Abstract

Safeguarding the drinking water quality remains a challenge from the production site to the tap. Alternatively to chemical disinfection, biostable drinking water could serve as a more sustainable approach to produce microbially safe drinking water and to maintain the microbial quality in the drinking water distribution system (DWDS). In this study, the potential of hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria (HOB) to produce biostable drinking water was examined in a continuous trickling filter supplied with hydrogen gas. A biofilm was naturally enriched for 5 months and the bacterial regrowth, invasion potential, and nutrient composition of the water were determined. Treatment improved the biostability significantly, and it is hypothesized that nutrient limitation, especially phosphorous, was a driving force. As a result, the regrowth and invasion potential were lowered, as shown with specific biostability bioassays. Overall, this study demonstrates the proof-of-concept of HOB for producing biostable drinking water through nutrient limitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To avoid microbial regrowth in drinking water distribution systems (DWDS), residual disinfection is often applied as a last step in the production process. Most frequently, chlorine-derived compounds are added to eliminate microorganisms and maintain disinfection residual during distribution1. However, these disinfectants may form potentially harmful disinfection by-products (DBP) through the oxidation of organic compounds and can alter the water taste and/or odour2,3. Furthermore, when the disinfectant residual has reacted away, the nutrients from oxidized organic products and dead biomass provide a suited environment for uncontrolled microbial regrowth and may make the drinking water vulnerable to invasion of pathogens4,5,6.

Alternatively to chemical disinfection, the production of biostable water (i.e., biostability) could serve as a more sustainable approach to producing and maintaining microbially safe water. Here, the aim is to maintain a stable bacterial community in the water rather than removing as many bacteria as possible. Biostability is defined as “no” change in bacterial abundance and composition during distribution in absence of a disinfectant7,8. In terms of bacterial abundance, this means that the water is ideally produced with a total microbial load close to, but slightly below the carrying capacity of the ecosystem. Regarding the community composition, this implies that unwanted microorganisms (i.e., pathogens, indicator organisms) are not able to establish within the community.

Several drinking water utilities are already distributing drinking water without disinfection residual, for example in Switzerland, Germany, and The Netherlands9,10,11. Biostability is usually pursued by combining a final disinfection step without residual (e.g., membrane disinfection, UV, ozone, or a combination through AOP) with extensive biological treatment such as biologically activated carbon (BAC) or sand filters12. Focus is placed on nutrient limitation, often targeting organic carbon, to avoid regrowth during distribution13. However, it has been shown that other nutrients, such as phosphorous, may also be limiting microbial regrowth in drinking water14,15. An integrated approach, limiting all nutrients and steering the microbial community to produce microbially safe and biostable water would thus be more effective.

Hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria (HOB) form a phylogenetically diverse group of bacteria that can use hydrogen and oxygen as respective electron donor and acceptor to fix carbon dioxide16. Amongst others, aerobic HOB include species belonging to the genera Hydrogenophaga, Cupriavidus and Rhodobacter17,18,19. Most HOB are facultative autotrophs, meaning that they can also grow heterotrophically or mixotrophically, depending on the environmental conditions20,21. Their versatile metabolism is assumed to be an alternative mode of growth that may serve as a selective advantage in oligotrophic environments22. Due to their simple and versatile energy metabolism, HOB are found in many habitats and have been used in various applications, including nutrient removal through hydrogenotrophic denitrification in anoxic groundwater and phosphate removal from eutrophic surface water23,24. From a microbial resource management point of view, the environment (e.g., biological filters) can be steered to favour HOB using a hydrogen and oxygen supply as an energy source25. In the context of biostability, it is hypothesized that the biostability of drinking water will increase by HOB treatment through nutrient limitation to even lower levels, as they have their energy source readily available, and that HOB may steer the microbial community towards a more stable community, more resistant against invasion of unwanted species.

In this study, the potential of HOB to produce biostable water was evaluated. Through the recirculation of tap water in a trickling filter with hydrogen supply, a HOB-biofilm was enriched. Subsequently, in a continuous mode, (1) the composition of the biofilm was examined, (2) biological regrowth and invasion assays were performed on the in- and outgoing water to assess the effect of the trickling filter treatment on the biostability of the tap water, and (3) the nutrient composition was measured to determine the driving factors for biostability.

Methods

Trickling filter design and operation

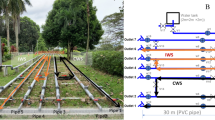

To support controlled biofilm growth of hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria (HOB) from tap water, a lab-scale bioreactor with hydrogen and oxygen supply was built (Fig. 1). Tap water without remaining chlorine residual and with fluctuating nutrient concentrations (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 1) was used as influent. The reactor was designed as a trickling filter in a PVC column (H = 1 m, Vtotal = 2 L) filled with Kaldnes K1 polyethylene carrier material (Vbed = 1.4 L, specific surface >900 m²/m³, AnoxKaldnes AB, Sweden) and was operated at 20 °C. Tap water was pumped (WM 530 s peristaltic pump, Watson Marlow, Belgium) over the carrier material via a custom-made trickling system with 16 tubes (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 2). Gas was added in excess and flowed bottom-up to create a counter current for optimal contact between liquid and gas.

