Abstract

In this study, a novel N, S-co-doped carbon-based Ag3PO4 composite photocatalyst (N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB) was synthesized using activated biochar (ACB) as a carrier and used for the efficient removal of norfloxacin (NOR), a typical bio-refractory antibiotic. We systematically investigated the degradation effects, actual wastewater treatment, the impacts of environmental factors, and the degradation pathways. The results show that N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB is essentially a p-n heterojunction with Z-scheme of Ag2S/Ag3PO4/ACB composite containing Ag nanoparticles. After 120 min of irradiation, N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB removed 90.42% of an initial NOR concentration of 50 mg L–1. The activation of graphitic N and the lone electron pairs of N and S, promoted rapid photogenerated charge transfer. Furthermore, the surface properties of ACB promoted free radicals generation, and the surface plasmon resonance effect of the Ag nanoparticles synergistically enhanced the photocatalytic activity. A new degradation intermediate of NOR was identified, and the degradation dynamics were elucidated with three main pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The excessive use and unchecked disposal of antibiotics can cause water and environmental pollution, which can hinder social and economic development1. Norfloxacin (NOR), a third-generation quinolone antibiotic, is widely used in the medical, aquatic, and animal husbandry industries because of its good pharmacokinetic properties, low cost, excellent antimicrobial properties, and ability to be used in conjunction with other antibiotics without cross-infection2,3. However, NOR cannot be fully metabolized in living organisms and has a long half-life in the environment, resulting in easy accumulation especially in surface water, groundwater, and even drinking water4, which has been detected in many countries around the world3. Residual NOR is highly toxic; for example, it induces heart disease, stroke, and other diseases, causing resistance genes and bacterial genotoxicity5. Thus, methods for removing NOR from aqueous environments must be urgently developed6. Photocatalysis is one of the most effective and promising technologies for the degradation of antibiotics4. Extensive research showed that the development of semiconductors and composite materials with a visible-light response is essential for real applications7. Silver phosphate (Ag3PO4) is an important silver N-type semiconductor with strong photo-oxidation properties and a high quantum yield under visible light irradiation and has attracted significant attention8. Ag3PO4, from the cubic crystal system, absorbs <530 nm visible light with a suitable band gap (2.36–2.43 eV) and a deep valence band (approximately +2.90 eV) relative to the normal hydrogen electrode (NHE, pH = 0), making it suitable for oxidation reactions8,9. This is attributed to the introduction of p-region Group VA non-metallic P elements into Ag2O, forming stable PO4 tetrahedra in Ag3PO4 and modifying the energy band edge10. However, the micro solubility of Ag3PO4 in water and the photocorrosion phenomenon caused the loss of photocatalysts, which affected the activity and stability of photocatalysis, thus limiting its large-scale application11.

Researchers have developed cost-effective methods to improve the visible-light photocatalytic performance of Ag3PO4, including construction of heterojunctions via composites with carbon materials9, elemental doping10, and structural modulation12. Biochar is a low-cost, green mesoporous carbon material with abundant environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs), surface oxygen-containing functional groups (OFGs), and unique defects13; thus, it is used as a carrier or co-catalyst for mediating a variety of catalytic reactions14. Wei et al.15 synthesized biochar-based Ag3PO4 photocatalysts via the ball milling-pyrolysis-precipitation method and explored the effects and mechanisms of synergistic adsorption-photocatalytic removal of methylene blue. Nevertheless, this preparation method is cumbersome and this cationic dye is highly photosensitive, and the initial concentration selected is low, resulting in significant removal. Wang et al.9 further found that biochar-based Ag3PO4 composites were easily prepared using a co-precipitation method and that the porous structure and surface properties of the carriers (biochar) contributed to the enhancement of pollutant adsorption, hence the excellent removal of cationic dyes at high concentrations. However, the previous research suffers from too long degradation time for antibiotics. To further enhance the photocatalytic activity of biochar-based Ag3PO4 composites, numerous studies have focused on the design strategies of metal-ion doping16, polymer composites17, or composites with metal-type semiconductors to construct heterojunctions18,19. Qian et al.20 used hydrothermal impregnation to incorporate biochar into Ag3PO4/α-Fe2O3 heterojunctions to enhance the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and application in the degradation of low concentrations of tetracycline and ciprofloxacin (20 mg L–1). Unfortunately, these reports still lack a systematic elaboration of the mechanisms of enhanced photocatalytic roles and probing evidence of the synergistic effects of dopant ions21. Furthermore, these methods mainly targeted non-antibiotic organic pollutants. Additionally, when investigating the degradation of antibiotics, the environmental impact was not comprehensively evaluated, limiting the removal of antibiotics at high initial concentrations, thus limiting their industrial applications9.

Another important design strategy involves activating Ag-based composite photocatalysts using non-metal ion doping22. However, the studies are not comprehensive11,21; therefore, the design of composite photocatalysts based on this strategy should be further investigated to improve the efficiency of environmental applications and promote green development. Common non-metallic doping includes C, N, S, B, and other heteroatoms; these dopants may modulate the interaction forces between the material skeleton and the molecules22. Additionally, co-doping of two heteroatoms may further modulate the chemical composition and porous structure of materials23. Currently, the most remarkable applications are N and S co-doped carbon materials, which are attributed to the synergistic effects between N and S24. Mao et al.25 prepared an N and S co-doped biochar-based Bi2WO6 composite that exhibited excellent performance in reducing the band gap energy and promoting photogenerated carrier separation. Shabir et al.26 suggested that co-doping effectively lowers the bandgap of TiO2 and reduces the recombination rate between photogenerated electrons and holes, while the doped material serves as an active site for adsorbing pollutants for photodegradation23. Moreover, owing to the synergistic effect of numerous ions in co-doping, the light absorption range increases, thus enhancing photocatalysis. However, the synergistic mechanism and influencing process need to be discussed in detail27. Thus far, few studies have been conducted on N and S co-doped biochar-based Ag3PO4 composite photocatalysts. Additionally, there are few studies on the photocatalytic removal of NOR at high concentrations and the synergistic mechanisms of N and S co-doping. Therefore, in this study, a novel N, S co-doped biochar-based Ag3PO4 composite photocatalyst (N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB) was prepared via hydrothermal synthesis and chemical co-precipitation method using thiourea as the precursor. First, several advanced methods were used to characterize the physicochemical and optical properties of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB. Thereafter, the application of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB for NOR degradation and wastewater treatment was investigated, along with its recyclability and photostability. Subsequently, the photogenerated carrier behavior of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB was analyzed using electrochemistry; the main active species were identified via capture experiments. The mechanisms through which N, S co-doping synergistically enhanced photocatalysis were elucidated. Finally, the dynamic degradation transformation of NOR by N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB was explored using three-dimensional excitation-emission matrix fluorescence spectra (3D EEMs), and the possible degradation pathways of NOR were elucidated employing high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS). This paper is expected to introduce new perspectives on the photocatalytic mechanisms of N, S co-doping and biochar synergistic enhancement of Ag-system semiconductors, as well as provide key research ideas for the degradation process of NOR and newly identified degradation intermediates.

