Abstract

Topological materials possess unique electronic properties and hold immense attraction to both fundamental physics research and practical applications. Over the past decades, the discovery of new topological materials has relied on the symmetry-based analysis of the quantum wave function. In this study, we propose an efficient inverse design method CTMT (CTMT: CDVAE, Topogivity, interatomic potentials (IAPs) as realized in M3GNet, and TQC) utilizing deep generative machine learning models to discover novel topological insulators and semimetals in a much-fast and low-cost manner. This method covers the entire process of new crystal structure generation, heuristic rule screening, fast stability estimation, and topology type diagnosis, resulting in 4 topological insulators and 16 topological semimetals. Especially, the newly discovered topological materials include several chiral Kramers-Weyl fermion semimetals and chiral materials with low symmetry, whose topology is previously considered challenging to discern. These findings demonstrate the capability of CTMT in discovering topological materials and its great potential for data-driven inverse design of advanced functional materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topological materials refer to materials with special topological arrangements in the geometric of electronic band structures, which can produce robust surface states and unconventional electromagnetic activities1,2. The topology represents that the electronic structure of the materials will not change due to parameter tuning without opening the energy gap. These materials, encompassing topological insulators (TIs)3,4,5 and topological semimetals (TSMs)6,7,8,9, have captured considerable attention over recent decades due to their extraordinary properties. These materials showcase robust boundary states that are resilient to the perturbing effects of static disorder, distinguishing them from conventional materials. Moreover, their unique features, including the topological magneto-electric effect and anomalous transport phenomena such as the quantum anomalous Hall effect10,11,12, highlight their potential to advance our understanding of condensed matter physics and spintronics. These novel electronic properties of topological materials have great potential in the development of dissipationless electronic11 and spintronic devices13. Since the inception of this field, the quest to discover new TIs and TSMs has emerged as a pivotal and cutting-edge area of research. The advancements in this field have predominantly hinged on first-principles calculations anchored in topological band theory14,15. In particular, the advent of theories like symmetry indictors16 and topological quantum chemistry (TQC)17 has led to the discovery of a large number of topological materials and the establishment of numerous databases1,18,19 based on high-throughput computation. The burgeoning volume of data has made machine learning be used to solve the problems of theoretical classification frameworks in terms of computational speed20, topology determination21, and low-symmetry structure classification22. Despite these notable advancements, current methodologies predominantly focus on identifying topological materials within pre-existing databases1,18,19,20,22. There remains a significant challenge in the ability to discover novel topological materials that extend beyond the confines of pre-existing ones. This challenge is particularly pronounced in the realm of low-symmetry chiral Kramers-Weyl semimetals, where they will break the double spin entanglement guaranteed by the traditional symmetry rules such as Kramer’s theorem, thereby leading to the appearance of new topological phases23,24. Nevertheless, materials with low-symmetry topological band structures are recognized as key candidates for achieving field-free switching and high energy efficiency technologies due to their unique electronic properties. The low-symmetry of these materials leads to unconventional spin polarization, which can be induced by current, enabling precise control of the magnetization state without the need for an external magnetic field25,26,27. In light of these considerations, it becomes critically important to develop a robust, data-driven approach that can simultaneously generate and diagnose novel and stable TIs and TSMs which transcends the restrictions imposed by symmetry rules.

