Abstract

Testosterone play an important role in schizophrenia, particularly for impulsive aggressive behaviors. However, there is still unclear how the neurobiological basis and correlates of these risk factors in schizophrenia patients. The schizophrenia patients who visited psychiatric emergency departments (PED) with an acute stage and received an evaluation of aggression and psychotic symptoms by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) were included. Blood samples were collected for plasma testosterone measurement. The network analysis and network comparison test were conducted to construct and evaluate whether network characteristics differed by gender. The prevalence of level Ⅱ aggression was 41.4%, level Ⅲ aggression was 33.3%, and level Ⅳ aggression was 8.8% in the SCZ patients visited in PED, respectively. The total score of PANSS, the average level of testosterone, and the proportion of males in the aggressive group were higher than those in the non-aggressive group, respectively. Network analysis identified “Guilt feelings”, “Poor impulse control” and “Difficulty in abstract thinking” as the most influential symptoms. “Poor impulse control” appeared to be the bridge symptom linking psychotic symptoms to aggressive behavior. Concurrently, “Poor impulse control” stand as critical bridge symptoms between psychotic symptoms to aggressive behaviors. Moreover, “Blunted affect” exhibited the strongest positive correlation with testosterone levels among SCZ patients in the acute stage. The findings highlight the complex interplay between testosterone and psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia patients, emphasizing the importance of targeting influential symptoms in psychiatric emergency care. The identification of central and bridge symptoms suggests potential pathways for individual interventions for SCZ patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Numerous studies have demonstrated that individuals with schizophrenia are more prone to exhibit aggressive behaviors, including verbal or physical threats and even homicide1,2,3. Patients in the acute phase of schizophrenia may engage in high-risk aggressive behaviors necessitating heightened vigilance. Command hallucinations or paranoid delusions can precipitate sudden aggression toward others or self-injury. Impaired reality testing often manifests as refusal to eat (due to delusional beliefs of poisoning) or extreme behaviors (e.g., impulsive jumping). Acute relapses frequently result from medication non-adherence, and symptoms may emerge abruptly without warning. Emergency hospitalization provides structured supervision to mitigate harm risks, while pharmacotherapy enables rapid symptom stabilization. These aggressive behaviors assessed by psychiatrist in psychiatric emergency departments (PEDs) often exhibit significant unpredictability and randomness, posing challenges for effective prevention and control for health care workers especially working in emergency departments4,5,6. Patients with schizophrenia frequently exhibit aggressive behaviors associated with uncontrolled acute-phase symptoms or comorbid conditions. Notably, these behaviors tend to be more violent and severe compared to those observed during the manic phase of bipolar disorder. Aggressive behaviors in schizophrenia can be attributed to psychopathological symptoms such as hostile behaviors, poor impulse control, lack of insight, substance abuse, and other clinical manifestations7,8,9. Additionally, distinct neurobiological mechanisms may play a critical role in the relationship between aggressive behaviors and psychotic symptoms. However, the neurobiological underpinnings of aggressive behaviors in patients with schizophrenia remain underexplored.

Testosterone, a key sex hormone and androgenic steroid regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, governs the development of male sexual characteristics and is closely linked to human behaviors and emotions10,11,12. It modulates dopaminergic, glutamatergic, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission systems. Notably, dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra express testosterone receptors13,14. Researchers indicate that serotonergic (5-HT) dysregulation is associated with behaviors such as aggression, while androgens influence the distribution and regulation of 5-HT receptor subtypes, including 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B15,16. Testosterone surges enhance excitatory neurogenesis, with inhibitory neural progenitors exhibiting reduced responsiveness, thereby disrupting the excitatory/inhibitory balance17. Furthermore, testosterone has been implicated in aggressive behaviors among individuals with psychotic symptoms. A longitudinal study suggests that elevated testosterone levels may contribute to heightened aggressiveness in schizophrenia patients18. Elucidating the interactions between testosterone and schizophrenia’s clinical manifestations is critical for understanding the disease’s pathophysiology and identifying therapeutic targets, particularly for patients in acute stages.

