Abstract

This study investigates the influence of the pharmacological nigrostriatal dopaminergic stimulation on the entire brain by analyzing EEG and deep electrodes, placed near the subthalamic nuclei, from 10 Parkinsonian patients before (OFF) and after (ON) L-Dopa administration. We characterize large-scale brain dynamics as the spatio-temporal spreading of aperiodic bursts. We then simulate the effects of L-Dopa utilizing a novel neural-mass model that includes the local dopamine concentration. Whole-brain dynamics are simulated for different dopaminergic tones, generating predictions for the expected dynamics, to be compared with empirical EEG and deep electrode data. To this end, we invert the model and infer the most likely dopaminergic tone from empirical data, correctly identifying a higher Dopaminergic tone in the ON-state, and a lower dopaminergic tone in the OFF-state, for each patient. In conclusion, we successfully infer the dopaminergic tone by integrating anatomical and functional knowledge into physiological predictions, using solid ground truth to validate our findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder, imposing a significant socio-economic burden1. The pathophysiology is characterized by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and the consequent depletion of dopamine in the nigrostriatal pathways2. Such alterations disrupt normal activity patterns, affecting brain dynamics on a large scale3. Accordingly, changes in the cortical dynamics are more predictive of clinical symptoms as compared to basal ganglia dynamics4. In turn, the symptoms are not restricted to motor abilities but, rather, involve multiple domains5. In line with this, structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has shown that the areas impacted by PD are more extensive than once believed6. Functional MRI (fMRI) has revealed dysfunctions in the cortico-striatal networks, with these disruptions extending to various other brain regions7. A magnetoencephalography (MEG) study demonstrated global changes in fast brain dynamics in PD, showing stereotyped brain dynamics as compared to controls, with the flexibility of the dynamics shrinking proportionally to clinical impairment8. How does the degeneration primarily occurring in the nigro-striatal pathways impact the whole brain? More specifically, how does the inability to sustain appropriate dopaminergic tone in the nigro-striatal pathways affect activities elsewhere? We aim to elucidate how effective dopaminergic tone influences large-scale brain dynamics, drawing from empirical data9 and utilizing whole-brain models10. To accomplish this, we leverage data acquired from Parkinsonian patients both before (OFF state) and after (ON state) the administration of treatment with L-Dopa. Each patient has six EEG electrodes placed above the motor areas and two deep leads (four contacts each) near the left and right subthalamic nuclei (STN)9. We use the recently described avalanche transition matrix (ATM) to capture the brain dynamics11. Focusing on aperiodic bursts of activities (i.e. neuronal avalanches), the ATMs capture the probability of large-scale activities consecutively propagating across any two regions. The transition probabilities are altered in neurodegenerative diseases12,13, and by the presence of a task14. This way, we quantify the spread of the activities recorded in the electrodes implanted in patients and the EEG both in the ON and the OFF states.

In parallel, we deploy a model, known as the Dody (Dopamine Dynamics) model, that is derived from the adaptive quadratic integrate-and-fire (aQIF) model of individual neurons10. While originally designed for a single population of neurons, we couple the model’s equations according to three different connectivity matrices, representing excitatory, inhibitory, and dopaminergic connections, respectively. We wish to study a variable of interest that represents the dopaminergic tone, and its effect on the whole-brain dynamics. This variable represents the ability of the nigro-striatal pathways to effectively project their activities to the rest of the brain (that is, to effectively respond to a dopamine load). The evolution of local dopamine is captured by a dedicated differential equation, with one term corresponding to the increase of concentration due to dopaminergic projection and a second term capturing the reuptake mechanisms through Michaelis-Menten kinetics15,16, which describes the dynamics of dopamine concentration. In turn, the dopamine concentration impacts the model’s dynamics, as it is included in the equation of the membrane potential. This effect is mediated by the connectome (which we assume to be constant in the ON and OFF state)17, and a free parameter, which is our parameter of interest to estimate, as it provides insights into the effectiveness of the stimulation. We have then projected out the simulated activities to virtual electrodes, thence providing a prediction that can be straightforwardly compared to the empirical data. In simpler terms, the model predicts how changes in dopaminergic tone affect large-scale brain dynamics. Note that these predictions are not informed by the empirical data but, rather represent theoretical arguments.

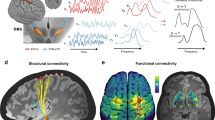

Then, we set out to put our prediction to test by inverting our model. That is, starting from the empirical data, is it possible to unambiguously infer the correct levels of Dopamine? To quantify the uncertainty of the inference, we use a Bayesian framework implemented with advanced probabilistic machine learning techniques, called simulation-based inference (SBI18) to efficiently invert the model19. In other words, we infer the posterior distribution of dopaminergic tone given the features from the empirical data. If our prediction is correct (that is, the model is simulating appropriate dynamics which is changing as a function of the levels of Dopa), we expect that the model inversion would infer higher dopaminergic tone given the data acquired in the ON state, and lower dopaminergic tone when starting from data acquired during the OFF state. We test this in each participant. The overall pipeline is shown in Fig. 1.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is characterized by a progressive decline in dopaminergic neurons and a reduction in dopamine neurotransmitter levels. Progressive degeneration of dopaminergic nigrostriatal neurons leads to PD symptoms such as tremors, instability, slow movement, and stiffness. A common treatment involves administering L-Dopa, a precursor of Dopamine, though the efficacy fades as the disease progresses. This study explores how the nigrostriatal pathways' ability to maintain dopaminergic tone influences brain function. To model the effects of L-Dopa in silico, we develop the Dody Model, a neural-mass model that incorporates dopamine concentration, to obtain a numerical prediction of the expected dynamics (in terms of low dimensional features) given different dopaminergic tones. We analyze data from EEG and deep electrodes in 10 patients with Parkinson’s disease, recorded before and after L-Dopa administration. Then, we utilize Bayesian inference to infer the posterior probability distribution of dopamine concentrations \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\) given the empirical data. To this end, we deploy probabilistic machine-learning techniques (SNPE) to efficiently estimate an invertible function between Dopamine and low-dimensional data features. Picture created with BioRender.com.

Results

Dody model: generation of dopamine-driven dynamics

Starting from the model described in this work10, where dopamine has been included, we modify the connection terms, expanding from a single-node framework to whole-brain according to three distinct layers that simulate different types of neuronal connections: excitatory, inhibitory, and dopaminergic. Each structural connection can be part of one layer (that is, it is either excitatory, inhibitory, or dopaminergic). A connection scaling factor, either wdopamine(wdopa), winhibitor(winh), or wexcitatory(wexc), modulates each layer. In other words, if a connection is excitatory, it will be scaled by wexc, inhibitory by winh, and dopaminergic by wdopa. The connections are shown in panel A of Fig. 2. The types of connections are not merged because they play different roles in the brain. This is encapsulated mathematically as each type of connection enters the equations differently, simulating different action mechanisms.

Panel A: chord diagrams representing the three types of structural connections between 88 brain regions. Connections within these layers are scaled by three factors: wdopamine, winhibitory and, wexcitatory. Panel B: the activities of the entire network (each curve refers to the dynamics of one region) are shown in the phase planes of the fast subsystem composed of the firing rate (r) and the membrane potential (V) as a function of wdopamine (left to right).

