Abstract

Antipsychotic-induced weight gain (AIWG) exhibits marked heterogeneity. We conducted a secondary analysis of the Chinese First-Episode Schizophrenia Trial, leveraging frequent body mass index (BMI) measurements over 12 months. Our aims were to identify latent BMI trajectories in first-episode schizophrenia (FES) patients treated with second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and to explore predictors of trajectory membership. Subjects in this study were from the Chinese First-Episode Schizophrenia Trial (CNFEST). After quality control, a total of 361 drug-naïve FES patients treated with olanzapine, risperidone, or aripiprazole were included. BMI was measured at 7 timepoints over 12 months. Latent class trajectory modeling (LCTM) was used to identify distinct BMI trajectories. Multinomial logistic regression was applied to detect predictors of trajectory membership. Four BMI trajectories were emerged, including Low Baseline BMI with Rapid Increase (LBRI) (6.1%, +3.5kg/m² within the first 3 months), Moderate Baseline BMI with Gradual Increase (MBGI) (33.8%, steady rising during 9 months), and Low/High Baseline BMI with Slight Increase (LBSI/HBSI) (46%/14.1%, Minimal change (<1.5 kg/m²)). Baseline BMI (χ² = 144.5, p < 0.001) was the strongest predictor of the LBRI trajectory. A numerically higher, though not statistically stable, odds were observed for olanzapine vs. aripiprazole (OR = 20.4, 95% CI = 2.48–166.67). Shorter duration of untreated psychosis (DUP < 1 year) (OR = 4.12, 95% CI = 1.31–12.93) and lower education (OR = 5.40, 95% CI = 1.19–24.52) further increased LBRI risk. A high-risk subgroup (LBRI) with rapid early weight gain was identified, driven by olanzapine use, shorter DUP, and lower educational attainment. These findings advocate for dynamic risk stratification and early preventive interventions in vulnerable FES patients (Trial Registration: This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT01057849) on January 26, 2010).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schizophrenia, affecting approximately 0.7% of the global population1, reduces life expectancy by over a decade2, and imposes profound personal and societal burden3,4. While second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) remain the primary pharmacological intervention for schizophrenia, their metabolic adverse effects, particularly antipsychotic-induced weight gain (AIWG), significantly lead to cardiovascular morbidity and premature mortality5. Notably, 40.9% of patients with first-episode schizophrenia (FES) meet the criteria for metabolic syndrome (MetS) at treatment initiation6, a risk amplified by SGAs-induced rapid weight gain7.

AIWG exhibits marked heterogeneity in both the rate of onset and overall extent of weight gain. Our prior analysis of FES patients revealed that 79% experienced ≥7% weight gain within the first year of treatment, yet trajectories diverged substantially across individuals and antipsychotics8. To date, only one study has systematically characterized AIWG subtypes. Four distinct subtypes have been proposed, namely rapid gainers, gradual gainers, transit gainers, and non-gainers9. However, emerging evidence indicates that real-world metabolic risks may be underestimated for rapid gainers10. Furthermore, AIWG-driven treatment nonadherence and relapse risks are exacerbated in rapid gainers, suggesting this subgroup bears disproportionate metabolic risks11.

Despite these insights, current clinical guidelines remain trajectory-agnostic. The American Psychiatric Association schizophrenia guidelines recommend routine metabolic monitoring without specifying thresholds or interventions for high-risk subgroups12. This one-size-fits-all approach leaves rapid gainers, a minority with outsized metabolic burden, under-screened and undertreated. Traditional analyses averaging group-level changes fail to obscure critical temporal patterns. For instance, early rapid weight gain strongly predicts long-term metabolic deterioration13, yet such dynamic patterns are invisible in mean-based models. Identifying distinct AIWG trajectories could pinpoint critical intervention windows and inform personalized strategies—a pressing need given that behavioral interventions are most effective when timed to trajectory inflection points14.

Although promising, trajectory analysis has been infrequently applied to AIWG in schizophrenia. Existing predictors (e.g., baseline BMI15, antipsychotic type16) are derived from static comparisons, neglecting temporal dynamics. To address this gap, we conducted a secondary analysis of the Chinese First-Episode Schizophrenia Trial (CNFEST), leveraging frequent BMI measurements over 12 months. Our aims were to identify latent BMI trajectories in FES patients treated with SGAs, and to explore predictors of trajectory membership, informing early risk stratification.

