Abstract

Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) has been identified as one of the four famous Chinese carps. The Yangtze River is the main home to silver carp. However, during the “ten-year fishing ban”, illegal fishing frequently occurred, law enforcement agencies failing to discriminate between farmed and wild fish from the Yangtze River. Therefore, there is a strong need to develop a simple and effective method to discriminate between farmed and wild silver carp from the Yangtze River. In this study, 76 fatty acids were analyzed in 266 silver carp samples. The top 8 fatty acids that exhibited the best performance were identified as candidate biomarkers. The different origins of wild silver carp were also identified. Based on receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, myristic acid proportion of total fatty acids was considered as a biomarker which has high sensitivity and specificity in discrimination of farmed and wild silver carp.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) is a native freshwater fish of the Cyprinida family. As one of the four famous Chinese carps, it is widespread in the Yangtze River Basin of China and other Asian countries as well. The production yield of silver carp ranked five among the top ten most important farmed fish species in the world and its output in 2022 was estimated to over 5 million tons1. Farmed silver carp can be roughly divided into cage farming and pond farming. Among them, cage farming fully utilizes water resources with lower costs and can achieve large-scale aquaculture. Pond farming mainly relies on inter-culturing, with blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala), grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) and black carp (Myxocyprinus asiaticus) combined for aquaculture2. Farmed silver carp mainly feed on soybean dregs, soybean milk, rice bran and formula feed.

The Yangtze River is rich in wild silver carp resources and the main breeding sites of silver carp are situated in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River3. However, from the reports, as early as the1980s, many species of fish, such as grass carp, black carp, silver carp, and bighead carp in the Yangtze River were under grave threat from the Gezhouba Dam4, and the fish stocks in the main river were 4.3 × 105 tons in 1954, declined by 50% in the 1980s and declined further to 8.0 × 104 tons in 20115. The wild silver carp population in the Yangtze River also decreased continuously due to the over-fishing, pollution, and damming6,7. To restore the Yangtze River’s biodiversity, Chinese government instituted a remarkable policy of “ten-year fishing ban” on the whole basin from 20208. Efforts were made to protect various fish species and improve regular monitoring of aquatic life in the Yangtze River9. However, during law enforcement patrols, some violations occurred, and the law enforcement officers failed to discriminate between farmed and wild fish from the Yangtze River, including silver carp. As far as we know, there is no guidelines existing for the discrimination of farmed and wild fish products. A technological innovation for aquatic life protection in the Yangtze River is urgently needed.

Previous studies have investigated the differences in metabolite composition, nutrients and gut microbiota between farmed and wild fish. For instance, employing mass spectrometry imaging, metabolite composition in wild and farmed red sea bream (Pagrus major) was characterized10; fatty acid (FA) contents and composition of different rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) strains were evaluated11; stable isotope and multi-element analysis was used to differentiate wild, lake-farmed and pond-farmed carp12; the nutritional value and safety between wild-caught and cultured fish species were compared13; gut microbiome analysis was applied to the tracking of host source in wild and farmed large yellow croaker14. Such studies are usually based on a substantial data collection and relatively stable geographic environments. Besides, the FA composition of fish can be influenced by age15, sex16, diet17, and environmental conditions18. Previous studies compared FA composition of fish from different areas, but the composition of fatty acid might differ even within the same species19. Hence, identification of potential FAs as predictive biomarkers for discriminating farmed and wild fish can be a challenging task.

Several studies have researched differences in FA between farmed and wild-caught fish20, but under the background of implementing “ten-year fishing ban” of the Yangtze River, no definitive differences in FA between silver carps from the Yangtze River basin and the farmed have been discovered. In our study, we expected to identify candidate biomarkers by profiling the FA of wild and farmed silver carp and then using multivariate statistical analysis to discriminate between farmed and wild silver carp from the Yangtze River. Accordingly, silver carp samples from stem stream, tributaries, lakes and Three Gorges Reservoir Areas of the Yangtze River were examined to select biomarkers that could serve as reliable predictors of their origins through multivariate statistical analysis. Lastly, a novel method was proposed based on FA profiling to discriminate between farmed and wild silver carp from the Yangtze River.

