Abstract

Mental rotation, a crucial aspect of spatial cognition, can be improved through repeated practice. However, the long-term effects of combining training with non-invasive brain stimulation and its neurophysiological correlates are not well understood. This study examined the lasting effects of a 10-day mental rotation training with high-definition transcranial direct current stimulation (HD-tDCS) on behavioral and neural outcomes in 34 healthy participants. Participants were randomly assigned to the Active and Shan groups, with equal group sizes. Mental rotation tests and EEG recordings were conducted at baseline, 1 day, 20 days, and 90 days post-training. Although HD-tDCS showed no significant effect, training led to improved accuracy, faster response times, and enhanced task-evoked EEG responses, with benefits lasting up to 90 days. Notably, task-evoked EEG responses remained elevated 20 days post-training. Individual differences, such as gender and baseline performance, influenced the outcomes. These results emphasize the potential of mental rotation training for cognitive enhancement and suggest a need for further investigation into cognition-related neuroplasticity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental rotation (MR) is a crucial spatial cognitive function, involving the mental manipulation of object representations within two- or three-dimensional spaces1. Previous studies have demonstrated that visuospatial capabilities, including MR, substantially support cognitive operations within spatial contexts, thereby facilitating academic achievements in disciplines such as mathematics and chemistry2,3. Moreover, recent empirical studies highlight the critical role of MR in human spaceflight activities, particularly in tasks involving human-controlled rendezvous and docking procedures4,5.

Interestingly, several studies have shown that MR abilities can be enhanced through various interventions6,7,8,9, including repetitive practice with computer-based cognitive tasks, virtual and augmented reality techniques, and activities such as playing with Legos7,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Training methodologies for enhancing MR capabilities are diverse, with their efficacy varying according to task type, task complexity, and training intensity12,15,17. Gilligan et al. found that computer-based spatial training in children not only improved MR abilities but also simultaneously enhanced mathematical skills18. Although virtual and augmented reality techniques are still emerging, they offer promising opportunities for enhancing MR7,12,15. Similarly, evidence suggests that engaging in games such as Lego can improve MR capabilities8,13.

In addition to cognitive training, novel brain stimulation techniques, such as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), have shown promise in enhancing complex cognitive functions, including emotion regulation and working memory19,20. These findings suggest the potential feasibility of applying tDCS to MR training. Studies have demonstrated that tDCS can modulate cognitive functions by delivering a low electrical current to specific brain regions, such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which is essential for executive function, and the parietal cortex, which plays a key role in spatial cognition21,22. The effectiveness of tDCS depends on current intensity (typically 1–2 mA), session duration (usually 20–30 min), and session frequency (ranging from a single session to multiple sessions over several weeks)23. Zhu et al. found that a 20-min anodal tDCS with 1.5 mA applied to the parietal lobe improved MR performance and reduced gender differences22. However, existing studies on tDCS in MR tasks primarily focus on the immediate effect observed in single-session experiments, while research on the combined effects and long-term effects of tDCS and multi-session training is limited.

Despite some interesting results from studies on tDCS and cognitive training, respectively, the long-term effects and persistence of improvements after training remain unclear. There is a lack of sufficient evidence to conclusively assert the long-term benefits and their neurophysiological underpinnings. While some studies observed significant skill retention three weeks after training24,25, Gilligan et al. noted an absence of prolonged after-effects subsequent to the training regimens18. Short-term neurophysiological effects have been observed26,27. For instance, Tiwari et al. reported that during the MR task, the left cerebral hemisphere exhibited alpha desynchronization, with neural activation observed in frontal-parietal regions28. Feng et al. observed an increased amplitude of MR-related negativity during MR tasks in athletes29. However, these neurophysiological correlates require further validation over extended periods after training, although preliminary studies suggest alterations in brain activity following training15,27,28,29,30,31. Notably, Zhang et al. observed enhanced frontoparietal coherence in trained students compared to untrained students after 25 days of training30. This emphasizes the need for continued research focusing on the long-term impact, not only on behavioral performance but also on neurophysiological changes.

The event-related potential (ERP) technique, which extracts neural responses to specific events from the EEG, serves as a powerful non-invasive tool for understanding cognitive functions and the effects of brain intervention methods32. The P300 ERP component has been widely studied as a marker of cognitive processes, particularly in tasks involving attention and working memory33,34. Individual differences in P300 responses, such as amplitude and latency, are strongly correlated with performance on cognitive tasks, including visual-spatial tasks35. Polich et al. described the P300 component as a neurophysiological indicator of cognitive resource allocation, with its amplitude reflecting the efficiency of neural processing36. A higher P300 amplitude is generally associated with more efficient mobilization of cognitive resources for information processing.

