Abstract

The van der Waals antiferromagnet CrSBr exhibits coupling of vibrational, electronic, and magnetic degrees of freedom, giving rise to distinctive quasi-particle interactions. We investigate these interactions across a wide temperature range using polarization-resolved Raman spectroscopy at various excitation energies, complemented by optical absorption and photoluminescence excitation (PLE) spectroscopy. Under 1.96 eV excitation, we observe pronounced changes in the \({A}_{g}^{1}\), \({A}_{g}^{2}\), and \({A}_{g}^{3}\) Raman modes near the Néel temperature, coinciding with modifications in the oscillator strength of excitonic transitions and clear resonances in PLE. The distinct temperature evolution of Raman tensor elements and polarization anisotropy of Raman modes indicates that they couple to different excitonic and electronic states. The suppression of the excitonic states' oscillation strength above the Néel temperature could be related to the magnetic phase transition, thereby connecting these excitonic states and Raman modes to a specific spin alignment. We develop a simple model that describes how magnetic order impacts excitonic states and hence the intensity and polarization of the Raman scattering signal. These observations make CrSBr a versatile platform for probing quasi-particle interactions in low-dimensional magnets and provide insights for applications in quantum sensing and quantum communication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A detailed investigation of quasi-particle interactions in quantum materials, involving charges, spins, excitons, and phonons, as well as the effects caused by these interactions, represents an important scientific challenge1,2,3,4. Understanding these phenomena is essential for progress in spintronics5,6, quantum sensing7,8,9, quantum communication, and quantum computing10,11.

Magnetic two-dimensional (2D) materials are particularly well-suited for exploring spin-phonon, electron-phonon, and exciton-phonon interactions12. For example, spin-phonon coupling has been studied in MPS3 compounds (M = Ni, Fe, Co, Mn)13,14,15 and in MnBi2nTe3n+1 (n = 1, 2, 3, 4)16. It was established how specific phonon modes couple with the magnetic subsystem both above and below the Néel temperature. For MPS3 compounds, it was shown that the variation of the strength of the coupling is attributed to changes in metal-sulfur bond lengths.

Recently, the novel van der Waals antiferromagnet with ferromagnetic intralayer spin alignment, CrSBr, has revealed striking features of various quasi-particle interactions17. Its unique quasi-1D crystal structure18 gives rise to strong anisotropy in electronic, magnetic, and optical properties19,20. Pawbake and coauthors21 reported strong spin-phonon coupling in bulk CrSBr samples using temperature- and magnetic-field-dependent Raman spectroscopy. As signatures of spin-phonon interaction, the authors point to Raman-mode intensity changes, the appearance of new Raman modes due to symmetry breaking caused by spin alignment, and higher-order scattering processes below the Néel temperature. Wdowik et al.22 likewise reported fingerprints of spin-spin and spin-phonon interactions, such as mode shifts and broadenings, via magneto-Raman measurements under circularly polarized excitation for a wide range of sample thicknesses. It was also shown that these coupling effects are more pronounced in thinner samples: Torres et al.23 observed a pronounced discontinuity in the temperature-dependent phonon energy of one of the optically active Raman modes. However, the aforementioned works do not explicitly consider the role of the electronic system.

As we showed in our earlier work24, Raman modes in CrSBr display strong sensitivity to excitation energy in the paramagnetic (PM) phase, exhibiting dramatic polarization changes for different excitation energies, revealing selective coupling of the Raman modes to specific electronic states. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the effects of the spin alignment on phonons involving electron-phonon and exciton-phonon interactions. Recent analyses of low-temperature photoluminescence (PL) spectra25 revealed discrete phonon sidebands, indicative of exciton-phonon coupling. Additional studies using magneto-optical spectroscopy and resonant Raman spectroscopy have further demonstrated the role of electron-phonon interactions in CrSBr18,26. In particular,26 showed that the Wannier-Mott-like B-exciton preferentially couples to out-of-plane lattice vibrations. However, many aspects of the mentioned interactions are under debate and remain unclear.

A powerful tool to probe hidden material properties is polarization-resolved Raman spectroscopy27,28. Polarization-resolved measurements across the magnetic phase transition provide essential insight into the system’s anisotropy and enable access to excitonic states of different polarization. Investigating Raman scattering together with optical resonances in absorption as a function of temperature allows us here to explore further how magnetization influences quasi-particle coupling in CrSBr. While very recent magneto-optical Raman study of CrSBr have focused on anisotropic spin-phonon coupling29, this work presents a previously unexplored exciton-mediated mechanism of spin-phonon interaction in CrSBr and provides new insights into the coupling between magnetic order and electronic excitations in layered materials.

