Abstract

Ising superconductors, known for their exceptionally high in-plane upper critical magnetic field (\({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\)) beyond the Pauli limit, have so far been explored mainly in two-dimensional limit systems and molecularly intercalated bulk materials based on transition metal dichalcogenides. By exploiting the high pressure approach, we simultaneously optimize the superconducting transition temperature (\({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\)) and \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) in a bulk 4Hb-TaS2 Ising superconductor. The pressure-optimized Ising superconductivity of 4Hb-TaS2 exhibits drastically enhanced \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) that is comparable to the performance of three-layer TaS2, while also with a record-high \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) surpassing all the TaS2-based systems reported so far. Combined in-situ high-pressure X-ray diffraction, Hall-effect measurements, and theoretical calculations, we reveal that the dome-shaped \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}(P)\) behavior of 4Hb-TaS2 arises from competition between superconductivity in the H-layers and charge density wave (CDW) orders in the T and H layers. Simultaneously, the dome-like response of \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) on pressure is governed by synergistic effects of interlayer coupling and spin-orbital coupling. These central findings provide a practical route to achieving record-high functionalities of Ising superconductivity with superior application potentials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A striking feature of Ising superconductors is their exceptional resilience to the Pauli paramagnetic limit under in-plane magnetic fields—a behavior starkly contrasting with conventional superconductivity1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. This property originates from strong spin-orbit coupling (SOC), which splits the electronic bands and locks electron spins out-of-plane in a rigid, antiparallel texture. Notably, Pauli screening of in-plane magnetic fields is mediated by electrons far from the Fermi level—states unaffected by superconductivity—ensuring the Pauli spin susceptibility stays intact and eliminating the thermodynamic drive to disrupt superconductivity. The protection mechanism dominates when both the Zeeman energy and superconducting gap are substantially smaller than the SOC splitting energy10. In this emerging and rapidly expanding field, two-dimensional (2D) transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) serve as important platforms for investigating Ising superconductivity1,2,3,4,5,6. In the non-centrosymmetric 1H-type TMD Ising superconductors, the band splitting induced by the strong SOC around the K/K’ point1,2,3,5, which are known as type-I Ising superconductors. Subsequently, type-II Ising superconductors have also been discovered in the 2D-limit systems, including few-layer stanene, PdTe2 films, and monolayered SnSe27,8,9,11. These systems do not invoke inversion symmetry breaking but are tied to band splitting at around the high-symmetry Γ point7,8. More recently, type-III Ising superconductors in atomically-thin natural 1H-TaSe2/SnSe van der Waals heterostructures have been found, which feature mirror-symmetric Fermi surfaces with anisotropic SOC, and exhibits anomalous in-plane magnetic field-enhanced superconducting transition temperature (\({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\)) with mixed spin-singlet and triplet pairing12. Among the studies on these diverse Ising superconducting materials, the regulation of interlayer coupling—including through tuning dimensionality or altering the constituent materials of heterostructures—plays a crucial role in shaping the properties of Ising superconductivity. Nevertheless, the above three types of Ising superconductor flakes exfoliated from bulk materials or epitaxially grown on proper substrates are often subjected to degradation and reduction in quality during the fabrication process13, which presents a mounting impediment to the pursuit of new Ising superconductors with potentially much higher in-plane upper critical field (\({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\)) for practical applications. To overcome this constraint, compelling advances have been made on realization of bulk Ising superconductors with intercalated inorganic14 or organic15,16 layer into the weakly coupled layers of bulk 2H-TMDs. The insertion of customized layered molecules also induces many novel physical phenomena such as chiral superconductivity16,17, striped electronic phases18, topological superconductivity19, and spontaneous vortices20. Given the conceptually vast phase space of candidate intercalation materials, it is highly desirable to identify the most superior intercalators to achieve maximally optimized Ising superconducting properties with much higher \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\)’s and \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\)’s for potential practical applications.

To date, two strategies have been applied to obtain large \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\)’s, namely, eliminating or weakening interlayer coupling and enhancing the SOC with heavier-element superconductors5,15. The interlayer coupling strength (\({t}_{\perp }\)) and SOC-induced band splitting (\({\Delta }_{\mathrm{so}}\)) are two key physical parameters determining the overall performance of Ising superconductors5,21,22. Not only the interlayer distance (D) between the 1H-TMDs, but also the diversities of the intercalators, such as the reported imidazole cations and (NaOH)0.5 into NbSe215,23, and insulating Ba3NbS5 into NbS224, play important roles in controlling the superconducting properties. Besides \({\Delta }_{\mathrm{so}}\) and \({t}_{\perp }\), charge density wave (CDW) often exists in the TMD systems and competes with superconductivity25,26,27, and such CDW orders need to be precisely controlled to benefit the superconducting order.

