Abstract

Premium greentea has gained worldwide popularity in recent years, but the dynamic changes in its aroma have presented sensory challenges for a long time. This research explored dynamic perception and emotional responses to the smell of representative premium green teas through the application of the Temporal Dominance Of Sensations (TDS) and Temporal Dominance of Emotions (TDE) methodologies. The results revealed that the key dominant attributes of four premium green teas were defined as “tender”, “high”, “floral”, “chestnut” and “fresh”. Positive sentiments in consumers were evoked by continuous sniffing of these aroma from premium green tea. Furthermore, the sensory drivers that elicit specific emotional responses were found. A “rich” emotion was induced by a “chestnut” aroma, while an “unexpected” emotion was induced by a “high” aroma. The increase in the “fresh” aroma as the temperature decreased was unexpected for consumers, which enhanced their experience and brought pleasure. This study could be used as a valuable reference for the odour regulation of new tea products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Premium Green tea is widely recognized for its unique qualities and health benefits, and accounts for a large share of global tea consumption1. The unique aroma of premium green tea has attracted attention from researchers, who have investigated the influence of variety1, processing2, storage3 and brewing4. Current flavor chemistry research primarily relied on chemical detection and quantitative descriptive analysis to identify aroma compounds and correlate them with sensory perceptions2,4. Although the method profiled the aroma of tea, it tends to overlook the dynamic changes in aroma over time5,6. The traditional sensory evaluation methods summarize the tea’s aroma at varying sniffing temperatures, but only discontinuously capture the temporal dynamics of aroma profiles. The Methodology for Sensory Evaluation of Tea (GB/T 23776-2018) requires experts to assess the quality of tea aroma by combining hot sniffing (with a cup temperature of ~75 °C), warm sniffing (with a cup temperature of ~45 °C), and cold sniffing (with a cup temperature close to room temperature). Meanwhile, these two evaluation methods pay less attention to consumers feelings, while consumer experience was directly influenced in the sensory characteristic7. Consequently, identifying dynamic aroma drivers behind emotional experiences is significant for developing new product flavor and enhancing the tea drinking experience for consumers.

Temporal Dominance of Sensations (TDS) quantifies the process of the temporal evolution of the different sensations during food and drink consumption by the dominance rate of sensory attribute. TDS has been successfully applied to many product categories, especially in the evaluation of liquid, like beer8, wine9, olive oils10, soup11 and coffee12. Sophie Meillon et al. used the TDS to point up temporal differences between wines that did not appear with the conventional sensory profile13. Temporal Dominance of Emotions (TDE) developed by Gerry Jager et al., replaces sensory attributes with emotions14. It seeks to recreate the consumer’s experience as similarly as possible to reality and understand the reasons behind differences in preference15. David Labbe et al. reported similar results in their study on the consumption of coffee, from the heating of the water to the drinking of the beverage16.

The combination of the TDE and TDS in food product analysis has been extensively used to differentiate between products17,18. The perception of sensory attributes changes the dynamic of dominant emotion was evidented14. Ana Patricia Silva et al. demonstrated that beer with a low hop aroma had “sad” and “herbal” as the closest attributes by using TDE and TDS19. However, in their joint canonical variate analysis, the emotions evoked by sensory were dim even when combining the total duration of dominance. The results that were difficult to interpret have also been presented in other studies20,21,22. Additionally, the impact of tea aroma perception on dominant emotions has not been studied.

In this study, Huangshan Maofeng (HSMF), Taiping Houkui (TPHK), Luan Guapian (LAGP), and Xinyang Maojian (XYMJ) were selected to sniffing at three different temperatures using TDS and TDE methods. The temporal aroma profiles of four premium green teas were defined through the continuous evaluation. And the differences of consumers’ emotional responses were perceived by consumers at the same time stage. In the end, the correlation between sensory characteristics and emotional responses of premium green teas were indicated. This study aims to systematically quantify the differences in the dynamic aroma profiles of four premium green teas and their relationship with consumer emotional responses.

