Abstract

Stenophylla coffee, an undomesticated species from Upper West Africa, is of commercial interest due to its high heat tolerance and Arabica-like flavour. To investigate the chemical basis of flavour similarity, we analysed unroasted coffee bean samples using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) and applied metabolomics approaches to compare chemical profiles. We report similarities between Arabica and stenophylla in the relative levels of several key compounds linked to coffee flavour, including caffeine, trigonelline, sucrose and citric acid. Differences in their chemical profiles were also observed, especially in their diterpenoid and hydroxycinnamic acid profiles. We report the additional novel finding that theacrine occurs in stenophylla, which is the first record of this alkaloid in coffee beans. For stenophylla, the dissimilarities in chemical compound composition (compared to Arabica) may offer opportunities for a better understanding of the chemical basis of high-quality coffee and sensory diversification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Consumer demand supports a multi-billion-dollar coffee sector. At least 80 countries produce coffee at scale, resulting in global exports of over 10 billion kg per year1. The appreciation of coffee is driven by sensory pleasure, its stimulatory properties (mainly due to caffeine), and myriad cultural associations, but above all, a coffee-like flavour is required. For most coffee consumers, Arabica coffee (Coffea arabica) is the first choice, and then robusta or conilon (Coffea canephora), which together comprise at least 99.9% of global coffee trade. Liberica (Coffea liberica) and excelsa (Coffea dewevrei) are minor coffee crop species, although their popularity with farmers and consumers is experiencing a revival2. Other coffee species are farmed, but only at small scale with negligible production volumes3.

The long-term sustainability of the coffee farming sector is a major concern in an era of accelerated climate change4. A range of adaptation pathways have been suggested3, but one of the most pressing requirements is to provide alternative coffee crop options for farmers that are no longer able to produce economically viable Arabica or robusta coffee due to climate change5. Whereas improved Arabica and robusta variants may provide potential, switching coffee species entirely is likely to provide greater gains in terms of climate change resiliency3,5. Key coffee species candidates include stenophylla (Coffea stenophylla)3,6, Liberica (C. liberica)2, and excelsa (C. dewevrei)2,7,8.

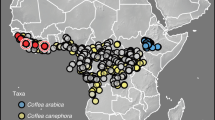

Stenophylla coffee has been the subject of intense interest, due to its high-quality Arabica-like flavour3,9. This is remarkable because stenophylla and Arabica are neither closely related phylogenetically10,11, nor similar morphologically3. Moreover, their indigenous distributions and climate envelopes do not overlap3. Arabica is a cool-tropical species, indigenous to the highland forests of Ethiopia and South Sudan at an elevation of 1000–2200 m12,13,14; stenophylla occurs in the lowland forests of Guinea, Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast and possibly Liberia6 at c. 400 m. Over its indigenous range, Arabica receives c. 1600 mm of rainfall per year and a mean annual temperature of c. 18.7 °C3, and stenophylla 1500–2288 mm and 25–26 °C3,15. Naturally occurring stenophylla has a substantially higher heat tolerance compared to Arabica (mean annual temperature 6.2–6.8 °C higher) even under similar rainfall conditions3.

Among the approximately 130 Coffea species5,16, stenophylla is the only species known to have an Arabica-like flavour (other than Arabica itself)3,9. Indeed, the cup profile and flavour of stenophylla coffee has even been considered as indistinguishable to specific regional variants of Arabica, and particularly high elevation, Rwanda C. arabica ‘Bourbon’3. This is compelling given the phylogenetic, geographical, and environmental differences between the two species. The common perception for paramount coffee quality is that it should be Arabica, grown on farms at high elevations (e.g., 1600 m or more), which experience cool-tropical temperatures with a wide diurnal variation (i.e., considerable difference between day and night temperatures), and high UV levels17,18,19. Thus, stenophylla breaks the orthodoxy for fundamental quality coffee requirements.

Given the global demand for the Arabica flavour profile, the threat posed by climate change to Arabica4,20, and the incongruity between perceived genetic and environmental parameters for high-quality coffee, understanding the chemical relationships between Arabica and stenophylla is a key aim for coffee sensory research.

The chemistry underpinning coffee flavour and quality is highly complex. More than 700 compounds (in ‘green’, unroasted coffee) have been considered to influence coffee flavour and aroma: key compounds modulating flavour and quality include caffeine, trigonelline, sugars, hydroxycinnamic (including chlorogenic) acids, and other acids21,22,23. Moreover, coffee chemistry, and hence flavour, may be influenced by many other factors including the species or cultivar (‘variety’), geographic origin of the beans, climate factors17,18,19,24, and post-harvest processing methods22. Roasting also substantially influences coffee chemistry, due to the complex conversion of many compounds (discussed here) by processes such as the Maillard reaction, caramelisation and the production of numerous volatiles via pyrolysis25. Regardless of these variables, green bean coffee chemistry can be correlated with the sensory quality of brewed coffee22,26 and used to characterise Coffea species27,28,29,30.

In this article, we elucidate the chemical profile of green (unroasted) stenophylla coffee beans using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) and metabolomics approaches to understand the chemical relationships between this poorly-studied species and Arabica coffee. For comparison, we include the other major commercial coffee species, robusta, as many differences in green coffee chemistry between Arabica and robusta have been reported31. We focus on the comparison of compounds that are considered to be important for coffee flavour, including alkaloids such as caffeine and trigonelline, hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives including chlorogenic acids, other acidic compounds, sucrose and diterpenoids. Principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering are used to assess the differences in the overall metabolomic profiles between the three species.