The trickling filter was operated in three subsequent stages. During the first two stages, the filter was operated in batch mode (Q = 0.4 L min–1, empty bed contact time (EBCT) = Vbed/Q = 3.5 min) where water was recycled from a 10 L DURAN® glass Schott bottle, to rinse the tubing (Tygon® E-3603) and carriers. Demineralized water (8 L, Merck, Belgium) was recycled over the reactor and a recycling vessel for one week, during which the water was replaced every 2 days. In the second stage, biofilm formation on the carrier material was allowed through natural enrichment. During this stage, the recycling vessel was filled with tap water (8 L, Ghent, Belgium) and water was replaced every 2 days for one month. Hereafter, an excess hydrogen and oxygen supply (80 v% H2, 20 v% O2) was connected and tap water was recycled and refreshed every 2 days for one month. Then, the water was refreshed weekly for 5 months.

During the third stage, the reactor was switched to a continuous mode (Q = 0.7 L/h, EBCT = 2 h, 50 v% H2, 50 v% air, Vgas = 600 mL/h). To ensure sufficient gas flow, the total flow was increased after one month of continuous operation (Vgas = 6.3 L/h; 5 v% H2, 95 v% air). The reactor was operated in a steady state for 5 months, with alternating periods of switching the hydrogen supply off (1 × 1 day, 2 × 2 weeks) and back on. During this stage, experimental data was collected through the sampling of the liquid (in- and outlet) and biofilm in periods with and without hydrogen supply. The gas phase composition was checked regularly to confirm the presence of H2 at the in- and outlet (6.22 ± 0.83 v% H2, n = 4).

Analytical techniques

Liquid effluent samples were filtered using PA syringe filters of 0.22 µm pore size before analysis. Orthophosphate-P (o-PO43−-P) was measured using ion chromatography IC with a standard detection limit of 3.3 µg/L o-PO43−-P. When the measured concentrations were lower, manual peak determination was used to estimate the phosphate concentration (down to levels of 0.03 µg/L o-PO43−-P). Nitrate-N (NO3−-N) was measured using a 930 Compact IC Flex (Metrohm, Belgium), with chemical suppression and conductivity detector, equipped with a Metrosep A Supp 4/5 Guard/4.0 guard column and a Metrosep A Supp 5- 150/4.0 separation column. Trace elements were determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (Perkin Elmer 350D, Belgium) using 3.6 mL/min He collision gas and 10 µg/L Rh as internal standard. For total organic carbon (TOC) and assimilable organic carbon (AOC) analysis, 40 mL borosilicate glass vials with screw caps containing PTFE-faced liner were used (VWR, Belgium). Glassware was prepared according to Hammes and Egli26 to be free of any AOC that may interfere with the measurement. The TOC concentration was measured on the unfiltered samples using a Sievers 900 Portable TOC Analyzer (GE Analytical Instruments, Belgium) in technical quadruplicates. Before each measurement, a manual flush was performed and Milli-Q lab-grade water (Merck, Belgium) was used to check the performance. The AOC concentration was calculated using a flow cytometric assay as described by Hammes and Egli26. In short, the net cell regrowth (cells mL–1) after 72 h is calculated and divided by a theoretical conversion factor of 107 cells μg–1 AOC. The gas composition was analyzed with a Compact GC4.0 (Global Analyser Solutions, The Netherlands), equipped with a Molsieve 5 A pre-column and Porabond Q column (O2, H2, and N2) and an Rt-Q-bond pre-column and column (CO2) and a thermal conductivity detector for volumetric gas composition detection.

Microbial techniques

Total cell concentrations were measured using an AttuneTM NxT flow cytometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Belgium) with BRxx configuration, equipped with a blue (488 nm, 50 mW) and red laser (638 nm, 50 mW), seven fluorescence detectors with bandpass filters (BL1: 530/30 nm, BL2: 574/26 nm, BL3: 695/40 nm, BL4: 780/60 nm, RL1: 670/14 nm, RL2: 720/30 nm, RL3: 780/60 nm) and two scatter detectors on the 488 nm laser (FSC: 488/10 nm, SSC: 488/10 nm). The flow cytometer was operated with AttuneTM focusing fluid (Thermofisher Scientific, Belgium) as sheath fluid. Samples were stained with SYBR® Green I (SG, 100 x concentrate in 0.22 μm-filtered DMSO, Invitrogen, Belgium) and incubated for 20 min at 37 °C in the dark before analysis. Then, samples were analysed immediately in triplicate in fixed volume mode at a flow rate of 100 µL/min using acoustic-assisted hydrodynamic focusing. Quality control was performed daily using AttuneTM performance tracking beads (ThermoFisher Scientific, Belgium).

For 16S rRNA gene sequencing, 250 mL of water was collected in autoclaved glass bottles and filtered through 0.22 µm MCE filters (d = 47 mm, Merck, Belgium) and stored in sterile Petri dishes at –20 °C. For biofilm samples, two carriers were added to 2 mL sterile PBS and vortexed, centrifuged at 2500 × g for 3 min and vortexed again. Then, the carrier material was removed and the PBS with loosened biofilm was added to a DNase- and RNase-free sterile PP vial (Biosigma, Germany), centrifuged for 1 min at highest speed and supernatant was removed. For representative analyses, the biofilm samples were processed and sequenced in duplicate, and pellets were stored at –20 °C until extraction.