Inverse design28,29,30,31 is a data-driven strategy with available data of desired material functionality, domain knowledge and artificial intelligence to discover materials that exhibit this functionality31. The data-driven strategy has emerged as a leading approach in the realm of novel materials research. A critical challenge in inverse design is searching for desired materials in countless possible materials with different properties which depend on chemical composition and crystal structure32. One such solution is the application of generative machine learning models in the design of new candidate structures. However, these generative models often grapple with the challenge of capturing translationally and rotationally invariant representations when dealing with crystalline materials28,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. To overcome this limitation, the crystal diffusion variational autoencoder (CDVAE)40 adopts diffusion models41,42 to directly generate the atomic coordinates of crystalline lattice structures with these invariant representations and employs periodic graph neural networks (PGNNs)43 as the backbone of variational autoencoders44, enhancing its capacity to handle complex structures. These PGNNs enable CDVAE to capture the translational and rotational invariance of crystals by ensuring periodic rotation, reflection, and translation invariances, leading to higher stability and reduced screening costs. Compared to traditional methods such as trial and error, random search, and density functional theory (DFT) approaches, the advantage of diffusion-based models45,46,47 is that they can efficiently generate diverse and highly realistic materials structure at an extremely low computational cost. This is because diffusion-based models generate novel materials by following the distribution of available materials in used datasets, which is usually called data-drawn discovery. This approach has been adeptly integrated into the inverse design framework, significantly enhancing the discovery process of an extensive array of innovative materials, including one-dimensional structures48, two-dimensional (2D) materials32 and high-critical temperature superconducting materials49. Despite these advancements, it is noteworthy that, within the current scope of our knowledge, the exploration and identification of new topological materials through the application of generative models represents a yet unexplored frontier.

In this work, we demonstrate that generative machine-learning models can also be used in the quest for new topological materials. We introduce a data-driven inverse design method CTMT tailored for the discovery of novel TIs and TSMs. CTMT synergistically combines several cutting-edge technologies: the aforementioned CDVAE, Topogivity22, interatomic potentials (IAPs) as realized in M3GNet50, and TQC. This integrative approach enables CTMT not only to generate but also to effectively identify stable topological materials beyond pre-existing ones. Our method has proven its efficacy by finding 4 TIs and 16 TSMs that are absent in current material databases, including 4 chiral Kramers-Weyl semimetals. These findings exhibit the potential of CTMT as a universal tool for the exploration and discovery of novel topological materials, paving the way for uncovering even more diverse and rare material types.

Results

Workflow

Figure 1 illustrates the main framework of CTMT, including four sequential functional blocks: generation, filtering, stability verification, and topology type classification, for the systematic discovery and validation of new TIs and TSMs.

a The dataset of topological materials, b the Crystal Diffusion Variational Autoencoder (CDVAE), c the novelty and legitimacy check unit, d the Topogivity check unit, e DFT calculations of the formation energy (Eform)and the energy above hull (Ehull), f fast phonon spectrum scanning by M3GNet, and final TQC as shown in (g) determines 20 stable topological materials, including 16TSMs and 4 TIs as shown in (h).

Generation of Crystal Structures

The purpose of the first functional block is to generate new crystal structures. The used training dataset is from the topological materials database (https://www.topologicalquantumchemistry.fr/), as depicted in Fig. 1a, which includes 6109 TIs and 13,985 TSMs. The original database also includes 18,090 trivial materials, which were excluded from the training dataset. Notably, this same training dataset has been employed in recent studies51,52,53. Supplementary Fig. S1 shows the atomic proportion percentage across the training dataset. The trained CDVAE model generates 10,000 highly realistic candidates of potential topological materials based on Langevin dynamic sampling42 (Fig. 1b, see Methods section for details). The generated 10,000 candidates are fed into the filter block, as shown in Fig. 1c.

Filtering Process

The filter block checks the novelty, legitimacy, and topologically nontrivial possibility of the candidates. The novelty check is performed by eliminating materials with the same chemical formula and structure in the dataset using the StructuresMatcher package of pymatgen54. The main parameters for StructureMatcher were set as follows: lto at 0.2, stol at 0.3, and angle_tol at 5. The legitimacy of materials is determined by using the smart packages55 to verify whether their stoichiometric chemical formulas satisfy charge neutrality and electronegativity balance. The third check uses pymatgen packages54 to assess structural validity by examining if the bond length of these crystals is larger than 0.5 Å. After that, 4,715 valid candidates pass the first three checks and go through the ‘Topogivity’22 check, as shown in Fig. 1d. Topogivity is a machine-learned chemical rule for discovering topological materials22. A given material is diagnosed with high accuracy (typically > 80%) as topological nontrivial (trivial) if the weighted average of its element’s Topogivities is positive (negative). Our present work uses the criterion that the weighted average Topogivity should be greater than one to obtain more accurate topological nontrivial materials. In addition, candidates containing elements with 4f or 5f electrons are excluded due to the challenges in obtaining accurate results from DFT calculations, which arise from their complex electronic structures and the significant relativistic effects introduced by spin-orbit coupling (SOC). Furthermore, magnetic atoms are also excluded because of the additional computational procedures required to determine the magnetic ground state. The difficulty of generating materials with heavy elements and magnetic atoms is a potential obstacle that may influence results. This filtering gives 104 potential topologically nontrivial materials for further stability verification.