Results

Aroma profiles of premium green tea applying the TDS evaluation

Based on the dominance rate of each attribute, the key quantitative parameters of the TDS curves, including DRmax (maximum dominance rate), Tmax (time of higher than significant level line), and T90%max (time of maximum dominance rate) were calculated. The quantitative parameters related to aroma were summarized in Table 1. MANOVA results showed that temperatures and green tea types all had an effect on dominant sensory profile. Based on DRmax, Tmax and T90%max, the aroma of representative tea samples was highly influenced by the four producing areas (FDRmax = 10.83; FTmax = 4.25; FT90%max = 5.87, p < 0.05). Meanwhile, different temperatures influenced the sensory profile (FTmax = 12.95, p = 0.002; FDRmax = 7.88, p = 0.03). The maximum DRmax values for the key aroma attributes were as follows: “tender” aroma for HSMF reached 66.70%, “high” aroma for TPHK was 51.40%, “chestnut” aroma for LAGP was 61.10%, and “fresh” aroma for XYMJ was 69.40%. The attribute of maximum Tmax and T90%max values was consistent across all samples, with the representative attributes being “tender” for HSMF, “floral” for TPHK, “chestnut” for LAGP, and “fresh” for XYMJ. Most maximum values occurred when the tea was smelled at medium temperature. Therefore, the key dominant attributes were determined for each sample: HSMF exhibited the “tender” aroma, TPHK exhibited the “floral” aroma, LAGP exhibited the “chestnut” aroma, and XYMJ exhibited the “fresh” aroma.

As shown in Fig. 1, all significantly dominant attributes in aroma at different temperatures for each premium green tea were revealed. The heights of the bands are proportional to the mean dominance rates, estimating the importance of each attribute23. The continuous lines for the “tender” aroma in HSMF, the “floral” aroma in TPHK, the “chestnut” aroma in LAGP, and the “fresh” aroma in XYMJ were shown, clearly corresponding to the key dominant attributes mentioned above. Other attributes such as “fragrant and lasting”, “high”, and “pure and normal”, appeared intermittently across the aroma of four premium green teas.

High aroma typically appeared in the early stages of the high and medium temperature sniffing tests, and its dominance rate decreased as the temperature lowered. This phenomenon may be attributed to the significant impact of temperature on aroma composition4 or the influence of multiple sniffings on aroma enrichment. The same trend was observed with “floral” and “fresh” aroma in HSMF, as well as with “tender” aroma in XYMJ. However, “fresh” in TPHK and LAGP increased in prominence as the temperature dropped. Therefore, the four premium green teas exhibited distinct characteristics in terms of aroma types, and a more comprehensive profile of sensations was contributed by three sniffings.

Figure 2 illustrates the Semi-Markov chain of the aroma of four premium green teas, showing only the dominant attributes with transition probabilities greater than 0.1 and dominance rates exceeding the significance level24. The size of attribute circles is proportional to the mean dominance duration of the attribute and the width of arrows is proportional to the value of the corresponding transition probability. The five key dominance attributes, which include the “tender” aroma in HSMF, the “floral” aroma in TPHK, the “chestnut” aroma in LAGP, and the “fresh” aroma in XYMJ, were longest dominance duration and transitioned most frequently. The probability of transitioning from “start” to the key dominant attribute was higher in cold sniffing, especially in LAGP and XYMJ. The probability for a panelist to select the “chestnut” aroma as the first attribute of LAGP was equal to 0.50, and the chestnut aroma continued without transitioning to other aromas. It was worth noting that the transition from other aromas to the key dominant attributes occurred in TPHK and XYMJ. The first selected attribute was “high” aroma, with a probability of 0.21 in warm sniffing of TPHK, and a transition to the “floral” aroma with a probability of 0.12. The aroma Semi-Markov chain of XYMJ is the most complex, with the highest number of attribute transitions. The “pure and normal” to “fresh” aroma transition occurs with probability 0.11, whereas the probabilities for “tender” aroma to “fresh” aroma both in hot and warm sniffing respectively were 0.12 and 0.14.

Emotional responses to premium green teas applying the TDE evaluation

The quantitative parameters related to emotion responses were summarized in Table 2. The MANOVA result showed no significant differences, except for T90%max across different origins (FT90%max = 5.08, p = 0.009). Compared to sensory attribute terms, there were no significant differences in consumers’ emotional responses to the aroma of the four premium green teas at different sniffing temperatures. Similar findings were reported in other studies, indicating that the emotional responses of commercial products within the same product category, when assessed under blind tasting conditions, often differ only to a small or moderate extent25,26. “Mild” was an emotional attribute with the maximum DRmax, Tmax and T90%max. It showed that consumers associated “mild” with premium green tea, which proved that the aroma of premium green tea only induced milder stimulation. This was similar to the emotional fluctuations produced by chrysanthemum aroma6. Therefore, the key emotional dominant attribute was “mild” for all premium green teas.

