Abstract

Osteoporosis is a frequent complication in β-thalassemia patients with iron overload, primarily driven by iron-induced oxidative damage and subsequent bone loss. Strategies that promote iron elimination and mitigate oxidative stress may help slow the progression of osteoporosis. Green tea extract (GTE, Camellia sinensis), enriched in epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), has both antioxidant and iron-chelating activities. This study assessed the effects of GTE on bone health in β-thalassemia knockout mice subjected to 4 weeks of iron dextran injections, followed by 2 months of daily oral treatment with deionized water, deferiprone (50 mg/kg), GTE (50 mg EGCG/kg), the combination of deferiprone and GTE, EGCG (50 mg/kg), or vitamin D3 (0.5 μg/kg ). GTE treatment reduced systemic iron burden, malondialdehyde, alkaline phosphatase, and parathyroid hormone, while improving femoral microarchitecture, bone mineral density, plasma calcium, and bone morphogenetic protein expression. These findings suggest GTE protects against iron-induced bone loss through combined chelation and antioxidation, supporting its potential as a therapeutic strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Secondary iron overload is caused by excessive iron accumulation due to repeated blood transfusions, which are often necessary for maintaining hemoglobin levels in some clinical conditions, including β-thalassemia or sickle cell anemia. Initially, the excess iron is stored in various vital organs such as the liver, heart, bone, and pancreas, leading to mild symptoms. Meanwhile, prolonged iron overload can lead to serious complications, including liver damage, diabetes, heart problems, bone loss, osteopenia, osteoporosis, and hormonal imbalances.

Osteoporosis constitutes a major complication in patients with β-thalassemia1. The clinical manifestations are bone loss, bone micro-structure degeneration, bone fragility, and fracture2. The factors affecting osteoporosis in thalassemia include bone marrow expansion due to ineffective erythropoiesis, which can result in reduced trabecular bone tissue and cortical thinning. Additionally, secondary iron overload and endocrine dysfunction lead to increased bone turnover3. A recent study showed that the accumulation of free radicals and reactive oxygen species in the bone marrow of severe thalassemia patients with chronic iron overload, consequently leads to bone loss4. Tsay and colleagues5 also confirmed that iron overload-induced bone loss is associated with increasing bone resorption and oxidative stress. Therefore, strategies for mitigating bone loss have focused on preventing iron-induced oxidative stress and reducing iron overload. Iron chelators are applied to reduce iron overload, consequently relieving further bone complications. Moreover, vitamin D3, as we all know, can enhance intestinal absorption of calcium, which is an essential element for bone mineralization6. The vitamin D supplementation is associated with improving bone loss in the β-thalassemia population7. However, both commercial iron chelators and vitamin D3 have still shown side effects after prolonged treatment and overdosing, iron chelators have been associated with adverse events such as gastrointestinal disturbances, auditory and visual neurotoxicity, hematologic complications, as well as renal and metabolic disorders8. Likewise, excessive intake of vitamin D3 may lead to hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria, with clinical manifestations such as weakness, constipation, bone pain, and even cardiac arrhythmias9.

Green tea (Camellia sinensis) is a member of the Theaceae family10, and has been shown to have various pharmacological properties11. Green tea is rich in polyphenols, including catechins epicatechin gallate (ECG), epigallocatechin (EGC), epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG)12, and epicatechin (EC). Especially, EGCG is a major compound in green tea which exhibits a variety of activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetes, anti-obesity, and anti-tumor13. Our previous study demonstrated that green tea extract (GTE) could ameliorate iron overload and the oxidative damage in the pancreas and liver of β-thalassemia mice14. In addition, green tea catechin was reported to affect the improvement of bone metabolic disorder in chronic cadmium-poisoned rats15. Moreover, EGCG can protect against bone loss induced by the inflammatory16 and enhance osteogenic differentiation while suppressing osteoclast formation17,18,19. Although iron overload was an important factor for aggravating osteoporosis in β-thalassemia20, there is limited research on whether GTE can mitigate bone loss in β-thalassemia with iron overload. We hypothesized that GTE could potentially improve bone loss in thalassemia due to its bioactive properties. Therefore, we aim to examine the effect of GTE on iron-chelating activity, reactive oxygen species (ROS)-scavenging capacity, and improvement of bone formation and bone microarchitecture in iron-overloaded β-thalassemia mice. GTE might be a novel supplement for osteoporosis therapy and prevention in β-thalassemia.

Results

EGCG content in GTE

Camellia sinensis contains a high concentration of catechins, with EGCG being particularly abundant among these compounds21. Figure 1b displays the HPLC-DAD (High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detection) profile showing EGCG content in our GTE at a retention time of 7.873 min. The additional peaks were observed at 1.983, 5.003, 8.695, and 15.663 min, which likely correspond to other polyphenolic catechins (EGC, C, EC, and ECG), as reported previously by our group22. The concentration of EGCG in the GTE sample was determined by comparing it with various concentrations of standard EGCG (0-1 mg/mL). Based on calculations, the 1 mg of GTE sample contained 0.1126 mg of EGCG. Subsequently, GTE was orally administered to iron-overloaded BKO mice throughout the study period at a dosage equivalent to 50 mg EGCG/kg body weight (BW), either through monotherapy or combination therapy with DFP.

Experimental design (a) and HPLC/DAD profile of EGCG in GTE (b). HPLC-DAD High-performance liquid chromatography with diode array, EGCG; Epigallocatechin 3-gallate, GTE; Green tea extract, WT; wild-type mice, BKO; β-globin knockout mice, DI; Iron loaded BKO treated by deionized water, DFP; Iron loaded BKO treated by deferiprone, EGCG; Iron loaded BKO treated by epigallocatechin 3-gallate, GTE; Iron loaded BKO treated by green tea extract, VD3; Iron loaded BKO treated by vitamin D3.

Iron overload in β-thalassemic mice

To confirm the establishment of iron overload, serum iron (SI) and total iron binding capacity (TIBC) were measured in tail vein blood from non-iron-loading BKO and iron-loading BKO mice before treatment, as depicted in Fig. 2a. The results indicated that Serum iron (35.3307 mg/dL) and TIBC (35.9853 mg/dL) in iron-loading mice were significantly higher than those in non-iron-loading BKO mice (1.0053 mg/dL for Serum iron and 4.9148 mg/dL for TIBC). The plasma transferrin saturation (TS) of the iron-overloaded mice was close to 100%, while TS of the non-iron-loading BKO mice was around 20% (Fig. 2b). These results implied an iron overloaded status in the iron-loading BKO mice compared to the non-iron-loading BKO mice.

