, which reproduces both position and intensity of the observed diffuse scattering.

Figure 2c shows a cut along the Q = (q, 0, 0) direction which reveals diffuse scattering with Lorentzian line shape that reflects short-range magnetic order27. From a fit to the neutron intensity I ∝ κ2/(q2 + κ2), we determine an in-plane correlation length between the Yb moments of ξ = 1/κ ≈ 10 Å at T = 100 mK, comparable to the fourth nearest-neighbour distance of 10.66 Å which is ~1.25 times the diameter of an Yb6-hexagon plaquette.

Magnetic excitations

We measured well-defined magnetic excitations at T = 250 mK along three cuts in the hexagonal plane. Within experimental resolution, we observed a single excitation branch and no spin gap at the zone centre. As shown in the constant-energy-scans in Fig. 2d and in Fig. 3, the magnetic excitations are sharp close to the Brillouin zone centre. One of the key results of this study is the observation of a broadening of the spectrum when the dispersion approaches the zone boundary, as shown in Fig. 3. In fact, the inelastic neutron spectrum close to the zone boundary exhibits a continuum which extends to over twice the energy of the well-defined magnetic excitation. While low-lying excitations are sharp, these broad excitations are only observed at higher energies.

False colour plot of the observed (top) and calculated (bottom) inelastic neutron cross-section of the magnetic excitations in YbBr3 at T = 0.25 K. The intensity is shown on a logarithmic scale. Note the existence of a continuum of excitations around (1/2, 1/2, 0) and (1/2, −1, 0) which is not described by spin waves and is indicative of plaquette fluctuations (see Fig. 5).

While it may appear surprising that we observe well-defined excitations even in the presence of a correlation length of merely 10 Å, this agrees with the predictions of Schwinger-Boson28 and modified spin-wave29 theories which show that spin waves can propagate in low-dimensional systems with short-range Néel order. The well-defined excitations in YbBr3 can be described by an effective S = 1/2 Hamiltonian including nearest and next-nearest-neighbour Heisenberg exchange coupling, and dipolar interactions between the CEF ground-state doublets,

where \({{\mathcal{J}}}_{\alpha ,\beta }(i,j)={g}_{\alpha }^{2}{\delta }_{\mathrm{\alpha \beta }\,}J(i,j)+{g}_{\alpha }{g}_{\beta }{D}_{\alpha ,\beta }(i,j)\), with α, β = x, y, z cartesian coordinates of the hexagonal cell, and \({S}_{i}^{\alpha }\) is the α-component of a spin-1/2 operator at site i. Here, J(i, j) are the exchange coupling constants between distinct sites i and j, while D(i, j) denotes the dipolar interactions. For the calculation of the spin-wave dispersion, we use the random-phase approximation (RPA) around the Néel state with spins in the hexagonal plane and S = 1/2 (see Supplementary Note 3). Our measurements allow the determination of the exchange couplings, while the dipolar coupling is fixed by the magnetic moment. As shown in Fig. 3, we find good agreement between measured and calculated spin-wave dispersions. The nearest- and next-nearest-neighbour exchange interactions J1, J2 are obtained from a least-square fit to the data. We obtained g2J1 = −0.69(8) meV and g2J2 = −0.09(2) meV that correspond to a calculated ground state with Q0 = (0, 0, 0) (see Supplementary Note 4). We note that our spin-wave theory does not describe all aspects of our experimental results: It predicts an optical branch for values of the easy-plane anisotropy that corresponds to the measured susceptibility (see Fig. 1), while we do not find experimental evidence for such a second branch. Also, it does not explain the existence of an excitation continuum as we shall discuss next.

Continuum of excitations

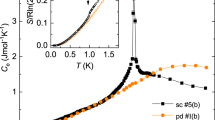

As shown in Fig. 3, the magnetic excitation spectrum also features weaker broad scattering at energies where the optical branch is expected. This is particularly evident near the M-points at (0.5, 0.5, 0) and (0.5, −1, 0), where the excitations extend to 0.8–1 meV and are reminiscent of scattering observed in other low-dimensional antiferromagnets30,31. In most materials, spin-waves are long-lived excitations that are resolution-limited as a function of energy. When the spin waves are damped or interact with other spin-waves they have a finite life-time and the line-shape of the dynamical structure factor S(Q, ω) broadens32. We have simulated the line-shape of S(Q, ω) derived from our model and convoluted it with the resolution of the spectrometer obtained from the Takin software33 (see ‘Methods’). While the spin-wave model adequately explains the dispersion and intensity distribution close to the Brillouin zone centres, it does not reproduce the inelastic neutron line-shape close to the maximum of the dispersion of the spin-wave branch as shown in Fig. 4.