Results and discussion

Differences in FA profiling between wild and farmed silver carp

We detected 37 standard known FA and 39 FA by comparing principal peaks to those in the NIST Standard Reference Database in the fish muscle samples of wild and farmed silver carp, including 31 saturated fatty acids (SFAs), 20 monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and 25 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Among them, C12:0 was the shortest and C24:1n-9c was the longest FA. The contents of SFAs, MUFAs, and PUFAs were 35.43%, 25.58%, and 38.99%, respectively, in farmed silver carp, while 37.71, 30.83, and 31.46% in wild silver carp. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), as major dietary supplements from fish, were approximately equal amount in both wild and farmed silver carp, with 8.95% for EPA, 10.81% for DHA in farmed silver carp and 7.04% for EPA, 10.19% for DHA in wild silver carp, respectively (Table 1).

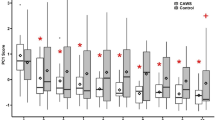

The top 24 FA in the silver carp were presented in a heatmap (Fig. 1). The heat map illustrated distinct differences between wild and farmed silver carp. OPLS-DA was performed to screen for potential biomarkers that could differentiate the two groups (Fig. 2A). The parameters values of R2Y and Q2 were 0.933 and 0.859, respectively, confirmed the reliability of the model. Variable importance (VIP) scores and p-values were also used to view the differences in FA contents and compositions between the two groups (Fig. 2B). There were eight FA exhibiting the best performance among all detected FA with VIP scores greater than 1.0 and p values less than 0.005. The VIP score of OPLS-DA model and p-value of multivariate analysis are routinely utilized as the assessing criteria to discover potential biomarkers21. As a result, the 8 FA were identified as potential biomarkers. Large diversions in the constituents of FA in farmed and wild fish might be due in part to differences in nutritional sources (artificial feeds and natural bait) and environmental factors, such as season, humidity, light, temperature, and physical space18,22,23,24. Wild carps primarily feed on plankton and other small aquatic organisms, like crustaceans, which serve as the main sources of PUFAs25. Farmed carps mainly feed on artificial feeds, which are usually formulated according to the nutritional needs of fish farming, with grains, soybean dregs, and rice bran as the main raw materials. The unsaturated FA in the artificial feeds originated primarily from the addition of soy bean oil and fish oil, as well as aquatic organisms and plant-derived ingredients, making for a higher proportion of unsaturated FA and a lower proportion of saturated FA in the muscle of farmed silver carps. Furthermore, wild silver carps from the Yangtze River and farmed silver carps have huge difference in the living environment. Wild carps live in rivers, lakes and other natural water bodies, with broad space for activities and better water quality. Natural water bodies usually have higher oxygen content, further improving fish activity, resulting in increased FA metabolism. Although size/age differences of silver carps could influence the results, they exert minor effects on fish FA content compared to diet and species-specific factors. In silver carp, the proportions of essential FA, such as EPA and DHA remained stable during early developmental stages (from fertilized eggs to larvae), with no significant variations linked to age26. Studies on Japanese seabass (Lateolabrax japonicus) indicated that growth performance and FA accumulation are more sensitive to dietary DHA/EPA ratios than to age27. Even at different life stages, whole-body and fillet FA profiles align closely with rations28. Therefore, FA profile in the silver carp were performed and its effectiveness to distinguish wild silver carp of different origins were estimated.

A The model evaluated with a goodness of fit (R2Y, 0.933) and goodness of prediction (Q2Y, 0.859). B Top nine fatty acids based on VIP scores obtained by OPLS-DA; The p-value was identified using a t-test, and the fold change was computed using average detection values; red, high level in wild fish samples; blue, high level in farmed fish samples.