Methods

Sample selection

Seeds (beans) of 26 coffee accessions were sampled for chemical analysis (Supplementary Table S4). The Arabica samples include five representatives of indigenous Ethiopian cultigens, and six randomly selected from other cultivated sources (El Salvador, Brazil, Colombia, Rwanda, and Indonesia), four of which are well-known, named cultivars. The eight robusta samples represent a random selection from cultivated stock, from Brazil, Rwanda, Uganda, India (×2), Indonesia (×2). The seven stenophylla samples were collected from wild trees in Sierra Leone. The sampling included sun-dried samples for all species, and a few random samples of semi-washed or washed samples for Arabica and robusta. Most green bean compounds are stable regardless of processing methods although there can be quantitative differences22.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis

Each individual coffee bean was ground using a pestle and mortar, prior to extraction of the powdered material at a concentration of 100 mg/ml in 80:20 methanol:water at room temperature for 24 h, prior to centrifugation and transfer of supernatants to LC-MS vials. Three individual beans were analysed for each accession (i.e., analyses were in triplicate per accession). Supernatants were analysed using a Thermo Scientific LC–MS system consisting of a ‘Vanquish Flex’ U-HPLC-PDA, and an ‘Orbitrap Fusion’ mass spectrometer fitted with an “Ion Max NG” heated electrospray source (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Chromatography was performed on 5 µl sample injections onto a 150 mm × 3 mm, 3 µm Luna C-18(2) column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) using the following 400 µl/min mobile phase gradient of H2O/CH3OH/CH3CN + 1% HCOOH: 90:0:10 (0 min), 0:90:10 (60 min), 0:90:10 (70 min), 90:0:10 (71 min), 90:0:10 (75 min). Solvents were obtained from Fisher Scientific (OPTIMA LC-MS grade). The heated ESI source was operated under the manufacturer’s default conditions for the flow rate employed and the mass spectrometer was set to record high resolution (60 k resolution) MS1 spectra (m/z 125–1800) in both positive and negative modes using the orbitrap; and data dependent MS2 and MS3 spectra in both modes using the linear ion trap. Detected compounds were assigned using the approach described by Schymanski et al.32 and were by comparison of accurate mass (ppm) and interpretation of available MSn and UV spectra, with reference to Kew’s in-house libraries of ion trap MS and UV spectra, in addition to comparison with published data33,34,35,36. The assignments of trigonelline, caffeine, (Sigma-Aldrich) and theacrine (PhytoLab, PhytoProof grade) were also by comparison with reference standards. Quality control samples (consisting of the pooled coffee extracts analysed) were analysed every ten samples to monitor and determine LC–MS performance and stability throughout the analysis.

Data processing and chemometrics

LC–MS data were processed with Compound Discover v3.1 (Thermo Scientific, USA) to obtain peak areas for each chromatogram. Chromatographic features were grouped into compounds if they had the same retention time and grouped feature areas were summed to give compound peak areas for statistical analyses. Peak areas were used as a measure of the relative levels of the compounds detected in the species analysed.

To verify differences between species for each of the 37 assigned compounds, pairwise statistical tests were used. Where both samples passed normality tests (either N > 30 or p > 0.05 in the Shapiro–Wilk test37) Welch’s two sample t-test38 was used, otherwise the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was used39. To show equivalence for a given compound and pair of species, the two one-sided test (TOST) procedure was used, with an effect size of 25% of the mean of the given samples. Again, where the samples pass normality tests we used Welch’s t-test as the one-sided test, else we used a one-sided Mann–Whitney U test. In both cases, Hochberg’s step-up procedure40 was implemented to correct for the family-wise error rate associated with multiple tests. Statistical tests were carried out using the scipy41 and statsmodels42 Python libraries.

The PCA was implemented using scikit-learn43 after scaling the values by removing the mean and scaling to unit variance. PERMANOVA44, implemented in scikit-bio45, was used to verify the distinctions seen between species in the PCAs. Euclidean distance was used to generate the relevant dissimilarity matrices, and 1000 permutations were used to assess statistical significance. The Logistic Regression models trained on the principal components and the evaluation procedure were implemented using scikit-learn.

For the hierarchical clustering heatmaps, values were first scaled by removing the mean and scaling to unit variance. The heatmap was implemented and plotted in seaborn46, using Pearson correlation to measure distance and the complete linkage method to assign clusters.

Results

Comparison of compounds between stenophylla, Arabica and robusta

Representative base peak chromatograms (positive and negative ionisation modes) for each of the three species are shown in Fig. 1, to illustrate their chemical profiles. In total, 37 compounds were assigned across the three species (Fig. 1; Supplementary Tables S1–S3); the detection of these compounds is discussed below, with a focus on compounds associated with coffee flavour.

1: Trigonelline; 2: Sucrose; 3: Quinic acid; 4: Malic acid; 5: Citric acid; 6: 3-O-Caffeoylquinic acid; 7: Theacrine; 8: 5-O-Caffeoylquinic acid; 9: Caffeine; 10: 4-O-Caffeoylquinic acid; 11: Caffeic acid; 12: 5-O-Coumaroylquinic acid; 13: 5-O-Feruloylquinic acid; 14: Diterpenoid glycoside assigned as coffaroyloside or isomer; 15: Diterpenoid diglycoside; 16: Diterpenoid glycoside assigned as coffaroyloside or isomer; 17: CATR II; 18: N-Caffeoyltyrosine; 19: Mozambioside; 20: 2-O-Glucopyranosyl-deoxyhexopyranosyl-carboxyatractyligenin; 21: Dimethoxy-cinnamoylquinic acid; 22: 3,4-Di-O-caffeoylquinic acid; 23: Bengalensol; 24: 4,5-Di-O-caffeoylquinic acid; 25: 4-O-Caffeoyl-3-O-feruloylquinic acid; 26: CATR I; 27: N-Caffeoyltryptophan; 28: Dimethoxy-cinnamoylcaffeoylquinic acid I; 29: Caffeoylvaleroylquinic acid; 30: CATR III; 31: N-Hydroxy-coumaroyltryptophan; 32: Dimethoxy-cinnamoylcaffeoylquinic acid II; 33: N-Feruloyltryptophan; 34: ATR V; 35: Dimethoxy-cinnamoylferuloylquinic acid; 36: N-Eicosanoylserotonin; 37: N-Docosanoylserotonin.

