Abstract

Existing strategies for improving global access to safe drinking water have met only limited success. We consider an unglamorous and often neglected dimension of drinking water infrastructure provision: cleaning. We randomly assigned caretakers of community wells to participate in a training workshop about how to clean wells. Thirteen to seventeen months later, wells with caretakers assigned to receive training have negligible rates of contamination with Escherichia coli (13 months: 2%; 17 months: 4%), while control wells have substantial rates of E. coli contamination (13 months: 14%; 17 months: 19%). Rates of contamination with any coliform bacteria are almost halved (13 months: control 55%, treated 30%; 17 months: control 77%, treated 46%). We estimate the cost of preventing exposure to coliform bacteria in drinking water to be US$0.89 per person and that, if scaled up, each US$2376 spent on the intervention could avoid the death of a child.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A quarter of the world’s population lacks reliable access to safe drinking water1, contributing to an annual global burden of 1.4 million deaths and 74 million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) lost due to inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH)2. Improving access to safe drinking water can seem like an intractable problem: the current rate of progress needs to quadruple globally and increase by a factor of 23 in fragile contexts to meet the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of universal access to safely managed drinking water by 20301. In Bangladesh, the context for this study, the rate of progress needs to increase by at least a factor of ten from an average of 0.4 percentage points a year between 2015 and 2020 to 4.1 percentage points a year between 2020 and 2030 to meet the SDG target3.

An important obstacle to progress is drinking water quality1. Both worldwide and in Bangladesh, it is specifically water quality that holds back progress on achieving the SDG target4,5. Adopting “improved” infrastructure that is in principle less likely to be contaminated does not in practice ensure drinking water quality6. In 2020, about 1.2 billion people were collecting contaminated water for their households despite using an improved source1,3. In Bangladesh, 86% of households obtain drinking water from tubewells, classified as improved sources, but fecal bacteria are commonly present in these tubewells7.

How to increase the rate of progress remains unclear. Further improvements to physical infrastructure are costly and may not eliminate exposure to fecal contamination1,3. Maintenance also remains a perpetual and unresolved challenge8,9. While point-of-use and point-of-supply chlorination have shown considerable promise10,11, these interventions require constant resupply to continue delivering benefits.

One potential—albeit unglamorous—channel to improve water quality in existing infrastructure is to improve cleaning practices. In Bangladesh, fecal bacteria are present in tubewells even when the wells draw water from deep aquifers that are isolated from surface sources of contamination12,13,14, and even when competent and experienced contractors have installed the wells15,16. Evidence suggests that users introduce microbial contamination via the tubewell mouth, which then accumulates in the tubewell body as a biofilm17,18,19. If this is indeed an important channel for contamination, improving cleaning practices might be a low-cost way to improve water quality.

Cleaning practices have, however, received very scant attention in previous literature. Policy recommendations have primarily focused on how to remediate wells in emergencies20. A few studies quantify improvements to drinking water quality when staff from external organizations clean wells19,21,22. Most salient to our context—tubewells installed for community use in rural Bangladesh—a pilot study in the same area showed that scrubbing and rinsing interior surfaces with a weak, low-cost chlorine solution improved water quality, when trained staff cleaned the wells16. The same study showed that when well caretakers cleaned the wells, their standard practice was to limit their attention to the well’s external surfaces and the well platform, with no consequent improvement in water quality16. Whether well caretakers—who are unpaid and face many competing demands on their time and attention—could or would adopt a more effective approach was unknown.

We use a randomized experiment to evaluate whether community well water quality improves after well caretakers receive training in how to more effectively clean wells. Randomizing the offer of training allows us to estimate the causal effect of training23,24. Randomization ensures that wells with caretakers that are offered training are observationally equivalent to wells in the control group, whose caretakers are not offered training. This would not be the case if, for example, we had simply offered training to caretakers on a voluntary basis and compared water quality in wells whose caretakers opted in and wells whose caretakers opted out. Caretakers who opted in to training might differ in a host of other respects that could also affect water quality in the wells they look after, biasing comparisons between the two groups. Comparing how contamination evolves in wells whose caretakers were and were not offered training also allows us to separate the impacts of the intervention from changes in contamination that occur naturally over time, for example, in response to changes in weather.

Thirteen to seventeen months after the training workshops, wells with caretakers assigned to receive training were almost free of contamination with Escherichia coli. The rate of contamination with any coliform bacteria was almost halved, compared with control wells whose caretakers received no training. The cost of preventing exposure to coliform bacteria in drinking water was about US$0.89 per person. Modeling the potential reduction in child mortality, we calculate that each US$2,376 spent on the intervention would save one child’s life, equivalent to one DALY saved per US$29 spent, ranking this among the most cost-effective interventions in improving infant health25.