Comparison of different origins of wild silver carp by FA analysis

The wild silver carp collected from the Yangtze River can be divided into four origins, including stem stream (Gongan and Hukou), tributaries (Minjiang River and Jialing River), lakes (Dongting Lake and Poyang Lake) and Three Gorges Reservoir Areas. FAs in each origin were depicted in the PCoA plot in Fig. 3. The PCoA plot represented the principal component 1 accounting for 82.25% and the component 2 accounting for 10.05%, respectively. The first two coordinates explained over 90% of total variation. The FAs in silver carps from stem stream, tributaries and lakes overlapped, and PCoA plots revealed no significant separation in FAs among carps from stem stream, tributaries, lakes but a distinct separation between craps from Three Gorges Reservoir Areas and other areas. The four wild groups were separated into two distinct clusters. The construction of dams could significantly alter the natural flow of rivers, which has an obvious impact on the habitat, growth, survival and reproduction activities of aquatic organisms29,30,31. On the one hand, Three Gorges Reservoir has excellent water quality and sufficient food supply for fish32,33. The environmental conditions for fish growth here are also very favorable. The different types of deep water, shallow water, and estuarine wetlands in reservoirs provide suitable habitats for different types of fish. This enables fish in the reservoir to choose suitable living spaces based on their own habits, further improving the survival and reproductive success rate of fish. On the other hand, the huge drop of over 100 meters in the Three Gorges Dam completely hinders the migration of fish, and the turbulent speed and force of the discharge water also block the movement of fish upstream to spawn, resulting in serious ecological problems. According to the statistics, the fish in the Three Gorges Reservoir are generally smaller, especially the four major Chinese carps31. This is coincident with our experimental measurements of average total body length and weight of silver carps (Table 2). The silver carp from the Three Gorges Reservoir could differentiate from stem stream, tributaries and lakes both in FAs and size.

Over the past few years, FA profiling has become a useful tool for tracing the origins of FA-rich foods. Geographical origin of round type hazelnut (Corylus avellena L.) in Turkey was determined using FA composition34. FA profiles and one-class classification methods to identify geographical origin of camellia oil were developed35. Lipids/FA, stable isotopes, and antioxidant capacity profiles to improve the geographical traceability of flaxseed were proposed36. However, this research shows that the failure of a single FA profiling to characterize the origin of silver carp from stem stream (Gongan and Hukou), tributaries (Minjiang River and Jialing River), lakes (Dongting Lake and Poyang Lake) and Three Gorges Reservoir Areas in the Yangtze River. This result may be attributed to the fact that silver carp is a typical migratory fish. They have no fixed habitats in the river and lakes. The living environment will alter as frequent habitats changes. Changes in temperature, acidity, and oxygen content will affect the supply of FA. Moreover, the FA of fish reflect the dietary intake. The food source of wild silver carps from different waters are of far less difference than that between wild and farmed carps.

Selection of candidate biomarker for authentication of farmed and wild silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) from the Yangtze River

P-values generated from two sample t-tests and VIP scores derived from the OPLS-DA model were used to identify deferentially abundant FA that show satisfactory predictive power between the wild and farmed fish. Although OPLS-DA model can be used to identify biomarkers that are useful for the discrimination between the two groups, it is not intuitive enough. Therefore, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was carried out to search for robust biomarkers37. Myristic acid (14:0) was revealed as a promising candidate for a predictive biomarker using ROC statistics analysis (Fig. 4A). The area under the ROC curve (AUC) values were 0.924, with high sensitivity and specificity. Generally, for an excellent model, the AUC value is over 0.9. Therefore, myristic acid (14:0) was used as a biomarker to distinguish farmed from wild silver carp. In general, the difference of the muscle FA in fish is due to the difference in the nutrient composition of the diets38. The results of the study indicated that higher levels of myristic acid in wild silver carps, which suggests myristic acid is an important dietary source for wild silver carps in the Yangtze River. The main food source for wild silver carps was freshwater plankton39, which biosynthesized myristic acid as a key component of their membrane lipids40. Myristic acid is preserved through trophic transfer due to its stability in lipid membranes39. Farmed feeds composition analysis showed that the content of myristic acid in feeds ranged 0.85%-1.16% of total FA, demonstrating minimal inter-farm variation (CV = 11.5%, Supplementary Table 1). Table 3 shows a brief comparative analysis on concentration of myristic acid and the proportion of the total FA between farmed and wild silver carp. The cut-off value was chosen according to the sum of sensitivity and specificity in ROC curve analysis calculated as Eq. (1), which had the maximum Youden index. The concentration of myristic acid was 0.24 ± 0.01 g/100 g for wild silver carp and 0.057 ± 0.006 g/100 g for farmed silver carp, respectively. The myristic acid proportion of total FA was 3.55 ± 0.17% for wild silver carp and 1.52 ± 0.05% for farmed silver carp, respectively.

