Abstract

In humans, Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) infection typically presents as a self-limiting febrile illness but can cause severe complications. Neurological disease manifestations are particularly concerning as they are associated with increased mortality and long-term morbidity. This study demonstrated that vaccination with live attenuated RVFV was effective in preventing central nervous system (CNS) disease in the CC057/Unc mouse model of late-onset RVF encephalitis. Vaccine candidates (ΔNSs and ΔNSsΔNSm) were safe and immunogenic and elicited both RVFV-specific humoral and cellular immunity. Vaccinated mice survived percutaneous wild-type (WT) RVFV challenge and were protected from CNS disease. Naïve mice that received passive transfer of serum from vaccinated animals 2 days post-WT challenge were protected against late-onset encephalitis. These data demonstrate that humoral immunity is sufficient to protect against RVF encephalitis in CC057/Unc mice and suggest the potential of these vaccine candidates to prevent CNS disease in humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prevalent in Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, Rift Valley Fever virus (RVFV) is a mosquito-borne virus that infects humans and livestock causing Rift Valley Fever (RVF)1. In humans, RVF typically presents as a self-limiting febrile illness but in a subset of individuals can cause severe complications such as hepatitis, hemorrhagic fever, or encephalitis2. The majority of what is known about RVF disease manifestations in humans stems from case reports and studies during major outbreaks when affected individuals sought clinical care. During the outbreak in Saudi Arabia in the early 2000s, neurological manifestations were reported in 17.3% of cases and included symptoms such as confusion, lethargy, coma, and ataxia3. Typically, human cases of RVF encephalitis occur in a biphasic manner whereby patients will first experience febrile illness and begin to show neurological signs approximately one week later2. Patients with neurological manifestations are more likely to succumb to the disease. Additionally, patients can be left with long-term cognitive and physical impairments after surviving central nervous system (CNS) disease4. To prevent such devastating outcomes, investigations into how RVFV infection causes CNS disease and assessments on preventative measures for RVF CNS disease are required.

Most traditional mouse strains rapidly succumb to lethal hepatitis 3–5 days post percutaneous wild-type (WT) challenge5 while infection of rodents with RVFV administered intranasally or via aerosol leads to encephalitis6,7,8,9. The later routes of infection might be reflective of mucosal exposure following contact to blood and tissues from infected livestock as might occur during the butchering process. Identification of a reliable RVF CNS disease model following percutaneous exposure has been challenging and murine models have required the manipulation of either the host or the virus to achieve this10. In 2022, it was reported that the CC057/Unc mouse strain from the Collaborative Cross (CC) resource consistently developed late-onset encephalitis upon WT percutaneous infection11. When challenged with WT RVFV (ZH501) via foot pad injection (to mimic mosquito bite), CC057/Unc mice developed lethal late-onset encephalitis with a mean survival time of 11–12 days. CC057/Unc mice displayed a biphasic pattern of disease whereby early during infection, self-limiting viral replication occurred in the liver and about one-week post-challenge (day 7), viral RNA was detectable in CNS tissues and brain lesions were noted. Clinical signs in this model include progressive weight loss, circling, ataxia, seizures, hind limb paralysis, and eye deviation. Taken together, CC057/Unc mice serve as a model to investigate means to prevent RVF CNS disease.

Prevention of RVF disease has mostly focused on the development and use of vaccines. Several vaccines have advanced significantly through preclinical studies or reached the clinical trial stage, including the adenovirus vectored vaccine ChAdOX1, and the live attenuated RVFV vaccines RVFV-4s, MP-12, and DDVax12. However, none have yet been licensed for human use. The DDVax vaccine was generated through a reverse genetics system and lacks both nonstructural proteins NSs and NSm. NSs is a major virulence factor encoded on the S segment of the virus that suppresses innate immune responses13,14, whereas NSm is encoded on the M segment of the virus and has been implicated in viral replication in mosquitos15. In mice, RVFV strains lacking NSs maintain pathogenicity when administered via intranasal or intracranial routes, but viruses lacking NSm maintain pathogenicity regardless of route suggesting that NSs is the more prominent virulence determinant in mouse models.

In this study, the footpad route of virus inoculation was used to mimic infection via mosquito bite and live attenuated RVFVs that either lacked NSs (ΔNSs) or both NSs and NSm (ΔNSsΔNSm) were evaluated as vaccines to prevent RVF encephalitis following WT challenge in CC057/Unc mice. Both vaccines protected mice from disease and elicited humoral and cellular immunity. Moreover, humoral immunity alone was sufficient to protect against lethal CNS disease.

Results

Vaccination with live attenuated RVFV generates robust humoral immunity and protects CC057/Unc mice against lethal RVF encephalitis

Previous work in C57BL/6 mice showed that live attenuated RVFV can serve as a vaccine to protect against lethal hepatitis following WT RVFV challenge16,17. To test this application in the CC057/Unc model of late-onset encephalitis, groups of mice were vaccinated with live attenuated RVFV lacking either the nonstructural protein NSs (ΔNSs) or both nonstructural proteins NSs and NSm (ΔNSsΔNSm) at a dose of 2 × 105 TCID50 via left foot pad injection. The control group (Mock) received an injection of sterile PBS. Twenty-eight days post-vaccination, mice were challenged with 2 TCID50 of WT RVFV also via left foot pad injection and monitored for survival until day 56 post-vaccination (Fig. 1A). As expected, Mock vaccinated animals succumbed to infection with a median survival time of 10.5 days post WT challenge. High amounts of viral RNA were detected in the brain and lower amounts of viral RNA were detected in the liver and spleen via qRT-PCR, consistent with the late-onset encephalitis phenotype (Fig. 1B, C). Mock vaccinated animals had no detectable anti-RVFV specific antibodies pre-challenge as determined by ELISA or neutralization assay (Fig. 1D, E), but Mock vaccinated animals had both total anti-RVFV and anti-NSs specific antibodies at the time of euthanasia (Fig. 1F, G). These findings indicate that Mock vaccinated animals generated an immune response to WT RVFV infection that did not protect them from RVF encephalitis, which is consistent with previous findings in the CC057/Unc model11. In contrast, mice that were vaccinated with either of the two live attenuated RVFV prior to WT challenge survived and had no detectable viral RNA in liver, spleen or brain by qRT-PCR (Fig. 1B, C) demonstrating that vaccination conveyed protection from RVF encephalitis. Vaccinated animals displayed robust total anti-RVFV antibody production pre-challenge that did not increase by the time of euthanasia as determined by ELISA and neutralization assay (Fig. 1D–G). No significant differences in protection or antibody response from ΔNSs or ΔNSsΔNSm vaccines were observed. Importantly, vaccinated animals had no detectable anti-NSs specific antibodies at the time of euthanasia, suggesting that vaccination could be eliciting sterilizing immunity since both live attenuated vaccines lack the NSs protein, but proving this would require further study (Fig. 1F). Together, these data demonstrate that vaccination with live attenuated RVFV protects CC057/Unc mice from RVF encephalitis.