Methods

Chemical reagents

Silver nitrate (AgNO3), sodium phosphate dibasic (Na2HPO4), thiourea (CH4N2S), NOR (C16H18FN3O3), potassium hydroxide (KOH), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), hydrochloric acid (HCl), p-benzoquinone (BQ), tert-butyl alcohol (TBA), ammonium oxalate (AO), manganese acetate (MA), and common solvents were used in this study and were ordered from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Ultrapure water was employed throughout the experiments. All chemicals and solvents were of analytical grade and did not require further purification.

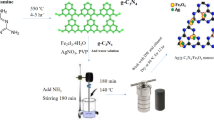

Preparation of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB

To obtain biochar, Caragana korshinskii biomass (collected from Guyuan City, Ningxia Autonomous Region, China) was sheared and pyrolyzed at 650 °C for 3 h in an argon atmosphere. Subsequently, the activated Caragana korshinskii biochar (ACB) was obtained via ultrasonic activation combined with KOH pore-making treatment at 700 °C for 1 h to remove impurities. All temperatures were increased at 5 °C min–1 in an argon atmosphere.

AgNO3 (25 mL, 0.2 mol L–1) was added to ACB (1.00 g) and the mixture was ultrasonicated for 1 h, and was further stirred for 1 h. Thiourea (0.60 g) and 100 mL of ultrapure water were added and ultrasonicated for 30 min. Following this, the mixture was transferred to a Teflon™ -equipped autoclave (SLM 250, Beijing Sen Long Reactor Co., Ltd, China) with a controlled fill ratio of ~60% and hydrothermally reacted at 105 °C for 3 h (with stirring). After cooling, the mixture was removed from the autoclave, and 25 mL of AgNO3 was added; the mixture was ultrasonicated for 1 h and further stirred for 1 h. In an environment protected from light, 9 mL of Na2HPO4 (0.2 mol L–1) was added dropwise to the abovementioned mixture with constant stirring, followed by ultrasonication at 50 °C for 2 h and stirring for 2 h. Finally, the mixture was suction-filtered and activated in an oven at 80 °C to obtain the solid N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB, which was ground and passed through a 0.15 mm mesh sieve. The control materials Ag3PO4 and Ag3PO4@ACB were prepared similarly. The simple N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB preparation procedure is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Experiments and characterization

The removal effects of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB on NOR in an aqueous solution and actual wastewater were investigated via typical adsorption–degradation experiments. Three parallel and control tests were set up for all experiments. Important experimental parameters are labeled in the figure of the result analysis. X-ray diffraction (XRD), Scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), high-resolution TEM (HRTEM), Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR), Raman spectroscopy, ultraviolet-visible/diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV–vis/DRS), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) specific surface area (SBET) and pore size analysis, three-dimensional excitation-emission matrix fluorescence spectra (3D EEMs), inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), steady-state photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy, photoelectrochemical properties including transient photocurrent response (PC) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and electron spin resonance (ESR) were performed in this work. The detailed experimental procedures, material characterizations (to investigate the basic physico-chemical properties, structure, morphology, surface characteristics, and optical behavior of the prepared materials, etc.), and analysis methods can be found in a previously published paper7,9.

Results and discussions

Characterization

The XRD patterns of both Ag3PO4@ACB and N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB were indexed to the cubic phase crystal Ag3PO4 (JCPDS No. 06-0505), and the corresponding crystal faces were labeled (Fig. 2a). Additionally, 2θ = 25.9°, 28.9°, 31.5°, 34.4°, 40.7°, 43.4°, and 46.2° were matched to the monoclinic phase crystal Ag2S, which corresponded to the crystal planes (–111), (111), (–112), (–121), (–121), (031), (200), and (–123), respectively. The diffraction peak of Ag2S was relatively weak compared to that of Ag3PO4, matching the standard structure of JCPDS No. 14-007228. Moreover, the peaks of 2θ at 40.3° and 64.4° were fitted to the (200) and (220) planes of the cubic phase crystal Ag nanoparticles (JCPDS No. 04-0783) with a space group of Fm-3m(225). This may imply that some of the Ag+ was reduced to Ag monomers during ternary complexation29. Diffraction peaks of ACB were not detected because of the Ag2S/Ag3PO4 coverage, and the ACB exhibited an amorphous state. Therefore, N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB is a Ag2S/Ag3PO4/ACB heterogeneous photocatalyst that contains a few reduced Ag nanoparticles. Notably, S in thiourea chemically reacts with Ag via a hydrothermal reaction to produce Ag2S crystals.

FTIR (Fig. 2b) and Raman (Fig. 2c) spectra were employed to analyze the surface functional group and defect structure of the materials. The FTIR spectra of Ag3PO4@ACB and N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB were similar (Fig. 2b), and the typical infrared features of both ACB and Ag3PO4 were detected. Specifically, the broad –OH stretching vibrational peak near 3420 cm–1 is attributed to ACB, and the strong vibrational peaks near 1010 and 545 cm–1 are attributed to the P–O stretching vibration of PO43− from Ag3PO4. Moreover, ACB exhibits C–O stretching vibration at 1010 cm–1, but when ACB is complexed with Ag3PO4, this characteristic peak redshifts slightly to 1070 cm–1 owing to superposition. Additionally, the characteristic peak at 1630 cm–1 may be an O–H bending vibrational peak from the adsorbed water of Ag3PO4, and the characteristic peak at 1384 cm–1 may correspond to a C=O bond from ACB19. However, all these characteristic peaks of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB were slightly weakened by N and S co-doping.

There was no marked difference in the positions of the D and 2D bands of Ag3PO4@ACB compared with those of the characteristic peaks of ACB (Fig. 2c). The G band, which represents graphitic carbon, was slightly blue-shifted, probably owing to the interaction of Ag3PO4 with the graphitized structure of ACB. The intensities of these peaks were significantly weakened, indicating the combination of Ag3PO4 with the multilayer graphitized structure of ACB. With N and S co-doping, the D and G bands of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB were strengthened considerably, and the ratio of the D peak intensity to the G peak intensity was slightly higher than that of Ag3PO4@ACB. This observation indicates a higher degree of defects and disorder in the carbon crystals of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB, which may have facilitated the separation of photogenerated carriers therein. Mao et al.25 also suggested that co-doping with N and S affects the degree of defects in biochar; S may facilitate efficient chemical reactivity, whereas N may directly interact with carbon atoms to alter electrical conductivity.

