Abstract

The recent discovery of altermagnets, which exhibit spin splitting without net magnetization, opens new directions for spintronics beyond the limits of ferromagnets, antiferromagnets, and spin-orbit coupled systems. We investigate spin-selective quantum transport in heterostructures composed of a normal metal and a two-dimensional d-wave altermagnet, and identify a universal mechanism for achieving perfect spin polarization. The mechanism is dictated by Fermi-surface geometry: closed surfaces in weak altermagnets yield partial and oscillatory spin filtering, whereas open surfaces in strong altermagnets intrinsically enforce fully spin-polarized conductance. Exploiting these distinct transport properties, we propose all-electrical spin-filter and spin-valve architectures, where resonant tunneling produces highly spin-polarized conductance tunable by gate voltage and interface transparency. Altermagnets with open Fermi surfaces further support gate-reversible perfect spin polarization that remains robust against interface scattering, disorder, and temperature. We also demonstrate an electrically controlled spin valve that reproduces the functionality of magnetic tunnel junctions without magnetic fields or relativistic mechanisms. d-wave altermagnets with open Fermi surfaces thus provide a new platform for low-dissipation, scalable, and magnetic-field-free spintronic devices, with potential for integration into next-generation quantum and CMOS-compatible technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Unconventional magnets have emerged as a new class of systems that lie beyond the traditional dichotomy of ferromagnets and antiferromagnets1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. These so-called third type of magnets support spin-split Fermi surfaces resembling those of ferromagnets12,13, yet exhibiting globally vanishing magnetization due to a compensated magnetic ordering, akin to antiferromagnets14,15,16. Depending on the momentum-space symmetry of the exchange field and the underlying crystalline symmetries, unconventional magnets can be classified according to the angular character of the spin splitting, including p-, d-, f-, g-, and i-wave types7,8,9,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. Among these, d-, g-, and i-wave magnets are known as altermagnets (AMs), characterized by simultaneously broken time-reversal symmetry and spatial rotational symmetry, but preserving their joint symmetry7,8. Altermagnets exhibit fully compensated spins and broken parity-time (PT) symmetry.3. Furthermore, AMs can also be classified according to their closed and open Fermi surfaces,7,8,24,25,26, leading to the concept of weak and strong AMs. In contrast, p- and f-wave magnets break only rotational symmetry but preserve time-reversal symmetry originating from nonsymmorphic lattice symmetries9,10, typically exhibiting closed anisotropic Fermi surfaces.

Unconventional magnets are promising platforms for spintronic devices13,14. The anisotropic spin split Fermi surface offers mechanisms for giant magnetoresistance27, spin-orbit-free anomalous Hall effects1,28,29,30,31, spin-transfer torques32,33,34, spin filtering effects35, spin pumping effects36, non-linear transports21, light-matter interactions37,38, light-induced spin density39, non-Hermitian electronic responses40,41, strongly correlation in Mott insulators42 and other novel phenomena43,44. These mechanisms are expected in experimentally accessible altermagnetic materials exhibiting novel spin transport, such as RuO228,30,45, MnTe29,31,46,47, Mn5Si331,47, CrSb48,49, FeS250, MnF251, Mn2Au52, La2O3Mn2Se2, Ba2CaOsO653 and La2CuO454.

In addition to their normal-state properties, unconventional magnets have recently garnered attention in the context of superconducting spintronics by inducting high-parities spin-triplet states39,55,56,57,58,59, orientation-dependent transport in altermagnetic-supercondctor hybridstructure25,26,26,60,61,62,63,64,65, gate-controlled Josephson junctions56,66,67,68,69,70, topological superconductors59,71,72,73,74,75, nonreciprocal field-free superconducting devices76,77,78 and their superconducting phenomena generated by the interplay between unconventional magnetism and superconductivity11. Together, these developments establish unconventional magnets as a fertile ground for exploring spintronic functionalities without net magnetization.

At the moment, there exist several proposals for spintronic devices based on AMs5,6,11. For instance, spin-dependent tunneling barriers have been shown to induce spin splitting in insulating AMs35. Alternatively, g-wave altermagnetic semiconductors have demonstrated strain-induced spin-orbit coupling, enabling gate-controlled spin splitting79. More recently, electrically gated spin-layer coupling can be achieved by applying different potentials to individual layers80. In recently developed ferroelectric-switchable AMs81,82, the spin-split Fermi surface can be reoriented by reversing the ferroelectric polarization. Despite these proposals offering a pathway toward AM-based spintronics, the unique non-relativistic nature of spin splitting in AM systems remains underutilized and largely unexplored. Furthermore, most theoretical and experimental efforts have focused on weak AMs, while the transport properties of strong AMs, featuring open Fermi surfaces, remain largely underexplored24,25,26. Thus, leveraging the intrinsic non-relativistic spin splitting of AMs for realizing spintronic functionalities without external magnetic fields remains an open and compelling challenge.

In this work, we explore spin-selective transport in heterostructures composed of AMs and normal metals, aiming to establish all-electrical spintronic functionality that harnesses the intrinsic, non-relativistic spin splitting of AMs. Two AM-based spintronics devices with fundamental interest are proposed, including a spin filter and spin valve (Fig. 1). In the regime of quantum-coherent transport, a conventional spin filter is realized in a ferromagnet junction, where the Zeeman splitting in combination with a build-up potential barrier gives rise to a spin-polarized flow since spin-up and spin-down electrons experience different barrier heights12,13,83. While the spin polarization of the current through the junction is determined by the magnetization of the ferromagnet, the applied barrier can tune the allowed occupation of states belonging to the lower Zeeman level and thus strengthen the spin filtering. In the proposed spin filter [Fig. 1(a)], a gate applied to the AM region generates switchable fully spin-polarized conductance by selectively blocking one spin channel, yet without requiring a Zeeman exchange field. Furthermore, two AM-based spin filters connected in series compose a spin valve [Fig. 1(b)]. This is similar to the conventional spin valve composed of a conventional magnetic bilayer, where only electrons with spin aligned to the magnetization contribute to the current12,13. Consequently, conductance is high when the magnetization directions of the two ferromagnetic layers are aligned, while it is suppressed when these directions are opposite, known as the parallel and antiparallel configurations, respectively. Parallel-antiparallel switching is typically achieved by applying an external magnetic field, which controls the relative magnetization orientations between layers. The resulting difference in conductance and thus the resistance under field reversal gives rise to the giant magnetoresistance effect84,85, which forms the basis for modern electronics applications such as data storage technologies, magnetic random access memory, and magnetic field sensors12,13,14,15,16. The behaviors analogous to the parallel-antiparallel switching are also found in the proposed spin valve based on strong AMs, where the alteration of the spin polarization in each spin filter is achieved by the applied gate [Fig. 1(b)], without an external magnetic field and net magnetization.

a spin filter and b spin valve. a In the spin filter, a gate applied to the AM region generates fully spin-polarized conductance by selectively blocking one spin channel. b The spin valve consists of two gated spin filters, exhibiting electrically tunable switching between high and low conductance states. This behavior is analogous to the parallel and antiparallel magnetization configurations in conventional ferromagnetic bilayer spin valves, but achieved here without magnetic fields and net magnetization.

To elaborate on the mechanism of these devices, we begin by classifying weak and strong AMs based on the competition between the spin-dependent exchange interaction and kinetic energy (Fig. 2). We find that their distinct Fermi surfaces give rise to qualitatively different transport characteristics when assembled into junctions (Fig. 3). In particular, quantum resonant tunneling leads to spin-selective conductance that can be controlled by a gate voltage and interface transparency. For weak AMs, spin filtering arises through barrier-enhanced conductance polarization due to the suppression of one spin species by the confinement effect86,87,88,89. In contrast, strong AMs enable fully spin-polarized conductance over wide energy ranges due to the intrinsic absence of one spin species near the Fermi level. We find that this intrinsic spin-filtering effect is robust against interface scattering and does not require magnetic fields or spin-orbit coupling (Fig. 4). Based on this mechanism, we further propose a double-gated spin valve device in a strong AM (Fig. 5). Interestingly, in this device, alternating between high and low conductance states can be realized by electrical gating, analogous to parallel and antiparallel spin configurations in conventional magnetic spin valves13,14 but without requiring net magnetization or an external magnetic field. Our results reveal that the non-relativistic spin splitting of AM offers a promising ground for engineering robust and tunable spintronic devices based entirely on electric field control. The proposed all-gate-controlled altermagnetic spin filter and spin valve are enabled by the intrinsic Fermi surface structure of weak and strong altermagnetic materials, without the need for net magnetization, relativistic spin-orbit coupling, or external magnetic fields.

