Abstract

Cherries are highly susceptible to spoilage after harvest due to physiological and biochemical changes. This poses considerable challenges to food safety. Common fungal pathogens responsible for decay include Aspergillus niger and Cladosporium cladosporioides. Citral, an efficient antifungal agent, is thought to combat these pathogens through interactions with phytase (phyA) and N-myristoyltransferase (NMT), a hypothesis explored through molecular docking simulations. Using the Independent Gradient Model based on Hirshfeld partition (IGMH) analysis, it was found that citral encapsulated within α-cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks (α-CD-MOFs) forms strong van der Waals forces and exhibits hydrogen bonding. These interactions enhance the stability of the composite material. Incorporating citral-loaded α-CD-MOFs into a matrix of sodium alginate and pullulan resulted in a novel composite film. This film exhibits significantly improved flexibility and tensile properties, which is beneficial for fruit packaging. Meanwhile, the Higuchi and Ritger–Peppas models both indicate that citral is released by diffusion from a uniform polymeric matrix. When applied to cherry preservation, the film exhibited significantly better cherry preservation at 4 °C than at 30 °C (P < 0.05). Simultaneously, the combination of low temperature with the film’s barrier properties and sustained antimicrobial release synergistically inhibited microbial growth and fruit metabolism, effectively delaying spoilage and supporting its application in both cold-chain and ambient-temperature transport.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cherries, being a representative perishable fresh fruit, pose notable food safety concerns due to their susceptibility to quality degradation caused by postharvest physiological processes and biochemical alterations1. In the course of storage and transport, they are highly vulnerable to rapid deterioration resulting from fungal contamination, elevated respiration rates, and active enzymatic reactions2,3. Such factors lead to a marked decline in both the commercial value and shelf life of the fruit. Consequently, the advancement and implementation of efficient preservation techniques are crucial for reducing postharvest losses and ensuring the freshness and quality of cherries across the entire supply chain.

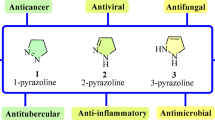

Notably, essential oils, found in plants, are valued for their various bioactivities, including strong antifungal properties, making them useful in food preservation4,5. Citral (CI) is a good example of this. However, essential oil components often exhibit high volatility and low water solubility, posing considerable challenges for their practical application in food packaging6. These characteristics limit the full utilization of their preservative effects. Therefore, it is necessary to develop innovative delivery systems to enhance the stability and efficacy of essential oil components in fruit preservation. By doing so, not only can the antifungal performance of effective components like citral be better utilized, but overall preservation effectiveness can also be improved.

To overcome these limitations, researchers have explored the use of metal-organic frameworks as carriers for active compounds7. Cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks (CD-MOFs) are characterized as porous materials that feature extensive surface areas along with the capability to modify pore dimensions8, which make them highly suitable for encapsulating volatile and hydrophobic substances to enhance their stability9. Particularly, α-CD-MOFs have smaller cavities (4.4–5.7 Å) compared to γ-CD-MOFs (7.4–9.5 Å), making them more suitable for encapsulating small-molecule compounds10. Moreover, β-CD forms a rigid, continuous hydrogen-bonded “belt” between the secondary hydroxyl groups at C2 and C3, limiting its interaction with water molecules and resulting in lower water solubility than α-CD11.

These frameworks can effectively load and controlled-release citral, thereby maintaining prolonged antifungal activity. Furthermore, CD-MOFs exhibit excellent biocompatibility and environmental safety, rendering them appropriate for food-related applications12. Nevertheless, the tendency of CD-MOFs nanoparticles to aggregate and their inherent crystallinity pose challenges for their integration into food packaging materials. However, the tendency of CD-MOFs nanoparticles to aggregate and their inherent crystallinity pose challenges for their integration into food packaging materials13. Therefore, immobilizing CD-MOFs onto suitable substrates to achieve synergistic effects remains a key challenge in current research. The feasibility of this approach has been demonstrated in previous studies14,15. Notably, applications of α-CD-MOFs in this field have been rarely reported, and this study presents a novel exploration of their potential use in active packaging systems.

Sodium alginate (SA) and pullulan (Pul), known for their excellent film-forming properties and biodegradability16,17, serve as promising substrates for CD-MOFs. Incorporating α-CD-MOFs into these biopolymer matrices not only enhances the mechanical and barrier properties of the films but also provides controlled release of citral, consequently prolonging the storage life of cherries18. This study develops a novel composite film by encapsulating citral in α-CD-MOFs to improve its stability and antifungal activity, and integrating the system into a biodegradable SA/Pul matrix for practical application. However, despite the potential of such systems, there is still limited research on their efficacy under real storage conditions. To address this gap, this study aims to: (1) develop and characterize the citral-loaded α-CD-MOFs composite film; (2) evaluate its antifungal activity in vitro; and (3) assess its effectiveness in preserving cherry quality and extending shelf life under both cold and ambient storage conditions. This work provides a promising strategy for developing sustainable active packaging to reduce postharvest losses in perishable fruits.

Results and discussion

Identification of saprophytic fungi in cherries

Research has led to the isolation of two predominant fungal pathogens (Y-1 and Y-2) from naturally decayed cherries. Morphological examinations indicated that Y-1 presented with colonies featuring radial striations, rounded edges, a rough texture, and a velvety appearance in shades of brown to dark brown (Fig. 1A). Microscopic inspection revealed spherical spores (Fig. 1A-1), which subsequently developed into dispersed hyphae upon further incubation (Fig. 1A-2). Comparative analysis with known fungal species descriptions suggested that this fungus is likely Aspergillus niger19. The Y-2 fungus manifested under natural light as olive-green, velvety, and slightly elevated colonies (Fig. 1B). Under microscopic observation, the spores appeared short and rod-like (Fig. 1B-1), progressing to develop into elongated and branched hyphae after a certain period (Fig. 1B-2)20.

To further confirm the identity of these fungi, their ITS rDNA gene sequence (Table S1) were compared with those in the GenBank database exhibiting homologies ranging from 97 to 100%. A phylogenetic tree was constructed to establish the genetic relationships among the saprophytic fungi. Consequently, the morphological and genetic analyses collectively identified Y-1 as A. niger (Fig. S1) and Y-2 as Cladosporium cladosporioides (Fig. S2).

Antifungal properties

Three terpenoid compounds were tested for their antifungal activity against the two main pathogens causing cherry spoilage within a concentration range of 12.5 to 400 mg/mL (Table S2). The results indicated that the antifungal activity of citral and camphor against A. niger increased with the elevation of their active component concentrations. However, no activity was observed for myrcene. Among these, limonene demonstrated the best antifungal activity against A. niger, achieving an inhibition zone of 39.00 ± 1.73 mm at a concentration of 400 mg/ml, which was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than the antifungal activities of the other two compounds at the same concentration. When tested against C. cladosporioides, it was found that both citral and camphor exhibited excellent antifungal activity capable of inhibiting fungal growth even at the lowest concentration of 12.5 mg/mL. In contrast, myrcene did not show any activity against this fungus even when its concentration was increased to 400 mg/mL.

According to previous studies, the mechanism by which citral inhibits A. niger involves affecting the fungal cell membrane potential and energy metabolism, as well as regulating the expression of proteins and genes associated with cell membrane synthesis21. Similarly, camphor exhibits antifungal activity against A. niger through its effects on the fungal cell membrane22. Regarding the specific mechanisms of pure citral and camphor’s action against C. cladosporioides, there have been no detailed reports to date. Here, we speculate that its antifungal mechanism may involve causing an imbalance in cellular membrane ion permeability23, which requires further investigation. In studies of myrcene’s antifungal activity against A. niger and C. cladosporioides, antifungal activity has been demonstrated using essential oil blends24,25. When pure myrcene is used as an antimicrobial agent without the synergistic effects of other components, it may not exhibit significant activity; this has also been confirmed in previous studies26. In conclusion, given the superior antifungal activity of citral against the main pathogens responsible for cherry spoilage, this substance will serve as the foundation for further experimental testing.