Myristic acid is a 14 carbon saturated FA, which is commonly found in fish muscle. Although myristic acid is known to play an essential role in cell regulation by modifying a number of proteins41, its excessive consumption can have adverse effects on human health, including increase in plasma cholesterol and mortality42. In this study, myristic acid concentration and its proportion of total FA were both higher in wild silver carps. According to previous study, using the proportion of total FA had higher accuracy and precision than using the concentration43. We compared the ROC curve for myristic acid concentration with its proportion of total FA. The ROC curve for myristic acid concentration showed an AUC value of 0.912 (Fig. 4B), which is relatively lower than using its proportion of total FA. Two model suggested myristic acid is an ideal biomarker to distinguish farmed from wild silver carp, but the former is more accurate. Therefore, a value of 1.60% was taken as a threshold criterion for the decision: any myristic acid value below 1.60% is considered as farmed silver carp, while myristic acid value beyond 1.60% is considered as wild silver carp form the Yangtze River.

Discrimination of farmed and wild silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) from the Yangtze River using myristic acid analysis

To verify the effectiveness of myristic acid as a biomarker for the discrimination of farmed and wild silver carps, we determined myristic acid proportion of total FA in additional ten silver carp samples from the Yangtze River and 10 farmed silver carp samples using the same procedure as described earlier. The myristic acid proportion of total FA were 0.84–1.54% in farmed silver carp and 4.84–6.40% in wild silver carp, respectively (Table 4). Using a cut-off value of 1.60%, 20 silver carp samples were successfully identified, which is consistent with the actual origins of all silver carp samples. The results suggested the developed method by using myristic acid proportion of total FA as a biomarker exhibits robust diagnostic accuracy in discrimination of farmed and wild silver carp. However, FA biomarkers obtained in this study did not take account of fishery processing conditions, such as heating, roasting and frying. Some FA might be unstable under high temperature processing44, and lipid oxidation during fishery processing also affected the composition of FA, failing to reach their full potential as biomarkers. Therefore, controlled stability tests simulating real-world processing-boiling (100 °C, 30 min), pan-frying (180 °C, 10 min) and long-term storage (-20 °C, 7 days)-of different concentrations of myristic acid were conducted. Results showed that myristic acid retained 90.1 ± 3.8% of its initial concentration after cooking and 95.6 ± 1.8% after freezing (Supplementary Fig. 2), confirming its robustness as a biomarker. Additionally, the results of this study were entirely based on wild populations within the Yangtze River basin, thereby limiting direct extrapolation to other ecosystems. As one of Asia’s largest river systems, the Yangtze River is characterized by unique hydrological conditions, geological backgrounds, and ecosystem structures, which collectively shape the physiological adaptations and ecological behaviors of local fish populations. The sediment load, seasonal water level fluctuations, and connectivity of riparian lakes in the middle and lower Yangtze provide specific breeding and distribution patterns for plankton communities. Such hydrogeochemical distinctions may directly influence the compositional structure of plankton communities and their lipid metabolism characteristics45, thereby altering the FA acquired by fish through the food chain. Hence, it is necessary to further validate the effectiveness of the method under different aquaculture and ecosystems before practical applications.