Results

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the study participants were summarized in Table 1. The average age of participants was 25.14 years, with a balanced gender distribution. Most participants (63.64%) had completed fewer than 12 years of education. The mean age of psychosis onset was 24.44 years, and over half had experienced a duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) exceeding one year. Participants presented with substantial clinical severity, as indicated by a mean Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) total score of 85.94 ± 14.56, and marked impaired social functioning, reflected by a mean Personal and Social Performance scale (PSP) score of 42.01 ± 12.57. BMI distribution revealed that 65.7% of participants were of normal weight, 18.6% were underweight, and 15.8% were overweight.

Trajectory analysis of BMI over time

A total of 363 FES patients were included in weight gain trajectory modeling. A suitable and well-fitting model for weight gain could not be ascertained based on BIC and AvePP criteria (Supplementary Table 1). Subsequent analyses, therefore, focused on BMI trajectories. After excluding two participants with missing baseline height data, the final analysis included 361 participants. The 4-group trajectory model was selected as optimal, demonstrating the lowest BIC and all posterior probabilities exceeding 0.7 (Table 2). Four distinct BMI trajectories were identified, including Low Baseline BMI with Slight Increase group (LBSI, 46%, n = 166), Moderate Baseline BMI with Gradual Increase group (MBGI, 33.8%, n = 122), High Baseline BMI with Slight Increase group (HBSI, 14.1%, n = 51), and Low Baseline BMI with Rapid Increase group (LBRI. 6.1%, n = 22) (Fig. 1).

To evaluate the robustness of these findings to missing data (Supplementary Table 2), we conducted sensitivity analyses. Little’s MCAR test indicated that BMI data were not missing completely at random (p < 0.001). We subsequently performed the Multilevel Multiple Imputation method, generating five imputed datasets. Pooled analyses of imputed datasets revealed a significant, stable increase in BMI over time. Sensitivity analyses under both MAR and MNAR assumptions showed remarkable consistency in BMI estimates (differences <0.5%), confirming robustness to missing data mechanisms17. Critically, the averaged trajectories derived from the imputed datasets showed consistent distribution and shape patterns with the primary analysis presented in Fig. 1 across all four trajectory classes, reinforcing the reliability of the identified subgroups.

Statistically significant differences were observed among the groups in age, DUP, antipsychotic type, baseline PSP scores, baseline BMI, and BMI categories (all p < 0.05). Specifically, participants in the HBSI group were significantly older than those in the other three groups. Most participants in the LBRI group had a DUP of less than one year. Over 70% of participants in the LBRI group were treated with olanzapine. Baseline social functioning, as measured by the PSP, also differed significantly, with the LBSI group showing the lowest scores and the HBSI group demonstrating the highest. Although educational attainment did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.076), a notably high percentage of participants in the LBRI group (86.36%) had completed fewer than 12 years of education. Despite observed variations in gender distribution across trajectory subgroups (e.g., 56.86% female in HBSI vs. 40.91% in LBRI), formal likelihood ratio testing confirmed that gender was not a statistically significant predictor of trajectory membership (χ² = 2.78, df = 3, p = 0.427) (Supplementary Table 3).

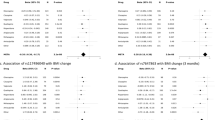

Analysis of determinants for BMI trajectories

Multivariate multinomial logistic regression identified baseline BMI (χ2 = 144.46, df = 3, p < 0.001) and antipsychotic type (χ2 = 35.19, df = 6, p < 0.001) as the key determinants of BMI trajectory membership, with DUP (χ2 = 8.99, df = 3, p = 0.029) and baseline PSP scores (χ2 = 9.07, df = 3, p = 0.028) also contributing significantly. Olanzapine use was independently associated with BMI increase across trajectories, showing a particularly strong association with membership in the LBRI group compared with aripiprazole (OR = 20.41, 95% CI: 2.48–166.67). A DUP of less than one year was associated with 4.12-fold higher odds of belonging to the LBRI group compared to a longer DUP (95% CI: 1.31–12.93, p = 0.015). Furthermore, baseline PSP scores were significantly higher in the MBGI and HBSI groups than in the LBSI group (both p < 0.05, Table 3).