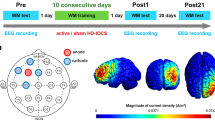

The present study aimed to examine the long-term effects of combining high-definition tDCS (HD-tDCS) with MR training on both behavioral and neurophysiological measures. Additionally, we explored the impact of gender and individual differences in ability on training outcomes. Thirty-four healthy college students participated in a 10-day MR training experiment (as shown in Fig. 1), during which either active or sham HD-tDCS was applied to the parietal lobe. Behavioral testing, involving 75° and 150° three-dimensional MR tasks, and EEG recordings were conducted at baseline (pre-test), immediately after training (post1-test), and at 20 days (post2-test) and 90 days (post3-test) post-training to assess behavioral performance and neurophysiological responses. Behavioral performance and ERPs were analyzed to evaluate the effects of training, tDCS, and their interaction, particularly focusing on long-term aftereffects. The potential influence of gender and baseline performance on training outcomes was also investigated. We hypothesized that the combination of training and tDCS would not only improve MR performance immediately after training but also produce long-term behavioral and neurophysiological aftereffects.

a Experimental procedure. b The schematic representation of the single trial. c The schematic of the relationship between 3D mental rotation materials. d The protocol and the current model of HD-tDCS. MRT mental rotation task, tDCS transcranial direct current stimulation. Blue triangles and rectangles represent the acquisition of behavioral data, and green triangles represent EEG data acquisition.

Results

Effects of HD-tDCS combined with training

We initially evaluated the impact of HD-tDCS combined with training on behavioral and neurophysiological measures. The response accuracy (ACC), the response time (RT), and the global field power (GFP) of P300 ERP are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1. For ACC and RT, bootstrap-based two-way mixed-design (MD) ANOVAs showed significant main effects of Time (pre-test, post1-test, post2-test, and post3-test), but neither Group (Active and Sham) main effect nor Group × Time interaction effect in both tasks (statistical results are detailed in Supplementary Table 1). Bootstrap-based two-way MD-ANOVAs with false discovery rate (FDR) correction of point-by-point GFP identified significant main effects of Time at specific time windows (75°: 225–290 ms; 150°: 200–300 ms), but neither significant main effects of Group nor interaction effects were detected. Interestingly, the statistically significant region of point-by-point GFP closely resembled the P300 time interval identified from prior knowledge. Consequently, we further analyzed the mean P300 GFP over a time window of 200–300 ms. For P300 GFP, a bootstrap-based two-way MD-ANOVA showed a significant main effect of Time, but neither the Group main effect nor the Group × Time interaction effect (detailed in Supplementary Table 1).

Given the absence of group effects in behavioral measures and GFP, participants from both groups were pooled to focus on the main effect of Time. The behavioral ACCs and RTs are shown in Fig. 2. Bootstrap-based one-way repeated measures (RM) ANOVAs showed a significant main effect of Time for all measures (75° ACC: F(3, 99) = 175.80, P < 0.001, \({partial}{\ \eta }^{2}\) = 0.842; 75° RT: F(3, 99) = 196.04, P < 0.001, \({partial}{\ \eta }^{2}\) = 0.856; 150° ACC: F(3, 99) = 178.73, P < 0.001, \({partial}{\ \eta }^{2}\) = 0.844; 150° RT: F(3, 99) = 40.08, P < 0.001, \({partial}{\ \eta }^{2}\) = 0.548). Post hoc tests indicated that the ACC significantly improved in post-tests compared to the pre-test, regardless of task difficulty. Participants exhibited different long-term after-effects of training in the two tasks. In the simple (75°) task, the long-term after-effect was characterized by a sustained increase in behavioral performance followed by a decrease. In the 75° task, the ACC increased significantly at the post2-test compared to the post1-test, while the RT did not change significantly, and there was a significant decrease in the ACC at the post3-test compared to the post2-test, while RT increased significantly. There was no significant difference in ACC at the post3-test compared to the post1-test after training, though RT was significantly increased. In the complex (150°) task, the long-term after-effect was characterized by a decrease over time. The ACC remained constant at the post2-test compared to the post1-test with a significant increase in RT, and at the post3-test there was a significant decrease in ACC compared to the post2-test with a significant increase in the RT. The ACC at the post3-test was similar to the post1-test, however, the RT was significantly larger. The statistical results are detailed in Supplementary Table 2.

The GFP curves are shown in Fig. 3a, b for the 75° and the 150° tasks, respectively. Bootstrap-based one-way RM-ANOVAs with FDR corrections were performed at each point. The P300 GFPs showed a significant effect of Time in both tasks, as revealed by point-by-point bootstrap-based one-way RM-ANOVAs after FDR correction. Significant main effects of Time on the averaged P300 GFP were demonstrated by bootstrap-based one-way RM-ANOVAs (75°: F(3, 99) = 8.93, P = 0.005, \({partial}{\ \eta}^{2}\) = 0.213; 150°: F(3, 99) = 16.39, P < 0.001, \({partial}{\ \eta }^{2}\) = 0.332). Post hoc tests found significant differences between any combination of the four tests for both the 75° and 150° tasks (detailed in Fig. 3a, b, and Supplementary Table 2). These findings indicated a significant increase in P300 GFP after training. Notably, the GFP increase was not only manifest immediately after training but was even more pronounced during the post2-test compared to the post1-test. Although there was a decline in the post3-test, GFP remained significantly elevated compared to the post1-test.