Mice (n = 3 to 4 per experimental group) were vaccinated with 2 x 105 TCID50 of ΔNSs, ΔNSsΔNSm RVFV or mock-vaccinated (PBS) and then challenged at 28 days post-vaccination with 2 TCID50 WT RVFV, both via foot pad injection (A). Animals were monitored for survival, and survivors were euthanized on day 56 post-vaccination (B). Terminal viral RNA loads in liver, spleen and brain were measured (C). The dotted line represents the limit of detection (LOD) of the assay, and values below LOD are plotted at LOD (4.1 × 106 copies/g). The endpoint titers of total RVFV-specific or RVFV NSs-specific antibodies by ELISA or neutralization titer were measured pre-challenge (D, E) and at time of euthanasia (F, G). The LOD is depicted as a dotted line at 100 for ELISA and 40 for focus reduction neutralization test (FRNT80). Negative values were plotted at 50 (ELISA) and 20 (FRNT80), respectively. Survivors are displayed as open symbols, and graphs depict the geometric mean and standard deviation (SD) for each group. The timeline (A) was generated with BioRender.com.

Administration of lower doses (20 and 2000 TCID50) of live attenuated RVFV ΔNSsΔNSm was sufficient for survival after WT challenge (Fig. 2A, B). In contrast to animals receiving the highest vaccine dose (Fig. 1C), animals receiving the vaccine at lower doses had detectable viral RNA for the RVFV L segment (encodes viral polymerase L) in the liver, spleen and brain (Fig. 2C) at the time of euthanasia. In addition, qRT-PCR for the RVFV S segment (encodes N and NSs) with primers specific to NSs showed detectable amounts of viral RNA suggesting infection of these tissues with WT RVFV (Fig. 2D) when animals received lower doses of the ΔNSsΔNSm vaccine. Notably, the virus could not be isolated from brain tissues in these animals (Fig. 2C, marked with “x”) compared to a mock infected animal (Fig. 2C, marked with check) and these animals did not display any clinical signs of disease. Moreover, the total RVFV-specific antibody responses (Fig. 2E–H) were comparable to those in animals that received the higher dose (Fig. 1D–G) and no RVFV NSs-specific antibodies were detected (Fig. 2G). These data suggest that receiving a lower vaccine dose is sufficient for survival in this experimental set-up but may not prevent WT RVFV entry into the brain.

Mice (n = 3 per experimental group) were vaccinated with either 20 TCID50 or 2000 TCID50 of ΔNSsΔNSm RVFV and then challenged at 28 days post-vaccination with 2 TCID50 WT RVFV, both via foot pad injection (A). Animals were monitored for survival, and survivors were euthanized on day 56 post-vaccination (B). Terminal viral RNA loads in liver, spleen and brain were measured for the L and S segment for vaccinated animals and samples from Mock infected animals from Fig. 1 were included for comparison (C, D). The dotted lines represent the LOD of the assays (L segment: 3.6 x 106 copies/g; S segment: 8 x 106 copies/g). Data points marked with x indicate that no virus could be isolated from brain tissues while the data point with the check indicates that virus could be isolated from brain tissue (C). The endpoint titers of total RVFV-specific or RVFV NSs-specific antibodies by ELISA or neutralization titers were measured pre-challenge (E, F) and at the time of euthanasia (G, H). The LOD is depicted as a dotted line at 100 for ELISA and 40 for FRNT80. Negative values were plotted at 50 for ELISA. Survivors are displayed as open symbols, and graphs depict the geometric mean and SD for each group. The timeline (A) was generated using BioRender.com.

Vaccination with high dose live attenuated RVFV elicits virus-specific T cells in CC057/Unc mice

Humoral immunity is an important part of vaccine-induced adaptive immunity, but several lines of evidence have suggested that T cells can also play a role in preventing RVF disease7,17,18,19. To quantitate virus-specific T cells in vaccinated CC057/Unc mice, splenocytes from vaccinated and vaccinated/WT challenged animals were tested in an interferon gamma (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay using peptide pools that represent the viral structural proteins: nucleoprotein (N) and glycoproteins (Gn and Gc). The reactivity to RVFV N was highest across groups and varied from 50 to 130 spot-forming units (SFUs, 0.05 to 0.13% of input cells), whereas the frequency of virus-specific T cells recognizing Gn or Gc was lower and ranged from 0 to 13 SFUs (Fig. 3A). Since both CD4 T cells (helper) and CD8 T cells (cytotoxic) have been implicated in conveying protection against WT RVFV challenge7,16,18,19, an ex vivo peptide stimulation assay followed by flow cytometry was carried out to quantitate virus-specific T cells. The gating strategy is provided in Fig. 3B. Vaccination with live attenuated RVFV generated both CD4+ as well as CD8+ RVFV-specific T cells independent of subsequent WT challenge (Fig. 3C, D). CC057/Unc mice that were vaccinated with ΔNSs displayed overall higher percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ cells compared to ΔNSsΔNSm vaccinated animals, but this was only statistically significant for N-specific CD8+ cells (Fig. 3D). Animals that were vaccinated with ΔNSsΔNSm and then challenged with WT RVFV had significantly lower percentages of Gn2, Gc1, and Gc2-specific CD4+ cells compared to ΔNSsΔNSm vaccinated animals (Fig. 3C). In a previous report, C57BL/6 mice infected with ΔNSs showed between 0.4 to 1.17% IFN-γ-+/CD44+ CD4 T cells and between 0.5 and 2.34% IFN-γ-+/CD44+ CD8 T cells at time of euthanasia on day 36 post-infection in an ex vivo peptide stimulation assay16. These percentages are similar to those observed in CC057/Unc mice vaccinated with ΔNSs; there was a trend towards a higher percentage of N-specific CD8 T cells in CC057/Unc mice, but this might be attributable to technical differences (mega pools used in CC057/Unc mice versus a subset of defined peptides used in C57BL/6 mice). Overall, these data indicate that vaccination with high dose live attenuated RVFV elicits virus-specific T cells in CC057/Unc that may contribute to vaccine mediated protection from RVF neurological disease. This is especially relevant given the finding of WT virus entry into the brains of some animals following challenge of mice vaccinated with low dose ΔNSsΔNSm (Fig. 2). Since low and high dose vaccination led to similar levels of humoral immunity, it suggests the possibility that T cell-mediated activity augments vaccine-mediated protection in the high dose scenario.

