Abstract

Influenza is a global health concern, causing over 300,000 deaths worldwide annually. Current vaccines and natural infection mainly elicit antibodies against the variable head domain of the hemagglutinin (HA) glycoprotein. While these antibodies are highly neutralizing, the head domain constantly mutates due to selective pressure, causing the immune response to be strain-specific. Targeting the conserved HA stalk domain, however, has been shown to be a promising approach for a broadly protective vaccine. We previously demonstrated that presenting HA in an inverted orientation on virus-like particles (VLPs) significantly enhanced the induction of stalk-directed, cross-reactive antibodies compared to HA presented in a regular orientation. Here, we evaluated the protective efficacy of the inverted HA vaccine (VLP-HAinv) in mice against homologous, heterologous, and heterosubtypic influenza A virus challenges. VLP-HAinv vaccination in mice provided complete protection against homologous and heterologous H1N1 challenges as well as partial protection against a heterosubtypic challenge with bovine H5N1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Influenza is a viral respiratory disease with significant global impact, causing between 300,000 and 500,000 deaths annually across the globe1. Vaccination is a key strategy to minimize viral spread and mortality, and influenza vaccines based on live attenuated viruses or inactivated viruses have been available for several decades2. More recently, vaccines using recombinant hemagglutinin (HA) protein that form rosettes3 have been licensed as well4. All currently licensed vaccines, as well as natural infections, typically elicit immune responses against the HA protein5,6,7, which is responsible for mediating receptor attachment to host cells and subsequent viral entry. In particular, this immune response is directed against the highly plastic8,9 head domain of HA, which contains the receptor binding site. While such head-directed responses can be highly neutralizing10, the plasticity and high mutation rate11 of the HA head result in head-directed immunity that is often strain-specific. This strain-specificity in turn necessitates the annual reformulation of influenza vaccines to match recently emerged strains, which can result in poor effectiveness if novel antigenic variants become dominant before the updated vaccines are available. Furthermore, this strain-specificity suggests that the current seasonal vaccines would likely have poor effectiveness against potential pandemic strains such as highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) of H5N1 or H7N9 subtypes. The ongoing spread of clade 2.3.4.4b HPAI H5N1 viruses in cattle12 with spillover to humans13,14 and its potential for rapid adaptation to mammalian hosts15,16 further accentuates this concern.

In contrast to the HA head domain, the stalk domain is considerably less plastic17 and more highly conserved both within and across subtypes. This makes the stalk domain a promising target for inducing a broadly protective immune response. Many monoclonal antibodies targeting the stalk domain are both broadly reactive across subtypes and capable of providing protection against multiple influenza subtypes in small animal challenge models18,19,20,21. Notably, anti-stalk antibodies are less affected by single amino acid mutations in HA than head-directed antibodies22. The development of vaccines that can elicit enhanced anti-stalk responses is an active area of research, with several different strategies being pursued. Vaccination with recombinant stalk-only proteins has achieved considerable success in eliciting anti-stalk immunity in animal models23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 and has since progressed to clinical trials32. Sequential vaccination with chimeric hemagglutinins (cHAs) is another promising approach in which each successive antigen contains an exotic head domain connected to the same stalk domain33,34. This results in the induction of a memory response to the stalk domain but a de novo response to the exotic head domains, ultimately leading to an increase in anti-stalk antibody titers. Shielding of the HA head domain with glycans35 or antibody fragments36 has also been used to improve the anti-stalk response.

We previously showed that nanoparticles presenting HA in an inverted orientation elicited higher anti-stalk antibody titers than nanoparticles presenting HA in a regular orientation37. Specifically, we developed a platform for inverting the orientation of HA on a virus-like particle (VLP) using a head-binding antibody fragment37. We hypothesized that the geometric arrangement of HA on viral membranes, with the head domain pointing outwards in a more accessible location than the membrane-proximal stalk, is a leading cause for the head-directed immune response observed from whole-virus vaccines. Similarly, recombinant HA vaccines form rosettes with arrangements that are comparable to those of whole-virus vaccines. We demonstrated that a vaccine containing an inverted HA (VLP-HAinv) from A/Puerto Rico/8/1934(H1N1) induced a stronger anti-stalk antibody response than a VLP displaying HA in the standard head-out orientation and showed better protection against a chimeric cH6/1N5 virus containing a chimeric hemagglutinin with an H6 head domain and an H1 stalk domain37. In a more recent report, Xu et al. employed a different approach to present HA in an upside-down orientation by incorporating aspartate residues to facilitate binding to alum, and demonstrated the ability to elicit cross-reactive anti-stalk antibodies; however, the ability to protect against viral challenges was not reported38.

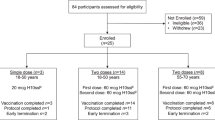

In this work, we aimed to assess the protective efficacy of VLP-HAinv against challenges with homologous, heterologous, and heterosubtypic influenza A viruses (Fig. 1a) in mice. We assessed one dose, two dose, and three dose regimens against challenges with a homologous virus A/Puerto Rico/8/1934(H1N1) (PR8), a heterologous 2009 pandemic virus A/Netherlands/602/2009(H1N1) (NL602), and a bovine clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 virus A/bovine/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (NM93-H5N1), finding that we could get complete protection against both H1N1 challenges and partial protection against H5N1 challenge.

Results

Assembly and characterization of VLP-HAinv

We generated VLPs presenting HA in an inverted orientation (VLP-HAinv) as described in our previous work37. MS2 coat protein homodimers39—with each homodimer containing an AviTag40,41 inserted into one of its surface loops to enable site-specific biotinylation by the enzyme BirA—were expressed in BL21(DE3) Escherichia coli (E. coli) cells and purified. The MS2 protein homodimers self-assemble into a particle42, which was then biotinylated and added to excess streptavidin (SA). The resulting MS2-SA VLPs37,40,41,43-44 were separated from excess SA and used for further assembly.