Molecular docking studies

Molecular docking studies were performed to provide structural-level auxiliary validation for the experimentally observed antifungal activities, by examining potential interactions between active compounds and key fungal target proteins—PhyA from A. niger and NMT from C. cladosporioides (Fig. 2).

From the information in Table S3, camphor exhibited the most favorable binding energy with PhyA (−5.51 kcal/mol), forming hydrogen bonds with GLN-168 (2.3 Å) and PHE-154 (1.9 Å). In contrast, myrcene showed a higher (less negative) binding energy of −4.18 kcal/mol and no hydrogen bond interactions with PhyA. According to general principles, lower binding energies and the presence of hydrogen bonds are often associated with stronger receptor-ligand interactions27. However, experimental antifungal assays (Table S2) revealed that citral demonstrated significantly stronger inhibitory activity against A. niger than camphor, despite camphor showing the best in silico binding performance. This inconsistency indicates that molecular docking results may not always correlate with actual bioactivity, likely due to limitations such as simplified scoring functions and unaccounted physicochemical factors. For NMT from C. cladosporioides, compounds with more hydrogen bond interactions generally showed better binding affinities, which is consistent with their experimentally determined antifungal effects28.

Therefore, the molecular docking results serve as structural support for the experimental findings. Given the limitations of static docking models—such as the lack of consideration for compound volatility, membrane permeability, and cellular accessibility—these in silico data should be regarded solely as auxiliary validation.

Microstructure of CI-α-CD-MOFs

The microstructures of α-CD, α-CD-MOFs, and CI-α-CD-MOFs were observed through scanning electron microscope (SEM) in this study. As shown in Fig. 3A, the irregular block-like structure of α-CD with a diameter ranging from 10 to 80 μm can be seen. Figure 3B illustrates the bundled crystalline morphology of α-CD-MOFs, which is similar to the structures observed under an optical microscope in previous studies29. However, the cross-sectional diameter of the α-CD-MOFs prepared in this study was ~20–40 μm, a significant reduction compared to earlier findings29. Moreover, there were numerous voids between these crystals, providing ample space for the loading of active substances. Figure 3C shows the α-CD-MOFs after the incorporation of citral, which exhibits a structure similar to that in Fig. 3B, yet with the appearance of numerous honeycomb-like micropores on the crystal surface. This structural change is likely due to the interaction with citral and may enhance the loading of active substances. Furthermore, elemental mapping analysis demonstrated a homogeneous distribution of key elements within the CI-α-CD-MOFs, with the contents of carbon (C), oxygen (O), and potassium (K) being 45.6, 46.5, and 7.9%, respectively, as illustrated in Fig. 3D, E. These results demonstrate the successful construction of porous α-CD-MOFs.

XRD analysis

The crystal structures of α-CD and α-CD-MOFs were characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD). As shown in Fig. 4(Ⅰ), α-CD exhibited characteristic diffraction peaks at 2θ = 5.22°, 11.94°, 12.16°, 13.56°, 14.34°, and 21.70°, which are consistent with previous literature reports30,31. In comparison to α-CD, the XRD pattern of α-CD-MOFs showed significant changes: original peaks (such as those at 5.22°, 9.67°, 12.16°, 14.34°, and 21.70°) disappeared and new characteristic peaks emerged at 7.72°, 12.7°, 16.77°, 19.66°, 20.77°, 21.21°, and 22.56°. These observations align with the typical XRD patterns reported for α-CD-MOFs in Jiang et al.32, indicating that α-CD has been successfully assembled into α-CD-MOFs with an ordered crystalline structure. This structural transformation is also evident in the morphological differences between α-CD and α-CD-MOFs shown in Fig. 3, where α-CD (Fig. 3A) exhibits an irregular block-like structure, while α-CD-MOFs (Fig. 3B) form bundled crystalline structures, further supporting the reconstruction of the crystal structure.

Ⅰ XRD patterns of α-CD and α-CD-MOFs. Ⅱ FT-IR spectra of citral, α-CD-MOFs and CI-α-CD-MOFs. Ⅲ The appearance of these films under natural light (1) and under the microscope with a 40 × objective lens (2); (A) SA film. (B) SA/Pul film. (C) CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul film. Ⅳ The mechanical properties of these films. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). Ⅴ The DVC and APT of these films. Ⅵ The WS (A) and WCA (B) of these films. (1): SA film. (2): SA/Pul film. (3): CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul film.

FT-IR analysis

FT-IR was performed on citral, α-CD-MOFs, and CI-α-CD-MOFs to investigate the potential interactions between citral and α-CD-MOFs. As shown in Fig. 4(Ⅱ), comparison of the FT-IR spectra of the three samples revealed notable differences in three spectral regions. The first region, located at 2970–2761.72 cm⁻¹, corresponds to the stretching vibrations of methyl (–CH₃) and methylene (–CH₂–) groups in citral33. However, these characteristic peaks were completely masked in CI-α-CD-MOFs. The second region spanned from 1674 to 1337 cm⁻¹; among them, the peak at 1674 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the C=O stretching vibration of citral34, which remained detectable in CI-α-CD-MOFs. Additionally, the bands at 1445 and 1381 cm⁻¹ are typically associated with –C=C– stretching and –CH₃ bending vibrations in citral35, but exhibited slight shifts in wavenumber in CI-α-CD-MOFs. The third region, observed between 1124 and 1192 cm⁻¹, represents a characteristic absorption band of citral that was significantly diminished in both α-CD-MOFs and CI-α-CD-MOFs.

In summary, after encapsulation of citral by α-CD-MOFs, some of the characteristic absorption peaks of citral were shielded, while new peaks related to citral appeared in the spectrum of α-CD-MOFs. This phenomenon is consistent with previous studies36,37. The observed spectral changes may be attributed to intermolecular forces that facilitate the inclusion of citral into the hydrophobic cavity of α-CD-MOFs, resulting in partial signal attenuation. To further elucidate the molecular interaction mechanism between citral and α-CD-MOFs, subsequent simulations of intermolecular forces were conducted.

Intermolecular force

To understand the adsorption mechanism of citral in α-CD-MOFs at the molecular level, Gaussian density functional theory (DFT) B3LYP/6-31G(d, p) method were performed to explore the possible binding sites of citral within α-CD-MOFs. The standard coloring of sign(λ2)ρ in IGMH isosurface maps (Fig. 5A). Based on the IGMH, the intermolecular interactions between cyclodextrin and citral were determined, and colored δginter isosurfaces with the sign(λ2)ρ relationship graph were plotted. In the IGMH isosurfaces, predominantly green ellipsoidal plates (Fig. 5B) can be observed, indicating that the stabilization of citral loaded into α-cyclodextrin is mainly through van der Waals (vdW) forces, as evidenced by the associated scatter plot (Fig. 5C). Additionally, hydrogen bonding interactions (Fig. 5D) are present, with the optimized hydrogen bond length being 2.3 Å, which is significantly shorter than the sum of the vdW radii of O and H atoms (3.05 Å)38. In summary, the inclusion of citral in cyclodextrin is primarily stabilized by the synergistic effect of vdW forces and hydrogen bonding interactions.

