Abstract

Mental illnesses often manifest through behavioral changes, with speech serving as a key medium for expressing thoughts and emotions. The use of computational linguistics on speech data in mental illnesses is a promising approach to uncover objective biomarkers for the early detection of mental illnesses. This study analyzed speech transcripts from 80 youths at ultra-high risk of psychosis (UHR) and 329 healthy controls, examining text features such as sentiment variability, cohesion, lexical sophistication, morphology, syntactic sophistication, and lexical diversity. Factor analysis revealed five key linguistic themes: Sentiment Intensity and Variability, Linguistic Register Alignment, Phonographic Uniqueness and Recognizability, Morphological Complexity and Imageability, and Lexical Richness and Typicalness. Regression analysis indicated UHR speech is characterized by diminished sentiment variability (β = –0.07), deviation from linguistic registers (β = –0.16), fewer phonographic neighbors (β = –0.11), lower morphological complexity (β = –0.36), and more predictable lexical structures (β = 0.05). Optimized machine learning (ML) models trained on Boruta-selected features achieved a mean AUC of 0.70. Our findings highlight the potential of sentiment and linguistic analyses in speech for training ML models to aid in early detection and monitoring of mental health conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rising prevalence of mental health issues, including depression, anxiety and psychosis, amongst youths worldwide is a pressing concern1,2,3,4. If left untreated, mental health conditions can cause significant impairments in social and occupational functioning. Unfortunately, youth mental health conditions usually remain undetected due to the lack of surveillance mechanisms outside clinical environments, while social stigma and lack of self-awareness may prevent youths from actively seeking help5. Good treatment outcomes are contingent upon early detection. Hence, novel approaches for identifying and engaging high-risk youths in non-clinical environments are needed.

Text is a readily obtainable data modality. It can be retrieved from journals, social media, conversations, and interviews. Texts reflect people’s innermost thoughts and emotions, providing a window into their mental states. For example, it is well-documented that individuals with formal thought disorder are characterized by derailment, tangentiality, and incoherence from the text patterns mined from their speech6. As unstructured data, meaningful features can be mined from texts, which may have immense predictive value when combined with powerful statistical and machine learning (ML) approaches7. The integration of text features with ML to predict early onset of mental health issues is underexplored in current literature, possibly due to challenges in recruitment and obtaining consistent text data from individuals, alongside technical challenges in feature mining and ML model training.

In this study, we developed ML models trained on speech-derived text features to detect youths at ultra-high-risk of psychosis (UHR). Youths at UHR experience subthreshold psychotic symptoms and do not meet the criteria for a psychotic episode, but are at an increased and imminent risk of developing psychosis8. Early detection of youths at UHR is crucial for implementing timely interventions and preventing conversion. In related studies, ML models were trained on cohesion measures and part-of-speech (POS) tags to detect UHR9 and predict conversion10,11,12. Cohesion refers to the presence or absence of textual cues that facilitate the connection of ideas within a text13, while POS tagging refers to the automatic tagging of words in a sentence based on their grammatical function14. Cohesion measures include manually rated scores10 (e.g., referential cohesion, conjunction, reference patterns) and computationally generated features (e.g., Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA), Sentence Bidirectional Encoder Representation from Text)9,11,12. Reduced semantic coherence and higher variance in semantic coherence have been reported to predict conversion12, while sentence-level semantic similarity features have been found to accurately differentiate youths at UHR from healthy controls9.

While cohesion measures have potential for incorporation into predictive ML models, there are many other aspects of natural language processing (NLP), including sentiment analysis (SA), and other linguistic domains, which have not been evaluated and studied for its predictive potential in detecting UHR. To address this gap, we will train our models on a variety of sentiment and linguistic features to detect UHR coupled with explainable AI approaches for improved interpretation. Besides cohesion, we will examine five other dimensions: (1) sentiment variability, (2) lexical sophistication, (3) morphology, (4) syntactic sophistication and complexity, and (5) lexical diversity. Sentiment variability refers to fluctuations in sentiment scores within a text at the local (sentence) level, and is measured using Emotional Variance Analysis (EVA)15. EVA expands on traditional SA approaches, which only reflect sentiment at the global (full text) level. Lexical sophistication refers to the diversity and/or relative difficulty of lexical items in a text relative to those in reference corpora16. Morphology has multiple definitions. In linguistics, morphology refers to the grammatical processes (e.g., inflections, derivations) manipulated at the word level. According to Crossley et al., morphology could also refer to the interplay between word structure and phonology, syntax, and semantics17. As our morphology features were extracted using methods from Crossley et al., we based our understanding of morphology on their definition. Syntactic sophistication refers to the relative complexity of learning syntactic structures, while syntactic complexity refers to the absolute complexity of syntax18. Lexical diversity refers to the range of unique words used in a text19.

