Abstract

The layered cobaltate CaCoO2 exhibits a unique herringbone-like structure. Serving as a potential prototype for a new class of complex lattice patterns, we study the properties of CaCoO2 using X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS). Our results reveal a significant inter-plane hybridization between the Ca 4s- and Co 3d- orbitals, leading to an inversion of the textbook orbital occupation of a square planar geometry. Further, our RIXS data reveal a strong low energy mode, with anomalous intensity modulations as a function of momentum transfer close to a quasi-static response. These findings indicate that the newly discovered herringbone structure exhibited in CaCoO2 may serve as a promising laboratory for the design of materials having strong electronic, orbital and lattice correlations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advancements in materials science have underscored how structural motifs dictate the properties and functionalities of complex materials1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Here, we examine the newly discovered infinite layer material CaCoO2 which features a unique super-structure11. Using X-ray absorption and resonant inelastic X-ray scattering12, we uncover an inversion of the Co 3d-orbital occupations resulting from a significant inter-plane hybridization between Ca 4s − and Co 3d − orbitals. Additionally, we find a strong lattice vibrational mode having an intensity modulation near a structurally forbidden satellite peak. This suggests the presence of strong electron-lattice correlations which may aid in stabilizing the Ångstrom-scale lattice distortions seen in CaCoO2. Our work establishes this infinite-layer compound as a novel platform for the investigation of orbitally engineered systems inhabited by strong correlation effects.

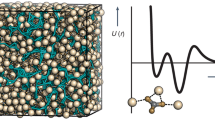

Among infinite layer transition metal oxides which are known for hosting a variety of complex quantum phenomena1,8,11,13,14,15CaCoO2 stands out due to its unique crystal structure11. This structure emerges upon reducing the Brownmillerite parent compound CaCoO2.5 via removal of its apical oxygen, in a similar fashion as the nickelate superconductors8. In contrast to its Ni-based siblings, however, CaCoO2 does not collapse into a simple square-planar geometry but exhibits large displacements in both the Co-O bonds as well as the Ca layer [Fig. 1a]. This leads to three distinct Co sites, each experiencing different effective ligand fields, which modify the Co2+ electronic configuration with 7 electrons distributed in the 3d − orbitals11, resulting in three types of locally distorted CoO2 plaquettes. With anomalously large, Å-sized CoO2 distortions, the pseudo-cubic unit cell reconstructs into an enlarged and geometrically frustrated \(2\sqrt{2}\times 2\sqrt{2}\times 1\) superstructure. While DFT + U calculations reproduce the overall crystal symmetry11, they fail to match the values of the lattice distortions quantitatively. The experimental magnitude of these distortions alongside the quantitative disagreement with ab initio theoretical results indicate that additional factors, for instance strong correlation effects both between charge carriers and with the lattice, might be at play.

a Top view of the infinite-layer cobaltate CaCoO2 showing Ca atoms in blue, Co atoms in black and O atoms in red. Three distinct cobalt sites are identified as two distorted (blue Co(1) and green Co2) and a rotated, undistorted site (yellow Co(3)). The panel was created using Vesta26. b Experimental X-ray absorption (XAS) results taken in total electron yield (TEY) for photon polarizations perpendicular (σ, blue) and parallel (π, red) to the scattering plane, at an incident angle of θin = 20°. The black curve corresponds to the linear dichroism Idic = Iσ − Iπ, i.e. the difference of the signal in the two polarization channels. c, d Experimental data reproduced from panel b along with the dashed magenta lines which correspond to multiplet simulations using exact diagonalization. e Energy ordering of the Co 3d − orbitals for square planar geometry (left). Hybridization of the Ca 4s − orbitals pushes the 3dxy − and \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}-\) orbitals to lower energy, leading to finite hole content in the 3dxz,yz − orbitals. Ωi is the incident photon energy given in electron-Volts (eV).