The appearance of these films

The prepared films are shown in Fig. 4(Ⅲ). Under natural light, the pure SA film appears as a transparent light yellow film with a smooth surface (Fig. 4(Ⅲ)-A-1), which is consistent with previous studies39. Upon further addition of Pul, the SA/Pul film remains a transparent light yellow film with a smooth surface (Fig. 4(Ⅲ)-B-1), showing no significant changes in appearance compared to the pure SA film. This is directly related to the colorless, transparent, and water-soluble properties of Pul40. Building on this, the addition of CI-α-CD-MOFs results in a film that also appears transparent and light yellow with a smooth surface (Fig. 4(Ⅲ)-C-1). This is associated with the light-colored physical properties of both citral and α-cyclodextrin41.

Based on this, the surface morphology of these films was observed under a microscope. The results indicate that the outer surfaces of the SA film and SA/Pul film are relatively smooth with few pores (Fig. 4(Ⅲ)-A-2, and (Ⅲ)-B-2). In contrast, the outer surface of the CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul film exhibits a large number of micro-pits (Fig. 4(Ⅲ)-C-2). This surface morphology, rich in microstructural features, not only increases the effective specific surface area of the film but also provides more storage sites for the loading of active substances, thereby facilitating the encapsulation and release of active components42.

Mechanical properties

The mechanical properties represent a crucial characteristic of edible packaging films, as they directly influence the durability and robustness of these films43. In this study, the mechanical property test results for the prepared films are presented in Fig. 4(Ⅳ). The results show that the thickness of the pure SA film was 0.26 ± 0.03 mm. When Pul and CI-α-CD-MOFs were sequentially added to the SA film, there was no significant difference in thickness (P > 0.05). For the fracture tensile strain (FTS), the addition of Pul to SA did not significantly increase the value of pure SA. However, when CI-α-CD-MOFs were added to the SA/Pul film, the FTS significantly increased to 146.14 ± 1.09% (P < 0.05), demonstrating excellent tensile deformation performance. This phenomenon may be attributed to the formation of a cross-linked network by the metal nodes and organic linkers in CI-α-CD-MOFs44, as well as the glycosidic ring structure of α-CD-MOFs providing a stable framework for the composite film45. This enhances the internal stability of the film, thereby leading to a significant increase in tensile strength. Consequently, the tensile fracture stress (TFS), tensile strength (TS), and tensile yield stress (TYS) of the film were all significantly increased (P < 0.05) after the addition of CI-α-CD-MOFs. Additionally, the YM of the film was significantly reduced (P < 0.05) after adding CI-α-CD-MOFs, indicating a notable decrease in the hardness of the film46. While the incorporation of α-CD-MOFs enhances the film’s FTS, it also increases the material’s tendency to deform under stress, leading to a reduction in its YM. Such observations have been documented in prior film studies47. In conclusion, the incorporation of MOFs materials into the SA/Pul film leads to improved deformation properties, rendering it more suitable as a packaging material for fruits and vegetables.

DVC and APT of these films

Figure 4(Ⅴ) presents the DVC and absorption performance testing (APT) of these films. The DVC of the membrane can be used to evaluate its loading capacity. After evaporation at 105 °C for 24 h, no significant difference in DVC content was observed between the SA and SA/Pul films (P > 0.05). This can be explained by their similar microstructures as revealed by SEM images and membrane thickness, indicating no notable structural differences. This also suggests that there is no significant difference in their APT values (P > 0.05). However, when CI-α-CD-MOFs were incorporated into the SA/Pul film, along with an additional wetting step during film preparation, the weight of citral was increased on top of the original water content in the SA/Pul film. This resulted in a significant difference in the high-temperature volatilization test (P < 0.01). Similarly, the porous structure on the surface of the membrane increased the specific surface area and provided more binding sites, thereby significantly enhancing its water adsorption capacity (P < 0.05)48.

Water resistance of these films

This study examined the WS of SA, SA/Pul, and CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul films. As illustrated in Fig. 4(Ⅵ)-A, all three films completely dissolved within 1 h, indicating their good WS These results are consistent with previous findings49. To further investigate the differences in WS among these films, the WCA was measured. Data analysis, conducted within its 95% confidence band, revealed that the slope of the trend line for the WCA of the SA film is K = –0.34659 (R2 = 0.96686), for the SA/Pul film is K = –0.28414 (R2 = 0.99275), and for the CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul film is K = –0.19460 (R2 = 0.95643) (Fig. 4(Ⅵ)-B). By comparing the absolute values of these slopes, it was determined that the CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul film exhibits the lowest dissolution rate, thus demonstrating the highest water resistance. The likely reason is that the metal ions in CD-MOFs undergo cross-linking reactions with carboxyl or other functional groups in SA/Pul, forming a more compact network structure. This tighter network enhances the structural stability of the material in water, thereby increasing the hydrophobicity of the film50. Similar findings have also been reported in previous studies51.

Thermal stability analysis

Figure 6(Ⅰ) presents the thermogravimetric (TG) and derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves of citral and the CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul film. The TG curve of citral (Fig. 6(Ⅰ)-A-1) indicates that it undergoes continuous volatilization and decomposition in a single stage over the temperature range of 37–488 °C, with a weight loss of 98.1294% occurring over 2800 s. As shown in the DTG curve (Fig. 6(Ⅰ)-A-2), the maximum weight loss rate of citral occurs at 233.5 °C, reaching a peak rate of 0.016062 mg/s. For the CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul film, its TG curve (Fig. 6(Ⅰ)-B-1) shows that the thermal degradation process mainly occurs in four stages within the temperature range of 30–470 °C. The first stage, occurring between 40 and 140 °C, involves a weight loss of 15.7374%, which is attributed to the evaporation of moisture1. The second stage, from 140 to 200 °C, exhibits a weight loss of 18.0625%, primarily due to the removal of guest solvents from the film matrix52. The total weight loss in the first two stages amounts to 33.7999%, a value close to the DVC of the film. The third stage of weight loss occurs between 200 and 250 °C, which is mainly attributed to the volatilization and decomposition of citral embedded within the α-CD-MOFs structure and attached to the surface of the film. The maximum weight loss rate reaches 0.00767982 mg/s at 231.7 °C (Fig. 6(Ⅰ)-B-2), significantly lower than the weight loss rate of pure citral (0.0159642 mg/s) at the same temperature. This indicates that the CD-MOFs and the film matrix effectively enhance the thermal stability of citral53. The fourth stage of weight loss, occurring between 250 and 340 °C, is primarily due to the decomposition of the film into smaller particles54. By 350 °C, the total weight loss of the CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul film reaches 81.6829%. In summary, the α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul film system provides a more stable microenvironment for citral, significantly delaying its volatilization and degradation.

Release kinetics

Figure 6(Ⅱ)-A shows the cumulative and daily release of citral from the α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul film. On the first day of the release test, the release of citral reached 26.07 ± 1.39%, which was the highest value over the 8-day release period. Afterward, the release rate gradually decreased and eventually stabilized. This is primarily due to the initially high concentration of citral in the film, which provided a stronger driving force for diffusion, resulting in a faster initial release rate54,55.

To further understand the release mechanism of the film, several mathematical models were employed: the Zero-order model (Fig. 6(Ⅱ)-B, R² = 0.90673), First-order model (Fig. 6(Ⅱ)-C, R² = 0.98117), Higuchi model (Fig. 6(Ⅱ)-D; R² = 0.99956), Ritger–Peppas model (Fig. 6(Ⅱ)-E, R² = 0.99958), and Weibull model (Fig. 6(Ⅱ)-F, R² = 0.97753). The goodness of fit was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R²). Among these, the Higuchi and Ritger–Peppas models exhibited the highest R² values (>0.999), indicating excellent fitting performance. The Higuchi model indicates that citral diffusion is time-dependent and involves sustained release from a homogeneous matrix56. Additionally, in the Ritger–Peppas model, the exponent n = 0.50419 falls within the range of 0.45 < n < 0.89, suggesting that the release mechanism involves both diffusion and dissolution57. However, it should be noted that the film was placed openly in the experimental container rather than immersed in a solution. Therefore, we hypothesize that during storage, the film absorbed some moisture, leading to partial dissolution of the film structure and subsequent release of citral.