By training ML models on an extensive set of sentiment and linguistic features coupled with explainable AI methods, we aim to identify a meaningful and informative set of speech-derived text features for UHR detection. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the value of speech-derived sentiment and linguistic features in detecting UHR.

Methods

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the National Healthcare Group’s Domain Specific Review Board (NHG DSRB Ref: 2009/00167). Informed consent was obtained from participants aged 21 and above, while consent from a legal representative was obtained for participants below the age of 21. Identifiable and personal information were removed before analysis.

Data set

Transcribed texts were obtained from the High-risk Social Challenge (HiSoC) task, a component of the Longitudinal Youth At-Risk Study (LYRIKS). LYRIKS is a 2-year prospective observational study designed to identify clinical, social, and biological risk factors associated with youths at UHR aged 14–2920. The Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS) was used to categorize participants as UHR positive or UHR negative21. None of the UHR positive participants were taking antipsychotics or mood stabilizers. HiSoC assesses social functioning based on social-interpersonal skills, affect, and odd behavior and language22. In HiSoC, participants took part in a simulated audition for the “Most Interesting Person” award and were given 10 seconds to prepare and 45 seconds to respond. All auditions were conducted in English. Video recordings were manually transcribed using the same transcription key to ensure all transcripts were in the same format. Identifiable and personal information were removed from the transcripts. During pre-processing, non-punctuation symbols (e.g., parentheses, brackets, slashes) were removed. Stop words (e.g., and, the, a) and filler phrases (e.g., well, you know, I mean) were not removed as they were relevant to our extracted features. Our transcribed dataset includes 429 participants (80 UHR positive and 349 UHR negative).

Overall workflow

Our workflow is summarized in Fig. 1. First, we manually transcribed the HiSoC video recordings (see Data Set above). Next, feature extraction techniques were applied to the HiSoC transcripts to generate six sentiment and linguistic feature sets (see Feature Extraction below). Subsequently, we employed and tuned the Boruta algorithm to shortlist important features for UHR detection. Finally, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to uncover underlying themes amongst shortlisted features, while regression analysis was conducted to examine associations between shortlisted features and UHR.

All HiSoC (High-risk Social Challenge) video recordings were manually transcribed. Feature extraction tools were applied to the HiSoC transcripts to generate text feature sets. The Boruta algorithm was tuned and used to select top features. Factor and regression analyses were performed on top features to identify thematic factors and examine feature associations with UHR, respectively.

Feature extraction

We performed feature extraction on the transcripts using six tools selected based on the criteria of code accessibility, comprehensive documentation and prior validation in published studies. The list of selected tools include: (1) EVA15, (2) Tool for the Automatic Analysis of Cohesion (TAACO; version 2.0.4)23, (3) Tool for the Automatic Analysis of Lexical Sophistication (TAALES; version 2.2)24, (4) Tool for the Automatic Measurement of Morphological Information (TAMMI; version 2.0)25, (5) Tool for the Automatic Analysis of Syntactic Sophistication and Complexity (TAASSC; 1.3.8)18, and (6) Tool for the Automatic Analysis of Lexical Diversity (TAALED; version 1.4.1)26 (see Table 1 for descriptions).

Feature selection

Boruta

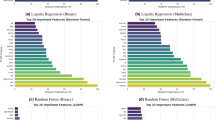

Feature selection reduces the number of features needed for ML model training, enhancing model interpretability and explainability. We selected Boruta as it is a top performing method compatible with small datasets27. Boruta relies on Random Forest Classifiers (RFCs), ensemble learners that rely on aggregating the outputs of many decision trees, to compute feature importance scores using mean decrease in Gini impurity (MDI) scores28. To enhance feature discrimination by the RFC, shadow features, which are randomly generated constructs, are appended to the data. A Z score is then calculated for each feature importance score (for a given real feature) against the shadow features. Additionally, an accompanying p value can be inferred based on the 2-tailed test to determine statistical significance (p < 0.05). Real features that do not meet the p value cutoff are discarded. This procedure is iterated until convergence to ensure that only the most informative features remain.

Model tuning and implementation

RFC and Boruta were implemented using the scikitlearn (version 1.5.1) and boruta_py (version 0.4.3) libraries in Python (version 3.12.4; Python Software Foundation), respectively. We set the maximum depth of our RFCs to 3 to prevent overfitting and used balanced class weights to account for sample imbalance between the UHR positive and negative groups. For Boruta, we used 1000 trees per RFC and set the maximum number of iterations to 100. Boruta’s percentile parameter, \(p\), has a default value of 100 and may be too stringent. To balance between a strict selection criterion and incurring false positives, we tuned \(p\) using a grid search strategy, where \(p\in\) {75, 76, …, 100}.