Splenocytes were collected from vaccinated mice (day 28) or vaccinated and WT RVFV challenged mice (day 56) and tested in ex vivo peptide stimulation assays (n = 4 per group). The number of RVFV-specific T cells in total splenocytes was assessed by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay, expressed as the number of spot-forming units (SFUs) per 1x105 splenocytes for RVFV N, Gn (Gn1 + Gn2), and Gc (Gc1 + Gc2) (A). The gating strategy for flow cytometry is displayed (B). The percentage of RVFV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was determined by flow cytometry by staining for CD44 and IFN-γ (C, D). Graphs depict mean and SD per group. Statistical comparison was performed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney test with *p < 0.05.

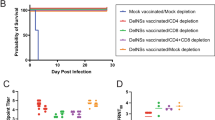

Humoral immunity is sufficient to protect CC057/Unc mice against RVF encephalitis but is dependent on time and dose

Humoral immunity particularly in the form of neutralizing antibodies has been recognized as an important vaccine-mediated correlate of protection for RVF17,20,21. Thus, a series of passive transfer (PT) experiments were carried out to establish whether antibodies alone could protect CC057/Unc mice against RVF encephalitis. First, mice were challenged with 2 TCID50 of WT RVFV via left foot pad injection. Immune serum (from a pool of ΔNSs vaccinated animals, see Materials & Methods) was then administered once per mouse group via a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection on day (D) 2 through D7 post-infection. Mice were monitored for survival until day 28 post-challenge. For the control group, animals received normal mouse serum i.p. at D2 (Fig. 4A). Animals that received PT of immune serum on D2 survived infection until the end of the study as compared to the D2 control which had a median survival of 11 days (Fig. 4B). Administration of immune serum at D3, D4, and D5 did not protect all animals but resulted in statistically significant prolonged survival time compared to the D2 control, with median survival of 16.5 days (D3), 21 days (D4), and 14 days (D5), respectively (Fig. 4B). In contrast, PT treatment at D6 and D7 did not result in significantly increased survival with only one animal in each group surviving until the end of the experiment. These results were consistent with measurements of viral RNA at the time of euthanasia in the liver, spleen and brain via qRT-PCR (Fig. 4C), where survivors (open circle symbols) displayed lower levels of viral RNA compared to animals that succumbed to disease (closed circle symbols). Similarly to findings in the dose-down vaccination experiment (Fig. 2D), the virus could not be isolated from brain tissues of the thirteen survivors (Fig. 4C, marked with “x”) despite detectable viral RNA level of the S segment in the brain in a subset of animals (Fig. 4D). Animals that required euthanasia before the end of the experiment had the highest viral RNA loads in brain tissue and the virus could be isolated from the tissue (Fig. 4C, marked with check) consistent with the late-onset encephalitis phenotype. Notably, there was a statistically significant linear relationship (p = 0.0278 via nonparametric Spearman correlation with R = -0.9) between mean survival time and mean viral load such that the longer an animal lived, the lower the amount of detectable viral RNA in the tissues. RVFV-specific antibodies were assessed via ELISA and neutralization assay post-PT and at time of euthanasia. As expected, there were no detectable total anti-RVFV specific antibodies in the D2 normal mouse serum group compared to the immune serum groups (Fig. 4E, F). The increase in ELISA endpoint titers (Fig. 4E, G) for the D5, D6 and D7 groups could be due to animals beginning to generate their own antibody response to WT RVFV infection. At the time of euthanasia, all groups had measurable total anti-RVFV antibodies (Fig. 4G, H). Importantly, all survivors except for two animals in the D2 group had detectable anti-NSs antibodies (Fig. 4G, open symbols) suggesting that survivors receiving PT of immune serum after D2 generated an antibody response to the WT infection since the immune serum originated from ΔNSs vaccinated animals.

Mice (n = 3 to 9 per experimental group) were challenged with 2 TCID50 WT RVFV via foot pad injection and later received passive transfer (PT) of normal or immune mouse serum via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection at indicated timepoints (A). Animals were monitored for survival and survivors were euthanized on day 28 post-infection (B). Statistical comparison was performed using Mantel-Cox test with *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ns- not significant. Terminal viral RNA loads in liver, spleen and brain were measured for the L segment for all animals (C) and for the S segment for the survivors (D). The dotted lines represent the LOD of the assays (L segment: 1.1 × 106 copies/g; S segment: 1 × 108 copies/g). Data points marked with x indicate that no virus could be isolated from brain tissues while the data point with the check indicates that virus could be isolated from brain tissue (C). The endpoint titers of total RVFV-specific (all animals) or RVFV NSs-specific (survivors only) antibodies by ELISA or neutralization titers were measured one day following i.p. injection (E, F) and at time of euthanasia (G, H). The limit of LOD is depicted as a dotted line at 100 for ELISA and 40 for FRNT80. Negative values were plotted at 50 (ELISA) and 20 (FRNT80), respectively. Survivors are displayed as open symbols, and graphs depict the geometric mean and SD for each group. The timeline (A) was generated using BioRender.com.