In the current study, we proposed a simple and efficient method based on FA profiling to discriminate between farmed and wild silver carps from the Yangtze River. Among the profiling 76 FA, the top nine FA exhibited the best performance for discrimination between farmed and wild silver carps using hierarchical clustering heatmap and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis, with VIP scores greater than 1.0 and p values less than 0.005. Meanwhile, the different origins of wild silver carps were determined through multivariate statistical analysis. To further select a strong candidate biomarker, ROC curve analysis was performed and myristic acid proportion of total FA was identified as a biomarker which has high sensitivity and specificity in discrimination of farmed and wild silver carps, with an AUC of 0.924. Furthermore, the proportion of myristic acid of total FA displayed a better discrimination performance than using concentration of myristic acid of total FA. By interpreting the results from the myristic acid proportion of ROC model, a cut-off value of 1.60% could accurately identify the actual origin of 20 additional silver carp samples.

This study has proven that the FA profiling as a promising approach to discriminate the farmed and wild fish. However, it is on the basis of the existing aquaculture systems of silver carps, which needs to be further validated under different aquaculture systems in future studies before practical applications.

Methods

Sample collection

Wild silver carp were caught at seven locations from the Yangtze River basin in 2023 (N = 116), using fishing nets, twines, lines and ropes or by traditional skills of cormorant fishing. Seven locations are the Minjiang River (located at E 105.46°, N 28.89°), Jialing River (located at E 108.04°, N 30.29°), the Three Gorges Reservoir Areas (located at E 111.25°, N 30.76°), Gongan (located at E 112.12°, N 29.98°), Dongting Lake (located at E 112.33°, N 29.07°), Poyang Lake (located at E 115.47°, N 28.22°) and Hukou (located at E 116.24°, N 29.76°), covering over 1,500 kilometers of upper, middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Farmed silver carp (N = 150) were obtained from aquatic farms of Hunan province, Jiangsu province, Inner Mongolia, Suizhou city, and Xishui city in Hubei province. These farms replicate near-natural aquaculture practices, such as semi-wild ponds, minimal artificial feed, mimicking the Yangtze River’s ecological conditions. While Inner Mongolia is not a major producer of silver carp, Inner Mongolian farms operate semi-intensive systems with standardized practices, such as controlled feed composition, stable water quality, which minimize environmental variability. This allows clearer isolation of dietary effects on FA profiles. The total body length and weight of silver carp at each site were measured. For wild silver carp, the average body length and weight were 54.10 ± 7.10 cm and 2662.02 ± 970.72 g, respectively. The average body length and weight of farmed silver carp were 59.47 ± 2.22 cm and 4459.00 ± 385.35 g, respectively (Table 2). A flowchart was used to illustrate geographic zones and steps from field collection to GC-MS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). Additionally, ten silver carp samples from the Yangtze River of other locations and ten farmed silver carp samples were applied to assess the efficacy of the determination. All experiments involving silver carps in this study were performed in accordance with the experimental basic principles and were approved by the animal care and use committee of Yangtze River Fisheries Research Institute.

Sample pretreatment

The dorsal muscle of each silver carp was removed. The fish muscle was minced using a mixer grinder. Samples from the same site and batch were homogenized to make a composite and eliminate any between-person measurement bias or individual bias. 2.00 g of homogenized muscle was weighed and transferred into a 50 mL centrifuge tube and 10 mL of chloroform/methanol solution (2:1) were added. The mixture was vortexed for 5 min, then another 10 mL of chloroform/methanol solution (2:1) were added and vortexed for 30 s again. After 10 min of standing, the mixture was filtered and 6 mL of 0.85% NaCl solution was added to the filtrate. The filtrate was vortexed for 5 min and centrifuged for 5 min at 8000 rpm, then the supernatant was removed with a pipette. The residue was dried under a stream of nitrogen. The extract was added with 2 mL of Boron trifluoride-methanol solution 14% in methanol and kept at 80 °C for 45 min. After cooling to room temperature, the sample was dissolved in 1 mL of hexane and 1 mL of deionized water and further centrifuging.

