Abstract

Evidence linking the dietary inflammatory index (DII) to health outcomes remains inconsistent and limited. This study assessed the associations between DII and 845 health outcomes (N = 78,390 to 207,832), identifying 133 outcomes significantly associated with DII after multiple comparison correction (PFDR < 0.05). Most of these health outcomes pertained to the digestive, circulatory, and endocrine/metabolic systems. Using the genetic instrument rs7910002, significantly associated with DII at the genome-wide level (P < 5 × 10−8), Mendelian randomization (MR) phenome-wide association analysis (N = 121,978 to 315,586) revealed significant associations between DII and 25 health outcomes (PFDR < 0.05). Consistent effects of DII on seven health outcomes were observed in the above analyses. Subsequently, two-sample MR analysis confirmed that higher DII increased the risk of abdominal hernia, cholelithiasis, and back pain. Our study comprehensively assessed the health effects of DII and highlighted the importance of anti-inflammatory diets for disease prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diet is a crucial and modifiable contributor to the global prevalence of multiple chronic diseases1,2. It has been reported to be linked to altered risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, mental health issues and mortality3,4,5,6. Several potential mechanisms, including inflammation, modulation of gut microbiota, regulation of oxidative stress, and alterations in metabolites and lipid profiles, may be driven by diet to affect chronic disease risk7,8,9. Previous studies have indicated that adhering to healthy dietary patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension, was associated with reduced levels of inflammatory markers10,11. However, the Western diet, characterized by high intake of fried foods, red and processed meat, and high-fat dairy products, typically could result in increases in inflammatory markers and higher risks of adverse outcomes12,13. This observation highlights the role of diet-induced inflammation in disease development and supports the hypothesis that diet can influence major health outcomes by modifying inflammatory status.

Dietary inflammatory index (DII) is an innovative tool designed to estimate the inflammatory properties of individual diets14. Drawing from previous literature on the effects of foods on inflammatory markers (IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α and CRP), the DII scoring algorithm incorporates forty-five food parameters (e.g., vitamin B12, cholesterol and alcohol). A higher DII score indicates a more inflammatory diet, while a low score reflects an anti-inflammatory dietary pattern rich in antioxidants and fiber15. Statistically significant associations of DII with myocardial infarction, cancer risk, and all-cause mortality have been reported in previous studies16,17,18. Nevertheless, there is inconsistency for these observed associations and a dearth of evidence regarding associations with other health outcomes. This emphasizes the necessity of a phenome-wide analysis to systematically evaluate the effects of DII on health outcomes, especially in prospective cohort studies. Besides, potential unmeasured or uncontrolled confounders are unavoidable in observational studies, limiting the investigation of causal associations between the DII score and health outcomes.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have confirmed that dietary intake is influenced by genetic variants, such as locus in DRAM1 and RARB, which are associated with macronutrient intake19,20. Mendelian randomization (MR), using genetic variants from GWAS, is an epidemiological approach to perform causal inference. However, there is no study analyzing the effects of genetic variants on DII, which restricts the feasibility of conducting MR analysis. Hence, it is necessary to conduct MR analysis using instrumental SNPs from GWAS to comprehensively reveal the health effects of DII within a phenome-wide framework. Phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) is a hypothesis-free design that facilitates in-depth exploration of the relationship between exposure and multiple phenotypes, thereby contributing to the improvement of understanding for diseases incidence and development21.

Therefore, to gain a comprehensive knowledge of the effects of DII on health outcomes, we first estimated the association of DII with health outcomes in a large-scale prospective cohort study. Besides, to reveal the causal relationship between DII and health outcomes, we performed a GWAS analysis and subsequently conducted phenome-wide Mendelian randomization analysis (MR-PheWAS). Furthermore, the two-sample MR analysis was carried out as a replication analysis.

Results

Characteristics of participants

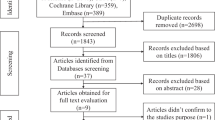

The DII scores were calculated among 210,960 participants, of whom 3072 participants were excluded for failing to report covariate data (Fig. 1). The majority of the participants was white, accounting for 95.85%. A total of 82,005 (39.45%) participants were identified as having an anti-inflammatory diet, and 56,259 participants (27.06%) had a pro-inflammatory diet (Supplementary Table S1). The participants with anti-inflammatory diet tended to be non-smokers and had low levels of BMI. In contrast, the participants in the pro-inflammatory group were more likely to be younger, female, have higher BMI levels, and engaged in less frequent physical activity. We compared baseline characteristics between participants with and without available DII data to assess potential selection bias. No substantial differences were observed between two groups in terms of age, sex, BMI, smoking, or drinking status (Supplementary Table S2).