For each \(p\), we iterated Boruta on 30 RFCs. Each RFC was evaluated using leave-one-out cross-validation. The optimal \(p\) was determined based on the highest achieved mean Area Under the receiver-operating characteristic Curve (AUC). We ran Boruta separately using the optimal \(p\) on 100 RFCs to identify a subset of stable features for subsequent analyses. Features were deemed important if they were selected in at least 95 out of 100 RFCs. To minimize feature redundancies, we computed pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients (\(r\)) for the stable features selected by Boruta. For feature pairs with high correlation (\({|r|}\)>0.75)29, one feature from each pair was randomly removed.

Statistical analysis

To identify common themes enriched amongst shortlisted features, we performed EFA using the factor_analyzer (version 0.5.1) library in Python (version 3.12.4; Python Software Foundation). EFA generates a set of factors to explain common information shared amongst many features. Principal axis factoring was used for factor extraction to account for unique variance within each feature. Kaiser’s rule was used to determine the total number of factors. Promax rotation was used to deal with correlations amongst underlying factors. A feature is deemed to contribute strongly to a factor if its absolute loading score is at least 0.50. This criterion prevents cross-loadings. Features that did not load highly on any factor were removed. We named each factor based on the underlying theme of its corresponding features.

We built a logistic regression (LR) model using shortlisted features as the predictor variables and CAARMS classification (i.e., UHR positive or negative) as the response variable to examine feature associations with UHR status. To adjust for potential confounders, we included demographic variables that were associated with UHR status. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to assess group differences in age, while chi-squared tests were used for gender, ethnicity, and highest education level. P values were corrected using Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Statistical tests and the LR model were implemented using SciPy (version 1.14.1) and statsmodels (version 0.14.4) libraries, respectively, in Python (version 3.12.4; Python Software Foundation).

Results

Demographic information

Participant demographics are shown in Table 2. As there were no significant differences in age, gender, ethnicity, and highest education level between UHR positive and negative groups, we did not include these variables in our models.

Feature selection

The RFC trained on \(p\) = 96 achieved the highest mean AUC of 0.696 (Supplementary Fig. 1). The class-specific performance metrics are shown in Supplementary Table 1. At \(p\) = 96, amongst the 1154 extracted features, 29 features from EVA, TAALES, TAMMI, and TAACO were marked as important in least 95 out of 100 RFCs. 22 out of 29 features were highly correlated with at least one other feature (\({|r|}\)>0.75) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Highly correlated features were filtered according to the procedures outlined in the Methods section (see Model Tuning and Implementation). After filtering highly correlated features, 15 features were shortlisted for EFA (see Table 3 for descriptions). Most enriched features originated from TAALES (8/15), while the rest were from EVA (4/15), TAMMI (2/15), and TAACO (1/15).

Exploratory factor analysis

Performing EFA with Kaiser’s rule, we identified 5 factors. The factor loading scores of each shortlisted feature are shown in Supplementary Table 2. The sole TAACO feature, trigram_lemma_ttr, was removed from analysis as it did not load highly on any factor (loading scores were less than 0.50). For factor naming, we first examined the sentiment and linguistic properties captured by the loaded features in each factor. We then assigned labels that best describe the collective function of the loaded features.

The first factor comprises four EVA features: FS_MAXHI, FS_SPP, FS_AVG, and FS_SVAR. These features represent the maximum sentiment of the longest happy island, sum of positive peak values, average sentiment score of all sentences, and the variance of the longest sad island15. Collectively, they capture the degree of positive sentiment intensity and local negative sentiment variability in a transcript. Therefore, we named this factor Sentiment Intensity and Variability.

The second factor is made up of three TAALES features: COCA_Fiction_Trigram_Range, COCA_spoken_Trigram_Range, and COCA_magazine_tri_prop_10k. These features represent the average trigram range with reference to COCA’s fiction register, spoken register, and the proportion of trigrams that are among the top 10,000 frequent trigrams in COCA’s magazine register24. While the fiction and magazine registers have less relevance than the spoken register, we included features from all registers in our analysis to examine the alignment between UHR speech patterns and various normative linguistic styles. The trigram range and proportion scores could serve as alignment measures, where higher values indicate a greater similarity in the trigrams used between the transcripts and linguistic registers. Overall, this factor measures the alignment between the transcripts and various linguistic registers. Thus, we labeled it as Linguistic Register Alignment.