Results

The training intervention

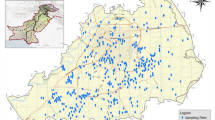

The intervention we evaluate is a single two and half hour training workshop delivered to the caretakers of community wells in December 2021 (Fig. 1). The wells were installed between 2015 and 2017 in communities of 50 to 250 households in North-Eastern Bangladesh (Fig. 2), as part of several previous research projects15,26,27.

The study wells are deep tubewells that draw water from aquifers approximately 100 to 250 m underground. These relatively deep aquifers are isolated from surface sources of fecal contamination. For the vast majority of the study wells, communities chose where to install the wells by consensus at a meeting with representation requirements for women and the poor27, an approach shown previously to increase impact in similar contexts28. Field staff ensured that all wells were installed on adequately-drained sites at sufficient distance from potential sources of contamination, such as pit latrines.

Each well had one male and one female caretaker, selected by consensus at a meeting of self-identified well users after installation. Compared to other households in their communities, households with caretakers had worse water quality before the intervention (Supplementary Fig. 1), reflecting how communities located wells in parts of the communities with lower access to safe drinking water27 and that caretakers typically lived closer to the installed wells (Supplementary Fig. 2). The selected caretakers live in households that are also wealthier, better educated, and more socially connected and influential than other households living in the same communities (Supplementary Fig. 1).

The training intervention was delivered by a partner NGO, NGO Forum for Public Health, which also implemented the well installation projects in the same communities. Trained facilitators led each workshop. Each workshop began with a general overview of WASH best practices before a physical demonstration of how to clean a tubewell effectively. Facilitators demonstrated how to dismantle the well, scrub the exterior and accessible interior surfaces of the pump, and rinse all surfaces with a weak chlorine solution. Facilitators emphasized the importance of removing all deposits that could potentially harbor bacteria and of pumping the well for 10 min after reinstallation to remove residual chlorine from the tubewell body. Facilitators also explained results from a pilot study that showed that local cleaning practices did not improve water quality but that the approach taught during the workshop was effective16. Caretakers received a packed lunch and reimbursement for travel expenses after the workshop, though they were not informed of this in advance. Half the caretakers of wells assigned to receive training were also assigned to receive a year of supplies necessary to implement the cleaning protocols as taught in the workshop.

Field staff invited caretakers to attend a scheduled training workshop by phone 1 week in advance, visiting caretakers in person if they could not be reached by phone. Field staff also reminded caretakers about the workshop by phone the day before the workshop. Among caretakers assigned to training only, field staff recorded that 83% attended a workshop. Among caretakers assigned to training and supplies, this figure was 93%. Caretakers later evaluated the training workshop positively, listing similar strengths whether assigned to receive training alone or training and supplies (Supplementary Fig. 3). Comprehensive accounts show that the intervention cost US$20.5 per well for training alone and US$22.9 per well for training and supplies, including the costs of inviting participants and other overheads (Supplementary Table 1).

Improvements to microbial water quality

Water quality tests show that 13–17 months after training, rates of contamination with E. coli and total coliform bacteria are substantially lower in wells for which caretakers received training than in a control group of wells whose caretakers were not offered training (Fig. 3). Thirteen months after training, in January 2023, the share of wells that tested positive for E. coli was 2% in treated wells compared to 14% in control wells, and the share of wells that tested positive for any coliform bacteria was 30% compared to 55% in control wells. Ambient temperatures in January 2023 were low (daytime average range 10.6 °C to 23.9 °C), below the temperatures at which coliform bacteria thrive. Four months later, in May 2023 (daytime average range 24.4 °C to 33.7 °C), the share of control wells testing positive for E. coli and for coliform bacteria had risen to 19% and 77%, but in treated wells, these shares were only 4% and 46%, respectively. The comparisons between the control wells and the wells with caretakers that received training are statistically significant in all cases. Taken together, the evidence suggests that the training intervention almost eliminated the risk of exposure to E. coli and almost halved the risk of exposure to any coliform bacteria.

a–d show share of wells contaminated with E. coli and coliform bacteria 13 and 17 months after training, respectively. 90% confidence intervals and p values obtained from a regression of a dummy variable for contaminant presence on treatment arm indicators. Standard errors are robust. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

When bacteria were present, they were present at lower concentrations. In May 2023, 17 months after training and when mean levels of contamination were highest, almost all the wells that tested positive for E. coli in the control group (4/5) had concentrations above 10 CFU/100 ml, while no well in the training group had an E. coli concentration above 10 CFU/100 ml. Among wells that tested positive for coliform bacteria in the control group, 40% had concentrations above 100 CFU/100 ml, including three at the upper detectability limit of 2419.6 CFU/100 ml, while none of the wells in the training group exceeded 100 CFU/100 ml. The comparison between treated and control wells is similar when we analyze concentrations of E. coli and total coliform bacteria, using an arcsinh transformation to deal with the skewed distribution of concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Providing supplies alongside training appeared no more effective in improving water quality than providing training alone. Across eight comparisons of presence and concentration of E. coli and total coliform bacteria, 13 and 17 months after training, training and supplies in fact performed worse than training alone in most (6/8) comparisons. However, across all 8 comparisons, we never statistically reject the null hypothesis of equal contamination in wells assigned to training alone or training combined with supplies.