In this work, we report the striking discovery of a compressed bulk Ising superconductor in a single component TaS2 material, without invoking the prevailing approach of molecular intercalation, but with record-setting performances in Ising superconductivity. We achieve this goal by choosing the centrosymmetric 4Hb-TaS2 Ising superconductor17,28,29,30, in which the alternatively stacked superconducting 1H-TaS2 (with an incommensurate \(3a\times 3a\) CDW state) and Mott insulating 1T-TaS2 (with the commensurate David-of-star \(\sqrt{13}a\times \sqrt{13}a\) CDW state)17,31 layers. Notably, recently works have shown that for bulk Ising superconductors with inversion symmetry, the ratio of \({\Delta }_{\mathrm{so}}\) to \({t}_{\perp }\) plays a key role in regulating the in-plane upper critical field21,22. In particular, 4Hb-TaS2 belongs to a weakly coupled structure with inversion symmetry. Such samples allow us to apply high pressure as a clean and efficient knob to tune both the \({\Delta }_{\mathrm{so}}\) and \({t}_{\perp }\), and, crucially, to suppress the CDW orders in 4Hb-TaS2 in a mild pressure range up to 1.2 GPa. Surprisingly, we discover the optimized conditions to achieve the highest \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) of ~5 K and \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) of ~25 T, the latter reaching to the three-layer TaS2 performance. Furthermore, we observed dome-like behaviors of both \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) and \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) with pressure. With a suite of characterization tools of low temperature electrical transport measurements, Hall-effect measurements, in-situ high pressure X-ray diffraction (XRD), and first-principles calculations, we uncovered that the maximal enhancement of \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) at 0.8 GPa is the result of a synergistic effect of reduced interlayer coupling and increased SOC (i.e., an increase in \({\Delta }_{\mathrm{SO}}/{t}_{\perp }\)). The anomalous reduction in interlayer coupling under pressure is attributed to the distinctive compressive behaviors arising from anisotropic variations in the stacked 1T- and 1H-TaS2 layers.

Results

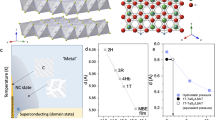

Ising superconductivity of 4Hb-TaS2 at ambient pressure

As schematically shown in Fig. 1a, the monolayered 1H-TaS2 belongs to space group \(P\bar{6}m2\) without inversion symmetry, which is recovered in the 2H-TaS2 phase consisting of two 1H-layers rotated by 180°. The 4Hb-TaS2 phase consists of alternating layers: 1H-TaS2, with locally broken inversion symmetry, and the Mott insulating 1T-TaS231, crystalizing in a hexagonal structure of space group P63/mmc. Figure 1b depicts the reciprocal space of the twinned and rotated CDW superlattices of 4Hb-TaS2 collected by single crystal XRD at ambient pressure and room temperature, which aligns with the previous measurements from electron diffraction31. This CDW phase in the 1T-layer of 4Hb-TaS2 can also be signified by the anomalous resistance jumps from electrical transport measurements. As shown in Fig. 1c, as the temperature decreases, both the in-plane and out-of-plane resistances show rapid increases at ~315 K and drop at ~22 K. The CDW transition temperatures of two types of layers can be identified from the derivatives of the R(T) curves shown in Supplementary Fig. S1 of the Supplementary Material. Note that the in-plane and out-of-plane transport behaviors of 4Hb-TaS2 exhibit high anisotropy: metallic for in-plane while semiconducting-like behavior for out-of-plane (see Fig. 1c) which is in line with the previous works31,32. Structurally, the interlayer distances between adjacent H − H (or T − T) layers within 4Hb-TaS2 are enlarged by about two times than that of 2H-TaS2 (or 1T-TaS2). Such enhanced two-dimensionality in 4Hb-TaS2 allows for an increase of \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) to ~3.8 K from that of bulk 2H-TaS2 (~0.6 K, ref. 33) which even surpasses the \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) of monolayered 1H-TaS2 (~3 K, ref. 5)consistent with previous reports32,34. The non-zero resistance of 4Hb-TaS2 at 2 K for ambient pressure and the broad superconducting transition are also observed in previous works, which results from low superconducting volume fraction of 4Hb-TaS2 (ref. 29). To check on the enhancement of two-dimensionality, we perform field scanning measurements at various temperatures near \({T}_{\text{c}}\) along in-plane and out-of-plane (see Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. S2). Both \({{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}{H}_{{\rm{c}}2}\left(T\right)\) along in-plane and out-of-plane for 4Hb-TaS2 exhibit a linear behavior across the entire temperature range. The \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }(0)\) of 4Hb-TaS2 is estimated to be \(15.3\pm 0.6\,{\rm{T}}\) by linear extrapolation at ambient pressure, and \(13.3\pm 0.6\,{\rm{T}}\) by fitting the Ginzburg-Landau (GL) formula: \({{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}{H}_{{\rm{c}}2}\left(T\right)={{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}{H}_{{\rm{c}}2}\left(0\right)\left[\left(1-{\left(T/{T}_{{\rm{c}}}\right)}^{2}\right)/\left(1+{\left(T/{T}_{{\rm{c}}}\right)}^{2}\right)\right]\)35, which are ~2 times the Pauli limit of \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{P}}}=6.99\,{\rm{T}}\), where \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{P}}}=1.84{T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) (refs. 36,37). Comparing with the 2D-limit Ising superconductors, the natural bulk superlattice of 4Hb-TaS2 renders the system more feasibility to combine external tuning tools to modulate both the interlayer and spin–orbital couplings38,39. Besides, the unicompositional and stable crystal structure of the bulk superlattice beyond the organic molecularly intercalated bulk heterostructures allows to be readily tuned by the pressure approach and to explore how the interlayer coupling affects the Ising superconductivity effectively.

