Abstract

Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) can be used as a potential photocatalyst for the removal of emerging contaminants (ECs) under visible light (Vis). However, the high carrier recombination rate and aggregation restrict pure MoS2 application. The hydrothermal method was used to prepare a novel MoS2/BaSO4/zeolite (Z) composite (MBZ), which was used to activate peroxymonosulfate (PMS) under visible light for sulfadiazine (SDZ) degradation. The MBZ showed a moderate Eg value (2.59 eV), indicating good visible-light absorption. The physicochemical and photoelectrochemical properties were analyzed, revealing that the hybrid MBZ significantly enhanced photoinduced carrier generation, separation, and transfer. The MBZ exhibited 2.38-, 3.24-, and 1.36-fold higher SDZ removal reaction rates than Z, BaSO4, and MoS2 in the PMS/Vis system. The addition of EDTA-2Na notably decreased the degradation rate (79.58–89.88%), indicating the significant role of h+. This work provides a new approach to the design of semiconductor/insulator photocatalysts and constructs a promising catalytic oxidation system for the green remediation of EC wastewater.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays, emerging contaminants (ECs) from antibiotics are frequently identified worldwide, raising significant concerns globally1,2,3. It is estimated that the global daily-dose antibiotic consumption by humans will reach 84 billion by 20304,5,6. Sulfadiazine (SDZ) is widely used to treat diseases caused by bacterial infections7,8. After ingestion, 70%–90% of the SDZ is excreted into natural water via urine and feces7. Due to its long half-life, SDZ can accumulate continuously in the environment, potentially leading to the emergence of superbugs and resistant genes that pose significant risks to ecosystems and human health. Therefore, developing effective antibiotic degradation techniques is imperative.

The primary techniques currently used for SDZ wastewater treatment include physical9,10, biological11,12, and advanced oxidation processes (AOPs)7,13,14,15,16. AOPs can efficiently degrade SDZ by generating various active substances. In particular, the photocatalytic oxidation process has attracted considerable attention due to its eco-friendly characteristics. The degradation efficiency of this technique is mostly influenced by the light source and photocatalyst. Although ultraviolet (UV)-driven photocatalysts and catalytic systems have been extensively studied13,17,18, sunlight is mainly concentrated in the visible region, with UV light only accounting for about 4%–5%19,20. Therefore, developing new visible-light photocatalysts is essential for the efficient use of sunlight to catalyze SDZ degradation.

Many semiconductors have been developed in recent decades that are considered potential photocatalysts, including C3N421,22, metal oxides (TiO2, ZnO, etc.)23,24,25,26,27,28, and metal sulfides (MoS2, CuS, etc.)29,30,31,32. MoS2 has attracted considerable attention due to its cost-efficiency and excellent visible-light absorption capacity, which is attributed to its narrow bandgap (0.9–1.9 eV)31,33,34. MoS2 irradiation with light exceeding or equal to its bandgap energy produces electrons (e−) and holes (h+)31,35, which can combine or react with O2, OH−, and H2O to generate active substances for SDZ degradation. However, Zhang et al. 36 showed that the transient photocurrent density response and surface photovoltage (SPV) spectral signal of pure MoS2 are exceedingly weak, implying low charge carrier separation. Various studies have confirmed the slow charge carrier transfer rate of pure MoS2 via photoluminescence spectra (PL) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analysis37,38,39,40. In addition, the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the pure MoS2 show agglomeration38,41,42, which reduces its photocatalytic capacity. Since the application potential of pure MoS2 is limited by its high carrier recombination rate and aggregation, it is necessary to design a novel heterostructured MoS2 composite to address these issues simultaneously.

Insulator-based (wide-bandgap) photocatalysts have attracted substantial domestic and global research attention in recent years due to their abundant yield, cost-efficiency, and environmental friendliness43,44,45. Hao et al. 46 indicated that SiO2 increased the specific surface area of SiO2/g-C3N4 and facilitated the separation and transfer of electron-hole pairs. Wang et al. 47 constructed a BaCO3/BiOI heterojunction, which effectively transferred e− from the semiconductor to the insulator, enhancing charge carrier separation. Cui W et al. 48 synthesized BaSO4 with Ba vacancies to give the insulator BaSO4 semiconductor-like photocatalytic properties. Mohsen A et al. 49 used a one-step hydrothermal method to synthesize nano-BaSO4, which showed excellent catalytic degradation ability of methylene blue at UVA (320~400 nm). Chen et al. 45 used CaCO3 to effectively restrict the combination of AgBr electron-hole pairs. The pseudo-first-order kinetic constant for tetracycline (TC) degradation by AgBr-CaCO3 under visible light was seven-fold higher than AgBr. Additionally, BaSO4-CuS was prepared via in-situ sedimentation and precipitation. The composite showed a smaller electrochemical impedance Nyquist semicircle diameter, a stronger photocurrent response, and weaker PL intensity than pure CuS50. Therefore, it may facilitate rapid light-induced carrier separation and transfer by constructing heterojunctions with MoS2 using wide-bandgap insulators.

Fixing the nano-semiconductor photocatalysts on a suitable supporter to improve its dispersibility can effectively inhibit aggregation and improve its photocatalytic activity. Zeolite is an effective supporter of semiconductor photocatalysts due to its excellent surface area and abundant active Lewis acid sites51,52,53,54,55. Yang et al. 56 dispersed g-C3N4/AgCl on the surface of ZSM-5, which significantly improved charge separation. The photocatalytic visible-light activity of the composite was 3.59-fold that of g-C3N4/AgCl. Tang J et al. 57 loaded TiO2 nanosheets onto hydrophobic NaY zeolite, which significantly enhanced the adsorption capacity, carrier separation efficiency, and mineralization capacity of the composite catalyst. Li et al. 58 uniformly dispersed nano-Co3O4 on hollow ABW zeolite via impregnation, substantially improving the degradation efficiency of organic dyes by coupling adsorption and photocatalysis. Therefore, using zeolite as a supporter for MoS2 not only addresses the aggregation issue but also improves the low contact between MoS2 and SDZ and the high carrier recombination rate.

This work designs a novel MoS2/BaSO4/zeolite composite (MBZ) and effectively applies it for photocatalysis in conjunction with peroxymonosulfate (PMS) activation to degrade SDZ. In particular, the changes in the physicochemical properties, photo-responsiveness, and charge separation and transfer characteristics of the composite are investigated, while the mechanism behind enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity is clarified. The SDZ degradation mechanism is determined via systematic photocatalytic experiments and performance analysis.