Body and tissue weight progression

As shown in Fig. 3a, the BW of the WT and BKO groups, which were not subjected to iron-dextran loading, did not differ significantly throughout the treatment period. In contrast, the iron overload groups showed a significant decrease in BW during the iron-dextran loading period, followed by a slight increase during the treatment phase. However, the BW values of the iron overload mice remained lower than those of the WT and BKO groups.

Body weight (a) and organ weight index values of the liver (b), spleen (c), right tibia (d), and right femur (e) of WT, BKO (non-iron-loading), and iron loaded BKO mice treated with DI, DFP, EGCG, GTE, GTE + DFP, and VD3. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6). Accordingly, *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001 when compared to WT or BKO. WT; wild-type mice, BKO; β-globin knockout mice, DI; Iron loaded BKO treated by deionized water, DFP; Iron loaded BKO treated by deferiprone, EGCG; Iron loaded BKO treated by epigallocatechin 3-gallate, GTE; Iron loaded BKO treated by green tea extract, VD3; Iron loaded BKO treated by vitamin D3. Data analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test.

The weight of the liver and spleen, obtained from iron dextran-induced BKO mice, was measured and calculated as an organ weight index (WI), presented as the ratio of tissue wet weight to body weight (BW). As shown in Fig. 3b, c, the WI of the liver and spleen in iron overload mice was significantly higher than in WT and BKO groups, particularly in the liver (p < 0.0001 vs. BKO). Among the iron overload groups, monotherapy with DFP, EGCG, and GTE tended to decrease the WI of the liver and spleen, whereas VD3 did not have an influence compared to the iron-overloaded DI group. Combination treatment (GTE + DFP) showed a decrease in WI but was not significantly different compared to monotherapy.

Regarding the WI of the right tibia and femur (Fig. 3d, e), the WI of the iron overload mice was lower than that of the WT and BKO groups. Among the iron-overloaded groups, all monotherapy and combination treatments tended to increase the WI values of the right tibia and femur compared to iron-overloaded DI (DI) group. However, the observed results showed no statistical significance.

Assessment of iron parameters

The SI and TIBC of the mice are shown in Fig. 4. The data indicated that SI and TIBC were similar in the WT and BKO groups, while these values increased in iron-overloaded DI mice (0.11 and 0.15 mg/dL for WT and BKO, respectively, vs. 3.516 mg/dL for DI, Fig. 4a). The TIBC values of the iron-overloaded DI group were significantly higher, about 10 times more than the WT and BKO groups (Fig. 4b). All intervention treatment groups showed a decrease in SI and TIBC, particularly in the DFP, GTE, and GTE + DFP groups compared to the iron-overloaded DI group, despite the transferrin saturation remaining unchanged according to the completed iron overload condition (Fig. 4c). These findings suggested that the treatments were effective in reducing both SI and TIBC, indicating a positive outcome for the management of iron overload.

Levels of Serum iron (a), total iron binding capacity (TIBC) levels (b), and percentage of transferrin saturation (TS) (c), plasma MDA (d), and liver MDA (e) of WT, BKO (non-iron-loading), and iron dextran-loaded BKO mice treated with DI, DFP, EGCG, GTE, GTE + DFP, and VD3. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6). Accordingly, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001 when compared to WT or BKO; #p < 0.05 when compared with iron-overloaded DI. MDA; malondialdehyde, WT; wild-type mice, BKO; non-iron-loading β-globin knockout mice, DI; Iron loaded BKO treated by deionized water, DFP; Iron loaded BKO treated by deferiprone, EGCG; Iron loaded BKO treated by epigallocatechin 3-gallate, GTE; Iron loaded BKO treated by green tea extract, VD3; Iron loaded BKO treated by vitamin D3. Data analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test.

Lipid peroxidation level

As shown in Fig. 4d, e, the plasma MDA levels in the non-iron-loading (BKO) group were slightly similar to those in the WT group. However, the MDA levels in the iron-overloaded DI group were significantly higher than those in both the WT and BKO, particularly in the liver. This indicates that iron overload generated a large amount of ROS and increased lipid peroxidation. In the intervention treatments, both plasma and liver MDA levels were reduced and close to the levels in the WT and BKO groups, especially in the GTE group (p < 0.05 vs. DI) and the combination treatment of GTE + DFP (p < 0.05 vs. DI). The significant reduction in MDA generation indicates that GTE had an excellent impact on resisting ROS formation in vivo.

Hematological parameters

Table 1 shows the changes in red blood cell parameters, including red blood cell number (RBC), hemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit (Hct), and red blood cell distribution width-coefficient of variation (RDW-CV) in all mouse groups. The results indicated that RBC, Hb, and Hct levels in BKO mice were lower than those in the WT group, while RDW-CV, reflecting variability in RBC volume and size, was increased compared to WT, suggesting ineffective erythropoiesis in BKO mice. The iron-overloaded DI group exhibited higher levels of RBC, Hb, Hct, and RDW-CV compared to BKO mice, suggesting that short-term iron overload facilitated RBC production rate, while increased variability in RBC size represented high RDW-CV. However, intervention treatments likely maintained RBC, Hb, and Hct levels close to WT while reducing RDW-CV values compared to the iron-overloaded DI group. The most significant effects were observed in the GTE + DFP mice, suggesting possible improvement in erythropoiesis.

Table 2 shows the number of white blood cells (WBC) and platelets (Plt), WBC and Plt values were considerably increased in the iron-overloaded DI group compared to the WT and BKO groups, implying that iron overload might enhance inflammation in vivo. The intervention treatments with DFP, EGCG, GTE, GTE + DFP, and VD3 showed a decreasing trend of WBC and Plt levels compared to the iron-overloaded DI group, which reflects the significant reduction of inflammation in the mice after treatments. In Table 2 also presents the number and ratio (neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; NLR) of neutrophils (Neu) and lymphocytes (Lym), which are white blood cells related to immune response and inflammation. Both the BKO and iron-overloaded DI groups showed a significant decrease in Neu levels but an increase in the number of Lym compared to the WT group. The low level of NLR indicates chronic inflammation in these β-thalassemic mice. After treatment, NLR was increased, especially GTE + DFP group. Parallelly, Fig. 5 illustrates the population of Nue and Lym, which correlated with the differential numbers of both white blood cell types. However, intervention treatments tended to normalize WBC levels (especially Neu and Lym) and Plt levels, bringing them back close to WT, with the most significant effect observed in the GTE + DFP group.

