Abstract

Here in this study, a novel ternary CuS/HKUST‒1/Ni(acac)2 nano photocatalyst (CSHK‒Ni) was developed through a facile modification of HKUST‒1 MOF with Ni(acac)2 metal complex and by immobilizing CuS into the metal-organic framework (MOF). The incorporation of CuS, a narrow bandgap semiconductor, is anticipated to allow easy excitation by visible-light and improve the photocatalytic potential of the formulated catalyst which is validated by the decrease in the bandgap energy from 3.10 eV of pristine MOF to 2.19 eV. Moreover, the anchoring of the metal complex improves the light harvesting behavior by increased conjugation. Photoluminescence studies provided evidence of the effective separation of the photoinduced charge-carriers, reducing the rate of recombination and enhancing the photocatalytic potential of the CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite. The engineered catalyst displayed remarkable efficiency in the degradation of nitroimidazole containing antibiotics, Tinidazole (TNZ) and Metronidazole (MTZ), via H2O2 assisted AOP achieving a maximum photocatalytic efficiency of 95.87 ± 1.64% and 97.95 ± 1.33% in just 30 min under irradiation of visible light at optimum reaction conditions. The possible degradation pathway was elucidated based on the identification of ROS and degradation intermediates via HR‒LCMS and quenching experiments. Meanwhile, the chemical oxygen demand (COD) and total organic carbon (TOC) removal were also examined, encompassing the discussing of various aspects including reaction conditions, influence of various oxidizing agents, competing species and dissolved organic substrates present in the wastewater, marking the novelty of the study. This research elucidated the role of the CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite as an interesting photocatalyst in the elimination of emerging nitroimidazole containing pharmaceutical pollutant under visible-light exposure, presenting an exciting novel avenue for a cleaner and greener environment in the days to come.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the main reasons for the deterioration of our environment is the rapid and increased industrialization brought about by the Industrial Revolution. Furthermore, the amount of untreated wastewater released into aquatic bodies has significantly expanded due to the manufacturing industries’ large-scale output, contributing to the global water and environmental pollution issue1. The scarcity of clean drinking water has now become a global issue. Most developing countries like India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal are adversely affected by water pollution2. Discharging water-soluble and non-biodegradable pollutants, such as textile dyes, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, heavy metals, personal care products, nitro compounds, and phenols, contaminates most freshwater bodies3.

Personal care products and pharmaceuticals (PPCP) have been classified as emerging pollutants because of their potentially harmful environmental impacts. Antibiotics represent a prominent category of pharmaceuticals frequently found in aqueous systems, originating from the discharge of hospital effluents and industries engaged in drug and pesticide manufacturing. Since antibiotics are highly persistent and resilient to biological breakdown, they are categorized as emerging contaminants. Antibiotic resistance in bacteria may result from a genetic mutation brought on by prolonged antibiotic treatment4. Studies have indicated that the continued presence of antibiotics in aquatic environments may negatively affect both human health and the ecosystem. Tinidazole (TNZ) and metronidazole (MTZ) are antibiotics belonging to the nitroimidazole class, are mainly used to treat parasite and bacterial infections, skin ailments and gum infections. Previous literatures have suggested that antibiotics, featuring a nitroimidazole framework, have the potential to induce gene mutations and may possess carcinogenic properties. Thirty percent of the medication is eliminated and enters the aquatic environment unaltered tending to accumulate with time5. Due to their widespread distribution in a range of aquatic settings, tinidazole and metronidazole were designated as drugs of significant environmental concern.

Conventional wastewater treatment approaches are ineffective for eliminating nitroimidazoles from wastewater effluent owing to their complex molecular structure and high solubility6. Photodegradation is widely used to remove harmful pollutants because of its primary process, affordable nature, and easy operating circumstances, which also prevent the risk of secondary pollution. Photocatalysis, which converts hazardous organic pollutants in wastewater into safe molecules solely using solar light, is a promising environmentally friendly solution to reduce environmental pollution. Advanced oxidation process (AOP) is a novel approach by which reactive oxygen species (ROS) like hydroxyl radicals (OH•), superoxide radicals (O2−•) and sulfate radicals (SO4−•) are generated by the decomposition of an oxidizing agent like hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), ozone (O3), persulfate (S2O82−), etc., by a heterogeneous catalyst under mild conditions and the ROS generated then attack the pollutant molecules and bring their degradation7.

Heterogenous AOP is a surface phenomenon occurring over the surface of a semiconductor photocatalyst and is a facile method for degrading organic pollutants in wastewater. Here, a photocatalyst is excited under light irradiation, generating electron-hole pairs that decompose the oxidizing agent, resulting in the formation of ROS. The separation of the electrons and holes is necessary to utilize them for generating ROS before their recombination. The synergistic attack of the ROS allows the degradation of the target pollutant into less harmful products like CO2 and H2O. Recently, a photo-Fenton like AOP has been gaining broad attention owing to its ease of operation, cost-effectiveness, and higher efficiency. Hydrogen peroxide is used as a green oxidizing agent in a photo-Fenton-like AOP for generating OH• and O2−• radicals to degrade target pollutants under light irradiation8.

Since nanomaterials possess a large surface area, are highly reactive, and have more exposed active sites than other materials, they are widely desired for photocatalysis9. Various nanoscale metal oxide-based photocatalysts have been extensively explored for the photodegradation of organic pollutants from aqueous streams owing to their low cost, high abundance, higher light absorption properties, and high stability. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) has remained a milestone in photocatalysis due to its excellent stability, resistance to photocorrosion, non-toxicity, and low cost10. Despite its significant advantages, some limitations, such as low specific surface area, a faster rate of charge recombination, and a higher bandgap of 3.2 eV, force researchers to develop new materials with multifunctional properties to cope with the limitations of TiO2. Additionally, the agglomeration of nanoparticles during synthesis limits their light absorption and decreases the photocatalytic activity. Copper sulfide (CuS) is a non-toxic, low-cost p-type semiconductor photocatalyst with a suitable bandgap of 1.8 eV and outstanding light-harvesting properties11,12. Interestingly, the photocatalytic properties of CuS can be tailored based on its morphology and synthesis techniques. Different morphologies of CuS, such as spheres13, hollow spheres13, nanotubes14, hexagonal sheets15, and flower-like16, have been previously reported in the literature. Recently, Abdullah et al.17 fabricated a ternary CuO/CuS/MnO2 nanocomposite to photodegrade methylene blue dye with 98% efficiency. Mertah et al.18 investigated the degradation of sulfamethoxazole using Cu-CuS@TiO2 nanocomposite. CuFeS2/CuS heterojunction showed enhanced photodegradation of organophosphate insecticides, as reported by Gholami et al.19. The literature suggests that the photocatalytic properties of CuS could be improved by forming its nanocomposites.

Various porous materials such as activated carbon, biochar, zeolites, and clays have been explored as support for nanomaterials to prevent their agglomeration. However, the shortcomings of irregular pore size, low surface area, and negligible light absorption still need to be resolved. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are a novel category of porous and crystalline supports that can be constructed in one, two, or three dimensions using organic linkers to connect a metal center with an organic ligand20. The ability of MOFs to easily adjust their pore size from meso to micro scale by modifying their organic ligand and inorganic metal ions is one of its most remarkable features21. Additionally, they have a large surface area, strong chemical reactivity, tunable pore diameter, and a variety of structural types that facilitates them to be used in a diverse range of applications22. MOF-based semiconductor nanocomposites exhibit novel and remarkable capabilities due to their synergistic effect. With copper as its inorganic metal center and benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxylate (H3BTC) as its organic ligand, HKUST-1 is one of the most commonly mentioned MOFs23. A vacancy in the framework structure is created by Cu ions coordinating with oxygen atoms from BTC moieties and H2O molecules24. This MOF has extensive uses in various industries, including hazardous gas purification, liquid phase separation, sensing, CO2 adsorption, environmental remediation, hydrogen storage, photocatalysis, drug delivery, etc25. A novel ternary nanocomposite of CuS supported over zeolite and ZIF-8 showed 87% removal of methylene blue from the aqueous phase26. Recently, CuS/HKUST-polydopamine nanocomposite showed enhanced photo-antimicrobial properties under visible light irradiation with an efficiency of up to 99%27. Despite all these developments, the creation of CuS heterojunctions with metal complexes was not given much attention. The synergistic benefits of heterojunctions of CuS and metal complexes include a conjugated structure for effective charge transfers, a decreased charge recombination rate at very low metal concentrations, and metal centers for redox reactions. Complexes of Ni (II) with acetylacetone are increasingly attracting interest in fields of material science due to their diverse utility as molecular separation, catalysis, solar energy storage, and light-emitting diode materials. The remarkable thermal stability and the chelating behavior of acetylacetone, allows it to be an excellent supporting moiety for harvesting of light, and then subsequently transfers energy to the metal ion, serving as a photosensitizer28. Ouedraogo et al.29 synthesized g-C3N4/copper octacarboxyphthalocyanine heterojunction, which showed 98% degradation of methylene blue under optimum conditions. Das et al.30 studied the photocatalytic hydrogen evolution and chromium reduction using Copper tetraphenylporphyrin tetrasulfonic acid decorated g-C3N4. Recently, g-C3N4/Mn(acac)3 nanocomposite showed 99.59% degradation of rhodamine B dye within 55 min of visible light irradiation.