Stability verification

The stability verification block examines the stability of the candidates. First, DFT calculations are performed, as shown in Fig. 1e, to calculate the formation energy and energy above hull. If a candidate has a positive formation energy Eform ≥ 0 eV/atom or its energy above hull is Ehull ≥ 0.16 eV/atom, the candidate is thermodynamically unstable and will be removed. The 57 candidates with Eform < 0 eV/atom and Ehull < 0.16 eV/atom are potentially synthesizable (see Methods section for details). Since thermodynamic stability alone is not sufficient to ensure candidate stability, phonon spectrum calculations must be conducted to check whether there are imaginary phonon frequencies inside the 57 candidates. As the phonon spectrum calculation based on Vienna ab initial simulation package (VASP)56 is a computationally intensive task, the pre-trained M3GNet50 is directly integrated into CTMT without any further training to complete the verification. Compared to other machine-learning interaction potential methods such as MACE57 and CHGNet58, M3GNet can directly provide phonon spectrum, without converting predicted forces and energies into second-order force constants, while ensuring high prediction accuracy59. Therefore, M3GNet is adopted in the present work for stability checks. As shown in Fig. 1f, the IAPs predicted by M3GNet is utilized to perform fast phonon spectrum calculations. This step filters out candidates with imaginary phonon frequencies and leaves 32 stable candidate materials (see Methods section for details).

Topology type classification

The fourth block, as shown in Fig. 1g, uses TQC on the Bilbao Crystallography Server1 to ultimately determine the topology type of the materials, leading to the discovery of 20 new topological materials (Fig. 1h, see Methods section for details), including 16 TSMs and 4 TIs. TQC is a band theory of the structure of energy bands in crystals and links to the topological properties of crystals with electron orbitals at the Fermi level.

Topogivity

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of atomic proportion percentages and Topogivity values across these 104 topologically nontrivial candidates after the Topogivity check, offering key insights into the diversity of their compositions. The trained CDVAE model generates candidates with a wide range of compositions, as evidenced by the fact that the atoms in these 104 materials span most elements with known Topogivity. Interestingly, elements such as oxygen (O), fluorine (F), phosphorus (P), chlorine (Cl), bromine (Br), and iodine (I) are absent in the 104 materials, because they have large negative values of Topogivity22. In the 32 stable candidates, 20 of them are confirmed to be topological, reaching an accuracy rate of 62.5%. Although this accuracy is lower than the classification accuracy of Topogivity (82.4%)22, CTMT discovers novel topological materials with extremely high fabrication feasibility. The integration of Topogivity into CTMT not only significantly reduces the material search space but also enhances the proportion of topological materials among the candidates recommended by the CDVAE model.

Stability

Figure 3a displays a detailed stability verification. The DFT calculations show that 77 crystals of the 104 candidates have formation energies Eform < 0 eV/atom and are thus considered thermodynamically stable, accounting for the percentage of 74%. In the 77 candidates, 57 materials have Ehull < 0.16 eV/atom with high synthesis possibility, which gives the percentage of 74% as well. Figure 3b, c show the energy distribution of Eform < 0 eV/atom for 77 materials and Ehull < 0.16 eV/atom for 57 materials, respectively. The formation energy is clustered around –0.4 eV/atom, indicating a general trend of energy stability. Similarly, the energy above the hull is distributed around 0 eV/atom. Notably, materials with Ehull = 0 eV/atom are of particular interest as they signify the ground state or the most stable configuration achievable. In this work, there are 11 materials with Ehull = 0 eV/atom as the phase diagrams shown in Supplementary Fig. S2, S3. Furthermore, the M3GNet integrated in CMTM estimates the phonon spectrums and gives only 32 structural stable and synthesis feasible candidates, out of the 57 potential candidates with a success rate of 56%, echoing with the prediction of 2D materials at 69%32.