Results

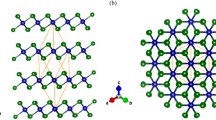

Raman modes polarization evolution under varying excitation

2D materials, including CrSBr, can be separated down to a monolayer by mechanical exfoliation30 due to the weak van der Waals forces that hold the layers of material together in the out-of-plane dimension. The crystal exhibits a pronounced structural anisotropy: it is elongated along the a crystallographic axis, known as the intermediate magnetic axis, while its shorter side corresponds to the b axis, the magnetic easy axis (Fig. S1). The out-of-plane direction corresponds to the c axis, the hard magnetic axis19. These crystallographic features define the electronic and optical properties of the material. The PL in CrSBr, from monolayer to bulk, is strongly polarized along the b axis, reflecting the anisotropy of the band structure (Fig. S2).

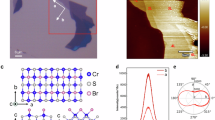

Raman scattering also exhibits polarization dependence18, but unlike PL, its polarization is sensitive to the excitation energy. In particular, altering the laser excitation energy enables switching of polarization direction between a and b axes of the Raman \({A}_{g}^{2}\) mode under ambient conditions24, as can be seen in Fig. 1. A typical Raman spectrum of CrSBr under 1.96 eV excitation (Figure S3, top panel) displays three major peaks corresponding to optically active out-of-plane vibrational modes: \({A}_{g}^{1}\), \({A}_{g}^{2}\), and \({A}_{g}^{3}\) known from the literature18,23,31.

Polar plots display the Raman scattering intensity as a function of the polarization rotation angle for the \({A}_{g}^{2}\) mode (blue solid line) and the \({A}_{g}^{3}\) mode (green solid line) under excitations of 1.96 eV (left column) and 2.33 eV (center column). Measurements are shown for different temperatures (4 K, 132 K, and 250 K), corresponding to distinct magnetic phases and characteristic transition temperatures. Solid lines with dots represent experimental spectra, dashed lines are fitting curves obtained using Eq. (1). The polarization angle is measured relative to the a axis (0o). The radial axis indicates signal intensity, which is scaled independently for each plot, with the center corresponding to 0 counts. Right column: schematics of spin orientations in stacked CrSBr layers across different magnetic phases: (top) paramagnetic (PM) above 165 K, (middle) intermediate magnetic phase (iFM) between 132 K (TN) and 165 K (TC), and (bottom) antiferromagnetic (AFM) below 132 KN.

In our previous study24, we showed that laser excitation energies of 1.96 and 2.33 eV lead to distinct behaviors of the \({A}_{g}^{2}\) mode. To provide a comparative study, we employed the same laser sources (see “Methods” Section) to excite a 5 nm thick sample region (blue circle in Fig. S1), see data in Fig. 1. Data for other thicknesses is shown for comparison in Figs. 2 and 3. Polarization-resolved Raman measurements were performed in a closed-cycle cryostat with precise sample temperature control in a co-polarized configuration, Fig. S4.

Temperature-dependent b/a ratio of the a \({A}_{g}^{1}\), b \({A}_{g}^{2}\), and c \({A}_{g}^{3}\) Raman modes under 1.96 eV excitation for different sample thicknesses. Each Raman mode exhibits characteristic behavior near the Néel temperature across a broad thickness range. The orange-shaded region marks the antiferromagnetic phase, the orange dashed line indicates the Néel temperature (TN = 132 K). The b/a ratios were extracted from fits of the polarization dependence using Eq. (1).

a, b PLE and corresponding DR/R spectra for a 5 nm thick CrSBr flake. Blue curves represent excitation polarized along the a axis, and red curves along the b axis. The intensities along the vertical axes are normalized. Green and red dashed lines serve as guides to highlight matching spectral features. d, e Equivalent measurements for a 31-nm-thick flake. c, f False-color maps showing the temperature evolution of DR/R signal polarized along b axis between 4 and 300 K for 5 nm (c) and 31 nm (f) thick flakes.

The electronic band structure also evolves with the sample temperature. In the magnetic semiconductor CrSBr, this evolution is closely intertwined with magnetic ordering. The system undergoes a transition from the PM phase to an intermediate ferromagnetic (iFM) phase at the Curie temperature (TC ~ 165 K), where interlayer ordering is only partial, exhibiting both ferro- and antiferromagnetic (AFM) interlayer couplings. Further temperature decrease leads to a transition to the AFM phase at the Néel temperature (TN ~ 132 K)21,32 (Fig. 1, right column). ARPES measurements showed that magnetic ordering induces shifts and exchange-driven splittings of specific bands, with energy scales significantly larger than those suggested by the transition temperature33. In addition, entering the PM phase leads to increased spectral broadening and reduced quasi-particle coherence due to the loss of long-range magnetic order33,34. As a result, Raman modes, electronic states, and magnetization in CrSBr are mutually coupled, collectively shaping the optical response of the system. To investigate this interplay, we report detailed polarization-resolved Raman scattering measurements for different laser energies across a wide temperature range from 4 to 300 K, focusing on the interplay between phonons and spin alignment in CrSBr.