Results and discussion

Structural characterization

The XRD pattern (Fig. 1a) of Z showed an analcime-C type structure (JCPDS No. 41-1478). As illustrated in Fig. 1b, the pure BaSO4 displayed a significant diffraction peak (JCPDS No. 24-1035), while that of the pure MoS2 was relatively weak (JCPDS No. 37-1492). The MBZ XRD pattern presented obvious BaSO4 diffraction peaks at 20.451°, 22.788°, 24.871°, 25.840°, 26.839°, 28.746°, 31.520°, 32.716°, 36.160°, 38.696°, 39.455°, 40.777°, 42.590°, 42.908°, 43.983°, 47.001°, and 48.999°. The MBZ exhibited no noticeable characteristic MoS2 peaks, which was attributed to the weak intensity of pure MoS2, while those at 15.841° and 25.991° were ascribed to Z. The characteristic Z peaks were significantly reduced in the MBZ, which were mainly related to MoS2 coverage and the X-ray absorbent ability of BaSO4. Except for a slight intensity decline, the MBZ diffraction peaks remained mostly unchanged, indicating a relatively stable MBZ crystal structure.

a The XRD pattern of Z. b The XRD patterns of pure BaSO4 and pure MoS2, as well as the fresh and initially used MBZ. In both (a) and (b), the black clubs represent analcime-C. In (b), the diamond (and green line) and the black circles (and blue line) refer to BaSO4 and MoS2, respectively. The black and red lines represent fresh and initially used MBZ, respectively. c The N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of the samples. d The pore size distribution of the samples. In both (c) and (d) the gray, orange, green, black, and red sphere lines or straight lines refer to BaSO4, MoS2, and Z, as well as the fresh and initially used MBZ, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 1c, the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of the MBZ was accompanied by an H3-type hysteresis loop, which was attributed to the slit pores formed by MoS2 sheet accumulation. The SBET and Vtot of the MBZ significantly exceeded that of the pure substances (Z, BaSO4, and MoS2) by about 8.96–18.45 m²/g and 0.061–0.081 cm³/g, respectively (Table 1). The MBZ pore volume increased noticeably after application (Fig. 1d and Table 1), indicating that the catalytic reaction affected the MBZ pore size and structure.

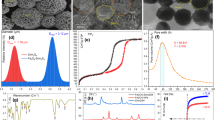

The SEM images of Z showed cubic, spherical shapes characteristic of analcime-C morphology (Fig. 2a). The MBZ surface was covered with MoS2 sheets with a distinct edge-like structure, which provided more active sites (Fig. 2b1, b2). In addition, it can be inferred that the Z and BaSO4 surfaces are successfully covered with MoS2 sheets during hydrothermal treatment. This was confirmed by the EDS spectra and elemental distribution (Fig. 2c1–c3) of the MBZ. Compared with Fig. 2b2, d, the MBZ surface morphology displayed no significant changes after the catalytic reaction. However, EDS (Supplementary Fig. 1) showed that the Al, Si, and Ba content on the MBZ surface increased after the catalytic reaction, while the Mo, S, and Fe levels decreased, which was related to surface element leaching.

a The SEM image of Z. b The SEM images of the fresh MBZ. c1, c2 The EDS spectra of the fresh MBZ. The individual elemental content is as follows (at. %): 16.25% O, 0.60% Na, 0.17% Al, 52.27% Si, 24.41% S, 0.03% Fe, 6.15% Mo, and 0.12% Ba. c3 The elemental distribution in the fresh MBZ. d The SEM image of the initially used MBZ. The scale bars are 5 μm (white), 1 μm (orange), and 2.5 μm (yellow), respectively.

XPS energy spectrum

The XPS wide-scan spectra (Supplementary Fig. 2) indicated that the MBZ contained Ba, Mo, O, and S elements, showing successful BaSO4 and MoS2 hybridization with Z. The two characteristic peaks of the pure BaSO4 at 780.62 eV and 795.92 eV (Fig. 3a) corresponded to Ba 3d5/2 and Ba 3d3/250, which shifted to higher bonding energies at 780.65 eV and 795.95 eV after MBZ formation. The S 2p spectrum of the MBZ (Fig. 3b) presented two deconvoluted peaks at 161.31 eV and 162.70 eV, which were associated with the S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2 of S2− oxidation states in MoS259,60,61. The characteristic peaks at 168.99 eV and 170.40 eV were related to the SO42− in BaSO4. The Mo 3d high-resolution spectrum of MoS2 at bonding energies of 228.9 eV and 232.2 eV (Fig. 3c) corresponded to Mo 3d5/2 and Mo 3d3/262,63,64, which shifted toward lower energies at 228.06 eV and 231.65 eV after hybridization with Z and BaSO4. Additionally, the O 1s characteristic peaks (Fig. 3d) of BaSO4 shifted to higher bonding energies. The characteristic peaks of the major elements (Al, Si, and O) in Z (Supplementary Fig. 3) and all the elements (Ba, S, and O) in BaSO4 shifted toward higher bonding energies after hybridization, while those of MoS2 moved to a lower level, demonstrating a strong interaction and electron transfer between BaSO4, MoS2, and Z.

The photoelectrochemical properties of the photocatalysts

Fig. 4a displays the UV-Vis DRS spectra, Z exhibited absorption between 200 nm and 300 nm (UV light). The pure BaSO4 presented almost negligible absorption properties throughout the spectral band. A distinct red shift was evident in the DRS of the MBZ after adding MoS2, implying a significant improvement in the visible-light absorption properties. The corresponding bandgap energy (Eg) of the photocatalysts was calculated using Tauc’s relation (Eq. (1))65,66, yielding values of 4.15 eV, 1.80 eV, 4.07 eV, and 2.59 eV for Z, MoS2, BaSO4, and MBZ, respectively (Fig. 4b). The moderate Eg value of the MBZ indicated good visible-light absorption.

a The UV-Vis DRS spectra of Z, MoS2, BaSO4, and MBZ. b The bandgap energy spectra of Z, MoS2, BaSO4, and MBZ. c The photoluminescence spectra of Z, MoS2, BaSO4, and MBZ. d The EIS Nyquist plots of Z, MoS2, BaSO4, and MBZ. e The photocurrent responses of Z, MoS2, BaSO4, and MBZ. The green, gray, pink, and blue lines or spheres represent Z, MoS2, BaSO4, and MBZ, respectively.

The photocatalytic activity was affected by the light absorption capacity and response range, as well as the separation efficiency of the photogenerated carrier. PL analysis (Fig. 4c) indicated that the Z, MoS2, BaSO4, and MBZ showed different characteristic intensity peaks at around 530 nm (Z > BaSO4 > MoS2 > MBZ). MBZ showed the lowest emission intensity, indicating a lower photoelectron-hole recombination rate and efficient charge separation compared to the others29,67. This was attributed to the formation of the MBZ hybrid structure, which effectively inhibited photogenerated carrier recombination60,68. The electron transfer rate of the photocatalyst was evaluated via EIS, and the results are shown in Fig. 4d. The smaller semicircle diameter in the EIS Nyquist plots indicated that the material displayed lower electrochemical impedance and a faster charge transfer rate69,70. The MBZ exhibited the highest charge mobility, as well as the smallest semicircle diameter, indicating that the hybrid Z, MoS2, and BaSO4 combination significantly weakened the photoinduced electron transfer resistance. The photocurrent response of the photocatalysts was analyzed under visible-light irradiation. As shown in Fig. 4e, the MBZ exhibited the highest photocurrent density, illustrating that hybrid structure formation accelerated photoinduced charge generation and separation50,71. These results showed that the Z, MoS2, and BaSO4 hybrid combination significantly enhanced the generation, separation, and transfer of the photoinduced carriers.