a Crystal structures of monolayered 1H-TaS2, 2H-TaS2, and 4Hb-TaS2. b Single crystal XRD pattern of 4Hb-TaS2 at ambient conditions. The big lozenge outlined by the green dashed lines shows one unit cell of the reciprocal lattice of the basic 4Hb-TaS2 superlattice. The blue and red arrows indicate the jointly twinned and rotated vectors of the T-layer CDW (\({q=a}^{* }/\sqrt{13}\), φ = 13°54’). Here, \({a}^{* }\) and \({b}^{* }\) represent the reciprocal lattice parameters. c Anisotropic electrical transport data of 4Hb-TaS2. The criteria for determining the superconducting \({T}_{\text{c}}\) of 4Hb-TaS2 are indicated in the right inset, given by the intersection of the two extrapolated R(T) curves. The arrangements of the electrodes for out-of-plane (top) and in-plane (bottom) electrical transport measurements are also shown in the insets. d Temperature dependence of \({{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}{H}_{{\rm{c}}2}\) for 4Hb-TaS2 (including previous work on 4Hb-TaS1.99Se0.01, ref. 17) along the in-plane (θ = 90°, geometry defined in the inset) and out-of-plane (θ = 180°) directions. The dashed and solid lines are the linear fits.

Pressure-enhanced Ising superconductivity in 4Hb-TaS2

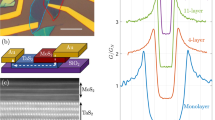

To investigate the interplay between superconductivity and CDW states, as well as the pressure-tuned phase diagrams of \({T}_{\text{c}}\) and \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) of 4Hb-TaS2, we have performed two independent sets: angle-rotated electrical transport measurements up to 1.2 GPa in the temperature range of 2–6 K for the first run and up to 3.0 GPa in the temperature range of 2–300 K for the second run. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S3, the \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) is enhanced from ~3.8 K at ambient pressure to a record-high ~5 K at 1.2 GPa for this system. The H-layer CDW state collapses at 0.5 GPa, while the T-layer CDW state is suppressed until 3.0 GPa (Supplementary Fig. S4). The pressure-tuned phase diagrams of superconductivity and charge density waves will be discussed in detail later. The Fig. 2a–c illustrate the angle-dependent upper critical field at 0.3, 0.8, and 1.2 GPa, respectively (\(\theta\) is defined as the angle between the sample surface normal (c axis) and the applied magnetic field as shown in Fig. 1d). The R(T) profiles for 0.8 GPa under external magnetic fields parallel and perpendicular to the ab-plane are illustrated in Figs. S5a-c. One can see that the \({{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}{H}_{{\rm{c}}2}(\theta )\) exhibits a cusp-like shape near 90° at all the pressures (Fig. 2a–c), which is one of the typical characteristics of 2D superconductors1,2,4. At a detailed level, for 0.3 GPa (Fig. 2a), all the data points can be well described by the 2D Tinkham model35 (red curve), remarkably distinct from the 3D Ginzburg-Landau (GL) model40 (green curve) at ~90°. The \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) at 0.3 GPa is about 40% gain from that at ambient pressure. As pressure increases up to 0.8 GPa (Fig. 2b), the extracted in-plane upper critical field reaches the highest value of \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\left(0\right)=24.9\pm 0.5\,{\rm{T}}\), almost doubling the ambient pressure value and more than tripling the Pauli limit. Upon further compressing (up to 1.2 GPa), \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) decreases sharply (see Fig. 2c). In Fig. 2b and c, the data near 90° (88° < θ < 92° for 0.8 GPa, and 82° < θ < 95° for 1.2 GPa) nicely follow the 2D Tinkham model. However, the \({{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}{H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) values out of these angle ranges are higher than the predictions of both the 2D Tinkham and 3D GL models, which may be associated with orbital-selective 2D superconductivity, as observed in 2H-NbS241. Comparing the \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) vs. \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) diagrams from the few-layer TaS2 systems (see Fig. 2d), we see clearly that the \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\left(0\right)\) value of bulk 4Hb-TaS2 at 0.8 GPa is comparable to that of mechanically exfoliated three-layer (3 L) TaS2 (ref. 5), while the \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) at zero field is much higher than that of both the 1 L and 3 L TaS2, indicating that pressurizing is an effective way to tune the Ising superconductivity, and can help to reach the 2D limit system.

a–c Angular dependences of the upper critical field \({{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}{H}_{{\rm{c}}2}\) at 0.3, 0.8, and 1.2 GPa, respectively. The solid lines represent the fittings with the 2D Tinkham formula35 (red) and the 3D anisotropic Ginzburg-Landau model (3D-GL)40 (green). The insets are the zoom-in views of the region near θ = 90°. d Temperature dependence of \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) for bulk 4Hb-TaS2 at ambient pressure (AP) or 0.8 GPa, as compared with the results of mechanically exfoliated 1 L and 3 L TaS2 extracted from ref. 5. The black dashed curves are fitted by the empirical equation \({H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\left({\rm{T}}\right)={H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }{(0)(1-T/{T}_{{\rm{c}}})}^{x}\) (ref. 15), with x = 0.56 and 0.7 for 1L- and 3L-TaS2, respectively. The blue solid curves are the results of fitting the GL formula35.

