Abstract

Pneumococcal infections are a serious health issue associated with increased morbidity and mortality. This systematic review evaluated the efficacy, effectiveness, immunogenicity, and safety of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV)15 compared to other pneumococcal vaccines or no vaccination in children and adults. We identified 20 randomized controlled trials (RCTs). A meta-analysis of six RCTs in infants showed that PCV15 was non-inferior compared with PCV13 for 12 shared serotypes. Based on a meta-analysis of seven RCTs in adults, PCV15 was non-inferior to PCV13 for 13 shared serotypes. For the unique PCV15 serotypes, 22F and 33F, immune responses were higher in infants and adults vaccinated with PCV15 compared to those receiving PCV13. Regarding safety, meta-analyses indicated comparable risks of adverse events between PCV15 and PCV13 in infants. Adults receiving PCV15 had a slightly higher risk of adverse events, though serious events were similar between groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae is responsible for causing respiratory infections and invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), which includes conditions such as bacteraemic pneumonia, sepsis and meningitis1. In Europe, the annual incidence of IPD was highest in adults aged 65 years or older (18.7 cases per 100,000) and in infants under one year of age (14.4 cases per 100,000)2. IPD is associated with morbidity and mortality, particularly affecting young children, older adults, individuals with chronic medical conditions, asplenia, or those living with immunosuppression1.

Two types of pneumococcal vaccines are currently authorised for use in the European Union: pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines (PPSVs). Pneumococcal vaccine recommendations and national immunisation schedules vary across European countries, particularly regarding differing recommendations for older age groups, high-risk populations, vaccine types, and dosing intervals3,4.

Pneumococcal vaccination can exert selection pressure on non-vaccine serotypes5. The childhood PCV programmes have not only changed the serotype distribution in countries but also between countries6,7. As a result, infections caused by non-vaccine serotypes have increased after the introduction of PCVs. This phenomenon, known as serotype replacement, represents a major challenge for the development of pneumococcal vaccines8, and manufacturers have strived to develop pneumococcal vaccines that protect against a broader range of serotypes9. These efforts have resulted in the approval of two new PCVs: the 15-valent PCV (PCV15, Vaxneuvance®, Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC)10 and the 20-valent PCV (PCV20, Prevenar 20®, Pfizer)11. Both vaccines received authorisation by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to investigate the efficacy, effectiveness, immunogenicity, and safety of PCV15 compared to no vaccination, placebo, or any other currently approved pneumococcal vaccine in children and adults.

Results

Literature search

Our literature search of databases and registries yielded 421 records. In addition, we identified 157 records through other methods. We included 22 publications12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 of 20 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in our review, contributing data on immunogenicity and safety outcomes. We did not identify any non-randomised studies of interventions (NRSIs). Fig. 1 illustrates the flow diagram of the study selection process. Supplementary Table 1 lists the studies excluded by full-text assessment, with the corresponding reasons for exclusion.

Characteristics of the included studies

Overall, the 20 identified phase 2 and 3 trials, published in 22 articles12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33, included 19,358 participants. Eight studies (10 publications) included only adults16,18,19,20,23,24,25,28,29,30, while 11 focused exclusively on infants, children, or adolescents12,13,14,15,17,21,22,26,27,31,32, and one study included both adults and children33. The study investigators randomised participants to either PCV15, PCV13, PPSV23, or a sequential combination of both PCV and PPSV23. None of the included studies compared PCV15 with PCV20, and none compared PCV15 with no vaccination or placebo. Most studies were multicentric studies conducted in countries across the world. All studies were funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC.

Supplementary Table 3 provides details of the study and patient characteristics. Supplementary Table 4 summarizes primary and secondary outcomes, Supplementary Table 5 the results for safety outcomes and Supplementary Table 6 the subgroup results from individual studies. The COE is provided in Supplementary Tables 7 and 8.

Risk of bias in the included studies

For the immunogenicity and safety outcomes, we assessed the risk of bias as low for 10 trials12,13,14,22,25,27,28,29,31,32 and as some concerns for 10 trials15,16,17,18,21,23,24,26,30,33. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the ratings for the individual domains for each RCT. The main reasons for rating the risk of bias with some concerns were inadequate reporting of the randomisation process and bias due to missing data.

Studies in infants, children, and adolescents

We identified 12 RCTs including 11,428 infants, children, or adolescents12,13,14,15,17,21,22,26,27,31,32,33, of which nine studies were on healthy infants, children, and adolescents12,13,14,15,17,21,22,26,31. Three studies included immunocompromised children27,32,33. Two studies were phase 2 trials17,26; the others were phase 3 trials12,13,14,15,21,22,27,31,32,33.

The number of participants in the included studies ranged from 14 to 2,409. The mean age of the trial participants at study entry ranged from 8.4 weeks to 12.7 years. The proportion of females ranged from 45.6% to 49.8%. The study populations included 2.8% to 88.3% non-white ethnic groups, depending on the countries where the study was conducted. The study by Suzuki et al. included only healthy Japanese infants31. Most studies were conducted in pneumococcal vaccine–naïve infants.

Six studies evaluated a 3 plus 1 vaccination schedule consisting of a primary infant series of 3 doses of PCV15 or PCV13 between the ages of 2 and 6 months, followed by a toddler dose at 12 to 15 months12,15,17,21,26,31. One trial compared PCV15 not only to PCV13 but also to a mixed PCV15/PCV13 regimen15. One study in infants investigated a 2 plus 1 vaccination schedule, with a primary series of two doses of PCV15 or PCV13 and an additional toddler dose14. In the study by Martinon-Torres et al., three or four PCV doses were given in total, depending on whether the infants were full-term (37 weeks or more) or pre-term (less than 37 weeks)22. In this study 6% of participants were pre-term infants. One trial evaluated three different catch-up schedules, with 1 dose, 2 or 3 doses administered, depending on the age of the children13.

