Abstract

Toxoplasma gondii is a significant zoonotic pathogen of toxoplasmosis in humans and animals. Here a live attenuated Toxoplasma vaccine of WH3 Δrop18 was developed. The results showed that all mice vaccinated with WH3 Δrop18 were able to survive when challenge with various strains of Toxoplasma, including RH (type I), ME49 (type II), WH3 or WH6 (type Chinese 1). No cysts, if few, in the brain of the vaccinated animals were seen after challenge with cyst forming strains of ME49 or WH6. Vaccination with the WH3 Δrop18 triggered a strong immune response, including significantly increased level of the cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-12, TNF-α and IL-10) and the activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocytes and long term of specific antibodies against Toxoplasma. Our results strongly indicate that vaccine of WH3 Δrop18 might provide effective immune protection against a wide range strains of Toxoplasma infections and be a promising live attenuated vaccine candidate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii) is an opportunistic pathogenic and obligate nucleated intracellular parasite. With feline as its definitive host and a wide host population as its intermediate host, T. gondii can infect all warm-blooded animals and humans through multiple routes of transmission1. Toxoplasma affects almost 25% of the global population and the infection rate in some countries in Africa can be as high as 60%2. Most humans infected with T. gondii have no obvious clinical signs and symptoms, or only a transient and mild clinical presentation, but infection in immunocompromised patients (organ transplant recipients, cancer and AIDS patients) and pregnant women could lead to serious consequences3,4. Besides, T. gondii can cause abortions and stillbirths in domestic animals, especially goats and sheep, and therefore result in significant economic losses to the livestock industry5,6,7. In humans, the main therapeutic regimen consists of a combination of the antifolate drugs pyrimethamine and sulfasalazine, which has a high failure rate3,8,9. In addition, some other antiparasitic therapies have been utilized for the treatment of toxoplasmosis whereas toxicity and teratogenicity remain major challenges8,10. Thus, it is an urgent need for a more effective and safer prophylactic strategy for prevention of toxoplasmosis.

Due to the complex life cycle of T. gondii, there are multiple routes of transmission of infection in humans and animals11,12. It involves sexual reproduction in the feline intestine, which is the only definitive host13, and asexual reproduction and predation are also important routes of transmission of T. gondii between intermediate hosts3. Moreover, T. gondii has a variety of genotypes and can be classified into three types (I, II and III) in North America and Europe14,15,16, Among them, type I strains are represented by RH and GT1, type II by PRU and ME49, and type III by VEG and CTG. However, genotype Chinese 1 (ToxoDB#9) has been confirmed as the dominant type prevalent in East Asia, especially in China17,18. What is even more surprising is that strains of various genotypes could repeatedly infect the same hosts19. Despite relentless research in recent decades, therapeutic drugs and vaccine options for toxoplasmosis remain limited. Therefore, it is essential to develop an effective vaccine against toxoplasmosis to prevent infection with the Toxoplasma strains covering a wide range of genetic variants. This efficacious vaccine should be capable of eliciting concurrent and strong humoral and cellular immunity against several stages (cyst, tachyzoite as well as oocyst) in the parasite’s life cycle.

Over the past decades, many efforts have been made to develop vaccines against toxoplasmosis. A large number of candidates including inactivated tachyzoites20, DNA vaccines21, recombinant proteins22,23, nanoparticle-based vaccines24, mixed cocktail vaccines25, and live attenuated parasites26 have been studied in animal models and considerable progress has been obtained. Unfortunately, so far none of these candidates has been effective in blocking vertical transmission or eliminating tissue cysts27,28. Previous investigations indicated that live attenuated vaccine is most effective for eliciting immune protection because it mimics natural infection by providing a close micro-setting for antigen processing and presentation29,30,31. However, the strains of ME49 and PLK used in the studies for live attenuated vaccines still do not address the risk of tissue cysts formation. One commercial vaccine (Toxovax®) which has been put into use in sheep is derived from continuous subculture of S48 strain originally isolated from an aborted lamb30. Encouraged by the success of Toxovax®, researchers have turned to genetically modified parasites in order to design safer live vaccines. Fortunately, the widespread use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system has made it possible to perform gene editing and gene deletion of Toxoplasma to produce functionally live attenuated strains, which has the advantage of facilitating the development of vaccines with reduced virulence but retain their ability to have limited replication to induce host immunity28,32,33.

Secreted into host cells when the parasite invaded them, Toxoplasma effector rhoptry protein 18 (ROP18) is considered a critical virulence-associated molecule acting by facilitating intracellular proliferation of tachyzoites34,35. Additionally, ROP18 attenuates the immune response of the host, allowing the parasite to survive in the body and enhancing virulence36. WH3 strain, which belongs to genotype Chinese 1, is a representative strain of T. gondii circulating among animals and prevalent in humans in China17. Our previous study indicated that WH3 strain is highly virulent and does not form tissue cysts in animals and can be genetically modified for use as a live attenuated vaccine37.

In this study, we constructed the rop18-deficient strain (WH3 Δrop18) by CRISPR/Cas9 technology and found that the engineered parasite could dramatically reduce the virulence in mice. Most importantly, immunization of BALB/c mice with WH3 Δrop18 conferred strong resistance to acute and chronic toxoplasmosis by inducing cellular and humoral immunity.