The photodegradation of sulfadiazine

The photocatalytic properties were evaluated via SDZ removal experiments (Fig. 5a). SDZ removal was challenging when using only MBZ (25.89%) or PMS (32.46%) under visible-light irradiation, reaching a rate of 69.58% in 180 min when using MBZ to activate PMS. The SDZ removal efficiency of MBZ/PMS/Vis (99.01%) increased significantly and was about 73.12% and 29.43% higher than MBZ/Vis and MBZ/PMS, respectively, suggesting excellent synergy between MBZ and PMS activation under visible light. In the PMS/Vis system, the SDZ removal efficiency of MBZ was notably higher than Z, BaSO4, and MoS2. The MBZ reaction rate was 2.38-, 3.24-, and 1.36-fold that of Z, BaSO4 and MoS2, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Fig. 5b). These results demonstrated the importance of MBZ hybrid structure formation, which was also confirmed in Supplementary Fig. 5.

a The SDZ photodegradation by Z, BaSO4, MoS2, and MBZ in the different systems. b The SDZ photodegradation reaction rates of Z, BaSO4, MoS2, and MBZ in the different systems. The yellow, green, blue, dark purple, pink, gray, and black lines or bars represent Z/PMS/Vis, MoS2/PMS/Vis, BaSO4/PMS/Vis, MBZ/Vis, PMS/Vis, MBZ/PMS and MBZ/PMS/Vis, respectively. c The impact of the synthesis conditions on MBZ with varying Mo concentrations (CMo). The light blue, blue, green, gray, pink, and purple symbols refer to CMo = 1 mM, 3 mM, 4 mM, 5 mM, 6 mM, and 7 mM, respectively. d The impact of the synthesis conditions on MBZ with different added BaSO4 quantities (x g BaSO4/1 g zeolite = x/1). The light blue, blue, gray, green, purple, orange, pink, and gray symbols refer to x = 0.05, 0.1, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, and 0.8, respectively. (Conditions: 25 °C, [SDZ] = 20 mg/L, [Photocatalyst] = 0.2 g/L, [PMS] = 0.31 mM, and initial pH = 6.8, [P visible light] = 90 W).

During MBZ hybrid structure formation, the Mo concentration (CMo) directly affected MoS2 production. The degradation efficiency increased from 67.30% to 99.01% as the CMo increased from 1 mM to 5 mM (Fig. 5c). However, when the CMo increased to 6 mM and 7 mM, the SDZ removal rate decreased to 95.54% and 89.17%, causing excess MoS2 accumulation and reducing active surface site exposure. The effect of the added BaSO4 quantity showed a similar trend (Fig. 5d). These results indicated that the CMo and added BaSO4 quantity were crucial for improving the MBZ catalytic activity.

Practical application capacity

As shown in Fig. 6a, HCl-regulated acidic conditions promoted the SDZ degradation ability of the MBZ/PMS/Vis system, while this capacity was inhibited by NaOH-regulated alkalinity. When the initial pH increased from 3 to 6.8, the SDZ removal rate declined from 100% to 99.01% in 180 min. Further increasing the initial pH to 8–10 significantly decreased the SDZ degradation rate to between 15.80% and 7.73%. This was primarily attributed to the MBZ surface charge, which increased at a higher pH and became negative at a solution pH exceeding 2.10 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Therefore, MBZ repelled HSO5− in alkaline conditions (Supplementary Fig. 7). This inhibited the contact reaction between MBZ and PMS, which reduced active substance production. However, acidic conditions regulated by HNO3 and H2SO4 significantly reduced the ability of the MBZ/PMS/Vis system to degrade SDZ (Supplementary Fig. 8). This was contrary to the HCl regulatory effect and was possibly related to the role of anions (Cl−, NO3−, and SO42−).

a The effect of the initial pH value regulated by HCl and NaOH. The gray, pink, blue, black, purple, orange, and khaki symbols refer to pH = 3, 4, 5, 6.8, 8, 9, and 10, respectively. b The effect of the coexisting inorganic anions (black-control group, red-coexist Cl−, blue-coexist SO42−, and green-coexist NO3−) on SDZ photodegradation. c The SDZ removal in actual water (black-deionized water, red-tap water, blue-river water, and green-lake water). d The reusability of the MBZ in the MBZ/PMS/Vis system. (Conditions: 25 °C, [SDZ] = 20 mg/L, [Photocatalyst] = 0.2 g/L, [PMS] = 0.31 mM, and initial pH = 6.8, [P visible light] = 90 W).

In particular, the inorganic anions commonly found in natural water significantly impact pollutant degradation. Fig. 6b shows the effect of Cl−, SO42−, and NO3− on the SDZ removal efficiency. Cl− accelerated SDZ degradation, which was attributed to the production and participation of chlorine-based radicals72,73,74. SO42− and NO3− significantly inhibited SDZ removal in MBZ/PMS/Vis since they interacted with ‧OH and SO4‧− to form less reactive substances72,75. Furthermore, studies have suggested that the presence of nitrate may compete for radiation76,77. The results elucidated the reasons contributing to the differences in HCl, HNO3, and H2SO4 acidity regulation.

The ability of the MBZ/PMS/Vis system to degrade SDZ in actual water was explored using tap water, Tianlai Lake water (Xihua University, Chengdu, China), and Tuojiang River water (Chengdu, China). As shown in Fig. 6c, the ability of the MBZ/PMS/Vis system to effectively degrade SDZ in actual water decreased significantly. This was attributed to the presence of inorganic anions (SO42−, NO3−, etc) and the alkalinity of the water (Supplementary Table 1).

Besides SDZ, the degradation rates of TC and norfloxacin in the MBZ/PMS/Vis system were 96.62% and 97.55%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 9). The results indicated that MBZ could degrade a wide range of antibiotic organics. The reusability of MBZ was investigated by monitoring the degradation rate in the MBZ/PMS/Vis system for five consecutive cycles. As shown in Fig. 6d, the SDZ removal rate decreased to 88.23% after three cycles, while it remained above 75% after five cycles. The decrease in the SDZ removal rate was mainly related to the loss of active components on the MBZ. Therefore, the leaching elements in the SDZ solution were detected via ICP-OES after the catalytic reaction. The results showed a small amount of Fe (0.158 mg/L) and Ba (0.057 mg/L), as well as 1.161–4.095 mg/L of Na and Al and a high concentration of Mo (15.407 mg/L) in the solution (Supplementary Fig. 10). The reduced catalytic activity was primarily attributed to the leaching of these substances.

The photodegradation process and mechanism

Reactive species play a critical role in the PMS and photocatalytic reaction system. A range of quenching experiments were performed to investigate the active species during SDZ degradation in the MBZ/PMS/Vis system. TBA, p-BQ, EDTA-2Na, and FFA were used as the ·OH, O2.−, h+, and 1O2 trapping agents, respectively. MeOH was used as a scavenger for SO4·− and ⋅OH since it reacted to both radical species (k(MeOH, ·OH) = 9.7 × 108 M−1 s−1, k(MeOH, SO4·−) = 2.5 × 107 M−1 s−1)14.