Observed and simulated magnon spectra based on the spin-wave model explained in the text. The lines are the results of a Monte–Carlo simulation of the RPA result convoluted with the instrumental resolution function. In the RPA calculation, a linewidth of ϵ = 0.05 meV is assumed. The shaded area indicates the continuum of excitations. Error bars are standard deviations.

Discussion

Although YbBr3 only exhibits short-range magnetic order, the dispersion of the sharp magnetic excitations can be well described by a spin-1/2 Heisenberg Hamiltonian with easy-plane anisotropy and dipolar interactions. For a honeycomb lattice classical theories predict instability of the Néel state for J2/J1 ≈ 0.110,29 and quantum fluctuation in linear spin-wave theory destroy long-range Néel order. We note that other theoretical approaches find that quantum fluctuations may stabilize the Néel phase up to somewhat higher ratios of J2/J1. These approaches include Schwinger-Boson approach11, variational wave functions15,34 and exact diagonalization13 which all yield a critical ratio J2/J1 ≈ 0.2. Since we find only magnetic short-range correlations between the Yb moments, we conclude that YbBr3 must be in close proximity of such a quantum phase transition.

In YbBr3 the Yb-ion has a large magnetic moment of the order of 2μB and therefore the dipolar interactions cannot be neglected. At the classical level, one can show that they favour antiferromagnetic Néel order with the spins along the c-axis35 enabled by a spin gap at the zone centre of ~200 μeV. This spin gap caused by the dipolar interaction is reduced by the CEF easy-plane anisotropy which contributes to a destabilization of the Néel state at finite temperature (see Fig. 2. in Supplementary Note 3). At gcrit ≈ gzz/gxx ≡ 0.985 the spin gap closes and quantum fluctuations will be enhanced. Below that value, the spins rotate into the basal plane. Linear spin-wave theory predicts that easy-plane anisotropy entails a lifting of the degeneracy of the two spin-wave branches at the zone centre, and the splitting increases with increasing anisotropy. A large anisotropy in YbBr3 would then become measurable since the branch separation becomes large enough to be resolved. A computation of S(Q, ω) at gcrit is shown in Fig. 3 and describes the observed dispersion and intensities of the sharp excitations very well.

Experimentally, we have observed neither a splitting of spin waves nor a spin gap within the available energy resolution. This suggests that the absence of long-range order in YbBr3 at T = 100 mK is caused by the competition between easy-plane anisotropy which favours spins in the plane, and dipolar interactions that favour Ising order along the c-axis. These opposing trends will enhance quantum fluctuations which places YbBr3 close to the quantum critical point towards a QSL of the spin-1/2 Heisenberg Hamiltonian on the honeycomb lattice.

Our experiment provides clear evidence for the presence of a continuum of excitations at high energies in YbBr3. We observe that the intensity of the continuum is stronger at the M’ points along (h, −1, 0) and (h, h, 0) directions whereas it is weak along (0, k, 0) and at the Γ and \({\Gamma }^{\prime}\) points, in contrast to calculations of the two-magnon cross-section for the Heisenberg Hamiltonian (see Supplementary Fig. 3). We found, as shown in Fig. 5, that this modulation of the neutron intensity associated with the continuum can be reproduced by a RPA calculation for a hexamer plaquette with the exchange parameters obtained from the spin-wave calculations (see ‘Methods’). This picture of local excitations in YbBr3 is supported by an analogous calculation of the magnetic susceptibility which shows a broad maximum at T ≃ 4 K (see Fig. 4 in Supplementary Note 5). Similar excitations associated with small spin clusters were also observed in the spinel lattice36. Our neutron measurements are also in agreement with recent Monte–Carlo calculations of the dynamical structure factor for the frustrated honeycomb lattice15 that show a deconfined two-spinon continuum37 with enhanced intensity at the zone boundary due to proximity of a quantum critical point.