A parameter exploration is carried out to observe the qualitative changes in the system dynamics. Previous results describe the behavior of the model at the single node level10. Then, we focus on the network level to understand how the interplay between the three layers of connectivity (excitatory, inhibitory, and dopaminergic) would affect the overall dynamics. For these reasons, we systematically vary the parameters (wdopa, winh, wexc) to shift the system into a different regime. Thus, we set these values within the range that would let the whole-brain model exhibit a rich dynamical repertoire, as observed in brain recordings. In other words, we aim to simulate emerging dynamics at the whole-brain level.

Figure 2 provides an overview of the dynamics generated by the Dody model as a function of wdopa. This simulation aims at mimicking scenarios when patients are being administered L-Dopa. Figure 2, panel B, shows changes in the phase planes of the fast variables, namely firing rate and voltage, as a function of increasing wdopa (left to right). One can see how, as expected, the dynamics of the striatal regions, represented by the yellow, gray, blue, and pink lines, are affected by wdopa.

In the next step, we project the simulated activities to the sensor space using a lead field matrix (Fig. 3, panel A). This is a necessary step, going from the simulated source activities to time series that can be directly compared to the empirical data. Specifically, we project out the source activities to the EEG channels located above the motor-sensory areas bilaterally, that is F3, C3, F4, C4, Fz, and Cz. In short, the sensor-level signals are understood as a weighted linear superposition of all the source-level activities. As per the subthalamic nuclei (STN), the simulated voltages are compared directly to the lead field potential recorded by deep electrodes placed in the STNs bilaterally. Figure 3, panel B, to the left, reports the time series of the simulated voltages in OFF above and below. Going from the bottom to the top, the first six time series correspond to the simulated EEG signals (i.e., after the projection via the lead field), and the remaining two time series correspond to the activities of the subthalamic nuclei (see methods for details).

Panel A: the simulated data are reconstructed at the sensor level for the channels in the motor frontal area, using the lead-field matrix. Panel B: the process of feature extraction from the z-score normalized EEG synthetic data, with the threshold set to θ = 1.5. Panel C: variations of the simulated features as a function of varying wdopa. The range of colors signifies the increase in wdopa. Panel D: validation of the SBI pipeline on 5 random synthetic datasets uniformly selected with wdopa drawn from an interval ranging from 0.05 to 5. The left plot illustrates the estimated values as a black dashed line, corresponding to \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\), which are interpolated by a linear regression line closely following the red dashed line, indicating a perfect fit. The right plot displays the distribution of the posterior z-score versus the posterior shrinkage, indicating an ideal Bayesian estimation (corresponding to z-scores close to zero and shrinkages close to one).

To characterize the spatio-temporal dynamics over a large scale, we utilize avalanche transition matrices (ATMs), which track the spreading of nonlinear bursts. First, the z-scored signals have been binarized and set to 1 for z > 1.5, and to 0 otherwise. This way, the bursts of activations are identified. Then, for each burst, the probability of two channels being consecutively recruited is estimated, obtaining an N × N matrix, with N the number of channels. These matrices are then averaged, element-wise, over the number of bursts, yielding one ATM per dopaminergic tone (i.e., the values of wdopa). Figure 3, panel B, to the right, shows the ATMs for low (top) and high (bottom) dopaminergic tone.

To extensively characterize the whole-brain dynamics, we extract features from the ATMs. We compute from the ATMs the arithmetic mean, the sum, the skewness, and kurtosis. Furthermore, we also compute from the ATMs the Coefficient of Variation, defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean, and its inverse. Finally, the Frobenius norm and the entropy (H) of the matrix, defined as \(H=-\sum p{\log }_{2}p\), where \({\log }_{2}p\) is the base-2 logarithm of the probability distribution of signals, are also computed.

To learn a function to map from the dopaminergic tone to the expected dynamical features, we carry out multiple random brain simulations, each with a wdopa drawn from a uniform distribution (within the ranges of the parameter exploration). Figure 3, panel C, shows the dynamical features as a function of the dopaminergic tone (wdopa). In each plot, each dot refers to the simulated feature at the corresponding value of wdopa. The scatter plots show a distinct relationship between the dopaminergic tone and the generated large-scale dynamics. Then, we perform the Bayesian model inversion starting from the empirical data (yexpt), recorded in each patient’s ON and OFF state. That is, based on the relationships that we found by simulating data features as a function of wdopa, we estimate the most likely \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\) given a set of observed data features.

To estimate the posterior distributions of \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\), we apply simulation-based inference (SBI) for efficient Bayesian model inversion20,21. We utilize a class of machine learning generative models for probability density estimation called Masked Autoregressive Flow (MAF)22, trained with 3000 simulations, each with a value of wdopa drawn from a uniform distribution23. The values of wdopa and the features of the resulting dynamics are fed to the MAF, which learns an invertible function that maps the dopaminergic tone to the expected data features18. Then, the inversion process yields the posterior distribution of the most likely \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\) values (i.e., the conditional probability of \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\) given the data features).

Firstly, we test for the accuracy and reliability of the inversion using synthetic data. To this end, after training the MAF, we perform one more simulation starting from a value of wdopa sampled from the priors. The resulting data features are given to the already-trained MAF to infer the \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\). Finally, we check that the shrinkage of the posteriors around \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\) correctly matches the wdopa (i.e., the ground-truth). As shown in Fig. 3, panel D, to the left, the inferred \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\) (5 random values are shown as examples) converges to the ground truth. The plot illustrates that the estimated values, \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\), are interpolated by a linear regression line, which closely follows the dashed black line that represents a perfect fit, indicating that the inferred parameters correspond exactly to the ground truth values. To the right, there is a zoom on two of these values. Figure 3, panel D, to the right, displays the distribution of posterior z-scores and posterior shrinkage within the Bayesian distribution (see section Methods), highlighting typical pathologies of Bayesian inference. The estimated posterior distributions for different configurations exhibit high shrinkage and low z-scores, which qualifies them as ideal Bayesian estimations. We then characterize the empirically recorded dynamics in the ON and OFF states and then infer the dopaminergic tone from the empirical data.

Empirical differences between patients with and without L-Dopa treatment

While analyzing empirical data, the primary objective is to differentiate the dynamics recorded during the ON state from the one recorded during the OFF state9. We compute, in each patient, the avalanche transition matrices from the EEG and LFP recordings acquired either during the ON condition or the OFF condition. We follow the procedure mentioned above, where each signal (either EEG or LFP) is z-scored and thresholded, and then the ATMs are computed. In summary, the time series and the ATMs, derived from the ON and OFF states, are shown for one subject in Fig. 4, panel A, as an example. One can see that, in the ON-condition, the ATM contains higher transition probabilities. However, the transition probabilities are globally higher in the ON state, as shown in Fig. 4 panel A, top left, for one subject. The other plots in panel B show the difference between the ON and the OFF states in every subject for all the features.