As illustrated in Fig. 7a, the SDZ removal rate decreased from 99.01% to 59.40–49.42% (a reduction of 39.61–49.59%) after adding MeOH to the reaction system. At the same dosage, the inhibitory effect of TBA was distinctly lower than that of MeOH, displaying a reduction of 4.90–26.14% (Fig. 7b). These results suggest that both SO4·− and ⋅OH promote the degradation process. As shown in Fig. 7c, d, FFA and p-BQ significantly inhibited the reaction, indicating the presence of 1O2 and O2.−, which substantially impacted the SO4·− and ⋅OH in the system. EDTA-2Na displayed the strongest inhibitory effect (a reduction of 79.58–89.88%) on SDZ photodegradation (Fig. 7e). This implies that h+ has the highest impact on the degradation of SDZ in the MBZ/PMS/Vis system.

a The impact of MeOH on SDZ photodegradation in the MBZ/PMS/vis system. b The impact of TBA on SDZ photodegradation in the MBZ/PMS/vis system. c The impact of FFA on SDZ photodegradation in the MBZ/PMS/vis system. d The impact of p-BQ on SDZ photodegradation in the MBZ/PMS/vis system. e The impact of EDTA-2Na on SDZ photodegradation in the MBZ/PMS/vis system. In (a–e), the gray symbols represent the control group. In (a–c), the pink, green, and blue symbols refer to quencher concentrations of 20 mM, 50 mM, and 100 mM, respectively. In (d), the pink, green, and blue symbols refer to p-BQ concentrations of 0.5 mM, 1 mM, and 2 mM, respectively. In (e), the pink, green, and blue symbols refer to EDTA-2Na concentrations of 5 mM, 10 mM, and 20 mM, respectively. f The ESR spectra of DMPO-·OH (black club), SO4·− (black circle), TEMP-1O2 (spade), and DMPO-O2·− (black square) in the MBZ/PMS/vis system. (Conditions: 25 °C, [SDZ] = 20 mg/L, [Photocatalyst] = 0.2 g/L, [PMS] = 0.31 mM, and initial pH = 6.8, [P visible light] = 90 W).

The ROS in the MBZ/PMS/Vis system was investigated via electron spin resonance (ESR) tests using DMPO and TEMP as trapping agents. As depicted in Fig. 7f, strong DMPO-·OH, DMPO-SO4·−, TEMP-1O2, and DMPO-O2·− adduct signals were detected in the system under visible-light irradiation.

Notably, the photocatalytic ability of the photocatalyst was closely related to its band structure. The bandgap energy and band orientation of the heterojunction directly affected photogenerated electron and hole formation and carrier migration direction. The valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB) of the MoS2 and BaSO4 were calculated using the following formulas (Eqs. (2) and (3))45,59,78:

EVB, ECB, and Ee represent the VB edge potential, the CB edge potential, and the free electron energy on the hydrogen scale (4.5 eV), respectively. X is the absolute electronegativity of the photocatalyst and can be derived from the absolute electronegativity of its constituent atoms (XMo = 3.9 eV, XS = 6.22 eV, XBa = 2.4 eV, XO = 7.54 eV)79. The geometric mean values80,81 of MoS2 and BaSO4 are 5.32 eV and 6.03 eV50, respectively.

The DRS results (Fig. 4b) showed that the Eg values of MoS2 and BaSO4 were 1.80 eV and 4.07 eV, respectively. Using Eqs. (2) and (3), the ECB values of MoS2 and BaSO4 were calculated as −0.08 eV and −0.505 eV, while the EVB values were 1.72 eV and 3.565 eV, respectively.

The Mott–Schottky plots (Supplementary Fig. 11) showed positive MoS2 and BaSO4 slopes, indicating that they were n-type semiconductors. The n-type materials demonstrated that the carriers of the pure MoS2 and BaSO4 were primarily electrons. Previous studies showed that the Fermi levels (Ef) of MoS2 and BaSO4 were close to their respective ECB levels29,50,60,82. When MoS2 and BaSO4 came into contact, electrons were transferred from BaSO4 (higher Ef) to MoS2 (lower Ef), resulting in an unequal Ef shift and equilibrium83,84. This was also confirmed by the high-resolution XPS spectra of the MBZ for Ba 3d, S 2p, and Mo 3d (Fig. 8). The ECB (−0.505 eV) and EVB of the pure BaSO4 satisfied the conditions for⋅O2·− (O2/O2·− = −0.33 eV) and ·OH (H2O/·OH = 1.99 eV) formation85,86, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 8a–c, a significant shift was evident in the high-resolution XPS spectra of MBZ Ba 3d, S 2p, and Mo 3d after application, indicating an electron gain and loss process on the MBZ surface. The Ba 3d peaks (Fig. 8a) shifted to higher bonding energies, indicating that the Ba underwent electron loss. The S 2p peak shift (Fig. 8b) was associated with both BaSO4 and MoS2. The XPS spectrum of Mo 3d (Fig. 8c) was also analyzed, showing that the Mo 3d5/2 spectra in the MBZ (Fig. 8d) at 227.83 eV87, 229.07–229.10 eV, and 234.00 eV88,89 corresponded to Mo(IV), Mo(V), and Mo(VI), respectively. After application, the Mo(IV) content in the MBZ increased by 13.63%, while Mo(V) and Mo(VI) decreased by 5.45% and 8.18%, respectively. This was attributed to the reaction between high-valent molybdenum and PMS (Eqs. (5–7))89,90,91. Previous studies have shown that the iron on the MBZ surface may undergo the reactions delineated in Eqs. (7–10)89,90,92,93, while XPS is difficult to detect due to its low content (Supplementary Fig. 12).

These results elucidated the possible photodegradation mechanism of the MBZ/PMS/Vis system (Fig. 9). When MBZ was exposed to visible-light irradiation, the e− transferred from the VB to the CB (MoS2), while the h+ remained in the VB. Here, the e− directly reacted with O2, which dissolved in water to form O2·− (Eq. (11))74. If PMS was present, it acted as an electron acceptor to capture the e− and produce SO4·− and ·OH (Eqs. (12) and (13))63,72. In addition, PMS can react with molybdenum/iron (which on the surface of the MBZ and leaching in solution) (Eqs. (4)–(10)). Some PMS molecules were also self-degraded into SO4·− and OH−/·OH under visible-light excitation (Eq. (14))72,94,95. The PMS displayed substantial decomposition as the reaction time increased (Supplementary Fig. 13). Furthermore, h+ can be utilized in various processes, including direct oxidative SDZ decomposition and during the reaction with H2O or -OH to generate ·OH (Eq. (15))72,96. In addition, ·OH reacts with H2O2 to form O2·− (Eq. (16)), which further reacts with ·OH to produce 1O2 (Eq. (17))63,72,74. 1O2 can also be generated using Eq. (18)97,98. The quenching experiments showed that SO4·−, ·OH, O2.−, h+, and 1O2 promoted SDZ degradation, while O2.−, 1O2, and h+ exhibited the most significant influence. Therefore, this process (Eqs. (11–18)) promoted e− and h+ separation, accelerated PMS activation, and enhanced active substance generation, which facilitated effective SDZ degradation.

The SDZ degradation intermediates in the MBZ/PMS/Vis system were identified via ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Supplementary Table 2 summarizes the main intermediates. The five possible SDZ photodegradation pathways in the MBZ/PMS/Vis system were proposed based on the detected products and previous studies (Fig. 10).