Additionally, the maximum dominance rate for “rich” and “mild” was the same at 37.00% in the warm sniffing of LAGP. However, in the cold sniffing, the maximum dominance rate for “rich” decreased to 29.50%, while “mild” increased to 42.90%. It was indicated that “rich” emotion could weaken as the sniffing temperature decreases. The aroma of premium green tea at low temperatures caused consumers to experience milder emotions for a longer duration. It was worth noting that both TPHK and XYMJ displayed “pleasant” as the emotion with the longest duration of dominance during consumer hot sniffing.

As shown in Fig. 3, all significantly dominant attributes are displayed as one band, consisting of stacked colored rectangles. The total height of the band remained constant, with the x–axis representing time27. The figure highlights the colored rectangles representing the emotions “rich”, “pleasant”, “interesting”, “mild”, and “unexpected”. These dominant emotions emphasized the fact that smelling a premium green tea evokes positive emotions. The remaining three emotional attributes did not show the significantly dominant attributes.

Notably, the “pleasant” attribute for HSMF disappeared during the cold sniffing. Similar studies have reported that pleasantness and emotional levels vary according to different moments of the experience16. The consumers may recognize various characteristic sensory attributes of premium green teas, leading to changes in both the number and dominance of the emotions. TPHK was the only premium green teas perceived as “unexpected” at the beginning of the hot sniffing. The “interesting” attribute was prominent in the bands for TPHK and XYMJ, especially during the warm sniffing. It could be attributed to the fact that consumers found the aroma of these two samples particularly appealing. The empty sections of the bands indicate periods with no dominant attribute. The duration of time without dominant attributes was longer in the TDE assessment, consistent with findings from other studies12. Additionally, reporting emotions is more difficult than reporting sensations28.

Canonical correlation analysis of the TDS and TDE evaluation

Figure 4 shows the correlation between the seven dominant sensory attributes and five dominant emotional attributes during the three sniffings of the four premium green tea. The total cumulative explained variance contributions had already exceeded 60.00%, indicating that F1 and F2 together explain most of the associations between the datasets. The absolute values of correlation coefficients greater than 0.50 were considered highly correlated with emotions and likely to elicit specific emotional responses. It seemed that the model could better predict emotional reactions to sensory attributes.

The strongest positive correlation was defined between the “rich” emotion and the “chestnut” aroma in three sniffings. This clearly suggests that chestnut aroma elicits a rich emotional response from consumers. It is noteworthy that this one-to-one positive correlation between sensory attributes and emotional attributes was rarely found in other studies. The stronger positive correlations were found between the “unexpected” emotion and the “high” aroma in three sniffings. Moreover, the positive correlation between the “pleasant” emotion and the “fresh” aroma was increased with the sniffing temperature down. This indicates that umami and pure aroma appealed to consumers and made people feel pleasant.

Additionally, during the cold sniffing, there is a strong negative correlation between “unexpected” and “fresh” aroma. This is because the increase in the fresh aroma as the temperature decreases was unexpected for consumers, thus improving the experience and bringing pleasure. “High” aroma was found to show a negative correlation with emotions such as “pleasant”, “interested”, and “mild”. This is most likely due to the fact that some sensations only become dominant after repeated exposure–sensory adaptation29. During the initial stages of evaluating premium green tea, the aroma was strong and excellent, but consumers had not yet developed deeper emotional responses such as “pleasant” or “interested”. In comparison to other sensory attributes, “mild” emotion was slightly influenced by “tender,” “floral,” and “fresh” aroma. The possible explanation for the different emotions evoked by the stimuli during consumption lies in consumers’ familiarity30.