Results and Discussion

Orbital inversion

The electronic structure can be inferred from the rich multiplet splitting of the Co L3 − edge XAS [Figure 1b], providing a basis for formulating an effective low energy model. A strong dependence of the incident photon polarization can be seen when tuned either parallel (π) or perpendicular (σ) to the scattering plane. The two polarization channels highlight distinct multiplet structures at associated incident energies which is more apparent in the difference spectrum shown in Fig. 1b. This dichroism highlights that the structural anisotropy plays a key role in its electronic structure. On a qualitative level, the strong dichroism indicates that the orbital structure of CaCoO2 hosts empty states having z − components, since the σ and π photon polarizations in our experimental geometry highlight projected weights of the 3d − orbitals in- and out-of-the CoO2 plane, respectively. In CaCoO2, however, we find the experimentally observed multiplet splitting cannot be reproduced via exact diagonalization (ED) calculations using the expected orbital energetic sequence of a square planar geometry seen in Fig. 1e [ED simulations in Supplementary Fig. 1]. Although the observed in-plane distortion may lift the degeneracy of the dxz and dyz orbitals, this does not explain the presence of a low-energy feature in the σ channel that is absent in the π channel of our experiment. This suggests that the dxz/dyz orbitals – contributing to both channels in our experimental geometry– do not host the material’s lowest energy hole states, and, in fact, it is the dxy orbital, exclusively sensitive to the σ channel, that is the lowest energy empty state.

In the absence of any other apical atomic species that could cause such a change of the orbital occupations, we propose that strong overlap between Ca 4s − and Co 3d − orbitals, facilitated by a collapsed c-axis lattice constant, which brings the Ca ions closer to the CoO planes, plays a significant role in reordering the orbital sequence, resulting in the observed dichroism. Considering the phase factors of the Co 3d − orbitals, the strongest overlap with the 4s − orbital is expected to occur with the dxy − and \({d}_{{z}^{2}}-\) orbitals. This overlap leads to an effective orbital inversion of the dxz,yz − with the dxy − orbital occupations.

We account for these effects in modeling the complexity of the Co2+ multiplet structure, including the possibility of site-dependent distortions which may contribute to differences in splitting and orbital configuration. Our ED simulations [see Methods: Section c] explicitly model all three Co sites with distinct parameters [cf. Table T1], i.e. crystal field splitting in addition to hybridization with the Ca 4s − orbitals [Fig. 1c, d]. The comparison between our experimental results and these simulations supports the general schematic for the local electronic structure shown in Fig. 1e, where the holes are mainly distributed in the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}-\) and half-filled dxz,yz − orbitals, with the 4s − orbitals remaining nearly unoccupied. This combined experimental and theoretical approach suggests that the observed distortion may be at the very least stabilized, and possibly even driven, by a strong interlayer hybridization.

These results are also consistent with the orbital excitation spectrum seen in RIXS: Fig. 2 illustrates the RIXS response for the two different polarization channels σ and π with several clusters of excitations visible. We find peak structures in two bands from 300 meV to up to 1.2 eV and again from 1.2 to 2.8 eV followed by a broad response extending to 4.0 eV [Fig. 2c, d]. These excitations can be identified as intra-atomic dd − excitations and are consistent with ED calculations [Fig. 2e, f] obtained from the electronic structure model described in Fig. 1. Zooming in closer to a 300 meV energy scale [Fig. 2g, h], there is a strong feature on a 40 meV scale, followed by a broad band of excitations. These low energy excitations are not captured by the ED simulations [insets of Fig. 2g, h], and thus cannot be attributed to dd − excitations.

a, b Experimental results for σ- and π − polarization. c, d Line-cuts of the experimental color maps at Ωi = 776.85 eV. e, f RIXS plots of the ED calculations using the electronic model presented in Fig. 1 to simulate the XAS response. g, h Same data as in c, d zoomed to smaller energy transfer showing low energy features not captured by the simulations (insets). The energy transfer is given as ω in electron-Volts (eV).

