Abstract

While self-cycled Fenton (SC-Fenton) systems represent an innovative advancement in water purification technologies, their practical implementation remains constrained by inefficient in situ H2O2 generation. To address this limitation, we developed a mechano-driven contact-electro-catalysis (CEC) platform employing fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) as a triboelectric catalyst. Under ultrasound irradiation, this system achieves an exceptional H2O2 generation rate of 7.67 mmol·gcat–1·h–1, outperforming conventional piezo-catalysis systems. Mechanistic studies reveal that a built interfacial electric field generated on the FEP surface effectively reduces the free energy for the indirect 2e– water oxidation pathway. This unique characteristic promotes the generation of interfacial hydroxyl radical (*OH) and enhances its subsequent recombination into H2O2. The strategic integration of FeIII as a catalytic initiator with the CEC system enables the establishment of SC-Fenton reaction (FeIII/FEP/CEC). Notably, the contact-electrification electrons accumulated on the FEP interface drive efficient FeIII/FeII redox cycling, achieving a remarkable degradation rate for sulfadiazine at 0.125 min–1. This enhanced catalytic performance stems from FeIII-mediated amplification of dissociative hydroxyl radical (•OH) generation. This study provides fundamental insights into the underlying mechanisms of CEC-mediated FeIII-initiated SC-Fenton reaction, offering new possibilities for sustainable water purification processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

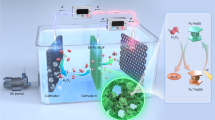

Fenton technology is widely recognized as a well-established method for wastewater remediation, leveraging reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated through the catalytic interplay between hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and FeII to degrade pollutants1. However, persistent challenges including continuous H2O2 consumption and sluggish FeII regeneration from FeIII reduction have constrained the advancement of conventional Fenton processes2,3,4. To address these limitations, the concept of self-cycled Fenton (SC-Fenton) systems has emerged, designed to concurrently regenerate FeII and synthesize H2O2 within an integrated redox framework. These closed-loop systems enable sustained pollutant degradation while minimizing reagent replenishment, attracting considerable research interest in sustainable water treatment5. Early implementations of SC-Fenton systems primarily integrated photocatalytic or piezocatalytic mechanisms with FeIII activation6,7. Theses hybrid architectures leverage photo/piezocatalytic effects to achieve charge carrier (electron (e–) and hole (h+)) separation, wherein the generated e– concurrently participate in two critical processes: (1) oxygen reduction to H2O2 (ORR-H2O2, Eqs. 1), and (2) FeIII reduction to FeII. The regenerated FeII subsequently reacts with in situ formed H2O2 to perpetuate the Fenton cycle8,9. However, such configurations suffer from two inherent limitations that constrain catalytic efficiency: First, competitive e– consumption between ORR-H2O2 and FeIII reduction creates a kinetic bottleneck, diminishing the availability of e– for either pathway. Second, the ORR-H2O2 process exhibits intrinsically low yield due to limited dissolved oxygen concentrations in wastewater matrices, imposing fundamental constraints on system scalability10. These interdependent challenges–e– pathway competition and oxygen-dependent H2O2 synthesis–collectively restrict the performance of FeIII-mediated photo/piezocatalysis-driven SC-Fenton (Fig. 1a).

The water oxidation reaction (WOR-H2O2) has emerged as a promising alternative pathway for H2O2 production, offering distinct advantages over ORR-H2O2. First, WOR-H2O2 utilizes ubiquitous H2O as the H and O source while circumventing the oxygen-dependent constraints inherent to ORR-H2O211,12. Second, this oxidative pathway operates through hole (h+)-mediated oxidation processes, thereby eliminating e– competition with parallel FeIII reduction reactions13,14. Third, FeIII reduction and WOR reactions exhibit synergistic interdependency, mutually enhancing reaction kinetics15. However, compared to the dominant 4e– WOR pathway for O2 evolution (Eq. 2), the 2e– WOR pathway (direct/indirect routes; Eqs. 3–5) requires a higher thermodynamic overpotential, imposing significant energy barriers for most catalytic systems16,17. This energy penalty currently limits H2O2 yield via the 2e– WOR process, underscoring the need for advanced catalyst engineering to optimize reaction energetics.

2e– ORR

4e– WOR

Direct 2e– WOR

Indirect 2e− WOR

Overcoming the energy barrier of the 2e– WOR could unlock the full potential of WOR-H2O2 for the SC-Fenton system18. Recent advances highlight in situ formed interfacial electric field (IEF) as transformative tools for modulating reaction energetics. For example, in a piezo-photocatalysis system, non-centrosymmetric semiconductors generate IEF via mechanical stress, which lowers the activation energy for 2e– WOR through lattice polarization18. Analogously, the contact-electrification (CE) effect within the contact-electro-catalysis (CEC) system leverages solid-liquid CE to establish IEF at interfaces. During solid-liquid interactions, the electron transfer driven by electron clouds overlapping creates electron accumulation on fluorocarbon polymers (FCPs)19. These accumulated electrons establish intense built-in IEF (up to ~100 V) that dissociate interfacial water molecules into hydrated electrons and interfacial hydroxyl radical (*OH), followed by *OH recombination into H2O220,21,22. While prior studies confirm CEC’s capacity for H2O2 accumulation23,24, critical knowledge gaps persist regarding: (i) thermodynamic optimization of H2O decomposition and *OH recombination; and (ii) charge transfer dynamics at interfaces. Charged FCPs exhibit unique charge reservoir behavior, where surface-trapped electrons facilitate cation reduction under IEF guidance25,26,27. These properties suggests that the CEC system exhibits dual functional advantages for FeIII-based SC-Fenton applications (Fig. 1b): (i) concurrent facilitation of FeIII reduction and WOR-H2O2 through distinct e– transfer pathway, effectively eliminating inter-pathway e– competition; and (ii) enhanced H2O2 production efficiency via IEF-optimized WOR-H2O2 mechanisms. This functional synergy addresses two critical limitations of conventional systems by decoupling oxidative and reductive processes while amplifying H2O2 yield. To fully elucidate the underlying mechanisms, three fundamental questions require systematic resolution: (i) the interfacial electron transfer dynamics governing FeIII/FeII conversion; (ii) IFE-mediated radical generation efficiency; and (iii) kinetic coupling mechanisms between oxidative (H2O2 accumulation) and reductive (FeII regeneration) processes.