Results

WH3 Δrop18 in the type Chinese 1 WH3 WT strain was successfully constructed by CRISPR/Cas9 technology

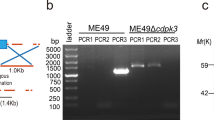

To investigate whether silencing of the effector molecule ROP18 in WH3 WT strain is valid against T. gondii infection as a live attenuated vaccine, we used CRISPR/Cas9 to disable the expression of ROP18 by inserting pyrimethamine-resistant DHFR-TS* (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1) followed by PCR and Western blotting identification of individual clones. PCR confirmed that the DHFR coding sequence had been successfully inserted into the target site (Fig. 1b). Western blotting results showed that WH3 Δrop18 strain did not express ROP18 protein (Fig. 1c). The plaque assay exhibited a less substantial plaque after WH3 Δrop18 parasite infection compared to WH3 WT strain (Fig. 2a, b). Giemsa staining revealed a greatly reduced number of parasites per PV in WH3 Δrop18-infected HFF cells compared to WH3 WT-infected cells (Fig. 2d).

a Schematic illustration of the CRISPR/Cas9 strategy to inactivate ROP18 by insertion of a pyrimethamine-resistant DHFR (DHFR-TS*), and PCR characterization of individual clones. b WH3 Δrop18 strain identified by PCR. G stands for GRA1 promoter positive control. 1 represents the PCR 1 fragment, 2 represents the PCR 2 fragment, and 3 represents the PCR 3 fragment. PCR 1 and PCR 2 detected the integration of DHFR-TS* with the corresponding genes, and PCR 3 detected whether the ROP18 sequence was successfully disrupted. WH3 WT strain served as the control. c Western blotting identification of ROP18 expression in WH3 WT and WH3 Δrop18 strains. PRF served as internal control.

a Comparison of WH3 WT and WH3 Δrop18 parasite growth in Plaque assay. b Number of the plaques (n = 4), ***P < 0.001. c Size of the plaques (n = 4), ns not significant. d A total of 50 PVs were examined to determine the number of vacuoles containing <8, = 8, or >8 parasites. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of triplicate samples. Two-way ANOVA was used for statistical analyses. Statistical differences are expressed as *P < 0.05 (n = 5). e Survival rate of BALB/c mice infected with the dose of 103/104/105/106 tachyzoites (WH3 WT or WH3 Δrop18 strains) for 35 days (n = 10) (The survival curves of BALB/c mice infected with 103/104/105/106 WH3 Δrop18 strains overlap). Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon tests.

Virulence of WH3 Δrop18 was severely attenuated in Mice

To evaluate the virulence of WH3 Δrop18, 103, 104, 105, and 106 tachyzoites of the WH3 WT or the WH3 Δrop18 were injected intraperitoneally into BALB/c mice, respectively, and the survival rate of the animals was observed for 35 days. Virulence examination showed that the WH3 WT strain caused 100% mortality while all of the WH3 Δrop18 tachyzoites infected mice survived, even at dose of 106 tachyzoites infection each mouse, indicating that the virulence of the WH3 Δrop18 was remarkably attenuated (Fig. 2e). Tissue samples of brain, liver, spleen, heart, lung, intestine and blood were collected on 7 dpi for evaluation of parasite burden. Brain, heart, liver, blood, and peritoneal lavage fluids of mice infected with 103 WH3 Δrop18 tachyzoites were collected at 3, 5, 7, 14, 21 dpi. The results showed that infection with WH3 Δrop18 strain significantly reduced the parasite loads of tissues compared with WH3 WT strain, and parasite-derived DNAs were undetectable in tissues by day 21 (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1, 6). We detected the tachyzoites in the peritoneal lavage fluids of vaccinated animals and no parasites were found by Giemsa staining at day 7 post-immunization (Supplementary Fig. 5). To assess the WH3 Δrop18 as a potential vaccine, we infected mice with the WH3 WT or WH3 Δrop18 using doses of 103, 104, 105 and 106, respectively, and clinical signs were recorded for 35 days. The observations revealed that all of the mice infected with WH3 Δrop18 at above-mentioned doses showed no obvious clinical manifestations, whereas those infected with WH3 WT strain presented severe clinical signs and all animals died on 11 dpi (Supplementary Fig. 2). Meanwhile, we collected sera from the mice infected with different doses of tachyzoites on 35 dpi for detection of expression of Toxoplasma-specific total IgG and subtype IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies, and found that the mice with WH3 Δrop18 infection in the doses of 103, 104, 105 or 106 presented significantly elevated production of total IgG and subtypes of IgG1 and IgG2a (Supplementary Fig. 3). These results indicate that different doses of tachyzoites have similar immunogenicity and 103 WH3 Δrop18 tachyzoites would be optimal and effective.

a Schematic of the experimental procedure. b–e After 7 days of infection with 1×103 WH3 Δrop18 or 1×106 WH3 Δrop18 parasites, the parasite burden in the brain, liver, spleen, heart, lungs, intestine and blood was measured by quantitative PCR (q-PCR). WH3 WT strain served as the control (n = 5). Unpaired t-tests were used for statistical analysis. Bars = mean ± SEM, ***P < 0.001.

WH3 Δrop18 vaccination induced humoral and cellular immune responses of mice to T. gondii

To assess the cell-mediated immunity of animals, we investigated the BALB/c mice immunized with WH3 Δrop18 for 125 days in a dose of 103 tachyzoites, serum samples obtained on 30, 75, and 125 days post-vaccination (dpv) were examined by ELISA for IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-12p70 and IL-10 (Fig. 4b–e). The results revealed that pro-inflammatory cytokines of IL-12p70, IFN-γ and TNF-α were significantly elevated in the sera of mice vaccinated with WH3 Δrop18 at 30 and 75 dpv when compared with those in the control. Cytokine level, however, was lower at 75 dpv than that at 30 dpv. At 125 dpv, the levels of IFN-γ, IL-12p70 in vaccinated mice remained higher than those in unvaccinated mice. Additionally, production of total IgG and IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies increased in the sera of vaccinated mice at 30, 75 and 125 dpv compared to the control (Fig. 4f). These results suggest that vaccination with WH3 Δrop18 induced a strong Th1 and Th2 immune response in mice and lasted for at least 125 days. To evaluate the immune memory following inoculation, splenocytes were collected from WH3 Δrop18 immunized mice at 75 dpv, and cultured in 24-well plates in vitro and stimulated with the soluble antigen (TSA) of WH3 WT. After 72 h or 96 h, culture supernatants were used to detect cytokines by ELISA. It was found that the levels of cytokines IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-12p70 and IL-10 were significantly higher in WH3 Δrop18 vaccinated mice than those in the control (Fig. 5f). Furthermore, we examined the percentages of CD3+CD4+T cells and CD3+CD8+ T cells and IFN-γ (CD4+IFN-γ+) in splenocytes using FCM after WH3 Δrop18 vaccination (Fig. 5b, c). It was noted that the percentages of CD3+ CD8+ T cells and CD3+CD4+T cells were remarkably elevated in WH3 Δrop18-vaccinated mice compared with the unvaccinated mice. Consistent with the increase of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells, the expression of IFN-γ was synchronously elevated in the splenocytes of WH3 Δrop18-vaccinated mice. Thus, these data indicate that immunity against T. gondii induced by WH3 Δrop18 vaccination is attributive to both cellular and humoral immune responses.