Studies in immunocompromised children evaluated 1 dose of PCV15 or PCV1327 or 1 dose of PCV15 or PCV13 followed by 1 dose of PPSV23 after 8 weeks32. One study including both immunocompromised children and adults investigated a series of 3 PCV15 or PCV13 doses, followed by another PCV dose or a single dose of PPSV2333.

Efficacy and effectiveness

None of the included trials reported on patient-relevant health outcomes (incidence of pneumococcal infection–related death, IPD, pneumonia, pneumococcal infection–related hospitalisation, otitis media), duration of protection post-vaccination, or the proportion of patients colonised with Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Immunogenicity

In total, 11 trials provided data on immunogenicity in infants, children, or adolescents13,14,15,17,21,22,26,27,31,32,33.

PCV15 vs. PCV13

Healthy infants and children, pneumococcal vaccine–naïve

Based on Immunoglobulin G (IgG) geometric mean ratio (GMR) 30 days post-dose 3, a random-effects meta-analysis (7 Studies13,14,17,21,22,26,31, N ranged from 4807 to 5453 across serotypes, IgG GMR ranged from 0.53 to 1.63; I² ranged from 0% to 92%, Supplementary Fig. 2) yielded the non-inferiority of PCV15 compared with PCV13 for 12 shared serotypes, as indicated by the lower confidence limit of being above 0.5. Specifically, for the shared serotype 3 the lower confidence limit of IgG GMR was 1.38. For the serotype 6A, the lower confidence limit was 0.42.

Post-dose 4, a random-effects meta-analysis (5 Studies15,17,21,26,31, N ranged from 3138 to 3469 across serotypes, IgG GMR ranged from 0.64 to 1.49; I² ranged from 0% to 90%, Supplementary Fig. 3) rendered the non-inferiority of the PCV15 serotype-specific IgG GMR compared with PCV13 for all 13 shared serotypes. For the shared serotype 3 the lower confidence limit of IgG GMR was 1.22. Regarding the unique PCV15 serotypes 22F and 33F, IgG geometric mean concentrations (GMCs) were higher in participants vaccinated with PCV15 compared to those receiving PCV13 after dose 3 and 4 (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3).

Six studies provided data on the opsonophagocytic activity (OPA) GMR12,17,21,22,26,31. In total, infants received 3 or 4 PCV doses of either PCV15 or PCV13. Study investigators used a microcolony multiplex opsonophagocytic assay (mOPA) to measure the serotype-specific OPA GMT. In most studies, OPA antibody titres were only available from a subset of randomised participants. Random-effects meta-analyses with data from healthy pneumococcal vaccine–naïve infants (6 studies14,17,21,22,26,31, N ranged from 1762 to 1873 across serotypes, OPA GMR ranged from 0.58 to 1.28; Supplementary Fig. 4) yielded the non-inferiority of PCV15 compared with PCV13 for 12 shared serotypes, as indicated by the lower confidence limit of the OPA GMR being above 0.5. Specifically, for the shared serotype 3 the lower confidence limit of OPA GMR was 1.13. For the remaining shared serotype, the lower confidence limit was 0.44. Regarding the unique PCV15 serotypes 22F and 33F, OPA geometric mean titres (GMTs) were higher in participants vaccinated with PCV15 compared to those receiving PCV13 (Supplementary Fig. 4). Serotype-specific OPA titres were obtained 30 days after the third or fourth dose. Heterogeneity across studies ranged from low (I² = 0% for serotypes 4, 5 and 9V) to high (I² = 81% for serotype 19F).

We rated the COE as moderate for immunogenicity.

Seven studies reported on IgG response, defined as the proportion of participants with IgG titre concentrations ≥0.35 μg/mL in healthy pneumococcal vaccine–naïve infants (N ranged from 5104 to 5128 across serotypes)13,14,15,21,22,26,31. A random-effects meta-analysis rendered the non-inferiority of the PCV15 serotype-specific IgG response compared with PCV1313,14,15,21,22,26,31. For serotype 3 and unique serotypes 22F and 33F the lower confidence limit of the pooled risk difference was above 0 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Supplementary Fig. 6 shows the serotype-specific IgG response (IgG titre concentrations ≥0.35 μg/mL) after 30 days in three age-dependent catch-up vaccination cohorts.

Children and adolescents with chronic medical conditions or immunosuppression

Three trials reported on the immunogenicity of the PCV15 compared with the PCV13 vaccine in children and adolescents at an increased risk of IPD (N = 525)27,32,33. Supplementary Fig. 7 presents OPA GMRs while Supplementary Figs. 8 shows IgG GMR 30 days after PCV15 compared with PCV13 in two studies that included children and adolescents with HIV or sickle cell disease27,32. One study reported a serotype-specific OPA response defined as a 4-fold or greater increase in OPA titres 30 days post-vaccination in children with HIV (Supplementary Fig. 9)32.

The only study on allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation patients included both adults and children33, however, most participants were adults. Since the authors did not provide immunogenicity data separately, we summarised the findings of this study in the adult section.

Safety

Twelve studies provided data on safety in infants, children, or adolescents12,13,14,15,17,21,22,26,27,31,32,33.

PCV15 vs. PCV13

Healthy infants and children and adolescents

Nine studies reported on safety outcomes in healthy pneumococcal vaccine–naïve infants who received 3 or 4 doses of either PCV15 or PCV1312,13,14,15,17,21,22,26,31. In all studies, the first dose was administered at the age of approximately 2 months12,14,15,17,21,22,26,31, except for one study, where the first vaccine dose was given at approximately 8 months of age13.

To ensure homogeneity in the meta-analyses regarding population and intervention, we included only data from infants younger than 12 months when they received the first dose of a series of at least two doses (primary series) of the same adjuvanted PCV vaccine.

