Abstract

It is a distinct possibility that spin fluctuations are the pairing interactions in numerous unconventional superconductors. In the high-transition-temperature (high-Tc) cuprates, superconductivity emerges upon doping antiferromagnetic Mott insulators, and spin fluctuations might furthermore drive unusual pseudogap phenomena. Here we use magnetic neutron scattering to study the highly underdoped cuprate HgBa2CuO4+δ (hole concentration p ≈ 0.064). In contrast to prior results for other underdoped cuprates, we find no evidence of incommensurate magnetic order associated with spin-density-wave or stripe correlations. Instead, the antiferromagnetic response in both the superconducting and pseudogap states is gapped below ΔAF ≈ 6 meV, commensurate over a wide energy range, and disperses above about 55 meV. Given the pristine nature of HgBa2CuO4+δ, which exhibits high structural symmetry and minimal point disorder effects, this behavior likely signifies the unmasked response of the underlying CuO2 planes near the Mott-insulating state. These results serve as a benchmark for a refined theoretical understanding of the cuprates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

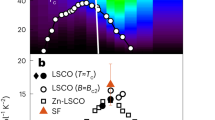

The cuprate superconductors share a quintessential structural and electronic unit: the copper-oxygen plane. The parent insulating state is characterized by a large Cu 3d-O 2p charge-transfer gap (~1–2 eV)1, a spin-1/2 Cu moment2, and quasi two-dimensional (2D) antiferromagnetic (AF) spin correlations with a large superexchange energy (~130 meV)3,4. Superconductivity emerges upon doping the planes with about p ~ 0.05 holes per planar Cu. Below optimal doping (p ~ 0.16), where Tc is largest, the superconducting (SC) phase is preceded by the pseudogap (PG) region at higher temperature (Fig. 1); the latter has been the subject of much research activity and found to exhibit myriad ordering phenomena (translational-symmetry-preserving q = 0 magnetism, charge-density-wave, charge-spin stripe, electron-nematic)5. Since spin correlations might drive both superconductivity6,7 and some of the observed PG phenomena8,9,10, it is imperative to determine the magnetic response of the pristine CuO2 planes. Indeed, the past four decades have seen tremendous efforts toward this end. Regardless of the nature of the pairing mechanism, a successful theory of the cuprates ought to capture the spin dynamics of these quantum materials.

a Phase diagram of Hg1201 (p > 0.04), extended to the undoped insulating state (p = 0) based on data for other cuprates29, with antiferromagnetic (AF), superconducting (SC), pseudogap (PG) and Fermi-liquid (PG + FL) phases/regions. Lines indicate the characteristic pseudogap temperatures T* and T** and superconducting transition temperature Tc obtained from charge transport measurements43, and the approximate Néel temperature TN. Red triangles: temperature TAF below which the response centered at qAF is significantly enhanced (present work and refs. 27,28); purple squares; onset of q = 0 magnetic order from polarized neutron diffraction35,36,37; brown diamonds: onset of nematic order from torque magnetometry59; yellow and orange circles: characteristic temperatures of the onset of short-range charge-density-wave (CDW) order obtained from X-ray29 and optical60 measurements. At the doping level of the present study (p \(\approx\) 0.064, indicated by the arrow), CDW correlations are weak. b Schematic diagrams of magnetic excitation spectra for Hg1201-UD55 (present work), Hg1201-UD7128, and Hg1201-UD8827 at two temperatures (above and below Tc), showing the characteristics of the magnetic dispersion as a function of energy (vertical) and momentum transfer centered at qAF (horizontal). The circle indicates the presence of a resonance in Hg1201-UD88, near optimal doping.

Neutron scattering is a powerful probe of the full momentum- and energy-dependent magnetic response of a material, i.e., the scattering cross-section is proportional to the imaginary part of the dynamic magnetic susceptibility, χ″(Q,ω), where Q and ω are the momentum and energy transfer to the scattering system, respectively. Due to limitations in the attainable flux even at the best neutron sources, a measurement of the spin dynamics typically requires sizable crystals, especially in the case of low-dimensional systems and in the extreme quantum limit of spin-1/2, due to sizable quantum fluctuations. For the cuprates, this has largely constrained studies of the magnetic response to two systems for which such crystals have been available11,12,13,14: La2-xSrxCuO4 (LSCO) and related compounds, as well as YBa2Cu3O6+δ (YBCO). Key features revealed by these studies are: (i) in YBCO, a normal-state excitation gap (ΔAF) at the antiferromagnetic wave-vector that increases with increasing doping in the SC doping range; (ii) an hourglass-shaped normal-state dispersion that is less pronounced in YBCO than in LSCO; (iii) in the case of YBCO, a resonance upon cooling into the SC state; (iv) near p ~ 1/8, LSCO and the closely related (La,Nd)2−x(Sr,Ba)xCuO4 compounds exhibit a pronounced instability toward stripe order, with incommensurate magnetic correlations, that is stabilized in a low-symmetry structural phase. Incidentally, below p ~ 0.085, YBCO exhibits quasistatic incommensurate spin-density-wave (SDW) correlations15. Whereas the high-energy response (the upper part of the hourglass) in both compounds resembles the spin-wave dispersion seen in the insulating parent state, the considerable differences observed below about 50 meV have raised questions regarding the nature of the underlying magnetic response of the CuO2 planes in the absence of compound-specific idiosyncrasies. This issue has not been resolved through more limited neutron scattering studies of several other cuprates12,13—Bi2Sr2CuO6+x (Bi2201), Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+x (Bi2212), and Tl2Ba2CuO6+δ (Tl2201). Note that 50 meV is an important energy scale, as it is comparable to both the PG and SC gap scales near optimal doping16.