The third factor consists of two TAALES features: WN_SD_CW and OG_N. WN_SD_CW measures the average SD of content word naming latency24. The SD of a word’s naming latency may reflect its recognizability. Words that are not immediately recognizable could result in greater variation in the time taken to read them aloud, translating to higher WN_SD_CW values. OG_N refers to the average number of phonographic neighbors24. OG_N could serve as a measure of phonographic uniqueness, where higher values correspond to the presence of words with more phonographic neighbors in the language system. Collectively, OG_N and WN_SD_CW measure the phonographic uniqueness and recognizability within the transcripts. Hence, we named this factor Phonographic Uniqueness and Recognizability.

The fourth factor is represented by one TAALES feature, MRC_Imageability_CW, and two TAMMI features, Inflected_Tokens and suffix_freq_per_cw. MRC_Imageability_CW refers to the average imageability score of content words24. Imageability is a psycholinguistic variable that measures the ease in which a word evokes mental images30. Inflected_Tokens measures the proportion of content words with inflectional morphology in a text25, reflecting its morphological complexity. Suffix_freq_per_cw also reflects morphological complexity of the transcript. Higher values indicate the presence of suffixes that are more commonly used in the language system, pointing towards lower morphological complexity. Therefore, we labeled this factor as Morphological Complexity and Imageability.

The fifth factor is influenced by two TAALES features: LD_Mean_Accuracy_CW and COCA_spoken_tri_2_MI. LD_Mean_Accuracy_CW refers to the average lexical decision accuracy of content words24. The decision accuracy of a word may reflect its typicalness. Words that are typically used or read are more likely to be correctly identified, resulting in higher LD_Mean_Accuracy_CW values. COCA_spoken_tri_2_MI refers to the mean MI score of trigrams24. MI scores indicate the degree of lexical richness of the transcript, as higher scores point to the use of trigrams with more common compositions. Therefore, we named this factor Lexical Richness and Typicalness.

Regression analysis

We examined associations between shortlisted features and UHR by analyzing the polarity of feature coefficients of the LR model (Fig. 2). Most features were negatively associated with UHR (11/14). Only WN_SD_CW (average SD of content word naming latency), suffix_freq_per_cw (average suffix frequency of content words), and COCA_spoken_tri_2_MI (mean MI score of trigrams) were positively associated with UHR.

Discussions

Key findings

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the value of speech-derived sentiment and linguistic features in detecting UHR. We found that features capturing sentiment variability (i.e., EVA), lexical sophistication (i.e., TAALES), and morphology (i.e., TAMMI), are the most valuable for detecting youths at UHR. Our factor analysis revealed five factors underlying the top features, namely (1) Sentiment Intensity and Variability, (2) Linguistic Register Alignment, (3) Phonographic Uniqueness and Recognizability, (4) Morphological Complexity and Imageability, and (5) Lexical Richness and Typicalness. Additionally, when trained on the top features, our ML models provided a good accuracy (mean AUC = 0.70) in identifying youths at UHR.

Comparison with related studies

Our model did not score higher than similar models. Kizilay et al. trained RFCs on semantic similarity features and POS tags extracted from Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) transcripts to detect youths at UHR (AUC = 0.86)9. Corcoran et al. predicted conversion amongst youths at UHR (AUC = 0.87) using LR models trained on semantic cohesion features and POS tags extracted from Kiddie Formal Thought Disorder Story Game (K-FTDSG) transcripts12. Our model’s lower performance could be attributed to the length of our transcripts. HiSoC took 45 seconds, while TAT and K-FTDGS took approximately 8 and 25 minutes, respectively. The shorter transcript lengths could have affected the quality of extracted features, which ultimately limited model performance. Nonetheless, we achieved a modest AUC of 0.70. This result showcased the potential of using short speech samples to detect youths at UHR.

In contrast to similar studies, we did not identify cohesion features as top predictors for UHR detection. Previous studies have reported cohesion features (e.g., semantic similarity, semantic coherence) as top predictors for UHR detection and conversion, respectively9,12. One explanation is that cohesion features, including the presence and absence of semantic overlaps, may be more apparent and better captured in longer transcripts. Given the short speech samples analyzed here, we found that sentiment variability, lexical sophistication, and morphology are important.

Sentiment and linguistic characteristics of UHR speech

All features from the Sentiment Intensity and Variability factor were negatively associated with UHR, suggesting that UHR speech is characterized by diminished positive sentiments and persistent periods of negative sentiments. This finding echoes that of Olson et al., where they reported an association between UHR and the use of words with more negative emotional tones31. Diminished sentiment intensity and variability in speech could be a manifestation of anhedonia—a core negative symptom of schizophrenia32, which is also observed in UHR33,34. It is also important to note that anhedonia has been reported as a key predictor of social and occupational functioning in high-risk youths35.

