Abstract

The four serotypes of dengue virus (DENV1-4) are a major health concern putting 50% of the global population at risk of infection. Crucially, DENV vaccines must be tetravalent to provide protection against all four serotypes because immunity to only one serotype can enhance infections caused by heterologous serotypes. Uneven replication of live-attenuated viruses in tetravalent vaccines can lead to disease enhancement instead of protection. Subunit vaccines are a promising alternative as the vaccine components are not dependent on viral replication and antigen doses can be controlled to achieve a balanced response. Here, we show that a tetravalent subunit vaccine of dengue envelope (E) proteins computationally stabilized to form native-like dimers elicits type-specific neutralizing antibodies in mice against all four serotypes. The immune response was enhanced by displaying the E dimers on liposomes embedded with adjuvant, and no interference was detected between the four components.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dengue viruses (DENVs), estimated to infect several hundred million people each year1, continue to be a global health threat. The four DENV serotypes (DENV1-4) are genetically distinct but share similarities in structure, which generate both serotype-specific and cross-reactive antibodies (Abs)2,3,4,5,6,7. Severe disease is most often observed following secondary infection with a DENV serotype that differs from the primary infection8,9,10,11. In this scenario, there is evidence that cross-reactive Abs elicited during the primary infection fail to neutralize the secondary infection and mediate cellular uptake of the virus, enhancing the disease through a process termed antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE)4,12,13. Traditional tetravalent vaccine approaches using live-attenuated viruses (LAV) have faced safety concerns due to uneven replication of the LAVs stimulating an unbalanced immune response to just one or two serotypes14,15,16,17,18. The most advanced LAV DENV vaccine, Dengvaxia, is unbalanced and stimulates an immune response to mainly DENV419. In this case, the vaccine mimicked a primary DENV4 infection for seronegative individuals. Consequently, young children without any dengue immunity who received this vaccine were at greater risk of hospitalization when exposed to DENV1, 2 or 3 infections compared to unvaccinated children20,21. Alternative vaccine approaches like subunit vaccines and virus-like particles, which are independent of virus replication, could potentially bypass this problem.

DENVs are enveloped viruses with a glycoprotein called the envelope (E) protein displayed on the viral surface. On the virion, the E protein forms 90 head-to-tail dimers which pack against each other to create a protein coat with icosahedral symmetry22,23. The E protein is the main target of the human antibody response3. Neutralizing antibodies bind to a variety of epitopes on E protein, including quaternary epitopes which incorporate residues from both chains of the E homodimer24,25,26. As subunit vaccines, wildtype soluble E proteins (sE) have multiple disadvantages: they are difficult to produce, are thermally unstable and do not form dimers at physiological conditions27. Previously, we reported a set of amino acid mutations that stabilize soluble dimers across DENV1-4, increase expression levels, and improve their thermal stability28,29.

Cobalt-porphyrin phospholipid (CoPoP) liposomes are a vaccine platform that function as a nanoliposome vehicle for antigen display while enabling co-delivery of immunostimulatory adjuvants30,31,32. CoPoP chelates cobalt ions within the lipid bilayer of liposomes, serving as an anchor to display proteins bearing polyhistidine tags (His-tags). His-tagged proteins rapidly and spontaneously associate with the liposomes upon admixture in aqueous solution, with multiple copies of the protein presented on a single liposome. Besides CoPoP, also embedded in the lipid bilayer of the liposomes are the immunostimulatory vaccine adjuvants PHAD-3D6A, a form of synthetic monophosphoryl lipid A, and QS-21, a saponin, and together these liposomes are referred to as CPQ. These adjuvant components work synergistically to stimulate cytokine production and boost the antibody response33. CPQ liposomes have been used in several vaccine studies34,35,36. Most recently, a CoPoP vaccine displaying the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain (EuCorVac-19) has successfully concluded phase II trial and progressed to a phase III trial37,38,39.

In this study, we characterize the antibody response in mice of monovalent and multivalent formulations of stabilized E dimers and WT sE presented on CPQ liposomes. We also perform experiments with control liposomes that do not contain cobalt (termed LPQ) but include the same adjuvants as the CPQ liposomes, thereby isolating the impact of liposomal display. In this case, the E protein is not displayed on the liposomes and the liposomes just serve as an adjuvant. Our results show that the stabilized E dimers elicit more neutralizing antibodies than soluble WT E and that displaying the E dimer on CPQ liposomes improved both antibody quantity and neutralization for some DENV serotypes. From the multivalent vaccine studies, we found that the neutralizing response was type-specific with no interference between vaccine components. These results show that the stable E dimers are promising vaccine antigens and the tetravalent formulation with CPQ liposome is a potential candidate for a safe subunit vaccine.

Results

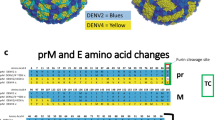

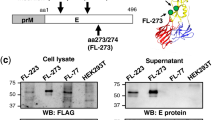

Stabilization of DENV1-4 E dimers

Soluble recombinant wildtype (WT) E proteins have low expression yields, do not form dimers at concentrations below 1 μM at 37 °C, and do not bind tightly to neutralizing antibodies with epitopes that span across the E dimer27,29. To enable the use of the E protein as an effective subunit vaccine, we previously identified amino acid mutations that stabilize the E dimer and raise expression yields28,29. These E stabilized combinations (referred to as SC proteins) include mutations at the central αB interface (I2 or I9), the domain I-II hinge (S1, U6), and in the core of domain I (P4) (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. 1). Mass photometry experiments with SC variants of the four DENV serotypes show that all four proteins are primarily homodimers at a protein concentration of 50 nM, while WT DENV2 (Thai 16681), WT DENV3 (CH53489), and WT DENV4 sE (TVP-376) are almost exclusively monomeric (Fig. 1B, C). Purification yields were too low for the WT DENV1 E protein (WestPac74) to allow mass photometry experiments.