Given the small size of the LBRI group (n = 22), we performed a bootstrap resampling analysis (1000 replicates) to assess the stability of these predictor estimates. This sensitivity analysis revealed a substantial attenuation in the point estimate for the association between olanzapine (vs. aripiprazole) and LBRI membership (OR = 1.62, 95% CI: 0.52–5.27), suggesting that the strength of this association in the primary analysis should be interpreted with caution.

Given overlapping yet distinct clinical profiles between the MBGI and LBRI groups, we further conducted a binary logistic regression to delineate factors distinguishing the two trajectories (Table 4). After adjusting for baseline BMI, both lower educational attainment(<12 years; OR = 5.398, 95% CI: 1.19–24.52, p = 0.029) and a shorter DUP (<1 year; OR = 4.43, 95% CI: 1.20–16.38, p = 0.026) were independently associated with membership in the LBRI trajectory. Notably, the antipsychotic regimen did not significantly differ between the two groups, suggesting rapid weight gain in the LBRI group might be primarily driven by non-pharmacological factors.

Discussion

This was the first large-scale study to delineate BMI trajectories and their predictors in FES patients initiating SGA treatment. Four distinct trajectories were identified, including the Low Baseline BMI with Rapid Increase (LBRI) subgroup (6.1%) exhibiting steep early weight

gain (+3.5 kg/m² within 3 months), the Moderate Baseline BMI with Gradual Increase (MBGI) subgroup (33.8%) experiencing steady increase over 9 months, and the Low/High Baseline BMI with Slight Increase (LBSI/HBSI) subgroup (46% and 14.1%) demonstrating minimal elevation (<1.5 kg/m²) throughout the follow-up. Baseline BMI, antipsychotic type (particularly olanzapine), shorter DUP (<1 year), and impaired baseline social functioning were identified as independent predictors associated with trajectory membership. These findings advanced our understanding of AIWG in schizophrenia by uncovering dynamic risk patterns in drug-naïve patients, revealing temporally heterogeneous risk factors, and providing actionable insights for personalized prevention strategies.

The LBRI trajectory, observed in 6.1% of participants, aligned with the high-risk subgroup in pediatric cohorts, where rapid early weight gain predicted long-term metabolic dysfunction9. Over 70% of LBRI participants received olanzapine, consistent with its well-documented hypermetabolic profile16. In our primary analysis, olanzapine was associated with a substantially elevated likelihood of LBRI membership compared to aripiprazole. While this observed effect size was numerically larger than some prior estimates (OR = 4–6)18,19, it is important to note the instability of this estimate in the context of the small LBRI subgroup, as indicated by our sensitivity analysis. The pronounced weight gain in this subgroup may reflect the convergence of a potent pharmacological agent with the heightened metabolic vulnerability inherent to FES patients20,21. Antipsychotic-naïve FES patients exhibited neuroendocrine dysregulation, including hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hyperactivity and insulin resistance, which predisposed them to weight gain even before antipsychotic initiation22,23. Furthermore, olanzapine has been shown to disrupt gut microbiota composition and suppress brown adipose tissue thermogenesis, mechanisms linked to accelerated weight gain24,25. The interplay between pre-existing biological susceptibility and pharmacological effects likely contributes to rapid metabolic deterioration in this vulnerable population. Therefore, we propose LBRI-subgroup targeted interventions with reference to existing psychiatric cardiometabolic management guidelines26. For LBRI patients treated with olanzapine, we recommend early, intensive metabolic monitoring. Specifically, BMI measurements every 2 weeks in the first 3 months of antipsychotic initiation (to capture rapid weight gain) and monthly assessments of fasting blood glucose/lipids (per standard metabolic monitoring protocols). This ensures the timely detection of cardiometabolic risks unique to LBRI’s rapid weight gain pattern.

Contrary to studies linking longer DUP to worse outcomes27,28, our findings suggested that a shorter DUP (<1 year) was associated with rapid weight gain in FES patients, aligning with emerging mechanistic insights. An acute psychotic episode might establish a “metabolic primed state” hypersensitive to antipsychotic effects through elevated cortisol, impaired insulin sensitivity, and adipocyte metabolism22,29. Furthermore, shorter DUP corresponded to earlier exposure to antipsychotics, whose sedating effects could reduce physical activity while stimulating appetite30. Our prior analysis demonstrated that FES patients treated with olanzapine exhibited significant BMI increases within first 4 weeks8. Critically, this pharmacologically driven reduction in energy expenditure likely interacts with lifestyle factors, such as sedentary behaviors and dietary patterns, which we were unable to account for in our analysis. This interplay might represent a key mechanism underlying the rapid weight gain observed in the LBRI subgroup.

