Abstract

Rivers are well known as one of the most threatened aquatic environments, whose structure and water quality can be deeply impacted by intensive anthropogenic activities. Despite the fact that anthropogenic influences on river ecosystems could indeed be deduced from the composition and chemistry of fluvial dissolved organic matter (DOM), sources of anthropogenic loading to DOM are still poorly explored. Here, by uniting fluorescence excitation-emission matrices (EEM) and principal component absolute coefficient, four sources of DOM from seventeen rivers in major drainage basins of China could be identified, i.e., originating from municipal sewage, domestic wastewater, livestock wastewater, and natural origins, and thus being defined as MS-DOM, DW-DOM, LW-DOM, NO-DOM, respectively. Based on the random forest model, special nodes in EEM could be traced from four sources, respectively. According to parallel factor analysis, DOM mainly contained protein-like, microbial humic-like, and fulvic-like fluorescence substances, among which protein-like was dominant in MS-DOM and DW-DOM, microbial humic-like in LW-DOM, and fulvic-like in NO-DOM. Based on key peaks and essential nodes in EEM, the identifying source indices were first proposed, which could be introduced to simply distinguish the different anthropogenic-derived sources of fluvial DOM. It was associated with intensity ratios of the key peaks and the essential nodes of EEM spectra from four sources, i.e., municipal sewage (MS-SI: Ex/Em = 280/(335, 410) nm), domestic wastewater (DW-SI: Ex/Em = 280/(340, 410) nm), livestock wastewater (LW-SI: Ex/Em = 235/(345, 380) nm), and natural origins (NO-SI: Ex/Em = 260/(380, 430) nm). By statistical analysis, the high identifying source indices of municipal sewage (>0.5) and natural origins (>0.4) values could be related to MS-DOM and NO-DOM, respectively. The identifying source indices of domestic wastewater with 0.1–0.3 might be linked to DW-DOM and the identifying source indices of livestock wastewater with 0.3–0.4 to LW-DOM. Compared with conventional optical indices, the novel identifying source indices showed remarkable discrimination for the sources of fluvial DOM with different forms of anthropogenic disturbances. Hence the innovative approach could be relatively convenient and accurate to evaluate water quality or pollution risk in river ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rivers are known as prominent transporters of organic and inorganic matter from terrestrial to aquatic systems and can serve as a key linkage among the land, ocean, and atmosphere1,2,3. It offers imperative ecosystem services relying on both the amount and quality of terrestrial organic matter loading, which can detect responses of ecological environment to external disturbance via indicating local basin variations4,5. Notably, intensive anthropogenic activities, as the primary form for human impacting river basins, would induce modifications of regional land use, correspondingly which may influence structure and function of river and the fate of fluvial organic matter6,7. Therefore, the identification of organic matter sources in rivers is an urgent need for further insight into its chemical composition and environmental behavior, which would be conducive to monitoring and evaluation of the aquatic environment.

Dissolved organic matter (DOM), as a heterogeneous mixture of diverse compounds, is the most active portion of fluvial organic matter and an essential constituent of global biogeochemical cycles8,9,10. The chemical composition and structure properties of DOM exhibit a vital role on organic matter storages, nutrient cycles, microbial metabolisms, and fate of environmental contaminants11,12. DOM in aquatic system is derived from well known two sources: autochthonous and allochthonous. The latter might be primarily impacted by anthropogenic activities, especially land use within river drainage area, which can dedicate to the obvious discrepancy in chemical composition and structural properties of DOM13,14. For instance, the structural complexity of DOM in streams and rivers decreases with a rise in the proportion of continuous croplands to wetlands, while the quantity of microbially derived DOM rises with the increase of agricultural land use15. Moreover, urbanized rivers regularly exhibit a larger amount of DOM, higher chromophoric DOM absorption, stronger DOM fluorescence intensity, and a higher ratio of protein-like substances during summer1,6. Research into the dynamic processes of agricultural development and urbanization suggests that land-use changes due to human activity are closely linked to variations in fluvial DOM fractions6,14. Nevertheless, the intricacy of DOM fractions might obstruct efficiencies for identifying DOM sources in rivers, which is crucial to employ effective methods to trace the structural composition of DOM fractions.

To address this issue, numerous methods, such as conventional spectroscopies, mass spectrometry, and isotope characteristics, have been employed to elucidate chemical composition and trace sources of DOM in aquatic environment16,17. Furthermore, fluorescence excitation-emission matrices (EEM), possessing high sensitivity, rapid, inexpensive, easy, and minimal sample preparation, are broadly regarded as an efficient tool for early noticing a water contamination incident and identifying pollution source18,19. It has been reported that four spectroscopic indices deduced from EEM can be used to discriminate the primary source of DOM, i.e., fluorescence index (FI)20, biological index (BIX)21, a ratio of two recognized fluorescing substances (β/α)22, and humification index (HIX)23.

As reported previously, the complexity of DOM in the structure and composition could be primarily ascribed to disparate relative contributions of the diverse DOM sources, together with ensuing biogeochemical changes24. In this study, we would posit that novel identifying source indices could be deduced based on EEM to accurately identify different sources of fluvial DOM. To prove these hypotheses, our probe into the properties of fluvial DOM occurs in a relatively large-scale pattern by EEM. More than 300 water samples have been collected from seventeen rivers, almost associated with the seven major river drainage basins across China. Each type of sample from endmember regions was collected based on field research and data collection.

Thereby, developing an intelligent system is imperative for the issue11. Machine learning models can access and interpret massive, intricate, and multidimensional data to develop a predictable model, serving as a powerful tool for processing correlations among learning features and labels25,26. Additionally, the model could provide potential associations among learnable features, which might be conducive to a better understanding of the results of our hypotheses27,28. Thus, there is a desperate need to further uncover information of fluvial DOM based on a combined approach of EEM and machine learning model.