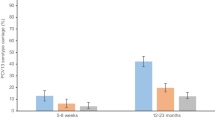

In a random-effects meta-analysis with data from 9 RCTs12,13,14,15,17,21,22,26,31 and 9,445 infants, the risk of any adverse events 14 days after any PCV dose was the same in infants who received PCV15 and those who received PCV13 (94.6% vs. 94.6%, risk ratio [RR] 1.00; 95% CI, 0.99 to 1.01; Fig. 2).

Forest Plot of Meta-Analysis Comparing PCV15 and PCV13: Risk of any adverse events in healthy pneumococcal vaccine–naïve infants. CI confidence interval, G1 group1: G5 group 5, PCV15 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, PCV13 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, RR risk ratioEvents refers to the number of participants with any adverse event after any dose of PCV15 or PCV13. Total refers to the number of participants in the safety population of the PCV15 and PCV13 group. Banniettis 2022 Cohort 1: participants aged 7–11 months at the time of receiving the first dose. Bili 2023 G5 vs. G1: Only Group 5 (PCV15) and Group 1 (PCV13) were included in the meta-analysis. Groups 3 and 4, which received mixed schedules (PCV13/PCV15), were not considered. Platt 2020 Lot 1 + 2: The study investigator compared two different PCV15 lots (unique identifiers assigned to specific vaccine doses) with PCV13. We combined the safety data from the PCV15 Lot 1 and Lot 2 groups.

A random-effects meta-analysis with data from 8 RCTs12,13,14,15,17,21,22,31 and 8,401 infants yielded similar risks of injection site reactions (76.1% vs. 74.6%, RR 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99 to 1.06; Supplementary Fig. 10) and systemic reactions (91.6% vs. 91.6%, RR 1.00; 95% CI, 0.99 to 1.01; Supplementary Fig. 11) in the PCV15 and PCV13 groups.

Likewise, the risk of any serious adverse events (including both vaccine-related and non-vaccine-related events) up to 6 months after the last dose was similar in the PCV15 and PCV13 groups, based on a random-effects meta-analysis including data from 9 RCTs12,13,14,15,17,21,22,26,31 and 9,445 healthy pneumococcal vaccine–naïve infants (8.3% vs. 8.4%, RR 0.99; 95% CI, 0.86 to 1.14; Fig. 3).

Forest Plot of Meta-Analysis Comparing PCV15 and PCV13: Risk of any serious adverse events in healthy pneumococcal vaccine–naïve infants. CI confidence interval, G1 group 1, G5 group 5, PCV15 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, PCV13 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, RR risk ratio. Events refers to the number of participants with serious adverse event after any or the last dose of PCV15 or PCV13. Total refers to the number of participants in the safety population of the PCV15 and PCV13 group. Banniettis 2022 Cohort 1: participants aged 7–11 months at the time of receiving the first dose. Bili 2023 G5 vs. G1: Only Group 5 (PCV15) and Group 1 (PCV13) were included in the meta-analysis. Groups 3 and 4, which received mixed schedules (PCV13/PCV15), were not considered. Platt 2020 Lot 1 + 2: The study investigator compared two different PCV15 lots (unique identifiers assigned to specific vaccine doses) with PCV13. We combined the safety data from the PCV15 Lot 1 and Lot 2 groups.

We rated the COE for all safety outcomes in infants as high.

Children and adolescents with chronic medical conditions or immunosuppression

Three phase 3 trials with 525 participants evaluated the safety of PCV15 compared to PCV13 in children and adolescents at increased risk of IPD27,32,33. The study by Quinn et al. randomised a total of 103 children from 5 to 17 years of age with sickle cell disease to either a single dose of PCV15 or PCV1327. The proportions of participants with one or more adverse events (81.2% vs. 79.4%; RR 1.02; 95% CI, 0.83 to 1.26) or injection site (69.6% vs. 76.5%; RR 0.91; 95% CI, 0.71 to 1.16) or systemic reactions (60.9% vs. 55.9%; RR 1.09; 95% CI, 0.76 to 1.55) were comparable between the vaccination groups. Likewise, serious adverse events up to 6 months after vaccination were similar across groups (Supplementary Fig. 12). No statistically significant differences were found in children with HIV32 or after allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation33 (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Studies in adults

Nine eligible RCTs included 7,930 adults16,18,19,20,23,24,25,28,29,30,33. Two studies included immunocompromised participants23,33, and seven focused on healthy participants, participants with stable underlying conditions16,20,24,25,28,29,30, or participants with or without risk factors for pneumococcal disease.18,19 Three studies were conducted as phase 2 trials16,24,30; all others were phase 3 trials18,19,20,23,25,28,29,33. The studies included between 253 and 2,340 participants. The mean age of the adult participants ranged from 36 to 73 years. Between 21.2% and 59.7% of participants were female. The proportion of non-white participants ranged from 5.9% to 70.5%.

PCV15 or PCV13 was administered either as a single dose or as a sequential scheme with PPSV23. One study with three arms compared single doses of PCV15, PCV13, and PPSV23.16 One study in patients with HIV infections evaluated 1 dose of PCV15 or PCV13 followed by 1 dose of PPSV23 after 8 weeks.23 Only one study included a population that had been vaccinated previously. Participants in the study by Peterson et al. had received a PPSV23 vaccination at least 1 year prior to the study entry24.

Efficacy and effectiveness

None of the included trials reported on patient-relevant health outcomes (incidence of pneumococcal infection–related death, IPD, pneumonia, pneumococcal infection–related hospitalisation, otitis media), duration of protection post-vaccination, or the proportion of patients colonised with Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Immunogenicity

Nine trials reported data on immunogenicity comparing PCV15 and PCV13 in adults16,18,19,20,23,24,25,28,29,30,33.