A Cartoon depiction of recombinant E homodimers with monomers (gray, colored) in head-to-tail orientation. Mutation sets at the dimer interface (I2, I9), domain I/II hinge (U6, S1) and domain I core (P4) increased protein production and homodimer affinity. These mutations were applied to DENV1-4 sE to obtain stable dimers for all four serotypes. B Mass photometry histograms of DENV sE WT and SC at 50 nM and room temperature. C Summary of yield and dimer stability of DENV sE. Yields and mass photometry data for DENV sE WT were obtained from (29, Figs. 2A and 3A), yields for DENV sE SC are from small scale and large-scale expressions in Expi293F; nd = no data, as we were unable to produce enough DENV1 sE WT for analysis.

sE proteins are easily coupled to CPQ liposomes

For immunogenicity studies, we formulated sE proteins with liposomes to investigate the effects of antigen display and adjuvant on antibody response. The liposomes (LPQ and CPQ) are bilayer lipid vesicles containing the adjuvants PHAD-3D6A and QS-21 (Fig. 2A). In addition, both CPQ and LPQ contain CoPoP or its non-metal analog of porphyrin-phospholipid (PoP) respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2A). CPQ liposomes act as an adjuvant and a display platform, whereas LPQ liposomes serve strictly as an adjuvant.

A Components in LPQ and CPQ liposomes. B Example conjugation scheme for sE SC and CPQ. sE proteins were mixed with CPQ at 1 sE : 4 CoPoP mass ratio for 4 h at room temperature (RT) to conjugate antigens to liposomes. Complete conjugation results in 5-6 sE dimers per vesicle on average. Nickel (Ni) binding was used to assess conjugation efficiency. Free proteins (sE, ~50 kDa) and CPQ-conjugated proteins (CPQ-sE) were incubated with Ni beads. Beads and flow-through (FT) fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE to determine bound and unbound protein. C Particle size characterization by dynamic light scattering (n = 3 or n = 4, mean ± sd). D Comparison between binding of DV sE SC (grey, solid) and sE WT proteins (grey, hollow) versus CPQ-coupled sE, CPQ-sE WT (blue, hollow) and CPQ-sE SC (blue, solid), to quaternary epitope Abs (B7, C10) and Abs with epitopes encompassed within the E monomer (1C19 – domain II, 1M7 – domain II). Anti-E Abs were conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (AP). AP-labelled anti-mouse IgG (aM) was used as negative control. Duplicate data represented as mean ± s.e.m.

sE proteins containing a C-terminal 8x His tag were incubated with CPQ liposomes for 4 h at room temperature in the dark at a mass ratio of 1:4 sE:CoPoP (Fig. 2B). The mass ratio is calculated based on the molecular weight of monomer sE and corresponds to 5-6 E dimers per liposome (Supplementary Fig. 2B). As a control, proteins were also mixed with LPQ at the same ratio of sE:PoP. To assess the efficiency of coupling to LPQ and CPQ liposomes, we used nickel beads to pull out unbound proteins and separated them from liposome-bound sE via filtration (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Fig. 2C). SDS-PAGE analysis of different fractions showed that sE proteins (~50 kDa) mixed with LPQ samples were associated with the nickel beads, similar to soluble protein control, suggesting that there was no interaction between the His tag of sE and LPQ. sE proteins incubated with CPQ liposomes were found in the flow-through fraction, indicating that the His tag of these proteins did not interact with nickel beads and that the proteins were fully bound to the CoPoP moiety.

The hydrodynamic diameter of the liposome samples did not change after protein incubation as evidenced by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Fig. 2C). On average, CPQ liposomes (103 ± 4 nm preincubation, 103 ± 2 nm post incubation) remain slightly smaller than LPQ liposomes (114 ± 2 nm; 112 ± 3 nm). We observed no indication of protein-induced aggregation or fusion of lipid vesicles in any of the samples. From the DLS and nickel bead experiments, we concluded that sE proteins were completely attached to CPQ liposomes and that the integrity of liposomes was maintained after conjugation. The CPQ-coupled sE proteins will be referred to as CPQ-sE from here on.

Formulation with liposomes does not affect Ab epitopes on sE proteins

We used well-characterized anti-dengue monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to test if liposome-display interfered with sE structure and epitope accessibility (Fig. 2D). First, the binding profiles of unconjugated sE WT and SC at 37 °C were obtained by coating soluble proteins on a nickel ELISA plate and probing with a panel of human mAbs. Consistent with the mass photometry data, DENV2 and DENV3 sE SC (grey bars) are stable dimers that exhibit stronger binding to E dimer dependent quaternary epitope binding mAbs B7 and C1024,40 than WT proteins (white bars). The antibody 1C1941, which binds to the second domain of E (DII), also bound more tightly to stabilized E dimers. In both serotypes, we found that fusion loop mAb 1M7 bound equally well to sE WT and SC. DENV1 and DENV4 sE SC also bound to both quaternary epitope mAbs and monomer epitope mAbs. These results show that the sE SC proteins are well folded and dimeric as they bind to both monomer and dimer epitope Abs, while the WT sE proteins bind only to monomer epitope Abs. These results also demonstrate that the mutations introduced to stabilize the E dimer do not disrupt epitopes frequently targeted by anti-DENV antibodies.

To assess whether coupling to CPQ liposomes affected epitope presentation, CPQ-sE samples were captured onto ELISA plates by human mAb 1M7. Similar to the unconjugated sE proteins, DENV2 and DENV3 CPQ-sE SC (Fig. 2D, blue shaded bars) show stronger binding to complex epitope Abs (B7 and C10) than CPQ-sE WT (blue hollow bars). As the binding signal of mAbs to CPQ-sE WT samples were low, we performed the same experiment using mouse mAb 4G2 as a capture antibody (Supplementary Fig. 3). Here, we observed that CPQ-sE WT had equivalent binding to 1M7 as the CPQ-sE SC samples, but weaker binding to dimer mAbs, mimicking the recombinant sE results. Given that the same amount of sE was fully coupled to CPQ liposome (Supplementary Fig. 2C) and that CPQ-sE WT samples do not bind to dimer Abs as opposed to CPQ-sE SC, these findings suggest that liposome conjugation does not induce dimer formation of the sE WT protein and maintains dimer epitopes on sE SC. The binding of DENV1 and DENV4 SC to the same Abs were also not affected by CPQ coupling.