Therefore, the intentions of our study are as follows: (1) to identify sources of DOM from rivers using EEM combined with principal component absolute coefficient and trace special nodes of a given source using random forest model, (2) to characterize fluorescence components using parallel factor analysis (PARAFAC), (3) and to develop a novel approach of identification source defined as the identifying source indices.

Methods

Study area and sampling

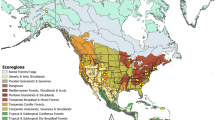

The rivers in this study distribute over a very extensive range of geographic latitude from 21°48’ N to 46°18′ N (Fig. 1), whose basin extend across five climatic zones, i.e., tropical monsoon, subtropical monsoon, warm temperate monsoon, mid-temperate monsoon, and temperate continental climates. Three hundred and three water samples were collected between 2018 and 2022, and three duplicates for each sample were undertaken considering the effect of environmental heterogeneity. All samples were passed through 0.45 μm acetate fiber filters, stored in sterile plastic bottles, and transported to the laboratory within the incubator immediately. All these filtrations and laboratory measurements were conducted within 24 h after sampling. The concentrations of chemical oxygen demand (CODCr), ammonia-nitrogen (NH3–N), and total phosphorus (TP) for all the samples were detected in this study (Supplementary Figs. 1–3).

17 rivers in major drainage basins of China were investigated in this study, whose land uses have been exhibited around the location map. The above maps were generated by ourselves using the ArcGIS version 10.7 software. The raster file of land uses was freely downloaded from a link http://www.globallandcover.com/.

The samples were obtained from the effluents of municipal sewage treatment plants with anaerobic-anoxic-oxic reactors as the core units, which entered the Huanhe River29. Hence, DOM from the effluents could be deeply impacted by the municipal sewage, which was defined as the municipal sources of DOM (MS-DOM). The samples collected from the Baitapuhe River across the rural and town regions, whose DOM could be derived from domestic wastewater are marked as DW-DOM30,31. The samples collected from Bayinhe River, a continental river flowing across Hunshandak Sandland, where a large number of cattle and sheep had been grazed, whose DOM should originate from livestock and poultry are marked as LW-DOM32,33. The samples gained from Longtaohe River across the Nature Reserve with less anthropogenic activities, whose DOM should be mainly derived from natural processes are marked as NO-DOM34,35.

Fluorescence spectrum acquisition

To obtain the structural composition properties of fluvial DOM, EEM scanning spectra of all the samples were recorded using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (F-7000, Hitachi, Japan). The excitation (Ex) and emission (Em) wavelengths were set to 200–450 nm and 260–550 nm with the scanning speed of 2400 nm min−1 respectively, all of whose scanning intervals were 5 nm. The slit width of Ex was fixed at 5 nm, so was Em. The inner filter effect was corrected via deducting the Milli-Q water spectra from all EEM data36. Principal component absolute coefficient was applied for the folded EEM data to discern key fluorescence regions, whose parsing process has been described in detail by Al Riza et al. 37.

PARAFAC was implemented to extract individual components from the EEM spectra using the DOMfluor toolbox in MATLAB R2017b (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). In this study, multi-component model was validated by split-half analysis and residual analysis, and the relative abundance of fluorescent components was evaluated by the maximum fluorescence intensity (Fmax)38. Besides, the parameters including FI, BIX, β/α, and HIX were employed to indicate DOM sources, whose solving methods had been precisely defined in the published literatures15,21.

Random forest model

Random forest, an integration algorithm for classification and regression, is an ensemble of optical decision trees, where unrelated bootstrap samples and a random choice of sample point with replacement, are operated in the construction of a given tree27. The basic elements of each tree contain information, entropy, and information divergence, which should be perceived important links for the data processing classification and anomaly detection25. The test result can be relative with internal nodes, the branches, and leaf nodes on the decision trees. The internal nodes address the test result of a certain attribute, the branches indicate the output of the test result, and the leaf nodes represent the predicted result. Its modeling process can be associated with four steps: data preparation, feature selection, random sampling, and decision tree generation.

The random forest model was applied to compute a measure of feature importance, which was built on multiple decision trees constructed by bootstrap aggregation in a randomly selected EEM dataset from a given type of source. Especially, as for the EEM dataset, fluorescence intensities in spectra were normalized to their maximal value. In the feature selection process using the model, each feature would participate in splitting decision tree nodes, whose contributions to the node splits for all decision trees were assessed by the Gini index26,27. Afterward, the importance ranking of each feature was determined by accumulating the contributions for each feature in the node splits of all decision trees, and top priority was recognized as the essential nodes of fluvial DOM from assigned sources. The parameter settings of the trained random forest model were shown in Supplementary Table 1. Moreover, the accuracy, recall, precision, and F1 score for each class were calculated to evaluate the performance of the random forest model (Supplementary Table 2). The model could be implemented in the Python programming language (version 3.8.5) in this study (https://gitee.com/dp-liu/rivers.git).

Statistical approach and model

Regression analysis was carried out in origin 2023b software to reveal the structural and composition differences of DOM from diverse sources. Spearman’s rank correlation was conducted in Python programming language (version 3.8.5) to explore the influence of sources on the humification degree of fluvial DOM. Frequency distribution was carried out in origin 2023b software to further refine the accuracy of the value ranges for source identification parameters developing in this study.

