Abstract

Pathogens detection is a crucial measure in the prevention of foodborne diseases. This study developed a novel multicolor colorimetric assay to visually detect Salmonella Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium), by utilizing the etching process of gold nanorods (AuNRs) with TMB2+. The strategy involved the construction of nanozyme by assembling magnetic covalent organic framework (MCOF) with aptamer-conjugated AuNPs (Apt-AuNPs), exhibiting remarkable peroxidase-like activity to catalyze the oxidation of TMB/H2O2 and inducing the etching of AuNRs. The presence of S. Typhimurium could inhibit this process, resulting in the generation of vivid colors. The multicolor colorimetric assay could specifically determine S. Typhimurium from 102 to 108 CFU mL−1 in 60 min with visual detection limit of 102 CFU mL−1, and instrumental detection limit of 2.3 CFU mL−1. Moreover, detecting S. Typhimurium in chicken, milk, pork and lettuce samples has shown promise in practical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 600 million individuals suffer from illnesses caused by foodborne pathogens annually, leading to ~420,000 fatalities. The rise of pathogen-induced foodborne diseases has sparked growing concerns about public health and economic development, making it a pressing global issue1. Salmonella Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) stands out as a predominant foodborne pathogen, with data revealing that it frequently ranks highest in cases of bacterial food poisoning globally2. Due to the absence of any noticeable changes in flavor or appearance of S. Typhimurium-contaminated food, and the minimal infectious concentration of S. Typhimurium in vulnerable populations3,4,5, it is of great importance to screen S. Typhimurium to prevent the outbreak of foodborne diseases and guarantee food safety. Conventional detection techniques including standard plate count, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) have the advantages of accuracy and specificity, but suffer from the drawbacks of requirements of laborious procedures, skilled personnel or expensive equipment, rendering these approaches unsuitable for the on-site detection6. Therefore, the construction of facile and sensitive assays for the detection of S. Typhimurium is urgently demanded. In view of this, colorimetric methods have emerged as a viable option for on-site detection due to their portability, ease of visual observation7,8.

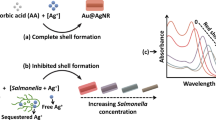

Because of the constraints of monochromatic resolution in traditional colorimetry, the utilization of multicolor signals enables enhancements in both the accuracy and sensitivity of visual detection9. Various of novel nanomaterials including gold nonorods (AuNRs), gold nanobipyramids (AuNBPs)10, gold nanostars (AuNSs)11 and silver nanoplates (AgNPls)12 have been reported as multicolor substrates for colorimetric assays. AuNRs is prevalent due to their adjustable longitudinal localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) band and high extinction coefficients. The alteration of the aspect ratio of AuNRs can result in a shift in the longitudinal LSPR band, leading to the attainment of visually detectable vivid colors13,14. This can be accomplished through processes such as etching15 or silver deposition16. And our group’s previous work has made progress in colorimetric approaches by utilizing the etching of AuNRs mediated by MnO2 NPs nanozyme to achieve the multicolor quantitative analysis of foodborne bacteria, demonstrating that AuNRs-based visual assays with simplified readout is full of opportunities13,17. Nonetheless, the MnO2 NPs mentioned above still encounter issues related to their low stability due to their susceptibility to decomposition in matrices containing reducing substances, thereby complicating the pretreatment of samples18,19.

Covalent organic framework (COF) stands out as a promising category of porous organic materials exhibiting crystalline and periodic structure. Their high porosity and large surface areas lead to an innovative direction for constructing ideal supporting substrates for metal nanocatalysts to enhance their stability and catalytic performance20,21,22. For instance, Lu et al.23 reported that ultrafine Pt NPs and Pd NPs supported on a thioether-containing COF exhibited outstanding catalytic performance in the reduction of nitrophenol and the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction. Wu et al.24 presented findings that bimetallic Cu/Ag nanoparticles supported on a COF displayed enhanced catalytic activity in the reduction of p-nitrophenol. Moreover, the COF-supported nanocatalyst as mentioned above demonstrated good stability and reusability. However, as the recognition molecules has not been introduced, there are some limitations to the specific detection of target in the existing studies. Notably, benefiting from the robust π-electron system and a planar structure, COF could adsorb ssDNA via π–π stacking and hydrogen-bonding interaction. Gao et al.25 prepared two porphyrin COF-DNA “off–on” nanoprobes for simultaneous imaging of intracellular tumor-associated mRNAs. Cui et al.26 constructed a sensitive and selective fluorescent turn-on aptasensor for detection of VEGF165 based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer between porphyrin-based COF and aptamer-conjugated carbon dots. This provides new ideas for target-regulated and nucleic acid facilitated-self-assembly of COF and metal nanocatalyst. Here, COF serve dual roles: serving as substrates for immobilizing the nanoprobe for specific analysis and functioning as enhancers for nanocatalysts to boost detection signals. However, such studies have rarely been reported. In addition, it is challenging to separate COF from the matrix due to its intrinsic lightweight, being an obstacle for further application27. Fortunately, magnetic covalent organic framework (MCOF) can make up for this shortcoming, where magnetic nanoparticles serve as the core with COF growth on the surface, integrating the merits of high paramagnetism and superior adsorption capacity. Thus, MCOF are acknowledged as promising candidates for the fabrication of recyclable COF-based self-assembled nanocomposites.