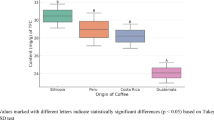

Alkaloids

Caffeine was one of the major compounds detected by LC–MS analysis (peak 9, Fig. 1). Analysis of the relative quantities of caffeine in all three species (Fig. 2) show a significantly higher occurrence in robusta coffee than in both Arabica (P < 0.001), as previously observed47,48, and stenophylla (P < 0.001). The caffeine contents of Arabica and stenophylla were found to be similar (TOST P = 0.077). Less intraspecific variation in caffeine was observed in stenophylla, which is perhaps due to the lack of variation in geographical origin of the samples compared to the other two species. In addition to caffeine, stenophylla was found to contain the related alkaloid theacrine (7), which was not detected in any samples of Arabica or robusta (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2) and has not been reported in coffee beans previously. Comparison of the trigonelline (1) content showed no statistically significant differences between the three species (Fig. 2), but Arabica and stenophylla were found to be similar through TOST (P = 0.096).

1: Trigonelline; 2: Sucrose; 5: Citric acid; 7: Theacrine; 8: 5-O-Caffeoylquinic acid; 9: Caffeine; 19: Mozambioside; 24: 4,5-Di-O-caffeoylquinic acid; 25: 4-O-Caffeoyl-3-O-feruloylquinic acid; 26: CATR I; 32: Dimethoxy-cinnamoylcaffeoylquinic acid II; 36: N-Eicosanoyl-serotonin. Plots of all compounds discussed in this paper can be found in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Hydroxycinnamic acids and derivatives

The chlorogenic acids (3-, 4-, and 5-O-caffeoylquinic acids, peaks 6, 8, & 10) were amongst the main compounds detected in the three species analysed by LC–MS (Fig. 1); Fig. 2 shows the comparison of the latter across the three species. No significant differences in the levels of these chlorogenic acids were found between Arabica and stenophylla (P = 0.33, 0.99, and 0.58, respectively), although robusta had a greater content of 3-O-caffeoylquinic acid than Arabica (P < 0.001).

5-O-Feruloylquinic acid (13) was detected at higher levels in robusta than in the other two species (P < 0.001 for both). Though a difference in levels between Arabica and stenophylla was similarly observed (P < 0.001), the magnitude of the difference was smaller by comparison, Arabica only accumulating slightly more than stenophylla. Caffeoyl- and feruloyl-quinic acids have previously been reported to occur at higher levels in robusta, compared with Arabica24,49.

The amount of caffeic acid (11) was not found to differ significantly between Arabica and stenophylla (P = 0.082, >0.1 following Hochberg correction), but were higher in robusta (P < 0.001 compared to both Arabica and stenophylla). The amount of 5-O-coumaroylquinic acid (12) in stenophylla was found to be significantly lower than in Arabica (P < 0.001) and robusta (P < 0.001).

A number of doubly-esterified quinic acids were also detected by LC–MS: 3,4- and 4,5-di-O-caffeoylquinic acid (22 & 24), 4-O-caffeoyl-3-O-feruloylquinic acid (25), caffeoylvaleroylquinic acid (29), two compounds assigned as dimethoy-cinnamoylcaffeoylquinic acids (28 & 32), and one assigned as dimethoxy-cinnamoylferuloylquinic acid (35). Of these, 4,5-di-O-caffeoylquinic acid and 4-O-caffeoyl-3-O-feruloylquinic acid (Fig. 2) were detected in higher amounts in robusta compared to Arabica (P < 0.001 for both) and stenophylla (P < 0.001 for both). A statistically significant difference in levels of these compounds between Arabica and stenophylla was not observed. However, a lower content of 3,4-di-O-caffeoylquinic acid was observed in stenophylla, compared to the other species analysed (P < 0.001 for both). A significant difference in levels of caffeoylvaleroylquinic acid was not found across any pairwise comparisons. The doubly-esterified quinic acids assigned as dimethoxy-cinnamoyl derivatives were detected at much higher levels in stenophylla than in the other two species (P < 0.001 for all) (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. S2).

Other acids

Lower levels of both quinic (3) and malic acids (4) were observed in samples of stenophylla than in Arabica (P < 0.001 for both), although no such difference was observed for citric acid (5, see Fig. 2). Comparison through TOST found levels of citric acid in Arabica and stenophylla to be similar (P = 0.018).

Diterpenoids

Of all the classes of compounds detected in the three species, the diterpenoids showed the most interspecific variation. Only trace amounts of diterpenoids were detected in the robusta samples, contrasting with a range of diterpenoids detected in stenophylla and Arabica. Interestingly, many of these were only detected in either one species or the other, rather than both; previous reports have described certain coffee diterpenoids as highly variable in content and profile between species, including stenophylla50.