There are good reasons to think that HgBa2CuO4+δ (Hg1201) is a model system17,18,19,20, as it features the highest optimal Tc (nearly 100 K) of all single-CuO2-layer cuprates (such as LSCO, Bi2201, Tl2201), higher also than the corresponding values for double-layer YBCO and Bi221221. Moreover, unlike YBCO and LSCO, which exhibit low orthorhombic structural symmetry (in the entire SC doping range of YBCO, and up to p ~ 0.22 in the case of LSCO), Hg1201 maintains high tetragonal symmetry21. Finally, point disorder effects are rather prominent in LSCO and cause an insulator-like low-temperature resistivity upturn below optimal doping. Such effects have not been observed for Hg1201 in samples with doping levels as low as p ~ 0.055 (Tc ~ 45 K)22,23, and although less prominent in YBCO, they are present in the doping range where SDW correlations are observed (below p ~ 0.085)24. Notably, in YBCO, both the resistivity upturn25 and the incommensurate magnetic order26 are dramatically enhanced (up to at least p = 0.12) with intentionally introduced point disorder. The degree to which the underlying electronic properties of the CuO2 planes can be masked by low structural symmetry and/or point disorder effects (e.g., through the stabilization of secondary electronic phases) is exemplified by a study20 that uncovered that: Hg1201 obeys conventional Kohler scaling of the magnetoresistance deep in the PG state, with a Fermi-liquid T2 scattering rate; in the case of YBCO, this simple metallic behavior is only seen in de-twinned samples, for charge-current flow perpendicular to the Cu-O chains characteristic of this particular compound; in LSCO, Bi2201 and Bi2212, this simple underlying scaling behavior is masked even more strongly. In this context, it is important to note that theoretical treatments of the cuprates generally avoid consideration of the added complexity due to non-universal disorder effects and deviations from tetragonal symmetry.

In recent years, sizable samples of Hg1201 have become available. Initial neutron scattering work revealed a gapped AF response near optimal doping (p ~ 0.13, Tc = 88 K; sample denoted Hg1201-UD88) similar to YBCO, with a magnetic resonance and an hourglass-shaped dispersion in the SC state27. In stark contrast, a second study at somewhat lower doping (p ~ 0.09, Tc = 71 K; Hg1201-UD71) revealed an unusual, gapped wineglass-shaped response that is hardly altered upon cooling into the SC state28. Since CDW correlations are particularly robust at the doping level of the latter study (Fig. 1), it has remained unclear if the observed behavior is a mere peculiarity associated with the prominence of the CDW phenomenon. It is therefore highly desirable to determine the magnetic response of Hg1201 at lower doping, where CDW order is weak29.

Here, we present a detailed neutron scattering study of a strongly underdoped Hg1201 sample (p ≈ 0.064 and Tc ≈ 55 K; Hg1201-UD55) and uncover the underlying magnetic response of the CuO2 planes below ~140 meV near the parent insulating state. As in the prior measurements of the AF excitations in Hg1201 at higher doping, we primarily report time-of-flight results27,28. In order to confirm the magnetic nature of the response, we also present complementary triple-axis data with neutron polarization analysis. We find dynamic, wineglass-shaped AF correlations with little change across Tc, closely similar to the prior result for Hg1201-UD71, but with a much smaller normal-state excitation gap of ΔAF ≈ 6 meV. Furthermore, we observe no signs of stripe/SDW and q = 0 magnetic order; the former observation is distinct from prior findings for other cuprates near the studied doping level, while the latter result is consistent with prior work for YBCO30,31,32. Motivated by recent neutron scattering results for LSCO33, we carry out density-functional theory (DFT) phonon calculations to address the possibility that the spin excitations in Hg1201 are coupled to the lattice dynamics at select energies. We find no evidence of significant intrinsic lattice effects.

Results

Figure 2a shows contour plots of \(\chi ^{{\prime} {\prime}} \left({\bf{Q}},{{\upomega }}\right)\) at select energy transfers ω and temperatures T = 5, 70, and 410 K, obtained with incident neutron energies Ei = 70 and 200 meV using the same data analysis method as described previously27,28 and in the Supplementary Information. We quote the three-dimensional scattering wave-vector Q = Ha* + Kb* + Lc* ≡ (H K L) in reciprocal lattice units, where a* = b* = 1.62 Å−1 and c* = 0.66 Å−1 are the room-temperature values. Given the lamellar nature of the cuprates, we are interested in the 2D magnetic response. Data such as those in Fig. 2a are therefore fit to the heuristic gaussian function χ″(Q) = \({\chi }_{0}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\exp \{-4\mathrm{ln}2R/{\left(2\kappa \right)}^{2}\}\), where R = | [(H − 1/2)2 + (K − 1/2)2]1/2 – δ | 2, \(2\kappa\) is the intrinsic full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) momentum width, and δ parameterizes the incommensurability relative to the 2D AF wave-vector qAF = (1/2 1/2). Corresponding constant-ω momentum trajectories, averaged over {100} and {010} with lateral momentum-bin range q⊥ = [0.45, 0.55] r.l.u., are shown in Fig. 2b. The overall response at T = 5 K and 70 K, extracted from the fits up to ~135 meV, is shown in Fig. 2c. \(\chi ^{{\prime} {\prime}} \left({\bf{Q}},{{\upomega }}\right)\,\) changes from dispersing to commensurate below ωc ≈ 55 meV, and becomes immeasurably small below ΔAF ≈ 6 meV. At 410 K, the response is considerably weaker, yet consistent with these observations.

