Abstract

To utilize medium-chain triacylglycerol (MCT) with a low smoke point (~150 °C) in water, we investigated formulations and physical conditions for its spontaneous powdery crystallization without excipients. Crystallization of tricaprin and trilaurin mixed with medium- and long-chain triacylglycerols (MLCT) at varying ratios and temperatures was observed. Both oils mixed spontaneously crystallized into powder below their solidification temperature, structuring micrometer-ordered stacked plate crystals. Differential scanning calorimetry and X-ray diffraction measurements showed stable β−form polymorphism. Steric effects from the MLCT hindered fat crystal network formation, promoting lamellar structures that easily broke into porous crystals. Thermal energy and the van der Waals forces indicated that the excess carbon chains biased the horizontal development of the lamellar structures. The resulting powder had a finer particle size and increased bulkiness than commercial products. The tricaprin-based powder was wettable, forming a paste with water, while the trilaurin-based powder was not, making the tricaprin-based powder more suitable for food applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medium-chain triacylglycerols (MCTs), an edible lipid with a high energy value, are efficiently metabolized via the specific pathways in the human body1. Therefore, they are often formulated in specialized food provided for athletes in a training facility and patients in a hospital. However, in practical situations, the liquid-state highly concentrated MCTs possessing a low smoking point are not suitable for cooking with heat and tend to be mainly formulated into liquid-type food products, such as drinks and soups2. Such application limitations should be solved by powdering the oils, leading to the creation of corresponding semi-solid and solid-type products.

Powdering MCTs can be achieved by spray-drying, which is often applied to vegetable oils, but this process usually requires added sugar-based excipients3,4. On the other hand, spray chilling can be an excipient-free method5, but MCTs with a low melting point require much energy for processing, and the resulting powder crystals easily melt at room temperature. To prevent such a situation, high melting point long-chain triacylglycerols (LCTs) can be mixed to adjust the melting point6, but the LCT addition reduces the medium chain acid content. Alternatively, we found that medium- and long-chain triacylglycerols (MLCTs) were able to crystallize MCTs in a powdered state. This spontaneously powdered oil is expected to be industrially valuable as it can totally skip the powdering processes, such as spray drying and chilling. Whereas the simplified approach may contribute to no additives and energy saving, this kind of phenomenon has not been previously reported elsewhere.

In general, crystallization of triacylglycerol (TAG) proceeds in a multi-step manner as follows: once molten oil is cooled to a temperature below the melting point of the TAG, it becomes a supersaturation state toward nucleation7. After TAG molecules form stable nuclei under supersaturation, they grow into lamellae and associate with each other to form crystal nanoplatelets8. They aggregate into multi-layered stacks, randomly assembling to micrometer-ordered organized crystallites that cluster via van der Waals attractive forces9. The crystallites are further structured with the attractive forces to form crystals, resulting in a 3D crystal network10. In these crystal systems, the crystallization temperature significantly affects the driving forces of nucleation, crystal growth, and crystal polymorphism. The molecular characteristics of TAG, including the fatty acid composition and its position within the molecule, may also affect their packing and crystallization behavior, resulting in different crystal polymorphs11.

In the current study, in order to clarify the key to structuring the provided materials, the effects of MCT-MLCT-based TAG compositions and crystallization temperature conditions on the spontaneous crystallization behavior were systematically investigated. Macroscopic observation, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were conducted to analyze the obtained particles on various scales. In addition, the physical properties of the structured TAG powder were evaluated by visual observation and particle size analysis. The obtained data were accordingly correlated with the wettability and pasting ability of the prepared powder tested with water for use in a water-rich product.

Results and discussion

Fatty acid composition and CN distribution of oils and fats

The fatty acid composition and carbon number (CN) distribution of each material analyzed by GC are shown in the Supplementary Table 1a. C10-MCT comprised 99.5 wt% capric acid and 0.5% caprylic acid for the methyl-esterified state and consisted of 99.2 wt% CN30, 0.6 wt% CN28, and 0.2 wt% CN26 for the TAG state. These data indicate that CN30, 28, and 26 were molecular species C10-10-10, C10-10-8 and/or C10-8-10, and C10-8-8 and/or C8-10-8, respectively. C10-MLCT was dominated by 91.6 wt% capric acid and 8.4 wt% myristic acid and consisted of 79.9 wt% CN30 (C10-10-10), 18.7 wt% CN34 (C10-10-14 and/or C10-14-10), and 1.4 wt% CN38 (C10-14-14 and/or C14-10-14). These data ensured that C10 oils were designated molecules as expected, and the same confirmation can be applied to C12 oils.