Panel A: starting from the EEG signals, either acquired during the ON or the OFF state, the avalanche transition matrices (ATM) are computed. Panel B: a subset of the features extracted from the EEG signals and ATM matrices, for each subject in the ON (blue) and OFF (orange) states. Note that the parameters show consistent trends (for the ON and the OFF states) in all the subjects.

Model inversion and comparison of the synthetic and the empirical dynamics

Finally, the empirical data features (during the ON or the OFF state) are fed to the trained MAF that yields the posterior distribution for the ON and the OFF states. In other words, for each patient, we obtain the posterior distribution for \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\) given the data recorded during the OFF state (orange) and the ON state (blue), as shown in Fig. 5 panel A. For all patients, the inversion infers a lower dopaminergic tone when starting from data acquired during the OFF state and, conversely, a higher dopaminergic tone when starting from data from the ON state. We regard the ON and OFF states as ground truths, since L-Dopa had been orally given to all the participants before the ON-state recording, likely changing the effectiveness of the dopaminergic stimulation. We use the Wasserstein distance to quantify the differences between the distributions of the estimated \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\) in the two conditions (Fig. 5, panel B). The Wasserstein distance between the posteriors inferred from the ON and the OFF states is always greater than 0, implying that the two distributions are significantly different. Furthermore, we report the shrinkage of the posterior distributions as compared to the priors (that is, the reduction of uncertainty about the “true” wdopa provided by the model inversion, or the level of information in the posteriors as updated from the priors). The shrinkage for all distributions is close to 1, indicating that there is a significant reduction in the uncertainty of dopaminergic tone. Furthermore, we consider the clinical improvement observed in patients in the ON and the OFF conditions, as measured by the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), a comprehensive clinical tool used to quantify the severity of PD symptoms. Specifically, the UPDRS Part III (UPDRS-III) focuses on the motor examination and is pivotal in assessing the motor function of PD patients. For each patient, the differences of the UPDRS-III in the ON and OFF conditions are computed and correlated to the distance between the simulated ATM matrices (generated starting from the inferred \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\) in the ON and the OFF states (r = 0, 49, p-value = 0.09), as shown in panel C of Fig. 5. However, the preliminary data suggest that the generated feature might hold behavioral significance. As a second step, we aim to directly compare the dynamics generated by the numerical simulations in the ON and the OFF states with the corresponding observed empirical dynamics. This step is taken to explore the realism of the generated dynamics beyond the ability to correctly support the model inversion. As shown in panel D of Fig. 5, the analyses focus on the relationship between the power spectra of the simulated and empirical time series derived from the cortical channels (left) and the STNs (right). Firstly, we compute the Spearman correlation between the simulated differences (that is, the frequency-wise differences of the power spectra in the simulated ON - OFF states) and the corresponding empirical ones. The synthetic data are generated by re-simulating the model using the most likely \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\) in the ON and the OFF states, respectively, averaging over 10 simulations, where the time series are different across simulations due to the dynamical noise. The first row of panel D shows, to the left, the Spearman correlation, averaged across cortical channels, between the ON-OFF differences in the synthetic data and the ON-OFF differences in the empirical data for each subject. A similar scheme is used to the right to report the results for the STN (see methods). These results point out the capability of the model to generate dynamically realistic variations, effectively mirroring the empirical data. Notably, changes in the dynamics of the STN in the model arise non-trivially through network effects, since there are no direct dopaminergic connections to the STN.

Panel A: the estimated posterior distributions, for each patient. Higher values are observed in the ON state compared to the OFF state for all subjects. Panel B: the shrinkage of the posteriors and the Wasserstein distance are shown to quantify the uncertainty of the estimated dopaminergic tone. Panel C: Scatterplot showing the clinical improvement (UPDRS-III) between the ON and OFF conditions for each patient (each point represents a patient) and the distance between the simulated ATM matrices (generated starting from the inferred \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\) in the ON and the OFF states (r = 0, 49, p-value = 0.09). Panel D: Comparison of the synthetic and empirical dynamics across Cortical channels (left panels) and Subthalamic Nuclei (STN) (right panels). The first row displays the Spearman correlation ρ between the differences in the power spectra of the ON and OFF states, as computed for the synthetic and empirical data. For all subjects, the observed correlations (green for cortical channels, red for STN) are significantly higher than those expected given chance (gray markers), indicating that the model reliably captures the ON-OFF variations observed in the empirical data. The second row further validates the model by comparing the ON-state differences (synthetic vs. empirical) to the OFF-state differences (synthetic vs. empirical). Consistent correlations across subjects demonstrate that variations in the ON state are mirrored in the OFF state, supporting the model’s robustness in reproducing state-specific dynamical features. In all cases, the p-values are <0.001.

Analogously, the second row of panel D shows the Spearman correlation between ON state differences (synthetic vs. empirical) and OFF state differences (synthetic vs. empirical). The results reveal a positive correlation and a consistent trend across patients, meaning that small differences between the ON states correspond to small differences between the OFF states, and large differences in the ON states are similarly mirrored in the OFF states. This confirms that the model captures empirical ON-OFF variations at the cortical level (to the left) and for the STNs (to the right). To validate all the correlations reported above, we randomize the power spectra by shuffling the frequency bins, to estimate a null distribution of the correlations. This systematic comparison highlights the model’s ability to reproduce realistic and consistent changes in the dynamical features of both cortical and STN signals, well above the chance level.

As a last analysis, we explore the time series of the dopamine concentrations [Dp]e (see Eq. (6)) for different \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\) values, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Striatal regions show higher levels of dopamine in the ON state than in the OFF state.

Discussion

In this work, we implement a model to infer dopaminergic tone in individual patients by combining EEG and intracranial recordings collected before and after L-Dopa administration. By simulating neural dynamics with the model under both ON (with L-Dopa) and OFF (without L-Dopa) conditions, we generate a range of possible system behaviors. These simulations are then used to inform a Bayesian framework, providing an understanding of how the system responds to changes in dopaminergic tone. We then extract relevant features from the empirical data and use them to perform model inversion via deep neural networks. This allows us to estimate the most likely value of the latent parameter wdopa that would result in model dynamics resembling those observed in the empirical recordings. This way, the empirical features guide the inference within a model-informed Bayesian framework. The Bayesian framework allows us to integrate the background knowledge as a prior distribution, and reveal the mechanism(s) starting from macroscopic measurements. Identifying the patient’s state, either ON or OFF, is not based directly on learning statistical features but, rather, on the inference of a biologically plausible mechanism24. This is opposed to other approaches that focus on predicting data patterns based on empirical observations, without providing insights into the causal mechanisms.