The specific surface areas, pore volumes, and pore sizes are listed in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1. Figure 2d shows the adsorption-desorption isotherm, demonstrating that N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB exits a hysteresis loop at relative pressures of 0.60 to 0.95, which is a typical feature of mesoporous structures. The BET-specific surface area (SBET) of Ag3PO4@ACB was 148.19 m2 g–1, which is much less than that of ACB. When N and S were co-doped, the SBET of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB instead increased to 304.00 m2 g–1, which also increased the pore volume to 0.162 cm3 g–1 and decreased the average pore diameter to 2.13 nm. This suggests that the co-doping of N and S activated the pore structure of Ag3PO4@ACB, leading to redistribution of the Ag3PO4 crystals on the surface of ACB, and improved the active sites of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB30.

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM, Fig. 3) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM, Fig. 4) with an energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS, Table 1) enable the visualization of the microscopic morphology of the materials. The ACB had a porous honeycomb structure with a smooth surface and many exposed pore channels (Fig. 3a). Ag3PO4 displayed irregular particles and was densely embedded in the porous structure of the ACB. The growth of cubic crystals on the inner wall of the ACB may be attributed to electrostatically driven self-assembly between Ag+ and the negatively charged ACB on the surface9. Additional FESEM images are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1. Figure 3b indicates a similar morphology, with many crystal particles deposited inside the ACB pores. Figure 3c shows finer Ag2S microspheres stacked on Ag3PO4 particles to form a similar core-shell structure28, which implies that the Ag2S/Ag3PO4 combination was loaded together into the porous structure of the ACB. It is also possible that Ag2S/Ag3PO4 was most probably deposited separately on the surface of the thin layer of ACB (Fig. 3d). This is different from the Ag3PO4@ACB morphology (Fig. 3a), implying that the co-doping of N and S led to the formation of Ag2S/Ag3PO4 heterojunctions. To further verify the distribution of Ag2S/Ag3PO4 in this composite, elemental mapping was performed, as shown in Fig. 3e. It clearly shows that C, Ag, O, P, and S were uniformly distributed in N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB, confirming the formation of a heterojunction. Moreover, the relatively high level of S, whose distribution was similar to that of Ag, confirmed the production of Ag2S in the hydrothermal reaction.

ACB existed in the form of folded sheets, and Ag3PO4 and Ag2S were anchored on top of these folded sheets to aggregate and form deep black lattice spots (Fig. 4a). The lattice spacings of 0.2689 and 0.2454 nm in Fig. 4b may be assigned to the (210) and (211) planes of Ag3PO4, respectively, and the lattice spacing of 0.2836 nm matches the (–112) plane of Ag2S. The Ag2S/Ag3PO4 crystals were closely surrounded by the ACB interface, which indicates that the Ag2S and Ag3PO4 crystals are very close to each other and that the ternary heterojunction of Ag2S/Ag3PO4/ACB was successfully constructed. This was confirmed by the HRTEM images of the other investigated regions (Fig. 4c), where the (210) plane of Ag3PO4 and the (–112) plane of Ag2S were observed. Figure 4d displays a selected area electron diffraction (SAED) image of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB, which shows that the composite photocatalyst was polycrystalline31. The (–112) and (040) planes of Ag2S and (110), (210), and (220) planes of Ag3PO4 were identified. Thus, these micromorphological characterizations further confirm that N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB is essentially a composite Ag2S/Ag3PO4/ACB heterojunction.

Figure 5 shows the XPS spectra to characterize the bonded valence structure of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB. The survey spectra of this composite detected P 2p, S 2p, C 1s, Ag 3d, N 1s, O 1s, and followed by typical Ag 3p double peaks32, which further validated the co-doping of N, S into Ag3PO4@ACB. The binding energies corresponding to the valence states of these elements are labeled in Fig. 5a with atomic percentages matching the EDS results (Table 1). The high-resolution spectra of C 1s (Fig. 5b) could be deconvolved to three peaks at 284.8, 286.4, and 288.9 eV, corresponding to the carbon material backbones C–C, C–O/C–N, and O–C=O bonds, respectively, derived from ACB18. The O 1s high-resolution spectra (Fig. 5c) show two fitted peaks at 530.5 and 532.1 eV, which are attributed to lattice oxygen and adsorbed oxygen (–OH), respectively. In Fig. 5d, Ag 3d may be deconvoluted into four fitted peaks, with two strong characteristic peaks near 368.1 and 374.1 eV corresponding with Ag 3d5/2 and Ag 3d3/2 in Ag3PO4 (or Ag2S), respectively, indicating the presence of Ag+ in the composite28. Additionally, two weak peaks near 369.4 and 372.9 eV were attributed to nano Ag0 monomers, which is consistent with the XRD analysis of Ag/Ag2S/Ag3PO4 that is complexed to the ACB surface. In the S 2p spectra (Fig. 5e), the S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2 peaks at ~161.2 and 162.4 eV support the valence state of S2–, and the doublet separation energy of 1.2 eV is consistent with the valence characterization of the metal sulfides attributed to Ag2S33. The P 2p peak at 132.5 eV (Fig. 5f) indicates that P had a + 5 valence state, which was attributed to the valence state of P5+ in Ag3PO432. As shown in Fig. 5g, the N 1s separable peaks were fitted to two peaks at 398.2 and 400.8 eV, corresponding to C–N bonds and graphitized N, respectively. This implies that N doping mainly activates the biochar and affects the C atoms, all of which contribute to the defect structure of the ACB. Moreover, graphitized N facilitates the supply of active sites to enhance photoelectron migration in photocatalysis25. The XPS results further confirm that the N,S co-doped Ag3PO4@ACB is a heterostructure of Ag/Ag2S/Ag3PO4/ACB.

Optical properties

As illustrated in Fig. 6a, the maximum absorbance edge of Ag3PO4 was ~534 nm, and both Ag3PO4@ACB and N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB exhibited excellent absorption in the range of 200–800 nm. Moreover, with N and S co-doping, the average absorbance of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB (curve above) was substantially than that of Ag3PO4@ACB, which facilitated the complete utilization of visible light by N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB. The direct forbidden bands of Ag3PO4, Ag3PO4@ACB, and N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB were at 2.30, 2.04, and 1.86 eV, respectively (Fig. 6b); thus, the forbidden band of Ag3PO4 gradually decreased with the application of ACB as a carrier and after co-doping with N and S. This phenomenon was also confirmed by the indirect forbidden band shown in Fig. 6c, which displays similar results. The XPS valence band spectrum of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB (Fig. 6d) can be converted to valence and conduction bands at the NHE according to Eqs. (1) and (2), as reported by Wang et al.7. Thus, the valence band of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB is estimated to be 1.35 eV and the conduction band is –0.51 eV. In comparison, the valence and conduction bands of Ag3PO4 in a related study by Wang et al.9 were found to be 2.61 and 0.31 eV, respectively.