PCV15 vs. PCV13

Healthy adults or adults with stable chronic conditions at age 18 or older

We performed a meta-analysis using the data from seven RCTs (N ranged from 6,539 to 6,575 across serotypes) including healthy adults and adults with a stable chronic condition or with or without risk factors for pneumococcal diseases16,18,20,24,25,28,29,30. We used serotype-specific OPA GMTs from serum samples obtained 30 days post–PCV vaccination. The results showed non-inferiority of PCV15 compared with PCV13 for 13 shared serotypes (OPA GMR ranged from 0.77 to 1.79; Supplementary Fig. 13). For serotypes 3, 6B, 18 C, and 23 F the lower confidence limit of the pooled OPA GMR was above 1 (OPA GMR ranged from 1.28 to 1.79; Supplementary Fig. S13). The heterogeneity across studies ranged from low (I² = 13% for serotype 6A) to high (I² = 84% for serotype 3). For the PCV15-specific serotypes 22 F and 33 F, the OPA GMTs were higher in participants receiving PCV15 (OPA GMR ranges: 22F: 13.05 to 144.99 and 33F: 3.05 to 9.94) but with a large heterogeneity among the studies. The results were also confirmed by meta-analyses of the OPA response 30 days post-vaccination (N ranged from 3999 to 4182 across serotypes; Supplementary Fig. 14).

We rated the COE as moderate for immunogenicity.

Adults previously immunised with any other pneumococcal vaccine

Participants (N = 253) in the study by Peterson et al.24 had received PPSV23 vaccination at least 1 year prior to study entry. Their results were similar to those of studies conducted in pneumococcal vaccine–naïve populations. PCV15 demonstrated non-inferiority compared to PCV13 for 13 shared serotypes (OPA GMR ranged from 0.74 to 1.54) For serotypes 3 and 18C (OPA GMR 1.40 and 1.54), and for PCV15-specific serotypes 22F and 33F (OPA GMR 16.33 and 3.05) the lower confidence limit of the OPA GMR was above 1.

Adults with chronic medical conditions or immunosuppression

We identified three RCTs (N = 1,693) that provided immunogenicity data for adults with one or two or more risk factors for pneumococcal diseases19 or HIV23, or children and adults with recent allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation33 (no separate data for adults available). We did not conduct a meta-analysis; we present the results descriptively in a forest plot (Supplementary Fig. 15). The response for serotypes 9V and 19A was lower in adults with one risk factor for pneumococcal diseases receiving PCV15 than for those receiving PCV13 (Supplementary Fig. 16). Wilck et al.33 did not provide response data.

PCV15 vs. PPSV23

Ermlich et al.16 also provided immunogenicity data for the comparison between PCV15 and PPSV23. At 30 days post-vaccination, PCV15 showed non-inferiority compared to PPSV23 for 15 shared-serotypes. For 10 serotypes the lower confidence limit of the OPA GMR was above 1 (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Safety

Nine RCTS (N = 7930) provided data on safety in adults16,18,19,20,23,24,25,28,29,30,33.

PCV15 vs. PCV13

Healthy adults or adults with stable chronic conditions at age 18 or older

All nine RCTs conducted in adults reported on some of the prespecified safety outcomes16,18,19,20,23,24,25,28,29,30,33.

We performed a meta-analysis on the data from adults 50 years of age or older in good health and with stable underlying medical conditions or adults between 18 and 49 years of age in good health with or without any specific risk factors for pneumococcal disease. All participants, apart from those included in the study by Peterson et al.24 who had received PPSV23 vaccination at least 1 year prior to study entry, were pneumococcal vaccine–naïve. We did not consider the studies by Wilck et al.33 and Mohapi et al.23 because of the immunocompromised populations they included. Participants in the studies by Hammitt et al.18 and Song et al.29 received PCV15 or PCV13 in a sequential scheme followed by PPSV23. However, we considered only adverse events that occurred after administration of the PCV dose.

The random-effects meta-analysis including data from six studies16,18,24,25,28,29 and 6,410 adults shows a higher risk of any adverse events 14 days post–PCV dose in participants receiving the PCV15 vaccine than in those receiving the PCV13 vaccine (73.7% vs. 66.4%, RR 1.11; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.18; Fig. 4).

When focusing on injection site reactions, the meta-analysis of six RCTs18,24,25,28,29,30 including 6,409 participants yielded a similar effect, with a slightly higher risk of injection site reactions in those receiving PCV15 (66.2% vs. 56.1%, RR 1.18; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.28; Supplementary Fig. 18). For systemic reactions, the meta-analysis of the same studies18,24,25,28,29,30 also showed a higher rate among participants receiving PCV15 compared to those receiving PCV13 (47.7% vs. 43.8%, RR 1.09; 95% CI, 0.98 to 1.21; Supplementary Fig. 19).

The risk of any serious adverse events (including both vaccine-related and non-vaccine-related events) was similar in the PCV15 and PCV13 groups, based on a random-effects meta-analysis including data from seven RCTs16,18,24,25,28,29,30 and 6,868 adults (2.5% vs. 2.6%, RR 0.95; 95% CI, 0.67 to 1.34; Fig. 5). The studies monitored serious adverse events in adults from 30 days24 up to 13 months29 post–PCV vaccination.

Forest Plot of Meta-Analysis Comparing PCV15 and PCV13: Risk of any serious adverse events in adults. CI confidence interval, PCV15 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, PCV13 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, RR risk ratio. Stacey 2019 PCV15-A: Investigators compared two different formulations of PCV15 (PCV15-A and PCV15-B) with PCV13. The formulations differ in that PCV15-A uses the same conjugation process for all 15 glycoconjugates, while PCV15-B uses the same process as PCV15-A for 8 serotypes and a modified process for 7 serotypes. Only data from the PCV15-A group were included in the meta-analysis.

We rated the COE for all safety outcomes in adults as high.