One might speculate that training caretakers to better clean wells could also affect other dimensions of well performance. All the above results apply to the sample of wells that were still functional at the time of data collection. Between baseline data collection and the second round of water quality testing in May 2023, a total of eleven wells ceased to function (Fig. 2): six control wells, four wells assigned to training and supplies, and one well assigned to training alone. Differences in failure rates are only statistically significant (α = 0.1) for the pairwise comparison between the control group and the group assigned to training alone (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Although these differences might suggest that improved cleaning practice also increased well functionality, we did not adjust for multiple hypothesis testing and it is possible that the differences arose due to chance.

Recall of and adherence to the cleaning protocol

Thirteen months after training, caretakers assigned to received training were much more likely to correctly name the three elements of the recommended cleaning process than caretakers of the control wells: cleaning the accessible parts of the well with a stiff brush, scrubbing the accessible parts with chlorine solution, and washing interior surfaces with the chlorine solution (Fig. 4). The differences between groups attenuated slightly over time, with some spillover of knowledge to the control group and some fading of recall among the treated groups after 17 months. The share of caretakers reporting that they regularly practiced elements of the cleaning process was lower than the share recalling the elements.

a–d show share of caretakers reporting knowledge of and regular practice of the labeled elements of the cleaning protocol, 13 and 17 months after training. 90% confidence intervals obtained from a regression of a dummy variable for knowledge or practice on treatment arm indicators. Weights applied so that each well counts equally. Standard errors clustered by well.

Caretakers that were also assigned to receive supplies had better recall and were more likely to report regularly practicing elements of the cleaning process, compared to caretakers assigned to training alone. Thirteen months after training, caretakers assigned to training and supplies recalled on average 2.0 of three elements, while caretakers assigned to training alone recalled only 1.0. Caretakers assigned to training and supplies reported regularly practicing 1.6, compared to 0.6 among caretakers assigned to training alone. Four months later, caretakers assigned to training and supplies recalled 1.6 and regularly practiced 0.7, and caretakers assigned to training alone recalled 0.6 and regularly practiced on average 0.3. The differences between caretakers assigned to receive supplies and those assigned to training alone are larger for the elements of the process that required use of the chlorine solution.

The decline in regular practice between 13 and 17 months is particularly sharp for the elements that require use of the chlorine solution among the caretakers assigned to training and supplies. This may reflect the exhaustion of the supplies provided to caretakers. At 17 months, caretakers for only seven wells had bleach powder in stock, five of whom were assigned to receive supplies as well as training. Caretakers for only two wells reported having bought bleach powder themselves, even though the dose required to clean a well costs only 0.04US$16, and the majority of caretakers reported that it was easy or very easy to obtain bleach powder locally. At 13 months, those who recalled an element of good practice but did not regularly practice it mostly cited a lack of time as the main obstacle, while at 17 months, those who recalled but did not practice elements related to use of the weak chlorine solution cited lack of resources.

The results suggest that even moderate changes in cleaning behavior can effectively improve drinking water quality, because we observe substantial changes in water quality even though not all caretakers exactly followed the cleaning protocol. Moreover, water quality improved equally in wells whose caretakers were assigned to training alone and wells whose caretakers were assigned to receive supplies as well, despite the differences in recall and practice between the groups. An alternative hypothetical explanation for the results is that caretakers could have restricted access to the wells to reduce opportunities for contamination29. Treated wells are reported to have slightly fewer users 13 months after training but a slightly greater number of users 17 months after training, and none of the differences in user numbers are statistically significant, suggesting that this alternative explanation does not hold (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). More awareness of cleanliness could, however, have changed caretaker’s behavior in other ways we did not measure, for example, by encouraging users to avoid introducing contamination into the wells when collecting water.

Discussion

This paper shows that training caretakers of community wells to clean wells more effectively close to eliminates contamination with E. coli and approximately halves rates of contamination with any coliform bacteria. Providing caretakers with cleaning supplies along with training was no more effective in improving water quality than training alone, although it did improve recall of and adherence to the cleaning protocol. The cost of preventing exposure to coliform bacteria in drinking water was about US$0.89 per person.

Improving safe drinking water is ultimately an investment in improving health. To compare the cost-effectiveness of the training intervention to other health investments, we model the potential health consequences of the observed improvement in water quality using meta-analytic estimates that account for all the potential causal pathways between water quality and mortality30. We estimate that if the intervention were successfully scaled, it would avoid the death of one child for every 104 wells whose caretakers were trained, at a cost per life saved of US$2376 and per disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) gained of US$29 at current prices and exchange rates, or $21 in 2010 International Dollars (as used in the WHO-CHOICE program to evaluate cost-effectiveness).

