Abstract

Chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu) becomes a health concern in developing countries. It is urgent to recognize CKDu-related groundwater in CKDu-prevalent areas. Here, spectral indices showed that DOM from CKDu groundwater was characterized by higher molecular weight, stronger exogenous feature, and greater degree of humification and unsaturation than from non-CKDu groundwater. Parallel factor analysis of fluorescence spectra showed that DOM from CKDu groundwater contained significantly more humic-like substances (C1%) and less protein-like substances than from non-CKDu groundwater. Furthermore, C1% was correlated with concentrations of inorganic chemicals associated with CKDu, indicating the feasibility of using C1% for probing CKDu groundwater. According to our self-developed method, both the non-CKDu probability of groundwater with C1% less than the recognizing threshold (RT, 28.8%) and the CKDu probability of groundwater with C1% larger than RT are 70.1%. This indicates that the C1%-based method is a feasible tool for recognizing CKDu groundwater.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease affects ~15% of population worldwide and is one of the global public health problems1. Hypertension, diabetes, and chronic nephritis are usually the main causes of chronic kidney disease2. However, a chronic kidney disease that is unrelated to the above-mentioned causes, namely chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu), has been reported in Central America, India, Sri Lanka, and other places3. In Sri Lanka, the health of more than 400,000 people is threatened by CKDu, and the incidence of CKDu is as high as 15–23% in North Central Province4,5. Most patients suffering from CKDu have a low standard of living in agricultural communities in arid regions6. In recent years, many studies have shown that CKDu is associated with groundwater quality5,7, and there are not enough infrastructures to provide purified drinking water. According to a survey, in CKDu-prevalent areas, the occurrence of CKDu is dependent on the quality of drinking groundwater for local residents, and the distributions of clean groundwater sources and CKDu-related groundwater sources were uneven8. Therefore, the recognition of clean groundwater sources has become an urgent action taken for the residents in CKDu-prevalent areas in developing countries such as Sri Lanka5.

The inorganic chemicals of groundwater have been identified to be related to the prevalence of CKDu in many studies9,10. For example, F− concentrations in groundwater samples from CKDu-prevalent areas in Sri Lanka, mostly exceed the threshold level (0.6 mg L−1) defined for World Health Organization9; the hardness and the ratio of Ca2+ to Na+ in groundwater from CKDu-endemic areas are also higher than those in non-CKDu areas10,11. In addition, CKDu is associated with the concentrations of heavy metals with nephrotoxicity (e.g., Cd and Pb) and Si in groundwater12,13,14. A recent study has shown that organic compounds can interact with Ca2+ and SO42− through complexation, and the complex is harmful to human kidneys15. The formation of certain kidney diseases is related to dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in groundwaters16. Excessive humic substances can cause the death of human kidney cells based on a study in endemic areas of kidney disease of Balka17. However, few studies have investigated the difference in the key components of dissolved organic matter (DOM) between CKDu and non-CKDu water sources. The studies available showed that DOM in groundwater from CKDu-endemic areas was more refractory, higher aromatic, and lower bioavailable than that from non-CKDu areas18,19. However, it is still unknown how significant the sensitive components of DOM are in recognizing CKDu-related water sources.

Excitation-mission matrix spectroscopy (EEM) has the advantages of fast measurement, high sensitivity, and easy preprocessing. It has been widely used to characterize the fluorescent DOM (FDOM)20. EEM coupled with parallel factor analysis (EEM-PARAFAC) can effectively reveal optical characteristics of DOM, identify the fluorescent components and sources of DOM, and clarify the transformation process of DOM21,22. Furthermore, it also can be applied to explore the dynamic changes of DOM affected by natural and human factors23,24. EEM−PARAFAC has the potential feasibility to investigate the association between DOM and groundwater quality20.

Therefore, this study aimed to (1) determine the optical characteristics, composition, and sources of FDOM in CKDu-related and CKDu-unrelated groundwater from Sri Lanka by EEM-PARAFAC technique, (2) verify the feasibility of using key fluorescent components to identify CKDu-related water sources by combining with inorganic sensitive chemicals, and (3) propose an early warning and screening tool for CKDu-related groundwater sources utilizing key fluorescent components. This study will provide an effective method for ensuring the safety of drinking water, which is helpful for the prevention and traceability of CKDu.

Results and discussion

DOC and EEMs of DOM in CKDu-related groundwater

DOC concentrations (3.25 ± 0.73 mgC L−1) in CKDu groundwater were significantly lower than those in surface water (4.65 ± 0.89 mgC L−1), but significantly higher than those in non-CKDu groundwater (2.81 ± 0.76 mg L−1) (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Although DOC concentrations reported by Cooray et al.25 were greater than the observed data in this study, they also found relatively higher DOC concentrations (6.4 mgC L−1) in CKDu-prevalent regions than in non-CKDu-prevalent regions (3.7 mgC L−1). There may be two reasons for the difference in the DOC concentrations between CKDu groundwater and non-CKDu groundwater. One is that CKDu groundwaters are likely to receive more surface water recharge11,26, which increases DOC concentration27,28. The other is that stronger microbial activity in non-CKDu groundwater (Fig. 1E, Supplementary Fig. 3) would degrade more organic substances into inorganic substances29, which is discussed below.

The upper point of the black box is the maximum and the lower is the minimum; the upper boundary of the black box is the 75th percentile and the lower is the 25th percentile, and the middle white square is the average value. The density diagram outside the box diagram represents the density probability. The significant difference of p < 0.01 and the significant difference of p < 0.05 have been marked with two asterisks and an asterisk in spectral indices between two different groups, respectively.