Adults previously immunised with any other pneumococcal vaccine

The 253 participants in the study by Peterson et al.24 received PPSV23 vaccination at least 1 year prior to study entry. The results showed similar risks of any adverse events (68.5% vs. 64.3%, RR 1.07; 95% CI, 0.89 to 1.27) and systemic reactions (39.4% vs. 40.5%, RR 0.97; 95% CI, 0.72 to 1.32) between the PCV15 and the PCV13 groups. The risk for injection site reactions was higher with PCV15 than with PCV13 (63.0% vs. 51.7%, RR 1.24; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.54). Serious adverse events following 1 dose of PCV were too infrequent in both groups to reach a determinant result (0% vs. 1.6%, RR 0.20; 95% CI, 0.01 to 4.09).

Adults with chronic medical conditions or immunosuppression

Three RCTs evaluated the safety of PCV15 compared to PCV13 in adults with HIV, recent allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation, or with one or two or more risk factors for pneumococcal diseases19,23,33 (Supplementary Fig. 20).

PCV15 vs. PPSV23

Ermlich et al.16 also compared the safety of PCV15 to that of PPSV23. While the proportion of any adverse events was higher in the PCV15 group after 14 days post-vaccination (75.1% vs. 65.7%; RR 1.10; 95% CI, 0.98 to 1.23), proportions of any serious adverse events were similar between the PCV15 and PPSV23 groups after 6 months post-vaccination (1.7% vs. 2.2%; RR 0.57; 95% CI, 0.17 to 1.93; Supplementary Fig. 21).

Discussion

This review summarised the evidence of 20 trials that compared the immunogenicity and safety of PCV15 with PCV13 in healthy and immunocompromised children and adults. One trial also compared PCV15 to PPSV23 in healthy adults. Compared to PCV13, our meta-analysis showed that at 30 days post–PCV vaccination, the PCV15 serotype-specific immune response was non-inferior in 12 shared serotypes in children and 13 shared serotypes in adults. For the unique PCV15 serotypes 22 F and 33 F, OPA GMTs were higher in participants vaccinated with PCV15 compared to those receiving PCV13. As regards to safety, the meta-analyses yielded a similar safety profile for PCV15 and PCV13 in children. Except for a slightly increased risk of adverse events, driven mainly by local injection site reactions, the safety profiles of PCV15 and PCV13 were also comparable in adults.

In adults who were vaccinated with PCV15, our meta-analysis revealed a higher risk of overall adverse events driven by local injection site reactions. The authors of the individual studies noted that the reason for this observed difference currently remains unknown and cannot be attributed to the two additional serotypes or any specific ingredient in PCV1516,25,28,29. However, they did not consider this clinically relevant since the intensity was mild (e.g. injection site pain and swelling), and the symptoms short-lived25,28.

None of the identified trials reported on patient-relevant efficacy outcomes such as incidence of IPD, pneumococcal-related hospitalisation, or duration of protection. However, in terms of clinical endpoints, the efficacy and safety of PCV13 and PPSV23 have been demonstrated in several previously published systematic reviews34,35,36,37. Therefore, to compare a new PCV vaccine to placebo is no longer considered ethically justifiable. Notably, the approval and current recommendations of the PCV15 vaccine are based on the findings on immunogenicity, considered as surrogate outcome, as well as on safety outcomes38,39. Future observational studies might provide additional evidence on patient-relevant effectiveness endpoints and could additionally reveal data on the duration of protection.

The primary and secondary immunogenicity parameters varied across studies. The studies focused on serotype-specific IgG GMC or OPA GMT ratio or response as well as IgG response. For our meta-analysis, we used OPA measurements; however, OPA measurements were often only available in a subset of study participants. We also performed meta-analyses on GMR of serotype-specific IgG GMCs from studies conducted in children. Additionally, we analysed data on IgG response based on the common antibody concentration threshold of ≥0.35 µg/mL.

The serotype 3 is of high clinical relevance since this serotype causes a high pneumococcal disease burden in unvaccinated but also in PCV13 vaccinated populations. This serotype is among the most common that causes IPD in children and adults7. Compared to PCV13, PCV15 induced higher OPA GMTs against serotype 3 in children and adults. However, the importance of this finding is unknown. Future studies need to investigate whether higher OPA GMT also translates to better clinical effectiveness.

Regarding pneumococcal vaccine–naïve healthy infants, the 2 plus 1 schedule consisting of a two-dose primary series and a toddler dose is currently recommended in most of the European countries. However, most of the studies included in our meta-analyses evaluated a 3 plus 1 vaccination schedule. Only the study by Benfield et al.14 and Martinon-Torres et al. in healthy full-term infants (94% of all participants)22 evaluated a 2 plus 1 schedule. Results were similar across serotypes compared with studies that applied a 3 plus 1 vaccination schedule. Notably, we obtained immunogenicity data for meta-analyses 30 days after the primary series (3 doses) and 30 days after the toddler dose (2 plus 1 or 3 plus 1 schedule).

This review summarizes the most recent evidence on the immunogenicity and safety of the PCV15 vaccine compared to PCV13 and PPSV23. Recently, the PCV20 vaccine, another new PCV vaccine that should protect from infections caused by 20 different pneumococcal serotypes, has been approved. In this review, we did not find any head-to-head comparison of the PCV20 with the PCV15 vaccine. The immunogenicity and safety of the PCV20 vaccine in adults were recently evaluated in another review40. The authors found no evidence for differences in tolerability and safety for the comparison of PCV20 with PCV13 and/or PPSV23 evaluated in four phase 2 or phase 3 trials with a duration of six months40. In general, more clinical trials comparing PCV15 with PCV13 are currently available than those comparing PCV20 and PCV13.

Most of the studies were conducted in healthy pneumococcal vaccine–naïve infants and adults 50 years or older in good health and/or with a stable medical condition. Only a few studies focused on children or adolescents between 2 and 17 years of age, younger adults between 18 and 49 years of age, and older adults 65 years of age or older as well as on specific high-risk patient populations suffering from HIV or sickle cell disease, and those who have undergone allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation.