Additionally, the association between lower educational attainment and impaired baseline social functioning, along with membership in the LBRI subgroup, underscored the critical role of socioeconomic determinants in shaping metabolic risk trajectories. Socioeconomic disadvantages, i.e., poor premorbid adjustment, social isolation, employment instability, and economic hardship, compromised patients’ health management capacity and perpetuate barriers to accessing nutritious diets, regular physical activity, and timely healthcare31,32,33,34,35. Our study, while not directly measuring diet and exercise, highlighted that these socioeconomic factors were potent proxies for such lifestyle risks. Such disadvantages may exacerbate neurocognitive deficits, indirectly promoting greater weight gain in vulnerable individuals36. While antipsychotic type (e.g., olanzapine) remained a primary biological driver of rapid weight gain, the lack of significant differences in antipsychotic prescriptions between the MBGI and LBRI subgroups suggested that rapid weight gain might arise from synergies between biological susceptibility and socioeconomic status (SES) vulnerabilities. This is supported by prospective evidence linking low SES to a 3.1-fold higher risk of metabolic syndrome and a 0.86 kg/m² greater BMI increase within 6 months, with Mendelian randomization suggesting a causal effect of education on BMI in high-risk medication users37.

Our study had several strengths, including the use of frequent body weight measurements (7 timepoints over 12 months) in a well-characterized FES cohort, rigorous trajectory modeling with objective fit indices, and exploration of both biological and social predictors. However, several limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, the relatively small sample size of the LBRI subgroup (n = 22) is a notable limitation. This constrains statistical power, potentially precluding detection of weak-effect predictors, leading to imprecise effect estimates (e.g., wide confidence intervals for odds ratios), and restricting subgroup-specific analyses. Predictors for this trajectory thus require cautious interpretation, as supported by our bootstrap resampling analysis showing attenuated associations. Second, unmeasured confounders, particularly detailed lifestyle factors, were not available in the present dataset. Emerging evidence highlights that polygenic obesity risk amplifies weight gain in the context of suboptimal lifestyle factors, while health-promoting behaviors can mitigate genetic risk38. Therefore, while our models identified key clinical and socioeconomic factors, the observed risk profiles likely reflect individuals for whom these unmeasured lifestyle factors are particularly salient. Consequently, we propose interventions addressing both biological susceptibility (e.g., early metabolic monitoring of olanzapine-treated patients) and contextual barriers (e.g., subsidized nutrition, community-based exercise initiatives). Future studies incorporating longitudinal assessments of lifestyle, genetic, and pharmacokinetic data, particularly in underrepresented populations, are needed to disentangle these complex relationships and refine risk stratification models. Third, the study is limited by missing BMI data. Patients with significant rapid weight gain (who would likely fall into the LBRI trajectory) may be lost to follow-up, potentially underestimating the severity and prevalence of this high-risk subgroup. To address this, we conducted rigorous sensitivity analyses. Consistent core trajectories across imputed datasets confirm the robustness. However, even advanced imputation cannot fully adjust for unmeasured confounding bias under MNAR, highlighting the need for targeted retention strategies for high-risk individuals in future prospective studies. Fourth, we did not assess genetic variations modulating weight regulation and antipsychotic response, including polygenic risk scores for obesity, polymorphisms in genes involved in energy homeostasis (e.g., FTO, MC4R)39. These genetic factors can predispose individuals to differential susceptibility to weight gain, and their absence may lead to overestimation of socioeconomic factors’ (e.g., educational attainment) effects on weight gain trajectories. The lack of genetic data precluded us from accounting for their potential confounding effects or exploring gene-environment interactions that may influence trajectory outcomes. Last but not least, our study’s generalizability is limited by including only Chinese patients. While this enhances internal validity for this understudied group, it restricts extending findings to other cultural backgrounds. Specifically, ethnic differences in antipsychotic metabolism genes (CYP1A2, CYP2D6), dietary norms, and physical activity attitudes, all tied to weight gain trajectories, may influence result variability.