Results and discussion

Characterizing fluorescence spectroscopy of fluvial DOM

Principal component absolute coefficient was employed for the unfolding and concatenating data of all EEM to trace the eigen fluorescence peaks of DOM, and to identify differences among the sampling sites. Six principal components (PCs), eigenvalues greater than 1.000, were extracted, which accounted for 98.033% of the data variance. The absolute values of PC1-6 scores were refolded and added together (Supplementary Fig. 4), in which three discrete peaks existed: the peaks at the Ex/Em wavelength of 225/340 nm and 280/360 nm could be ultraviolet tryptophan-like fluorescence (UV-TRLF) and visible tryptophan-like fluorescence (Vis-TRLF) substances, respectively39, and the peak at the Ex/Em wavelength of 240/410 nm could be fulvic-like fluorescence (FLF) substance40. Interestingly, all sampling sites approximately exhibited an arc-shaped curve in the PC1-2 loadings plot with 91.591% of the total variances, which ran across the first, second and fourth quadrants (Fig. 2a). Notably, the sites at Huanhe River associated with MS-DOM were projected into the second quadrant, the sites at Baitapuhe River concerned with DW-DOM were projected into the region between the positive half-axis of PC2 and the line y = x, the sites at Bayinhe River referred to LW-DOM were projected into the region between the line y = x and the positive of half-axis of PC1, and the sites at Longtaohe River related with NO-DOM were projected into the fourth quadrant (Fig. 2b). Hence, all samples might be clustered into four groups: group I (PC1 < 0, PC2 > 0) explicitly with MS-DOM, group II (PC1 < PC2, PC1 > 0) with DW-DOM, group III (PC1 > PC2, PC2 > 0) with LW-DOM, and group IV (PC1 > 0, PC2 < 0) with NO-DOM.

a, b EEM loadings on PC1-2 associated with rivers, and all sampling sites were represented by circles of one color for a given river. c EEM loadings on PC1-2 associated with municipal sewage origin, 85.71% of the sites from municipal sewage origin were projected into the second quadrant. d EEM loadings on PC1-2 associated with domestic wastewater origin, 95.24% of the sites from domestic wastewater origin were projected into the region between the positive half-axis of PC2 and the line y = x. e EEM loadings on PC1-2 associated with livestock wastewater origin, 90.00% of the sites from livestock wastewater origin were projected into the region between the line y = x and the positive of half-axis of PC1. f EEM loadings on PC1-2 associated with natural sources, 85.14% of the sites from natural sources were projected into the fourth quadrant. No. 1 = Longtaohe River (LTR); No. 2 = Baitapuhe River (BTR); No. 3 = Dahanhe River (DHR); No. 4 = Shahe River (SHR); No. 5 = Xiongyuehe River (XYR); No. 6 = Bayinhe River (BYR); No. 7 = Qinghe River (QHR); No. 8 = Chaobaihe River (CBR); No. 9 = Huangji River (HJR); No. 10 = Dianhe River (DHR); No. 11 = Huanhe River (HHR); No. 12 = Linjiang River (LJR); No. 13 = Taigeyunhe River (TGR); No. 14 = Huaxihe River (HXR); No. 15 = Beima River (BMR); No. 16 = Jiti River (JTR); No. 17 = Baisha River (BSR).

The average concentration (61.03 ± 37.76 mg L−1) of CODCr was the highest at the sampling sites of group I, following group II (43.60 ± 21.48 mg L−1), group IV (41.93 ± 13.63 mg L−1) and group III (39.26 ± 16.90 mg L−1) (Supplementary Fig. 5). The order of the NH3–N means was group I (3.13 ± 3.32 mg L−1) > group II (1.24 ± 1.72 mg L−1) > group III (0.71 ± 1.25 mg L−1) > group IV (0.51 ± 0.99 mg L−1), so was the TP means. These indicated that MS-DOM was strongly influenced by anthropogenic activities, whereas the weak influence on NO-DOM. Obviously, the anthropogenic impacts on DW-DOM and LW-DOM were found between MS-DOM and NO-DOM. Expectedly, the region related to the sites of MS-DOM showed high proportions of urban land and ecological land based on the land-use types for 17 river basins (Supplementary Figs. 6–7), while the region regarded as DW-DOM had high proportions of township land and urban land. Moreover, the region associated with LW-DOM exhibited roughly high proportions of farmland, whereas the region relevant to NO-DOM represented high proportions of ecological land and farmland. This suggested that NO-DOM might be partially derived from the non-point sources16.

Principal component absolute coefficient was applied to further trace the key fluorescence peaks of DOM from a given source. The peaks associated with UV-TRLF and Vis-TRLF of MS-DOM appeared in the PC coefficients (1-3) (Supplementary Fig. 8a and Fig. 3a), so were DW-DOM (Supplementary Fig. 8b and Fig. 3b). However, compared with the peak of Vis-TRLF in the former, the latter had a red-shift of 5 nm along the Em wavelength. The peak at the longer Em wavelength could be associated with a larger quantity of conjugated aromatic p-electron systems with electron-withdrawn groups (such as carbonyl-containing substituents and carboxyl constituents)41,42,43. It could result in the fluorescence shift to lower energy levels or longer wavelengths. A much red-shift peak relative to UV-TRLF of LW-DOM exhibited in the PC coefficients (1-4) (Supplementary Fig. 8c and Fig. 3c), which suggested that UV-TRLF of LW-DOM should contain more carbonyl/carboxyl groups than those of MS-DOM and DW-DOM44,45. A prominent peak associated with UV-FLF of NO-DOM occurred in the PC coefficients (1-2) plot (Supplementary Fig. 8d and Fig. 3d)46, while the peak of TRLF disappeared nearly. This proposed that NO-DOM should represent a higher humification level than those of MS-DOM, DW-DOM, and LW-DOM47,48.

To deeply discriminate the fluorescent properties of DOM in a given source from the other three sources, the random forest model was constructed with the standardized EEM data, which were randomly divided into the training set (70%) and the test set (30%) to train the model and test model implementation. The essential nodes were produced on the key fluorescence peaks of DOM from a specific source (Fig. 4), where the locations of the nodes could be not only demonstrated but its frequencies be marked plainly.

With regard to MS-DOM, the nodes passed across the UV-TRLF peak along the Ex-wavelength, and a relatively high frequency of the node existed on the peak slope or in the peak valley (Fig. 4a). Nevertheless, the nodes appeared on the slope and valley of Vis-TRLF peak on the side with a long Ex-wavelength. For DW-DOM, the UV-TRLF peak on the side with a short Ex-wavelength was covered with the nodes, whose high frequencies occurred on the peak ridge and peak valley (Fig. 4b). Surprisingly, only a node with an extremely low frequency was on the slope of the Vis-TRLF peak. This indicated that the significant difference of the fluorescence spectra between MS-DOM and DW-DOM might be attributed to the Vis-TRLF, indirectly proving that a red-shift of the Em wavelength with 5 nm occurred on the Vis-TRLF peak of DW-DOM, compared with MS-DOM.