The a254 values in CKDu groundwater (median: 5.07 m−1) were higher than those in non-CKDu groundwater (median: 4.38 m−1) (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that DOM of CKDu groundwater consists of more unsaturated DOM. Generally, the concentrations of unsaturated DOM (a254) in natural groundwater were less than 1 m−1 30,31,32. In this study, the lowest a254 value in all groundwater samples was 1.15 m−1 (Supplementary Table 1), indicating that both CKDu and non-CKDu groundwater may be contaminated to some extent. Compared with groundwater, surface water had higher a254 values (median:10.48 m−1), which would result from anthropogenic activities. In addition, there is a significant positive correlation between DOC concentrations and a254 (Supplementary Fig. 4), indicating that the increase of DOC might be attributed to anthropogenic input.

The EEM features of DOM from non-CKDu groundwater were different from those from CKDu groundwater and surface water (Supplementary Fig. 5). The EEM of non-CKDu groundwater presented relatively stronger T peak signal, but weaker A peak signal (Supplementary Table 2) relative to CKDu groundwater, which indicated that non-CKDu groundwater contained more bioactive tryptophan-like substances33,34. Conversely, the peak A region in the EEMs of DOM from CKDu groundwater and surface water was extended into a plateau between the peaks M and C, indicating the dominant role of humic-like organic matter in CKDu groundwater and surface water. Furthermore, the similar EEMs feature of DOM between CKDu groundwater and surface water indicated that groundwater-surface water interaction may have occurred and surface water was recharging groundwater.

Spectral indices of DOM in CKDu-related groundwater

As shown in Fig. 1, in terms of DOM aromaticity (SUVA254), CKDu groundwater (mean: 0.78 ± 0.37) was similar to non-CKDu groundwater (mean: 0.78 ± 0.33) (p > 0.05). However, several CKDu groundwater samples exhibited high DOM aromaticity, which is related to their high a254 (Supplementary Fig. 4). The significant positive correlation between a254 and SUVA254 indicated that the aromatic DOM dominated over the unsaturated DOM. The spectral slope (S275–295) of CKDu groundwater (mean: 20.5 ± 6.7) was relatively lower than non-CKDu groundwater (mean: 23.7 ± 9.4), indicating that CKDu groundwater are enriched with high-molecular-weight organic matter. It can be attributed to the stronger microbial activities35 in non-CKDu groundwater with relatively higher biological index (BIX) values (Fig. 1E). Microorganisms might decompose high-molecular-weight OM like lignin into low-molecular-weight OM like aromatic compounds36,37.

The fluorescence index (FI) of DOM in all samples ranged from 1.26 to 1.88, indicating the weaker autochthonous feature and a mixture of terrestrial and microbial origins. However, the FI of DOM in non-CKDu groundwater (mean: 1.64 ± 0.12) was relatively greater than that in CKDu groundwater (mean: 1.52 ± 0.17), indicating that DOM of CKDu groundwater contains more allochthonous organic matter and less indigenous organic matter. In general, flowing groundwater has a stronger terrestrial signal than stagnant groundwater38,39. Consequently, CKDu groundwater with lower FI might be of better flowing condition. There were no differences between non-CKDu groundwater and surface water in term of FI. As shown in Fig. 1E, the BIX values in CKDu groundwater (mean: 0.81 ± 0.09) and surface water (mean: 0.79 ± 0.08) were significantly lower than those in non-CKDu groundwater (mean: 0.86 ± 0.08) (p < 0.05), suggesting that DOM of non-CKDu groundwater performs a feature of relatively higher biological activity40,41, which was in accordance with the FI. There is a positive correlation between FI and BIX, which is consistent with observations by Dalmagro et al.42 and Qi et al.43. BIX was preferred in discriminating biological activity of DOM between groundwater and surface water44.

The humification index (HIX) of DOM in CKDu groundwater (mean: 4.36 ± 2.16) was significantly higher than that in non-CKDu groundwater (mean: 3.15 ± 1.49) (p < 0.01), showing the greater humification degree of DOM in CKDu groundwater. This may be caused by surface water replenishing the CKDu groundwater or the stronger microbial activity of non-CKDu groundwater40,45. The increase in humification degree corresponds with the decrease in H/C44. These organic matter with low H/C mainly consisted of hydrophobic aromatic compounds or unsaturated compounds46. Thence, DOM of CKDu groundwater would contain more hydrophobic aromatic or unsaturated compounds, which tends to be stable and persistent. Zheng et al.18 and Makehelwala et al.19 also showed that DOM in groundwater from CKDu-endemic areas contained more fulvic acid and other macromolecular hydrophobic humus.

The correlation between FI and HIX was not significant in this study (Supplementary Fig. 6). Therefore, source identification based on the HIX was not in accordant with that based on FI and BIX (Supplementary Fig. 3). The decoupling between the FI and HIX might be caused by the complex hydrogeological conditions and anthropogenic factors20. For instance, endogenous organic matter might be released from sediments and/or rocks due to water-rock interaction47.

Although the spectral indices can help to quickly assess the composition of DOM, all indices are calculated using fixed wavelengths13, which are susceptible to the influence of multiple interacting fluorophores, leading to “distortion” when evaluating the composition of complex organic compounds from mixed sources48. Thus, the interpretation of fluorescence indicators should be cautious, and PARAFAC needs to be used for further analysis.