We inverted the orientation of HA by first displaying the Fab fragment of the H28-D14 antibody45 on the VLP (VLP-Fab). The H28-D14 Fab, which included an AviTag at the C-terminus of the heavy chain, was expressed in mammalian cells and purified via immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (IMAC) and size exclusion chromatography (SEC). The purified Fab was subsequently biotinylated in vitro with the enzyme BirA and separated from the biotinylation reagents using SEC. The H28-D14 Fab is specific to the Sb antigenic site of HA, which is located at the apex of the HA head45. VLP-Fab enables the multivalent display of HA on the surface of the VLP with the stalk domain as the outermost portion of the HA (Fig. 2a). Concurrently, the HA ectodomain from PR8, incorporating a C-terminal T4 phage fibritin trimerization domain followed by a Strep-Tag II was expressed in mammalian cells and purified using Strep-Tactin XT Sepharose resin and SEC. The purified HA was mixed with VLP-Fab and separated by SEC, resulting in VLP-HAinv.

a Schematic of the assembly of VLP-HAinv. The HA head domain and stalk domain are colored cyan and orange, respectively. b SDS-PAGE gel of HA, H28-D14 Fab, MS2-SA, and VLP-HAinv. Streptavidin-biotin interaction has been disrupted by boiling samples, and the samples were reduced with dithiothreitol. c Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of stalk-targeting antibody CR6261 against VLP-HAinv. Each datapoint represents the arithmetic mean and standard deviation of triplicates. d Characterization of VLP-HAinv by dynamic light scattering.

The VLP-HAinv and its constituent components were characterized in vitro with various bioanalytical methods. SDS-PAGE analysis confirmed the high purity of VLP, Fab, HA, and VLP-HAinv, displaying bands corresponding to the expected molecular weights of the MS2, SA, Fab, and HA components (Fig. 2b). To verify that HA retained its proper conformation following assembly, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed. The ELISA analyses demonstrated the binding of the anti-stalk CR6261 antibody to the HA on VLP-HAinv., indicating preserved antigenicity (Fig. 2c). Characterization by dynamic light scattering (DLS) indicated that the diameter of VLP-HAinv (Fig. 2d) was consistent with its anticipated sizes calculated from the theoretical sizes of the individual proteins and prior experimental results37.

VLP-HAinv protects BALB/cJ mice against homologous and heterologous challenges

Having previously demonstrated an enhanced anti-stalk immune response induced by VLP-HAinv vaccination, we sought to further assess its breadth of protection against homologous and heterologous H1N1 influenza virus strains. Female BALB/cJ mice (6–8 weeks old) were vaccinated using different doses and regimens as described below (Fig. 3a) and challenged with either the homologous strain (PR8) or the heterologous strain (NL602)—a 2009 pandemic H1N1 strain with an HA that is antigenically distinct from that of the PR8 strain (Fig. 1b). For prime-only vaccinations, mice were immunized subcutaneously with either 7.5 or 15 µg of HA per dose. For prime-boost regimens, mice received an immunization of 2.5 or 5 µg HA per dose for homologous virus challenges, and 2.5, 5, or 10 µg HA per dose for heterologous virus challenges. Each vaccine preparation was adjuvanted with AddaVax (InvivoGen) prior to administration. Control groups received either equivalent amounts of MS2-SA VLP adjuvanted with AddaVax or AddaVax alone. For viral challenges (on day 28 for the prime-only vaccinations and day 49 for the prime-boost vaccinations), mice received intranasal inoculations using a dosage of 10x the mouse lethal dose 50 (LD50) of the respective influenza virus strains.

a Schematic of prime-only and prime-boost vaccination regimens. Mean body weight change (b) and Kaplan–Meier survival curve (c) of mice vaccinated with a single dose of VLP-HAinv (n = 5) or control (n = 5) and challenged with PR8. Weight loss (d) and survival (e) of mice vaccinated with a single dose of VLP-HAinv (n = 5) or control (n = 5) and challenged with NL602. Weight loss (f) and survival (g) of mice vaccinated with two doses of VLP-HAinv (n = 5) or control (n = 5) and challenged with PR8. Mean body weight change (h) and Kaplan–Meier survival curve (i) of mice vaccinated with two doses of VLP-HAinv or control and challenged with NL602. Body weight curves display the mean and standard deviation of the body weight percentages of live mice at each time point (n = 5 at study start). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 were determined by the log-rank test.

As shown in Fig. 3, the VLP and AddaVax control groups provided no protection—nearly all mice died by day 11 across all doses and regimens as expected, except for one mouse in the VLP control group that received a prime-boost regimen against the homologous challenge. All control mice experienced rapid weight loss apart from the one mouse in the homologous challenge VLP control, which showed full recovery by day 14. In contrast, all mice vaccinated with VLP-HAinv were fully protected from the homologous challenge, with no significant weight loss observed across any dose or regimen (Fig. 3b, c, f, g). Against the heterologous strain, both 7.5 and 15 µg prime-only vaccinations gave 80% survival (Fig. 3e). Mice immunized with 7.5 µg HA lost more weight than those given 15 µg (Fig. 3d), but survivors in both groups fully recovered. Prime-boost regimens with 2.5, 5, and 10 µg doses provided complete protection, with about 10% weight loss and full recovery (Fig. 3h, i).

VLP-HAinv protects BALB/cJ mice against heterosubtypic H5N1 challenges

To further evaluate the breadth of protection, we challenged VLP-HAinv vaccinated mice with a heterosubtypic NM93-H5N1 virus strain. Female BALB/cJ mice (6–8 weeks old) were immunized with 10 µg of HA per dose using either a prime-boost or a three-dose regimen (Fig. 4a). Each vaccine formulation was prepared by mixing VLP-HAinv with AddaVax at a 1:1 volume ratio prior to administration. Control groups received either an equivalent amount of adjuvanted MS2-SA VLP only or AddaVax (InvivoGen) adjuvant alone. For the prime-boost regimen, sera were collected on day 21 post-prime, mice were boosted on day 28, and post-boost sera were collected on day 42. In the three-dose regimen, mice received booster doses every four weeks, with sera collected on days 21, 49, and 77. Virus challenges were conducted on day 49 for the prime-boost group and on day 80 for the three-dose group. Mice were infected intranasally with 10 × LD50 of the H5N1 challenge strain. Clinical signs and body weight were monitored daily for 21 days post-challenge in the prime-boost group and for 14 days in the three-dose group. As expected, the VLP and AddaVax treatments alone provided no protection, as all mice rapidly lost body weight and succumbed by day 11 post-infection (Fig. 4). However, mice vaccinated with VLP-HAinv showed partial protection against the H5N1 challenge, with 60% survival in the prime-boost group and 80% survival in the three-dose group (Fig. 4c, e), with comparable patterns of weight loss and recovery (Fig. 4b, d). We had previously shown that immunization with VLPs presenting HA in an inverted orientation enhances the antibody response against the conserved stalk domain37. While the observed protection against homologous, heterologous, and heterosubtypic influenza strains following immunization with VLP-HAinv would be consistent with those findings, a direct comparison with results for the immunization of VLPs presenting HA in a regular orientation would be needed to confirm that the broad cross-protection is primarily due to HA orientation.

a Schematic of prime-boost and 3-dose immunization regimens. Mean body weight change (b) and Kaplan–Meier survival curve (c) of mice vaccinated with two doses of VLP-HAinv (n = 5) or control (n = 5) and challenged with NM93-H5N1. Mean body weight change (d) and Kaplan–Meier survival curve (e) of mice vaccinated with three doses of VLP-HAinv (n = 5) or control (n = 5) and challenged with NM93-H5N1. Body weight curves display the mean and standard deviation of the body weight percentages of live mice at each time point (n = 5 at study start). No significance (ns) and **p < 0.01 were determined by the log-rank test.