a Constant-energy slices of magnetic susceptibility \(\chi^{\prime\prime}\) (q) as a function of the 2D in-plane momentum transfer q = (H K) at T = 5 K (left), 70 K (center), and 410 K (right), in units of µB2 eV−1 f.u.−1 (same color scale as c). Data averaged over indicated energy (ω) ranges. White text indicates that \(\chi^{\prime\prime}\) has been multiplied by a factor to highlight more detail. White dots in the lower-left corners indicate momentum resolution. Data with ω < 55 meV (ω > 55 meV) were collected with Ei = 70 meV (Ei = 200 meV). b Corresponding constant-ω cuts across qAF, averaged over {100} and {010} trajectories. The apparent susceptibility magnitude is slightly lower than the actual values due to the averaging over the binning range q⊥ = [0.45, 0.55] r.l.u. c Magnetic dispersion extracted from 2D Gaussian fits (see text), as a function of energy transfer (ω) and incommensurability (δ = |q − qAF | ) at T = 5 K (left) and 70 K (right). The white dotted lines indicate the full-width-half-maximum of the response as a function of energy. White tick marks: ω values in (a, b). See Supplementary Information for data analysis details and additional data.

Figure 3a, b show, respectively, the energy dependence of the amplitude \({\chi }_{0}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\left(\omega \right)\) and the change \({\varDelta \chi }_{0}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\left(\omega \right)\) across Tc and between 5 K and 410 K. Figure 3c, d show the corresponding results for the momentum-integrated local susceptibility, defined as \({\chi }_{\text{loc}}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\left(\omega \right)={\int }_{}{\chi }^{{\prime} {\prime} }\left({\bf{q}},\omega \right){d}^{2}q/{\int d}^{2}q\), and its change \({\Delta}{\chi }_{\text{loc}}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\left(\omega \right).\,\) There is no notable difference between the response at 5 K and 70 K, except for a subtle low-temperature enhancement at ω ~ 30 meV, where \({\chi }_{0}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\left(\omega \right)\) is largest. We notice a spike at ~30 meV in \({\chi }_{\text{loc}}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\left(\omega \right)\) in the 5 K and 70 K data, and broad maxima at ~30 meV and ~50 meV in the 410 K data. Such enhancements were previously observed and ascribed to additional phonon scattering that is not properly removed in the processed data (see Supplementary Information)28. The results in Figs. 2 and 3 reveal that the magnetic response is gapped already in the normal state, with no significant change across Tc. At 5 K and 70 K, \({\chi }_{0}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\left(\omega \right)\) and \({\chi }_{\text{loc}}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\left(\omega \right)\,\) are peaked at ~35 meV and ~50 meV, respectively. Above ω ~ 100 meV, the response is relatively weak and rather similar at all three temperatures.

a Magnetic susceptibility amplitude \(\chi^{\prime\prime}_0\), determined from 2D fits to background-subtracted data such as those in Fig. 2a. Filled circles: Ei = 70 meV. Open circles: Ei = 200 meV. b Difference between \(\chi^{\prime\prime}_0\) at 5 K, deep in the superconducting state, and at 70 K (black) and 410 K (yellow). c Local (momentum-integrated) susceptibility \({\chi}^{\prime\prime}_{\mathrm{loc}}\) (same colors and symbols as in (a)). d Difference in \({\chi}^{\prime\prime}_{\mathrm{loc}}\), using the same colors and symbols as (c). Black vertical bars in all panels: energies where DFT indicates phonon modes at qAF. At 410 K, the local maxima in \({\chi}^{\prime\prime}_0\) and \({\chi}^{\prime\prime}_{\mathrm{loc}}\) at ~30 and ~50 meV correspond to phonon crossings and indicate the inability of our analysis to completely remove unwanted phonon contributions and/or to discern an enhanced magnetic response due to nontrivial electron-lattice coupling effects at these energies. The small enhancement in \(\chi^{\prime\prime}_0\) near 30 meV across Tc = 55 K is consistent with the existence of a small magnetic resonance, but also coincides with phonon crossings, and hence may be an electron-lattice-coupling effect or spurious. Solid lines: guides to the eye.

In order to obtain data with even better energy resolution and signal-to-noise ratios in the energy range in which the response is commensurate, we carried out measurements with Ei = 50 meV. Figure 4a shows \({\chi }_{0}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\left(\omega \right)\) below 45 meV at seven temperatures in the 10 K to 450 K range. We find again that the magnetic response extrapolates to zero at ΔAF ≈ 6 meV, both in the normal state and deep in the SC state. As already seen in Fig. 3a for 5 K and 70 K, \({\chi }_{0}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\left(\omega \right)\) exhibits a smooth, non-monotonic energy dependence at all temperatures. The Ei = 50 meV results are consistent with those obtained with higher incident energies (see Fig. 4a inset) within about 15%. Figure 4c shows the same data as a function of temperature. At high-energy transfers, \({\chi }_{0}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\) smoothly increases with decreasing temperature and begins to plateau near Tc. For ω \(\le\) 12 meV, \({\chi }_{0}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\,\) eventually decreases at low temperatures, consistent with the opening of a gap.

a Energy dependence of \(\chi^{\prime\prime}_0\) measured with Ei = 50 meV at seven temperatures. Solid lines: guides to the eye. Inset: \(\chi^{\prime\prime}_0\) obtained with Ei = 70 meV at 5 and 70 K (same data as in Fig. 3a). Black vertical bars: energies where DFT indicates phonon crossings at qAF. b Comparison of energy dependence of \(\chi^{\prime\prime}_0\) (at T = 10 K and 72 K; solid lines same as in (a)) with spin-polarized triple-axis neutron scattering results in the spin-flip channel at similar temperatures (squares: data obtained at 5 K and 70 K from momentum scans at select energies; circles: data obtained at 5 K from energy scans at qAF and two background momentum transfers; see also Figs. S6 and S7 in Supplementary Information). The triple-axis data are scaled to match the time-of-flight result, which is obtained in absolute units. The combined data demonstrate the predominant magnetic nature of the signal, peaked at ~ 35 meV, and are fully consistent with the results in Fig. 3. c Temperature dependence of \(\chi^{\prime\prime}_0\) at select energies integrated over ± 1.5 meV obtained with Ei = 50 meV. Solid lines: guides to the eye. Vertical blue lines: Tc = 55 K and T* ~ 370 K (see Fig. 1).