Continuing this vein, we aim to present a novel ternary CuS/HKUST-1/Ni(acac)2 (CSHK‒Ni) nanocomposite by anchoring a transition metal Ni(II) Bis-acetylacetonate complex into CuS immobilized Metal-Organic Framework via a facile approach for the degradation of nitroimidazole antibiotics. There is no mention of such examples obtained by coupling HKUST‒1 MOF with Ni(acac)2 complex as a photocatalyst in previous literatures as per the best knowledge of the author, and this work is first of its kind. The designed photocatalyst was investigated for the elimination of two nitroimidazole framework containing pharmaceutical, tinidazole (TNZ) and metronidazole (MTZ), using H2O2-assisted AOP under visible light in a very short duration of 30 min. Also, theoretical and computational studies using Gaussian 16 suit program have been provided to validate the bandgap of the synthesized materials. The possible degradation pathway of the breakdown of TNZ and MTZ was elucidated based on the identification of degradation intermediates via HR‒LCMS. Quenching experiments using different scavenging agents and EPR studies were conducted for the assessment of the ROS responsible for the breakdown of the model contaminants. Meanwhile, COD and TOC removal were also examined, encompassing the discussing of various aspects including reaction conditions, influence of various oxidizing agents, competing species and dissolved organic substrates present in the wastewater, marking the novelty of the study. Furthermore, the performance of the fabricated CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite under practical water conditions and the removal of other toxic pharmaceutical contaminants was comprehensively analyzed. From the commercial perspective the designed catalyst displays significant potential for large-scale industrial applications owing to its cost-effectiveness compared to previously reported catalysts. Besides, several strategies have been outlined as future prospects to enhance the catalytic recycling of the synthesized CSHK–Ni nanocomposite via structural modifications focusing on improving the stability, durability, and reusability of the nanomaterial. This research elucidated the role of the CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite as an interesting photocatalyst in the elimination of emerging nitroimidazole containing pharmaceutical pollutant under visible light exposure for a cleaner and greener environment in the days to come.

Methods

Cupric nitrate trihydrate extrapure (Cu (NO3)2.3H2O), thioacetamide (CH3CSNH2), trimesic acid extrapure and nickel (II) nitrate hexahydrate (Ni (NO3)2.6H2O) were acquired from SRL chemicals, India. Solvents and reagents such as ethanol, NaOH, acetylacetone and chloroform were obtained from Sigma‒Aldrich. Further purification steps were avoided as the chemicals utilized were of analytical grade, and deionized water was consistently employed throughout the experiments.

The preparation of Ni(acac)2 complex is carried out by slowly adding 4.5 ml of acetylacetone (0.044 moles) into an aqueous solution of NaOH (1.6 g in 15 ml water, 0.04 moles) while stirring, maintaining the temperature below 40 °C. The reaction mixture should be stirred thoroughly to ensure that any white precipitate formed at this point is completely dissolved. The yellow‒colored solution prepared above is added dropwise with vigorous stirring over 15 min into a 25 ml aqueous solution of Ni (NO3)2.6H2O (5.81 g, 0.02 moles). The resulting bluish‒green precipitate is filtered, washed with distilled water, and subsequently dissolved in a hot solution mixture of 39 mL of 95% ethanol and 26 mL chloroform in a fume hood. Prolonged boiling should be avoided. Finally, the green solution is allowed to cool to ambient temperature, and then chilled in ice to obtain turquoise‒colored needles of pure Ni(acac)2. These crystals are then washed with cold ethanol, dried in air and stored for further use.

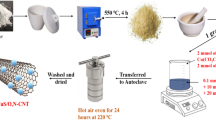

Typically, for the synthesis of CuS/HKUST‒1, 0.50 g of HKUST‒1 MOF support is dispersed in ethanol under ultrasonication for 20 min. Then, aqueous solution of 1.2 g of Cu (NO3)2.3H2O is added into the former mother solution, followed by the addition of 0.75 g of thioacetamide (CH3CSNH2) under stirring at room temperature. The resulting reaction mixture was then taken into a 100 ml stainless steel reactor with lined with Teflon and heated in an electric oven at 160 °C for 8 h. The obtained bluish-black precipitate of CuS/HKUST‒1 was subsequently collected via centrifugation, subjected to multiple times washing with distilled water and ethanol, and finally dried overnight at 80 °C.

The CuS/HK (0.20 g), so obtained, was dispersed in 95% ethanol and then slowly added in drops with constant stirring into another solution containing Ni(acac)2 dissolved in 39 mL of 95% ethanol and 26 mL chloroform. The resulting reaction mixture was then kept under sonication for 1 h and subsequently cooled in an ice bath, to form precipitates of CSHK‒Ni. The obtained greenish‒black CSHK‒Ni composite was subjected to filtration and multiple rounds of washing with 95% ethanol, and then finally dried in an electric oven maintained at 80 °C overnight. Figure 1 portrays the schematic illustration of the fabrication of the CSHK‒Ni composite.

Analytical experiments

The entire photodegradation tests were performed in glass beakers of 100 mL capacity, subjected to irradiation under a Philips LED bulb of 23 W with an illuminance of 11,790 lx and the measured intensity of radiation was found to be 51.25 W/m2 to assess the photodegradation efficacy of the CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite. The experimental arrangement was established inside a wooden compartment with the LED bulb positioned overhead and the glass beaker was placed at a distance of 10 cm from the LED source. Typically, the batch degradation experiments were performed with an optimized amount of the synthesized nanocomposite in 50 mL TNZ/MTZ solution of 20 mg/L initial concentration as the standard model contaminant, and then followed by the introduction of an optimized amount of H2O2. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was allowed to attain the adsorption-desorption equilibrium by stirring in the dark for 20 min, prior to 30 min irradiation of visible light for photodegradation to occur. The photodegradation of TNZ and MTZ was tracked by monitoring a decrease in the maximum absorbance at 277 nm and 321 nm, respectively by employing a UV‒vis spectrophotometer. Moreover, no significant decline in the intensity of absorption (<5%) was noted after allowing the contaminant solution to agitate in the absence of light with the photocatalyst (HKUST‒1, CuS/ HKUST‒1 and CSHK‒Ni) and H2O2 alone, eliminating the possibility of subsequent degradation by H2O2 alone. Additionally, no significant change in the intensity of absorption (<3%) was observed after the irradiation of the TNZ/MTZ solution with visible light in the absence of any oxidizing agent and the photocatalyst, indicating that the pollutant solution exhibited resistance to self-degradation under visible light. The percentage degradation efficiency of the photocatalytic process can be determined by the following reaction:

In this equation, Co denotes the initial concentration of the contaminant, while Ct signifies the contaminant concentration after specified time t, in mg/L.

Again, the degradation kinetics of the TNZ/MTZ solution was computed employing the pseudo-first order kinetics model, employing the equation outlined below:

Herein, k refers to the pseudo-first order rate constant of the degradation reaction. The graphs involving the error bars depict the degradation profile and the reaction kinetics plot with negligible standard deviations, suggesting reasonable reproducibility of the experiments for atleast three times under consistent reaction conditions.

While in most of the literatures, the photocatalytic degradation reactions were typically performed in pure water, however, the influence of practical water samples on the photodegradation of hazardous organic contaminants have not been extensively investigated. Hence, this study primarily revolves around the practical utility of the synthesized CSHK‒Ni photocatalyst in practical wastewater conditions by considering the consequence of various inorganic ions and dissolved organic compounds on the photodegradation mechanism. To access the performance of the photocatalyst in real‒water matrices, photodegradation experiments were conducted using mineral water purchased from a local grocery store, waters from Barak river, lake water collected from a lake in the NIT Silchar campus with a pH of 8.17, rain water and tap water from municipal water systems. The standard method for determining chemical oxygen demand (COD) was employed in which samples containing H2O2 were first subjected to an excess of 10% Na2SO3 to eliminate the influence of H2O2 in COD measurement31. This is followed by heating the solution under air to oxidize the unreacted excess Na2SO3. Furthermore, the mineralization of TNZ and MTZ was assessed via total organic carbon (TOC) analysis under optimized reaction conditions, as outlined in Eq. (3).

In this equation, TOCo represent the initial TOC concentration and TOCt denotes the final TOC concentration at reaction time t.

The structural stability of the engineered CSHK–Ni catalyst was established through a reusability assessment. After centrifugal recovery, the catalyst underwent multiple cycles of washing in ethanol and water. It was then oven–dried at 80 °C before being utilized for the subsequent catalytic cycle.