Spontaneous crystallization behavior of the MCT-MLCT compounds

In a preliminary experiment for solidifying MCT oils, we found that an oil consisting of C10-MCT and C10-MLCT at a weight ratio of 6:4 spontaneously crystallized to be a powder at 20 °C after 24 h storage, whereas the blended oil stored at 5 °C became a bulk state (Fig. 1a(i)). The weight ratio and temperature conditions were accidentally found when handling the raw materials, while the rapid cooling at 5 °C is commonly used as the industrial refrigeration temperature and is likely to induce unstable polymorphism. SEM observations and XRD measurements revealed that the microstructure of the powdered C10-MCT and C10-MLCT blended crystals looked like aggregated small thin layers and the polymorphism was estimated to be β form, whereas those of the bulk crystals were totally rough and the polymorphism was β‘ form (Fig. 1a(ii)(iii)). These results indicate the importance of controlling the driving force for crystallization and polymorphism of the blended oil by cooling temperature. Not blended C10-MCT and C10-MLCT became bulk crystals and did not crystallize at 20 °C. (Fig. 1b(i) and c(i)). The crystal of C10-MCT alone was in a large bulk form with no specific microstructure, and the polymorphism was estimated to be β form. This result showed that the coexistence of other triglycerides (CN > 30) with CN30 (tricaprin) is probably the key to spontaneously forming a particulated crystal. These results strongly suggest that storage temperature and blending ratio affect crystallization behavior, and this phenomenon could be observed for another chain length of MCT oil.

a C10-MCT / C10-MLCT Blend. b Simple C10-MCT. c Simple C10-MLCT. Keys: C10-MCT = high purity tricaprin material, C10-MLCT= triacylglycerols material containing heterogeneous fatty acid species caprin-caprin-myristin. The temperatures are the storage conditions for crystallization. Macroscopic appearance was visually observed at 20 °C. Microscopic appearance was visualized via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at room temperature. The polymorphism of each crystal was estimated by X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurement.

TAG composition and temperature conditions for inducing spontaneous crystallization

In this experiment, we provided two oil species with different homogeneities of TAG species C10-MCT and C10-MLCT, blended at various ratios, and then stored at different temperatures ranging between 18 and 25 °C with β form seeding treatment to clarify the effects of the oil compositions and crystallization temperatures on spontaneous structuring. The analyzed CN distribution of the blended oils is shown in Suppl. Table 1b.

For C10-MCT, a visually observed typical crystallization behavior at 21 °C is presented in Fig. 2a(i). It shows that mixtures with 100-80 wt%, 70 wt%, 60–50 wt%, 40 wt%, and 30 wt% C10-MCT wholly crystallized into a solid bulk (S), a solid and powder mixture (S + P), a powder (P), a liquid and solid mixture (S + L), and remained liquid (L), respectively. The observations at all temperatures are summarized in Fig. 2a(ii). Mixtures containing 93.5 wt% of CN30 (C10-MCT 70 wt%) spontaneously crystallized into a powder form from 24 to 22 °C with a volume expansion ratio of 1.8 times or more (Fig. 2a(ii)). Those containing 91.5, 89.6, and 87.6 wt% of CN30 (C10-MCT 60–40 wt%) were structured as well, with volumetric indexes of 1.6 times or more from 22 to 20, between 21 and 19, and at 20 °C, respectively (Fig. 2a(ii)). These results indicate that powder-form crystals (P) can be obtained when crystals grow under conditions of lower supersaturation due to relatively high temperatures. From a phenomenological point of view, we can say that the difference in crystallization temperature can be read as the cooling rate, and that spontaneous powder formation occurs only when the driving force for crystallization, the cooling rate, is below a certain level. In the slow crystallization, there is room for MLCT molecules to enter the MCTs ones with a certain frequency and regularity, allowing the MCTs to be in a powder state.

a C10-MCT b C12-MCT. Keys: C10-MCT= high purity tricaprin material, C12-MCT= high purity trilaurin material. (i) Visually observed typical crystallization behaviors of C10-MCT and C12-MCT mixtures at 21 °C and 39 °C are presented. The symbols in the picture indicate the sample state solid bulk (S), powder (P), solid and powder mixture (S + P), liquid and solid mixture (S + L), and remaining liquid (L), respectively. (ii) The symbols and numbers in the table indicate the sample state and volume expansion rate of each homogeneous sample crystallized at various temperatures.

On the other hand, higher saturated monoacid TAG concentration samples containing 99.2, 97.3, and 95.4 wt% of CN30 (C10-MCT 100-80 wt%) showed only bulk crystals (S) or partial powder (S + P). The mixture with a lower CN30 concentration of 85.5% (C10-MCT 30 wt%) also did not turn into powder crystals. The results indicate that a specific TAG composition containing MLCT and temperature control is necessary to induce spontaneous powder crystallization. Because oils with low solid fat content have a lower melting point and lower crystallization driving force8, the increased ratio of C10-MLCT, whose melting point is lower than C10-MCT (Fig. 1c(i)), tends to increase the solubility of the high melting point TAG and suppresses driving force for its crystallization at the same temperature. As a result, the solidification points decreased with the addition of CN34 C10-MLCT, and the powder form crystal (P) is expressed in the diagonal tendency for CN vs. temperature. In previous studies, changes in supersaturation were reported to induce structural alterations in the network of TAG crystals, manifested as a reduction in the network density with a decrease in supersaturation12,13,14. From the current experiments, we considered that spontaneous crystallization can be induced under conditions where the degree of supersaturation is controlled by the crystallization temperature and TAG composition, and the driving force for crystallization is relatively suppressed.