Figure 4b shows the energy dependence of the response at qAF obtained from triple-axis momentum and energy scans with longitudinal polarization analysis, obtained at 5 K and 70 K. These data agree well with the time-of-flight result and hence confirm the predominant magnetic nature of the scattering and the presence of a gap.

The AF correlation length can be determined from the width of the response in reciprocal space. We define the correlation length as \(\xi \,=\,1/2\kappa\), i.e., the reciprocal of the intrinsic FWHM of the response, after correcting for the instrument resolution. In the low-energy range above the AF gap, the length ranges from \(\xi \,\approx \,8.8\,\,{\text{\AA }}\) at low temperature to \(\xi \approx 6.4\,{\text{\AA}}\) at high temperature, based on the \({E}_{i}=50\,{\rm{meV}}\) data (Fig. 4). An estimate of the instantaneous length \({\xi }_{0}\,\) can be determined from an energy integration of the response. Using the Ei = 70 meV and 200 meV data (Figs. 2 and 3), and integrating over the range from 1.5 to 137.5 meV, this length ranges from \({\xi }_{0}=\,8.3\,\pm \,0.1{\text{\AA }}\) at 5 K to \({\xi }_{0}=\,6.6\,\pm \,0.1{\text{\AA}}\) at 410 K. These lengths of about 2 lattice constants are consistent prior results for other cuprates12,13,14,15 and comparable to the ~2 nm superconducting coherence length34.

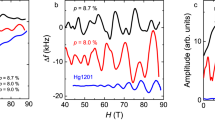

We have tested the possibility of quasi-elastic magnetic scattering, which is seen in other cuprates. Figure 5a shows triple-axis [0 1 0] momentum scans across qAF at nominally zero energy transfer (1.2 meV FWHM energy resolution). The SC (5 K) and normal (80 K) state data are featureless and statistically indistinguishable. Importantly, unlike for YBCO and LSCO11,12,13, where strong incommensurate quasi-elastic SDW peaks have been observed at similar doping levels, we observe no such scattering in Hg1201-UD55, consistent with our observation of a gapped response centered at qAF. Using the known cross-section of the (0 0 4) Bragg peak (which is 4.2 barn) for comparison, we estimate the upper bound of a possible elastic AF signal to be 0.4 mbarn.

a Triple-axis momentum scan, across qAF along [0 1 0], at ω = 0 at 5 K (black squares) and 80 K (red circles). Blue crosses: locations where SDW/stripe order is observed at a similar doping level in LSCO (p = 0.06)11. Inset: schematic of the momentum-scan range (blue arrow) and characteristic wave vectors for LSCO (p = 0.06, blue crosses). See Supplementary Information for more details. b Spin-polarized neutron scattering results for the magnetic scattering intensity at the (1 0 0) reflection, determined from the inverse flipping ratio; see Fig. S8 in the Supplementary Information for the full inverse flipping ratio data. The highly underdoped (Hg1201-UD55, blue circles) and optimally doped (Hg1201-OP95, red triangles; data from ref. 37) samples show no detectable static magnetic order, in contrast to the moderately underdoped sample (Hg1201-UD71, yellow squares; data from ref. 37). All data were obtained with the D7 spectrometer at ILL. The gray band corresponds to the 1.7 mbarn upper bound for the magnetic intensity of Hg1201-UD55 (see main text).

Finally, we also investigated the existence of a quasistatic q = 0 magnetic response, which was previously observed in both YBCO30,31,32 and Hg120135,36,37 at higher doping. While this observation was challenged in a subsequent study of YBCO38, it was shown that the samples used in this work were too small to yield meaningful insight31. Figure 5b shows the results of polarized neutron diffraction measurements of the magnetic scattering at the (1 0 0) Bragg peak in Hg1201-UD55 compared to earlier results37 for Hg1201-UD71 (moderately underdoped) and Hg1201-OP95 (optimally doped). All data were obtained with the D7 spectrometer at ILL. For Hg1201-UD71, the magnetic scattering (extracted from XYZ longitudinal polarization analysis—see the Supplementary Information) exhibits an order-parameter-like temperature dependence with an onset below T0 \(\sim \,370\) K and a maximum intensity of \(\sim \,13\) mbarn at 80 K. Conversely, the highly underdoped and optimally doped samples show no such signature of q = 0 magnetism within the detection limit of the instrument. However, we note that a nonzero q = 0 magnetic response at both the (1 0 0) and (1 0 1) reflections with a magnitude of \(\sim \,1.7\) mbarn at 100 K was previously observed for Hg1201-OP95 using a triple-axis neutron spectrometer (4F1 at LLB)37. Due to the thermal drift of the intensities collected in the different measurement channels (see Supplementary Information and ref. 37) and the inability to determine an accurate baseline for the magnetic scattering, the weak q = 0 signal falls below the threshold of detection on D7. One can thus give an upper bound of 1.7 mbarn for the q = 0 magnetism in Hg1201-UD55, as indicated by the shaded area in Fig. 5b. Interestingly, the vanishing of the q = 0 magnetic signal at low doping in Hg1201 is consistent with the significant decrease observed in underdoped YBa2Cu3O6.45 (p = 0.08)39. We note that the present data do not rule out the possibility of significant dynamic q = 0 correlations.