Emergent lattice dynamics

We first focus our discussion on the sharp low energy mode with an energy scale of 40 meV. Considering that the energy scale is consistent with typical oxygen phonons in other 3d − transition metal oxides, the most likely scenario is that the mode represents lattice vibrations with oxygen character. Figure 3a, b displays the RIXS intensity map at low energy as a function of the incident photon energy. The 40 meV mode has a strong resonance across the Co L3-edge for both polarization channels, with a clear difference in the intensity distribution [Fig. 3c]: the mode sharpens for π − polarization, and shows an intensity maximum at a specific incident energy of 776.75 eV [Fig. 3d, e]. The resonant profile of the mode has a maximum at an energy where the partial XAS associated with the undistorted Co site also contributes more significantly [see cf. Supplementary Fig. 2], indicating locally stronger coupling of this mode to that Co-site.

a σ − polarization. b π-polarization. Filled markers in a and b correspond to the results of a fitting procedure. c Linecuts at incident energies Ωi as indicated. A strong feature off of the elastic line is visible, followed by broad features at higher energy. d, e Intensity distribution of the mode across the L3 − edge for σ − and π − polarization (black markers) and of the higher energy feature (red markers) centered at ~ 180 meV. The mode intensity peaks at an energy corresponding to the XAS maximum of the square planar site for π − polarization. The intensities correspond to the results of the fitting procedure seen in Supplementary Figure S3 and S4.

As depicted in Fig. 3d,e, the broad-band excitations observed within the 100–250 meV energy range exhibit resonant profiles that closely track the XAS spectrum and differ markedly from those of the 40 meV mode. This disparity in resonant behavior suggests that these excitations are unrelated to the 40 meV mode. Given the insulating nature of CaCoO2 and the significant structural distortions, these broad features may arise from polaronic interactions16,17. Such coupling is expected to be prominent in insulating systems with pronounced distortions, leading to slower charge dynamics. Furthermore, excitonic states cannot be excluded as potential contributors to these excitations, given that the particle-hole RIXS final state could exhibit extended lifetime due to an energy scale on the order of the band gap deduced from transport measurements. A comprehensive discussion about the nature of these excitations necessitates further investigation beyond the purview of this study. Accordingly, the remainder of this work will concentrate on a detailed analysis of the sharp 40 meV mode.

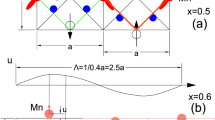

The momentum dependence of the sharp mode along different high symmetry directions in the Brillouin zone, depicted in Fig. 4, corroborates its assignment as a phonon mode and rules out a magnetic origin, whose dispersion should emanate from ω = 0 at zone center, before reaching a maximum at some finite momentum, and terminate at ω = 0 approaching the magnetic ordering vector. Here, along the pseudo-cubic (h,0)-direction [Fig. 4a], the mode disperses from close to zone center at ~ 35 meV, raising to 45 meV before slightly bending downwards. Similarly, the response along the (h,k)-direction shows a small slope [Figure 4b], as does the out-of-plane component [Fig. 4c], indicating that the mode corresponds to an optical phonon branch.

a–c Momentum dependence of the low energy mode along the (h,0), (h,k) and l-direction of the pseudo-cubic unit cell in r.l.u. (reciprocal lattice units). The measurements along the l-direction were taken at fixed in-plane momentum (-0.05, -0.05) r.l.u. d–f Intensity distribution of the elastic line and the mode. See Table T2 for h, k, l − values.