For our measurements under 2.33 eV excitation, the polarization of the \({A}_{g}^{2}\) and \({A}_{g}^{3}\) modes remains fairly constant down to ~80 K: the \({A}_{g}^{2}\) mode is consistently polarized along the a axis, while the \({A}_{g}^{3}\) mode aligns along the b axis (Fig. 1, center column). Below ~80 K, however, the \({A}_{g}^{2}\) mode exhibits a notable change; its polar pattern acquires a slight four-fold symmetric component, indicating an additional signal component along the b axis. In contrast, the \({A}_{g}^{3}\) mode shows no such variation across the entire temperature range of 4–250 K.

The response under 1.96 eV excitation is dramatically different. For both \({A}_{g}^{2}\) and \({A}_{g}^{3}\) modes, temperature strongly affects the polarization dependencies (Fig. 1, left column). At room temperature, the \({A}_{g}^{2}\) mode is purely polarized along the b axis, but as the temperature decreases, its polar pattern changes significantly, with the a axis component growing until it becomes comparable to the b axis intensity. The \({A}_{g}^{3}\) mode follows a similar evolution, but with the a-component eventually exceeding the b-component below the Néel temperature. In both excitation cases (1.96 and 2.33 eV), the overall Raman intensity of all modes increases with decreasing temperature (Fig. 1).

The polar dependencies shown in Fig. 1 contain rich information that can be extracted by fitting the polar plots using the following expression27:

where parameters a and b correspond to the amplitudes along the a and b axes, respectively, and the phase ϕab accounts for the imaginary part of the Raman tensor elements related to an interplay of virtual and real intermediate states (see “Discussion” Section for details).

As it is evident from the polar plots, for the \({A}_{g}^{2}\) mode, the a-component increases by about 1.5 times under 2.33 eV excitation and more than 6.5 times under 1.96 eV excitation (Fig. S5a, b). For the \({A}_{g}^{3}\) mode, the a-component remains negligibly small at 2.33 eV, but rises nearly fourfold under 1.96 eV excitation (Fig. S5a, b). Unlike the relatively monotonous evolution of the a-component, the b-component shows a distinct kink near the Néel temperature (Fig. S5c, d). Importantly, this kink appears only for the \({A}_{g}^{2}\) mode under 2.33 eV excitation and only for the \({A}_{g}^{3}\) mode under 1.96 eV excitation. This suggests that, despite sharing the same symmetry, the \({A}_{g}^{2}\) and \({A}_{g}^{3}\) modes couple to different electronic states, which are selectively excited by different laser energies.

The absolute changes in all parameters are significantly more pronounced under 1.96 eV excitation, which can be attributed to its near-resonant character. As shown by the PL excitation spectroscopy and differential reflection measurements presented below, the 1.96 eV excitation energy lies on the shoulder of the main resonant features. Given these stronger effects observed at 1.96 eV, our subsequent discussion focuses on this case.

Raman tensor components evolution with temperature

To investigate the influence of band structure changes on near-resonant Raman scattering and to minimize interface effects originating from the top and bottom layers35,36, which are more pronounced in thinner samples, we performed measurements on flakes of various thicknesses (from 5 to 76 nm), expecting clearer behavior. For this purpose, polarization-resolved Raman spectroscopy over a wide temperature range was performed at various regions of the same sample (Fig. S1, markers denote different thickness regions). As a universal parameter illustrating the behavior of the Raman modes, we use the b/a ratio. Interestingly, each Raman mode exhibits a characteristic response feature near the Néel temperature across the broad thickness range (Fig. 2). The \({A}_{g}^{1}\) mode shows a step-like change in the b/a ratio at the Néel temperature, with the effect slightly more pronounced in thicker samples (Fig. 2a). \({A}_{g}^{2}\) mode displays no drastic change in the vicinity of the Néel temperature; however, the general trend remains. The discussion of the origin of the discontinuities in the \({A}_{g}^{1}\) and \({A}_{g}^{3}\) modes is presented in detail in the Discussion and Supplementary Information sections.