Biochemical marker analysis of bone turnover

The biochemical marker analysis of bone turnover in all groups of mice is shown in Fig. 6. The data from WT and non-iron-loading thalassemic BKO mice were similar. However, iron-overloaded DI mice showed significant increases in plasma PTH, Ca²⁺, Pi, and ALP levels compared to the WT and BKO groups (Fig. 6a–e). All intervention treatments decreased the levels of PTH, Pi, and ALP. In contrast, there was a slight increase in plasma Ca²⁺ in the treatment groups compared to the iron-overloaded DI group, with the GTE + DFP group being particularly effective in this regard. The level of BMP2, a typical marker of bone synthesis23, is shown in Fig. 6f. BMP2 level tended to decrease in the iron-overloaded DI groups compared to WT, whereas DFP, EGCG, GTE, and GTE + DFP treatments, particularly EGCG treatment, showed an increase in BMP2 levels compared to the DI group. Moreover, there were no significant differences in the level of 1,25-(OH)₂D₃ between the BKO group and all iron-overloaded BKO groups with treatments (Fig. 6b).

The level of PTH (a), 1,25-(OH)2D3 (b), total Ca2+in plasma (c), Pi (d), ALP (e), and BMP2 (f). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6). Accordingly, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001 when compared to WT or BKO; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 when compared with iron-overloaded DI. WT; wild-type mice, BKO; non-iron-loading β-globin gene knockout mice, DI; Iron loaded BKO treated by deionized water, DFP; Iron loaded BKO treated by deferiprone, EGCG; Iron loaded BKO treated by epigallocatechin 3-gallate, GTE; Iron loaded BKO treated by green tea extract, VD3; Iron loaded BKO treated by vitamin D3. Data analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test.

Bone microstructure

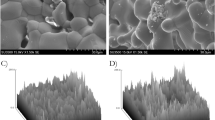

As shown in Fig. 7, BKO and iron-overloaded DI mice demonstrated significant decreases in trabecular volumetric BMD, bone volume fraction (BV/TV), and trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), while cortical BMD tended to decrease. Nonetheless, there was an increase in bone surface/bone volume (BS/BV) (p < 0.001) and trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) compared to the WT group. Treatment with GTE and GTE + DFP significantly increased trabecular BMD compared to the DI group (Fig. 7c). Furthermore, GTE, EGCG, and GTE + DFP were the most effective in improving bone microstructure by increasing BS/BV, BV/TV, and Tb.Th, while decreasing Tb.Sp (Fig. 7a). In another series of histological studies using Goldner’s trichrome staining, the mineralized trabeculae in the tibia of the GTE group were comparable to those in the positive control (EGCG) and the VD3-treated groups (Supplementary Fig. S1), suggesting that GTE was as potent as EGCG in helping to maintain the tibial trabecular structure.

Representative micro-CT images. These yellow arrows specifically pointed to the trabecular bone regions in both the coronal and sagittal views of the femur, with red-colored arrows representing the growth plate (a), BMD of cortical bone (b), BMD of trabecular bone (c), bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV) (d), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) (e), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) (f), and bone surface/bone volume (BS/BV) (g). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6). Accordingly, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 when compared to WT or BKO; #p < 0.05 when compared with iron-overloaded DI. WT; wild-type mice, BKO; non-iron-loading β-globin knockout mice, DI; Iron-loaded BKO treated with deionized water, DFP; Iron-loaded BKO treated with deferiprone, EGCG; Iron-loaded BKO treated with epigallocatechin 3-gallate, GTE; Iron-loaded BKO treated with green tea extract, VD3; Iron-loaded BKO treated with vitamin D3. Data analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test.

Discussion

Blood transfusion is the routine treatment for individuals with β-thalassemia major and β-thalassemia intermedia24, leading to iron overload and its associated complications. An excess of iron can accumulate and impair various vital organs, particularly in the liver, heart, bone, and endocrine glands, which significantly increase the development of liver cirrhosis, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and diabetes mellitus, respectively. These complications not only diminish the β-thalassemia patients’ quality of life but also substantially impact their life expectancy25.

Osteoporosis is influenced by long-term iron overload; a high amount of iron disrupts the balance of bone remodeling processes, which causes low bone density26. The supplements for bone health are encouraged to relieve bone complications. Iron chelation therapy is one strategy for mitigating the development of bone disease due to iron overload in β-thalassemia. Iron-induced ROS generation has an impact on the bone remodeling system and bone resorption according to high oxidative stress. DFP, a commercial iron chelator, is frequently applied to treat thalassemia patients with iron overload27, which helps to diminish the iron-induced complications in the patients. However, it carries a variety of side effects, including nausea, arthralgia, and gastrointestinal discomfort28. Therefore, the alternative therapeutic agent is a critical option for improving severe complications of β-thalassemia patients with iron overload.

Camellia sinensis is an evergreen shrub in the flowering plant family Theaceae, which produces green tea, a popular beverage in Asia. It has demonstrated several medicinal benefits, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. EGCG, EGC, ECG, and EC are the main catechins found in green tea leaves29. Xin W. and colleagues found that green tea (Camellia sinensis) could increase bone mass and inhibit bone loss in ovariectomized rats30. Our prior research indicated that green tea (Camellia sinensis) extract exhibited the retardation of oxidative tissue damage and iron overload in BKO mice14. Nonetheless, the specific impact of Camellia sinensis on bone loss in the iron-overloaded β-thalassemia had not been thoroughly investigated. Regarding its antioxidant properties and iron-chelating actions, this study demonstrated the effectiveness of GTE on the amelioration of iron-induced bone loss in β-thalassemia mice.

Herein, we measured levels of SI, TIBC, and TS to evaluate the iron overload in β-thalassemia mice, which had been ip injected with iron dextran solution using the method established by Rusch and colleagues31. Our findings confirmed that iron dextran administration markedly elevated SI and TIBC in the BKO mice, leading to oversaturation of TS, and the presentation of non-transferrin-bound iron (NTBI) in plasma. Notably, treatment with GTE—both as a monotherapy and combination therapy with DFP—significantly reduced SI and TIBC levels, which demonstrate the effect of GTE on iron chelation. The iron chelation property of GTE was previously reported according to the iron binding ratio of active compounds in the catechin family (EGC: iron(III); 3:2, EGCG: iron(III); 2:1, ECG: iron(III); 2:1, EC: iron(III); 3:1)32. Moreover, our results were aligned with previous studies indicating GTE’s effectiveness in alleviating ineffective erythropoiesis and reducing iron overload in β-thalassemia mice14. To minimize variability due to sex-related hormonal influences, such as estrogen’s protective effects on bone metabolism and potential modulation of iron homeostasis33,34, only male mice were used in this study. Future studies including female mice are warranted to explore potential sex-specific responses to GTE treatment.