Before extraction, the filters were thawed for 15 min, cut (total area of ±2.73 cm³ per sample) with sterilized scissors and tweezers and added to DNase- and RNase-free sterile PP vials (Biosigma, Germany). Extraction was performed by first mixing the samples with lysis buffer, containing 100 mM Tris (pH 8), 100 mM EDTA (pH 8), 100 mM NaCl, 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP40) and 2% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS). 400 mg of 0.1 mm glass beads was added to the samples after which they were disrupted in a PowerLyzer (Qiagen, The Netherlands) in 5 × 15 s cycles at 4000 rpm with a 45 s hold. The samples were centrifuged at maximum speed for 5 min and the supernatant was added to a new tube containing 500 µL of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol 25:24:1 at pH 7. After mixing and subsequent centrifugation, the upper phase was added to a new tube containing 700 µl of chloroform. After mixing and centrifugation, 450 µL of the upper phase was added to a new tube containing 500 µL of cold isopropanol and 45 µL of 3 M sodium acetate. The samples were mixed and stored at –20 °C for one hour after which they were centrifuged at 4 °C for 30 min. The supernatant was removed, and the DNA pellet was dried before dissolving in 50 µL (filters, water samples) or 100 µL (pellets, biofilm samples) of 1 x TE. 10 µL was sent out to LGC genomics GmbH (Germany). Amplicon sequencing of the V3–V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was performed on an Illumina MiSeq platform with v3 chemistry, and the primers 341 F (5ʹ-CCT ACG GGN GGC WGC AG -3ʹ) and 785Rmod (5ʹ-GAC TAC HVG GGT ATC TAA KCC-3ʹ)27.

Bioassays for regrowth and invasion potential

To avoid carbon contamination, glasswork and pipette tips were rinsed thrice with sterile Milli-Q lab-grade water (Merck, Belgium) when performing the bioassays. The regrowth potential was assessed by taking duplicate samples (10 mL) in sterile borosilicate AOC-free vials (VWR, Belgium), prepared according to Hammes and Egli26. The vials were incubated at 28 °C and 100 rpm in the dark. Samples (200 µL) were taken during a period of six days (day 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6), as it is assumed that growth is completed after six days. The total cell concentration was quantified using flow cytometry. The regrowth potential was calculated relative to the starting concentration using the average cell concentration of technical replicates as described in the equation below.

The invasion potential was determined using a strain of the coliform Lelliottia amnigena isolated from a full-scale DWDS in Belgium as a model for unwanted microorganisms in drinking water. The strain was grown in R2A (3 g/L, 24 h at 28 °C and 100 rpm), washed thrice and transferred to a diluted R2A broth (50 mg/L, 24 h at 28 °C and 100 rpm). The culture was then washed thrice and the cell concentration was quantified using flow cytometry. Washing was performed by centrifuging (2500 × g, 5 min), removing supernatant and adding sterile isotonic NaCl (0.85%) to remove excess nutrients from the culture broth. The grown strain was then added to water samples (V = 2 L) in a final concentration of 50 cells mL–1. Samples were taken right before and after addition, and after 2, 4 and 6 h of incubation at 20 °C. The concentration of Lelliottia amnigena was determined by filtering (3 × 50 mL) and incubation (18–22 h, 37 °C) on coliforms chromogenic agar (CCA, Carl Roth, Belgium), according to the ISO 9308-1:2014 method for drinking water28.

Data analysis and statistics

Amplicon data was processed using the Mothur software package (v.1.44.3) and guidelines29,30. First, forward and reverse reads were assembled into contigs, after which sequences are screened based on their length (between 380 and 435 basepairs) and ambiguity of base calls (max = 0). Alignment was then performed to the Mothur-reconstructed SILVA SEED alignment, v. 138.1 for the 341 F and 785Rmod primers. After alignment-based quality filtering, sequences were pre-clustered (difference threshold = 4 base pairs) and chimeras were dereplicated and removed (VSEARCH v. 2.13.3). Classification was performed by assigning taxonomy using a naive Bayes classifier31, and SILVA v. 138.1, and contigs were clustered into OTUs at 97% sequence similarity (final sequence lengths between 381 and 432 basepairs). All sequences that were classified as Eukaryota, Archaea, Chloroplasts, Mitochondria and those that could not be classified were removed. For each OTU representative sequences were picked as the most abundant sequence within that OTU. Also, singletons (OTUs that were present in a sample in a total read count of 1 or less) were removed. Samples with final read counts below 9 000 (n = 2) were removed. This resulted in a data set of 35 samples with read counts between 9247 and 86 463 (median = 42 317). For biofilm samples, the sequencing data obtained by sequencing duplicate samples per sampling time was pooled before processing, as they had a similar microbial community composition (Supplementary Fig. 1).

The data was then imported in R (v. 4.2.0) and further processed using the Phyloseq package (v. 1.40.0). Differential analyses were performed using DESeq2 (v. 1.36.0) based on the Wald significance test and a parametric fit. After pre-processing and removal of singletons, the full OTU dataset was used for alpha- and beta diversity analyses.