Our measurements show the most significant changes for the \({A}_{g}^{3}\) mode. Indeed, the b/a ratio of the \({A}_{g}^{3}\) mode displays a clear kink at the Néel temperature for all tested thicknesses, though the kink becomes progressively less sharp as thickness increases in Fig. 2c. For the 5 nm sample, the kink in the b/a ratio appears less pronounced, likely due to the extremely large a-component, which exceeds the b-component showing pronounced discontinuity below the Néel temperature (see components plotted separately in Fig. S6). Although temperature-dependent Raman responses vary slightly with sample thickness, the qualitative features remain consistent. These recurring signatures demonstrate that the underlying mechanism is robust against the thickness variation under study. Multiple samples with the same nominal thickness (5–6 nm) were measured, confirming the reproducibility of the observed effects. Minor variations between samples are most likely attributable to sample inhomogeneity, fluctuations, or polaritonic effects for the samples thicker than ~40 nm37,38. Moreover, pronounced excitation-energy dependence of the Raman polarization (Fig. 1) indicates that resonant conditions, excitation polarization, and magnetic order, rather than strain, interference, or sample inhomogeneity, govern the optical response.

Electronic states evolution with temperature

The Raman scattering results in Figs. 1 and 2 show sensitivity of the vibrational modes to magnetic order. We need to further investigate if the coupling of the Raman modes to magnetization is direct or mediated by electronic states excited by the laser in the Raman experiments. To achieve this target, we performed photoluminescence excitation spectroscopy (PLE) complemented by differential reflectance contrast (DR/R) measurements (Fig. 3). The PLE signal was obtained as the integrated signal under the so-called bright (XA) and dark (XD) exciton peaks39 (Fig. S2). The PLE and DR/R spectra show matching spectral features (peaks and dips) at similar energies.

For the few-layer sample (5 nm thick) at 4 K, pronounced peaks appear at 1.77 and 1.82 eV under excitation polarized along the b axis, while excitation along the a axis produces a peak at 1.96 eV (Fig. 3a, b). In the thicker 31 nm flake, the peak positions remain largely unchanged: excitation along the a axis shows little variation, but along the b axis, additional peaks emerge around ~1.86 and ~1.9 eV (Fig. 3d, e), which might relate to the polaritonic effects37,40. No clear resonances are observed near 2.33 eV (see Fig. S7 for extended data). In contrast, a clear resonance consistently appears near 1.96 eV polarized along the a axis for a range of thicknesses, perfectly matching the chosen excitation conditions for our Raman experiments. In thicker samples, the 1.96 eV excitation lies on the shoulder of an additional resonance. The near-resonant behavior is additionally supported by the appearance of extra peaks between 370 and 780 cm−1 under 1.96 eV excitation21, in contrast to the case of 2.33 eV excitation (Fig. S8).

The most pronounced PLE peak along the b axis is the one at 1.77 eV, which corresponds exactly to the so-called B-exciton (XB)26,41, which couples more strongly than XA to magnetization and phonons. Furthermore, the temperature dependence of DR/R under b axis excitation shows that strong spectral features near 1.96 eV vanish above the Néel temperature, clearly indicating their coupling to magnetic order, see Fig. 3c, f, as has been discussed in DR/R for the resonances near the XA exciton42. The apparent disappearance of the excitonic resonance in the DR/R spectra above the Néel temperature may arise from enhanced spectral broadening or a reduction in oscillator strength associated with the loss of long-range magnetic order33.

Discussion

The observed characteristic features can be understood within the following model.

The intensity of the Raman scattering is directly determined by the Raman tensor \(\widehat{R}\) and polarization vectors of the incident, ei, and scattered, es, fields as \({I}_{s}\propto | {{\bf{e}}}_{i}\widehat{R}{{\bf{e}}}_{s}{| }^{2}\). The Raman tensor in turn depends on both the crystal symmetry and the more importantly, the electron-phonon coupling. For the phonon modes of Ag-symmetry the non-zero components of the Raman tensor are \(a{e}^{i{\phi }_{a}}={R}_{aa}\), \(b{e}^{i{\phi }_{b}}={R}_{bb}\), and \(c{e}^{i{\phi }_{c}}={R}_{cc}\) where a, b, and c are the principal axes of the system:

Equation (1) follows from Eq. (2) with ϕab = ϕa − ϕb. Given the large energy difference between excitation photons and scattered phonons, direct light-phonon coupling is unlikely. Instead, Raman scattering is mediated by electronic excitations.

According to Peter et al.43, the Raman tensor component for a phonon branch μ (\({R}_{is}^{\mu }\)) reflects the sequence of physical processes underlying Raman scattering: (i) virtual or real transition from the ground state of the crystal \(| 0\rangle\) to one of the excited electronic states \(| n\rangle\), (ii) real process of the phonon emission with the transition between the excited states \(| n\rangle\) and \(| {n}^{{\prime} }\rangle\), the state \(| {n}^{{\prime} }\rangle\) can be both real or virtual, and (iii) photon emission from the state \(| {n}^{{\prime} }\rangle\) returning the crystal in the ground state. The Raman tensor components are therefore expressed as:

where EL is the laser excitation energy, En, \({E}_{{n}^{{\prime} }}\) are energies of intermediate electronic states \(| n\rangle\) and \(| {n}^{{\prime} }\rangle\), Γn, \({\Gamma }_{{n}^{{\prime} }}\) are their damping, \(\widehat{{\boldsymbol{p}}}\) is a momentum operator and \({H}_{el-ph}^{\mu }\) stands for the Hamiltonian of the electron interaction with the phonon mode μ with the energy \({E}_{ph}^{\mu }\). The indices i and s denote the polarization states of the incident and scattered photons, respectively.