Several atractyloside derivatives were assigned in samples of Arabica and stenophylla. Of these, compounds assigned as CATR II (17) and ATR V (34) were observed in the Arabica samples at higher levels, compared to the trace amounts detected in robusta and stenophylla. The compounds assigned as CATR I (26), CATR III (30), and 2-O-glucopyranosyl-deoxyhexopyranosyl-carboxyatractyligenin (20) were detected in both Arabica and stenophylla. A compound assigned as the furokaurane glycoside, mozambioside (19), was detected in all samples of Arabica, but not in those of stenophylla or robusta (P < 0.001 for both) (Fig. 2). A compound assigned as bengalensol (23), first isolated from the leaves of Coffea benghalensis51, was detected in samples of Arabica and stenophylla, though the content was significantly higher in stenophylla (P < 0.001). Other compounds assigned as diterpenoid glycosides included a diterpenoid dihexoside (15) only detected in stenophylla, and two compounds with the molecular formula C26H42O10 (14 & 16), consistent with that of cofaryloside or isomers52, both were only detected in samples of Arabica.

Other compounds

The levels of sucrose (2) in Arabica and stenophylla were similar (TOST P < 0.001, see Fig. 2); in contrast, the level of sucrose in robusta was significantly lower than Arabica (P = 0.0017). Compounds assigned as tyrosine and tryptophan derivatives were detected at higher levels in robusta, compared to Arabica and stenophylla (P < 0.001 for all assigned compounds); these detected compounds were assigned as N-caffeoyltyrosine (18), N-caffeoyl-, N-feruloyl-, and N-hydroxycoumaroyl-tryptophan (27, 33, & 31, see Supplementary Fig. S2). This finding is in accordance with previous reports, in which caffeoyltyrosine and related compounds were considered to be chemotaxonomic markers of robusta coffee53. Compounds assigned as the serotonin derivatives N-eicosanoylserotonin (36) and N-docosanoylserotonin (37) were detected in all three species; stenophylla had significantly lower levels of the latter than Arabica (P < 0.001), but no such difference was observed for N-eicosanoylserotonin (Fig. 2).

Metabolomic analyses

PCA of the overall metabolomes shows a clear distinction between the three species (Fig. 3), which is verified through PERMANOVA tests on the four pictured principal components, the first 16 components which explain 80% of the variance, and all the components (P < 0.001 in each case). When Logistic Regression models are trained to classify species based on the principal components, if only PC1 is used the model achieves 88% accuracy in leave-one-out cross-validation. Using PC1, PC2, …, PCj for 1 < j ≤ N, the model achieves 100% accuracy—confirming that these species can be reliably delineated based on their chemical profiles.

Considering the loadings generated in the PCA for each of the 37 assigned compounds (Fig. S3), some distinct groupings are observed. This is clearest in the case of stenophylla where the samples appear to form a dense group loading negatively on PC1 and PC2, associated with high values for compounds 7, 15, 20, 21, 32, and 35. Similarly, robusta samples are associated with high values for 6, 9, 10, 11, 13, 18, 24, 25, 27, 29, 31, and 33. For Arabica, though the plot appears to identify two distinct groups, in general the samples are associated with positive values in PC2, related strongly to compounds 17 and 19. These findings align with the plots presented in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S2.

Hierarchical clustering heatmaps of the metabolomes of each sample analysed (Fig. 4) identify several characteristic regions of compounds for the three species, similar to those identified in the PCA loading plot (Fig. S3). Group A shows high contents for robusta that are not present in stenophylla, or most Arabica samples, although there is some overlap with group D. Group A also highlights some within-species variation for robusta where contents are lower outside of A, with some exceptions in group B. Group C shows a distinctive region of high contents in stenophylla that are mostly not found in the other species, similarly for Group E and Arabica.

The plot shows several characteristic regions of compounds for the three coffee species, in addition to some within-species variation. Compounds discussed in this paper are numbered on the right (numbering as shown in Fig. 1).

Discussion

The similarity in caffeine content between stenophylla and Arabica is highly relevant, since the stimulant and nootropic effects of caffeine are a contributing factor to the coffee experience and its market success26. Furthermore, caffeine is linked to bitterness in coffee, and thus its characteristic flavour profile. Trigonelline, observed at similar levels in Arabica and stenophylla, may also contribute to bitterness, although more indirectly, since trigonelline content is reduced during roasting and as a result, bitterness is linked to the formation of nicotinic acid54. Indeed, the resultant nicotinic acid is strongly associated with bitterness in roasted coffee55.

Detection of theacrine in stenophylla coffee is particularly interesting because until this study, theacrine had not been reported in coffee beans. Theacrine was first isolated from plants as crystals in the residues left over after de-caffeinating large quantities of tea56. Since then it has been identified as a constituent of certain varieties of tea57,58 and detected as a minor metabolite in species of Ilex59, Theobroma60, and in the leaves of certain other species of Coffea, such as C. liberica61.

Whilst the central nervous system stimulating and cognitive performance enhancing effects of caffeine are well-documented62,63, theacrine has not been studied as extensively as caffeine, though some studies have associated theacrine with improving cognitive performance without habituation64. Other studies suggest theacrine is sedative and hypnotic in vivo via non-selective adenosine receptor agonism65, thus contrasting with the stimulatory action of caffeine associated with adenosine A2A receptor antagonism62. Considering that theacrine attenuated caffeine-induced insomnia in vivo65, the stimulatory effect of stenophylla coffee (which contains both caffeine and theacrine) would be of particular interest to evaluate. The theacrine content of stenophylla brewed as a beverage is likely to vary depending on the brewing method, considering that theacrine may leach into water significantly more slowly than caffeine, as has been observed with certain varieties of tea, thus requiring a much longer brewing time57. In “kucha” tea, theacrine has been positively correlated with bitterness66. Taste tests have shown theacrine to have a significantly lower threshold of recognition than caffeine, making it likely to contribute disproportionately more to bitterness than caffeine, relative to its content57.