Adsorption-photocatalytic degradation of NOR performance

The NOR removal performance of the prepared materials was evaluated (Fig. 7). The removal of NOR at an initial concentration of 50 mg L–1 by N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB was 90.42% after 120 min of light exposure, compared with 74.17% and 35.45% for the control treatments Ag3PO4@ACB and pure Ag3PO4, respectively (Fig. 7a). These results demonstrate that the use of ACB as a carrier promoted the photocatalytic activity of pure Ag3PO4 and that N and S co-doping further enhanced the degradation efficiency of the Ag3PO4@ACB composite for NOR. The adsorption effect of ACB on NOR was substantially higher than that of Ag3PO4 because of the influence of the specific surface area. The adsorption–desorption equilibrium of ACB was reached within 60 min in the dark, after which the concentration of NOR decreased insubstantially with increasing irradiation time. Although Ag3PO4 exhibited limited adsorption of NOR in the dark, it could continuously photodegrade NOR after 120 min of irradiation. Consequently, the final NOR removal rate by Ag3PO4 was higher than that by ACB. This result also indicates that the removal of NOR by ACB proceeds mainly via physical adsorption, and the removal by Ag3PO4 proceeds mainly via photocatalytic degradation. The removal mechanisms of NOR by N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB and Ag3PO4@ACB included adsorption and photocatalysis; however, photocatalysis was dominant, judging from the combination of removal rate and reaction time.

a Adsorption-photocatalytic degradation of NOR using the prepared photocatalysts. b Pseudo-first-order kinetic curves of NOR by the prepared photocatalysts. c TOC removal efficiency. (Experimental conditions: initial concentrations of NOR at 50 mg L–1, photocatalysts dosage of 1 g L–1, initial pH of ~7.0, 500 W xenon lamp).

Figure 7b displays the pseudo-first-order degradation kinetic, and this degradation rate constant of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB was 0.0175 min–1 at 90 min of irradiation, which is 1.73 times higher than that of Ag3PO4@ACB (0.0101 min–1) and 5 times higher than that of Ag3PO4 (0.0035 min–1). The implies that N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB exhibited the strongest visible-light photocatalytic activity, and the N, S-co-doped composite design significantly enhanced the photocatalytic performance compared to Ag3PO4@ACB and pure Ag3PO4. However, in terms of the increased rate of pseudo-first-order kinetic degradation, the complexation of ACB as a carrier with Ag3PO4 was superior to N and S co-doping. Additionally, the total organic carbon (TOC) removal rate can demonstrate the mineralization ability of NOR and reflect the photodegradation performance. The TOC removal rate of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB after 120 min of irradiation was 69.67%, whereas those of Ag3PO4@ACB and Ag3PO4 were 53.72% and 36.55%, respectively (Fig. 7c). N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB displayed the highest TOC removal rate, which implied that N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB degraded NOR more completely and produced more degradation intermediates than Ag3PO4@ACB and Ag3PO4 over the same period.

Effects of environmental factors

Generally, environmental factors may affect the photocatalytic activity. As shown in Fig. 8a, the removal rate of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB gradually decreased as the initial concentration of NOR was increased from 20 to 60 mg L–1, and the rate of decrease also decreased. When the NOR concentration was 20 mg L–1, it was evident that N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB was almost completely degraded within 60 min of irradiation. When the NOR concentration was increased to 30 mg L–1, the time for complete degradation increased to 90 min. This was mainly related to the probability of interfacial contact between the solute composite and the reduction in effective composite active sites. High NOR concentrations (e.g., 60 mg L–1) inhibited photogenerated carrier transfer and decreased the photocatalytic degradation rate. The removal rate of NOR by N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB decreased in the following order: pH = 6.88 > pH = 8.87 > pH = 11.03 > pH = 4.91 > pH = 2.93 (Fig. 8b). This result suggests that the degradation of NOR by N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB is best in neutral environments, and that both acidic and alkaline environments inhibit it, even though acidic environments inhibit the degradation of NOR more than alkaline environments. Additionally, the degradation rate of NOR by N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB was reduced by 4.72% in an alkaline environment (pH = 11.03) compared to that at pH = 6.88, whereas it was reduced by 14.50% in an acidic environment (pH = 2.93). This implies that N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB may be buffered in alkaline environments and has little impact on the photocatalytic degradation of NOR. However, strongly acidic environments have a significant impact, which is related to the protonation of NOR and electrostatic repulsion at the nonhomogeneous interface25.

As shown in Fig. 8c, the NOR degradation rate by N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB gradually increased with increasing dosage. When the dosage was 2 g L–1, NOR was almost completely removed by irradiation for ~90 min. This is related to the larger SBET and surface-active sites of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB; the higher dosage of the photocatalyst significantly enhanced the adsorption of NOR and promoted the rapid transfer of degradation intermediates on the surface of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB. The effect of the coexisting ions on NOR degradation is shown in Fig. 8d. Overall, NaCl and NaNO3 treatments had little impact on the degradation of NOR; however, Na2SO4 and Na2CO3 treatments significantly reduced the degradation rate of NOR. Moreover, in the dark, there was little impact on the adsorption of NOR by N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB because of the low concentrations of these coexisting ions. The differences between the four different coexisting ions were mainly related to the charges carried by the coexisting ions, the molecular weight size, the crystal size of the salt ions, and the solution pH. Na2CO3 exhibited the strongest reduction of 16.97% owing to the alkaline nature of this treatment in solution.

Reusability and photostability

Based on the above typical adsorption-photocatalytic degradation experiments, five rounds of recycling tests were conducted to study the reusability and photostability of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB. The degradation rate of NOR by N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB decreased by 10.08% relative to the first cycle after five recycling tests (in Fig. 9a). This implied that the recyclability of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB was moderate. To further investigate the photostability of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB, the samples were centrifuged after five recycling tests and then washed with ultrapure water, and the recovered N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB were dried at 80 °C for 10 h before testing. XRD patterns and FTIR spectra were obtained of the recovered samples. As shown in Fig. 9b, the XRD results indicate that the crystal structure of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB was not significantly altered, except for the extra impurity peak at 2θ = 19.4° which is not matched to the crystal. The FTIR results (Fig. 9c) indicate a slight increase in the intensity of the –OH broad stretching vibrational peak at 3420 cm–1 after the recycling tests, which may be related to the adsorption of degradation intermediates containing –OH functional groups. The positions and characteristic peak intensities of the other surface functional groups of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB did not change significantly, indicating that the N, S-co-doped biochar-based composites had better photostability.

a Recycling performance tests of photocatalytic degradation for NOR removal using N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB. (Experimental conditions: initial concentration of 50 mg L–1,addition dosage of 1 g L–1, initial pH of ~7.0, 500 W xenon lamp). b The XRD patterns of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB before and after the recycling tests. c The FTIR spectroscopy of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB before and after the recycling tests. d Actual wastewater tests for NOR removal using N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB. (Experimental conditions: addition dosage of 1 g L–1, 500 W xenon lamp, no adjustment of other parameters).