Topological properties

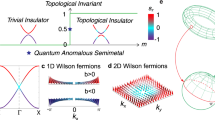

The TQC methodology1 is finally performed to ascertain the topological classification of each stable structure, resulting in 16 TSMs and 4 TIs. We use the TQC method to obtain the characters of all bands at all the relevant high-symmetry points (the maximal k-vectors). If the characters at the relevant high-symmetry points do not satisfy the compatibility conditions, it means they are enforced semimetals. Each identified TSM is classified as an enforced semimetal with Fermi degeneracy (ESFD). EFSD depends on whether they have a high-symmetry point degeneracy at the Fermi level. All 16 TSMs have a high-symmetry point degeneracy at the Fermi level, while the TIs exhibited distinct topological invariant numbers. The physical behaviors of bands in momentum space are interpreted using several kinds of topological invariant numbers. The topological invariant is a quantized number that characterizes the topological status of a given system, and the Chern number and Z2 number are examples of the topological invariant numbers. Topological invariant numbers are the conserved quantities when any topological phase transitions do not occur60. For the definition of TI in this context, from the theory of TQC17, if the set of bands below the Fermi level cannot be expressed as a linear combination of elementary band representations (EBRs), then it can be identified as a TI. It’s very important to note that sometimes the TI identified in this frame may lack a band gap, as we can also see many examples from the topological materials database1,17,61. Unlike the conventional definition of an insulator, which requires a global band gap (i.e., a nonzero indirect band gap between the conduction band minimum and the valence band maximum). In TQC, it is sufficient for every high symmetry k point in the Brillouin zone to exhibit a direct band gap, such that the occupied and unoccupied states can adiabatically evolve into a global band gap17. TIs identified through TQC may exhibit band structures without a global gap, such as GeTa31 and Bi22. The detailed characteristics of these topological materials are systematically cataloged in Table 1. Among them, the space group of the structure is determined using the SpacegroupAnalyzer method in the pymatgen54 package. A particularly noteworthy finding is the identification of nonmagnetic chiral crystals, including 3 Kramers-Weyl semimetals with space group P1 and 1 Kramers-Weyl semimetal with space group C2. These Kramers-Weyl semimetals represent a new category of materials, hosting Kramers-Weyl fermions at time-reversal-invariant momenta23,24. Kramers-Weyl fermions have attracted intense attention due to their unique physical properties including magneto-chiral dichroism62, large optical activity63,64, quantized chiral charges65 and negative longitudinal magnetoresistance66 due to the intricate interplay of SOC, structural chirality and time-reversal symmetry. The previous research efforts aimed at discovering new topological materials always relied on symmetry rules23,24, which met difficulties in dealing with low-symmetry as well as the chiral structures. However, our inverse design process, which does not rely on any symmetry-based rules, successfully identified a number of chiral structures with lower symmetry. This achievement underscores a significant advantage of our method, highlighting its potential to explore and uncover a broader spectrum of topological materials, particularly those with unconventional and complex structures.

In Fig. 4, we highlight four novel topological materials with their crystal structures, band structures, and phonon spectra, which are considered the most likely to be synthesized. Among them, CdAu5 (Fig. 4a, e, i) is a Kramers-Weyl semimetal with space group C2. In this material, the band splitting is observed at all points except at the time-reversal-invariant momenta. Li2YBi2 (Fig. 4b, f, j) and Zr2ScC (Fig. 4c, g, k) are both TSMs with space group \({\rm{P}}\bar{3}{\rm{m}}1\) and R3m, respectively. Mg4Pt2 (Fig. 4d, h, l) is presented as a TI, characterized by a set of topological invariant numbers: Z2w,1 = 1, Z2w,2 = 1, Z2w,3 = 1, Z4 = 2, Z2 = 0, Z8 = 6. The absence of any obvious imaginary frequencies in their phonon spectra corroborates their structural stability67. As an example of trivial band structures, Supplementary Fig. S4 presents the band structure and phonon spectra of crystal Ba2Sn4 generated by CTMT. This material, identified by TQC as a linear combination of EBRs (indicating trivial topology), is further confirmed to be stable through phonon analysis. The band structures of other topological materials identified in this study are available in Supplementary Fig. S5–S8, which provide detailed information on the structures and stability information of these materials.