Material characterization

PXRD analysis of the as-synthesized samples were conducted on Phillips X’PERT Pro X-ray diffractometer using Cu-Kα at a measured wavelength of 1.5418 Å for the assessment of the crystallographic evidence. The microstructure and surface morphology, SAED patterns and the size of the particles of the prepared composite were studied using HR−TEM analyzed via a JEOL, model JEM 2100 F 200 kV instrument. FTIR spectra was obtained by Bruker Hyperion 3000 Spectrometer for the detection of functional groups. For the structural and compositional determination, SEM images and EDAX were analyzed using Gemini 500 FE−SEM instrument accelerated at a range of 0.2 to 30 kV. The determination of the elemental composition of CSHK–Ni nanocomposite was conducted via XPS utilizing a PHI 5000 versaprobe II FEI Inc. Varian Cary eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer was utilized for recording photoluminescence (PL) spectra. Cary 5000 UV–vis–NIR, Agilent Inc. spectrophotometer instrument was employed for UV-DRS analysis to estimate the band gap energy. Genesys 10S UV-vis spectrophotometer equipped with a 1 cm cuvette, covering wavelengths from 200–800 nm was utilized for measuring the absorbance of the liquid samples.

Results and discussion

XRD analysis was employed to investigate the variation in the crystal structure of the fabricated materials i.e., HKUST‒1, CuS, CuS/HK and CSHK‒Ni as displayed in Supplementary Fig. 1, Fig. 2a–c. The XRD spectrum of the pristine HKUST‒1 in Supplementary Fig. 1 showed distinct peaks at 7.08°, 9.51°, 11.91°, 13.39°, 16.24°, 17.36°, 19.26°, 20.46°, 22.95°, 25.27°, 29.35°, 35.79° and 39.14° are consistent to our previous reports and can be associated to the lattice planes (200), (220), (222), (400), (422), (511), (440), (600), (551), (731), (751), (773) and (882), respectively23,24. Moreover, as portrayed in Fig. 2b, the XRD spectrum of CuS/HK reveals some additional distinct characteristic peaks at 27.98°, 29.34°, 31.91°, 32.60°, 46.95°, 47.98°, 52.62° and 59.1°, which can be indexed to (101), (102), (103), (006), (107), (110), (108) and (116) crystal facets of CuS (JCPDS No. 06‒0464)27,32. This confirms the presence of the hexagonal phase of CuS in the synthesized CuS/HK composite. However, compared with the XRD spectrum of the pristine HKUST‒1, the spectrum of CuS/HK composite exhibited a slightly broader pattern, with the appearance of small peaks. This occurrence can be attributed to the in‒situ sulfuration process, wherein the synthesized CuS nanoparticles compressed the 3D structure of the MOF which contributed to the disorder and the observed small peaks in the XRD spectrum33. In Fig. 2c, the XRD patterns of the synthesized ternary CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite portray all the above-mentioned peaks of CuS and HKUST‒1, including some distinct peaks that perfectly agree with the previously reported literatures of Ni(acac)2 following the JCPDS No. 19‒1524. The peaks situated at 2θ values of 8.14°, 19.14°, 26.28°, 29.68°, 36.18°, 41.32°, 42.17° and 49.52° assigned to the lattice planes (100), (111), (300), (113), (114), (123), (204) and (106), respectively are of the monoclinic phase of Ni(acac)2. Hence, the presence of all the mentioned distinct peaks of CuS, HKUST‒1 and Ni(acac)2 in Fig. 2c, agreeing with their respective JCPDS No. signifies the successful fabrication of the designed ternary CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite.

The existence of surface functional groups and chemical bonds of the fabricated HKUST-1, Ni(acac)2 and CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite was analyzed by FT−IR as illustrated in Fig. 2d–f. Figure 2d portrays the FTIR spectrum of pristine HKUST-1 where the characteristic distinct peaks at 1625 cm−1, 1441 cm−1 and 1366 cm−1 were produced because of the stretching vibrations of C=O and C–O and bending vibrations of O–H of bidentate coordination mode of carboxylic acid moiety that coincide with the previous literatures23,24. Furthermore, the distinctive peak at 875 cm−1, especially reflects the tri-substitution of benzene, originating from the bending vibrations of C–H. Again, the distinctive peak for Cu−O stretching vibration positioned at 727 cm−1 signifies that copper has been successfully coordinated with the BTC linker. The Ni(acac)2 complex displayed prominent stretching vibrations at 1590 cm‒1 and 1477 cm‒1, attributed to the C=O moiety and the allylic fragment of acetylacetonate, respectively28 in Fig. 2e. Moreover, the peak at 1372 cm‒1, 1046 cm‒1 and 1005 cm‒1 can be ascribed to the stretching vibrations of C=C, C‒O and C–C, respectively. Vibration peaks at 603 cm‒1 and 650 cm‒1 confirms the existence of Ni–O bonds. Additionally, in Fig. 2f, the distinct peak observed at 476 cm‒1, responsible for the vibrational stretching of the Cu–S bond, validated the presence of CuS in the CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite27,34. Thus, it is evident from Fig. 2f that peaks ascribed to pristine HKUST-1, CuS and Ni(acac)2 can be clearly observed in the FT-IR spectrum of CSHK‒Ni composite, suggesting the successful synthesis of the nanocomposite.

The XPS analysis serves to examine the purity and the chemical states of the elements present in the synthesized sample. Figure 3 depicts the XPS spectrum of the synthesized CSHK‒Ni conducted within the binding energy ranging from 0‒1400 eV. The wide spectrum analysis revealed the presence of five elements including copper, sulfur, nickel, oxygen and carbon as portrayed in the survey spectrum (Fig. 3a). The Ni 2p deconvoluted spectra in Fig. 3b displays two characteristic Ni2+ peaks with a spin‒orbit separation of 18 eV. Two intense strong peaks at binding energy values of 854.41 eV and 872.31 eV, correspond to Ni 2p3/2 and Ni 2p1/2 states respectively which validates the +2 oxidation state of Ni in Ni(acac)2. Moreover, two satellite peaks were also observed of Ni 2p situated at B.E values of 860.02 eV and 878.06 eV35. The short scan HR‒XPS Cu 2p spectrum, depicted in Fig. 3c, exhibits two prominent peaks at 934.05 eV and 954.01 eV, characteristic of the Cu 2p3/2 and Cu 2p1/2 states of Cu 2p respectively. The binding energies of these peaks, with a spin–orbit separation of 19.9 eV, signifies the +2-oxidation state of Cu+2. Besides these, additional vibrational satellite peaks were observed at 939.90 eV and 944.61 eV which clearly identifies the Cu2+ state36,37. The high-resolution S 2p spectrum shown in Fig. 3d depicts two characteristic peaks situated at energies 163.90 eV and 161.60 eV, attributable to S 2p1/2 and S 2p3/2 spin‒orbit states of S 2p respectively. The appearance of these peaks indicates the presence of S2‒ state in transition metal sulfides, thus confirming the formation of CuS in the CSHK‒Ni composite38. The short scan deconvoluted spectrum of C 1 s offers insights into the type of carbon species present in the fabricated composite (Fig. 3e). The existence of the sp3 C‒C/C=C in the alkyl group of the acetylacetonate and the BTC linker of the MOF, was depicted by the peak at binding energy of 284.80 eV, whereas the peak at 286.76 eV can be attributable to the C‒O bond37. The high binding energy shoulder at 288.87 eV can be assigned to the C=O bond present in the organic linker molecules and is a characteristic of the acetylacetone ligand cycle in the synthesized composite35,39. The O 1 s spectrum can be deconvoluted as shown in Fig. 3f portraying different chemical environments of the O element. The peak at binding energies of 530.22 eV shows the existence of O‒Cu bond, while the presence of the carboxylate ‒C=O/‒OH bond can be associated to the peak position at 531.96 eV36,40. The existence of the Ni‒O bond gets overlapped with the O 1 s peak at 531.22 eV. These characteristic peaks are in good correlation with the previous studies.

The optical characteristics are crucial in assessing the photocatalytic performance of the synthesized composites. To evaluate the light-harvesting abilities of HKUST‒1, CuS, Ni(acac)2 and CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite, the UV‒DRS spectra of these samples were studied as depicted in Fig. 4a. Two broad peaks of absorption are noticed in the Cu-BTC UV–vis spectrum. The wide absorption peak observed around the wavelength 600–800 nm may be associated to Cu2+ d–d spin allowed transitions, whereas the peak observed at approximately 300 nm can be associated to π-π transitions of the linker molecules23. The spectrum of the as‒synthesized CuS exhibits a wide absorption in the visible region ranging from 270‒800 nm, which suggests a potentially higher utilization and conversion efficiency of visible light after its incorporation in the CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite32,41. On the other hand, Ni(acac)2 spectrum features two distinct peaks at 324 nm and 636 nm, corresponding to the 3T2g(D) → 3A2g(F) and 3T1g(F) → 3A2g(F) spin‒allowed transitions of Ni2+28. Additionally, the appearance of a shoulder at 307 nm signifies a strong MLCT interaction between the Ni d‒orbitals and the acetylacetonate ligand π‒orbitals42. The peak at 260 nm reflects the delocalized π‒π* transitions of the ligand. The absorption peaks in the designed CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite is observed to be red shifted, indicating a strong interaction between the individual components. Notably, the fabricated CSHK–Ni nanocomposite displayed a strong and broad UV and visible light response than pristine HKUST‒1 and Ni(acac)2, contributing to an improved light harvesting characteristics and enhanced photodegradation efficiency of the nanocomposite.