a GFP over time and the P300 GFP (mean \(\pm \,\)SEM) of the 75° task. b GFP over time and the P300 GFP (mean \(\pm \,\)SEM) of the 150° task. The shading indicates statistically significant time points after FDR correction. c The topographies of grand-average P300 and the results of bootstrap-based one-way RM-ANOVA of the 75° task. d The topographies of grand-average P300 and the results of bootstrap-based one-way RM-ANOVA of the 150° task. The solid black dots mark significant channels in the topographies. RM repeated measures. *: \({P}_{{adjust}}\) < 0.05; **: \({P}_{{adjust}}\) < 0.01; ***: \({P}_{{adjust}}\) < 0.001.

Figure 3c, d illustrates the topographies of the mean P300 amplitude alongside the outcomes derived from bootstrap-based one-way RM-ANOVAs. It was evident that the majority of channels displayed a main effect attributable to Time. After training, the distribution of P300 underwent substantial modifications. The topographic map showed an expansion of negative areas in the frontal-central lobe with an increase in amplitude and a narrowing of positive areas in the parieto-occipital lobe with an increase in amplitude. This highlights significant reconfiguration in neural processing after the training intervention, as reflected in the spatial distribution and amplitude of the P300 component.

Effects of gender on training effects

To investigate the impact of gender on training effects, participants were divided into two groups (Female: 17 participants, Male: 17 participants). The behavioral ACC and RT are shown in Fig. 2, while P300 GFP is shown in Fig. 4a, b. Bootstrap-based two-way MD-ANOVAs explained the main effect of Time, but neither Gender (male and female) main effect nor a Gender × Time interaction effect was found (detailed in Supplementary Table 3).

a The P300 GFP (mean \(\pm \,\)SEM) of the 75° task. b The P300 GFP (mean \(\pm \,\)SEM) of the 150° task. c The topographies of grand-average P300 and the results of bootstrap-based two-way MD-ANOVAs of the 75° task. d The topographies of grand-average P300 and the results of bootstrap-based two-way MD-ANOVAs of the 150° task. The solid black dots mark significant channels. MD mixed-design. *: \({P}_{{adjust}}\) < 0.05; **: \({P}_{{adjust}}\) < 0.01; ***: \({P}_{{adjust}}\) < 0.001.

Within-group comparisons (detailed in Supplementary Table 4) showed an increase in ACC accompanied by a decrease in RT and a significant increase in P300 GFP after training in both genders. However, the long-term aftereffects manifested differently in the Male and Female groups concerning task complexity. Notably, the sustainability of training effects was higher in the Male group, with sustained increases evident. In the simple task (75°), the Female group’s behavioral performance remained stable until 20 days post-training, followed by a decline at 90 days. P300 GFP indicated that neuronal activation synchrony increased until 20 days and then declined at 90 days. The Male group, on the other hand, showed a sustained increase in performance up to 20 days with a decline at 90 days, and neuronal activation synchrony increasing up to 90 days after training. Secondly, in the complex task (150°), the Female group’s behavioral performance continued to decline after training, and neuronal activation synchrony ascended until 20 days and declined at 90 days after training. Conversely, the Male group’s performance was maintained for 20 days, declining at 90 days after training, and neuronal activation synchrony continued to ascend for 20 days maintaining until 90 days after training. The P300 ERP results are shown in Fig. 4c, d, indicating changes in ERP polarity distribution after training. The results of bootstrap-based two-way MD-ANOVAs showed a main effect of Time across nearly all channels, with no effect of Gender.

Effects of baseline performance on training effects

To investigate the effect of individual ability on training effectiveness, participants were divided into low-performance (20 participants) and high-performance (14 participants) groups according to accuracy and response time in the 75° task at pre-test using K-means clustering. A chi-square goodness-of-fit test confirmed that there was no significant difference in the number of participants between the groups (\({\chi }^{2}\) = 1.059, P = 0.303).

Behavioral ACC and RT are shown in Fig. 2. Bootstrap-based two-way MD-ANOVAs demonstrated the main effects of Baseline performance and Time in behavioral data but no Baseline performance × Time interaction effect (detailed in Supplementary Table 5). Post-hoc group comparisons showed significantly lower ACC and higher RT in the low-performance group compared to the high-performance group, except for the post1-test’s ACC in the 75° task (detailed in Supplementary Table 6). Within-group comparisons (detailed in Supplementary Tables 7 and 8) revealed significant ACC gains accompanied by significant decreases in RT after training in both groups.