Protection from RVFV-mediated encephalitis was also evaluated when animals received diluted immune serum (at 1:20, 1:100 and 1:500 in sterile PBS) at D2 (Fig. 5A). Compared to PT D2 normal serum animals (Fig. 4), all animals receiving an immune serum dilution of 1:20 were protected from late-onset encephalitis, whereas protection declined with higher dilutions suggesting dose-dependency (Fig. 5B). As observed in the first PT experiment, viral RNA of the L and S segments were detectable in the brains of survivors (Fig. 5C, D, open symbols), yet live virus could not be isolated from these tissues. RVFV-specific antibodies were low, post-PT in all groups (Fig. 5E, F) but after WT challenge were significantly higher at the time of euthanasia (Fig. 5G, H). Moreover, all animals had NSs-specific antibodies (Fig. 5G) suggesting a de novo immune response to WT RVFV infection. In summary, these results demonstrate that humoral immunity is sufficient to protect CC057/Unc mice against RVF CNS disease in a time and dose-dependent manner.

Mice (n = 3 per experimental group) were challenged with 2 TCID50 WT RVFV via foot pad injection and later received passive transfer of various dilutions (1:20, 1:100, 1:500) of immune mouse serum via i.p. injection at 2dpi (A). Animals were monitored for survival, and survivors were euthanized on day 28 post-infection (B). Statistical comparison to PT D2 normal serum animals (Fig. 4) was performed using Mantel-Cox test with *p < 0.05, ns- not significant. Terminal viral RNA loads in liver, spleen and brain were measured for the L and S segment (C, D). The dotted lines represent the LOD of the assays (L segment: 3.9 × 105 copies/g; S segment: 4.7 × 106 copies/g). Data points marked with x indicate that no virus could be isolated from brain tissues (C). The endpoint titers of total RVFV-specific (all animals) or RVFV NSs-specific (survivors only) antibodies by ELISA or neutralization titers were measured one day following i.p. injection (E, F) and/or at the time of euthanasia (G, H). The limit of detection (LOD) is depicted as a dotted line at 100 for ELISA, 20 for post-PT FRNT80,50 and 40 for terminal FRNT80. Negative values were plotted at 50 for ELISA, 10 for post-PT FRNT80,50 and 20 for terminal FRNT80. Survivors are displayed as open symbols, and graphs depict the geometric mean and SD for each group. The timeline (A) was generated using BioRender.com.

Discussion

The spectrum of RVF disease manifestations in humans necessitates that vaccine candidates are evaluated regarding safety and efficacy in animal models that mimic these diverse manifestations. Murine models of RVF CNS disease have historically required the use of attenuated RVFV in immunocompromised animals and/or an intranasal/intracranial administration of the virus into the host. One exception is BALB/c mice, which usually develop acute lethal hepatitis but occasionally survive longer and develop lethal encephalitis upon WT challenge22, but even this model is limited by its lack of a consistent phenotype. To date, CC057/Unc mice are the only consistent murine model of late-onset encephalitis following percutaneous WT RVFV challenge that does not require experimental manipulation of the host or virus10. Thus, this study took advantage of the CC057/Unc mouse model to evaluate two live attenuated RVFV vaccines for protection against RVF CNS disease. Limitations of this study include the fact that CC057/Unc mice have small male-dominant litters leading to the use of small samples sizes in some groups, however, in most cases the small sample size was compensated for by the large effect size. Both attenuated vaccine candidates tested here generated robust virus-specific humoral and cellular immunity and provided protection from RVF CNS disease following WT challenge. Additionally, humoral immunity was shown to be sufficient for protection.

Vaccine efficacy and longevity are frequently assessed through measures of virus-specific neutralizing antibodies23. Often this is due to the technical simplicity of measuring neutralizing antibodies, but in some cases, neutralizing antibodies have also been shown not only to be an easily measurable marker of immunogenicity but also a mechanistic correlate of protection. Three different live attenuated or viral vectored RVFV vaccine platforms have been tested to date in humans12. These and other candidates have been evaluated for the generation of neutralizing antibodies and subsequent protection from RVFV challenge in the context of murine models that largely represent acute lethal hepatitis12. For example, single-dose vaccination with RVFV four-segmented genome (RVFV-4s) in female BALB/c mice resulted in virus neutralization titer (VNT) 50% endpoint titer between 1024 and 2048 at 3 weeks post-vaccination24; single-dose vaccination with adenovirus-vectored RVFV (ChAdOx1-GnGc) in female BALB/c mice showed maximum VNT50 of 64 (without adjuvant) and 128 (with adjuvant) at 8 weeks post-vaccination25; single-dose vaccination with MP-12 in female CB6F1 (F1 cross of BALB/c and C57BL/6) mice had plaque-reducing neutralization titers of 80% (PRNT80) of 80/320/400 at 2/8/16 weeks post-vaccination26, and single-dose vaccination with ΔNSs in C57BL/6 mice resulted in FRNT80 between 1280 and 10240 at 3 weeks post-vaccination17. In all these studies, mice were protected against lethal RVFV disease if they received the vaccine prior to challenge. Similarly, data presented in this study showed that single high dose vaccination with either ΔNSs or ΔNSsΔNSm in CC057/Unc mice resulted in a robust antibody response with FRNT80 between 1280 and 10240 at 4 weeks post-vaccination that was associated with protection from lethal CNS disease upon WT challenge. Moreover, the high level of neutralizing antibody titers and no detection of viral RNA in the tissues following the high dose of live attenuated RVFV suggests the possibility of sterilizing immunity. In contrast, while administration of lower vaccine doses protected from RVF clinical CNS disease after WT challenge, WT viral RNA was detectable in the brain in a subset of survivors. Since this study only used three doses, future work with doses in between could be tested to identify the minimum vaccine dose that is required to prevent WT viral RNA replication upon challenge. Together, these data indicate that higher doses are required to provide complete protection and suggest that other aspects of adaptive immunity, such as T cells, may play a contributory role. A single high dose may also be sufficient to protect CC057/Unc mice over longer periods of time, and such questions could be addressed in future studies.