The bandgap of the synthesized samples was determined via the absorption edge using the Tauc’s plot, which involves the equation outlined below:

Here, in the above equation, the value of n depends on the type of optical transition involved in the semiconductor, and is usually considered as ½ for indirect and 2 for direct transition, α designates the co-efficient of absorption, h\({\rm{\nu }}\) signifies the incident light energy, A represents the energy–dependent constant, and Eg is the energy of the optical band gap. The band gap of the samples was estimated from the plot of (αh\({\rm{\nu }}\))2 vs Energy (h\({\rm{\nu }}\)) as displayed in Fig. 4b. It can be observed that pristine HKUST-1, CuS and Ni(acac)2 presents a direct band gap energy (Eg) of 3.10 eV, 1.86 eV and 3.61 eV, respectively42. The low bandgap energy of CuS is in accordance with its broad absorption peak as observed in Fig. 4a11,32,41. However, after the incorporation of CuS and Ni(acac)2 into the HKUST‒1 framework, the bandgap of the synthesized CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite was considerably reduced to 2.19 eV. This sudden decline in the bandgap energy, falling in the visible light region, is anticipated to improve the photocatalytic performance of the CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite compared to its individual counterparts. Meanwhile, the narrow bandgap allows easy excitation and higher utilization of visible light.

Furthermore, in addition to the effective separation of photoinduced charges, minimizing the probability of recombination of the e−‒ h+ pair is crucial for designing visible light active photocatalysts. The photoluminescence (PL) studies provide useful insights into the recombination and separation of charges in nanomaterials. Figure 4c depicts a comparative examination of the PL spectra of the designed CSHK‒Ni photocatalyst with that of pristine HKUST‒1, with an excitation wavelength of 300 nm. The prominent emission peak in the PL spectra of pristine HKUST‒1, at about 340 nm, is indicative of rapid recombination of photoinduced charge carriers43. However, the decline in the PL emission intensity at 340 nm in the designed CSHK‒Ni photocatalyst, suggests effective suppression of the charge recombination rate, leading to a reduction in the PL intensity44. Upon formation of the nanocomposite, the photoexcited electrons gets transferred facilitating effective delocalization of the charges over the surface of the photocatalyst, while diminishing the recombination rate and improving the photocatalytic performance6. This suggests the availability of more time for the photogenerated charges to generate increased ROS before undergoing recombination, promoting the overall photocatalytic performance of the designed catalyst.

The BET data offers detailed insights into the surface characteristics and structural porosity of the fabricated nanocomposite. A detailed analysis of the relationship between the relative pressure (P/P0) and adsorption volume, as depicted in Fig. 4d, allows us to identify the specific type of isotherm and hysteresis loop present. According to IUPAC recommendations, the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm constructed from the BET data exhibits a typical Type IV curve. This type of isotherm is characterized by an initial behavior similar to Type II isotherm, indicating monolayer-multilayer adsorption, followed by a significant increase in adsorption at higher relative pressures owing to capillary condensation in mesopores. The substantial increase in adsorption volume at high relative pressures aligns closely with the typical features of a Type IV isotherm, commonly associated with mesoporous materials.

Moreover, the findings demonstrate the presence of a hysteresis loop, a characteristic often observed in Type IV isotherms, suggesting mesoporosity of the photocatalyst45. The shape and presence of this hysteresis loop unveils valuable insights into the pore structure of the nanomaterial. The notable increase in adsorption volume at higher relative pressures, along with the clear distinction between the adsorption and desorption branches, suggests the presence of an H1 hysteresis loop. This pattern is indicative of homogeneous mesopores within the material. The specific surface area of the material was observed to be 44.94 m²/g and a micropore volume of 0.15 cm³/g, suggesting the presence of micropores with diameters smaller than 2 nm. The combination of a substantial micropore volume, and the presence of a Type IV isotherm with an H1 hysteresis loop suggests a complex pore structure within the material. This structure includes both micropores, which dominate the surface area, and mesopores responsible for capillary condensation and the observed hysteresis. Such a hierarchical pore arrangement, including micropores and mesopores, makes it well-suited for enhanced pollutant degradation. In summary, single-layer adsorption of gas followed by pore condensation in mesoporous materials results in a type IV isotherm, with H1 hysteresis loop indicating the mesoporous structure with cylindrical pore channels of the prepared material. The pore volume of 0.15 cm3/g provides active sites for pollutant interaction and improves the photocatalytic activity of the overall nanocomposite46,47. However, the overall photocatalytic efficiency of a material hinges not solely on its specific surface area, but also on several other critical factors. These include the rate of charge transfer minimizing electron-hole recombination, adequate porosity, and reduced band gap of the photocatalyst48.

FE-SEM analysis was employed to study the surface morphology of the synthesized CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite. As can be observed from Fig. 5a, b, that the octahedral HKUST‒1 framework exhibit a rough surface texture with structural distortion upon formation of the composite49. Upon closer inspection in the magnified SEM micrographs, it becomes apparent that the surface of the octahedral HKUST‒1 is adorned with numerous CuS nanoparticles, making the surface irregular and relatively rougher with misty edges27. The surface irregularity of the fabricated CSHK‒Ni composite is advantageous for enhancing the interaction between the contaminant molecules and the photocatalyst, thereby improving the photocatalytic efficiency of the prepared composite50. The EDS results revealed the presence of sulfur and nickel, besides the existence of copper, carbon and oxygen, indicating the successful synthesis of CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite (Supplementary Fig. 2). Moreover, elemental mapping demonstrated uniform dispersion of all the elements over the CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite (Fig. 5c–h)

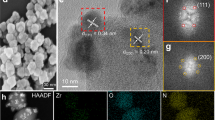

Additionally, the TEM and HR‒TEM micrographs were acquired to examine the morphological, structural, shape and size characteristics of the synthesized CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite as displayed in Fig. 6. The representative HR‒TEM image in Fig. 6b, c of the synthesized nanocomposites allows us to clearly distinguish the octahedral geometry of HKUST‒1 with distinct boundary. Meanwhile, careful examination of Fig. 6d reveals the existence of interplanar lattice spacing of 0.26 nm and 0.34 nm, associated to the (773) and (300) lattice planes of HKUST‒1 and Ni(acac)2 (JCPDS No. 19‒1524) respectively, confirming the existence of these components in the fabricated nanocomposite. The interplanar lattice spacing correlated well with the most intense peak observed in the XRD spectrum. Furthermore, the presence of CuS in the CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite can be confirmed from the lattice spacing of 0.18 nm, corresponding to the (110) plane of CuS (JCPDS No. 06‒0464). The SAED patterns were also analyzed, as shown in Fig. 6e, that confirms the polycrystalline nature of the synthesized CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite. The observed bright concentric rings indicated high crystallinity of the fabricated nanocomposite. Quantitative analysis of the TEM images involved fitting the particle size histogram with the Lorentzian function, revealing an average particle size of 14.97 nm of the synthesized CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite (Fig. 6f).

Computational Studies of the bandgap energies

Structures of Ni(II) Bis-acetylacetonate complex, HKUST-1 Metal-Organic framework and copper sulfide were fully optimized at M06-2X/def2-TZVP level51. Harmonic frequency calculations were also performed at the same level of theory to understand the nature of stationary point on the potential energy surface. All the structures were found to be at their local minima with all real values of the Hessian matrix. All these calculations were performed using Gaussian 16 suite of program52. Figure 7 shows the optimized geometries of the complexes.

The band gap or the HOMO-LUMO gaps of these complexes were also evaluated at the same level of theory. There is a very good agreement between the experimental optical band gap and the calculated values. The HOMO-LUMO gap for Ni(II) Bis-acetylacetonate, Copper BTC/HKUST-1 MOF and copper sulfide monolayer are 3.78, 3.21 and 1.92 eV respectively which are very close to that observed experimentally. Figure 8 shows the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the respective complexes as well as their orbital eigen values. The HOMO and LUMO of Ni(II) Bis-acetylacetonate represent the π and π* orbitals of acetylacetonate ligands respectively. The HOMO of Copper BTC/HKUST-1 MOF represents the d-orbital on one of the Cu metal while LUMO represents the π* orbitals of the aromatic phenyl ring. The HOMO of copper sulfide layer represents the lone pair at the S atom along with Cu–S bonding while LUMO represents Cu–S antibonding orbital.