It follows from the microscopic expression (3) that variations of the Raman scattering intensity and polarization across the magnetic phase transitions can be related to the specifics of light-matter coupling of the intermediate states. Indeed, the magnetic order is coupled to electronic excitations affecting both the optical transition matrix elements \(\langle n| {{\bf{e}}}_{i}\cdot \widehat{{\bf{p}}}| 0\rangle\), \(\langle 0| {{\bf{e}}}_{s}^{* }\cdot \widehat{{\bf{p}}}| {n}^{{\prime} }\rangle\), and electron-phonon interaction \(\langle {n}^{{\prime} }| {H}_{el-ph}^{\mu }| n\rangle\).

To figure out which intermediate states could be involved and how magnetic order affects the electron-phonon coupling, and therefore Raman intensity, let us first consider the simplest case of a single CrSBr layer, which can be extrapolated to a multilayer case in the vicinity of Néel temperature. In this system, the breaking of time-reversal symmetry as the material transitions from the PM to the ferromagnetic (FM) phase lifts the degeneracy of the excitonic states. The electron states with spins parallel and antiparallel to the magnetization are split owing to the exchange interactions. Only spin-conserving dipole transitions couple to light, namely \(| 1\rangle ={\uparrow }_{e}{\downarrow }_{h}\) and \(| 2\rangle ={\downarrow }_{e}{\uparrow }_{h}\), and phonon scattering between opposite-spin excitons is forbidden (see Supplement for technical details and involved approximations). The states \(| 1\rangle\) and \(| 2\rangle\) are related by the time-reversal symmetry. They are degenerate in the PM phase and split in the FM phase.

Assuming that the small variations of the temperature in the vicinity of the Curie temperature TC (for the case of single ferromagnetic layer) do not change the orbital character of the states \(| 1\rangle\) and \(| 2\rangle\), but only affect their energies, we observe the “Zeeman”-like splitting of excitonic resonances in the exchange field that appears in the FM phase:

where M(T) is the temperature dependent layer magnetization and ξ is the coefficient. M(T) behaves as44

where we neglected a very small range of temperatures in the very vicinity of TC where the “mean-field” result (5) becomes invalid.

Considering near-resonant Raman scattering and the fact that two states \(| 1\rangle\) and \(| 2\rangle\) mediate optical transitions, the Raman tensor components can be described by Eq. (S3) in the Supplementary Information. It follows then that the linear-in-M(T) contribution to the Raman tensor vanishes, and in the second order we have:

where the explicit expression for \({R}_{ii}^{{A}_{g}^{j},1}\) is derived in the Supplementary Information. Combining expression intensity of Raman scattering \({I}_{s}\propto | {R}_{ii}^{{A}_{g}^{j}}{| }^{2}\) and Eq. (6) we obtain that, as a function of temperature, the intensity of each scattered component has a contribution that smoothly depends on the temperature \({I}_{s}^{0}(T)\approx const+{const}^{{\prime} }\times T\), and a contribution propotional to M2(T) whose temperature derivative is not continuous

with \({I}_{s}^{1}\) being the coefficient.

Expression (7) describes strong changes of the intensity and polarization of the Raman scattering in the vicinity of the Curie temperature or Néel temperature in the AFM order case. The intensities of Raman matrix elements we observe (Figs. 2, S5, S6) for \({A}_{g}^{1}\) and \({A}_{g}^{3}\) modes are in clear agreement with Eq. (7), displaying pronounced discontinuity around Néel temperature.

To emphasize the role of intermediate electronic excitation states in spin-phonon interactions, we consider the evolution of excitonic states over the temperature range near the magnetic phase transition. As shown in Fig. 3c, f, the linear optical response of CrSBr crystals in the energy range of 1.6 …2 eV drastically changes in the vicinity of the Néel temperature, where the features related to the XB exciton practically vanish at T > TN. It might be caused by both the significant enhancement of the linewidth broadening (increase of \({\Gamma }_{n,{n}^{{\prime} }}\) in the denominator of Eq. (3)) as well as the reduction of the oscillator strength (optical transition matrix elements in the numerator of Eq. (3)) related to the magnetic disorder42. Hence, the almost-resonant contributions to the Raman scattering at EL = 1.96 eV mediated, e.g., by XB exciton become suppressed at T > TN, leading to changes of the magnitudes of a and b components and characteristic temperature-dependent evolution of the b/a ratio, linking these excitonic states and hence Raman modes to a specific magnetic phase. Different behavior of b/a amplitude ratio for \({A}_{g}^{1}\), \({A}_{g}^{2}\), and \({A}_{g}^{3}\) modes (Fig. 2) implies that different excitonic and electronic states underlie the light scattering by these modes.