The biosynthetic pathway leading to theacrine production has been elucidated in tea67,68. A similar metabolic pathway has been proposed in C. liberica, which accumulates small amounts of theacrine in the leaves61, although in other Coffea species, the majority of caffeine is instead catabolised to xanthine by way of theophylline69.

Considering all the hydroxycinnamic acids and derivatives together, their content in stenophylla was overall similar to Arabica, suggesting they may contribute to the similarity in flavour between these two species. The profile of these compounds observed in robusta was different (Supplementary Fig. S2). A high level of intraspecific variation in levels of some of these compounds was observed, which might be partially explained by differences in growing conditions, as has been previously reported in coffee70.

Chlorogenic acid derivatives have been considered as chemical drivers of coffee quality, modulating coffee flavour to significantly increase coffee cup score71. These chemicals are thought to contribute to the bitter taste, acidity, and astringent flavour of coffee, even though levels may reduce by around 50% after roasting24. The hydroxycinnamic (chlorogenic) acids, 3- and 4-O-caffeoylquinic acids in particular, have been linked to the sensation of ‘mouth-coating’ (or residual oiliness in the mouth after drinking) in coffee72. Interestingly, this has been proposed to show an inverse correlation, so the increased levels in robusta (Fig. S2) may result in a reduced perception of mouth-coating.

The overall effect of doubly-esterified quinic acid derivatives on coffee flavour is linked to bitterness and astringency73,74. Although the content of these compounds may be reduced on roasting, many of the resultant products formed have been identified as highly bitter, especially esterified quinic acid lactones74. As such, the higher levels of many of these compounds found in robusta than in the two other species (Fig. 1) may contribute to differences in flavour. If the dimethoxycinnamoyl quinic acid derivatives detected in stenophylla act akin to other doubly-esterified quinic acids, their roasting products might also contribute to bitterness74. As these compounds were not detected in Arabica or robusta, they may be potential markers to distinguish stenophylla from Arabica and robusta (Fig. 1).

The content of certain small organic acids in unroasted coffee beans has been associated with sensory attributes in roasted coffee, including sourness, acidity, fruitiness, astringency, and bitterness75. The lower levels of quinic and malic acids observed in stenophylla (Supplementary Fig. S2) may contribute to observed differences in acidity and ‘fruity’ notes in sensory tasting compared to some Arabica samples3,9. However, the comparable citric acid content of both Arabica and stenophylla is of particular interest for this compound’s relevance to overall coffee flavour. Recent studies have shown that citric acid is the only small organic acid present in coffee which has a threshold of detection below the concentrations typically found in brewed coffee23. As such, it is much more likely to be involved in sensory attributes than other acids.

Certain atractyloside derivatives have previously been linked to a reduction in apparent bitterness in brewed coffee76, therefore their detection in the coffee species analysed, and notably the detection of atractylosides common to both stenophylla and Arabica, could be a contributing factor to explain the similarity in the flavour of Arabica and stenophylla.

Detection of a compound assigned as mozambioside in Arabica, but not in robusta (Fig. 2), is consistent with previous reports which describe only trace quantities in robusta77. Mozambioside has a bitter taste recognition threshold about ten times more potent than caffeine78, and some of its degradation products formed on roasting are even more bitter79, so it has been considered likely to be a major contributor to the bitter taste of Arabica. That it was not detected in stenophylla suggests that other compounds contribute to their similarity in flavour. Mozambioside may be a useful marker for Arabica coffee, since it was detected in all Arabica samples but not in the other species analysed. The apparent lack of mozambioside in stenophylla might perhaps be partially compensated for by the presence of other bitter-tasting diterpenoids, such as the compound assigned as bengalensol, which is associated with bitterness in coffee beans78.

Sucrose, the most abundant carbohydrate in green coffee beans, has been considered an important contributor to coffee taste24,80,81. It is also a precursor to various roasting products, including small organic acids such as formic, acetic, and lactic acids, which can influence coffee flavour82. The similarity in sucrose content of Arabica and stenophylla is therefore likely to be an important contributor to their similarity in flavour, particularly given the importance of caramelisation reactions during roasting80. However, the sucrose content of green coffee beans is, by itself, considered to be a poor predictor of coffee quality26. Direct comparison of the sucrose content between species is likely to be further complicated by variations in post-harvest processing, as sucrose is amongst the compounds whose concentration is most impacted by processing and storage conditions22. The influence of other compound classes detected in the coffee species analysed, including those assigned as tryptophan, tyrosine, or serotonin derivatives, on coffee taste has not previously been explored but their occurrence merits further investigation in relation to coffee flavour.

The PCAs (Fig. 3) and hierarchical clustering heatmap (Fig. 4) show that it is possible to distinguish the three coffee species using metabolomic analysis, based on green bean chemistry. This could be useful in quality control approaches, should stenophylla, or hybrids involving this species, reach the market; particularly since a niche product commanding a higher price, such as stenophylla coffee, could be vulnerable to adulteration or mislabelling. Chemical means of detecting coffee adulteration have previously been explored, including for the identification of non-coffee adulterants such as chicory or barley83, distinguishing Arabica and robusta coffee84, or to indicate geographic origin of coffee samples53. Robust approaches for coffee identification combined with traceability are highly desirable in the coffee sector. To support this, our study suggests that the chemical profiles (especially mozambioside and theacrine contents) of green beans could be potentially useful to distinguish stenophylla from Arabica and robusta.