Discussion

Overall, by systematically combining CDVAE, Topogivity rule, M3GNet, and TQC, we have successfully developed a novel data-driven method CTMT for the inverse design of new TI and TSMs based on deep generative models. This innovative approach has led to the discovery of 20 novel and stable topological materials, including 16 TSMs and 4 TIs. Compared with the traditional methods1,18,19 of directly determining the topology type of materials based on calculations, CTMT can reduce the calculation range to a smaller size and achieve higher accuracy while saving computational resources by preliminarily screening non-trivial materials based on Topogivity before calculation. In CTMT, the success rate of finding topological materials from stable materials is 62.5%, which is much higher than the traditional methods’ success rate of less than 30%. This outcome highlights the effectiveness of individual components within the CTMT framework in searching for new topological materials and proves the potential of CTMT in exploring all possible topological materials. Meanwhile, it is important to acknowledge that, due to the constraints related to computational accuracy and the stringent screening criteria applied for topology type and stability, there is a possibility that many potential topological materials within the generated dataset remain undiscovered. Our work opens up a novel and efficient path for finding groundbreaking topological materials, and holds great potential for the exploration of other advanced functional materials, such as topological superconductors, nodal line semimetals, and layered room temperature ferromagnetic materials. The future direction is to use topological properties as the generation condition in CTMT, so that it can consider both the stability of the crystal structure and the topological type of the material.

Methods

CDVAE training details

In this work, the dataset of topological materials was partitioned into training and validation subsets at a ratio of 8:2 for the CDVAE training. The backpropagation method was used in training with the Adam optimization algorithm and a learning rate set to 0.001. The training was completed after 800 epochs with the minimum loss on the validation set. During training, the hyperparameters are set to be consistent with those of the CDVAE training mp-20 dataset. The trained CDVAE model generates 10,000 candidates of potential topological materials, which are sent to a series of filters and thermodynamic stability checks by first-principles calculations based on DFT.

The CDVAE40 model we used in this word is implemented by Xie et al. (https://github.com/txie-93/cdvae). This model incorporates DimNet++68, adapted for periodicity as the encoder, and GemNet-dQ69 as the decoder. Both the encoder and decoder are invariant to structure changes, comprising 2.2 million and 2.3 million parameters, respectively. The training dataset is extracted from The Topological Materials Database website (https://www.topologicalquantumchemistry.fr) by using the request package (https://requests.readthedocs.io) in Python to collect the crystal structure information and topology type. After that, the crystal structure information is converted into a crystallographic information file (CIF), and the Structure package in pymatgen54 is used to feed the CIF into the CDVAE model. During training, we set the parameters of these networks with those used by Xie et al40. Additionally, due to the absence of formation energy data and the unpartitioned test set in the collected topological material dataset, we adopted the hyperparameters from the modified MP-20 dataset. The modifications are specified as follows: We set the predicted property (“prop” in the code) to “scaled_lattice” and set the number of targets (“num_targets” in the code) to 6. Furthermore, we excluded the test dataset configuration and limited the maximum training epochs (“train_max_epochs” in the code) to 800. The sampling process was conducted by executing the file at https://github.com/txie-93/cdvae/blob/main/scripts/evaluate.py. Before execution, we configured the model path to the saved model parameter path and set the “tasks” parameter to “gen”, which generated 10,000 candidate structures.

For the analysis involving Topogivity and M3GNet, we employed their pre-trained models. The Topogivity values were directly retrieved from Fig. 2 of Ref. 22, and we included these values in Fig. 2 of our work as well. The IAPs used in M3GNet for phonon filtering were obtained by loading the pre-trained model from MP-2021.2.8-EFS (https://github.com/materialsvirtuallab/m3gnet/tree/main/pretrained/MP-2021.2.8-EFS). Following this, we applied the structure relaxation demo from the M3GNet package (https://github.com/materialsvirtuallab/m3gnet) to preform relaxation on the selected structures and calculated the phonon spectra using the phonopy package.