According to animal experiments, body weight serves as a critical indicator for the health status of mice. During the iron induction phase, BKO mice exhibited progressive weight loss. However, after treatment (excluding the DI group), the weight began to recover, suggesting that the treatment positively reversed overall health status. Additionally, organomegaly can be a strong predictor of an underlying pathological condition35. The hepatosplenomegaly is associated with a high prevalence in β-thalassemia, especially transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia (TDT), resulting from long-term iron deposition and extramedullary hematopoiesis. However, BKO mice are hemizygous C57BL/6, which aligns with mild hepatosplenomegaly in non-transfusion dependent thalassemia (NTDT) patients due to non-severe iron overload and mild extramedullary erythropoiesis. In our research, the iron-loaded mice exhibited enlargement of the liver and spleen, which is associated with iron accumulation and systemic inflammation25. Interestingly, the weight of the enlarged liver and spleen was reduced after our therapies, indicating an improvement of the iron-induced pathological state in the iron overload condition. Moreover, bone weight can directly reflect the bone health status in BKO mice. Growing evidence suggests that the increased bone resorption and decreased bone formation are involved in pathological bone weight loss in iron overload conditions36. Accordingly, our data revealed that bone weights (right femur and right tibia) of iron-overloaded mice were reduced compared to normal and non-iron loading BKO mice. This result highlighted the adverse effects of excess iron on bone integrity; conversely, the iron loading of BKO mice with GTE monotherapy and combination therapy is conducive to bone weight recovery.

According to iron accumulation, ROS can cause oxidative stress throughout many organs. The lipid peroxidation occurs and finally yields the lipid peroxidation products. Malondialdehyde (MDA) is one of the products that represents the high ROS and oxidative damage37. MDA levels can normally be used to respond to the amount of lipid oxidation in vitro and in vivo, so we evaluated MDA levels in both tissue and plasma. MDA concentrations significantly increased, particularly in the liver, which is the primary site of iron storage, implying that iron overload increased lipid peroxidation in the body during the iron overload condition. Subsequently, all treatments reduced MDA levels, especially those treated by GTE and the combination of GTE and DFP. These results were in the same trend as the existing work, suggesting that GTE can mitigate lipid peroxidation levels and ROS generation38,39,40.

GTE is a natural product with low side effects at an appropriate dose41. The clinical research found GTE could reduce blood pressure, inflammatory biomarkers, and oxidative stress in hypertensive patients42. Meanwhile, GTE supplementation attenuates the blood glucose and insulin response in overweight men43. A complete blood count (CBC) analysis further elucidated the hematological effects of GTE in our research. Because of ineffective erythropoiesis in thalassemic mice, the non-iron loading BKO group has lower numbers of erythrocytes, Hb, and Hct than normal mice. In the iron overload condition, the erythrocyte, Hb, and Hct values were increased, probably caused by the 1-month iron injection affecting the hemoglobin synthesis and erythropoiesis. However, long-term iron overload may cause a decrease in red blood cell indices due to iron overload and ineffective erythropoiesis. RDW-CV evaluates the RBC volume variation range. Ahmed S Said and colleagues have reported that an increase in RDW-CV reflects a greater variability in RBC size, ineffective erythropoiesis, and premature release of reticulocytes44. Herein, we have revealed that RDW-CV values in the BKO mice were significantly higher than those in the WT mice. The iron-overloaded BKO mice showed high RDW-CV, indicating that the excess iron increased abnormal erythrocyte production. After the intervention, all these hematological parameters of GTE and the combination treatment were improved. The amount of Hb, Hct, and erythrocytes rose, respectively. The RDW-CV value was dropped, suggesting green tea can effectively improve erythropoiesis.

Furthermore, WBC and Plt are essential in the immune system that support the body against inflammation and other diseases45. Iron overload in BKO mice increased the number of WBC and Plt, substantially demonstrating that iron induced inflammation in the body. In addition, either GTE or DFP monotherapy, along with combination therapy, can against inflammation in the case of β-thalassemia mice. Neutrophil (Neu) combats inflammation as part of the innate immune response. It is the first action of white blood cells at the inflammation scene46. For Lymphocyte (Lym), it is closely related to the immunity and defense of the body. The number of Lym is negatively related to the degree of inflammation. Likewise, NLR has proven its prognostic value in cardiovascular diseases, inflammatory diseases, and several types of cancers. Referring to the normal NLR values, the adult normal range is from 0.78 - 3.53. When NLR alterations fall outside the normal range, the risk of inflammation is considered47. Our study found that BKO and iron-loaded BKO have NLR lower than the range; however, the exact normal range of mice has not been reported. The GTE, DFP, and the combination treatment exhibited an increase in NLR values, which may reflect the improvement of inflammation, and revealed a powerful anti-inflammatory effect of treatments.

Due to iron-induced osteoporosis in β-thalassemia patients, bone markers present the bone metabolism and status. The changes in bone turnover markers occur earlier than the changes in bone density during the osteoporosis process48. Under normal circumstances, calcium and phosphorus concentrations in plasma are generally stable. They are controlled by several hormones; parathyroid hormone (PTH) is the most crucial hormone. At low calcium conditions, PTH stimulates bone resorption, resulting in the release of calcium and phosphorus from bone to the bloodstream. PTH also increases the calcium reabsorption and phosphate excretion, while conversely decreasing the calcium excretion in the kidneys. Additionally, PTH is involved in vitamin D metabolism and the bone remodeling system due to the mineralization process40. In our study, the iron-overloaded DI group exhibited significantly elevated plasma PTH levels compared to wild-type (WT) and non-iron-loaded BKO groups. Previous studies 49 have shown that elevated PTH levels enhance osteoclast-mediated bone resorption, thereby contributing to bone loss, and the effect is most likely mediated by synergistic alleviation of iron-induced oxidative stress and parathyroid gland dysfunction. Treatment with GTE alone or in combination with DFP and administered as EGCG, resulted in a substantial reduction in PTH levels, approaching values observed in WT and DI controls. Monotherapies with DFP also resulted in a reduction in PTH, although to a lesser extent than GTE or the GTE + DFP combination. In contrast, the VD₃ group produced only a modest effect. The superior efficacy of GTE, particularly in combination with DFP, may be attributed to its dual iron-chelating and antioxidant properties, which alleviate oxidative injury to the parathyroid gland and thereby attenuate PTH-mediated bone resorption. These findings effectively counteract iron-induced elevation of parathormone, a key contributor to osteoporosis in β-thalassemia50.