In conclusion, this is the first report to show that certain compounds considered to influence coffee quality and flavour occur in unroasted seeds (green coffee beans) of stenophylla coffee (C. stenophylla). We also evaluate the potential chemical basis for the similarity in flavour between stenophylla and Arabica coffee. We reveal that a range of compounds associated with coffee flavour can be detected in both stenophylla and Arabica, with similar levels of caffeine, chlorogenic acids, trigonelline, sucrose, and citric acid being observed, and that their occurrence is less similar to robusta (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S2). These results provide some explanation for observations that the flavour of stenophylla and Arabica coffees are similar, and that the flavour of stenophylla is Arabica-like3,9. Similarities in the occurrence of these compounds in both stenophylla and Arabica is compelling, given the lack of relatedness (phylogenetic distance), morphological dissimilarity (e.g., black versus red fruits, respectively), geographical separation, and environmental differences3 between these species (as elaborated in the Introduction).

Despite the chemical similarities, numerous differences between stenophylla and Arabica were also observed (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S2). Notably, we detected theacrine in stenophylla (and not in Arabica), which is the first report of this alkaloid in the beans of a coffee species. The longer half-life of theacrine, combined with reports that it does not have the same stimulant effects as caffeine65,85, may provide opportunities for the development of new coffee beverages with different properties to Arabica and robusta. Another key difference between stenophylla and Arabica is the negligible occurrence of the compound assigned as mozambioiside in stenophylla (and robusta), compared to Arabica, suggesting this compound could be useful as a chemical marker for Arabica and particularly to distinguish it from stenophylla and robusta. In addition, our metabolomic analyses demonstrate that the three coffee species (stenophylla, Arabica, robusta) can be reliably distinguished and characterised based on green bean chemistry, even considering the intra-specific variation observed with Arabica and robusta.

While this study highlights the similarities in green bean chemistry between stenophylla and Arabica, we also report clear dissimilarities between the two species. Given similarities in flavour perception, yet differences in green bean chemistry, our study may be useful for gaining a better understanding of the chemical basis of coffee flavour. It may also offer opportunities for sensory diversification and thus coffee market differentiation, against a background of a changing climate and the need to sustain global coffee supplies for the future.

Data availability

Data is provided within the paper or supplementary information files. Further data are available upon request to the authors.

Code availability

Scripts used to analyse data can be found at https://github.com/alrichardbollans/coffeemetabolomics.

References

(USDA), F.A.S. Coffee: World Markets and Trade—June 2024. https://www.fas.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2024-06/coffee.pdf (2024).

Davis, A. P. et al. The re-emergence of Liberica coffee as a major crop plant. Nat. Plants 8, 1322–1328 (2022).

Davis, A. P. et al. Arabica-like flavour in a heat-tolerant wild coffee species. Nat. Plants 7, 413–418 (2021).

Kath, J. et al. Vapour pressure deficit determines critical thresholds for global coffee production under climate change. Nat. Food 3, 871–880 (2022).

Davis, A. P. et al. High extinction risk for wild coffee species and implications for coffee sector sustainability. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav3473 (2019).

Davis, A. P. et al. Lost and found: Coffea stenophylla and C. affinis, the forgotten coffee crop species of West Africa. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 616 (2020).

Davis, A. P. et al. The Wild Coffee Resources of Uganda: A Precious Heritage. p. 1–44 (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 2023).

Davis, A. P. et al. A review of the indigenous coffee resources of Uganda and their potential for coffee sector sustainability and development. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1057317 (2023).

Bertrand, B. et al. Potential beverage quality of three wild coffee species (Coffea brevipes, C. congensis and C. stenophylla) and consideration of their agronomic use. J. Sci. Food Agric. 103, 3602–3612 (2023).

Maurin, O. et al. Towards a phylogeny for Coffea (Rubiaceae): identifying well-supported lineages based on nuclear and plastid DNA sequences. Ann. Bot. 100, 1565–1583 (2007).

Hamon, P. et al. Genotyping-by-sequencing provides the first well-resolved phylogeny for coffee (Coffea) and insights into the evolution of caffeine content in its species. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 109, 351–361 (2017).

Davis, A. P. et al. The impact of climate change on natural populations of Arabica coffee: predicting future trends and identifying priorities. PLoS ONE 7, e47981 (2012).

Krishnan, S. et al. Validating South Sudan as a Center of Origin for Coffea arabica: implications for conservation and coffee crop improvement. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5, 761611 (2021).

Davis, A. P. et al. Coffee Atlas of Ethiopia. p. 138 (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 2018).

Portères, R. Etude sur les caféiers spontanés de la section “Des Eucoffeae”. Leur répartition, leur habitat, leure mise en culture et leur sélection en Cote d’Ivoire. Première partie: Répartition et habitat. Ann. Agric. Afr. Occid. 1, 68–91 (1937).

Davis, A. P. & Rakotonasolo, F. Six new species of coffee (Coffea) from northern Madagascar. Kew Bull. 76, 497–511 (2021).

Avelino, J. et al. Effects of slope exposure, altitude and yield on coffee quality in two altitude terroirs of Costa Rica, Orosi and Santa María de Dota. J. Sci. Food Agric. 85, 1869–1876 (2005).

Torrez, V. et al. Ecological quality as a coffee quality enhancer. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-023-00874-z (2023).

Bertrand, B. et al. Climatic factors directly impact the volatile organic compound fingerprint in green Arabica coffee bean as well as coffee beverage quality. Food Chem. 135, 2575–2583 (2012).

Moat, J. et al. Resilience potential of the Ethiopian coffee sector under climate change. Nat. Plants 3, 17081 (2017).

Lemos, M. F. et al. Chemical and sensory profile of new genotypes of Brazilian Coffea canephora. Food Chem. 310, 125850 (2020).