FA analysis

FA were analyzed by a gas chromatograph combined with a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer detector (Thermo Scientific TSQ 9000) and DB-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Agilent, USA). The inlet temperature and injection volume were 250 °C and 1.0 μL, respectively, with a split ratio of 20:1. The oven temperature program was from 110 °C to 160 °C at 10 °C min−1 and held for 1 min, then from 160 °C to 210 °C at 4 °C min−1 and held for 3 min, then from 210 °C to 240 °C at 4 °C min−1 and held for 15 min. FA methyl esters were identified by their retention time and mass spectra, comparing principal peaks to those in the NIST Standard Reference Database and to the standard of 37 FA methyl esters mixture, and quantified by the peak area normalization method. Controlled stability tests simulating real-world processing (boiling, pan-frying and long-term storage) of different concentrations of myristic acid, were conducted. Briefly, myristic acid solutions at varying concentrations (1, 5, 10% w/v) using distilled water were prepared. The solutions were immersed in a boiling water bath maintained at 100 °C, placed into a preheated pan at 180 °C, 10 min and stored in a freezer set to -20 °C for 7 days, respectively. After treatment, solutions were removed to room temperature and homogenized gently before analysis.

Statistical analysis

To assess differences in FA profiles between wild and farmed silver carp, independent two-sample t-tests were performed using Origin Pro 2019b (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Multivariate analyses and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) were performed based on Tutools platform (https://www.cloudtutu.com) using principal component analysis (PCoA) to determine the different origins of wild fish and OPLS-DA to distinguish the wild and farmed carps origin. VIP scores and p-values obtained by OPLS-DA and independent two-sample t-tests, respectively, were used to identify candidate biomarkers for discrimination between the two groups of fish. Finally, ROC curve analysis was performed based on area under the curve (AUC) values to assess the predictive accuracy of selected biomarkers. The optimal cut-off value for FA discrimination was determined using the Youden index (J), calculated as following equation:

This index identifies the threshold that maximizes the combined sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (true negative rate) in ROC curve analysis. The cut-off corresponding to the maximum J (range: 0-1) was selected to balance diagnostic accuracy, avoiding bias toward over-sensitivity or over-specificity.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024 – Blue Transformation in action. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cd0683en. (FAo, 2024).

Szabo, T., Urbanyi, B., Muller, T., Szabo, R. & Horvath, L. Assessment of induced breeding of major Chinese carps at a large-scale hatchery in Hungary. Aquaculture Rep. 14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2019.100193 (2019).

Fang, D.-a. et al. The status of silver carp resources and their complementary mechanism in the Yangtze River. Frontiers in Marine Science 8, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.790614 (2022).

Duan, X. et al. Changes in abundance of larvae of the four domestic Chinese carps in the middle reach of the Yangtze River, China, before and after closing of the Three Gorges Dam. Environ. Biol. Fishes 86, 13–22 (2009).

Xie, P. Biodiversity crisis in the Yangtze River: the culprit was dams, followed by overfishing. J. Lake Sci. 29, 1279–1299 (2017).

Liu, C. et al. Lipid metabolic disorders induced by organophosphate esters in silver carp from the middle reaches of the Yangtze River. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 4904–4913 (2024).

Ji, Q. et al. Total dissolved gases induced tolerance and avoidance behaviors in pelagic fish in the Yangtze River, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 216, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112218 (2021).

Wang, R. et al. Need to shift in river-lake connection scheme under the “ten-year fishing ban” in the Yangtze River, China. Ecol. Indicators 143, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109434 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Challenges to saving China’s freshwater biodiversity: fishery exploitation and landscape pressures. Ambio 49, 926–938 (2020).

Goto-Inoue, N., Sato, T., Morisasa, M., Igarashi, Y. & Mon, T. Characterization of metabolite compositions in wild and farmed Red Sea Bream (Pagrus major) using mass spectrometry imaging. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67, 7197–7203 (2019).