Discussion

At the low doping levels of the present study, the cuprates YBCO, LSCO, and Bi2201 exhibit an ungapped, hourglass-shaped magnetic response in both the normal and SC states11,13,15,40,41. In contrast, our results for Hg1201-UD55 resemble the wineglass-shaped response previously observed for Hg1201-UD71, albeit with a considerably smaller gap (~6 meV vs. ~27 meV). These findings are crucial for two reasons. First, given that the CDW order in Hg1201 is nearly absent at the doping level of the present study29, the prior result for Hg1201-UD71 does not appear to be affected by CDW correlations.

Second, the gapped, wineglass-shaped response must be the intrinsic behavior of the pristine, quintessential CuO2 planes. Unlike other hole-doped cuprates that have been investigated in this context, Hg1201 exhibits high tetragonal symmetry and minimal disorder effects, as evident from transport measurements, e.g., the observations of Kohler scaling, negligible residual resistivity, and quantum oscillations in the underdoped part of the phase diagram17,18,19,20. Incommensurate SDW and stripe correlations at low and intermediate hole concentrations5,15,40, therefore, are not universal features of the cuprates, but rather the result of material-specific interactions. While the high-energy PG energy scale of the cuprates is ~400 meV at the doping level of the present study16,42,43, the SC gap is expected to be well below the characteristic scale ωc ≈ 55 meV above which the response of Hg1201-UD55 becomes incommensurate44. The present results, which extend to ω ~ 140 meV, thus cover an important energy range and provide pivotal information for tests of SC pairing scenarios, such as spin-fluctuation-driven mechanisms6.

At somewhat higher doping levels than in the present work, Hg1201 and several other cuprates exhibit a resonance-like enhancement at qAF (and characteristic energy ωr) in the SC state, with a response that is gapped and hourglass- rather than wineglass-shaped (Fig. 1). This can be understood within an itinerant picture, in which the resonance is part of a spin exciton, i.e., a dispersive spin-triplet collective mode bound below the threshold of the Stoner continuum27. Unlike for Hg1201-UD88, which exhibits a resonance at ωr ≈ 59 meV27, no resonance was observed in Hg1201-UD7128. In the present work, we find an increase in the magnetic response in the 25–35 meV range in the SC state, yet it is unclear if this small, gradual increase is to be thought of as a resonance. From the data in Figs. 3 and 4, we estimate this spectral weight enhancement to be \({{W}}_{{r}}{=}\int {\text{d}}{\omega }\,{\varDelta }{\mbox{''}}{=}{0}{.}{14}{\pm }{0}{.}{07}\,{{\mu }}_{{\text{B}}}^{{2}}{{\text{f.u.}}}^{{-}{1}}\). Additional evidence for a small resonance-like effect from triple-axis scattering data is shown in Fig. S9 in the Supplementary Information. Although the value of the SC gap at the doping level of Hg1201-UD55 is unknown, it is likely not much larger than ωr ≈ 30 meV44, so that Wr is indeed expected to be small27. Moreover, the ratio ωr/Tc ~ 6.4 is comparable to that for other cuprates45. We caution, though, that several phonon modes cross qAF at about 30 meV, as shown in detail in Fig. 6 and also discussed in refs. 27,28, which complicates the interpretation of subtle changes in the magnetic response across Tc.

a Scattering intensity without background subtraction as a function of energy and momentum transfer along [1 1 0], integrated over q⊥ = ± 0.05 (r.l.u.) along [1 -1 0] and over a wide range in L (see Supplementary Information for details). The time-of-flight neutron data were collected at T = 10 K with Ei = 50 meV. Selected calculated phonon modes are overlaid. Red dashed lines indicate spurious scattering from Aluminum in the sample holder. b Calculated phonon intensities in the same momentum range as the data in (a), with all phonon modes below 45 meV overlayed. c–f Select phonon eigenvectors at Q = (0.5 0.5 L), with energies indicated in (a, b).

Our polarized triple-axis neutron scattering data extend up to about 40 meV and confirm that the low-energy commensurate response is predominantly magnetic in nature (Fig. 4b). However, in the time-of-flight data, both the peak and local susceptibilities at 410 K exhibit local maxima at energies (about 30 meV and 50 meV) that correspond to phonon crossings (Fig. 6), and at low temperatures, \({\chi }_{0}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\) is strongest at ~35 meV (Fig. 2–4). This points to the possibility of nontrivial electron-lattice coupling effects. A recent neutron scattering study of LSCO revealed an enhancement of χ′′(ω) in the 16–19 meV range, where the (incommensurate) spin excitations are intersected by optic phonons33. It was found that this enhancement is present only in SC samples and that, similar to the transition temperature, its magnitude follows a dome-shaped doping dependence. This effect was interpreted as an interplay among spin, charge, and lattice degrees of freedom, with resultant composite excitations: optic phonons stabilize fluctuating, short-range stripe correlations, and thereby enhance the magnetic correlations. Although Hg1201 does not display a tendency toward stripe order, similar electron-lattice coupling effects may be present. Since we lack data for non-SC samples for comparison, we are unable to carry out the same analysis as ref. 33. Instead, we performed a DFT calculation of the phonon spectrum of stoichiometric, undoped Hg1201. The observed good agreement between experiment and theory (Fig. 6) allows us to identify the approximate energy ranges that are unaffected by phonon crossings at qAF. For example, only the ω = 30 meV data in Fig. 2a, b are affected, due to the relatively strong dispersion and Q-dependence of a phonon mode crossing qAF at this energy; this contribution is not fully removed in our data analysis. Similarly, most of the energy transfers for which data are shown in Fig. 4b do not coincide with calculated phonon crossings. From this, we can conclude that, indeed, lattice effects play an overall minor role.