In addition, mixtures of C12-MCT and C12-MLCT indicated in Fig. 2b were tested in the same way except for the temperature, and a similar diagram was obtained at higher crystallization temperatures (Fig. 2b). The reason for the different temperature settings was that the longer chain C12 oils crystallize at higher temperature than the C10 oils according to the enhanced van der Waals interactions.

Microscopic features of spontaneously structured crystals observed by SEM

The microstructure of a representative powdered sample consisting of 60 wt% C10-MCT, spontaneously crystallized at 20 °C, is shown in Fig. 3a. It is comparable to a bulk fat crystal formed at 18 °C with seeding treatment obtained from the previous experiment (Fig. 2a(ii)) and at a 5 °C cooling with no seeding. While the powder presented a multilayer structure with stacked thin plates (Fig. 3a(i)-A), the bulk crystals possessed relatively flat surfaces without specific architectures (Fig. 3a(i)-B, C). Almost the same microstructure was also universally observed for the C10 powdered crystals obtained at other blending ratios and crystallization temperatures. The same observation applied to the C12 oils, as shown in Fig. 3a(ii).

a Microstructure observed by scanning electron microscope (SEM). (i) C10-medium-chain triacylglycerol (MCT) (60 wt%) and C10-medium- and long-chain triacylglycerol (MLCT) (40 wt%) mixtures crystallized at 20 °C, 18 °C and 5 °C were subjected to SEM observation. (ii) C12-MCT (80 wt%) and C12-MLCT (20 wt%) mixtures crystallized at 39 °C, 35 °C and 5 °C were subjected to observation. b-1 Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) profiles. (i) C10-MCT (60 wt%) and C10-MLCT (40 wt%) mixtures crystallized at three different temperature conditions were subjected to DSC and XRD measurements. In each graph, from top to bottom, the waveforms are shown for spontaneously structured crystals at 20 °C, crystals solidified in bulk form at 18 °C, and bulk crystals obtained by cooling at 5 °C. (ii) Samples of C12-MCT (80 wt%) and C12-MLCT (20 wt%) blended crystal samples. In each graph, from top to bottom, the waveforms are shown for spontaneously structured crystals at 39 °C, crystals solidified in bulk form at 35 °C, and bulk crystals obtained by cooling at 5 °C. A DSC measurements were performed at a temperature increase rate of 2 °C/min from 5 °C to 60 °C. B XRD measurements were conducted at 5 °C during the measurement. The diffraction pattern was collected at a scan rate of 20 °/min, 2θ ranging from 0.8 to 30 with a step of 0.02˚. b-2 Melting points, long spacings, and short spacings determined by DSC and XRD measurements.

Polymorphism of spontaneously structured crystals characterized by DSC and XRD

To characterize the polymorphism of the spontaneously structured crystals, the same C10 and C12 crystals used for the SEM observations were subjected to DSC and X-ray diffraction measurements (Fig. 3b). For the DSC melting curves, the C10 spontaneously powdered crystals had a sharp peak and shoulder peak, with each melting point 28.89 °C and 21.14 °C and the C10 bulk crystals formed at 18 °C also possessed similar melting points at 28.34 °C and 21.06 °C (Fig. 3b-1(i)(A) and b-2). These crystals were judged to be β form because the melting point of the β form of homogeneous tricaprin is at 31.5 °C15,16,17, and the heterogeneity of C10-10-10 as affected by the presence of C10-10-14 likely lowered it. On the other hand, the bulk crystals obtained by rapid cooling at 5 °C showed a lower melting point at 14.31 °C (Fig. 3b-1(i)(A) and b-2). In addition, slight exothermic peaks and subsequent melting peaks were observed at 22.75 °C and 27.53 °C (Fig. 3b-1(i)(A) and b-2), which means that they were accompanied by polymorphic transitions during the measurement. These results indicate that the polymorphism of the bulk crystal obtained at 5 °C cooling was in an unstable form.

X-ray diffraction measurements showed that the C10 spontaneously powdered crystals and bulk crystals obtained at 18 °C indicated a long spacing value of 2.7 nm and strong short spacing spectra of 0.46 nm; therefore, they were estimated to be β form crystals18 (Fig. 3b-1(i)(B) and b-2). In contrast, the C10 bulk crystal obtained by 5 °C cooling indicated a peak with a lamella distance of 2.8 nm and short spacing at 0.42 and 0.38 nm, which showed a metastable β’ form crystal (Fig. 3b-1(i)(B) and b-2).

The melting point of the spontaneously structured C12 crystal was at 44.33 °C, which is close to the melting point of the β form crystals of trilaurin (46.5 °C)16,17,19, and the bulk crystal formed at 35 °C also had a similar melting point 43.56 °C (Fig. 3b-1(ii)(A) and b-2). On the other hand, the first melting peak of the C12 bulk crystal obtained from 5 °C cooling showed a lower melting point at 30.82 °C (Fig. 3b-1(ii)(A) and b-2). In addition, slight exothermic peaks and a second melting peak were observed at 40.45 °C by polymorphic transition during the measurement (Fig. 3b-1(ii)(A) and b-2). The XRD spectra of C12 spontaneously structured crystals and bulk crystals formed at 35 °C were similar to the β crystals of trilaurin, whereas the 5 °C cooled bulk crystal was in the more unstable β’ forms18,19 (Fig. 3b-1(ii)(B) and b-2).