P300 GFP are shown in Fig. 5a, b. Bootstrap-based two-way MD-ANOVAs indicated a main effect of Time, but neither the Baseline performance main effect nor Baseline performance × Time interaction effect was found (detailed in Supplementary Table 5). In the low-performance group, GFP increased after training and continued to increase for 20 days, then declined at 90 days (detailed in Supplementary Table 7). In the high-performance group, GFP did not change immediately after training but significantly increased at 20 days, followed by a decline at 90 days (detailed in Supplementary Table 8). The P300 ERP results are shown in Fig. 5c, d, indicating changes in ERP polarity distribution after training. The results of bootstrap-based two-way MD-ANOVAs indicated that nearly all channels exhibited a main effect of Time, and no effect of Baseline performance was found.

a The P300 GFP (mean \(\pm \,\)SEM) of the 75° task. b The P300 GFP (mean \(\pm \,\)SEM) of the 150° task. c The topographies of grand-average P300 and the results of bootstrap-based two-way MD ANOVAs of the 75° task. d The topographies of grand-average P300 and the results of bootstrap-based two-way MD-ANOVAs of the 150° task. The solid black dots mark significant channels. MD mixed-design. *: \({P}_{{adjust}}\) < 0.05; **: \({P}_{{adjust}}\) < 0.01; ***: \({P}_{{adjust}}\) < 0.001.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the long-term effects of combining mental rotation (MR) training with high-definition transcranial direct current stimulation (HD-tDCS) and explored the neural correlates associated with training-induced improvements. We also conducted exploratory analyses to identify individual differences contributing to variations in training outcomes. Our findings revealed three key insights. First, MR training enhanced spatial cognition, with improvements lasting at least 90 days post-training. Second, behavioral changes continued even after the training period, with significant performance gains observed, particularly within 20 days of training. Third, the training-induced lasting changes in task-related neurophysiological responses.

Our study offered direct behavioral evidence demonstrating that training enhances spatial cognition. After training, the accuracy was significantly increased, the response time significantly decreased, and these performance changes were maintained for at least 90 days after training. Consistent with our behavioral findings, several previous studies have also reported improvements in spatial ability6,16,30. Our findings extended the duration of long-term effects in previous studies from 14 days to 90 days. Taylor et al. applied two training methods—video games and computerized cognitive training—over 60 sessions to improve MR performance. Three-month follow-up revealed greater improvement in the two intervention groups compared to the control group37. Our study revealed that the decline in behavioral performance over time after training was not significant, suggesting that the duration of the long-term effect could potentially be extended within a reasonable time range. This offers insights for future enhancement of spatial cognitive ability.

Interestingly, changes in behavioral performance revealed that cognitive performance continued to improve up to 20 days after training, particularly for simpler tasks. This suggests not only that the long-term effects on behavioral performance were maintained over time, but also that improvement persisted beyond the training period. Such sustained improvement is rare in MR training and has been briefly observed in cognitive training studies, such as Ke et al.’s research on working memory training38. Au et al. conducted a meta-analysis of various studies on working memory training and found that cognitive performance continued to improve at multiple time points, including 1, 3, and 6 months after training39. However, this conclusion has not been thoroughly validated. Melby–Lervag et al.’s review found that only a subset of visuospatial working memory training studies reported continued improvements during follow-up tests, with considerable variation in the durability and scope of the training effects40. These findings highlight the need for diverse study designs and extended follow-up periods to better understand the timeframe for long-term effects.

The ERP results provided strong evidence that training significantly enhanced P300 responses, with a more pronounced increase in P300 GFP and a shift in topographic distribution observed 20 days after training. This suggests that the long-term neurophysiological effects of training mirror the behavioral effects, not only being maintained well beyond the training period but also continuing to evolve afterward. Increases in P300 GFP may indicate more synchronized neuronal activity or a larger neural population, leading to more efficient information processing41,42. These findings support Bozgeyikli et al.’s conclusion that cognitive training may lead to the reallocation of neural resources, thereby improving processing efficiency43. Thus, the P300 GFP results provide direct evidence that more neural resources are synchronously engaged in information processing following training. This could be due to the training enriching global neural resources, thereby increasing the capacity for information processing. Alternatively, the improved MR ability may result in fewer resources being allocated to other MR subprocesses (e.g., rotation, judgment, or decision-making), leading to a relative increase in cognitive resources devoted to visual attention. Another notable effect of training on P300 was the change in topographic distribution. Following training, the P300 field distribution shifted from a broadly positive pattern to a distinctly different one, with an amplification of negative activity in the central frontal region and an enhancement of positive activity in the occipital and parietal lobes. This marked shift in field distribution suggests a modification in the neural substrates underlying the observed P300 component44.

The novel findings, based on both performance and neurophysiological measures, were consistent: training positively affected MR ability and resulted in a lasting cumulative aftereffect. One possible explanation for these effects is that prolonged repetitive training fosters cognitive reorganization and long-term consolidation. This persistent effect, characterized by enhanced brain activity, likely arises from changes in synaptic plasticity. Long-term potentiation (LTP), a sustained enhancement of synapses driven by recent activity patterns, is a form of synaptic plasticity that underpins learning and memory processes45. During MR training, relevant neural circuits are repeatedly activated, promoting the occurrence of LTP, which further strengthens synaptic connections45,46. As a result, information related to spatial cognition is effectively retained over an extended period. Additionally, continuous changes in neuronal firing rates may induce a state of metaplasticity46. Metaplasticity refers to the plasticity of synaptic plasticity, whereby the induction of synaptic changes is influenced by prior salient activity45,47. With regular training over an extended period, high-frequency synaptic activity increases the likelihood of synaptic strengthening. Metaplasticity regulates and prolongs synaptic plasticity, enhancing the stability and persistence of neuronal networks. This mechanism may explain the continued improvements in neurophysiological responses and behavioral performance observed 20 days after training.