Mice immunized with DENV CPQ-sE SC elicit antibodies that neutralize mature dengue virus

BALB/c mice were immunized intramuscularly with different formulations of proteins: DENV2 or DENV3 sE alone, a bivalent cocktail with DENV2 and DENV3 proteins and a tetravalent group with DENV1-4 sE (Fig. 3A). Within the monovalent and bivalent groups, we compared the immunogenicity of WT and SC proteins formulated with CPQ (displayed) or LPQ (non-displayed) liposomes; the nomenclature CPQ 2 WT describes a monovalent vaccine of CPQ-sE WT from DENV2, whereas LPQ 2 + 3 SC is a bivalent formulation of LPQ + DENV2 sE SC and LPQ + DENV3 sE SC. The tetravalent group (CPQ Tet SC) consists of a cocktail of CPQ-sE SC from DENV1-4. In the multivalent experiments with CPQ liposomes, sE proteins from the various serotypes were coupled separately with liposomes and then combined for injection. With this approach, each individual liposome only displays E protein from a single serotype. We also included a bivalent mixture of the DENV2 and DENV3 stable dimers formulated with Alum as an adjuvant to compare the immunogenicity of CPQ-sE and a more traditionally formulated subunit vaccine.

A Mouse vaccination scheme: mice (n = 6 per group) were immunized at weeks 0 and 4, with blood drawings on week 4 (pre-boost), 5, 8 and a final bleed at week 12. Groups include monovalent DENV2 or DENV3, bivalent DENV2 and DENV3 and tetravalent DENV1-4. B Binding IgG titer to mature DENV2 (top) and DENV3 (bottom) represented as midpoint dilution (logEC50) across groups, mean ± sd. For DENV2 binding, logEC50 of DENV3-vaccinated groups was significantly lower than LPQ/CPQ 2 SC and bivalent groups with CPQ/LPQ. For DENV3 binding, logEC50 of DENV2-vaccinated groups was significantly lower than LPQ/CPQ 3 SC and bivalent groups containing sE SC (statistics not depicted on graph). C Mature virus neutralizing titers, DENV2 (top) and DENV3 (bottom), represented as the serum dilution factor at which 50% of the virus was neutralized (FRNT50), mean ± sd. For DENV2 neutralization, FRNT50 of DENV3-vaccinated mice was significantly lower than monovalent DENV2 groups and CPQ 2 + 3 SC. For DENV3 neutralization, FRNT50 of DENV2-vaccinated was significantly lower than DENV2-monovalent and bivalent groups with LPQ/CPQ-sE SC (statistics not depicted on graph). D Binding IgG (placebo-subtracted) and neutralizing titer against mature DENVs across monovalent CPQ-sE groups, bivalent groups and tetravalent CPQ-sE. The horizontal dotted line represents the limit of detection of the neutralization assays. Statistical analysis by a one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

All vaccinated mice generated Abs that bind the matched viruses (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Fig. 4A, B). At week 12, mice immunized with DENV2 sE proteins produced similar amounts of binding antibodies to DENV2 in both the monovalent (pink) and bivalent formulations (purple). Likewise, mice immunized with the DENV3 sE proteins produced similar amounts of binding antibodies to DENV3 in both the monovalent (green) and bivalent formulations (purple). Binding was largely type-specific, as the monovalent formulations did not generate large binding signals against the mismatched viruses. Within the monovalent groups, vaccination with the WT proteins induced lower levels of binding Abs than vaccination with SC proteins (p < 0.05–0.005), while no significant binding differences were observed between the LPQ and CPQ formulations of the SC proteins.

For most animal groups, there was a strong correlation between the levels of binding IgG (Fig. 3B) and neutralization titers (Fig. 3C). Neutralization titers were measured with mature viruses produced in Vero cells with increased furin expression (Vero Furin cells). There was a robust type-specific neutralizing Ab response in the monovalent groups: i.e. all DENV2-vaccinated mice (pink) elicited high neutralizing Ab titer to DENV2 virus but not DENV3. Similarly, DENV3-vaccinated mouse sera only neutralized DENV3. Introducing 2 or more DENV serotypes in the formulations did not affect the strength of the response, evidenced clearly in the CPQ-sE SC bivalent (purple) formulation.

Comparing across viruses, it was apparent that there was a cross-reactive (CR) response in the CPQ vaccinated groups (Fig. 3D, Supplementary Fig. 4C), but CR Abs alone did not induce high neutralization titers (Fig. 3D). While there was a positive correlation between binding IgG level and virus neutralization (Supplementary Fig. 5), only the tetravalent formulation (black) elicited strong binding and neutralizing titers against DENV1 and DENV4, outperforming both monovalent and bivalent formulations targeting DENV2 and DENV3. Strikingly, the tetravalent formulation induced approximately equivalent Ab levels as mono- and bi-valent versions despite containing half the amount of each protein. Overall, the CPQ Tet SC formulation elicited a strong response against all four DENV serotypes with FRNT50 titers between 103 and 104.

In all cases, formulations containing sE SC elicited stronger responses than those containing sE WT. This may reflect more effective presentation of neutralizing Ab epitopes, as evidenced by our binding studies with monoclonal antibodies (Fig. 2). In comparing the LPQ and CPQ formulations, the effect of displaying antigens was most evident in the DENV2 neutralization assays (Fig. 3C). Both CPQ 2 SC and CPQ 2 + 3 SC groups elicited higher neutralizing titers than the corresponding LPQ groups. The same did not apply for DENV3-neutralizing response. LPQ and CPQ formulations were equally effective. Overall, the DENV3 neutralization titers were very high which may obscure differences between the LPQ and CPQ formulations.

Neutralizing activity comes from type-specific (TS) Abs

To further probe the immune response to the various vaccine formulations, we performed depletion experiments to study the contribution of type-specific (TS) and cross-reactive (CR) Abs to virus neutralization (Fig. 4A). sE-coupled magnetic beads were used to remove all DENV specific Ab or just CR Abs from the mouse sera. For instance, with the bivalent CPQ 2 + 3 SC sera, we used DENV2 sE SC-coupled beads to pull out all DENV2-binding Abs, DENV3 sE SC-coupled beads to pull out all DENV3-binding Abs, and a combination of DENV1 and DENV4 sE to remove CR Abs that were elicited (Fig. 4B). After depletions, neutralization titers were measured with mature viruses produced in VeroFurin cells. The TS or CR nature of the neutralizing response is of interest because in humans TS Abs have been shown to be strongly protective and long-lasting, whereas CR Abs provide more breadth but have been implicated in weak protection and ADE. We used stable sE SC proteins to deplete CR Abs from WT-vaccinated mice as we were unable to produce all sE WT proteins.