As to LW-DOM, dozens of the nodes were mostly concentrated on the slope of the red-shift UV-TRLF peak on the side with the short Ex-wavelength, and only two nodes were on the other side of the peak slope (Fig. 4c). Moreover, some nodes with unusually low frequencies were scattered on the other spectrum region. As for NO-DOM, more than twenty nodes roughly existed on the peak ridge of UV-FLF, which should be the fluorescence regions of UV-TRLF and humic-like (HLF) (Fig. 4d). This illustrated that the UV-TRLF from the plant residues could be degraded into FLF, which simultaneously could be decomposed into HLF. Furthermore, this indirectly proved that the fresh and biodegradable substances were relatively absent in NO-DOM.

Exploring variations of PARAFAC components

For investigating the properties of common DOM fractions, PARAFAC modeling was applied for the EEM data of DOM from the four sources to extract fluorescence components. Four independent components were identified by residual analysis and split-half analysis (Fig. 5). The PARAFAC components were assigned regarding the similarity score of >95% achieved by utilizing the OpenFluor database, i.e., the combination of tyrosine-like fluorescence (TYLF) and TRLF49,50, TRLF, microbial humic-like fluorescence (MHLF) and FLF51,52,53 (Table 1).

The Fmax sum of four components in MS-DOM was the largest, followed by LW-DOM, DW-DOM, and NO-DOM (Fig. 6a), indicating that the decreasing order of the fluorescence substance content was MS-DOM > LW-DOM > DW-DOM > NO-DOM. The total Fmax of TYLF and TRLF in MS-DOM were much more than the total Fmax of MHLF and FLF, so was DW-DOM (Fig. 6b). However, the former in LW-DOM or NO-DOM was much less than the latter. These elaborated that protein-like substances might be dominant in MS-DOM and DW-DOM, while humus-like substances might be the representative component in LW-DOM and NO-DOM54,55.

a total Fmax of four components. Red dots were the total Fmax for each sample from municipal sewage origin, blue dots from domestic wastewater origin, green dots from livestock wastewater origin, and purple dots from natural origin. b Fmax of each component in a given source, and the distribution characteristics for the mixtures of TYLF and TRLF, TRLF, MHLF, and FLF in each type of DOM were represented by red, blue, green, and purple boxplots, respectively.

Inter-variations of DOM fractions from a specific source could be revealed by relationships between PARAFAC components. In a given source, a significant positive relationship occurred between FLF and mixtures of TYLF and TRLF, so was between MHLF and FLF (Supplementary Fig. 9). The former indicated the combination of TYLF and TRLF had the same origin with FLF, which could be attributed to terrestrial loading in the rivers12,56. The latter suggested that DOM should be degraded by microbials partially into FLF. A significant positive relationship between TRLF and mixtures of TYLF and TRLF existed in MS-DOM, instead of DW-DOM, LW-DOM, and NO-DOM, which implied that TYLF and TRLF could have a common origin of the loading of municipal sewage57,58. Only just in LW-DOM, MHLF had significantly positive correlations with TRLF and mixtures of TYLF and TRLF, which proposed that TYLF and TRLF should be mainly degraded by microbials.

Considering that each type of source exhibited significant regional characteristics, the fluorescent components were isolated from MS-DOM (a-e), DW-DOM (f-j), LW-DOM (k-o) and NO-DOM (p-t), respectively (Fig. 7). According to previous literature2,39,54,58, all the components were classified into nine kinds: a combination of TYLF and TRLF (C1), a mixture of protein-like fluorescence substance related to TYLF, TRLF and phenolic moieties (C2), wastewater-derived organic matter (C3), microbial secretions (C4), intermediate humic-like and amino acid-like (C5), terrestrial humic with highest concentration in forest stream and wetlands (C6), MHLF (C7), FLF (C8) and HLF (C9). Moreover, C1 and C8 were both recognized in four types of DOM. C2 only occurred in DW-DOM, C3 in MS-DOM, C5 in LW-DOM, and C9 in NO-DOM.

In the MS-DOM, the total Fmax of C4 was highest, followed by C1, C3, and C8 (Supplementary Fig. 10). Furthermore, the specific (C3) and highest component (C4) resembled key peaks and the essential nodes of EEM spectra from municipal sewage origin. It demonstrated that fluorescence generated by wastewater-derived organic matter and microbial secretions was essential to identify MS-DOM. Similar to MS-DOM, the specific (C2) and highest component (C1) in the DW-DOM were consistent with key peaks and the essential nodes from domestic wastewater origin too, indicating that C1 and C2 were the primary representative components of DW-DOM. Likewise, C5 and C7 were the mainly representative components in LW-DOM, so were C7 and C9 in NO-DOM.

Development of a novel method for source identification

Four common spectroscopic indices (i.e., FI, β/α, BIX, and HIX) were applied to provide information regarding the primary sources of fluvial DOM. Most of FI values varied from 1.4 to 2.1 in MS-DOM, 1.5 to 2.0 in DW-DOM, 1.5 to 2.1 in LW-DOM, and 1.4 to 1.9 in NO-DOM (Fig. 8a–c). FI with less than 1.4 could be referred to terrestrial sources of DOM, FI with more than 1.9 to microbial, and FI with 1.4–1.9 to mixed sources20. Therefore, DOM in this study could be derived from the mixed sources. β/α values of NO-DOM were substantially lower than those of MS-DOM, DW-DOM, and LW-DOM (Fig. 8d–f), suggesting a smaller contribution of microbial-derived sources occurred in NO-DOM15. Compared with the other types of DOM (BIX: 0.85–1.15) (Fig. 8g–i), NO-DOM with lower BIX (0.60–0.80) values presented significantly allochthonous origins21. HIX values ranged from 0.7 to 1.7 in MS-DOM, 1.3 to 2.9 in DW-DOM, 2.5 to 5.5 in LW-DOM, and 5.5 to 8.5 in NO-DOM (Fig. 8j–l). This manifested that MS-DOM and DW-DOM were primarily associated with aquatic bacterial origin, LW-DOM with a weak humification degree and substantial recent autochthonous contribution, and NO-DOM with a strong humification degree and extensive terrigenous origin23. Noticeably, HIX could approximately discriminate between MS-DOM, DW-DOM, LW-DOM, and NO-DOM in the complex river basin.