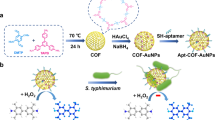

Inspired by the above considerations, a novel multicolor colorimetric assay for S. Typhimurium detection was constructed based on target-inhibited MCOF-Apt-AuNPs self-assembly and the etching of AuNRs (Fig. 1). MCOF-Apt-AuNPs nanozyme with peroxidase-mimicking activity could catalyze the oxidation of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB), resulting in the generation of TMB2+ as an etching agent. This facilitated the gradual etching process of AuNRs, inducing observable alterations in color and blue shift in LSPR. However, the target of S. Typhimurium could inhibit the self-assembly process and prevent AuNRs from etching with opposite multicolor changes. Hence, by evaluating the etching degree of AuNRs at various concentrations of S. Typhimurium, a multicolor visual assay was successfully developed, which was further applied to sense S. Typhimurium in milk, chicken, pork and lettuce samples. Such a target-inhibited self-assembly of nanozyme-based multicolor colorimetric assay offers a vivid example of simple, rapid, sensitive and on-site detection of foodborne pathogens and holds great promise in food safety.

Results

Fabrication and characterizations of nanomaterials

For the synthesis of the MCOF, Fe3O4 NPs were first prepared as the core via hydrothermal method, and the homogeneous COF shell was grown on the surface of Fe3O4 NPs via Schiff base reaction with 1,3,5-tris (4-aminophenyl) benzene (TAPB) and 2,5-dihydroxyterephthalaldehyde (DHTA) as building blocks. The morphologies and structures of MCOF were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM). TEM analysis indicated that the Fe3O4 NPs were uniform with a size of ~230 nm (Fig. 2a). After being coated with the COF layer, the resultant MCOF consisted of isolated particles that featured dark spherical cores and bright uniform COF shells with an average thickness of 106 nm (Fig. 2b). FTIR analysis of MCOF showed that, in comparison with the spectrum of Fe3O4 NPs, the Fe–O vibration at 496–655 cm−1 was retained while a characteristic absorption at 1614 nm−1 appeared, corresponding to the newly formed C=N groups in imine-COF via aldimine condensation (Fig. 2c)28,29. Furthermore, as illustrated in Fig. 2d by the VSM, the superparamagnetic property of Fe3O4 cores contributed to the high magnetic responsiveness of MCOF, enabling rapid separation in just 5 s (inset image).

Validation of hypothesis

The multicolor colorimetric assay involves three main processes: MCOF-Apt-AuNPs self-assembly, target-induced inhibition of self-assembly process, and Au NRs etching-based multicolor signal output.

MCOF-Apt-AuNPs self-assembly

The multi-layered sheets of COF with π–π stacking structures could provide tremendous sites for loading Apt-Au NPs. Apt-AuNPs, with 33–49 nm hydrodynamic diameter (Fig. S1), was decorated on the MCOF to assembled into nanozyme known as MCOF-Apt-AuNPs by simple mixing. The TEM-EDS results revealed that the core-shell structure was evident from the presence of C, N, O and Fe elements. Notably, the Au element was evenly distributed across the entire core-shell architecture, offering additional support for the uniform dispersion of Apt-AuNPs on the MCOF (Fig. 3a). The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectrum also indicated the existence of C, N, O and Au elements (Fig. 3b). And the N1s spectrum could be de-convoluted two peaks assigning to the C=N (399.32 eV) and the residual -NH2 groups (400.91 eV), indicating that the chemical structure of COF remained intact after the introduction of Apt-AuNPs (Fig. 3c). Figure 3d clearly displayed the presence of Au0 4f5/2 (88.86 eV) and Au0 4f7/2 peaks (85.24 eV) in the nanozyme spectra, providing further evidence that Apt-AuNPs were decorated on the surface of MCOF. These findings convincingly demonstrated the excellent binding capacity of MCOF towards Apt-AuNPs for the synthesis of nanozyme.

