Abstract

Altered visual perception has been observed across all phases of psychotic illness, suggesting that perceptual measures might be useful in identifying people at clinical high risk for psychosis (CHR). In a preliminary study, we found that CHR participants reported perceiving more faces in binarized human portraits on the Mooney Faces Test (MFT). Here, we aimed to replicate these findings and extend understanding of underlying processes and clinical correlates of MFT performance in the Computerized Assessment of Psychosis Risk (CAPR) cohort: CHR (n = 159), help-seeking psychiatric controls (n = 130), and healthy controls (n = 86). The MFT was adapted to include three image conditions (upright, inverted, and scrambled), and included follow-up questions regarding the physical characteristics of the faces that participants reported perceiving, to verify accuracy of perception and assess response bias. The CHR group reported more faces than both control groups in the inverted and scrambled conditions. In addition, the CHR group was as accurate at judging the age and gender of faces as the other groups. Among CHR participants, increased reporting of faces in the inverted condition was significantly correlated with more severe positive symptoms and poorer role functioning. We discuss the findings in terms of multiple perspectives, including changes in perceptual sensitivity, predictive coding, and perceptual organization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The clinical high risk (CHR) model for psychosis seeks to reliably identify young individuals with symptoms that are known to be associated with increased vulnerability for psychotic illnesses. Improving the ability to predict the development of a psychotic disorder will increase the likelihood that CHR patients are appropriately screened and matched with services that aim to prevent the onset of psychosis and optimize functional outcomes and well-being. Current CHR identification approaches involve drawing data from well-validated structured interviews and testing. Despite its psychometric strengths, the standard approach has limited reach in three main respects. First, assessment by structured interviews is typically restricted to individuals with access to a clinician who is trained to administer the rigorous measure (i.e., they attended a 2-day training that typically costs over $2000 per clinic and passed the gold-standard reliability scoring exam), an option that is not yet available consistently worldwide or outside of university medical centers. Second, the most widely used structured interviews have limited specificity, with the CHR syndrome progressing to psychosis within 3 years for only 25% of individuals meeting criteria per these instruments1. Third, research on laboratory measures useful for CHR identification has thus far focused on trait measures of cognitive and psychophysiological impairment, instead of tasks that are known to be sensitive to the processes involved in progression from the at-risk state to a fully developed psychotic disorder2. To augment typical CHR identification approaches, the Computerized Assessment of Psychosis Risk (CAPR) network was formed, specifically to validate auxiliary, brief, computer-automated measures with previously demonstrated sensitivity to state changes and putative symptom mechanisms that are most likely predictive of an impending psychotic episode. Here, we report on data collected from the CAPR sample on a measure that may fit these criteria: the Mooney Faces Test (MFT).

The MFT3 involves presentation of a series of two-toned, human portrait images that vary in the degree to which a face can be perceived (See Fig. 1). On each trial, participants report whether they perceive a face. Optimal performance on the MFT requires perceptual organization of fragmented visual information into a holistic face representation and comparison of this representation with face templates stored in memory4,5,6. As such, reports of faces in inverted Mooney images are typically greatly reduced compared to when images are presented in their normal, upright orientation7,8. Schizophrenia patients have been found to identify fewer upright faces than non-psychotic psychiatric and healthy comparison groups on the MFT, and this reduced face identification is associated with the presence and severity of disorganization symptoms9,10. Moreover, it has been observed that performance on the MFT improves as disorganization symptoms respond to treatment9. Thus, the MFT appears to be a state-sensitive measure that could be useful in monitoring changes in disorganization in the at-risk mental state.

Our prior study was the first to administer the MFT to a CHR sample and to explore patterns and clinical correlates of task performance11. In contrast to MFT performance in people with established schizophrenia (where fewer faces are reported)9,10,12, CHR participants reported a significantly greater number of faces in the upright condition, and more faces at a trend level in the inverted condition, compared to healthy controls. These group differences were most pronounced among female participants, and among male CHR patients, greater reporting of faces in the upright face condition was associated with more severe perceptual abnormality symptoms (e.g., subclinical hallucinations). In general, however, this study had limited power to characterize group differences by sex and lacked the experimental design to test hypothesized mechanisms of observed increased face reports by CHR participants on the MFT.