Calculation parameter settings

The VASP is used to carry out the DFT calculations with the exchange-correlation potential of the generalized gradient approximation in the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerh type. The convergence criteria of energy and force are 10–6 eV and 0.01 eV/A, respectively and the cutoff energy for plane-wave expansion is 500 eV. The pre-trained M3GNet uses the 2×2 crystal superlattice cell and has the pre-sets of relaxation steps of 10,000 and a maximum force threshold of 0.0001 \({\rm{eV}}/{\text{\AA }}\). The phonon spectrum calculations employ the M3GNet force field and the phonopy packages70. The “Check topological mat” module from TQC method54 is integrated in CTMT and all calculations relevant to topological properties have been included with the SOC. The energy convergence precision is pre-set to 10-8 eV. This rigorous approach facilitates the categorization of structures into TSM, TI, and linear combination of EBRs, and the latter indicates a topological trivial state with the set of bands below the Fermi level1. The utilization of VASPKIT71 and the pymatgen packages54 significantly expedites efficiently the processing of DFT data.

Data availability

All data included in this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.

Code availability

All code included in this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.

References

Vergniory, M. et al. A complete catalogue of high-quality topological materials. Nature 566, 480–485 (2019).

Luo, H., Yu, P., Li, G. & Yan, K. Topological quantum materials for energy conversion and storage. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 611–624 (2022).

Fu, L. Topological crystalline insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 106802 (2011).

Hsieh, T. H. et al. Topological crystalline insulators in the SnTe material class. Nat. Commun. 3, 982 (2012).

Benalcazar, W. A., Bernevig, B. A. & Hughes, T. L. Quantized electric multipole insulators. Science 357, 61–66 (2017).

Lv, B. et al. Experimental discovery of Weyl semimetal TaAs. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031013 (2015).

Burkov, A., Hook, M. & Balents, L. Topological nodal semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 84, 235126 (2011).

Bradlyn, B. et al. Beyond Dirac and Weyl fermions: Unconventional quasiparticles in conventional crystals. Science 353, aaf5037 (2016).

Huang, Y., Yao, X., Qi, F., Shen, W. & Cao, G. Anomalous resistivity upturn in the van der Waals ferromagnet Fe5GeTe2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 162403 (2022).

Qi, X. L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011).

Hu, J., Xu, S.-Y., Ni, N. & Mao, Z. Transport of topological semimetals. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 49, 207–252 (2019).

Yan, B. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological materials. Rep. Prog. Phys. 75, 096501 (2012).

Sierra, J. F., Fabian, J., Kawakami, R. K., Roche, S. & Valenzuela, S. O. Van der Waals heterostructures for spintronics and opto-spintronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 856–868 (2021).

Xiao, J. & Yan, B. First-principles calculations for topological quantum materials. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 283–297 (2021).

Bansil, A., Lin, H. & Das, T. Colloquium: Topological band theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 021004 (2016).

Po, H. C., Vishwanath, A. & Watanabe, H. Symmetry-based indicators of band topology in the 230 space groups. Nat. Commun. 8, 50 (2017).

Bradlyn, B. et al. Topological quantum chemistry. Nature 547, 298–305 (2017).

Tang, F., Po, H. C., Vishwanath, A. & Wan, X. Comprehensive search for topological materials using symmetry indicators. Nature 566, 486–489 (2019).

Zhang, T. et al. Catalogue of topological electronic materials. Nature 566, 475–479 (2019).

Claussen, N., Bernevig, B. A. & Regnault, N. Detection of topological materials with machine learning. Phys. Rev. B 101, 245117 (2020).

Andrejevic, N. et al. Machine‐learning spectral indicators of topology. Adv. Mater. 34, 2204113 (2022).

Ma, A. et al. Topogivity: A machine-learned chemical rule for discovering topological materials. Nano Lett 23, 772–778 (2023).

Long, Y. & Zhang, B. Unsupervised data-driven classification of topological gapped systems with symmetries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 036601 (2023).

Singh, B., Lin, H. & Bansil, A. Topology and symmetry in quantum materials. Adv. Mater. 35, 2201058 (2023).

Liu, Y. & Shao, Q. Two-dimensional materials for energy-efficient spin–orbit torque devices. ACS Nano 14, 9389–9407 (2020).