The peroxidase-mimicking activity of MCOF-Apt-AuNPs nanozyme was evaluated by catalyzing the colorless TMB/H2O2 to generate the yellow oxidized TMB, and the characteristic absorption spectra was measured. In Fig. 4a, the peroxidase activity of Fe3O4 core was first examined, following the addition of Fe3O4 NPs, the colorless TMB/H2O2 solutions (black line) immediately became blue, and turns yellow after the termination of the reaction (red line). However, the addition of MCOF did not result in any observable absorption peak (blue line in Fig. 4a). This indicated that the COF shell had no prominent peroxidase activity, effectively concealing the catalytic capabilities of the Fe3O4 core and mitigating potential background interference. Besides, as expected, Apt-AuNPs could catalyze the oxidation of TMB by H2O2 (green line in Fig. 4b). Following the incubation of Apt-AuNPs with MCOF and subsequent magnetic separation, it was observed that the resultant precipitates demonstrated outstanding catalytic activity (purple line in Fig. 4b). This suggested that the catalytic performance of the nanozyme mainly originated from AuNPs. It is noteworthy that the MCOF served as an ideal framework for anchoring Apt-AuNPs to create a recyclable and stable nanozyme, enabling effective catalysis of the TMB/H2O2 system. Several factors contribute to this: (1) the stability of Au NPs in terms of morphology and catalytic activity is easily influenced by external factors such as pH, temperature and ion concentration. In contrast, MCOF offers a protective framework that effectively maintains the stability of Au NPs and shields AuNPs@apt from external interference30,31. (2) The exceptional magnetic properties of MCOF enable MCOF-AuNPs@apt to be separated from the complex environment and transferred to a more stable catalytic environment, thereby enhancing its catalytic performance. (3) The Apt-AuNPs adsorbed on the MCOF can be removed by ultrasonic method, endowing MCOF with the potential of reusability in subsequent detection processes.

UV–Vis absorption spectra and photographs of different reaction systems: a TMB + H2O2, Fe3O4 NPs + TMB + H2O2 and MCOF + TMB + H2O2; b Apt-AuNPs + TMB + H2O2, MCOF-Apt-AuNPs + TMB + H2O2 and MCOF-Apt-AuNPs + S. Typhimurium + TMB + H2O2. TEM images of c Apt-AuNPs—S. Typhimurium composite in the supernatant of detection system, d MCOF-Apt-AuNPs nanozyme in the precipitates of detection system. Michaelis–Menten curves of the initial velocity with different concentrations of e H2O2 and f TMB as substrate. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three replicates.

Target-induced self-assembly inhibition

It was found that the presence of S. Typhimurium led to an obvious decrease in the catalytic activity of the final precipitates (pink line in Fig. 4b) compared that of no S. Typhimurium (purple line in Fig. 4b). It is speculated that the target might inhibit the self-assembly of MCOF-Apt-AuNPs. Due to the high specificity of the aptamer towards lipopolysaccharide, membrane proteins, or lipoprotein of S. Typhimurium, Apt-AuNPs were mainly attached to S. Typhimurium, with only a small amount binding to MCOF. This preferential recognition resulted in the decrease in the catalytic ability of nanozyme. To investigate the binding abilities of Apt-AuNPs towards S. Typhimurium and MCOF, TEM was used to visualize the interaction between different composites in the precipitate and supernatant. As depicted in the supernatant image of Fig. 4c, the Apt-AuNPs were bound tightly to S. Typhimurium, proving the successful capture of target bacteria. Furthermore, the amount of Apt-AuNPs present on MCOF in the precipitated complex was greatly reduced compared to that in the absence of S. Typhimurium (Figs. 4d vs 3a). These findings validated the greater affinity of Apt-AuNPs towards S. Typhimurium than MCOF, further supporting the aforementioned hypothesis.

To further explore the peroxidase-like activity of the detection system, the steady-state kinetics experiments was performed, and the kinetic parameters and catalytic efficiency were evaluated in terms of maximal reaction velocity (Vmax) and Michaelis–Menten constant (Km)32. Typical Michaelis–Menten curves of MCOF-Apt-AuNPs and MCOF-Apt-AuNPs + S. Typhimurium were obtained in a certain range of TMB or H2O2 concentrations in Fig. 4e, f. As shown in Table 1, the Km of the MCOF-Apt-AuNPs alone for TMB and H2O2 were all lower than that of in the presence S. Typhimurium, and their Vmax values were the opposite. This indicated the higher affinity of MCOF-Apt-AuNPs system towards TMB/H2O2, along with a faster reaction rate and more pronounced reaction extent.