In pathway I, the reactive species hydroxylated the SDZ to P1, which was methylated to P2. The C–N bond connecting the pyrimidine and benzene ring was broken to form P4. In addition, P1 could also be converted to P2 by opening the ring. In pathway II, the SDZ was hydrolyzed to P5 and P6, which underwent smiles-type rearrangement to produce P775. P6 could also be converted to P8. In Pathway III, the S–C and S–N of SDZ were attacked by the reactive species, extruding SO2 to form P9, which was further converted to P1013. In pathway VI, a reactive species attack broke the SDZ C–N bond to form P11. In pathway V, the SDZ was transformed into P12 via the open-loop process. Either way, these intermediates were eventually further oxidized to CO2 and H2O.

In summary, this study successfully prepares a novel MBZ composite. Electrons are transferred from BaSO4 to MoS2 when the two come into contact. The MBZ shows good visible-light absorption ability. The Z, MoS2, and BaSO4 system significantly enhances photoinduced carrier generation, separation, and transfer. The MBZ/PMS/Vis system exhibits an excellent SDZ removal rate due to the synergistic effect between MBZ and PMS activation under visible light. In the system, h+ has the most significant impact on SDZ degradation, followed by 1O2 and O2.−. SDZ undergoes hydroxylation, methylation, ring-opening, and is further oxidized into CO2 and H2O. MBZ can also degrade a wide range of antibiotic organics. This study shows that combining zeolite with an insulator, and a semiconductor displays promise for realizing efficient catalytic degradation in EC-polluted water.

Methods

Chemical reagents

The sodium hydroxide (NaOH), sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3), and ethanol (CH3CH2OH) were obtained from Chengdu Kelong Chemicals Co. Ltd. The sodium silicate (Na2SiO3•9H2O), ammonium molybdate tetrahydrate (H24Mo7N6O24•4H2O), L-cysteine (HSCH2CH(NH2)CO2H, 99%), barium sulfate (BaSO4), SDZ (C10H10N4O2S, 98%), p-benzoquinone (p-BQ, C6H4O2, 97%), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt dihydrate (EDTA-2Na, C10H14N2Na2O8•2H2O, 98%), and tert-butyl alcohol (TBA, C4H10O, 99.5%) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co. Ltd. The furfuryl alcohol (FFA, C5H6O2, 98%) was supplied by Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co. Ltd., while the PMS (KHSO5•0.5KHSO4•0.5K2SO4, ≥ 47%) was obtained from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co. Ltd. The formate (CH2O2, HPLC, ≥98%), acetonitrile (CH3CN, HPLC), and methanol (MeOH, CH3OH, HPLC) were purchased from ANPEL Laboratory Technologies (Shanghai) Inc.

Preparation and characterization of the photocatalyst

Lithium silicon powder (LSP, mainly consisting of (wt%) 13.29% Al, 26.61% Si, and 0.42% trace Fe, etc.) was used as the raw zeolite material. Here, 3 g of NaOH, 7.1322 g of Na2SiO3•9H2O, and 6 g of LSP were mixed with 20 mL of deionized water in a 100 mL beaker. The mixture was stirred for 2 h until dissolved completely and hydrothermally treated in an autoclave at 140 °C for 5 h. The product was filtered, washed with deionized water until neutral, dried at 105 °C, and labeled as Z.

Then 0.8828 g of H24Mo7N6O24•4H2O and 2.4477 g of HSCH2CH(NH2)CO2H were dissolved in 30 mL deionized water and prepared into solutions A and B, respectively. Solution B was slowly poured into A and mixed thoroughly via continuous stirring. Then, 1 g of Z and 0.3 g of BaSO4 were added and continuously stirred for 10 min. After ultrasonication for 30 min, the sample was immediately transferred to a 100 mL autoclave and hydrothermally treated at 220 °C for 24 h. Finally, the subsequent aqueous solution was ultrasonicated (40 kHz, 150 W, and 25 °C) for 10 min, cleaned with ethanol and deionized water, and dried at 80 °C for 12 h to obtain the MBZ (Fig. 11).

The crystal-phase structure of the photocatalyst was analyzed via SmartLab X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku) at 2θ from 5° to 80° (at a scanning step of 0.02°/s). The XRD test used Cu Kα (λ = 1.5406 Å) as the radiation source, an acceleration current of 25 mA, and a voltage of 40 kV. SEM (Thermo Scientific Apreo 2C) was used to observe the surface morphology of the photocatalyst, while the elemental composition was analyzed using an Ultim Max 65 (Oxford). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, AXIS Ultra DLD, Kratos) was conducted using Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV, 150 W). The visible-light absorption performance of the photocatalyst was measured using UV-3600 PLUS ultraviolet and visible spectrophotometers (Shimadzu, 800–200 nm). The PL spectra were obtained at an excitation wavelength of 400 nm (Edinburgh FLS1000/FS5).

The EIS (0.5 M Na2SO4) and transient photocurrent response (2.5 mM K3[Fe(CN)6]) of the photocatalyst were measured using a CHI 760E electrochemical workstation (CH Instruments Inc.) in a cell with three electrodes. Ag/AgCl, a platinum plate, and ITO were used as the reference electrode, counter electrode, and working electrode, respectively. A 10 mg powder sample was dispersed in a 1 mL ethanol solution, after which a 50 μL Nafion solution was added and ultrasonicated for 30 min to form a uniform suspension. Then, 100 μL of the suspension was added drop-wise onto the ITO glass and dried naturally at room temperature for the photoelectric test. A transient photocurrent response test was performed using a 500 W xenon lamp (full spectrum) with 0.5 V applied bias. EIS was performed at a frequency of 0.1 Hz–100 kHz.

Photocatalytic experiments

Here, 0.02 g MBZ was added to a 100 mL SDZ solution (20 mg/L, 25 °C, 300 rpm) and reacted in the dark to achieve adsorption-desorption equilibrium. Then, 0.02 g (0.31 mM) PMS was added to the mixture and exposed to visible light. At the interval time, 3 mL of the reaction solution was separated and quickly passed through a 0.22 μm polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) filter membrane, placed in a chromatographic bottle containing a 0.1 mL (0.2 mol/L) sodium thiosulfate solution, and quantitatively analyzed at 265 nm using a liquid chromatograph (LC-16, Shimadzu). The initial pH of the SDZ solution was adjusted with 1 mol/L NaOH or HCl.

Previous research indicated that the SDZ degradation conformed to pseudo-first-order kinetics. Therefore, this kinetics model (Eq. (19)) was used to fit the experimental results75,99:

where C0 and Ct represent the SDZ concentration at the initial and t reaction time (min) (mg/L) and k is the pseudo-first-order kinetic rate constant (min−1).

Analytical methods

The SDZ concentration was determined using a liquid chromatograph (LC-16, Shimadzu) equipped with a C18 chromatographic column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, Agilent). The mobile phase (0.5 mL/min) consisted of methanol and 0.5% formic acid. The methanol ratio included formic acid (0.5%, V:V = 20:80), while the column temperature was 30 °C and the sample injection volume was 20 μL.

The SDZ photodegradation intermediates were analyzed using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (Ultimate 3000 UHPLC-Q Exactive, Thermo Scientific). An Eclipse Plus C18 column (100 mm × 4.6 mm, 3.5 µm) was used for SDZ and intermediate separation, with a mobile phase (0.3 mL/min) comprising a 0.1% formic acid solution and acetonitrile (V:V = 30:70), an injection volume of 10 μL, and a column temperature of 30 °C. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive (3.8 kV) and negative (2.8 kV) ionization modes, and the data were obtained in a scan range of 50–600 m/z.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kumar, M. et al. Current research trends on emerging contaminants pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs): a comprehensive review. Sci. Total Environ. 859, 160031 (2023).