a–c MS-DOM, d–f DW-DOM, g–i LW-DOM, and j–l NO-DOM. For each subfigure, the location of a given dot corresponded to the values of its two spectroscopic indices. The solid line was associated with the linear regression line and the shaded area with the 95% confidence interval. Significant relationships were revealed by the two-sided statistical tests via P < 0.05 and P < 0.01.

To further explore the effects of a specific source on the humification degree of DOM, a three-dimensional relationship could be determined between the EEM data of each sample and its HIX. HIX presented negative correlations with the intensities of the TYLF and TRLF regions in MS-DOM, while positive correlations with the intensities of the FLF region (Fig. 9a). The trend of correlations of HIX with EEM data in DW-DOM and LW-DOM were roughly similar to those in MS-DOM (Fig. 9b, c). These indirectly meant that TYLF and TRLF of DOM could mostly originate from municipal sewage, domestic wastewater, and livestock manure, which could be degraded sectionally into FLF19,59. Notably, significant positive correlations could be observed for HIX with the fluorescence intensities of MHLF and FLF in NO-DOM, besides a negative relationship between HIX and TRLF (Fig. 9d). This suggested that the addition of DOM from natural plant material could be decomposed by microbials and raise its humification degree. It was in accordance with previous reports that planting hydrophytes in aquatic environments could increase the amount of humus, mainly due to their growth and metabolism60.

a MS-DOM, b DW-DOM, c LW-DOM, and d NO-DOM. The positive correlations in subfigures (a–d) indicated that the humification degree of DOM in fluvial waters exhibited a rise with the input of fluorophores at this location, while the negative correlations indicated the opposite results. Based on Spearman’s rank correlation, the three-dimensional relationship was implemented in the Python programming language (version 3.8.5) in this study.

Considering the impact of anthropogenic activities on river ecosystems, source identification of DOM might be an urgent need for the assessment of water quality and pollution risk. Based on the key peaks and the essential nodes of EEM spectra from the four types of DOM sources, several identifying source indices could be developed in this study. As for MS-DOM and DW-DOM, two almost identical key peaks occurred on UV-TRLF and Vis-TRLF of EEM spectra respectively, where the essential nodes were remarkably different, especially the Vis-TRLF. Hence, the summit intensity of the Vis-TRLF, and the foot intensity along the peak ridge were selected to measure the identifying source indices (SI) for the identification of MS-DOM (MS-SI) and DW-DOM (DW-SI), whose formulae were shown in Table 2. The sole key peak was relative to the red-shift UV-TRLF in LW-DOM and to the UV-FLF in NO-DOM. Hence, coupled with the nodes of the key peak, the identifying source indices for recognizing LW-DOM and NO-DOM were defined as LW-SI and NO-SI, respectively (Table 2).

The identifying source index values could be measured by the formulae, which should be validated to trace the deviant samples. Gaussian distribution was applied for identifying source indices in a given source, not only to eliminate outliers in the exponential samples but also obtain index means and standard deviations. After the data validation of the identifying source indices, the normal distributions were obtained in each source (Fig. 10), by which extreme values of the identifying source indices in each source could be identified, respectively (Table 2). Therefore, the range of MS-SI was be determined, so were DW-SI, LW-SI, and NO-SI (Table 2). For instance, DOM with MS-SI of more than 0.5 should be mainly derived from municipal sewage, while DOM with MS-SI of less than or equal to 0.5 should be mainly originated from domestic wastewater and livestock wastewater.

a–b MS-SI, c–d DW-SI, e–f LW-SI, and g–h NO-SI. The red histograms in subfigures (a, c, e, and g) represented the distribution characteristics of MS-SI, DW-SI, LW-SI, and NO-SI values of MS-DOM. Likewise, blue, green, and purple histograms were connected with DW-DOM, LW-DOM, and NO-DOM, respectively. For each subfigure (b, d, f, and h), the range of a given identifying source index values from four types of DOM was shown. On the coordinate axis, near the center point was the minimum value of a given identifying source index, and the furthest away from the center point was the maximum value.

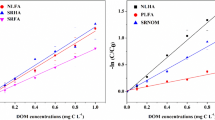

Since HIX of DOM in the rivers exhibited a larger dispersion than BIX, β/α, and FI, regressive analysis was be employed between the novel identifying source indices and HIX, by which MS-SI, DW-SI, LW-SI, and NO-SI could be tested feasibly. MS-SI had a very significant correlation with HIX (R2 = 0.55, p < 0.01), which was a convex composite function. The MS-SI range defined as the DOM source from the municipal sewage appeared in a monotonically decreasing interval (Fig. 11a). This elaborated that MS-SI could discriminate the municipal sewage from the other sources. The relationship between DW-SI and HIX exhibited a roughly same tendency as that between MS-SI and HIX (Fig. 11b). However, a relatively wide overlap along DW-SI occurred between DW-DOM and MS-DOM, so was between DW-DOM and LW-DOM. These indirectly proved that DOM from the rivers running across the urban-rural integration region could mainly be derived from mixed sources, i.e., municipal sewage, domestic wastewater, and livestock wastewater.

a MS-SI, b DW-SI, c LW-SI, and d NO-SI. The y-coordinate of a given red dot in subfigures (a–d) was related to the HIX values of MS-DOM, and its x-coordinate corresponded to the MS-SI (a), DW-SI (b), LW-SI (c), and NO-SI (d) values of MS-DOM, respectively. Likewise, blue squares were connected with DW-DOM, green triangles with LW-DOM, and purple inverted triangles with NO-DOM. The solid lines and gray area were associated with linear regression lines and the 95% confidence intervals. For a given subfigure, the two dotted lines were the boundaries of the predicted values from the regression analysis, and the shaded area was the range of two fluorescence indices used for source identification of fluvial DOM.