All features from the Linguistic Register Alignment factor were negatively associated with UHR, suggesting that UHR speech deviates from typical spoken, fiction, and magazine registers. Divergence from normative linguistic patterns may point towards language disorganization which may be seen in UHR36 and psychosis6. Aberrant linguistic styles, such as higher levels of peculiar word usage, peculiar sentence construction, and peculiar logic in speech, have been observed in UHR, and manifests more strongly in psychosis36.

WN_SD_CW and OG_N from the Phonographic Uniqueness and Recognizability factor had positive and negative associations with UHR, respectively, suggesting that UHR speech is characterized by less recognizable and more phonographically unique words (i.e., words with few phonographic neighbors). The use of less recognizable words may point towards unusual and abnormal linguistic styles observed in psychosis37. Regarding phonographic uniqueness, OG_N captures the number of phonographic neighbors of each word relative to ELP’s lexicon instead of the transcript. Hence, we could not comment on the degree of phonological association within the transcripts. However, we would expect UHR speech to be characterized by phonologically similar words as clanging is associated with individuals with schizophrenia38.

MRC_Imageability_CW and Inflected_Tokens from the Morphological Complexity and Imageability factor were negatively associated with UHR, suggesting that UHR speech contains fewer imageable words and is morphologically less complex. Our finding on word imageability is surprising since the use of highly imageable words has been reported in individuals with schizophrenia39. However, this could be due to differences in the nature of the speech tasks. Our study employed HiSoC where participants responded freely to an open-ended question. In the referenced study, participants took part in the Figurative Language 2 (FL2) task from the Assessment of Pragmatic Abilities and Cognitive Substrates test, where they had to explain idioms, metaphors, and proverbs39. FL2 was designed to assess an individual’s ability to infer non-literal meanings from figurative language40. Due to difficulties in understanding figurative language, individuals with schizophrenia scored poorly on FL2 and used more imageable words in their explanations39. However, in open-ended tasks, the use of imageable words amongst individuals with psychotic disorders is not widely studied. More studies are required to elucidate associations between word imageability and psychotic disorders. On the other hand, previous studies have reported reductions in complex morphological structures in speech, such as verbs, adjectives, and adverbs, amongst patients with schizophrenia41, and their poor performance in morphology tasks, such as past tense production42. Moreover, suffix_freq_per_cw from the Morphological Complexity and Imageability factor was positively associated with UHR, which further suggests that UHR speech is characterized by simpler morphology.

LD_Mean_Accuracy_CW and COCA_spoken_tri_2_MI from the Lexical Richness and Typicalness factor had negative and positive associations with UHR, respectively, suggesting that UHR speech contain less typical words and more predictable lexical structures (n-gram combinations). The use of atypical words could reflect underlying thought impairments, which have been observed in psychosis37. On the other hand, the use of predictable lexical structures suggests a lack of lexical richness, pointing towards poverty of content (POC). POC is associated with conversion amongst youths at UHR10 and has been identified as a key predictor of psychosis onset12. Furthermore, amongst patients with formal thought disorder, those with POC tend to have poorer long-term prognosis43.

Large language models for UHR detection

Large language models (LLMs) are powerful text-based models with immense potential for clinical decision support (CDS). LLMs have powerful deductive capabilities and is likely to supersede current NLP techniques (if not already). However, they are complex black boxes and prone to hallucination. While LLMs are surprisingly good at certain clinical tasks, it is unknown if LLMs are competent in performing mental health diagnoses directly from speech data. Using the same UHR classification task, we compared our Boruta model against the untuned Llama 3.18B-Instruct model. To coax the LLM into its decision support task, we developed three levels of prompt engineering: First, we prompted the LLM to act as a CDS tool for predicting whether an individual is at UHR based on the speech transcript. This LLM achieved a balanced accuracy of 0.48 (slightly worse than chance). Next, we prompted the LLM to list the UHR criteria based on CAARMS and to use those criteria to evaluate the transcripts. The LLM was able to correctly list the criteria and scored a higher balanced accuracy of 0.50 (but still performs no better than chance). Finally, we performed few-shot prompting by specifying two transcript examples from each class (UHR positive and negative). This did not achieve much better results (balanced accuracy of 0.52). The structure and example of each prompt level are detailed in Supplementary Table 3.

Although the LLM did progressively improve with increasing levels of prompt engineering, its best accuracy is only marginally higher than that of a random classifier based on our data. These early findings suggest directly tuning out-of-box LLMs for speech-based diagnosis may be insufficient. We suspect that training corpora with explicit mental health labels may be lacking due to high sensitivity concerns. This also implies such LLMs cannot be relied on for meaningful clinical explanations. Although disappointing and surprising given recent published literature, we believe this also highlights an exciting gap for future research where we may develop new ways to train LLMs–possibly, by adding more modalities and examples to finetune the model. There are also exciting recently published local mental health LLM models trained on social media data that we can also evaluate using our data44,45. Finally, given the deep domain-expertise incorporated into existing NLP methods, there may be opportunity to integrate these NLP features with LLMs to enhance model explainability and performance, bringing us closer towards speech-based CDS systems for mental health.