The primary purpose of the present study was to determine if prior findings could be replicated in a new and larger CHR sample–that is, the significantly higher rates of face reporting in CHR individuals, sex differences in MFT performance, and correlations with positive symptoms. In addition, we sought to further understand the clinical significance of observed MFT performance in CHR by examining relationships with a larger set of symptom and functional measures and by testing hypothesized mechanisms of increased reporting of seeing faces in ambiguous stimuli. To this end, modifications to the MFT were made to examine the extent to which positive responses reflected the accurate detection of the face in the given image. Two limitations to the MFT as administered in our prior study11, and as it is usually administered, are that (1) it asks only about whether a face is perceived on each trial, but not about the details of the face perceived; thus, there is no way to verify that the participant actually perceived the face that was represented in the original, unaltered image; and (2) it lacks a true noise (i.e., no face) condition. Therefore, these test versions cannot verify that a positive face report reflects the perception of facial properties depicted in the image versus a positive response bias (i.e., the tendency to use a lower threshold for indicating whether a face is present). To address these two issues, we adapted the MFT procedure so that: 1) When a face was reported, follow-up questions were presented regarding the characteristics of the face (i.e., was it a child or adult; was it more traditionally masculine or feminine), and subject responses were compared to the age and gender features in the original image; and 2) a scrambled face image condition was included.

There are two possible, non-mutually exclusive explanations for increased face reports by CHR participants on the MFT that we wished to test: the heightened perceptual sensitivity and response bias hypotheses. Firstly, it is possible that the greater face reporting among CHR compared to controls could be ascribed at least in part to enhanced feedforward sensory processing that may either independently or in combination with top-down effects result in heightened perceptual sensitivity (including an increased tendency to perceive facial gestalts). This mechanism would align with one report of enhanced perceptual organization in people at risk for a psychotic disorder13, and with findings of increased contrast sensitivity in unmedicated first episode schizophrenia patients, which contrasts with the reduced contrast sensitivity and perceptual organization observed in patients with a longer illness duration14. Secondly, CHR participants in our prior study11 may have reported more faces than controls due to a greater tendency to report seeing a face when confronted with ambiguous stimuli, i.e., due to a positive response bias. Consistent with this possibility are results from prior research that found CHR participants were more likely than controls to report that they detected speech in degraded speech clips during the pre-training block (prior to being exposed to the clean speech templates)15. Signal detection theory (SDT) analyses pointed to a greater bias among CHR to report the detection of speech compared to controls. However, it is unclear whether this enhanced response bias in CHR was driven by perceptual or decisional factors, given that even the unintelligible speech clips used in this study were ‘speechlike’ stimuli; thus, it is possible that top-down effects (e.g., stronger priors for speech) among CHR participants resulted in the perception of speech even when the speech clips were fully unintelligible. As noted, such ambiguities in interpreting responses that are considered false alarms motivated us to adapt the design of the MFT to clarify the perceptual experiences of CHR subjects when they indicate perceiving a face.

This study reports on baseline data from the ongoing, multi-site CAPR project16. Three groups of participants are being recruited for CAPR: CHR, non-psychotic psychiatric help-seeking controls (HSC), and healthy controls (HC). Participants completed the adapted MFT that included upright, inverted, and scrambled stimuli, and follow-up questions to assess the accuracy of face perception on trials on which a face was reported. The rationale for including the HSC group was to provide a clinical comparison to CHR subjects. We are aware of no previous CHR study of visual perception that includes both a healthy and clinical control group, and thus, this study was expected to provide unique insights. To the extent that the heightened perceptual sensitivity hypothesis is correct, we expected the CHR group to report more faces in the upright and inverted conditions, but to have equivalent or better accuracy in describing the types of faces perceived, compared to the control groups. Alternatively, to the extent that the response bias hypothesis is correct, the CHR group relative to control groups was anticipated to report more faces in the scrambled condition (and potentially the inverted condition), but to be less accurate in their reporting of gender and age characteristics in the upright and inverted conditions. Per prior CHR and schizophrenia studies9,10,11, we expected to replicate a relationship between altered MFT performance and psychotic symptoms. Specifically, we hypothesized that more severe positive and disorganized symptoms would correlate with increased face reports in response to the most ambiguous stimuli (inverted and scrambled). Since we previously found that CHR females reported more faces than female controls, and the relationship between increased face reports and positive symptoms was more pronounced in CHR males versus females, we also set out to investigate potential sex effects in this larger sample.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This project was approved by institutional review boards across the seven sites of the CAPR project (Northwestern University, University of Maryland-Baltimore County, Yale University, University of Georgia, Temple University, and Emory University), and written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Recruitment used methods such as public transportation advertising, online advertisements, and mail-outs to community health care providers (for more details see methods paper on CAPR study)16. All CHR participants met criteria for a psychosis-risk syndrome according to the Structured Interview for Psychosis-Risk Syndromes (SIPS)17, as confirmed by trained interviewers. HSC participants were psychiatric help-seeking youth who, on initial screening, were thought to potentially meet CHR criteria, but were subsequently found not to meet full criteria based on the SIPS and were confirmed to meet non-psychotic, lifetime psychiatric diagnoses (see Supplemental Table for frequency of SCID-5 diagnostic categories). HC participants were defined by the absence of psychosis in a first-degree relative, past/current serious psychopathology, current use of psychotropic medication (e.g., antidepressants), and any history of antipsychotic medication use. Exclusion criteria were: (i) severe head injury, (ii) the presence of a neurological disorder, and (iii) lifetime history of a psychotic disorder, as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5, research version. The following participants (N = 375) from the CAPR study were included in analyses: CHR (n = 159), HSC (n = 130), and HC (n = 86).