As part of the adaptive immune response, humoral immunity has been implicated as a major correlate of protection in RVF murine models. For example, BALB/c mice that received PT of immune serum from human volunteers vaccinated with MP-12 were generally protected from disease when neutralizing antibody titers (determined by PRNT80) were in the range of 1:5 to 1:20 (75–100% survival)21. Moreover, it was demonstrated that PT of serum from RVFV-4s vaccinated animals delayed early-onset of hepatitis in BALB/c mice compared to controls20, and PT of serum from ΔNSs vaccinated animals provided protection from lethal hepatic disease in C57BL/6 mice17. In agreement, our study demonstrated that PT of immune serum provided 100% protection from lethal CNS disease if it was administered before D3 post WT challenge. Interestingly, all survivors receiving PT after D2 had detectable RVFV NSs-specific antibodies at the time of euthanasia indicating that WT viral replication had occurred and elicited an antibody response. This further suggests that complete neutralization (i.e., sterilizing immunity) may not be a requirement to protect CC057/Unc mice against WT infection but instead the naïve host immune system could complement vaccine-mediated immunity to provide protection. Strikingly, one animal survived when receiving PT as late as 7 days post-challenge, the timepoint at which viral RNA is first detected in the brain of CC057/Unc mice11 and a subset of PT survivors had S segment viral RNA in the brain tissue at euthanasia yet did not show clinical signs of CNS disease. Thus, it is worthwhile to note that most assessments of RVF disease in murine models are based on acute disease symptoms and survival. Therefore, long-term cognitive impairments stemming from WT RVFV challenge may go undetected in murine survivors. The dose reduction PT experiments revealed that CC057/Unc were still 100% protected when immune serum was given D2 and diluted 1:20; however, the minimum correlate of protection remains to be defined. Taken together, our study implicates humoral immunity as a critical correlate of protection against RVF CNS disease.

A few studies have demonstrated that cellular immunity is an important component of adaptive immunity in preventing ΔNSs-mediated encephalitis in the C57BL/6 background. Using transgenic/knockout mice and cell-specific depletion antibodies, subsequent studies revealed that monocytes, CD4, and CD8 T cells contributed to disease prevention19 and that Tfh/B cell interactions modulate the clinical outcome in this model16 suggesting that interactions or involvement of multiple adaptive immune cell types are required. In agreement, C57BL/6 mice were protected against WT challenge when they received adoptive transfers (AT) of total splenocytes from vaccinated animals but not when receiving only T and B cells or when B cells were depleted17. Notably, the lack of congenic mice in the CC057/Unc model is currently a technical challenge preventing more detailed investigations regarding the importance of cellular immunity for CNS disease. However, this work demonstrated that vaccination with live attenuated RVFV (ΔNSs or ΔNSsΔNSm) elicited RVFV-specific T cells in addition to humoral immunity in CC057/Unc mice. Interestingly, there were more CD4 and CD8 T cells that displayed specificity to the viral nucleoprotein N as compared to the glycoproteins, Gn and Gc. In agreement, a study has described N to be a potent CD8 human T cell antigen27, whereas the glycoproteins are strongly implicated in the context of humoral immunity and generation of neutralization antibodies28. Moreover, studies using DNA vaccines encoding the N protein demonstrated partial protection against lethal disease in BALB/c and IFNAR-/- mice29,30. Overall, these findings indicate that both the interactions between humoral immunity and cellular immunity directed against the viral structural proteins likely contribute to the prevention of RVF CNS disease following vaccination.

While adaptive cellular immunity may play a role in preventing CNS disease, neutralizing RVFV-specific antibodies are sufficient to provide protection if given early and in sufficient quantities. The hepatic and CNS RVF murine models could be used to define mechanistic humoral immune correlates of protection from both forms of disease. These data could augment ongoing human vaccine studies by providing immune bridging data to extrapolate to predictive protective neutralizing antibody titers. This could further support licensure under the animal rule and avoid costly phase 3 efficacy studies.

Materials and methods

Biosafety

All experiments with WT RVFV (ZH501) and ΔNSs RVFV were conducted in Biosafety Level 3 (BSL-3) and Animal Biosafety Level 3 (ABSL-3) facilities at the University of Pittsburgh Regional Biocontainment Laboratory (RBL), which has Division of Select Agents and Toxins (DSAT) approval for work with Select Agents. Work with ΔNSsΔNSm was performed at BSL-2.

Animal studies

This study complied with institutional guidelines and all procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol 22030821).

Mouse experiments

A breeding trio consisting of two female and one male CC057/Unc mice were obtained from the UNC Collaborative Cross resource and used to initiate and maintain an off-site breeding colony (Charles River). Female and male CC057/Unc mice (4–12 weeks old) were shipped from Charles River to the University of Pittsburgh and housed within ABSL-3 laboratories in microisolator cages in HEPA filtration racks, following standard barrier techniques.