Sensitive FDOM components in CKDu-related groundwater

Four fluorescent components were extracted and passed half-split validation (Supplementary Fig. 7, Supplementary Table 3). C1 was terrestrial humic-like components produced through biogeochemical processing of terrestrial particulate organic matter49, which resembled a combination of Coble A and C peaks50; C2 was similar to Coble M peak, microbial humic-like components with low molecular weight, and might dominate the fluorescence DOM of wastewater51,52; C3 was humic-like components with high molecular weight, which is derivatives of terrestrial organic material51,53; C4 was autochthonous protein-like components attributed to microbial activity54,55.

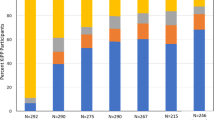

FDOM was predominated by C1 and C2 with abundance of 68.7% and 62.9% in CKDu and non-CKDu groundwater, respectively (Fig. 2), indicating the dominative role of humic-like substances. The relative abundance of C1 (C1%, 35.1%) in CKDu groundwater was significantly higher than that in non-CKDu groundwater (28.0%, p < 0.01), while the C2% and C3% in CKDu and non-CKDu groundwater were similar (p > 0.05). Due to the similar geological and irrigation conditions in the study area, C2 is likely to be by-product organic matter produced by in-situ microbial activities or some humic substances that were fractionated by minerals easily56, and C3 may be related to the input of agricultural materials57. Furthermore, significantly higher C4% was detected in the DOM from non-CKDu groundwater (23.8%) than that of the DOM in CKDu groundwater (17.3%, p < 0.01), indicating the greater bioavailability of DOM from non-CKDu groundwater. The lower pH values of non-CKDu groundwater support this speculation (Supplementary Table 4), because proton is produced during microbial degradation of organic matter58,59. C1% in surface water was significantly higher than that in non-CKDu groundwater (p < 0.01), but similar to that in CKDu groundwater (p > 0.05), indicating that the increase in C1% in CKDu groundwater may be related to the input of surface water.

The upper point of the box chart is the maximum and the lower is the minimum; the upper boundary of the box is the 75th percentile, and the lower is the 25th percentile; the middle horizontal line is the median value, and the middle square is the average value. The significant difference of p < 0.01 and the significant difference of p < 0.05 have been marked with two asterisks and an asterisk between two different groups, respectively.

The two-component principal component analysis showed that the loadings of C1% were located in the positive direction of PC1, which accounted for 43.9% of the variances, and the loadings of C4% were laid on the negative direction of PC1 (Fig. 3). Samples close to the positive direction of PC1 generally had high abundance of humic-like substances, and samples close to the negative axis of PC1 generally had high proportion of protein-like components related to microbial activities. Notably, around 50% CKDu groundwater samples and only around 22% of non-CKDu groundwater samples were located on the positive direction of PC1. It showed that CKDu groundwater and non-CKDu groundwater could be distinguished effectively by C1% and C4%. However, C4 seemed to be susceptible to interference from microbial background in aquifers resulting in deviations of screening20. Thus, C1 with better stability and persistence in the environment60, can be preferably used to recognize CKDu groundwater. Meanwhile, HIX, a254, and SUVA254 presented positive loadings to PC1, indicating their association with humic-like substances (C1). For PC2 (22.2%), C2% and C3% were placed in the positive direction. Around 53% of CKDu groundwater samples and 28% of non-CKDu groundwater samples were located in the negative direction of PC2. However, considering the similar C2% and C3% between CKDu groundwater and non-CKDu groundwater, the recognition of CKDu groundwater by C2% and C3% can be misleading.

Relationship between DOM and CKDu-related water chemistry

Excessive intake of F− can damage human kidney tissue, and therefore high F− concentration is considered as a sign of the water sources leading to CKDu11,61. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8, there was a significant positive correlation between C1% and F− concentration in groundwater samples (r = 0.62, p < 0.05), indicating that C1 is a sensitive component for recognizing groundwater sources that can cause CKDu. The C1% also had significantly positive correlations with Ca2+ (r = 0.60, p < 0.05). C1 with carboxyl is likely to combine with Ca2+ to form a complex that is harmful to the human kidney15, which is an important cause of CKDu. This is in line with the observation that groundwater in CKDu-endemic areas contained higher concentrations of Ca2+ than groundwater in non-CKDu-endemic areas10,18. In addition, C1% increased with the increases in Si concentrations and hardness (r = 0.60, 0.61, respectively, p < 0.05) in this study. It is believed that CKDu is also related to groundwater with high hardness and high Si concentrations, because drinking this groundwater may damage human embryonic kidney cells12,14. In summary, C1% was positively correlated with the inorganic chemical components generally considered to be associated with CKDu, indicating the potential feasibility of using C1% as a recognizing indicator to identify CKDu-related groundwater sources.

It is supposed that the larger C1% in CKDu groundwater versus in non-CKDu groundwater was related to the input of surface water (Fig. 2). In fact, the concentrations of the above-mentioned inorganic chemical components in surface water were much lower than those in groundwater (Supplementary Table 4). Considering that weathered fissure water in the study area is main groundwater resources, the process of surface water replenishing groundwater is slow, which causes strong water-rock interactions (e.g., leaching and ion exchange) during the replenishment process and leads to the enrichment of inorganic chemicals in groundwater. For instance, due to the chemical similarity of F− and OH−, higher pH value in surface water is likely to cause more F− desorbed from the minerals by ion exchange during the process of recharge62, which results in relatively lower pH value and more F− in CKDu groundwater than those in surface water.