The neutron form factor of an Yb6 hexagon calculated within the random-phase approximation at 0.5 meV and assuming Neel order on the plaquette. The directions of the neutron measurement are indicated by white arrows: cut I corresponds to (h, h, 0), cut II is (0, −k, 0) and cut III is (h, −1, 0). High-symmetry points are labelled similar to Fig. 3. Basis vectors of the reciprocal lattice are denoted as a*, b*.

In summary, we have shown that the magnetic ground state of YbBr3 exhibits only short-range order well below the maximum in the static susceptibility. Analysis of the dispersion of the magnetic excitations reveals competition between the nearest-neighbour and next-nearest-neighbour exchange interactions, but we did not observe the mode softening at the K-point which has been predicted15 for large J2. This could be related to the large experimental uncertainty in the value of J2. Also, it is known that a large value of J2 is not necessary for the existence of fractional excitations in 2D systems38. However, an unfrustrated Heisenberg model (J2 = 0) would for our value of J1 result in a long correlation length at T = 100 mK that corresponds to a narrow resolution-limited peak which is at variance with our observations39. We observed a continuum of excitations with the spectrum of excitations extending to approximately twice the energy of the position of the maximum in S(Q, ω). The neutron inelastic intensity due to the continuum follows the modulation expected for the fluctuations of a honeycomb spin plaquette. Our results demonstrate that YbBr3 is a two-dimensional S = 1/2 system on the honeycomb lattice with spin-liquid properties without Kitaev-type interactions. The observation of the continuum associated with localized plaquette excitations supports the view of a deconfined quantum critical point40 in the frustrated honeycomb lattice, in agreement with results from coupled-cluster methods, density matrix renormalization group calculations and Monte–Carlo simulations14,15,41. Our measurements set a quantitative benchmark for future theoretical work.

Methods

Crystal growth and sample preparation

An YbBr3 single crystal of cylindrical shape (15-mm diameter, 18-mm height) was grown from the melt in a sealed silica ampoule by the Bridgman method, as previously described for ErBr342. YbBr3 was prepared from Yb2O3 (6N, Metall Rare Earth Ltd.) by the NH4Br method43 and sublimed for purification. All handling of the hygroscopic material was done under dry and O-free conditions in glove boxes or closed containers.

Magnetic susceptibility

The magnetic susceptibility was determined with a MPMS SQUID system (Quantum Design).

Neutron scattering experiments

The neutron experiments were performed at the Swiss Spallation Neutron Source (SINQ) utilizing different instruments. On all instruments, filters were used to reduce contamination of the beam by higher-order neutron wavelengths.

The crystal structure of YbBr3 was refined using diffraction data collected with the high-resolution powder diffractometer HRPT at the wavelength of λ = 1.494 Å at room temperature. The crystal structure and lattice parameters were refined with Fullprof.

The magnetic ground state was investigated with the multi-counter diffractometer DMC at the wavelength λ = 2.4576 Å which integrates fluctuations up to a maximum of ~13.5 meV. The measured neutron intensity is proportional to the equal time spin–spin correlation function.

The crystal-field splitting of the Yb3+ ions was determined on the thermal three-axis spectrometer EIGER operated in the constant final-energy mode with kf = 2.662 Å−1 at T = 1.5 K and ∣Q∣ = 1.5 Å−1. With that configuration the energy resolution is 0.8 meV.

The dispersion of the magnon excitations is bound by \(\hbar\)ω(q) < 1 meV in YbBr3 which required the use of cold neutrons that provide an improved energy resolution. Therefore the measurements of the spin waves were performed with the TASP three-axis spectrometer using kf = 1.3 Å−1 which resulted in an energy resolution of 80 μeV. To maximize the intensity, the measurements were performed without collimators in the beam and the analyser was horizontally focusing.

Magnetic excitations

We analysed the dispersion of the magnetic excitations with a Heisenberg Hamiltonian,

J(i, j) are the exchange constants between sites i and j, to be determined experimentally, the anisotropic g-factors reflect the cystal-field anisotropy where α = x, y, z denotes Cartesian coordinates, and \({S}_{i}^{\alpha }\) denotes the α component of a spin-1/2 operator at site i. For Heisenberg interactions gx = gy = gz ≡ g. Because the magnetic moment of Yb3+ is large, we also consider the dipolar interactions,

with

where Rij ≡ Rj − Ri is the relative position vector between the j’th and i’th ion.

