Abstract

Stacking and twisting van der Waals materials provides a powerful tool to engineer quantum matter. For instance, 1T-TaS2 monolayers are Mott insulators, whereas layered 1H-TaS2 is metallic and superconducting; thus, the T/H bilayer, where heavy fermions and unconventional superconducting phases are expected from localized spins (1T) coexisting with itinerant electrons (1H), has been intensively studied. However, recent studies revealed significant charge transfer that questions this scenario. Here, we propose a T/T/H trilayer heterostructure where the T/T bilayer is a flat-dispersion band insulator with localized electrons, whereas the 1H layer remains metallic with a weak spin polarization. Varying the T/T stacking configuration tunes the flat-band filling, enabling a crossover from a doped-Mott regime to a Kondo-like state. Such a trilayer heterostructure provides, therefore, a rich novel platform to study strong correlation phenomena and unconventional superconductivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Van der Waals (vdW) materials have recently revolutionized the study of quantum matter, providing unprecedented control over electronic correlations and emergent phases1,2,3. A prime example is twisted bilayer graphene, where flat bands amplify Coulomb interactions, yielding unconventional superconductivity and correlated insulators3,4,5,6. Inspired by such discoveries, transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) have emerged as versatile platforms for engineering quantum phases7,8. Particularly, TaX2 (X=S, Se) have been highlighted due to its distinctive properties in various polytypes. Among the polytypes of TaX2, 1T-TaX2 is a Mott insulator with \(\sqrt{13}\times \sqrt{13}\) a charge density wave (CDW) structure forming Star of David (SoD) clusters7,9,10,11. It forms a spin-1/2 triangular superlattice that is being intensively discussed as a quantum spin liquid candidate12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. In contrast, 1H-TaX2 is an Ising superconductor with a competing 3 × 3 CDW phase21,22,23,24.

Heterostructures made of the combination of these contrasting states, as it is the case of 4Hb-TaS2, which consists of alternating 1T and 1H layers, have been exploited as promising platforms for exploring emergent phenomena resulting from the coexistence of Mott insulating and superconducting phases, including unconventional superconductivity25,26,27,28 and Kondo-like behavior19,20,29,30. However, in such heterostructures, a considerable charge transfer from the 1T to the 1H layer is expected, due to, among others, the different work functions of the layers. The 1H layer takes up to one electron per SoD away from the 1T layer in 4Hb-TaS2 and in bilayer 1T/1H-TaS2, depending on the distance between layers31. This complicates the preservation of a Mott insulating half-filled spin-1/2 triangular lattice at the 1T layer, hybridizing with the itinerant electrons of the 1H layer, and leads instead to a heavily doped-Mott system31,32. These challenges have led to controversial interpretations of sample-dependent electronic properties in these platforms, as some samples seem to display Kondo-like behavior due to localized spins hybridizing with itinerant electrons29,30, while other samples do not observe localized spins as a result of the strong charge transfer that vacates the localized state of 1T SoD26,33,34.

In this work, we propose an alternative heterostructure, a trilayer T/T/H-TaS2, which promises to display a rich variety of correlated phases and yet is free from the difficulties in the T/H bilayer. While the T/T bilayer is a band insulator, where the interlayer hybridization quenches the spin degrees of freedom and disrupts the Mott bands35,36,37, nearly one electron transfer to the 1H monolayer leaves behind one electron in the T/T bilayer, restoring Mott behavior. The interlayer stacking of the T/T bilayer controls the hybridization strength and charge transfer and indicates the possibility in the trilayer of a crossover from a doped-Mott insulator (similar to the T/H bilayer case31) to a Kondo insulator. Apart from the presence of localized spins in the T/T bilayer, the 1H monolayer exhibits spin-polarized itinerant electrons and may lead to unconventional superconductivity. In addition, we note that some recent experiments demonstrate the feasibility of such trilayer heterostructures by thermal annealing38,39,40,41, and laser-induced polytype transformation42,43 in bulk 1T-TaS2.