Another observation supporting the indirect interaction between phonons and magnetic order is the absence of phonon-energy anomalies. The phonon energies (Raman shifts) evolve smoothly with temperature and exhibit no significant changes at the Néel temperature (Fig. S9). This behavior contrasts with earlier reports for CrSBr22,23 and 2D metal thiophosphates13 and indicates that the phonons are not directly coupled to the magnetic order. Combined with the pronounced excitation-energy dependence of the light-scattering intensity and polarization (Fig. 1), both correlated with PLE and absorption, these results confirm that excitons act as intermediate states in the Raman process. Our model (see Supplementary Information) further proves this interpretation by demonstrating that exciton-mediated Raman scattering naturally gives rise to magnetization-dependent effects.

Using temperature-dependent polarization-resolved Raman spectroscopy and measuring optical absorption, we demonstrate that, in addition to the previously reported excitation energy dependence24, the Raman modes of CrSBr are also sensitive to the magnetic phase through the complex interplay of electronic, magnetic, and vibrational states. In particular, we observe clear polarization changes for the three primary optically active Raman modes near the Néel temperature under 1.96 eV excitation and correlate these findings with optical absorption measurements. Temperature-dependent optical absorption combined with PLE spectroscopy reveals nearly resonant contributions to the Raman scattering, mediated by the high-energy transitions near the XB excitonic states, which become suppressed above the Néel temperature. The distinct temperature-dependent evolution of the b/a ratio for different Raman modes underscores the role of specific excitonic and electronic states involved in light scattering processes for each mode. We propose that the observed connection between the magnetic phase and phonon modes (spin-phonon interaction) arises indirectly via electron-phonon (exciton-phonon) coupling. Our findings highlight the intricate coupling among spin, lattice, excitonic, and electronic states in CrSBr.

Methods

Sample fabrication

Bulk CrSBr crystals were fabricated through chemical vapor transport45. The samples were prepared through mechanical exfoliation onto SiO2/Si substrates with an 85 nm SiO2 layer.

Atomic force microscopy

To probe the topology and thickness of the CrSBr flakes atomic force microscopy measurements were performed at room temperature on a Cypher AFM (Asylum Research/Oxford Instruments, Wiesbaden, Germany). Height images of CrSBr flakes were obtained in AC tapping mode using the cantilever AC160TSA-R3 (300 kHz, 26 N/m, 7 nm tip radius). Images were post-processed with the in-built software features of IGOR 6.38801 (16.05.191, Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA, USA).

Raman spectroscopy

Raman polarization-dependent measurements were performed using a home-built spectroscopy setup46. The sample was placed inside a closed-cycle cryostat (Attocube systems, AttoDry 800). For above-band-gap excitation HeNe laser (EL = 1.96 eV, Thorlabs) and a green diode-pumped solid-state laser (EL = 2.33 eV, Roithner LaserTechnik) were used. The incident light was polarized using a Glan-Laser prism and then rotated with a Liquid Crystal Rotator placed in front of the objective (50×, NA = 0.7, CryoGlass Optics) on a low-temperature piezo-positioners (Attocube systems, ANPx101 and ANPz102) to position the sample with respect to the objective. The objective in the reflection configuration focused the laser beam on the sample surface at normal incidence. The spot size diameter was of the order of the wavelength used, confirmed experimentally for different wavelengths by scanning the reflection signal over a metal stripe. Spectral purity of the excitation light was ensured by using corresponding MaxLine filters (Semrock). Raman signal was collected by the same objective and sent via free space to the spectrometer (Teledyne Princeton Instruments IsoPlane300) coupled with a liquid nitrogen-cooled CCD (Teledyne Blaze 400HRX). The collected signal was dispersed with 1200 lines/mm diffraction grating. A spectral blocking of the Rayleigh were made with a corresponding long-pass filters (Verona Long-pass Raman Edge Filter, Semrock). The average power for all measurements was maintained in the range of 200–400 μW. All measurements were performed in a co-polarization configuration provided by placing a Glan-Laser polarizer before the spectrometer with the optical axis parallel to the Glan-Laser polarizer in the excitation path.