Kurebayashi, H., Garcia, J. H., Khan, S., Sinova, J. & Roche, S. Magnetism, symmetry and spin transport in van der Waals layered systems. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 150–166 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Room temperature field-free switching of perpendicular magnetization through spin-orbit torque originating from low-symmetry type II Weyl semimetal. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg9819 (2023).

Noh, J., Gu, G. H., Kim, S. & Jung, Y. Machine-enabled inverse design of inorganic solid materials: promises and challenges. Chem. Sci. 11, 4871–4881 (2020).

Iovanac, N. C., MacKnight, R. & Savoie, B. M. Actively searching: inverse design of novel molecules with simultaneously optimized properties. J. Phys. Chem. A 126, 333–340 (2022).

Wang, J., Wang, Y. & Chen, Y. Inverse design of materials by machine learning. Materials 15, 1811 (2022).

Jabbar, R., Jabbar, R. & Kamoun, S. Recent progress in generative adversarial networks applied to inversely designing inorganic materials: A brief review. Comput. Mater. Sci. 213, 111612 (2022).

Lyngby, P. & Thygesen, K. S. Data-driven discovery of 2D materials by deep generative models. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 232 (2022).

Fung, V. et al. Atomic structure generation from reconstructing structural fingerprints. Mach. Learn.: Sci. Technol 3, 045018 (2022).

Kim, S., Noh, J., Gu, G. H., Aspuru-Guzik, A. & Jung, Y. Generative adversarial networks for crystal structure prediction. ACS Central. Sci. 6, 1412–1420 (2020).

Long, T. et al. Constrained crystals deep convolutional generative adversarial network for the inverse design of crystal structures. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 1–7 (2021).

Song, Y., Siriwardane, E. M. D., Zhao, Y. & Hu, J. Computational discovery of new 2D materials using deep learning generative models. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 53303–53313 (2021).

Noh, J. et al. Inverse design of solid-state materials via a continuous representation. Matter 1, 1370–1384 (2019).

Zhao, Y. et al. High-throughput discovery of novel cubic crystal materials using deep generative neural networks. Adv. Sci. 8, 2100566 (2021).

Ren, Z. et al. An invertible crystallographic representation for general inverse design of inorganic crystals with targeted properties. Matter 5, 314–335 (2022).

Xie, T., Fu, X., Ganea, O.-E., Barzilay, R. & Jaakkola, T. Crystal diffusion variational autoencoder for periodic material generation. International Conference on Learning Representations (2022).

Sohl-Dickstein, J., Weiss, E. A., Maheswaranathan, N. & Ganguli, S. Deep unsupervised learning using nonequilibrium thermodynamics. in Proc. 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning Vol. 37 (eds Bach, F. and Blei, D.) 2256-2265 (PMLR, 2015).

Song, Y. & Ermon, S. Generative modeling by estimating gradients of the data distribution. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. (Curran Associates Inc., 2019).

Batzner, S. et al. E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–11 (2022).

Kingma, D. P. & Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational Bayes. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2014).

Jiao, R., et al Crystal structure prediction by joint equivariant diffusion on lattices and fractional coordinates, In Workshop on ”Machine Learning for Materials” ICLR 2023. https://openreview.net/forum?id=VPByphdu24j (2023).

Luo, Y., Liu, C. & Ji, S. Towards symmetry-aware generation of periodic materials. Ad. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 36 (2024).

Lin, P. et al. Equivariant Diffusion for Crystal Structure Prediction. Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning (2024).

Moustafa, H., Lyngby, P. M., Mortensen, J. J., Thygesen, K. S. & Jacobsen, K. W. Hundreds of new, stable, one-dimensional materials from a generative machine learning model. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 014007 (2023).

Wines, D., Xie, T. & Choudhary, K. Inverse design of next-generation superconductors using data-driven deep generative models. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 6630–6638 (2023).

Chen, C. & Ong, S. P. A universal graph deep learning interatomic potential for the periodic table. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2, 718–728 (2022).