A Representative schematic of a depletion experiment for mouse serum from bivalent DENV2 + 3 formulation. The serum is hypothesized to contain both type-specific (TS) Abs for DENV2 and DENV3, and cross-reactive (CR) Abs that can bind all four DENVs. Specific Ab components are pulled out of the serum by corresponding sE (DENV2, DENV3 or DENV1 + 4). The neutralizing response against DENV2 and DENV3 is re-evaluated after depletion to establish the protective role of TS or CR Abs. B Layout of the depletion experiment. Pooled serum from each group (monovalent DENV2, monovalent DENV3, bivalent DENV2 + 3 and tetravalent DENV1-4) was incubated with the corresponding vaccinating sE (WT or SC) to deplete all TS Abs and the remaining combination of proteins (SC only) to deplete CR Abs. BSA was used as a no depletion control. Each sample underwent 3 rounds of depletion. Neutralization of mature DENV2 & DENV3 by monovalent and bivalent pooled mouse sera (C) and DENV1-4 by tetravalent sera (D) at 1:420 dilution (DV4 at 1:250) after depletion by the vaccinating sE (solid circle) or the remaining sE (hollow circles). Neutralization was represented as virus inhibition of the depleted samples normalized to mean inhibition of the BSA control sample. Data represented as mean ± s.e.m. of duplicates.

For all vaccine formulations, the neutralizing response was maintained unless sE protein from the matched serotype was used for depletions (Fig. 4C, D). For monovalent DENV2 or DENV3 groups, removal of CR Abs by depleting sera with the other sE SC had little effect on neutralization (hollow teal or hollow purple circles). In bivalent formulations, we found that the mouse sera still maintained their DENV3 neutralization after the CR Abs were depleted either using DENV2 sE (solid teal circles) or DENV1 and 4 sE SC (yellow hollow circles). Similarly, there was little change in DENV2 neutralization when bivalent sera were depleted with DENV3 protein or DENV1 + 4 sE SC. Only when depleting with the matching sE to the virus (solid teal or purple circles), did the neutralizing response decrease significantly to background level. The same finding applies for the tetravalent formulation: the neutralizing response to each virus was only completely diminished if the matching serotype sE beads were present during the depletion. I.e., DENV1 neutralization was only abolished if DENV1 sE SC was used to deplete the serum and not DENV2, DENV3 or DENV4 individually or in combination. These results show that CR Abs generated by the mice play minor roles in the neutralization of mature DENVs and most of the neutralization activity comes from Abs specific to each DENV serotype.

Discussion

The results of our study indicate that multivalent administration of DENV E dimers on CPQ liposomes in mice elicits TS neutralizing Abs against all four DENV serotypes with no interference. In some cases, the CPQ-sE SC formulations had higher neutralization titers than formulations based on WT proteins, LPQ adjuvant or Alum. The increase in immunogenicity was partly due to the antigen, which corroborates previous reports that sE dimers elicit higher IgG titers than WT and monomeric proteins28,42,43,44. The display of these proteins on the surface of liposomes may be stimulatory to B-cells, promoting cross-linking, expansion and maturation45. The CPQ platform also offers a simple way to display different vaccine antigens. Overall, the boosted effect from multivalent display and protein engineering efforts to improve the E antigen open exciting areas for dengue vaccine research.

Previously, a subunit vaccine containing soluble recombinant wild type (WT) E proteins from DENV1-4 was evaluated46,47,48. In a randomized phase I trial, this 3-dose tetravalent subunit vaccine (V180) produced DENV-specific neutralizing antibodies in flavivirus-naïve adults, but the tetravalent immunity decreased 14 months post dose 3, primarily due to a drop in DENV4 immunity to background level47. In the preclinical phase of this study, mice vaccinated with 10 µg of each DENV E repeatedly elicited low amounts of neutralizing antibodies to DENV448. Introducing these proteins in a tetravalent manner led to an overall decrease in DENV1-4 neutralization titers. Another study using DENV1-4 WT E adsorbed on PLGA nanoparticles also elicited anti-E neutralizing titer in mice, but the type-specific response was weaker for DENV1 and DENV249. These studies highlighted the promise of E subunit vaccines; however, they also indicated that the antigens and delivery systems could be improved for a more balanced immune response.

From our mouse study, the tetravalent CPQ-sE SC formulation appears to be a promising subunit vaccine formulation. Compared to the previous subunit vaccines using WT E, CPQ Tet SC not only elicited a strong neutralizing response to all 4 DENV serotypes but also robust TS neutralization to each virus. It is likely that the neutralization response can be further balanced by adjusting the dosage of the proteins per injection or changing the ratio of proteins coupled to CPQ liposome. This could be a significant advantage compared to tetravalent DENV vaccines based on live attenuated viruses where it is challenging to balance viral replication and the immune response. We did not directly assess protection by viral challenge of vaccinated mice because DENVs do not replicate in WT mice. While DENVs can replicate in interferon receptor deficient mice, immunodeficient mouse models are not suitable for evaluating vaccines. Instead, here we relied on binding and neutralization assays that utilized fully mature DENVs produced in VeroFurin cells, which more closely resemble DENVs circulating in humans and are more difficult to neutralize than partially mature DENVs produced in Vero cells without overexpression of furin50,51. Most previous studies have performed neutralization assays with partially mature virus produced in Vero cells.

Intriguingly, we observed high levels of cross-reactive binding Abs from mice vaccinated with mono- and bivalent formulations to DENV1 and DENV4 (Fig. 3D), but not to DENV2 and DENV3. We found that the mAb 4G2, which binds to the fusion loop of E, a conserved epitope across DENVs and flaviviruses, bind more tightly to DENV1 and 4 as opposed to DENV2 and 3 (Supplementary Fig. 7). This suggests that the fusion loop may be more exposed in DENV1and 4 than in the remaining serotypes, leading to a smaller difference between binding Ab titer between mono/bivalent CPQ-sE SC groups and CPQ Tet SC. Regardless, our depletion studies clearly demonstrate the role of TS Abs in virus neutralization.