Results

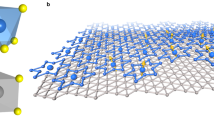

T/T bilayers and stacking order

1T-TaS2 undergoes a CDW transition to a commensurate \(\sqrt{13}\times \sqrt{13}\) superlattice around 200 K9 where twelve Ta atoms surrounding a central Ta are displaced towards the center. This results in a SoD structure that opens a gap of ~0.5 eV, which arises as the 12 Ta 5d1 electrons form a molecular orbital36,37. The remaining spins localized at the center of the SoD form a triangular lattice in the 1T-TaS2 superlattice and become Mott-localized12,44. Our calculations demonstrate a band gap of about 0.3 eV within the CDW gap, as shown in Fig. 1b. We note that we find the SoD structure to be stable in monolayer, T/T bilayers and T/T/H trilayers.

a Schematic illustration showing the transition from a Mott insulator (monolayer) to a band insulator (bilayer) driven by interlayer hybridization. The yellow arrows represent local spins at the center of the Star of David, which get quenched in the band insulator. b, c Corresponding band structures and density of states for b monolayer 1T-TaS2 and c bilayer T/T-TaS2, demonstrating the evolution from a correlation-driven gap to a hybridization gap. Majority and minority spins are denoted by solid and dashed lines, respectively. The Fermi level is set to 0 eV.

When two 1T layers are stacked, the number of electrons in the unit cell becomes even. Since the two layers are assembled with the two SoD structures facing each other, localized spins in opposite layers form a singlet state due to the interlayer hybridization. This results in a band insulator, as illustrated in Fig. 1a, c35,36 with fully filled bonding- and empty antibonding bands. As expected, the band gap of the T/T bilayer is only marginally affected by on-site repulsion U, whereas 1T monolayer, being a genuine Mott insulator (half-filled band), exhibits a clear dependence on U (as discussed in Supporting Information 2). We note that the top valence band (bonding band) is even flatter in the T/T bilayer than in the 1T monolayer, and, upon hole doping, correlation effects are expected to be significant, turning it into a (doped) Mott band.

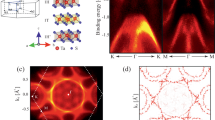

Next, we show that the T/T bilayer band structure is extremely sensitive to the interlayer stacking order. In a 1T monolayer, thirteen Ta atoms in a SoD are classified into three groups35,45: one central atom, inner hexagon atoms (six atoms), and outer corner atoms (six atoms). When two 1T layers are stacked, the Ta atoms can be categorized into three groups based on the in-plane shift between two SoD. We note the direct stacking with no shift TA, shift to the inner hexagon TB and shift to the outer corner TC, as illustrated in Fig. 2a–c. The lateral displacement reduces the inter-SoD coupling37 but enhances the in-plane hopping35,46,47. Consequently, from TA to TB and TC, the top valence and bottom conduction bands increase in bandwidth, and their energy gap decreases. The TC case even shows a zero indirect gap (see Fig. 2f). The TA stacking is the most stable in comparison to the TB and TC stackings, with relative formation energies of 83 and 159 meV per SoD pair, respectively. A previous DFT study on bulk 1T-TaS245 showed that charge doping or lattice strain can change the relative energy between TA and TC stackings. This indicates that the stacking energetics in the T/T/H trilayer may deviate from the T/T bilayer case.

a–c The top view of atomic structures for bilayer T/T-TaS2 with TA, TB, and TC stacking, respectively. Two SoD clusters by Ta atoms in each layer are depicted in blue and red stars. All S atoms are omitted for clarity. d–f Corresponding electronic band structures. All bands are doubly degenerate due to the inversion and time-reversal symmetries. From TA, to TB, and TC, the bandwidth increases due to enhanced in-plane hopping and the band gap reduces.