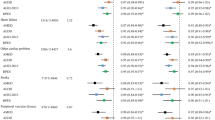

Cohort study

We investigated the association of DII with a total of 845 health outcomes, which were classified into 16 disease categories (Supplementary Table S3). Over a mean follow-up of 12.70 years, the number of cases for individual outcomes ranged from 200 to 39,003. The Cox regression suggested that the DII score was associated with the risk of 133 health outcomes (PFDR < 0.05). Most of these health outcomes were related to digestive, circulatory, and endocrine/metabolic systems (Fig. 2, details are shown in Supplementary Table S3). For instance, DII score was positively associated with the risk of tobacco use disorder (HR, 1.05, 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.06, PFDR = 9.83 × 10−13). Besides, we observed the risk effect of per DII score increment on cholelithiasis and cholecystitis (HR, 1.05, 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.06, PFDR = 8.25 × 10−11). A higher DII level was related to an increased incidence of cerebrovascular disease (HR, 1.04, 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.05, PFDR = 3.36 × 10−7), consistent with the association observed in participants with pro-inflammatory DII level compared to those with normal DII score (Supplementary Table S4). These associations remained stable in sensitivity analyses, involving replication analysis with E-DII (Fig. 2, details are shown in Supplementary Table S5), exclusion of participants diagnosed within two years during the follow-up period (Supplementary Table S6), and restriction to individuals of White ethnicity, respectively (Supplementary Table S7).

The top half part of the figure represents the health effects of DII, and the half bottom of the figure represents the health effects of E-DII. The y-axis represents the –log₁₀ transformation of P values that have been adjusted for multiple comparisons via the FDR method. DII dietary inflammatory index, E-DII energy-adjusted dietary inflammatory index, FDR false discovery rate.

Phenome-wide Mendelian randomization study

To comprehensively elucidate the effects of DII on health outcomes, we first conducted a GWAS to identify the genetic variants associated with DII. The heritability of DII was estimated to be 2.31% (P = 2.91 × 10−31). Notably, SNP rs7910002 (P = 1.30 × 10−9, G allele beta = 0.052) was found to be independently associated with DII (P < 5 × 10−8; Fig. 3A). As presented in Supplementary Table S8, previous GWAS has found that it was associated with serval traits (e.g., BMI, weight, calcium levels, albumin). Gene analysis revealed five genes (ANKRD31, SKIDA1, MLLT10, CACS10, and DNAJC1) that reached statistical significance (Fig. 3B). Besides, chromatin binding was the top-associated gene-set22, but did not achieve a significant level after FDR adjustment (nominal P = 1.37 × 10−5, PFDR = 0.233; Supplementary Table S9).

A The Manhattan plot of the DII-GWAS; B the Manhattan plot of gene analysis based on DII-GWAS. The x-axis denotes chromosome and position, and the y-axis represents the –log₁₀ transformation of P values. DII dietary inflammatory index, E-DII energy-adjusted dietary inflammatory index, GWAS genome-wide association study.

Using the single SNP related to DII, we conducted a weighted GRS for the representation of the DII score (Supplementary Fig. S1). We evaluated the association between DII-GRS and 1165 health outcomes, with the number of cases ranging from 200 to 89,024 (Supplementary Table S10). Of these, higher genetically predicted DII level was associated with an increased risk of 25 health outcomes, which are related to circulatory, digestive, endocrine/metabolic, genitourinary, injuries, neoplasms, respiratory, and symptoms systems (Table 1). The genetically predicted DII level showed a significant association with overweight, obesity and other hyperalimentation (OR, 3.50; 95% CI, 3.08 to 3.93; PFDR = 5.84 × 10−6). Besides, a notable positive association was found between genetically predicted DII level and cholelithiasis (OR, 3.43; 95% CI, 2.93 to 3.92; PFDR = 3.35 × 10−4).

Summary evidence and verification in two-sample MR analysis

We eventually identified 205 health outcomes exhibiting significant associations with DII (nominal P value < 0.05 or PFDR < 0.05), consistently observed in both cohort study and MR-PheWAS. As shown in Fig. 4, seven health outcomes and 26 health outcomes were respectively classified as convincing evidence and suggestive evidence (details are presented in Supplementary Table S11). Furthermore, we conducted the two-sample MR analysis to replicate the associations belonging to the convincing group (Level I). Given the discrepancies in health outcomes definitions in the FinnGen cohort, five out of seven health outcomes (chronic bronchitis, abdominal hernia, cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, and back pain) were available for two-sample MR analysis. The number of cases for these outcomes ranged from 1262 to 16,839 (Supplementary Table S12). The DII variance explained by rs7910002 was 0.12%, with an F-statistic of 163, indicating a low risk of weak instrument bias. Detailed SNP information is presented in Supplementary Table S13. Using the Wald ratio method, the increment in DII score was associated with a 2.34-fold, 2.38-fold, and 1.54-fold higher risk of back pain, abdominal hernia, and cholelithiasis, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Columns are annotated by PheCODE. The heatmap colors represent effect estimates from MR-PheWAS and cohort study. Credibility levels are defined as follows: Level I, FDR-corrected P < 0.05 in both phases; Level II, FDR-corrected P < 0.05 in one phase and nominal P < 0.05 in the other; Level III, FDR-corrected P > 0.05 in both phases but nominal P < 0.05 in either phase. DII dietary inflammatory index, HR hazard ratio, MR-PheWAS Mendelian randomization phenome-wide association study, OR odds ratio.