Flow cytometric data were extracted as Flow Cytometry Standard (.fcs) files (v. 3.1) and was also processed in R (v. 4.2.0)32. FlowCore (v. 2.8.0) was used to import the .fcs files33. A gate was constructed manually and validated visually on the bivariate plot of green versus red fluorescence, bacterial cells were separated from background noise. Cell concentration quantification and fingerprinting was done using Phenoflow (v. 1.1.2) as described by Props et al.34. Before fingerprinting, FlowAI (v. 1.26.0) was used to check the data quality and to remove anomalous values in terms of flow rate stability, signal acquisition and dynamic range before fingerprinting35 and the data were resampled to the lowest sample size (n = 14,734 cells) to account for size-dependent differences.

Statistical analyses were performed in R (v. 4.2.0) (R Core Team 2020). All hypotheses were tested on the 5% significance level (α = 0.05). Significant differences between groups were checked using the non-parametric pairwise Wilcoxon rank sum test from the stats package (v. 4.2.0)36. On both the amplicon data and fingerprints, beta diversity was calculated using principal coordinates analysis (PcoA) based on the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, using vegan (v. 2.6.2)37. Significant differences in beta diversity were evaluated using PERMANOVA analysis (999 permutations) from the vegan package (v. 2.6.2). Correlations were evaluated using the non-parametric Spearman’s rank correlation test included in the stats package (v. 4.2.0).

Results

Bacterial community composition

The bacterial community composition of the water at the inlet, in the biofilm, and at the outlet of the trickling filter was determined to verify whether HOB were enriched within the trickling filter biofilm and to get insights into the factors that drive the community composition was done using 16S rRNA gene sequencing on samples that were regularly taken throughout the experimental period (5 months).

The beta diversity showed that the bacterial community in the biofilm was phylogenetically different from the bacterial community in the water (R2 = 0.21, p = 0.001) (Fig. 2A). The community changed over time at the in- and outlet and in the biofilm (arrows, Fig. 2A). The enriched biofilm community was stable and temporarily switching off the H2-supply did not show to have a significant effect on the composition of the community (blue ellipse, Fig. 2A). To average fluctuations over time, samples were pooled per sampling period, and the relative OTU abundances were calculated. Among others, OTUs belonging to the families Rhodocyclaceae, Rhodobacteraceae and Sphingomonadaceae were significantly enriched in the biofilm compared to the inlet water (Fig. 2B; Supplementary Fig. 4). The in- and outlet compositions were more similar (Fig. 2A), both harbouring OTUs belonging to the families Sphingomonadaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, Comamonadaceae and Caulobacteraceae (Fig. 2B).

A Beta diversity of the bacterial biofilm and water community composition profile, obtained through amplicon sequencing. Dots are connected for consecutive sampling dates throughout the experimental period. Confidence ellipses (α = 0.05) indicate the different components analysed. B Bacterial community composition of all samples merged per component (nin = 6, nbiofilm = 18, nout = 11), only including genera with abundances >2% for visualisation.

Trickling filter with HOB enriched biofilm lowers regrowth and invasion potential

To evaluate the effect on the drinking water biostability, the regrowth potential of the influent (tap water) and effluent of the trickling filter was quantified during periods with and without hydrogen (shut off for at least 2 weeks or 168 EBCT before sampling) supply. Due to fluctuations in the cell concentrations in the tap water influent (4.51 ± 1.32 × 105 cells mL–1, n = 12), the cell concentrations in the effluent fluctuated as well (4.46 ± 0.57 × 105 cells mL–1, n = 11) (Fig. 3). Therefore, regrowth was expressed relative to the starting concentration for each condition and period (Supplementary Fig. 3). In both conditions, the treatment showed to delay the regrowth potential of the indigenous water community. When hydrogen was supplied, the regrowth potential after 6 days was significantly lowered through treatment (p = 0.008), from 190.3 ± 98.4% in the influent to 74.8 ± 36.9% in the effluent. When switching off the hydrogen supply, the regrowth potential was lowered, but not significantly (p = 0.247), from 141.4 ± 67.8% in the influent to 64.7 ± 90.2% effluent (Supplementary Fig. 3). In general, treatment with hydrogen supply also seemed to result in more consistent reduction of the regrowth potential (Fig. 3).

The beta diversity of the flow cytometric fingerprints was used to evaluate phenotypic changes in the microbial community during the regrowth bioassay (Fig. 4). At the start, no difference between the two conditions (H2 versus no H2 supply) nor inlet versus outlet was observed. However, from day 2 on, treated water (outlet, with H2 supply) showed to be phenotypically different from the other in- and outgoing water samples (R2 = 0.15, p < 0.001). These differences were not reflected in the cell concentrations. For example, the cell concentration in the effluent at the end of the regrowth bioassay was not significantly different (p = 0.79) between the conditions with (7.14 ± 2.05 105 cells mL−1) and without (8.30 ± 4.78 105 cells mL–1) hydrogen supply (Fig. 3).

The second aspect of biostability includes the invasion potential of unwanted microorganisms. In this study, a bioassay using Lelliottia amnigena as a model organism was used to evaluate the performance of the trickling filter with hydrogen supply (Fig. 5). Lelliottia amnigena was selected as model organism as this is an (unwanted) aquatic coliform that is often found back in different drinking water networks, including the drinking water source used as source water for this reactor, and of which a drinking water isolate was available for the experiments. The experiment started with taking grab samples (2 L) at the in- and outlet of the reactor and addition of Lelliottia amnigena with an average initial concentration of 60.2 ± 30.4 CFU 100 mL–1, with no significant difference between the conditions (p = 0.83), after which the samples were incubated for 6 h. The results showed that, even though the concentration of Lelliottia amnigena decreased in both the treated and untreated water, the decrease was faster and resulted in lower final levels upon passing the trickling filter, with a significantly lower concentration in the effluent samples after 4 h (p4h = 0.03, p6h < 0.001).