As another manifestation of the 2D nature, the vortex-antivortex unbinding transition of the Berezinskii–Kosterlitz–Thouless (BKT) type is expected for 2D superconductors42. The BKT transition temperature can be estimated by fitting the I-V curves as \(V\propto {I}^{\alpha }\), yielding \({T}_{{\rm{BKT\_IV}}}\), or fitting the R-T curves with equation \(R\left(T\right)={R}_{0}\exp (-\beta {t}^{-0.5})\), where \(t=T/{T}_{{\rm{BKT\_RT}}}-1\), and R0 and β are the fitting parameters depending on the material properties43. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S6a, the I-V curves at temperatures near \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) obey the power-law relations, and the \({T}_{{\rm{BKT\_IV}}}\) is determined with α = 3 (Supplementary Fig. S6b). The estimated \({T}_{{\rm{BKT\_RT}}}\) values at different pressures (Supplementary Fig. S6c) are in good agreement with \({T}_{{\rm{BKT\_IV}}}\) at corresponding pressures. Remarkably, the evolution of \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }(P)\) of 4Hb-TaS2 shows a dome-like shape peaked at ~0.8 GPa, while the \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\perp }(P)\) increases monotonically with pressure (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Structural evolution of 4Hb-TaS2 under high pressure

To gain further insight into the structural evolution of 4Hb-TaS2 under pressure, we have conducted in situ high-pressure XRD measurements up to 1.5 GPa. As shown in Fig. 3a, all the diffraction peaks shifted to higher angle during compression and no new peaks were observed, indicating that the 4Hb-TaS2 retains

a Powder XRD patterns between 0.1 and 1.5 GPa. b Normalized lattice parameters a and c (left) and ratio c/a (right) as functions of pressure. The solid lines are guides to the eye. c Pressure-dependent heights of the T-layer and H-layer (T-height and H-height as shown in the left panel) and interlayer distance d between the T-layer and H-layer. The solid lines are guides to the eye. Right label of (c): interlayer distance d (Å).

its ambient crystallographic symmetry up to 1.5 GPa. With assistance of Rietveld refinements, all the atomic positions in the unit cell can be obtained. As shown in Fig. 3b, the normalized

compression ratio \(a/{a}_{0}\) continuously decreases with pressure, while \(c/{c}_{0}\) and \(c/a\) both show obvious discontinuities at 0.8 GPa. Pressure-dependent layer heights of both the T- and H-layers exhibit a U-shape behavior, while the interlayer distance d shows a domed shape with a turning point at 0.8 GPa, as shown in Fig. 3c. As a result, the interlayer coupling between the T-layer and H-layer decreases in the pressure range of 0–0.8 GPa, and eventually increases with pressure beyond 0.8 GPa.

Discussion

To qualitatively analyze the pressure-tuned interlayer coupling and SOC of 4Hb-TaS2, we perform first-principles calculations of \({t}_{\perp }\) and \({\Delta }_{\mathrm{SO}}\) at different pressures (see Fig. 4a and more details in the Supplementary Material). As expected from the domed shape of the interlayer distance d(P), \({t}_{\perp }\) initially decreases with pressure below ~0.8 GPa, and increases in the pressure range of ~0.8–1.5 GPa. \({\Delta }_{\mathrm{SO}}\) initially increases rapidly with pressure below 0.5 GPa, and exhibits much smaller variations within 0.5 GPa < P ≤ 1.5 GPa. Consequently, the ratio of \({\Delta }_{\mathrm{SO}}/{t}_{\perp }\) with pressure (Fig. 4b) forms a distinct dome-like trend peaked around 0.75 GPa, qualitatively consistent with the \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }(P)\) shape shown in Supplementary Fig. S7. Thus, in the case of compressed 4Hb-TaS2, the interlayer and spin–orbital couplings synergistically boost the \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) below 0.8 GPa, reaching the maximal value around 0.8 GPa. The suppression of the CDW orders and enhancement of superconductivity by pressure are also illustrated in Fig. 4c. The H-layer CDW state is quickly suppressed at 0.5 GPa, aligned with the H-layer \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) enhancement from 3.1 K at ambient pressure to 3.9 K at 0.5 GPa. The T-layer CDW state is continuously suppressed upon further compression to 3.0 GPa, while the H-layer \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}(P)\) forms a dome-like shape. Such a behavior is similar to that of the recently reported compressed 6R-TaS244, where the suppression of superconductivity in H-layer can be attributed to the weakening of Josephson coupling associated with the presence of CDW fluctuations in the

a \({\Delta }_{\mathrm{SO}}\) and \({t}_{\perp }\) as functions of pressure. b Pressure-dependent ratio \({\Delta }_{\mathrm{SO}}/{t}_{\perp }\) extracted from first-principles calculations. The dashed lines in (a) and (b) are guides to the eye. c Transition temperatures of the CDW and superconducting orders as functions of pressure. d Phase diagram of \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) versus \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) for the TaS2-related materials. The blue symbols indicate the mechanically exfoliated TaS2 from monolayer to few layers5; the orange dot denotes chiral molecule–TaS2 (MBA-TaS2)16; the red triangle symbol represents the intercalated bulk 4Hb-TaS1.99Se0.0117; the black dot refers to the bulk 2H-TaS233; the green symbols represent the metal atom-intercalated TaS2 (from left to right: Pb0.03TaS2, LixTaS2, Cu0.03TaS2, Ni0.04TaS2, and Na0.1TaS2)55,56,57,58,59; the white dot denotes Ba0.75ClTaS214; the red circles represent compressed 4Hb-TaS2 presented in this work.