Network analysis, a methodological approach grounded in graph theory, is used to describe and analyze interconnected relationships or interactive data structures within complex systems. In recent years, this approach has gained prominence in psychology and psychiatry. Network analysis has emerged as a novel methodological framework for modeling biological systems by predicting interactions among symptoms and biomarkers19,20. Complex bilateral dynamic associations between symptoms are often present, suggesting interaction rather than unidirectional causality. The bilateral network identified “bridge nodes” between symptoms that could inform targeted interventions, while the directional network ignored such critical paths21. In conclusion, the bilateral nature of network analysis is more suitable for the complexity and dynamic needs of semiology22. Network analysis has been applied to explore relationships between symptoms across emotional, behavioral, and cognitive domains, identifying central symptoms in specific disorders10,23,24. We hypothesize that elevated testosterone levels in patients may reflect heightened neurobiological activity, potentially exacerbate impaired impulse control and increase aggression risk. This dysfunction may impair patients’ ability to anticipate behavioral consequences. Clinicians require robust empirical frameworks to identify schizophrenia patients at the highest aggression risk, as systematic monitoring and targeted interventions for this subgroup are well-documented treatment priorities. This study aim is to investigate the complex interplay between aggressive behaviors and testosterone levels in individuals with schizophrenia, aiming to identify key intervention targets and thereby inform targeted therapeutic strategies.

Methods

Patients and study sites

A cross-sectional survey was conducted between January 2021 and March 2022 at the emergency department of Beijing Anding Hospital, a tertiary psychiatric hospital providing the only 24 h emergency psychiatric care service in Beijing and neighboring provinces. Participants were consecutively enrolled during the study period if they met the following criteria: (1) receiving emergency maintenance treatment for schizophrenia spectrum disorders, (2) providing written informed consent, and (3) having a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia in the acute stage (ICD-10 code: F20). Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee at Beijing Anding Hospital, in compliance with institutional and national ethical standards.

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of schizophrenia patients-including age, age at first episode, gender, education level, marital status, employment status, illness duration, type of medical insurance, and family history of psychiatric disorders-were collected using a formally designed questionnaire for this study. Data were verified through clinical interviews conducted by psychiatrists.

Blood collection and assays of testosterone

Routine blood samples were collected during visiting psychiatric emergency for clinical evaluations. Serum samples from all schizophrenia patients were obtained between 7:30 AM and 8:30 AM. Testosterone levels (μg/dL) in these morning serum samples were measured via chemiluminescence. Laboratory personnel were blinded to all clinical data. Blood sample collection and processing adhered to standard operating procedures approved by the Ethics and Scientific Committee of Capital Medical University, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measurement

Psychotic symptoms were assessed by two psychiatrists using the Chinese version of Positive and Negative Systems Scale (PANSS)25,26. The PANSS is a clinical instrument designed to evaluate the presence and severity of psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. It consists of 30 items divided into three subscales: positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and general psychopathology. Each item is scored from 1 (no symptoms) to 7 (severe symptoms), yielding a total possible score of 210. Three supplementary items assessing aggression symptoms were included. Clinical data, including age, age at first schizophrenia diagnosis, and illness duration, were also recorded. The Chinese PANSS version has demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties. Assessors received standardized PANSS training prior to study commencement.

In this study, aggressive behavior was assessed through interviews conducted by trained psychiatrists within 12 h of admission. The aggression subscale of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS-AG) was utilized; this tool incorporates supplementary items assessing risk factors such as anger, impulsivity, and emotional instability27. The PANSS has been validated in the Chinese population and demonstrates satisfactory psychometric properties (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84)28. Additionally, participants’ aggressive behavior was graded using a standardized scale established by the local health authority, which is widely employed in Chinese clinical practice and has been empirically validated in prior research29. This scale determines the intensity of each form of aggression on a scale graded from I to VI. That is, the risk factors for Level I aggressive behaviors include male gender, presence of auditory hallucinations or persecutory delusions, and a history of maladaptive personality traits. Level II is characterized by passive verbal aggression (e.g., nonspecific complaints, whining, bizarre speech) and hostile communication patterns, alongside imperative auditory hallucinations. Level III involves active verbal aggression (e.g., name-calling), passive physical aggression (e.g., object destruction), social rudeness, and a prior history of physical aggression. Level IV constitutes active physical aggression, such as kicking, hitting, biting, or striking others with objects, occurring at least twice daily or causing physical injury. A rating above level II indicates aggressive behavior in clinically significant.