Measures

Mooney Faces Test

For each trial of the MFT, a binarized (black-and-white) image was displayed on a computer screen (see Fig. 1). The images varied in physical qualities of gender and age of the face depicted, and on the degree of difficulty with regard to face detection. Forty-three of these images were of intact (but binarized) faces; each was presented twice, once in an upright orientation and once in an inverted orientation. Ten additional scrambled face images randomly drawn from a pre-existing collection8 were included to assess a possible bias to report faces when presented with stimuli in which there is no intact face. Each of these was shown in both an upright and inverted orientation, for a total of 20 scrambled trials. These scrambled stimuli consisted of facial features but without any face gestalts. Each subject was thus shown a total of 106 images across the upright, inverted, and scrambled conditions.

For every trial, participants were asked to respond by key press to indicate whether they perceived a face in the image or not, as per the original MFT instructions. Follow-up questions were asked on each trial for which a face response was given, specifically probing the participant as to whether the face image was of a child or adult, and whether it was more traditionally masculine or feminine. These responses were then compared to the ‘ground truth’ descriptions of the original images for the upright and inverted conditions. Of note, the original template images were unavailable for the scrambled stimuli. Accuracy scores were computed for the upright and inverted conditions by summing the number of trials on which the participant correctly identified both the gender and age group of the face depicted and dividing this sum by the total number of reported faces for the given condition.

Symptom assessment

The Prime Screen18 assessed self-reported presence and severity of attenuated psychotic symptoms, loss of insight, and symptom distress (items adapted by CAPR). Trained interviewers rated attenuated positive, negative, and disorganized symptoms were measured using the respective modules of the SIPS 5.6.

Life functioning

Functioning in the month prior to the study session was assessed by trained interviewers via the Global Functioning Scale: Social and Role (GFS/R) scales19. The GFS queried peer relationships, peer conflict, age-appropriate intimate relationships, and family involvement. The GFR assessed performance and amount of support needed in the individual’s primary role (e.g., student, employee).

Statistical analysis

Group differences in demographic characteristics were examined via One-Way ANOVA and cross-tabulation analyses. Between-condition and between-group differences in frequency of face reports on the MFT were assessed via linear contrast analyses20,21, which tested the degree to which variance in face reporting frequency for the upright, inverted, and scrambled conditions separately, was accounted for by the pattern of CHR > HSC = HC (contrast coefficients of 2, −1, −1, respectively). We also tested for a linear trend in the within-subject data with the expectation that face reporting, and age group/gender accuracy (for the upright and inverted), would be greatest in the upright condition, followed by the inverted condition, followed by the scrambled condition (contrast coefficients of 1, 0, -1). This analysis was done for the sample as a whole, followed by an examination of the interaction between group and the linear trend. Interactions with this between-condition trend were also examined for males and females separately, given previous observations of male participants reporting more faces on the MFT compared to female participants11. Spearman’s rho correlations examined relationships between clinical outcomes and MFT performance in the CHR group. We assigned a more conservative significance threshold for correlations (α = 0.01) as this study used a large sample size and was a replication and extension of our prior work. Clinical correlates of MFT performance via Spearman’s rho were also examined separately for male and female CHR participants.

Results

Participant characteristics

Demographic characteristics are provided in Table 1. To ensure sufficient cell count for group comparisons on demographic data by cross-tabulation analyses, categories were collapsed for race (White vs. non-White), participant education status (High school/Community college vs. Undergraduate vs. Graduate), and parental highest completed education (Less than high school vs. High school/College diploma vs. Post-secondary degree). Groups did not significantly differ by age, sex at birth, race, participant education, or parental education.