The dispersion of magnetic excitations was calculated within the RPA where the spin waves appear as poles in the dynamical tensor \(\overline{\overline{\chi }}({\bf{q}},\omega )\),

with \(\overline{\overline{M}}({\bf{q}})\) the Fourier transform of the exchange and dipolar interactions and \({\overline{\overline{\chi }}}_{0}(\omega )\) the single-ion susceptibility. The neutron cross-section is proportional to the imaginary part of the dynamical susceptibility44,

where we defined the dynamical structure factor,

Here Q denotes the scattering vector, and u, v labels the Yb ions in the magnetic cell. To analyse the data, the scattering cross-section was convoluted with the resolution of the spectrometer using Popovici method implemented in Takin33, and the corresponding Monte–Carlo results are shown in Fig. 4.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Information. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

References

Dowling, J. P. & Milburn, G. J. Quantum technology: the second quantum revolution. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 361, 1655–1674 (2003).

Kitaev, A. Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Ann. Phys. 303, 2–30 (2003).

Nayak, C., Simon, S. H., Stern, A., Freedman, M. & Das Sarma, S. Non-Abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1083–1159 (2008).

Kitaev, A. Y. Anyons in an exactly solved model and beyond. Ann. Phys. 321, 2–111 (2006).

Savary, L. & Balents, L. Quantum spin liquids: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 016502 (2016).

Tsyrulin, N. et al. Quantum effects in a weakly frustrated S = 1/2 two-dimensional Heisenberg antiferromagnet in an applied magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 197201 (2009).

Anderson, P. W. Resonating valence bonds: a new kind of insulator? Mat. Res. Bull. 8, 153–160 (1973).

Anderson, P. W. et al. The physics behind high-temperature superconducting cuprates: the ‘plain vanilla’ version of RVB. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 16, R755–R769 (2004).

Mulder, A., Ganesh, R., Capriotti, L. & Paramekanti, A. Spiral order by disorder and lattice nematic order in a frustrated Heisenberg antiferromagnet on the honeycomb lattice. Phys. Rev. B 81, 214419 (2010).

Fouet, J. B., Sindzingre, P. & Lhuillier, C. An investigation of the quantum J1 − J2 − J3 model on the honeycomb lattice. Eur. Phys. J. B 20, 241–254 (2001).

Merino, J. & Ralko, A. Role of quantum fluctuations on spin liquids and ordered phases in the Heisenberg model on the honeycomb lattice. Phys. Rev. B 97, 205112 (2018).

Wang, F. Schwinger boson mean field theories of spin liquid states on a honeycomb lattice: projective symmetry group analysis and critical field theory. Phys. Rev. B 82, 024419 (2010).

Albuquerque, A. F. et al. Phase diagram of a frustrated quantum antiferromagnet on the honeycomb lattice: Magnetic order versus valence-bond crystal formation. Phys. Rev. B 84, 024406 (2011).

Ganesh, R., van den Brink, J. & Nishimoto, S. Deconfined criticality in the frustrated Heisenberg Hamiltonian honeycomb antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 127203 (2013).

Ferrari, F. & Becca, F. Dynamical properties of Néel and valence-bond phases in the J1 − J2 model on the honeycomb lattice. J. Condens. Matter Phys. 32, 274003 (2020).

Senthil, T., Vishwanath, A., Balents, L., Sachdev, S. & Fisher, M. P. A. Deconfined quantum critical points. Science 303, 1490–1494 (2004).

Tennant, D. A., Perring, T. G., Cowley, R. A. & Nagler, S. E. Unbound spinons in the S = 1/2 antiferromagnetic chain KCuF3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 4003–4006 (1993).

Dender, D. C., Hammar, P. R., Reich, D. H., Broholm, C. & Aeppli, G. Direct observation of field-induced incommensurate fluctuations in a one-dimensional S = 1/2 antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 1750–1753 (1997).

Mendels, P. & Bert, F. Quantum kagome frustrated antiferromagnets: one route to quantum spin liquids. C. R. Physique 17, 455–470 (2016).

Shimizu, Y., Miyagawa, K., Kanoda, K., Maesato, M. & Saito, G. Spin liquid state in an organic Mott insulator with a triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 107001 (2003).

Villain, J. Insulating spin glasses. Z. Physik B 33, 31–42 (1979).

Canals, B. & Lacroix, C. Pyrochlore antiferromagnet: a three-dimensional spin liquid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 2933–2936 (1998).