AuNRs etching-based multicolor signal output

Plasmonic AuNRs were served as powerful reporters for multicolor-based colorimetric assays due to their tunable aspect ratio. Ma et al.33 first reported that TMB2+-mediated AuNRs etching strategy, of which TMB2+ functions as a new oxidizing reagent with strong oxidizing capabilities towards AuNRs. The etching process involves the chemical oxidation process of Au(0) within the AuNRs to Au(I) (Eq. (1)), typically occurring at the lateral interfaces of AuNRs33,34. This results in visual signal variations, thus fulfilling the requirements of constructing multicolorimetric assay platforms35.

Given this, various control experiments to elucidate the etching effect of TMB2+ on AuNRs in this study. The different solutions including TMB, H2O2, TMB/H2O2, H+ and TMB+ (product of the oxidation between MCOF-Apt-AuNPs and TMB/H2O2) were introduced into the AuNRs solution. The findings presented in Fig. S2 revealed that none of these solutions showed the ability to etch AuNRs. However, upon the addition of different concentration of TMB2+ generated through the catalytic reaction of MCOF-Apt-AuNPs, TMB/H2O2 and H+, the AuNRs presented a series of vivid color changes from reddish brown, brown, greyish-green, green, olive green, yellow to golden yellow (Fig. 5a, inset images). These alterations were easily noticeable by the naked eye and accompanied with a blue shift in the LSPR band, shifting from 744 to 514 nm (Fig. 5a). The TEM images of Fig. 5b–d revealed the relationship between S. Typhimurium concentration and the etching degree of AuNRs. It was observed that in the detection system, as the concentration of S. Typhimurium decreased, the aspect ratio of the Au NRs exhibited a reduction from 2.04 to 1.41 and eventually to 1.14. These results indicated that S. Typhimurium impeded the etching of AuNRs mediated by the nanozyme catalysis and illustrated the feasibility for the subsequent multicolor signal output of bacteria detection. And all the above feasibility experiments provided ample prerequisites to establish the detection method of pathogenic bacteria.

a UV–Vis absorption spectra and photographs of AuNRs etching system with different concentrations of TMB2+. Representative TEM images of AuNRs during the etching process after incubation with S. Typhimurium at b 108, c 105, d 102 CFU mL−1. The insets showed the colors of the corresponding solutions.

Optimization of experimental conditions

In order to achieve the best performance of detection, the following experimental conditions were optimized, including the volume ratio of MCOF to Apt-AuNPs, the incubation time, the concentration of TMB, the concentration of AuNRs and the volume of “etching solution”. As shown in Figs. S3~S5, the experimental conditions were selected as follows: (a) the volume ratio of MCOF to Apt-AuNPs was 1:2.5, (b) the incubation time was 30 min, (c) the concentration of TMB was 20 mM, (d) the concentration of AuNRs was 0.5 nM, (e) the volume of “etching solution” was 40 μL.

Sensitivity, specificity and reusability

Under the optimal conditions, the performance of the multicolor colorimetric assay was evaluated by testing different concentrations of S. Typhimurium. It was found that various concentrations of S. Typhimurium in the range of 102–108 CFU mL−1 could be easily distinguished at a glance via vivid colors ranging from golden yellow, yellow, brown, tawny, olive green, green, greyish-green to gray and the visual detection limit could be determined as 102 CFU mL−1, showing a noticeable variation in color compared to the control (Fig. 6a). In Fig. 6b, the LSPR peak displayed a progressive red shift as the concentration of S. Typhimurium increased. Correspondingly, Fig. 6c depicted a linear relationship between the longitudinal LSPR peak shift (Δλ) and S. Typhimurium concentrations within the range of 102~108 CFU mL−1, and the regression equation was Δλ = −9.848 lgC + 130.680. The instrumental detection limit was estimated at 2.3 CFU mL−1 based on 3SD/slope (SD represents the standard deviation of blank samples). Comparatively, the colorimetric strategy utilizing the conventional chromogenic agent of TMB displayed a linear range for detecting S. Typhimurium from 103~108 CFU mL−1 with an LOD of 17.9 CFU mL−1 as shown in Fig. S6. The result indicated that the multicolor assay expanded the linear range and enhanced the detection sensitivity. Additionally, as illustrated in Table S1, the proposed assay exhibited a lower or comparable detection limit than certain recently reported sensors (1.8~82 CFU mL−1), indicating that it was acceptable in foodborne bacterial detection performance. This could be attributed to the excellent peroxidase-mimicking performance of the self-assembled nanozyme and the cascade signal amplification involving catalysis and etching. Notably, the unique characteristics of AuNRs resulted in the platform displaying a rainbow-like color variation when exposed to different concentrations of S. Typhimurium, allowing for accurate visual identification without any large and expensive instrument and thus enhancing the feasibility of on-site detection.