T/T/H trilayers

We next investigate the electronic behavior of a trilayer heterostructure formed by a T/T bilayer in proximity to a 1H monolayer. The supercell is constrained to a \(\sqrt{13}\times \sqrt{13}\) superlattice to incorporate the SoD structure. The 3 × 3 CDW in the 1H layer, which exhibits only marginal differences in charge transfer compared to 1 × 1 1H31, is neglected in these calculations. The interlayer separations in the optimal structures between the bottom 1H layer and the middle 1T layer is 5.82 Å on average, close to that of the T/H bilayer, of 5.81 Å31. And the optimal distances between the 1T layers in the T/T/H trilayer and in the T/T bilayer are nearly the same 5.85 Å on average for the three kinds of stacking orders (more details are provided in Supplementary Note 1).

The relative energetic stability between different T/T stacking indeed changes when forming the T/T/H trilayer. Compared to the bilayer case, where the TA stacking is the most stable, the TC stacking is the energetically most favorable in the trilayer, while TA and TB stackings are higher in energy by 28 and 33 meV per SoD pair, respectively. The close formation energies indicate that the three stacking orders may coexist in experiments, for example, in thermal annealing samples38.

Stacking-tuned charge transfer and electronic states

The resulting charge redistribution in the T/T/H trilayer can be rationalized by the competition between the interlayer interactions of the middle T layer with the top T layer and the bottom H layer. The electronic structures of the three trilayer heterostructures considered are shown in Fig. 3. The TC case (Fig. 3e, f) can be straightforwardly explained. Because of weak T/T layer coupling, the middle T layer loses one electron to the H layer, and therefore the top T layer keeps approximately one unpaired electron per SoD. Consequently, the top T layer recovers a flat-band Mott state, and the H layer exhibits weak spin polarization near the Fermi surface (Fig. 3f). Due to reduced hopping in the plane, the new Mott band is flatter than for the corresponding TC stacking in the T/T bilayer case. Although the middle T layer becomes nearly a band insulator, it mediates the top-bottom coupling for the coexistence of localized spins in Mott bands and itinerant electrons in metallic bands, suggesting a possibility of heavy-fermion behavior.

a Top view (upper panel) and side view (lower panel) of spin density for the TA stacking. Blue and orange regions indicate opposite spin orientations. SoD clusters in the top and middle 1T layers are outlined in blue and red lines, and the triangular lattice in the 1H layer is shown in gray lines. The central Ta atom is highlighted in yellow. b Band structure and layer-resolved density of states for the TA trilayer. Majority and minority spin states on two 1T layers are depicted in blue and orange lines, while spin states in the 1H layer are represented by dark and dim gray lines. c, d Corresponding plots for the TB, and e, f for the TC stacking.

The TA stacking case (Fig. 3a, b) exhibits slightly smaller electron transfer of 0.8 electron to the H layer than the TC stacking because of the stronger T/T hybridization in TA (details of charge transfer estimation are provided in Supporting Information 4). The original T/T bilayer valence band is slightly more than half filled, that is, the lower Hubbard band is fully occupied while the upper one is marginally occupied as shown in Fig. 3b. Despite the two T layers exhibiting similar density of states, the spin density in Fig. 3a indicates that the middle T layer has a lower spin density than the top T layer due to the proximity of the H layer. The TA trilayer results therefore into an electron-doped-Mott insulator, similar to the case of T/H bilayer which is a hole-doped-Mott insulator31. The TB stacking case shows a band structure and spin density intermediate to the TA and TC cases, as expected from the intermediate T/T coupling.

Generally, it is believed that the hybridization strength and charge transfer correlate with interlayer distance and work function difference31,48. However, the trilayers demonstrate different charge transfers despite nearly identical interlayer distances and work functions in TA, TB, and TC (see Supplementary Note 3). We can rationalize this from the chemical hardness perspective. The chemical hardness stipulates that the resistance to electron transfer in a system is proportional to the band gap49. Because of decreasing energy gaps, TA, TB, and TC stackings exhibit increasing charge transfer (also confirmed by the real-space charge density analyses in Supplementary Note 4) from the T/T bilayer to the 1H layer upon the formation of the T/T/H heterostructures.