Discussion

This study reveals the aroma profiles of premium green teas, manifesting significant disparities among the four tea types (p < 0.05). In the quantitative parameters of the TDS curves, a larger Tmax value means a longer dominance duration of aroma throughout the evaluation, but it did not necessarily correspond to the highest dominance rate. Consequently, T90%max was similarly important to Tmax, even when associated with the attribute having the maximum Tmax. Based on the standardized TDS bands built by different sniff stages, the subtle differences in premium green tea aroma were further perceived through repeated sniffing. This is consistent with previous research, which suggests that small differences in the sensory profiles of products are only noticeable after repeated perception31. Future studies will examine factors influencing aroma dynamics, such as the constant temperature of the external environment. The computations of Semi-Markov chains were performed on raw data in order to conserve real dominance durations distributions, which were the same as the quantitative parameters. The Semi-Markov chain showed that there was fewer transition between different attributes, indicating low agreement among panelists or that an aroma lasted longer without transitioning to other aromas. The Semi-Markov chain provided valuable information about individual differences in qualitative perception24.

In this study, it was found that the fresh aroma of TPHK and LAGP became more prominent as the temperature decreased. This could be attributed to the fact that the key compound responsible for the fresh aroma has been confirmed to exhibit an increasing trend as steeping temperatures decrease, such as dimethyl sulfide4. As for floral aroma, methyl jasmonate has a high odor intensity and significantly contributes to the orchid-like aroma in premium green teas, which increased as steeping temperatures decrease4. Research on chestnut aroma has shown that compounds such as 3-methyl-butanal, τ-coumarin, and (E)-β-ionone were considered key components that contribute to the distinctive chestnut flavor of green tea32,33. However, the volatile compounds of the four premium green teas have not been characterized chemically. In the future, more refined aroma detection methods can be combined to enrich the content of this study.

Similarly, the different stages of the TDE task, designed to mimic consumption, aided participants in perceiving and appreciating the entire experience22. Based on TDE for consumers’ emotional testing, positive sentiments in consumers were evoked by continuous sniffing of these aroma from premium green tea. “Mild” was defined as the key dominant emotional attribute of all premium green teas. It was also noteworthy that these TDS sensory lexicons were developed for premium green tea from different tea production regions. Especially, “pure and normal” was perceived differently by panelists based on their experience. In hot sniffing, panelists commonly interpreted “pure and normal” to mean “pure”, whereas it was interpreted as “normal” in warm and cold sniffing. Future studies could investigate other foods by further integrating a product–specific lexicon8,12. Similarly, further research on emotional lexicons may be valuable for understanding the emotional responses triggered by specific products. The primary aim of the present study was to conduct a comprehensive analysis of various green teas, identifying sensory attributes that influence consumer emotion.

In the past decade, food–evoked emotions have gained attention for their ability to enhance product value beyond sensory experience, satisfaction, and consumer evaluation, ultimately impacting consumption choices34. This study proposes the “Temperature-sensory-emotion” dynamic correlation model, identifying the sensory drivers that elicit specific emotional responses among the three sniffing temperatures. TDS and TDE were efficiently combined to identify dynamic aroma drivers behind emotional experiences, in accordance with the growing trend of increased consumer involvement in product characterization18. Aligning sensory profiles with emotional responses offers a targeted framework for product development, enhancing consumer satisfaction through products that evoke desired emotions6. The correlations between “interested” responses and each of the sensory attributes were varied, and the absolute values were smaller than 0.50. The reason may be that the four represented premium green teas showed too much uniqueness at the same time during the TDE tasks. This would be undesirable for consumers, as consumer interest would likely be reduced, especially when information about the uniqueness used to achieve aroma distinction is made available to consumers35. The emotional attribute of “no emotion” helped consumers emotion perception during the cold sniffing. In different studies it has also been shown that emotions provide new information36.

However, these relationships are product and culture–dependent and results should be confirmed. Different cultures are familiar with different types of beverages, and that can be reflected in emotional responses34,37. Additionally, testing in the right atmosphere, instead of laboratory experiments might produce more relevant results as highlighted by Armand V. Cardello et al.35. Given the relatively large enough sample size of the current study, further research could explore the consumer segments and confirm this in a different atmosphere.

In conclusion, the current study elucidates the key dominant attributes were defined that “tender” aroma in HSMF, “high” and “floral” aroma in TPHK, “chestnut” aroma in LAGP, and “fresh” in XYMJ. A“rich” emotion was induced by a “chestnut” aroma, while an “unexpected” emotion was induced by a “high” aroma. The increase in the “fresh” aroma as the temperature decreased was unexpected for consumers, which enhanced their experience and brought pleasure. The “Temperature-sensory-emotion” dynamic correlation model was built to explore dynamic perception and its corresponding emotional responses, providing an important reference for further research. In the future, it is expected that the dynamic perception of other types of teas will be explored, expanding their use in odour regulation for new tea products.