Recognizing CKDu-related water sources by FDOM

In this study, DOM between CKDu groundwater and non-CKDu groundwater was of significant differences in terms of C1% and HIX, and therefore these differences can be used for early warning and rapid recognizance of water sources associated with CKDu through our self-developed CKDu recognizing threshold assessment (CRTA) method. To explore the suitable recognizing threshold (RT) of various DOM indicators and test the applicability of CRTA method, the relationships between the assumed threshold of DOM indicators and the detection probability of CKDu groundwater (DPC) and the detection probability of non-CKDu groundwater (DPN) in groundwater samples (n = 54) are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. It was found that DPC and DPN responded to the changes of HIX, C1%, DOC, and C4% very well with approximately S-shaped curves. Taking C1% as an example, when the assumed threshold of C1% exceeded the value at the intersection (28.8%) of DPC and DPN curves, DPC increased with the increase in C1% and was always greater than DPN; when the assumed threshold of C1% was less than the intersection value (28.8%), DPN increased with the decrease in C1% and was always larger than DPC. That is, if the assumed threshold of C1% at the intersection is used as RT, DPC will arrive at 70.1% (detection probability at the intersection) at least with C1% above RT (Supplementary Table 5), indicating that the possibility of detected water source as CKDu-related source was at least 70.1%. When the assumed threshold of C1% is below RT, DPN will exceed 70.1%, indicating that the possibility of detected water source as non-CKDu-related source was at least 70.1%. Therefore, by using the RT of C1%, the probability to identify whether one water source is CKDu-related or non-CKDu-related is at least 70.1%, indicating its very good recognizing applicability.

Similarly, the relationships between the assumed thresholds of HIX, the concentrations of DOC, and C4% and the detection probability were the same as the relationship between the assumed threshold of C1% and the detection probability. However, due to the relatively lower detected probability at the intersection (Supplementary Table 5), the recognizing applicability using HIX, DOC, and C4% is not so good as C1%. In terms of other DOM indicators, their DPN or DPC curves fluctuated much with changes in thresholds. In addition, according to the relationship between the assumed threshold of PC1 score and the detection probability, it can be found that the recognizing probability by using PC1 score was 63.8%.

The assumed thresholds of C1%, C4%, HIX, and PC1 score versus detection probability were fitted by empirical Boltzmann equation (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 4, the assumed threshold of C1% had the highest coefficient of determination (R2) (Supplementary Table 6). Verification results showed that the predicted values were close to the measured values (Fig. 5), indicating that the fitting results were valid. In addition, paired t test showed that the predicted value and measured value were not significantly different (p > 0.05) only using C1% or score of PC1 as recognizing indicators. Root mean square error (RMSE) of C1% was also the lowest, indicating that the fitting result of C1% was in line with the data of this study area. Above all, C1% is the most suitable and effective DOM index for distinguishing CKDu-related water sources from non-CKDu-related water sources through CRTA method.

Red lines indicate the DPC, and blue lines indicate DPN. The detection probability of the solid lines was calculated using the set arithmetic sequence as the threshold, while the dashed lines were the fitting results of solid lines; and the pink bands were the 95% confidence interval of the fitting curves.

According to the functions of fitting curves, the RT of C1% using CRTA method was 28.8%. In order to clarify the predictability and the advantage of the optimal threshold calculated by CRTA method, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and precision-recall (P-R) curve based on confusion matrix were also performed using the same 54 groundwater samples (Supplementary Figs. 10, 11). In ROC and P-R analysis, the curve model was considered to have predictability only when the area under curve (AUC) was greater than 0.763. Typically, the larger AUC indicated the better predictability of the model. The AUC of ROC curve (0.777) and P-R curve (0.816) of C1% were larger than those of other DOM indices, indicating that C1% was the most suitable as recognizing index, which is consistent with the results of CRTA method. However, according to the maximum of Yonden’s index, which was positively correlated with the superiority of screening models (Supplementary Method), the optimal RT of C1% in ROC curve was 36.3%; the optimal RT of C1% in P-R curve was 27.6% by using the maximum of F1-score, which is harmonic average of precision and recall and indicates the capacity of predicting correctly. To compare the predictability of P-R curve, ROC curve, and CRTA method using C1% as recognizing index, these RT were applied to 21 groundwater samples for verification to obtain actual predictability (Supplementary Table 7). The predictability for CKDu groundwater using CRTA method (75.0%) was consistent with that of P-R curve (75.0%), but higher than that of ROC curve (50.0%); the predictability for non-CKDu groundwater using CRTA method (66.7%) was higher than that of P-R curve (55.6%), but lower than that of ROC curve (88.9%). For the better comparison, the geometric mean of the predictability for non-CKDu groundwater and the predictability for CKDu groundwater were used to show comprehensive predictability. The comprehensive predictability of CRTA method (70.7%) was the highest, followed by ROC curve (66.7%) and P-R curve (64.5%). This illustrated that CRTA method obtained better RT of C1% for screening CKDu groundwater and non-CKDu groundwater than ROC curve and P-R curve. In addition, the AUC of P-R curve of PC1 score was 0.700, indicating that PC1 can also be used as a recognizing index, although the AUC of ROC curve of PC1 score was less than 0.7. Compared with the RT of PC1 score obtained by CRTA method, the optimal RT of PC1 score obtained by P-R curve had same actual predictability for non-CKDu groundwater, but lower actual predictability for CKDu groundwater. Therefore, in recognizing CKDu groundwater and non-CKDu groundwater, CRTA method seemed to be more advantageous than P-R curve and ROC curve.