Discussion

In this study, we comprehensively investigated the effects of DII on a wide range of clinical traits. Cohort study and MR-PheWAS analysis revealed compelling evidence in support of positive associations between DII score and risk of seven health outcomes. Subsequently, the two-sample MR analysis provided further confirmation for the effects of the DII score on the increased risk of back pain, abdominal hernia and cholelithiasis.

A noteworthy discovery from the current study was the positive association of DII with cholelithiasis and abdominal hernia. Existing studies on this association were limited and showed conflicting findings23,24,25. An increased DII score was linked to a higher risk of cholelithiasis in a BMI-matched case-control study recruiting 150 participants with 75 cases and 75 controls24. However, this finding contradicted with findings from a large cross-sectional study with 3626 participants, which suggested an inverse association between the DII score and the risk of gallstone disease25. In contrast to prior studies, our study was the first to employ a cohort study design and MR analysis to explore the effects of DII on cholelithiasis with a larger sample size, providing more compelling evidence. Inflammation is believed to play a pivotal role in association between DII and cholelithiasis risk. The DII has been shown to be associated with a range of inflammatory biomarkers, including IL-6, IL-10, CRP, and TNF-α26. Previous observational study further demonstrated that elevated levels of IL-6 and CRP were associated with an increased risk of cholelithiasis27,28. Moreover, a two-sample MR study identified that nine circulating inflammatory proteins were associated with the risk of cholelithiasis29. Evidence from animal models and human studies showed that inflammation-related histopathological alterations in the gallbladder wall occur before gallstones develop30. IL-6, produced by biliary epithelial cells, has been shown to promote the proliferation of various non-hematopoietic cell types31. It also contributes to inflammatory cell infiltration and subsequent thickening of the gallbladder wall28. Furthermore, in vivo models have demonstrated that TNF-α impairs the absorptive and secretory functions of gallbladder epithelial cells, and such alterations in the gallbladder wall may contribute to gallstone pathogenesis32. Regarding the association between DII and risk of abdominal hernia, no observational study to our knowledge has explored this relationship. A meta-analysis study involving 11 studies suggested that the DII score would increase sarcopenia risk33, which in turn could elevate the risk of abdominal hernias34. Thus, more in vitro and in vivo studies are needed in the future to elucidate underlying biological mechanisms.

A series of cross-sectional studies have investigated the effect of a high DII score on back pain35,36,37, while exhibiting an inconsistent conclusion. In our study, a positive association between DII and back pain was established in prospective cohort analysis and MR analysis. This finding aligns with a cross-sectional study involving 7346 participants from the 6th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and a case-control study with 106 Belgian participants37,38. However, the cross-sectional studies conducted in the United States and western Iran did not support this association35,36. The heterogeneity among these findings may stem not only from differences in study design and study population but also from variations in food components included in the DII calculation. Inflammation has been recognized as a central mechanism in the pathogenesis of back pain39. A two-sample MR study examining 41 circulating inflammatory biomarkers identified macrophage migration inhibitory factor and C-C motif chemokine ligand 3 as being associated with the risk of back pain40. In addition, a systematic review reported positive associations between back pain and several inflammatory markers, including CRP, TNF-α, and IL-641. IL-6 plays a key role in mediating the acute-phase response to injury by promoting the differentiation of monocytes into macrophages and facilitating the maturation of lymphocytes. TNF-α is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that can trigger inflammatory cascades, induce nerve swelling and neuropathic pain39. Both TNF-α and IL-6 contribute to extracellular matrix degradation, chemokine production, and phenotypic alterations in disc cells, ultimately leading to intervertebral disc degeneration—a major pathological basis for low back pain42.