Methods

Sample selection

The four green teas selected as representatives of premium green tea were Huangshan Maofeng (HSMF), Taiping Houkui (TPHK), Luan Guapian (LAGP), and Xinyang Maojian (XYMJ). These teas were collected from Anhui and Henan provinces between 2023 and 2024. Among these, 10 samples of each type were collected from four local core production regions of the two mountains. The samples were collected from different distances to ensure a representative selection. Table S1 shows the relationship and codification of teas along with some product information according to the information sheet provided by the producers. To ensure that the samples met the standard processing level, traditional sensory evaluation was performed by six experienced tea experts, following the China national standard for traditional sensory evaluation of tea38. The review scores represented the overall quality were obtained by averaging the scores from six panelists, as shown in Table S1.

According to the international standard on Sensory analysis—Methodology—Balanced incomplete block designs (BIBD)39, 120 sensory panelists evaluated the ten selected samples to simplify tea samples with representative region-related sensory characteristics. The panelists were recruited from Anhui Agricultural University, and all of whom had received at least two years of tea evaluation training. Each panelist randomly sniffed three of ten samples from each region randomly and rated them on a scale of 1–3 for their aroma characteristics (1=unrepresentative, 2=slightly representative, 3=representative). The criteria for the representative green tea samples selection were as follows: the samples’ rank sum difference had to be lower than calculated minimum significant difference value (LSDrank = 12.71), and the top two samples with the highest sum of ranks were chosen.

The following samples were selected as representative based on sensory intensity of regional characteristics: sample 2 and sample 9 of HSMF, sample 3 and sample 6 of TPHK, sample 1 and sample 7 of LAGP, and sample 4 and sample 8 of XYMJ, as shown in Fig. S1. The samples were stored in a conservation-friendly environment, sealed in hermetic bags, at a temperature of 4 °C, and without light incidence.

Experimental protocol and sample preparation

Ethical approval for the involvement of human subjects in this study was granted by Anhui Agricultural University Research Ethics Committee, and all procedures were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines. The reference number of the ethical approval obtained was KJLL2024022, and the privacy rights of human subjects were respected. All participants were informed of the details and risks of this study, and they acknowledged an informed consent statement. They were able to withdraw from the survey at any time without providing a reason. No financial compensation was provided.

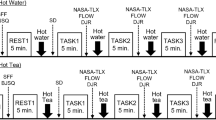

All evaluation sessions were conducted in a temperature controlled, air circulated and red lighting standard sensory laboratory with individual booths according to ISO 8589–2007. During TDS and TDE sessions, the panelists used laptops with the free APPsense® software (version 9.8.2, 2022, Ying Huali Technology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) for data acquisition and analysis. A time interval of 1 s was set, with each sample being repeated three times, and a minimum waiting period of 30 s between samples. Based on the standard38, the assessment of tea aroma quality is carried out in three stages: hot sniffing, warm sniffing, and cold sniffing. Both the panelists and consumers smelled the aroma for 60 seconds during hot sniffing and warm sniffing. During cold sniffing, consumers had less sensory evaluation experience compared to the panelists. As a result, the panelists and consumers smelled the aroma for 30 seconds and 60 seconds, respectively. Prior to the test, the panelists were asked to carefully review the experimental instructions and practice the procedure. The panelists followed the TDS assessment protocol40, with each session lasting approximately sixty minutes.

For each represented sample, 3.0 g of tea was infused in 150 mL of boiling water for 4 min, after which the panelists evaluated the tea’s aroma based on olfactory sensations. The sniffing time points and temperature measurements for each stage were determined. Panelists smelled the brewed tea leaves in the cup at three different time points: immediately after brewing, after 7 min, and after 27 min. Before each sniffing, an infrared thermometer was used to measure the temperature of the cup: high temperature (average 60.11 °C), medium temperature (average 45.71 °C), and low temperature (average 30.87 °C). Panelists were instructed to breathe gently while opening the lid at an angle of less than 30 degrees and holding it 3–5 cm in front of their nose during the test. If the aroma gradually weakened, panelists were instructed to close the lid, gently shake the cup up and down twice, but only during the medium and low temperature phases. After the sniffing session, panelists were provided with coffee beans in a brown bottle to clear residual odors and alleviate olfactory fatigue41. Sample and attribute presentations were randomized for each panelist to minimize order and carryover effects.