Photocatalytic performance

To evaluate the photodegradation capabilities of the synthesized CuS, HKUST‒1, CuS/HK and CSHK‒Ni catalysts, the photodegradation of TNZ and MTZ was initially investigated as illustrated in Fig. 9a, c, conducted in 50 mL of the pollutant solution having initial concentration of 20 mg/L. A loading of 0.20 g/L of each prepared catalyst was utilized for each of the experiments under exposure to visible light irradiation for 30 min. The experimental data of the degradation process of the various synthesized catalysts in different systems is tabulated in Supplementary Table 1. Initially, there was only a negligible decline in the intensity of absorption of the model contaminants after 30 min of irradiation of visible light in the blank condition, indicating the high stability of the drug molecules which makes it resistant to self-degradation under irradiation of visible light6. Similarly, pure HKUST‒1 and CuS/HK exhibited limited photocatalytic activity towards TNZ and MTZ degradation. Pristine HKUST‒1 achieved only 6.52±1.23% degradation of TNZ and 5.99 ± 1.21% degradation of MTZ after 30 min of irradiation, likely due to the wider bandgap of HKUST‒1, which surpasses the theoretical minimum energy required for excitation by visible light (3 eV)53. Conversely, the binary CuS/HK catalyst resulted in attaining an efficacy of 31.80 ± 1.34% TNZ and 37.90 ± 1.46% MTZ degradation, attributed to its comparatively narrower bandgap than the pristine MOF, enhanced light absorption properties, and delayed delocalization of charges facilitated by CuS incorporation into the MOF (Fig. 9b, d). Notably, the photodegradation efficiency significantly increased to 50.67 ± 1.87%% for the TNZ + CSHK‒Ni+visible light system having a pseudo‒first order rate constant of 0.02771 min−1. Interestingly, upon addition of H2O2, the efficacy of the system to eliminate TNZ drastically increased to 84.76 ± 1.16% with a pseudo‒first order rate constant of 0.06965 min−1. Similarly, the maximum catalytic efficiency of the MTZ + CSHK‒Ni+H2O2+visible light system reached was 88.19 ± 1.22% and the rate constant was calculated to be 0.07836 min−1. This unusual behavior could be accredited to the increased number of ROS, such as •OH species, produced in the system which facilitates the degradation of the targeted TNZ molecules. Consequently, the synthesized ternary CSHK‒Ni emerged as a superior photocatalyst compared to pristine HKUST‒1 and CuS/HK under visible light exposure. The improved performance of the CSHK‒Ni photocatalyst can be stemmed from its enhanced delocalization of photogenerated charges and increased light harvesting properties, which contributed towards the generation of ROS, responsible for boosting TNZ/MTZ degradation. The combination of MOFs with chelating metal complexes provides significant advantages, such as the availability of metal centers for redox reactions, and a lower rate of recombination even at very low metal concentrations. Additionally, acetylacetone, with its two oxygen atoms possessing lone pairs of electrons, plays a crucial role in binding metal cations effectively. The conjugated structure of the chelating acetylacetone ligand facilitates the delocalization of photogenerated charges across the surface of the photocatalyst, promoting efficient charge transfer. This results in diminishing the recombination rates, promoting photocatalytic performance.

In heterogeneous AOP, molecular O2 serves as an electron scavenger, generating •O2‒ species. The deficiency of O2 resulting from sluggish O2 consumption or mass transfer can be compensated by typical inorganic oxidants, namely H2O2, BrO3−, IO4− and ClO3− in which they serve a dual function, acting both as electron scavengers and potent oxidants. The influence of the above‒mentioned inorganic oxidants on the TNZ and MTZ degradation by the photocatalyst CSHK‒Ni was investigated as shown in Supplementary Table 2. The study was performed under exposure to visible light for 30 min with a pollutant concentration of 20 mg/L, catalyst dosage of 0.20 g/L at neutral pH using various oxidizing agents. Visible light irradiation combined with these oxidizing agents accelerated the photodegradation of TNZ and MTZ as shown in Fig. 10a, c. After 30 min of exposure, degradation rates of 79.41 ± 1.23%, 84.76 ± 1.16, 86.34 ± 1.46% and 87.11 ± 1.22% were achieved for TNZ solution with ClO3−, H2O2, BrO3− and IO4−, respectively. On the other hand, 83.42 ± 1.86%, 88.19 ± 1.22, 89.01 ± 1.56% and 90.41 ± 1.46% were achieved for MTZ solution with ClO3−, H2O2, BrO3− and IO4−, respectively. Interestingly, the photocatalytic efficiency of the photocatalyst was found to be 50.67 ± 1.87% for TNZ and 52.78 ± 1.38% for MTZ, in the absence of any oxidizing agent. This can be explained by the fact that the efficacy of the entire catalytic system hinges on photons, which must possess sufficient energy for the excitation of the photocatalyst, to produce e− and h+. Nonetheless, without an oxidizing agent, the catalytic system lacks e− and h+ scavengers, leading to rapid recombination probability and ultimately yielding poor degradation efficiency. The below equations (Eqs. (5–12)) outline the degradation mechanism and emphasize the generation of photoinduced charge carriers, alongside the production of •OH and •O2− radicals responsible for the breakdown of the pollutant molecules.

The addition of H2O2 leads to the generation of increased •OH radicals under exposure to visible light, as explained above in Eqs. (13–15), which is the primary reason for the enhanced performance of the catalyst towards the degradation of the target contaminants. Moreover, the scavenging effect of the photogenerated e− and the h+, thereby generating •OH radicals and prolonging the recombination time is also responsible for the observed inference.

Again, the results from Fig. 10b, d demonstrate IO4− as the most effective oxidant towards the photodegradation of TNZ and MTZ which can be attributed to the formation of highly reactive IO3•, IO4• and OH• radicals in the reaction system as shown below54:

Additionally, BrO3− emerged as the second most effective oxidant by acting as scavengers of electrons, and producing BrO2• radical. Also the BrO3− ion reduces the recombination of photogenerated charge carriers by reacting with e−, thereby enhancing the degradation of TNZ and MTZ in the reaction system, as depicted by the below mentioned reactions55:

In addition, the TNZ degradation performance in the absence of the photocatalyst, was determined to be 8.23±1.19%, 10.63±1.47%, 16.11±1.44% and 25.91±1.86% for ClO3−, H2O2, BrO3− and IO4−, respectively. Notably, the negligible degradation efficiency in the visible+ClO3− system towards TNZ and MTZ might be because of its limited ability for UV light absorption. Conversely, the improved degradation performance noted in the presence of IO4− can be attributed to the generation of highly reactive free radicals, thereby facilitating the degradation of TNZ and MTZ. Although IO4− and BrO3− demonstrated superior degradation performance in contrast to H2O2, further photodegradation experiments were conducted in H2O2 as oxidant due to concerns related to environmental pollution and the high toxicity associated with other oxidants.

Hydrogen peroxide is well known for its oxidizing ability in a photo-Fenton-like AOP to increase the efficiency of a photocatalytic reaction. Thus, the influence of H2O2 on the photocatalytic degradation of TNZ and MTZ (20 mg/L) using 0.20 g/L of the prepared photocatalyst was investigated by varying its concentration from 0 mL to 0.5 mL (Fig. 11a, c). Initially, it was observed that the degradation of both TNZ and MTZ increases with increasing H2O2 concentration and then starts to decline at higher concentrations. The initial increase in the degradation performance can be associated to the increased concentration of OH• due to the decomposition of H2O2 on exposure to visible light, according to the Eqs. (13–15)6:

The OH• initiates an attack on the target pollutants and increases the degradation efficiency. A decrease in the photocatalytic efficiency at higher H2O2 dosage is due to the self‒quenching of •OH radicals by H2O2, generating less reactive hydroperoxyl radicals (HO2•), as shown by the following Eq. (21):

The kinetics of the photodegradation of TNZ and MTZ at varying H2O2 concentrations is displayed in Fig. 11b, d. Maximum degradation of 90.64 ± 1.86% of TNZ and 92.78 ± 2.16% of MTZ was observed at 0.2 mL and 0.3 mL H2O2 dosages, with a maximum pseudo-first-order rate constant of 0.07986 min−1 and 0.08906 min−1, respectively (Supplementary Table 3). Thus 0.2 mL and 0.3 mL of H2O2 concentration were fixed for other photodegradation tests of TNZ and MTZ. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that without H2O2 the photocatalyst could degrade 50.67 ± 1.87% of TNZ and 52.78 ± 1.38% MTZ, signifying the role of H2O2 in this photocatalytic reaction.

The pH of the solution substantially influences the surface charge of the fabricated CSHK‒Ni catalyst, that ultimately affects the efficiency of the photocatalyst. Hence, it is essential to determine the initial optimal pH at which the targeted contaminant attains maximum decomposition from the aqueous medium. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) method was employed to determine the pH of the Zero Point Charge (PZPC) with 0.1 M NaOH and HCl, using 0.01 M KNO3 solution as the electrolyte, and it was found to be 6.18 from Supplementary Fig. 3.