VLP-HAinv elicits cross-reactive antibodies in mice, but neutralizing activity decreases with increasing antigenic distance from the immunogen

Next, ELISA and microneutralization assays were performed using sera from mice vaccinated in the three-dose regimen to characterize the antibody responses elicited by VLP-HAinv vaccination. Endpoint titers of sera collected on days 21, 49, and 77 were determined through serial dilution followed by ELISA against PR8 HA, stalk-only HA, and HA derived from A/dairy cow/Texas/24-008749-002-v/2024 (H5N1), a similar clade 2.3.4.4b H5 with only a single amino acid difference compared to the NM93 hemagglutinin (N323S, H3 numbering). As shown in Fig. 5a, sera from mice vaccinated with VLP-HAinv exhibited significantly higher endpoint titers against PR8 HA and stalk-only HA compared to the VLP control. Notably, cross-reactivity against H5N1 HA was observed, although endpoint titers against H5 HA were lower than those against H1 HA antigens. For microneutralization assays, mouse sera collected on days 21, 49, and 77 underwent pretreatment, and the serially diluted sera were then incubated with virus strains corresponding to the challenge experiments and added to MDCK cells to assess the cytopathic effect (CPE). Neutralization assays, as expected, showed robust neutralizing activity against the homologous strain. However, the activity progressively decreased with higher antigenic distance from the vaccine immunogen, with no detectable neutralization against the heterosubtypic bovine H5N1 strain (Fig. 5b).

a IgG endpoint titers against PR8 HA, stalk-only H1 HA, and HA from A/dairy cow/Texas/24-008749-002-v/2024(H5N1). Lower limits for the VLP (dilution = 500) and VLP-HAinv groups (dilution = 333) are shown as dotted lines and dashed lines, respectively. Bar graphs represent geometric mean with geometric standard deviation; n = 5 mice immunized with VLP-HAinv; n = 5 mice immunized with VLP. No significance (ns) and **p < 0.01 were determined by the Mann–Whitney U-test. b Neutralization of A/Puerto Rico/8/1934(H1N1), A/Netherlands/602/2009(H1N1), and A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024(H5N1) by sera from mice immunized with one, two, or three doses of VLP-HAinv. Each datapoint represents geometric mean and standard deviation (n = 5 per group). † - No neutralization titers detected for all mice; detection lower limit (dotted line) = 20. ‡ - Neutralization titers detected for all dilutions for each mouse; detection upper limit (dashed line) = 10,240.

Discussion

We previously demonstrated that inverting the orientation of hemagglutinin (HA) enhanced the stalk-directed cross-reactive antibody response across multiple influenza subtypes, including group 1, group 2, and even influenza B HAs, and conferred protection against a cH6/1N5 challenge. Building on these findings, the present study shows that immunization with VLP-HAinv provides complete protection against homologous and heterologous H1N1 challenge and partial protection against heterosubtypic H5N1 challenge. As expected, neutralizing activity declines as the antigenic distance of the challenge strain from the immunogen increases. This is consistent with the notion that neutralizing antibodies primarily target the variable head domain of HA. For heterologous and heterosubtypic protection, given the lack of strong neutralization, other mechanisms likely contribute to the observed protection. We reason that Fc-mediated antibody effector functions may play a critical role in mediating protection following VLP-HAinv vaccination, as has been demonstrated for previous stalk-targeting strategies23,34,44. Cross-reactive adaptive cellular immune responses elicited against conserved epitopes may also play a role in protection following VLP-HAinv vaccination. We will explore the contributions of these mechanisms to protection in future studies.

However, the partial protection observed against heterosubtypic viruses indicates room for improvement. One strategy to enhance protection may be to formulate a cocktail vaccine incorporating inverted HA from multiple subtypes. While previous approaches to elicit broad stalk-based immunity have primarily attempted to focus the response on the HA stalk domain from a single subtype, a mixture of VLP-HAinv constructs from diverse HA subtypes may elicit broader and more robust protection across antigenically distinct strains—a strategy that we have successfully demonstrated in the context of SARS-like coronaviruses44. Given the rising threat of highly pathogenic avian influenza strains such as H5N1, the inverted HA display platform represents a promising approach not only for mitigating the risk of future avian influenza pandemics but also for generating cross-protective immunity against a wide array of influenza viruses yet to emerge.

Mouse models were utilized to characterize the immune response elicited by VLP-HAinv vaccination. However, the response in mice may not directly translate to the human immune response. Additionally, this study did not consider the influence of pre-existing immunity, which could arise from previous influenza vaccinations or infections and impact the immune response induced by VLP-HAinv vaccination.

The approach for generating VLP-HAinv involves multiple purification steps, enzymatic biotinylation, and stoichiometric mixing of components, which may increase the cost and complexity relative to conventional vaccine platforms. Another possible concern is the potential immunogenicity of the scaffold components, such as MS2 or streptavidin. If necessary, one could attempt to shield the scaffold from the immune system by using techniques such as nanopatterning46. Finally, the ability to control the orientation of HA on the VLPs depends heavily on the binding affinity and specificity of the Fab. Any variability in Fab production or binding could impact vaccine consistency.

Methods

Expression and purification of HA

The amino acid sequence for the HA ectodomain from A/Puerto Rico/8/1934(H1N1) with a C-terminal Foldon trimerization domain and a Strep-Tag II was optimized for human codon expression, synthesized, and cloned into the pcDNA3.1(-) plasmid by Gene Universal (Newark, USA). Plasmids were transformed into E. coli DH5α (New England Biolabs) and selected on LB plates supplemented with ampicillin. Colonies were then added to 5 mL of LB media with 100 μg/mL ampicillin and grown overnight. Large cultures of 100 mL of LB media with ampicillin were then started from the overnight cultures and allowed to grow overnight. Plasmids were then isolated from the 100 mL cultures using the PureLink HiPure Plasmid Filter Maxiprep Kit (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Expi293F cells were then transfected with the HA plasmid using the ExpiFectamine 293 Transfection Kit (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cultures were harvested five days after transfection, and cells were pelleted by centrifuging at 6000×g for 15 min. The supernatant was collected, filtered through a 0.45-μm filter, and applied to a Strep-Tactin XT resin (IBA Lifesciences) that had been equilibrated into StrepTrap binding buffer (100 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8) using an ÄKTA Start chromatography system (Cytiva). After the sample application, the resin was washed with 10 column volumes of StrepTrap binding buffer, and protein was eluted with 10 column volumes of StrepTrap elution buffer (100 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM biotin, pH 8). Fractions containing HA were then pooled, concentrated using an Amicon ultracentrifugal filter (Millipore Sigma) with a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff, and further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column equilibrated in PBS and an ÄKTA Pure (Cytiva).