Detection of cytokines and T. gondii-specific IgG level in the sera of mice at 30/75/125 dpv with WH3 Δrop18 by ELISA test. a Strategy diagram of the experimental process. b IFN-γ, c IL-12p70, d TNF-α, e IL-10 (n = 5) and f Toxoplasma-specific total IgG and IgG1 and IgG2a (n = 8). Serum was derived from unvaccinated mice as a negative control. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, ns not significant.

a Schematic illustration of the experimental procedure. b, d Percentage of CD3+ CD8+ T cells and CD3+ CD4+ T cells detected with FCM (n = 4). c, e Increased percentage of Th1 (CD4+IFN-γ+) cell population in the mouse spleens following WH3 Δrop18 immunization compared to the control (n = 4). f Spleen cells cultured in vitro were stimulated with 10 µg/mL WH3 WT soluble antigens. Subsequently, the levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-12p70 and IL-10 in the splenic cell culture supernatant were detected by ELISA (n = 5). Unpaired t-tests were used for statistical analysis. Bars = mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

WH3 Δrop18 vaccination is effective in mouse protection from acute infection of T. gondii tachyzoites with various genotypes

To evaluate the immunogenicity of WH3 Δrop18 and its induced immune memory in Toxoplasma infection, mice were vaccinated with 1 × 103 WH3 Δrop18 tachyzoites by i.p. (Figs. 6a and 7a) and at 75 dpv, were challenged with 1 × 103 WH3 WT or 1 × 105 WH6 tachyzoites. Additionally, the immunized mice were challenged with 1 × 103 RH or 1 × 105 ME49 tachyzoites intraperitoneally on 125 dpv and observed for 35 days to test the long-term immunoprotection generated by WH3 Δrop18. We noted that, a hundred percent of the immunized mice survived the challenge of low virulent WH6 or ME49 tachyzoites as well as the virulent WH3 WT or RH tachyzoites, comparatively, all of the unvaccinated mice died within 8 or 11 days after infection with the virulent 103 RH or 103 WH3 WT tachyzoites (Figs. 6b and 7b) and 90% unvaccinated mice died when infected with less virulent WH6 or ME49 tachyzoites (Figs. 6c and 7c). Next, to investigate the reason for the efficient protection of mice with acute infection, we collected the sera and peritoneal fluids of mice after 7 days of challenge and Toxoplasma B1 gene amplification was performed. The results showed that the vaccinated animals had significant reduction of parasite loads when compared with the control (Figs. 6d and 7d), suggesting that the WH3 Δrop18 live attenuated tachyzoites elicited persistent and strong protection of animals from both virulent and less virulent strain infection of the parasite.

103 WH3 Δrop18 parasites were i.p. into BALB/c mice for 75 days as a vaccine dose. Then, the mice were challenged with 103 WH3 WT or 105 WH6 tachyzoites. Unvaccinated mice were treated similarly. a Schematic illustration of the study design. b The vaccinated mice were challenged with 103 WH3 WT tachyzoites or c 105 WH6 tachyzoites. The survival rate was recorded for 35 days (n = 10). Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon tests. d WH3 WT or WH6 tachyzoites were used for challenges of vaccinated mice, and 7 days later, the parasite burden in ascites were tested by qPCR (n = 5). ***P < 0.001. e IFN-γ, IL-12p70, TNF-α and IL-10 in sera were tested by ELISA (n = 5), ***P < 0.001. f, g Toxoplasma-specific total IgG and subclasses of IgG1 and IgG2a in sera were tested by ELISA. Unpaired t-tests were used for statistical analysis. Bars = mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001.

103 WH3 Δrop18 parasites were i.p. into BALB/c mice as a vaccine dose and observed for 125 days. Vaccinated or un-vaccinated mice were then infected with 103 RH or 105 ME49 parasites. a Schematic illustration of the study design. b 103 RH or c 105 ME49 tachyzoites were used for challenges (n = 10). The survival rate was recorded for 35 days. Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon tests. d RH or ME49 tachyzoites challenges in vaccinated mice, followed by detection of parasite burden by qPCR in the ascites of animals 7 days later (n = 5). ***P < 0.001. e IFN-γ, IL-12p70, TNF-α and IL-10 in sera were tested by ELISA (n = 5), ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01. f, g Toxoplasma-specific total IgG and subclasses of IgG1 and IgG2a in sera were tested by ELISA (n = 10). Unpaired t-tests were used for statistical analysis. Bars = mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001.

Moreover, sera from vaccinated mice challenged with WH3 WT, RH, WH6 or ME49 tachyzoites were used for detection of Toxoplasma-specific total IgG and IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies, and sera from vaccinated mice challenged with WH3 WT or RH tachyzoites were used to assay cytokines by ELISA. As a result, production of IFN-γ, IL-12p70, TNF-α and IL-10 were significantly decreased in the vaccinated mice compared to the unvaccinated mice (Figs. 6e and 7e). Contrarily, levels of Toxoplasma-specific total IgG and its subtypes of IgG1 and IgG2a were significantly elevated in the vaccinated groups (Fig. 6f, g) (Fig. 7f, g). These results demonstrated that vaccination with WH3 Δrop18 could induced a strong antibody-mediated immunity and dampened expression of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-12p70 and IL-10 in acute infection with T. gondii.