Nutrient composition

The nutrient composition was quantified to evaluate whether nutrient removal could be a (part of the) underlying driver for biostability and if so, to define which nutrient(s) contributed most. The results showed that phosphorus was removed in the highest relative amounts compared to the influent concentrations (Fig. 6). Also, the removal of phosphorus was significantly larger during periods with hydrogen supply compared to periods without hydrogen supply (p = 0.009). Nitrate-nitrogen was only removed in a few percentages during periods with hydrogen supply, which was significantly different from periods without hydrogen supply (p < 0.001). Organic carbon (both total and assimilable organic carbon) showed inconsistent fluctuations between removal and addition through treatment in the trickling filter, and no significant differences between conditions were observed (pTOC = 0.47, pAOC = 0.81).

Discussion

This research aimed to study the ecology and functionality of a trickling filter system with hydrogen supply to produce biostable drinking water. Therefore, a biofilm was naturally enriched, and the bacterial community composition was evaluated using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Biostability parameters such as the bacterial regrowth, invasion potential and nutrient composition of the in- and outgoing water were also determined.

Beta diversity analysis showed that the biofilm community was phylogenetically different from the community in the water (Fig. 2A). In a trickling filter, the sludge retention time (SRT) is decoupled from the empty bed contact time (EBCT), which creates a different bacterial environment, and thus, may harbour phylogenetically different biofilm and planktonic bacterial communities. Among others, OTUs present in high relative abundances (>2%) in the biofilm belonged to the families Rhodocyclaceae, Rhodobacteraceae and Sphingomonadaceae (Fig. 2B). These have been previously detected in the biofilms of granulated active carbon (GAC) filters in drinking water treatment38,39. Also, several of these families have been previously identified in systems relying on bacterial hydrogen oxidation in different applications24,40,41.

Switching off the hydrogen supply (up to 2 weeks) showed to affect the effectiveness of the trickling filter (Figs. 3, 5), but did not affect the phylogenetic composition of the bacterial community in the biofilm (Fig. 2A). This indicates that the hydrogen supply was essential to maintain the functionality (i.e., producing biostable drinking water) of the trickling filter. Many bacteria, independently from their taxonomic classification, have been shown to have the capacity to oxidize hydrogen using hydrogenases, even at atmospheric trace concentrations42,43. More specifically, in oligotrophic environments, hydrogen has been suggested to be an important energy source for bacteria during periods of starvation, for example obligate heterotrophs are shown to be capable of upregulating the expression of hydrogenases during periods of starvation to use hydrogen for their maintenance metabolism44. Since the bacterial community composition did not change, even after 2 weeks without hydrogen supply, but rather evolved, it is hypothesized that HOB in the biofilm did not die off but rather switched their metabolism. Optimising the hydrogen and oxygen dosing, and a thorough understanding of the HOB-metabolism (e.g., hydrogenase functional gene expression) are necessary for controlled steering of the system towards a desired bacterial community in further practical applications.

The goal of the trickling filter with hydrogen supply was to produce biostable drinking water, instead of removing the bacteria. There was no significant difference between the concentrations at the inlet and the outlet of the trickling filter (Fig. 3). This was not surprising, as biological filters are known to not necessarily decrease the total bacterial abundance45. Bacterial numbers can even increase due to seeding from the biofilm46. Still, even at similar total bacterial abundances, differences in community and nutrient composition can alter the biostability of the water. Therefore, the biostability at the inlet and outlet of the trickling filter was quantified with bioassays for bacterial regrowth and invasion potential. Multiple approaches to determine regrowth potential have been developed, which makes it difficult to compare results between studies47. Here, to determine the regrowth potential, samples were incubated at 28 °C as an ideal growth temperature for drinking water bacteria to simulate a true “worst case” outgrowth without changing the water characteristics and its indigenous bacterial community. Overall, the net regrowth observed was within the same order of magnitude (an absolute increase of ± 5 ×105 cells mL−1) as the regrowth potential measured in DWDS samples48,49. Furthermore, the results showed that the bacterial regrowth potential was significantly lowered in the treated water with hydrogen supply (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 3). Also, the phenotypic fingerprint of the samples taken at the outlet of the trickling filter with hydrogen supply showed to be different from all other samples during the regrowth test (Fig. 4). These results indicate that the hydrogen treatment changed the water characteristics (e.g., nutrient concentration and composition). In turn, this has lowered the regrowth potential and changed the (phenotypic) behaviour of the bacterial community during regrowth, even though the bacterial community remained phylogenetically similar. This shows that taxonomic profiling of a bacterial community using 16S rRNA gene sequencing may not always be sufficient to explain changes in microbiome functionality50. More targeted and in-depth analyses (e.g., metabolomics, PICRUSt analysis) are necessary to understand the true mechanics, interactions, and metabolic functionality of the system.