In summary, the sustained release behavior of citral from the film aligns well with predictions from both the Higuchi and Ritger–Peppas models, with the dominant release mechanism being diffusion-controlled.

Evaluation of cherries quality

Fresh cherries were placed into storage containers and individually covered with one of three different film types. Preservation indicators were monitored over a 10-day storage period under two conditions: 30 °C and 4 °C, both at 50–70% relative humidity. The control group (CK) remained uncovered.

Visual assessment analysis

The study conducted a visual assessment of the cherries throughout the storage period. Low-temperature storage exhibited superior preservation efficacy compared to ambient-temperature storage, as it significantly suppressed respiratory and transpiration rates, thereby reducing water loss, slowing cellular structure degradation, and better maintaining fruit firmness and surface glossiness58.

The comparison at 30 °C in Fig. 7 reveals that the CK group exhibited initial signs of surface deterioration—such as wrinkling, pitting, and loss of glossiness—by day 4. This deterioration is attributed to accelerated water evaporation under high temperature, leading to reduced cellular turgor pressure, along with increased activity of cell wall-degrading enzymes, which promote tissue softening and structural collapse59. In contrast, the film-wrapped treatment groups (SA/Pul, PE, and CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul) showed better preservation of visual quality, as the film acts as a protective barrier on the fruit surface, effectively limiting moisture loss and gas exchange, thereby delaying dehydration and metabolic degradation60. Over time, all groups developed varying degrees of wrinkling and pitting under both 30 °C and 4 °C. However, the most severe deterioration was observed in the CK group at 30 °C, indicating that unprotected fruit is highly susceptible to elevated temperature stress.

Microbial growth on the fruit surface was also monitored. No visible microbial growth was observed in any cherry group stored at 4 °C, indicating that low temperature effectively suppresses microbial metabolism and proliferation61. In contrast, at 30 °C, visible microbial growth—manifested as localized mold spots and mucoid colonies—was detected in the CK, SA/Pul, and PE groups. This is attributed to the warm and humid environment promoting rapid proliferation of spoilage microorganisms (e.g., Aspergillus, Cladosporium), thereby accelerating fruit decay62. Notably, the CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul film, which incorporates the antimicrobial agent citral encapsulated within α-CD-MOFs for stable loading and sustained release, exhibited excellent antimicrobial performance.

Decay rate evaluation

Decay rate is a key indicator of postharvest fruit quality, closely correlated with weight loss, firmness, and reactive oxygen species levels, and thus serves as an effective parameter for evaluating the overall deterioration trend of fruit quality63. As shown in Fig. 8A, after 10 days of storage, the CK (30 °C) group exhibited a significantly higher decay rate (81.67 ± 7.64%) than all other treatments (P < 0.001), indicating that fruit spoilage progresses rapidly under conventional high-temperature storage. In contrast, fruits treated with CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul (30 °C) film showed significantly lower decay rate, with superior preservative effect compared to the PE film group (P < 0.05). This is consistent with previous findings where γ-CD-MOFs-based antimicrobial films also outperformed PE films15. The reason for this may be that the wrapping of the cherries with this film effectively blocked the infiltration of a large number of saprophytic microorganisms64 and prevented damage to the fruit integrity caused by small insects63. Additionally, the loading of healthy antimicrobial active components in the film further enhanced this barrier effect65, as verified in Table S2.

When storage temperature was optimized to 4 °C, decay rate significantly decreased across all groups, demonstrating that low temperature effectively suppresses microbial growth, respiration rate, and enzymatic activity, thereby delaying senescence61. Notably, the CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul (4 °C) film achieved a lower decay rate, highlighting the synergistic effect between the functional film and cold storage. PE (30 °C) film also showed better preservation, primarily relying on its physical barrier properties and the inherent ability of low temperature to slow microbial growth. Cold storage not only stabilizes the release and prolongs the activity of bioactive components in the film but also enhances the fruit’s disease resistance and tissue stability, enabling long-term quality preservation, extending shelf life, and maintaining superior edible quality.

Weight loss analysis

Weight loss is a key indicator for evaluating fruit quality, primarily caused by water loss due to respiration and transpiration, often leading to fruit wilting and quality deterioration66. Under storage at 30 °C, this study investigated the effect of three film packaging treatments on weight loss in cherry fruit over 10 days (Fig. 8B). The unpackaged CK (30 °C) group exhibited significantly higher water loss than all other groups (P < 0.001), reaching 27.30 ± 2.19%. Although no significant differences were observed among the remaining three treatment groups (P > 0.05), the CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul (30 °C) film group consistently maintained the lowest water loss (13.60 ± 1.32%), which may be attributed to its ability to effectively reduce decay rate and thereby minimize water loss associated with cellular damage67. Previous studies have also demonstrated that a γ-CD-MOFs film loaded with curcumin can reduce weight loss in strawberries68.

When the storage temperature was reduced to 4 °C, weight loss in all groups was significantly lower compared to the 30 °C condition. Although differences among treatments were not significant (P > 0.05), the CK (4 °C) group still showed the highest relative weight loss, primarily due to the absence of a physical barrier against moisture evaporation. Low temperature effectively suppressed respiration and transpiration rates, thereby slowing water loss and delaying overall quality deterioration58.

Titratable acidity analysis

Titratable acidity is a critical indicator for assessing the respiratory rate of fruits, as it is associated with organic acids, which serve as substrates in respiratory metabolism1. As shown in Fig. 8C, with the extension of storage time, the titratable acidity in different groups of cherries generally decreased. However, cherries packaged with specific films exhibited a significantly slower decline compared to the control group without packaging. During the growth phase of the fruit, organic acids gradually accumulate. Upon entering the maturation stage, however, the content of organic acids begins to decrease due to their involvement in respiratory processes and other metabolic activities69.

Studies have found that under storage conditions at 30 °C by the end of the storage period, although there were no significant differences among groups (P > 0.05), the titratable acidity of cherries in the CK (30 °C) group without film coverage dropped to the lowest value of 0.23 ± 0.08%, whereas cherries packaged with CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul (30 °C) film maintained a higher titratable acidity of 0.30 ± 0.05%, even surpassing those packaged with PE (30 °C) film at 0.28 ± 0.07%. This indicates that the composite film can effectively slow down the respiratory rate of cherries and improve preservation performance. Similar findings have been observed with drug-loaded MOFs composite films used on other fruits such as cherry tomatoes68,70, strawberries68, and apples71.

Under low-temperature conditions at 4 °C, the titratable acidity across all tested groups was significantly higher than their counterparts stored at 30 °C. Specifically, by the end of the storage period, the titratable acidity of cherries in the uncoated CK (4 °C) group could still be maintained at 0.37 ± 0.08%, while those packaged with CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul (4 °C) film remained at 0.43 ± 0.07%. These data further demonstrate that even at lower temperatures, this composite film can further delay the degradation of organic acids, contributing to maintaining the freshness and quality of the fruit.

MDA analysis

Malondialdehyde (MDA) content is a widely used indicator of membrane lipid peroxidation and serves as a reliable marker for assessing the degree of fruit senescence or oxidative stress72. As shown in Fig. 8D, MDA levels in all cherry groups increased progressively throughout the storage period, indicating continuous oxidative damage and gradual deterioration of cellular membranes. However, the rate of MDA accumulation was significantly influenced by both packaging treatment and storage temperature.