Statistical analyses

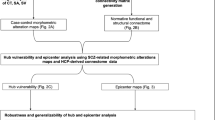

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26.0). Normality was assessed via the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. A network model examining comorbid psychotic symptoms, aggressive behaviors, and testosterone levels among patients with schizophrenia in psychiatric emergency services was constructed in R statistical software30. Network analysis first computed polychoric correlations between all items and subsequently estimated a graphical Gaussian model (GGM) using the graphical least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) with the Extended Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC)31.

The importance of each node in the network was assessed via Expected Influence (EI) centrality indices using the R-package “graph”32. EI centrality, calculated as the sum of absolute connection weights for each node, was prioritized for its stability and interpretability. Edge thickness corresponds to the strength of associations. Building on prior research identifying testosterone as a key node bridging symptom communities in comorbid psychotic syndromes33, we estimated testosterone’s predictive betweenness centrality. This metric reflects how frequently testosterone lies on pathways between two other nodes across 1000 bootstrap iterations34,35,36. To identify symptoms directly linked to testosterone, the flow function in q graph was employed37.

Building on prior methodology38,39, we compared sex-based differences in network characteristics using the R package Network Comparison Test (Version 2.2.1)40 with 1000 permutations. Differences in network structure (including edge weight distributions), global strength (total absolute symptom connectivity), and individual edges between subsamples (female vs. male participants) were evaluated.

Ethical approval

This study involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Human Research and Ethics Committee of Beijing Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University. All the study procedures were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines.

Results

Social-demographic and clinical characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. A total of 474 patients were invited to participate in this study. Of these, 467 schizophrenia patients met the study criteria and were included in analyses (response rate: 98.7%); the rest of them were excluded in the analysis due to incomplete data. The prevalence of aggressive behaviors was 41.4% for level II, 33.3% for level III, and 8.8% for level IV. The mean PANSS total score was 80.05 ± 22.37. Male participants exhibited a mean total testosterone level of 323.75 ± 192.47 ng/dL (reference range: 260–1590 ng/dL), compared to 36.48 ± 23.71 ng/dL (reference range: 15–80 ng/dL) in female participants. In the univariate analyses, aggression was significantly associated with Male gender, high BMI, more total score and positive symptom score on the PANSS scale, and high testosterone level (Table 1).

Network structure

Figure 1 depicts the network structure modeling the interrelationships among psychotic symptoms, aggressive behaviors, and testosterone among schizophrenia patients in acute stage. The network model reveals that the strongest positive association among positive symptoms community in PANSS is between P1 (“Delusions”) and P6 (“Suspiciousness/persecution”), followed by P1 (“Delusions”) and P3 (“Hallucinatory behavior”). Within the negative symptoms community in PANSS is the connection between N1 (“Blunted affect”) and N2 (“Emotional withdrawal”) is the strongest, with the next strongest link between N2 (“Emotional Withdrawal”) and N4 (“Passive/Apathetic Social Withdrawal”). Within the general psychopathology community in PANSS, the most robust association was between G2 (“Somatic Concern”) and G4 (“Tension”), followed by G11 (“Poor Attention”) and G15 (“Preoccupation”). For the aggressive behaviors, the node S1 (“Anger”) exhibited the strongest direct connection with S2 (“Impulsivity”), followed by S2 (“Impulsivity”) and S3 (“Emotional Instability”) (Fig. 1). The clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

Regarding EI centrality within the network of interrelationships among psychotic symptoms, aggressive behaviors, and testosterone in acutely illness schizophrenia patients (Fig. 2). The node G3 (“Guilt feelings”) exhibited the highest EI centrality, followed by G14 (“Poor impulse control”) and N5 (“Difficulty in abstract thinking”). In bridge EI analysis, G14(“Poor impulse control”) emerged as the most critical bridge symptom connecting these domains, followed by P2 (“Conceptual Disorganization”) and N5 (“Difficulty in Abstract Thinking”). Furthermore, the strongest positive correlation with testosterone was observed for N1 (“Blunted Affect”), followed by P3 (“Hallucinatory Behavior”) and N7 (“Stereotyped Thinking”).G14 (“Poor Impulse Control”) demonstrated the strongest negative association with testosterone, with aggression severity (AS) ranking second (Fig. 3).