WH3 Δrop18 vaccination inhibited formation of cysts and prevent chronic infections

To evaluate the effect of WH3 Δrop18 on the protective immunity against chronic toxoplasmosis, we used the less virulent cyst-forming strain of ME49 and WH6 for challenge of the WH3 Δrop18 vaccinated mice. Mice vaccinated at 75 dpv were orally challenged with 30 cysts of ME49 or 50 cysts of WH6, respectively, and observed for 35 days (Fig. 8a). As shown in Fig. 8b and d, all of the WH3 Δrop18 immunized mice survived after 35 days, whereas the survival rates of unvaccinated mice, orally infected with ME49 or WH6 cysts, were 80% or 70%, respectively. Meanwhile, we evaluated the cyst loads in the brain tissues of survival mice and the results showed that the number of cysts in vaccinated mice was greatly reduced (25 ± 25/brain for ME49, 30 ± 30/brain for WH6) compared with that (700 ± 250/brain for ME49, 1600 ± 600/brain for WH6) in the control (Fig. 8c, e), indicating that WH3 Δrop18 vaccination is efficacious in inhibition of cyst formation during chronic infection.

a Schematic illustration of the experimental procedure. Seventy-five days after 1 × 103 WH3 Δrop18 vaccination, the mice were orally administered with 30 ME49 cysts or 50 WH6 cysts for the next test. Survival rate of vaccinated or unvaccinated mice infected with (b) 30 ME49 cysts or (d) 50 WH6 cysts at 35 dpi. (n = 10). Number of the cysts in brain tissues after 35 days of BALB/c mice oral infection with (c) 30 ME49 cysts or (e) 50 WH6 cysts (n = 6). Unpaired t-tests were used for statistical analysis. Bars = mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001.

Transfer of sera from WH3 Δrop18-vaccinated mice conveyed immunoprotection for the recipients

Toxoplasma-specific IgG antibodies consistently maintained at a high level in the sera of WH3 Δrop18 vaccinated mice. To assess the role of this antisera in limiting parasite duplication, we infected naive mice by i.p. of 103 WH3 WT or 105 WH6 tachyzoites, respectively, and sera collected from the immunized mice on 125 dpv were transferred to the infected animals on 0 and 3 dpi and naive mouse sera were used as a negative control. The protective effect of passive immunization was assessed by determining the parasite loads in the peritoneal fluids on 7 dpi and recording the survival rate for a duration of 35 days (Fig. 9a). The results (Fig. 9b, d) showed that, compared with the naive sera, mice transfused with the IgG positive sera of WH3 Δrop18-vaccinated animals gave rise to a significantly high survival, and remarkably reduced the parasite burden in the peritoneal fluids after challenge with the WH3 WT strain or with the WH6 strain. It suggests that the sera of vaccinated mice could retrain the parasite proliferation and have a partial protective effect on Toxoplasma infection.

a Schematic illustration of the study design. 103 WH3 WT or 105 WH6 tachyzoites challenged BALB/c mice. Positive (125 dpv) sera from WH3 Δrop18-inoculated mice were injected via tail vein into infected mice (n = 10) at 0 and 3 dpi. Peritoneal fluids were collected at 7 days after infection for parasite burden test by qPCR. Survival rate of BALB/c mice infected with (b) 103 WH3 WT or (d) 105 WH6 tachyzoites after 35 dpi. Parasite burdens after infection with (c) 103 WH3 WT or (e) 105 WH6 tachyzoites (n = 5). Unpaired t-tests were used for statistical analysis. Bars = mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Epidemiological and experimental research in the past decades demonstrated that vaccination holds the potential in controlling the ubiquitous Toxoplasma gondii pathogen, with live attenuated vaccines emerging as the most promising among all vaccination strategies attempted thus far. Toxovax®, derived from the S48 strain of T.gondii, is a live vaccine in current use and it can reduce Toxoplasma-associated abortions in sheep30. However, due to its toxicity during acute infection, it is not impossible that the live attenuated parasites may revert to acquire cyst or oocyst forming ability, and thus it is not widely used38. Inspired by Toxovax®, more scientists are focusing on genetically modified parasites, such as ME49 Δcdpk329 and ME49 Δldh39 and RH ΔompdcΔuprt40. Immunization of mice with these mutants provided partial protection against acute and chronic T. gondii infections, but there are still shortcomings. In this study, we explored the potential effect of WH3 Δrop18-deficient strain of Toxoplasma, which derived from the virulent strain of T. gondii type Chinese 1 and a predominant genotype circulating in animals and human in China, as a live attenuated vaccine on prevention of toxoplasmosis.

Undoubtedly, effectiveness and safety are the primary concerns for a vaccine which not only evokes efficient immunity against natural infections but leaves no latent infection behind in the host so as to eliminate the risk of potential dissemination, particularly for meat producing animals. Currently, mutants that inactivated CPSII or OMPDC grow well in vitro in the presence of additional uracil and fail to establish acute infection in animals41,42,43. Similarly, a live attenuated T. gondii mutants as vaccine with two lactate dehydrogenase gene deletions (Δldh) grow vigorously in vitro, but could not reproduce in vivo44. Previous report39 showed that the ME49 Δldh mutant might induce long-term protection to the challenge with less virulent strains of T. gondii types II and III, while short-term immunity to that with virulent type I RH strain. The other issue of concern is that ME49Δldh vaccination still produced a small amount of cysts in the tissues, which may become the risk of transmission of infection. A similar problem is seen in ME49 Δcdpk3 vaccine. In contrast, RH ΔompdcΔuprt strain was inactivated in vitro and mice inoculated with this mutant might provide one hundred percent of protection against RH Δku80, ME49 and WH6 strains. However, since RH ΔompdcΔuprt parasites were cleared by the host within one week after inoculation, animals needed to be vaccinated times with short intervals so as to obtain a long-term immunity, which may add workloads in large scale livestock farming. Here we explored the potential efficacy of WH3 Δrop18-deficient strain of Toxoplasma in development of vaccine. The results showed that WH3 Δrop18 induced a strong immunity to acute and chronic infection of various genotypes of Toxoplasmas tachyzoites.