Plasma calcium (Ca²⁺) and phosphate (Pi) levels, tightly regulated by PTH and vitamin D3 levels, are essential for bone mineralization, with bone serving as a primary reservoir51. In the iron-overloaded DI group, elevated Ca²⁺ and Pi levels compared to WT and BKO groups align with findings by Yanqiu S and colleagues52, indicating that iron overload induces elevated calcium and phosphate levels, disturbing mineral metabolism. Treatment with GTE, DFP, and particularly their combination, resulted in a marked reduction in circulating PTH levels. A significant decline in serum phosphate levels provides evidence of enhanced phosphate incorporation into the bone matrix, which may contribute to the attenuation of osteoclast-mediated bone resorption53. Concurrently, all treatments maintained serum calcium levels, supporting bone remodeling and mineralization through their antioxidant and iron chelation properties54,55.

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) serves as a key biomarker for bone turnover and inflammation, with elevated levels commonly observed in conditions of systemic inflammation56. Additionally, the increase is also an indicator of bone-related disorders, including rickets, osteomalacia, and osteoporosis57. In the iron-overloaded DI group, significantly higher ALP levels compared to WT and BKO groups indicate iron-induced inflammation and accelerated bone turnover. Treatment with GTE, DFP, and their combination therapy effectively reduced ALP levels, reflecting their anti-inflammatory and bone-protective effects. Furthermore, EGCG had the most pronounced efficacy, and VD3 treatment similarly showed a decrease in ALP. The results indicate that the GTE attenuates iron-induced inflammation and reduces ALP levels associated with bone turnover. This result of ALP is consistent with the findings of Xin Wu et al.30, which demonstrated that GTE alleviates postmenopausal osteoporosis in ovariectomized rats.

Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 (BMP2) is a critical regulator of bone formation, promoting osteoblast differentiation and activity58. The BKO and DI groups displayed decreased BMP2 levels compared to the WT group, suggesting compromised bone formation due to the inhibitory effects of iron overload on osteoblasts. EGCG treatment significantly increased BMP2 levels, followed closely by GTE, DFP, and GTE + DFP, which restored BMP2 to normal WT levels. The pronounced upregulation of BMP2 by EGCG aligns with previous findings, supporting that EGCG facilitates osteoblastic differentiation via activation of the BMP-Smad signaling pathway59. While VD3 had a comparatively weak effect, likely due to its primary role in calcium metabolism and its limited antioxidant capacity60. These intergroup differences highlight the capacity of GTE and its major constituent EGCG to promote osteoblast activity, potentially through antioxidant mechanisms that preserve BMP2 synthesis. This is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that catechins enhance osteogenic differentiation under oxidative stress conditions61.

Bone Microstructure Parameters and bone microstructure, assessed via micro-CT, provides quantitative insights into bone quality and osteoporosis severity62. The DI group showed significant reductions in trabecular bone mineral density (BMD), bone volume fraction (BV/TV), and trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) and increased the value of trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) and compared to WT and BKO, that result in an impaired bone microstructure with thinning trabeculae, an increased cortical porosity, bone fragility, and increased fracture risk63. GTE treatment alone or in combination with DFP treatments significantly improved trabecular BMD, Tb. Th, and notable increase cortical BMD, BV/TV along with a reduction in Tb.Sp that observed the microstructures are closer to WT levels. Concurrently, DFP and EGCG monotherapies showed moderate improvements in BMD and BV/TV, BS/BV, but clear effects on Tb.Sp. VD3 had minimal impact, likely due to bone destruction being predominantly caused by oxidative stress rather than disruptions in calcium cycling60. These intergroup comparisons underscore the efficacy of GTE in mitigating iron-induced bone loss, as evidenced by the most substantial restoration of bone microarchitecture. The observed improvements in BMD and BV/TV indicate increased bone mass, while elevated Tb. Th and decreased Tb.Sp suggests enhanced trabecular connectivity, which may contribute to a reduced risk of fracture64.

Intergroup comparisons revealed that both GTE monotherapy and its combination with DFP consistently performed better than other treatments in improving biochemical markers and bone microarchitecture. The GTE couple with DFP showed the greatest reductions in serum iron, MDA, PTH, Pi, and ALP levels. These changes suggest a cooperative effect between the antioxidant capacity of GTE and the iron-binding function of DFP. GTE alone was more effective than either DFP or EGCG in enhancing bone microstructure, likely due to its complex polyphenol composition that enhances antioxidant effects65. The strong induction of BMP2 by EGCG suggests a specific ability to stimulate osteoblast differentiation59, while the moderate impact observed with DFP is consistent with its primary function in regulating systemic iron levels28. The limited efficacy of vitamin D3 may be related to its primary involvement in calcium metabolism rather than direct protection against oxidative damage caused by iron overload60. These findings collectively emphasize the comprehensive role of GTE in both reducing oxidative stress and promoting bone formation in conditions of iron excess.

Although the present in vivo findings in β-thalassemia (BKO) mice support the therapeutic potential of GTE in ameliorating iron overload–induced bone loss, certain limitations should be acknowledged. In vitro systems, while useful for mechanistic insights, lack physiological complexity, including factors such as bioavailability, metabolic transformation, and systemic interactions. Furthermore, the BKO mouse model does not fully reproduce the chronic and progressive nature of iron accumulation observed in human β-thalassemia, nor does it account for the potential long-term effects and safety profile of GTE administration in clinical settings66,67. Therefore, well-designed clinical trials are necessary to determine the optimal dosage, safety, and efficacy of GTE in β-thalassemia patients with iron-induced bone complications.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

Iron dextran (ID) (100 mg iron, 200 mg dextran/mL) was purchased from TP DRUG Laboratories Co., Ltd. (Bangkok, Thailand). Deferiprone (DFP) was purchased from GPO (Thailand). EGCG was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Limited Company (St. Louis, MO, USA). Cholecalciferol (vitamin D3, VD3) was purchased from Blackmores Limited Company (Bangkok, Thailand). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for the measurement of mouse parathyroid hormone (PTH), 1,25-(OH)2D3, and bone morphogenic protein 2 (BMP2) were purchased from Abbexa Limited Company (Milton, Cambridge, UK).