The HD-tDCS protocol used in this study was carefully controlled, with stimulation applied for 25 min per day at an intensity of 2 mA. This precise protocol is extensively supported by numerous studies, which collectively suggest that such parameters may elicit a beneficial response19,38,48. Regrettably, HD-tDCS applied to the parietal lobe did not show significant effects. One possible explanation is that the training itself had such a profound impact on MR skills that it overshadowed any effects induced by the electrical stimulation. This highlights the need for further refinement of the stimulation and training protocols. Previous research proposes that current density may influence the enhancement effect of electrical stimulation20, an aspect not yet considered for refinement in the present study. The parietal cortex, the focal point of HD-tDCS, plays a critical role in spatial cognition26,49,50. However, determining the precise functional contributions of different parietal sub-regions poses multifaceted challenges and remains to be fully understood51,52. Regardless of these uncertainties, it can be definitively stated that the precision of target areas for electrical stimulation can be further optimized. This may involve focusing on parietal lobe subregions associated with MR to achieve a more precise modulation effect.

No significant effects of gender or baseline performance differences on the long-term aftereffects of training were observed in either behavioral performance or EEG responses. However, post-training changes did show some variations based on gender and performance levels. The current study supports the notion that individuals with lower baseline spatial abilities may benefit more from training than those with higher baseline abilities. This finding aligns with previous research suggesting that individuals with lower initial performance levels have greater potential for improvement following cognitive training7,17. Further investigation into the underlying mechanisms driving these differences could help tailor training interventions to optimize benefits across individuals with varying baseline abilities.

This study offers evidence demonstrating the enduring benefits of combining HD-tDCS with MR training. Specifically, this research advances our understanding of the neuroplastic mechanisms underlying spatial cognitive skill acquisition and the sustained effectiveness of cognitive enhancement interventions. The observed long-term effects have critical implications for refining cognitive training protocols and contribute significantly to the burgeoning field of neuroenhancement. These findings underscore the potential of multi-session cognitive training to produce long-term cognitive benefits and to enhance professional competence in spatially intensive domains.

Methods

Participants

Thirty-four healthy, right-handed college students participated in this experiment (17 females and 17 males; age: 20 ± 4.43 years; education: 14 ± 3.96 years). Pre-enrollment screening excluded individuals with psychiatric disorders, sustained head injuries, taken psychosomatic or hypnotic drugs, etc., as well as those who had received any transcranial electrical stimulation or transcranial magnetic stimulation within six months. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin University (TJUE-2021-154). All participants signed consent forms and received payments.

Experimental procedure

Prior to the formal experiment, participants were coached to achieve a minimum accuracy of 60% in a 50-degree MR task. Following this acclimatization phase, participants were randomly assigned into two groups—Active or Sham—with a balanced male-to-female ratio in each group. The experimental design was single-blind, ensuring that participants were unaware of their assigned stimulation condition.

The experimental procedure included four testing phases and a ten-day training phase (Fig. 1a). Participants underwent a pre-test one day before the training phase, followed by the ten-day training, and then underwent three tests on the 1st, 20th, and 90th days after training (referred to as pre-test, post1-test, post2-test, and post3-test, respectively). Each testing phase comprised six blocks of three-dimensional (3D) MR tasks, divided into three blocks of 75-degree (75°) rotations and three blocks of 150-degree (150°) rotations. Throughout the testing phases, both behavioral performance (response accuracy and response time) and electroencephalogram (EEG) data were recorded concurrently.

The training phase lasted for ten consecutive days, with participants engaging in a 30-min daily session that included the 3D MR task along with electrical stimulation. Each session entailed one block of task at a fixed difficulty level and four blocks with adaptively calibrated difficulty levels. The difficulty was adjusted based on the participant’s performance from the previous day, with the level increasing by one step on the subsequent day if the participant achieved an average accuracy of 85% or higher on the adaptive difficulty tasks.

Mental rotation task

The Shepard and Metzler paradigm1 with sequential figure presentation was employed in this study. Stimuli were derived from asymmetric combinations of cubes on a black background, sourced from the ‘Library of Shepard and Metzler type Mental rotation stimuli’53. Participants were asked to judge the relationship between the two 3D objects presented in 2D images on the screen (Fig. 1b, c) as quickly and accurately as possible within 5 s. Responses were made using the left arrow key for rotation and the right arrow key for mirroring. Each experimental block comprised 46 trials, with each trial beginning with the display of a “+” symbol for 2 s, followed by stimulus presentation for 5 s (as illustrated in Fig. 1b). The 3D MR tasks were implemented using Psychopy 3.054.