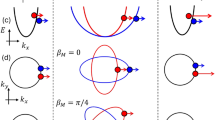

The insets exhibited the anisotropic Fermi surface at E/t = 1 for weak altermagnet and E/t = ± 1 for strong altermagnet as indicated by the horizontal dashed line. The spin-up (spin-down) subband is in blue (red). The altermagnetic strength is (a) J/t = 0.5 and (b) J/t = 1.5. Parameters: t = 1 is the energy unit and a = 1 is the lattice constant.

a Schematic illustration of the spin-filter effect. a-i The spin-filter is composed of normal metals and a gated altermagnet by Ug. The junction is along the x-direction, keeping periodic boundary conditions along the y-direction. a-ii The normal-metal leads exhibit spin-degenerate parabolic dispersions (black lines), while the weak AM features spin-dependent parabolic bands with the same curvature direction, with blue and red lines denoting the spin-up and spin-down states, respectively. The dispersions are exhibited along kx direction with ky = 0. a-iii: Isotropic Fermi surface of normal-metal leads and anisotropic closed and open spin-resolved Fermi surfaces for weak AMs. The Fermi surfaces are exhibited in kx-ky plane. Blue (red) shaded regions indicate transverse mode (ky) ranges forbidden for spin-up (spin-down) electrons due to the AM band structure. a-iv and a-v are the same as a-ii and a-iii, respectively, but for strong AMs. b Transmission probability, spin-resolved conductance and spin polarization for a weak AM. b-i and b-iii: Energy and incident-angle (θk) resolved transmission probabilities T↑ and T↓. b-ii and b-iv: Transmission for normal incidence (θk = 0) at various tunneling barrier heights V. The horizontal dashed line denotes the resonant energy levels [Eq. (13)] due to the confinement condition [Eq. (12)]. b-v and b-vi: Energy-dependent spin-resolved conductance and resulting spin polarization. c Same as (b), but for a strong AM. Parameters: UL = 0, Ug = 1, V = 0 in (i, iii, v), and junction length d = 20a. The \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave AM with θJ = 0 is considered.

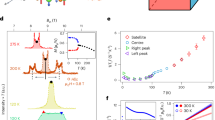

a, c: Spin-resolved conductance as a function of gate voltage Ug at fixed tunneling barrier V = 5. b, d: Spin polarization as a function of Ug for various values of V. The Fermi level is set to E = 0.1t, and all other parameters are identical to those in Fig. 3.

a Schematic illustration of a double-gate-controlled spin valve based on a strong altermagnetic heterostructure. The configuration enables gate-tunable switching between parallel (Ug1Ug2 > 0) and antiparallel (Ug1Ug2 < 0) regimes. b Total conductance and c spin polarization as functions of the gate voltages Ug1 and Ug2. The length of the altermagnetic region is d = 50a, and the tunneling barrier is set to V = 0.

Results

Weak and strong altermagnets

We start by introducing the Hamiltonian of d-wave AMs in continuum limit in the spin basis \({({\psi }_{{\boldsymbol{k}},\uparrow },{\psi }_{{\boldsymbol{k}},\downarrow })}^{{\rm{T}}}\)7,8

where

is the spin-resolved Hamiltonian for electrons with spin σ = + 1 (σ = − 1) being parallel (antiparallel) to the Néel vector, which is hereafter considered along z. The kinetic energy ξk and altermagnetic exchange field Jk are defined, respectively, as

Here, t is the nearest-neighbor hopping energy (set as the energy unit t = 1), and a is the lattice constant (set as a = 1). The two-dimensional momentum is denoted by k = (kx, ky), with magnitude k = ∣k∣ and polar angle \({\phi }_{k}=\arctan ({k}_{y}/{k}_{x})\). The parameter J represents the strength of the altermagnetic field, and θJ defines the angle between the altermagnetic lobe and the x-axis.

The momentum-dependent spin splitting is captured by Eq. (3), which describes a \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave (dxy-wave) AM when θJ = 0 (θJ = π/4)7,8, hosting an anisotropic spin split d-wave Fermi surface that depends on the momentum direction ϕk for a given θJ. The maximum altermagnetic effect occurs along momentum directions ϕk = θJ + nπ/2, with \(n\in {\mathbb{Z}}\), whereas it vanishes along directions ϕk = θJ + (2n + 1)π/4.

The competition between the altermagnetic term, Eq. (3), and the kinetic energy term, Eq. (4), defines weak and strong altermagnetism. To illustrate this effect, we first consider the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave AM as an example, whose dispersion can be obtained from Eq.(2) with θJ = 0, as

Figure 2 displays Eσ [Eq. (5)] as a function of kx,y. There are two directions of maximal altermagnetic effect, namely along the kx and ky axes for ky = 0 and kx = 0, respectively. Along these directions, the dispersion of a weak AM (J < t)25 consists of two upward-opening parabolas with spin- and direction-dependent curvature [Fig. 2(a)]. For a given energy E, the Fermi surface satisfies the equation of a standard ellipse,

which describes two spin-dependent elliptical Fermi surfaces with mutually orthogonal principal axes, with semi-major and semi-minor axes being \(\sqrt{E/(t+\sigma J)}/a\) and \(\sqrt{E/(t-\sigma J)}/a\) depending on spin, see the inset of Fig. 2(a).

In contrast, for a strong AM (J > t)25, the dispersion consists of two parabolic bands with opposite opening directions and spin-dependent curvature [Fig. 2(b)]. This arises because the sign of the effective mass, determined by the coefficients (t ± σJ)a2 in Eq. (5), changes along orthogonal momentum directions. As a result, the band structure hosts a saddle point90 at the spin-degenerate momentum (kx, ky) = (0, 0), where the curvature is positive in one direction and negative in the perpendicular one. Such a saddle point gives rise to a logarithmic van Hove singularity in the density of states near the corresponding energy90. The opposite opening directions of the spin-dependent bands allow electronic states to exist below E = 0, with spin-up and spin-down states shifted oppositely in energy [Fig. 2(b)]. This energy asymmetry arises from the spin-dependent curvature of the bands in orthogonal directions. As a result, the strong AM is characterized by open, spin-dependent anisotropic Fermi surfaces, which take the form of two orthogonally oriented sets of hyperbolas. These Fermi contours, distinct from the closed elliptical shapes found in the weak AM case, are described by

for a fixed energy E. These open Fermi surfaces impose directional constraints on the availability of spin-polarized electronic states. As shown in the inset of Fig. 2(b), for a given positive energy E, spin-up (spin-down) states are absent when \(a| {k}_{x}| < \sqrt{E/(t+J)}\) [\(a| {k}_{y}| < \sqrt{E/(t+J)}\)], due to the absence of real solutions for the corresponding hyperbolic Fermi contour. Conversely, for negative energies E < 0, spin-up (spin-down) states are absent when \(a| {k}_{y}| < \sqrt{| E| /(t-J)}\) [\(a| {k}_{x}| < \sqrt{| E| /(t-J)}\)]. This directional open Fermi surface is a hallmark of the strong altermagnetic regime and stands in sharp contrast to the weak AM case, where both spin species coexist over closed elliptical Fermi surfaces. While our discussions above are based on \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave AM with θJ = 0, the distinct properties such as the dispersions, Fermi surface geometry between weak and strong AM, are shared in all d-wave AM with arbitrary θJ. Remarkably, the distinct Fermi-surface geometries described by the continuum altermagnetic Hamiltonian [Eq. (1)] also emerge in lattice-model Hamiltonian fitted to real materials such as RuO228,30,45, La2O3Mn2Se2, and Ba2CaOsO653 (see Sec.I of the Supplemental Material). In the following, we therefore restrict our investigation to the continuum model, which clearly illustrates the underlying mechanism of spin-selective transport. This mechanism is further corroborated by the lattice model results presented in the Discussion section.

Spin-selective transport in altermagnetic junctions

The contrasting spin-split Fermi surfaces in weak and strong AMs give rise to qualitatively distinct transport responses for designing spintronic devices. A central objective in spintronics is generating and manipulating spin-polarized conductance or current, particularly through electrically tunable spin filters12,13,14,15,16. To explore this device, we consider a junction composed of an AM attached with two normal metal leads, as schematically shown in Fig. 3(a-i). This heterostructure supports a gate-controllable spin-filtering effect, enabled by the intrinsic energy- and momentum-dependent spin splitting in the altermagnetism. Using a quantum scattering formalism (see Methods), the spin-resolved transmission probability is given by

and the spin-resolved conductance at zero temperature reads91

where G0 = e2WkF/(2πh) is the conductance quantum per spin, W denotes the sample width, τσ is the transmission amplitude given by Eq. (26). The total conductance of the junction is given by the sum over spin channels:

where the spin indices ↑ and ↓ correspond to σ = + 1 and σ = − 1, respectively. In the linear response regime, the spin-resolved current under an applied bias Vbias is Iσ = GσVbias, and the total current follows as I = I↑ + I↓91. To quantify the relative contribution of each spin channel, we define the spin polarization as

where P > 0 (P < 0) indicates a dominant contribution from spin-up (spin-down) electrons. The spin polarization P serves as a measure of spin-filtering efficiency when a spin-degenerate electron beam is injected. In particular, P = + 1 (P = − 1) corresponds to a fully spin-polarized conductance and current carried entirely by spin-up (spin-down) states. The generation and electrical control of spin-polarized conductance and thus the current are essential goals in the development of spintronic devices.