Our cost-effectiveness estimates are conservative for several reasons. We focus only on mortality effects, thus disregarding any additional reduction in the disease burden. In Bangladesh, estimates of the health burden in DALYs of diarrheal disease—closely linked with unsafe drinking water—are 60% higher when they incorporate long-run health effects, compared to estimates that focus only on acute effects, which primarily reflect mortality31,32. We also assume that mortality benefits only accrue to children under five and to well users who entirely avoid exposure to coliform bacteria, thus disregarding the substantial reductions in concentrations of bacteria. We also assume that effects start to decay immediately after the 17 months over which we directly observe effects. However, the persistence of behavioral changes and impacts on water quality 17 months after the training intervention gives cause for optimism that effects might persist over longer time frames, a potential avenue for future research.

The estimated cost per DALY averted is around 1% of GDP per capita, the threshold long used by the WHO to identify highly cost-effective interventions33, and less than 10% of a more conservative opportunity cost-based willingness-to-pay threshold34,35. This cost per DALY renders the intervention comparable to some of the most apparently cost-effective interventions in infant, child, and maternal health25. The estimate is similar to the cost-effectiveness of water treatment with chlorine tablets30, with the important caveat that water treatment with chlorine tablets requires ongoing resupply, whereas the training intervention has the potential for persistent effects on water quality even without further interventions.

The costs of implementing the training intervention at scale would likely differ from those incurred at the relatively small scale of this study. Training could be conducted closer to caretakers’ homes, reducing venue and travel costs. In general, the costs of implementing an intervention fall when programs are scaled up because of economies of scale36.

Our study has several limitations. We did not measure the health consequences of the training intervention directly: we did not have sufficient funds to survey user households, nor would we expect to have the necessary sample size to detect effects on health or mortality30. Also, the wells we study were professionally installed deep tubewells with limited alternative channels for contamination, intended for community use, and the caretakers who received training were from relatively wealthy and educated households. Community wells such as those in this study are of particular interest because more than half of rural households worldwide depend on them as a source of drinking water37. However, the intervention might be more or less effective in shallower wells, wells that were not professionally installed, wells used by fewer households, or with a different population of trainees. As with many non-medical experiments, neither participants or field staff were blind to treatment status, although our main outcome variables—water quality tests—are analyzed anonymously and unlikely to be susceptible to placebo effects.

A final limitation is that the experimental study design only allows us to causally evaluate whether or not the intervention was effective as implemented. We can only provide suggestive evidence about how and why the intervention worked. Training interventions have been studied in many fields and disciplines, and evidence is mixed on whether and under which circumstances they are effective38,39,40. Three features of the intervention we study might help explain its success. First, the training was provided by an NGO with a multi-year presence in the study area, meaning that the caretakers had an established and trusting relationship with the training providers. Second, the training was based on an experimental pilot study, allowing facilitators to draw on concrete data about the effectiveness of the recommended approach compared to standard practice. Third, the training incorporated a practical demonstration, clarifying the steps involved in a concrete way.

Training caretakers to clean community wells improved water quality even though caretakers did not adhere to all the recommended elements of the cleaning protocol. We interpret this pattern of results as suggesting that even moderate behavior change on the part of well caretakers can lead to substantial improvements in water quality. An avenue for future research is to further refine cleaning protocols to maximize the impact on water quality while remaining mindful of time and financial costs for well caretakers, who are typically uncompensated for their efforts, for example by investigating how frequently caretakers need to clean wells or which elements of the cleaning protocol are critical.

The most generalizable conclusion we draw is that cleaning has been greatly neglected as a channel for meeting the Sustainable Development Goal of universal access to safely managed drinking water, with the potential to close the gap between coverage of improved and safely managed sources of drinking water. We hope this study paves the way for future research and policy action to realize this potential.

Methods

Sample of wells

The study sample originally consisted of 94 deep tubewells, constructed between 2015 and 2017 in Bogra and Gaibandha districts during three prior research projects15,26,27. The inclusion criterion was that wells were still functional in mid-2021 during a round of baseline data collection and a pilot study16. We define functionality as being able to produce at least 7 litres of water, the volume of a kolci, a standard vessel locally used to collect and carry water.