Mock vaccination (sterile PBS, Gibco #10010), vaccination with attenuated RVFV, and challenge with WT RVFV (diluted in PBS from stocks to desired TCID50) were performed via left foot pad injection (20 μL total) under isoflurane anesthesia. For passive transfer (PT) experiments, mice received an intraperitoneal injection (200 μL total) of normal mouse serum or immune mouse serum at undiluted or 1:20, 1:100 or 1:500 (diluted in sterile PBS) concentrations at indicated days (D) post WT challenge. The immune serum was generated by pooling mouse sera from ΔNSs vaccinated female C57BL/6 J mice (5.3 log10 endpoint titer by ELISA)17. Where applicable, blood was collected from mice either before WT challenge (pre-challenge) or post-PT via lateral saphenous bleed into serum separator tubes and centrifuged for serum purification. Animals were monitored for clinical signs of disease and survival for up to 56 days post-vaccination. Animal groups and numbers are as followed: mock vaccinated/ 2TCID50 WT RVFV (n = 3); 2 × 105 TCID50 ΔNSs (n = 4); 2 x 105 TCID50 ΔNSs/ 2 TCID50 WT RVFV (n = 4); 2 x 105 TCID50 ΔNSsΔNSm (n = 4); 2 x 105 TCID50 ΔNSsΔNSm/ 2 TCID50 WT RVFV (n = 4); 2000 TCID50 ΔNSsΔNSm/ 2 TCID50 WT RVFV (n = 3), 20 TCID50 ΔNSsΔNSm/ 2 TCID50 WT RVFV (n = 3); 2 TCID50 WT RVFV/ PT D2 control serum (n = 3); 2 TCID50 WT RVFV/ PT D2 immune serum (n = 3); 2 TCID50 WT RVFV/ PT D3 immune serum (n = 8); 2 TCID50 WT RVFV/ PT D4 immune serum (n = 8); 2 TCID50 WT RVFV/ PT D5 immune serum (n = 9); 2TCID50 WT RVFV/ PT D6 immune serum (n = 8); 2 TCID50 WT RVFV/ PT D7 immune serum (n = 8); 2 TCID50 WT RVFV/ PT D2 1:20 immune serum (n = 3); 2 TCID50 WT RVFV/ PT D2 1:100 immune serum (n = 3); 2 TCID50 WT RVFV/ PT D2 1:500 immune serum (n = 3). The vaccine and immune serum dosages were chosen based on a previous study17.

Across experiments, mice were evaluated for clinical signs of disease at least once a day and euthanized according to a predetermined clinical illness scoring algorithm5. At the time of euthanasia, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (Piramal, #NDC 66794-017-10), bled via cardiac puncture for serum isolation and then euthanized through cervical dislocation. Tissues collected included liver, spleen and brain. For splenocyte isolation, spleens were collected in 5 mL RPMI-1640 (Gibco, #A10491) with 10% FBS, and splenocytes were prepared using manual disruption.

Virus strains and cell culture

Stocks of recombinant WT RVFV (strain ZH501) and RVFV lacking NSs (ΔNSs) or NSs and NSm (ΔNSsΔNSm) were produced using reverse genetics as previously published31, grown to passage 2 and sequence confirmed via Illumina prior to use. The RVFV reverse genetics system was kindly shared by César Albariño of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Viral Special Pathogens Branch (VSPB). Vero E6 cells (ATCC CRL-1587) were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco, #10566) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, #16000) and 1x Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco, #15240) at 37 °C, 5% CO2 using conventional cell culture techniques. Viral titers for all three viruses were determined as 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) by serial dilution and incubation on Vero E6 cells5. Plates were stained by indirect fluorescent-antibody assay (IFA) using a monoclonal mouse IgG1 anti-RVFV N primary antibody (custom, Genscript) and the Alexa FluorTM 488 goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Invitrogen, #A11001), and TCID50 was assessed using Reed & Muench32.

In vitro experiments

RNA extraction and RVFV qRT-PCR

Tissues from in vivo experiments were collected into pre-weighed grinding vials (Fisher, #15-340-154) containing 500 μL PBS and 1x Antibiotic-Antimycotic and weighed prior to homogenization with the D2400 Homogenizer (Benchmark Scientific). RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, #15596018) and the Direct-zolTM MiniPrep Plus kit (Zymo Research, #R2072). Sample RNA was assayed by qRT-PCR for the RVFV L segment or S segment using Reliance One-Step Multiplex RT-qPCR Supermix (BioRad, #12010221) and viral RNA loads were determined based upon an RNA standard curve as previously described5. The following conditions were used: 50 °C for 15 min (min), 95 °C for 3 min, and then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s (s), and 55 °C for 1 min. The assay limit of detection (LOD) is set as the lowest amount of detectable standard curve RNA normalized to the average tissue weight.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Lysates were generated from either uninfected Vero E6 cells or RVFV ΔNSsΔNSm infected Vero E6 cells. Briefly, cells were infected at a multiplicity of 1 and once infected cells reached >75% cytopathic effect, the cells from 10 T150 flasks were combined and resuspended in 5 mL lysis solution (1% Triton X-100 in PBS with protease inhibitor (ThermoFisher, #A32963)). Lysates were sonicated for 10 min and clarified by centrifugation. MaxiSorpTM plates (Fisher, #44-2404-21) were coated with lysates from either uninfected or ΔNSsΔNSm infected Vero E6 cells and incubated at 4 °C overnight. For RVFV NSs-specific ELISA, plates were coated with SARS-CoV-2 N protein33 as the negative control or recombinant RVFV NSs (custom, Genscript) at 200 ng of protein per well in sterile PBS and incubated at 4 °C overnight. The following day, plates were incubated with blocking buffer (5% non-fat milk in PBS-Tween 0.1%, PBST) for 1 hour (h). In duplicate, mouse serum samples collected either pre-challenge, post-PT or at the time of euthanasia, as well as a negative mouse control serum, were serially diluted in blocking buffer and incubated on plates for 2 h at 37 °C. Plates were then washed three times with PBST and incubated with HRP-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, #715-035-150) at 1: 5,000 in blocking buffer for 1 h at 37 °C. Plates were again washed three times with PBST and tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (SeraCare, #5120-0038, 5120-0049) and subsequently TMB stop solution (SeraCare, #5150-0021) were added to the plates. The optical density (OD) at 450 nm was measured via Biotek Synergy plate reader. The endpoint titer was defined as the highest dilution of serum that resulted in an OD value at least three standard deviations above the average obtained from all negative mouse serum control wells.