HD-tDCS protocol

HD-tDCS was delivered by a multi-channel transcranial electrical stimulator (NeuroConn DC-STIMULATOR MC, Germany). Five silver chloride electrodes, each with a diameter of 1.5 cm, were utilized. The electrode montage targeted the parietal lobe, which is strongly associated with spatial cognition22,26,51, with the central anode positioned at PZ and the return electrodes placed at CZ, P5, P6, and OZ (Fig. 1d). This 4 × 1 electrode montage enabled precise control of the stimulation intensity and minimized effects on other brain regions20,38. In accordance with previous studies20, the stimulation intensity was set to 2 mA and lasted no more than 25 min per day. Sham stimulation consisted of a 30-s ramp-up and ramp-down period at the beginning and end of the session (Fig. 1d). The electrode montage’s current distribution was modeled on the MNI-152 standard head using the SimNIBS toolbox55.

EEG data acquisition and processing

60-channel EEG data were collected at a sampling rate of 1 kHz, using the Neuroscan SynAmps 2 system and the Curry8 software, with the impedance kept below 20 kΩ. Data were preprocessed using the EEGLAB56 toolbox in Matlab 2019. The raw EEG data were band-pass filtered from 0.5 to 40 Hz. Data were visually inspected to reject channels and segments with intensive noise and referenced to the average of M1 and M2 electrodes. Independent components analysis was implemented to remove artifacts from eye movements and blinks. Rejected channels were replaced by the interpolated average of neighboring channels. The cleaned data were segmented into 1.2 s epochs (0.2 s pre-stimulus and 1 s post-stimulus) and down-sampled to 250 Hz.

ERPs were calculated by averaging the baseline-corrected (−200 to 0 ms) epochs. To examine the effects of training and tDCS on ERPs, the GFP of the ERP curves was calculated for each time point:

where \({u}_{i}(t)\) denotes the ERP amplitude of the channel \(i\) at time point \(t\), \(\overline{u(t)}\) denotes the averaged ERP amplitude of all channels at time point \(t\), and \(N\) denotes the number of channels. The GFP is a global, reference-free, and hypothesis-free measure that provides insights into the underlying neural sources associated with the recorded activity.

Statistical analyses

To avoid issues related to normality assumptions, this study employed bootstrap-based nonparametric statistical methods. These methods bypass the stringent requirements for data normality and homogeneity of variance, using 10,000 replications to ensure robust statistical inference57,58.

To evaluate the effects of combined HD-tDCS and training, bootstrap-based two-way MD Group (Active vs. Sham) by Time (pre-test vs. post1-test vs. post2-test vs. post3-test) ANOVAs were performed on the accuracies, response times, and GFP curves. Drawing from previous studies, we identified time windows (210–290 ms) associated with the neurophysiological features of the MR task29. Time windows were selected where prior knowledge aligned with corrected point-to-point statistical results, leading to a focused time window for P300 analysis. The averaged P300 GFPs in the time window were subsequently analyzed using bootstrap-based two-way MD-ANOVA.

To further examine the training effects, data from both the Active and Sham groups were combined to assess changes over time (pre-test vs. post1-test vs. post2-test vs. post3-test) using bootstrap-based one-way RM-ANOVAs. Then post hoc tests were performed using bootstrap-based T-tests with FDR correction. The averaged ERP for P300 was also calculated, and bootstrap-based one-way RM-ANOVAs with FDR correction were performed for all channels.

The effects of gender and baseline performance on training outcomes were also examined. Participants were divided into Female and Male groups based on gender, and into low- and high-performance groups based on accuracy and response time in the 75° task at pre-test using K-means clustering. The effects of gender and baseline performance on training effects were examined by bootstrap-based two-way MD-ANOVAs in Gender × Time manner and Baseline performance × Time manner, respectively, followed by post hoc tests using bootstrap-based T-tests with FDR correction. All the analyses included estimates of effect sizes (\({{Cohen}}^{^{\prime} }s{\ d}\) for T-tests; \({partial}{\ \eta }^{2}\) for ANOVAs).

Data availability

Anonymized data and code supporting the results of this study are available on the Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/u8bvr/?view_only=8b15ee4846574d319de8b5f4cb15b215 and https://osf.io/dk34q/?view_only=eff6a05772b148c593f48205d31fa0ea.

Code availability

The codes used to analyze the data were based on the functions of the public toolbox EEGLAB and are available from the corresponding authors upon request for academic purposes.

References

Shepard, R. N. & Metzler, J. Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects. Science 171, 701–703 (1971).

Zhu, C. et al. Fostering spatial ability development in and for authentic STEM learning. Front. Educ 8, 323–336 (2023).

Langlois, J., Bellemare, C., Toulouse, J. & Wells, G. Spatial Abilities Training in Anatomy Education: A Systematic Review. Anat. Sci. Educ. 13, 71–79 (2020).

Pan, D., Zhang, Y., Li, Z. & Tian, Z. Association of Individual characteristics with teleoperation performance. Aerosp. Med. Hum. Perform. 87, 772–780 (2016).