Gladyshev, M. I. et al. Differences in composition and fatty acid contents of different rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) strains in similar and contrasting rearing conditions. Aquaculture 556, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738265 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Differentiating wild, lake-farmed and pond-farmed carp using stable isotope and multi-element analysis of fish scales with chemometrics. Food Chem. 328, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127115 (2020).

Kumari, N., Yadav, D. K., Yasha, Khan, P. K. & Kumar, R. Occurrence of plastics and their characterization in wild caught fish species (Labeo rohita, Wallago attu and Mystus tengara) of River Ganga (India) compared to a commercially cultured species (L. rohita)*. Environ. Pollution 334, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.122141 (2023).

Zhu, J. et al. Robust host source tracking building on the divergent and non-stochastic assembly of gut microbiomes in wild and farmed large yellow croaker. Microbiome 10, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-021-01214-7 (2022).

Tang, H. -g, Chen, L. -h, Xiao, C. -g & Wu, T. -x Fatty acid profiles of muscle from large yellow croaker (Pseudosciaena crocea) of different age. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. B 10, 154–158 (2009).

Liu, J. et al. Sex Differences in Fatty Acid Composition of Chinese Tongue Sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis) Tissues. Fishes 8, https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes8080421 (2023).

Zou, J. et al. Effects of different diets on fatty acid composition and nutritional values of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Aquac. Res. 53, 2287–2297 (2022).

Satoh, Y., Ishikawa, Y. & Tani, T. Enhancement of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid contents in a Japanese flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus, by low-temperature rearing. Aquaculture 582, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2023.740510 (2024).

Fonseca, V. F., Duarte, I. A., Matos, A. R., Reis-Santos, P. & Duarte, B. Fatty acid profiles as natural tracers of provenance and lipid quality indicators in illegally sourced fish and bivalves. Food Control 134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108735 (2022).

Zheng, J.-L. et al. Comparative study on the quality of wild and ecologically farmed large yellow croaker through on-site synchronous sampling from the Nanji Archipelago in the East China Sea. Aquaculture 591, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.741098 (2024).

Silva, S. O. et al. NMR spectroscopy as a tool to probe potential biomarkers of the drying-salting process: a proof-of-concept study with the Amazon fish pirarucu. Food Chem. 448, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.139047 (2024).

Keva, O. et al. Allochthony, fatty acid and mercury trends in muscle of Eurasian perch (Perca fluviatilis) along boreal environmental gradients. Sci. Total Environ. 838, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155982 (2022).

Jiang, H. et al. Sustainable lipids production in algal-bacterial consortia under low light intensity: regulation of light-dark on fatty acid composition. Chem. Eng. J. 505, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.158987 (2025).

Umana, M., Wawrzyniak, P., Rossello, C., Llavata, B. & Simal, S. Evaluation of the addition of artichoke by-products to O/W emulsions for oil microencapsulation by spray drying. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 151, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112146 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Evaluation of the control effect of bighead carp and silver carp on cyanobacterial blooms based on the analysis of differences in algal digestion processes. J. Cleaner Prod. 375, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134106 (2022).

Zarei, S. M., Baboli, M. J. & Sary, A. A. Fatty acid composition of Hypophthalmichthys molitrix during embryogenesis and larval development. Life Sci. J.-Acta Zhengzhou Univ. Overseas Ed. 10, 882–885 (2013).

Xu, H. et al. Dietary docosahexaenoic acid to eicosapentaenoic acid (DHA/EPA) ratio influenced growth performance, immune response, stress resistance and tissue fatty acid composition of juvenile Japanese seabass, Lateolabrax japonicus (Cuvier). Aquac. Res. 47, 741–757 (2016).

Araujo, B. C. et al. Effects of different rations on production performance, spinal anomalies, and composition of Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) at different life stages. Aquaculture 562, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738759 (2023).