The consequence of pH on the degradation of the model pollutants TNZ and MTZ was studied by conducting batch experiments by the fabricated CSHK‒Ni photocatalyst in a 20 mg/L pollutant solution at pH ranging between 3–11. The entire reactions were performed at optimal conditions under 30 min exposure of visible light. As illustrated in Fig. 12a, c, the maximum degradation efficiency peaked at pH = 3 for both TNZ and MTZ reaching 93.02 ± 1.42% and 95.78 ± 1.86% with a rate constant of 0.09378 min−1 and 0.10681 min−1 respectively (Fig. 12b, d). With the gradual rise in the pH towards neutral conditions, a slight decline in the photocatalytic efficiency was observed which can be accounted to the decrease in the oxidation potential of •OH radicals that subsequently lowers the rate of degradation. However, a drastic decrease in the efficiency occurred at higher values of pH, slumping its efficiency to 58.90 ± 1.89% for TNZ and 64.33 ± 1.66% for MTZ, which signifies that the increase in the solution pH does not favor TNZ/MTZ degradation (Supplementary Table 4). This observation can be explained by the fact that at alkaline pH conditions, OH− ions of the medium tends to interact with the •OH radicals, resulting in the formation of weakly oxidizing hydroperoxyl radicals (HO2•) which are in agreement with previous reports56. These radicals further react with additional •OH radicals, resulting in the reduction of the removal efficiency57. Additionally, the lower efficiency observed for TNZ and MTZ at higher pH values stemmed not only from quenching effects, but also from the repulsive interaction arising between the anionic contaminant molecules and the surface of the synthesized CSHK‒Ni photocatalyst that is negatively charged at alkaline conditions58.

The optimization of catalyst dosage is necessary to prevent the excess use of photocatalyst and to reduce the operation cost. The effect of photocatalyst loading on the photodegradation of TNZ and MTZ having initial concentration of 20 mg/L, was investigated by varying the photocatalyst concentration from 0.16 g/L to 0.32 g/L at optimum H2O2 concentration. As seen in Fig. 13a, c, the photodegradation of target pollutants increases with increasing photocatalyst loading due to the increased number of surface-active sites and increased production of OH• radicals. However, a decline in the photodegradation efficiency was observed above 0.24 g/L for TNZ and 0.28 g/L for MTZ because excess photocatalysts in the solution hinder the path of photons from reaching the surface of the catalyst by increasing the opacity of the solution. The kinetics of the photodegradation of TNZ and MTZ are displayed in Fig. 13b, d. Maximum degradation of 95.87 ± 1.64% TNZ was observed at 0.24 g/L photocatalyst loading with a pseudo-first-order rate constant of 0.09591 min−1 (Supplementary Table 5). Similarly, a 97.95 ± 1.33% degradation of MTZ was observed with 0.28 g/L photocatalyst dosage having a rate constant of 0.11253 min−1.

Profiles of degradation of a TNZ (reaction conditions: H2O2 dosage 0.2 mL, TNZ conc. 20 mg/L, catalyst loading 0.16‒0.32 g/L, pH 3) and c MTZ (reaction conditions: H2O2 dosage 0.3 mL, MTZ conc. 20 mg/L, catalyst loading 0.16‒0.32 g/L, pH 3); degradation kinetics of b TNZ and d MTZ at varying catalyst loading.

The initial concentration of the contaminants exerts a crucial role in determining the effectiveness of the photodegradation reaction. Therefore, it is essential to optimize the highest concentration of target pollutants, which could be degraded under optimum H2O2 concentration and photocatalysts dosage. Figure 14a, c portrays the influence of initial concentration of TNZ and MTZ by varying the initial concentration in the range of 15 mg/L to 35 mg/L under the optimum concentration of H2O2 and photocatalyst dosage. As can be observed, a maximum degradation of 95.87 ± 1.64% TNZ with a rate constant of 0.09591 min−1 was observed at a concentration of 20 ppm, and a 97.95 ± 1.33% degradation of MTZ with a rate constant of 0.11253 min−1 was observed at a similar concentration (Supplementary Table 6). The degradation efficiency started to decline at higher pollutant concentrations of 35 mg/L, possibly due to the hindrance in the path of photons at higher pollutant concentrations and narrowing of photon path lengths59 (Fig. 14b, d). Additionally, an increased concentration of the pollutant would necessitate a higher amount of photocatalyst, which will increase the opacity of the solution and consequently hindering photodegradation60. Again, higher concentration of the target pollutants enhances the probability of the contaminant molecules to occupy more surface active sites, displacing the surface adsorbed O2 molecules and OH‒ ions4. This phenomenon inevitably leads to the insufficient generation of the ROS, such as •OH and •O2‒ radicals responsible for the photodegradation, thus reducing the overall efficiency of the photocatalyst. Therefore, 20 mg/L of TNZ and MTZ were fixed for further photocatalytic tests.

Profiles of degradation of a TNZ (reaction conditions: H2O2 dosage 0.2 mL, catalyst loading 0.24 g/L, TNZ conc. 15‒35 mg/L, pH 3) and c MTZ (reaction conditions: H2O2 dosage 0.3 mL, catalyst loading 0.28 g/L, MTZ conc. 15‒35 mg/L, pH 3); degradation kinetics of b TNZ and d MTZ at varying concentration of the target pollutant.

Possible TNZ and MTZ degradation mechanistic pathway

The reaction rate of the photodegradation process is significantly influenced by the concentration of ROS and the photoinduced charge carriers. To explore the impact of these radicals and charge carriers on the degradation process, various scavenging agents were added to the aqueous reaction medium to trap them and analyse their role in TNZ and MTZ degradation. For this purpose, 1 mM of 2‒butanol was added as quenching agent for •OH, ascorbic acid for •O2−, K2S2O8 for e− and Na2EDTA as h+ scavenging was employed. It can be observed from Fig. 15 that the introduction of 2-butanol resulted in the sudden decline in the photodegradation performance of TNZ and MTZ to 36.28 ± 1.32% and 42.19 ± 1.61%, respectively. Moreover, the degradation efficiency reduced to 49.27 ± 1.66% and 51.53 ± 1.23% for TNZ and MTZ in the presence of ascorbic acid, suggesting that •O2− radical contributed about 46.60% of the total degradation efficiency. These results indicate that both TNZ and MTZ underwent radical-based AOP. Furthermore, the role of other species such as e− and h+ were also investigated. It was observed that the presence of K2S2O8 and Na2EDTA had a relatively minor impact on the degradation performance, with removal percentages declining to 85.21 ± 1.47% and 89.51 ± 1.86% for TNZ and MTZ, respectively. Hence, it can be collectively summarized that the photocatalytic breakdown of the targeted contaminants is mainly controlled by both •OH and •O2− radicals, whereas the minor contribution of h+ in the degradation process cannot be neglected, consistent with previous literature findings.

Furthermore, the ESR spin-trap technique was conducted for providing evidence of the generation of various reactive oxygen species in the photocatalytic system under visible light irradiation61. Typically, the intensity of a EPR signal is directly proportional to the amount of spin62. 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) served as a spin trapping agent to detect •OH radicals, which exhibit a characteristic quartet EPR signal with an intensity ratio of 1:2:2:1, corresponding to the typical DMPO–•OH adduct structure (Supplementary Fig. 4a)63. Meanwhile, a strong quartet signal for DMPO–O2• − spin adduct with a peak intensity ratio of 1:1:1:1 reveals the existence of •O2− radical in the photocatalytic system (Supplementary Fig. 4b)64.

In view of the aforesaid discussions, the mechanism of the photodegradation of TNZ and MTZ in the presence of CSHK‒Ni photocatalyst can be elucidated as illustrated in Fig. 16. Meanwhile, the edge positions of conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB) can be estimated using the equations outlined below:

In the above equations, EVB and ECB signifies the potentials of the VB and CB, \({\boldsymbol{\chi }}\) denotes the absolute electronegativity of the semiconductor, the value of 4.5 eV is considered for Ee which represents the energy of the free electrons on the scale of hydrogen. Moreover, the optical bandgaps of the synthesized photocatalysts were calculated as explained in Fig. 4b.