At 30 °C, the CK (30 °C) group exhibited the fastest increase in MDA content, reaching 6.75 ± 1.02 μmol·g⁻¹ at the end of storage, indicating severe lipid peroxidation and accelerated fruit senescence. In contrast, samples packaged with the CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul (30 °C) film showed a significantly slower accumulation of MDA (P < 0.05), with a final content of 5.11 ± 0.86 μmol·g⁻¹, which was also lower than that of the PE (30 °C) film group (5.46 ± 0.09 μmol·g⁻¹). This suggests that the composite film effectively alleviates oxidative stress, possibly due to its excellent physical barrier properties and the sustained release of bioactive components from the MOFs structure, thereby mitigating oxidative damage caused by environmental stresses73.

Under low-temperature storage at 4 °C, MDA accumulation in all groups was significantly lower than in their corresponding 30 °C counterparts (P < 0.01), confirming that low temperature effectively delays oxidative damage74. Nevertheless, differences among packaging treatments remained evident. At the end of storage, the CK (4 °C) group had an MDA content of 3.45 ± 0.35 μmol·g⁻¹, while the lowest level was observed in the CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul (4 °C) film group (3.08 ± 0.75 μmol·g⁻¹), followed by the SA/Pul (4 °C) film group (3.29 ± 0.36 μmol·g⁻¹) and the PE (4 °C) film group (3.21 ± 0.63 μmol·g⁻¹). These findings are consistent with previous studies75.

In summary, the CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul composite film effectively suppresses lipid peroxidation in cellular membranes during storage, thereby delaying fruit senescence. The preservation effect is further enhanced under refrigerated conditions, highlighting the synergistic benefits of low temperature and active packaging in maintaining cherry quality.

Methods

Materials and reagents

Sodium alginate (SA, Adamas), pullulan (Pul, ≥99%, Aladdin), α-cyclodextrin (α-CD, ≥98%, Adamas), potassium hydroxide (KOH, ≥90%, Greagent), ethanol (≥99.5%, Greagent), citral (CI, ≥95%, Adamas), glycerol (99.5%, Meryer), potato dextrose agar medium (PDA, Hopebio).

Fungal identification

The identification of saprophytic fungi followed the method described by Mou et al.76. Fungal colonies that showed abundant growth on the surface of spoiled cherries were selected for further analysis. Briefly, fungal spores were evenly spread on PDA plates and incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. A single colony was then picked and repeatedly subcultured on fresh plates to ensure purity. Microscopic observation of individual colonies’ morphology was conducted during this process. For accurate identification of the fungal genus and species, DNA sequencing of the strain was performed with the assistance of Tianke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The ITS rDNA gene sequences were compared with reference sequences in the NCBI database, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed to ultimately determine the species of the saprophytic fungus.

In vitro antifungal activity

The in vitro antifungal activity of active substances (e.g., citral) as well as various film materials was evaluated by measuring the diameter of inhibition zones, following the method described by Mou et al.77. Briefly, 0.2 mL of fungal suspension (1.5 × 10⁶ CFU/mL) was uniformly spread onto potato dextrose agar medium (PDA) plates and allowed to absorb statically. Subsequently, 50 μL of active substances at concentration gradients ranging from 12.5 to 400 mg/mL was added into pre-punched wells (6 mm in diameter) on the PDA medium. In parallel, SA film, SA/Pul film, and CI-α-CD-MOFs/SA/Pul film were each prepared into solutions at a concentration of 400 mg/mL, and 50 μL of each solution was similarly applied into separate wells using the same procedure. The plates were then incubated at 30 °C for 36 h, after which the diameters of the inhibition zones (mm) were measured and recorded. Dimethyl sulfoxide was used as the negative control, and carbendazim served as the positive control to assess the antifungal efficacy of all samples.

Molecular docking

Phytase gene (phyA) (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/3K4Q; PDB ID: 3K4Q), which can be produced by various species of Aspergillus, particularly A. niger, is capable of dephosphorylating lower-order inositol phosphates to form inositol monophosphates. This process plays a crucial role in providing the phosphate necessary for fungal development78. Furthermore, extensive experimental evidence indicates that N-myristoyltransferase (NMT) (https://www.rcsb. org/structure/1IYK; PDB ID: 1IYK) is a highly promising target for antifungal drugs79, which has been studied for its activity against C. cladosporioides. The study utilizes active ingredients, such as citral, in conjunction with these enzymes to predict and understand the binding interactions between small molecules and target proteins, employing molecular docking methods as described by Emam et al.80.

Synthesis of α-CD-MOFs

As illustrated in Fig. 9 and described by Oh et al.81, the traditional steam diffusion method is used for the preparation of α-CD-MOFs crystals. Briefly, α-CD (4.86 g) and KOH (2.24 g) were dissolved in 80 mL of deionized water at a molar ratio of 1:8, followed by thorough stirring for 6 h. The mixture was then filtered through a 0.45-micron filter membrane. After filtration, the solution was placed in a beaker containing 100 mL of ethanol and sealed for 7 days at room temperature to facilitate the growth of α-CD-MOFs crystals.

Microstructure

The sample was gold-coated to enhance its conductivity, and imaging was performed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, model SU-3800, Hitachi, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV. Furthermore, the elemental distribution of the sample was analyzed and mapped utilizing an energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrometer integrated with the SU-3800 SEM.

Crystal structure analysis

XRD analysis was carried out according to the method of Ming et al.30, using a D8 ADVANCE X-ray diffractometer (Bruker, Germany) in wide-angle scanning mode. The measurements were performed over a scan range of 5°–40° at a scan rate of 5°/min to characterize the crystal structure of the samples.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

The sample was carefully mixed with dried KBr powder in an appropriate ratio and then pressed into a transparent pellet. The obtained pellet was placed into the sample compartment of an FT-IR spectrometer (IRTracer 100, Shimadzu, Japan) and scanned in the range of 4000–500 cm⁻¹ 82.

Theoretical calculation method

The inclusion behavior of citral within α-CD-MOFs was investigated following the methodology established by Lu et al.83. Briefly, the dominant configurations of citral and its complexes with α-CD were initially constructed using Chem3D software. Subsequently, geometry optimization calculations for all conformers of citral and α-CD were performed at the 6-31G(d, p) basis set level through DFT with the B3LYP functional, implemented in Gaussian software. The molecular interactions were then determined using the Independent Gradient Model based on Hirshfeld partition (IGMH), with computational results analyzed through the Multiwfn program. Finally, visual representation of the research findings was achieved using Visual Molecular Dynamics software.

Preparation of films

The fabrication procedure for the thin film followed the methodologies outlined in previous studies84,85. The preparation process of the film is illustrated in Fig. 9. Briefly, Pul and SA were mixed in equal weight ratios to prepare a 4 g/100 mL solution, to which 3% (v/v) glycerol was added. Subsequently, 200 mg of CI-α-CD-MOFs material was uniformly dispersed into this solution. The resulting mixture was dried at 40 °C for 24 h to form the film. The film was then immersed in citral and shaken at 25 °C at 200 rpm for 10 min. Finally, the film was retrieved and air-dried for further use.

Appearance of these films

The appearance of the film was observed under natural light. Subsequently, the microstructure of the film was observed under an optical microscope with a 40× objective lens (ML-41, Mshot, Guangzhou, China).

Film thickness

Using a desktop micrometer (manufactured by Shanghai Liuleng Instrument Factory, China), the measurement process for the thickness of each film sample was repeated three times.

Mechanical properties

The film samples to be tested were prepared as rectangular strips measuring 15 mm × 70 mm. These samples were then subjected to uniaxial tensile testing using a 1 kg load capacity tensile tester (Wance Testing Machine Co., Ltd, China) at a rate of 1 mm/s. This process was used to evaluate various mechanical properties of the films, including film thickness (FT), FTS, TFS, TS, TYS, and Young’s modulus (YM).