Transport in weak altermagnetic junctions

Based on the quantum scattering formalism, in the following, we analyze transport through a spin filter based on a weak \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)[Fig. 3(a-ii) and (a-iii)], characterized by a closed, spin-dependent Fermi surface [Fig. 2(a)]. Figure 3(b) presents the energy- and angle-resolved transmission probabilities, as defined in Eq. (8), along with the resulting spin-resolved conductance [Eq. (9)] and spin polarization [Eq. (11)].

The spin-dependent transmission probabilities T↑ and T↓ are shown in Fig. 3(b-i) and (b-iii), respectively, as functions of the incident energy E and injection angle θk. The corresponding normal-incidence transmission profiles, T↑(θk = 0) and T↓(θk = 0), are plotted in Fig. 3(b-ii) and (b-iv) for different values of the tunneling barrier height V. Resonant transmission (Tσ = 1) occurs when the junction length d satisfies the standing-wave condition86, such that it equals an integer multiple of half the wavelength of spin-σ electrons in the altermagnetic region (See “Method”). The corresponding wavelength is given by \({\lambda }_{\sigma }=2\pi /{k}_{+}^{\sigma }\), where \({k}_{+}^{\sigma }\) [Eq. (24)] denotes the propagating wave vector of spin-σ electrons in the altermagnetic layer. This results in the resonance condition,

which ensures constructive interference between the left-going and right-going propagating modes in AM in Fabry-Pérot-like structures86,87,88,89. So that the phase difference accumulated over distance d between the two modes is an integer multiple of π. With this condition, one can check that the denominator of Eq. (26) becomes minimal, resulting in maximal transmission probability. The corresponding resonant energy levels related to the confined standing wave are

with t± = t ± σJ. Here, UL sets the chemical potential in the left (x < 0) and right (x > d) normal leads, Ug denotes the gate voltage applied to the central AM region, and V represents the tunneling barriers at the normal-AM interfaces located at x = 0 and x = d. The resonant energy [Eq. (13)] levels depend on the spin index σ, the transverse incident angle θk, and device parameters such as UL, Ug, and d, but are independent of the tunneling barrier V. Thus, the transmission probability remains unity even in the presence of a finite tunneling barrier V when the incident energy satisfies the resonance condition, \(E={E}_{n}^{\sigma }({\theta }_{k})\), but becomes strongly suppressed in the off-resonant regime, \(E\in ({E}_{n}^{\sigma },{E}_{n+1}^{\sigma })\) See Fig. 3(b-i)-(b-iii) for n = 1. The energy spacing between neighboring resonant levels is

which is spin-dependent. The level spacing decreases with increasing junction length d, but increases with the incident angle θk. Since \({\delta }_{E}^{+}({\theta }_{k}) > {\delta }_{E}^{-}({\theta }_{k})\), finite T↓ may appear in energy regions where T↑ is suppressed, see Fig. 3(b-i)-(b-iii). This asymmetry spin channel leads to spin-polarized tunneling. The degree of suppression increases with V, as the barrier height reduces the amplitude of evanescent modes within the altermagnetic region and enhances the energy selectivity of the resonance, thereby narrowing the transmission windows and increasing the contrast between on- and off-resonant transport. This behavior is illustrated in Fig. 3(b-ii) and (b-iv), which show the normal-incidence transmission probabilities T↑(θk = 0) and T↓(θk = 0), respectively, for various values of the tunneling barrier V. As V increases, transmission away from resonance is progressively suppressed, while the resonant peaks remain robust, highlighting the role of V in enhancing spin-dependent energy filtering. In the normal incident case, the lowest resonant peak occurs at \(E={E}_{1}^{\sigma }(0)=(t+\sigma J){(\pi a/d)}^{2}+{U}_{g}\approx {U}_{g}\) for long junctions (d ≫ a) and tunneling for E < Ug is negligible since the incident electron energy lies below the bottom of the spin-dependent parabolic dispersion set by Ug [Fig. 2(a-ii)]. For general injection angles, Eq. (13) implies that only electrons within a restricted angular range contribute to the transmission. This angular window is bounded by a critical angle \({\theta }_{c}^{\sigma }\) for spin σ, given by

Only electrons with incident angle \({\theta }_{k}^{\sigma } < {\theta }_{c}^{\sigma }\) can contribute to transmission. This spin-dependent critical angle arises from the anisotropic spin-split Fermi surface of AMs. For instance, in a \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) AM with θJ = 0, and a junction oriented along the x-direction Fig. 3(a-iii), spin-up electrons exhibit a broader angular transmission window compared to spin-down electrons.

By summing over all possible incident directions, the spin-resolved conductance Fig. 3(b-v) exhibits the spin-dependent resonance condition described by Eq. (12). Specifically, the spin-up conductance is significantly suppressed by the tunneling barrier except for the resonant peaks, while the spin-down conductance remains measurable. These resonant features correspond to constructive interference conditions for the spin-dependent wavefunctions inside the altermagnetic region. As the tunneling barrier height V increases, the off-resonant transmission is further suppressed, thereby enhancing the spin polarization P [Fig. 3(b-vi)]. However, because of the continuous and overlapping band structure of the weak AM, both spin channels inevitably contribute to transport for a given energy, see Fig. 3(b-i) and (b-iii). Electrons incident at oblique angles (θk ≠ 0) retain finite tunneling probabilities. This leads to a residual spin-up contribution that limits the maximum achievable spin polarization. Consequently, even in the presence of a high tunneling barrier, full spin polarization (P = 1 or − 1) is hardly achieved. Instead, the spin polarization saturates at approximately P ~ 80% for large V, as demonstrated in Fig. 3(b-vi).

The partial polarization in weak AM discussed above poses two notable challenges for device applications: (i) The maximum spin polarization is not fully tunable and remains sensitive to the Fermi energy E. This limits the flexibility of weak AM-based spin filters compared to conventional ferromagnetic systems12,13, where full spin polarization can be realized and externally modulated through magnetic fields92 or spin-transfer torques93. (ii) Enhancing spin filtering requires a high tunneling barrier, which inherently reduces the total conductance and the current. The inverse relationship between spin polarization and conductance imposes a fundamental constraint on device performance, especially in regimes where a sizable spin-polarized current is required for detection or functionality. While the challenge (i) can be mitigated by applying gate voltages to shift the resonance conditions as demonstrated in Sec. 2.3.1, the challenge (ii) is intrinsic to the weak AM band structure. However, as we show in the following, this limitation can be circumvented by employing strong AM materials. In that case, the emergence of spin-polarized transport arises from the intrinsic band structure of the strong AM itself, rather than relying on interfacial tunneling effects. This results in robust and fully spin-polarized transport, even in the absence of a tunneling barrier.

Transport properties in strong altermagnetic Junctions

The distinct dispersion of a strong AM [Fig. 2(b)] enables a fundamentally different electrically controlled transport behavior compared to its weak counterpart. In this case, we note that the resonant conditions in Eqs. (12)-(14) still apply. In particular, the spin polarization of the Fermi surface in a strong AM can be switched by tuning the energy, as illustrated in Fig. 3(a-iv), which is a behavior absent in weak AMs. As a result, spin-down (spin-up) electrons with \({\theta }_{k}^{-} < {\theta }_{c}^{-}\) (\({\theta }_{k}^{+} < {\theta }_{c}^{+}\)) are blocked for E > Ug (E < Ug), as shown in Fig. 3(c-ii) and (c-iii), respectively. This can also be understood from the possible Fermi surface contours at positive energy E, illustrated in the inset of Fig. 2(b). In this regime, spin-up (spin-down) states are absent when \(a| {k}_{x}| < \sqrt{(E-{U}_{g})/(t+J)}\) (\(a| {k}_{y}| < \sqrt{(E-{U}_{g})/(t+J)}\)). Conversely, at negative energies, spin-up (spin-down) states vanish when \(a| {k}_{y}| < \sqrt{(E-{U}_{g})/(t-J)}\) (\(a| {k}_{x}| < \sqrt{(E-{U}_{g})/(t-J)}\)), see Fig. 3(a-iv).

Consequently, transmission at E > Ug (E < Ug) is dominated by spin-up (spin-down) electrons, as shown in Fig. 3(c-i)-(c-iv). This feature is most pronounced for normally incident electrons, which is exclusively carried by spin-up (spin-down) states for E > Ug (E < Ug). Spin-up electrons with θk ≠ 0 are blocked for E < Ug due to the large forbidden angle range, leading to a fully spin-polarized transmission and thus conductance [Eq. (9)] in this energy regime, while for E > Ug, spin-down electrons with \({\theta }_{k} > {\theta }_{c}^{-}\) can still contribute to transmission at E > Ug, thereby reducing the degree of spin polarization. This behavior is reflected in the conductance and spin polarization shown in Fig. 3(c-v) and (c-vi).