Additionally, to test the robustness of the charge transfer regarding the layer stacking, we first introduced a lateral shift at the T/H interface, which corresponds to the case in 6R-phase TaS2, and found that the charge redistribution remains largely unaffected (Supplementary Note 7). We also investigated the influence of a graphene substrate (graphene/T/T/H-TaS2 four-layer heterostructure) and observed a considerable amount of electron doping from graphene to the trilayer. In the graphene/(TC)T/T/H-TaS2 system, the charge depletion drops from 1.00 e to 0.72 e in T/T bilayer, effectively refilling the upper Hubbard band and demonstrating the compensating role of graphene50 (Supplementary Note 8). Importantly, the stacking-insensitive charge transfer is qualitatively preserved across the substrate choices, although its magnitude varies.

Beyond the charge redistribution, we find that stacking-controlled charge transfer polarizes the 1H layer. Notably, the interplay between the spin-polarized 1H layer and localized spins in the 1T layers gives rise to distinct magnetic coupling patterns. Different from the TC stacking with parallel coupling between the top 1T and bottom 1H layers, TA and TB-stacked T/T bilayer induces opposite spin densities on the H layer compared to the spin polarization in the T layers, indicating antiferromagnetic interlayer coupling (see Fig. 3a, c, e). A more detailed analysis of the stacking-dependent magnetic coupling is provided in Supplementary Note 9.

Discussion

Overall, TA, TB, and TC trilayers may provide a platform for exploring a continuous transition from a doped-Mott insulator candidate to a Kondo insulator candidate. Additionally, our discussion on correlated states is based on dynamical mean-field theory calculations that we have performed in a previous work31 by considering representative possible cases of fillings of the 1T layer and hybridization to showcase the various scenarios: the Kondo behavior when the 1T layer has one electron per Star of David (our case of TC stacking) and a heavily doped-Mott behavior (our case of TA stacking).

Having established the magnetic ground states of the pristine trilayer, we finally consider how adding further layers or dopants can tune these correlations. Bulk heterostructures composed of 1H layers and multilayer 1T layers thicker than a T/T bilayer are at least achievable through thermal processing38,39,40,41 and laser exposure42,43, and are expected to host localized spin moments, unlike 4Hb-TaS2, which has a well-defined alternative stacking order of 1H and 1T monolayers. Furthermore, if a fourth 1T layer is placed on the top of a T/T/H trilayer in a TC stacking, it might reopen the hybridization gap as the fourth and third T layers form a new band insulator bilayer. We expect a rich phase diagram for different numbers of layers and varied interlayer stacking.

One may find some similarity with the previously discussed doping in T/H-TaS2 bilayer with alkali adatoms (alkali/T/H-TaS2), rather than adding a 1T layer on top, “T”/T/H-TaS2, as demonstrated in recent studies that used alkali and alkali-earth dopants to engineer honeycomb or kagome superlattices with fractional filling51,52. While such dopants can modulate the filling factor and potentially bring the heterostructure close to half-filling via charge transfer, achieving uniform and periodic arrangements at high dopant coverage is challenging51. Local variations can disrupt lattice uniformity and give rise to disorder-induced localization, leading to a crossover from Mott to Anderson insulating behavior53. These limitations highlight the importance of a structurally clean approach to modulate Mottness in well-ordered platforms, such as the stacking-engineered T/T/H trilayers presented in this work, for exploring tunable correlated electronic phases in TaS2 heterostructures.

These trilayers provide a promising material platform to explore unconventional superconductivity with important ingredients: spin-polarized states in the normal state of a superconductor (1H layer)54, spin–orbit coupling, and tunable strongly-correlated states (T/T bilayer). For example, in the presence of superconductivity, the induced spin polarization in the 1H layer may favor p-wave Cooper pairing55,56,57,58. Thus, we call for further experimental and theoretical studies on possible exotic superconductivity in this platform.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that TaS2 trilayers combining a T/T bilayer and 1H monolayer exhibit flat bands with localized spins and itinerant states. The amount of charge transfer between the T/T bilayer and the 1H monolayer and the resulting band structures depend on the T/T stacking order. Coexisting with itinerant electrons from the H layer, the TC-type stacking results in a half-filled Mott band while the TA- and TB-type stackings induce a partially doped-Mott state. In contrast to the T/H bilayer, the 1H layer in the trilayer exhibits weak spin polarization following the charge transfer. These trilayer heterostructures facilitate a rich platform to study strong electron correlation and exotic superconductivity in vdW heterostructures.