Several other health outcomes have been found to be associated with DII score supported by suggestive evidence. Positive associations between DII and 38 health outcomes including myocardial infarction, all-cause mortality, and cancer risk were identified in an umbrella review43. Besides, previous prospective studies also examined the association of DII with dementia44, metabolic syndrome45, Parkinson’s disease46 and other various health outcomes. However, these reported associations were not consistently supported by the highest evidence in our study. This inconsistency might be attributed to inconsistencies in health outcomes definitions across studies and a limited statistical power in MR-PheWAS analysis. Additionally, we observed discrepancies between findings from the cohort analysis and the MR-PheWAS. One possible explanation is that weak associations may have been overlooked due to limited statistical power, given the low heritability of DII and the small proportion of variance explained by the single variant rs7910002. Additional GWAS with larger sample size are warranted to identify additional genetic variants associated with DII and improve the explained variance. Another explanation is that MR estimates reflect lifelong effects of genetic variations on diseases, whereas cohort studies typically capture the effects of DII at specific time points on disease outcomes47.

Although this study investigated the health effects of DII within the phenome-wide framework and may provide valuable insights into the health effects of DII, several limitations need to be noted. Firstly, although all analyses were adjusted for established factors that may influence the association between DII and health outcomes, the possibility of residual confounding from unmeasured variables cannot be excluded. Secondly, despite using the average of five 24-h dietary intake assessments in DII computation, it was important to recognize that dietary intake measurement remains vulnerable to recall bias. Moreover, although previous studies have demonstrated good agreement between 24-hour dietary recalls and food frequency questionnaires48,49, 24-h dietary recalls may still be insufficient to capture long-term habitual dietary patterns. Thirdly, over 50% of participants lacked DII data, which may introduce selection bias and limit the accuracy of the association estimates. To assess potential bias, we compared baseline characteristics between participants with and without DII data. No substantial differences were observed between the two groups in terms of age, sex, BMI, or lifestyle factors such as drinking, smoking status, and physical activity. Fourthly, a total of 29 food components were included in the DII algorithm, while the other 16 foods (e.g., onion, eugenol, caffeine) were not available in the UKB. It was worth noting that the majority of these unavailable foods were anti-inflammatory, which might lead to an underestimation of dietary anti-inflammatory potential. However, previous studies have shown that the DII maintains a strong correlation with inflammatory biomarkers when the number of dietary parameters used in DII calculation is reduced from 45 to fewer than 3050,51,52. Finally, although an adequate F-statistic suggesting instrument strength, the limited variance in DII explained by rs7910002 raises concerns about potential weak instrument bias in the two-sample MR analysis. Besides, the use of an instrumental variable derived from the same dataset without replication in an external population raises the possibility of winner’s curse, potentially leading to overestimation of the associations in the two-sample MR analysis. Therefore, the findings of this study are warranted to be replicated by further studies with independent populations and a larger sample size.

In conclusion, our study provided a comprehensive assessment of the health effects of DII and found a stable association with increased risk of back pain, abdominal hernia and cholelithiasis. These findings suggested that promoting diets rich in anti-inflammatory foods and reducing the intake of pro-inflammatory components may serve as a practical strategy for disease prevention at the population level.

Methods

Study population and design

The UK Biobank (UKB) recruited over 500,000 participants aged 40 to 79 years between 2006 and 2010. This project has collected biological samples and a variety of phenotype information from the participants, including physical measurements, questionnaire data, genotyping data, and longitudinal follow-up diagnoses related to health outcomes. Further details related to UKB could be found in a previous study53. Ethical approval for UKB was obtained from the North West Multi-Centre Research Ethics (REC reference11:/NW/0382) and informed consent was provided by all participants. All procedures performed were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The current study design is depicted in Fig. 1. Initially, we conducted a series of phenotype cohorts to estimate the association of DII with health outcomes under the phenome-wide framework. Following the exclusion of 294,529 participants lacking essential information and those with existing diagnoses, a total of 845 sub-cohorts were established (N = 78,390 to 207,832). Meanwhile, GWAS was performed in this study to identify DII associated genetic variants, which were subsequently employed in the MR-PheWAS (N = 315,586) to evaluate the health effects of DII. Finally, the two-sample MR analysis was applied to verify the associations supported by convincing evidence from the above analyses.

Dietary inflammatory index

The consumption of over 200 foods and 30 beverages of participants from UKB was collected through 24-h dietary recall questionnaires. These questionnaires were introduced during the first assessment phase (April 2009 to September 2010) and posteriorly repeated four times from February 2011 to June 2012. For this study, the average food consumption across these five circles was utilized to assess the specific food consumption (https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/label.cgi?id=100090).