LW-SI showed a very close correlation with HIX, whose range known as DOM from the livestock wastewater lay in a monotonically increasing interval (Fig. 11c). Noticeably, a wide overlap along LW-SI existed between LW-DOM and DW-DOM too, which circumstantially suggested that DOM from the river flowing through the rural region might be originated from the domestic wastewater and livestock wastewater. The trend between NO-SI and HIX was approximately similar to that between LW-DOM and HIX (Fig. 11d). Interestingly, a broad overlap along NO-SI showed between NO-DOM and LW-DOM. This indirectly identified that DOM from the river with the weak influence of anthropogenic activities could be partially derived from the excrement of birds and fishes, whose compositions could be similar to livestock61. In addition, a portion of sites at Huaxihe River and Beimahe River, defined as the small and micro black-odor water bodies62, exhibited high NO-SI (>0.4) values, which attributed to the high humification level of DOM. This suggested that the SI should be more applicable to rivers with a relatively large basin (>6.67 km2)63. Particularly, considering that the protein-like peak will be quite high in rivers with bloom, the SI might not be utilized to identify sources in these rivers.

Implications for source identification through the SI method

Fluvial organic matter is crucial for determining the structure and function of aquatic ecosystems, which is also associated with the health of the surrounding ecological environment and residents14. DOM, as the most active portion of fluvial organic matter, plays an important role in many biogeochemical processes, including carbon and nutrient cycling, pollution transport, and metal binding, thereby functioning as a sensitive indicator of variations in local watershed64. As previously reported, anthropogenic activities could strongly impact water quality in rivers, and ascribe distinct DOM composition in fluvial waters nearby or flowing through highly populated areas65,66. Thus, it is imperative to develop an approach to identify the sources of fluvial DOM for further assess the influence of anthropogenic disturbances on rivers.

Fluorescence spectroscopy has been shown to be a reliable tool for capturing the composition and chemistry of fluvial DOM, which might be used to trace the sources of anthropogenic loading to DOM67,68. Given that conventional optical indices can only reveal allochthonous or autochthonous origins, a novel approach of source identification called the SI was proposed in this study. It was developed by the key peaks and the essential nodes of EEM spectra from the four types of DOM sources, which exhibited better discrimination of municipal sewage, domestic wastewater, livestock wastewater, and natural plant material origins compared with four common optical indices. Additionally, these findings were strongly supported by the correlations of FI with the other three optical indices (β/α, BIX, and HIX) (Fig. 8) and the regressive analysis between HIX and four novel identifying source indices (MS-SI, DW-SI, LW-SI, and NO-SI) (Fig. 11).

Particularly, we explored the degradation characteristics of DOM from diverse sources, and found that the DW-SI values of domestic wastewater for 1–5 h were within the range shown in Table 2 during the photo- and bio-degradation processes (Supplementary Fig. 11, Supplementary Tables 3 and 4)69, so were the LW-SI values of livestock wastewater for 0–7 day and the NO-SI values of natural origins for 0–1 day. Considering that the microcosm was under ideal degradation conditions with only one quantitative input of endmembers, the duration of the SI application might be longer in the actual environment due to the complicated environmental conditions and long-term input of endmembers. In contrast to four common optical indices, the SI showed significant discriminating for the sources of fluvial DOM with different forms of anthropogenic disturbances. These findings could provide an innovative approach for accurately identifying the sources of DOM in aquatic systems and determining those who caused pollution, which would contribute to targeting pollution treatment and the stabilization of fluvial ecosystems. In addition, the overshadowing signals in EEM data are going to be probed to accurately measure all components, and more samples would be input into the random forest model to more precisely trace fluorescent essential nodes. The molecular structure, function groups, and compound of fluvial DOM are being determined to verify the sources of fluvial DOM through high-resolution analysis techniques, followed by improving the accuracy of thresholds for the SI indices.

Data availability

The datasets obtained and analyzed in the research can be available from the first author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, L., Xu, Y. J. & Li, S. Riverine dissolved organic matter (DOM) as affected by urbanization gradient. Environ. Res. 212, 113457 (2022).

Parr, T. B. et al. Urbanization changes the composition and bioavailability of dissolved organic matter in headwater streams: increased urban DOM bioavailability. Limnol. Oceanogr. 60, 885–900 (2015).

Battin, T. J. et al. Biophysical controls on organic carbon fluxes in fluvial networks. Nat. Geosci. 1, 95–100 (2008).

Woolway, R. I. et al. Global lake responses to climate change. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 388–403 (2020).

Webster, J. R. & Meyer, J. L. Stream organic matter budgets: an introduction. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 16, 3–13 (1997).

Lyu, L. et al. Characterization of dissolved organic matter (DOM) in an urbanized watershed using spectroscopic analysis. Chemosphere 277, 130210 (2021).

Butman, D. E., Wilson, H. F., Barnes, R. T., Xenopoulos, M. A. & Raymond, P. A. Increased mobilization of aged carbon to rivers by human disturbance. Nat. Geosci. 8, 112–116 (2015).

Lynch, L. M. et al. River channel connectivity shifts metabolite composition and dissolved organic matter chemistry. Nat. Commun. 10, 459 (2019).

Roth, V.-N. et al. Persistence of dissolved organic matter explained by molecular changes during its passage through soil. Nat. Geosci. 12, 755–761 (2019).

Kamjunke, N. et al. Land-based salmon aquacultures change the quality and bacterial degradation of riverine dissolved organic matter. Sci. Rep. 7, 43739 (2017).

Zhao, C. et al. Exploring the complexities of dissolved organic matter photochemistry from the molecular level by using machine learning approaches. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 17889–17899 (2023).