Rehman, M. U. et al. After effects of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) on the biosphere and their counteractive ways. Sep. Purif. Technol. 342, 126921 (2024).

Silori, R. et al. Global groundwater vulnerability for Pharmaceutical and Personal care products (PPCPs): the scenario of second decade of 21st century. J. Environ. Manag. 320, 115703 (2022).

Wu, P., Hu, T., Sun, L. & Fan, J. Efficient degradation of sulfadiazine by photosynthetic cyanobacteria Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 coupling with recombinant laccase strategy. Chem. Eng. J. 474, 145974 (2023).

Klein, E. Y. et al. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E3463–E3470 (2018).

Hu, Y., Zhu, Q., Wang, Y., Liao, C. & Jiang, G. A short review of human exposure to antibiotics based on urinary biomonitoring. Sci. Total Environ. 830, 154775 (2022).

Zeng, C. et al. Efficient degradation of sulfadiazine by UV-triggered electron transfer on oxalic acid-functionalized corn straw biochar for activating peroxyacetic acid: Performance, mechanism, and theoretical calculation. Bioresour. Technol. 407, 131103 (2024).

Mei, Z. et al. Biofilm enhanced the mitigations of antibiotics and resistome in sulfadiazine and trimethoprim co-contaminated soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 479, 135721 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. New insight into the adsorption of sulfadiazine on graphite-like biochars prepared at different pyrolytic temperatures. J. Clean. Prod. 413, 137468 (2023).

Xia, S. et al. Fabrication of magnetic nickel incorporated carbon nanofibers for superfast adsorption of sulfadiazine: performance and mechanisms exploration. J. Hazard. Mater. 423, 127219 (2022).

Ma, Y. et al. Exploring the influence of sulfadiazine-induced stress on antibiotic removal and transformation pathway using microalgae Chlorella sp. Environ. Res. 256, 119225 (2024).

Lin, H., Huang, L., Gao, Z., Lin, W. & Ren, Y. Comparative analysis of the removal and transformation of 10 typical pharmaceutical and personal care products in secondary treatment of sewage: a case study of two biological treatment processes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 107638 (2022).

Lou, J., An, J., Wang, X., Cheng, M. & Cui, Y. A novel DBD/VUV/PMS process for efficient sulfadiazine degradation in wastewater: singlet oxygen-dominated nonradical oxidation. J. Hazard. Mater. 461, 132650 (2024).

Li, J.-q. et al. Synergistically boosting sulfamerazine degradation via activation of peroxydisulfate by photocatalysis of Bi2O3-TiO2/PAC under visible light irradiation. Chem. Eng. J. 428, 132613 (2022).

Gul, I. et al. Unlocking the potential of multifunctional and highly porous Ti3C2/TiO2@Bi2O3 – based MXene: synergetic photocatalytic activation of peroxymonosulfate, hydrogen evolution and antimicrobial activity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 359, 124493 (2024).

Khan, I. et al. Heterogeneous photodegradation of industrial dyes: an insight to different mechanisms and rate affecting parameters. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 8, 104364 (2020).

Qin, F. et al. Photochemical transformation of sulfadiazine in UV/Fe(II)/sodium citrate Fenton-like system. J. Environ. Manag. 322, 116112 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Transformation of dissolved nitrogen under UV/H2O2: a review on composition, behavior and potential risk. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 113268 (2024).

Arora, I., Chawla, H., Chandra, A., Sagadevan, S. & Garg, S. Advances in the strategies for enhancing the photocatalytic activity of TiO2: conversion from UV-light active to visible-light active photocatalyst. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 143, 109700 (2022).

Guo, Y., Yan, C., Guo, Y. & Ji, X. UV-light promoted formation of boron nitride-fullerene composite and its photodegradation performance for antibiotics under visible light irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater. 410, 124628 (2021).

Hemmati-Eslamlu, P. & Habibi-Yangjeh, A. A review on impressive Z- and S-scheme photocatalysts composed of g-C3N4 for detoxification of antibiotics. FlatChem 43, 100597 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Recent advances in metal-free CDs/g-C3N4 photocatalysts: synthetic strategies, mechanism insight, and applications. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 150, 11–26 (2023).

Khan, I., Shah, T., Tariq, M. R., Ahmad, M. & Zhang, B. Understanding the toxicity of trinitrophenol and promising decontamination strategies for its neutralization: challenges and future perspectives. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 112720 (2024).

Khan, I., Rizwan Tariq, M., Ahmad, M., Khan, I. & Zhang, B. Strategically coupled tungsten oxide-zinc oxide photosystems for solar-driven nerve agent simulant degradation and hydrogen evolution. Sep. Purif. Technol. 354, 129078 (2025).

Xiang, X. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of sulfadiazine in suspensions of TiO2 nanosheets with exposed (001) facets. Chin. Chem. Lett. 32, 3215–3220 (2021).

Velmurugan, S., Yang, T. C. K., Chen, S.-W. & Chen, J.-N. Metal-organic frameworks derived ZnO-Co3O4 pn heterojunction photocatalyst for the photoelectrochemical detection of sulfadiazine. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 106169 (2021).

Di, G. et al. Visible-light degradation of sulfonamides by Z-scheme ZnO/g-C3N4 heterojunctions with amorphous Fe2O3 as electron mediator. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 538, 256–266 (2019).

Lyu, M. et al. Advances in modification of Bi2MoO6 and its photocatalysis: a review. J. Alloy. Compd. 982, 173759 (2024).

Jayan, G., Elias, L., Anil, A., Bhagya, T. C. & Shibli, S. M. A. Step-by-step tuning of morphology and band gap of ZnS/MoS2 photocatalyst for enhanced visible light to hydrogen fuel conversion. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 51, 1375–1386 (2024).

Jiang, Y. et al. A singlet oxygen dominated process through photocatalysis of CuS-modified MIL-101(Fe) assisted by peroxymonosulfate for efficient water disinfection. Chem. Eng. J. 439, 135788 (2022).

Ahmaruzzaman, M. & Gadore, V. MoS2 based nanocomposites: an excellent material for energy and environmental applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 105836 (2021).

Zhang, H., Wang, Z., Zhang, J. & Dai, K. Metal-sulfide-based heterojunction photocatalysts: principles, impact, applications, and in-situ characterization. Chin. J. Catal. 49, 42–67 (2023).

Sivaranjani, P. R., Janani, B., Thomas, A. M., Raju, L. L. & Khan, S. S. Recent development in MoS2-based nano-photocatalyst for the degradation of pharmaceutically active compounds. J. Clean. Prod. 352, 131506 (2022).

Chandra, P., Mohammad, A., Tripathi, B. & Yoon, T. Recent advancements in molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) and its functional nanostructures for photocatalytic and non-photocatalytic organic transformations. FlatChem 34, 100395 (2022).

Panchal, D., Sharma, A. & Pal, S. Engineered MoS2 nanostructures for improved photocatalytic applications in water treatment. Mater. Today Sustain. 21, 100264 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Modulating long-lived ultrafast charge carrier recombination in type-I MoS2/CdS photocatalyst achieving optimal H2 evolution. Sep. Purif. Technol. 355, 129664 (2025).