The Dody model is a neural mass model based on the adaptive quadratic integrate-and-fire model (aQIF), with some differences from the previous models used thus far10. The neural mass has been modified from25 to include an additional variable capturing the local dopamine concentration. Hence, each connection affects the neural masses differently, according to its nature, that is, dopaminergic, excitatory, or inhibitory. In other words, the neural masses are coupled according to the empirical connectome, where connections can be excitatory, inhibitory, or dopaminergic. This model encapsulates a wealth of well-established information about the specific role of each connection (i.e., the directionality and its type), which has been typically disregarded in large-scale models thus far26,27. To do so, each tract, as measured from the tractography, is considered with directionality and with a specific functional role (as an example, the tract from i to j might be inhibitory while the tract j to i excitatory). The individual structural connectomes are not available. Therefore, unlike typical virtualization pipelines, we build one generic model to perform inference on each patient. As explained, the coupling is done utilizing a connectome computed as the edge-wise average of 10 healthy subjects extracted from the Human Connectome project28. The use of a healthy connectome represents a simplification, especially when modeling a neurodegenerative condition such as Parkinson’s Disease which causes widespread structural changes. However, using standardized structural connectivity enables us to isolate the contribution of pattern activity changes due to dopaminergic effects, without accounting for structural heterogeneity. On the other hand, this might limit the applicability of the model to more advanced cases (without further steps of personalization). This particular design speaks to the validity and the generalizability of our pipeline. In fact, in this work, we aim to capture the functional deficit of the nigro-striatal pathways which is the primum movens in each Parkinsonian patient29. Accordingly, our model simulates the expected changes in terms of large-scale brain dynamics as a function of the nigro-striatal activities. We then set out to provide preliminary validation of the model’s predictions by inferring lower/higher levels of Dopamine from the data acquired in the OFF/ON state. To this end, the same model is inverted starting from data from each of the 10 patients, either in the ON or in the OFF states, and the inversion is successful in each, as shown by the shrinkage of the posteriors. This might be interpreted as the fact that the model, and the features used for the inversion, capture the effects that L-Dopa exerts on the dynamics of patients in general. This mechanistic explanation constitutes a hypothesis of the effect of L-Dopa on the corresponding large-scale activities. Based on this evidence, the forward solutions of our model provide a prediction that is not yet personalized but reproduces the expected changes of a generic set of features as a function of changing Dopaminergic tones30. In future work, each patient will be modeled individually, starting from their structural connectivity data and also integrating more clinical data (e.g., Positron Emission Tomography quantifying Dopamine receptor concentrations). This personalized approach will allow for more accurate, individual-level predictions and tailored simulations. However, the model successfully distinguishes each patient’s ON and OFF conditions. In other words, our model provides an answer to the question “How do changes in the ability of the nigro-striatal pathways to uptake L-Dopa, process it, and release dopamine affect brain dynamics, as observed from a change in data features from large-scale data?” As explained, the inference of the levels of Dopamine should not be understood as a way to tell apart the ON and the OFF states (which is easily attainable from data features alone) but, rather, as a check of the validity of the model. A more comprehensive validation of the model would require an interventional study to verify that the relationship between Dopa and large-scale dynamics holds across the range of values explored by the model. Here, we exploit the fact that we have two different levels of Dopamine available, as they were administered to patients. Hence, the inversion is done to check the ability of the model to correctly and unambiguously distinguish the whole-brain dynamics for the two levels for which we have the “ground truth”. However, as explained, the model’s predictions span a much larger range of values (which we cannot test).

Concerning the data features that we utilize, we focus on the topology of the spread of large-scale aperiodic bursts11,31. This approach is complementary to most traditional methods, which focus on the presence of synchronization or the dynamics of local bursts, typically in the beta band (13–30 Hz)32,33,34,35,36,37. In addition to calculating various features from the EEG signals, we utilize the recently described ATMs to capture the spatiotemporal spreading of each such perturbation11. Of note, we find that the ATMs are at once informative about the large-scale dynamics yet low-dimensional, as we can accurately estimate the posterior distribution from these features (e.g. the mean, the kurtosis, etc.), and observe the corresponding differences between the ON and the OFF states at the individual level. The experimental setting, contrasting each individual before and after the administration of L-Dopa, allows for establishing a causal relationship between the administration of L-Dopa and the changes in the dynamics over the large scale. Nevertheless, revealing a true causal mechanism requires considering inference on multiple causal factors followed by a comparison to the evidence. This aspect requires a thorough investigation and has not yet been demonstrated using SBI. Furthermore, we demonstrate the possibility to define cross-modality connectivity matrices and deploy them for inference, since some transition probabilities are computed starting from deep electrodes and going to EEG electrodes, or vice-versa.

In our scenario, we want to simulate the effects of varying levels of dopaminergic tone (represented by different values of wdopa) on the data features. This allows us to estimate the posterior distributions of \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\), determining the probability of a specific dopaminergic tone given the empirical features observed.

In particular, to estimate the posterior distributions of the parameter of interest, we apply SBI for efficient Bayesian model inversion. This approach is necessary because the calculation of the likelihood function at the whole-brain scale is often intractable, and Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) might be inapplicable for non-parametric sampling. Note that, in the Bayesian setup, the generative model is represented by the joint distribution of model parameters and data, presenting computational and convergence challenges arising from the high dimensionality of the data space, despite the low dimensionality of the parameter space. By harnessing the complexity of mechanistic models and using low-dimensional data features, SBI allows us to efficiently infer the underlying dopaminergic tone from the observed data, providing a robust and neurophysiologically grounded understanding of the system. By using state-of-the-art probabilistic machine-learning tools for probability density estimation, such as MAF, the SBI is an efficient approach, as it relies only on forward model simulations. Moreover, since SBI requires low-dimensional data features for training, the ATM proved useful, since they capture dopamine-induced changes (as validated by the inversion starting from empirical data). Furthermore, the changes in the ATMs are predictive of clinical impairment. However, these results are to be regarded as explorative, given the low numerosity. The applicability of SBI applied to our model is confirmed by the close alignment of predicted and empirical data features, with the model showing particular sensitivity to changes in the dopaminergic tone, capturing a general mechanism, and linking the effect of medical treatment to whole-brain dynamics, which applies to each participant. As confirmation of the reliability and effectiveness of the inversion, we calculate the shrinkage of the posteriors from the priors, to quantify the level of information held therein, starting from the priors. By comparing the shrinkage of the ON and OFF states, we can assess the consistency and reliability of the distributions38.

Finally, we directly compare the differences (ON vs. OFF) in the power-spectral densities of the empirical and simulated (starting from the inferred \({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}}\) in the ON and the OFF states) time series. More specifically, we first compute the Spearman correlation between the frequency-wise differences of the power spectra in the simulated ON-OFF states and the corresponding empirical ones (Fig. 5, panel D). Secondly, we also compute the Spearman correlation between frequency-wise differences of the power spectra (synthetic vs. empirical) in the ON state and the corresponding differences in the OFF state.

Notably, we observe a significant correlation between the differences, indicating that the simulated dynamics capture the empirical effects of Dopamine over the large-scale dynamics.