Effects of the altermagnetic orientation θ J

We now examine the influence of the altermagnetic orientation angle θJ on the resulting spin polarization. For a \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave weak AM with θJ = 0, our analysis reveals that spin-polarized transport favors the spin-down channel, yielding P < 0, tunable via the incident electron energy E and the barrier height V [Fig. 3(b-vi)]. Rotating the orientation to θJ = π/2, corresponding to an equivalent \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave AM rotated by 90∘, reverses the spin polarization, resulting in P > 0. This configuration can be interpreted as reorienting the AM junction along the y-direction rather than the x-direction in Fig. 3. The reversal spin polarization arises from the interchange of spin-split subbands, effectively mapping the spin index σ → − σ in key transport signatures such as resonant energy levels and critical incident angles, thereby inverting the sign of P. In contrast, for a dxy-wave AM with θJ = π/4, transport is dominated by spin-degenerate propagation along the nodal directions (y = ± x), resulting in spin-independent transmission and vanishing net spin polarization.

Orientation-dependent transport reveals their alternating behavior of AM between ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic characteristics. Transport along directions of maximal spin splitting (e.g., θJ = 0 or π/2) exhibits ferromagnetic-like features, whereas spin-degenerate directions (e.g., θJ = π/4) give rise to antiferromagnetic-like effects. This anisotropy leads to orientation-dependent suppression of Andreev reflection60,61,62,63, the emergence of π-state Josephson currents, and nonreciprocal diode effects67,68,69,70, all without the need for an external magnetic field. The intrinsic spin splitting in \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave AM thus provides a highly tunable spin-selective transport, crucial for realizing spintronic functionalities in systems with zero net magnetization.

Gate-controlled spin filtering and spin valve effect in altermagnet junctions

The distinct energy dependence of the spin-resolved transmission and the resulting conductance (Fig. 3), enables gate-tunable spin transport in AM-based junctions, offering a promising platform for spintronic applications without net magnetization. In this section, we propose two electrically controlled spintronic devices that utilize the anisotropic spin splitting in \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave AMs: a spin filter [Fig. 3(a) and Fig. 4] and a spin valve [Fig. 5]. In both cases, the spin-resolved conductance Gσ and spin polarization P can be modulated by gate voltages applied within the AM region and at the tunneling barrier at the AM-lead interface. Notably, by exploiting the opposite band curvature of the spin-split subbands in strong AMs, we demonstrate a double-gate-controlled spin valve. This device exhibits a lower (higher) conductance state when the two gates are opposite (aligned), analogous to conventional spin valves based on ferromagnetic bilayers12,13, but realized here in a system with zero net magnetization.

Gate-controlled spin filter effects

The distinct energy-dependent conductance and polarization of strong and weak AMs enable gate- and barrier-controlled generation of spin-polarized conductance. To show this effect, Fig. 4 display the spin-resolved conductance and spin polarization of the total conductance as functions of the gate voltage Ug.

In the weak AM regime, the conductance exhibits spin-dependent oscillations as the gate potential Ug increases from zero Fig. 4(a), arising from quantum confinement effects87,88. The conductance peaks appear when the resonance condition [Eq. (12)] is satisfied. Between the resonance peaks, one spin channel is strongly suppressed by the tunneling barrier, while the other remains finite, leading to asymmetric spin-resolved conductances. This asymmetry gives rise to finite spin polarization P [Fig. 4(b)]. At low barrier strength (e.g., V = 0), the conductance is only partially spin-polarized, whereas at higher barriers (e.g., V = 10), a fully spin-polarized conductance is realized with a switchable polarization between P = + 1 and P = − 1 by tuning the gate voltage Ug.

In the case of strong AM, the conductance as a function of Ug exhibits a highly tunable behavior, persisting even for Ug < 0, see Fig. 4(c). This can be understood by the unique Fermi surface geometry of strong AM [Fig. 3(a-iv)], which leads to a regime in which the conductance is exclusively carried by spin-up electrons for Ug > 0 and by spin-down electrons for Ug < 0. As a result, the spin polarization reaches P = ± 1 and can be flipped simply by tuning the gate voltage, as shown in Fig. 4(d). Importantly, this spin filtering effect remains robust regardless of the interface transparency set by the tunneling barrier V, indicating that it arises from intrinsic bulk properties of the strong AM, rather than interfacial effects in the junction.

Beyond the demonstrated control of spin polarization, the AM-based spin filter offers several key advantages for practical implementation. First, because the spin polarization originates from intrinsic Fermi surface geometry rather than interface interference or external magnetic fields, the spin filtering mechanism is expected to be robust against moderate disorder and thermal broadening12,13,14,15,16. Second, the ability to reversibly and continuously tune both the magnitude and sign of P using a single electrostatic gate, without altering material composition or invoking spin-orbit coupling, distinguishes this approach from conventional spintronic platforms94,95. Finally, the momentum-selective spin filtering effect in strong AMs may be leveraged to design functional interfaces with superconductors or topological materials59,71,72,73,74,75 and spin-sensitive Josephson effects56,62,66,67,68,69,70. These features collectively underline the strong AM as a versatile and scalable building block for spintronic devices.

Electrically controlled spin valve based on strong AMs

The gate-controlled spin polarization flipping in the strong-AM spin filter can be further extended to realize a fully electrically tunable spin valve, a functionality inaccessible in weak AMs considered in this work. A conventional spin valve consists of two spin filters connected in series12,13. Each spin filtering effect is composed of a magnetic layer, where only electrons with spin aligned to the magnetization contribute to the current. High (low) conductance state occurs when the magnetization directions of the two ferromagnetic layers are aligned (opposite), denoted as parallel (antiparallel) configurations, which is switched typically by external magnetic field12,13,14,15,16.

The gate-tunability in the strong-AM junction enables the realization and manipulation of a spin valve effect with switchable parallel-like and antiparallel-like configurations without net magnetization and external magnetic field. The proposed device consists of a strong AM junction with two independently gated regions Fig. 5(a), characterized by gate voltages Ug1 and Ug2. Each gated region serves as a spin filter with spin-up (spin-down) polarization realized by the positive (negative) gate Fig. 4(c) and (d) As a result, when both gates are applied in the same direction (Ug1Ug2 > 0), spin-polarized conducting channels of identical spin species are activated in both regions Fig. 5(a), analogous to a conventional spin valve in the parallel configuration. Conversely, when the gate voltages are of opposite sign (Ug1Ug2 < 0), different spin-polarized channels are activated in each region Fig. 5(a), mimicking the antiparallel configuration of a conventional magnetic spin valve.

Crucially, unlike spin valves composed of ferromagnetic bilayers, where parallel-antiparallel switching requires external magnetic fields to reorient the magnetizations12, the strong-AM spin valve we proposed is entirely dependent on electrostatic gating. The effective spin polarization is governed by the intrinsic momentum-dependent spin-splitting and open Fermi surface of the strong AM [Fig. 2(b)], without requiring net magnetization or magnetic field control. This gate-controlled analog of ferromagnetic bilayers establishes strong AMs as a compelling platform for a fully electrical spintronic device.

By solving the scattering problem using the same procedure, the spin-resolved transmission Tσ in the spin valve configuration is obtained (see Method). Using Eqs. (9)-(11), the total conductance G and the resulting spin polarization P are evaluated. Their dependence on the gate voltages Ug1 and Ug2 is shown in Fig. 5(b) and (c), respectively. Figure 5(b) demonstrates the switching between high and low conductance states by tuning the relative values of the gate voltages Ug1 and Ug2 in the spin valve based on a strong AMs [Fig. 5(a)]. This effect originates from the opposite spin-dependent band-opening directions in strong AMs [Fig. 5(a)]. As a result, transmission through each gated region is dominated by spin-up (spin-down) electrons for positive (negative) gate voltages, consistent with the spin-filtering behavior shown in Fig. 4(d). A high-conductance state arises when Ug1Ug2 > 0, indicating aligned spin polarizations in the two gated AM regions Fig. 5(b). This configuration is analogous to the parallel alignment of magnetizations in conventional ferromagnetic spin valves13,14. More specifically, for Ug1, Ug2 > 0 ( < 0), transport is fully carried by spin-up (spin-down) carriers, yielding a spin polarization of P = + 1 ( − 1), as shown in Fig. 5(c). In contrast, when Ug1Ug2 < 0, the opposite spin polarization in the two gated regions leads to a strong suppression of conductance due to spin-filter mismatch, resulting in an ill-defined P through Eq. (11). This behavior is reminiscent of the antiparallel configuration in conventional spin valves, where spin-polarized electrons are blocked by the misaligned magnetic orientation of the second layer13,14.