Green tea extraction

Freshly picked tea leaves (Camellia sinensis) were harvested from Doi Angkhang tea fields, Fang District, Chiang Mai, Thailand. The voucher specimen number 0023404 was provided by the Herbarium, Faculty of Pharmacy at Chiang Mai University, Thailand. The leaves were immediately dried and inactivated polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity using the microwave oven (800 Watts, 3 min, 120 °C). The dried leaves were agitated and extracted in 80 °C deionized water (DI) (2 g/20 mL) for 10 min, then filtered through white gauze and centrifuged at 4 °C to remove the precipitate. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected and freeze-dried to produce green tea extract (GTE) powder. The approach established by Koonyosying and colleagues14.

Analysis of EGCG content in GTE

Reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography/diode array detection HPLC/DAD (Model 1290 Infinity II) was used to quantify EGCG in GTE under the following conditions: a mobile-phase solvent of 0.05% H2SO4: acetonitrile: ethyl acetate (86:12:2 by volume), a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min, and wavelength detection at 280 nm. The column was a ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 type, 150 mm × 3.0 mm, 5-μm pore size, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA. Eluents were distinguished by their unique retention durations, and the concentrations were computed by comparing them to EGCG standard curves22.

Animal care

Male wild-type (WT) and hemizygous β-globin knockout C57BL/6 thalassemia (BKO) mice (2–3 months old; body weight of 25–30 g) were graciously provided by Professor Dr. Suthat Fucharoen, M.D., and Associate Professor Dr. M.L. Saovaros Svasti, Ph.D. from Thalassemia Research Center, Institute of Molecular Biosciences, Mahidol University (Salaya Campus), Nakhon Pathom, Thailand. The study protocol has been approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand (Protocol Number 22/2565). The mice were housed in a conventional clean room with standard conditions (23 ± 1 °C, 40–70% humidity, 12-h day/12-h night cycle) and were allowed free access ad libitum to a normal diet and clean water14. To prevent bias, investigators were blinded to group assignments during data collection and analysis. This addition enhances the transparency of our experimental design.

The estimated sample size is calculated using G*Power software version 3.1.9.7. The comparison between 8 groups will be performed. Therefore, “F test: ANOVA repeated measures, within-between interaction” mode is used. The expected effect size of the extract is 0.40 (large). The power is 95% with α = 0.05. The number of measurements is 2 (1baseline, and 1final measurement). Thus, the total sample size obtained from G*Power is 48 (i.e., n = 6 per group)

Iron loading and treatment

The mice were randomly separated into eight groups (n = 6 each): group 1 for WT mice, group 2 for non-iron-loading BKO mice, and groups 3-8 for iron-loaded BKO mice with different treatments. Groups 1 and 2 were intraperitoneally (I.P.) injected with normal saline solution (NSS) for 4 weeks, while groups 3-8 were I.P. injected with iron dextran (10 mg/day, 5 days a week) for 4 weeks (Fig. 1a). After that, all mice were allowed to equilibrate for a further 4 weeks. Groups 1 and 2 were then treated with DI for 8 weeks. Whereas, iron-loaded BKO mice were divided into 6 groups and administered by needle gavage with DI, DFP (50 mg/kg/day), EGCG (50 mg/kg/day), GTE (50 mg EGCG equivalent/kg/day), GTE + DFP (50 mg EGCG equivalent/kg/day along with 50 mg DFP /kg/day), and VD3 (0.5 μg/kg/day), respectively, for 8 weeks. The doses of DFP, GTE, and EGCG were chosen appropriately based on our previous study14. DFP, a well-known orally active iron chelator68, was utilized as a positive control. Importantly, the establishment of the iron overload mice needs to be confirmed in groups 3–8 compared to group 2 before starting of 8 weeks treatment.

During the experiment, the body weight (BW) of the mice was recorded weekly. At the end of the study, the mice were humanely euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of a Thiopental sodium solution (0.2 ml per 100 g of body weight). The laparotomy was performed, and blood was collected from the left ventricle of the heart. The blood was transferred into sodium-heparin anticoagulant-coated tubes for the measurement of hematological parameters, iron markers, biochemical markers of bone turnover, and plasma malondialdehyde (MDA). Liver, spleen, tibiae, and femurs were collected, weighed, and dissected. The liver was only prepared for liver MDA measurement. The bone mineral density (BMD) and bone micro-architecture of the right femur were detected and visualized using micro-computed tomography (micro-CT)69.

Hematological parameters

Blood cell indexes were determined by Auto Hematology Analyzer, for animal blood testing, at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Biochemical marker analysis

Levels of total calcium (Ca2+), inorganic phosphate (Pi), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in plasma were measured by corresponding commercial kits under the guidance of the manufacturers’ instructions. The levels of PTH, 1,25-(OH)2D3, and BMP2in plasma were measured by using ELISA kits according to the manufacturers’ protocols.

Liver and plasma MDA measurement

Liver tissue was dehydrated, weighed, and homogenized in phosphate buffer. The liver homogenate was mixed with 200 μL of deproteinized reagent containing 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and 50 mg/L (w/v) butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT). The mixture was then heated at 90 °C for 30 min and centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and subjected to the MDA assay as described below.

The plasma or the supernatant was mixed with 400 μL of chromogenic solution containing 0.44 M H3PO4 and 0.6% (w/v) thiobarbituric acid (TBA). This mixture was incubated at 90 °C for 30 min, resulting in a pink product that could be detected at 532 nm using a spectrophotometer. A standard curve was created using different concentrations of 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane (TMP)70.

Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT)

The right femur from each mouse was collected and stored in normal saline-soaked gauze in a microtube at –20 °C. The midshaft and distal part of the right femur were scanned by an ultra-high resolution micro-CT system (VECTor6/CT, MILabs, The Netherlands) and reconstructed at a voxel size of 10 μm3. The region of interest (ROI) of the trabecular bone compartment was 0.5 mm (160 slices), starting 0.8 mm proximal to the end of the growth plate. The corresponding parameters of selective trabecular bone section (160 slices/section)—i.e., volumetric bone mineral density (BMD), bone surface (BS) to bone volume (BV) ratio (BS/BV), BV to tissue volume (TV) ratio (BV/TV; bone volume fraction), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), and trabecular separation (Tb.Sp)—were analyzed using Imalytics Preclinical 3.0 software (Gremse-IT GmbH, Aachen, Germany)69.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance was evaluated using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA). The results were shown in the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was performed to contrast the statistical disparities among the groups. A Tukey’s multiple comparisons test analysis of variance was performed to contrast the statistical disparities among the groups. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Dede, A. D. et al. Thalassemia-associated osteoporosis: a systematic review on treatment and brief overview of the disease. Osteoporos. Int. 27, 3409–3425 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Effect of Morinda officinalis capsule on osteoporosis in ovariectomized rats. Chin. J. Nat. Med 12, 204–212 (2014).