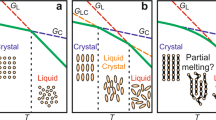

On the basis of the data obtained above, we discuss the key to structuring the provided materials to become a powder. Polymorphic analysis of the spontaneously structured crystals by DSC and XRD suggests that β form crystals of the C10 and C12 mixtures can form a specific structure to be a powder. However, several solid bulk crystals prepared under different temperatures (Fig. 2a) possessed β form polymorphism, which was clarified via another XRD analysis (data not shown). Therefore, we can conclude that the polymorphism of the oil mixtures on a nanometer scale is not an exclusive factor determining the powder state of the provided oils. Meanwhile, the SEM observation revealed that the spontaneously particulated C10 and C12 oils appeared to be multi-layered micrometer-ordered crystallites constructed with many stacks. They seemed not to evolve into the 3D crystal network, presumably because of insufficient attractive driving forces on a colloidal scale between 10−6 and 10−9 μm against enhanced hindering steric effects caused by the added MLCT molecules. Considering that the provided systems consisted of almost pure TAG molecules and the surrounding air, the driving forces can be mostly explained by the intermolecular van der Waals forces and hydrophobic interactions between the molecules that minimized the oil–air interface. Both forces originating from the C10 and C12 oil molecules are relatively lower than those from long-chain TAG molecules such as C16 and C18.

To prove this speculation, we again conducted spontaneous crystallization tests for C16 and C18 materials containing slightly heterogeneous TAG molecules and found that the formed crystals, slightly under the melting points, expanded and were, not spontaneously but easily, broken into a powder with the support of mild shear stresses. There could be a switching point in the carbon chain lengths from 12 to 16 on the balance between the heterogeneity-triggered steric hindrance effects and the attractive forces that decide the molecular evolution for the 3D networks.

Physical characterization of the MCT powders

The macroscopic physical properties of spontaneously powdered crystals were compared with those of commercial powder products named “MCT powder” and “NR-100”, mainly consisting of caprylic and capric acid MCT oil with excipients and fully hydrogenated rapeseed oil, respectively (Fig. 4a). Spontaneously structured C10 crystals and the commercial MCT powder were of lower aerated bulk density, spontaneously structured C10 and C12 crystals were of lower packed bulk density than the others, and compressibility calculated from the two parameters was in the order of NR-100 < C12 < MCT = C10. Larger angles of repose and specific surface areas were observed for the spontaneously powdered crystals than for the commercial products. These differences could be attributed to the size distributions and packing states of the particles.

a Powder characteristics. b Particle size distribution. Particle sizes of spontaneously structured powders and NR-100 were measured in the wet mode, and medium-chain triacylglycerol (MCT) powder was measured in the dry mode to avoid dissolution in the solvent. c Mixing behavior with water. (i) Appearance after manually mixing 30 wt% of each powder with 70 wt% deionized water. (ii) Contact angle of each powder with water (n = 10). Powdered oil crystals were compressed to form a flat surface, to which an aliquot of water (3 μL) was dropped for measurement. Commercial MCT powder could not be measured because of water soaking into the powder.

Particle size distributions of the powders and their representative characteristics (mean, mode, median, and microscopic image by SEM) are shown in Fig. 4b. Spontaneously structured C10 and C12 crystals and NR-100 were subjected to particle size analysis under wet conditions, and the commercial MCT powder under dry conditions because it contained swelling excipients leading to an artifact. The particle size distributions generally followed a log-normal distribution with a slightly shouldered monomodal peak. The average particle sizes of spontaneously powdered crystals were approximately ten times smaller than those of manufactured crystals. The particle shape of both commercial products was spherical, certainly because they were manufactured by spray-drying or spray-chilling, where the surface tension often dominantly determines the shape20.

The larger angle of repose of the spontaneously powdered crystals is expected to be due to the higher drag forces, such as cohesive force, than driving forces, such as gravitational force. Because cohesion is a surface phenomenon, finer particles with a high surface-to-mass ratio are more cohesive than coarser particles. Particle shape also affects flow properties, with spherical particles possessing the minimum interparticulate contact area, whereas plate-shaped particles have a larger contact area, resulting in poor flowability21. The spontaneously powdered crystals therefore interacted more strongly with each other between particles than those of commercial products.