Following the 45 food parameters for DII proposed by Shivappa et al.14, we determined a total of 29 eligible food or nutrient parameters for the calculation of DII score (Supplementary Table S14). The computation of the DII score was proceeded as follows: (1) the reported food consumption of each individual was standardized by subtracting the “standard mean” and dividing by its standard deviation to obtain a Z-score; (2) the Z-score was then converted to a percentile score, which was doubled and then subtracted by “1”; (3) for each food, the specific DII score was calculated by multiplying the centered percentile value with the inflammatory effect value obtained from the published study14; (4) the specific DII score for each food was summed to derive the overall DII score. Ultimately, the range of overall DII score was −6.66 to 5.72 (Supplementary Fig. S3). Furthermore, the energy-adjusted DII (E-DII) was calculated by expressing food and nutrient intake per 1000 kcal (i.e., food or nutrient intake divided by total energy intake multiplied by 1000 kcal). The standard procedures for DII calculation were then applied to these energy-adjusted values to derive the E-DII scores.

Genotyping data, quality control and genome-wide association analysis

Detailed genotyping information and quality control have been described in a previous study53. In the GWAS, only White participants were included and the individuals with kinship were excluded. Besides, the quality control procedure was implemented to filter out redundant variants. Initially, the variants with high missing rates were excluded (rate > 0.05). Additionally, the variants with minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.01 were rejected due to insufficient power to detect SNP-phenotype associations. The threshold for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was set 1 × 10−6 and the variants located in the sex chromosome were removed. A total of 317,582 participants passed filters and quality control procedures. After excluding participants without DII information, there were 140,669 participants remained in the GWAS, covering 8,598,234 genetic variants.

For genome-wide association analysis, the association between each SNP and DII was examined using a linear regression model, with adjustments for age, sex, body mass index (BMI) and top ten principal components. The P-value < 5 × 10−8 and linkage disequilibrium (r2 < 0.1, window = 500 kb) was set as a threshold to detect independently significant variants. Furthermore, gene analysis and gene-set analysis were performed using FUMA54.

Phenotypes

The events were diagnosed from hospital inpatient records with International Classification of Disease version 10 (ICD-10). These ICD-10 codes were further mapped to PheCODE according to a previous study55, which is capable of grouping more than >90% of ICD-10 code into phenotypes in the UKB. In the mapping process, this PheCODE system also considers gender, for instance, by identifying cancer of prostate (PheCODE, 185) only in males or malignant neoplasm of uterus (PheCODE, 182) only in females. Additionally, to mitigate the risk of contamination by cases in the control cohort, this PheCODE system implemented criteria, developed based on clinical knowledge and consultation of physician specialists, to exclude the individuals exhibiting symptoms commonly associated with the specific disease55. Furthermore, as a poor number of cases would reduce the statistical power for finding the association of DII with health outcomes, only phenotypes with more than 200 cases were included in subsequent analysis.

Statistical analysis

Participants were followed up from the date of recruitment until the date of outcome diagnosis, death, loss to follow-up, or the end of the study (May 10, 2022). Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to estimate the effects of DII (as a continuous variable) on health outcomes by calculating the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). According to the previous studies49,56,57, this model adjusted for age, sex (female or male), ethnicity (White, Asian, Black or other), BMI, educational level (high, middle or other), Townsend deprivation index (TDI), smoking status (never, previous or current), drinking status (never, previous or current) and physical activity (yes or no). We further categorized participants into anti-inflammatory (DII score \(< -1\)), neutral (\(\ge -1\) to \(\le 1\)), and pro-inflammatory (\(> 1\)) groups to confirm the association52. A series of sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the robustness of our findings. First, we examined the association between E-DII and health outcomes, accounting for potential disparities in energy intake across individuals. Second, we excluded the participants diagnosed with certain health outcome within the first two-year in the follow-up and subsequently repeated the association analysis to mitigate the potential bias arising from existing cases. Third, the investigation into the effects of DII on disease risk was restricted to White participants.

The independently significant single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were selected from our GWAS to produce the weighted genetic risk score (GRS). The weighted GRS was applied to evaluate the genetic susceptibility of DII according to the formula: GRS =\(\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i=1}^{n}S{{NP}}_{i}\times {\beta }_{i}\), where SNPi is defined as 0, 1, and 2 depending on the risk allele and βi represents the effect estimate of each SNP58. After calculating the GRS, we conducted MR-PheWAS to explore the associations between genetically predicted DII score and clinical outcomes in White participants. All regression model was adjusted for sex, age, and top ten genetic principal components.

The credibility of these associations was categorized as convincing evidence (Level I), suggestive evidence (Level II), and weak evidence (Level III). For a specific association, if it reached a significant level after false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment in both phases, its credibility was convincing. If an association reached statistical significance after FDR adjustment in one phase and had nominal significance (nominal P < 0.05) in the other, it was considered suggestive. Associations with nominal significance (nominal P < 0.05) in either phase but not significant after FDR adjustment in both were classified as weak.