Task Manipulation and Attention

As expected, there was a significant within-subjects linear effect of reported faces across conditions, F(1,377) = 5407, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.94, whereby participants reported the most faces in the upright condition (M = 75.34%, SD = 17.33), followed by the inverted (M = 30.83%, SD = 20.70) and scrambled conditions (M = 7.29%, SD = 8.72). As per Mann-Whitney U tests, the CHR group did not significantly differ in percentage of missed trials relative to control groups (p's = 0.19 and 0.17, respectively), indicating that CHR participants were performing the task as instructed. These results also suggest that CHR participants did not notably differ from the HSC and HC groups in attention to the task at hand.

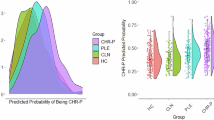

Between-group comparisons on the Mooney Faces Test

For every condition, a between-group linear contrast analysis of face reports was conducted, whereby the CHR group was hypothesized to report faces at a higher frequency than the HSC and HC groups (who were expected not to differ from each other). Results are displayed in Fig. 2. There was not a significant linear trend across groups in the upright face condition, F(1,372) = 0.21, p = 0.65, ηp2 = 0.001, potentially reflecting a ceiling effect. In the inverted condition, however, the linear trend was confirmed: The CHR group reported significantly more faces than the HSC and HC groups, F(1,372) = 11.61, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.030. Similarly, there was greater reporting of faces by the CHR group in the scrambled condition, compared to the HSC and HC groups, F(1,372) = 8.24, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.022. Follow-up pairwise comparisons confirmed that the two control groups did not differ from each other in their rates of inverted and scrambled face reports, F(1,372) < 0.001, p = 0.99 and F(1,372) = 0.92, p = 0.34, respectively.

Bar graphs display linear contrast analysis models and effect sizes (partial η2) testing CHR > HSC = HC for percentage of faces reported within the a upright, b inverted, and c scrambled conditions of the Mooney Faces Test. Groups: CHR Clinical High Risk, HSC Help-seeking controls, HC Healthy controls. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Of note, the CHR group did not differ significantly from the control groups in accurately characterizing the gender and age group in images on which a face was reported in either the upright or inverted condition (upright: CHR M = 92.43%, SD = 8.07, HSC M = 92.47%, SD = 4.42, HC M = 92.68%, SD = 4.30, F[2,362] = 0.04, p = 0.96, η2 < 0.001; inverted: CHR: M = 83.23%, SD = 13.41, HSC M = 84.34%, SD = 11.06, HC M = 80.93%, SD = 12.24, F[2,364] = 1.89, p = 0.15, η2 = 0.01). These accuracy findings, within the context of greater face reporting overall, suggest that CHR participants were likely not impaired in their face detection abilities.

We conducted a series of follow-up two-way ANOVAs to assess group by sex interaction differences in frequency of reporting faces within each of the three MFT conditions. In both the upright and scrambled conditions, the main effect of sex was not significant, indicating that collapsed across groups, male and female participants did not significantly differ in the number of faces reported (upright: F[1,358] = 0.30, p = .58, ηp2 = 0.001; scrambled: F[1,358] = 0.12, p = 0.73, ηp2 < 0.001). Non-significant sex by group interactions for both of these conditions indicated that the pattern of face responses across males and females to the upright and scrambled stimuli was similar across the three groups (upright: F[2,358] = 1.52, p = 0.22, ηp2 = 0.008; scrambled: F[2,358] = 0.44, p = 0.64, ηp2 = 0.002). In the inverted condition, however, male participants, collapsed across groups, reported faces on 6.35% more trials than female participants, representing a significant main effect of sex, F(1,358) = 9.86, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.027. The sex by group interaction for inverted face reports was at a trend level, F(2,358) = 2.88, p = 0.06, ηp2 = 0.016. Exploratory follow-up of this trend-level interaction detected a significant simple effect of sex within the HC group, F(1,358) = 11.62, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03 (but not in CHR and HSC groups), whereby male HC participants (n = 27) reported faces on 16.27% more trials than female HC participants (n = 58) in the inverted condition. See Supplementary Information for analyses exploring sex effects in MFT reporting patterns using a linear contrast model approach.