Bhardwaj, A. et al. Treatment for osteoporosis in people with ß-thalassaemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, Cd010429 (2016).

Grassi, F. et al. Oxidative stress causes bone loss in estrogen-deficient mice through enhanced bone marrow dendritic cell activation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 104, 15087–15092 (2007).

Tsay, J. et al. Bone loss caused by iron overload in a murine model: importance of oxidative stress. Blood 116, 2582–2589 (2010).

Christakos, S. et al. Vitamin D and the intestine: review and update. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 196, 105501 (2020).

Manolopoulos, P. P. et al. Vitamin D and bone health status in beta thalassemia patients—systematic review. Osteoporos. Int. 32, 1031–1040 (2021).

Entezari, S., et al. Iron chelators in treatment of iron overload. J. Toxicol. 2022, 4911205 (2022).

Aberger, S. et al. Targeting calcitriol metabolism in acute vitamin d toxicity—a comprehensive review and clinical insight. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 10003 (2024).

Shivashankara, A. R. et al. in Polyphenols in Human Health and Disease, Ch. 55 (eds Watson, R. R. Preedy, V. R. & Zibadi, S.) 715-721 (Academic Press, 2014).

Zhao, T. et al. Green Tea (Camellia sinensis): a review of its phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology. Molecules 27 (2022).

Koonyosying, P. et al. Decrement in cellular iron and reactive oxygen species, and improvement of insulin secretion in a pancreatic cell line using green tea extract. Pancreas 48, 636–643 (2019).

Min, K. J. & Kwon, T. K. Anticancer effects and molecular mechanisms of epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Integr. Med. Res. 3, 16–24 (2014).

Koonyosying, P. et al. Green tea extract modulates oxidative tissue injury in beta-thalassemic mice by chelation of redox iron and inhibition of lipid peroxidation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 108, 1694–1702 (2018).

Choi, J. H. et al. Action of green tea catechin on bone metabolic disorder in chronic cadmium-poisoned rats. Life Sci. 73, 1479–1489 (2003).

Tominari, T. et al. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory bone resorption, and protects against alveolar bone loss in mice. FEBS Open Bio 5, 522–527 (2015).

Lee, J.-H. et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits osteoclastogenesis by down-regulating c-fos expression and suppressing the nuclear factor-κb signal. Mol. Pharmacol. 77, 17–25 (2010).

Zhang, J. et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate enhances the osteoblastogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 13, 1311–1321 (2019).

Lin, S. Y. et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) enhances osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Molecules 23 (2018).

Rossi, F. et al. Iron overload causes osteoporosis in thalassemia major patients through interaction with transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) channels. Haematologica 99, 1876–1884 (2014).

Moore, R. J., Jackson, K. G. & Minihane, A. M. Green tea (Camellia sinensis) catechins and vascular function. Br. J. Nutr. 102, 1790–1802 (2009).

Settakorn, K. et al. Effects of green tea extract treatment on erythropoiesis and iron parameters in iron-overloaded β-thalassemic mice. Front. Physiol. 13, 1053060 (2022).

Ogasawara, T. et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 2-induced osteoblast differentiation requires Smad-mediated down-regulation of Cdk6. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 6560–6568 (2004).

Langhi, D. Jr. et al. Guidelines on Beta-thalassemia major—regular blood transfusion therapy: Associação Brasileira de Hematologia, Hemoterapia e Terapia Celular: project guidelines: Associação Médica Brasileira - 2016. Rev. Bras. Hematol. Hemoter. 38, 341–345 (2016).

Koonyosying, P., Fucharoen, S. & Srichairatanakool, S. Nutraceutical Benefits of Green Tea in Beta-Thalassemia with Iron Overload. In Beta Thalassemia (IntechOpen, 2020). Available from: https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.92970

von Brackel, F. N. & Oheim, R. Iron and bones: effects of iron overload, deficiency and anemia treatments on bone. JBMR 8, ziae064 (2024).

Saliba, A., Harb, A. & Taher, A. Iron chelation therapy in transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients: Current strategies and future directions. J. Blood Med. 6, 197–209 (2015).

Fisher, S. A. et al. Oral deferiprone for iron chelation in people with thalassaemia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8, Cd004839 (2018).

Tasneem, S. et al. Molecular pharmacology of inflammation: medicinal plants as anti-inflammatory agents. Pharmacol. Res. 139, 126–140 (2019).

Wu, X. et al. Green tea (Camellia sinensis) aqueous extract alleviates postmenopausal osteoporosis in ovariectomized rats and prevents RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis in vitro. Food Nutr Res. 62 (2018).

Rusch, J. A. et al. Diagnosing iron deficiency: controversies and novel metrics. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 37, 451–467 (2023).

Guo, M. et al. Iron-binding properties of plant phenolics and Cranberry’s bio-effects. Dalton Trans.43, 4951–4961 (2007).

Noirrit-Esclassan, E. et al. Critical role of estrogens on bone homeostasis in both male and female: from physiology to medical implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 1568 (2021).

Streicher, C. et al. Estrogen regulates bone turnover by targeting RANKL expression in bone lining cells. Sci. Rep. 7, 6460 (2017).

Vaibhav, V. et al. A preliminary study of organ weight after histological exclusion of abnormality during autopsy in the adult population of Uttarakhand, India. Cureus 14, e27044 (2022).

Jeney, V. Clinical impact and cellular mechanisms of iron overload-associated bone loss. Front. Pharm. 8, 77 (2017).

Tsikas, D. Assessment of lipid peroxidation by measuring malondialdehyde (MDA) and relatives in biological samples: analytical and biological challenges. Anal. Biochem. 524 (2017).

Forney, G. B., Morré, D. J. & Morré, D. M. Oxidative stress reduced by a green tea concentrate and Capsicum combination: synergistic effects. J. Diet. Suppl. 10, 318–324 (2013).

Suzuki, K. et al. Effect of green tea extract on reactive oxygen species produced by neutrophils from cancer patients. Anticancer Res. 32, 2369–2375 (2012).