This review has several limitations. First, although we made every effort to identify the whole body of evidence, we might have missed unpublished and unregistered studies. Second, for several studies, the outcome data were only available in supplements or in a clinical trial registry that usually does not undergo peer review or other quality check. Third, all studies were funded by the PCV15 producer. Fourth, we did not find any evidence on health outcomes, and evidence was limited for most of the subgroups of interest. In addition, we did not find any long-term studies assessing the safety and duration of protection. Finally, OPA GMTs were often only available in a subset of study participants.

This systematic review found a similar immune response for the common serotypes in infants and adults vaccinated with PCV15 compared to PCV13. The safety profile in children vaccinated with PCV15 and PCV13 was also comparable. Compared with PCV13, adults vaccinated with PCV15 experienced a slight increased risk of any adverse event, attributed to local injection site reactions. Serious adverse events were similar between groups. Likewise, similar immunogenicity and safety was observed in the few trials conducted in immunocompromised and chronically ill populations and in distinct age groups. For the comparison of PCV15 and PPSV23, limited evidence indicates a similar immune response and tolerability.

Methods

We conducted this systematic review following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews41 and registered the protocol in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO)42 under CRD42023440133. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement43. The PRISMA checklist is provided in the supplementary material (Supplementary Table 9).

Study eligibility criteria

We included studies conducted in infants, children, and adolescents up to 17 years of age as well as adults aged 18 years or older. The intervention of interest was vaccination with PCV15 (Vaxneuvance®, Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC), administered either alone or in a sequential scheme with PPSV23. Valid comparators were no vaccination, placebo, or vaccination with any other approved pneumococcal vaccine alone or sequentially. We considered efficacy and effectiveness, immunogenicity, and safety outcomes. Table 1 presents the inclusion and exclusion criteria in detail.

Literature searches

An expert information specialist (I.K.) performed searches for published studies in MEDLINE (via Ovid)44, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (via Cochrane Library/Wiley)45, and Embase (via Embase.com)46 from inception to 22 May 2023. In addition, we performed searches for completed but unpublished or ongoing studies in ClinicalTrials.gov47 and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)48. We checked if publications were available for eligible studies registered in ClinicalTrials.gov or International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). To identify relevant pre-prints, we searched Europe PubMed Central (PMC)49 in addition to Embase (via Embase.com/Elsevier)46. We did not apply any date or language restrictions to the electronic searches. The electronic search strategies (Supplementary Table 2) were peer-reviewed by a second information specialist following the recommendation of the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS)50. We reviewed the reference lists of relevant studies and systematic reviews and conducted forward citation (i.e. cited by) searches based on all included reports in citationchaser51. In addition, we searched the websites of regulatory agencies (EMA and FDA).

Study selection and management

After piloting, two reviewers independently screened the titles, abstracts, and relevant full-text articles against the predefined eligibility criteria using DistillerSR52. Conflicts were resolved by discussion or by consulting a third reviewer. All results were tracked in an EndNote® 20 (Clarivate) database.

Data extraction

One reviewer extracted the study characteristics and results of each included study into evidence tables. A second reviewer checked all data extractions for completeness and accuracy. We also checked trial register records to obtain information on additional data missing in the publication.

Assessment of the risk of bias

We dually assessed the risk of bias of the RCTs using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool 2.053,54. We would have evaluated the risk of bias of the non-randomized studies of interventions (NRSI) using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomised Studies of Interventions tool (ROBINS-I)55,56 if eligible studies had been identified.

Data synthesis and analysis

We conducted random-effects meta-analyses with three or more clinically and methodologically homogenous studies. We applied the inverse variance method and used the Hartung–Knapp adjustment57. For ad hoc correction, we used the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the classic random-effects model or those from the Hartung–Knapp meta-analysis (whichever was wider)58. We used the restricted maximum likelihood method59 to estimate between-study variance.

We used a generic inverse variance meta-analysis to pool GMRs of OPA GMTs as a continuous outcome. For studies conducted in children, we also performed meta-analysis on GMR of IgG GMCs. If the GMRs were not reported, we calculated them with the corresponding 95% CI from the GMTs or GMCs and 95% CI of each study group by applying the previously described methods40. To compute variances from reported CIs, we employed an approximate formula so that there might be negligible discrepancies in the CIs reported in the source publications and the ones displayed in the forest plots. We considered non-inferiority as the lower bound of the two-sided 95% CI for the serotype-specific OPA GMT and Ig GMC ratio was greater than 0.5.

We performed a random-effects meta-analysis on dichotomous immunogenicity and safety outcomes. We calculated risk differences with 95% CIs for immune response and relative risks with 95% CIs for safety. Response was defined either as the proportion of participants with a ≥ 4-fold increase in OPA titres or the proportion of patients with an IgG concentration ≥0.35 µg/mL. The non-inferiority criterion for the risk difference in response related to each serotype required that the lower bound of the two-sided 95% CI was greater than -10 percentage points. We presented results from meta-analyses as forest plots. To determine the impact of studies with high risk of bias, we intended to perform sensitivity analyses.

We evaluated the clinical and statistical heterogeneity of the trials included in the meta-analyses. We quantified the statistical heterogeneity based on calculated I2 and the statistical test chi square60. Additionally, we calculated 95% prediction intervals for assessing heterogeneity in meta-analyses with more than three studies, indicating the 95% probability range of a future study with similar characteristics to those included in the meta-analysis60,61.

If the data had been sufficient, we would have conducted a subgroup analysis for the following characteristics: age, health status (chronic medical condition or immunosuppression), vaccination status, comparator, setting and geographic location.

If we had included 10 or more studies in the meta-analyses, we would have created funnel plots and perform appropriate statistical tests for small-study effects to assess potential publication bias. All statistical analyses were performed with the meta package62 within the R environment (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)63.

Certainty of the evidence assessment

We used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to assess the certainty of the evidence (COE) for the outcomes listed above64,65. One reviewer rated the COE, and it was verified by a second reviewer. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus involving a third person as needed. We considered all outcomes as critical for decision-making and did not perform an outcome prioritisation exercise.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Factsheet about pneumococcal disease, https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/pneumococcal-disease/facts (2023).