It has been known the rhoptry protein 18 (ROP18) is the main molecule which is associated with virulence of Toxoplasma34,45. However, the virulence of type Chinese 1 WH3 strain falls between type I (RH) and type II (ME49)12,15 strains. Thus, it is worthwhile to investigate the ROP18 of type Chinese 1 (WH3 strain) and the potential role of ROP18 deficient mutant in induction of protective immunity. We found that WH3 Δrop18 lost its virulence in vitro and in vivo. BALB/c mice immunized with various doses of WH3 Δrop18 showed a 100% survival rate and remarkably ameliorated clinical signs at 35 dpi, even at a dose up to 106 tachyzoites. Comparably, all animals infected with WH3 WT strain died within 7 dpi (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 2). More importantly, the parasite-derived DNAs significantly decreased in the blood and tissues of brain, heart, lungs, spleen, intestine and liver on 7 dpi and even were undetectable in the blood, peritoneal lavage fluids, brain, heart and liver by day 21, and no cysts were seen in mice with WH3 Δrop18 vaccination (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figs. 1, 6). Our results suggest that WH3 Δrop18 might be a promising vaccine candidate which would not, to a large extent, leave the risk of latent infections and recurrence behind. We gave 103 WH3Δrop18 tachyzoites per mouse as appropriate dosage for vaccination and noted that all mice survived and parasite loads were significantly decreased in the peritoneal fluid after challenge with strains of WH3 WT, WH6, ME49, and RH as well (Figs. 6, 7). Noteworthily, all mice survived and few cysts, if any, (Fig. 8), were visualized in the brain tissues of vaccinated mice after oral lavage with 30 or 50 cysts of ME49 or WH6, respectively, when compared to the control. These results strongly suggests that the WH3 Δrop18 elicited a robust protective immunity in the animals to infection of virulent and avirulent strains of Toxoplasma.

To further explore the mechanism of the immunoprotective efficacy of the WH3 Δrop18, we measured the levels of antibodies and cytokines following immunization of mice and noted that T. gondii-specific IgG antibodies remained stably high and IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies dominated in the immunized mice compared to the control (Fig. 4f). Previous investigations indicate that Th1 immune response effectively prevents T. gondii infections46,47 whereas the Th2 immune response limits Toxoplasma-driven excessive inflammation29. In view of the importance of the pro-inflammatory cytokines in host immunity to T. gondii infection, we assessed production of IFN-γ, IL-12, TNF-α and IL-10 in the sera of the mice and found that level of these cytokines remained significantly high at 30 dpv, even at 125 dpv for IFN-γ and IL-12 (Fig. 4b-e), following WH3 Δrop18 vaccination compared with the control. This was also confirmed by the high expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines in splenocyte in vitro (Fig. 5f). It has been well-known that protective immunity of host to T. gondii infection is linked to innate and adaptive immunity and is mainly relying on Th1 cell-mediated immunity, which is driven by the production of high levels of IFN-γ and IL-12, and the IFN-γ plays a pivotal role in inhibiting parasite replication and killing the tachyzoites through multiple intracellular mechanisms12,48,49. We also noted a relatively increased level of IL-10, one of the regulatory cytokines in the immune settings. The explanation would be that IL-10 plays a role in dampening host injury due to increased inflammation50,51 since an effective protective immunity must first control parasite growth and, simultaneously, avoid tissue damage from excessive inflammation28. Additionally, our study showed that mouse vaccination with WH3 Δrop18 evoked a stably high level of T. gondii-specific IgG antibodies for at least 125 dpv, a relatively long time compared with the previous reports33,52, and passive transfer of the IgG antibodies to naïve animals may convey long-term protection against T. gondii infection (Fig. 9).

Cytotoxic activity of CD8+ T cells plays an important role in resistance to many intracellular pathogens53 including Toxoplasma infections by secreting IFN-γ and TNF-α as well as releasing cytotoxic particles47,54,55. In reality, CD8+ T cells not only control T. gondii infection but reduce the burden of intracerebral cysts in mice chronically infected with T. gondii54. Similarly, CD4+ T cells play an indispensable role in the defense against T. gondii infection by secreting IFN-γ, the main cytokine of the host immunity to T. gondii. In the present investigations, CD8+ T and CD4+ T lymphocytes were found to be activated and the expression of CD4+ IFN-γ+ was significantly increased in immunized mice tested by flow cytometry (Fig. 5b, c). The splenocytes and their produced IFN-γ as well as other pro-inflammatory cytokines are responsible for the cellular immune responses and effective clearance of secondary infections of immunized mice (Fig. 5f). However, although the research conducted on mice models has showcased the immense potential of these mutants as promising vaccine candidates, additional studies are imperative to ascertain the safety and efficacy of the WH3 Δrop18 vaccine in large animals including meat-producing domestic animals, with a particular focus on assessing their protection against oocyst shedding in cat.

In conclusion, Toxoplasma WH3 Δrop18 vaccine, generated from genotype Chinese 1 strain, could induce a high level of cellular and humoral immunity and provide a hundred percent of effective immunoprotection in mice to infection with the strains of a wide range of Toxoplasma genotypes and virulence. More importantly, vaccination of mice with WH3 Δrop18 did not leave the potential risk of latent infection behind and the number of cysts in the brain tissues were significantly reduced or even no cysts were found when challenged with the cyst-forming strains of ME49 or WH6, which enhanced the safety of the vaccine candidate.

Methods

Mice and parasites

All 6-8 week old female BALB/c mice were purchased from the Animal Centre of Anhui Medical University (AMU) and were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions with sterilized food and water. All processes followed the ethical standards formulated by the Scientific Ethics Committee of AMU (permit No: LLSC20200832). All experiments were performed after the mice had been acclimatized to the environment for one week. All mouse experiments were conducted under anesthesia, using 1-4% isoflurane in the induction chamber. After successful anesthesia, the mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation while still in a deep anesthetic state. T. gondii type Chinese 1 strains of WH3 WT, WH3 Δrop18, WH6, RH and ME49 strains used in the present study were propagated in human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) or Verda Reno (Vero) cell (purchased from ATCC, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, USA). Kunming mice were used to orally administer cysts to maintain T. gondii ME49 strain and WH6 strain bradyzoites.

Generation of the WH3 Δrop18 by CRISPR/Cas9

All the plasmids and primers used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Plasmids were transfected into WH3 tachyzoites by electrotransformation, followed by immediate culture in HFF cells. The parasites were screened with pyrimethamine for DHFR-TS* after culture for 48 h, obtaining individual clones by limited dilution. The individual clones were then verified by PCR and Western blotting. PCR reactions were performed using 1 µl of genomic DNA extracted from individual clones as template in a 25 µl reaction mixture using Taq DNA polymerase. Subsequently, the PCR products were detected by agarose gel electrophoresis. The monoclonal antibodies against ROP18 were prepared in the laboratory, while the anti-Profilin (PRF) antibodies were kindly donated by Prof. Long SJ at China Agricultural University.