Banerjee, A. et al. Proximate Kitaev quantum spin liquid behaviour in a honeycomb magnet. Nat. Mater. 15, 733–741 (2016).

Singh, Y. et al. Relevance of the Heisenberg-Kitaev model for the honeycomb lattice iridates A3IrO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 127203 (2012).

Kitagawa, K. et al. A spin-orbital-entangled quantum liquid on a honeycomb lattice. Nature 554, 341–345 (2018).

Ganesh, R., Nishimoto, S. & van den Brink, J. Plaquette resonating valence bond state in a frustrated honeycomb antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 87, 054413 (2013).

Collins, M. R. Magnetic Critical Scattering (Oxford University Press, 1989).

Mattsson, A., Fröjdh, P. & Einarsson, T. Frustrated honeycomb Heisenberg antiferromagnet: a Schwinger-boson approach. Phys. Rev. B 49, 3997–4002 (1994).

Ghorbani, E., Shahbazi, F. & Mosadeq, H. Quantum phase diagram of distorted J1–J2 Heisenberg S = 1/2 antiferromagnet in honeycomb lattice: a modified spin wave study. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 28, 406001 (2016).

Mourigal, M. et al. Fractional spinon excitations in the quantum Heisenberg antiferromagnetic chain. Nat. Phys. 9, 435–441 (2013).

Han, T.-H. et al. Fractionalized excitations in the spin-liquid state of a kagome-lattice antiferromagnet. Nature 492, 406–410 (2012).

Zhitomirsky, M. E. & Chernyshev, A. L. Colloquium: spontaneous magnon decays. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 219–243 (2013).

Weber, T., Georgii, R. & Böni, P. Takin: an open-source software for experiment planning, visualization, and data analysis. SoftwareX 5, 121–126 (2016).

Ferrari, F., Bieri, S. & Becca, F. Competition between spin liquids and valence-bond order in the frustrated spin-1/2 Heisenberg model on the honeycomb lattice. Phys. Rev. B 96, 104401 (2017).

Pich, C. & Schwabl, F. Order of two-dimensional isotropic dipolar antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 47, 7957–7960 (1993).

Lee, S.-H. et al. Emergent excitations in a geometrically frustrated magnet. Nature 418, 856–858 (2002).

Ferrari, F. & Becca, F. Spectral signatures of fractionalization in the frustrated Heisenberg model on the square lattice. Phys. Rev. B 98, 100405 (2018).

Dalla Piazza, B. et al. Fractional excitations in the square-lattice quantum antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 11, 62–68 (2015).

Chakravarty, S., Halperin, B. I. & Nelson, D. R. Low-temperature behavior of two-dimensional quantum antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 1057–1060 (1988).

Senthil, T., Balents, L., Sachdev, S., Vishwanath, A. & Fisher, M. P. A. Quantum criticality beyond the Landau-Ginzburg-Wilson paradigm. Phys. Rev. B 70, 144407 (2004).

Bishop, R. F., Li, P. H. Y. & Campbell, C. E. Valence-bond crystalline order in the S = 1/2J1 − J2 model on the honeycomb lattice. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 25, 306002 (2013).

Krämer, K. W. et al. Noncollinear two- and three-dimensional magnetic ordering on the honeycomb lattices of ErX3 (X = Cl, Br, I). Phys. Rev. B 60, R3724–R3727 (1999).

Meyer, G. Advances in the Synthesis and Reactivity of Solids, Vol. 2, 1–26 (Elsevier Science Technology, Oxford, 1994).

Jensen, J. & Macintosh, A. R. Rare Earth Magnetism (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1991).

Acknowledgements

The financial support by the Swiss National Science Foundation under grant no. SNF 200020_172659 is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.C., L.K., M.K., B.R. and C.W. performed the neutron experiments. Crystal growth and characterization was done by K.W.K. Theoretical calculations were performed by B.D., B.R., C.W., O.W., and H.B.B. Data analysis and discussion of the results was done by all authors. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wessler, C., Roessli, B., Krämer, K.W. et al. Observation of plaquette fluctuations in the spin-1/2 honeycomb lattice. npj Quantum Mater. 5, 85 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-020-00287-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-020-00287-1

This article is cited by

-

Field-tuned quantum renormalization of spin dynamics in the honeycomb lattice Heisenberg antiferromagnet YbCl3

Communications Physics (2023)