In this study, a high-performance SC-Fenton system was developed, which synergized FCPs-based CEC (FCPs/CEC) with homogeneous FeIII activation. The FCPs/CEC platform achieved an exceptional H2O2 generation rate of 7.67 mmol·gcat–1·h–1 through IEF-mediated indirect 2e– WOR, where the IEF reduced the thermodynamic barrier for *OH formation and subsequent H2O2 generation. Upon FeIII integration, the resulting SC-Fenton system (FeIII/FCPs/CEC) exhibited amplified generation of dissociative hydroxyl radical (•OH) via Fenton chain reactions, leading to improved pollutant degradation kinetics compared to both FCPs/CEC and FeII/FCPs/CEC systems. In addition, the catalytic degradation capability of the FeIII/FCPs/CEC remained robust during reuse and in complex water matrices. This study provides fundamental insights into the CEC-enabled SC-Fenton paradigm, demonstrating how triboelectric fields can concurrently address H2O2 synthesis and FeIII activation bottlenecks.

Results

Efficient H2O2 generation of FCPs/CEC

The contact-electro-catalytic activity of FCPs/CEC for H2O2 generation was assessed under ultrasound irradiation (40 kHz, 110 W) of DI water with different FCPs at a dosage of 0.1 g·L–1. The H2O2 concentration was quantitatively calculated by the standard curve in Supplementary Fig. 1. Figure 2a illustrated that the accumulated H2O2 yield was 0.76, 0.54, and 0.03 mM for FEP, PTFE, and PVDF/CEC within 60 min, respectively, with all of their generation rates adhering to zero-order kinetics. Evidently, the H2O2 generation was driven by the FCPs/CEC process, as negligible H2O2 accumulation was observed without the introduction of FCPs (Supplementary Fig. 2). Remarkably, H2O2 accumulation showed a direct positive correlation with –F density (F/C atomic ratio on the main chain) across FCPs (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3a), establishing –F density as a critical factor governing CE capacity through enhanced electron transfer efficiency and reduced activation barriers in FCPs/CEC systems28. Moreover, quantitative characterization of interfacial electron transfer revealed distinct CE capabilities: FEP demonstrated superior charge accumulation (20.3 nC), followed by PTFE (13.7 nC) and PVDF (2.7 nC) during aqueous contact (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Consistent with this trend, CE performance showed F-dependent enhancement (Supplementary Fig. 3c), conclusively demonstrating that –F density dictates electron-withdrawing capacity in FCP architectures. This implied that utilizing FCPs with higher CE ability enhanced H2O2 generation in FCPs/CEC, with FEP currently being identified as the optimal CEC catalyst for this purpose. Therefore, in this investigation, FEP/CEC demonstrated an exceptional normalized H2O2 generation rate of 7.67 mmol·gcat–1·h–1, surpassing the performance of cutting-edge particle H2O2 catalysts by 2–126 times (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 2), including C3N5, Bi12O17Cl12, and BiOIO3, etc. in the piezo-catalysis systems9,15,29,30,31,32,33,34,35.

Time course of the H2O2 generation by FCP/CEC with different FCPs (a). Comparison of the H2O2 generation rate with previous CEC and piezo-catalysis (b). Time course of the H2O2 generation measured under different reaction conditions (c). Relative quantitative analysis of *OH in FCP/CEC (d). Free energy profiles of the indirect 2e– WOR process in FCP/CEC were compared with (FCP-IEF) and without IEF (FCP-Normal) (e). Schemic of H2O2 generation in FCPs/CEC (f). Experimental conditions: [FCPs]0 = 0.1 g·L–1, T = 25 ± 2 °C.

To elucidate the mechanisms behind the remarkable rate of H2O2 generation in FCPs/CEC, the potential ORR and WOR processes were examined individually36. This investigation began by exploring the H2O2 yield under ambient and anoxic aqueous conditions. The results, as depicted in Fig. 2c, revealed a slight decrease in H2O2 production when dissolved oxygen was expelled by N2, indicating that the 2e– ORR pathway made only a modest contribution to H2O2 generation in FCPs/CEC. These results suggested that the primary pathway for H2O2 generation in FCPs/CEC was the WOR process. Subsequently, the specific types of WOR reactions were further elucidated. One established method to differentiate between direct and indirect 2e– WOR processes is by detecting intermediated *OH18. Notably, a significant reduction in H2O2 generation (only 0.25 mM) was observed upon the addition of tert-butyl alcohol (TBA, 200 mM) as the scavenger of *OH (Fig. 2c), indicating the pivotal role of intermediated *OH in the evolution of H2O2 in FCPs/CEC18. Moreover, the presence of the quadruplet DMPO-*OH signals and fluorescent peaks in Fig. 2d confirmed the generation of *OH in FCPs/CEC. The intensity of both electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signals and fluorescent peaks correlated with the accumulated H2O2 yield in the order of FEP > PTFE > PVDF, suggesting that the generation of *OH was ascribed to induced electron exchanges between the FCP-H2O interface during frequent contact/separation. These results pointed towards the indirect 2e– WOR process as the primary pathway for H2O2 evolution.