The gate-tunable switching between high and low conductance states in the strong-AM-based spin valve originates from the opposite spin-dependent band-opening directions [Fig. 5(a)], which is absent in its weak-AM counterpart. This functionality arises from electrically controlled spin polarization in each gated strong-AM region, analogous to the spin-filtering behavior in conventional spin valves composed of ferromagnetic bilayers. However, unlike conventional spin valves, where switching between parallel and antiparallel configurations typically requires external magnetic fields or spin-transfer torques13,14, our design operates entirely through electrostatic gating. This enables faster, more energy-efficient control and facilitates integration with standard semiconductor platforms79. Moreover, the pronounced conductance contrast between the two gate configurations, together with the ability to reversibly switch spin polarization, offers a promising route toward nonvolatile spin-based logic and memory elements12,13,14,15,16. These results underscore the potential of strong AM as a robust platform for scalable, field-free, and all-electric spintronic device architectures without net magnetization.

As a final remark, although the double-gate spin valve is inaccessible in the weak-AM-based junction in the system concerned here. In recently developed ferroelectric-switchable AMs81,82, the spin-split Fermi surface can be reoriented by reversing the ferroelectric polarization. This effect is analogous to an electric-field-induced rotation of the altermagnetic orientation angle from θJ = 0 to θJ = π/2 in the present model. A gate-controlled spin valve is also conceivable in weak-AM-based junctions. Although such systems often involve multiple bands, which lie beyond the scope of the two-band model considered in this work, they also demonstrate the potential spintronics application of the AM-based junctions.

Discussion

The results discussed in the previous section are based on the continuum model of altermagnets [Eq. (1)] and the standard scattering approach (See Methods) for quantum transport at zero temperature. This approach offers a transparent way for unveiling the relationship between the emergent spin transport and the geometry of the Fermi surfaces in altermagnet-based devices: this is the key for understanding the realization of highly controllable spin-filter and spin-valve effects in altermagnet systems with open Fermi surfaces. The continuum model [Eq. (1)] provides the simplest framework for realizing open and closed Fermi surfaces by tuning the competition between the kinetic-energy and altermagnetic terms. In systems with closed Fermi surfaces [Fig. 3(b)], both spin channels contribute to the conductance, resulting in weak spin polarization; in contrast, systems with open Fermi surfaces possess momentum and energy windows where only one spin channel is active see Fig. 3(c), enabling fully spin-polarized transport. Thus, the presence of an open Fermi surface generically ensures the possibility of achieving perfect spin polarization.

While the continuum model [Eq. (1)] captures the fundamental mechanism, it does not account for several aspects essential to device architectures based on real materials and their implementation. These additional features, which cannot be fully addressed within the continuum description, are discussed within a lattice model analysis, involving the role of more realistic modeling, the effects of saddle points, as well as disorder and finite temperature, see below.

We first stress that the mechanism for fully spin-polarized transport, and related to the open Fermi surface, is not limited to continuum models but also occurs in more realistic lattice models, hence making our results universal, as we explain below. To demonstrate the universality of the mechanism behind our findings within the continuum model, we have carried out quantum transport Green’s function calculations lattice Green’s function technique91,96,97 for three representative lattice models, with the details given in the Supplementary Material, including (i) a spinful square lattice91,97,98, (ii) a two-sublattice tetragonal model99, and (iii) a six-band Lieb lattice model54. This confirms that our conclusions extend beyond the continuum models and connect to real materials based on experimental conditions.

In lattice models, the geometry of the equal-energy surface (open or closed) depends on the chosen energy. Thus, open Fermi surfaces can also arise in weak altermagnets. Consequently, weak altermagnets can yield stable and perfect spin polarization when the energy or gate voltage selects an open Fermi surface that favors one spin channel. This feature, absent in the continuum description [Eq. (1)], parallels the behavior of strong altermagnets, which always host open Fermi surfaces regardless of energy [see e.g. Fig. 2(b)]. The resulting conductance and spin polarization, therefore, justify our conclusion that open Fermi surfaces in altermagnets generically enable robust spin polarization. Besides, the lattice models demonstrate that weak AMs can also be beneficial for the spin filter and spin valve effects, which broadens the range of possible materials that can promote our predicted spin transport effects.

Particularly, the spin-filtering effect in the two-sublattice tetragonal model, with parameters guided by density functional theory calculations, connects directly to real materials99 (Sec. I.B in the supplemental material). For instance, the two-dimensional weak altermagnetic candidate RuO228 exhibits closed equal-energy surfaces at low energies and open ones at higher energies100. Moreover, open equal-energy surfaces have been reported in strong altermagnetic candidates such as MnTe31,47, La2O3Mn2Se2, and Ba2CaOsO653. Moreover, the Lieb lattice model further illustrates systems where weak and strong altermagnetic features coexist depending on the gate voltage, providing a natural description for materials such as La2CuO454.

In summary, the lattice-model calculations confirm the fundamental mechanism based on the simple and representative continuum model: stable and nearly perfect spin polarization arises from open Fermi surfaces, whereas closed Fermi surfaces yield unstable and only partially spin-polarized conductance, which is illustrated in Fig. 3.

In both the continuum and lattice models, there are several saddle points characterized by the high density of states existing in the altermagnetic systems [see e.g. Fig. 2(b) and Sec. I.A in the supplemental material]. However, in the device proposed here, the effect of saddle point(s) on the transport behaviors is negligible. This can be explained by the tunneling conductance101,102, which is proportional to T(E), the transmission probability across the central altermagnetic region, and the density of states, NL(R)(E), in the left (right) normal metal electrodes, i.e. G ∝ NL(E)NR(E)T(E) Thus, the conductance is related to the density of states of the electrodes rather than the altermagnets. Moreover, saddle points always occur at the extreme value of the dispersion, which implies that at these points \({\partial }_{{k}_{x}}E=0\). The transmission probability T(E), related to the velocity [\(T(E)\propto {v}_{x}\propto {\partial }_{{k}_{x}}E\)], thus vanishes around the saddle points. The influence of saddle points on conductance, and thus on spin polarization, is negligible.

Nevertheless, saddle points act as transition markers between closed and open surfaces in weak altermagnets, or between open surfaces with opposite spins (see Sec. I of the supplemental materials). These transition points are reflected in the vanishing conductance of one spin channel and the sharp jumps in spin polarization, see e.g. Fig. 4(b) and (d).

Moreover, our work focuses on the gate-tunable spin-dependent transport behaviors. This means (i), in equilibrium, Fermi levels are renormalized to be shared in three regions composing the junction (two electrodes and the central altermagnet may have different Fermi levels initially) and determined by the energy of the injecting electrons91; (ii) the applied gate voltage shifts the energy of the saddle points in the altermagnetic region, which can be closed to or near the Fermi level depending on the gates.

Introducing the lattice model enables us to examine the robustness of the spin-filtering effect against disorder. By incorporating random on-site disorder potentials into the spinful square lattice model (Sec.I of the Supplemental Material), we find that the high spin polarization achieved in altermagnets with open Fermi surfaces persists even under strong disorder. Remarkably, disorder can also induce perfect spin polarization in weak altermagnets with closed Fermi surfaces, which we attribute to the formation of an effective open Fermi surface.

The results above were obtained within the continuum model and quantum tunneling framework at zero temperature. The robustness of perfect spin polarization (P = ± 1) in altermagnets with open Fermi surfaces is further embodied in its persistence under finite temperature. The spin-resolved conductance at temperature T is given by

where \(f={[1+\exp ((E-{E}_{F})/{k}_{B}T)]}^{-1}\) is the Fermi–Dirac distribution. Here G0 and Tσ(E, θk) denote the conductance unit and spin-resolved transmission probability as in Eq. (9). At T = 0, Eq. (16) reduces to Eq. (9) since − ∂f/∂E → δ(E − EF).

For weak altermagnets with closed Fermi surfaces Fig. 6(a), increasing kBT broadens the resonant conductance peaks and partially restores the suppressed background Fig. 6(a-ii,iii). This thermal smearing reduces the spin polarization [Fig. 6(a-i)], as expected91. Nevertheless, finite spin polarization persists up to kBT ~ 0.01t, corresponding to T ~ 11.6 K for t ~ 100 meV. In contrast, strong altermagnets with open Fermi surfaces display qualitatively more robust behavior [Fig. 6(b)]. Despite thermal broadening, the gate-controlled switching between spin-up and spin-down currents remains sharp, and the polarization stays close to ± 1 up to kBT ~ 0.25t, corresponding to T ~ 290 K (room temperature). This places strong altermagnets with open Fermi surfaces among the most promising candidates for room-temperature spintronics92,103. The contrasting thermal stability can be traced to the Fermi-surface geometry. In the weak regime, closed Fermi surfaces host two spin channels of nearly equal weight, resulting in partial polarization sensitive to interface transparency, see Fig. 3(a, b). In the strong regime, open Fermi surfaces allow only a single spin channel at a given energy or gate voltage, leading to robust and nearly perfect polarization, see Fig. 3(a, c). These results substantiate our central claim: spin-filtering effects in altermagnets, particularly those with open Fermi surfaces, remain robust under finite-temperature conditions. Together with the disorder analysis, they confirm that Fermi-surface geometry is the key factor ensuring stable spin-selective transport in realistic experimental settings.

a-i Gate-controlled spin polarization for various temperatures kBT in a weak altermagnetic junction with J/t = 0.5. a-ii and a-iii: Gate-controlled conductance at low and finite temperatures with kBT = 0.001t and kBT = 0.1t, respectively. a-iv Spin polarization as a function of temperatures with specific gate voltage denoted by the vertical dashed lines in (a-i). b same as (a) but for a strong altermagnetic junction with J/t = 1.5. Parameters: same as Fig. 4.