Expression, purification, and biotinylation of H28-D14 Fab

The amino acid sequences for the variable domains of the light chain and heavy chain of the H28-D14 Fab were provided by Dr. Jonathan Yewdell of the National Institutes of Health45. DNA encoding these sequences were cloned into TGEX-LC and TGEX-FH (Antibody Design Labs) by Gene Universal (Newark, DE), with a C-terminal AviTag included upstream of the hexahistidine tag in the TGEX-FH heavy chain fragment. Plasmids were transformed into E. coli DH5α (New England Biolabs) as with HA, and the plasmid was isolated from E. coli using the PureLink HiPure Plasmid Filter Maxiprep Kit (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Expi293F cells were co-transfected with light chain and heavy chain plasmids in a 2:1 molar ratio using the ExpiFectamine 293 Transfection Kit (Thermo Fisher).

Cultures were harvested four days after transfection, and cells were pelleted by centrifuging at 6000×g for 15 min. The supernatant was twice dialyzed into PBS. Dialyzed supernatant was then mixed overnight with 1 mL of HisPur Ni-NTA resin that had been equilibrated into IMAC binding buffer (150 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 8). This mixture was then passed through a gravity flow column to recover the resin, and the resin was then washed with 90 mL of IMAC binding buffer. H28-D14 Fab was then eluted by incubating the resin with 3 mL of IMAC elution buffer (150 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 400 mM imidazole, pH 8) for 3 min before allowing the buffer to flow through the column. This elution was repeated three times in total to yield 9 mL of eluate. The eluted protein was then concentrated using an Amicon ultracentrifugal filter (Millipore Sigma) with a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff and purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column equilibrated in biotinylation buffer (20 mM Tris, 20 mM NaCl, pH 8) and an ÄKTA Pure (Cytiva).

Expression and purification of MS2

DNA encoding a single-chain dimer of the MS2 coat protein with an AviTag inserted between the 14th and 15th amino acids of the second monomer was synthesized by GenScript and cloned into pET-28b between the NdeI and XhoI sites. This plasmid was co-transformed into BL21(DE3) E. coli (New England BioLabs) with a plasmid pBirAcm (Avidity) encoding biotin ligase. Colonies were selected on LB plates supplemented with kanamycin and chloramphenicol, and colonies were added to 5 mL of 2xYT supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/mL) and chloramphenicol (20 μg/mL). After growing overnight at 37 °C, the 5 mL cultures were added to 1 L cultures of 2xYT supplemented with kanamycin and chloramphenicol and grown at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.6. MS2 production was then induced by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 1 mM. Biotin was added to a final concentration of 12.5 mg/L, and the temperature was reduced to 30 °C.

After incubating overnight, the cells were harvested by centrifuging at 7000×g for 7 min, and the cell pellet was collected. The pellet was resuspended in 25 mL of MS2 lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 0.5 mg/mL lysozyme, 5 units/mL benzonase, pH 9) together with a protease inhibitor tablet (Millipore Sigma). This suspension was incubated for 20 minutes on ice, and sodium deoxycholate was added to a final concentration of 0.1% w/v. The suspension was then sonicated at 35% amplitude for 3 minutes with pulses of 3 s on and 3 s off. The lysate was cooled for 2 min, and the sonication was then repeated. The sonicated suspension was then centrifuged at 27,000×g for 30 min, and the supernatant was collected. This supernatant was diluted to 100 mL with 20 mM Tris (pH 9) and then filtered through a 0.45-μm filter. MS2 was then purified using four HiScreen Capto Core 700 columns (Cytiva) connected in series using an ÄKTA Start (Cytiva) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Fractions containing MS2, as confirmed by SDS-PAGE, were pooled, concentrated using an Amicon ultracentrifugal filter (Millipore Sigma) with a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff, and purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column equilibrated in biotinylation buffer (20 mM Tris, 20 mM NaCl, pH 8) and an ÄKTA Pure (Cytiva).

In vitro biotinylation of H28-D14 Fab and MS2

Proteins were biotinylated using the Bulk BirA kit (Avidity). Protein concentration was adjusted to 45 μM using biotinylation buffer, and BirA and Biomix B were added to the protein according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The solution was incubated overnight at 4 °C on a nutator. A second volume of Biomix B was then added, and the mixture was shaken vigorously for 2 h at 37 °C. A third volume of Biomix B was then added, and the solution was incubated overnight again at 4 °C on a nutator. Biotinylated protein was then purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column equilibrated in PBS using an ÄKTA Pure (Cytiva).

Expression and purification of streptavidin

The expression and purification of streptavidin have been detailed previously37,40,41,44,47,48,49. The plasmid pET21-Streptavidin-Glutamate_Tag, a gift from Mark Howarth (Addgene plasmid #4636741; http://n2t.net/addgene:46367; RRID: Addgene_46367)48, was transformed into E. coli BL31(DE3) (New England BioLabs) and added to 5 mL cultures of 2xYT media supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin. Small cultures were incubated overnight at 37 °C with shaking, before being added to 1 L of 2xYT supplemented with ampicillin. Large cultures were grown at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.6–1.2 and were then induced with 1 mM IPTG.

On the following day, cell pellets were harvested by centrifuging the large cultures at 7000×g for 7 min. Cells were lysed by resuspending the cell pellet in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mg/mL lysozyme, 20 units/mL benzonase, pH 8) and then incubating for 1 h at 4 °C with shaking. Cells were then homogenized, supplemented with sodium deoxycholate to 0.1% w/v, and sonicated for 3 min at 35% amplitude with pulses of 3 s on and 3 s off. Lysate was centrifuged at 27,000×g for 15 min, and the pellet was collected. A second lysis step was completed by resuspending the pellet in benzonase-free lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mg/mL lysozyme, pH 8), incubating for 15 min at 4 °C with shaking, homogenizing, adding sodium deoxycholate to 0.1% w/v, and sonicating as in the first round. Inclusion bodies were recovered by centrifuging at 27,000×g and collecting the pellet.