Environ-geological health implication of CRTA

In this study, DOM characteristics of CKDu-related groundwater were probed by using DOM optical indices, and discriminating CKDu-unrelated versus CKDu-related groundwater was achieved by providing a reasonable probability-based guideline for setting the threshold of an indicator. This will contribute to excavating and recognizing clean groundwater sources for low-income residential areas. To improve drinking water quality and prevent CKDu, the reverse osmosis and nanofiltration technology were proposed to treat contaminated water14,18, though these technologies require good economic conditions and are hardly applied to actual production. As described in above section, C1% recognized by CRTA is a feasible and reasonable indicator for screening CKDu groundwater with low cost. In practice, for each indicator, it is needed to determine which functions of fitting curve are chosen by comparing the measured value and RT, and then calculate DPC or DPN through the selected function. With CRTA method, screening CKDu-related water sources by C1% of FDOM improves the security of drinking water and prevents the occurrence of CKDu in CKDu-prevalent areas. The RT of C1% may be influenced by some environmental factors (e.g., hydrological and geological conditions). In the future, more studies on dissolved organic matter in groundwater are needed in other typical CKDu-endemic regions to test and broad the applicability of CRTA.

It is worth mentioning that the application of CRTA method is not limited to sensitive FDOM indicators. Most previous studies have also emphasized that inorganic chemicals like Ca2+, F−, hardness, and Si in CKDu-related groundwater and non-CKDu-related groundwater are also significantly different14,61. Hence, the application of CRTA method can also be implemented to these inorganic sensitive indicators. In this study, it was found that the DPC and DPN through the RT of Ca2+ and Si recognized by CRTA can arrive at 82.4% and 64.2%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 12, Supplementary Table 5), although the detection probability by the RT of hardness and F− is not good. The plot of DPC versus the assumed threshold of F− undulated, which was attributed to high F− concentrations in several non-CKDu groundwaters (Supplementary Fig. 8). Thus, the curve of DPN versus the assumed threshold of F− is more reliable for identifying water sources than the curve of DPC versus the assumed threshold of F− using CRTA. Furthermore, FDOM indicators in combination with inorganic indicators could jointly recognize safe water sources by CRTA, which improves the reliability of recognizing results. In the future, investigations with more groundwater samples from larger areas with diverse geological and hydrological settings are recommended.

Methods

Study area

According to the annual precipitation, Sri Lanka can be divided into arid-semiarid and humid regions8. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, the study area (07°25.911’ - 07°40.116’N, 80°58.483’ - 81°04.888’E and 06°17.560’ - 06°24.158’N, 80°54.769’ - 80°59.995’E) is located in Girandurukotte (CKDu-endemic area), Dehiattakandiya (CKDu-endemic area), and Sewanagala (non-CKDu area) in semiarid zone, where the terrain is flat, evaporation is strong, and water resources are scarce, with an average annual rainfall of around 1000 mm and an annual temperature between 29 °C and 33 °C. The southwest monsoon (SW) rainy season is from May to October, and the northeast (NE) monsoon rainy season is from November to February. The Mahaweli River, the longest river in Sri Lanka, is located to the west of the study area. Geologically, rocks in this area are basically Precambrian granite and gneiss, which are enriched in mica, hornblende, apatite, and other fluorinated minerals. Although these rocks are low in porosity, they have developed faults and joints, which host groundwater resources. Local residents mainly use groundwater as the drinking water. Most people obtain groundwater in dug wells from unconsolidated fluvial sediments or shallow weathered bedrock aquifers8. Few residents use tube wells to obtain fissure groundwater from deep bedrock aquifers. Surface hydrological networks are controlled by man-made reservoir (tank) cascade systems mainly used for irrigation.

Sample collection and storage

Based on the information provided by local hospital, our team collected groundwater from the wells (CKDu groundwater) used by representative patients suffering from CKDu. In addition, we collected the other set of groundwater from the wells (non-CKDu groundwater) used by families without patients. A total of 83 water samples were taken, including CKDu groundwater (n = 43), non-CKDu groundwater (n = 32), and surface water samples (n = 8) collected from tanks (Supplementary Fig. 1). Samples were filtered with 0.7 μm quartz filter and acidified to pH < 2 with premium grade pure hydrochloric acid for spectral measurement. For DOC analysis, samples were filtered with 0.45 μm filter membrane and acidified to pH <2 with premium-grade pure phosphoric acid. More details of sample collection are provided in Supplementary Method.

Sample analysis

The fluorescent properties of DOM were tested by fluorescence spectrometer (Fluomax-4, HORIBA JboinYvon, Japan). The operation conditions were as follows: the light source was 150 W xenon lamp; excitation (Ex) wavelengths were set from 250 to 400 nm at 4 nm intervals; emission (Em) wavelengths were set between 300 and 550 nm at 2 nm intervals; the width of the slit was 3 nm and the integration time of the scanning signal was 0.1 s. The ultraviolet-visible absorbance was measured by a spectrophotometer (UV1900, Shimadzu, Japan) at 200–600 nm. DOC is determined by TOC analyzer (Aurora 1030w, OI, USA) with the analytical precision of ±2.0%, and the detection limit is 0.01 mg L−1. Analyzes of anions and cations are provided in Supplementary Method.

Spectral indices and PARAFAC

The spectral indices were calculated (Supplementary Method), including the humification index (HIX), the biological index (BIX), the fluorescence index (FI), the concentration of DOM with an unsaturated structure (a254), the aromaticity index (SUVA254), and the spectral slope (S275−295). Both the inner filter effect and background fluorescence signal of ultrapure water were corrected and Rayleigh scattering and Raman scattering were removed before PARAFAC using the efc toolbox (http://www.nomresearch.cn/efc/indexEN.html) developed by MATLAB graphical user interface20, the FDOM correct toolbox64, and the N-way toolbox (https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/1088-the-n-way-toolbox)65. The model finally passed the core consistency test and split-half verification66. The PARAFAC components were identified with those of the previous studies with the similarity exceeding 0.95. The relative abundance of PARAFAC components (C1%, C2%, C3%, and C4%) were quantified by dividing the maximum peak intensity (Fmax) of each component by the sum of Fmax of all components.