Further studies are needed to establish that the tetravalent CPQ-sE SC formulation will be an effective and safe vaccine in humans. Mice cannot naturally be infected with DENV, and thus are poorly suited to these types of studies. Studies in non-human primates (NHPs) can be used to evaluate the durability of the Ab response and perform challenge experiments with relevant strains of DENV. In the absence of human clinical data, Ab responses in NHPs have been a good predictor of vaccine outcome. A challenge study in NHPs using the tetravalent vaccine Dengvaxia19 revealed that the amount of neutralizing Abs pre-challenge is negatively correlated to the magnitude of viremia, and that the vaccine only generates a robust TS response for DENV4, which has corroborated analysis of human sera post Dengvaxia administration52. For the tetravalent CPQ-sE SC formulation to be a viable vaccine, it will be important to establish that the robust type-specific responses are reproducible in NHPs and humans.

In summary, we performed the first multivalent immunization studies with sE SC variants that were computationally stabilized to increase expression yield and dimer stability. Mutations at the interface, hinge region and domain I core of the E protein had stabilizing effects in all four serotypes. Displaying the proteins on the surface of liposomes did not perturb binding to monoclonal Abs that are known to neutralize the virus, including epitopes that span across the dimer interface. In mice, the liposome conjugated proteins elicited a strong neutralizing response that is specific to the serotype of sE on the surface. This study provides a foundation for further exploration of this platform as a tetravalent DENV subunit vaccine.

Methods

Cells and viruses

Expi293 cells were used for protein expression. Monkey kidney epithelial Vero cells were used for virus neutralization assays. Soluble E protein sequences were based on DENV1 WestPac 74 (aa 1-394), DENV2 16681 (aa 1-394), DENV3 CH53489 (aa 1-392) and DENV4 TVP-376 (aa 1-394). Mature viruses produced in Vero cells overexpressing furin protease (VeroFurin cells) were used for binding and neutralization experiments50,51.

Protein expression and purification

DNA plasmids were amplified from DH5α cultures and purified using endotoxin-free DNA extraction kits (Macherey-Nagel) as previously described in ref. 28. Purified plasmids were then transfected into Expi293 cells using Expifectamine reagent according to the manufacturer’s guidelines for small scale (25–50 mL) or large scale (200–500 mL) production. Cells were grown in a 37 °C, 8% CO2 incubator at 130 rpm shaking. Media containing secreted proteins were harvested 64–72 h post transfection, and clarified by centrifugation at 3500 g (small scale expression) of 10,000 g (large scale expression) for 15 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.2 µm membrane and stored at 4 °C until purification.

Purification of sE was done using Nickel affinity column followed by gel filtration. In brief, Nickel Penta resin (Marvelgent) was equilibrated with 10 column volume (CV) PBS and incubated with protein media in batch binding mode for 1 h or overnight at 4 °C. Resin was washed with 6 CV (1 M tris-HCl, 0.5 M NaCl, 25 mM imidazole, pH 8.0), 1 CV PBS + 25 mM imidazole pH 7.4 and 1 CV PBS + 50 mM pH 7.4. Protein was eluted with 1x PBS + 500 mM imidazole pH 7.4, concentrated and buffer exchanged into PBS + 10% glycerol pH 7.4 buffer for storage.

Liposome synthesis

Materials

The following lipids were used to form CoPoP/PHAD/QS21 liposomes (CPQ); 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC, Corden # LP-R4-070), cholesterol (PhytoChol, Wilshire Technologies), synthetic monophosphoryl Hexa-acyl Lipid A, 3-Deacyl (PHAD-3D6A, Avanti Cat # 699 855), and QS-21 (Desert King). Cobalt-porphyrin-phospholipid (CoPoP) or porphyrin-phospholipid (PoP).

Liposome preparation

CPQ liposomes were prepared by an ethanol injection method, followed by nitrogen-pressurized lipid extrusion in a phosphate-buffer saline (PBS) carried out at 55 °C. Lipids were dissolved in 1 mL pre-heated 55 °C ethanol for 10 min, then 4 mL of pre-heated PBS were added and incubated at 55 °C for 10 min. The liposome extruder (Northern Lipids) was nitrogen pressurized and heated to 55 °C with a pressure of near 200–300 PSI. Then the liposomes were extruded through 200,100 and 80 nm membrane filters stack for 10 times, followed by dialyzing in PBS at 4 °C twice to remove ethanol. Later, liposomes were passed through a 0.2 μm sterile filter, and QS-21 (1 mg/mL) were admixed with liposomes, the final concentration was adjusted to 320 µg/mL of CoPoP, 128 µg/mL of PHAD and 128 µg/mL of QS21 and stored at 4 °C. Illustrations in the manuscript were generated with Adobe Illustrator (version 29). Protein images were generated with PyMol (version 1.20).

LPQ and CPQ liposome formulation

sE proteins were conjugated on CPQ liposomes following previously described protocols34,35. Specifically, the proteins were incubated with CPQ at a mass ratio 1:4 sE (monomer):CoPoP for 4 h at room temperature in the dark. LPQ liposomes were also incubated with proteins in the same manner using 1:4 sE (monomer):PoP mass ratio. After the incubation, the samples were protected from light and stored at 4 C.

CPQ-sE conjugation efficiency assessment by Ni binding and SDS-PAGE

25 µL sE or liposomes incubated with sE were incubated with either 5 µL 50% Ni resin slurry preequilibrated in PBS or PBS for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. The final protein concentrations were 40 µg/mL. The samples were mixed gently by pipetting every 10 min, and then transferred to a spin column and centrifuged for 1 min at 2000 g to separate the Ni beads and the solution. Ni beads were resuspended using 27.5 µL PBS into a new tube. Flowthrough fractions and Ni beads were analyzed by reducing SDS-PAGE to assess for the presence of unconjugated sE in solution.

Size analysis of LPQ and CPQ liposomes pre- and post- sE conjugation by dynamic light scattering (DLS)

DLS measurements were performed on a DynaPro Plate Reader II instrument in isothermal mode. Liposome samples were diluted in PBS to a final concentration of 100 µg/mL (Co)PoP. 2 mg/mL BSA in PBS was used as a control. The average hydrodynamic radius and polydispersity from 5 acquisitions (5 s each) was plotted.