1T layers. Furthermore, we also performed high-pressure Hall effect measurements on 4Hb-TaS2 to probe carrier evolution across the phase diagram. At ambient pressure, the 10 K Hall response exhibits characteristic nonlinear behavior (Supplementary Fig. S8a)—attributed to H-layer CDW effects below its 22 K transition temperature32—while linear dependence dominates at 50 K (Supplementary Fig. S8b). Notably, the nonlinearity at 10 K precludes reliable extraction of quantitative carrier densities via conventional single-carrier models, and thus our analysis focuses on qualitative trends. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S9, under applied pressure, two distinct electronic transitions emerge: an initial Hall coefficient sign reversal at 0.5 GPa (10 K) coincides with H-layer CDW suppression observed in transport measurements (Fig. 4c), followed by a synchronized sign reversal near 0.8 GPa for both 10 K and 50 K data accompanied by discontinuous shifts in transport characteristics. Crucially, this 0.8 GPa anomaly correlates precisely with the structural distortion point (Fig. 3b, c), minimum interlayer coupling strength (Fig. 4a), and maximum in-plane upper critical field \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) (Fig. 4d), demonstrating that pressure-induced lattice modifications drive Fermi surface reconstruction which optimizes Ising superconductivity. A detailed comparison with previous works is shown in Fig. 4d. In particular, the structural and environmental stabilities of such a bulk 4Hb-TaS2 Ising superconductor allow us to consistently modulate its Ising superconductivity, with the \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) reaching the 2D limit of the nL-TaS2 systems, while simultaneously also demonstrating much higher \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\)’s. The enabled tunability also allows to comprehensively uncover the underlying mechanism of enhancement. This work provides a new avenue to optimize the properties of Ising superconductors.

In summary, we have established the compressed unicompositional bulk 4Hb-TaS2 superlattice as a Ising superconductor at high pressure, with superior or record-setting properties. Within a very mild pressure range, bulk 4Hb-TaS2 reaches the maximal \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) (~25 T at 0.8 GPa), approaching to the performance of 3L-TaS2, with \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) (~5 K at 1.2 GPa) surpassing all the TaS2-based systems reported so far. Here, we have presented the first demonstration of the successful enhancement of Ising superconductivity in a natural bulk van der Waals superlattice via pressure, and we unambiguously show the key role of CDW states, interlayer coupling, and the SOC in dominating the dome-like \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\left(P\right)\) and \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\left(P\right)\) phase diagram. The present strategy of utilizing pressure to modulate \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) and \({{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}{H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) can be readily extended to other bulk Ising superconductors15,16,22,24 and even monolayer, few-layer, or heterostructures systems45,46, which may lead to discoveries of Ising superconductors with the highest possible \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) and \({{{\rm{\mu }}}_{0}H}_{{\rm{c}}2}^{\parallel }\) values, along with unprecedented electrical, mechanical, and optical properties16,17,18,23 in bulk form. Thus, our research findings not only highlight the feasibility of introducing high pressure as a regulatory tool in the Ising superconductor material system, but also reveal the critical role of CDW states, interlayer coupling, and spin-orbit coupling in regulating Ising superconducting properties, thereby providing guidance for the future realization of Ising superconducting materials with record-breaking \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}\) and upper critical field.

Methods

Samples growth

4Hb-TaS2 single crystals were grown by the chemical vapor transport (CVT) method with iodine as the transport agent. Ta and S powders with mole ratio of 1:2 was weighted and mixed with 0.15 g/cm3 of I2 in a silica quartz tube. The tube was sealed under a high vacuum condition and heated for 20 days in a two-zone furnace, where the temperatures at the source and growth zone were fixed as 780 °C and 680 °C, respectively. Then the quartz tube was removed from the furnace and quenched into the ice water mixture immediately. Various sizes of single crystal 4Hb-TaS2 can be picked up from 10 s μm to about 1 mm.