Comparing the present results with those for Hg1201-UD71 and Hg1201-UD88, we find that the low-temperature maximum of the local susceptibility, \({\chi }_{\text{loc}}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\left(\omega \right)\) ~ 4–5 \(\mu\)B2 eV−1f.u.−1, is approximately independent of doping. Similarly, the strength of the total, energy-integrated response (up to 100 meV) is comparable in Hg1201-UD55 and Hg1201-UD7128, and about 0.25–0.3 \({\mu}_{\mathrm{B}}^{2} {\mathrm{f}}.{\rm{u}}.^{-1}\); extrapolating the available data for Hg1201-UD8827 to 100 meV yields 0.15–0.2 \({\mu}_{\mathrm{B}}^{2} {\mathrm{f}}.{\rm{u}}.^{-1}\). Despite the differences in the structure of the response (wineglass vs. hourglass), this compares rather well with the corresponding strength of the magnetic response of underdoped LSCO (~0.15 \({\mu}_{\mathrm{B}}^{2} {\mathrm{f}}.{\rm{u}}.^{-1}\) for p = 0.085)46.

Similar to Hg1201-UD7128, Hg1201-UD8827, and underdoped YBCO47,48,49, the AF response in Hg1201-UD55 starts to increase below the PG temperature (Figs. 1 and 4c). This observation can be understood within the framework of a recent phenomenological model for the cuprates42,43, which combines insights from transport measurements with evidence that these complex oxides are inherently inhomogeneous and exhibit local two-component electronic behavior: Mott-localization of one hole per Cu occurs gradually with decreasing doping and/or temperature, in a highly inhomogeneous manner, such that below T* (or, more precisely, the somewhat lower temperature T**), the carrier density has fully crossed over from 1 + p to the nominal value p. In this picture of the phase diagram, the formation of local magnetic moments, loop currents, CDW, SDW and stripe order are all emergent phenomena, and significant (dynamic) AF correlations are expected to develop below T*. While this comprehensive model is phenomenological in nature, the present results pave the way for a microscopic theoretical understanding of the magnetic degrees of freedom of the doped CuO2 planes near the Mott-insulating parent state.

Methods

Neutron scattering experiments

The neutron scattering measurements were performed on a large co-aligned sample (mass of ~2 g) that consists of approximately 30 single crystals. Neutron diffraction on the full sample shows a FWHM mosaic of 1.7°. Crystals were grown by a flux method50 and then annealed to the desired doping level at an elevated temperature in vacuum17. For each crystal, Tc was determined from a magnetic susceptibility measurement using a Quantum Design, Inc. Magnetic Property Measurement System. The average of these measurements was used to characterize the full sample, resulting in a mean value of Tc = 55 K and a FWHM transition width of ∆Tc = 8 K.

The measurements of the AF response were carried out on the time-of-flight spectrometer ARCS at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), Oak Ridge (USA), and on two triple-axis spectrometers: IN20 at the Institute Laue-Langevin (ILL), Grenoble (France), and 2 T at the Laboratoire Léon Brillouin (LLB), Saclay (France). The magnetic dispersion was measured on ARCS, with the sample’s crystalline c-axis aligned along the incident beam, and with three incident neutron energies: Ei = 70 and 200 meV (at 5, 70, and 410 K) and Ei = 50 meV (at 10, 46, 72, 150, 250, 350, and 450 K). As in previous work on Hg120127,28, the sample was only measured in one orientation, and the data were integrated along [0 0 1] due to the quasi-2D nature of the magnetic response in the lamellar cuprates. One side effect of this is that for any value of in-plane momentum transfer q = (H K), data with different energy transfer ω correspond to different values of out-of-plane momentum transfer L, as constrained by momentum and energy conservation. The dynamic magnetic susceptibility \(\chi ^{{\prime} {\prime}} \left({\bf{Q}},\omega \right)\) was determined from the scattering cross-section by correcting for the anisotropic magnetic form factor51,52 and the thermal Bose factor of the excitations, as described in previous work27,28 and detailed in the Supplementary Information. Longitudinal polarization analysis was performed on IN20 to extract the purely magnetic signal. Momentum scans across qAF at select energies ranging from 9 to 30 meV, and energy scans at qAF and two background momentum transfers were performed. The detailed temperature dependence of \(\chi ^{{\prime} {\prime}} \left({\bf{Q}},\omega \right)\) at \(\omega\) = 30 meV (Fig. S9) and the elastic scattering (Fig. 5a) were measured on 2 T.

The q = 0 magnetism measurements were carried out on the D7 diffractometer at ILL, equipped with a cryofurnace, and with an incident neutron wavelength of 3.1 Å. The sample was aligned in the (H 0 L) scattering plane. The temperature dependence of the scattering at (1 0 0) was tracked between 80 K (above the SC transition to avoid the neutron beam depolarization) and 455 K using XYZ longitudinal polarization analysis to search for a possible magnetic signal coincident with the nuclear (1 0 0) Bragg reflection, as detailed in the Supplementary Information.

Density-functional theory calculations

Phonon dispersions and eigenvectors were calculated using the density-functional perturbation theory implementation in the abinit package53. Exchange-correlation was approximated with the PBEsol54 version of the generalized-gradient approximation, and norm-conserving pseudopotentials were used for the valence-core interaction55. The energy cutoff was 1200 eV, and the k-point grid for ground state and perturbation calculations was 12 × 12 × 6. Dynamical matrices were calculated on a uniform 4 x 4 x 2 q-point grid, corresponding to a 4 × 4 ×2 supercell in real space. The real-space force constants were ported to phonopy56 format using abipy57 and then used in the euphonic package58 to calculate neutron intensities.