Differential reflectance contrast (DR/R) and photoluminescence excitation spectroscopy (PLE)

DR/R and PLE spectroscopy were performed using the setup described in the previous section. As the excitation source, we utilized a continuous white light fiber laser (Fianium FIU-15, NKT Photonics) coupled with a tunable high-contrast filter (LLTF Contrast VIS HP8, NKT Photonics) providing the spectral line width of ~1 nm for PLE measurements or a broad line tunable filter (SuperK VARIA, NKT Photonics) for DR/R. For PLE measurement, the average incident power of 20 μW was maintained at each excitation energy from 1.46 to 2.76 eV with a gradient ND filter wheel and measured before the objective. The polarization of excitation light was set along the a or b crystallographic axis of a specific CrSBr flake. A 150 lines/mm diffraction grating was used.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are publicly available at the following link: https://tudatalib.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/handle/tudatalib/4929.

References

Freeman, S. & Hopfield, J. Exciton-magnon interaction in magnetic insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 21, 910 (1968).

Datta, B. et al. Magnon-mediated exciton–exciton interaction in a van der Waals antiferromagnet. Nat. Mater. 24, 1027–1033 (2025).

Liebich, M. et al. Controlling Coulomb correlations and fine structure of quasi-one-dimensional excitons by magnetic order. Nat. Mater. 24, 384–390 (2025).

Roberto de Toledo, J. et al. Interplay of energy and charge transfer in WSe2/CrSBr heterostructures. Nano Lett. 25, 13212–13220 (2025).

Zhang, B., Lu, P., Tabrizian, R., Feng, P. X.-L. & Wu, Y. 2D magnetic heterostructures: spintronics and quantum future. npj Spintronics 2, 6 (2024).

Gibertini, M., Koperski, M., Morpurgo, A. F. & Novoselov, K. S. Magnetic 2D materials and heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 408–419 (2019).

Radtke, M., Bernardi, E., Slablab, A., Nelz, R. & Neu, E. Nanoscale sensing based on nitrogen vacancy centers in single crystal diamond and nanodiamonds: achievements and challenges. Nano Futures 3, 042004 (2019).

Fang, H.-H., Wang, X.-J., Marie, X. & Sun, H.-B. Quantum sensing with optically accessible spin defects in van der Waals layered materials. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 303 (2024).

Melendez, A. L. et al. Quantum sensing of broadband spin dynamics and magnon transport in antiferromagnets. Sci. Adv. 11, eadu9381 (2025).

Zhong, H. et al. Integrating 2D magnets for quantum devices: from materials and characterization to future technology. Mater. Quantum Technol. 5, 012001 (2025).

Younis, M. et al. Magnetoresistance in 2D magnetic materials: from fundamentals to applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2417282 (2025).

Park, J.-G. et al. 2D van der Waals magnets: from fundamental physics to applications. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.02355 (2025).

Rao, R. et al. Mode-selective spin–phonon coupling in van der Waals antiferromagnets. Adv. Phys. Res. 3, 2300153 (2024).

Wei, Y. et al. Spin-orbital excitations encoding the magnetic phase transition in the van der Waals antiferromagnet FePS3. npj Quantum Mater 10, 61 (2025).

Dhakal, R., Griffith, S. & Winter, S. M. Hybrid spin-orbit exciton-magnon excitations in FePS3. npj Quantum Mater 9, 64 (2024).

Cho, Y. et al. Phonon modes and Raman signatures of MnBi2nTe3n+1 (n= 1, 2, 3, 4) magnetic topological heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 013108 (2022).

Göser, O., Paul, W. & Kahle, H. Magnetic properties of CrSBr. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 92, 129–136 (1990).

Klein, J. et al. The bulk van der Waals layered magnet CrSBr is a quasi-1D material. ACS Nano 17, 5316–5328 (2023).

Wilson, N. P. et al. Interlayer electronic coupling on demand in a 2D magnetic semiconductor. Nat. Mater. 20, 1657–1662 (2021).

Tabataba-Vakili, F. et al. Doping-control of excitons and magnetism in few-layer CrSBr. Nat. Commun. 15, 4735 (2024).

Pawbake, A. et al. Raman scattering signatures of strong spin-phonon coupling in the bulk magnetic van der Waals material CrSBr. Phys. Rev. B 107, 075421 (2023).

Wdowik, U. D., Varade, V., Vejpravova, J. & Legut, D. Magneto-Raman effect in van der Waals layered two-dimensional CrSBr antiferromagnet. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.15298 (2025).

Torres, K. et al. Probing defects and spin-phonon coupling in CrSBr via resonant Raman scattering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2211366 (2023).

Mondal, P. et al. Raman polarization switching in CrSBr. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 9, 22 (2025).

Lin, K. et al. Strong exciton–phonon coupling as a fingerprint of magnetic ordering in van der Waals layered CrSBr. ACS Nano 18, 2898–2905 (2024).