The intricate pathway underlying the indirect 2e– WOR process for H2O2 generation in FCPs/CEC was unveiled through meticulous DFT calculations (without and with IEF), shedding light on the activation energy dynamics. The interfacial interaction between FCPs and H2O constitutes the fundamental initiation step of CEC. To quantify this critical interfacial process, we systematically calculated adsorption energies for FCP–H2O systems. As shown in Supplementary Table 3, FEP exhibited the highest H2O adsorption affinity among the evaluated FCPs, a phenomenon directly attributable to its superior electron-withdrawing capacity derived from higher –F density. This computational assessment reveals that enhanced electron-withdrawing characteristics in FCPs significantly facilitate interfacial charge transfer processes by strengthening molecular-level interactions at the FCP–H2O interface. The observed hierarchy in adsorption energy aligns precisely with the FCPs’ –F density and corresponding electronic properties, establishing a quantitative structure-activity relationship central to CEC modulation. Furthermore, computational models incorporating 7 H2O molecules were employed to simulate FCP–H2O interfacial interactions, with a superimposed 0.3 V/Å IEF replicating localized high-intensity electrochemical conditions (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 4). Comparative analysis revealed a pronounced IEF catalytic effect: the activation energies for *OH generation substantially decreased across systems–from 0.37 to 0.18 eV (FEP/CEC), 0.72 to 0.44 eV (PTFE/CEC), and 0.92 to 0.57 eV (PVDF/CEC)–indicating enhanced thermodynamic preference for the indirect 2e– WOR pathway under IEF, thereby promoting H2O2 accumulation. Non-bonding interaction at the FCP–H2O interface facilitated unimpeded diffusion of both H2O molecules and intermediated *OH around FEP, increasing interfacial contact frequency and subsequent *OH recombination37. Notably, the inverse correlation between activation energy hierarchy (FEP < PTFE < PVDF) and CE capacity arose from F-mediated electron accumulation–FCPs with superior CE ability exhibited amplified surface electron density due to strong electron-withdrawing –F groups (Supplementary Fig. 3), which intensified IEF strength and consequently reduced energy barriers for indirect 2e– WOR pathway38. Although the piezo-effect could induce an IEF under ultrasound, the induced IEF was comparably weaker than that of CEC, as evidenced by the lower output voltage of piezoelectric nanogenerators (~3.2 V) in contrast to triboelectric nanogenerators (~130 V)39,40,41. This discrepancy highlighted the increased difficulty and reaction barriers in radical formation during piezo-catalysis compared to CEC. Alternatively, the higher energy barrier toward indirect 2e– WOR was needed to be overcome for piezo-catalysis than that of CEC, which exactly explained that the indirect 2e– WOR cannot be achieved by piezo-catalysis but can be accomplished by CEC. Besides, the outstanding H2O2 generation rate of CEC via indirect 2e– WOR was significantly higher than that of piezo-catalysis via 2e– ORR in Fig. 2b, implying the superior advantage of WOR over ORR for H2O2 evolution due to the IEF induced by CE effect.

The detailed H2O2 evolution process in FCPs/CEC as depicted in Fig. 2f. The overlap of electron clouds between the F atom (FCPs) and the O atom (H2O) upon contact under ultrasonic excitation lowered the potential barrier42, resulting in the transfer of electrons from H2O to FCP, driven by the exceptional electron-withdrawing capacity of F and reduced electron transfer barriers under ultrasound28. After being separated, the transferred electrons remained as static charges and accumulated on the FCP surface, ultimately yielding H2O•+and FCP* (Eqs. 6–7). Immediately, the H2O•+ reacted with neighboring H2O and ultimately combining to form H3O+ and *OH (Eq. 8). Simultaneously, the accumulated electrons on FCPs surface induced an IEF, thereby facilitating the indirect 2e– WOR processes by lowering the activation energy barrier and subsequently promoting the recombination of *OH into H2O2 (Eq. 5). The sustained reducing activity of FCP, due to the accumulated surface electrons, facilitated the conversion of O2 to O2•–, further contributing to H2O2 evolution pathways (Eqs. 9–12)43. Reports indicated that the free radicals tended to react with each other rather than disperse in the solution due to the Grotthuss mechanism through the hydrogen bond network of water in FCP/CEC23. Furthermore, considering the excellent electron gain/loss ability of unpaired electrons in *OH, the F within FCP, renowned for their superb electron-withdrawing capacity, were anticipated to interact with *OH, concentrating *OH around the FCP interface, and promoting their chances of recombination into H2O244. In conclusion, the enhanced formation and recombination of *OH ultimately led to the heightened generation of H2O2 in FCP/CEC, showcasing the significant role of IEF induced by the CE effect in this intricate catalytic process.