Two-sample MR analysis

For associations that reached a convincing level in the cohort study and MR-PheWAS, we performed two-sample MR analysis to replicate the findings. The significant SNPs detected in the previous GWAS were utilized as instrumental variables (IVs) in this analysis. The proportion of variance in DII explained (R²) was estimated following \({R}^{2}=2\times MAF\times (1-MAF)\times {\beta }^{2}\), where MAF denotes the minor allele frequency and β represents the effect size of the SNP on the DII59. The F-statistic was calculated to assess the strength of the instrument, using the formula: \({F=R}^{2}\times (n-k-1)/(1-\,{R}^{2})\), where n is the sample size and k is the number of instrumental variables used60. An F-statistic greater than 10 was considered a strong instrument61.

Summary-level data for candidate outcomes was obtained from FinnGen cohort (version 10). The FinnGen study is a nationwide research initiative that integrates genetic data from Finnish biobank participants with comprehensive digital health information derived from national health registries. The project aims to generate genomic data linked to detailed longitudinal health records for approximately 500,000 individuals. Clinical endpoints are defined using diagnosis codes from the Finnish version of the ICD-10 and harmonized with earlier versions (ICD-8 and ICD-9)62. For each outcome of interest, we extracted the effect allele, beta coefficient, standard error, and P value corresponding to the IVs. Subsequently, SNP harmonization was performed using the harmonise_data() function in the “TwoSampleMR” R package to ensure alignment of effect alleles between the DII and outcome summary data. Wald ratio method was used to estimate the associations when only one IV was available, otherwise the inverse variance weighted method was applied.

The analyses in this study were carried out using R version 4.2 and PLINK version 1.9. MR-PheWAS were performed employing R package “PheWAS”, and two-sample MR was conducted using “TwoSampleMR”. To address the type one error due to multiple testing, we applied the FDR method to adjust the P-value. PFDR < 0.05 was considered as statistical significance.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the UK Biobank repository, https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk.

Code availability

No custom code or mathematical algorithm was developed for this study. Details regarding the specific codes used can be found in the references cited.

References

Collaborators, G. B. D. D. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 393, 1958–1972 (2019).

Meier, T. et al. Cardiovascular mortality attributable to dietary risk factors in 51 countries in the WHO European Region from 1990 to 2016: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 34, 37–55 (2019).

Jayanama, K. et al. Relationship between diet quality scores and the risk of frailty and mortality in adults across a wide age spectrum. BMC Med. 19, 64 (2021).

Key, T. J. et al. Diet, nutrition, and cancer risk: what do we know and what is the way forward?. BMJ 368, m511 (2020).

Li, J. et al. The Mediterranean diet, plasma metabolome, and cardiovascular disease risk. Eur. Heart J. 41, 2645–2656 (2020).

Mittelman, S. D. The role of diet in cancer prevention and chemotherapy efficacy. Annu Rev. Nutr. 40, 273–297 (2020).

Berding, K. et al. Diet and the microbiota-gut-brain axis: sowing the seeds of good mental health. Adv. Nutr. 12, 1239–1285 (2021).

O’Keefe, S. J. Diet, microorganisms and their metabolites, and colon cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 13, 691–706 (2016).

Tosti, V., Bertozzi, B. & Fontana, L. Health benefits of the mediterranean diet: metabolic and molecular mechanisms. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med Sci. 73, 318–326 (2018).

Schwingshackl, L., Morze, J. & Hoffmann, G. Mediterranean diet and health status: active ingredients and pharmacological mechanisms. Br. J. Pharmacol. 177, 1241–1257 (2020).

Soltani, S., Chitsazi, M. J. & Salehi-Abargouei, A. The effect of dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) on serum inflammatory markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clin. Nutr. 37, 542–550 (2018).

Clemente-Suarez, V. J., Beltran-Velasco, A. I., Redondo-Florez, L., Martin-Rodriguez, A. & Tornero-Aguilera, J. F. Global impacts of western diet and its effects on metabolism and health: a narrative review. Nutrients. 15, 2749 (2023).

Lopez-Garcia, E. et al. Major dietary patterns are related to plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 80, 1029–1035 (2004).

Shivappa, N., Steck, S. E., Hurley, T. G., Hussey, J. R. & Hebert, J. R. Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public Health Nutr. 17, 1689–1696 (2014).

Visser, E., de Jong, K., van Zutphen, T., Kerstjens, H. A. M. & Ten Brinke, A. Dietary inflammatory index and clinical outcome measures in adults with moderate-to-severe asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 11, 3680–3689.e3687 (2023).

Fowler, M. E. & Akinyemiju, T. F. Meta-analysis of the association between dietary inflammatory index (DII) and cancer outcomes. Int J. Cancer 141, 2215–2227 (2017).