Pasting properties of the MCT powders

To examine the applicability of spontaneously powdered crystals to the food industry, we observed the mixing behavior of the MCT crystal powders with water and compared them with two commercial products. When the provided oils and water were manually mixed with a stainless-steel spoon in a beaker at a weight ratio of 3:7 for 30 s, spontaneously structured C10 powder formed a non-flowing paste with no clearly visible flowing water (Fig. 4c). On the other hand, the oil and water mixture at 2:8 did not form a stable paste and quickly separated into the two phases, indicating that 70 wt% water content paste was successfully prepared in the visual base. The more accurately measured free water, as dependent on the different water contents, is shown in Suppl. Fig. 1. The pastes formed at 4:6 remained in the mixed state for a minimum of several days, demonstrating that the mixing powder/water ratio of 4:6 and higher powder contents are suitable for products to be consumed within several days. Commercial MCT powder containing excipients was finely dispersed in water to form a suspension and flowed under gravity (Fig. 4c). Spontaneously structured C12 powder and commercial powder NR-100 mainly composed of tristearin were not dispersed into water (Fig. 4c). The different behavior to water can be attributed to the larger contact angle of 125.8°, compared to 110.4° of the C10 powder. However, since the contact angle is one of the factors that can explain the dispersion properties with water, further studies were required to elucidate the factors that decisively affect the macroscopic phenomena.

Summary and hypothesizing the mechanisms of spontaneous granulation

In summary, as an overall discussion on the mechanisms of spontaneous granule formation, we can highlight the significance of the following three key physicochemical phenomena that contribute to spontaneous granule formation described in the introduction part: (i) the regulated incorporation of MLCT molecules into the lamellar structure of the crystal nanoplatelets, (ii) the occupation of MLCT molecules on the surface of the crystal nanoplatelets, and (iii) the balance between thermal motion and van der Waals forces that affects the formation of the multi-layered stacks. These phenomena are primarily influenced by factors such as (i) the crystallization temperature, which is slightly below the melting point, (ii) the mixture ratio of MLCT and MCT molecules (~5–10 wt%), and (iii) the difference in the carbon chain length between the MLCT molecules and the MCT molecules (four carbon atoms), respectively.

In particular, to clarify the role of the MLCT molecules, we should discuss the developments of the multi-layered stacks based on the thermal energy and the van der Waals force, related to the mentioned (iii) above.

At room temperature (T = 300 K), thermal energy Et can be approximated using Boltzmann’s constant according to Eq. (1)22:

The thermal energy \({E}_{t}\) (T) can be estimated to be 4.14 × 10−21 J for the crystal nanoplatelets.

When two flat surfaces, such as those of microcrystals, are separated by a distance d, the van der Waals interaction energy per unit area \({E}_{V}\) is given by Eq. (2)23:

where H is the Hamaker constant, typically around 10−19 J for organic materials24. Assuming that d = 0.616 nm (four carbon chain lengths), the van der Waals interaction energy can be computed as –0.00699 J/m². For a nanoplatelet with a side length of 5 nm25, for example, the area is 25 × 10−18 m². The total van der Waals energy at the final state (0.616 nm separation) is estimated to be –1.75 × 10−19 J.

Under the estimated situations \({E}_{t}\) (T) << \({E}_{V}\) (d), the multi-layered stacks of the crystal nanoplatelets are expected to continuously evolve in a time-course manner. This estimation is consistent with the fact that we have observed the multilayered stacks and micrometer-ordered organized crystallites by microscopy. At this stage, we should consider why the growth of micrometer-ordered organized crystallites stopped at a critical point, not to be the 3D network. We can speculate that the excess carbon chain does not prevent the horizontal development of the lamellar, but prevents the vertical accumulation of the lamellar. This highly biased lamellar structuring can proceed until the free molecules are fully incorporated into the crystal nanoplatelets, which can form quite porous oil crystals that are easily broken down to the granular states. It should be noted that such a discussion is possible due to the highly homogenous MCT and MLCT oils provided.

As a conclusion, MCT and MLCT oils consisting of homogeneous tricaprin (C10-10-10) and heterogeneous TAGs (C10-10-14 & C10-14-14) at weight ratios from 93.5:6.5 to 87.6:12.4 spontaneously crystallized to be a powder 1–3 °C below the solidification temperature around 19–24 °C. Visually observable melted oils completely disappeared from the created system. Similar results were obtained for homogeneous trilaurin (C12-12-12) and heterogeneous trilaurin (C12-12-18, C12-12-20 & C12-18-18) from 96.2:3.8 to 90.2:9.8 wt% spontaneously crystallized around 36–41 °C. On the other hand, solid bulk crystals, not powders, were formed with simple homogeneous TAGs (C10-10-10 & C12-12-12). These data apparently indicate that controlling the degree of supersaturation by adding slightly heterogeneous TAG species to a saturated monoacid MCT and adjusting the crystallization temperature promotes the formation of spontaneously powdered oils.