Giemsa staining and plaque assays

The 5×105 fresh WH3 WT or WH3 Δrop18 parasites were inoculated into HFF cells and cultured in 24-well plates. Giemsa staining was performed after 48 h. The average number of parasites per parasitophorous vacuole (PV) was derived from counting 50 PVs in three replicate experiments. Freshly harvested WH3 WT or WH3 Δrop18 tachyzoites (1×104 tachyzoites) were added to 24-well plates with monolayers of Vero cells and left undisturbed in standard media. After 10 days of cultivation, the medium was removed and then the plates were rinsed with PBS for 3 times. The monolayers were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, and then stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 30 min at room temperature before rinsing with deionized water. The plates were scanned to analyze the number of plaques. The plaque size was calculated using ImageJ. All parasites underwent three replications.

Virulence assay of WH3 Δrop18 strain in mice

To assess the virulence of WH3 Δrop18 in BALB/c mice, we intraperitoneally injected (i.p.) fresh tachyzoites into 6-8 weeks old BALB/c mice (n = 10) at doses of 103, 104, 105, 106. Mice were observed daily for clinical signs such as hunching, piloerection, ptosis, sunken eyes, worm-seeking behavior, latency of movement, ataxia, touch reflexes, deficient evacuation and lying on belly. Clinical scores ranged from 0 to 10, indicating the absence of signs or the presence of all signs, respectively. The survival rate and clinical signs of infected mice were observed for 35 days, and blood was collected on day 35 to confirm infection using ELISA. Brain, liver, spleen, heart, lung, intestine tissues, and blood of mice infected with different doses of tachyzoites were collected at day 7 post-infection (dpi);Brain, heart, liver, blood and peritoneal lavage fluids were collected in mice infected with 103 tachyzoites at 3, 5, 7, 14, 21 dpi. The SteadyPure genomic DNA Kit was used to extract genomic DNA (AG Biotech, Hunan, China). Peritoneal lavage fluids were collected from mice infected with 103 tachyzoites on 3, 5, 7 dpi and the parasites were examined by Giemsa staining. Parasite burden was determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR). Simultaneously, WH3 WT strain was used as a control. TgB1 gene amplification by qPCR was conducted for assessment of parasite burden in all of the latter experiments.

Detection of T. gondii-specific IgG antibodies and cytokines after vaccination of BALB/c mice

BALB/c mice were inoculated with freshly harvested 1 × 103 WH3 Δrop18 tachyzoites or mock-vaccination in 200 µl PBS by i.p. Sera samples were collected to measure the level of total Toxoplasma-specific IgG and IgG subclasses including IgG1 and IgG2a by ELISA at 30, 75 and 125 dpi. Firstly, WH3 WT tachyzoites were subjected to ultrasonic fragmentation to obtain soluble antigens and then the 96-well ELISA plate were coated with 10 µg/ml soluble WH3 WT antigens and incubated overnight at 4 °C and washed three times with 0.05% Tween-20 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS-T), then blocked with 3% BSA and washed again. After that, collected sera samples were diluted in 1:50 and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The plate was then washed for six times with PBS-T, and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a (ProteinTech Group, Inc., USA) secondary antibodies were added to per well and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Finally, TMB (100 μl/well, Beyotime Biotechnology) and 2 M H2SO4 (Beyotime Biotechnology) were used to develop and stop the reaction and then measured at 450 nm optical density (OD). All samples were tested for 3 times. In the meantime, the expression levels of cytokines interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin 12p70 (IL-12p70), tumor necrosis factor TNF (TNF-α) and interleukin 10 (IL-10) were detected by using ELISA kits (ProteinTech Group, Inc., USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Mouse protection against acute and chronic infections by WH3 Δrop18 vaccination

BALB/c mice were immunized with 1 × 103 WH3 Δrop18 tachyzoites by i.p. and challenged on the day 75 post-immunization, with 1 × 103 WH3 WT tachyzoites, 1 × 105 WH6 tachyzoites by i.p., oral administration of 30 ME49 cysts or 50 WH6 cysts (n = 10), respectively. On the day 125 post-immunization, the mice were challenged with either 1 × 103 RH or 1 × 105 ME49 tachyzoites via i.p. (n = 10). The same dose and route of infection of unvaccinated mice served as controls (n = 10). All challenged mice were monitored for additional 35 days and then clinical signs and survival of the animals were recorded. On day 7 of challenge, sera were collected from the challenged mice to assay the level of cytokine production and Toxoplasma-specific total IgG and subclasses of IgG1and IgG2a by ELISA and parasite loads in ascites were determined (n = 5). Furthermore, the number of cysts in the brains of chronically infected survival mice was assessed on day 35 post-challenge (n = 6).

Detection of cytokine production in splenocytes

Spleens of mice were harvested after 75 days of vaccination to evaluate the level of cytokine production and the normal mice were taken as the control, then individual splenocyte suspensions were obtained by grinding and isolating splenocytes with a 70 μM wire mesh sieve and lysing in erythrocyte lytic buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology) for 5-10 min. Subsequently, splenocytes were cultured in 1640 medium with 10% FBS in 24-well plates and stimulated with 10 µg/mL of soluble Toxoplasma tachyzoite antigen (STAg) of the WH3 WT strain. Then the levels of TNF-α and IL-10 in the supernatants of the splenocytes were detected after 72 h of culture, and IL-12p70 and IFN-γ were measured after 96 h of culture.