TDS and TDE methods

For the TDS evaluation, sixteen panelists (8 females and 8 males, aged 20 to 30 years) were recruited from the sensory panel at the Anhui Agricultural University. All panelists completed a selection questionnaire, meeting the following criteria for approval. First, no health problems. Second, previous participation in tea sensory panels. Third, frequent consumption of green tea. Fourth, interest and availability for training sessions and tests. Panelists underwent at least four weeks of training, including sniffing odorant standards and green teas from different regions. Based on the results of aroma test, the top 12 panelists with the highest accuracy were selected for the evaluation group. The selected panelists participated in three additional training sessions, each lasting approximately one hour and thirty minutes. The training sessions referenced the content produced by Elisete Correia et al.9.

The sensory descriptors used in this study were previously developed through two focus group sessions, each involving 7 panelists and lasting 40 min. The list of aroma attributes (Table 3) was generated based on the highest citation frequencies. During term generation, panelists were asked to identify the dominant sensations during tea tasting and describe their temporal progression. After group discussion, consensus was reached on a list of eight olfactory attributes: pure and normal, high aroma, fragrant and lasting, tender aroma, chestnut aroma, floral aroma, fresh aroma, and tainted odor. TDS evaluations were concluded in eight sessions, one per day. Each session focused on one type of olfactory test, evaluated sequentially. In each test, the panelists alternately evaluated two samples of the same premium green teas’ type, with each evaluation repeated three times.

For the TDE evaluation, a total of 224 tea consumers (122 females and 102 males) aged between 18 and 31 years were recruited. All recruited consumers were free from health problems and were frequent tea consumers. In addition to being requested to read the instructions carefully, all consumers received one–on–one guidance before the experiment.

The emotional attributes used in this study were obtained through a focus group session facilitated by a moderator. To elicit the descriptors, consumers were exposed to four premium green teas’ aroma stimuli and invited to describe their emotions42. Emotions were considered during the aroma assessment at different temperatures, with no limit on the number of emotions reported. Subsequently, the list of emotional attributes (as shown in Table 3) was provided to guide consumers in generating descriptors and to ensure that each participant fully understood the task43,44,45. Emojis were selected from previous studies46,47,48. Finally, eight emotional attributes were identified: pleasant, impressive, mild, rich, unexpected, interested, uncomfortable, and no emotion. In each test, the consumers alternately evaluated four samples, representing the four types of premium green teas.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using XLSTAT (version 2019; Addinsoft, Paris, France) software, including TDS bands, Canonical correlation analysis (CCA), and Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). The quantitative parameters of the TDS curves and the transition probability of the Semi-Markov Chain were calculated using R version 4.1.3 for Windows.

All the TDS and TDE aroma data were standardized to find the relationship between basic sensory and emotional attributes, resulting in 32 groups of standardized data. To ensure the validity of the data, the first six standard time points with all attribute values equal to zero were removed for each group. Finally, 98 data points per group were analyzed using CCA.

Data availability

The code and datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available but can be obtained available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Li, Y. et al. Metabolomics and sensory evaluation reveal the influence of four albino tea cultivars on the quality of processed green tea. FRI 209, 116180 (2025).

Flaig, M., Qi, S., Wei, G. D., Yang, X. G. & Schieberle, P. Characterization of the key odorants in a high-grade Chinese green tea beverage (Camellia sinensis; Jingshan cha) by means of the sensomics approach and elucidation of odorant changes in tea leaves caused by the tea manufacturing process. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 5168–5179 (2020).

Bai, F. et al. Tea storage process: Flavor scalping in green tea caused by plastic packaging materials. Food Packaging Shelf Life 48, 101451 (2025).

Zhu, Y. et al. Characterization of the key volatile compounds in longjing tea (Camellia sinensis) with different aroma types at different steeping temperatures by GC‒MS and GC‒IMS. LWT 200, 116183 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Key aroma components in Lu’an guapian green tea with different aroma types from five tea tree varieties decoded by sensomics. Food Biosci. 61, 104551 (2024).

Xia, Y. et al. An exploratory study on the development of a sensory wheel affiliated with the emotional lexicon for chrysanthemum infusion. FRI 201, 115428 (2025).