Menchaca-Brandan, M. A., Liu, A. M., Oman, C. M. & Natapoff, A. Influence of perspective-taking and mental rotation abilities in space teleoperation. in Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction 271–278 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA). https://doi.org/10.1145/1228716.1228753 (2007).

Ileri, Ç. et al. Malleability of spatial skills: bridging developmental psychology and toy design for joyful STEAM development. Front. Psychol 14, 1137003 (2023).

Velazquez, F. & Mendez, G. Systematic review of the development of spatial intelligence through augmented reality in STEM knowledge areas. Mathematics 9, 3067 (2021).

Parthasarathy, P. K., Mittal, A. & Aggarwal, A. Literature review: learning through game-based technology enhances cognitive skills. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 8, 29 (2023).

Gittinger, M. & Wiesche, D. Systematic review of spatial abilities and virtual reality: the role of interaction. J. Eng. Educ. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20568 (2023).

Piri, Z. & Cagiltay, K. Can 3-dimensional visualization enhance mental rotation (MR) ability?: A systematic review. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2023.2196161 (2023).

Ariali, S. & Zinn, B. Adaptive training of the mental rotation ability in an immersive virtual environment. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 16, 20–39 (2021).

G¢mez-Tone, H., Martin-Gutierrez, J., Anci, L. & Luis, C. International comparative pilot study of spatial skill development in engineering students through autonomous augmented reality-based training. Symmetry—Basel 12, 1401 (2020).

McDougal, E. et al. Assessing the impact of LEGO® construction training on spatial and mathematical skills. Dev. Sci. 27, e13432 (2024).

McDougal, E. et al. Associations and indirect effects between LEGO® construction and mathematics performance. CHILD Dev. 94, 1381–1397 (2023).

Morawietz, C. & Muehlbauer, T. Effects of physical exercise interventions on spatial orientation in children and adolescents: a systematic scoping review. Front. Sports Act. Living 3, 664640 (2021).

Kozaki, T. Training effect on sex-based differences in components of the Shepard and Metzler mental rotation task. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 41, 39 (2022).

Rodán, A., Montoro, P., Martínez-Molina, A. & Contreras, M. Effectiveness of spatial training in elementary and secondary school: everyone learns. Education XX1 25, 381–406 (2022).

Gilligan-Lee, K. A., Hawes, Z. C. K., Williams, A. Y., Farran, E. K. & Mix, K. S. Hands-on: investigating the role of physical manipulatives in spatial training. Child Dev. 94, 1205–1221 (2023).

Romanella, S. M. et al. Noninvasive brain stimulation & space exploration: opportunities and challenges. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 119, 294–319 (2020).

Müller, D., Habel, U., Brodkin, E. S. & Weidler, C. High-definition transcranial direct current stimulation (HD-tDCS) for the enhancement of working memory—a systematic review and meta-analysis of healthy adults. Brain Stimul. 15, 1475–1485 (2022).

Chrysikou, E. G., Wing, E. K. & van Dam, W. O. Transcranial direct current stimulation over the prefrontal cortex in depression modulates cortical excitability in emotion regulation regions as measured by concurrent functional magnetic resonance imaging: an exploratory study. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 7, 85–94 (2022).

Zhu, R., Wang, Z. & You, X. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation over the posterior parietal cortex enhances three-dimensional mental rotation ability. Neurosci. Res. 170, 208–216 (2021).

Narmashiri, A. & Akbari, F. The effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on the cognitive functions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-023-09627-x (2023).

Gerhard-Samunda, T., Jovanovic, B. & Schwarzer, G. Role of manually-generated visual cues in crawling and non-crawling 9-month-old infants' mental rotation. Cogn. Dev. 59, 101053 (2021).

Tone, G., Gehb, G., Kelch, A., Gerhard-Samunda, T. & Jovanovic, B. Locomotion training contributes to 6-month-old infants’ mental rotation ability. Hum. Mov. Sci. 85, 102979 (2022).

Anomal, R. et al. The role of frontal and parietal cortex in the performance of gifted and average adolescents in a mental rotation task. PLoS ONE 15, e0232660 (2020).

Anomal, R. et al. The spectral profile of cortical activation during a visuospatial mental rotation task and its correlation with working memory. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1134067 (2023).

Tiwari, A., Pachori, R. & Sanjram, P. Dimensionality and angular disparity influence mental rotation in computer gaming. Comput. Mater. Contin. 72, 887–905 (2022).

Feng, T. & Li, Y. The Time course of event-related brain potentials in athletes' mental rotation with different spatial transformations. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 15, 675446 (2021).

Zhang, D., Zaphf, A. & Klingberg, T. Resting state EEG related to mathematical improvement after spatial training in children. Front. Hum. Neurosci 15, 698367 (2021).

Ferrara, K., Seydell-Greenwald, A., Chambers, C. E., Newport, E. L. & Landau, B. Development of bilateral parietal activation for complex visual-spatial function: evidence from a visual-spatial construction task. Dev. Sci. 24, e13067 (2021).