Conclusion

In this trajectory analysis of BMI changes in FES patients, we identified a high-risk subgroup (LBRI) characterized by rapid early weight gain, olanzapine use, and socioeconomic disadvantage. These findings challenge the one-size-fits-all metabolic monitoring paradigm. To translate these findings into clinical practice, we advocate for LBRI-targeted dynamic risk stratification and intervention. Implement stratified interventions aligned with its key features, e.g., biweekly BMI monitoring for olanzapine-treated LBRI patients (especially those with DUP < 1 year) to preempt excessive weight gain and integrated support (free dietary counseling and subsidized nutrition) for LBRI patients with socioeconomic barriers. Extend this trajectory-informed approach to refine metabolic monitoring protocols, shifting from universal surveillance to risk-adapted care for FES patients. Future studies are critical to validating these interventions, specifically, testing preemptive behavioral interventions for LBRI populations and integrating multi-omics data to identify biological markers of LBRI susceptibility. These efforts are critical to reducing the cardiometabolic burden of schizophrenia treatment in this high-risk subgroup.

Methods

Participants

The Chinese First-Episode Schizophrenia Trial (CNFEST) was a multicenter, randomized, open-label clinical study conducted across six psychiatric hospitals in China40. Participants aged 18–45 years met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia diagnosis via the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorder (SCID-I/P)41, with symptom onset after age 15. Eligible participants were experiencing their first episode (illness duration <3 years, cumulative antipsychotic exposure <12 weeks). Exclusion criteria included substance abuse, severe medical conditions, the use of regular concomitant medications (e.g., corticosteroids, mood stabilizers), prior long-acting antipsychotic injections, or contraindications to olanzapine, risperidone, or aripiprazole. This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University Sixth Hospital. All participating centers operated under this approval, with site-specific registrations completed where required. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. Given the psychiatric nature of the study, particular attention was paid to evaluating each participant’s capacity for informed decision-making. In cases where individuals could not provide consent independently, consent was obtained from legally authorized representatives following applicable ethical and legal standards. The CNFEST trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01057849) on January 26, 2010.

Medication protocol and assessments

Participants were randomized to aripiprazole (5–30 mg/day), risperidone (1–6 mg/day), or olanzapine (5–20 mg/day) group using stratified block randomization (stratified by study site). Doses were adjusted based on efficacy and tolerability within predefined ranges. In the original CNFEST, participants were permitted to switch their medication once within the first 4 weeks. Only those who maintained initial treatment and completed at least one follow-up assessment were included in this analysis. Concomitant medications (e.g., benzhexol for extrapyramidal symptoms) were allowed at standardized doses if necessary.

Clinical assessments were conducted by well-trained psychiatrists independent of treatment teams and blinded to medication allocation to minimize bias. A standardized case report form was used to collect demographic and clinical data. The duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) was defined as the interval between the first onset of psychotic symptoms and the initiation of antipsychotic treatment, determined through triangulation of patient/family interviews, medical records, and clinical judgment. Psychopathology was evaluated using the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS)42 and the Clinical Global Impression (CGI)43, while social functioning was assessed via the Personal and Social Functioning Scale (PSP)44. Clinical assessments were conducted at baseline (T0), and at 1 (T1), 2 (T2), 3 (T3), 6 (T4), 9 (T5), and 12 months (T6). Physical examinations (including height measurement) were performed at baseline and study completion. Body weight was measured at all timepoints using calibrated scales with participants in light clothing after overnight fasting. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m²).

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed in R (version 4.3.2) and SPSS (version 26). Distinct weight and BMI trajectories were identified using latent class category trajectory modeling (LCTM) in R.Model selection was guided by the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), with additional consideration of the average posterior probability (AvePP > 0.70), and a minimum class size exceeding 2% of the sample45. Nonlinear trajectories were tested via quadratic polynomial terms to account for potential curvature in outcome changes over time. To address missing BMI data, Little’s MCAR test was first performed to examine the missingness mechanism. As the result indicated the data were missing not at random (MNAR), multiple imputation was implemented using the MICE package in R with the Multilevel Multiple Imputation method, generating five imputed datasets. The robustness of the identified trajectories to missing data was subsequently evaluated through sensitivity analyses comparing results from the original and imputed datasets. For baseline characteristics with missing values, a complete-case approach was applied. Between-trajectory subgroup differences in continuous and categorical baseline characteristics were assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis H-test and Pearson’s chi-square test, respectively. Multinomial logistic regression models were employed to identify predictors of trajectory membership. To assess the stability of the odds ratio (OR) estimates from the regression model, a bootstrap resampling procedure with 1000 iterations was performed. Significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University Sixth Hospital. All participating centers operated under this approval, with site-specific registrations completed where required. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Owen, M. J., Sawa, A. & Mortensen, P. B. Schizophrenia. Lancet 388, 86–97 (2016).