Actual wastewater treatment

The degradation of NOR in wastewater 1# (from the rabbit plant) and wastewater 2# (from the chicken plant) by N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB was 71.80% and 82.88%, respectively, after 180 min of irradiation (Fig. 9d). Additionally, these industrial wastewaters contain interfering ions (Supplementary Table 2). However, the satisfactory degradation of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB in NOR-containing wastewater suggests that this composite photocatalyst has the potential to treat highly concentrated wastewater.

Photogenerated carrier behavior

The photoresponsivity and photocurrent density of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB were considerably higher than those of Ag3PO4@ACB and pure Ag3PO4 (Fig. 10a). The photocurrent density of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB increased with increasing irradiation time. However, as the light exposure time increased, the photocurrent density of pure Ag3PO4 remained constant, whereas that of Ag3PO4@ACB decreased slightly. This implies that the separation efficiency of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB for photogenerated electron-hole pairs is superior to that of Ag3PO4@ACB and Ag3PO4, which is mainly attributed to N and S co-doping to construct the Ag2S/Ag3PO4/ACB heterojunction, and that N enhances the electrical conductivity and defect degree of the composite. EIS Nyquist plots are shown in Fig. 10b, where N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB possesses a smaller Nyquist radius, implying that N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB has a lower charge transfer resistance and higher charge transfer efficiency than those of Ag3PO4@ACB and Ag3PO4. This suggests that N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB effectively prevented photogenerated carrier separation20. In addition, the introduction of ACB enhances the charge transfer of Ag3PO49. Figure 10c shows that Ag3PO4 produced a strong steady-state photoluminescence (PL) spectrum near 550 nm. Tian et al.28 demonstrated that the strong emission peak of Ag3PO4 is near 550 nm, indicating that the photon energy is approximately equal to its forbidden band energy (~2.4 eV), and is therefore considered to be a recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes derived from Ag3PO4. However, the spectra of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB and Ag3PO4@ACB exhibited significant blue shifts. This is mainly due to the introduction of ACB and the co-doping of N and S, suggesting that there is an intrinsic potential in the direction from Ag3PO4 to ACB and that strong interactions may lead to a redistribution of the interfacial charge density, that is, the electrons move from Ag3PO4 to ACB34. In summary, the electrochemical analysis and PL spectra confirmed that N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB possessed good photogenerated charge separation efficiency.

Roles of reactive species

Furthermore, the active species were identified to determine the reasons for the excellent performance of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB, and the role of the dominant free radicals in the synergistic enhancement of photocatalysis. Figure 11a shows that N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB degraded 90.42% of NOR without scavenger. When the addition of a scavenger reduced the degradation to 41.08%, 45.53%, 46.24%, and 87.45% in the BQ (corresponding to ·O2–), AO (H+), TBA (·OH), and MA (e–) treatments, respectively. This also implies that ·O2–, H+, and ·OH play a dominant role in this photocatalytic system. Additionally, the conduction band of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB is located at –0.51 eV, which is more negative than the O2/·O2– oxidation potential (–0.33 eV), which favors the system to produce more ·O2–. The valence band of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB is located at 1.35 eV, which is lower than the OH–/·OH oxidation potential (+2.40 eV); this does not favor the generation of ·OH. However, the surface of ACB contains several EPFRs, which could induce the generation of ·OH35.

To further verify this result, ESR was measured. No obvious 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO)-·OH (fourfold peaks) and DMPO-·O2− (sixfold peaks) signals were detected for N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB in the dark (Fig. 11b, c). However, after 10 min of irradiation, typical DMPO-·O2– and DMPO-·OH signals were observed, which indicates that N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB was able to produce ·OH and ·O2– radicals under visible-light irradiation. This result is consistent with those of the free-radical trapping experiments, suggesting that ·OH and ·O2– radicals play an important role in the degradation of NOR by N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB. Additionally, the co-doping of N, S could significantly enhance the DMPO-·OH signals of Ag3PO4@ACB (Fig. 11b, c), which is closely related to the defects and energy band structure of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB. Moreover, the use of ACB as a carrier increased the intensity of the DMPO-·OH signals of Ag3PO4, which may be attributed to the abundant EPFRs on the ACB surface35.

Synergistic mechanisms

Considering the above results, it could be inferred that the degradation mechanisms of NOR by N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB generally included three parts. First, NOR was adsorbed onto the surface of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB by physisorption and chemisorption, and related adsorption mechanisms have been reported previously9,30. Second, a non-homogeneous photocatalysis takes place at the interfaces between N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB and NOR to generate ROS, which gradually degrade NOR23. Finally, the degradation intermediates detach from the surface of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB, thus releasing the active sites, which reabsorb the NOR and the degraded macromolecular intermediates to continue photocatalysis. The ROS generated during photocatalysis are strongly oxidized until NOR is gradually mineralized to H2O and CO27.

The paths of the possible photogenerated carriers for N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB are illustrated in Fig. 12. According to Tian et al.28 and Shi et al.33 the conduction band (–0.025 eV) and valence band (0.0965 eV) of Ag2S were estimated to have larger negative potentials than the conduction band (0.31 eV) and valence band (2.61 eV) of Ag3PO4, respectively. Under visible light irradiation, both Ag2S and Ag3PO4 can be excited to produce photogenerated electrons and holes in their conduction and valence bands, respectively. For the double silver composite system, a small amount of Ag was inevitably produced under visible-light irradiation, as demonstrated in the XRD patterns (Fig. 2a) and XPS analyses (Fig. 5). The surface plasmon resonance (SPR) effect of the Ag nanoparticles enhances the photocatalytic efficiency of Ag3PO431. Moreover, the Fermi energy level of Ag is more negative than that of Ag3PO4, which facilitates the transport of photogenerated charges between Ag2S and Ag3PO4. Ag nanoparticles act as photogenerated carrier-binding sites with ACB during photocatalysis, resulting in the rapid combination of holes generated by photoexcitation near the valence band of Ag2S and photogenerated electrons near the conduction band of Ag3PO436. Therefore, in this composite system, the photocatalytic mechanism of the Z-scheme was more compatible. Additionally, a conventional Type-II heterojunction would not be favorable for the formation of ·O2– radicals, which contradicts the results of the free radical trapping experiments described above. Shi et al.33 concluded that the oxidation potential of H+ in the valence band of Ag2S is too weak to degrade organic pollutants and that the conduction band potential of Ag3PO4 is more positive than the O2/·O2– oxidation potential. Therefore, the e– accumulated in the conduction band of Ag3PO4 may not be able to generate ·O2– radicals via adsorbed dissolved oxygen. These typical Z-scheme heterojunctions (Fig. 12) promote the photocatalytic activity of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB over Ag3PO4@ACB.