Limitations

Class imbalance issues

Amongst the 429 speech transcripts available, only 80 belonged to the UHR positive group. This major imbalance between UHR positive and negative samples could result in uneven data distribution during train-test partitioning, leading towards model underfitting. To alleviate this issue, we used leave-one-out cross-validation to ensure that most of the UHR positive samples are included in the training data in each iteration. This prevents the model from training on radically small and different subsets of the UHR cohort. This reduces model bias and performance instability.

Cohort and data heterogeneity

While informative, the shortlisted features may not guarantee generalizable performance since our cohort is small and local. Additionally, participant behavior on the HiSoC task was highly varied, despite standardized instructions and a 45-second limit. Sparse speech content presented further challenges for our model. Moreover, some reference corpora (e.g., COCA) may be grammatically different from Singlish—the colloquial form of English used in Singapore. Such linguistic differences that are present in the transcripts cannot be captured by the extracted features. While LLMs pre-trained on Singlish texts may alleviate this issue, we ultimately opted for ML models trained on established NLP features as they are better equipped for model explainability. In future work, we can explore the integration of culturally or socially contextualized speech constructs to further enhance model performance.

Duration of HiSoC task

Participants were only given 10 s to prepare and 45 s to respond. These relatively short preparation and response times may serve to induce anxiety in participants and capture their responses to immediate stimuli. However, different participants may experience different levels of anxiety, which could in turn, be a confounding variable. Furthermore, the short duration of the HiSoC task may limit our ability to fully assess the participants’ mood, thought patterns, and cognitive processes.

Limitations of extracted features

The WN_SD_CW values were derived from the ELP word naming task and do not represent the word naming latencies of our participants. Thus, we could not compare the word naming latencies between the UHR and control groups. Similarly, the OG_N values were retrieved from the ELP lexicon and do not capture the degree of phonological association within the participants’ transcripts. This information could be useful for detecting clanging, which is associated with individuals with schizophrenia38.

Impact and future work

Having tested and evaluated an extensive set of sentiment and linguistic features, we now know which representations of speech transcribed text are most informative for UHR detection. While challenging, developing text-based technologies is highly rewarding given the prevalence of textual data in online interactions and real-world applications (e.g., social media platforms, online help portals). Upon achieving robust modeling of text features, we can incorporate other key communication modalities (e.g., facial expressions, gaze, body movements) to create more comprehensive and powerful multimodal models, which could provide a more holistic representation of each patient and give rise to clinically relevant explanations.

Conclusions

Combining speech-derived text features with powerful feature selection and ML algorithms can help in early identification of youths at UHR. Amongst various text constructs, those capturing sentiment variability (i.e., EVA), lexical sophistication (i.e., TAALES), and morphological information (i.e., TAMMI) are valuable for improving model performance and providing interpretable metrics.

Data availability

The HiSoC transcripts were obtained from LYRIKS. The data set generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as we do not have consent from participants to upload their data to public servers. However, interested persons can contact the corresponding authors to enquire on data access.

Code availability

EVA is available at https://qr.page/g/5jQ8DQmWQT4. TAACO, TAALES, TAMMI, TAASSC, and TAALED are available at https://www.linguisticanalysistools.org/.

References

Subramaniam, M. et al. Tracking the mental health of a nation: prevalence and correlates of mental disorders in the second Singapore mental health study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 29, e29 (2020).

Goodwin, R. D. et al. Trends in U.S. depression prevalence from 2015 to 2020: The widening treatment gap. Am. J. Prevent. Med. 63, 726–733 (2022).

Castelpietra, G. et al. The burden of mental disorders, substance use disorders and self-harm among young people in Europe, 1990–2019: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Regional Health – Eur. 16, 100341 (2022).

Sacco, R., Camilleri, N., Eberhardt, J., Umla-Runge, K. & Newbury-Birch, D. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents in Europe. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 33, 2877–2894 (2024).

Jorm, A. F. Mental health literacy: empowering the community to take action for better mental health. Am. Psychol. 67, 231–243 (2012).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. (American Psychiatric Association, Arlington, VA, 2013).

Sweeney, C., Ennis, E., Mulvenna, M. D., Bond, R. & O’Neill, S. Insights Derived From Text-Based Digital Media, in Relation to Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, Using Data Analysis and Machine Learning: Systematic Review. JMIR Ment. Health 11, e55747 (2024).