Antibody binding to DENV1-4 sE and CPQ-sE by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Binding studies were done according to previously published protocols28. Soluble E proteins with a C-terminal His-tag (50 µL at 2 ng/µL) were directly coated on Nickel plates (Pierce, cat# 15142) in TBS buffer for 1 h at 37 °C. Plates were washed three times with 0.2% TBS Tween-20 (200 µL/well). Human anti-E monoclonal Abs were added to the plates at 2 ng/µL in blocking buffer (1x TBS buffer pH 7.4 containing 0.05% v/v Tween 20 and 3% non-fat dry milk) and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, 300 rpm (50 µL/well). Plates were washed then incubated with goat anti-human IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (AP) for 45 min at 37 °C. After a final wash, wells were developed with pNPP. Binding was correlated with absorbance at 405 nm. The assays were performed in duplicate.

To capture liposome formulated sE proteins (CPQ-sE), human anti-E antibody 1M7 was coated in a 96-well plate (Greiner, cat# 655061) overnight at 4 °C at 100 ng/well in 0.1 M NaHCO3 pH 9.6. Wells were blocked 1 h at 37 °C. CPQ-sE samples were diluted to 2 ng/µL sE in blocking buffer and added to the plate for 1 h at 37 °C, 300 rpm (50 µL/well). AP-conjugated human anti-E mAbs (using Abcam kit, cat# ap102850) were probed and detected by pNPP as described above. Additional binding studies were done with mouse mAb 4G2 as the capture Ab. For 4G2-captured samples, we probed binding with unlabeled human mAbs and goat anti-human IgG-AP (0.5 ng/µL).

Mouse immunogenicity studies

Female BALB/c mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and used at 9–10 weeks of age. For each immunization, mice were given an intramuscular injection (under no anesthesia) of 30 μL vaccine formulations in PBS in the thigh muscles of each hind limb, a total of 60 μL per mouse. For the monovalent formulations of DENV2 and DENV3 vaccines, each mouse received 2 μg sE (WT or stable dimer) formulated with LPQ or CPQ liposomes (n = 6). Bivalent formulations mixed 2 μg sE of DENV2 or DENV3 with the liposomes, and then mixed the liposomes (n = 6). For the tetravalent formulation,1 μg of each sE was mixed with CPQ liposomes, and then the liposomes were combined. Control groups included 2 μg DENV2 and 2 μg DENV3 sE+125 μg Alum (n = 6), CPQ or LPQ alone (n = 3). All groups were immunized with the same antigen formulation and dose at day 0 and 28, and serum samples were collected at indicated time points. Mice were euthanized at the end of studies via CO2 inhalation (7 liter/minute) till respiration ceases, followed by cervical dislocation.

Ethics statement

All experiments involving mice were performed according to the animal use protocol approved by the University of North Carolina Animal Care and Use Committee. The animal care and use related to this work complied with federal regulations: the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Animal Welfare Act, and followed the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Mouse serum binding ELISA to whole virus

The protocol is similar to the capture ELISA described above. Human 1M7 antibody was immobilized on Greiner plate (cat # 655061) in 0.1 M NaHCO3 buffer pH 9.6 (100 ng/well) overnight at 4 °C. All incubations on the following day were done at 37 °C with gentle shaking. Plates were blocked the next day with blocking buffer for 1 h. Mature viruses cultured in Vero Furin cells were captured on the plate for 1 h. Following washes, mouse serum was serially diluted in blocking buffer and added to the virus-captured plate (50 µL/well) and incubated for 1 h. Plates were washed, and anti-mouse IgG-AP (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the wells (50 µL/well) for a 45 min incubation. After a final wash, signal was developed using pNPP, monitoring for absorbance at 405 nm. Assays were performed in duplicates. The binding IgG titer was calculated as the midpoint dilution (Fig. 3) and area under the curve (Supplementary Fig. 4) of placebo-subtracted binding signal against serum dilutions. We attempted to depict this measurement as antibody concentration by comparison to the monoclonal antibody 4G2. However, as 4G2 binds differentially to DV1-4 (Supplementary Fig. 7), the concentration approximation is not representative of the true polyclonal sera. Full binding curves are available in Supplementary Figs. 8–11. All graphs in the manuscript were generated with GraphPad prism (version 10.1.2).

Focus reduction neutralization test (FRNT) by mouse sera

Vero cells were seeded the night before at a density of 20,000 cells/well and should be at 80–90% confluency on the day of the experiment. Vaccinated mouse serum was serially diluted in growth medium (1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco), 1% MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids Solution (Gibco), 1% L-Glutamine (Corning) in DMEM F12 (Gibco) containing 2% heat-inactivated FBS and incubated with virus for 1 h at 37 °C. The virus-serum mixture was then added onto cells (30 µL/well). After an hour incubation at 37 °C, the mixture was removed from cells and overlay media (OptiMEM (Gibco) + 2% HI FBS + 1% Anti-anti + 1% (w/v) carboxymethylcellulose (Sigma-Aldrich)) was added to the plate (180 µL/well). Foci were allowed to develop for a varying amount of time. The incubation time for mature DENV1 is 48 h, DENV2 is 52 h, DENV3 is 52 h and DENV4 is 44 h. After the infection incubation window, overlay media was flicked off from the wells. Cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% PFA for 30 min at room temperature, and subsequently washed with PBS.

To visualize foci on fixed cells, cells were permeabilized with 1x PERM ((10X PERM buffer was diluted in MilliQ water. 10X PERM: 1% of bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma)) for 10 min at room temperature (50 µL/well) or overnight (100 µL/well). 1 ng/µL 1M7 antibody in PERM + 5% milk was added to each well for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were washed with 1x PBS and incubated with 1:4000 anti-human IgG-HRP (Southern Biotech) for 1 h at 37 °C. After washing with PBS, 30 µL KPL True blue peroxidase substrate (SeraCare) was added to each well. After 15–30 min development at room temperature, wells were rinsed under a gentle stream of water and let dry. Wells were imaged using Immunospot camera and foci were counted using Viridot software53. Focus reduction was calculated as: % neutralization = (fociplacebo – fociserum)/fociplacebo*100%. Data plotted as average of duplicates and fitted to a sigmoidal dose-response curve. Full virus neutralization curves are available in Supplementary Figs. 8–11.