Microscopic observations demonstrated that the tricaprin- and trilaurin-based powdered crystals possessed a stacked structure of micrometer-order plate crystals on a colloidal scale, maybe in a suspended state during crystal growth. DSC and XRD analysis revealed that the polymorphism of the spontaneously structured platelet crystals was β form on a molecular scale, similar to bulk crystals obtained under slowly cooling conditions rather than rapidly cooling conditions. These results strongly suggest that the multi-layered structure in the stable β form no longer evolves into the oil crystal network usually seen in common bulk crystals because of the insufficient colloidal-scale attractive driving forces to gather that minimize the oil-air interface against hindering steric effects caused by the added MLCT molecules. However, via the calculation of thermal energy and the van der Waals forces, the possible growth to a 3D network with micrometer-ordered, organized crystallites cannot be rejected. Therefore, we proposed a possible hypothesis that the excess carbon chain does not prevent the horizontal development of the lamellar, but prevents the vertical accumulation of the lamellar, which leads to easily broken porous crystals on a macroscopic scale. Although spontaneously structured crystals possessed lower packed bulk density, larger specific surface area, and higher angle of repose than the commercial products, no clear tendency was observed for aerated bulk density and compressibility. The clarified physical characteristics of the structured crystals can be attributed to the size distributions and packing states of the particles, i.e., the crystals had smaller particle sizes than the commercial products. In addition, whereas the C10 powder was wettable and able to be mixed with water at a weight ratio of 3:7 to form a paste-like structure and was kinetically stable for several hours, the C12 powder was not wettable and therefore did not form a paste when mixed with water. The C10 powder was more suitable for water-rich cooking.

Methods

Materials

Special grade TAGs consisting of homogenous fatty acid species, tricaprin caprin-caprin-caprin (named as C10-MCT) (C10-10-10 purity >99.0 wt%) and trilaurin laurin-laurin-laurin (C12-MCT) (C12-12-12 purity >99.0 wt%), were produced by The Nisshin OilliO Group, Ltd (Tokyo, Japan) and Yashiro Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), respectively. The same grade TAGs containing heterogeneous fatty acid species, caprin-caprin-myristin (C10-MLCT) (product name: RMK-10, containing C10-10-10 and C10-10-14 at a weight ratio of 80:20) and laurin-laurin-stearin (C12-MLCT) (product name: RMK-12, containing C12-12-12 and C12-12-18 at a weight ratio of 80:20) were manufactured by Yashiro Co., Ltd. The chemical compositions were validated in the results section.

Commercial powdered MCT (product name: MCT powder) consisting of caprylic and capric acid MCT oil, dextrin, and modified starch and commercial powdered long chain TAGs (product name: NR-100) consisting only of fully hydrogenated rapeseed oil were obtained from The Nisshin OilliO Group, Ltd. and Riken Vitamin Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Deionized water was produced using a water purification system (G series, Organo Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Chemical analysis of fatty acid composition and CN distribution of oils and fats

For the fatty acid composition analysis, fatty acid methyl esters were prepared from TAG samples using the following standard JOCS method 2.4.1.2-2013 (Boron Trifluoride-Methanol Method). In brief, 20 mg of TAG samples and 1 mL of 0.5 M NaOH–methanol solution were placed into a screw cap glass tube and saponified for 7 min at 100 °C. The saponified samples were mixed with 1 mL of 14 wt% boron trifluoride in methanol solution and heated at 100 °C for 5 min to induce the formation of fatty acid methyl esters. The esters were extracted with 5 mL of n-hexane and washed with saturated saline to promote extraction. The extracted esters were analyzed by gas chromatography (GC) with an FID detector (Agilent 7890 A GC system, Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) using a TC-70 column (60 m length × 0.25 mm inner diameter × 0.25 μm film thickness, GL Science Inc., Tokyo, Japan) under the following conditions: Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.1 mL/min. The column temperature was programmed in the range from 150 to 250 °C at a rate of 3 °C/min. The injector and detector temperatures were set at 250 °C and 260 °C, respectively. The split ratio was set at 50:1.

To analyze the CN distribution, TAG samples were prepared according to the standard JOCS method 2.4.6.1-2013. In brief, 10 mg of TAG samples were diluted with 1.5 mL hexane for GC analysis. The prepared samples were analyzed with a GC-FID system (GC-2010 Plus, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) using a DB-1HT column (5 m length × 0.32 mm inner diameter × 0.10 μm film thickness, Agilent Technologies) as follows: Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 3.0 mL/min. The column temperature was programmed in the range from 200 to 370 °C at a rate of 15 °C/min. The injector and detector temperatures were set at 370 °C. The split ratio was set at 50:1.

Preparation of the MCT crystals

For preparing seed crystals, all MCT and MLCT materials were heated in a water bath at 80 °C until completely melted. Homogeneous C10-MCT and C12-MCT were mixed with the corresponding C10-MLCT and C12-MLCT at a weight ratio of 6:4 and 8:2 in a glass beaker, respectively. The 3.0 g of melted mixtures of the C10 and C12 oils were poured into a glass vial and placed in an atmosphere-controlled incubator (FMU-054I, Fukushima Galilei Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan) at 20 °C for the C10 oil and 39 °C for the C12 oil to obtain powdery β form crystals. The stable polymorphic crystals (Suppl. Fig. 2) were used as seed crystals to control the polymorphism of the provided MCT oils in the following crystallization.