In terms of network stability, EI centrality exhibited a high level of robustness, as evidenced by a CS-coefficient of 0.592 (95% CI: 0.516–0.672). This result suggests that the network structure remains largely consistent even after removing 59% of the sample (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the bootstrap difference test demonstrated that the majority of edge weight comparisons were statistically significant (Fig. 4).

Node-specific Predictive Betweenness Measure

Previous research has established a significant association between testosterone levels and aggressive behavior33. Figure 4 depicts node-specific predictive betweenness values within the network. White dots denote the betweenness values observed in the study sample, while black lines illustrate variability across 1,000 nonparametric bootstrap iterations. Node N1 (“Blunted affect”) exhibited the highest predictive betweenness, followed by G7 (“Motor retardation”) and N2 (“Emotional withdrawal”). These results suggest that blunted affect, motor retardation, and emotional withdrawal may serve as critical bridge symptoms linking testosterone levels, comorbid psychotic symptoms, and aggressive behaviors in acutely ill SCZ patients (Fig. 5).

Network Comparison Tests by gender

The comparison of network models between genders revealed no significant differences in global network strength (female participants: 15.87 vs. male participants: 12.82; M = 0.171, P = 0.157) or edge weights (S = 3.05, P = 0.947; Supplementary Figs. S1–S2).

Discussion

This is the first study applying network analysis to explore the relationships among psychotic symptoms, aggressive behaviors, and testosterone levels. One major finding was the notable influence of two general psychopathology, namely guilt feelings and poor impulse control, as well as a negative symptom (difficulty in abstract thinking), with acceptable centrality indices within the network of psychotic symptoms and aggression. This prominence of psychopathology and aggression can be attributed to the testosterone levels of the study participants in the acute stage, mediated by poor impulse control41. Identifying central and bridge symptoms within the aggressive symptom network model of schizophrenia holds clinical significance for preventing aggression in high-risk patients. This model particularly emphasizes the critical role of control processes when developing targeted therapeutic interventions for schizophrenia patients with elevated aggression risk in psychiatric emergency departments (PEDs).

The evidence supporting the prevalence of aggression risk in schizophrenia and its associated factors is mixed. In the present study, the frequency of aggression level III in patients with an acute schizophrenia episode was 33.3%, and 8.8% for level IV were higher than that reported in most Western countries: in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, approximately 3–24.6% had current homicidal/aggressive behaviors in psychiatric emergency department setting42. A systematic review found that the prevalence of aggressive behaviors varied considerably across settings, with the highest rate (mean, 28.0%; range, 9.1–55%) in Chinese inpatients with schizophrenia43. In addition, the risk of committing homicide was 20-fold higher in patients with psychotic disorders44. Caution is needed that the true prevalence of aggression in individuals with schizophrenia is difficult to ascertain because it is commonly only one of many items that contributes to scales or subscales. Treatment guidelines recommend the use of purposeful behavioral and environmental de-escalation strategies for agitation and aggression in the acute stage before other more restrictive or invasive strategies are used45,46. schizophrenia patients who were male and had a high BMI reported more frequent aggression, which is consistent with previous findings. High BMI is a typical metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia patients, which has been reported clinically as a comorbidity of schizophrenia and obesity. Previous studies have also shown that there is a genetic association between schizophrenia and BMI47,48. In contrast to the indirect aggression of female patients, male patients tend to show direct physical and verbal aggression, therefore, are more likely to be physically restrained49.