Analysis of splenic lymphocytes by flow cytometry

Splenocytes were prepared according to the same method described above and then used to assay the percentage of CD4+ T lymphocytes and CD8+ T lymphocytes. Lymphocytes from the spleen were conditioned to the appropriate cell number (1 × 106/ml) and then suspended in 100 µl PBS. Cells were protected from light for 30 min at 4 °C with APC-CY7-labeled anti-mouse CD3 (BioLegend, United States), Percp-CY5.5-labeled anti-mouse CD8 (BioLegend, United States) and FITC-labeled anti-mouse CD4 (BD, United States), and then washed with the PBS. After washing, the cells were analyzed on FCM. For staining of the intracellular cytokine IFN-γ, we cultured splenic lymphocytes in 6-well plates with 2 ml of 10% FBS in 1640 medium and stimulated the cells with PMA (20 ng/ml) and ionomycin (1 mg/ml) for 4 h in the presence of BFA (1 mg/ml). And the cells were subsequently stained with FITC-labeled anti-mouse CD4, incubated at 4 °C for 30 min away from light, washed twice with PBS, and after surface staining, the cells were fixed with the Cytofix/ Cytoperm kit (BD, United States) away from light for 40 min at room temperature according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then washed twice, and stained for intracellular cytokines with APC-labeled anti-mouse IFN-γ (BD, United States). After washing with PBS, cells were analyzed on FCM.

Passive transfer with the sera of WH3 Δrop18-vaccinated mice

BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 × 103 WH3 WT tachyzoites or 1 × 105 WH6 tachyzoites. At the day 0 and 3 post-infection, the serum from WH3 Δrop18 vaccinated mice on day 125 post-vaccination or naive mice were injected via tail vein (100 μl/mouse). Naive sera were used as the negative control. Parasite loads in peritoneal fluid were determined by qPCR on day 7 post-infection, while survival rates lasting 35 days were recorded under passive immunization.

Statistical analysis

In this study, statistical significance was defined by using GraphPad Prism 8.0 and P < 0.05 was considered as significant. Survival comparison was performed using Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test. Unpaired t-test was performed for two-group comparisons. One-or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze differences between groups.

Data availability

The authors will provide the original data that underpins the conclusions of this article without undue retention.

References

Dubey, J. P. History of the discovery of the life cycle of toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasit. 39, 877–882 (2009).

Molan, A., Nosaka, K., Hunter, M. & Wang, W. Global status of toxoplasma gondii infection: systematic review and prevalence snapshots. Trop. Biomed. 36, 898–925 (2019).

Robert-Gangneux, F. & Darde, M. L. Epidemiology of and diagnostic strategies for toxoplasmosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 25, 264–296 (2012).

Hill, D. & Dubey, J. P. Toxoplasma gondii: transmission, diagnosis and prevention. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 8, 634–640 (2002).

Dubey, J. P. et al. Prevalence of viable toxoplasma gondii in beef, chicken, and pork from retail meat stores in the United States: risk assessment to consumers. J. Parasitol. 91, 1082–1093 (2005).

Dubey, J. P. Toxoplasmosis in pigs-the last 20 years. Vet. Parasitol. 164, 89–103 (2009).

Montoya, J. G. & Liesenfeld, O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 363, 1965–1976 (2004).

Alday, P. H. & Doggett, J. S. Drugs in development for toxoplasmosis: advances, challenges, and current status. Drug Des Devel Ther 11, 273–293 (2017).

Dunay, I. R., Gajurel, K., Dhakal, R., Liesenfeld, O. & Montoya, J. G. Treatment of toxoplasmosis: historical perspective, animal models, and current clinical practice. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31, e00057–17 (2018).

Zhang, N. Z., Chen, J., Wang, M., Petersen, E. & Zhu, X. Q. Vaccines against toxoplasma gondii: new developments and perspectives. Expert Rev. Vaccines 12, 1287–1299 (2013).

Dubey, J. P. Advances in the life cycle of toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasit. 28, 1019–1024 (1998).

Hunter, C. A. & Sibley, L. D. Modulation of innate immunity by toxoplasma gondii virulence effectors. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 766–778 (2012).

Vanwormer, E., Fritz, H., Shapiro, K., Mazet, J. A. & Conrad, P. A. Molecules to modeling: toxoplasma gondii oocysts at the human-animal-environment interface. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36, 217–231 (2013).

Howe, D. K. & Sibley, L. D. Toxoplasma gondii comprises three clonal lineages: correlation of parasite genotype with human disease. J. Infect. Dis. 172, 1561–1566 (1995).

Saeij, J. P., Boyle, J. P. & Boothroyd, J. C. Differences among the three major strains of toxoplasma gondii and their specific interactions with the infected host. Trends Parasitol 21, 476–481 (2005).

Sibley, L. D. & Boothroyd, J. C. Virulent strains of toxoplasma gondii comprise a single clonal lineage. Nature 359, 82–85 (1992).

Chen, Z. W. et al. Genotyping of toxoplasma gondii isolates from cats in different geographic regions of China. Vet. Parasitol. 183, 166–170 (2011).

Zhou, P. et al. Genetic characterization of toxoplasma gondii isolates from pigs in China. J. Parasitol. 96, 1027–1029 (2010).

Jensen, K. D. et al. Toxoplasma gondii superinfection and virulence during secondary infection correlate with the exact rop5/rop18 allelic combination. Mbio 6, e02280 (2015).

Zorgi, N. E., Costa, A., Galisteo, A. J., Do, N. N. & de Andrade, H. J. Humoral responses and immune protection in mice immunized with irradiated t. Gondii tachyzoites and challenged with three genetically distinct strains of t. Gondii. Immunol. Lett. 138, 187–196 (2011).

Wu, L. et al. A novel combined dna vaccine encoding toxoplasma gondii sag1 and rop18 provokes protective immunity against a lethal challenge in mice. Acta Parasitolog 66, 1387–1395 (2021).

Pinzan, C. F. et al. Vaccination with recombinant microneme proteins confers protection against experimental toxoplasmosis in mice. Plos One 10, e0143087 (2015).

Wu, M. et al. Vaccination with recombinant toxoplasma gondii cdpk3 induces protective immunity against experimental toxoplasmosis. Acta Trop 199, 105148 (2019).

Ducournau, C. et al. Synthetic parasites: a successful mucosal nanoparticle vaccine against toxoplasma congenital infection in mice. Future Microbiol 12, 393–405 (2017).

Liu, F. et al. Protective effect against toxoplasmosis in balb/c mice vaccinated with recombinant toxoplasma gondii mif, cdpk3, and 14-3-3 protein cocktail vaccine. Front. Immunol. 12, 755792 (2021).