Clinical correlates of MFT performance

Correlations between MFT performance and clinical variables among CHR are displayed in Table 2. The percentage of faces reported in the upright condition did not significantly correlate with SIPS overall positive, negative, or disorganization symptom scores; GFR or GFS; or Prime screen scores. While the tendency to report more faces in the upright condition correlated significantly with more severe Prime screen distress scores (i.e., with more severe distress from positive symptoms), the effect is small and likely not clinically meaningful. Of note, these results may reflect a ceiling effect and range restriction in the upright condition scores. Reporting more faces in the inverted condition was significantly correlated with greater Prime positive symptom severity and distress. In addition, more frequent face reports in the inverted condition were significantly correlated with lower role functioning. There were no significant relationships between reported faces in the scrambled condition and the clinical variables examined.

The significant clinical correlates of MFT performance detected in the total CHR sample did not survive when we examined these correlations in male CHR participants only and used our assigned significance threshold (α < 0.01). We observed similar trends in symptom correlates among male CHR participants that were of larger effect than those observed in the total sample, however: face reports in the upright condition were positively correlated with Prime screen distress scores, rs(45) = 0.33, p = 0.03, and face reports in the inverted condition were positively related to Prime positive symptom severity, rs(45) = 0.31, p = 0.04, and distress, rs(45) = 0.32, p = 0.03. Amongst all clinical correlates of MFT performance examined, only two trend-level relationships emerged in female CHR participants: number of face reports in the inverted condition was positively associated with Prime positive symptom severity, rs(105) = 0.20, p = 0.04, and inversely associated with role functioning, rs(104) = −0.23, p = 0.02.

We explored non-parametric correlations between individual positive symptoms and MFT performance given our previous findings that, in male CHR participants only11, more frequent face reports in the upright condition were significantly associated with more severe SIPS perceptual abnormalities/hallucinations, but not other positive symptoms. The individual symptom domains evaluated were perceptual abnormalities/hallucinations (SIPS P4 clinician-rated item and Prime self-report items), Prime unusual thoughts, Prime suspiciousness, and Prime grandiosity. In male CHR participants, more frequent face reports in both the upright and inverted conditions were significantly associated with more severe unusual thoughts, rs(45) = 0.30, p = 0.04, and rs(45) = 0.31, p = 0.03, respectively. More frequent face reports in the inverted condition was also significantly correlated with higher suspiciousness, rs(45) = 0.34, p = 0.02. Contrary to findings from our prior study11, neither clinician-rated nor self-reported perceptual abnormalities/hallucinations were significantly correlated with faces reported in upright, inverted, or scrambled conditions (p’s > 0.05). No significant correlations were detected in female CHR participants (p’s > 0.05).

Discussion

This study expanded on the evidence base supporting MFT performance as a biobehavioral measure that is useful for characterizing the CHR mental state. We found that CHR participants reported more faces relative to HSC and HC groups in the most ambiguous images of the MFT (inverted and scrambled). Unlike in our earlier study, there was no group difference for upright images, but there appeared to be a ceiling effect in the upright condition in the present study. Despite having accessed larger CHR male and female sub-samples than our prior study11, we did not replicate our previously reported sex differences in MFT face reports within the CHR group and instead found that male participants across all groups reported more inverted faces than female participants. We also did not replicate our prior finding of a relationship between increased face reports in the upright condition and perceptual abnormalities/hallucinations only among male CHR participants. Rather, we found that in the total CHR sample, more frequent face reporting in the inverted condition was correlated with more severe PRIME positive symptoms and lower role functioning, and that among male CHR participants, more face reports in both the upright and inverted conditions were associated with more severe unusual thoughts, and more face reports in the inverted condition were correlated with higher suspiciousness.

The adaptations we made to the MFT allowed us to examine several potential mechanisms involved in the effects we observed. CHR participants reported seeing more faces in the inverted condition than both clinical and healthy controls, and were equivalent to control groups in accurately classifying these face images according to age group and gender. This performance pattern suggests that CHR participants’ task behavior was reflecting perceptual effects rather than a response bias to report seeing a face when unsure. Thus, we consider it more likely that the increase in face reports among CHR participants in the inverted condition was driven by heightened perceptual sensitivity. As noted above, heightened perceptual sensitivity is consistent with enhanced contrast sensitivity in unmedicated first episode psychosis patients14,22, and with increased perceptual organization in schizotypal patients, who were potentially experiencing a psychosis prodrome13. The tendency to report more faces in the inverted MFT condition, presumably due to heightened perceptual sensitivity, may be more characteristic of the psychosis-risk state than of non-psychotic psychopathology, given that CHR participants but not clinical or healthy controls, demonstrated a higher level of face reporting to in this condition.