Data availability

The data obtained on IN20 at ILL are available at https://doi.org/10.5291/ILL-DATA.4-01-1354. The data obtained on D7 at ILL are available at https://doi.org/10.5291/ILL-DATA.5-41-943. The data obtained on ARCS at ORNL are stored by ORNL and available from the corresponding authors upon request; they were collected in experiments IPTS-8474.1 and IPTS-16717.1.

References

Uchida, S. et al. Optical spectra of La2-xSrxCuO4: effect of carrier doping on the electronic structure of the CuO2 plane. Phys. Rev. B. 43, 7942 (1991).

Vaknin, D. et al. Antiferromagnetism in La2CuO4-y. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 2802 (1987).

Shirane, G. et al. Two-dimensional antiferromagnetic quantum spin-fluid state in La2CuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 1613 (1987).

Bourges, P., Casalta, H., Ivanov, A. S. & Petitgrand, D. Superexchange coupling and spin susceptibility spectral weight in undoped monolayer cuprates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 4906 (1997).

Keimer, B., Kivelson, S. A., Norman, M. R., Uchida, S. & Zaanen, J. From quantum matter to high-temperature superconductivity in copper oxides. Nature 518, 179 (2015).

Scalapino, D. J. A common thread: the pairing interaction for unconventional superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 1383 (2012).

O’Mahony, S. M. et al. On the electron pairing mechanism of copper-oxide high-temperature superconductivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2207449119 (2022).

Wang, Y. & Chubukov, A. Charge-density-wave order with momentum (2Q,0) and (0,2Q) within the spin-fermion model: continuous and discrete symmetry breaking, preemptive componsite order, and relation to pseudogap in hole-doped cuprates. Phys. Rev. B. 90, 035149 (2014).

Allais, A., Bauer, J. & Sachdev, S. Density wave instabilities in a correlated two-dimensional metal. Phys. Rev. B. 90, 155114 (2014).

Atkinson, W. A., Kampf, A. P. & Bulut, S. Charge order in the pseudogap phase of cuprate superconductors. New J. Phys. 17, 130225 (2015).

Birgeneau, R. J., Stock, C., Tranquada, J. M. & Yamada, K. Magnetic neutron scattering in hole-doped cuprate superconductors. J. Phys. Soc. Japan 75, 111003 (2006).

Sidis, Y. et al. Inelastic neutron scattering study of spin excitations in the superconducting state of high temperature superconductors. C. R. Phys. 8, 745 (2007).

Fujita, M. et al. Progress in neutron scattering studies of spin excitations in high-Tc cuprates. J. Phys. Soc. Japan 81, 011007 (2012).

Bourges, P. et al. Spin dynamics in the metallic state of the high-Tc superconducting system YBa2Cu3O6+x. Phys. B Cond. Matt. 215, 30 (1995).

Haug, D. et al. Neutron scattering study of the magnetic phase diagram of underdoped YBa2Cu3O6+x. New J. Phys. 12, 105006 (2010).

Honma, T. & Hor. P. H. Unified electronic phase diagram for hole-doped high-Tc cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 77, 184520 (2008).

Barišić, N. et al. Demonstrating the model nature of the high-temperature superconductor HgBa2CuO4+δ. Phys. Rev. B. 78, 054518 (2008).

Barišić, N. et al. Universal quantum oscillations in the undersdoped cuprate superconductors. Nat. Phys. 9, 761 (2013).

Barišić, N. et al. Universal sheet resistance and revised phase diagram of the cuprate high-temperature superconductors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 12235 (2013).

Chan, M. et al. In-plane magnetoresistance obeys Kohler’s rule in the pseudogap phase of cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 177005 (2014).

Eisaki, H. et al. Effect of chemical inhomogeneity in bismuth-based copper oxide superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 69, 064512 (2004).

Barišić, N. et al. Evidence for a universal Fermi-liquid scattering rate throughout the phase diagram of the copper-oxide superconductors. New J. Phys. 21, 113007 (2019).

Chan, M. K. et al. Extent of Fermi-surface reconstruction in the high-temperature superconductor HgBa2CuO4+δ. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9782 (2020).

Li, Y., Tabis, W., Yu, G., Barišić, N. & Greven, M. Hidden Fermi-liquid charge transport in the antiferromagnetic phase of the electron-doped cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 197001 (2016).

Rullier-Albenque, F., Alloul, H., Balakirev, F. & Proust, C. Disorder, metal-insulator crossover and phase diagram in high-Tc cuprates. Euro. Phys. Lett. 81, 37008 (2008).

Suchaneck, A. et al. Incommensurate magnetic order and dynamics induced by spinless impurities in YBa2Cu3O6.6. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 037207 (2010).

Chan, M. et al. Hourglass dispersion and resonance of magnetic excitations in the superconducting state of the single-layer cuprate HgBa2CuO4+δ near optimal doping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 277002 (2016).

Chan, M. K. et al. Commensurate antiferromagnetic excitations as a signature of the pseudogap in the tetragonal high-Tc cuprate HgBa2CuO4+δ. Nat. Commun. 7, 10819 (2016).

Tabis, W. et al. Synchrotron x-ray scattering study of charge-density-wave order in HgBa2CuO4+δ. Phys. Rev. B. 96, 134510 (2017).

Fauqué, B. et al. Magnetic order in the pseudogap phase of high-Tc superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 197001 (2006).

Bourges, P., Sidis, Y. & Mangin-Thro, L. Comment on “No evidence for orbital loop currents in charge-ordered YBa2Cu3O6+x from polarized neutron diffraction”. Phys Rev. B. 98, 016501 (2018).

Bourges, P., Bounoua, D. & Sidis, Y. Loop currents in quantum matter. C. R. Phys. 22, 7 (2021).