Le Roux, D. et al. Evaluation of immunogenicity and protection of the mic1-3 knockout toxoplasma gondii live attenuated strain in the feline host. Vaccine 38, 1457–1466 (2020).

Loh, F. K., Nathan, S., Chow, S. C. & Fang, C. M. Vaccination challenges and strategies against long-lived toxoplasma gondii. Vaccine 37, 3989–4000 (2019).

Wang, J. L. et al. Advances in the development of anti-toxoplasma gondii vaccines: challenges, opportunities, and perspectives. Trends Parasitol 35, 239–253 (2019).

Wu, M. et al. Live-attenuated me49deltacdpk3 strain of toxoplasma gondii protects against acute and chronic toxoplasmosis. Npj Vaccines 7, 98 (2022).

Buxton, D. & Innes, E. A. A commercial vaccine for ovine toxoplasmosis. Parasitology 110, S11–S16 (1995).

Buxton, D., Thomson, K., Maley, S., Wright, S. & Bos, H. J. Vaccination of sheep with a live incomplete strain (s48) of toxoplasma gondii and their immunity to challenge when pregnant. Vet. Rec. 129, 89–93 (1991).

Shen, B., Brown, K., Long, S. & Sibley, L. D. Development of crispr/cas9 for efficient genome editing in toxoplasma gondii. Methods Mol Biol 1498, 79–103 (2017).

Li, J. et al. Plk: deltagra9 live attenuated strain induces protective immunity against acute and chronic toxoplasmosis. Front. Microbiol. 12, 619335 (2021).

Taylor, S. et al. A secreted serine-threonine kinase determines virulence in the eukaryotic pathogen toxoplasma gondii. Science 314, 1776–1780 (2006).

El, H. H. et al. Rop18 is a rhoptry kinase controlling the intracellular proliferation of toxoplasma gondii. Plos Pathog 3, e14 (2007).

Fentress, S. J. et al. Phosphorylation of immunity-related gtpases by a toxoplasma gondii-secreted kinase promotes macrophage survival and virulence. Cell Host Microbe 8, 484–495 (2010).

Li, M. et al. Phylogeny and virulence divergency analyses of toxoplasma gondii isolates from china. Parasites Vectors 7, 133 (2014).

Burrells, A. et al. Vaccination of pigs with the s48 strain of toxoplasma gondii-safer meat for human consumption. Vet. Res. 46, 47 (2015).

Xia, N. et al. A lactate fermentation mutant of toxoplasma stimulates protective immunity against acute and chronic toxoplasmosis. Front. Immunol. 9, 1814 (2018).

Shen, Y. et al. A live attenuated rhdeltaompdcdeltauprt mutant of toxoplasma gondii induces strong protective immunity against toxoplasmosis in mice and cats. Infect. Dis. Poverty 12, 60 (2023).

Fox, B. A. & Bzik, D. J. Avirulent uracil auxotrophs based on disruption of orotidine-5’-monophosphate decarboxylase elicit protective immunity to toxoplasma gondii. Infect. Immun. 78, 3744–3752 (2010).

Fox, B. A. & Bzik, D. J. De novo pyrimidine biosynthesis is required for virulence of toxoplasma gondii. Nature 415, 926–929 (2002).

Fox, B. A. & Bzik, D. J. Nonreplicating, cyst-defective type ii toxoplasma gondii vaccine strains stimulate protective immunity against acute and chronic infection. Infect. Immun. 83, 2148–2155 (2015).

Xia, N. et al. Functional analysis of toxoplasma lactate dehydrogenases suggests critical roles of lactate fermentation for parasite growth in vivo. Cell Microbiol. 20, (2018).

Saeij, J. P. et al. Polymorphic secreted kinases are key virulence factors in toxoplasmosis. Science 314, 1780–1783 (2006).

Lopez-Yglesias, A. H., Burger, E., Araujo, A., Martin, A. T. & Yarovinsky, F. T-bet-independent th1 response induces intestinal immunopathology during toxoplasma gondii infection. Mucosal Immunol 11, 921–931 (2018).

Dupont, C. D., Christian, D. A. & Hunter, C. A. Immune response and immunopathology during toxoplasmosis. Semin. Immunopathol. 34, 793–813 (2012).

Yarovinsky, F. Innate immunity to toxoplasma gondii infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 109–121 (2014).

Pittman, K. J. & Knoll, L. J. Long-term relationships: the complicated interplay between the host and the developmental stages of toxoplasma gondii during acute and chronic infections. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 79, 387–401 (2015).

Melchor, S. J. & Ewald, S. E. Disease tolerance in toxoplasma infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9, 185 (2019).

Gazzinelli, R. T. et al. In the absence of endogenous il-10, mice acutely infected with toxoplasma gondii succumb to a lethal immune response dependent on cd4+ t cells and accompanied by overproduction of il-12, ifn-gamma and tnf-alpha. J. Immunol. 157, 798–805 (1996).

Wang, J. L. et al. Immunization with toxoplasma gondii gra17 deletion mutant induces partial protection and survival in challenged mice. Front. Immunol. 8, 730 (2017).

Wong, P. & Pamer, E. G. Cd8 t cell responses to infectious pathogens. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 29–70 (2003).

Suzuki, Y. et al. Removal of toxoplasma gondii cysts from the brain by perforin-mediated activity of cd8+ t cells. Am. J. Pathol. 176, 1607–1613 (2010).

Denkers, E. Y. et al. Perforin-mediated cytolysis plays a limited role in host resistance to toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 159, 1903–1908 (1997).

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the members of our laboratory for their valuable comments during the experiments. This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.82072304 and No.81871671).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Y. and C.W.: conceived and designed the work. C.W., S.F., X.Y. and H.Z.: performed the experiments. F.Z., L.S., J.Z. and Y.Y.: collected and analyzed the data. C.W., J.D., Q.L. and J.S.: drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in discussing the results and then reviewing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Fu, S., Yu, X. et al. Toxoplasma WH3 Δrop18 acts as a live attenuated vaccine against acute and chronic toxoplasmosis. npj Vaccines 9, 197 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-00996-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-00996-9