Sensitivity results of a S. Typhimurium concentration-dependent color photographs (0, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107 and 108 CFU/mL), b UV–Vis spectra, c the calibration curve for S. Typhimurium (Δλ vs the log scale of the S. Typhimurium concentrations). d Specificity results of the Δλ of AuNRs in response to different analytes (1-Blank, 2-L. monocytogenes, 3-V. parahaemolyticus, 4-S. aureus, 5-E. coli O157:H7, 6-S. Enteritidis, 7-mixture in the absence of S. Typhimurium, 8-S. Typhimurium, 9-mixture in the presence of S. Typhimurium). The inset showed photographs of the proposed assay in the presence of different bacteria. e The recycle of MCOF under ultrasonic conditions (90 Hz, 30 s) in five successive cycles. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three replicates.

To investigate the specificity of the assay, five common foodborne pathogens (L. monocytogenes, V. parahaemolyticus, S. aureus, E. coli O157:H7 and S. Enteritidis) were selected as interferences (each at 106 CFU mL−1). It was found that the presence of S. Typhimurium, either alone or mixing with other bacteria, resulted in a significant decrease in Δλ and a change in solution color to green. Conversely, samples containing only interfering bacteria showed golden yellow with large Δλ (Fig. 6d). The results demonstrated that the developed multicolor colorimetric assay specifically responded to S. Typhimurium without coexisting species interfering.

The reusability is a critical parameter for MCOF acting as an adsorbent in practical applications, which was assessed by successive detection cycles in this study. First, the nanocomposites underwent ultrasonication and magnetic separation from the initial reaction solution. The resultant MCOF was then directly employed for the next reaction. As depicted in Fig. 6e, comparable colorimetric signal responses were detected in the three consecutive cycles, signifying the outstanding reusability of MCOF as adsorption scaffold of Apt-AuNPs for nanozyme self-assembly and catalysis.

Analysis of food samples

As foodborne outbreaks caused by Salmonella are often associated with the consumption of contaminated fresh produce36, chicken, milk, pork and lettuce samples contaminated with varying concentrations of S. Typhimurium were chosen as the candidates to investigate the practicability of the assay in different food matrix. The proposed method was employed to detect these samples, and the plate count method as a gold standard procedure was used for validation purpose (Fig. S7). The recoveries for four kinds of food samples were 90.9–108.2% with the relative standard derivations (RSDs) lower than 10% (Table 2). Thus, this demonstrated that the assay possessed good reliability and applicability for pathogenic bacteria detection in various food samples.

Discussion

In this work, a multicolor colorimetric assay was engineered for S. Typhimurium detection on the basis of target-inhibited MCOF-Apt-AuNPs self-assembly coupling with AuNRs as the colorimetric substrate. The remarkably hindered self-assembly process induced by S. Typhimurium and excellent LSPR property of AuNRs was demonstrated experimentally, enabling visual detection of S. Typhimurium through vivid colors. Such an assay could also be applied for S. Typhimurium determination in diverse food samples such as chicken, milk, pork and lettuce samples, making it a promising tool for on-site food control.

Methods

Materials and reagents

Ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O), ethylene glycol, anhydrous sodium acetate (NaAc), tetrahydrofuran (THF), acetone, trisodium citrate and hydrogen peroxide were purchased from Tianjin Guangfu Technology Development Co., Ltd. (China). Citric acid and sulfuric acid (H2SO4) were obtained from Beijing Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (China). 1,3,5-tris (4-aminophenyl) benzene (TAPB), 1,4-dioxane, butanol, hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) and 5-bromosalicylic acid were procured from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (China). 2,5-dihydroxyterephthalaldehyde (DHTA), glacial acetic acid, sodium borohydride (NaBH4), silver nitrate (AgNO3) and ascorbic acid (AA) was received from Shanghai Aladdin reagents Co., Ltd. (China). 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) and sodium acetate (NaAc)–acetic acid (HAc) buffer (0.20 M, pH = 4) were bought from Beijing Dingguo Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (China). Chloroauric acid (HAuCl4·3H2O) was purchased from Sigma Company (USA). The sequence of S. Typhimurium aptamers was 5′-SH-(CH2)6- AGT AAT GCC CGG TAG TTA TTC AAA GAT GAG TAG GAA AAG A -3′[ 37 and synthesized by Shanghai Sangon Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (China). Double-distilled water (DDW) and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 10 mM, pH = 7.40) were prepared by us. All chemicals and reagents employed were of analytical grade and were used without any further purification.