The FEP/CEC demonstrated a consistent ability to generate H2O2 across a broad pH range from 2.6 to 9.6 (Supplementary Fig. 5). This wide operational pH range highlighted its versatility and potential to adapt to diverse pH conditions commonly found in wastewater treatment scenarios. Furthermore, the steady accumulation of H2O2 within FEP/CEC over a 4 h period indicated the stability of the chemically inert FEP during the H2O2 evolution process (Supplementary Fig. 6). The impact of various anions such as Cl–, SO42–, and HPO42– on H2O2 yield was minimal, suggesting their limited interference with H2O2 production in FEP/CEC (Supplementary Fig. 7). However, the addition of CO32– notably inhibited H2O2 production in FEP/CEC, leading to a 62.33% decrease. This inhibitory effect could be attributed to the ions shielding effect, resulting in compromised electron transfer, or the interaction between CO32– and *OH10. Notably, these two inhibitory effects were not observed in the presence of other anions. The distinct influence of CO32– on H2O2 production in FEP/CEC warrants further exploration in future research to elucidate the underlying mechanisms responsible for this phenomenon. Based on the aforementioned results, the FEP/CEC exhibited the advantages of remarkable and stable H2O2 accumulation, meeting the prerequisites for achieving the SC-Fenton system.

Water purification by FeIII/FEP/CEC SC-Fenton system

In the pursuit of water purification efficacy utilizing the FeIII/FEP/CEC SC-Fenton system, a detailed investigation into its catalytic degradation process was undertaken using SDZ as the model pollutant. Supplementary Fig. 8 illustrates that ultrasound alone (US) and FeIII/US both exhibited minimal impact on SDZ degradation. Notably, FEP/CEC accomplished 68.59% of SDZ removal with an accumulation of 0.62 mM H2O2 (Supplementary Fig. 9). This outcome aligned with the observation that *OH tended to react with each other, generating H2O2 instead of directly attacking SDZ. This behavior was not only ascribed to the interaction between *OH and FCP, but also due to the higher reactivity of 2 *OH (k(*OH/*OH) = 5.2 × 109 M–1·s–1) with each other compared to SDZ (k(*OH/SDZ) = 1.9 × 109 M–1·s–1)10, leading to H2O2 accumulation through *OH recombination, even in the presence of SDZ. This suggested that *OH via CEC primarily engaged in the recombined reaction, forming H2O2 rather than catalytic degradation. Exploring the utilization of generated H2O2 was deemed crucial to enhance the catalytic degradation capability of CEC. The ineffectiveness of SDZ degradation in H2O2/US ruled out the potential of ultrasound in activating H2O2 for pollutant removal (Supplementary Fig. 10). Given that the Fenton reaction, known for decomposing H2O2 via iron regent, is widely employed, FeIII homogeneous reagent (FeCl3 of 1.0 mM) was introduced to initiate the SC-Fenton (FeIII/FEP/CEC). The concentration of H2O2 was very low in FeIII/FCP/CEC, demonstrating that the generated H2O2 via FCP/CEC process was consumed in the presence of FeIII, further suggesting the existence of SC-Fenton process in the FeIII/FCP/CEC (Supplementary Fig. 9). Figure 3a showcased that the SDZ removal rate of FeIII/FEP/CEC (0.125 min–1) was 5.43-fold of that in FEP/CEC (0.023 min–1), highlighting the enhanced catalytic degradation effect of SC-Fenton. Furthermore, the FeIII as the iron source demonstrated superior degradation performance (2.30-fold) compared to FeII, in line with previous reported self-cycled Fenton systems15,45. Moreover, the total organic carbon (TOC) removal profiles observed in all three systems exhibited strong correlations with their SDZ degradation efficiencies (Supplementary Fig. 11), confirming that the FeIII/FEP/CEC achieved not only unparalleled degradation kinetics but also superior mineralization efficiency. Additional SC-Fenton systems were constructed with PTFE and PVDF as CEC catalysts, leading to significant enhancements in degradation efficiency (2.68–4.28 times) and reaction rates compared to their respective control groups (Fig. 3b). These findings suggested that FeIII/FCP/CEC SC-Fenton can be tailored by incorporating various FCPs as CEC catalysts. Moreover, the efficient removal of other pollutants (PE, CBZ, and ATR) with diverse molecular structures were also achieved by FeIII/FEP/CEC (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, FeIII/FEP/CEC exhibited better degradation performance than that of previous piezo- and photo-catalysis induced SC-Fenton systems (Supplementary Table 4). Consequently, FeIII/FCP/CEC exhibited remarkable catalytic oxidation capacity for water purification.

The pseudo-first order kobs of SDZ degradation by FeIII/FEP/CEC, FeII/FEP/CEC, and FEP/CEC (a). The SDZ degradation efficiency and pseudo-first order kobs of FCP/CEC and FeIII/FCP/CEC (b). The comparison of pseudo-first-order kobs of different pollutants by FeIII/FEP/CEC (c). Experimental conditions: [FCPs]0 = 0.1 g·L–1, [FeIII] = 1 mM, [Pollutant] = 5 mg·L–1, T = 25 ± 2 °C.