Hall, R. D., Trevisan, F. & de Vos, R. C. H. Coffee berry and green bean chemistry—opportunities for improving cup quality and crop circularity. Food Res. Int. 151, 110825 (2022).

Rune, C. J. B. et al. Acids in brewed coffees: chemical composition and sensory threshold. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 6, 100485 (2023).

Seninde, D. R. & Chambers, E. Coffee flavor: a review. Beverages 6, 44 (2020).

Moon, J.-K. & Shibamoto, T. Role of roasting conditions in the profile of volatile flavor chemicals formed from coffee beans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57, 5823–5831 (2009).

Barbosa, Md. S. G. et al. Correlation between the composition of green Arabica coffee beans and the sensory quality of coffee brews. Food Chem. 292, 275–280 (2019).

Clifford, M. N., Williams, T. & Bridson, D. M. Chlorogenic acids and caffeine as possible taxonomic criteria in Coffea and Psilanthus. Phytochemistry 28, 829–838 (1989).

Rakotomalala, J.-J. R. et al. Caffeine and theobromine in green beans from Mascarocoffea. Phytochemistry 31, 1271–1272 (1992).

Campa, C. et al. Qualitative relationship between caffeine and chlorogenic acid contents among wild Coffea species. Food Chem. 93, 135–139 (2005).

Campa, C. et al. Trigonelline and sucrose diversity in wild Coffea species. Food Chem. 88, 39–43 (2004).

El-Abassy, R. M., Donfack, P. & Materny, A. Discrimination between Arabica and robusta green coffee using visible micro Raman spectroscopy and chemometric analysis. Food Chem. 126, 1443–1448 (2011).

Schymanski, E. L. et al. Identifying small molecules via high resolution mass spectrometry: communicating confidence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 2097–2098 (2014).

Tsukui, A. et al. Direct-infusion electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry analysis reveals atractyligenin derivatives as potential markers for green coffee postharvest discrimination. LWT 103, 205–211 (2019).

Panusa, A. et al. UHPLC-PDA-ESI-TOF/MS metabolic profiling and antioxidant capacity of arabica and robusta coffee silverskin: Antioxidants vs phytotoxins. Food Res. Int. 99, 155–165 (2017).

Nemzer, B., Abshiru, N. & Al-Taher, F. Identification of phytochemical compounds in Coffea arabica whole coffee cherries and their extracts by LC-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69, 3430–3438 (2021).

Clifford, M. N. et al. Hierarchical scheme for LC-MSn identification of chlorogenic acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51, 2900–2911 (2003).

Shaphiro, S. & Wilk, M. An analysis of variance test for normality. Biometrika 52, 591–611 (1965).

Welch, B. L. The generalisation of ‘Student’s’ problem when several different population variances are involved. Biometrika 34, 28–35 (1947).

Mann, H. B. & Whitney, D. R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 18, 50–60 (1947).

Hochberg, Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika 75, 800–802 (1988).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Seabold, S. & Perktold, J. Statsmodels: econometric and statistical modeling with python. SciPy 7 (2010).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Anderson, M. J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 26, 32–46 (2001).

Rideout, J. R. et al. scikit-bio 0.5.9. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8209901 (2023).

Waskom, M. seaborn: statistical data visualization. J. Open Source Softw. 6, 3021 (2021).

dePaula, J. & Farah, A. Caffeine consumption through coffee: content in the beverage, metabolism, health benefits and risks. Beverages 5, 37 (2019).

Jeszka-Skowron, M. et al. Chlorogenic acids, caffeine content and antioxidant properties of green coffee extracts: influence of green coffee bean preparation. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 242, 1403–1409 (2016).

Bicho, N. C. et al. Identification of chemical clusters discriminators of arabica and robusta green coffee. Int. J. Food Prop. 16, 895–904 (2013).

de Roos, B. et al. Levels of cafestol, kahweol, and related diterpenoids in wild species of the coffee plant Coffea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 45, 3065–3069 (1997).

Hasan, C. M. et al. Bengalensol, a new 16-epicafestol derivative from the leaves of Coffea bengalensis. Nat. Prod. Lett. 5, 55–60 (1994).

Richter, H., Obermann, H. & Spiteller, G. Über einen neuen Kauran-18-säure-glucopyranosylester aus grünen Kaffeebohnen. Chem. Ber. 110, 1963–1970 (1977).

Alonso-Salces, R. M. et al. Botanical and geographical characterization of green coffee (Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora): chemometric evaluation of phenolic and methylxanthine contents. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57, 4224–4235 (2009).

Casal, S., Beatriz Oliveira, M. & Ferreira, M. A. HPLC/diode-array applied to the thermal degradation of trigonelline, nicotinic acid and caffeine in coffee. Food Chem. 68, 481–485 (2000).

Fujimoto, H. et al. Bitterness compounds in coffee brew measured by analytical instruments and taste sensing system. Food Chem. 342, 128228 (2021).

Johnson, T. B. Purines in the Plant Kingdom: the discovery of a New Purine in tea. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 59, 1261–1264 (1937).

Shi, Y. et al. Characterization of bitter taste theacrine in Pu-erh tea. J. Food Compos. Anal. 106, 104331 (2022).

Zheng, X.-Q. et al. Theacrine (1,3,7,9-tetramethyluric acid) synthesis in leaves of a Chinese tea, kucha (Camellia assamica var. kucha). Phytochemistry 60, 129–134 (2002).

Negrin, A. et al. LC-MS metabolomics and chemotaxonomy of caffeine-containing holly (Ilex) species and related taxa in the aquifoliaceae. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67, 5687–5699 (2019).