Krempaský, J. et al. Altermagnetic lifting of Kramers spin degeneracy. Nature 626, 517–522 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Superconductivity and nematic order in a new titanium-based kagome metal CsTi3Bi5 without charge density wave order. Nat. Commun. 15, 9626 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Topological thermal transport. Nat. Rev. Phys. 6, 554–565 (2024).

Ong, S. P. et al. Python Materials Genomics (pymatgen): A robust, open-source Python library for materials analysis. Comput. Mater. Sci. 68, 314–319 (2013).

Davies, D. W. et al. Computational screening of all stoichiometric inorganic materials. Chem 1, 617–627 (2016).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Batatia, I., Kovács, D. P., Simm, G. N., Ortner, C. & Csányi, G. MACE: higher order equivariant message passing neural networks for fast and accurate force fields. In Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 11423–11436 (Curran Associates, 2022).

Deng, B. et al. CHGNet as a pretrained universal neural network potential for charge-informed atomistic modelling. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 1031–1041 (2023).

Kovács, D. P., Batatia, I., Arany, E. S. & Csányi, G. Evaluation of the MACE force field architecture: from medicinal chemistry to materials science. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 044118 (2023).

Park, H., Gao, W., Zhang, X. & Oh, S. S. Nodal lines in momentum space: Topological invariants and recent realizations in photonic and other systems. Nanophotonics 11, 2192–8614 (2022).

Vergniory, M. G. et al. All topological bands of all nonmagnetic stoichiometric materials. Science 376, eabg9094 (2022).

Train, C. et al. Strong magneto-chiral dichroism in enantiopure chiral ferromagnets. Nat. Mater. 7, 729–734 (2008).

Hannam, K., Powell, D. A., Shadrivov, I. V. & Kivshar, Y. S. Broadband chiral metamaterials with large optical activity. Phys. Rev. B 89, 125105 (2014).

Zhao, R., Zhang, L., Zhou, J., Koschny, T. & Soukoulis, C. M. Conjugated gammadion chiral metamaterial with uniaxial optical activity and negative refractive index. Phys. Rev. B 83, 035105 (2011).

Chang, G. et al. Unconventional chiral fermions and large topological Fermi arcs in RhSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 206401 (2017).

Arnold, F. et al. Negative magnetoresistance without well-defined chirality in the Weyl semimetal TaP. Nat. Commun. 7, 11615 (2016).

Parlinski, K., Li, Z. & Kawazoe, Y. First-principles determination of the soft mode in cubic ZrO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 4063 (1997).

Gasteiger, J., Groß, J. & Günnemann, S. Directional Message Passing for Molecular Graphs. International Conference on Learning Representations (2020).

Gasteiger, J., Becker, F. & Günnemann, S. Gemnet: Universal directional graph neural networks for molecules. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst 34, 6790–6802 (2021).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scripta Materi. 108, 1–5 (2015).

Wang, V., Xu, N., Liu, J.-C., Tang, G. & Geng, W.-T. VASPKIT: A user-friendly interface facilitating high-throughput computing and analysis using VASP code. Comput. Phys. Commun. 267, 108033 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 92365105, 52130204, 12311530675), the Department of Science and Technology of Zhejiang Province (Grant no. 2023C01182), and the Shanghai Engineering Research Center for Integrated Circuits and Advanced Display Materials.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.C. designed the project. T.H. constructed the inverse design process and wrote the code for the topological materials project. T.C., D.J., Y.Z., and H.G. conducted the calculations. T.H. and T.C. analyzed and organized the results. T.H. and T.C. wrote the first draft. G.C., K.Z., W.R., and T. Z discussed the results and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, T., Chen, T., Jin, D. et al. Discovery of new topological insulators and semimetals using deep generative models. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 12 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00731-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00731-0

This article is cited by

-

Materials discovery acceleration by using conditional generative methodology

npj Computational Materials (2025)

-

Influence of superconductor dirtiness on the SNSPD sensitivity-bandwidth trade-off

Applied Physics A (2025)

-

On topological aspects of phosphorus dendrimers using edge cut method

Chemical Papers (2025)

-

A machine learning study to predict long range order/disoroder of organic semiconductors: a study on maintaining delicate crystallinity balance

Indian Journal of Physics (2025)