The pH value was a pivotal factor influencing traditional Fenton and Fenton-like catalytic degradation performance46,47. As shown in Fig. 4a, there were minimal differences in SDZ degradation rate in FeIII/FEP/CEC across a range of initial pH values (3.6 to 9.6), indicating its robust degradation capacity without requiring pH adjustment. In fact, the introduction of FeCl3 triggered a pronounced pH decrease (Supplementary Fig. 12), a phenomenon governed by Fe³⁺ hydrolysis that simultaneously imparts Lewis acidity and enhances solution’s acidity48,49,50. This autogenous acidification serves dual functions: it prevents iron precipitation through pH modulation while inherently addressing the solubility challenges of conventional Fenton processes. Remarkably, the FeIII/FEP/CEC system maintains stable iron dispersion even in alkaline wastewater matrices (initial pH >7.0), demonstrating exceptional operational pH flexibility. By leveraging FeCl3’s intrinsic hydrolytic properties, the system circumvents the need for external acid supplementation-a critical limitation in traditional Fenton processes-thereby achieving self-regulated iron solubility across diverse pH conditions. The SDZ degradation rate increased along with the dosage of FeIII, elevating from 0.1 to 2.0 mM (Fig. 4b). Additionally, the FeIII/FEP/CEC demonstrated its catalytic stability after five cycles (Supplementary Fig. 13). Structural and compositional analysis of FCPs through pre- and post-reaction characterization confirmed the absence of detectable morphological alterations or chemical modifications following multiple reuse cycles under ultrasonication (Fig. 4c, d and Supplementary Figs. 14–16). This exceptional stability highlights the inherent durability of FCPs, consistent with their documented chemical inertness and resistance to structural degradation under operational conditions43. The preservation of both physical architecture and molecular integrity across reaction cycles substantiates FCPs’ reliability as robust catalysts in sustained catalytic applications. Despite the slight inhibition of common anions on degradation performance due to their impact on H2O2 yield and the scavenging role on ROS (Supplementary Fig. 17), the FeIII/FEP/CEC maintained commendable performance in water purification endeavors.

Mechanism of FeIII/FEP/CEC SC-Fenton system

In the FEP/CEC system, interfacial *OH recombine to form H2O2, while in the FeIII/FEP/CEC-based SC-Fenton configurations, H2O2 undergoes catalytic decomposition to generate dissociative •OH, responsible for contaminant breakdown. To systematically evaluate catalytic performance, we specifically analysed •OH production through the FeIII-mediated Fenton reaction as the primary descriptor of pollutant degradation efficiency. This distinction between *OH (H2O2 precursor) and Fenton-generated •OH (pollutant degradation) was displayed in Table 1 to clarify their respective roles. Isopropanol (IPA) known as a scavenger for •OH (k(•OH/IPA) = 1.6 × 1010 M–1·s–1)51, was introduced into FEP/CEC and FeIII/FEP/CEC to assess the role of •OH in SDZ degradation. As depicted in Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 18, the addition of IPA (100 mM) effectively halted the oxidation of SDZ in both FEP/CEC and FeIII/FEP/CEC, indicating the crucial involvement of •OH in these systems. Additionally, O2•− also contributed to catalytic degradation, as evidenced by a decrease in removal efficiency of 23.2 and 65.1% in FEP/CEC and FeIII/FEP/CEC, respectively, in the presence of p-BQ (k(O2• − /p-BQ) = 0.9 × 109 M–1·s–1)52. The marginal inhibition by β-carotene suggested the participation of 1O2 in SDZ remediation. To verify potential high-valent iron species formation, we employed methyl phenyl sulfoxide (PMSO) as a probe (k(FeIV/PMSO) = 1.23 × 105 M–1·s–1) in FeIII/FCP/CEC systems53. The complete absence of methyl phenyl sulfone (PMSO2) generation during SDZ degradation conclusively demonstrates the non-participation of FeIV intermediates in these catalytic processes (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 19). These selective ROS screening tests underscored the pivotal role of •OH in SDZ degradation, followed by O2•− and 1O2, in both FeIII/FEP/CEC and FEP/CEC. This evidence aligns with the system’s exclusive •OH-mediated degradation mechanism, reaffirming the dominance of SC-Fenton chemistry over alternative high-valent iron pathways under the investigated conditions. To elucidate the enhanced degradation performance of FCPs/CEC and FeIII/FCPs/CEC, the yield of •OH, a critical descriptor, was further investigated. Firstly, the relative intensity of DMPO-•OH in FeIII/FEP/CEC surpassed that of FEP/CEC, indicating that FeIII expedited •OH production (Fig. 5c). Secondly, the catalytic enhancement of FeIII on •OH yield was further analyzed. As shown in Fig. 5d, both FEP/CEC and FeIII/FEP/CEC exhibited time-dependent intensification of fluorescent peaks corresponding to •OH accumulation. Notably, the FeIII-modified system showed enhanced fluorescent signals compared to its FeIII-free counterpart at equivalent reaction intervals. Consistent with these observations, parallel experiments in PTFE- and PVDF-based systems revealed analogous FeIII-mediated amplification of •OH yield (Supplementary Fig. 19), demonstrating the universal catalytic capacity of FeIII to amplify •OH generation across all FCP/CEC configurations in the SC-Fenton system. These systematic comparisons establish dual functionality of FeIII as both an electron transfer mediator and radical production accelerator through facilitated interfacial redox cycling.

The inhibited effect from different scavengers on SDZ degradation performance in FeIII/FEP/CEC (a). The PMSO consumption and PMSO2 formation in FeIII/FEP/CEC over time (b). The EPR signals of DMPO-•OH of FEP/CEC and FeIII/FEP/CEC (c). The self-quantitative analysis of •OH yield in FEP/CEC and FeIII/FEP/CEC (d). Experimental conditions: [FCPs]0 = 0.1 g·L–1, [FeIII] = 1 mM, T = 25 ± 2 °C.