Hartmann, S. et al. Development and temporal validation of a clinical prediction model of transition to psychosis in individuals at ultra-high risk in the UHR 1000+ cohort. World Psychiatry 23, 400–410 (2024).

Kizilay, E. et al. Automated linguistic analysis in youth at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 274, 121–128 (2024).

Bearden, C. E., Wu, K. N., Caplan, R. & Cannon, T. D. Thought Disorder and Communication Deviance as Predictors of Outcome in Youth at Clinical High Risk for Psychosis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 50, 669–680 (2011).

Bedi, G. et al. Automated analysis of free speech predicts psychosis onset in high-risk youths. npj Schizophr. 1, 15030 (2015).

Corcoran, C. M. et al. Prediction of psychosis across protocols and risk cohorts using automated language analysis. World Psychiatry 17, 67–75 (2018).

Crossley, S. A., Kyle, K. & McNamara, D. S. The tool for the automatic analysis of text cohesion (TAACO): Automatic assessment of local, global, and text cohesion. Behav. Res. Methods 48, 1227–1237 (2016).

Chiche, A. & Yitagesu, B. Part of speech tagging: A systematic review of deep learning and machine learning approaches. J. Big Data 9, 10 (2022).

Tan, L., Tan, O. K., Sze, C. C. & Goh, W. W. B. Emotional variance analysis: A new sentiment analysis feature set for Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning applications. PLOS ONE 18, e0274299 (2023).

Kyle, K. & Crossley, S. The relationship between lexical sophistication and independent and source-based writing. J. Second Lang. Writ. 34, 12–24 (2016).

Crossley, S. A., Tywoniw, R. & Choi, J. S. The Tool for Automatic Measurement of Morphological Information (TAMMI). Behav. Res. Methods 56, 5918–5929 (2024).

Kyle, K. Measuring Syntactic Development in L2 Writing: Fine Grained Indices of Syntactic Complexity and Usage-Based Indices of Syntactic Sophistication. (Georgia State University, 2016).

McCarthy, P. M. & Jarvis, S. MTLD, vocd-D, and HD-D: A validation study of sophisticated approaches to lexical diversity assessment. Behav. Res. Methods 42, 381–392 (2010).

Lee, J. et al. The Longitudinal Youth at Risk Study (LYRIKS) — An Asian UHR perspective. Schizophr. Res. 151, 279–283 (2013).

Yung, A. R. et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: The comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 39, 964–971 (2005).

Gibson, C. M., Penn, D. L., Prinstein, M. J., Perkins, D. O. & Belger, A. Social skill and social cognition in adolescents at genetic risk for psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 122, 179–184 (2010).

Crossley, S. A., Kyle, K. & Dascalu, M. The tool for the automatic analysis of cohesion 2.0: Integrating semantic similarity and text overlap. Behav. Res. Methods 51, 14–27 (2019).

Kyle, K., Crossley, S. & Berger, C. The tool for the automatic analysis of lexical sophistication (TAALES): version 2.0. Behav. Res. Methods 50, 1030–1046 (2018).

Tywoniw, R. & Crossley, S. Morphological complexity of L2 discourse. In The Routledge Handbook of Corpus Approaches to Discourse Analysis 269–297 (Routledge, New York, NY, 2020).

Kyle, K., Crossley, S. A. & Jarvis, S. Assessing the validity of lexical diversity indices using direct judgements. Lang. Assess. Q. 18, 154–170 (2021).

Degenhardt, F., Seifert, S. & Szymczak, S. Evaluation of variable selection methods for random forests and omics data sets. Brief. Bioinforma. 20, 492–503 (2019).

Kursa, M. B. & Rudnicki, W. R. Feature Selection with the Boruta Package. J. Stat. Soft. 36, 1–13 (2010).

Hinkle, D., Wiersma, W. & Jurs, S. Applied Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. (Houghton Mifflin, Boston, MA, 2003).

Paivio, A., Yuille, J. C. & Madigan, S. A. Concreteness, imagery, and meaningfulness values for 925 nouns. J. Exp. Psychol. 76, 1–25 (1968).

Olson, G. M., Damme, K. S. F., Cowan, H. R., Alliende, L. M. & Mittal, V. A. Emotional tone in clinical high risk for psychosis: Novel insights from a natural language analysis approach. Front. Psychiatry 15, 1389597 (2024).

Correll, C. U. & Schooler, N. R. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: A review and clinical guide for recognition, assessment, and treatment. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 16, 519–534 (2020).

Pelizza, L. et al. Anhedonia in adolescents at ultra-high risk (UHR) of psychosis: findings from a 1-year longitudinal study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 270, 337–350 (2020).