Methods

DFT calculations

Spin-polarized density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) implementing the projector augmented wave method59. We used the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation energy functional60, and incorporated van der Waals interactions using the DFT-D3 method with the Becke–Johnson damping function61. The electronic correlations among Ta 5d electrons in 1T-TaS2 and 1H-TaS2 layers are modeled within the DFT+U implementation of ref. 62 and using \({U}_{{\rm{Ta,5d}}}^{{\rm{1T}}}=\)1.76 eV and \({U}_{{\rm{Ta,5d}}}^{{\rm{1H}}}=\)2.82 eV, respectively48. The plane wave cutoff was set to 400 eV. The first Brillouin zone is sampled by an 8 × 8 Γ-centered k-point mesh, and Gaussian smearing of 15 meV is adopted for the Brillouin zone integrals. Electronic energy convergence was set to 10−7 eV, and ionic relaxation was performed until the Hellmann-Feynman forces acting on each ion became less than 1 meV/Å. A detailed description of the ionic relaxation protocols, structural characteristics of the optimized multilayer heterostructures is provided in Supplementary Note 1. Spin–orbit coupling was not included, as its effect on charge redistribution and flat-band occupation in the trilayer system was found to be negligible (see Supplementary Note 5 for detailed comparison).

Data availability

The atomic coordinate files to replicate DFT runs are available in the Zenodo repository with the identifier https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1549890863.

References

Geim, A. K. & Grigorieva, I. V. Van der waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013).

Novoselov, K. S., Mishchenko, A., Carvalho, A. & Castro Neto, A. H. 2d materials and van der waals heterostructures. Science 353, aac9439 (2016).

Balents, L., Dean, C. R., Efetov, D. K. & Young, A. F. Superconductivity and strong correlations in moiré flat bands. Nat. Phys. 16, 725–733 (2020).

Bistritzer, R. & MacDonald, A. H. Moiré bands in twisted double-layer graphene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 12233–12237 (2011).

Cao, Y. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 43–50 (2018).

Jiang, Y. et al. Charge order and broken rotational symmetry in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 573, 91–95 (2019).

Wilson, J. A., Di Salvo, F. J. & Mahajan, S. Charge-density waves and superlattices in the metallic layered transition metal dichalcogenides. Adv. Phys. 50, 1171–1248 (2001).

Yang, H., Kim, S. W., Chhowalla, M. & Lee, Y. H. Structural and quantum-state phase transitions in van der waals layered materials. Nat. Phys. 13, 931–937 (2017).

Wang, Y. D. et al. Band insulator to mott insulator transition in 1t-tas2. Nat. Commun. 11, 4215 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Strong correlations and orbital texture in single-layer 1t-tase2. Nat. Phys. 16, 218–224 (2020).

Nakata, Y. et al. Robust charge-density wave strengthened by electron correlations in monolayer 1t-tase2 and 1t-nbse2. Nat. Commun. 12, 5873 (2021).

Law, K. T. & Lee, P. A. 1t-tas2 as a quantum spin liquid. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 6996–7000 (2017).

He, W.-Y., Xu, X. Y., Chen, G., Law, K. T. & Lee, P. A. Spinon fermi surface in a cluster mott insulator model on a triangular lattice and possible application to 1t-tas2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 046401 (2018).

Ribak, A. et al. Gapless excitations in the ground state of 1t-tas2. Phys. Rev. B 96, 195131 (2017).

Klanjšek, M. et al. A high-temperature quantum spin liquid with polaron spins. Nat. Phys. 13, 1130–1134 (2017).