Inclusion bodies were then washed three times with IB Wash Buffer 1 (50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% v/v Triton X-100, 10 mM EDTA) and followed by two washes with IB wash buffer 2 (50 mM Tris, 10 mM EDTA). Each wash consisted of resuspending the inclusion body pellet in the wash buffer, homogenizing the suspension, sonicating at 35% amplitude with a single pulse of 30 s, and then centrifuging at 27,000×g for 15 min. Following all five washes, inclusion bodies were unfolded by resuspending in pellet suspension buffer (50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8), adding guanidium hydrochloride to a final concentration of 8 M, and stirring at 25 °C for 1 h. Streptavidin was then refolded by dropwise rapid dilution into chilled PBS, after which the refolded proteins in PBS were mixed overnight at 4 °C.

Streptavidin was then purified by ammonium sulfate precipitation, followed by iminobiotin affinity chromatography (IBAC). Refolded streptavidin was centrifuged at 27,000×g for 15 min to remove insoluble debris and filtered through a 0.45-μm bottletop filter. Ammonium sulfate was slowly added to a concentration of 1.9 M to precipitate impurities, and the solution was mixed at 4 °C for 3 h. The solution was then centrifuged at 27,000×g for 15 min to precipitate impurities and again filtered through a 0.45-μm bottletop filter. Ammonium sulfate was added to a final concentration of 3.68 M to precipitate streptavidin. This solution was then mixed overnight at 4 °C, and precipitated streptavidin was collected by centrifuging at 27,000×g for 15 min.

Precipitated streptavidin was resuspended in IBAC binding buffer (50 mM sodium borate, 300 mM NaCl, pH 11) and applied to an iminobiotin agarose resin (Thermo Scientific) in a gravity flow column that had been pre-equilibrated with IBAC binding buffer. After application of the sample, the resin was washed with 20 column volumes of IBAC binding buffer, and streptavidin was eluted using 6 column volumes of IBAC elution buffer (20 mM KH2PO4, pH 2.2). After elution, the resin was regenerated by rinsing with 4 column volumes of DI water and re-equilibrating with IBAC binding buffer. IBAC purification was repeated multiple times using the sample flowthrough to increase recovery. Eluted streptavidin was then dialyzed into PBS overnight at 4 °C and concentrated to >30 mg/mL using an Amicon ultracentrifugal filter (Millipore Sigma) with a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff. Concentration was calculated by absorbance at 280 nm.

Assembly of VLP-HAinv

First, biotinylated MS2 was coated with streptavidin by adding 2.5 μL of biotinylated MS2 (<700 μg/mL) to a vigorously stirred streptavidin solution (>30 mg/mL) containing 20 times the molar excess of streptavidin. MS2-SA was purified from excess streptavidin by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column equilibrated in PBS. MS2-SA was then concentrated using an Amicon ultracentrifugal filter (Millipore Sigma) with a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff, and the concentration of streptavidin was quantified by band intensities on SDS-PAGE using a BSA standard curve.

VLP-HAinv was then assembled by first adding biotinylated H28-D14 Fab at approximately a 2:1 Fab to streptavidin ratio and incubating at 25 °C for 30 min, with the optimal concentration being confirmed using SDS-PAGE. Excess biotin binding sites on this VLP-Fab were saturated by the addition of biotin to a final concentration of 2.4 μM and incubated at 25 °C for 30 min. HA was then added in an ~1:1 HA to streptavidin ratio, with the ideal ratio being determined by analytical SEC. The final VLP-HAinv mixture was incubated for 30 min at 25 °C. VLP-HAinv was then purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column equilibrated in PBS using an ÄKTA Pure (Cytiva), taking care to avoid collecting fractions containing unbound HA. The concentration of HA in the VLP-HAinv samples was then determined by band intensities on SDS-PAGE using a BSA standard curve. If needed, samples were concentrated using an Amicon ultracentrifugal filter (Millipore Sigma) with a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff and then remeasured for concentration.

SDS-PAGE

Protein samples were first boiled at 100 °C for 30 min to disrupt streptavidin-biotin interactions. Samples were then mixed with 4x Nu-PAGE lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS) sample buffer (Invitrogen) and 40 mM dithiothreitol for denaturation and reduction. The sample mixtures were heated at 100 °C for 30 min using a thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) and loaded alongside a PageRuler Prestained Protein Ladder (Thermo Scientific) into 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen). Gels were run for 60 min at 110 V at 4 °C using 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid-SDS (MES-SDS) running buffer. Gels were then stained using Imperial Protein Stain (Thermo Fisher), destained, and imaged using the ChemiDoc MP imager (Bio-Rad).

Analytical SEC

Samples of VLP-HAinv containing 10 μg of HA at different ratios of HA to streptavidin were each diluted in PBS to 500 μL. Samples were then run on a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL size exclusion column equilibrated in PBS using an ÄKTA Pure (Cytiva), and the intensity of peaks detected at 210 nm were compared. Samples displaying an approximately 5:1 ratio between the heights of peaks corresponding to VLP-HAinv and free HA were deemed acceptable.

Expression and purification of CR6261 antibody

DNA encoding the variable regions of antibody CR6261 was cloned into TGEX-LC and TGEX-HC for their light and heavy chains, respectively. Plasmids were transformed into E. coli DH5α (New England Biolabs), and each plasmid was isolated from E. coli using the PureLink HiPure Plasmid Filter Maxiprep Kit (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Expi293F cells were co-transfected with light chain and heavy chain plasmids in a 2:1 molar ratio using the ExpiFectamine 293 Transfection Kit (Thermo Fisher). After 5 days, cells were pelleted by centrifuging at 5500×g for 20 min, and the supernatant was collected. Cleared supernatant was then diluted in PBS, and antibodies were purified with a MabSelect SuRe column (Cytiva) using an ÄKTA Start (Cytiva).