The possible mechanistic pathway of the photodegradation process of TNZ and MTZ was proposed on the basis of the ROS identified from the scavenger experiments and the edge potentials determined from the VB‒XPS as shown in Fig. 17. Initially, the degradation process involves the photoexcitation of e⎺ to the CB from the VB of the fabricated CSHK‒Ni photocatalyst, when irradiated with visible light, owing to its better light harvesting behavior leading to the creation of positively charged h+ in the VB. As revealed by the PL analysis, the incorporation of the Ni(acac)2 complex and CuS into the structural skeleton of the MOF significantly reduces the recombination of charges by facilitating effective delocalization of the charges, thereby improving the photocatalytic performance. Moreover, the potential of the CB (ECB) of the CSHK‒Ni photocatalyst (−1.90 eV) is more negative compared to the O2/•O2− potential (−0.33 eV vs. NHE), allowing the dissolved O2 in the reaction medium to interact with the photoexcited electrons present in the CB to generate free •O2− species (Eq. (25)). On the other hand, the calculated VB edge potential (EVB) (+0.29 eV) is less positive compared to the potential needed for the production of •OH radicals (H2O/OH• = +2.8 eV vs. NHE). This restricts the probability of the production of •OH radicals by the oxidation of the H2O molecules by the photogenerated h+ present in the VB. The •O2− radicals engage with the H2O molecules, resulting in the generation of HO2• species, which subsequently interacts with additional water molecules to produce •OH radicals (Eqs. (26) and (27)). These active radicals possess the ability to oxidize the targeted contaminants by initiating multiple reactions leading to the mineralization of the contaminants into smaller compounds. Also, the introduction of H2O2 leads to the generation of •OH radicals, which can aid in the TNZ and MTZ degradation (Eqs. (28) and (29)). This is in accordance with the scavenging experiments that validates that both •OH and •O2− radicals exert dominant role in the degradation of the targeted contaminants. Additionally, the Cu2+ within the MOF undergoes reduction to Cu+ by trapping the photogenerated e−, which subsequently undergoes further oxidation in the aqueous medium (Eqs. (30) and (31))23,24. This process results in the generation of more •OH radicals, indicating the availability of more time for the photogenerated charges to generate increased ROS before undergoing recombination, thereby promoting the overall photocatalytic performance of the designed catalyst.

HR‒LCMS was performed to analyze the degradation products of TNZ and MTZ at an intermediate stage, and the most probable pathway was elucidated based on the identified by‒products, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 5a, b. The •OH and •O2− radicals were identified as the active ROS which initiate the breakdown of the C–C bond and the aromatic ring at C–N bond in TNZ under 30 min irradiation of visible light, thereby generating the reaction intermediates. The loss of an R‒NO2 group due to the subsequent radical addition reactions, leads to the formation of the product with m/z = 17856. Subsequent bond rupture generates ‒CH3, yielding product at m/z = 149. Furthermore, the electrophilic attack of the •OH radicals produced in the system and the loss of the ‒NO2 group results in the formation of the intermediates at m/z = 297 and 220, respectively. Moreover, the cleavage of the aromatic ring and the alkyl group after the attack of radicals, yields intermediates at m/z = 236, 108 and 164 as shown in the proposed degradation pathway (Fig. 18)58.

Similarly, the photodegradation pathway of MTZ was elucidated by identifying the reaction intermediate products formed via the cleavage of the C‒N, C‒O and the aromatic ring at the C‒C bonds of the MTZ molecules. The proposed breakdown pathway based on the HR‒LCMS spectrum is illustrated in Fig. 19, where the peak at m/z = 171.5 corresponds to the MTZ molecular ion65. The other observed intermediates include fragments at m/z = 188, formed by the electrophilic attack of the •OH radicals; whereas oxidation of the ‒OH group and reduction of the ‒NO2 group yields fragments at m/z = 206 and 165, respectively6. Additionally, ring cleavage at the C‒N bond of the aromatic ring generates fragments at m/z = 149 and 188 as shown below66.

Impact of different factors on the photodegradation of TNZ and MTZ

Studying the effect of the various inorganic salts typically found in the wastewater effluent or natural aquatic medium on the photodegradation performance of the catalyst is of crucial importance. Investigating how these ions influence the degradation of TNZ and MTZ in the presence of the CSHK‒Ni photocatalyst under visible light radiation is vital for deepening our comprehension of the degradation mechanism.

Wastewater effluent and natural aquatic resources harbor diverse inorganic metal cations, including Na+, Ca2+, Al3+ and Fe2+, which due to their stable states of oxidation, do not exert a direct impact on the photocatalyst. For exploring the consequence of the specified cations on the elimination of TNZ and MTZ, aqueous solutions (0.01 M) of Na2SO4, CaSO4, Al2(SO4)3 and FeSO4 were separately added in to 20 mg/L aqueous pollutant solutions with a catalyst concentration of 0.24 g/L and 0.28 g/L for TNZ and MTZ, respectively. It can be understood from Fig. 20a that the presence of these metal cations suppresses the photodegradation efficacy of the fabricated catalyst to variable extents, following the trend Al3+ > Ca2+ > Na+ > Fe2+. The diminished performance may be attributed to the propensity of these cations to readily adsorb on the surface of the catalyst, thereby blocking the surface-active sites for ROS generation, causing a decline in the efficacy of the catalyst. Interestingly, the maximum inhibition of the photocatalytic efficiency was observed with Al3+ ions, possibly due to the strong affinity of the metallic cation to be adsorbed on the photocatalyst surface, owing to its higher charge density. Notably, Ca2+ exhibited a more pronounced effect in the degradation efficiency compared to Na+, likely due to its higher charge density. On the contrary, a change in the trend was witnessed for Fe2+ ions which could be explained considering that Fe2+ ion serves as an excellent Fenton reagent, augmenting the production of •OH radicals, consequently enhancing the photodegradation of TNZ and MTZ as highlighted by the following equation:

Various studies have reported that the existence of different inorganic anions in effluent water can impede the degradation efficiency of the as–prepared catalyst by disrupting the generation of reactive oxygen species during the photodegradation mechanism. As previously mentioned, the consequence of the multiple inorganic anions was comprehensively examined by individually introducing aqueous solutions (0.01 M) of NaCl, Na2SO4, Na2CO3 and NaNO3 into 20 mg/L pollutant reaction. The observed decline in the photocatalytic efficiency can be explained by two major factors: firstly, the occupation of the active sites present on the catalyst surface by the inorganic anions, which inhibits the generation of ROS, and secondly, the scavenging behavior of the anions, contributing to the decline in the catalytic performance. The addition of these salts unmistakenly illustrates a substantial reduction in the degradation performance of the model contaminants in the order Cl−< CO32−< SO42−< F−, as displayed in Fig. 20b.

Compared to the other anions, the Cl− anions had a more noticeable inhibitory effect owing to their active participation as scavengers of h+ and •OH radicals, which follow second order kinetics as further discussed below67,68:

The impact of Cl⎺ ions on the photodegradation performance surpasses that of other inorganic anions, primarily due to their significant quenching action. These ions interact with the photoinduced h+, leading to the generation of active radicals of chlorine. Moreover, they engage in reactions with •OH radicals, causing the oxidation of Cl⎺ ions and forming •Cl active radicals, which can subsequently revert to Cl⎺ ions by interacting with e⎺. As a result, these non-oxidizable metal anions compete with the pollutant molecules for reaction with •OH radicals, potentially hindering the degradation of TNZ and MTZ.

The influence of SO42− and F− ions on the degradation performance is minimal, which may be explained by the formation of •SO4− active radicals as a result of their interaction with •OH radicals, which serve as highly potent oxidizing agent compared to •OH radicals69. These •SO4− radicals also aid in the decomposition of the contaminants as follows:

The relatively minor decrease in the degradation performance associated with CO32⎺ ions in contrast to Cl⎺ indicates a weaker inhibitory effect of CO32⎺ ions. Furthermore, they react with •OH species, yielding • CO3⎺ free radicals as illustrated in the following reactions:

The F− ions are known for their stability and exhibit resistance to oxidation by h+70,71. Nevertheless, these inorganic ions are able to occupy the catalyst surface, thereby obstructing the formation of surface •OH active radicals. Furthermore, it can be summarized that the existence of inorganic ions did not significantly impair the degradation efficiency, highlighting the exceptional stability of the designed material in the wastewater system.

In addition to the inorganic impurities, the presence of several dissolved organic compounds of varying degrees in the wastewater effluent, competes with the target contaminant and influence the process of photodegradation. Hence, it becomes essential to explore the potential implications of these typical organic compounds, which includes urea, humic acid (HA), acetone, fulvic acid (FA), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and nitrobenzene (NB) on the functionality of the ternary photocatalyst in the degradation of TNZ and MTZ under optimal reaction conditions as shown in Fig. 21a. Urea is typically employed as a nitrogenous fertilizer, feed additive and is used as a raw ingredient in various industrial sectors dealing in polymers. Again, HA and FA are typically found as dissolved organic matter (DOM) in water bodies, whereas nitrobenzene is released by the petroleum refineries and chemical manufacturing industries. SDS functions as a surfactant and is commonly employed as a capping reagent in the synthesis of nanoparticles. It is also extensively utilized in detergents, toothpaste, shampoo and shaving cream. Acetone, on the other hand, serves as a highly effective solvent in numerous industrial processes and organic synthesis. The results demonstrate the inhibition of the photodegradation of the target pollutants by the above‒mentioned organic compounds in varying degrees owing to their scavenging properties. The maximum negative impact in the degradation effectiveness was exhibited by SDS, which could be due to the reduction in the visible light intensity reaching the surface of the catalyst and the generation of SO42− ions in the process of SDS photolysis. Again, the presence of FA and HA notably impeded the photocatalytic efficiency by hindering the penetration of light into the reaction medium for ROS generation, because of the increased opacity of the solution. Moreover, these organic substances competed with the targeted TNZ and MTZ molecules for their interaction with the •OH radicals, as outlined in Eqs. (43–49), thus, inhibiting TNZ and MTZ degradation.