The scattering intensity of this phonon branch features a strong increase in intensity close to qO = (1/4, 1/4) r.l.u., where the quasi-elastic intensity also exhibits a peak-like feature [Fig. 4b, e]. Wavevector qO reflects the periodicity of the large superstructure of CaCoO2 (Fig. 1a), which could contribute to the enhancement of the quasi-elastic intensity due to Templeton-Templeton scattering18 under resonant conditions, despite that (1/4, 1/4, 0) is a forbidden lattice Bragg reflection11. Whether there exists some form of electronic order, such as orbital and/or charge order, that coincides with the superstructure and contributes to the elastic peak enhancement, remains an intriguing question for future investigation, as does the fact that the phonon intensity shows a similar enhancement at qO. We do note that the phonon intensity in RIXS is a measure of the charge-lattice coupling strength19,20,21, and as such the phonon intensity modulation at qO may indicate a spatially dependent coupling which could reinforce the structural distortions in CaCoO2. In other words, intertwined orbital, charge, and lattice contributions—strong hybridization, potential formation of some electronic order, and enhanced charge-lattice coupling—could reduce the free energy and contribute to the large distortions seen in CaCoO2.

As previously discussed in Fig. 3d, e this phonon couples strongly to the un-distorted Co site among the three environments, which itself is rotated concomitantly with the Ca cage. To speculate on its importance, the orbital inversion facilitated by the strong Ca hybridization with this Co site may be a key factor in the formation of the large superstructure and the assocaited spatial modulation of the 3d − orbitals. Such a lattice-enforced orbital inversion in CaCoO2 would be quite unique, absent in infinite-layer nickelates and cuprates, and rare even among other transition metal oxides. This aspect calls for a more thorough investigation of the CaCoO2 compound. We note that previous DFT calculations may underestimate the electron-lattice coupling, as the effect of orbital inversion may not be fully accounted for with the prediction of such a small distortion11. Our results also place additional constraints on the formulation of an effective model for the CaCoO2 system.

The orbital inversion observed in CaCoO2 reflects a broader theme in quantum materials, namely the influence of lattice distortions and interlayer interactions on the electronic structure. Systems such as Sr2IrO4 and Sr2RuO4 reveal how small structural perturbations can dramatically alter electronic and magnetic properties22,23,24. Similarly, in Nb3Cl8, lattice distortions stabilize a Mott-insulating state, showcasing the interplay of Coulomb interaction and structural degrees of freedom25. In this context, the hybridization-driven orbital inversion in CaCoO2 emphasizes the importance of interlayer coupling in stabilizing unconventional orbital configurations.

The insight gained from the orbital inversion and hybridization effects in CaCoO2 may also inspire future studies on related systems, such as SrCoO2. The substitution of Sr for Ca, with its larger ionic radius, could enhance orbital overlap and potentially lead to more dramatic effects on the electronic structure.

In summary, the herringbone structure of CaCoO2 represents a compelling new platform for manipulating and studying exotic material properties. The orbital inversion facilitated by the Ca hybridization could imprint distinct features on the electronic structure, potentially paving the way towards engineered topology. Moreover the spectroscopic fingerprints of strong electronic and lattice correlations raises questions about the effects of doping on the transport properties of CaCoO2, in particular, whether the orbital inversion, quasistatic order, and the super-cell persist with doping and whether superconductivity can emerge, like in its infinite-layer nickelate and cuprate cousins. These possibilities underscore the promising outlook for CaCoO2 in future material science research.

Methods

Sample synthesis

Pulsed laser deposition was used to grow a 20 nm thin film of the parent Brownmillerite compound CaCoO2.5 on a SrTiO3 (001) substrate. The films were capped with five unit cells of SrTiO3 layers to prevent potential degradation during the reduction process. The precursor CaCoO2.5 films were then reduced to the infinite layer CaCoO2 system through topotactic reduction11.

X-ray scattering

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) and Resonant Inelastic X-ray Scattering (RIXS) measurements were performed at beamline i21 of the Diamond Light Source, United Kingdom. For the incident energy maps, the photon energy was tuned across the Co L3 − edge as measured from XAS. The incident photon polarization was set either parallel (π) or perpendicular (σ) to the scattering plane. The combined energy resolution was 36 meV. The momentum dependent measurements were conducted along the (h,0), (h,k) and (−0.05,−0.05, l) directions with units given in reciprocal lattice units (r.l.u.) of the pseudocubic unit cell, having lattice parameters a = b = 3.9 Å, c = 3.27 Å with conversions (2π/a, 2π/b, 2π/c). The scattering angle was fixed to 154° for the measurements along (h,0) and (h, k) and varied for measurements along the (−0.05,−0.05,l) direction. The temperature for all measurements was set to 21 K.