Determination of volatile components in films (DVC)

The film was cut into pieces measuring 2 cm × 2 cm (W₀). The samples were then dried at 105 °C for 24 h and reweighed (W₁). The drying and weighing process was repeated three times. The calculation formula is as follows:

Absorption performance testing (APT)

The film from which volatile components had been removed (W₁) was placed in a controlled environment at 30 °C and 50–70% relative humidity for 24 h. Afterward, the weight of the film after absorbing environmental components was recorded (W₂). The test was repeated three times. The calculation formula is as follows:

Water solubility (WS)

The film samples were cut into strips measuring 1 cm × 2 cm, and their initial mass (m0) was recorded. The samples were then immersed in 8 mL of distilled water and intermittently stirred at room temperature for 24 h. Afterward, the undissolved films were dried to a constant weight, and the final mass (m1) was recorded. Each film sample underwent this testing procedure three times.

Evaluation of the water contact angle (WCA)

The hydrophilicity of the film surface can be assessed by measuring the contact angle86. A PGX goniometer (FIBRO System AB, Sweden) was used to analyze the changes in the water contact angle of a 5 μL distilled water droplet placed on the film surface. The measurement cycle lasted for 60 s.

Thermal stability

The thermal stability of the films was evaluated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (SDT-Q 600, TA Instruments, USA). 5 mg of each sample was heated from 30 to 550 °C at a constant heating rate of 10 °C min⁻¹ under a nitrogen atmosphere.

Release behaviors

The study referred to the method of Mou et al.35. Briefly, the film was cut into pieces of 3 × 3 cm² and placed in an environment of 30 °C and 50–70% relative humidity. Samples were collected daily and dissolved in 5 mL of ethanol. The solutions were then subjected to ultrasonic treatment for 30 min, after which the supernatant was collected and the citral content was determined by measuring UV absorbance at 287 nm using a standard curve (y = 2.0901x − 0.1173, R2 = 0.9967). The experiment was repeated three times. The cumulative release of citral was calculated using the following formula:

Herein, mi (i = 1, 2, 3, …, n) denotes the residual quantity of citral present in the film at various intervals, while m0 signifies the initial quantity of citral incorporated into the multilayer film.

The release profile of citral was fitted using four mathematical models: (4) Zero-order model, (5) First-order model, (6) Higuchi model, (7) Ritger–Peppas model, and (8) Weibull model:

where y is the percentage of citral released at time t, k is the release rate constant, and n, d are the release exponent. A is the total amount of released citral.

Preservation of cherries

Cherries of similar appearance and consistent weight were selected for the experiment. The experimental groups were designated as CK, SA/Pul film, CI-α-CD MOFs/SA/Pul film, and polyethylene (PE) film, with each group consisting of 10 cherries, and each treatment was performed in triplicate. Ten cherries were placed into a preservation container and then covered with the respective packaging film. The specific packaging configurations are illustrated in Fig. S3. Testing conditions: Samples were stored at 30 °C and 50–70% relative humidity, as well as at 4 °C and 50–70% relative humidity, for 10 days, to evaluate the effects of both ambient and refrigerated storage on the quality preservation of cherries.

Fruit visual evaluation

The surface quality of cherries was evaluated based on visual assessment of color, sunken areas, and microbial growth. Changes such as browning, dullness, softening, or shriveling were recorded. Visible microbial growth (e.g., fungal hyphae) was recorded and described accordingly.

Evaluation of decay rate on cherries

The evaluation method for decay rate referred to the approach outlined by Mou et al.77 with minor modifications. It is measured by assessing the area of decay on the fruit surface, with tests conducted every 2 days.

Weight loss

To assess the weight loss of cherries during storage, initial weights were recorded at the start of the experiment, followed by subsequent weighings every 2 days. Weight loss is presented as a percentage (%).

Titratable acidity (TA)

Accurately weigh 2.0 g of cherry pulp homogenate and transfer it into a beaker. Add 50 mL of deionized water and stir thoroughly to ensure complete dissolution. Filter the mixture and collect the filtrate for titration. Using phenolphthalein as the indicator, titrate the filtrate with 0.01 mol/L NaOH solution. Each sample is analyzed in triplicate, and the mean value is reported. Titratable acidity is calculated according to the following formula:

where V is the volume of NaOH solution consumed (mL), n is the molarity of NaOH (mol/L), 0.0670 is the malic acid conversion factor, and m is the sample mass (g)1.

Malondialdehyde (MDA)

The MDA content in cherries was quantified using the thiobarbituric acid method as described by Bai et al.72. Briefly, 1.0 g of fruit pulp was homogenized in 5.0 mL of 10% trichloroacetic acid, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. A 2.0 mL aliquot of the supernatant was combined with 2.0 mL of 0.67% thiobarbituric acid solution, incubated in a boiling water bath for 20 min, and then cooled to room temperature before centrifugation for 10 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was recorded at 450, 532, and 600 nm. MDA content was determined based on its molar absorption coefficient and expressed in μmol/g.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed via one-way analysis of variance, with values of P < 0.05 deemed to indicate statistical significance in Duncan’s multiple range test.

Data availability

The authors declare that all the data supporting the findings of this study are available in the paper.

References

Tang, B. S. et al. Preparation of pullulan-shellac edible films with improved water-resistance and UV barrier properties for Chinese cherries preservation. J. Future Foods 5, 107–118 (2025).

Yang, Y. Q. et al. Improving the storage quality and aroma quality of sweet cherry by postharvest 3-phenyllactic acid treatment. Sci. Hortic. 338, 113661 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Antifungal electrospinning nanofiber film incorporated with Zanthoxylum bungeanum essential oil for strawberry and sweet cherry preservation. Food Sci. Technol. 169, 113992 (2022).

Zhang, Y. N. & Yu, D. H. High internal phase pickering emulsions stabilized by ODSA-functionalized cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks for extrusion 3D printing application. Food Sci. Technol. 182, 114800 (2023).

Zhao, J., Wang, Y. M., Liu, Q. Y., Wang, Y. Q. & Long, C. A. Pullulan-based coatings carrying biocontrol yeast mixed with NaCl to control citrus postharvest disease decays. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 205, 106108 (2024).

Arcot, Y. et al. Edible nano-encapsulated cinnamon essential oil hybrid wax coatings for enhancing apple safety against food borne pathogens. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 8, 100667 (2024).

Ma, P. H., Zhang, J. L., Liu, P., Wang, Q., Zhang, Y., Song, K. S., Li, R. & Shen, L. Computer-assisted design for stable and porous metal-organic framework (MOF) as a carrier for curcumin delivery. Food Sci. Technol. 120, 108949 (2020).

Jiang, L. W. et al. Encapsulation of catechin into nano-cyclodextrin- metal-organic frameworks: preparation, characterization, and evaluation of storage stability and bioavailability. Food Chem. 394, 133553 (2022).

Zhan, S. Y. et al. Facile synthesis and crystalline stability of cubic nano-γ-cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks for hydrophobic polyphenols carrier. Food Biosci. 63, 105655 (2025).

Xiao, Z. B. et al. Application of cyclodextrin-based microcapsules in food flavors and fragrances. Carbohyd. Polym. 367, 123963 (2025).

Poulson, B. G. et al. Cyclodextrins: structural, chemical, and physical properties, and applications. Polysaccharides 3, 1–31 (2022).

Hamedi, A., Anceschi, A., Patrucco, A. & Hasanzadeh, M. A gamma- cyclodextrin-based metal-organic framework (gamma-CD-MOF): a review of recent advances for drug delivery application. J. Drug Target. 30, 381–393 (2022).

Qin, Z. Y. et al. Synthesis of nanosized γ-cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks as carriers of limonene for fresh-cut fruit preservation based on polycaprolactone nanofibers. Small 20 https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202400399 (2024).

Yu, W. F. et al. Sustained antimicrobial polymer film from γ-CD-MOF humidity switch for fruit and vegetable preservation. Food Chem. 479, 143856 (2025).