Recent advances in material synthesis have demonstrated that epitaxial growth techniques can stabilize altermagnetism in thin films, paving the way for device integration. For example, epitaxial Mn5Si3 on Si(111), grown using MnSi seed layers, exhibits variant-sensitive anomalous Hall anisotropy in nanostructures31. Similarly, RuO2 thin films under epitaxial strain host altermagnetic phases with ordering temperatures above 500 K30. More recently, single-variant RuO2(101) films grown on r-plane Al2O3 substrates have displayed spin-splitting magnetoresistance in CoFeB bilayers, underscoring the decisive role of epitaxial control and variant selection104. These results highlight the importance of crystalline quality and epitaxial engineering, since both Mn5Si3 and RuO2 exhibit strong sensitivity of their transport signatures to structural quality and domain formation31. Maintaining a sharp Fermi-surface anisotropic geometry, therefore, requires high crystalline order and careful variant control.

Alongside material growth, interface engineering is crucial for realizing altermagnet-based devices (see e.g. Fig. 4). The integration of RuO2 into magnetic tunnel junctions has already produced measurable tunneling magnetoresistance28,29, establishing proof of principle for device functionality. These observations demonstrate that clean epitaxial interfaces, controlled oxygen stoichiometry, and minimized interfacial disorder are essential for preserving spin-polarized transport across junctions.

A central feature of our proposal is the use of gate-voltage control as a practical and all-electrical means to manipulate spin polarization without external magnetic fields. Altermagnets with open Fermi surface naturally support gate-reversible, fully spin-polarized transport that is robust against interface scattering. Recent theoretical studies have reinforced this prospect: CrS bilayers, for example, have been predicted to exhibit layer-spin locking, achieving sign-reversible spin polarization of up to ~ 87% at room temperature under out-of-plane electric fields105. Our results connect directly to these proposals by showing that open Fermi surfaces in altermagnets enable stable, gate-controlled spin filtering, establishing an electrical route to GMR-like functionalities without applied fields and thereby enhancing scalability.

Despite these advances, challenges remain for embedding altermagnets into larger spintronic architectures. Spin-memory loss at interfaces can suppress spin polarization during transmission106,107, while conductance mismatch between metallic altermagnets and semiconductors remains a well-known obstacle for efficient spin injection108,109. Furthermore, scalable device fabrication requires reproducible growth of epitaxial thin films with controlled variants and interfaces, as emphasized in recent spintronic roadmaps12,13. Promising strategies to address these limitations are emerging. Employing low-resistance altermagnet/normal-metal junctions can mitigate impedance mismatch and minimize spin-loss channels106. Heterostructures combining altermagnets with ferromagnets or topological materials have been proposed theoretically7,8,24,25,26, offering routes to multifunctional spintronic platforms. Crucially, the robust spin filtering we demonstrate, rooted in the open Fermi surfaces of strong altermagnets, ensures stable, gate-reversible, and fully spin-polarized transport. This intrinsic stability provides a decisive advantage over conventional ferromagnetic systems, where perfect polarization is rarely realized due to strong magnetization. The purely electrical tunability of altermagnets makes them naturally compatible with semiconductor-based and CMOS platforms, positioning them as promising building blocks for future large-scale spintronic circuits12,13.

We have identified a universal transport mechanism for achieving perfect spin-polarized conductance in altermagnet-based spintronic devices by utilizing the open Fermi surfaces of altermagnets. The mechanism is first illustrated in a pedagogical continuum model as a minimal and representative demonstration. By analyzing the interplay between the altermagnetic exchange interaction and kinetic energy, we classified altermagnets into weak and strong regimes, corresponding to closed and open spin-resolved Fermi-surface configurations, respectively. In the weak regime, the closed Fermi surface hosts two opposite spin channels that contribute nearly equally to transport. The resulting conductance is only partially spin-polarized and remains sensitive to interface transparency. In the strong regime, the open Fermi surface enables only a single spin channel at a given energy or gate voltage, producing a robust and nearly perfect spin polarization in the conductance. Building on the link between perfect spin polarization and open Fermi-surface geometry, we proposed an electrically tunable spin valve. In this device, double-gate control enables transitions between parallel and antiparallel spin configurations without requiring magnetic fields or net magnetization, in sharp contrast to conventional ferromagnetic spin valves. The functionality derives from the nonrelativistic spin splitting inherent to altermagnets and highlights their potential as a platform for scalable, all-electrical spintronic devices.

Lattice-model calculations further confirm the fundamental mechanism captured by the continuum model. Stable and nearly perfect spin polarization arises whenever transport involves open Fermi surfaces, whereas closed Fermi surfaces yield unstable and only partially polarized conductance. Moreover, open Fermi surfaces also emerge in weak altermagnets at certain energies, allowing perfect spin polarization and extending the pool of candidate materials for spin-filter and spin-valve effects. Perfect spin polarization enforced by open Fermi-surface topology is additionally shown to be robust against strong disorder and stable up to room temperature, underscoring the experimental feasibility of the proposed devices.

In conclusion, altermagnets with open Fermi surfaces provide a versatile route to all-electrically controlled perfect spin polarization. The results establish open Fermi-surface geometry as the key ingredient for spin-selective transport and pave the way toward the experimental realization of gate-tunable spin filters and spin valves in realistic altermagnetic compounds.

Methods

We consider a spin filter junction oriented along x direction, as shown in Fig. 3(a-i). This device is composed of a gated AM sandwiched between two normal metal leads. The spin filter can be controlled by the gate Ug applied in the AM region and the tunneling barrier at the interfaces between the normal leads and the AM. The Hamiltonian below models the junction

where

describes the electrostatic gating potential applied across the junction, with Θ(x) the Heaviside step function and \({\delta }_{x,{x}_{i}}\) the Kronecker delta. Here, UL sets the chemical potential in the left (x < 0) and right (x > d) normal leads, Ug denotes the gate voltage applied to the central AM region, and V represents the tunneling barriers at the normal-AM interfaces located at x = 0 and x = d. Here, we assume the chemical potentials in both leads are identical, and the same tunneling barriers are applied at the two interfaces. The AM occupies the central region 0 < x < d, with

and the notation \(\left\{\cdots \,\right\}\) in the third line of Eq. (17) indicates the anticommutator, ensuring the Hermiticity of the Hamiltonian86,96. Periodic boundary conditions are assumed along the y direction, so that ky is conserved throughout the three regions of the junction.

The transport properties of the junction can be obtained by solving the quantum scattering problem86,96. For a spin-σ incident electron with energy E in the direction θk, the eigenfunction is given by \({\Psi }^{\sigma }(x)={\psi }^{\sigma }(x){e}^{i{k}_{y}y}\), with

where rσ and τσ are the reflection and transmission coefficients, respectively, and c1,2 are the scattering amplitudes in the central AM region. The longitudinal and transverse momentum are defined as

and

in the normal lead region, with \({k}_{F}=\sqrt{(E+{U}_{L})/(t{a}^{2})}\) being the Fermi wave number of the incident electron. The electron injection angle satisfies

The longitudinal in the AM region is

with \(\Omega =\sqrt{({J}^{2}-{t}^{2})\,{a}^{2}{k}_{y}^{2}+{t}_{\sigma }(E-{U}_{g})}\,\text{,}\,\) and \({t}_{\sigma }=t+\sigma J\cos (2{\theta }_{J})\), which depends on the strength J, orientation θJ, and the gate Ug applied in AM, as well as the incident angle θk and energy E of the injecting electron. Using the boundary conditions associated with Eq. (17), we impose

where \({t}_{-\sigma }=t-\sigma J\cos (2{\theta }_{J})\) and \({V}_{\sigma }=V/{a}^{2}-\sigma iJ{k}_{y}\sin (2{\theta }_{J})\). By substituting the eigenfunction [Eq. (20)] into the boundary condition [Eq. (25)], the spin-resolved transmission amplitude is then given by

with

and α = ± 1. The spin-resolved transmission probability [Eq. (8)] can be obtained from Eq. (26).

To explain the transport mechanism within this electrically modulated spin valve shown in Fig. 5(a), we use Eq. (17) but with an electrostatic potential in AM given by

where, for simplicity, we assume that each gated region occupies half of the junction length d. The spin-resolved transmission Tσ, total conductance G, and spin polarization P can be calculated by solving the quantum scattering problem using the scattering states

with

In addition to the boundary conditions in Eq. (25), the wavefunction must also satisfy

By solving the scattering problem using the same procedure, the spin-resolved transmission Tσ in the spin valve configuration shown in Fig. 5(a) is obtained. Using Eqs. (9)-(11), the total conductance G and the resulting spin polarization P are evaluated. Their dependence on the gate voltages Ug1 and Ug2 is shown in Fig. 5(b) and (c), respectively.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Šmejkal, L., MacDonald, A. H., Sinova, J., Nakatsuji, S. & Jungwirth, T. Anomalous Hall antiferromagnets. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 482–496 (2022).