The higher •OH generation in FeIII/FEP/CEC was potentially attributed to the generated FeII triggering the Fenton process by activating H2O2. Consequently, the reduction regime of FeIII into FeII in FEP/CEC was further elucidated. The concentrations of Fe species (FeIII and FeII) in FEP/CEC were shown in Fig. 6a, b according to the 1,10-phenanthroline spectrophotometry based on the absorbance of orange-red product between FeII and 1,10-phenanthroline (details in Supplementary Note 1.1). Quantitative analysis revealed that the content of FeIII remained constant at close to 100% without detectable FeII accumulation during the reaction. This absence of FeII species originates from immediate Fenton consumption of nascent FeII by continuously generated H2O2. Consequently, in ex situ chemical analysis using 1,10-phenanthroline, FeII remained undetectable due to its instantaneous reaction with H2O2 prior to sampling. To resolve this detection limitation, an in situ chemical analysis was implemented by introducing 1,10-phenanthroline directly into the FeIII/FCP/CEC system, enabling real-time sequestration of transient FeII species (details in Supplementary Note 1.2 and Supplementary Fig. 20)15. As shown in Fig. 6c, the gradually increasing concentration of FeII in FeIII/FCP/CEC indicated the existence of fresh FeII as the reducing intermediate of FeIII, suggesting a rapid cycling process between FeIII and FeII. The reduction of FeIII into FeII was likely facilitated by the reductive CE electrons. Previous studies have indicated that CE electrons were able to reduce various high-valent metal ions to low-valent states in an aqueous solution, with reduction potentials ranging from 0.643 to 1.156 V vs. SHE25. The reduction potential of the FeIII/FeII process (FeIII + e– → FeII) was 0.77 V vs. SHE, which was supposed to be achieved in FEP/CEC. Furthermore, the in situ quantitative results revealed that the accumulation of fresh FeII followed the order of FEP > PTFE > PVDF (Fig. 6c), aligning with the available contact charge amount of the three FCPs. The addition of AgNO3 as the electron scavenger further inhibited the accumulation of fresh FeII, demonstrating the role of CE electrons in the reduction and transformation from FeIII to FeII. The electron transfer process between FEP and FeIII was corroborated by the electrochemical method. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 21, the addition of FeIII increased the potential, indicating electron transfer from FEP to FeIII 15,54. Additionally, the built IEF via accumulated electrons on the FCP surface attracted the FeIII ions due to the electrostatic induction, facilitating the electron transfer from the FCP surface to FeIII. Thus, the FeII was generated via the FeIII reduction by CE (Eq. 13).

The concentration changes of FeII and FeIII overtime in FeIII/FEP/CEC by ex situ 1,10-phenanthroline method (a). The schematic of detection procedures for FeII and FeIII overtime in FeIII/FEP/CEC by ex situ and in situ 1,10-phenanthroline methods (b). The real-time FeII concentration dynamics in FeIII/FEP/CEC by in situ 1,10-phenanthroline method (c). Experimental conditions: [FCPs]0 = 0.1 g·L–1, [FeIII] = 1 mM, T = 25 ± 2 °C.

While FeIII generated through the Fenton reaction in the FeII/FEP/CEC (Eq. 14) was reduced to FeII via CE electrons55, a critical operational distinction arises: the FeII/FEP/CEC system starts with preloaded FeII, whereas H2O2 accumulates progressively during the reaction. This stoichiometric mismatch creates an excess of FeII relative to H2O2 availability, triggering parasitic •OH quenching through FeII–•OH interactions (Eq. 15)56, which diminishes oxidative efficiency. Conversely, the FeIII/FEP/CEC maintains controlled FeII regeneration without iron overaccumulation, thereby suppressing radical scavenging pathways. This mechanistic divergence underpins the enhanced degradation performance of FeIII/FEP/CEC over its FeII counterpart. Furthermore, dose-independent kinetic studies further demonstrated non-proportional behavior, where increasing FeCl3 concentrations from 1 mM (kobs = 0.125 min–1) to 2 mM (kobs = 0.146 min–1) resulted in only 16.8% rate enhancement. The sublinear increase implies competitive •OH consumption by surplus FeII at elevated catalyst loads, highlighting the necessity for optimizing FeCl3 dosage to maximize system efficacy. Although the reaction between H2O2 and FeIII could generate •OOH and lead to the formation of 1O2 for pollutants degradation1,45, this sluggish reaction was deemed too slow to be considered the primary reduction pathway (Eq. 16). Besides, the H2O2 decomposition process exhibited direct proportionality to fresh FeII generation rates, as evidenced by the system-dependent hierarchy: FeIII/FEP/CEC displayed maximal H2O2 consumption (the reduction of H2O2 yield between FEP/CEC and FeIII/FEP/CEC, Δ[H2O2] = 0.55 mM) concurrent with peak FeII accumulation (0.14 mM), followed by FeIII/PTFE/CEC (Δ[H2O2] = 0.28 mM; FeII = 0.09 mM) and FeIII/PVDF/CEC (Δ[H2O2] = 0.05 mM; FeII = 0.03 mM). These quantitative correlations confirm the operational SC-Fenton mechanism wherein H2O2 undergoes continuous decomposition through FeII-catalyzed reactions, sustaining redox cycling between FeIII/FeII states. (Supplementary Fig. 9). Consequently, the cycling process between FeIII and FeII was divided into two steps: (i) the FeIII acquired one CE electron and reduced into FeII, and (ii) the FeII promptly activated the generated H2O2 and transformed back into FeIII.