It is more difficult to account for increased face reports among CHR subjects in the scrambled condition. If one conceptualizes the scrambled condition as pure noise stimuli, then this finding would suggest a form of response bias involving an increased tendency to give a positive response in the absence of a signal. This form of response bias has been found in individuals with putative traits of psychosis-proneness (“schizotypy”) and may be a manifestation of apophenia, the frequent perception of connections or personal/social sources of meaning in unrelated, random events. For example, schizotypal participants on various computerized tasks were more likely than healthy controls to infer mental states in randomly moving shapes (versus shapes showing goal-directed, anthropomorphic movements), to report affectively meaningful speech in white noise, and to attribute emotional valence in non-emotional face stimuli23,24,25. Across studies, task performance indicative of apophenia was uniquely related to the severity of positive schizotypy traits (i.e., delusions, paranoia). At the same time, since some of the scrambled images from the adapted MFT used in the present study contain recognizable face parts (even though no facial Gestalt is present), it is possible that the CHR participants were more likely than the other groups to assume the presence of a face and then report seeing a face based on the observation of individual face parts alone. This tendency would also reflect a form of response bias, although one based on the detection of partial evidence for the signal and a greater weighting of this partial evidence during decision making compared to the other groups. Further clarification of this possibility in future studies could be aided by probing participants regarding their strategy after the task (e.g., were they reporting faces only when perceiving an entire face or also when detecting only face parts) and/or administering a version of the task that specifically directs participants to respond yes only when they perceive an entire face.

The finding of heightened face reporting on the MFT among CHR participants and its relationship to more severe positive symptoms and lower role functioning struck us as counterintuitive, especially when it stood in contrast to findings among chronic schizophrenia patients, where under-reporting of faces has been found, and is related to level of disorganization9,10. The visual system during the CHR stage is characterized by excessive excitation and a general increase in relative inhibition over time26. Excessive excitation and synchrony at the CHR stage could account for an increased ability to integrate sensory information and construct face representations within noisy stimuli. Taken to an extreme, however, this would lead to illusory perception of faces in non-face stimuli (e.g., pareidolia)27,28. While heightened ability to detect meaning in otherwise ambiguous stimuli could improve performance on the MFT and other laboratory-based measures, it would typically be maladaptive in real-world scenarios that are laden with far more nuanced and dynamic visual stimuli. Processing errors can result in dysfunctional interactions within daily life contexts, which may account for the relationships we found between increased face reporting in inverted and scrambled stimuli and more severe positive symptoms and role dysfunction in the CHR participants.

Study results should be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. Firstly, although findings were based on the largest CHR sample of MFT performance data thus far, analyses were performed on baseline data of an ongoing longitudinal study. The capacity for the MFT to index changes in symptoms and functioning over time and predict transition to a full psychotic syndrome cannot be evaluated until longitudinal data on the study sample becomes available. Secondly, because inclusion of a scrambled condition in the MFT paradigm was largely exploratory, we included fewer trials in the scrambled condition compared to the upright and inverted conditions. This may have limited the scope of significant clinical correlates detected for face reports in the scrambled condition. We recommend that future research using the MFT in CHR should equalize the number of trials across conditions. Thirdly, despite the adaptations we made to the MFT (i.e., including a scrambled image condition and follow-up questions about age and gender characteristics of reported faces), the paradigm as it stands makes it challenging to fully rule out the possibility of, or quantify the extent of, a bias to respond positively, especially on trials such as those in the scrambled condition. That is, to what extent are decisional versus perceptual contributions driving task performance? Future investigations of MFT performance in CHR subjects might benefit from including biological markers of face perception (e.g., fMRI activation in the fusiform face area, which is increased in response to upright relative to inverted faces7,29; the closure negativity ERP waveform that emerges when a Gestalt is perceived30; and gamma synchrony, which is increased during perception of upright relative to inverted faces5), to assist with corroborating face reports. Fourthly, the inverted and scrambled images did not qualify as a set of pure noise stimuli, as they still contained face elements that participants could detect when accumulating evidence prior to giving their responses. In the original MFT paper3, 44% of the inverted images were recognized as faces by a subset of participants (range = 11% to 89% of subjects per inverted stimulus). A future iteration of the MFT may benefit from a condition of scrambled images of objects that do not contain any components of human faces (e.g., fruits that are not face-shaped), to assist with perception vs. bias determinations using signal detection analysis. Fifthly, while we more than doubled the sample size for male and female CHR subjects compared to our first study, we did not replicate our prior findings of sex-based differences in MFT face reporting, and this may be due to insufficient power for these analyses or imbalanced subgroup size (47 Male: 107 Female). The question of sex differences could be better addressed in large samples with more equivalent subgroup sizes. Lastly, the pattern of face reporting in the upright condition suggested that a ceiling effect might be operative there, and this may have hindered detection of between-group differences. A future study could avoid ceiling effects and better differentiate group performance by generating a larger set of upright images and applying a staircase procedure to the MFT such that all subjects are roughly equivalent in accuracy, but different on the stimulus difficulty levels associated with threshold accuracy.