In the symptom network model, poor impulse control, guilt feelings, difficulty in abstract thinking, and conceptual disorganization emerged as the most central symptoms among schizophrenia patients during acute stages. Consistent with prior findings, poor impulse control-characterized by a tendency to overreact to stimuli, potentially escalating into aggressive behaviors-has been identified as a key risk factor in patients with schizophrenia41,50. Additionally, impaired executive function and dysregulated top-down behavioral control in these patients may result in insufficient regulation of their actions, thereby heightening risks of impulsivity and aggression9. Testosterone may influence emotional regulation in individuals with schizophrenia via its interaction with the 5-HT system, thereby modulating impulsivity control51,52. Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that testosterone could impact impulse control capacity through its association with cognitive functioning in schizophrenia53,54,55. Difficulty in abstract thinking represents a central symptom in our network model. Studies have identified “conceptual disorganization” and “difficulty in abstract thinking” as the two most significant predictors of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia patients based on the PANSS framework56. Research indicates that hospitalized schizophrenia patients exhibiting this symptom often demonstrate arbitrary generalizations during mental state reasoning, instead basing their judgments on subjective emotional impressions57. Consequently, they commonly rationalize aggressive behaviors toward others as defensive responses to perceived environmental threats. Notably, these distorted perceptions of insecurity often demonstrate significant impairments in reality testing capacity. Such patterns may heighten risks of harmful behavioral outcomes, including elevated hostility and aggression.

The risk of aggression across different psychotic symptoms and testosterone levels remains a topic of controversy. Poor impulse control emerged as the most critical bridge symptom connecting these domains, followed by a positive symptom (difficulty in abstract thinking) and a negative symptom (difficulty in abstract thinking). Studies comparing SCZ patients with and without self-directed aggression reveal that those exhibiting self-directed aggression demonstrate greater severity of conceptual disorganization, characterized by psychomotor excitement and severe psychotic symptoms58. This evidence suggests that testosterone may exacerbate cognitive impairments, particularly conceptual disorganization and difficulty in abstract thinking as measured by the PANSS, via its association with cognitive functioning in schizophrenia.

Guilt feelings represent a central symptom in this network model. Individuals with schizophrenia often externalize guilt through pathological cognition, attributing blame for their errors and inappropriate behaviors to others, which may escalate hostility and aggression59,60. Furthermore, the association between guilt feelings and aggression may be moderated by social status and narcissistic traits61. Testosterone is strongly associated with dominance and status-seeking behaviors, with elevated levels potentially exacerbating competitive and aggressive actions to maintain social standing62,63. According to the dual-hormone hypothesis, testosterone positively correlates with aggression and dominance in pursuit of social status, particularly among individuals with low cortisol levels. Consequently, testosterone may indirectly exacerbate guilt feelings through its linkage to social dominance and status-seeking behaviors.

The strengths of this study include a large sample of acute-phase schizophrenia patients and a novel data processing method, which enhances the statistical reliability and generalizability of the findings. However, notable limitations remain that need to be mention. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences between variables; future longitudinal studies could clarify these relationships. Second, serum testosterone levels may have been influenced by prior antipsychotic medication use among patients exhibiting impulsive behaviors. Future research should implement stricter protocols to control for medication effects. Third, while routine blood samples were collected during emergency assessments, incorporating additional biomarkers or clinical indicators could strengthen analyses. Finally, advanced methodologies such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) could provide multidimensional insights into these complex relationships.

Conclusion

This study’s identifies poor impulse control, guilt feelings, difficulty in abstract thinking, and conceptual disorganization as the most critical symptoms among schizophrenia patients admitted to psychiatric emergency departments in the acute stage. Investigating factors influencing aggressive behavior in this population may enable early detection of warning signs, thereby informing targeted interventions to enhance clinical management strategies.

Data availability

The data of the investigation will be made publicly available if necessary.

References

Soyka, M. Neurobiology of Aggression and Violence in Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 37, 913–920 (2011).

Cho, W. et al. Biological Aspects of Aggression and Violence in Schizophrenia. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 17, 475–486 (2019).

Blanco, E. A. et al. Predictors of Aggression in 3.322 Patients with Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Evaluated in an Emergency Department Setting. Schizophr. Res 195, 136–141 (2018).