Figure 7 illustrates the FeIII/FEP/CEC mechanism for pollutant degradation through three sections: (i) H2O2 generation via ultrasound-triggered contact-electrification (CE), where electron transfer from H2O to the FEP surface, yielding *OH and electron-rich FEP*. Subsequently, the induced interfacial electric field (IEF) on FEP* promoted the H2O2 generation via lowering the free energy for the *OH recombination into H2O2 via the indirect 2e– process. (ii) FeIII reduction into FeII, where accumulated CE electrons on the FEP* surface reduced FeIII while FEP* returned to its original uncharged state as FEP to initiate a new cycle of H2O2 generation. (iii) Fenton-driven water purification, where the generated H2O2 and FeII initiate the Fenton reaction, producing •OH to degrade pollutants. Concurrently, the FeIII generated from the Fenton reaction went through a new reduction into FeII by CE electrons on FEP* as shown in section ii). This FeIII/FEP/CEC triggered self-cycled Fenton by simultaneous H2O2 production and FeIII reduction into FeII in one system, ultimately achieving efficient water purification.

Discussion

This study presents a novel FeIII/FEP/CEC system that resolves critical limitations in self-cycled Fenton reactions by synergistically integrating H2O2 generation and FeIII reduction within a unified catalytic platform. The FEP/CEC configuration demonstrates particular significance, achieving superior H2O2 accumulation (7.67 mmol·gcat–1·h–1) through an indirect 2e– WOR. This performance enhancement originates from the established IEF, which effectively lowers the free energy for *OH formation and subsequent recombination into H2O2. Simultaneously, the system facilitates the continuous regeneration of FeII through triboelectrically driven FeIII reduction, amplifying •OH yields compared to conventional Fenton systems and thereby elevating overall pollutant degradation efficiency. Our findings validate the technical viability of self-cycled Fenton processes through the strategic coupling of FeIII and FEP/CEC, propelling the engineering of energy-autonomous water purification systems. Beyond immediate applications, this work stimulates synergistic exploitation of FEP/CEC’s dual oxidative-reductive functionalities, as evidenced by its capacity to simultaneously drive H2O2 synthesis (oxidative pathway) and FeIII activation (reductive pathway). Such bifunctional capability not only advances water treatment technologies but also establishes a paradigm for designing multifunctional catalytic systems to address environmental remediation challenges.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

All the chemical reagents were provided in Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Table 1.

Experimental procedures

The performance of H2O2 generation by FCPs/CEC (FCPs: fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP, average 5 μm), polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE,

The catalytic degradation performance of FCPs/CEC SC-Fenton system were investigated with FeCl3 (1.0 mM except as specifically mentioned) as iron precursor added into the ultrasound bath. The 5 mg·L–1 of sulfadiazine (SDZ), carbamazepine (CBZ), phenol (PE), and atrazine (ATR) were selected as target pollutants to test degradation ability without pH adjustment except as mentioned. All the degradation reaction was conducted under ultrasound irradiation (40 kHz, 110 W) at 25 ± 2 °C. At a certain time interval, 1 mL of liquid sample was withdrawn and filtered by 0.22 µm polyethersulfone membranes and quenched by methanol for further analysis of the target pollutants concentration. The FCPs after reactions were separated from liquid by a vacuum filtration system and washed with ethanol, followed by drying 50 °C overnight before reutilization or analysis.

Analytical methods

The concentration of H2O2 was determined by the potassium titanium (IV) oxalate method57. Detailly, the potassium titanium (IV) oxalate solution was prepared via 7.083 g of potassium titanium (IV) oxalate adding into 10 M of H2SO4. Here, 2 mL of filtered sample, 2 mL of potassium titanium (IV) oxalate solution, and 1 mL deionized water were mixed for 5 min, and the absorbance of the mixture was further measured by a spectrophotometer (Thermo, Evolution 220, USA) at 400 nm. The H2O2 concentration was quantitatively calculated by the standard curve (R2 = 0.9998) in Supplementary Fig. 1. The relative quantitative analysis of hydroxyl radical was conducted by a fluorescence method in Supplementary Note 3. The detection of reactive species was utilized by EPR spectroscopy (Supplementary Note 4). The concentrations of pollutants were analyzed using UPLC (Waters, H-CLASS, USA) equipped with PDA detector and C18 column with flowing rate of 0.2 mL·min–1. More parameters of the mobile phase and detection wavelength were provided in Supplementary Table 5. The concentration of Fe species was carried out in accordance with the details in Supplementary Note 1. The density functional theory (DFT) calculation was conducted according to the details in Supplementary Note 5. The transferred electrons of the FCP surface were analyzed by the single electrode triboelectric nanogenerator (SETENG) based on the Supplementary Note 6.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Zhou, P. et al. Fast and long-lasting iron(III) reduction by boron toward green and accelerated Fenton chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 16517–16526 (2020).

Shi, Y. et al. Defect-engineering-mediated long-lived charge-transfer excited-state in Fe–gallate complex improves iron cycle and enables sustainable Fenton-like reaction. Adv. Mater. 36, 2305162 (2024).

Mao, Y. et al. Accelerating FeIII-aqua complex reduction in an efficient solid–liquid-interfacial Fenton reaction over the Mn–CNH co-catalyst at near-neutral pH. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 13326–13334 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Molybdenum sulfide co-catalytic Fenton reaction for rapid and efficient inactivation of Escherichia coli. Water Res. 145, 312–320 (2018).