CKDu recognizing threshold assessment (CRTA)

The parameters of both DOM properties (such as C4%, C1%, and HIX) and inorganic chemicals (such as Ca2+ and F−) were considered as indicators for the assessment, during which the detection probability of CKDu groundwater (DPC) and the detection probability of non-CKDu groundwater (DPN) were defined and calculated. For each indicator, an initial threshold (normally the minimum of observed value) was set, above which the samples were assigned as the high value group and below which the samples were assigned as the low-value group. For most indicators (C1%, C2%, C3%, HIX, SUVA254, a254, DOC, the score of PC1, and inorganic indicators), DPC was calculated in the high value group, and DPN was calculated in the low-value group according to Eq. (1) and Eq. (2), respectively. For other indicators (C4%, S275-295, BIX, and FI), DPC was calculated in the low value group, and DPN was calculated in the high value group with Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively.

With the increase in the assumed threshold of each indicator from the minimum to the maximum (usually 100 steps; the set arithmetic sequence), corresponding DPC and DPN were calculated, and the plot of assumed threshold of the indicator versus DPC or DPN was drawn as shown in Fig. 6. The detection probability of intersection between two curves was defined as the applicability of the indicator in recognizing CKDu groundwater, and the assumed threshold value of intersection between two curves was defined as recognizing threshold (RT). The higher detection probability at RT gives the better recognizing applicability. Among all groundwater samples, 72% (n = 54) were used to calculate DPN and DPC and fitted by empirical Boltzmann equation, and the remaining (n = 21) were used to verify the fitting curves by paired t test and root mean square error (RMSE). If the p value of paired t test is greater than 0.05, it is assumed that the predicted result is close to the measured result. The lower the value of RMSE, the closer the predicted result is to the measured result.

The horizontal dashed line shows the detection probability (y) of intersection between two curves, which was defined as the applicability of DOM index in recognizing CKDu groundwater, and the vertical dashed line shows the threshold value (x) of intersection between two curves, which was defined as recognizing threshold.

Statistical analysis and data fittings

Independent-sample t-test, one-sample t-test, paired t-test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), principal component analysis (PCA), and Spearman correlation were performed through IBM SPSS Statistics 22. The t-test and ANOVA with the significance of p < 0.05 was used to analyze the differences and the variations between groups. The indicators used for PCA included DOC, FI, BIX, HIX, a254, SUVA254, S275-295, and the relative abundance of PARAFAC components (C1%, C2%, C3%, and C4%). Data fittings were achieved by Origin 2021 using the least square method. The calculation methods of ROC curve and P-R curve were described in Supplementary Method.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used to develop individual figures is available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Levine, K. E. et al. Quest to identify geochemical risk factors associated with chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu) in an endemic region of Sri Lanka—a multimedia laboratory analysis of biological, food, and environmental samples. Environ. Monit. Assess. 188, 548 (2016).

Gansevoort, R. T. et al. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet 382, 339–352 (2013).

Kulathunga, M. R. D. L., Ayanka, W. M. A., Naidu, R. & Wijeratne, A. W. Chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology in Sri Lanka and the exposure to environmental chemicals: a review of literature. Environ. Geochem. Health 41, 2329–2338 (2019).

Rajapakse, S., Shivanthan, M. C. & Selvarajah, M. Chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 22, 259–264 (2016).

Hettithanthri, O. et al. Risk factors for endemic chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in Sri Lanka: Retrospect of water security in the dry zone. Sci. Total Environ. 795, 148839 (2021).

Edirisinghe, E. et al. Geochemical and isotopic evidences from groundwater and surface water for understanding of natural contamination in chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu) endemic zones in Sri Lanka. Isot. Environ. Health Stud. 54, 244–261 (2018).

McDonough, L. K., Meredith, K. T., Nikagolla, C. & Banati, R. B. The influence of water–rock interactions on household well water in an area of high prevalence chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology (CKDu). npj Clean. Water 4, 1–9 (2021).

Balasooriya, S. et al. Possible links between groundwater geochemistry and chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu): an investigation from the Ginnoruwa region in Sri Lanka. Expo. Health 12, 823–834 (2020).

Dissanayake, C. B. & Chandrajith, R. Groundwater fluoride as a geochemical marker in the etiology of chronic kidney disease of unknown origin in Sri Lanka. Ceylon J. Sci. 46, 3–12 (2017).

Chandrajith, R. et al. Dose-dependent Na and Ca in fluoride-rich drinking water—another major cause of chronic renal failure in tropical arid regions. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 671–675 (2011).

Wickramarathna, S., Balasooriya, S., Diyabalanage, S. & Chandrajith, R. Tracing environmental aetiological factors of chronic kidney diseases in the dry zone of Sri Lanka—a hydrogeochemical and isotope approach. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 44, 298–306 (2017).

Wasana, H. M. et al. Drinking water quality and chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu): synergic effects of fluoride, cadmium and hardness of water. Environ. Geochem. Health 38, 157–168 (2016).

Tao, P. et al. Spatiotemporal variations in chromophoric dissolved organic matter (CDOM) in a mixed land-use river: Implications for surface water restoration. J. Environ. Manag. 277, 111498 (2021).

Lal, K. et al. Assessment of groundwater quality of CKDu affected Uddanam region in Srikakulam district and across Andhra Pradesh, India. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 11, 100432 (2020).