Ikeuchi, K. et al. Spin exciitations coulped with lattice and charge dynamics in La2-xSrxCuO4. Phys. Rev. B. 105, 014508 (2022).

Wesche, R. in Physical Properties of High-temperature Superconductors. 165–202 (John Wiley & Sons, 2015).

Li, Y. et al. Unusual magnetic order in the pseudogap region of the superconductor HgBa2CuO4+δ. Nature 455, 372 (2008).

Li, Y. et al. Magnetic order in the pseudogap phase of HgBa2CuO4+δ studied by spin-polarized neutron diffraction. Phys. Rev. B. 84, 224508 (2011).

Tang, Y. et al. Orientation of the intra-unit-cell magnetic moment in the high-Tc superconductor HgBa2CuO4+δ. Phys. Rev. B. 98, 214418 (2018).

Croft, T. P. et al. No evidence for orbital loop currents in charge-ordered YBa2Cu3O6+x from polarized neutron diffraction. Phys. Rev. B. 96, 214504 (2017).

Balédent, V. et al. Evidence for competing magnetic instabilities in underdoped YBa2Cu3O6+x. Phys. Rev. B. 83, 104504 (2011).

Tranquada, J. M. in Handbook of High-Temperature Superconductivity. 257–298 (Springer, New York, 2007).

Xu, G. et al. Testing the itinerancy of spin dynamics in superconducting Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Nat. Phys. 5, 642 (2009).

Pelc, D., Popčević, P., Požek, M., Greven, M. & Barišić, N. Unusual behavior of cuprates explained by heterogeneous charge localization. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau4538 (2019).

Pelc, D. et al. Resistivity phase diagram of cuprates revisited. Phys. Rev. B. 102, 075114 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Doping-dependent photon scattering resonance in the model high-temperature superconductor HgBa2CuO4+δ revealed by Raman scattering and optical ellipsometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 187001 (2013).

Yu, G., Li, Y., Motoyama, E. M. & Greven, M. A universal relationship between magnetic resonance and superconducting gap in unconventional superconductors. Nat. Phys. 5, 873 (2009).

Lipscombe, O. J., Vignolle, B., Perring, T. G., Frost, C. D. & Hayden, S. M. Emergence of coherent magnetic excitations in the high temperature underdoped La2-xSrxCuO4 superconductor at low temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 167002 (2009).

Fong, H. F. et al. Spin susceptibility in underdoped YBa2Cu3O6+x. Phys. Rev. B. 61, 14773 (2000).

Dai, P. et al. The magnetic excitation spectrum and thermodynamics of high-Tc superconductors. Science 284, 1344 (1999).

Hinkov, V. et al. Spin dynamics in the pseudogap state of a high-temperature superconductor. Nat. Phys. 3, 780 (2007).

Zhao, X. et al. Crystal growth and characterization of the model high-temperature superconductor HgBa2CuO4+δ. Adv. Mater. 18, 3243 (2006).

Brown, P. J. in Neutron Data Booklet (eds Dianoux, A.-J. & Lander, G.) 60–71 (Old City Publishing, Philidelphia, 2003).

Shamoto, S., Sato, M., Tranquada, J. M., Sternlieb, B. J. & Shirane, G. Neutron-scattering study of antiferromagnetism in YBa2Cu3O6.15. Phys. Rev. B. 48, 13817 (1993).

Gonze, X. et al. The ABINIT project: Impact, environment and recent developments. Comp. Phys. Comm. 248, 107042 (2020).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136406 (2008).

van Setten, M. J. et al. The PseudoDojo: training and grading a 85 element optimized norm-conserving pseudopotential table. Comp. Phys. Comm. 226, 39 (2018).

Togo, A. First-principles phonon calculations with Phonopy and Phono3py. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 92, 012001 (2023).

abinit/abipy: Open-source library for analyzing the results produced by ABINIT, available at https://github.com/abinit/abipy.

Rebecca, F. et al. Euphonic: inelastic neutron scattering simulations from force constants and visualization tools for phonon properties. J. App. Cryst. 55, 1689 (2022).

Murayama, H. et al. Diagonal nematicity in hte pseudogap phase of HgBa2CuO4+δ. Nat. Commun. 10, 3282 (2019).

Liang, R., Bonn, D. A. & Hardy, W. N. Evaluation of CuO2 plane hole doping in YBa2Cu3O6+x single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 73, 180505 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The work at the University of Minnesota was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy through the University of Minnesota Center for Quantum Materials, under Grant No. DE-SC0016371. A portion of this research used resources at the Spallation Neutron Source, a Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated by Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Beam time was allocated to ARCS on proposals IPTS-8474 and IPTS-16717. Part of this research used resources at the Institute Laue-Langevin, via beam lines IN20 and D7. A portion of this research used resources at the Laboratoire Léon Brillouin, a facility funded by the French Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) and National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), via beam line 2T. T.S. and D.R. acknowledge support by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, under Contract No. DE-SC0024117.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G. conceived the research. Z.W.A., Y.T., V.N., M.K.C., C.J.D. and G.Y. performed crystal growth, characterization, and co-alignment. Z.W.A., Y.T., M.K.C. and L.M.-T. performed the neutron scattering experiments. D.L.A., A.D.C., P.S., D.B., Y.S. and P.B. were local contacts for the neutron scattering experiments. Z.W.A., Y.T. and M.K.C. carried out the data analysis. T.S. and D.R. performed the DFT calculation. Z.W.A. and M.G. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anderson, Z.W., Tang, Y., Nagarajan, V. et al. Gapped commensurate antiferromagnetic response in a strongly underdoped model cuprate superconductor. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 93 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00804-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00804-0