Murayama, H. et al. Effect of quenched disorder on the quantum spin liquid state of the triangular-lattice antiferromagnet 1t-tas2. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013099 (2020).

Mañas-Valero, S., Huddart, B. M., Lancaster, T., Coronado, E. & Pratt, F. L. Quantum phases and spin liquid properties of 1t-tas2. npj Quantum Mater. 6, 69 (2021).

Benedičič, I. et al. Superconductivity emerging upon se doping of the quantum spin liquid 1t-tas2. Phys. Rev. B 102, 054401 (2020).

Ruan, W. et al. Evidence for quantum spin liquid behaviour in single-layer 1t-tase2 from scanning tunnelling microscopy. Nat. Phys. 17, 1154–1161 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Evidence for a spinon kondo effect in cobalt atoms on single-layer 1t-tase2. Nat. Phys. 18, 1335–1340 (2022).

Coleman, R. V., Eiserman, G. K., Hillenius, S. J., Mitchell, A. T. & Vicent, J. L. Dimensional crossover in the superconducting intercalated layer compound 2h-tas2. Phys. Rev. B 27, 125 (1983).

De la Barrera, S. C. et al. Tuning ising superconductivity with layer and spin–orbit coupling in two-dimensional transition-metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 9, 1427 (2018).

Bhoi, D. et al. Interplay of charge density wave and multiband superconductivity in 2h-pdxtase2. Sci. Rep. 6, 24068 (2016).

Lian, C.-S. et al. Coexistence of superconductivity with enhanced charge density wave order in the two-dimensional limit of tase2. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 4076–4081 (2019).

Ribak, A. et al. Chiral superconductivity in the alternate stacking compound 4hb-tas2. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax9480 (2020).

Nayak, A. K. et al. Evidence of topological boundary modes with topological nodal-point superconductivity. Nat. Phys. 17, 1413–1419 (2021).

Persky, E. et al. Magnetic memory and spontaneous vortices in a van der waals superconductor. Nature 607, 692–696 (2022).

Yan, L. et al. Modulating charge-density wave order and superconductivity from two alternative stacked monolayers in a bulk 4hb-tase2 heterostructure via pressure. Nano Lett. 23, 2121–2128 (2023).

Vaňo, V. et al. Artificial heavy fermions in a van der waals heterostructure. Nature 599, 582–586 (2021).

Ayani, C. G. et al. Probing the phase transition to a coherent 2d kondo lattice. Small 20, 2303275 (2024).

Crippa, L. et al. Heavy fermions vs doped mott physics in heterogeneous ta-dichalcogenide bilayers. Nat. Commun. 15, 1357 (2024).

Almoalem, A. et al. Charge transfer and spin-valley locking in 4hb-tas2. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 36 (2024).

Wen, C. et al. Roles of the narrow electronic band near the fermi level in 1t-tas2-related layered materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 256402 (2021).

Kumar Nayak, A. et al. First-order quantum phase transition in the hybrid metal–mott insulator transition metal dichalcogenide 4hb-tas2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2304274120 (2023).

Ritschel, T., Berger, H. & Geck, J. Stacking-driven gap formation in layered 1t-tas2. Phys. Rev. B 98, 195134 (2018).

Darancet, P., Millis, A. J. & Marianetti, C. A. Three-dimensional metallic and two-dimensional insulating behavior in octahedral tantalum dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 90, 045134 (2014).

Butler, C. J., Yoshida, M., Hanaguri, T. & Iwasa, Y. Mottness versus unit-cell doubling as the driver of the insulating state in 1t-tas2. Nat. Commun. 11, 2477 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Surface-limited superconducting phase transition on 1t-tas2. ACS Nano 12, 12619–12628 (2018).

Sung, S. H. et al. Two-dimensional charge order stabilized in clean polytype heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 13, 413 (2022).

Sung, S. H. et al. Endotaxial stabilization of 2d charge density waves with long-range order. Nat. Commun. 15, 1403 (2024).

Husremović, S. et al. Encoding multistate charge order and chirality in endotaxial heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 14, 6031 (2023).