Zargari, A., Salarijazi, M., Ghorbani, K. & Dehghani, A. A. Effect of dam construction on changes in river’s environmental flow (case study: Gorganrood river in the south of the Caspian Sea). Appl. Water Sci. 13, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-023-02011-3 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Responses of macroinvertebrate functional trait structure to river damming: from within-river to basin-scale patterns. Environ. Res. 220, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.115255 (2023).

Wei, X.-Y., Hu, H., Liu, L., Wang, Y.-B. & Pei, D.-S. Influence of large reservoir operation on change patterns of fish community assembly and growth adaption at low and high-water levels. Ecol. Indicators 155, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.111019 (2023).

Sang, C., Tan, L., Cai, Q. & Ye, L. Long-term (2003-2021) evolution trend of water quality in the Three Gorges Reservoir: an evaluation based on an enhanced water quality index. Sci. Total Environ. 915, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169819 (2024).

Xiang, R., Wang, L., Li, H., Tian, Z. & Zheng, B. Water quality variation in tributaries of the Three Gorges Reservoir from 2000 to 2015. Water Res. 195, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2021.116993 (2021).

Tufekci, F. & Karatas, S. Determination of geographical origin Turkish hazelnuts according to fatty acid composition. Food Sci. Nutr. 6, 557–562 (2018).

Dou, X. et al. Geographical origin identification of camellia oil based on fatty acid profiles combined with one-class classification. Food Chem. 433, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.137306 (2024).

Liang, K., Zhu, H., Zhao, S., Liu, H. & Zhao, Y. Determining the geographical origin of flaxseed based on stable isotopes, fatty acids and antioxidant capacity. J. Sci. Food Agriculture 102, 673–679 (2022).

Hoo, Z. H., Candlish, J. & Teare, D. What is an ROC curve? Emerg. Med. J. 34, 357–359 (2017).

Montenegro, L. F. et al. Improving the antioxidant status, fat-soluble vitamins, fatty acid composition, and lipid stability in the meat of Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) fed fresh ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam). Aquaculture 553, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738067 (2022).

Zhang, C. et al. Phytoplankton control by stocking of filter-feeding fish in a subtropical plateau reservoir, southwest China. Front. Marine Sci. 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1251469 (2023).

Domaizon, I., Desvilettes, C., Debroas, D. & Bourdier, G. Influence of zooplankton and phytoplankton on the fatty acid composition of digesta and tissue lipids of silver carp: mesocosm experiment. J. Fish. Biol. 57, 417–432 (2000).

Prasath, K. G. et al. Anti-inflammatory potential of myristic acid and palmitic acid synergism against systemic candidiasis in Danio rerio (Zebrafish). Biomed. Pharmacotherapy 133, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111043 (2021).

Fernandez, M. L. & West, K. L. Mechanisms by which dietary fatty acids modulate plasma lipids. J. Nutr. 135, 2075–2078 (2005).

Yang, J. et al. Development of biomarkers to distinguish different origins of red seabreams (Pagrus major) from Korea and Japan by fatty acid, amino acid, and mineral profiling. Food Res. Int. 180, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2024.114044 (2024).

Biandolino, F., Parlapiano, I., Denti, G., Di Nardo, V. & Prato, E. Effect of different cooking methods on lipid content and fatty acid profiles of Mytilus galloprovincialis. Foods 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10020416 (2021).

Yi, M. et al. Spatiotemporal variations of plankton communities in different water bodies of the Yellow River: Structural characteristics, biogeographic patterns, environmental responses, and community assembly. J. Hydrol. 640, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.131702 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The work is supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFF0608203) and Key Research and development Program of Hubei Province (2023BBB051).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.L.: Methodology, Investigation, Writing original draft. H.Z.: Methodology, Formal analysis. X.D.: Writing-review & editing. L.Z.: Methodology, Resources. Y.Y.: Validation, Data curation & editing. J.P.: Data curation. J.G.: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, T., Zhang, H., Duan, X. et al. Development of biomarkers for discrimination of farmed and wild silver carp by fatty acid profiling. npj Sci Food 9, 280 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00637-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00637-y