Instruments

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images and energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) element mappings were performed on a JEOL JEM-2100F transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Japan). The zeta potential and dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements were recorded on a Nano-ZS90 Zeta sizer ZEN3600 (Malvern Instruments Ltd, UK). Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic (FTIR) analysis was conducted by a Nicolet 6700 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., USA) with KBr pellets. The magnetization hysteresis loops and magnetic saturation (MS) values were gauged by a Lake Shore 7404 Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (Lake Shore Cryotronics, Inc., USA) at room temperature. The absorbance values were measured by a TECAN INFINITE E PLEX 200 PRO multi-well plate reader (Tecan, CH).

Bacterial culture

All the bacterial strains listed in Table 3 were stored at −80 °C with 15% glycerol and revived by streaking on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates. They were cultivated in LB medium at 37 °C for 12 h with shaking at 180 rpm, respectively. The concentrations of bacteria were determined by using the gold standard of plate counting method.

Synthesis of MCOF

First, 1.35 g FeCl3·6H2O and 3.60 g NaAc were ultrasonically dissolved in 40 mL of ethylene glycol for 30 min. Then, the solution was transferred into a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave, heating for 16 h at 200 °C. The black products were washed three times with absolute ethanol and DDW and dried under vacuum at 60 °C for 12 h. Second, the synthesis of COF was prepared based on the previously reported method with minor modification28. 10.50 mg TAPB and 7.40 mg DHTA were dissolved the mixture solution of 2 mL 1,4-dioxane and 2 mL butanol were ultrasonically dissolved. After 12 mg Fe3O4 NPs were completely dispersed in the above solution, 0.05 mL glacial acetic acid was added and the mixture was allowed to react at room temperature for 2 h. Then, 0.45 mL of acetic acid aqueous solution (12 M) was added and the obtained mixture was heated at 70 °C for 48 h. Finally, the products were cooled to room temperature, collected by a permanent magnet, washed alternately three times with THF and acetone, and dried under vacuum at 30 °C overnight.

Synthesis of Apt-AuNPs

For the synthesis of AuNPs, to start, 0.50 mL of 1% HAuCl4·3H2O (1% w/v) was dissolved in a three necked bottle containing 52 mL of DDW and heated to boiling with vigorous magnetic stirring. Then, 2 mL of sodium-citrate solution (1% w/v, containing 0.05% w/v citric acid) was injected rapidly into the above solution. After heating for 5 min, the resultant citrate-stabilized Au NPs colloids were naturally cooled and stored at 4 °C.

For the conjugating aptamer on the AuNPs, the aptamer (10 μM) was heated at 95 °C for 2 min, and quickly dropped to room temperature firstly. Subsequently, 1 mM TCEP was added and reacted for 1 h at room temperature to reduce the disulfide bond. Then 20 μL of aptamer was mixed with 1.50 mL of AuNPs and rotated for 16 h at room temperature. Finally, the apt-Au NPs solution was centrifugated (13,000 rpm, 20 min) to remove excess unconjugated aptamer, resuspended with DDW and stored at 4 °C for further use.

Synthesis of AuNRs

According to the previous report, AuNRs were synthesized by using aromatic additives combination with a reduced amount of CTAB surfactant38. To prepare the seed solution, 5 mL of CTAB (0.20 M) and 5 mL of HAuCl4·3H2O (0.50 mM) was mixed and stirred evenly in a beaker, then 0.6 mL of NaBH4 solution (0.01 M) injected rapidly into above solution under vigorously stirring for 2 min and aged for 30 min to prepare gold seeds. Next, to prepare the growth solution, 1.81 g of CTAB and 0.23 g of 5-bromosalicylic acid were completely dissolved in 50 mL DDW. Then, 2.42 mL of AgNO3 solution (4 mM) and 50 mL of HAuCl4·3H2O (1 mM) were added in sequence. After stirring gently for 15 min, 0.40 mL of AA (0.06 M) was injected and stirred vigorously until it became colorless. Following that, 0.16 mL of seed solution was added into the growth solution and then left undisturbed at 30 °C for 12 h. The AuNRs were obtained by centrifugation (8500 rpm, 25 min) and then dispersed in 10 mL of CTAB (0.20 M).

Detection of S. Typhimurium

Different concentrations of bacterial standard samples (102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107 and 108 CFU mL−1) were prepared. Following the optimal experimental conditions, 200 μL of S. Typhimurium solution was added into the reaction system containing 20 μL of MCOF (1 mg mL−1) and 50 μL of Apt-AuNPs (4.52 nM). The solution was subjected to gentle rotation at ambient temperature for 30 min and separated by the permanent magnet to remove the supernatant. Then, the precipitated composites were mixed with 180 μL of NaAc-HAc buffer (0.02 M, pH = 4) was added to resuspend the precipitated composites, after which 10 μL of TMB (20 mM), 10 μL of H2O2 (10 M) were sequentially added to the detection system. After an 8-min reaction, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 50 μL of H2SO4 (2 M), resulting in the formation of the “etching solution” (TMB2+). Finally, the supernatant “etching solution” was added into 100 μL of AuNRs solution (5 nM) to initiate the chemical etching of AuNRs. The absorption spectrum of the solution was measured using a Microplate reader in the range from 400 to 900 nm.