Transport measurements

The in-plane electrical transport under ambient pressure was performed using the standard four-probe method, and the out-of-plane electrical transport adopted circular outer current leads with inner voltage leads between layers. The measurement configurations of in-plane and out-of-plane resistance are shown in the insets of Fig. 1c. The high pressure electrical transport measurements and the Hall effect measurements were conducted using the standard four-probe method under the van der Pauw configuration in a commercial PPMS (DynaCool, Quantum Design Corp.)47. High-pressure condition is generated in a screw-pressure-type diamond anvil cell (DAC), which is made of non-magnetic Be-Cu alloy. The diamond anvil culet is 400 μm. The non-magnetic Be-Cu gasket was pre-indented to 40-μm thick and the most of indented area was removed before adding the cubic boron-nitride (cBN) powder to the cavity to make the dense electrical insulation layer. A laser-drilled 200-μm hole serves as the sample chamber at the center of the cBN disk (thickness ~30 μm). A 4Hb-TaS2 single crystal (~100 μm × 100 μm × 10 μm) was first pre-glued with four 5-μm-thick Aurum (Au) foils and silver paste, then loaded into the sample chamber with silicone oil as the pressure transmitting medium (PTM). The DAC was placed in the C-MAG system with automatic temperature control. The high-magnetic-field transport measurements were performed at the Hefei High Magnetic Field Laboratory, Chinese Academy of Science, and in-house PPMS system at HPSTAR. All single crystal samples measured for the angle-rotated electrical transport measurements for ambient pressure (Fig. 1d), 0.3 GPa (Fig. 2a), 0.8 GPa (Fig. 2b), and 1.2 GPa (Fig. 2c) were cleaved from one large single crystal. The high-pressure electrical transport measurements in the temperature range of 2–300 K and pressure range of 0–3.0 GPa (see Supplementary Fig. S4) were conducted on another single crystal.

X-ray diffraction

In situ high-pressure angle dispersive XRD (wavelength 0.6199 Å) measurements of 4Hb-TaS2 in fine powder and single crystal forms at ambient pressure were performed at beamline BL-15U1 of Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF). The powder of 4Hb-TaS2 was loaded into a sample chamber prepared by a stainless-steel gasket. A symmetric DAC was used to generate quasi-hydrostatic pressure using silicone oil pressure transmitting medium. The pressure was monitored by the ruby fluorescence method48. The experimental parameters of the sample - detector distance and detector tiliting corrections were calibrated using the standard CeO2 powder diffraction. Two-dimensional XRD patterns were analyzed using Dioptas software49, yielding one-dimensional intensity versus diffraction angle profiles. Rietveld refinement analyses were performed with the GSAS software package50.

Theoretical calculations and determinations of \({\Delta }_{{\bf{SO}}}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{t}}}_{\perp }\)

The first-principles calculations were performed within density functional theory (DFT) implemented in the Vienna Ab initio simulation package (VASP)51, using the projector augmented wave (PAW) method51,52,53 and generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional54. To calculate \({\Delta }_{\mathrm{SO}}\equiv {\left\langle \Delta \left(k\right)\right\rangle }_{\mathrm{FS}}\), which represents the band splitting energy of the H-TaS2 layer in 4Hb-TaS2 (Supplementary Fig. S10a) averaged over the Fermi surface in the first Brillouin zone with the spin-orbit coupling (SOC), we construct a stacking structure model of the H-TaS2 layer. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S10b, this structure model is similar to 2H-TaS2 but adopts the experimental interlayer distance value in 4Hb-TaS2, which we refer to as enlarged-2H-TaS2. Under various pressures, the in-plane lattice constants of enlarged-2H-TaS2 also aligned with our experimental values for 4Hb-TaS2. It is important to note that, taking the case at 0 GPa as an example, the electronic structure of 1H-TaS2 (Supplementary Fig. S10c) is identical to that of enlarged-2H-TaS2, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S10d, indicating that there is almost no interaction between the 1H-TaS2 layers in 4Hb-TaS2. This is understandable because the distance between the two 1H-TaS2 layers (d2 = 8.34 ~ 8.95 Å under various pressures) is much larger than that between the neighboring T- and H-layer distance (d1 = 2.4 ~ 3.4 Å under same pressure range). Therefore, the interlayer coupling in 4Hb-TaS2 primarily arises from the neighboring T-phase and H-phase layers, as discussed in the Supplementary material. For enlarged-2H-TaS2, a fine k-mesh of 121 × 121 × 1 was used to calculate Fermi surface and band splitting energy with the SOC. To explore the interlayer coupling strength (\({t}_{\perp }\)) under different pressures, we define \({t}_{\perp }\equiv {\left\langle {P}_{H}\left(k\right)* \delta \left(k\right)\right\rangle }_{{FS}}\). Here, \({P}_{H}\left(k\right)\) represents the d-orbital weights of H-phase TaS2 at the k-point, \(\delta \left(k\right)\) denotes the band splitting energy of 4Hb-TaS2 at the k-point without the SOC, and \({\left\langle \ldots \right\rangle }_{{FS}}\) indicates the average over the Fermi surface. A fine k-mesh of 121 × 121 × 6 was used to calculate the Fermi surface of 4Hb-TaS2. It should be noted that the interlayer coupling leads to the hybridization of the bands between the H-phase and T-phase layers. The parameter \({P}_{H}\left(k\right)\) is introduced in this study to eliminate the interference of the T-phase electronic structures on the calculation results, making it reasonable to calculate only the magnitude of the band splitting energy of the H-phase under the influence of interlayer coupling.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are provided in the main text and the Supplementary Information. The original data is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Lu, J. M. et al. Evidence for two-dimensional Ising superconductivity in gated MoS2. Science 350, 1353–1357 (2015).