Additionally, by examining the temporal evolution of the distribution of dopamine concentration, we obtain further confirmation of the validity of our approach. This is evident as we observe distinct features when simulating the ON states compared to the OFF state. While it cannot be checked with the data at hand, our model predicts that patients with lower levels of wdopa will converge to lower concentrations of L-Dopa in the Striatum over time, as opposed to patients with higher levels of wdopa, which will steadily display more L-Dopa. The differences, however, are patient-specific and mediated by network effects. In other words, our model predicts the ability of the nigrostriatal pathway to affect whole-brain dynamics. These theoretical predictions, however, can only be partially tested in the empirical data, as these experiments are prohibitively difficult or impossible to perform. This is the advantage of virtual brain modeling, which allows us to test our hypotheses in silico. As explained, we compare the differences in the power spectra in the ON-OFF states in the simulated and empirical data in the STN (where deep electrodes were placed). We show that the correlation is higher than expected by chance, corroborating the validity of the proposed approach. Note that the effects of L-Dopa in the STN necessarily represent network effects, as no direct Dopaminergic connections are hinging on the STN. Future advancements might involve setting heterogeneous wdopa values for each hemisphere, enhancing the representation of dopaminergic tone variability across brain hemispheres. This strategy could refine clinical interventions (given the clinical asymmetry typical of PD), facilitate comparative studies across brain hemispheres, aid in developing new biomarkers, and improve simulation models30. Importantly, it could enhance research into Parkinson’s Disease by allowing for personalized treatment strategies. This is because accurately estimating the dopaminergic tone based on EEG data dynamics can help predict a patient’s clinical state9. On the one hand, more biological details might be added to the model. On the other hand, more parameters might generate degeneracy and make causal estimation more challenging. Hence, further studies should refine this approach and find an optimal trade-off. Finally, additional studies should specifically address the problem of dyskinesias or uncontrolled involuntary movements.

Our work complements most of the current modeling literature in PD, which primarily focuses on the simulation of activities in the beta range39,40. We focus on aperiodic activities instead, which have only received limited attention in Parkinson’s disease thus far. Furthermore, we focus on large-scale dynamics and efficient parameter estimation with the associated uncertainty, rather than directly utilizing a cost-function to fit the model41,42. Other modeling works in PD, for example in the case of the Virtual Deep brain stimulation, took a multi-scale simulation approach in order to simulate the effects of deep brain stimulation43,44. However, the scope of our model is different, as we provide an explicit account of the concentrations of Dopamine, which brings us closer to pathophysiological mechanisms45. In other words, our model explicitly encapsulates physiological knowledge about the functioning of dopamine and its effects on neural activities. Finally, our model aims to describe the whole brain, unlike previous works which represented the cortex as a single node. In conclusion, our work analyses EEG/LFP data from PD patients in the ON and the OFF states focusing on the aperiodic bursts, and leverages a newly designed mechanistic model that explicitly includes dopamine dynamics. However, the ability of the model to generate personalized predictions was tested on 10 patients. Larger cohorts will need to be tested to assess the deployability of this approach to scale. Finally, the main purpose of this work is to give a long-term vision to develop, in the future, a clinically meaningful framework that supports therapeutic decision-making through virtual patient modeling. Although this study focuses on validating a generic computational model, future steps will aim to increase personalization by integrating individual structural and functional data. This will enable us to construct digital twins that better capture patient-specific neurophysiological dynamics. Such personalization would be particularly valuable in clinical settings. For example, it might help clinicians adjust L-DOPA dosage. Given the narrow therapeutic window and the potential for serious side effects, such as motor fluctuations and dyskinesias, a model-informed tool could help optimize treatment while minimizing adverse effects. It will be relevant to check the ability of the model to predict clinical outcomes in patients with severe dyskinesias or those undergoing neurosurgical interventions (i.e., Deep Brain Stimulation). Future work will explore extending the model to incorporate DBS-related parameters and responses, as well as developing real-time inference capabilities for clinical use.

Materials and methods

Participants, EEG data acquisition and processing

We collected resting-state data from 10 patients with Parkinson’s disease and monitored both ON and OFF levodopa medication9. Each session was 2-min long, employing deep stimulation electrodes and EEG electrodes strategically placed in the motor areas on both sides. This setup enabled simultaneous recordings from both the subthalamic nuclei (STN) and the motor cortex. Specifically, the data includes time series from 14 channels: eight local field potential (LFP) contacts (L1, L2, L3, L4, R1, R2, R3, R4) that map to the left and right STN complemented by six EEG channels (F3, Fz, F4, C3, C4, Cz). Ethics committee IRB of Comite de Protection des Personnes CPP Sud Mediterranee gave ethical approval for this work. The registration number is RCB 2009-A00913-54. Patient consent has been obtained, and the appropriate institutional forms have been archived.

Signal preprocessing was performed using the Fieldtrip toolbox46. The continuous EEG signal was first high-pass filtered at 1.3 Hz with a Hamming window, using a “two-pass” direction, and a Butterworth filter type. Subsequently, it was down-sampled to 512 Hz and epoched into 4-second epochs. The signal underwent visual inspection to remove noisy epochs47.

Tractography data

Minimally preprocess diffusion and structural MRI data from 10 subjects of the human connectome project48,49 is used to calculate the structural connectomes. The diffusion imaging data is processed with the MRtrix3 toolbox50. Multi-shell multi-tissue constrained spherical deconvolution with group averaged response function51 is used to estimate fiber orientation distributions per voxel. After intensity inhomogeneity correction52, we use probabilistic tractography with anatomical constraint53 to generate 5 million tracts per subject. Tracts are weighed using the SIFT2 algorithm54. We use the multimodal registration method as implemented in the Lead DBS toolbox55 to transform the subcortical structures (GPe, GPi, STN and RN) of the DISTAL atlas56 into the subject space. The subcortical regions together with the cortical Desikan parcellation57 serve as the mask to group weighted tracts and create the structural connectome. To compute the lead field matrix we process the MNI152 template head with the Freesurfer recon-all58 pipeline to obtain the cortical, as well as the 3 boundary element model (BEM) surfaces (inner skull, outer skull, and outer skin surface). We use the MNE toolbox59 to fit a standard 10–20 EEG cap onto the skin surface of the MNI152 template head by manually setting the fiducial points (right and left pre-auricular point and nasion). Vertices of the cortical surface are used as neural electric dipoles. Together with the EEG locations and the BEM surfaces, we compute the electric forward problem using the OpenMEEG toolbox59.

Dody model for whole brain simulation

In our study, we employ the Dody model introduced here10. Initially implemented to simulate the dynamics of a single node, it has been extended to simulate the whole brain activity. The model is based on neural masses designed from the adaptive quadratic integrate-and-fire model, thence incorporating neuromodulatory dynamics into its differential equations which are:

where r, V and u represent respectively the firing rate, mean membrane potential and adaptation variable of each region. Sa and Sg describe the synaptic activation dynamics of excitatory AMPA and inhibitory GABA receptors, modeled as conductance-based synapses with maximal conductances ga and reversal potential Ea, and inhibitory GABA receptors of maximal conductance gg and reversal potential Eg. Sja and Sjg are the post-synaptic strengths of these inputs; Ja is the strength of the local recurring connections. To simulate dopamine dynamics, which is relevant in the context of Parkinson’s disease, Eq. (6), constitutes of two terms, the first corresponding to the afferent dopaminergic input and the second to the reuptake mechanisms described with Michaelis–Menten formalism, is added to the system, as: We focus our attention on the terms cexc, cinh, and cdopa, which are involved in Eqs. (4), (5) and (6), respectively. The connection-specific terms cexc, cinh, cdopa are informed by anatomical data from scientific literature, understanding each brain connection as either excitatory, inhibitory, or dopaminergic. The main diagonal of each of these terms represents local connectivity, while the off-diagonal elements represent long-range connectivities. The terms are modulated by a parameter g* through the following relations:

where g*;i,j is the connectome weights between the regions i and j, and rj is the firing rate of the j-th region projecting to the i-th region.