Weye, N. et al. Association of specific mental disorders with premature mortality in the Danish population using alternative measurement methods. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e206646 (2020).

Attepe Özden, S., Tekindal, M. & Tekindal, M. A. Quality of life of people with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Int J. Soc. Psychiatry 69, 1444–1452 (2023).

Kotzeva, A., Mittal, D., Desai, S., Judge, D. & Samanta, K. Socioeconomic burden of schizophrenia: a targeted literature review of types of costs and associated drivers across 10 countries. J. Med. Econ. 26, 70–83 (2023).

Shin, J. A. et al. Metabolic syndrome as a predictor of type 2 diabetes, and its clinical interpretations and usefulness. J. Diab. Investig. 4, 334–343 (2013).

McEvoy, J. P. et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr. Res. 80, 19–32 (2005).

Scaini, G. et al. Second generation antipsychotic-induced mitochondrial alterations: implications for increased risk of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 28, 369–380 (2018).

Zhou, T. et al. Weight changes following treatment with aripiprazole, risperidone and olanzapine: a 12-month study of first-episode schizophrenia patients in China. Asian J. Psychiatr. 84, 103594 (2023).

Lyu, N. et al. Trajectories and predictors for the development of clinically significant weight gain in children and adolescents prescribed second-generation antipsychotics. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 34, 201–209 (2024).

Correll, C. U. et al. Weight gain and metabolic changes in patients with first-episode psychosis or early-phase schizophrenia treated with olanzapine: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 26, 451–464 (2023).

Leucht, S. et al. Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 379, 2063–2071 (2012).

Keepers, G. A. et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 177, 868–872 (2020).

Solmi, M. et al. Risk factors, prevention and treatment of weight gain associated with the use of antidepressants and antipsychotics: a state-of-the-art clinical review. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 23, 1249–1269 (2024).

Chang, S. C., Goh, K. K. & Lu, M. L. Metabolic disturbances associated with antipsychotic drug treatment in patients with schizophrenia: state-of-the-art and future perspectives. World J. Psychiatry 11, 696–710 (2021).

Eder, J. et al. Who is at risk for weight gain after weight-gain associated treatment with antipsychotics, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers: a machine learning approach. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 151, 231–244 (2025).

Pillinger, T. et al. Comparative effects of 18 antipsychotics on metabolic function in patients with schizophrenia, predictors of metabolic dysregulation, and association with psychopathology: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 64–77 (2020).

Sterne, J. A. et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 338, b2393 (2009).

Spertus, J., Horvitz-Lennon, M., Abing, H. & Normand, S. L. Risk of weight gain for specific antipsychotic drugs: a meta-analysis. NPJ Schizophr. 4, 12 (2018).

Komossa, K., Depping, A. M., Gaudchau, A., Kissling, W. & Leucht, S. Second-generation antipsychotics for major depressive disorder and dysthymia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, CD008121 (2010).

Stogios, N., Humber, B., Agarwal, S. M. & Hahn, M. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain in severe mental illness: risk factors and special considerations. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 25, 707–721 (2023).

Perry, B. I., McIntosh, G., Weich, S., Singh, S. & Rees, K. The association between first-episode psychosis and abnormal glycaemic control: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 1049–1058 (2016).

Pillinger, T. et al. Impaired glucose homeostasis in first-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 261–269 (2017).

Guest, P. C., Martins-de-Souza, D., Vanattou-Saifoudine, N., Harris, L. W. & Bahn, S. Abnormalities in metabolism and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in schizophrenia. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 101, 145–168 (2011).