San, L. et al. State of Acute Agitation at Psychiatric Emergencies in Europe: The Stage Study. Clin. Pr. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 12, 75–86 (2016).

Singh, A. S., Borgohain, L. & Singh, B. Aggression and Its Correlation with Plasma C-Reactive Protein Levels in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Hospital Based Cross-Sectional Study. Indian J. Psychiatry 65, 667–670 (2023).

Välimäki, M., Lantta, T. & Kontio, R. Risk Assessment for Aggressive Behaviour in Schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 5, Cd012397 (2024).

Fazel, S., Hayes, A. J., Bartellas, K., Clerici, M. & Trestman, R. Mental Health of Prisoners: Prevalence, Adverse Outcomes, and Interventions. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 871–881 (2016).

Witt, K., van Dorn, R. & Fazel, S. Risk Factors for Violence in Psychosis: Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis of 110 Studies. PLoS One 8, e55942 (2013).

Gao, L. et al. Correlation between Aggressive Behavior and Impulsive and Aggressive Personality Traits in Stable Patients with Schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 19, 801–809 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Network Analysis of Comorbid Aggressive Behavior and Testosterone among Bipolar Disorder Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Transl. Psychiatry 14, 224 (2024).

Geniole, S. N. et al. Is Testosterone Linked to Human Aggression? A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Relationship between Baseline, Dynamic, and Manipulated Testosterone on Human Aggression. Horm. Behav. 123, 104644 (2020).

Romanova, Z., Hrivikova, K., Riecansky, I. & Jezova, D. Salivary Testosterone, Testosterone/Cortisol Ratio and Non-Verbal Behavior in Stress. Steroids 182, 108999 (2022).

Mohandass, A. et al. Trpm8 as the Rapid Testosterone Signaling Receptor: Implications in the Regulation of Dimorphic Sexual and Social Behaviors. Faseb j. 34, 10887–10906 (2020).

Razaghi, R., Piri, H., Jafari, H., Rastgoo, N. & Hosseini, M. A. H. Haghdoost Yazdi. Evaluation of the Association between Serum Levels of Testosterone and Prolactin with 6- Hydroxydopamine-Induced Parkinsonism in Male Rats. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 12, 453–464 (2021).

Gouveia, F. V. et al. Reduction of Aggressive Behaviour Following Hypothalamic Deep Brain Stimulation: Involvement of 5-Ht(1a) and Testosterone. Neurobiol. Dis. 183, 106179 (2023).

Fedotova, J. & Hritcu, L. Testosterone Promotes Anxiolytic-Like Behavior in Gonadectomized Male Rats Via Blockade of the 5-Ht(1a) Receptors. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 254, 14–21 (2017).

Kight, K. E. & McCarthy, M. M. Androgens and the Developing Hippocampus. Biol. Sex. Differ. 11, 30 (2020).

Huang, W. et al. Serum Progesterone and Testosterone Levels in Schizophrenia Patients at Different Stages of Treatment. J. Mol. Neurosci. 71, 1168–1173 (2021).

Tao, Y., Niu, H., Hou, W., Zhang, L. & Ying, R. Hopelessness During and after the Covid-19 Pandemic Lockdown among Chinese College Students: a Longitudinal Network Analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 79, 748–761 (2023).

Núñez, D. et al. Suicidal Ideation and Affect Lability in Single and Multiple Suicidal Attempters with Major Depressive Disorder: An Exploratory Network Analysis. J. Affect Disord. 272, 371–379 (2020).

Barlati, S. et al. The Interplay between Childhood Trauma, Hopelessness, Depressive Symptoms, and Mental Pain in a Large Sample of Patients with Severe Mental Disorders: A Network Analysis. J. Affect Disord. 380, 545–551 (2025).

Isvoranu, A. M., Guloksuz, S., Epskamp, S., van Os, J. & Borsboom, D. Toward Incorporating Genetic Risk Scores into Symptom Networks of Psychosis. Psychol. Med. 50, 636–643 (2020).