Hu, A. et al. Ecological networks of dissolved organic matter and microorganisms under global change. Nat. Commun. 13, 3600 (2022).

Zhang, L., Xu, Y. J. & Li, S. Source and quality of dissolved organic matter in streams are reflective to land use/land cover, climate seasonality and pCO2. Environ. Res. 216, 114608 (2023).

Lambert, T. et al. Effects of human land use on the terrestrial and aquatic sources of fluvial organic matter in a temperate river basin (The Meuse River, Belgium). Biogeochemistry 136, 191–211 (2017).

Wilson, H. F. & Xenopoulos, M. A. Effects of agricultural land use on the composition of fluvial dissolved organic matter. Nat. Geosci. 2, 37–41 (2009).

Kim, M.-S. et al. Innovative approach to reveal source contribution of dissolved organic matter in a complex river watershed using end-member mixing analysis based on spectroscopic proxies and multi-isotopes. Water Res. 230, 119470 (2023).

Hu, J. et al. Photo-produced aromatic compounds stimulate microbial degradation of dissolved organic carbon in thermokarst lakes. Nat. Commun. 14, 3681 (2023).

Shen, J., Deng, S. & Wu, J. Identifying pollution sources in surface water using a fluorescence fingerprint technique in an analytical chemistry laboratory experiment for advanced undergraduates. J. Chem. Educ. 99, 932–940 (2022).

Li, L. et al. New advances in fluorescence excitation-emission matrix spectroscopy for the characterization of dissolved organic matter in drinking water treatment: a review. Chem. Eng. J. 381, 122676 (2020).

McKnight, D. M. et al. Spectrofluorometric characterization of dissolved organic matter for indication of precursor organic material and aromaticity. Limnol. Oceanogr. 46, 38–48 (2001).

Huguet, A. et al. Properties of fluorescent dissolved organic matter in the Gironde Estuary. Org. Geochem. 40, 706–719 (2009).

Parlanti, E., Wörz, K., Geoffroy, L. & Lamotte, M. Dissolved organic matter fluorescence spectroscopy as a tool to estimate biological activity in a coastal zone submitted to anthropogenic inputs. Org. Geochem. 31, 1765–1781 (2000).

Zsolnay, A., Baigar, E., Jimenez, M., Steinweg, B. & Saccomandi, F. Differentiating with fluorescence spectroscopy the sources of dissolved organic matter in soils subjected to drying. Chemosphere 38, 45–50 (1999).

Chen, M., Kim, S., Park, J.-E., Kim, H. S. & Hur, J. Effects of dissolved organic matter (DOM) sources and nature of solid extraction sorbent on recoverable DOM composition: implication into potential lability of different compound groups. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 408, 4809–4819 (2016).

Herzsprung, P. et al. Improved understanding of dissolved organic matter processing in freshwater using complementary experimental and machine learning approaches. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 13556–13565 (2020).

Xue, M. & Zhu, C. A study and application on machine learning of artificial intelligence. Int. Joint Conf. Artif. Intell. 272–274 (2009).

Lou, R., Lv, Z., Dang, S., Su, T. & Li, X. Application of machine learning in ocean data. Multimed. Syst. 29, 1815–1824 (2023).

Guo, S., Popp, J. & Bocklitz, T. Chemometric analysis in Raman spectroscopy from experimental design to machine learning–based modeling. Nat. Protoc. 16, 5426–5459 (2021).

Zhang, X., Nie, L., Gao, H., Yu, H. & Liu, D. Applying second derivative synchronous fluorescence spectroscopy combined with Gaussian band fitting to trace variations of DOM fractions along an urban river. Ecol. Indic. 146, 109872 (2023).

Yu, H. et al. Synchronous fluorescence spectroscopy combined with two-dimensional correlation and principle component analysis to characterize dissolved organic matter in an urban river. Environ. Monit. Assess. 188, 579 (2016).

Yu, H. et al. Comparison of PARAFAC components of fluorescent dissolved and particular organic matter from two urbanized rivers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23, 10644–10655 (2016).

Danyang, D. et al. Changes in and driving factors of the lake area of Huri Chagannao’er Lake in Inner Mongolia. J. Limnol. 81, 2079 (2022).

Han, L., Liu, D., Cheng, G., Zhang, G. & Wang, L. Spatial distribution and genesis of salt on the saline playa at Qehan Lake, Inner Mongolia, China. Catena 177, 22–30 (2019).

Zhang, M. et al. Flooding effects on population and growth characteristics of Bolboschoenus planiculmis in Momoge wetland, northeast China. Ecol. Indic. 137, 108730 (2022).

Henderson, R. K. et al. Fluorescence as a potential monitoring tool for recycled water systems: a review. Water Res. 43, 863–881 (2009).

Stedmon, C. A. & Bro, R. Characterizing dissolved organic matter fluorescence with parallel factor analysis: a tutorial. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 6, 572–579 (2008).

Al Riza, D. F., Kondo, N., Rotich, V. K., Perone, C. & Giametta, F. Cultivar and geographical origin authentication of Italian extra virgin olive oil using front-face fluorescence spectroscopy and chemometrics. Food Control 121, 107604 (2021).

Liang, E. et al. Roles of dissolved organic matter (DOM) in shaping the distribution pattern of heavy metal in the Yangtze River. J. Hazard. Mater. 460, 132410 (2023).

Liu, D., Gao, H., Yu, H. & Song, Y. Applying EEM-PARAFAC combined with moving-window 2DCOS and structural equation modeling to characterize binding properties of Cu (II) with DOM from different sources in an urbanized river. Water Res. 227, 119317 (2022).

Zhu, Y. et al. Insight into interactions of heavy metals with livestock manure compost-derived dissolved organic matter using EEM-PARAFAC and 2D-FTIR-COS analyses. J. Hazard. Mater. 420, 126532 (2021).