Exact Diagonalization of Charge Transfer and Hybridization Full Atomic Multiplet (CTHFAM)

To model the various local electronic environment of Co in this material, we exactly diagonalize a full atomic multiplet including charge transfer and hybridization effects of a Co transition metal center (5 d orbitals), 2 oxygen ligands (3 p orbitals each) and one Ca ligand (1 s orbital). The single site is centered at (π/2, π/2) in momentum. From the formal valence of CaCoO2, Co+2 and Ca+2 each contribute 3 and 2 holes, respectively. From this configurational space, the interactions are represented by the following Hamiltonian:

Where i, j refer to the different atomic sites, μ, ν refer to different sets of l, m quantum numbers, and σ refers to spin. The first term includes a Hubbard-like U term for the coulomb interaction where all Co sites exhibit a Udd = 5.44 and JH = 0.9, typical values for TM oxides. The second term includes a t hopping element between different atomic sites and their orbitals. The third term includes a square planar crystal field (Δo) for the d-orbtials in the metal atom, the fourth term is the core-valence coulumb interaction, the fifth term is the spin-orbit coupling λ at the core and the last term is the charge transfer energy Δ at each atomic site. For a list of the parameters used to model each of the three different cobalt environments, see Table T1. The multi-particle eigenstates for a Hamiltonian of an N hole cluster and one for a N-1 hole cluster with a core hole serve as the initial (i), intermediate (ν), and final (f) states for the calculation of XAS by Fermi’s golden rule:

And for RIXS using the Kramers-Heisenberg representation:

Where Ei,ν,f refers to the eigenenergy and \({D}_{{k}_{i}}({e}_{i})\) is the dipole operator for a photon of frequency ω, momentum k and polarization e, and Ω = ωi − ωf. A core-hole lifetime Γ broadening of 0.2 eV was used for the plotting of theoretical XAS/RIXS maps. A global energy shift for each site was also added to all calculated spectral features for ease of comparison with experiment. The final simulated spectra was constructed using 1/2/1 ratios for the distinct Co sites individual simulations, based on how many of each site is found on the unit cell of the material. An average over X and Y incoming photon polarizations were used for the simulation of the fully in-plane σ -polarization experiments, and the mostly out-of-plane π -polarization experiments were simulated with 87% contribution of Z photon polarization and 93% in-plane contribution for XAS and with 7% contribution of Z photon polarization and 13% in-plane contribution for RIXS, based on the experimental set up and incident angle for each measurement.

Code availabillity

The code used for this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Takada, K. et al. Superconductivity in two-dimensional COO2 layers. Nature 422, 53 (2003).

Roger, M. et al. Patterning of sodium ions and the control of electrons in sodium cobaltate. Nature 445, 631 (2007).

Senn, M. S., Wright, J. P. & Attfield, J. P. Charge order and three-site distortions in the Verwey structure of magnetite. Nature 481, 173 (2012).

Green, M. A., Ho-Baillie, A. & Snaith, H. J. The emergence of perovskite solar cells. Nat. Photonics 8, 506 (2014).

Stoerzinger, K. A., Choi, W. S., Jeen, H., Lee, H. N. & Shao-Horn, Y. Role of strain and conductivity in oxygen electrocatalysis on LaCoO3 thin films. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 487 (2015).

Yu, X. et al. Graphene-based smart materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17046 (2017).

Burch, K. S., Mandrus, D. & Park, J.-G. Magnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals materials. Nature 563, 47 (2018).

Li, D. et al. Superconductivity in an infinite-layer nickelate. Nature 572, 624 (2019).