In particular, cortical connections have been considered excitatory. The cortex-basal ganglia-thalamic loop has been modeled taking into account the direct, indirect, and hyperdirect pathways60, as reported in Supplementary Fig. 1. The simulations were run for 30 seconds by numerically integrating the system of equations, through the modified Heun method for stochastic differential equations61. The first second was discarded as a transient.

Estimation of avalanche transition matrices and data features

To explore the dynamics of brain activity, we analyze EEG data signals. Firstly, each signal amplitude is standardized using the z-score and then binarized, such that any time point exceeding a threshold of two standard deviations (∣z∣ = 2) was marked as 1 (active), and all others as 0 (inactive) to compute avalanche transition matrices as described in this work9,11.

During our analysis of EEG data and the estimation of neuronal transition matrices, a key focus is on evaluating the impact of levodopa medication on the features. We calculate an avalanche-specific transition matrix (ATM), where each element (i, j) represents the probability that region j is active at time t + 1, given that region i was active at time t. This relationship signifies the probability of sequential recruitment of any two regions by an avalanche. For each subject, we produce an average transition matrix by averaging edge-wise across all avalanches and then symmetrizing it. In our data analysis pipeline, we explore how avalanches propagate between different brain regions using ATMs. Specifically, we assess the ATMs under two different conditions for each patient: with levodopa medication (ON) and without it (OFF). This comparison sheds light on the dynamics of perturbations spreading between brain regions affected by different levels of dopaminergic stimulation. Comprehensive tests to validate the ATMs and computational details are reported in this previous work9. Simultaneously, avalanche transition matrices are calculated for synthetic data as well. Starting from the simulations, the firing rates of individual brain regions are translated to the positions of the six considered electrodes using the lead field matrix. Since the position of the deep electrodes is not available, they have been approximated directly as the z-scored activities, without projecting it through the lead field. At the end of the procedure, 8 signals are generated. Each signal is z-scored, and then, similarly to the procedure described above, active regions are identified to calculate the ATM as with the empirical data. However, this time we do not take the absolute value of the signals.

Model inversion and dopaminergic tone parameter inference

The Bayesian approach offers a principled way for making inference, predictions, and quantifying uncertainty in the decision-making process by integrating information from anatomical, clinical, and mathematical knowledge62. Parameter estimation within a Bayesian framework involves quantifying and propagating uncertainty through probability distributions placed on the parameters (the prior), which are updated with information provided by the data (the likelihood) to form the posterior distribution19,63. However, accurate and reliable Bayesian inference from noisy brain data is challenging due to the high dimensionality of the data, the complex effects of brain networks, and the non-linearity involved in spatio-temporal brain organization. In particular, the calculation of the likelihood function is typically intractable, rendering MCMC sampling inapplicable18. In this case, we can treat the virtual brain models as a stochastic simulator that generates synthetic data similar to the empirical data, enabling inferences to be made without requiring access to the likelihood function21,23.

Using this framework known as Simulation-based Inference (SBI21,23), the Dody model is treated as a stochastic simulator, that is the generative model necessary to conduct Bayesian inference on dopaminergic tone, which is informed by anatomical data, to predict the features extracted from observed EEG data. To accomplish this, we train a class of machine-learning generative models known as Normalizing Flows (NFs22) to learn the relationship between low-dimensional data features and the parameters of an approximated posterior distribution. NFs are a family of generative models that convert a simple base distribution (e.g., the prior) into any complex target distribution (e.g., the posterior), where both sampling and density evaluation can be efficient and exact64.

In more detail, our objective is to establish plausible probability distributions for the wdopa parameter in the Dody model, considering that the output distributions of our model should best explain a given set of experimental data features. Considering wdopa as the known parameter (1-dimensional) and a collection of n data observations, denoted by the variable yexpt. The dynamical system analysis (previously conducted) provides insight into the reasonable range of parameter values, allowing us to define initial (prior) probability distributions p(wdopa), as a uniform distribution truncated between [0.05, 5]. Using Bayes’ rule, the posterior distribution of the parameter values given the data is defined by the following equation:

where \(p({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}})\) denotes the prior placed on wdopa, and the likelihood p(yexpt∣wdopa) is the probability of our model generating the data features yexpt given the parameter wdopa, and p(wdopa∣yexpt) represents the posterior distribution that we aim to estimate.

In this work, we use SNPE (Sequential Neural Posterior Estimation23), a tool enabling efficient and flexible simulation-based inference on complex models without requiring access to likelihoods. SNPE dynamically refines the proposals, network weights, and posterior estimates to learn how model parameters are related to the observed summary statistics of the data. We run SNPE using a single round to benefit from an amortized strategy (at the subject level), which can then be applied immediately to new data without needing to be retrained21. In this framework, we use Masked Autoregressive Flow (MAF22), which supports reversible nonlinear transformations and allows for highly expressive transformations with minimal computational cost.

To perform SNPE, three key inputs are required21,23:

-

1.

A prior distribution describing the biologically plausible values of wdopa, which modulates the dopaminergic tone influencing the ON and OFF states.

-

2.

A mechanistic model that simulates the large-scale neural activity associated with a specific value of wdopa.

-

3.

A set of low-dimensional yet sufficiently informative data features, focusing here on the EEG recordings.

We train the MAF using a budget of 3000 simulations with random parameters sampled from the prior. The set of data features extracted from source reconstructed EEG signals includes summary statistics of Avalanche Transition Matrices (ATM). From the ATMs, we compute the sum, arithmetic mean, skewness, kurtosis, the Coefficient of Variation (defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean, and its inverse), the Frobenius norm, and the entropy (H) of the matrix, defined as \(H=-\sum p{\log }_{2}p\) where \({\log }_{2}p\) is the base-2 logarithm of the probability distribution of signals. After training is complete, the posterior distribution for new observations or empirical data can be swiftly evaluated by performing a forward pass in the trained MAF. Notably, this process does not require the model or the data features to be differentiable. Each model simulation and posterior sampling took around 60 seconds and 30 seconds, respectively. All steps were performed on a Workstation DELL Precision 7820 Tower with 2 Intel Xeon Silver 4214R. To run SNPE, we used the public sbi toolbox20.

Before running SNPE on the empirical data, we first validate the approach using synthetic data generated with known ground truth values of dopaminergic tone, and with subject-specific structural connectomes to ascertain the accuracy of the wdopa estimations (see Fig. 5). The plot of z-score versus posterior shrinkage for the estimated posterior indicates an ideal Bayesian estimation for different values of wdopa.

Data features

To run SBI, we identify specific data features derived from synthetic EEG data, as follows: the sum and arithmetic mean of the ATM; the Skewness and Kurtosis (evaluating the asymmetry and tailedness of the ATM distribution around its mean value); the Coefficient of Variation and its inverse, which are defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean, providing a normalized measure of dispersion for the ATM elements. The Frobenius norm derives a scalar magnitude of the ATM. The Shannon entropy of the ATM is computed as \(H=-\sum p{\log }_{2}p\) where \({\log }_{2}p\) is the base-2 logarithm of the probability distribution of signals. For the training phase, the data features are smoothed using a moving average with a window size of 150. Subsequently, a linear regression is performed to obtain the value of the feature for each wdopa.