Experimental design

We assigned each of the 94 wells to one of three study arms: 32 to a control group that received no intervention, and 31 to each of two treatment arms, which we designated “Training” and “Training and supplies”. We used a list randomization approach to create random samples that were both geographically balanced (Fig. 2) and balanced with respect to cleaning processes implemented during the pilot study in 2021. We sorted the wells by: (1) the cleaning protocol to which they were assigned during the pilot study in 2021; (2) by union, the smallest local administrative unit, in random order; and iii) within union, in random order. To generate the random ordering, we used pseudo-random number generators in Stata with a seed of 479995728. We in turn randomly generated this seed in Microsoft Excel using a uniform distribution over all possible seed values accepted by Stata (0 to 231 − 1). We then assigned the thus randomly sorted wells sequentially to the control group and the two treated groups. Regression analyses confirm that wells in the control group and both treatment arms were statistically comparable with respect to presence and concentration of E. coli and total coliforms in 2021, that is, before the pilot cleaning experiment and before the training workshop (Supplementary Table 6a, b). We also confirm that whether and how the wells were cleaned in 2021 had no persistent effects on water quality in 2023 (Supplementary Table 7).

Interventions

Field staff invited caretakers of wells assigned to either of the two treatment arms to participate in a training workshop. Additionally, field staff provided caretakers of wells assigned to “Training and supplies” with supplies sufficient for a year of cleaning, specifically, a stiff brush and 12 4g doses of chlorine powder, pre-weighed in Ziploc bags. For each treatment arm, field staff organized two workshops, for a total of four workshops. We invited the caretakers of half the wells assigned to each treatment arm to each workshop. Caretakers only attended training workshops with other caretakers assigned to the same treatment arm.

Compliance

Field staff recorded that 83% of caretakers of wells assigned to training only attended a workshop and that 93% of caretakers of wells assigned to training and supplies attended a workshop. Project attendance records were highly consistent with what caretakers later reported retrospectively about workshop attendance in surveys (Supplementary Fig. 5). Among 104 caretakers asked if they attended training, survey responses were consistent with recorded attendance in 100 cases. Three respondents said they attended when our records said they did not, all assigned to training and supplies. One respondent, assigned to training only, said that they did not know if they attended when our records said they did.

Attrition

We can only test water quality in functional wells, i.e., wells that produce a sufficient volume of water to obtain a sample for testing. Between collecting the baseline functionality data we use to determine eligibility for this study (June and July 2021) and the first endline data collection (January 2023), five wells ceased to function: 3 in the control group and 2 assigned to training and supplies. Between the two endline data collection periods (January and May 2023), a further 6 wells ceased to function: 3 more in the control group, 2 more assigned to training and supplies, and 1 well assigned to training only. Of four potential pairwise comparisons between treatment arms and the control group, we reject only the null hypothesis that functionality rates are equal between the control group and the group assigned to treatment only. We reject this null hypothesis at the 10% level in both January and May 2023 (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). If the four tests at a given date were independent, and all null hypotheses of no difference in failure rates were true, we would expect at least one of the four tests to reject the null hypothesis at the naïve 10% level 34% of the time (1–0.94). There is therefore a relatively high likelihood that the observed differences across treatment arms occur due to chance.

Survey data

At each round of data collection, enumerators attempted to locate and interview caretakers for all wells. Enumerators interviewed caretakers jointly about the condition of the well and recent maintenance activities and individually about their knowledge about the recommended cleaning practices, their own cleaning practices, and (in the first endline only) their experiences with the training program. In January 2023, enumerators successfully interviewed caretakers from all functioning wells. Three wells only had one caretaker at this time; enumerators interviewed both caretakers at all remaining wells. However, we later lost survey data from the caretakers at two wells—one from each training treatment arm—because the enumerators did not correctly upload the completed surveys to the server. A coding error in the form also meant that we incorrectly assigned some questions to caretakers. In May 2023, we successfully surveyed all active caretakers from all functioning wells; six wells only had one caretaker at this time. No data were lost, and no survey coding errors were detected. All interviews were carried out in Bangla. We interviewed the caretakers in their role as well caretakers, and the interviews covered no private or sensitive information.

Water quality testing

At each round of data collection, field staff collected one 100 ml sample of water from each well for testing. Field staff did not pump or clean the well before collecting the sample, so that the sample was representative of normal contamination levels in drinking water collected from the well. The sample vessels contained sodium thiosulfate to neutralize any potential residual chlorine and were sealed with tamper-evident shrink bands. Field staff stored sample vessels in a clean icebox between collection and processing, usually for less than 5 h. We used IDEXX Colilert kits to measure both total coliforms and E. coli. Field staff added Colilert-18 reagent to each sample vessel and then decanted the sample into a Quanti-Tray/2000 testing tray. Field staff confirmed that they did not observe a blue flash when adding reagent to the samples, suggesting that the samples did not contain excessive chlorine41. Field staff then sealed testing trays and incubated them at 35 °C for 18 h. Each testing tray has 96 compartments: 48 large and 48 small. After incubation, field staff counted the number of large and small compartments that had turned yellow, and the number of compartments that were both yellow and fluorescent under ultraviolet light. Field staff entered these counts into the IDEXX MPN Generator software in order to obtain the Most Probable Number (MPN) of colony forming units (CFU) per 100 ml of total coliform and E. coli respectively. We tracked samples using anonymized QR barcodes. Field staff tracked samples from field collection to the laboratory using one QR barcode, and tracked samples in testing trays using a second, different QR barcode. We did not collect or test blanks, and we did not have a reliable cold chain established to allow us to use the quality control tests provided by the manufacturer.