For analyzing spontaneous crystallization behavior, the C10 and C12 oils were melted in the same manner and mixed at homogeneous MCT weight ratios from 100% to 30% and from 100% to 40% in a glass beaker, respectively. The melted mixtures were cooled to 27 °C for the C10 mixture and 43 °C for the C12 mixture in a water bath with an added seed crystal (0.05 wt%) prepared by the above-referenced procedures. An aliquot (1 mL) of the seeded mixtures was quickly transferred to another glass tube and placed in the atmosphere incubator for 18 h. The temperature ranged between 18 and 25 °C for the C10 samples and between 35 and 42 °C for the C12 samples for crystallization.

Evaluation of the spontaneous crystallization behavior of MCTs

The physical states of the crystals were judged by visual observation to categorize them into liquid (L), solid (S), and powder (P). The volumetric change was expressed as the height ratio of an incubated sample to the initial one.

Microstructure observation of the MCT crystals

The solid and powdered states of the samples were subjected to microscopic observation by SEM (JSM-7500F, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The specimens were coated with an osmium plasma coater OPC-80 (Nippon Laser & Electronics Lab., Nagoya, Japan) and observed at acceleration voltages of 2 and 5 kV.

Morphological analysis of the MCT crystals

The morphological states of the obtained powdered samples were determined by melting behaviors and lattice structures via DSC and XRD measurements. The melting behaviors of oil crystals were analyzed using a DSC instrument equipped with a data processing system, DSC 600, and software for NEXTA (Hitachi High-Tech Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Approximately 3 mg of each sample was weighed in an aluminum pan and tightly sealed with an aluminum lid. Then, each sample was heated from 0 to 60 °C at an elevating rate of 2 °C/min. The endothermic enthalpy was recorded with a sealed empty pan as a reference to identify the onset, peak top, and offset temperatures. The onset value was determined and considered as the melting initiation temperature. The lattice structures of the crystals, the regular and repeating arrangement of atoms or molecules, were analyzed by XRD patterns using XRD equipment (SMART LAB, Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with Cu Kα radiation source. The powdered sample was flatly spread on a sample holder for measurement. The diffraction pattern was collected at a scan rate of 20 °/min, between a range of 2θ from 0.8 to 30 with a step size of 0.02, with a voltage of 45 kV and a current of 200 mA.

Preparation of the MCT powders

The homogeneous C10 and C12 MCT oils (C10-MCT and C12-MCT) pre-melted at 80 °C were mixed with the heterogeneous C10 and C12 oils (C10-MLCT, and C12-MLCT) pre-melted at the same temperature at a weight ratio of 6:4 for the C10 oils and 8:2 for the C12 oils in a glass beaker, respectively. The mixtures were cooled to 27 °C in a water bath for the C10 mixture and 43 °C for the C12 mixture, and then blended with the seed crystal (0.05 wt%) prepared above. The seeded mixtures (200 g) were quickly transferred to a polyethylene plastic bag and then placed in the atmosphere-controlled incubator at 20 °C for the C10 mixture and 39 °C for the C12 mixture for 24 h, resulting in spontaneously powdered crystals.

Evaluation of the MCT powder properties

Angle of repose, aerated density, packed density, and compressibility of the powder samples were evaluated using a comprehensive powder tester (PT-X, Hosokawa Micron Corporation, Osaka, Japan). Samples were fed through a sieve with a 710 μm aperture to collapse the aggregates. The packed density was measured after 180 tapings. In addition, the specific surface area was measured by nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms (BET analysis) using a 3Flex high-performance adsorption analyzer (Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA). The samples were degassed at room temperature for 24 h using a VacPrep 061 vacuum equipment (Micromeritics) before measurement.

The particle size of the crystals was measured by the laser diffraction scattering method using a Microtrac MT3300EXII analyzer (Nikkiso Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in wet mode. Samples were dispersed in deionized water with a neutral detergent as a dispersant (Natural palm oil detergent; Settsu Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) to dissociate aggregates and subjected to mild ultrasonic treatment (Aiwa Ultrasonic Cleaner FU-16C; Aiwa Medical Industry, Tokyo, Japan) for 30 s before measurement to dissociate aggregated particles. Those of the commercial MCT powder coated with the hydrophilic excipients dextrin and modified starch were measured in a dry mode with compressed air under a dispersion pressure of 0.3 MPa.

Contact angles to water were measured using a DMo-502 contact angle meter and analyzed using the FAMAS software (Kyowa Interface Science Co., Ltd., Saitama, Japan). For sample preparation, powdered oil crystals were compressed to form a flat surface, to which an aliquot of water (3 μL) was dropped, and the contact angle was measured.

Evaluation of the pasting properties of the MCT powders

A total of 50 g of C10 powder and water were mixed with different weight ratios between 4:6 to 2:8 in a glass beaker for 30 s to prepare a paste. Approximately 6 g of the prepared paste was weighed into a plastic cup, covered with a lid, and stored in an atmosphere-controlled incubator at 20 °C. The water release from the paste was visually observed, and the rate was evaluated by measuring the weight of water that flowed out of the paste. The percentage of water released to the total water content over time for each paste was calculated.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate with freshly prepared samples. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel version. 2020 for Windows.

Data availability

Data available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Takeuchi, H., Sekine, S., Kojima, K. & Aoyama, T. The application of medium-chain fatty acids: edible oil with a suppressing effect on body fat accumulation. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 17 (2008).