Depletion of sE-specific Ab from pooled polyclonal sera

sE proteins coupled to HisPur magnetic beads (ThermoFisher, cat# 88832) were used to pull out corresponding binding Abs. Beads were washed and equilibrated in PBS 0.05% Tween-20 containing 20 mM imidazole. Proteins were incubated with beads at 0.08:1 mass ratio in the same buffer. The final coupled beads were washed and stored in PBS pH 7.4.

To deplete anti-sE Abs from polyclonal serum, we used 32 µg proteins coupled to beads (400 µg beads) for each round of depletion. The beads were added to 96-well plate and washed with 100 µL PBS. A magnetic plate was used to pellet the beads and the plate was flicked to remove the solution. 170 µL 10-fold diluted pooled sera in PBS + 5% BSA was added to the corresponding depletion set up and beads were resuspended gently through pipetting. Any empty wells were filled with 150 µL PBS to minimize sample loss due to evaporation and the plate was carefully sealed. Sera and proteins were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C at 650–800 rpm in a thermomixer (Eppendorf) to ensure proper agitation. Once completed, the plate was spun at 4000 rpm for 5 min and a magnetic plate was used to separate the beads from the sera. Sera was carefully aspirated from the wells to avoid mixing with beads. A negative control for depletion was performed by coating beads with BSA at the same mass ratio mentioned above. Each serum sample was depleted 3 times with the antigens listed in Fig. 4B. Depletions were validated using Ni ELISA checking for binding of polyclonal serum with the depleting antigen (e.g. if serum was depleted with DENV2 sE SC, depletion is complete if there is no longer binding of serum to DENV2 sE SC in Ni ELISA, Supplementary Fig. 6). After depletions, sera were assessed for loss of neutralization at dilution factor 420 by normalizing the foci count to the control BSA-depleted sera. Experiments were performed in duplicates.

Data availability

The raw binding and neutralization data used to create Figs. 2, 3, 4, Supplementary Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 is available upon request from T.T.N.P and B.K. There are no datasets produced in this study appropriate for deposition in a public database. The protein sequences of the engineered E proteins are included in the supplementary material, but not deposited in Uniprot as Uniprot is not appropriate for engineered protein sequences.

Materials availability

Any requests for materials should be addressed to T.T.N.P. and B.K.

References

Bhatt, S. et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 496, 504–507 (2013).

Beltramello, M. et al. The human immune response to dengue virus is dominated by highly cross-reactive antibodies endowed with neutralizing and enhancing activity. Cell Host Microbe 8, 271–283 (2010).

Wahala, W. M. P. B. & de Silva, A. M. The human antibody response to dengue virus infection. Viruses 3, 2374–2395 (2011).

De Alwis, R. et al. Dengue viruses are enhanced by distinct populations of serotype cross-reactive antibodies in human immune sera. PLoS Pathog. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004386 (2014).

Nivarthi, U. K. et al. Longitudinal analysis of acute and convalescent B cell responses in a human primary dengue serotype 2 infection model. EBioMedicine 41, 465–478 (2019).

Young, E. et al. Identification of dengue virus serotype 3 specific antigenic sites targeted by neutralizing human antibodies. Cell Host Microbe 27, 710–724.e7 (2020).

Nivarthi, U. K. et al. Mapping the human memory B cell and serum neutralizing antibody responses to dengue virus serotype 4 infection and vaccination. J. Virol. 91, 1–14 (2017).

Sangkawibha, N. et al. Risk factors in dengue shock syndrome: a prospective epidemiologic study in Rayong, Thailand. I. the 1980 outbreak. Am. J. Epidemiol. 120, 653–669 (1984).

Halstead, S. B., Nimmannitya, S. & Cohen, S. N. Observations related to pathogenesis of dengue hemorrhagic fever. IV. Relation of disease severity to antibody response and virus recovered. Yale J. Biol. Med. 42, 311–328 (1970).

Vaughn, D. W. et al. Dengue viremia titer, antibody response pattern, and virus serotype correlate with disease severity. J. Infect. Dis. 181, 2–9 (2000).

Burke, D. S., Nisalak, A., Johnson, D. E. & Scott, R. M. A prospective study of dengue infections in Bangkok. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 38, 172–180 (1988).

Morrone, S. R. & Lok, S. M. Structural perspectives of antibody-dependent enhancement of infection of dengue virus. Curr. Opin. Virol. 36, 1–8 (2019).

Dejnirattisai, W. et al. Cross-reacting antibodies enhance dengue virus infection in humans. Science. 328, 745–748 (2010).

Hadinegoro, S., Arredondo-Garcia, J., Capeding, M. & Al, E. Efficacy and long-term safety of a dengue vaccine in regions of endemic disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 1195–1206 (2015).

Patel, S. S. et al. An open-label, phase 3 trial of TAK-003, a live attenuated dengue tetravalent vaccine, in healthy US adults: immunogenicity and safety when administered during the second half of a 24-month shelf-life. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 19, 2254964 (2023).

White, L. J. et al. Defining levels of dengue virus serotype-specific neutralizing antibodies induced by a live attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine (Tak-003). PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 15, 1–15 (2021).

Guy, B., Briand, O., Lang, J., Saville, M. & Jackson, N. Development of the sanofi pasteur tetravalent dengue vaccine: one more step forward. Vaccine 33, 7100–7111 (2015).

Saranya, S. et al. Effect of dengue serostatus on dengue vaccine safety and efficacy. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 327–340 (2018).

Barban, V. et al. Improvement of the dengue virus (DENV) nonhuman primate model via a reverse translational approach based on dengue vaccine clinical efficacy data against DENV-2 and -4. J. Virol. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00440-18 (2018).

Murphy, B. R. & Whitehead, S. S. Immune response to dengue virus and prospects for a vaccine. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 29, 587–619 (2011).

de Silva, A. M. & Harris, E. Which dengue vaccine approach is the most promising, and should we be concerned about enhanced disease after vaccination?: the path to a dengue vaccine: learning from human natural dengue infection studies and vaccine trials. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.03.040 (2018).

Kuhn, R. J. et al. Structure of dengue virus: implications for flavivirus organization, maturation, and fusion. 108, 717–725, (2002)

Zhang, W. et al. Visualization of membrane protein domains by cryo-electron microscopy of dengue virus. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 907–912 (2003).

Dejnirattisai, W. et al. A new class of highly potent, broadly neutralizing antibodies isolated from viremic patients infected with dengue virus. Nat. Immunol. 16, 170–177 (2015).