Detection of S. Typhimurium in food samples

Food samples including chicken, milk, pork and lettuce were acquired from a local supermarket for the practicability study. A total of 5 g each of chicken, pork and lettuce were prepared by washing, shredding, and then being soaked in 50 mL of sterile PBS to create a homogeneous suspension. Similarly, 1 mL of milk was diluted 100 times with sterile PBS. Subsequently, the resulting meat and vegetable suspension, along with the milk dilution, underwent sterilization by filtration through 0.22 μm filters. Prior to inoculation, the absence of bacteria in these food samples was verified using the plate count method. Different concentrations of S. Typhimurium were inoculated into the filtrate and incubated at 37 °C for 6 h to produce various S. Typhimurium-contaminated food samples. After that, these food samples were analyzed according to the procedures mentioned in the “Detection of S. Typhimurium” section.

Data availability

The data supporting the finding reported herein are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Yousefi, H. et al. Sentinel wraps: real-time monitoring of food contamination by printing DNAzyme probes on food packaging. ACS Nano 12, 3287–3294 (2018).

Mkangara, M. Prevention and control of human Salmonella enterica infections: an implication in food safety. Int. J. Food Sci. 2023, 8899596 (2023).

Yin, X. C. et al. Nanocatalyst-triggered cascade immunoassay: multi-model immunochromatography assay for sensitive detection of Salmonella typhimurium. Chem. Eng. J. 469, 143979 (2023).

Li, Q. R. et al. An autonomous synthetic DNA machine for ultrasensitive detection of Salmonella typhimurium based on bidirectional primers exchange reaction cascades. Talanta 252, 123833 (2023).

Mirsadoughi, E., Pebdeni, A. B. & Hosseini, M. Sensitive colorimetric aptasensor based on peroxidase-like activity of ZrPr-MOF to detect Salmonella Typhimurium in water and milk. Food Control 146, 109500 (2023).

McGoverin, C. et al. Optical methods for bacterial detection and characterization. APL Photonics 6, 080903 (2021).

Bai, X. et al. Portable dual-mode biosensor based on smartphone and glucometer for on-site sensitive detection of Listeria monocytogenes. Sci. Total Environ. 874, 162450 (2023).

Yin, L. et al. Ultrasensitive pathogenic bacteria detection by a smartphone-read G-quadruplex-based CRISPR-Cas12a bioassay. Sens. Actuators B 347, 130586 (2021).

Xu, S. H. et al. A morphology-based ultrasensitive multicolor colorimetric assay for detection of blood glucose by enzymatic etching of plasmonic gold nanobipyramids. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1071, 53–58 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. Regulating the growth rate of gold nanobipyramids via a HCl-NADH-ascorbic acid system toward a dual-channel multicolor colorimetric immunoassay for simultaneously screening and detecting multiple sulfonamides. Anal. Chem. 95, 10438–10447 (2023).

Luo, L. et al. A high-resolution colorimetric immunoassay for tyramine detection based on enzyme-enabled growth of gold nanostar coupled with smartphone readout. Food Chem. 396, 133729 (2022).

Retout, M. et al. Ultra-stable silver nanotriangles: efficient and versatile colorimetric reporters for dipstick assays. Nanoscale 15, 11981–11989 (2023).

Liu, Y. S. et al. A multicolorimetric assay for rapid detection of Listeria monocytogenes based on the etching of gold nanorods. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1048, 154–160 (2019).

Khalil, L., Sabahat, S. & Ahmed, W. Effect of aspect ratio on the catalytic activities of gold nanorods. Catal. Lett. 154, 1018–1025 (2023).

Ma, X. M. et al. A universal multicolor immunosensor for semiquantitative visual detection of biomarkers with the naked eyes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 87, 122–128 (2017).

Orouji, A., Abbasi-Moayed, S., Ghasemi, F. & Hormozi-Nezhad, M. R. A wide-range pH indicator based on colorimetric patterns of gold@silver nanorods. Sens. Actuators B 358, 131479 (2022).

Zhang, H. W. et al. A multicolor sensing system for simultaneous detection of four foodborne pathogenic bacteria based on Fe3O4/MnO2 nanocomposites and the etching of gold nanorods. Food Chem. Toxicol. 149, 112035 (2021).