Saito, Y. et al. Superconductivity protected by spin–valley locking in ion-gated MoS2. Nat. Phys. 12, 144–149 (2016).

Xi, X. et al. Ising pairing in superconducting NbSe2 atomic layers. Nat. Phys. 12, 139–143 (2016).

Cui, J. et al. Transport evidence of asymmetric spin–orbit coupling in few-layer superconducting 1Td-MoTe2. Nat. Commun. 10, 2044 (2019).

de la Barrera, S. C. et al. Tuning Ising superconductivity with layer and spin–orbit coupling in two-dimensional transition-metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 9, 1427 (2018).

Wan, P. et al. Orbital Fulde–Ferrell–Larkin–Ovchinnikov state in an Ising superconductor. Nature 619, 46–51 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Type-II Ising superconductivity in two-dimensional materials with spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 126402 (2019).

Falson, J. et al. Type-II Ising pairing in few-layer stanene. Science 367, 1454–1457 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Type-II Ising superconductivity and anomalous metallic state in macro-size ambient-stable ultrathin crystalline films. Nano Lett. 20, 5728–5734 (2020).

Wickramaratne, D., Khmelevskyi, S., Agterberg, D. F. & Mazin, I. I. Ising superconductivity and magnetism in NbSe2. Phys. Rev. X 10, 041003 (2020).

Zeng, J. et al. Gate-induced interfacial superconductivity in 1T-SnSe2. Nano Lett. 18, 1410–1415 (2018).

Sun, X. et al. Tunable mirror-symmetric type-III Ising superconductivity in atomically-thin natural Van der Waals heterostructures. Adv. Mater. 37, 2411655 (2025).

Rhodes, D., Chae, S. H., Ribeiro-Palau, R. & Hone, J. Disorder in van der Waals heterostructures of 2D materials. Nat. Mater. 18, 541–549 (2019).

Shi, M. et al. Two-dimensional superconductivity and anomalous vortex dissipation in newly discovered transition metal dichalcogenide-based superlattices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 33413–33422 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Tailored Ising superconductivity in intercalated bulk NbSe2. Nat. Phys. 18, 1425–1430 (2022).

Wan, Z. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in chiral molecule–TaS2 hybrid superlattices. Nature 632, 69–74 (2024).

Ribak, A. et al. Chiral superconductivity in the alternate stacking compound 4Hb-TaS2. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax9480 (2020).

Devarakonda, A. et al. Evidence of striped electronic phases in a structurally modulated superlattice. Nature 631, 526–530 (2024).

Nayak, A. K. et al. Evidence of topological boundary modes with topological nodal-point superconductivity. Nat. Phys. 17, 1413–1419 (2021).

Persky, E. et al. Magnetic memory and spontaneous vortices in a van der Waals superconductor. Nature 607, 692–696 (2022).

Samuely, P. et al. Extreme in-plane upper critical magnetic fields of heavily doped quasi-two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 104, 224507 (2021).

Samuely, T. et al. Protection of Ising spin-orbit coupling in bulk misfit superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 108, L220501 (2023).

Sun, R. et al. High anisotropy in electrical and thermal conductivity through the design of aerogel-like superlattice (NaOH)0.5NbSe2. Nat. Commun. 14, 6689 (2023).

Devarakonda, A. et al. Clean 2D superconductivity in a bulk van der Waals superlattice. Science 370, 231–236 (2020).

Ugeda, M. M. et al. Characterization of collective ground states in single-layer NbSe2. Nat. Phys. 12, 92 (2015).

Xi, X. et al. Strongly enhanced charge-density-wave order in monolayer NbSe2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 765 (2015).

Lin, D. et al. Patterns and driving forces of dimensionality-dependent charge density waves in 2H-type transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 11, 2406 (2020).

Almoalem, A. et al. Charge transfer and spin-valley locking in 4Hb-TaS2. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 36 (2024).

Meng, F. et al. Extreme orbital ab-plane upper critical fields far beyond the Pauli limit in 4Hb-Ta(S,Se)2 bulk crystals. Phys. Rev. B 109, 134510 (2024).

Levitan, B. A., Oreg, Y. & Berg, E. Anomalous currents and spontaneous vortices in spin-orbit coupled superconductors. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 58 (2025).

Wilson, J. A., Di Salvo, F. J. & Mahajan, S. Charge-density waves and superlattices in the metallic layered transition metal dichalcogenides. Adv. Phys. 24, 117–201 (1975).

Gao, J. J. et al. Origin of the large magnetoresistance in the candidate chiral superconductor 4Hb-TaS2. Phys. Rev. B 102, 075138 (2020).

Garoche, P., Manuel, P., Veyssié, J. J. & Molinié, P. Dynamic measurements of the low-temperature specific heat of 2H-TaS2 single crystals in magnetic fields. J. Low. Temp. Phys. 30, 323–336 (1978).

Friend, R. H., Frindt, R. F., Grant, A. J., Yoffe, A. D. & Jerome, D. Electrical conductivity and charge density wave formation in 4Hb-TaS2 under pressure. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 10, 1013 (1977).

Tinkham, M. Effect of fluxoid quantization on transitions of superconducting films. Phys. Rev. 129, 2413–2422 (1963).