Expression and purification of stalk-only HA

DNA encoding a stalk-only HA27 with a C-terminal Foldon trimerization domain and a hexahistidine tag was codon optimized for human expression, synthesized, and cloned into the pcDNA3.1(-) plasmid by Gene Universal (Newark, USA). Plasmids were transformed into E. coli DH5α (New England Biolabs), and a purified plasmid was prepared from E. coli using the PureLink HiPure Plasmid Filter Maxiprep Kit (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Expi293F cells were transfected with the purified plasmid using the ExpiFectamine 293 Transfection Kit (Thermo Fisher). After 5 days, cells were pelleted by centrifuging at 5500×g for 20 min, and the supernatant was collected. Supernatant was twice dialyzed into PBS. Dialyzed supernatant was then mixed overnight with 1 mL of HisPur Ni-NTA resin that had been equilibrated into IMAC binding buffer (150 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 8). The resin-supernatant mixture was passed through a gravity flow column to recover the resin, and 90 mL of IMAC binding buffer was then added to wash the resin. Stalk-only HA was then eluted by incubating the resin with 3 mL of IMAC elution buffer (150 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 400 mM imidazole, pH 8) for 3 min before allowing the buffer to flow through the column. This elution was repeated three times in total to yield 9 mL of eluate. The eluted protein was then concentrated using an Amicon ultracentrifugal filter (Millipore Sigma) with a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff and purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column equilibrated in PBS using an ÄKTA Pure (Cytiva). Aliquots were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C before use.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for VLP-HAinv characterization

VLP-HAinv containing 0.1 μg of HA in 100 μL/well was coated overnight at 4 °C onto Nunc MaxiSorp flat-bottomed 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher). The coating solution was removed, and wells were blocked with 200 μL/well of 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T). The plate was incubated for 1 h at 25 °C, after which the blocking solution was removed, and the plate was washed three times with 100 μL/well of PBS-T. CR6261 or H28-D14 antibodies were diluted in 1% BSA in PBS-T and then added to each well in 100 μL/well. These antibodies were incubated for 1 h at 25 °C, after which the antibody solutions were removed. The plate was washed three times with 100 μL/well of PBS-T. HRP-conjugated goat anti-human secondary antibody (MP Biomedical #674171) was diluted 1:5000 in 1% BSA in PBS-T, and 100 μL of the secondary antibody solution was added to each well. The secondary antibodies were incubated for 1 h at 25 °C, after which the antibody solutions were removed, and the plate was washed three times with 100 μL/well of PBS-T. About 100 μL/well of TMB/E (Thermo Scientific) was added to each well, and 100 μL/well of 160 mM sulfuric acid was added 3 min later. The absorbance at 450 nm was then read using a Synergy H4 plate reader (BioTek).

Dynamic light scattering

VLP-HAinv, consisting of 10 μg of HA, was diluted in PBS to 100 μL and added to a glass-bottom plate. Measurements were recorded on a DynaPro NanoStar Dynamic Light Scattering plate reader (Wyatt Technology) controlled by Dynamics software. The temperature was equilibrated to 25 °C, and measurements were taken with 10 acquisitions each. Particle size was determined using the distribution analysis with percent mass and the isotropic spheres model.

Ethics statement

The University of Wisconsin—Madison School of Veterinary Medicine Institutional Care and Use Committee approved all animal experiments and procedures (protocol # V006426-A04). Mice were acclimated to the facility conditions (25–28 °C and 35–45% humidity with a 12 h on/off light cycle) before the start of the experiments and were given access to food and water ad libitum and enrichment. Humane endpoints for euthanasia included ≥35% body weight loss or inability to remain upright. For all animals exhibiting 25–35% body weight loss, health checks were performed at least twice daily, and water-soaked food was provided on the cage floor to support hydration and nutrition.

Immunizations

BALB/cJ mice (6–8 weeks old females, The Jackson Laboratory) were immunized by subcutaneous injection at the scruff with a 1:1 mixture of Addavax (InvivoGen) and influenza hemagglutinin (HA) protein presented on the MS2-SA VLP, an equal amount of MS2-SA VLP without the HA protein, or an equal volume of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (250 μl total volume). For PR8 challenge experiments, mice were immunized with either 7.5 µg or 15 µg of HA per dose for the prime-only vaccinations, and 2.5 µg or 5 µg HA per dose for the prime-boost regimens. For NL602 challenge experiments, mice were immunized with either 7.5 or 15 µg of HA per dose for the prime-only vaccinations, and 2.5, 5, or 10 µg HA per dose for the prime-boost regimens. For viral challenges (on day 28 for the prime-only vaccinations and day 49 for the prime-boost vaccinations), mice received intranasal inoculations using a dosage of 10x the mouse lethal dose 50 (LD50) of the respective influenza virus strains.

For NM93-H5N1 challenge experiments, mice were immunized with 10 µg of HA per dose using either a prime-boost or a three-dose regimen. For the prime-boost regimen, sera were collected on day 21 post-prime, mice were boosted on day 28, and post-boost sera were collected on day 42. In the three-dose regimen, mice received booster doses every four weeks, with sera collected on days 21, 49, and 77. Virus challenges were conducted on day 49 for the prime-boost group and on day 80 for the three-dose group. Mice were infected intranasally with 10 × LD50 of the H5N1 challenge strain.

Viruses

The viruses used herein include influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1; “PR8”) and A/Netherlands/602/2009 (H1N1; “NL602”), which were grown in embryonated chicken eggs, and A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1; “NM93-H5N1”12).

Blood collection and processing

Mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane, blood was collected from the submandibular vein (~100 μl/mouse), and then the mice were returned to their cages. Blood was immediately transferred to serum separator tubes, centrifuged at 2000×g for 10 min, and the separated serum was frozen at −80 °C until further use.

Biosafety

Experiments with NM93-H5N1 were carried out in Biosafety Level 3 (BSL-3) containment laboratories at the Influenza Research Institute at the University of Wisconsin—Madison, which is approved by the Federal Select Agent Program for studies with these viruses. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee of the University of Wisconsin—Madison, and all animal experiments were approved by the University of Wisconsin—Madison School of Veterinary Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The grant for the studies conducted was reviewed by the University of Wisconsin–Madison Dual Use Research of Concern (DURC) Subcommittee in accordance with the May 2024 United States Government Policy for Oversight of Dual Use Research of Concern and Pathogens with Enhanced Pandemic Potential and determined not to meet the criteria of DURC or PEPP. The University of Wisconsin—Madison Institutional Contact for Dual Use Research reviewed this manuscript and confirmed that the studies described herein do not meet the criteria of DURC.

Mouse infections

Previously immunized or mock-immunized BALB/cJ mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal (i.p) injection of ketamine and dexmedetomidine (45–75 mg kg−1 ketamine + 0.25–1 mg kg−1 dexmedetomidine) and infected by intranasal inoculation (25 ul/each nostril) with ten mouse lethal dose 50 (LD50) of the indicated virus diluted in PBS. To reverse the effects of dexmedetomidine, atipamezole (0.1–1 mg kg−1) was administered by i.p. injection. Animals were monitored daily for signs of illness, and body weights were recorded for 14–21 days. Mice were euthanized if they lost ≥35% of their initial body weight or could not remain upright.