Evaluation of posterior fit

To evaluate the accuracy and reliability of the Bayesian inference using synthetic data, we compute the posterior z-score (denoted by z), against the posterior shrinkage (denoted by s):

where the z-score is defined as the absolute value of the difference between the estimated and true values of the parameters of interest (\({\tilde{w}}_{{\rm{dopa}}},{w}_{\text{dopa}\,}^{* }\) respectively) divided by the standard deviations of the posterior σpost, and the posterior shrinkage is given by 1 minus the ratio of the variance of the posterior \({\sigma }_{\,\text{post}\,}^{2}\) to the variance of the prior \({\sigma }_{\,\text{prior}\,}^{2}\).

The z-score measures how much the posterior distribution is centered around the true value, whereas the shrinkage quantifies the reduction of uncertainty over the estimate around the true value of the posterior distribution concerning the initial prior distribution. Ideally, the distribution of posteriors derived from prior predictive observations should converge towards small z-score and large posteriors’ shrinkage for each parameter component. By plotting the posterior z-score (y-axis) against the posterior shrinkage (x-axis), a concentration towards the lower right suggests an ideal Bayesian estimation19,65.

To study the correlation between the simulated data and the clinical improvement, we first compute the distance between the ATMs simulated in the ON and the OFF states, defined as 1 minus the absolute value of the mean of the edge-wise differences. This is correlated, across subjects, to the difference in the UPDRS scores in the ON and the OFF states. The result was validated utilizing a null distribution obtained by shuffling the averages of the differences between matrices.

As explained, we compared the ON-OFF differences in the synthetic and empirical data for each subject to compare the model’s performance to effectively capture the differences in the time series. To compare the data we proceed as follows: 1) compute the power spectra of the signals; 2) subtract (frequency-band wise) the power spectra of the signal in ON from the empirical STN in OFF, and subtract the power spectra of the simulated STN in ON from the empirical STN in OFF (i.e. with the simulations performed with the inferred Dopaminergic tone given the data from either the ON and OFF acquisitions); 3) correlate the differences across frequency bins. To validate the correlation, we then randomize the power spectra by shuffling the frequency bins, to estimate a null distribution of the correlations given by chance, and use this null distribution to estimate the goodness of fit of our data.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed in this study can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, conditional to the approval by the Ethics committee IRB of Comite de Protection des Personnes CPP Sud Mediterranee.

Code availability

The codes implemented are available at https://github.com/marangiol/The-Virtual-Parkinsonian-Patient.git.

References

Ascherio, A. & Schwarzschild, M. A. The epidemiology of parkinson’s disease: risk factors and prevention. Lancet Neurol. 15, 1257–1272 (2016).

Dauer, W. & Przedborski, S. Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron 39, 889–909 (2003).

Horn, A. et al. Connectivity predicts deep brain stimulation outcome in parkinson disease. Ann. Neurol. 82, 67–78 (2017).

Merk, T. et al. Electrocorticography is superior to subthalamic local field potentials for movement decoding in parkinson’s disease. eLife 11, e75126 (2022).

Chaudhuri, K. R. & Schapira, A. H. Non-motor symptoms of parkinson’s disease: dopaminergic pathophysiology and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 8, 464–474 (2009).

Tessitore, A., Cirillo, M. & De Micco, R. Functional connectivity signatures of parkinson’s disease. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 9, 637–652 (2019).

Filippi, M., Sarasso, E. & Agosta, F. Resting-state functional mri in parkinsonian syndromes. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 6, 104–117 (2019).

Sorrentino, P. et al. Flexible brain dynamics underpins complex behaviours as observed in parkinson’s disease. Sci. Rep. 11, 4051 (2021).

Agouram, H. et al. L-dopa induced changes in aperiodic bursts dynamics relate to individual clinical improvement in parkinson’s disease. Preprint at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.06.14.24308683v1 (2024).

Depannemaecker, D. et al. A next generation neural mass model with neuromodulation. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.06.23.600260v2.abstract (2024).

Sorrentino, P. et al. The structural connectome constrains fast brain dynamics. eLife 10, e67400 (2021).

Duma, G. M. et al. Altered spreading of neuronal avalanches in temporal lobe epilepsy relates to cognitive performance: A resting-state hdeeg study. Epilepsia 64, 1278–1288 (2023).

Romano, A. et al. Topological changes of fast large-scale brain dynamics in mild cognitive impairment predict early memory impairment: a resting-state, source reconstructed, magnetoencephalography study. Neurobiol. Aging 132, 36–46 (2023).

Corsi, M.-C. et al. Measuring neuronal avalanches to inform brain-computer interfaces. iScience 27, 108734 (2024).

Johnson, K. A. & Goody, R. S. The original michaelis constant: Translation of the 1913 michaelis-menten paper. Biochemistry 50, 8264–8269 (2011).

Kringelbach, M. L. et al. Dynamic coupling of whole-brain neuronal and neurotransmitter systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 9566–9576 (2020).

Bullmore, E. & Sporns, O. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 186–198 (2009).

Cranmer, K., Brehmer, J. & Louppe, G. The frontier of simulation-based inference. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 30055–30062 (2020).

Hashemi, M. et al. The bayesian virtual epileptic patient: A probabilistic framework designed to infer the spatial map of epileptogenicity in a personalized large-scale brain model of epilepsy spread. NeuroImage 217, 116839 (2020).

Tejero-Cantero, A. et al. sbi: A toolkit for simulation-based inference. J. Open Source Softw. 5, 2505 (2020).

Hashemi, M. et al. Amortized bayesian inference on generative dynamical network models of epilepsy using deep neural density estimators. Neural Netw. 163, 178–194 (2023).

Papamakarios, G., Pavlakou, T. & Murray, I. Masked autoregressive flow for density estimation. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2338–2347 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017).

Gonçalves, P. J. et al. Training deep neural density estimators to identify mechanistic models of neural dynamics. eLife 9, e56261 (2020).

Ross, L. N. & Bassett, D. S. Causation in neuroscience: keeping mechanism meaningful. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 25, 81–90 (2024).

Chen, L. & Campbell, S. A. Exact mean-field models for spiking neural networks with adaptation. J. Comput. Neurosci. 50, 445–469 (2022).

Braun, U. et al. From maps to multi-dimensional network mechanisms of mental disorders. Neuron 97, 14–31 (2018).

Stephan, K. E., Iglesias, S., Heinzle, J. & Diaconescu, A. O. Translational perspectives for computational neuroimaging. Neuron 87, 716–732 (2015).

Van Essen, D. C. & Glasser, M. F. The human connectome project: Progress and prospects. Cerebrum Dana Forum Brain Sci2016 (2016).

Braak, H., Ghebremedhin, E., Rüb, U., Bratzke, H. & Del Tredici, K. Stages in the development of parkinson’s disease-related pathology. Cell Tissue Res. 318, 121–134 (2004).