Ma, Y. et al. Green tea polyphenols alleviate hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in bovine mammary epithelial cells by activating ERK1/2-NFE2L2-HMOX1 Pathways. Front. Vet. Sci. 8, 804241 (2021).

Chacko, S. M. et al. Beneficial effects of green tea: a literature review. Chin. Med. 5, 13 (2010).

Bogdanski, P. et al. Green tea extract reduces blood pressure, inflammatory biomarkers, and oxidative stress and improves parameters associated with insulin resistance in obese, hypertensive patients. Nutr. Res. 32, 421–427 (2012).

Martin, B. et al. Short-term green tea extract supplementation attenuates the postprandial blood glucose and insulin response following exercise in overweight men. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41, 1057–1063 (2016).

Said, A. S. et al. RBC distribution width: biomarker for red cell dysfunction and critical illness outcome?. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 18, 134–142 (2017).

Kundrapu, S. & Noguez, J. in Advances in Clinical Chemistry Ch. 6 (ed Makowski, G. S.) 197–225 (Elsevier, 2018).

Jenne, C. N., Liao, S. & Singh, B. Neutrophils: multitasking first responders of immunity and tissue homeostasis. Cell Tissue Res. 371, 395–397 (2018).

Forget, P. et al. What is the normal value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio?. BMC Res Notes 10, 12 (2017).

Miller, P. D. Bone density and markers of bone turnover in predicting fracture risk and how changes in these measures predict fracture risk reduction. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 3, 103–110 (2005).

Ben-awadh, A. N. et al. Parathyroid hormone receptor signaling induces bone resorption in the adult skeleton by directly regulating the RANKL gene in osteocytes. Endocrinology 155, 2797–2809 (2014).

Dimitriadou, M. et al. Elevated serum parathormone levels are associated with myocardial iron overload in patients with beta-thalassaemia major. Eur. J. Haematol. 84, 64–71 (2010).

Levine, B. S., Rodríguez, M. & Felsenfeld, A. J. Serum calcium and bone: effect of PTH, phosphate, vitamin D and uremia. Nefrología Engl. Ed. 34, 658–669 (2014)..

Song, Y. et al. Iron overload impairs renal function and is associated with vascular calcification in rat aorta. Biometals 35, 1325–1339 (2022).

Bonjour, J. P. Calcium and phosphate: a duet of ions playing for bone health. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 30, 438s–448ss (2011).

Shen, C. L. et al. Green tea and bone metabolism. Nutr. Res 29, 437–456 (2009).

Shen, C.-L., Chyu, M.-C. & Wang, J.-S. Tea and bone health: steps forward in translational nutrition12345. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98, 1694S–1699S (2013).

Cheng, X. & Zhao, C. The correlation between serum levels of alkaline phosphatase and bone mineral density in adults aged 20 to 59 years. Medicine (Baltimore) 102, e34755 (2023).

Kuo, T.-R. & Chen, C.-H. Bone biomarker for the clinical assessment of osteoporosis: recent developments and future perspectives. Biomark. Res. 5, 18 (2017).

Halloran, D., Durbano, H. W. & Nohe, A. Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 in Development and Bone Homeostasis. J. Dev. Biol. 8 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate promotes osteo-/odontogenic differentiation of stem cells from the apical papilla through activating the BMP-SMAD signaling pathway. Molecules 26 (2021).

Fleet, J. C. Vitamin D-mediated regulation of intestinal calcium absorption. Nutrients 14 (2022).

German, I. J. S. et al. Exploring the impact of catechins on bone metabolism: a comprehensive review of current research and future directions. Metabolites 14 (2024).

Brandi, M. L. Microarchitecture, the key to bone quality. Rheumatology (Oxford) 48, iv3–iv8 (2009).

Dalle Carbonare, L. & Giannini, S. Bone microarchitecture as an important determinant of bone strength. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 27, 99–105 (2004).

Chen, H. & K.Y. Kubo, Bone three-dimensional microstructural features of the common osteoporotic fracture sites. World J. Orthop. 5, 486–495 (2014).

Yan, Z. et al. Antioxidant mechanism of tea polyphenols and its impact on health benefits. Anim. Nutr. 6, 115–123 (2020).

Dostal, A. M. et al. The safety of green tea extract supplementation in postmenopausal women at risk for breast cancer: results of the Minnesota Green Tea Trial. Food Chem. Toxicol. 83, 26–35 (2015).

Hu, J. et al. The safety of green tea and green tea extract consumption in adults - Results of a systematic review. Regul. Toxicol. Pharm. 95, 412–433 (2018).

Entezari, S. et al. Iron chelators in treatment of iron overload. J. Toxicol. 2022, 4911205 (2022).

Imerb, N. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy exerts anti-osteoporotic effects in obese and lean D-galactose-induced aged rats. Faseb j. 37, e23262 (2023).

Li, J. et al. A novel synthetic compound, deferiprone-resveratrol hybrid (DFP-RVT), promotes hepatoprotective effects and ameliorates iron-induced oxidative stress in iron-overloaded β-thalassemic mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 180, 117570 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express our gratitude to Youjiang Medical University for Nationalities, People’s Republic of China, and the Office of the Permanent Secretary for Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation, Thailand (Grant No. RGNS63-070), and a Distinguished Professor Grant, National Research Council of Thailand (Grant number: N42A670732) which provided financial support. The Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, for providing laboratory facilities, and the Thalassemia Research Center, Institute of Molecular Biosciences, Mahidol University, Salaya Campus, for providing β-thalassemia mice. The ultra-high-resolution micro-computed tomography platform was supported by Mahidol University–Frontier Research Facility (MU-FRF) and MUSC–Central Animal Facility. The authors also wish to express the gratitude to Dr. Ratchaneevan Aeimlapa for valuable suggestions on bone histological studies. The bone histology platform was supported through the Research Cluster Development Fund, Mahidol University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.X., S.S., O.K., P.K.; methodology, H.X., P.K.; investigation, H.X., K.S., N.P., K.C., N.C., P.K., J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.X., O.K.; visualization, H.X., P.K.; writing—review and editing, O.K., P.K.; supervision, K.C., N.C., S.S.; project administration, P.K.; funding acquisition, P.K., H.X., S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, H., Settakorn, K., Khantamat, O. et al. Administration of green tea polyphenols mitigates iron-overload-induced bone loss in a β-thalassemia mouse model. npj Sci Food 9, 239 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00601-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00601-w