Cressman, V. L. et al. Anhedonia in the psychosis risk syndrome: associations with social impairment and basal orbitofrontal cortical activity. npj Schizophr. 1, 15020 (2015).

Mechelli, A. et al. Using clinical information to make individualized prognostic predictions in people at ultra high risk for psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 184, 32–38 (2017).

Demjaha, A. et al. Formal thought disorder in people at ultra-high risk of psychosis. BJPsych Open 3, 165–170 (2017).

Ayer, A. et al. Formal thought disorder in first-episode psychosis. Compr. Psychiatry 70, 209–215 (2016).

Covington, M. A. et al. Schizophrenia and the structure of language: the linguist’s view. Schizophr. Res. 77, 85–98 (2005).

Bambini, V. et al. From semantic concreteness to concretism in schizophrenia: An automated linguistic analysis of speech produced in figurative language interpretation. Clin. Linguistics Phonetics 1–23 https://doi.org/10.1080/02699206.2025.2451961.

Arcara, G. & Bambini, V. A test for the assessment of pragmatic abilities and cognitive substrates (APACS): Normative data and psychometric properties. Front. Psychol. 7, 70 (2016).

Ziv, I. et al. Morphological characteristics of spoken language in schizophrenia patients – an exploratory study. Scand. J. Psychol. 63, 91–99 (2022).

Walenski, M., Weickert, T. W., Maloof, C. J. & Ullman, M. T. Grammatical processing in schizophrenia: evidence from morphology. Neuropsychologia 48, 262–269 (2010).

Wilcox, J., Winokur, G. & Tsuang, M. Predictive value of thought disorder in new-onset psychosis. Compr. Psychiatry 53, 674–678 (2012).

Xu, X. et al. Mental-LLM: Leveraging Large Language Models for Mental Health Prediction via Online Text Data. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. vol. 8, 31 (2024).

Ji, S. et al. MentalBERT: Publicly available pretrained language models for mental healthcare. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2110.15621 (2021).

Brezina, V. & Pallotti, G. Morphological complexity in written L2 texts. Second Lang. Res. 35, 99–119 (2019).

Sánchez-Gutiérrez, C. H., Mailhot, H., Deacon, S. H. & Wilson, M. A. MorphoLex: A derivational morphological database for 70,000 English words. Behav. Res. Methods 50, 1568–1580 (2018).

Kyle, K. & Crossley, S. Assessing syntactic sophistication in L2 writing: A usage-based approach. Lang. Test. 34, 513–535 (2017).

Lu, X. Automatic analysis of syntactic complexity in second language writing. Int. J. Corpus Linguist. 15, 474–496 (2010).

Davies, M. The 385+ million word Corpus of Contemporary American English (1990–2008 + ): Design, architecture, and linguistic insights. Int. J. Corpus Linguist. 14, 159–190 (2009).

Balota, D. A. et al. The English Lexicon Project. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 445–459 (2007).

Coltheart, M. The MRC psycholinguistic database. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. A: Hum. Exp. Psychol. 33 A, 497–505 (1981).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Ms Xiang Ni Long and Ms Yue Xin Lee for transcribing the videos. This research was supported by the National Medical Research Council (NMRC), Singapore, under its Population Health Research Grant (PHRG) scheme, Project No. PHRGOC24jul-0026. The LYRIKS study was supported by the National Research Foundation Singapore under the National Medical Research Council Translational and Clinical Research Flagship Program (grant number NMRC/TCR/003/2008). JL acknowledges funding support from the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council (grant number MOH-CSAINV23jan-0006). WWBG acknowledges support from the following MOE Tier 1 awards (RS08/21 and RT11/21).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.J.K. and S.S. performed experiments and developed figures. S.M.X.T. designed analysis protocols and analyzed data. N.H.F. co-wrote the methods section. M.C.L. co-wrote the discussions section. J.Y.Y. collected the data and designed the study. Z.Y. collected the data and provided clinical interpretations. E.Y.H.C. provided clinical interpretations. J.L. and W.W.B.G. supervised the study and acquired funding. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.L. had received honoraria, served as a consultant or advisory board member from Otsuka, Janssen, Lundbeck, Sumitomo Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, ThoughtFull World Pte. Ltd. and Singapore Deep-Tech Alliance. The other authors declare no competing interests, financial or otherwise.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kho, J.J., Song, S., Tan, S.M.X. et al. Leveraging computational linguistics and machine learning for detection of ultra-high risk of mental health disorders in youths. Schizophr 11, 98 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00649-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00649-3

This article is cited by

-

The Use of Artificial Intelligence for Personalized Treatment in Psychiatry

Current Psychiatry Reports (2025)