Wang, H. E. et al. Virtual brain twins: from basic neuroscience to clinical use. National Science Review11 (2024).

Sorrentino, P. et al. Brain fingerprint is based on the aperiodic, scale-free, neuronal activity. NeuroImage 277, 120260 (2023).

Yu, Y. et al. Parkinsonism alters beta burst dynamics across the basal ganglia-motor cortical network. J. Neurosci. 41, 2274–2286 (2021).

Tinkhauser, G. et al. Beta burst dynamics in parkinson’s disease off and on dopaminergic medication. Brain A J. Neurol. 140, 2968–2981 (2017).

Lofredi, R. et al. Subthalamic beta bursts correlate with dopamine-dependent motor symptoms in 106 parkinson’s patients. NPJ Parkinsons. Dis. 9, 1–9 (2023).

Pauls, K. A. M. et al. Cortical beta burst dynamics are altered in parkinson’s disease but normalized by deep brain stimulation. NeuroImage 257, 119308 (2022).

Vinding, M. C. et al. Reduction of spontaneous cortical beta bursts in parkinson’s disease is linked to symptom severity. Brain Commun. 2, fcaa052 (2020).

Scarpetta, S. et al. Criticality of neuronal avalanches in human sleep and their relationship with sleep macro- and micro-architecture. iScience 26, 107840 (2023).

Betancourt, M. Calibrating model-based inferences and decisions. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1803.08393 (2018).

Pavlides, A., Hogan, S. J. & Bogacz, R. Computational models describing possible mechanisms for generation of excessive beta oscillations in parkinson’s disease. PLoS Computational Biol. 11, e1004609 (2015).

Oswal, A. et al. Neural signatures of hyperdirect pathway activity in parkinson’s disease. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–15 (2021).

Deco, G. et al. Resting-state functional connectivity emerges from structurally and dynamically shaped slow linear fluctuations. J. Neurosci. 33, 11239–11252 (2013).

Kong, X. et al. Sensory-motor cortices shape functional connectivity dynamics in the human brain. Nat. Commun. 12, 6373 (2021).

Meier, J. M. et al. Virtual deep brain stimulation: Multiscale co-simulation of a spiking basal ganglia model and a whole-brain mean-field model with the virtual brain. Exp. Neurol. 354, 114111 (2022).

Saenger, V. M. et al. Uncovering the underlying mechanisms and whole-brain dynamics of deep brain stimulation for parkinson’s disease. Sci. Rep. 7, 9882 (2017).

Humphries, M. D., Obeso, J. A. & Dreyer, J. K. Insights into parkinson’s disease from computational models of the basal ganglia. J. Neurol., Neurosurg. Psychiatry 89, 1181–1188 (2018).

Oostenveld, R., Fries, P., Maris, E. & Schoffelen, J.-M. Fieldtrip: Open source software for advanced analysis of meg, eeg, and invasive electrophysiological data. Computational Intell. Neurosci. 2011, 1 (2011).

Niso, G. et al. Good scientific practice in eeg and meg research: Progress and perspectives. NeuroImage 257, 119056 (2022).

Van Essen, D. C. et al. The wu-minn human connectome project: an overview. NeuroImage 80, 62–79 (2013).

Glasser, M. F. et al. The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the human connectome project. NeuroImage 80, 105–124 (2013).

Tournier, J. et al. Mrtrix3: A fast, flexible and open software framework for medical image processing and visualisation. NeuroImage 202, 116137 (2019).

Jeurissen, B., Tournier, J., Dhollander, T., Connelly, A. & Sijbers, J. Multi-tissue constrained spherical deconvolution for improved analysis of multi-shell diffusion mri data. NeuroImage 103, 411–426 (2014).

Raffelt, D. et al. Bias field correction and intensity normalisation for quantitative analysis of apparent fibre density. Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 25, 3541 (2017).

Smith, R. E., Tournier, J., Calamante, F. & Connelly, A. Anatomically-constrained tractography: Improved diffusion mri streamlines tractography through effective use of anatomical information. NeuroImage 62, 1924–1938 (2012).

Smith, R. E., Tournier, J., Calamante, F. & Connelly, A. Sift2: Enabling dense quantitative assessment of brain white matter connectivity using streamlines tractography. NeuroImage 119, 338–351 (2015).

Horn, A. et al. Lead-dbs v2: Towards a comprehensive pipeline for deep brain stimulation imaging. NeuroImage 184, 293–316 (2019).

Ewert, S. et al. Toward defining deep brain stimulation targets in mni space: A subcortical atlas based on multimodal mri, histology and structural connectivity. NeuroImage 170, 271–282 (2018).

Desikan, R. S. et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on mri scans into gyral based regions of interest. NeuroImage 31, 968–980 (2006).

Fischl, B. Freesurfer. NeuroImage 62, 774–781 (2012).

Gramfort, A. et al. Meg and eeg data analysis with mne-python. Front. Neurosci. 7, 267 (2013).

DeLong, M. R. Primate models of movement disorders of basal ganglia origin. Trends Neurosci. 13, 281–285 (1990).

Hussain, A. S. Numerical solutions of stochastic differential equations by using heun’s method. Academic J. Nawroz Univ. 7, 208–215 (2018).

Gelman, A., Carlin, J. B., Stern, H. S. & Rubin, D. B. Bayesian Data Analysis (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 1995).

Van de Schoot, R. et al. Bayesian statistics and modelling. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 1, 1 (2021).

Kobyzev, I., Prince, S. J. & Brubaker, M. A. Normalizing flows: An introduction and review of current methods. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 43, 3964–3979 (2021).

Gelman, A. et al. Bayesian workflow. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.01808 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No. 101147319 (EBRAINS 2.0 Project) and No. 101137289 (Virtual Brain Twin Project) and “EBRAINS-Italy”. (European Brain ReseArch INfrastructureS-Italy) CUP B51E22000150006.This research has received funding from the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), M4C2. M.A. and L.C. wish to acknowledge the Italian National Group for Mathematical Physics, GNFM-INdAM.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and Methodology: M.A., D.D., M.H., P.S. Simulations and Data analysis: M.A., D.D., H.A., M.H., P.S. Formal analysis: M.A., D.D., M.H., P.S. Coding: M.A., M.W. Resources: J.R., R.C., A.E., V.J. Writing - Original Draft: M.A., P.S. Writing - Review - Editing: M.A., D.D., H.A., J.R., R.C., M.M., L.C., P.T., A.Z., A.E., V.J., P.S. Visualization: M.A., D.D., H.A., J.R., R.C., M.M., L.C., P.T., A.Z., A.E., V.J., P.S. Supervision and Project administration: D.D., V.J., P.S. Funding acquisition: V.J., P.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Author P.S. serves as Guest Editor of this journal and had no role in the peer-review or decision to publish this manuscript. He declares no financial competing interests. All other authors declare no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Angiolelli, M., Depannemaecker, D., Agouram, H. et al. The Virtual Parkinsonian patient. npj Syst Biol Appl 11, 40 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41540-025-00516-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41540-025-00516-y

This article is cited by

-

Virtual brain twins for stimulation in epilepsy

Nature Computational Science (2025)