E. Fonseca-Pedrero. S. Al-Halabí. A. Pérez-Albéniz, & M. Debbané. Risk and Protective Factors in Adolescent Suicidal Behaviour: A Network Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 1784 (2022).

Brogan, A. et al. A Network Analysis of the Causal Attributions for Obesity in Children and Adolescents and Their Parents. Psychol. Health. Med. 24, 1063–1074 (2019).

Kay, S. R., Fiszbein, A. & Opler, L. A. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (Panss) for Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 13, 261–276 (1987).

Jiang, J., Sim, K. & Lee, J. Validated Five-Factor Model of Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for Schizophrenia in Chinese Population. Schizophrenia Res. 143, 38–43 (2013).

Kay, S. R., Fiszbein, A. & Opler, L. A. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (Panss) for Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 13, 261–276 (1987).

T.S.L.S.C.T.Y.S.J.Y.J.C.X.L.Q.L.Y.M.W.Z.W.D.H. ZHANG Evaluation of Reliability and Validity of the Chinese Version of Personal and Social Performance Scale in Patients with Schizophrenia. Chin. Ment. Health J. 12, 790–794 (2009).

Pan, Y. Z. et al. A Comparison of Aggression between Patients with Acute Schizophrenia and Mania Presenting to Psychiatric Emergency Services. J. Affect Disord. 296, 493–497 (2022).

R. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (2013).

Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D. & Fried, E. I. Estimating Psychological Networks and Their Accuracy: A Tutorial Paper. Behav. Res. methods 50, 195–212 (2018).

Epskamp, S., Cramer, A. O., Waldorp, L. J., Schmittmann, V. D. & Borsboom, D. Qgraph: Network Visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data. J. Stat. Softw. 48, 1–18 (2012).

Ebrahimirad, B. & Jelodr, G. A Comparative Analysis of Serum Levels of Serotonin, Testosterone and Cortisol in Normal and Aggressive Individuals. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 8, 1399–1406 (2015).

Barrat, A., Barthelemy, M., Pastor-Satorras, R. & Vespignani, A. The Architecture of Complex Weighted Networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101, 3747–3752 (2004).

Newman, M. E. Analysis of Weighted Networks. Phys. Rev. E 70, 056131 (2004).

Isvoranu, A.-M. et al. Toward Incorporating Genetic Risk Scores into Symptom Networks of Psychosis. Psychological Med. 50, 636–643 (2020).

Epskamp, S., Cramer, A. O. J., Waldorp, L. J., Schmittmann, V. D. & Borsboom, D. Qgraph: Network Visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data. J. Stat. Softw. 1, 2012 (2012).

Lai, J. et al. Factors Associated with Mental Health Outcomes among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e203976 (2020).

Zhang, W. R. et al. Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems of Medical Health Workers During the Covid-19 Epidemic in China. Psychother. Psychosom. 89, 242–250 (2020).

van Borkulo, C.D. et al. Comparing Network Structures on Three Aspects: A Permutation Test. (2017).

Bielecki, M. et al. Impulsivity and Inhibitory Control in Deficit and Non-Deficit Schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 24, 473 (2024).

Caruso, R. et al. Aggressive Behavior and Psychiatric Inpatients: A Narrative Review of the Literature with a Focus on the European Experience. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 23, 29 (2021).

Spector, P. E., Zhou, Z. E. & Che, X. X. Nurse Exposure to Physical and Nonphysical Violence, Bullying, and Sexual Harassment: A Quantitative Review. Int J. Nurs. Stud. 51, 72–84 (2014).

Fazel, S., Gulati, G., Linsell, L., Geddes, J. R. & Grann, M. Schizophrenia and Violence: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med. 6, e1000120 (2009).

Deal, N., Hong, M., Matorin, A. & Shah, A. A. Stabilization and Management of the Acutely Agitated or Psychotic Patient. Emerg. Med Clin. North Am. 33, 739–752 (2015).

Uribe, E. S. et al. Pharmacological Management of Acute Agitation in Psychiatric Patients: An Umbrella Review. BMC Psychiatry 25, 273 (2025).