Makehelwala, M., Wei, Y., Weragoda, S. K. & Weerasooriya, R. Ca2+ and SO42- interactions with dissolved organic matter: Implications of groundwater quality for CKDu incidence in Sri Lanka. J. Environ. Sci. 88, 326–337 (2020).

Ojeda, A. S., Widener, J., Aston, C. E. & Philp, R. P. ESRD and ESRD-DM associated with lignite-containing aquifers in the U.S. Gulf Coast region of Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 221, 958–966 (2018).

Bunnell, J. E. et al. Evaluating nephrotoxicity of high-molecular-weight organic compounds in drinking water from lignite aquifers. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 70, 2089–2091 (2007).

Zheng, L. et al. Critical challenges and solutions on ground drinking water in chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu) affected regions in Sri Lanka. Chin. J. Environ. Eng. 14, 2100–2111 (2020).

Makehelwala, M. et al. Characterization of dissolved organic carbon in shallow groundwater of chronic kidney disease affected regions in Sri Lanka. Sci. Total Environ. 660, 865–875 (2019).

Zheng, Y. et al. Refractory humic-like substances: tracking environmental impacts of anthropogenic groundwater recharge. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 15778–15788 (2020).

Wells, M. J. M. et al. Fluorescence and Quenching Assessment (EEM-PARAFAC) of de Facto Potable Reuse in the Neuse River, North Carolina, United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 13592–13602 (2017).

He, W., Jung, H., Lee, J. H. & Hur, J. Differences in spectroscopic characteristics between dissolved and particulate organic matters in sediments: Insight into distribution behavior of sediment organic matter. Sci. Total Environ. 547, 1–8 (2016).

Lambert, T. et al. Effects of human land use on the terrestrial and aquatic sources of fluvial organic matter in a temperate river basin (The Meuse River, Belgium). Biogeochemistry 136, 191–211 (2017).

McDonough, L. K. et al. Changes in groundwater dissolved organic matter character in a coastal sand aquifer due to rainfall recharge. Water Res. 169, 115201 (2020).

Cooray, T. et al. Assessment of groundwater quality in CKDu affected areas of Sri Lanka: implications for drinking water treatment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 1698 (2019).

Diyabalanage, S. et al. Has irrigated water from Mahaweli River contributed to the kidney disease of uncertain etiology in the dry zone of Sri Lanka? Environ. Geochem. Health 38, 679–690 (2016).

Zhang, Z. et al. Mechanisms of groundwater arsenic variations induced by extraction in the western Hetao Basin, Inner Mongolia, China. J. Hydrol. 583, 124599 (2020).

Hu, Y. et al. Irrigation alters source-composition characteristics of groundwater dissolved organic matter in a large arid river basin, Northwestern China. Sci. Total Environ. 767, 144372 (2021).

Du, Y. et al. Enrichment of geogenic ammonium in quaternary Alluvial-Lacustrine aquifer systems: evidence from carbon isotopes and DOM characteristics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 6104–6114 (2020).

Chen, M., Price, R. M., Yamashita, Y. & Jaffé, R. Comparative study of dissolved organic matter from groundwater and surface water in the Florida coastal Everglades using multi-dimensional spectrofluorometry combined with multivariate statistics. Appl. Geochem. 25, 872–880 (2010).

Shen, Y., Chapelle, F. H., Strom, E. W. & Benner, R. Origins and bioavailability of dissolved organic matter in groundwater. Biogeochemistry 122, 61–78 (2015).

Luzius, C. et al. Drivers of dissolved organic matter in the vent and major conduits of the world’s largest freshwater spring. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 123, 2775–2790 (2018).

Coble, P. G. Characterization of marine and terrestrial DOM in seawater using excitation emission matrix spectroscopy. Mar. Chem. 51, 325–346 (1996).

Coble, P. G. Marine optical biogeochemistry: the chemistry of ocean color. Chem. Rev. 107, 402–418 (2007).

Chen, H., Zheng, B., Song, Y. & Qin, Y. Correlation between molecular absorption spectral slope ratios and fluorescence humification indices in characterizing CDOM. Aquat. Sci. 73, 103–112 (2011).

Wang, Y. et al. Effects of different dissolved organic matter on microbial communities and arsenic mobilization in aquifers. J. Hazard. Mater. 411, 125146 (2021).

Song, N., Bai, L., Xu, H. & Jiang, H. L. The composition difference of macrophyte litter-derived dissolved organic matter by photodegradation and biodegradation: Role of reactive oxygen species on refractory component. Chemosphere 242, 125155 (2020).

Spencer, R. G. M. et al. Seasonal and spatial variability in dissolved organic matter quantity and composition from the Yukon River basin, Alaska. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 22, 4002 (2008).

Hodgkins, S. B. et al. Elemental composition and optical properties reveal changes in dissolved organic matter along a permafrost thaw chronosequence in a subarctic peatland. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 187, 123–140 (2016).

Huguet, A. et al. Properties of fluorescent dissolved organic matter in the Gironde Estuary. Org. Geochem. 40, 706–719 (2009).

Ziegelgruber, K. L., Zeng, T., Arnold, W. A. & Chin, Y. P. Sources and composition of sediment pore-water dissolved organic matter in prairie pothole lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58, 1136–1146 (2013).

Dalmagro, H. J. et al. Spatial patterns of DOC concentration and DOM optical properties in a Brazilian tropical river-wetland system. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 122, 1883–1902 (2017).

Qi, L. M. et al. Photoreactivities of two distinct dissolved organic matter pools in groundwater of a subarctic island. Mar. Chem. 202, 97–120 (2018).

Guo, H. M. et al. Controls of organic matter bioreactivity on arsenic mobility in shallow aquifers of the Hetao Basin, P.R. China. J. Hydrol. 571, 448–459 (2019).