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Annual epidemiological report for 2018 - Invasive pneumococcal disease, https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/invasive-pneumococcal-disease-annual-epidemiological-report-2018 (2020).

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Vaccine Scheduler Pneumococcal Disease: Recommended vaccinations, https://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/Scheduler/ByDisease?SelectedDiseaseId=25&SelectedCountryIdByDisease=-1 (2023).

Bonnave, C. et al. Adult vaccination for pneumococcal disease: a comparison of the national guidelines in Europe. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 38, 785–791 (2019).

Micoli, F., Romano, M. R., Carboni, F., Adamo, R. & Berti, F. Strengths and weaknesses of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. Glycoconj J 40, 135–148 (2023).

Hanquet, G. et al. Serotype Replacement after Introduction of 10-Valent and 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines in 10 Countries, Europe. Emerg Infect Dis 28, 137–138 (2022).

Løchen, A., Croucher, N. J. & Anderson, R. M. Divergent serotype replacement trends and increasing diversity in pneumococcal disease in high income settings reduce the benefit of expanding vaccine valency. Sci Rep 10, 18977 (2020).

Tin Tin Htar, M., Christopoulou, D. & Schmitt, H. J. Pneumococcal serotype evolution in Western Europe. BMC Infect Dis 15, 419 (2015).

Masomian, M., Ahmad, Z., Gew, L. T. & Poh, C. L. Development of Next Generation Streptococcus pneumoniae Vaccines Conferring Broad Protection. 8, 17, (2020).

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Vaxneuvance pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (15-valent, adsorbed), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/vaxneuvance (2024).

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Apexxnar pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (20-valent, adsorbed), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/apexxnar (2024).

Banniettis, N. et al. Safety and Tolerability of V114 Pneumococcal Vaccine in Infants: A Phase 3 Study. Pediatrics 152, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-060428 (2023).

Banniettis, N. et al. A phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active comparator-controlled study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of catch-up vaccination regimens of V114, a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, in healthy infants, children, and adolescents (PNEU-PLAN). Vaccine 40, 6315–6325 (2022).

Benfield, T. et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of V114 pneumococcal vaccine compared with PCV13 in a 2+1 regimen in healthy infants: A phase III study (PNEU-PED-EU-2). Vaccine 41, 2456–2465 (2023).

Bili, A. et al. A phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind study to evaluate the interchangeability of V114, a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, and PCV13 with respect to safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity in healthy infants (PNEU-DIRECTION). Vaccine 41, 657–665 (2023).

Ermlich, S. J. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in pneumococcal vaccine-naive adults >=50 years of age. Vaccine 36, 6875–6882 (2018).

Greenberg, D. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV15) in healthy infants. Vaccine 36, 6883–6891 (2018).

Hammitt, L. L. et al. Immunogenicity, Safety, and Tolerability of V114, a 15-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine, in Immunocompetent Adults Aged 18-49 Years With or Without Risk Factors for Pneumococcal Disease: A Randomized Phase 3 Trial (PNEU-DAY). Open forum infect 9, ofab605 (2022).

Hammitt, L. L. et al. Phase 3 trial to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of V114, a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, followed by 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine 6 months later, in at-risk adults 18-49 years of age (PNEU-DAY): A subgroup analysis by baseline risk factors. Hum Vaccin Immunother 19, 2177066 (2023).

Kishino, H. et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of V114, a 15-valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine, Compared with 13-valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in Japanese Adults Aged >=65 Years: Subgroup Analysis of a Randomized Phase III Trial (PNEU-AGE). Jpn J Infect Dis 75, 575–582 (2022).

Lupinacci, R. et al. A phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active-comparator-controlled study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of a 4-dose regimen of V114, a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, in healthy infants (PNEU-PED). Vaccine 41, 1142–1152 (2023).

Martinon-Torres, F. et al. A Phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active comparator-controlled study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of V114 compared with PCV13 in healthy infants (PNEU-PED-EU-1). Vaccine 41, 3387–3398 (2023).

Mohapi, L. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of V114, a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, in adults living with HIV. Aids 36, 373–382 (2022).

Peterson, J. T. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared to 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in adults >=65 years of age previously vaccinated with 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother 15, 540–548 (2019).

Platt, H. L. et al. A phase 3 trial of safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of V114, 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, compared with 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in adults 50 years of age and older (PNEU-AGE). Vaccine 40, 162–172 (2022).

Platt, H. L. et al. A Phase II Trial of Safety, Tolerability and Immunogenicity of V114, a 15-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine, Compared With 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in Healthy Infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 39, 763–770 (2020).

Quinn, C. T. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of V114, a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, in children with SCD: a V114-023 (PNEU-SICKLE) study. Blood Adv 7, 414–421 (2023).

Simon, J. K. et al. Lot-to-lot consistency, safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of V114, a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, in healthy adults aged >=50 years: A randomized phase 3 trial (PNEU-TRUE). Vaccine 40, 1342–1351 (2022).

Song, J. Y. et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of V114, a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, followed by sequential PPSV23 vaccination in healthy adults aged>=50years: A randomized phase III trial (PNEU-PATH). Vaccine 39, 6422–6436 (2021).

Stacey, H. L. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-15) compared to PCV-13 in healthy older adults. Hum Vaccin Immunother 15, 530–539 (2019).

Suzuki, H. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Japanese healthy infants: A phase III study (V114-033). Vaccine 41, 4933–4940 (2023).

Wilck, M. et al. A phase 3 study of safety and immunogenicity of V114, a 15-valent PCV, followed by PPSV23, in children living with HIV. Aids 20, 20 (2023).