Garcia-Arellano, A. et al. Dietary inflammatory index and all-cause mortality in large cohorts: the SUN and PREDIMED studies. Clin. Nutr. 38, 1221–1231 (2019).

Shivappa, N. et al. Dietary inflammatory index and cardiovascular risk and mortality—a meta-analysis. Nutrients. 10, 200 (2018).

Merino, J. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of macronutrient intake of 91,114 European ancestry participants from the cohorts for heart and aging research in genomic epidemiology consortium. Mol. Psychiatry 24, 1920–1932 (2019).

Niarchou, M. et al. Genome-wide association study of dietary intake in the UK biobank study and its associations with schizophrenia and other traits. Transl. Psychiatry 10, 51 (2020).

Bastarache, L., Denny, J. C. & Roden, D. M. Phenome-wide association studies. JAMA 327, 75–76 (2022).

Mondal, T., Rasmussen, M., Pandey, G. K., Isaksson, A. & Kanduri, C. Characterization of the RNA content of chromatin. Genome Res. 20, 899–907 (2010).

Cheng, J. et al. Association of pro-inflammatory diet with increased risk of gallstone disease: a cross-sectional study of NHANES January 2017–March 2020. Front Nutr. 11, 1344699 (2024).

Ghorbani, M., Hekmatdoost, A., Darabi, Z., Sadeghi, A. & Yari, Z. Dietary inflammatory index and risk of gallstone disease in Iranian women: a case-control study. BMC Gastroenterol. 23, 311 (2023).

Sadri, Z., Harouni, J., Vahid, F., Khosravani, Z. & Najafi, F. Association between the Dietary Inflammatory Index with gallstone disease: finding from Dena PERSIAN cohort. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 9, e000944 (2022).

Phillips, C. M. et al. Dietary inflammatory index and non-communicable disease risk: a narrative review. Nutrients. 11, 1873 (2019).

Liu, T. et al. Relationship between high-sensitivity C reactive protein and the risk of gallstone disease: results from the Kailuan cohort study. BMJ Open. 10, e035880 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Association of circulating inflammation proteins and gallstone disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 33, 1920–1924 (2018).

Wang, Z. Q., Zhang, J. Y., Tang, X. & Zhou, J. B. Hypoglycemic drugs, circulating inflammatory proteins, and gallbladder diseases: A mediation mendelian randomization study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 217, 111882 (2024).

Maurer, K. J., Carey, M. C. & Fox, J. G. Roles of infection, inflammation, and the immune system in cholesterol gallstone formation. Gastroenterology 136, 425–440 (2009).

van Erpecum, K. J. et al. Gallbladder histopathology during murine gallstone formation: relation to motility and concentrating function. J. Lipid Res. 47, 32–41 (2006).

Rege, R. V. Inflammatory cytokines alter human gallbladder epithelial cell absorption/secretion. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 4, 185–192 (2000).

Diao, H. et al. Association between dietary inflammatory index and sarcopenia: a meta-analysis. Nutrients. 15, 219 (2023).

Barten, T. R. M. et al. Abdominal wall hernia is a frequent complication of polycystic liver disease and associated with hepatomegaly. Liver Int. 42, 871–878 (2022).

Khamoushi, F. et al. Association between dietary inflammatory index and musculoskeletal disorders in adults. Sci. Rep. 13, 20302 (2023).

Shi, Y., Zhang, X. & Feng, Y. Association between the dietary inflammatory index and pain in US adults from NHANES. Nutr. Neurosci. 27, 460–469 (2024).

Shin, D. et al. Pro-inflammatory diet associated with low back pain in adults aged 50 and older. Appl. Nurs. Res. 66, 151589 (2022).

Elma, O. et al. Proinflammatory dietary intake relates to pain sensitivity in chronic nonspecific low back pain: a case-control study. J. Pain. 25, 350–361 (2024).

Khan, A. N. et al. Inflammatory biomarkers of low back pain and disc degeneration: a review. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 1410, 68–84 (2017).

Tian, H., Cheng, J., Zhao, X. & Xia, Z. Exploring causal correlations between blood inflammatory cytokines and low back pain: a Mendelian randomization. Anesthesiol. Perioper. Sci. 2, 25 (2024).

Pinto, E. M., Neves, J. R., Laranjeira, M. & Reis, J. The importance of inflammatory biomarkers in non-specific acute and chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Eur. Spine J. 32, 3230–3244 (2023).

Risbud, M. V. & Shapiro, I. M. Role of cytokines in intervertebral disc degeneration: pain and disc content. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 10, 44–56 (2014).

Marx, W. et al. The Dietary inflammatory index and human health: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. Adv. Nutr. 12, 1681–1690 (2021).