Chen, X., Zhang, H. Y., Liang, X. Y. & Li, L. L. Dual-responsive persistent luminescence nanoflowers for glutathione detection and imaging. Sens. Actuators B 403, 135200 (2024).

Zhang, F. X. et al. Reactive oxygen species independent oxidase like nanozyme for dual-mode analysis of α-glucosidase. Chem. Eng. J. 492, 152328 (2024).

Yuan, Y. F., Bang, K. T., Wang, R. & Kim Y. Macrocycle-based covalent organic frameworks. Adv. Mater. 35 https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202210952 (2023).

Yang, J., Huang, L., You, J. M. & Yamauchi Y. Magnetic covalent organic framework composites for wastewater remediation. Small 19 https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202301044 (2023).

Zhang, N. et al. Recent investigations and progress in environmental remediation by using covalent organic framework-based adsorption method: a review. J. Clean. Prod. 277, 123360 (2020).

Lu, S. L. et al. Synthesis of ultrafine and highly dispersed metal nanoparticles confined in a thioether-containing covalent organic framework and their catalytic applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 17082–17088 (2017).

Wu, Z. J. et al. Spherical covalent organic framework supported Cu/Ag bimetallic nanoparticles with highly catalytic activity for reduction of 4-nitrophenol. J. Solid State Chem. 311, 123116 (2022).

Gao, P. et al. COF-DNA bicolor nanoprobes for imaging tumor-associated mRNAs in living cells. Anal. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.2c03658 (2022).

Cui, J. et al. Porphyrin-based covalent organic framework as bioplatfrom for detection of vascular endothelial growth factor 165 through fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Talanta 228, 122060 (2021).

Wang, H. Y. et al. A novel fluorescent sensor based on a magnetic covalent organic framework-supported, carbon dot-embedded molecularly imprinted composite for the specific optosensing of bisphenol A in foods. Sens. Actuators B 361, 131729 (2022).

Ma, Y. Y. et al. Magnetic covalent organic framework immobilized gold nanoparticles with high-efficiency catalytic performance for chemiluminescent detection of pesticide triazophos. Talanta 235, 122798 (2021).

Yao, S. et al. Colorimetric immunoassay for rapid detection of Staphylococcus aureus based on etching-enhanced peroxidase-like catalytic activity of gold nanoparticles. Microchim. Acta. 187, 504 (2020).

Pachfule, P., Kandambeth, S., Diaz, D. D. & Banerjee, R. Highly stable covalent organic framework-Au nanoparticles hybrids for enhanced activity for nitrophenol reduction. Chem. Commun. 50, 3169–3172 (2014).

Wei, S. N. et al. On-site colorimetric detection of Salmonella typhimurium. NPJ Sci. Food 6, 48 (2022).

Jiang, B. et al. Standardized assays for determining the catalytic activity and kinetics of peroxidase-like nanozymes. Nat. Protoc. 13, 1506–1520 (2018).

Ma, X. et al. A universal multicolor immunosensor for semiquantitative visual detection of biomarkers with the naked eyes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 87, 122–128 (2017).

Tian, F. et al. Manganese dioxide nanosheet-mediated etching of gold nanorods for a multicolor colorimetric assay of total antioxidant capacity. Sens. Actuators B 321, 128604 (2020).

Rao, H., Xue, X., Wang, H. & Xue, Z. Gold nanorod etching-based multicolorimetric sensors: strategies and applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 7, 4610–4621 (2019).

Yang, Q. et al. Total coliforms, microbial diversity and multiple characteristics of Salmonella in soil-irrigation water-fresh vegetable system in Shaanxi, China. Sci. Total Environ. 924, 171657 (2024).

Duan, N. et al. Selection and characterization of aptamers against Salmonella typhimurium using whole-bacterium systemic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX). J. Agric. Food Chem. 61, 3229–3234 (2013).

Ye, X. C. et al. Improved size-tunable synthesis of monodisperse gold nanorods through the use of aromatic additives. ACS Nano 6, 2804–2817 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82473636) and Jilin Province Science and Technology Development Plan Item (Grant No. 20220203032SF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L.: methodology, validation, and writing—original draft; H.X.: validation, investigation and writing—review and editing; S.Y.: formal analysis, visualization and writing—review and editing; S.W.: visualization and writing—review and editing; Y.L.: data curation and writing—review and editing; X.S.: data curation and writing—review and editing; W.Z.: funding acquisition and writing—review and editing; C.Z.: conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, project administration and writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Xu, H., Yao, S. et al. Target-inhibited MCOF-Apt-AuNPs self-assembly for multicolor colorimetric detection of Salmonella Typhimurium. npj Sci Food 8, 78 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-024-00321-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-024-00321-7