The bacterial community showed a time-wise evolution during the 5-month sampling period, both in the biofilm and in the water (Fig. 2A). In DWDS, these seasonal changes linked to changes in water temperature and water quality have been observed frequently, especially when water is produced from surface water51,52,53. Here, time-wise changes in the incoming water were also reflected in the biofilm and outgoing water, even though the trickling filter was operated in a temperature-controlled room (20 °C). As seasonal changes are natural to the system, these are not considered as a part of biological instability48. Instead, they should be monitored and understood, so that these changes can be differentiated from calamities or true biological instability7.

With regard to the results from the invasion potential assay, the concentration of the model invader L. amnigena decreased in both the treated and untreated water (Fig. 5), as relevant starting concentrations compared to the legal requirement of absence in 100 mL54 were chosen to represent a serious calamity and to obtain reproducible results. Nevertheless, after 4 h, the invasion potential of the treated water was significantly lowered in the treated water. The success of invasion in drinking water has been shown to depend on the diversity of the indigenous bacterial community, where more diverse communities are more resistant to invasion55. Also, differences in nutrient concentrations may affect the establishment and growth of invading microorganisms14. In this study, the diversity (Inverse Simpson index) of the treated water was slightly higher, but not significantly different from the untreated water (Supplementary Fig. 6). On the other hand, nutrients (N, P) were removed during treatment, indicating that this may be a driving force for biostability.

To determine the underlying causes of biological (in)stability, the nutrient composition at the inlet and outlet of the trickling filter was measured during the continuous sampling period. During periods with hydrogen supply, both phosphorous and nitrate-nitrogen were significantly more removed (p < 0.01) than during periods without hydrogen supply, and in both cases, phosphorous was removed to the greatest extent (Fig. 6). This was also observed by Barbosa et al.23, who used a similar treatment on surface water. On the contrary, organic carbon (both TOC and AOC) and micronutrients were not significantly more removed during periods with hydrogen supply. These results indicate that phosphorous may be a limiting factor for bacterial regrowth in drinking water. Different studies have previously indicated this in drinking water14,56,57. When comparing the inlet elemental water composition (TOC (2.78 ± 0.72 mg L–1), NO3−-N (2.58 ± 0.12 mg L–1), PO43−-P (1.88 ± 2.85 µg L–1), molar C:N:P = 100:79.5:0.026) to the optimal molar C:N:P ratio of 100:10:1 for bacterial growth58,59, it was indeed confirmed that phosphate-P may be a limiting factor for bacterial growth.

The removal of nutrients is most likely linked to an increase in biomass concentration23, albeit limited by phosphorous, so increasing the specific surface area of the carrier material, (e.g., granular activated carbon (GAC)) and EBCT could improve the filter functionality42. Also, some HOB-species are known to accumulate phosphorous in the form of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) as a carbon- and energy storage mechanism, which could be (a part of) the underlying mechanism of the observed nutrient removal23,42. However, no correlation between phosphorous concentrations (or any nutrient in general) and the regrowth potential was found. This may be due to the low nutrient concentrations at the tap, which were found to be challenging regarding the detection limits of the measurement techniques and the variability of the tap water concentrations. Therefore, the regrowth and invasion bioassays are proposed as an added value to the measurement of nutrient concentrations, as integrated methods to evaluate the biostability of drinking water in a result-based way. Also, concerning application purposes, the trickling filter is most suited to be implemented as a treatment step during drinking water treatment as (1) nutrient concentrations will be higher than at the tap, (2) existing GAC or sand filters can be used and adjusted to work more efficiently38, (3) the setup can be built within a controlled industrial environment (e.g., safety of H2 dosing) and (4) working in a preventive way is preferred to remediation. Lastly, even though the results from this study prove the concept of HOB enrichment for biostability, further research of the practical feasibility (e.g., safety of H2 dosing and final water quality, and the costs and gains compared to current disinfection methods) should be performed before implementation.

In this study, we researched the potential of hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria (HOB) to produce biostable drinking water in a continuous trickling filter supplied with hydrogen gas. Our results showed that the treated water is more resistant towards the invasion of unwanted organisms and has a lower regrowth potential, and is thus, more biostable. Even though not all underlying mechanisms were elucidated, the hydrogen supply showed to be essential for the system’s functionality. Also, nutrient limitation with a focus on phosphorous was identified as a driving force for biostability. Overall, this study forms a proof-of-concept for future research on applying HOB to produce biostable drinking water, and more research is needed for further implementation and validation (e.g., extrapolation of the invasion protocol to other relevant microorganisms) of this system. A thorough metabolic understanding, combined with more research for optimised practical applications (e.g., design and optimisation of hydrogen dosing) will allow for a more targeted steering of the system that could potentially be applied at drinking water treatment plants.

Data availability

The flow cytometry dataset can be found on the FlowRepository database under accession ID FR-FCM-Z6KR. Sequencing data can be accessed in the NCBI SRA database (BioProject ID: PRJNA1135125). Other data can be made available upon request.

References

Sedlak, D. L. & von Gunten, U. The chlorine dilemma. Science 331, 42–43 (2011).

Li, X. F. & Mitch, W. A. Drinking water disinfection byproducts (DBPs) and human health effects: Multidisciplinary challenges and opportunities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 1681–1689 (2018).

Skjevrak, I., Lund, V., Ormerod, K., Due, A. & Herikstad, H. Biofilm in water pipelines; a potential source for off-flavours in the drinking water. Water Sci. Technol. 49, 211–217 (2004).