Shim, S. et al. Spin-polarized antiferromagnetic metals. http://arxiv.org/abs/2408.15532 (2024).

Cheong, S.-W. & Huang, F.-T. Altermagnetism classification. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 38 (2025).

Jungwirth, T., Fernandes, R. M., Sinova, J. & Smejkal, L. Altermagnets and beyond: nodal magnetically-ordered phases. http://arxiv.org/abs/2409.10034 (2024).

Bai, L. et al. Altermagnetism: exploring new frontiers in magnetism and Spintronics. http://arxiv.org/abs/2406.02123 (2024).

Yan, H., Zhou, X., Qin, P. & Liu, Z. Review on spin-split antiferromagnetic spintronics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124, https://pubs.aip.org/apl/article/124/3/030503/3037462/Review-on-spin-split-antiferromagnetic-spintronics (2024).

Šmejkal, L., Sinova, J. & Jungwirth, T. Beyond conventional ferromagnetism and antiferromagnetism: a phase with nonrelativistic spin and crystal rotation symmetry. Phys. Rev. X 12, 031042 (2022).

Šmejkal, L., Sinova, J. & Jungwirth, T. Emerging research landscape of altermagnetism. Phys. Rev. X 12, 040501 (2022).

Hellenes, A. B. et al. P-wave magnets 1–6. http://arxiv.org/abs/2309.01607 (2023).

Jungwirth, T. et al. From supefluid 3He to altermagnets. http://arxiv.org/abs/2411.00717 (2024).

Fukaya, Y., Lu, B., Yada, K., Tanaka, Y. & Cayao, J. Superconducting phenomena in systems with unconventional magnets. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.15400 (2025).

Hirohata, A. et al. Review on spintronics: Principles and device applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 509, 166711 (2020).

Nature Materials. New horizons in spintronics. Nat. Mater. 21, 1 (2022).

Din, A. D., Amin, O. J., Wadley, P. & Edmonds, K. W. Antiferromagnetic spintronics and beyond. npj Spintronics 2, 25 (2024).

Jungwirth, T. et al. The multiple directions of antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Phys. 14, 200–203 (2018).

Baltz, V. et al. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 231–241 (2016).

Tagani, M. B. CoF3: a g-wave Altermagnet (2024). http://arxiv.org/abs/2409.12526.

Ezawa, M. Third-order and fifth-order nonlinear spin-current generation in g-wave and i-wave altermagnets and perfect spin-current diode based on f-wave magnets. http://arxiv.org/abs/2411.16036 (2024).

Liu, P., Li, J., Han, J., Wan, X. & Liu, Q. Spin-group symmetry in magnetic materials with negligible spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. X 12, 021016 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Enumeration and representation theory of spin space groups. Phys. Rev. X 14, 031038 (2024).

Zhu, H., Li, J., Chen, X., Yu, Y. & Liu, Q. Magnetic geometry induced quantum geometry and nonlinear transports. Nat. Commun. 16 (2025).

Chen, X. et al. Unconventional magnons in collinear magnets dictated by spin space groups. Nature 640, 349–354 (2025).

Liu, Q., Dai, X. & Blügel, S. Different facets of unconventional magnetism. Nat. Phys. 21, 329–331 (2025).

Das, S., Suri, D. & Soori, A. Transport across junctions of altermagnets with normal metals and ferromagnets. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 35, 435302 (2023).

Das, S. & Soori, A. Crossed Andreev reflection in altermagnets. Phys. Rev. B 109, 245424 (2024).

Nagae, Y., Schnyder, A. P. & Ikegaya, S. Spin-polarized specular Andreev reflections in altermagnets. Phys. Rev. B 111, L100507 (2025).

Šmejkal, L., Hellenes, A. B., González-Hernández, R., Sinova, J. & Jungwirth, T. Giant and tunneling magnetoresistance in unconventional collinear antiferromagnets with nonrelativistic spin-momentum coupling. Phys. Rev. X 12, 011028 (2022).

Feng, Z. et al. An anomalous Hall effect in altermagnetic ruthenium dioxide. Nat. Electron 5, 735–743 (2022).

Gonzalez Betancourt, R. D. et al. Spontaneous anomalous Hall effect arising from an unconventional compensated magnetic phase in a semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 036702 (2023).

Tschirner, T. et al. Saturation of the anomalous Hall effect at high magnetic fields in altermagnetic RuO2. APL Mater. 11, 1–7 (2023).

Reichlova, H. et al. Observation of a spontaneous anomalous Hall response in the Mn5Si3 d-wave altermagnet candidate. Nat. Commun. 15, 4961 (2024).

Bai, H. et al. Observation of spin splitting torque in a collinear antiferromagnet RuO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 197202 (2022).

Karube, S. et al. Observation of spin-splitter torque in collinear antiferromagnetic RuO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 137201 (2022).

Han, S., Jo, D., Baek, I., Oppeneer, P. M. & Lee, H.-W. Harnessing magnetic octupole hall effect to induce torque in altermagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 076705 (2025).

Samanta, K., Shao, D.-F. & Tsymbal, E. Y. Spin filtering with insulating altermagnets. Nano Letters 25, 3150–3156 (2025).

Sun, C. & Linder, J. Spin pumping from a ferromagnetic insulator into an altermagnet. Phys. Rev. B 108, L140408 (2023).

Werner, P., Lysne, M. & Murakami, Y. High harmonic generation in altermagnets. Phys. Rev. B 110, 235101 (2024).

Farajollahpour, T., Ganesh, R. & Samokhin, K. Light-induced charge and spin hall currents in materials with c4k symmetry. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 29 (2025).

Fu, P.-H., Mondal, S., Liu, J.-F., Tanaka, Y. & Cayao, J. Floquet engineering spin triplet states in unconventional magnets. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.20205 (2025).

Reja, M. A. & Narayan, A. Emergence of tunable exceptional points in altermagnet-ferromagnet junctions. Phys. Rev. B 110, 235401 (2024).

Dash, G. K., Panda, S. & Nandy, S. Role of non-hermiticity in d-wave altermagnet. http://arxiv.org/abs/2408.08297 (2024).

Maznichenko, I. V. et al. Fragile altermagnetism and orbital disorder in Mott insulator latio3. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, 064403 (2024).

Lin, H.-J., Zhang, S.-B., Lu, H.-Z. & Xie, X. C. Coulomb drag in altermagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 136301 (2025).

Chen, Y., Liu, X., Lu, H.-Z. & Xie, X. C. Electrical switching of altermagnetism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 016701 (2025).

Liu, J. et al. Absence of altermagnetic spin splitting character in rutile oxide RuO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 176401 (2024).

Hariki, A. et al. X-ray magnetic circular dichroism in altermagnetic α-mnte. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 176701 (2024).

Rial, J. et al. Altermagnetic variants in thin films of Mn_5Si_3. Phys. Rev. B 110, L220411 (2024).

Ding, J. et al. Large band splitting in g -wave altermagnet CrSb. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 206401 (2024).

Yu, T. et al. Néel vector-dependent anomalous transport in altermagnetic metal crsb. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 47 (2025).

Li, S., Zhang, Y., Bahri, A., Zhang, X. & Jia, C. Altermagnetism and strain induced altermagnetic transition in Cairo pentagonal monolayer. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 83 (2025).

Faure, Q. et al. Altermagnetism revealed by polarized neutrons in MnF2. arXiv:2509.07087 (2025).

Elmers, H. J. et al. Néel vector induced manipulation of valence states in the collinear antiferromagnet Mn 2 Au. ACS Nano 14, 17554–17564 (2020).

Jaeschke-Ubiergo, R. et al. Atomic altermagnetism. arXiv:2503.10797v2 (2025).

Brekke, B., Brataas, A. & Sudbø, A. Two-dimensional altermagnets: Superconductivity in a minimal microscopic model. Phys. Rev. B 108, 224421 (2023).

Maeda, K. et al. Classification of pair symmetries in superconductors with unconventional magnetism. Phys. Rev. B 111, 144508 (2025).

Fukaya, Y. et al. Josephson effect and odd-frequency pairing in superconducting junctions with unconventional magnets. Phys. Rev. B 111, 064502 (2025).

Chakraborty, D. & Black-Schaffer, A. M. Constraints on superconducting pairing in altermagnets. arXiv2408.03999 https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.03999 (2024). ArXiv:2408.03999 [cond-mat.supr-con].

Sukhachov, P., Giil, H. G., Brekke, B. & Linder, J. Coexistence of p-wave magnetism and superconductivity. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.14245 (2024).

Chatterjee, P. & Juričić, V. Interplay between altermagnetism and topological superconductivity in an unconventional superconducting platform. https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.05451 (2025).