Microneutralization assay

Mouse serum was treated with three times the volume of receptor-destroying enzyme (RDE; Denka Seiken Co.) at 37 °C for 18 h, heat-inactivated by incubating at 56 °C for 1 h, adsorbed with turkey red blood cells for 1 h at room temperature on a rotating mixer, and then centrifuged (3000 rpm, 4 °C for 5 min) to collect supernatants. RDE-treated sera were twofold serially diluted and incubated with the respective viruses (100 plaque-forming units per 50 μl) in virus growth medium (Eagle’s minimum essential medium containing 0.3% bovine serum albumin and 0.6 µg/ml L-(tosylamido-2-phenyl) ethyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin; ‘MEM-BSA’) for 1 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, 100 μl of the virus-serum mixtures were transferred to Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells and incubated for 4 to 5 days at 37 °C. Cells were observed daily by light microscopy, and cytopathic effects (CPE) were recorded. The microneutralization (MN) titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of serum showing less than 50% CPE.

ELISA for mouse serum against heterosubtypic HA

IgG antibody endpoint titers elicited were determined by ELISA using Immulon 2 HB plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rochester, NY) coated with 1 μg/ml of protein diluted in carbonate buffer (0.2 M sodium carbonate/sodium bicarbonate) as described50. For heterosubtypic reactivity, the HA recombinant protein from A/dairy cow/Texas/24-008749-002-v/2024(H5N1) was purchased from SinoBiological (Wayne, PA). The wells were blocked with a blocking buffer (1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS and 0.05% Tween 20) for 2 h at 37 °C. Then, duplicates of serum diluted in PBS with 0.5% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20 were added. After incubating the plates with sera for 1 h at 37 °C, the plates were washed and incubated with Peroxidase-labeled affinity-purified anti-mouse total IgG (SeraCare, Milford, MA). After washing, the bound antibodies were detected using KPL Sure Blue Reserve™ TMB Microwell Peroxidase Substrate (SeraCare, Milford, MA). The peroxidase reaction was stopped with the KPL TMB Stop Solution (SeraCare, Milford, MA), and optical densities were determined using a VERSAmax ELISA reader (Molecular Devices, LLC, San Jose, CA) with a 450-nm filter. Antibody titers were determined by curve fitting using a four-parameter logistic regression in GraphPad Prism 10.4.1 using a cutoff of the mean absorbance plus three standard deviations of pre-immune samples (OD450 = 0.2). For the highest tested dilution with an absorbance below the cutoff, we established a lower limit by dividing the initial dilution by the dilution factor used in the experiment.

Statistics and reproducibility

All animals were randomly allocated to experimental groups, and no blinding was performed in any experiment. Animal experiments were performed one time each with sample sizes based on our previous work. Survival curves were compared by using a log-rank Mantel–Cox test. Endpoint titers were compared with the Mann–Whitney U-test. Statistics and graphs in Figs. 2, 5 were prepared with GraphPad Prism software, version 10.4.2. Statistics and graphs in Figs. 3, 4 were prepared with GraphPad Prism software, version 10.1.0.

Data availability

The data that support the conclusions of this study are included in the article, Supplementary Information, and Supplementary Data 1 file.

References

Cozza, V. et al. Global seasonal influenza mortality estimates: a comparison of 3 different approaches. Am. J. Epidemiol. 190, 718–727 (2020).

Kim, Y.-H., Hong, K.-J., Kim, H. & Nam, J.-H. Influenza vaccines: past, present, and future. Rev. Med. Virol. 32, e2243 (2022).

Buckland, B. et al. Technology transfer and scale-up of the Flublok® recombinant hemagglutinin (HA) influenza vaccine manufacturing process. Vaccine 32, 5496–5502 (2014).

Yang, L. P. H. Recombinant trivalent influenza vaccine (Flublok®): a review of its use in the prevention of seasonal influenza in adults. Drugs 73, 1357–1366 (2013).

Moody, M. A. et al. H3N2 influenza infection elicits more cross-reactive and less clonally expanded anti-hemagglutinin antibodies than influenza vaccination. PLoS ONE. 6, e25797 (2011).

Wrammert, J. et al. Rapid cloning of high-affinity human monoclonal antibodies against influenza virus. Nature 453, 667–671 (2008).

Margine, I. et al. H3N2 influenza virus infection induces broadly reactive hemagglutinin stalk antibodies in humans and mice. J. Virol. 87, 4728–4737 (2013).

Heaton, N. S., Sachs, D., Chen, C.-J., Hai, R. & Palese, P. Genome-wide mutagenesis of influenza virus reveals unique plasticity of the hemagglutinin and NS1 proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 20248–20253 (2013).

Thyagarajan, B. & Bloom, J. D. The inherent mutational tolerance and antigenic evolvability of influenza hemagglutinin. eLife 3, e03300 (2014).

Brandenburg, B. et al. Mechanisms of hemagglutinin targeted influenza virus neutralization. PLoS ONE 8, e80034 (2013).

Kirkpatrick, E., Qiu, X., Wilson, P. C., Bahl, J. & Krammer, F. The influenza virus hemagglutinin head evolves faster than the stalk domain. Sci. Rep. 8, 10432 (2018).

Eisfeld, A. J. et al. Pathogenicity and transmissibility of bovine H5N1 influenza virus. Nature 633, 426–432 (2024).

Gu, C. et al. A human isolate of bovine H5N1 is transmissible and lethal in animal models. Nature 636, 711–718 (2024).

Uyeki, T. M. et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus infection in a dairy farm worker. N. Engl. J. Med. 390, 2028–2029 (2024).

Lin, T.-H. et al. A single mutation in bovine influenza H5N1 hemagglutinin switches specificity to human receptors. Science 386, 1128–1134 (2024).

Dadonaite, B. et al. Deep mutational scanning of H5 hemagglutinin to inform influenza virus surveillance. PLoS Biol. 22, e3002916 (2024).

Roubidoux, E. K. et al. Mutations in the hemagglutinin stalk domain do not permit escape from a protective, stalk-based vaccine-induced immune response in the mouse model. mBio, 12, e03617–e03620 (2021).

Ekiert, D. C. & Wilson, I. A. Broadly neutralizing antibodies against influenza virus and prospects for universal therapies. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2, 134–141 (2012).

Ekiert, D. C. et al. Antibody recognition of a highly conserved influenza virus epitope. Science 324, 246–251 (2009).

Throsby, M. et al. Heterosubtypic neutralizing monoclonal antibodies cross-protective against H5N1 and H1N1 recovered from human IgM+ memory B cells. PLoS ONE 3, e3942 (2008).

Tan, G. ene et al. A Pan-H1 anti-hemagglutinin monoclonal antibody with potent broad-spectrum efficacy in vivo. J. Virol. 86, 6179–6188 (2012).