Wilck, M. et al. A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-Blind, Comparator-Controlled Study to Evaluate Safety, Tolerability, and Immunogenicity of V114, a 15-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine, in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients (PNEU-STEM). Clin Infect Dis, ciad349, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad349 (2023).

Lucero, M. G. et al. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines for preventing vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease and X-ray defined pneumonia in children less than two years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009, Cd004977 (2009).

Hsiao, A. et al. Incidence and Estimated Vaccine Effectiveness Against Hospitalizations for All-Cause Pneumonia Among Older US Adults Who Were Vaccinated and Not Vaccinated With 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine. JAMA Network Open 5, e221111–e221111 (2022).

Falkenhorst, G. et al. Effectiveness of the 23-Valent Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine (PPV23) against Pneumococcal Disease in the Elderly: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 12, e0169368 (2017).

Kraicer-Melamed, H., O’Donnell, S. & Quach, C. The effectiveness of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine 23 (PPV23) in the general population of 50 years of age and older: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 34, 1540–1550 (2016).

Kobayashi, M. et al. Use of 15-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine and 20-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Among U.S. Adults: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 71, 109–117 (2022).

Kobayashi, M. et al. Use of 15-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Among U.S. Children: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 71, 1174–1181 (2022).

Schlaberg, J. et al. Aktualisierung der Empfehlungen der STIKO zur Standardimpfung von Personen ≥ 60 Jahre sowie zur Indikationsimpfung von Risikogruppen gegen Pneumokokken und die dazugehörige wissenschaftliche Begründung. Epid Bull 39, 3–44 (2023).

Higgins, J. P. et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023), https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (2023).

National Institute for Health and Care Research. PROSPERO, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ (2023).

Page, M. J. et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n160 (2021).

U.S. National Library of Medicine. Ovid MEDLINE, https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/ovid/ovid-medline-901? (2023).

Cochrane Library. Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/about-central (2023).

Elsevier Ltd. Embase, https://www.embase.com/search/quick?phase=continueToApp (2023).

National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (2023).

World Health Organization. International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), https://www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform (2024).

Europe PMC. Europe PMC, https://europepmc.org/ (2023).

McGowan, J. et al. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol 75, 40–46 (2016).

citationchaser: an R package for forward and backward citations chasing in academic searching v. 0.0.3 (2021).

DistillerSR Inc. DistillerSR. Version 2.35. https://www.distillersr.com/ (2023).

Sterne, J. A. C. et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj 366, l4898 (2019).

Higgins, J. P. T., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G. & Sterne, J. A. C. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial., www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (2022).

Sterne, J. A. et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Bmj 355, i4919 (2016).

Sterne, J. A. C., Hernán, M. A., McAleenan, A., Reeves, B. C. & Higgins, J. P. T. Chapter 25: Assessing risk of bias in a non-randomized study, www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. (2022).

Hartung, J. & Knapp, G. A refined method for the meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials with binary outcome. Stat Med 20, 3875–3889 (2001).

Jackson, D., Law, M., Rücker, G. & Schwarzer, G. The Hartung-Knapp modification for random-effects meta-analysis: A useful refinement but are there any residual concerns? Stat Med 36, 3923–3934 (2017).

Langan, D. et al. A comparison of heterogeneity variance estimators in simulated random-effects meta-analyses. Res Synth Methods 10, 83–98 (2019).

Deeks, J. J., Higgins, J. P. T. & Altman, D. G. Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses, www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. (2022).

IntHout, J., Ioannidis, J. P., Rovers, M. M. & Goeman, J. J. Plea for routinely presenting prediction intervals in meta-analysis. BMJ Open 6, e010247 (2016).

Balduzzi, S., Rücker, G. & Schwarzer, G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid Based Ment Health 22, 153–160 (2019).

R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2021).

McMaster University and Evidence Prime Inc. GRADEpro GDT, https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/ (2023).

Schünemann, H. et al. Chapter 14: Completing ‘Summary of findings’ tables and grading the certainty of the evidence, https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-14 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This review was commissioned by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), as part of the activities of the ECDC’s EU/EEA NITAG Collaboration, in close cooperation with the European Commission and the European Health and Digital Executive Agency (HaDEA). The commissioning and production of this review was coordinated by Kate Olsson (ECDC) and Karam Adel Ali (ECDC). This review was funded by the EU4Health Programme under a service contract with the European Health and Digital Executive Agency (HaDEA). The information and views set out in this review are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of HaDEA or the European Commission. Neither HaDEA or the European Commission nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. The APC was funded by University for Continuing Education Krems (Danube University Krems). The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the result. We gratefully acknowledge Sandra Hummel for project administration and formatting. We thank Kathrin Grummich, Dipl.-Gesundheitswirtin (FH) (University of Freiburg, Institute for Evidence in Medicine) for peer review of the MEDLINE search strategy. We acknowledge the use of ChatGPT for language editing in preparing this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IK developed the search strategy and conducted electronic literature searches. GW performed statistical analysis. G.W., K.T., D.L., J.F. and I.S. conducted literature screening, data extraction and risk of bias assessment. G.W. and I.S. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. I.K., D.L., K.T. and J.F. critically revised the manuscript. G.G., K.M.S., D.D., K.O., K.A.A. and the EU/EEA NITAG Collaboration working group members (S.V.B., H.S., D.Z., M.G.V., M.O., R.C., D.T., FKL) advised this project and critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

H.S. is an adviser to Adult Immunization Board, AIB (travel expenses reimbursed), meetings funded by an unrestricted grant from Vaccines Europe. H.S. employer Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare has received research funding from several pharmaceutical vaccine manufacturing companies until March 2022. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wagner, G., Gartlehner, G., Thaler, K. et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, a systematic review and meta-analysis. npj Vaccines 9, 257 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-01048-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-01048-y

This article is cited by

-

Nasopharyngeal pneumococcal carriage and serotype landscape in children, adolescents and young adults in Türkiye

European Journal of Pediatrics (2026)