Kostyla, C., Bain, R., Cronk, R. & Bartram, J. Seasonal variation of fecal contamination in drinking water sources in developing countries: a systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 514, 333–343 (2015).

Qiao, W. et al. Molecular evidence of arsenic mobility linked to biodegradable organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 7280–7290 (2020).

Jin, J. & Zimmerman, A. R. Abiotic interactions of natural dissolved organic matter and carbonate aquifer rock. Appl. Geochem. 25, 472–484 (2010).

Begum, M. S. et al. Synergistic effects of urban tributary mixing on dissolved organic matter biodegradation in an impounded river system. Sci. Total Environ. 676, 105–119 (2019).

Guo, W. et al. Assessing the dynamics of chromophoric dissolved organic matter in a subtropical estuary using parallel factor analysis. Mar. Chem. 124, 125–133 (2011).

Hong, H. et al. Characterization of dissolved organic matter under contrasting hydrologic regimes in a subtropical watershed using PARAFAC model. Biogeochemistry 109, 163–174 (2012).

Kothawala, D. N., Wachenfeldt, E. V., Koehler, B. & Tranvik, L. J. Selective loss and preservation of lake water dissolved organic matter fluorescence during long-term dark incubations. Sci. Total Environ. 433, 238–246 (2012).

Lu, Y. H. et al. Photochemical and microbial alteration of dissolved organic matter in temperate headwater streams associated with different land use. J. Geophys. Res.: Biogeosci. 118, 566–580 (2013).

Stedmon, C. A. et al. Characteristics of dissolved organic matter in Baltic coastal sea ice: allochthonous or autochthonous origins? Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 7273–7279 (2007).

Walker, S. A. et al. The use of PARAFAC modeling to trace terrestrial dissolved organic matter and fingerprint water masses in coastal Canadian Arctic surface waters. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 114, 1470–1478 (2009).

Yang, L. Y. et al. Absorption and fluorescence of dissolved organic matter in submarine hydrothermal vents off NE Taiwan. Mar. Chem. 128, 64–71 (2012).

Lv, J. et al. Molecular-scale investigation with ESI-FT-ICR-MS on fractionation of dissolved organic matter induced by adsorption on iron oxyhydroxides. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 2328–2336 (2016).

Stedmon, C. A. & Markager, S. Resolving the variability in dissolved organic matter fluorescence in a temperate estuary and its catchment using PARAFAC analysis. Limnol. Oceanogr. 50, 686–697 (2005).

Gordon, T. et al. The effect of pH on spore germination, growth, and infection of strawberry roots by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. fragariae, cause of Fusarium wilt of strawberry. Plant Dis. 103, 697–704 (2018).

Teutscherov, N. et al. Comparison of lime- and biochar-mediated pH changes in nitrification and ammonia oxidizers in degraded acid soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 53, 811–827 (2017).

Stedmon, C. A. et al. A potential approach for monitoring drinking water quality from groundwater systems using organic matter fluorescence as an early warning for contamination events. Water Res. 45, 6030–6038 (2011).

Chandrajith, R. et al. Chronic kidney diseases of uncertain etiology (CKDue) in Sri Lanka: geographic distribution and environmental implications. Environ. Geochem. Health 33, 267–278 (2011).

Guo, H. M., Zhang, Y., Xing, L. N. & Jia, Y. F. Spatial variation in arsenic and fluoride concentrations of shallow groundwater from the town of Shahai in the Hetao basin, Inner Mongolia. Appl. Geochem. 27, 2187–2196 (2012).

Wu, T. & Liu, H. Estimating the area under a receiver operating characteristic curve for repeated measures design. J. Stat. Softw. 8, 1548–7660 (2003).

Murphy, K. R. et al. Measurement of dissolved organic matter fluorescence in aquatic environments: an interlaboratory comparison. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 9405–9412 (2010).

Bro, R. PARAFAC. Tutorial and applications. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 38, 149–171 (1997).

Stedmon, C. A. & Bro, R. Characterizing dissolved organic matter fluorescence with parallel factor analysis: a tutorial. Limnol. Oceanogr.: Methods 6, 572–579 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant Nos. 41861144027 and 41825017), 111 project (No. B20010). Sampling in Sri Lanka was supported by National Science Foundation grant No. ICRP/NSF-NSFC/2019/BS/01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z.: Data Curation, Laboratory testing, Writing- Original Draft. W.H.: Software, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. H.G.: Funding acquisition, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. Q.S.: Laboratory testing. Y.Z.: Laboratory testing. M.V.: Samples collection, Funding acquisition, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. J.H.: Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41545_2022_151_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

supporting information for recognizing the groundwater related to chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology by humic-like organic matter

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, X., He, W., Guo, H. et al. Recognizing the groundwater related to chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology by humic-like organic matter. npj Clean Water 5, 8 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-022-00151-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-022-00151-8

This article is cited by

-

Attention improvement for data-driven analyzing fluorescence excitation-emission matrix spectra via interpretable attention mechanism

npj Clean Water (2024)

-

Spatial patterns and environmental functions of dissolved organic matter in grassland soils of China

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Unraveling the enigma: chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology and its causative factors with a specific focus on dissolved organic compounds in groundwater—reviews and future prospects

Environmental Geochemistry and Health (2024)

-

Molecular Linkage of Dissolved Organic Matter in Groundwater with Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease with Unknown Etiology

Exposure and Health (2023)

-

Food-mediated exposure of Hofmeister ions in Oryza sativa (Rice) from selected CKDu endemic regions in Sri Lanka

Environmental Geochemistry and Health (2023)