Furthermore, the mechanisms of enhanced photocatalysis by synergistic N and S co-doping of biochar may include the following possible contributions. (1) Liu et al.30 suggested that the functional group density on the surface of metal- and heteroatom-doped biochar-based composites increases owing to the presence of N- and S-containing groups. This implies that N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB has improved affinity for pollutants and better adsorption properties than Ag3PO4@ACB. This is corroborated by the surface properties shown in Table 1, where N and S co-doping increased the specific surface area of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB, increased its pore volume, and reduced its average pore size. Moreover, in the N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB system, the lone pairs of electrons in N and S may act as electron donors. Specifically, the electronegativity of N (3.04) is higher than that of C (2.54), which may modify the electron transfer and affect the electron spin properties of biochar27. Additionally, N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB contains graphitic N (Fig. 5), which is considered the most favorable for the activation because the nonuniform distribution of graphitic N in the hexagon tends to cleave or dissociate the individual chemical bonds of the pollutants during their interaction with N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB30. The electronegativity of S (2.58) is close to that of the carbon atom, which could induce a spin charge in the carbon lattice of the biochar, creating more catalytic centers for N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB27. Moreover, Liu et al.30 reviewed many related reports and found that S-containing composites facilitated interfacial electron transfer between the photocatalyst and metal atoms because S could easily oxidize to S2–. (2) The surface porosity, defect structure, and OFGs of biochar are potential active sites14, which are enhanced during both the adsorption stage and the desorption-diffusion of degradation intermediates16,17. In addition, the high electrical conductivity of ACB promotes the transfer of photogenerated electrons7,14. Previous studies have also found that biochar surfaces contain many EPFRs that boost ROS generation in composites13. (3) Ag3PO4 is an n-type semiconductor37, whereas Ag2S is a p-type semiconductor; thus, a p-n heterojunction may be formed between them, which enhances the effective separation of photogenerated carriers38. Furthermore, Meng et al.39 proposed the concept of a photocatalytic relative p-n heterojunction; N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB may behave similarly, as well as being the Z-scheme transfer type of the p-n heterojunction, which reveals that the noble metal Ag loading and non-metallic N, S co-doping provided endogenous dynamics for photogenerated carrier migration.

Degradation process and pathways of NOR

Figure 13 shows the 3D EEMs spectra of the residual NOR solutions collected at different times. As shown in Fig. 13a, the initial NOR solution before irradiation exhibited a strong fluorescence characteristic peak at Ex/Em = 200–360/370–530 nm. This is significantly different from that reported by Liang et al.29 in which the original NOR exhibited two excitation/emission regions at Ex/Em = 250–300/425–475 nm and Ex/Em = 300–350/425–475 nm. The higher concentration of NOR (50 mg L–1) used in this study caused these two peaks to merge. NOR generates a strong fluorescent signal related to its molecular structure, and the excitation/emission region depends on the concentration of humic acid29. After 10 min of irradiation, the center of this large fluorescence peak was slightly red-shifted along the emission axis, which could be a humic acid-like substance produced by NOR photodegradation. As the photocatalytic reaction proceeded (Fig. 13b–d), this large fluorescence peak gradually divided into two smaller fluorescence peak; the peaks flattened and their intensities gradually decreased. Additionally, the center of this large fluorescence peak gradually blue-shifted along the emission axis, which may be attributed to the disruption of the conjugated heterocyclic structure of NOR, decomposition of NOR into small-molecule organics, and cleavage of specific functional groups in the degradation process. At 120 min of irradiation (Fig. 13e), the intensities of these two fluorescence peaks decreased significantly, indicating that the NOR molecules were photocatalytically degraded, and the concentration gradually decreased with further mineralization of the degradation intermediates. Thus, the 3D EEMs results showed that NOR molecules may be progressively degraded via N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB visible-light photocatalysis until complete removal.

The possible photocatalytic degradation intermediates of NOR by N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB were identified using HPLC-MS. Detailed mass spectra are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, and the deduced intermediate degradation products are presented in Supplementary Table 3. Based on the data for the degradation intermediates and the results of the 3D EEMs analysis, possible degradation pathways for NOR were proposed, as illustrated in Fig. 14. Pathway I involved photocatalysis by the NOR transformation mechanism of substituted F atoms, quinolone group transformation, and piperazine ring cleavage. First, the ·OH generated via photocatalytic degradation replaced the F atoms in the NOR, converting NOR to P1 (m/z = 318). Subsequently, the continued addition of two hydroxyl groups to the C atom in the NOR-unsaturated bond preferentially produced P2 (m/z = 352), whereas P3 (m/z = 323) was produced by loss of the –HCO bond. Similar degradation pathways have been reported by Chen and Chu40 and Shah et al.41 in which NOR directly formed P1 and P3 by replacing F and losing the –C=O bond42. Next, P3 was converted to P4 (m/z = 277) by the loss of the –HCOOH bond, which was then converted to P5 (m/z = 251) by cleavage of the piperazine ring and loss of the –C2H2 bond. P5 extracted electrons from N, and the C–N bond was cleaved, followed by the loss of the ethylenediamine group (–NH2–CH2–CH2–NH2 chain), which in turn was converted to P6 (m/z = 192). Finally, owing to the continuous attack of ROS on the C atom, NOR and some of the intermediates were converted to P7 (m/z = 107) through a series of reactions. In summary, degradation pathway I is associated with the replacement and elimination of F atoms, ring opening, decarboxylation for quinolone group conversion, and possible piperazine ring cleavage through the loss of the ethylenediamine group. As indicated by degradation pathway II, the original NOR was gradually converted to P8 (m/z = 296), mainly by decarboxylation and opening of the piperazine ring during photodegradation, after which the alkyl group was removed to produce P11 (m/z = 227). Additionally, the unsaturated carbon atom in NOR may also be converted to P9 (m/z = 290) by decarboxylation and dehydrogenation reactions, and lose O to form P10 (m/z = 276). In summary, degradation path II is associated with decarboxylation and dealkylation. For degradation pathway III, the original NOR was converted to P12 (m/z = 336) via the addition of hydroxyl groups (·OH instead of H) during ROS oxidation which was then converted to P13 (m/z = 352) through the replacement of F atoms with hydroxyl groups. This was immediately followed by conversion to P14 (m/z = 346) via dehydroxylation, deoxygenation to P15 (m/z = 332), opening of the piperazine ring to P16 (m/z = 291), and complete removal of the remaining piperazine ring to P23 (m/z = 234). Moreover, the degradation intermediate P12 (m/z = 336) may also be directly converted to P17 (m/z = 350) by opening the piperazine ring under the action of ROS, followed by deoxygenation to produce P18 (m/z = 322) or P19 (m/z = 322), two tautomers. The conversion was continued by deoxygenation to P20 (m/z = 294) and deamidation to P21 (m/z = 279). Finally, it was converted to P22 (m/z = 261) by replacing the F atom and to P23 (m/z = 234) by removing the piperazine ring in the presence of ROS. Overall, degradation pathway III involves the oxidative cleavage of the piperazine ring by ·OH and the replacement of F. This pathway III is supported by Li et al.6. Notably, the NOR degradation intermediate P7 (m/z = 107) in this study has rarely been found in previous reports.