Luck, S. J. An Introduction to the Event-Related Potential Technique. (The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2014).

Barry, R. J. et al. Components in the P300: don’t forget the Novelty P3!. Psychophysiology 57, e13371 (2020).

Privitera, A. J. & Sun, R. The P3 and academic performance in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Educ. Res. 128, 102462 (2024).

Gevins, A. & Smith, M. E. Neurophysiological measures of working memory and individual differences in cognitive ability and cognitive style. Cereb. Cortex N. Y. N. 1991 10, 829–839 (2000).

Polich, J. Neuropsychology of p300 | the Oxford Handbook of event-related potential components | Oxford Academic. in Oxford Handbook of Event-Related Potential Components 159–188 (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Taylor, B., Yam, A., Belchior, P. & Marsiske, M. Videogame and computer intervention effects on older adults’ mental rotation performance. GAMES Health J. 10, 198–203 (2021).

Ke, Y., Liu, S., Chen, L., Wang, X. & Ming, D. Lasting enhancements in neural efficiency by multi-session transcranial direct current stimulation during working memory training. Npj Sci. Learn. 8, 1–13 (2023).

Jaeggi, S. M., Buschkuehl, M., Jonides, J. & Perrig, W. J. Improving fluid intelligence with training on working memory. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 6829–6833 (2008).

Melby-Lervåg, M., Redick, T. S. & Hulme, C. Working memory training does not improve performance on measures of intelligence or other measures of ‘Far Transfer’: evidence from a meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 11, 512–534 (2016).

Skrandies, W. Global field power and topographic similarity. Brain Topogr. 3, 137–141 (1990).

Dering, B. & Donaldson, D. I. Dissociating attention effects from categorical perception with ERP functional microstates. PloS ONE 11, e0163336 (2016).

Bozgeyikli, L., Bozgeyikli, E., Schnell, C. & Clark, J. Exploring horizontally flipped interaction in virtual reality for improving spatial ability. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 29, 4514–4524 (2023).

Frodl-Bauch, T., Bottlender, R. & Hegerl, U. Neurochemical substrates and neuroanatomical generators of the event-related P300. Neuropsychobiology 40, 86–94 (1999).

Abraham, W. C. Metaplasticity: tuning synapses and networks for plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 387–387 (2008).

Abraham, W. C. & Bear, M. F. Metaplasticity: the plasticity of synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 19, 126–130 (1996).

Hulme, S. R., Jones, O. D. & Abraham, W. C. Emerging roles of metaplasticity in behaviour and disease. Trends Neurosci. 36, 353–362 (2013).

Parlikar, R. et al. High definition transcranial direct current stimulation (HD-tDCS): A systematic review on the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Asian J. Psychiatry 56, 102542 (2021).

Heil, M. The functional significance of ERP effects during mental rotation. Psychophysiology 39, 535–545 (2002).

Griksiene, R., Arnatkeviciute, A., Monciunskaite, R., Koenig, T. & Ruksenas, O. Mental rotation of sequentially presented 3D figures: sex and sex hormones related differences in behavioural and ERP measures. Sci. Rep. 9, 18843 (2019).

Souza-Couto, D., Bretas, R. & Aversi-Ferreira, T. A. Neuropsychology of the parietal lobe: Luriaas and contemporary conceptions. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1226226 (2023).

Bruner, E., Battaglia-Mayer, A. & Caminiti, R. The parietal lobe evolution and the emergence of material culture in the human genus. Brain Struct. Funct. 228, 145–167 (2023).

Peters, M. & Battista, C. Applications of mental rotation figures of the Shepard and Metzler type and description of a mental rotation stimulus library. Brain Cogn. 66, 260–264 (2008).

Peirce, J., Hirst, R. & MacAskill, M. Building Experiments in PsychoPy 2nd Edition. (SAGE, London, 2022).

Electric field calculations in brain stimulation based on finite elements: an optimized processing pipeline for the generation and usage of accurate individual head models. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.21479.

Delorme, A. & Makeig, S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods 134, 9–21 (2004).

Berkovits, I., Hancock, G. R. & Nevitt, J. Bootstrap resampling approaches for repeated measure designs: relative robustness to sphericity and normality violations. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 60, 877–892 (2000).

Nadine, S. A bootstrapping function for a two-way mixed effects ANOVA. https://github.com/nadinespy/nadinespy.github.io/blob/master/files/bootstrap_2way_rm_anova.R (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFF1200603), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81741139), and the Open Funding Project of the National Key Laboratory of Human Factors Engineering (No. 6142222190105).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.D. and Y.K. designed the study, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; S.L. and D.M. participated in the interpretation of the results. Y.K., X.Z., S.L., and D.M. contributed to the conception and design of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, L., Ke, Y., Zhu, X. et al. Long-term cognitive and neurophysiological effects of mental rotation training. npj Sci. Learn. 10, 16 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-025-00309-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-025-00309-2