Focus reduction neutralization assay (FRNT)

In duplicate, mouse sera from either pre-challenge, post-PT or terminal bleeds as well as a negative control mouse serum were serially diluted in cell culture media and incubated with an equal volume of media containing 200 foci-forming units (FFUs) of ΔNSsΔNSm for 1 h at 37 °C. Vero E6 cells in 96-well format were subsequently incubated with the serum-virus mix for 1 h at 37 °C. The inoculum was then replaced with 1.5% carboxylmethylcellulose (CMC) (Sigma, #C4888)/ 1x Modified Eagle Medium (MEM), diluted from 3% CMC in 2x MEM (Gibco, #11935), for 18 h. Plates were washed with PBS, fixed in 10% formalin for 20 min, and again washed in PBS. Plates were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X100 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature (RT), washed with PBS, and blocked in 5% non-fat-milk in PBST for 1 h. Immunostaining was performed using a rabbit polyclonal anti-RVFV N primary antibody at 1:1,000 (custom, Genscript) in 5% non-fat-milk in PBST for 1 h at RT followed by a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody at 1:1000 (Jackson Immuno Research, #711-035-152) for 1 h at RT. Staining was developed using TMB substrate (MossBio, #TMBH-1L). Plates were dried overnight and imaged using the CTL Immunospot reader. The focus reduction neutralization titer (FRNT80 or FRNT50) was defined as the dilution of serum that neutralized 80 or 50% of input FFU, respectively.

Virus isolation from brain tissue

Virus isolations were performed by inoculation of brain tissue homogenates onto Vero E6 cells. Briefly, 100 uL brain tissue homogenate from selected animals were added to Vero E6 cells in a 24-well format and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Wells were washed with PBS, cell culture media (DMEM, 10% FBS, 1x Antibiotic-Antimycotic) was added and plates were incubated for 3 days at 37 °C. Plates were stained as described above for the TCID50 assay.

T cell ELISPOTS

To assess virus-specific T cells following vaccination, an IFN-γ mouse ELISPOT assay (Mabtech Inc., #3321-4HPT-2) was used following the manufacturer’s instruction and as previously described34. Briefly, splenocytes were isolated using manual disruption and incubated on pre-coated MultiScreen® IP sterile plates (Millipore, #MSIPS4W10) with negative control (DMSO vehicle), positive control (Cell Activation Cocktail, PMA/Ionomycin, Biolegend, #423301) or peptide pools (2 μg/mL final concentration) that represent the entirety of each viral structural protein in 15 mer peptides with 11 mer overlaps. Peptides in each pool are as follows: RVFV nucleoprotein N (n = 59), glycoprotein Gc ([Gc1, n = 61], [Gc2, n = 62]), and glycoprotein Gn ([Gn1, n = 70], [Gn2, n = 70]). Spots were counted on the CTL Immunospot reader.

Flow cytometry

A flow cytometric assay was also used to assess virus-specific T cells following vaccination. Splenocytes were washed in RPMI-1640 (Gibco, #A10491) with 10% FBS then incubated with either positive control (Cell Activation Cocktail, PMA/Ionomycin Biolegend, #423301), negative control (Dimethyl Sulfoxide, DMSO, Sigma, #D2650) or RVFV peptide pools (2 μg/mL final concentration) for 6 h at 37 °C in the presence of 10 μg/mL brefeldin A (Brefeldin A solution, Biolegend, #3420601). They were then washed in PBS, incubated in LIVE/DEAD near IR (Thermo Fisher, #L34976) at 1:500 for 10 min. Following a wash in flow buffer (PBS with 2% FBS) cells were stained for 30 min using the following antibodies: BV510 CD3 (17A2, Biolegend, #100234), BUV395 CD4 (RM4-5, BD, #740208), PE/Cy7 CD8a (53-6.7, BD, #552877), BV421 CD44 (IM7, Biolegend, #103039), APC/Cy7 CD19 (6D5, Biolegend, #115530), APC/Cy7 CD14 (Sa14-2, Biolegend, #123318). Cells were then washed twice in flow buffer, and fixed with BD Cytofix/CytopermTM (BD Biosciences, #51-2090KZ). After fixation and permeabilization, cells were washed in BD Perm/Wash (BD Biosciences, #51-2091KZ), and stained with Alexa647 IFN-γ (XMG1.2, BD, #557735) for 45 min and then again washed prior to acquisition on an LSRII. The gating strategy is depicted in Fig. 3B. Briefly, lymphocytes were identified by forward and side scatter, then single cells were gated using forward scatter area versus height. A time gate was applied for homogeneity then live T cells were determined as CD3+/CD19-/CD14-/live-dead near IR negative. CD3+ cells were then separated into CD4+ and CD8+ populations. Of these populations, activated T cells were defined as CD44+/IFN-gamma +. Data were analyzed using FlowJo.

Data processing and statistical analysis

All graphs were generated and statistical analyses performed using GraphPad Prism 10. Comparison between groups in the flow cytometry experiment were analyzed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney test and survival studies were analyzed using Mantel-Cox test. Figures were generated using Adobe Illustrator and timelines within the figures were generated with BioRender.com.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article. Any unique reagents are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

McMillen, C. M. & Hartman, A. L. Rift Valley fever in animals and humans: current perspectives. Antivir. Res 156, 29–37 (2018).

Ikegami, T. & Makino, S. The pathogenesis of Rift Valley fever. Viruses 3, 493–519 (2011).

Madani, T. A. et al. Rift Valley fever epidemic in Saudi Arabia: epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory characteristics. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37, 1084–1092 (2003).

Alrajhi, A. A., Al-Semari, A. & Al-Watban, J. Rift Valley fever encephalitis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10, 554–555 (2004).

Cartwright, H. N., Barbeau, D. J. & McElroy, A. K. Rift Valley fever virus is lethal in different inbred mouse strains independent of sex. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1962 (2020).

Bales, J. M., Powell, D. S., Bethel, L. M., Reed, D. S. & Hartman, A. L. Choice of inbred rat strain impacts lethality and disease course after respiratory infection with Rift Valley fever virus. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2, 105 (2012).

Dodd, K. A. et al. Rift Valley fever virus encephalitis is associated with an ineffective systemic immune response and activated T cell infiltration into the CNS in an immunocompetent mouse model. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8, e2874 (2014).

Hickerson, B. T. et al. Pathogenesis of Rift Valley fever virus aerosol infection in STAT2 knockout hamsters. Viruses 10, 651 (2018).