In summary, this study replicated a prior report of increased face reporting on the MFT among CHR subjects and observed the effect in both the inverted and scrambled face conditions. Our findings that CHR subjects were as accurate as the control groups in detecting upright faces, and as accurate as the control groups in identifying the gender and age group of reported faces in the upright and inverted conditions strongly suggest that this increased face reporting in CHR was not simply an effect of guessing or due to a bias to report a face when unsure. The observed performance pattern among CHR individuals in the inverted condition may reflect heightened perceptual sensitivity. Heightened inverted face reporting in the CHR group was associated with more severe positive symptoms, positive symptom distress, and impairment in role functioning, suggesting that the altered visual information processing strategy in CHR participants is maladaptive in general, and may be associated with the development of symptoms such as delusions, where meaning is inferred where none exists, and/or hallucinations, where percepts are generated in the absence of corresponding sensory input. Future studies that further refine the MFT to capture more information about how subjects are making their decisions, and that better allow for SDT analyses, may help further characterize the mechanisms involved in altered MFT performance among CHR patients. In addition, longitudinal studies that examine change in MFT performance over time relative to changes in clinical and functional status over time in CHR patients could determine the utility of the MFT for inclusion in future psychosis risk calculators.

Data availability

Data for the ongoing Computerized Assessment for Psychosis Risk multi-site study is routinely uploaded to the National Institute of Mental Health Data Archive at https://nda.nih.gov. The dataset with the sample and select variables used in the present study analyses are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used in this study to present the adapted Mooney Faces Test and to score the individual subject raw data files are available from GitHub, https://github.com/belieflab/mooneyFaces/blob/main/README.md.

References

Salazar de Pablo, G. et al. Probability of transition to psychosis in individuals at clinical high risk: an updated meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 78, 970–978 (2021).

Gold, J. M. et al. Enhancing psychosis risk prediction through computational cognitive neuroscience. Schizophr. Bull. 46, 1346–1352 (2020).

Mooney, C. M. Age in the development of closure ability in children. Can. J. Psychol. Rev. Can. Psychol. 11, 219–226 (1957).

Canas-Bajo, T. & Whitney, D. Stimulus-specific individual differences in holistic perception of Mooney Faces. Front. Psychol. 11, 585921 (2020).

Rodriguez, E. et al. Perception’s shadow: long-distance synchronization of human brain activity. Nature 397, 430–433 (1999).

van Loon, A. M. et al. NMDA receptor Antagonist Ketamine distorts object recognition by reducing feedback to early visual cortex. Cereb. Cortex 26, 1986–1996 (2016).

Kanwisher, N., Tong, F. & Nakayama, K. The effect of face inversion on the human fusiform face area. Cognition 68, B1–B11 (1998).

Schwiedrzik, C. M., Melloni, L. & Schurger, A. Mooney face stimuli for visual perception research. PLOS ONE 13, e0200106 (2018).

Uhlhaas, P. J., Phillips, W. A. & Silverstein, S. M. The course and clinical correlates of dysfunctions in visual perceptual organization in schizophrenia during the remission of psychotic symptoms. Schizophr. Res. 75, 183–192 (2005).

Uhlhaas, P. J., Phillips, W. A., Mitchell, G. & Silverstein, S. M. Perceptual grouping in disorganized schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 145, 105–117 (2006).

Silverstein, S. M. et al. Increased face detection responses on the Mooney faces test in people at clinical high risk for psychosis. Npj Schizophr. 7, 1–7 (2021).

Buchanan, R. W. et al. Neuropsychological impairments in deficit vs nondeficit forms of schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 51, 804–811 (1994).

Parnas, J. et al. Visual binding abilities in the initial and advanced stages of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 103, 171–180 (2001).

Silverstein, S. M. Visual Perception Disturbances in Schizophrenia: A Unified Model. in The Neuropsychopathology of Schizophrenia: Molecules, Brain Systems, Motivation, and Cognition (eds. Li, M. & Spaulding, W. D.) 77–132 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-30596-7_4.