Bertelli, C. et al. Reduced chlorine in drinking water distribution systems impacts bacterial biodiversity in biofilms. Front Microbiol. 9, 2520 (2018).

Vital, M., Stucki, D., Egli, T. & Hammes, F. Evaluating the growth potential of pathogenic bacteria in water. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 76, 6477–6484 (2010).

Chatzigiannidou, I., Props, R. & Boon, N. Drinking water bacterial communities exhibit specific and selective necrotrophic growth. npj Clean Water 1, 22 (2018).

Favere, J. et al. Safeguarding the microbial water quality from source to tap. npj Clean Water 4, 28 (2021).

Rittman, B. & Snoeyinck, V. L. Achieving biologically stable drinking water. J. Am. Water Works Ass. 76, 106–110 (1984).

Hammes, F., Berger, C., Köster, O. & Egli, T. Assessing biological stability of drinking water without disinfectant residuals in a full-scale water supply system. J. Water Supply Res. T 59, 31–40 (2010).

Rosario-Ortiz, F., Rose, J. B., Speight, V., Von Gunten, U. & Schnoor, J. How do you like your tap water? Science 351, 912–914 (2016).

Hambsch, B. Distributing groundwater without a disinfectant residual. J. - Am. Water Works Assoc. 91, 81–85 (1999).

Sousi, M. et al. Multi-parametric assessment of biological stability of drinking water produced from groundwater: Reverse osmosis vs. conventional treatment. Water Res. 186, 116317 (2020).

van der Kooij, D. Biological stability: A multidimensional quality aspect of treated water. Water, Air Soil Pollut. 123, 25–34 (2000).

Van Nevel, S., De Roy, K. & Boon, N. Bacterial invasion potential in water is determined by nutrient availability and the indigenous community. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 85, 593–603 (2013).

Miettinen, I. T., Vartiainen, T. & Martikainen, P. J. Phosphorous and bacterial growth in drinking water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 63, 3242–3245 (1997).

Aragno, M. & Schlegel, H.-G. in The Prokaryotes: A Handbook on Habitats, Isolation, and Identification of Bacteria (eds M. P. Starr et al.) 865–893 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1981).

Xu, H.-W. & Wall, J. D. Clustering of genes necessary for hydrogen oxidation in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Bacteriol. 176, 2401–2405 (1991).

Yoon, K. S. et al. Isolation and characterization of a new facultatively autotrophic hydrogen-oxidizing Betaproteobacterium, Hydrogenophaga sp. AH-24. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 278, 94–100 (2008).

Sato, Y. et al. Occurrence of hydrogen-oxidizingRalstoniaspecies as primary microorganisms in the Mt. Pinatubo volcanic mudflow deposits. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 50, 855–861 (2011).

Lenz, O., Bernhard, M., Buhrke, T., Schwartz, E. & Friedrich, B. The hydrogen-sensing apparatus in Ralstonia eutropha. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4, 255–262, (2002).

Yu, J. Fixation of carbon dioxide by a hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium for value-added products. World J. Microbiol Biotechnol. 34, 89 (2018).

Madigan, M. T. & Martinko, J. M. Brock Biology of Microorganisms 11 edn, (Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006).

Barbosa, R. G. et al. Effective orthophosphate removal from surface water using hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria: Moving towards applicability. Sci. Total Environ. 800, 149648 (2021).

Eamrat, R. et al. Microbubble application to enhance hydrogenotrophic denitrification for groundwater treatment. Environ. Nat. Resour. J. 18, 156–165 (2020).

Verstraete, W. et al. Microbial resource management: The road to go for environmental biotechnology. Eng. Life Sci. 7, 117–126 (2007).

Hammes, F. & Egli, T. New method for assimilable organic carbon determination using flow-cytometric enumeration and a natural microbial consortium as inoculum. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39, 3289–3294 (2005).

Klindworth, A. et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e1 (2013).

VITO. EMIS Compendium voor de monsterneming, meting en analyse van water (WAC), https://emis.vito.be/nl/erkende-laboratoria/water-gop/compendium-wac (2020).

Kozich, J. J., Westcott, S. L., Baxter, N. T., Highlander, S. K. & Schloss, P. D. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 79, 5112–5120 (2013).

Schloss, P. D., Gevers, D. & Westcott, S. L. Reducing the effects of PCR amplification and sequencing artifacts on 16S rRNA-based studies. PLoS One 6, e27310 (2011).

Wang, Q., Garrity, G. M., Tiedje, J. M. & Cole, J. R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 5261–5267 (2007).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing., (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020).

Hahne, F. et al. flowCore: a Bioconductor package for high throughput flow cytometry. BMC Bioinforma. 10, 106 (2009).

Props, R. et al. Measuring the biodiversity of microbial communities by flow cytometry. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 1376–1385 (2016).

Monaco, G. et al. flowAI: automatic and interactive anomaly discerning tools for flow cytometry data. Bioinformatics 32, 2473–2480 (2016).

Noether, G. E. In Breakthroughs in Statistics: Methodology and Distribution (eds S. Kotz & N. L. Johnson) 191-195 (Springer New York, 1992).

Oksanen, J. et al. Vegan: community ecology package. R package version 2.5-4, https://cran.ism.ac.jp/web/packages/vegan/vegan.pdf (2019).