Caretaker characteristics

All wells initially had two caretakers, one male and one female. To shed light on how caretakers compared to other members of their communities, we use household survey data collected during one of the precedent studies27. To describe how households with caretakers differ from other households in the same communities, we leverage machine learning approaches to implement a classification analysis42,43,44. Briefly, we repeat the following steps 100 times: (1) We divide the sample of communities randomly into training and prediction sets. (2) We train a random forest model to predict the likelihood that a household has a caretaker as a member in the training set. (3) We predict the likelihood of having a caretaker in the prediction set. (4) We compare the characteristics of households with a high predicted likelihood of having a caretaker household to the characteristics of households with a low predicted likelihood of having a caretaker, in the prediction set. We then take the median of the predicted parameters across the 100 iterations and adjust inference to account for the uncertainty generated by the sample splitting. The results are summarized in Supplementary Fig. 1. We also use the same data to describe how the likelihood of having a caretaker as a member varies with distance between a household and the nearest community well, using GPS coordinates for wells and households. Households with caretakers were oversampled, so we use sampling weights to adjust for sampling probability. These results are summarized in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Statistical analysis

We estimate two statistical models to evaluate the effects of treatment. The first model regresses outcome variables on indicator variables that take the value one if the well is assigned to a training treatment arm and zero otherwise. The second model regresses outcome variables on a single indicator variable that takes the value one if the well is assigned to either training treatment arm and zero otherwise. When outcome variables are binary—as for indicators of the presence of contamination—we estimate linear probability models. Linear probability models are consistent when regression models are fully saturated, as is the case here. When we analyze concentration, we use an arcsinh transformation to reduce the influence of outliers without dropping zeroes. When we analyze data from caretaker surveys, we weight observations by the inverse of the number of observations per well, so that each well counts equally in the analysis, consistent with the analyses where the well is the unit of observation. Standard errors are robust45 or clustered by well when the unit of observation is a caretaker. We summarize the results of these analyses in Figs. 3 and 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4. For the results on water quality, we also provide full results in Supplementary Tables 8a to 9b.

Cost-effectiveness of water quality improvements

The mean reduction in the presence of total coliform bacteria is 25.2 percentage points after 13 months and 31.3 percentage points after 17 months, averaging 28.2 percentage points. The median caretaker reports that wells have 25 user households after 13 months and 22 user households after 17 months, averaging 23.5. Each household has on average 3.9 members27. Each well treated thus eliminates coliform bacteria at source for approximately 0.282 × 23.5 × 3.9 = 25.9 people, at a per person cost of US$0.89.

Cost-effectiveness of potential health impacts

To model the potential reduction in child mortality, we use results from meta-analysis that suggest that water treatment interventions can reduce all-cause child mortality by 24%30. We consider mortality by age group: 0–1 year; 1–2 years; 2–3 years; 3–4 years; and 4–5 years. In rural Bangladesh, infant mortality is 34 per 1000 live births and the child mortality rate is 7 per 1000 live births, for total under-five mortality of 41 per 1000 live births7. We distribute child mortality across age groups using data from nationally-representative surveys46. We estimate the average number of children per household in each age group using household survey data from the same communities27. We assume that mortality gains only accrue to households who actually reduce exposure to coliform bacteria in drinking water, following recent guidance from meta-analysis that suggests that both E. coli and coliform bacteria more generally correlate with disease47. This assumption is still conservative because the meta-analysis we draw from does not perfectly account for compliance or the effects of water treatment interventions on water quality30. We have direct evidence that the effects persist over 17 months, and we assume that after 17 months the effects decay linearly over the same time period, equivalent to the full effects persisting for 25.5 months. Summing across age groups, we calculate that each well treated could avoid the death of 0.010 children, primarily driven by a reduction in deaths among infants (0.008). These results imply that on average treating 104 wells could avoid one child death. Following WHO guidelines48 and assuming that infant deaths result in the loss of 81.25 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and deaths at age 1 result in the loss of 80.25 DALYs and so forth, we calculate that each well treated prevents the loss of 0.78 DALYs. Taking the (slightly higher) cost for the full program (training and supplies) yields a cost per life saved of US$2376 and a cost per DALY loss averted of 29 US$.

Data availability

Anonymized data are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/4JTTKF.

Code availability

Replication code (STATA) is available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/4JTTKF.

References

WHO & UNICEF. Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2000-2020: Five Years into the SDGs (World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2021).

Wolf, J. et al. Burden of disease attributable to unsafe drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene in domestic settings: a global analysis for selected adverse health outcomes. Lancet 401, 2060–2071 (2023).