Qian, L. et al. Longitudinal gut microbiota dysbiosis underlies olanzapine-induced weight gain. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0005823 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Olanzapine induces weight gain in offspring of prenatally exposed poly I: C rats by reducing brown fat thermogenic activity. Front. Pharm. 13, 1001919 (2022).

Perry, B. I., Mitchell, C., Holt, R. I., Shiers, D. & Chew-Graham, C. A. Lester positive cardiometabolic resource update: improving cardiometabolic outcomes in people with severe mental illness. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 73, 488–489 (2023).

Salazar de Pablo, G. et al. Duration of untreated psychosis and outcomes in first-episode psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis of early detection and intervention strategies. Schizophr. Bull. 50, 771–783 (2024).

Howes, O. D. et al. The clinical significance of duration of untreated psychosis: an umbrella review and random-effects meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 20, 75–95 (2021).

Misiak, B. et al. A meta-analysis of blood and salivary cortisol levels in first-episode psychosis and high-risk individuals. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 62, 100930 (2021).

Bak, M., Drukker, M., Cortenraad, S., Vandenberk, E. & Guloksuz, S. Antipsychotics result in more weight gain in antipsychotic naive patients than in patients after antipsychotic switch and weight gain is irrespective of psychiatric diagnosis: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 16, e0244944 (2021).

Swanson, C. L. et al. Premorbid educational attainment in schizophrenia: association with symptoms, functioning, and neurobehavioral measures. Biol. Psychiatry 44, 739–747 (1998).

Atkinson, J. M., Coia, D. A., Gilmour, W. H. & Harper, J. P. The impact of education groups for people with schizophrenia on social functioning and quality of life. Br. J. Psychiatry 168, 199–204 (1996).

Hakulinen, C. et al. The association between early-onset schizophrenia with employment, income, education, and cohabitation status: nationwide study with 35 years of follow-up. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 54, 1343–1351 (2019).

Tesli, M. et al. Educational attainment and mortality in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 145, 481–493 (2022).

Ren, Z. et al. An exploratory cross-sectional study on the impact of education on perception of stigma by Chinese patients with schizophrenia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 16, 210 (2016).

Ma, K. et al. The bidirectional relationship between weight gain and cognitive function in first-episode schizophrenia: a longitudinal study in China. Brain Sci. 14, 310 (2024).

Dubath, C. et al. Socio-economic position as a moderator of cardiometabolic outcomes in patients receiving psychotropic treatment associated with weight gain: results from a prospective 12-month inception cohort study and a large population-based cohort. Transl. Psychiatry 11, 360 (2021).

Kim, M. S. et al. Association of genetic risk, lifestyle, and their interaction with obesity and obesity-related morbidities. Cell Metab. 36, 1494–1503.e3 (2024).

Zhang, J. P. et al. Pharmacogenetic associations of antipsychotic drug-related weight gain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 42, 1418–1437 (2016).

Han, X. et al. The Chinese first-episode schizophrenia trial: background and study design. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 24, 169–173 (2014).

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M. & Williams J. B. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). (Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1994).

Kay, S. R., Fiszbein, A. & Opler, L. A. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 13, 261–276 (1987).

Busner, J. & Targum, S. D. The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry 4, 28–37 (2007).

Tianmei, S. et al. The Chinese version of the Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP): validity and reliability. Psychiatry Res. 185, 275–279 (2011).

Mirza, S. S. et al. 10-year trajectories of depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: a population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 628–635 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Fund China (No.82171500); the Key Program of Beijing Science and Technology Commission (No.D171100007017002); the Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research (CFH, No.2018-4-4116); Beijing Municipal Health Commission Research Ward Program (3rd batch).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Y. analyzed the data, drafted the initial manuscript, and carried out subsequent revisions. T.Z. substantially revised the initial draft, refining the argumentation and enhancing the clarity of problem analysis. B.H. provided critical input regarding the methodology and logical structure of the manuscript. Z.L. contributed to data analysis. T.G., X.G., W.H., Y.J., X.W., and Y.Z. contributed to data collection. The corresponding authors, X.Y. and C.P., provided further revisions and overall guidance. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, X., Zhou, T., Huang, B. et al. Trajectory analysis of BMI increase induced by second-generation antipsychotics in first-episode schizophrenia: a secondary analysis based on CNFEST****. Schizophr 12, 7 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00710-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00710-1