Charisis, S. et al. Diet inflammatory index and dementia incidence: a population-based study. Neurology 97, e2381–e2391 (2021).

Canto-Osorio, F., Denova-Gutierrez, E., Sanchez-Romero, L. M., Salmeron, J. & Barrientos-Gutierrez, T. Dietary Inflammatory Index and metabolic syndrome in Mexican adult population. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 112, 373–380 (2020).

Balomenos, V. et al. Dietary Inflammatory Index score and prodromal Parkinson’s disease incidence: the HELIAD study. J. Nutr. Biochem. 105, 108994 (2022).

Liu, D. et al. Vitamin D and multiple health outcomes: an umbrella review of observational studies, randomized controlled trials, and mendelian randomization studies. Adv. Nutr. 13, 1044–1062 (2022).

Cui, Q. et al. Validity of the food frequency questionnaire for adults in nutritional epidemiological studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 63, 1670–1688 (2023).

Zheng, Y. et al. Associations of dietary inflammation index and composite dietary antioxidant index with preserved ratio impaired spirometry in US adults and the mediating roles of triglyceride-glucose index: NHANES 2007-2012. Redox Biol. 76, 103334 (2024).

Shivappa, N. et al. A population-based dietary inflammatory index predicts levels of C-reactive protein in the Seasonal Variation of Blood Cholesterol Study (SEASONS). Public Health Nutr. 17, 1825–1833 (2014).

Shivappa, N. et al. Associations between dietary inflammatory index and inflammatory markers in the Asklepios Study. Br. J. Nutr. 113, 665–671 (2015).

Petermann-Rocha, F. et al. Associations between an inflammatory diet index and severe non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective study of 171,544 UK Biobank participants. BMC Med. 21, 123 (2023).

Bycroft, C. et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209 (2018).

Watanabe, K., Taskesen, E., van Bochoven, A. & Posthuma, D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 8, 1826 (2017).

Wu, P. et al. Mapping ICD-10 and ICD-10-CM codes to phecodes: workflow development and initial evaluation. JMIR Med. Inform. 7, e14325 (2019).

Shi, Y. et al. Association of pro-inflammatory diet with increased risk of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s dementia: a prospective study of 166,377 UK Biobank participants. BMC Med. 21, 266 (2023).

Fu, Y. et al. Dietary inflammatory index and brain disorders: a Large Prospective Cohort study. Transl. Psychiatry 15, 99 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. Healthy lifestyle counteracts the risk effect of genetic factors on incident gout: a large population-based longitudinal study. BMC Med. 20, 138 (2022).

Park, J. H. et al. Estimation of effect size distribution from genome-wide association studies and implications for future discoveries. Nat. Genet. 42, 570–575 (2010).

Palmer, T. M. et al. Using multiple genetic variants as instrumental variables for modifiable risk factors. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 21, 223–242 (2012).

Long, Y., Tang, L., Zhou, Y., Zhao, S. & Zhu, H. Causal relationship between gut microbiota and cancers: a two-sample Mendelian randomisation study. BMC Med. 21, 66 (2023).

Kurki, M. I. et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature 613, 508–518 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted under UK Biobank application number 71,610. Sincere thanks to the individuals for their participations and to researchers for their management. This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China [82204843, 82103936], Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China [LQN25H260002, LMS25H260003], Zhejiang Province Medical and Health Technology Plan Project [2024KY1192, 2025KY091], Zhejiang Province Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Plan Project [2023ZR084, 2024ZF060], the Research Project of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University [2022RCZXZK04], Youth Talent Support Program of Zhejiang Provincial Science and Technology Association [2024-HT-334], and Natural Science Youth Exploration Program of Zhejiang Chinese Medicine University [2023JKZKTS12].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Designed research: Ding Ye and Yingying Mao. Conducted research: Weiwei Chen, Ke Liu, Xinzhe Jing, Yu Qian, Bin Liu, and Ying Chen. Provided essential reagents: Ding Ye and Yingying Mao. Analyzed data or performed statistical analysis: Weiwei Chen, Xinzhe Jing, and Yu Qian. Wrote paper: Weiwei Chen and Xinzhe Jing. Had primary responsibility for final content: Weiwei Chen, Ke Liu, Xinzhe Jing, Ding Ye, and Yingying Mao. Revised the manuscript: Xinzhe Jing, Jiayu Li, Xiaohui Sun, Ding Ye, and Yingying Mao. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for UKB was obtained from the North West Multi-Centre Research Ethics (REC reference: 11/NW/0382) and informed consent was provided by all participants. All procedures performed were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, W., Liu, K., Jing, X. et al. The associations between diet-induced inflammation and health outcomes: a population-based phenome-wide association study. npj Sci Food 9, 223 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00583-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00583-9