Since •OH radicals are highly electrophilic, they attack organic molecules that typically contain a variety of electron‒rich sites, leading to their degradation.

For acetone, the slight reduction in the degradation efficiency was recognized for its photosensitization and inhibitory phenomenon which can be described as follows:

Although the produced •OH species facilitated the degradation of TNZ and MTZ, however, the acetone molecules also compete with the contaminant molecules for the active sites of the photocatalyst for its decomposition, thereby diminishing the degradation efficiency. The photodegradation of TNZ and MTZ was inhibited by the presence of the dissolved organic compounds, indicating that these DOM were also undergoing degradation alongside the targeted TNZ and MTZ molecules in the solution. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of the prepared photocatalyst in the elimination of various dissolved organic compounds present in the wastewater effluent, highlighting its potential as a photocatalyst for wastewater remediation.

To evaluate the consequence of the different water matrices on the degradation performance of the catalyst, photocatalytic experiments were performed in five different water samples under optimum conditions as shown in Fig. 21b. As can be inferred, the degradation efficiency of the fabricated ternary CSHK‒Ni photocatalyst towards TNZ varied in different environmental conditions exhibiting 94.86 ± 1.31% for mineral water, 89.76 ± 1.37% for tap water, 83.42 ± 1.66% for lake water, 80.17 ± 1.73% for rain water and 76.49 ± 1.87% for river water. On the contrary, the maximum degradation efficiency towards MTZ obtained was 96.84 ± 1.25% for mineral water, 90.32 ± 1.44% for tap water, 85.19 ± 1.76% for lake water, 81.25 ± 1.82% for rain water and 78.89 ± 1.88% for river water. The presence of light attenuation and various organic compounds and inorganic ions that inhibit photocatalysis in these environmental water matrices, in varying concentrations, primarily contributed to the overall decrease in the photocatalytic efficiency. Mineral water, among all the experimental samples, exhibited the least reduction in the efficiency because of the lack of DOM and any impurities. The higher concentration of minerals and DOM in river water compared to lake and tap waters and their scavenging phenomenon could account for the comparatively poorer performance of the photocatalyst in the former matrix.

Elimination of other common pharmaceuticals

In order to mitigate environmental and human health risks, it is imperative to eliminate pharmaceutical residues from wastewater, which otherwise, infiltrates the aquatic bodies and pose threats to both the quality of the drinking water and the aquatic ecosystem at large. In this light, a study was conducted to assess the removal of various other commonly found pharmaceuticals, including Pantoprazole (PTZ), Ranitidine (RNT), Ofloxacin (OFL) and Amoxicillin (AMX) in wastewater effluent under optimized reaction conditions, as portrayed in Fig. 22. Pantoprazole and Ranitidine, popularly employed as a protein pump inhibitor to treat issues related to the digestive system, were eliminated by 81.52 ± 1.26%, and 43.19 ± 1.52%, respectively at optimal conditions. Ofloxacin, an anti‒microbial drug, were observed to be eliminated with a maximum degradation efficiency of 75.98 ± 1.66%, whereas the degradation efficiency of Amoxicillin was found to be 69.54 ± 1.33%, respectively.

Assessment of TOC and COD removal

A comprehensive assessment of the TOC removal was conducted to evaluate the mineralization efficiency during the degradation of TNZ/MTZ using the synthesized CSHK‒Ni photocatalyst. Figure 23a demonstrates that initially pristine HKUST‒1 and CuS/HK exhibited poor mineralization efficiencies of 2.63% and 29.44%, respectively for TNZ. On the other hand, for MTZ, it was found to be 2.89% and 38.13% (Fig. 23b). However, the TOC removal interestingly increased to 80.02% and 83.67% for TNZ and MTZ, respectively for the CSHK‒Ni photocatalyst, with a degradation efficiency of 95.87 ± 1.64% and 97.95± 1.33%.

Furthermore, the COD removal of the photodegradation of TNZ and MTZ was measured at various time intervals. Under optimized reaction conditions, a COD removal efficiency of 88.06% and 90.23% was achieved for TNZ and MTZ respectively. The high values of TOC and COD removal efficiencies suggested the facile breakdown of the targeted TNZ and MTZ molecules to CO2 and H2O in the course of the degradation by the generated ROS. The intermediates produced during the degradation process was validated by HR‒LCMS analysis.

Comparison with other photocatalysts for TNZ/MTZ degradation

Several nanocomposites have been documented for the photodegradation of TNZ and MTZ from aqueous medium as described in Table 1. However, the fabricated CSHK‒Ni photocatalyst reported in this study showcased exceptional efficiency even at low catalyst doses and short duration under visible light irradiation.

Reusability analysis

Recyclability is the most desired property of a photocatalyst to examine its stability and maximize its reusability potential. Hence, the recycling of the prepared CSHK‒Ni photocatalyst was investigated at optimum conditions over several runs, prior to its separation via centrifugation, repeatedly rinsing it with ethanol and distilled water and subsequently drying it at 80 °C overnight. As illustrated in Fig. 23c, the fabricated photocatalyst exhibited an impressively high (>78%) catalytic efficiency without any significant decline for up to four consecutive cycles. However, a minimal decrease in the catalytic performance may result from the potential blockage of the catalytic active sites and the pore channels of the CSHK‒Ni by the degradation intermediates. This leads to the decrease in the catalytic performance of the catalyst in subsequent runs. Furthermore, XRD analysis of the reused catalyst was conducted to assess the stability of the catalyst. As observed from the spectrum in Supplementary Fig. 6a, the XRD spectrum of the reused catalyst closely resembled with that of the fresh CSHK‒Ni catalyst, with the characteristic peaks of the HKUST‒1, CuS and Ni(acac)2 remained intact. However, the intensity of the (511) lattice plane is observed to decrease, besides the disappearance of (551) and (773) plane of the MOF. During the course of the photocatalytic reaction, some of the reaction intermediates formed may get partially trapped over the surface and the pore channels of the CSHK‒Ni catalyst, obstructing the surface-active sites, despite being repeatedly rinsing with ethanol and distilled water. The accumulation of these species over the course of successive catalytic runs, can potentially contribute in the change in the intensity of the peak. This can be validated by the observed decrease in the photocatalytic efficiency to 63.09±1.46% and 68.72±1.82% of TNZ and MTZ respectively, during the fifth run. Additionally, the aggregation of the catalyst particles across multiple reaction cycles might induce changes in the peak areas in the XRD pattern which can be observed from the SEM image of the reused catalyst presented in Supplementary Fig. 6b. A comparative analysis of the SEM images of the CSHK–Ni catalyst prior to (Fig. 5b) and after multiple catalytic runs (Supplementary Fig. 6b) reveals that the catalyst nanoparticles have agglomerated. This is associated with the observed changes in the XRD peak areas of the reused catalyst and the decline in the efficiency of the photocatalyst. Furthermore, the adsorption of reactive species on the catalyst surface may also alter the lattice parameters.

Comparative cost analysis

The cost implication of a catalyst plays a critical role in evaluating its commercial viability, applicability, and scalability in real-world scenarios. The overall cost of a catalyst encompasses several components such as the cost of raw materials, expenses for drying, washing, chemical aggregation, energy consumption, labor and transportation charges and the recyclability of the catalyst72,73. The commercial feasibility of large-scale wastewater treatment is determined by the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the fabricated catalyst. Table 2 provides a detailed cost analysis for the step-by-step preparation of 1 g of CSHK‒Ni catalyst, with all costs presented in US dollars ($).

The results unveiled that the estimated total cost for the synthesis of 1 g of CSHK‒Ni catalyst approximates to about $0.021, which was considerably lower than the estimated costs of other catalysts previously reported for wastewater treatment, such as hierarchical ZnS‒Ga2S3, 0.5 M-rGO-PEG, Fe3O4@MIL-101, NH2-MIL-88(Fe), and BUC–17. Additionally, the fabricated CSHK‒Ni nanocomposite in this study demonstrated superior cost-efficiency while offering significantly higher performance. Recently, a study performed by Qi et al. estimated that the cost of producing 1 g of hierarchical ZnS‒Ga2S3 for Cr (VI) removal from wastewater effluent is about $0.089574. In contrast, the estimated cost of manufacturing 0.5 M-rGO-PEG was significantly higher at approximately $2.88/g (54.068 ZAR)75. Therefore, MOFs are often viewed as frugal and cost-effective options for wastewater remediation. Biswal and his colleagues reported that BUC‒17 MOF is the most expensive at $5/gram, whereas Fe3O4@MIL-101 and NH2-MIL-88(Fe) cost around $1 and $0.5 per gram, respectively76. Given that these cost estimates are based on laboratory data and may fluctuate over time, they might not precisely represent the costs at an industrial scale. However, they provide a useful benchmark for evaluating the economic feasibility of the CSHK‒Ni catalyst. Therefore, from a commercial standpoint, the designed CSHK‒Ni catalyst appears to offer a promising and cost-effective solution for large-scale wastewater treatment.

Discussion