Smiertka, M. et al. Unraveling the nature of excitons in the 2D magnetic semiconductor CrSBr. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2506.16426 (2025).

Pimenta, M. A., Resende, G. C., Ribeiro, H. B. & Carvalho, B. R. Polarized Raman spectroscopy in low-symmetry 2D materials: angle-resolved experiments and complex number tensor elements. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23, 27103–27123 (2021).

Ferrari, A. C. & Basko, D. M. Raman spectroscopy as a versatile tool for studying the properties of graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 235–246 (2013).

Zhai, Y. et al. Anisotropic magneto-optical raman response coupled with magnetic ordering in an A-type antiferromagnet. Nano Lett. 25, 12570–12577 (2025).

Liu, F. Mechanical exfoliation of large area 2D materials from vdW crystals. Prog. Surf. Sci. 96, 100626 (2021).

Long, F. et al. Ferromagnetic interlayer coupling in CrSBr crystals irradiated by ions. Nano Lett. 23, 8468–8473 (2023).

Pei, F. et al. Surface-sensitive detection of magnetic phase transition in van der Waals magnet CrSBr. Adv. Funct. Mater 34, 2309335 (2024).

Watson, M. D. et al. Giant exchange splitting in the electronic structure of a-type 2D antiferromagnet CrSBr. npj 2D Mater Appl 8, 54 (2024).

Bianchi, M. et al. Paramagnetic electronic structure of CrSBr: Comparison between ab initio GW theory and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 107, 235107 (2023).

Sun, Y., Wang, R. & Liu, K. Substrate induced changes in atomically thin 2-dimensional semiconductors: Fundamentals, engineering, and applications. Appl. Phys. Rev 4, 011301 (2017).

Gerber, I. C. & Marie, X. Dependence of band structure and exciton properties of encapsulated WSe2 monolayers on the hBN-layer thickness. Phys. Rev. B 98, 245126 (2018).

Li, C. et al. 2D CrSBr enables magnetically controllable exciton-polaritons in an open cavity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2411589 (2024).

Nessi, L., Occhialini, C. A., Demir, A. K., Powalla, L. & Comin, R. Magnetic field tunable polaritons in the ultrastrong coupling regime in CrSBr. ACS Nano 18, 34235–34243 (2024).

Krelle, L. et al. Magnetic correlation spectroscopy in CrSBr. ACS Nano 19, 33156–33163 (2025).

Dirnberger, F. et al. Magneto-optics in a van der Waals magnet tuned by self-hybridized polaritons. Nature 620, 533–537 (2023).

Shi, J. et al. Giant magneto-exciton coupling in 2D van der Waals CrSBr. ACS Nano 19, 29977–29987 (2025).

Shao, Y. et al. Magnetically confined surface and bulk excitons in a layered antiferromagnet. Nat. Mater. 24, 391–398 (2025).

Peter, Y. & Cardona, M. Fundamentals of Semiconductors: Physics and Materials Properties (Springer Science & Business Media, 2010).

Landau, L. D. & Lifshitz, E. M. Statistical Physics: Volume 5, Vol. 5 (Elsevier, 2013).

Klein, J. et al. Control of structure and spin texture in the van der Waals layered magnet CrSBr. Nat. Commun 13, 5420 (2022).

Shree, S., Paradisanos, I., Marie, X., Robert, C. & Urbaszek, B. Guide to optical spectroscopy of layered semiconductors. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 39–54 (2021).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Acknowledgements

Z.S. and K.M. were supported by the ERC-CZ program (project LL2101) from the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (MEYS) and by the project Advanced Functional Nanorobots (reg. No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/15.003/0000444 financed by the EFRR). We thank Anton Lögl, Marc Anton Sachs, Gang Wang, and Alison Pfister for technical assistance. CrSBr atomic structure was depicted using VESTA software47.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.M. and Z.S. grew the bulk CrSBr crystals. D.I.M. and P.M. fabricated few-layer CrSBr sample for optical spectroscopy. D.I.M., S.S., and P.M. performed optical spectroscopy measurements. S.S. installed the cryostat system. P.M., D.I.M., and R.v.K. performed and interpreted AFM measurements. D.I.M., L.K., and B.U. analyzed the optical spectra. M.M.G. contributed to the discussion and theoretical explanation of observed phenomena. All authors discussed the results. B.U. suggested the experiments and supervised the project. D.I.M., P.M., and B.U. wrote the manuscript with input from all the authors. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Zdenek Sofer is editor of npj Quantum Materials/Excitons in 2D Materials Collection. Zdenek Sofer was not involved in the journal’s review or decisions related to this manuscript. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Markina, D.I., Mondal, P., Krelle, L. et al. Interplay of vibrational, electronic, and magnetic states in CrSBr. npj Quantum Mater. 11, 11 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-026-00850-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-026-00850-2