Xu, R. et al. Strain-induced room-temperature ferroelectricity in SrTiO3 membranes. Nat. Commun. 11, 3141 (2020).

Wang, Y., Wu, H., McCandless, G. T., Chan, J. Y. & Ali, M. N. Quantum states and intertwining phases in kagome materials. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 635 (2023).

Kim, W. J. et al. Geometric frustration of Jahn-Teller order in the infinite-layer lattice. Nature 615, 237 (2023).

Ament, L. J. P., van Veenendaal, M., Devereaux, T. P., Hill, J. P. & van den Brink, J. Resonant inelastic x-ray scattering studies of elementary excitations. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 705 (2011).

Siegrist, T., Zahurak, S. M., Murphy, D. W. & Roth, R. S. The parent structure of the layered high-temperature superconductors. Nature 334, 231 (1988).

Tsujimoto, Y., Hayashi, N., Matsushita, Y. & Takayama-Muromachi, E. Infinite-layer iron oxide SrFeO2: A ferromagnetic metallic oxide. Nature 450, 1062 (2007).

Kawakami, T. et al. Spin transition in a four-coordinate iron oxide. Nat. Chem. 1, 371 (2009).

Geondzhian, A. et al. Large polarons as key quasiparticles in SrTiO3 and SrTiO3-based heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 126401 (2020).

Jost, D. et al. Low temperature dynamic polaron liquid in a manganite exhibiting colossal magnetoresistance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 186502 (2024).

Templeton, D. H. & Templeton, L. K. X-ray dichroism and polarized anomalous scattering of the uranyl ion. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 38, 62 (1982).

Ament, L. J. P., van Veenendaal, M. & van den Brink, J. Determining the electron-phonon coupling strength from Resonant Inelastic X-ray Scattering at transition metal L-edges. Europhys. Lett. 95, 27008 (2011).

Devereaux, T. P. et al. Directly characterizing the relative strength and momentum dependence of electron-phonon coupling using resonant inelastic X-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. X 6, 041019 (2016).

Braicovich, L. et al. Determining the electron-phonon coupling in superconducting cuprates by resonant inelastic x-ray scattering: Methods and results on Nd1+xBa2−xCu3O7−δ. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 023231 (2020).

Paris, E. et al. Strain engineering of the charge and spin-orbital interactions in Sr2IrO4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 24764 (2020).

Steppke, A. et al. Strong peak in Tc of Sr2RuO4 under uniaxial pressure. Science 355, eaaf9398 (2017).

Profe, J. B., Beck, S., Kennes, D. M., Georges, A. & Gingras, O. Competition between d-wave superconductivity and magnetism in uniaxially strained Sr2RuO4. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 53 (2024).

Grytsiuk, S., Katsnelson, M. I., Loon, E. G. V. & Rösner, M. Nb3Cl8: a prototypical layered Mott-Hubbard insulator. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 8 (2024).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division. XAS and RIXS measurements were performed at beamline I21, Diamond Light Source (UK). D.J. gratefully acknowledges funding by the Alexander-von-Humboldt foundation. Aspects of the materials development were supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s Emergent Phenomena in Quantum Systems Initiative (grant no. GBMF9072). Computational work was performed on the Sherlock cluster at Stanford University and on resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility, using NERSC award BES-ERCAP0027203.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.J. and W.S.L. conceived the experiment and analyzed the data. W.J.K. synthesized the samples. D.J., M.R., S.A., K.Z., and W.S.L. performed the experiments. E.G.L., E.M.B., C.J., B.M., and T.P.D. performed the theory work. Z.X.S., H.Y.H., T.P.D., and W.S.L. supervised the project. All authors contributed to the interpretation. D.J. and W.S.L. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jost, D., Lomeli, E.G., Kim, W.J. et al. Orbital inversion and emergent lattice dynamics in infinite layer CaCoO2. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 60 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00778-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00778-z