Ritchie, H., Spooner F. & Roser, M. Clean Water and Sanitation. Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/clean-water-sanitation [Online Resource] (2021).

Greenwood, E. E. et al. Mapping safe drinking water use in low- and middle-income countries. Science 385, 784–790 (2024).

UNICEF & WHO. Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2000–2022: Special Focus On Gender (United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and World Health Organization (WHO), 2023).

Bain, R. et al. Fecal contamination of drinking-water in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 11, e1001644 (2014).

BBS & UNICEF. Progotir Pathey, Bangladesh Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2019, Survey Findings Report (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics and United Nations Children’s Fund, 2019).

McKenzie, D. & Ray, I. Household Water Delivery Options in Urban and Rural India. Stanford Centre for International Development Working Paper 224 (Stanford Centre for International Development, 2004).

Ahuja, A., Kremer, M. & Zwane, A. P. Providing safe water: evidence from randomized evaluations. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2, 237–56 (2010).

Clasen, T. et al. Interventions to improve water quality for preventing diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10, 1–177 (2015).

Evidence Action. Dispensers for safe water: innovation with impact. https://www.evidenceaction.org/dispensers-2017/ (2017).

Howard, G., Ahmed, M. F., Shamsuddin, A. J., Mahmud, S. G. & Deere, D. Risk assessment of arsenic mitigation options in Bangladesh. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 24, 346–355 (2006).

Goel, V. et al. Deep tubewell microbial water quality and access in arsenic mitigation programs in rural Bangladesh. Sci. Total Environ. 659, 1577–1584 (2019).

Ravenscroft, P. et al. Effectiveness of public rural waterpoints in Bangladesh with special reference to arsenic mitigation. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 4, 545–562 (2014).

Cocciolo, S., Ghisolfi, S., Habib, A., Rashid, S. & Tompsett, A. Do community water sources provide safe drinking water? Evidence from a randomized experiment in rural Bangladesh. World Bank Econ. Rev. 35, 969–998 (2021).

Habib, M. A. et al. How to clean a tubewell: the effectiveness of three approaches in reducing coliform bacteria. Sci. Total Environ. 872, 161932 (2023).

Ferguson, A. S. et al. Hand-pumps as reservoirs for microbial contamination of well water. J. Water Health 9, 708–717 (2011).

Osborne, T. H., Ward, S. A., Ahmed, K. M. & Santini, J. M. Reservoirs of faecal indicator bacteria in well-head hand pumps in Bangladesh. J. Water Health 16, 487–490 (2018).

Mahmud, Z. H. et al. Occurrence of Escherichia coli and faecal coliforms in drinking water at source and household point-of-use in Rohingya camps, Bangladesh. Gut Pathog. 11, 1–11 (2019).

Godfrey, S. & Reed, B. in Cleaning and Rehabilitating Boreholes. Technical Notes on Drinking-water, Sanitation and Hygiene in Emergencies (ed. Reed, B.) (World Health Organization, 2013).

Ali, R. et al. Water quality before and after a campaign of cleaning and disinfecting shallow wells: a study conducted during and after floods in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev 9, 28–37 (2019).

Luby, S., Islam, M. & Johnston, R. Chlorine spot treatment of flooded tube wells, an efficacy trial. J. Appl. Microbiol. 100, 1154–1158 (2006).

Banerjee, A. V. & Duflo, E. The experimental approach to development economics. Annu. Rev. Econ. 1, 151–178 (2009).

Banerjee, A. & Duflo, E. An introduction to the “Handbook of Field Experiments”. in Handbook of Economic Field Experiments, Vol. 1 (eds Duflo, E. & Banerjee, A.) (Elsevier, 2017).

Stenberg, K. et al. Cost-effectiveness of interventions to improve maternal, newborn and child health outcomes: a WHO-CHOICE analysis for Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 10, 706 (2021).

Cocciolo, S., Habib, M. A. & Tompsett, A. Understanding Institutional Persistence: Exposure to Democratic Decision-making and the Value of Autonomy and Democracy. Pre-registered report and pre-analysis plan (Journal of Development Economics Preresults Review, 2019).

Cocciolo, S., Ghisolfi, S., Habib, A. & Tompsett, A. Time is not Money: An Experiment with Community Contribution Requirements in Cash and Labour. Working Paper. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4993670 (2023).

Madajewicz, M., Tompsett, A. & Habib, A. How does delegating decisions to communities affect the provision and use of a public service? Evidence from a field experiment in Bangladesh. J. Dev. Econ. 150, 102609 (2021).

Armand, A., Augsburg, B., Bancalari, A. & Ghatak, M. Public Service Delivery, Exclusion and Externalities: Theory and Experimental Evidence from India (No. 23/37). (Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), London, 2024).

Kremer, M., Luby, S. P., Maertens, R., Tan, B. & Wiecek, W. Water Treatment and Child Mortality: A Meta-analysis and Cost-effectiveness Analysis. Development Impact Lab Working Paper No. 2022-26 (University of Chicago Development Impact Lab, 2024).