Discussion

A novel N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB composite was prepared via hydrothermal synthesis and chemical co-precipitation. The degradation pathway of NOR and the factors affecting the degradation were investigated, revealing the synergistic enhancement mechanisms of biochar with N and S co-doping. Multiple characterizations showed that N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB is an Ag2S/Ag3PO4/ACB composite photocatalyst with a Z-scheme p–n heterojunction containing Ag nanoparticles. N, S co-doping further enriched the elemental composition, surface functional groups, and defects of the biochar-based composite, activating its pore structure and increasing its specific surface area (304.00 m2 g–1) and pore volume. N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB exhibited absorbance from 200 to 800 nm; furthermore, its forbidden band was narrowed (1.86 eV), and its conduction and valence bands were –0.51 and 1.35 eV, respectively. N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB degraded 90.42% of NOR (50 mg L–1) after 120 min of irradiation; this removal rate was significantly higher than that of Ag3PO4@ACB and Ag3PO4. The degradation rate constant was 0.0175 min–1, which was 1.73 and 5.00 times higher than those of Ag3PO4@ACB and Ag3PO4, respectively. N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB removed 69.67% TOC; this removal rate was 1.29 and 1.91 times higher than those of Ag3PO4@ACB and Ag3PO4, respectively. The environmental factors affecting NOR degradation were analyzed. After five cycles, the degradation rate of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB on NOR decreased by 10.08%; however, the structure did not change markedly. N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB effectively degraded NOR during wastewater treatment. The photocatalytic system was dominated by the oxidation of ·O2–, H+, and ·OH with the Z-scheme photogenerated carrier transfer mode. Moreover, the activation of graphitic N and the lone electron pairs of N and S promoted rapid photogenerated charge transfer. The surface properties (EPFRs and defects) of the ACB carrier promoted ROS generation, and the SPR effect of the Ag nanoparticles synergistically enhanced the photocatalytic activity of N,S-Ag3PO4@ACB. Furthermore, the degradation of NOR was recorded using 3D EEMs with three possible degradation pathways identified. The pathways were mainly associated with reactions such as replacement and elimination of F atoms, oxidative cleavage of the piperazine ring, decarboxylation and dealkylation, transformation of quinolone moieties, and ring opening. This study provides insights for the design of novel Ag-based composite photocatalysts with a Z-scheme and enriches the basic theory of the synergistic enhancement of photocatalytic mechanisms by N and S co-doping and biochar.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zainab, S. M., Junaid, M., Xu, N. & Malik, R. N. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistant genes (ARGs) in groundwater: a global review on dissemination, sources, interactions, environmental and human health risks. Water Res. 187, 116455 (2020).

Holmes, B., Brogden, R. & Richards, D. Norfloxacin: a review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use. Drugs 30, 482–513 (1985).

Bhatt, S. & Chatterjee, S. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics: occurrence, mode of action, resistance, environmental detection, and remediation-A comprehensive review. Environ. Pollut. 315, 120440 (2022).

Shurbaji, S., Huong, P. T. & Altahtamouni, T. M. Review on the visible light photocatalysis for the decomposition of ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, tetracyclines, and sulfonamides antibiotics in wastewater. Catalysts 11, 437 (2021).

Montañés, M. T. et al. Analysis of norfloxacin ecotoxicity and the relation with its degradation by means of electrochemical oxidation using different anodes. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 188, 109923 (2020).

Li, J. et al. Improving photocatalytic activity by construction of immobilized Z-scheme CdS/Au/TiO2 nanobelt photocatalyst for eliminating norfloxacin from water. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 586, 243–256 (2021).

Wang, T. et al. Efficient visible-light photocatalysis of chloramphenicol using novel engineered biochar-based Ti-doped Bi2WO6 composite: mechanisms, degradation pathways, and applications. Sep. Purif. Technol. 332, 125780 (2024).

Yi, Z. et al. An orthophosphate semiconductor with photooxidation properties under visible-light irradiation. Nat. Mater. 9, 559–564 (2010).

Wang, T. et al. Comparative study of enhanced adsorption-photodegradation activity using activated biochar composited with Ag3PO4 or Ag6Si2O7 in wastewater treatment and disinfection: effects and mechanisms. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 655, 130235 (2022).

Naciri, Y. et al. Photocatalytic oxidation of pollutants in gas-phase via Ag3PO4-based semiconductor photocatalysts: recent progress, new trends, and future perspectives. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 2339–2382 (2022).

Zhuang, H. et al. State-of-the-art progress in Ag3PO4-based photocatalysts: rational design, regulation and perspective. Appl Mater. Today 31, 101742 (2023).

Amirulsyafiee, A., Khan, M. M. & Harunsani, M. H. Ag3PO4 and Ag3PO4-based visible light active photocatalysts: Recent progress, synthesis, and photocatalytic applications. Catal. Commun. 172, 106556 (2022).

Wang, T. et al. Facile synthesis of activated biochar/BiVO4 heterojunction photocatalyst to enhance visible light efficient degradation for dye and antibiotics: applications and mechanisms. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 19, 5017–5036 (2022).

Sharma, G. et al. Remediation of antibiotics using coordination polymers. Coord. Chem. Rev. 519, 216120 (2024).

Wei, X. et al. Porous biochar supported Ag3PO4 photocatalyst for “two-in-one” synergistic adsorptive-photocatalytic removal of methylene blue under visible light irradiation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 106753 (2021).

Bu, X. et al. Fabrication of novel Z-scheme LaCoO3/activated biochar/Ag3PO4 heterojunctions for intensifying visible-light-catalytic degradation of bisphenol A. Appl. Surf. Sci. 588, 152887 (2022).

Ma, Y. et al. Fabrication of Ag3PO4/polyaniline-activated biochar photocatalyst for efficient triclosan degradation process and toxicity assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 821, 153453 (2022).