Liang, W. X. et al. A novel antimicrobial film AgNPs@γ-CD-MOFs/PLA: Preparation, characterization and its application for packaging of Agaricus bisporus. Food Packag. Shelf 47, 101449 (2025).

Agrawal, S., Budhwani, D., Gurjar, P., Telange, D. & Lambole, V. Pullulan based derivatives: synthesis, enhanced physicochemical properties, and applications. Drug Deliv. 29, 3328–3339 (2024).

Zhang, J. N. et al. Ammonia-responsive colorimetric film of phytochemical formulation (alizarin) grafted onto ZIF-8 carrier with poly(vinyl alcohol) and sodium alginate for beef freshness monitoring. J. Agric. Food Chem. 72, 11706–11715 (2024).

Ramezanzadeh, M., Ramezanzadeh, B. & Mahdavian, M. Graphene skeletal nanotemplate coordinated with pH-Responsive porous Double-Ligand Metal-Organic frameworks (DL-MOFs) through ligand exchange theory for High-Performance smart coatings. Chem. Eng. J. 461, 141869 (2023).

Chu, S. M., Lin, L. Y. & Tian, X. L. Analysis of Aspergillus niger isolated from ancient palm leaf manuscripts and its deterioration mechanisms. Herit. Sci. 12, 199 (2024).

Zhang, H. J. et al. Isolation, Identification and Hyperparasitism of a Novel Cladosporium cladosporioides Isolate Hyperparasitic to Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici, the Wheat Stripe Rust Pathogen. Biology 11, 892 (2022).

Wang, Y. H., Yang, Q. L., Zhao, F. Y., Li, M. & Ju, J. Synergistic antifungal mechanism of eugenol and citral against Aspergillus niger: Molecular Level. Ind. Crop. Prod. 213, 118435 (2024).

Moleyar, V. & Narasimham, P. Mode of antifungal action of essential oil components citral and camphor. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 25, 781–784 (1987).

Kamdem, B. P. et al. Pharmacological activity and mechanisms of action of terpenoids from Laurus nobilis L. Nat. Prod. J. 13, e081222211792 (2023).

Elidrissi, A. E. et al. Phytochemical analysis and evaluation of antifungal and antioxidant activities of essential oil of fruits from Juniperus oxycedrus L. obtained from Morocco. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 59, e21088 (2023).

Ladeira, A. M. et al. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activities of the essential oil of Hypericum cordatum (Vell. Conc.) N. Robson (Hypericaceae). J. Essent. Oil Res. 21, 558–560 (2009).

Bulkan, G. et al. Enhancing or inhibitory effect of fruit or vegetable bioactive compound on Aspergillus niger and A. oryzae. J. Fungi 8, 12 (2022).

Morris, C. J. & Della Corte, D. Using molecular docking and molecular dynamics to investigate protein-ligand interactions. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 35, 2130002 (2021).

Kumar, D. T. & Doss, C. G. P. Investigating the inhibitory effect of wortmannin in the hotspot mutation at codon 1047 of PIK3CA kinase domain: a molecular docking and molecular dynamics approach. Adv. Protein Chem. Str. 102, 267–297 (2016).

Li, H. et al. Metal-organic framework based on α-Cyclodextrin gives high ethylene gas adsorption capacity and storage stability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 34095–34104 (2020).

Ming, L. S. et al. Encapsulation of essential oil in cyclodextrin: an exploration of rational design, molecular interactions, and activity assessment. Ind. Crop. Prod. 226, 120611 (2025).

Lezrag, H. A. et al. Improving camphor solubility and stability through α-cyclodextrin encapsulation: characterization, cytotoxicity investigation, and bull sperm preservation evaluation. J. Incl. Phenom. Macro. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10847-025-01308-x (2024).

Jiang, L. W. et al. Encapsulation of catechin into nano-cyclodextrin-metal-organic frameworks: preparation, characterization, and evaluation of storage stability and bioavailability. Food Chem. 394, 133553 (2022).

Tian, H. X., Lu, Z. Y., Li, D. F. & Hu, J. Preparation and characterization of citral-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles. Food Chem. 248, 78–85 (2018).

Ma, H. H. et al. Citral-loaded chitosan/carboxymethyl cellulose copolymer hydrogel microspheres with improved antimicrobial effects for plant protection. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 164, 986–993 (2020).

Mou, L. Y. et al. Grafted modified chitosan/pullulan film loaded with essential oil/β-CD-MOFs for freshness preservation of peach. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 306, 141491 (2025).

Yuan, C., Wang, Y. L., Liu, Y. W. & Cui, B. Physicochemical characterization and antibacterial activity assessment of lavender essential oil encapsulated in hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin. Ind. Crop. Prod. 130, 104–110 (2019).

Rakmai, J., Cheirsilp, B., Mejuto, J. C., Simal-Gándara, J. & Torrado-Agrasar, A. Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of encapsulated guava leaf oil in hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin. Ind. Crop. Prod. 111, 219–225 (2018).

Su, Q. M., Su, W. T., Xing, S. H. & Tan, M. Q. Enhanced stability of anthocyanins by cyclodextrin-metal organic frameworks: encapsulation mechanism and application as protecting agent for grape preservation. Carbohyd. Polym. 326, 121645 (2024).

Lan, W. T., He, L. & Liu, Y. W. Preparation and properties of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose/sodium alginate/chitosan composite film. Coatings 8, 291 (2018).

Gniewosz, M. & Synowiec, A. Antibacterial activity of pullulan films containing thymol. Flavour Frag. J. 26, 389–395 (2011).

Hu, X. T. et al. Research progress on natural citral resources. Mod. Agr. Sci. Technol. 17, 185–190 (2023).

Min, T. T. et al. Highly efficient anchoring of γ-cyclodextrin-MOFs on chitosan/cellulose film by in situ growth to enhance encapsulation and controlled release of carvacrol. Food Hydrocolloid 150, 109633 (2024).

Liu, Q. et al. Genipin-crosslinked amphiphilic chitosan films for the preservation of strawberry. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 213, 804–813 (2022).

Zhang, Y. H. et al. -Cyclodextrin encapsulated thymol for citrus preservation and its possible mechanism against Penicillium digitatum. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 194, 105501 (2023).

Wang, F. et al. Redox-responsive blend hydrogel films based on carboxymethyl cellulose/chitosan microspheres as dual delivery carrier. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 134, 413–421 (2019).

Bundschuh, S. et al. Mechanical properties of metal-organic frameworks: an indentation study on epitaxial thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 101910 (2012).

Concórdio-Reis, P. et al. Characterisation of films based on exopolysaccharides from alteromonas strains isolated from French Polynesia marine environments. Polymers 14, 4442 (2022).

Zhai, G. H. et al. Adsorption of sulfadiazine from water by Pedicularis kansuensis derived biochar: preparation and properties studies. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 143, 581–591 (2025).

Özcan, B. D., Zimmermann, M. L., Ren, M. Z. & Bols, M. New methods of modification of α-cyclodextrin. Org. Biomol. Chem. 22, 7092–7102 (2024).

Zhang, R. K., Fu, Y., Qin, W. P., Qiu, S. S., & Chang, J. Preparation of a novel bio-based aerogel with excellent hydrophobic flame-retardancy and high thermal insulation performance. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 141 https://doi.org/10.1002/app.55416 (2024).

Jiang, L. W. et al. Development of zein edible films containing different catechin/cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks: physicochemical characterization, antioxidant stability and release behavior. Food Sci. Technol. 173, 114306 (2023).

Xu, Y. et al. Antimicrobial and controlled release properties of nanocomposite film containing thymol and carvacrol loaded UiO-66-NH2 for active food packaging. Food Chem. 404, 134427 (2022).