Su, T. C., Yang, M. J., Huang, H. H., Kuo, C. C. & Chen, L. Y. Using sensory wheels to characterize consumers’ perception for authentication of Taiwan specialty teas. Foods 10, 836 (2021).

Wakihira, T., Miyashita, S., Kobayashi, M., Uemura, K. & Schlich, P. Temporal Dominance of Sensations paired with dynamic wanting in an ad libitum setting: A new method of sensory evaluation with consumers for a better understanding of beer drinkability. Food Qual. Prefer. 86, 103992 (2020).

Correia, E., Amorim, E. & Vilela, A. Structural equation modeling (SEM) and temporal dominance of sensations (TDS) in the evaluation of DOC Douro red wine’s sensory profile. Foods 11, 1168 (2022).

Pierguidi, L. et al. Markers of sensory dynamics in phenols-rich virgin olive oils under optimal storage conditions. FRI 187, 114438 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. Using temporal dominance of sensations (TDS), multiple-sip TDS, chemical composition evaluation, and microstructural analysis to assess the impact of repeated reheating cycles on chicken soup. Food Chem. 444, 138503 (2024).

Palumbo, J. M. C. et al. Impact of different fermentation times on the microbiological, chemical, and sensorial profile of coffees processed by self-induced anaerobiosis fermentation. Braz. J. Microbiol. 55, 2253–2266 (2024).

Meillon, S., Urbano, C. & Schlich, P. Contribution of the Temporal Dominance of Sensations (TDS) method to the sensory description of subtle differences in partially dealcoholized red wines. Food Qual. Prefer. 20, 490–499 (2009).

Jager, G. et al. Temporal dominance of emotions: measuring dynamics of food-related emotions during consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 37, 87–99 (2014).

Silva, A. P. et al. What’s in a name? The effect of congruent and incongruent product names on liking and emotions when consuming beer or non-alcoholic beer in a bar. Food Qual. Prefer. 55, 58–66 (2017).

Labbe, D., Ferrage, A., Rytz, A., Pace, J. & Martin, N. Pleasantness, emotions and perceptions induced by coffee beverage experience depend on the consumption motivation (hedonic or utilitarian). Food Qual. Prefer. 44, 56–61 (2015).

Danner, L. et al. Context and wine quality effects on consumers’ mood, emotions, liking and willingness to pay for Australian Shiraz wines. FRI 89, 254–265 (2016).

Schouteten, J. J. et al. An integrated method for the emotional conceptualization and sensory characterization of food products: The EmoSensory® Wheel. FRI. 78, 96–1 (2015).

Silva, A. P. et al. Effect of adding hop aroma in beer analysed by temporal dominance of sensations and emotions coupled with temporal liking. Food Qual. Prefer. 75, 54–63 (2019).

Okada, T., Okamoto, S. & Yamada, Y. Affective dynamics: causality modeling of temporally evolving perceptual and affective responses. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 13, 628–639 (2019).

Lorido, L., Pizarro, E., Estévez, M. & Ventanas, S. Emotional responses to the consumption of dry-cured hams by Spanish consumers: A temporal approach. Meat Sci. 149, 126–133 (2019).

Merlo, T. C. et al. Measuring dynamics of emotions evoked by the packaging colour of hamburgers using Temporal Dominance of Emotions (TDE). FRI 124, 147–155 (2019).

Galmarini, M. V., Visalli, M. & Schlich, P. Advances in representation and analysis of mono and multi-intake Temporal Dominance of Sensations data. Food Qual. Prefer. 56, 247–255 (2017).

Lecuelle, G., Visalli, M., Cardot, H. & Schlich, P. Modeling temporal dominance of sensations with semi-Markov chains. Food Qual. Prefer. 67, 59–66 (2018).

Gutjar, S. et al. The role of emotions in food choice and liking. FRI 76, 216–223 (2014).

Spinelli, S., Masi, C., Zoboli, G. P., Prescott, J. & Monteleone, E. Emotional responses to branded and unbranded foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 42, 1–11 (2015).

Monterymard, C., Visalli, M. & Schlich, P. The TDS-bands plot: a new graphical tool for Temporal Dominance of Sensations data. 2nd Conference of the Society of Sensory Professionals, Napa, CA, 27–29 (2010).

Thomson, D. M. Emotion measurement (ed. Meiselman, H. L.) 239 (Woodhead, 2016).