Lu, Z. et al. Can we shape microbial communities to enhance biological activated carbon filter performance? Water Res. 212, 118104 (2022).

Pinto, A. J., Xi, C. & Raskin, L. Bacterial community structure in the drinking water microbiome is governed by filtration processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 8851–8859, (2012).

Barbosa, R. G., Sleutels, T., Verstraete, W. & Boon, N. Hydrogen oxidizing bacteria are capable of removing orthophosphate to ultra-low concentrations in a fed batch reactor configuration. Bioresour. Technol. 311, 123494 (2020).

Matassa, S., Verstraete, W., Pikaar, I. & Boon, N. Autotrophic nitrogen assimilation and carbon capture for microbial protein production by a novel enrichment of hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria. Water Res. 101, 137–146 (2016).

Lin, L., Huang, H., Zhang, X., Dong, L. & Chen, Y. Hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria and their applications in resource recovery and pollutant removal. Sci. Total Environ. 835, 155559 (2022).

Greening, C. & Grinter, R. Microbial oxidation of atmospheric trace gases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 513–528 (2022).

Greening, C., Islam, Z. F. & Bay, S. K. Hydrogen is a major lifeline for aerobic bacteria. Trends Microbiol 30, 330–337 (2022).

Wang, H., Pryor, M. A., Edwards, M. A., Falkinham, J. O. 3rd & Pruden, A. Effect of GAC pre-treatment and disinfectant on microbial community structure and opportunistic pathogen occurrence. Water Res. 47, 5760–5772 (2013).

Velten, S. et al. Development of biomass in a drinking water granular active carbon (GAC) filter. Water Res. 45, 6347–6354 (2011).

Sousi, M. et al. Measuring bacterial growth potential of ultra-low nutrient drinking water produced by reverse osmosis: Effect of sample pre-treatment and bacterial inoculum. Front Microbiol 11, 791 (2020).

Nescerecka, A., Juhna, T. & Hammes, F. Identifying the underlying causes of biological instability in a full-scale drinking water supply system. Water Res. 135, 11–21 (2018).

Prest, E. I., Hammes, F., Kötzsch, S., van Loosdrecht, M. C. M. & Vrouwenvelder, J. S. A systematic approach for the assessment of bacterial growth-controlling factors linked to biological stability of drinking water in distribution systems. Water Supply 16, 865–880 (2016).

De Vrieze, J. & Verstraete, W. Perspectives for microbial community composition in anaerobic digestion: from abundance and activity to connectivity. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 2797–2809 (2016).

Favere, J., Buysschaert, B., Boon, N. & De Gusseme, B. Online microbial fingerprinting for quality management of drinking water: Full-scale event detection. Water Res. 170, 115353 (2020).

Pinto, A. J., Schroeder, J., Lunn, M., Sloan, W. & Raskin, L. Spatial-temporal survey and occupancy-abundance modeling to predict bacterial community dynamics in the drinking water microbiome. MBio. 5, e01135–01114 (2014).

Ouyang, Y., Nkedi-Kizza, P., Wu, Q. T., Shinde, D. & Huang, C. H. Assessment of seasonal variations in surface water quality. Water Res. 40, 3800–3810 (2006).

Flemish Government. Besluit van de Vlaamse regering houdende reglementering inzake de kwaliteit en levering van water, bestemd voor menselijke consumptie. Belgisch Staatsblad, 2907-2923, (2002).

De Roy, K. et al. Environmental conditions and community evenness determine the outcome of biological invasion. Nat. Commun. 4, 1383 (2013).

Vrouwenvelder, J. S. et al. Phosphate limitation to control biofouling. Water Res. 44, 3454–3466 (2010).

Buysschaert, B. et al. Flow cytometric fingerprinting to assess the microbial community response to changing water quality and additives. Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol. 5, 1672–1682 (2019).

Chrzanowski, T. H. & Kyle, M. Ratios of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus in Pseudomonas fluorescens as a model for bacterial element ratios and nutrient regeneration. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 10, 115–122 (1996).

Ruberto, L., Vazquez, S. C. & Mac Cormack, W. P. Effectiveness of the natural bacterial flora, biostimulation and bioaugmentation on the bioremediation of a hydrocarbon contaminated Antarctic soil. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 52, 115–125 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the FWO Flanders [grant number 3S85419] and the FWO-SBO “Biostable” project [grant number S006221N]. The work is part of the “Ghent University-Aquaflanders Chair for Sustainable Drinking Water”, which is supported by Aquaflanders, the federation of Flemish companies responsible for drinking water and sewer management (www.aquaflanders.be). We would like to thank Kristin Van Hecke and Kris Mannens for the IC analyses, Tim Lacoere for the artwork, and Pieter Ostermeyer and Badri Narayan Ravikumar for their help in the lab.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: J.F., F.W., M.J., K.F., A.R., B.D.G. and N.B. Funding acquisition: J.F., A.R., B.D.G. and N.B. Lab work: J.F., F.W., M.J., K.F., M.V. and E.B. Writing—original draft: J.F. Writing—review and editing: J.F., F.W., M.J., K.F., M.V., E.B., A.R., B.D.G. and N.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Favere, J., Waegenaar, F., Jia, M. et al. Production of biostable drinking water using a lab-scale biological trickling filter enriched with hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria. npj Clean Water 7, 101 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-024-00396-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-024-00396-5