Newport, M. T. The Coconut Oil and Low-Carb Solution for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Other Diseases: A Guide to Using Diet and a High-Energy Food to Protect and Nourish the Brain (Turner Publishing Company, UK, 2015).

Turchiuli, C. et al. Oil encapsulation by spray drying and fluidised bed agglomeration. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 6, 29–35 (2005).

Matsuura, T. et al. Effect of dextrose equivalent of maltodextrin on the stability of emulsified coconut-oil in spray-dried powder. J. Food Eng. 163, 54–59 (2015).

Okuro, P. K., de Matos Junior, F. E. & Favaro-Trindade, C. S. Technological challenges for spray chilling encapsulation of functional food ingredients. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 51, 171 (2013).

Liu, J. et al. MCT/LCT mixed oil phase enhances the rheological property and freeze-thawing stability of emulsion. Foods 11, 712 (2022).

Tran, T. & Rousseau, D. Influence of shear on fat crystallization. Food Res. Int. 81, 157–162 (2016).

Acevedo, N. C. & Marangoni, A. G. Characterization of the nanoscale in triacylglycerol crystal networks. Cryst. growth Des. 10, 3327–3333 (2010).

Acevedo, N. C., Peyronel, F. & Marangoni, A. G. Nanoscale structure intercrystalline interactions in fat crystal networks. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 16, 374–383 (2011).

Walstra, P., Kloek, W., & van Vliet, T. Fat crystal networks. In: N. Garti, & K. Sato (Eds.), Crystallization Processes in Fats and Lipids, pp. 289–328. (Marcel Dekker, New York, 2001).

Sato, K. Crystallization behaviour of fats and lipids—a review. Chem. Eng. Sci. 56, 2255–2265 (2001).

Ahmadi, L., Wright, A. J. & Marangoni, A. G. Chemical and enzymatic interesterification of tristearin/triolein-rich blends: chemical composition, solid fat content and thermal properties. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 110, 1014–1024 (2008).

Rodríguez, A., Castro, E., Salinas, M. C., López, R. & Miranda, M. Interesterification of tallow and sunflower oil. J. Am. Oil Chemists Soc. 78, 431–436 (2001).

Rousseau, D., Hill, A. R. & Marangoni, A. G. Restructuring butterfat through blending and chemical interesterification. 2. Microstructure and polymorphism. J. Am. Oil Chemists’ Soc. 73, 973–981 (1996).

Lutton, E. S. Review of the polymorphism of saturated even glycerides. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 27, 276–281 (1950).

Walstra P. Crystallization. In: Physical chemistry of foods. pp. 583–649. (Marcel Dekker, New York, 2003).

Cholakova, D., Tcholakova, S. & Denkov, N. Polymorphic phase transitions in bulk triglyceride mixtures. Cryst. Growth Des. 23, 2075–2091 (2023).

McGauley S. E., & Marangoni A. G. Static crystallization behavior of cocoa butter and its relationship to network microstructure. In: Marangoni A. G., Narine S. S. (Eds.), Physical properties of lipids. pp. 84–122. (Marcel Dekker, New York, 2002).

Takeuchi, M., Ueno, S. & Sato, K. Synchrotron radiation SAXS/WAXS study of polymorph-dependent phase behavior of binary mixtures of saturated monoacid triacylglycerols. Cryst. Growth Des. 3, 369–374 (2003).

Breinlinger, T., Hashibon, A. & Kraft, T. Simulation of the influence of surface tension on granule morphology during spray drying using a simple capillary force model. Powder Technol. 283, 1–8 (2015).

Aulton M. E. Powder flow. In: Micheal E., Aulton M. E., Taylor K. M. G. (Eds.), Aulton’s pharmaceutics E-book. 5th edn. pp. 189–200. (Elsevier, UK, 2018).

Israelachvili A. N. Intermolecular and surface forces. In: Intermolecular and Surface Forces, 3rd Edn. Chapter 2. pp. 23–52. (Academic Press, USA, 2011).

Israelachvili A. N. Intermolecular and surface forces. In: Intermolecular and Surface Forces. 3rd Edn. Chapter 11. pp. 205–222. (Academic Press, USA, 2011).

Ogwu A., Darma T. H. Optical and surface energy probe of Hamaker constant in copper oxide thin films for NEMS and MEMS stiction control applications. Sci. Rep. 11, 4276 (2021).

De Witte, F. et al. From nucleation to fat crystal network: effects of stearic–palmitic sucrose ester on static crystallization of palm oil. Foods 13, 1372 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by The Nisshin OilliO Group, Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.K.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing–original draft preparation, and review and editing. H.U.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing–review, and editing. K.M.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing–original draft preparation, and review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Two authors are affiliated with The Nisshin OilliO Group, Ltd., which funded this study. This affiliation did not influence the study’s design, results, or interpretation. All authors declare that they have no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kataoka, Y., Uehara, H. & Matsumiya, K. Spontaneous granulation of tricaprin and trilaurin medium-chain triacylglycerols with added medium- and long-chain species. npj Sci Food 9, 149 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00511-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00511-x