Shahri, M. M. E., Noshirvani, N. & Kadivar, M. High performance carbohydrate-based films incorporated with thyme essential oils/zinc-based metal-organic frameworks for cheese preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 306, 141756 (2025).

Mou, L. Y. et al. Strawberry preservation using multilayer chitosan films grafted with phenolic acids and loaded with γ-CD-MOFs encapsulated antifungal agents. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 439, 111247 (2025).

Zhang, Z. H. et al. A double cross-linked film based on carboxymethyl chitosan binding with L-cysteine/oxidized konjac glucomannan with slow-release of nisin for food preservation. Food Chem. 472, 142876 (2025).

Kang, J. M., Lyu, J. S. & Han, J. J. Nanoencapsulation and crosslinking of trans-ferulic acid in whey protein isolate films: a comparative study on release profile and antioxidant properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 303, 140737 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Preparation and application of degradable lignin/poly (vinyl alcohol) polymers as urea slow-release coating materials. Molecules 29, 1699 (2024).

Ferdousi, J. et al. Postharvest physiology of fruits and vegetables and their management technology: a review. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 34, 291–303 (2025).

Liu, J. et al. Fruit softening correlates with enzymatic activities and compositional changes in fruit cell wall during growing in Lycium barbarum L. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 56, 3044–3054 (2021).

Chen, K. et al. Moisture loss inhibition with biopolymer films for preservation of fruits and vegetables: a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 263, 130337 (2024).

Zhao, S. S. et al. Study on electrostatic field assisted freezing temperature storage of grapes. J. Food Eng. 394, 112527 (2025).

Fang, G. Y. et al. Microbial interactions and biocontrol for reducing mycotoxin accumulation in stored rice grains under temperature and humidity variations. Food Res. Int. 217, 116775 (2025).

Mou, L. Y., Lu, Y., Xi, Y. G., Li, G. P. & Li, J. L. Sodium alginate-based coating incorporated with Anemone vitifolia Buch.-Ham. extract: application in peach preservation. Ind. Crop. Prod. 176, 114329 (2022).

Yu, Y., Liu, H. F., Xia, H. R. & Chu, Z. H. Double- or triple-tiered protection: prospects for the sustainable application of copper-based antimicrobial compounds for another fourteen decades. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 10893 (2023).

Wang, S. J. et al. Development of plastic/gelatin bilayer active packaging film with antibacterial and water-absorbing functions for lamb preservation. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 43, 1128–1149 (2023).

Zhang, X. T., Zhang, X. L., Liu, X. C., Du, M. L. & Tian, Y. Q. Effect of polysaccharide derived from Osmunda japonica Thunb-incorporated carboxymethyl cellulose coatings on preservation of tomatoes. J. Food Process. Pres. 43, e14239 (2019).

Modesti, M. et al. Destructive and non-destructive early detection of postharvest noble rot (Botrytis cinerea) in wine grapes aimed at producing high-quality wines. J. Sci. Food Agric. 104, 2314–2325 (2024).

Cai, X. et al. Active curcumin-loaded γ-cyclodextrin-metal organic frameworks as nano respiratory channels for reinforcing chitosan/gelatin films in strawberry preservation. Food Hydrocolloid 159, 110656 (2025).

Zehra, A. et al. Preparation of a biodegradable chitosan packaging film based on zinc oxide, calcium chloride, nano clay and poly ethylene glycol incorporated with thyme oil for shelf-life prolongation of sweet cherry. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 217, 572–582 (2022).

Bai, H. R., Yang, L. Y., Wu, L., Xiao, D. X. & Dong, A. L. D. R. Enhanced food preservation platform integrating photodynamic and chemical antibacterial strategies via geraniol-loaded porphyrin-based MOFs for cherry tomato storage. Chem. Eng. J. 498, 15550316 (2024).

Wei, Z. C. et al. Development of citral-loaded active packaging for fresh-cut preservation using water-resistant γ-cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks modified with cellulose acetate butyrate. Chem. Eng. J. 512, 162482 (2025).

Bai, Z. Y. et al. Recycling of wheat gluten wastewater: Recovery of arabinoxylan and application of its film in cherry and strawberry preservation. Food Chem. X 22, 101415 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Enhanced preservation effects of clove (Syzygium aromaticum) essential oil on the processing of Chinese bacon (preserved meat products) by beta cyclodextrin metal organic frameworks (β-CD-MOFs). Meat Sci. 195, 108998 (2023).

Song, L. L. et al. Physiological and transcriptomic insights into low temperature-induced suppression of internal browning in postharvest pineapple (Ananas comosus L.). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 230, 113811 (2025).

Liu, G. C. et al. Protein/polysaccharide composite nanocoating based on amyloid-like aggregation for fresh-cut fruits preservation. Chem. Eng. J. 519, 165048 (2025).

Mou, L. Y. et al. Sodium alginate coating of Ginkgo biloba leaves extract containing phenylpropanoids as an ecofriendly preserving agent to maintain the quality of peach fruit. J. Food Sci. 88, 3649–3665 (2023).

Mou, L. Y. et al. Preparation of preservation paper containing essential oil microemulsion and its application in maintain the quality of post-harvest peaches. J. Stored Prod. Res. 108, 102388 (2024).

Ul Islam, A., Serseg, T., Benarous, K., Ahmmed, F. & Kawsar, S. M. A. Synthesis, antimicrobial activity, molecular docking and pharmacophore analysis of new propionyl mannopyranosides. J. Mol. Struct. 1292, 135999 (2023).

Salah, E. M. et al. Chemical composition and antifungal activity of Teucrium Leucocladum Boiss. essential oils growing in Egypt using two different techniques. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 10, 51 (2024).

Emam, M., Soliman, M. M. H., Tantawy, M. A., El-Ansari, M. A. & Seif, M. Pentagalloyl glucose and gallotannins from mangifera Indica L. seed kernel extract as a promising antifungal feed additive, in vitro, and in silico studies. J. Stored Prod. Res. 107, 102354 (2024).

Oh, J. X. et al. -Cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks: do solvents make a difference?. Molecules 28, 6876 (2023).

Ahamed, A., Loganathan, V., Mullaivendhan, J., Alodaini, H. A. & Akbar, I. Synthesis of chitosan and carboxymethyl cellulose connect flavonoid (CH-Fla-CMC) composite and their investigation of antioxidant, cytotoxicity activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 300, 140081 (2025).

Lu, T. & Chen, Q. X. Independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partition: A new method for visual study of interactions in chemical systems. J. Comput. Chem. 43, 539–555 (2022).

Rashid, A. et al. Preparation and functional characterization of pullulan-sodium alginate composite film enhanced with ultrasound-assisted clove essential oil Nanoemulsions for effective preservation of cherries and mushrooms. Food Chem. 457, 140048 (2024).

Kang, L. X., Liang, Q. F., Abdul, Q., Rashid, A., Ren, X. F. & Ma, H. L. Preparation technology and preservation mechanism of γ-CD-MOFs biaological packaging film loaded with curcumin. Food Chem. 420, 136142 (2023).

Abdella, A. A. & Elshenawy, E. A. A spatial hue smartphone-based colorimetric detection and discrimination of carmine and carminic acid in food products based on differential adsorptivity. Talanta 282, 127053 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Doctoral Startup Fund of Hubei Minzu University (Grant No. BS25078).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Linyun Mou: conceptualization, methodology, software, data curation, writing-original draft, project administration, and funding acquisition. Jianlong Li: writing-review & editing. Ya Lu: writing-review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mou, L., Li, J. & Lu, Y. Fabrication and postharvest application of alginate/pullulan composite films integrated with citral-loaded α-CD-MOFs for sustainable cherry storage. npj Sci Food 9, 262 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00622-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00622-5