Cao, Y., Alsharif, S. & El-Shafay, A. S. Preparation, suppressed the charge carriers recombination, and improved photocatalytic performance of g-C3N4/MoS2 p-n heterojunction photocatalyst for tetracycline and dyes degradation upon visible light. Mat. Sci. Semicond. Proc. 144, 106569 (2022).

Hassan, H. M. u. et al. Reduce the recombination rate by facile synthesis of MoS2/g-C3N4 heterostructures as a solar light responsive catalyst for organic dye degradation. Diam. Relat. Mater. 140, 110420 (2023).

Lee, S. & Kim, J. Development of high-efficiency OER catalysts using YRO@MoS2 composite for enhanced energy conversion and storage. J. Power Sources 626, 235788 (2025).

Sridevi, R. et al. Facile construction of MoS2 decorated CdS hybrid heterojunction with enhanced hydrogen generation performance. Chem. Phys. Impact 8, 100584 (2024).

Tran, V.-T. & Chen, D.-H. CuS@MoS2 pn heterojunction photocatalyst integrating photothermal and piezoelectric enhancement effects for tetracycline degradation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 113158 (2024).

Tian, S. et al. S vacancies and heterojunction modulated MoS2/C@Fe3O4 towards improved full-spectrum photo-Fenton catalysis: Enhanced interfacial charge transfer and NIR absorption. Chem. Eng. J. 498, 155430 (2024).

Li, K. et al. Insulator in photocatalysis: essential roles and activation strategies. Chem. Eng. J. 426, 130772 (2021).

Dong, F. et al. Exploring the photocatalysis mechanism on insulators. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 219, 450–458 (2017).

Chen, Q. et al. Efficient photo-degradation of antibiotics by waste eggshells derived AgBr-CaCO3 heterostructure under visible light. Sep. Purif. Technol. 314, 123573 (2023).

Hao, Q. et al. A highly efficient g-C3N4/SiO2 heterojunction: the role of SiO2 in the enhancement of visible light photocatalytic activity. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 31410–31418 (2016).

Wang, H. et al. Visible light induced electron transfer from a semiconductor to an insulator enables efficient photocatalytic activity on insulator-based heterojunctions. Nanoscale 10, 15513–15520 (2018).

Cui, W. et al. Ba-vacancy induces semiconductor-like photocatalysis on insulator BaSO4. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 253, 293–299 (2019).

Ahmadzadeh, M., Mirzaei, M., Sabouri, Z. & Darroudi, M. Assessment of the photocatalytic performance and cytotoxic effects of barium sulfate nanoparticles synthesized with a one-step hydrothermal method. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 160, 111904 (2024).

Chen, Q., Zhou, H., Wang, J., Bi, J. & Dong, F. Activating earth-abundant insulator BaSO4 for visible-light induced degradation of tetracycline. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 307, 121182 (2022).

Umejuru, E. C. et al. Application of zeolite based nanocomposites for wastewater remediation: evaluating newer and environmentally benign approaches. Environ. Res. 231, 116073 (2023).

Torkian, N. et al. Synthesis and characterization of Ag-ion-exchanged zeolite/TiO2 nanocomposites for antibacterial applications and photocatalytic degradation of antibiotics. Environ. Res. 207, 112157 (2022).

Sousa, J. R. C. et al. Development of photocatalysts based on zeolite A with copper oxide (CuO) for application in the artificial photosynthesis process. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 110990 (2023).

Yue, Y. et al. Propane dehydrogenation catalyzed by single Lewis acid site in Sn-Beta zeolite. J. Catal. 395, 155–167 (2021).

Rathi, A., Barman, S., Basu, S. & Arya, R. K. Post-fabrication structural changes and enhanced photodegradation activity of semiconductors@zeolite composites towards noxious contaminants. Chemosphere 288, 132609 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. Fabricating ternary zeolite/g-C3N4/AgCl composites for accelerated tetracycline degradation. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 187, 111842 (2024).

Tang, J. et al. Decorating {0 0 1} TiO2 nanosheets on hydrophobic NaY zeolite: an efficient deactivation-resistant photocatalyst for gaseous toluene removal. Chem. Eng. J. 472, 144883 (2023).

Li, C. J. et al. Synthesis of fly ash cenospheres-based hollow ABW zeolite for dye removal via the coupling of adsorption and photocatalysis. Adv. Powder Technol. 32, 3436–3446 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Regulating superoxide radicals and light absorption ability for enhancing photocatalytic performance of MoS2@Z by CeO2 rich in adsorbed oxygen. J. Clean. Prod. 322, 129059 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. Interfacial oxygen vacancy modulated Ag3PO4 @MoS2 Z-scheme system for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen recovery from antibiotic wastewater. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 330, 122584 (2023).

Roy, S., Darabdhara, J. & Ahmaruzzaman, M. MoS2 Nanosheets@Metal organic framework nanocomposite for enhanced visible light degradation and reduction of hazardous organic contaminants. J. Clean. Prod. 430, 139517 (2023).

Liu, J., Lin, H., Dong, Y., He, Y. & Liu, C. MoS2 nanosheets loaded on collapsed structure zeolite as a hydrophilic and efficient photocatalyst for tetracycline degradation and synergistic mechanism. Chemosphere 287, 132211 (2022).

Chen, Y., Zhao, D., Sun, T., Cai, C. & Dong, Y. The preparation of MoS2/δ-FeOOH and degradation of RhB under visible light. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 110353 (2023).

Teng, W., Xu, J., Cui, Y. & Yu, J. Photoelectrocatalytic degradation of sulfadiazine by Ag3PO4/MoS2/TiO2 nanotube array electrode under visible light irradiation. Electroanal. Chem. 868, 114178 (2020).

Butler, M. A. Photoelectrolysis and physical properties of the semiconducting electrode WO2. J. Appl. Phys. 48, 1914–1920 (1977).

Chen, Y. et al. Lanthanum/titanium dioxide immobilized onto industrial waste with enhanced photocatalytic activity, and the degradation of dimethyl phthalate. J. Clean. Prod. 321, 129014 (2021).

Lv, Y. et al. Dimensionality-dependent MoS2 toward efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution: from synthesis to modifications in doping, surface and heterojunction engineering. Mater. Today Nano 18, 100191 (2022).

Wang, B. et al. Supramolecularly engineered S-scheme SubPc-Br/MoS2 photocatalyst nanosheets for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of antibiotics. Chem. Eng. J. 477, 147193 (2023).

Jhanjhariya, N. & Lata, S. Potential window optimization to upgrade the performance of the designed triad MoS2/MWCNT/PPy as an asymmetric supercapacitor device. J. Energy Storage 82, 110577 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Hu, L., Zhang, Y., Wang, X. & Wang, H. Snowflake-Like Cu2S/MoS2/Pt heterostructure with near infrared photothermal-enhanced electrocatalytic and photoelectrocatalytic hydrogen production. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 315, 121540 (2022).

Liu, X.-y. et al. Fabrication of Bi2O2(OH)NO3/g-C3N4 nanocomposites for efficient CO2 photocatalytic reduction. Colloids Surf. A 580, 123782 (2019).