Chandrasekhar, B. S. A note on the maximum critical field of high-field superconductors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1, 7–8 (1962).

Clogston, A. M. Upper limit for the critical field in hard superconductors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 9, 266–267 (1962).

Yan, L. et al. Modulating charge-density wave order and superconductivity from two alternative stacked monolayers in a bulk 4Hb-TaSe2 heterostructure via pressure. Nano Lett. 23, 2121–2128 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Converting a monolayered NbSe2 into an Ising superconductor with nontrivial band topology via physical or chemical pressuring. Nano Lett. 22, 6767–6774 (2022).

Tinkham, M. Introduction to Superconductivity, 2nd edn (McGraw-Hill, 1996).

Bi, X. et al. Orbital-selective two-dimensional superconductivity in 2H-NbS2. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 013188 (2022).

Reyren, N. et al. Superconducting interfaces between insulating oxides. Science 317, 1196–1199 (2007).

Halperin, B. I. & Nelson, D. R. Resistive transition in superconducting films. J. Low. Temp. Phys. 36, 599–616 (1979).

Wang, S. et al. Pressure induced nonmonotonic evolution of superconductivity in 6R-TaS2 with a natural bulk Van der Waals heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 056001 (2024).

Xia, J. et al. Strong coupling and pressure engineering in WSe2-MoSe2 heterobilayers. Nat. Phys. 17, 92–98 (2021).

Ke, F. et al. Large bandgap of pressurized trilayer graphene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 9186 (2019).

Pauw, L. J. v. d. A method of measuring specific resistivity and Hall effect of discs of arbitrary shape. Philips Res. Rep. 13, 1–9 (1958).

Mao, H. K., Xu, J. & Bell, P. M. Calibration of the ruby pressure gauge to 800 kbar under quasi-hydrostatic conditions. J. Geophys. Res. Sol. Ea 91, 4673–4676 (1986).

Prescher, C. & Prakapenka, V. B. DIOPTAS: a program for reduction of two-dimensional X-ray diffraction data and data exploration. High. Press. Res. 35, 223–230 (2015).

Toby, B. EXPGUI, a graphical user interface for GSAS. J. Appl. Cryst. 34, 210–213 (2001).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Yang, X. et al. Anisotropic superconductivity in the topological crystalline metal Pb1/3TaS2 with multiple Dirac fermions. Phys. Rev. B 104, 035157 (2021).

Agarwal, T., Patra, C., Kataria, A., Chowdhury, R. R. & Singh, R. P. Quasi-two-dimensional anisotropic superconductivity in Li-intercalated 2H-TaS2. Phys. Rev. B 107, 174509 (2023).

Zhu, X. et al. Anisotropic intermediate coupling superconductivity in Cu0.03TaS2. J. Phys.-Condens. Mat. 21, 145701 (2009).

Li, L. J. et al. Superconductivity of Ni-doping 2H–TaS2. Phys. C. Supercond. 470, 313–317 (2010).

Fang, L. et al. Fabrication and superconductivity of NaxTaS2 crystals. Phys. Rev. B 72, 014534 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (under grants U2230401, 12204022, 11804011, 12404001, 12374458 and 12488101), the Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology under grants No. 2021ZD0302800, the Fundamental Research Funds for Inner Mongolia University of Science & Technology under grants No. 2024QNJS025, Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China under grants No. 2025QN01001, Keju Plan of Inner Mongolia University of Science and Technology under grants No. KJJH2023950, and the National Postdoctoral Foundation Project of China under grants No. GZC20230215. In situ high-pressure X-ray diffraction measurements were performed at the 15U1 station, Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), Zhangjiang Lab. Partial XRD work was completed at the Sector 13, Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory, and the BL10-XU station at Spring-8. GeoSoilEnviroCARS is supported by the National Science Foundation-Earth Sciences (EAR-1634415) and the Department of Energy-GeoSciences (DE-FG02-94ER14466). The Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility, is operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. We appreciate the technical support of Drs. S. Jiang, S. Kawaguchi, and Y. Ohishi. A portion of this work was performed on the Steady High Magnetic Field Facilities, High Magnetic Field Laboratory, CAS. The authors acknowledge the financial support from Shanghai Science and Technology Committee, China (No. 22JC1410300) and Shanghai Key Laboratory of Material Frontiers Research in Extreme Environments, China (No. 22dz2260800).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Y. and J.Q.G. contributed equally to this project. W.Y. conceived and designed the project. L.Y., X.W., and M.L. synthesized the single crystals. L.Y. performed high-pressure electrical transport and XRD measurements. L.W., C.J., T.L., C.X., N.L., J.Y.G., X.L., and J.N. assisted with conducting the high-pressure electrical transport measurements. N.L. and J.Y.G. assisted with conducting the high-pressure XRD measurements. J.Q.G., Z.H.Z., P.C., and Z.Y.Z. performed the DFT calculations. L.Y. and J.Q.G. co-wrote the manuscript, with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, L., Gao, J., Zhang, Z. et al. Enhanced Ising superconductivity in a unicompositional bulk 4Hb-TaS2 superlattice via pressure. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 104 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00823-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00823-x