Talukdar, K. et al. Novel Z-scheme Ag3PO4/Fe3O4-activated biochar photocatalyst with enhanced visible-light catalytic performance toward degradation of bisphenol A. J. Hazard. Mater. 398, 123025 (2020).

Zhai, Y. et al. Novel biochar@ CoFe2O4/Ag3PO4 photocatalysts for highly efficient degradation of bisphenol a under visible-light irradiation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 560, 111–121 (2020).

Qian, Y. et al. Integration of biochar into Ag3PO4/α-Fe2O3 heterojunction for enhanced reactive oxygen species generation towards organic pollutants removal. Environ. Pollut. 303, 119131 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Application of silver phosphate-based photocatalysts: barriers and solutions. Chem. Eng. J. 366, 339–357 (2019).

Devi, L. G. & Kavitha, R. A review on non metal ion doped titania for the photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants under UV/solar light: Role of photogenerated charge carrier dynamics in enhancing the activity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 140, 559–587 (2013).

Wu, W. et al. Rational electron tunning of magnetic biochar via N, S co-doping for intense tetracycline degradation: Efficiency improvement and toxicity alleviation. Chem. Eng. J. 458, 141470 (2023).

Piątkowska, A., Janus, M., Szymański, K. & Mozia, S. C-, N-and S-doped TiO2 photocatalysts: a review. Catalysts 11, 144 (2021).

Mao, W. et al. Facile assembled N, S-codoped corn straw biochar loaded Bi2WO6 with the enhanced electron-rich feature for the efficient photocatalytic removal of ciprofloxacin and Cr (VI). Chemosphere 263, 127988 (2021).

Shabir, M. et al. Carbon nanotubes loaded N, S-codoped TiO2: Heterojunction assembly for enhanced integrated adsorptive-photocatalytic performance. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 105, 539–548 (2022).

Anfar, Z. et al. New functionalization approach synthesis of Sulfur doped, Nitrogen doped and Co-doped porous carbon: superior metal-free Carbocatalyst for the catalytic oxidation of aqueous organics pollutants. Chem. Eng. J. 405, 126660 (2021).

Tian, J. et al. Anion-exchange synthesis of Ag2S/Ag3PO4 core/shell composites with enhanced visible and NIR light photocatalytic performance and the photocatalytic mechanisms. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 209, 566–578 (2017).

Liang, C. et al. Boosting molecular oxygen activation ability in self-assembled plasmonic p-n semiconductor photocatalytic heterojunction of WO3/Ag@Ag2O. Chem. Eng. J. 372, 12–25 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Fabrication, application, and mechanism of metal and heteroatom co-doped biochar composites (MHBCs) for the removal of contaminants in water: a review. J. Hazard. Mater. 431, 128584 (2022).

Alshamsi, H. A., Beshkar, F., Amiri, O. & Salavati-Niasari, M. Porous hollow Ag/Ag2S/Ag3PO4 nanocomposites as highly efficient heterojunction photocatalysts for the removal of antibiotics under simulated sunlight irradiation. Chemosphere 274, 129765 (2021).

Cai, T. et al. A promising inorganic-organic Z-scheme photocatalyst Ag3PO4/PDI supermolecule with enhanced photoactivity and photostability for environmental remediation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 263, 118327 (2020).

Shi, E. et al. Ag2S-doped core-shell nanostructures of Fe3O4@Ag3PO4 ultrathin film: major role of hole in rapid degradation of pollutants under visible light irradiation. Chem. Eng. J. 366, 123–132 (2019).

Gao, Q., Xu, J., Wang, Z. & Zhu, Y. Enhanced visible photocatalytic oxidation activity of perylene diimide/g-C3N4 n-n heterojunction via π-π interaction and interfacial charge separation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 271, 118933 (2020).

Yuan, J., Wen, Y., Dionysiou, D. D., Sharma, V. K. & Ma, X. Biochar as a novel carbon-negative electron source and mediator: electron exchange capacity (EEC) and environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs): a review. Chem. Eng. J. 429, 132313 (2022).

Ma, P. et al. Assembly of Ag3PO4 nanoparticles on two-dimensional Ag2S sheets as visible-light-driven photocatalysts. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 3638–3643 (2016).

Martin, D. J. et al. Efficient visible driven photocatalyst, silver phosphate: performance, understanding and perspective. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 7808–7828 (2015).

Dong, Y., Su, Y., Hu, Y., Li, H. & Xie, W. Ag2S-CdS p-n nanojunction‐enhanced photocatalytic oxidation of alcohols to aldehydes. Small 16, 2001529 (2020).

Meng, S., Zhang, J., Chen, S., Zhang, S. & Huang, W. Perspective on construction of heterojunction photocatalysts and the complete utilization of photogenerated charge carriers. Appl. Surf. Sci. 476, 982–992 (2019).

Chen, M. & Chu, W. Photocatalytic degradation and decomposition mechanism of fluoroquinolones norfloxacin over bismuth tungstate: experiment and mathematic model. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 168, 175–182 (2015).

Shah, N. S. et al. Solar light driven degradation of norfloxacin using as-synthesized Bi3+ and Fe2+ co-doped ZnO with the addition of HSO5−: Toxicities and degradation pathways investigation. Chem. Eng. J. 351, 841–855 (2018).

Ding, D. et al. Mechanism insight of degradation of norfloxacin by magnetite nanoparticles activated persulfate: identification of radicals and degradation pathway. Chem. Eng. J. 308, 330–339 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the following grants, including the Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi Province (No. 2023-LL-QY-42, 2024NC-ZDCYL-02-05), the Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology Research Initiation Grant Program (No. 1960323102), the Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology Special Program for Cultivation of Frontier Interdisciplinary Fields (No. X20230079), and the Open Fund for the Key Laboratory of Soil and Plant Nutrition of Ningxia (No. ZHS202401). The authors also thank Shiyanjia Lab (www.shiyanjia.com) for the support of the specific surface area tests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to this study. Tongtong Wang: Methodology, Software, Conceptualization, Data curation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, and Writing-original draft. Amit Kumar and Gaurav Sharma: Writing-review & editing. Sen Wang and Junchao Jia: Validation and Investigation. Jiyong Zheng: Resources, Writing-review & editing. Hui Shi: Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition, and Writing-review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, T., Kumar, A., Sharma, G. et al. Synergistic mechanisms of novel Z-Scheme N,S co-doped biochar-based Ag3PO4 composites for efficient removal of norfloxacin. npj Clean Water 7, 97 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-024-00393-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-024-00393-8

This article is cited by

-

Efficient Removal of Phenol and Bisphenol A Complex Pollutants by Activated Carbon Sphere-Based Material: Adsorption Characteristics and Mechanisms

Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering (2025)