Yu, Y. et al. Investigating the Shared Genetic Architecture between Schizophrenia and Body Mass Index. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 2312–2319 (2023).

McWhinney, S. R. et al. Obesity and Brain Structure in Schizophrenia - Enigma Study in 3021 Individuals. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 3731–3737 (2022).

Dellazizzo, L. et al. The Psychometric Properties of the Life History of Aggression Evaluated in Patients from a Psychiatric Emergency Setting. Psychiatry Res. 257, 485–489 (2017).

Wang, G. et al. A Randomized, Prospective, Active-Controlled Study Comparing Intramuscular Long-Acting Paliperidone Palmitate Versus Oral Antipsychotics in Patients with Schizophrenia at Risk of Violent Behavior. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 129, 110897 (2024).

Peng, S. X. et al. Dysfunction of Ampa Receptor Glua3 Is Associated with Aggressive Behavior in Human. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 4092–4102 (2022).

Gogos, A., Kwek, P. & van den Buuse, M. The Role of Estrogen and Testosterone in Female Rats in Behavioral Models of Relevance to Schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol. (Berl.) 219, 213–224 (2012).

Nibbio, G. et al. Predictors of Psychosocial Functioning in People Diagnosed with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders That Committed Violent Offences and in Those That Did Not: Results of the Recoviwel Study. Schizophr. Res. 270, 112–120 (2024).

Barlati, S. et al. Cognitive and Clinical Characteristics of Offenders and Non-Offenders Diagnosed with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: Results of the Recoviwel Observational Study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 273, 1307–1316 (2023).

Hamers, I. M. H. et al. The Association of Prolactin and Gonadal Hormones with Cognition and Symptoms in Men with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder: Divergent Effects of Testosterone and Estrogen. Schizophr. Res. 270, 273–280 (2024).

Kanchanatawan, B., Thika, S., Anderson, G., Galecki, P. & Maes, M. Affective Symptoms in Schizophrenia Are Strongly Associated with Neurocognitive Deficits Indicating Disorders in Executive Functions, Visual Memory, Attention and Social Cognition. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 80, 168–176 (2018).

Suetani, S. et al. Impairments in Goal-Directed Action and Reversal Learning in a Proportion of Individuals with Psychosis. Cogn. Affect Behav. Neurosci. 22, 1390–1403 (2022).

Calegaro, V. C. et al. Aggressive Behavior During the First 24 h of Psychiatric Admission. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 36, 152–159 (2014).

Vivas, A. B., Hussain-Showaiter, S. M. & Overton, P. G. Schizophrenia Decreases Guilt and Increases Self-Disgust: Potential Role of Altered Executive Function. Appl Neuropsychol. Adult 30, 447–457 (2023).

Keen, N., George, D., Scragg, P. & Peters, E. The Role of Shame in People with a Diagnosis of Schizophrenia. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 56, 115–129 (2017).

Borrelli, D. F., Ottoni, R., Maffei, S., Marchesi, C. & Tonna, M. The Role of Shame in Schizophrenia Delusion: The Interplay between Cognitive-Perceptual and Emotional Traits. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 211, 369–375 (2023).

Carré, J. M. & Olmstead, N. A. Social Neuroendocrinology of Human Aggression: Examining the Role of Competition-Induced Testosterone Dynamics. Neuroscience 286, 171–186 (2015).

Eisenegger, C., Haushofer, J. & Fehr, E. The Role of Testosterone in Social Interaction. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 263–271 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by National Clinical Key Specialty Construction Project in 2022 (Emergency Psychiatry Department Fund 3-2-2021-PT40).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: M.-h.Z., X.-m.X. Administrative support: X.J., Y.-F.W. Provision of study materials or patients: J.Z., Y.L., T.H. and J.L. Collection and assembly of data: Y.-F.W., Y.L., T.H., and J.L. Data analysis and interpretation: M.-h.Z., X.-m.X., C.H. Manuscript writing: All authors. Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, MH., Zhang, J., Cai, H. et al. Mapping aggressive behaviors and testosterone among schizophrenia patients in acute stage. Schizophr 11, 157 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00702-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00702-1