Lu, Y. et al. Visible light-driven LaFeO3-biochar composites for removal of sulfamethoxazole by enhanced electron transfer coupled with peroxymonosulfate. Sep. Purif. Technol. 330, 125336 (2024).

Xu, G. et al. One-step solvothermal synthesis of wood flour carbon fiber/BiOBr composites for photocatalytic activation of peroxymonosulfate towards sulfadiazine degradation: mechanisms comparison between photo, chemical and photo-chemical oxidation processes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 297, 121399 (2022).

Li, X., Lang, M., Zhu, D., Niu, S. & Lyu, C. Tuning intramolecular charge transfer of covalent organic frameworks with triazine structure for enhanced peroxymonosulfate activation performance on the catalytic degradation of organic pollutants under visible light irradiation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 340, 126659 (2024).

Ling, C. et al. Sulfide-modified zero-valent iron activated periodate for sulfadiazine removal: performance and dominant routine of reactive species production. Water Res. 220, 118676 (2022).

Liu, X., Chang, F., Zhang, D. & Ren, M. Influence of nitrate/nitrite on the degradation and transformation of triclosan in the UV based disinfection. Chemosphere 298, 134258 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Insights into periodate oxidation of antibiotics mediated by visible-light-induced polymeric carbon nitride: performance and mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 457, 141147 (2023).

Liu, C. et al. Construction of Ag/MoS2@Fe-CS aerogel as excellent PMS activator via synergistic photocatalysis and photothermal effects. Chem. Eng. J. 455, 140814 (2023).

Pearson, R. G. Absolute electronegativity and hardness: application to inorganic chemistry. Inorg. Chem. 27, 734–740 (1988).

Praus, P. On electronegativity of graphitic carbon nitride. Carbon 172, 729–732 (2021).

Shtarev, D. S., Blokh, A. I., Nashchochin, E. O. & Shtareva, A. V. The dependence of the conduction band edge of the alkali earth metal bismuthates on their composition. Opt. Quantum Electron. 50, 228 (2018).

Alotaibi, M. R., Shawky, A. & Zaki, Z. I. Mesoporous MoS2 incorporated zirconia nanocomposites: simple synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic desulfurization of thiophene under visible light. Ceram. Int. 48, 36697–36705 (2022).

Lai, M. T. L. et al. Highly effective interlayer expanded MoS2 coupled with Bi2WO6 as p-n heterojunction photocatalyst for photodegradation of organic dye under LED white light. J. Alloy. Compd. 953, 169834 (2023).

Tao, R. et al. Discrete heterojunction nanofibers of BiFeO3/Bi2WO6: novel architecture for effective charge separation and enhanced photocatalytic performance. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 572, 257–268 (2020).

Wang, J., Zhang, G., Li, J. & Wang, K. Novel three-dimensional flowerlike BiOBr/Bi2SiO5 p–n heterostructured nanocomposite for degradation of tetracycline: enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity and mechanism. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 14221–14229 (2018).

Wang, K., Zhang, G., Li, J., Li, Y. & Wu, X. 0D/2D Z-scheme heterojunctions of bismuth tantalate quantum dots/ultrathin g-C3N4 nanosheets for highly efficient visible light photocatalytic degradation of antibiotics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 43704–43715 (2017).

Mafa, P. J., Malefane, M. E., Opoku, F., Mamba, B. B. & Kuvarega, A. T. Visible light responsive MoS2/Ag@WO3/EG photoanode with highly stable Z-scheme induced circular electron motion pioneered by exfoliated graphite for bisphenol a photoelectrodegradation. Chem. Eng. J. 464, 142462 (2023).

Zhang, H., Liu, C., Wang, Y., Jia, F. & Song, S. Construction of 3D-sized Mn (II)-doped MoS2@activated alumina beads as PMS activator for tetracycline degradation under light irradiation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 806, 139996 (2022).

Sun, H. et al. Refractory organics removal in PMS and H2O2/PMS oxidation system activated by biochar/nZVI/MoS2 composite: synthesis, performance, mechanism and dosing methods. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 109134 (2023).

Yan, Z. et al. Enhanced Fe(III)/PMS system by flower-like MoS2 nanosheet for rapid degradation of tetracycline. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 108860 (2022).

Xie, X. et al. High-efficiency destruction of aromatic VOC mixtures in a MoS2 cocatalytic Fe3+/PMS reaction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 305, 122444 (2023).

Tang, J. et al. High efficient PMS activation by synergistic effects of bimetallic sulfide FeS2@MoS2 for rapid OFX degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 475, 146023 (2023).

Gu, J., Yin, P., Chen, Y., Zhu, H. & Wang, R. A natural manganese ore as a heterogeneous catalyst to effectively activate peroxymonosulfate to oxidize organic pollutants. Chin. Chem. Lett. 33, 4792–4797 (2022).

Tan, F. B., Karadirek, Ş., Tuna, Ö. & Simsek, E. B. Anchoring of tungsten on g-C3N4 layers towards efficient photocatalytic degradation of sulfadiazine via peroxymonosulfate activation. Diam. Relat. Mater. 152, 111939 (2025).

Ullah, R. et al. Mn-MOF derived N-doped MnOx@carbon heterogeneous catalysts for Vis-light, S2O82-, HSO5, Vis/S2O82-, and Vis/HSO5- induced degradation of metronidazole: kinetics and mechanistic study. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 113331 (2024).

Wang, M. et al. Cu doped Fe2O3 growing a nickel foam for sulfadiazine degradation in peroxymonosulfate assisting photo-electrochemical system: performance, mechanism and degradation pathway. Chem. Eng. J. 466, 143013 (2023).

Zhang, B. et al. BiOBr/MoS2 catalyst as heterogenous peroxymonosulfate activator toward organic pollutant removal: energy band alignment and mechanism insight. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 594, 635–649 (2021).

Dong, C. et al. Singlet oxygen triggered by robust bimetallic MoFe/TiO2 nanospheres of highly efficacy in solar-light-driven peroxymonosulfate activation for organic pollutants removal. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 286, 119930 (2021).

Zhu, L., Shi, Z., Deng, L. & Duan, Y. Efficient degradation of sulfadiazine using magnetically recoverable MnFe2O4/δ-MnO2 hybrid as a heterogeneous catalyst of peroxymonosulfate. Colloids Surf. A 609, 125637 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the funding support from the Guiding Plan of Sichuan for the Transfer and Transformation of Scientific and Technological Achievements (24ZHSF0062). The authors would like to thank Ceshigo Research Service (www.ceshigo.com) for the XRD analysis and Shiyanjia Lab (www.shiyanjia.com) for the ESR analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to this study. Yi Chen: Methodology, Writing-original draft, Funding acquisition, Supervision. Yue Jin: Investigation. Honglin Zhu: Investigation, Formal analysis. Haolan Zhang: Investigation. Luyu Wei: Validation. Yan Tang: Validation. Rui Wang: Resources. Dayu Zhou: Validation. Jinchuan Gu: Resources, Methodology, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Jin, Y., Zhu, H. et al. Novel MoS2/BaSO4/zeolite heterostructure composite for the enhanced visible-light photocatalytic degradation of sulfadiazine. npj Clean Water 8, 21 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00455-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00455-5