Reed, C. et al. Aerosol exposure to Rift Valley fever virus causes earlier and more severe neuropathology in the murine model, which has important implications for therapeutic development. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7, e2156 (2013).

Wilson, L. R. & McElroy, A. K. Rift Valley fever virus encephalitis: viral and host determinants of pathogenesis. Annu Rev. Virol. 11, 309–325 (2024).

Cartwright, H. N. et al. Genetic diversity of collaborative cross mice enables identification of novel rift valley fever virus encephalitis model. PLoS Pathog. 18, e1010649 (2022).

Alkan, C., Jurado-Cobena, E. & Ikegami, T. Advancements in Rift Valley fever vaccines: a historical overview and prospects for next generation candidates. NPJ Vaccines 8, 171 (2023).

Billecocq, A. et al. NSs protein of Rift Valley fever virus blocks interferon production by inhibiting host gene transcription. J. Virol. 78, 9798–9806 (2004).

Ikegami, T. et al. Dual functions of Rift Valley fever virus NSs protein: inhibition of host mRNA transcription and post-transcriptional downregulation of protein kinase PKR. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1171, E75–E85 (2009).

Kading, R. C. et al. Deletion of the NSm virulence gene of Rift Valley fever virus inhibits virus replication in and dissemination from the midgut of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8, e2670 (2014).

Barbeau, D. J. et al. Identification and characterization of Rift Valley fever virus-specific T cells reveals a dependence on CD40/CD40L interactions for prevention of encephalitis. J. Virol. 95, e0150621 (2021).

Doyle, J. D., Barbeau, D. J., Cartwright, H. N. & McElroy, A. K. Immune correlates of protection following Rift Valley fever virus vaccination. NPJ Vaccines 7, 129 (2022).

Dodd, K. A., McElroy, A. K., Jones, M. E., Nichol, S. T. & Spiropoulou, C. F. Rift Valley fever virus clearance and protection from neurologic disease are dependent on CD4+ T cell and virus-specific antibody responses. J. Virol. 87, 6161–6171 (2013).

Harmon, J. R. et al. CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, and monocytes coordinate to prevent Rift Valley fever virus encephalitis. J. Virol. 92, e01270-18 (2018).

Prajeeth, C. K. et al. Immune correlates of protection of the four-segmented Rift Valley fever virus candidate vaccine in mice. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 13, 2373313 (2024).

Watts, D. M. et al. Estimation of the minimal Rift Valley fever virus protective neutralizing antibody titer in human volunteers immunized with MP-12 vaccine based on protection in a mouse model of disease. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 107, 1091–1098 (2022).

Smith, D. R. et al. The pathogenesis of Rift Valley fever virus in the mouse model. Virology 407, 256–267 (2010).

Plotkin, S. A. Recent updates on correlates of vaccine-induced protection. Front. Immunol. 13, 1081107 (2022).

Wichgers Schreur, P. J., Oreshkova, N., Moormann, R. J. & Kortekaas, J. Creation of Rift Valley fever viruses with four-segmented genomes reveals flexibility in bunyavirus genome packaging. J. Virol. 88, 10883–10893 (2014).

Warimwe, G. M. et al. Immunogenicity and efficacy of a chimpanzee adenovirus-vectored Rift Valley fever vaccine in mice. Virol. J. 10, 349 (2013).

Papin, J. F. et al. Recombinant Rift Valley fever vaccines induce protective levels of antibody in baboons and resistance to lethal challenge in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14926–14931 (2011).

Xu, W. et al. The nucleocapsid protein of Rift Valley fever virus is a potent human CD8+ T cell antigen and elicits memory responses. PLoS One 8, e59210 (2013).

Wright, D. et al. Naturally acquired Rift Valley fever virus neutralizing antibodies predominantly target the Gn glycoprotein. iScience 23, 101669 (2020).

Lagerqvist, N. et al. Characterisation of immune responses and protective efficacy in mice after immunisation with Rift Valley fever virus cDNA constructs. Virol. J. 6, 6 (2009).

Lorenzo, G., Martin-Folgar, R., Hevia, E., Boshra, H. & Brun, A. Protection against lethal Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) infection in transgenic IFNAR(-/-) mice induced by different DNA vaccination regimens. Vaccine 28, 2937–2944 (2010).

Gerrard, S. R., Bird, B. H., Albarino, C. G. & Nichol, S. T. The NSm proteins of Rift Valley fever virus are dispensable for maturation, replication and infection. Virology 359, 459–465 (2007).

Reed, L. J. M. H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Epidemiol. 27, 493–497 (1938).

Xu, L. et al. A cross-sectional study of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence between Fall 2020 and February 2021 in Allegheny County, Western Pennsylvania, USA. Pathogens 10, 710 (2021).

Barbeau, D. J. et al. Rift Valley fever virus infection causes acute encephalitis in the ferret. mSphere 5, e00798-20 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the following funding sources: NIH T32 AI060525 (to K.M.B), NIH T32 AI049820 (to L.X.), NIH R01 AI171200 (to A.K.M.), Burroughs Wellcome CAMS 1013362, NIH award (UC7AI180311) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) supporting the Operations of The University of Pittsburgh Regional Biocontainment Laboratory (RBL) within the Center for Vaccine Research (CVR), UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. We would like to acknowledge the Division of Laboratory Animal Resources at the University of Pittsburgh for assistance with animal husbandry. We would like to thank CEPI and the European Commission for their overarching support of DDVax development efforts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.M.B. and A.K.M. wrote the main manuscript text. K.M.B. prepared figures. K.M.B., D.J.B., L.X., and A.K.M. performed the experiments. B.H.B. and A.K. M. conceptualized. A.K.M. supervised and acquired funding. All authors reviewed this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

B.H.B. is an inventor of patents describing the development of the ΔNSs-ΔNSm-rZH501 vaccine candidate technology (USPTO: 8,673,629, 9,439,935, and 10,064,933). The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mueller Brown, K., Barbeau, D.J., Xu, L. et al. Humoral immunity is sufficient to protect mice against Rift Valley fever encephalitis following percutaneous exposure. npj Vaccines 10, 141 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01200-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01200-2