Doud, M. B., Lee, J. M. & Bloom, J. D. How single mutations affect viral escape from broad and narrow antibodies to H1 influenza hemagglutinin. Nat. Commun. 9, 1386 (2018).

Impagliazzo, A. et al. A stable trimeric influenza hemagglutinin stem as a broadly protective immunogen. Science 349, 1301–1306 (2015).

Lu, Y., Welsh, J. P. & Swartz, J. R. Production and stabilization of the trimeric influenza hemagglutinin stem domain for potentially broadly protective influenza vaccines. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 125–130 (2014).

Mallajosyula, V. V. A. et al. Influenza hemagglutinin stem-fragment immunogen elicits broadly neutralizing antibodies and confers heterologous protection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, E2514–E2523 (2014).

Valkenburg, S. A. et al. Stalking influenza by vaccination with pre-fusion headless HA mini-stem. Sci. Rep. 6, 22666 (2016).

Yassine, H. M. et al. Hemagglutinin-stem nanoparticles generate heterosubtypic influenza protection. Nat. Med. 21, 1065–1070 (2015).

Deng, L. et al. Double-layered protein nanoparticles induce broad protection against divergent influenza A viruses. Nat. Commun. 9, 359 (2018).

Corbett, K. S. et al. Design of nanoparticulate group 2 influenza virus hemagglutinin stem antigens that activate unmutated ancestor B cell receptors of broadly neutralizing antibody lineages. mBio, https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.02810-18 (2019).

Moin, S. M. et al. Co-immunization with hemagglutinin stem immunogens elicits cross-group neutralizing antibodies and broad protection against influenza A viruses. Immunity 55, 2405–2418.e2407 (2022).

Sutton, T. C. et al. Protective efficacy of influenza group 2 hemagglutinin stem-fragment immunogen vaccines. npj Vaccines 2, 35 (2017).

Widge, A. T. et al. An influenza hemagglutinin stem nanoparticle vaccine induces cross-group 1 neutralizing antibodies in healthy adults. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eade4790 (2023).

Krammer, F., Pica, N., Hai, R., Margine, I. & Palese, P. Chimeric hemagglutinin influenza virus vaccine constructs elicit broadly protective stalk-specific antibodies. J. Virol. 87, 6542–6550 (2013).

Nachbagauer, R. et al. A chimeric hemagglutinin-based universal influenza virus vaccine approach induces broad and long-lasting immunity in a randomized, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Nat. Med. 27, 106–114 (2021).

Eggink, D., Goff, P. H. & Palese, P. Guiding the immune response against influenza virus hemagglutinin toward the conserved stalk domain by hyperglycosylation of the globular head domain. J. Virol. 88, 699–704 (2014).

Kim, D. et al. Tethered antigenic suppression shields the hemagglutinin head domain and refocuses the antibody response to the stalk domain. Chemistry 7, 12 (2025).

Frey, S. J. et al. Nanovaccines displaying the influenza virus hemagglutinin in an inverted orientation elicit an enhanced stalk-directed antibody response. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 12, 2202729 (2023).

Xu, D. et al. Vaccine design via antigen reorientation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 20, 1012–1021 (2024).

Frietze, K. M., Peabody, D. S. & Chackerian, B. Engineering virus-like particles as vaccine platforms. Curr. Opin. Virol. 18, 44–49 (2016).

Chiba, S. et al. Multivalent nanoparticle-based vaccines protect hamsters against SARS-CoV-2 after a single immunization. Commun. Biol. 4, 597 (2021).

Castro, A., Carreño, J. M., Duehr, J., Krammer, F. & Kane, R. S. Refocusing the immune response to selected epitopes on a Zika virus protein antigen by nanopatterning. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 10, 2002140 (2021).

Valegård, K., Murray, J. B., Stockley, P. G., Stonehouse, N. J. & Liljas, L. Crystal structure of an RNA bacteriophage coat protein–operator complex. Nature 371, 623–626 (1994).

Halfmann, P. J. et al. Multivalent S2-based vaccines provide broad protection against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and pangolin coronaviruses. eBioMedicine 86, 104341 (2022).

Halfmann, P. J. et al. Multivalent S2 subunit vaccines provide broad protection against Clade 1 sarbecoviruses in female mice. Nat. Commun. 16, 462 (2025).

Angeletti, D. et al. Defining B cell immunodominance to viruses. Nat. Immunol. 18, 456–463 (2017).

Arsiwala, A. et al. Nanopatterning protein antigens to refocus the immune response. Nanoscale 11, 15307–15311 (2019).

Halfmann, P. J. et al. Broad protection against clade 1 sarbecoviruses after a single immunization with cocktail spike-protein-nanoparticle vaccine. Nat. Commun. 15, 1284 (2024).

Fairhead, M., Krndija, D., Lowe, E. D. & Howarth, M. Plug-and-play pairing via defined divalent streptavidins. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 199–214 (2014).

Howarth, M. & Ting, A. Y. Imaging proteins in live mammalian cells with biotin ligase and monovalent streptavidin. Nat. Protoc. 3, 534–545 (2008).

Fonseca, J. A. et al. A chimeric protein-based malaria vaccine candidate induces robust T cell responses against Plasmodium vivax MSP119. Sci. Rep. 6, 34527 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a grant to R.S.K., A.M., and G.N. from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI168408-01A1). R.S.K. acknowledges support from the Garry Betty/V Foundation Chair Fund. This manuscript is also based in part upon work (by D.K. and K.L.) supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE-2039655. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF. A.D. was supported by the T32 Research Training Program in Immunoengineering from the National Institutes of Health (T32 EB021962). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.L., D.K., A.D., H.H., and A.S. purified, assembled, and characterized the vaccines. A.J.E., A.B., and H.H.A. conducted animal experiments and neutralization assays. A.M. conducted antibody endpoint titer assays. A.M., G.N., Y.K., and R.S.K. acquired funding and provided supervision. D.K., A.D., and R.S.K. wrote the initial draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: Y.K. has received unrelated funding support from Daiichi Sankyo Pharmaceutical, Toyama Chemical, Tauns Laboratories, Inc., Shionogi & Co., Ltd, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, KM Biologics, Kyoritsu Seiyaku, Shinya Corporation, and Fuji Rebio. Y.K. and G.N. are co-founders of FluGen. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Biswas, A., Loeffler, K., Kim, D. et al. Inverted H1 hemagglutinin nanoparticle vaccines protect mice against challenges with human H1N1 and bovine H5N1 influenza viruses. npj Vaccines 10, 225 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01276-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01276-w