Kafadar, E. et al. Modeling perception and behavior in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis: Support for the predictive processing framework. Schizophr. Res. 226, 167–175 (2020).

Mittal, V. A. et al. Computerized assessment of psychosis risk. J. Psychiatry Brain Sci. 6, e210011 (2021).

McGlashan, T., Walsh, B. & Woods, S. The Psychosis-Risk Syndrome: Handbook for Diagnosis and Follow-Up. (Oxford University Press, USA, 2010).

Kline, E. et al. Psychosis risk screening in youth: A validation study of three self-report measures of attenuated psychosis symptoms. Schizophr. Res. 141, 72–77 (2012).

Cornblatt, B. A. et al. Preliminary findings for two new measures of social and role functioning in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 33, 688–702 (2007).

Rosenthal, R., Rosnow, R. L. Contrast Analysis: Focused Comparisons in the Analysis of Variance. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1985.

Rosnow, R. L. & Rosenthal, R. Contrasts and correlations in theory assessment. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 27, 59–66 (2002).

Kiss, I., Fábián, Á, Benedek, G. & Kéri, S. When doors of perception open: Visual contrast sensitivity in never-medicated, first-episode schizophrenia. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 119, 586–593 (2010).

Blain, S. D., Longenecker, J. M., Grazioplene, R. G., Klimes-Dougan, B. & DeYoung, C. G. Apophenia as the disposition to false positives: A unifying framework for openness and psychoticism. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 129, 279–292 (2020).

Fyfe, S., Williams, C., Mason, O. J. & Pickup, G. J. Apophenia, theory of mind and schizotypy: Perceiving meaning and intentionality in randomness. Cortex 44, 1316–1325 (2008).

Galdos, M. et al. Affectively salient meaning in random noise: a task sensitive to psychosis liability. Schizophr. Bull. 37, 1179–1186 (2011).

Grent-’t-Jong, T. et al. Resting-state gamma-band power alterations in schizophrenia reveal E/I-balance abnormalities across illness-stages. eLife 7, e37799 (2018).

Abo Hamza, E. G., Kéri, S., Csigó, K., Bedewy, D. & Moustafa, A. A. Pareidolia in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 12, 746734 (2021).

Barton, L. My friend was a popular, promising artist - how did he end up on the streets of Portland, addicted and dangerous? The Guardian (2024).

Rossion, B., Dricot, L., Goebel, R. & Busigny, T. Holistic face categorization in higher order visual areas of the normal and prosopagnosic brain: toward a non-hierarchical view of face perception. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 4, 225 (2011).

Sehatpour, P., Molholm, S., Javitt, D. C. & Foxe, J. J. Spatiotemporal dynamics of human object recognition processing: An integrated high-density electrical mapping and functional imaging study of “closure” processes. NeuroImage 29, 605–618 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the patients and their families. The work reported in this paper was supported by the New York Fund for Innovation in Research and Scientific Talent (NYFIRST) (Silverstein), and the following National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants: R01 MH120090 (Gold), R01 MH112613 (Ellman), R01 MH120091 (Ellman), R01 MH120092 (Strauss), R01 MH116039 (Strauss/Mittal), R21 MH119438 (Strauss), R01 MH112545 (Mittal), R01 MH1120088 (Mittal), U01 MH081988 (Walker), R01 MH120090 (Waltz), R01 MH112612 (Schiffman), and R01MH120089 (Corlett/Woods).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.T. and S.M.S. have full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Present study concept and design: S.M.S. Acquisition of data: All authors. Writing of scoring program for perceptual task: T.T., J.K., S.M.S., B.R. Statistical analysis and interpretation of data: T.T., S.M.S., B.P.K., J.L.T. First draft of the manuscript: T.T., S.M.S. Subsequent drafts of the manuscript: All authors. Obtained funding: J.A.W., J.M.G., J.S., L.M.E., E.F.W., G.P.S., V.A.M., R.E.Z., P.R.C., A.R.P., S.W.W., S.M.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tran, T., Keane, B.P., Thompson, J.L. et al. Increased face perception in individuals at clinical high-risk for psychosis: mechanisms, sex differences, and clinical correlates. Schizophr 11, 74 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00624-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00624-y

This article is cited by

-

Predictive processing accounts of psychosis: bottom-up or top-down disruptions

Nature Mental Health (2026)

-

Robust averaging of emotional faces and its association with psychotic-like experiences and social connection

Scientific Reports (2026)