Chen, J., Gu, B., LeBoeuf, E. J., Pan, H. & Dai, S. Spectroscopic characterization of the structural and functional properties of natural organic matter fractions. Chemosphere 48, 59–68 (2002).

Pullin, M. J. & Cabaniss, S. E. Rank analysis of the pH-dependent synchronous fluorescence spectra of six standard humic substances. Environ. Sci. Technol. 29, 1460–1467 (1995).

Guilbault, G. G. & Norris, J. D. Practical fluorescence: theory, methods and techniques. Phys. Today 28, 49–50 (1975).

Song, F. et al. Depth-dependent variations of dissolved organic matter composition and humification in a plateau lake using fluorescence spectroscopy. Chemosphere 225, 507–516 (2019).

Senesi, N., Miano, T. M., Provenzano, M. R. & Brunetti, G. Characterization, differentiation, and classification of humic substances by fluorescence spectroscopy. Soil Sci. 152, 259–271 (1991).

Du, X., Xu, Z., Li, J. & Zheng, L. Characterization and removal of dissolved organic matter in a vertical flow constructed wetland. Ecol. Eng. 73, 610–615 (2014).

Thurman, E. M. Organic Geochemistry of Natural Waters (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Ma, H. Characterization of isolated fractions of dissolved organic matter from natural waters and a wastewater effluent. Water Res. 35, 985–996 (2001).

Chen, Y. et al. Photodegradation of pyrogenic dissolved organic matter increases bioavailability: novel insight into bioalteration, microbial community succession, and C and N dynamics. Chem. Geol. 605, 120964 (2022).

Ghidotti, M. et al. Source and biological response of biochar organic compounds released into water; relationships with bio-oil composition and carbonization degree. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 6580–6589 (2017).

Borisover, M., Laor, Y., Parparov, A., Bukhanovsky, N. & Lado, M. Spatial and seasonal patterns of fluorescent organic matter in Lake Kinneret (Sea of Galilee) and its catchment basin. Water Res. 43, 3104–3116 (2009).

Osburn, C. L. et al. Optical proxies for terrestrial dissolved organic matter in estuaries and coastal waters. Front. Mar. Sci. 2, 127 (2016).

Senesi, N. Molecular and quantitative aspects of the chemistry of fulvic acid and its interactions with metal ions and organic chemicals. Analytica Chim. Acta 232, 77–106 (1990).

Cabrera, J. M., García, P. E., Pedrozo, F. L. & Queimaliños, C. P. Dynamics of the dissolved organic matter in a stream-lake system within an extremely acid to neutral pH range: Agrio-Caviahue watershed. Spectrochim. Acta A 235, 118278 (2020).

Osburn, C. L., Handsel, L. T., Peierls, B. L. & Paerl, H. W. Predicting sources of dissolved organic nitrogen to an estuary from an agro-urban coastal watershed. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 8473–8484 (2016).

Murphy, K. R., Stedmon, C. A., Waite, T. D. & Ruiz, G. M. Distinguishing between terrestrial and autochthonous organic matter sources in marine environments using fluorescence spectroscopy. Mar. Chem. 108, 40–58 (2008).

Zhao, Y. et al. Evaluation of CDOM sources and their links with water quality in the lakes of Northeast China using fluorescence spectroscopy. J. Hydrol. 550, 80–91 (2017).

Stedmon, C. A. & Markager, S. Resolving the variability in dissolved organic matter fluorescence in a temperate estuary and its catchment using PARAFAC analysis. Limnol. Oceanogr. 50, 686–697 (2005).

Wang, L. et al. Microbial roles in dissolved organic matter transformation in full-scale wastewater treatment processes revealed by reactomics and comparative genomics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 11294–11307 (2021).

Pi, J., Zhu, G., Gong, T. & Lu, Y. Dissolved organic matter derived from aquatic plants in constructed wetlands: Characteristics and disinfection byproducts formation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 107991 (2022).

Hudson, N. et al. Can fluorescence spectrometry be used as a surrogate for the Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) test in water quality assessment? An example from South West England. Sci. Total Environ. 391, 149–158 (2008).

Lu, K. et al. Insight into variations of DOM fractions in different latitudinal rural black-odor waterbodies of eastern China using fluorescence spectroscopy coupled with structure equation model. Sci. Total Environ. 816, 151531 (2022).

Ministry of Water Resources - China. Code for Design of Levee Project (GB50286-2013) (China Planning Press, Beijing, 2013).

Zhang, H., Zheng, Y., Wang, X. C., Wang, Y. & Dzakpasu, M. Characterization and biogeochemical implications of dissolved organic matter in aquatic environments. J. Environ. Manag. 294, 113041 (2021).

Li, F. et al. Application of environmental DNA metabarcoding for predicting anthropogenic pollution in rivers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 11708–11719 (2018).

Williams, C. J. et al. Human activities cause distinct dissolved organic matter composition across freshwater ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 613–626 (2016).

Shang, Y. et al. Natural versus anthropogenic controls on the dissolved organic matter chemistry in lakes across China: insights from optical and molecular level analyses. Water Res. 221, 118779 (2022).

Wang, K. et al. Optical and molecular signatures of dissolved organic matter in Xiangxi Bay and mainstream of Three Gorges Reservoir, China: Spatial variations and environmental implications. Sci. Total Environ. 657, 1274–1284 (2019).

Hou, J., Wu, F., Xi, B. & Li, Z. Applying fluorescence spectroscopy and DNA pyrosequencing with 2D-COS and co-occurrence network to deconstruct dynamical DOM degradation of air-land-water sources in an urban river. Sci. Total Environ. 904, 166794 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFC3201502).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.L. and H.Y. collected and analyzed data apart from writing the paper. L.N. developed the random forest model in this study. B.X. and H.G. conceived the study and edited the paper. F.Y. aided in the modeling and edited the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, D., Nie, L., Xi, B. et al. A novel-approach for identifying sources of fluvial DOM using fluorescence spectroscopy and machine learning model. npj Clean Water 7, 79 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-024-00370-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-024-00370-1