Gallichotte, E. N. et al. A new quaternary structure epitope on dengue virus serotype 2 is the target of durable type-specific neutralizing antibodies. MBio 6, e01461-15 (2015).

Li, L. et al. Potent neutralizing antibodies elicited by dengue vaccine in rhesus macaque target diverse epitopes. PLoS Pathog. 15, 1–29 (2019).

Kudlacek, S. T. et al. Physiological temperatures reduce dimerization of dengue and Zika virus recombinant envelope proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 8922–8933 (2018).

Kudlacek, S. T. et al. Designed, highly expressing, thermostable dengue virus 2 envelope protein dimers elicit quaternary epitope antibodies. Sci. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abg4084 (2021).

Phan, T. T. N. et al. A conserved set of mutations for stabilizing soluble envelope protein dimers from dengue and Zika viruses to advance the development of subunit vaccines. J. Biol. Chem. 298, 102079 (2022).

Lovell, J. F. et al. Porphysome nanovesicles generated by porphyrin bilayers for use as multimodal biophotonic contrast agents. Nat. Mater. 10, 324–332 (2011).

Shao, S. et al. Functionalization of cobalt porphyrin-phospholipid bilayers with his-tagged ligands and antigens. Nat. Chem. 7, 438–446 (2015).

Huang, W. C. et al. A malaria vaccine adjuvant based on recombinant antigen binding to liposomes. Nat. Nanotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-018-0271-3 (2018).

Coccia, M. et al. Cellular and molecular synergy in AS01-adjuvanted vaccines results in an early IFNγ response promoting vaccine immunogenicity. npj Vaccines. 2, 25 (2017).

Huang, W. C. et al. Vaccine co-display of CSP and Pfs230 on liposomes targeting two Plasmodium falciparum differentiation stages. Commun. Biol. 5, 1–13 (2022).

Federizon, J. et al. Immunogenicity of the Lyme disease antigen OspA, particleized by cobalt porphyrin-phospholipid liposomes. Vaccine 38, 942–950 (2020).

He, X. et al. Immunization with short peptide particles reveals a functional CD8 + T-cell neoepitope in a murine renal carcinoma model. J. Immunother. Cancer 9, 1–12 (2021).

Huang, W.-C. et al. SARS-CoV-2 RBD neutralizing antibody induction is enhanced by particulate vaccination. Adv. Mater. 32, e2005637 (2020).

Lovell, J. F. et al. Interim analysis from a phase 2 randomized trial of EuCorVac-19: a recombinant protein SARS-CoV-2 RBD nanoliposome vaccine. BMC Med. 20, 462 (2022).

Lovell, J. F. et al. One-year antibody durability induced by EuCorVac-19, a liposome-displayed COVID-19 receptor binding domain subunit vaccine, in healthy Korean subjects. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 138, 73–80 (2024).

Rouvinski, A. et al. Recognition determinants of broadly neutralizing human antibodies against dengue viruses. Nature 520, 109–113 (2015).

Smith, S. A. et al. The potent and broadly neutralizing human dengue virus-specific monoclonal antibody 1C19 reveals a unique cross-reactive epitope on the bc loop of domain II of the envelope protein. MBio 4, 1–12 (2013).

Metz, S. W. et al. Oligomeric state of the ZIKV E protein defines protective immune responses. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12677-6 (2019).

Slon-Campos, J. L. et al. A protective Zika virus E-dimer-based subunit vaccine engineered to abrogate antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue infection. Nat. Immunol. 20, 1291–1298 (2019).

Thomas, A. et al. Dimerization of dengue virus E subunits impacts antibody function and domain Focus. J. Virol. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00745-20 (2020).

Jennings, G. T. & Bachmann, M. F. Designing Recombinant vaccines with viral properties: a rational approach to more effective vaccines (2007).

Manoff, S. B. et al. Preclinical and clinical development of a dengue recombinant subunit vaccine. Vaccine 33, 7126–7134 (2015).

Manoff, S. B. et al. Immunogenicity and safety of an investigational tetravalent recombinant subunit vaccine for dengue: results of a Phase I randomized clinical trial in flavivirus-naïve adults. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 15, 2195–2204 (2019).

Coller, B.-A. G., Clements, D., Bett, A. J., Sagar, S. & ter Meulen, J. The Development of recombinant subunit envelope-based vaccines to protect against dengue virus induced disease. Vaccine 29, 7267–7275 (2011).

Metz, S. W. et al. Precisely molded nanoparticle displaying DENV-E proteins induces robust serotype-specific neutralizing antibody responses. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10, 1–17 (2016).

Raut, R. et al. Dengue type 1 viruses circulating in humans are highly infectious and poorly neutralized by human antibodies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA116, 227–232 (2019).

Tse, L. V. et al. Generation of mature DENVs via genetic modification and directed evolution. MBio 13, e0038622 (2022).

Henein, S. et al. Dissecting antibodies induced by a chimeric yellow fever-dengue, live-attenuated, tetravalent dengue vaccine (CYD-TDV) in naive and dengue-exposed individuals. J. Infect. Dis. 215, 351–358 (2017).

Katzelnick, L. C. et al. Viridot: An automated virus plaque (immunofocus) counter for the measurement of serological neutralizing responses with application to dengue virus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12, e0006862 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank John Forsberg at the UNC Protein expression & purification core for providing WT proteins. This study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (R01AI161025 and 1U19AI181960).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.T.N.P., A.d.S and B.K. conceptualized the work. S.T., M.H. and G.P.A. performed animal studies. T.T.N.P., M.H. and G.P.A. biochemically characterization of proteins. W.H. and J.L. synthesized liposomes. T.T.N.P., D.T., and R.S. contributed to serological analysis. T.T.N.P. created the first draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

W.H. and J.L. hold interest in POP Biotechnologies, which is commercializing the CPQ liposome technology employed in this study. T.P., A.S., and B.K. are inventors on a patent application describing amino acid mutations that stabilize the E dimer from dengue virus. These mutations are used in this study. All other authors describe no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Phan, T.T.N., Thiono, D.J., Hvasta, M.G. et al. Multivalent administration of dengue E dimers on liposomes elicits type-specific neutralizing responses without immune interference. npj Vaccines 10, 119 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01179-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01179-w