Ravnik, J. et al. Strain-induced metastable topological networks in laser-fabricated tas2 polytype heterostructures for nanoscale devices. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 3743–3751 (2019).

Ravnik, J. et al. Quantum billiards with correlated electrons confined in triangular transition metal dichalcogenide monolayer nanostructures. Nat. Commun. 12, 3793 (2021).

Fazekas, P. & Tosatti, E. Electrical, structural and magnetic properties of pure and doped 1t-tas2. Philos. Mag. B 39, 229–244 (1979).

Lee, S.-H., Goh, J. S. & Cho, D. Origin of the insulating phase and first-order metal-insulator transition in 1t-tas2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 106404 (2019).

Ritschel, T. et al. Orbital textures and charge density waves in transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Phys. 11, 328–331 (2015).

Pizarro, J. M. et al. Deconfinement of mott localized electrons into topological and spin–orbit-coupled dirac fermions. npj Quantum Mater. 5, 79 (2020).

Ayani, C. G. et al. Unveiling the interlayer interaction in a 1h/1t tas2 van der waals heterostructure. Nano Lett. 24, 10805–10812 (2024).

Parr, R. G. & Pearson, R. G. Absolute hardness: companion parameter to absolute electronegativity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 7512–7516 (1983).

Tilak, N. et al. Proximity induced charge density wave in a graphene/1t-tas2 heterostructure. Nat. Commun. 15, 8056 (2024).

Lee, J. et al. Honeycomb-lattice mott insulator on tantalum disulphide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 096403 (2020).

Lee, D., Jin, K.-H., Liu, F. & Yeom, H. W. Tunable mott dirac and kagome bands engineered on 1t-tas2. Nano Lett. 22, 7902–7909 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Visualizing the evolution from mott insulator to anderson insulator in ti-doped 1t-tas2. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 8 (2022).

Liu, C., Chatterjee, S., Scaffidi, T., Berg, E. & Altman, E. Magnetization amplification in the interlayer pairing superconductor 4hb-tas2. Phys. Rev. B 110, 024502 (2024).

Read, N. & Green, D. Paired states of fermions in two dimensions with breaking of parity and time-reversal symmetries and the fractional quantum hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 61, 10267–10297 (2000).

Ivanov, D. A. Non-abelian statistics of half-quantum vortices in p-wave superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 268–271 (2001).

Duckheim, M. & Brouwer, P. W. Andreev reflection from noncentrosymmetric superconductors and majorana bound-state generation in half-metallic ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 83, 054513 (2011).

Chung, S. B., Zhang, H.-J., Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological superconducting phase and majorana fermions in half-metal/superconductor heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 84, 060510 (2011).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Dudarev, S. L., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. J. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An lsda+u study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505 (1998).

Bae, H., Valentí, R., Mazin, I. I. & Yan, B. Dataset: designing flat bands, localized and itinerant states in tas2 trilayer heterostructures. Zenodo https://zenodo.org/records/15498908 (2025).

Acknowledgements

B.Y. acknowledged the financial support by the Israel Science Foundation (ISF: 2932/21 and 2974/23), German Research Foundation (DFG, CRC-183, A02), and by a research grant from the Estate of Gerald Alexander. I.I.M. was supported by the Office of Naval Research through the grant N00014-23-1-2480. R.V. acknowledges support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through QUAST-FOR5249 —449872909 (Project TP4) and Project No. VA117/23-1—509751747.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made contributions to the development of the approach and wrote the paper. H.B. performed the DFT calculations and prepared figures. R.V., I.I.M., and B.Y. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bae, H., Valentí, R., Mazin, I.I. et al. Designing flat bands, localized and itinerant states in TaS2 trilayer heterostructures. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 92 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00812-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00812-0

This article is cited by

-

Charge transfer empties the flat band in 4Hb-TaS2, except at the surface

Communications Physics (2026)

-

Designing flat bands, localized and itinerant states in TaS2 trilayer heterostructures

npj Quantum Materials (2025)