Febrianto, N. A. & Zhu, F. Comparison of bioactive components and flavor volatiles of diverse cocoa genotypes of Theobroma grandiflorum, Theobroma bicolor, Theobroma subincanum and Theobroma cacao. Food Res. Int. 161, 111764 (2022).

Petermann, J. B. & Baumann, T. W. Metabolic relations between methylxanthines and methyluric acids in Coffea L. 1. Plant Physiol. 73, 961–964 (1983).

Howes, M.-J. R. et al. Role of phytochemicals as nutraceuticals for cognitive functions affected in ageing. Br. J. Pharmacol. 177, 1294–1315 (2020).

Howes, M.-J. R. Alkaloids and drug discovery for neurodegenerative diseases, in Natural Products : Phytochemistry, Botany and Metabolism of Alkaloids, Phenolics and Terpenes. p. 1331–1365 (Springer, Heidelberg, 2013).

Sheng, Y.-Y. et al. Theacrine from Camellia kucha and its health beneficial effects. Front. Nutr. 7 (2020).

Qiao, H. et al. Theacrine: a purine alkaloid from Camellia assamica var. kucha with a hypnotic property via the adenosine system. Neurosci. Lett. 659, 48–53 (2017).

Qin, D. et al. Identification of key metabolites based on non-targeted metabolomics and chemometrics analyses provides insights into bitterness in Kucha [Camellia kucha (Chang et Wang) Chang]. Food Res. Int. 138, 109789 (2020).

Zhou, M.-Z. et al. Discovery and biochemical characterization of N-methyltransferase genes involved in purine alkaloid biosynthetic pathway of Camellia gymnogyna Hung T.Chang (Theaceae) from Dayao Mountain. Phytochemistry 199, 113167 (2022).

Zhang, Y.-H. et al. Identification and characterization of N9-methyltransferase involved in converting caffeine into non-stimulatory theacrine in tea. Nat. Commun. 11, 1473 (2020).

Ashihara, H., Sano, H. & Crozier, A. Caffeine and related purine alkaloids: Biosynthesis, catabolism, function and genetic engineering. Phytochemistry 69, 841–856 (2008).

dos Santos Scholz, M. B. et al. From the field to coffee cup: impact of planting design on chlorogenic acid isomers and other compounds in coffee beans and sensory attributes of coffee beverage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 244, 1793–1802 (2018).

Sittipod, S. et al. Identification of compounds that negatively impact coffee flavor quality using untargeted liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 10424–10431 (2020).

Linne, B. M. et al. Characterization of the impact of chlorogenic acids on tactile perception in coffee through an inverse effect on mouthcoating sensation. Food Res. Int. 172, 113167 (2023).

Huang, R. & Xu, C. An overview of the perception and mitigation of astringency associated with phenolic compounds. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 20, 1036–1074 (2021).

Frank, O., Zehentbauer, G. & Hofmann, T. Bioresponse-guided decomposition of roast coffee beverage and identification of key bitter taste compounds. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 222, 492–508 (2006).

Yeager, S. E. et al. Acids in coffee: a review of sensory measurements and meta-analysis of chemical composition. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 63, 1010–1036 (2023).

Gao, C., Tello, E. & Peterson, D. G. Identification of coffee compounds that suppress bitterness of brew. Food Chem. 350, 129225 (2021).

Lang, R. et al. Mozambioside is an Arabica-specific bitter-tasting furokaurane glucoside in coffee beans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 63, 10492–10499 (2015).

Lang, T. et al. Numerous compounds orchestrate coffee’s bitterness. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 6692–6700 (2020).

Czech, C. et al. Identification of mozambioside roasting products and their bitter taste receptor activation. Food Chem. 446, 138884 (2024).

Freitas, V. V. et al. Coffee: a comprehensive overview of origin, market, and the quality process. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 146, 104411 (2024).

Geromel, C. et al. Biochemical and genomic analysis of sucrose metabolism during coffee (Coffea arabica) fruit development. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 3243–3258 (2006).

Ginz, M. et al. Formation of aliphatic acids by carbohydrate degradation during roasting of coffee. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 211, 404–410 (2000).

Wang, X., Lim, L.-T. & Fu, Y. Review of analytical methods to detect adulteration in coffee. J. AOAC Int. 103, 295–305 (2020).

Gunning, Y. et al. 16-O-methylcafestol is present in ground roast Arabica coffees: implications for authenticity testing. Food Chem. 248, 52–60 (2018).

Cintineo, H. P. et al. Effects of caffeine, methylliberine, and theacrine on vigilance, marksmanship, and hemodynamic responses in tactical personnel: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 19, 543–564 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank Union Hand-Roasted Coffee (UHRC) and DR Wakefield for supplying several samples of unroasted Arabica and robusta coffee beans used in this study. This study was supported by the Amar-Franses & Foster-Jenkins Trust, the Sucafina coffee company and the Calleva Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.-J.R.H. and A.P.D. conceived the study. H.D. prepared the extracts for LC–MS analysis and undertook data analyses; G.C.K. acquired the LC–MS data for analysis; E.J.-S., and M.-J.R.H. carried out supporting analyses. E.J.-S., A.R.-B. and H.D. analysed the data, with A.R.-B. performing the statistical analyses. E.J.-S., M.-J.R.H. and A.P.D. wrote the paper. D.S., J.H and A.P.D undertook project management, fieldwork and sample collection. All authors contributed to the critical review of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jan-Smith, E., Downes, H., Davis, A.P. et al. Metabolomic insights into the Arabica-like flavour of stenophylla coffee and the chemistry of quality coffee. npj Sci Food 9, 33 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00398-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00398-8