GBD Diarrhoeal Diseases Collaborators. Estimates of global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoeal diseases: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect. Dis. 17, 909–948 (2017).

Troeger, C. et al. Global disability-adjusted life-year estimates of long-term health burden and undernutrition attributable to diarrhoeal diseases in children younger than 5 years. Lancet Glob. Health 6, Lancet Glob. e255–e269 (2018).

WHO. The World Health Report 2002: Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life (World Health Organization, 2002).

Woods, B., Revill, P., Sculpher, M. & Claxton, K. Country-level cost-effectiveness thresholds: initial estimates and the need for further research. Value Health 19, 929–935 (2016).

Chew, R., Painter, C., Pan-ngum, W., Day, N. P. J. & Lubella, Y. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a multiplex lateral flow rapid diagnostic test for acute non-malarial febrile illness in rural Cambodia and Bangladesh. Lancet Reg. Health Southeast Asia 23, 1–14 (2024).

Bertram, M. Y. et al. Disease control programme support costs: an update of WHO-CHOICE methodology, price databases and quantity assumptions. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc 15, 1–12 (2017).

UNICEF & WHO. Drinking Water Equity, Safety and Sustainability: Thematic Report on Drinking Water 2011 (UNICEF and WHO, 2011).

Hatfield, T. G., Withers, T. M. & Greaves, C. J. Systematic review of the effect of training interventions on the skills of health professionals in promoting health behaviour, with meta-analysis of subsequent effects on patient health behaviours. BMC Health Serv. Res. 20, 1–9 (2020).

McKenzie, D. et al. Training entrepreneurs. VoxDevLit 1, (2023).

Anand, G., Atluri, A., Crawfurd, L., Pugatch, T. & Sheth, K. Improving School Management in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. CGD Working Paper 648 (Center for Global Development, 2023).

Gregorio, D. In Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) 3.4.1.1.: Coliform Bacteria Analysis: Colilert 18 Hr. Method with Quanti-Trays (State Water Resources Control Board, 2010).

Chernozhukov, V., Fern ndez-Val, I. & Galichon, A. Improving point and interval estimates of monotone functions by rearrangement. Biometrika 36, 559–575 (2009).

Chernozhukov, V., Demirer, M., Duflo, E. & Fernández-Val, I. Fisher-Schultz Lecture: Generic machine learning inference on heterogenous treatment effects in randomized experiments, with an application to immunization in India. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1712.04802 (Asian Development Bank Institute, 2023).

Habib, M. A., Madajewicz, M. & Tompsett, A. When Does Community Participation in Decision-making Improve Outcomes? Evidence from a Field Experiment in Bangladesh. ADBI Working Paper 1406 (Asian Development Bank Institute, 2023).

Long, J. S. & Ervin, L. H. Using heteroscedasticity consistent standard errors in the linear regression model. Am. Stat. 54, 217–224 (2000).

Rahman, A. E. et al. Child mortality in Bangladesh—why, when, where and how? A national survey-based analysis. J. Glob. Health 11, 04052 (2021).

Goddard, F. G. B. et al. Faecal contamination of the environment and child health: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Planet Health 4, e405–e415 (2020).

WHO. WHO Methods and Data Sources for Global Burden of Disease Estimates 2000-2019 Vol. WHO/ DDI/DNA/GHE/2020.3 of Global Health Estimates Technical Paper (WHO Department of Data and Analytics Division of Data, 2020).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding by the Swedish Research Council Formas (2018-01107). We thank NGO Forum for Public Health for their partnership in undertaking this study, in particular Executive Director Mr. S.M.A. Rashid. Md. Rezwanul Karim and Md. Abdul Haque provided excellent research assistance. Thanks for helpful comments and suggestions to Britta Augsburg and Ian Ross, as well as participants in the WASH Economics Conference.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stockholm University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: S.C., M.A.H., and A.T. Methodology: S.C., M.A.H., and A.T. Software: S.C. and A.T. Formal analysis: M.A.H. and A.T. Investigation: M.A.H. and M.M.A.R. Resources: M.A.H. Data curation: S.C., M.A.H., M.M.A.R., and A.T. Writing—original draft: M.A.H. and A.T. Writing—review & editing: S.C. and P.B. Visualization: A.T. Supervision: P.B., M.A.H., and A.T. Project administration: M.A.H. and A.T. Funding acquisition: P.B. and A.T. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: M.A.H. and M.M.A.R. declare that they are employed by NGO Forum for Public Health, the partner non-governmental organization in this study. P.B., S.C., and A.T. declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Habib, M.A., Cocciolo, S., Raihan, M.M.A. et al. Training caretakers to clean community wells is a highly cost-effective way to reduce exposure to coliform bacteria. npj Clean Water 7, 110 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-024-00401-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-024-00401-x