Sun, C., Brataas, A. & Linder, J. Andreev reflection in altermagnets. Phys. Rev. B 108, 054511 (2023).

Papaj, M. Andreev reflection at the altermagnet-superconductor interface. Phys. Rev. B 108, L060508 (2023).

Zhao, W. et al. Orientation-dependent transport in junctions formed by d-wave altermagnets and d-wave superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 111, 184515 (2025).

Niu, Z. P. & Yang, Z. Orientation-dependent Andreev reflection in an altermagnet/altermagnet/superconductor junction. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 57, 275301 (2024).

Maeda, K., Lu, B., Yada, K. & Tanaka, Y. Theory of tunneling spectroscopy in unconventional p-wave magnet-superconductor hybrid structures. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 93, 114703 (2024).

Niu, Z. P. & Zhang, Y.-M. Electrically controlled crossed Andreev reflection in altermagnet/superconductor/altermagnet junctions. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 37, 065003 (2024).

Zhang, S.-B., Hu, L.-H. & Neupert, T. Finite-momentum Cooper pairing in proximitized altermagnets. Nat. Commun. 15, 1801 (2024).

Lu, B., Maeda, K., Ito, H., Yada, K. & Tanaka, Y. ϕ Josephson junction induced by altermagnetism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 226002 (2024).

Sun, H.-P., Zhang, S.-B., Li, C.-A. & Trauzettel, B. Tunable second harmonic in altermagnetic Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. B 111, 165406 (2025).

Ouassou, J. A., Brataas, A. & Linder, J. dc Josephson effect in altermagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 076003 (2023).

Beenakker, C. W. J. & Vakhtel, T. Phase-shifted Andreev levels in an altermagnet Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. B 108, 075425 (2023).

Zhu, D., Zhuang, Z.-Y., Wu, Z. & Yan, Z. Topological superconductivity in two-dimensional altermagnetic metals. Phys. Rev. B 108, 184505 (2023).

Ghorashi, S. A. A., Hughes, T. L. & Cano, J. Altermagnetic routes to majorana modes in zero net magnetization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 106601 (2024).

Li, Y.-X. & Liu, C.-C. Majorana corner modes and tunable patterns in an altermagnet heterostructure. Phys. Rev. B 108, 205410 (2023).

Li, Y.-X. Realizing tunable higher-order topological superconductors with altermagnets. Phys. Rev. B 109, 224502 (2024).

Tanaka, Y., Tamura, S. & Cayao, J. Theory of majorana zero modes in unconventional superconductors. Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys. 2024, 08C105 (2024).

Banerjee, S. & Scheurer, M. S. Altermagnetic superconducting diode effect. Phys. Rev. B 110, 024503 (2024).

Cheng, Q., Mao, Y. & Sun, Q.-F. Field-free Josephson diode effect in altermagnet/normal metal/altermagnet junctions. Phys. Rev. B 110, 014518 (2024).

Chakraborty, D. & Black-Schaffer, A. M. Perfect superconducting diode effect in altermagnets. https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.07747 (2024).

Belashchenko, K. D. Giant strain-induced spin splitting effect in mnte, a g-wave altermagnetic semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 086701 (2025).

Zhang, R.-W. et al. Predictable gate-field control of spin in altermagnets with spin-layer coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 056401 (2024).

Duan, X. et al. Antiferroelectric altermagnets: antiferroelectricity alters magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 106801 (2025).

Gu, M. et al. Ferroelectric switchable altermagnetism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 106802 (2025).

P.Šeba, & Středa, P. Antisymmetric spin filtering in one-dimensional electron systems with uniform spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 256601 (2003).

Baibich, M. N. et al. Giant magnetoresistance of (001)Fe/(001)cr magnetic superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2472–2475 (1988).

Binasch, G., Grünberg, P., Saurenbach, F. & Zinn, W. Enhanced magnetoresistance in layered magnetic structures with antiferromagnetic interlayer exchange. Phys. Rev. B 39, 4828–4830 (1989).

Desai, B. R. Quantum Mechanics with Basic Field Theory (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Cayao, J., Prada, E., San-Jose, P. & Aguado, R. SNS junctions in nanowires with spin-orbit coupling: Role of confinement and helicity on the subgap spectrum. Phys. Rev. B 91, 024514 (2015).

Cayao, J. & Burset, P. Confinement-induced zero-bias peaks in conventional superconductor hybrids. Phys. Rev. B 104, 134507 (2021).

Rainis, D. & Loss, D. Conductance behavior in nanowires with spin-orbit interaction: a numerical study. Phys. Rev. B 90, 235415 (2014).

Ziletti, A., Huang, S.-M., Coker, D. F. & Lin, H. Van Hove singularity and ferromagnetic instability in phosphorene. Phys. Rev. B 92, 085423 (2015).

Datta, S.Electronic Transport in Mesoscopic Systems. Cambridge Studies in Semiconductor Physics and Microelectronic Engineering (Cambridge University Press, 1997), reprinted edition edn.

Moodera, J. S., Kinder, L. R., Wong, T. M. & Meservey, R. Large magnetoresistance at room temperature in ferromagnetic thin film tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 3273–3276 (1995).

Ralph, D. C. & Stiles, M. D. Spin transfer torques. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 320, 1190–1216 (2008).

Manchon, A., Koo, H. C., Nitta, J., Frolov, S. M. & Duine, R. A. New perspectives for Rashba spin–orbit coupling. Nat. Mater. 14, 871–882 (2015).

Galitski, V. & Spielman, I. B. Spin–orbit coupling in quantum gases. Nature 494, 49–54 (2013).

Fu, P.-H., Xu, Y., Liu, J.-F., Lee, C. H. & Ang, Y. S. Implementation of a transverse Cooper-pair rectifier using an N-S junction. Phys. Rev. B 111, L020507 (2025).

Fu, P.-H., Xu, Y., Yu, X.-L., Liu, J.-F. & Wu, J. Electrically modulated Josephson junction of light-dressed topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 105, 064503 (2022).

Fu, P.-H. et al. Field-effect Josephson diode via asymmetric spin-momentum locking states. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 054057 (2024).

Roig, M., Kreisel, A., Yu, Y., Andersen, B. M. & Agterberg, D. F. Minimal models for altermagnetism. Phys. Rev. B 110, 144412 (2024).

Fedchenko, O. et al. Observation of time-reversal symmetry breaking in the band structure of altermagnetic RuO2. Sci. Adv. 10, eadj4883 (2024).

Bardeen, J. Tunnelling from a many-particle point of view. Phys. Rev. Lett. 6, 57–57 (1961).

Gray, P. V. Tunneling from metal to semiconductors. Phys. Rev. 140, A179–A186 (1965).

Jiang, B. et al. A metallic room-temperature d-wave altermagnet. Nat. Phys. 21, 754–759 (2025).

He, C. et al. Evidence for single variant in altermagnetic RuO2 (101) thin films. arXiv:2508.13720 (2025).

Peng, R. et al. All-electrical layer-spintronics in altermagnetic bilayers. Mater. Horiz. 12, 2197–2207 (2025).

Rojas-Sánchez, J.-C. et al. Spin pumping and inverse spin Hall effect in platinum: The essential role of spin-memory loss at metallic interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 106602 (2014).

Korzhovska, I. et al. Spin memory of the topological material under strong disorder. npj Quantum Mater. 5, 39 (2020).

Schmidt, G., Ferrand, D., Molenkamp, L. W., Filip, A. T. & van Wees, B. J. Fundamental obstacle for electrical spin injection from a ferromagnetic metal into a diffusive semiconductor. Phys. Rev. B 62, R4790–R4793 (2000).

Awschalom, D. D. & Flatté, M. E. Challenges for semiconductor spintronics. Nat. Phys. 3, 153–159 (2007).

Acknowledgements

P.-H. Fu appreciates the support from W. Xu and the discussion from K. W. Lee and Z. Yuan. Q. Lv acknowledges financial support from Shenzhen University of Information Technology (Grant No. SZIIT2025KJ066). Y. Xu acknowledges financial support from the Scientific Research Starting Foundation of Ningbo University of Technology (Grant No. 2022KQ51) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2023M743783). J. C. acknowledges financial support from the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrå det Grant No. 2021-04121). J.-F. L. acknowledges financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12174077). X.-L.Yu acknowledges financial support from the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2023A1515011852) and the Shenzhen Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. JCYJ20250604174400001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.-H.F. and Q.L. contributed equally to this work. P.-H.F. conceived the idea, developed the theoretical model, performed calculations, and wrote the manuscript. Q.L. also performed calculations and contributed to manuscript writing. X.Y. and J.C. provided valuable insights and contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results. X.-L.Y. and J.-F.L. supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, PH., Lv, Q., Xu, Y. et al. All-electrically controlled spintronics in altermagnetic heterostructures. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 111 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00827-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00827-7

This article is cited by

-

Ferroelastic altermagnetism

npj Quantum Materials (2025)

-