Hewson, L. & Tarrega, A. Time-dependent measures of perception in sensory evaluation (ed. Hort, J., Kemp, S. & Hollowood, T.). 67 (Wiley Blackwell, 2017).

De Houwer, J., Teige-Mocigemba, S., Spruyt, A. & Moors, A. Implicit measures: A normative analysis and review. Psychol. Bull. 135, 347–368 (2009).

Zorn, S., Alcaire, F., Vidal, L., Giménez, A. & Ares, G. Application of multiple-sip temporal dominance of sensations to the evaluation of sweeteners. Food Qual. Prefer. 36, 135–143 (2014).

Wang, H. et al. Influence of fixation methods on the chestnut-like aroma of green tea and dynamics of key aroma substances. FRI 136, 109479 (2020).

Xiao, M. et al. Contribution of aroma-active compounds to the aroma of Lu’an Guapian tea. Flavour Fragr. J. 37, 83–95 (2022).

Hu, X. & Lee, J. Emotions elicited while drinking coffee: a cross-cultural comparison between Korean and Chinese consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 76, 160–168 (2019).

Cardello, A. V. et al. Cognitive and emotional differentiators for beer: an exploratory study focusing on “uniqueness. Food Qual. Prefer. 54, 23–38 (2016).

Gutjar, S. et al. What reported food-evoked emotions may add: a model to predict consumer food choice. Food Qual. Prefer. 45, 140–148 (2015).

van Zyl, H. & Meiselman, H. L. The roles of culture and language in designing emotion lists: Comparing the same language in different English and Spanish speaking countries. Food Qual. Prefer. 41, 201–213 (2015).

GB/T 23776. Methodology for sensory evaluation of tea. Chinese National Standard, http://www.foodmate.net (2018).

ISO 29842. Sensory analysis-Methodology-Balanced incomplete block designs. https://www.iso.org/standard/45702.html (2011).

Pineau, N. et al. Temporal Dominance of Sensations: Construction of the TDS curves and comparison with time-intensity. Food Quality Prefer. 20, 450-455 (2009).

Dorri, Y., Sabeghi, M. & Kurien, B. T. Awaken olfactory receptors of humans and experimental animals by coffee odourants to induce appetite. Med. hypotheses 69, 508–509 (2007).

Guerrero, L. et al. Consumer-driven definition of traditional food products and innovation in traditional foods. A qualitative cross-cultural study. Appetite 52, 345–354 (2009).

Bhumiratana, N., Adhikari, K. & Chambers, E. The development of an emotion lexicon for the coffee drinking experience. FRI 61, 83–92 (2014).

King, S. C. & Meiselman, H. L. Development of a method to measure consumer emotions associated with foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 21, 168–177 (2010).

Spinelli, S., Masi, C., Dinnella, C., Zoboli, G. P. & Monteleone, E. How does it make you feel? A new approach to measuring emotions in food product experience. Food Qual. Prefer. 37, 109–122 (2014).

Velázquez, A. L. et al. Children’s reaction to sugar reduced dairy desserts in the context of the implementation of nutritional warning labels: an exploratory study. FRI 170, 113001 (2023).

Peltier, C., Visalli, M. & Thomas, A. Using temporal dominance of emotions at home. Impact of coffee advertisements on consumers’ behavior and methodological perspectives. Food Qual. Prefer. 71, 311–319 (2019).

Schouteten, J. J., Llobell, F., Chheang, S. L., Jin, D. & Jaeger, S. R. Emoji meanings (pleasure–arousal–dominance dimensions) in consumer research: Between-country and interpersonal differences. J. Food Sci. 88, A106–A121 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the undergraduates from Anhui Agricultural University who provided assistance in sensory tests and scholars who gave advice on this research. This work was supported by the earmarked fund for CARS–19 and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD1601102).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Q. and W.J. contributed to the conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing of the original draft, and writing–review & editing. L.Z., J.L., Q.A., Y.Z., and X.Z. contributed to formal analysis and investigation. Z.Z. and S.W. contributed to methodology and data curation. Q.J. contributed to methodology. X.Z. contributed to writing–review & editing. Q.D. supervised the project, acquired funding, and contributed to conceptualization, methodology, and writing–review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiu, T., Ji, W., Zhao, L. et al. Dynamics of aroma profiling and emotional response for premium green tea. npj Sci Food 10, 23 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00670-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00670-x