Wu, Y., Che, H., Liu, B. & Ao, Y. Promising materials for photocatalysis-self-Fenton system: properties, modifications, and applications. Small Struct. 4, 2200371 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. Boosting 2e− oxygen reduction reaction in garland carbon nitride with carbon defects for high-efficient photocatalysis-self-Fenton degradation of 2,4-dichlorophenol. Appl. Catal. B 307, 121185 (2022).

Wang, F. et al. Unprecedentedly efficient mineralization performance of photocatalysis-self-Fenton system towards organic pollutants over oxygen-doped porous g-C3N4 nanosheets. Appl. Catal. B 312, 121438 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Resin-based photo-self-Fenton system with intensive mineralization by the synergistic effect of holes and hydroxyl radicals. Appl. Catal. B 315, 121525 (2022).

Fu, C. et al. Dual-defect enhanced piezocatalytic performance of C3N5 for multifunctional applications. Appl. Catal. B 323, 122196 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. O2-independent H2O2 production via water–polymer contact electrification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 925–934 (2024).

Shi, X. et al. Understanding activity trends in electrochemical water oxidation to form hydrogen peroxide. Nat. Commun. 8, 701 (2017).

Siahrostami, S. et al. A review on challenges and successes in atomic-scale design of catalysts for electrochemical synthesis of hydrogen peroxide. ACS Catal. 10, 7495–7511 (2020).

Nosaka, Y. & Nosaka, A. Y. Generation and detection of reactive oxygen species in photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 117, 11302–11336 (2017).

Perry, S. C. et al. Electrochemical synthesis of hydrogen peroxide from water and oxygen. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 442–458 (2019).

Xu, J. et al. Highly efficient FeIII-initiated self-cycled Fenton system in piezo-catalytic process for organic pollutants degradation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202307018 (2023).

Hu, X. et al. Engineering nonprecious metal oxides electrocatalysts for two-electron water oxidation to H2O2. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2201466 (2022).

Siahrostami, S., Li, G.-L., Viswanathan, V. & Nørskov, J. K. One- or two-electron water oxidation, hydroxyl radical, or H2O2 evolution. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 1157–1160 (2017).

Ma, J. et al. H2O2 photosynthesis from H2O and O2 under weak light by carbon nitrides with the piezoelectric effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 21147–21159 (2024).

Li, S. et al. Contributions of different functional groups to contact electrification of polymers. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001307 (2020).

Wang, Z., Dong, X., Tang, W. & Wang, Z. L. Contact-electro-catalysis (CEC). Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 4349–4373 (2024).

Chen, B. et al. Water–solid contact electrification causes hydrogen peroxide production from hydroxyl radical recombination in sprayed microdroplets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2209056119 (2022).

Zou, H. et al. Quantifying the triboelectric series. Nat. Commun. 10, 1427 (2019).

Berbille, A. et al. Mechanism for generating H2O2 at water-solid interface by contact-electrification. Adv. Mater. 35, 2304387 (2023).

Zhao, J. et al. Contact-electro-catalysis for direct synthesis of H2O2 under ambient conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202300604 (2023).

Su, Y. S. et al. Reduction of precious metal ions in aqueous solutions by contact-electro-catalysis. Nat. Commun. 15, 4196 (2024).

Nie, J. et al. Probing contact-electrification-induced electron and ion transfers at a liquid–solid interface. Adv. Mater. 32, 1905696 (2020).

Yuan, X., Zhang, D., Liang, C. & Zhang, X. Spontaneous reduction of transition metal ions by one electron in water microdroplets and the atmospheric implications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 2800–2805 (2023).

Ma, D. et al. Fluorocarbon polymers mediated contact-electro-catalysis activating peroxymonosulfate for emerging pollutants degradation: the key role of fluorine density in electron transfer. Chem. Eng. J. 497, 154996 (2024).

Wu, Y. et al. Triggering dual two-electron pathway for H2O2 generation by multiple [Bi−O]n interlayers in ultrathin Bi12O17Cl2 towards efficient piezo-self-Fenton catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202316410 (2024).

Wei, Y., Zhang, Y., Geng, W., Su, H. & Long, M. Efficient bifunctional piezocatalysis of Au/BiVO4 for simultaneous removal of 4-chlorophenol and Cr(VI) in water. Appl. Catal. B 259, 118084 (2019).

Feng, J. et al. Significant improvement and mechanism of ultrasonic inactivation to Escherichia coli with piezoelectric effect of hydrothermally synthesized t-BaTiO3. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 6032–6041 (2018).

Shao, D., Zhang, L., Sun, S. & Wang, W. Oxygen reduction reaction for generating H2O2 through a piezo-catalytic process over bismuth oxychloride. ChemSusChem 11, 527–531 (2018).

Wang, K. et al. Ternary BaCaZrTi perovskite oxide piezocatalysts dancing for efficient hydrogen peroxide generation. Nano Energy 98, 107251 (2022).

Zeng, H. et al. Boost piezocatalytic H2O2 production in BiFeO3 by defect engineering enabled dual-channel reaction. Mater. Today Energy 39, 101475 (2024).

Cui, Y. et al. Harvesting vibration energy to produce hydrogen peroxide with Bi3TiNbO9 nanosheets through a water oxidation dominated dual-channel pathway. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 12, 3595–3607 (2024).

Deng, M., Wang, D. & Li, Y. General design concept of high-performance single-atom-site catalysts for H2O2 electrosynthesis. Adv. Mater. 36, 2314340 (2024).

Li, W. et al. Contact-electro-catalysis for direct oxidation of methane under ambient conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202403114 (2024).

Dong, X. et al. Regulating contact-electro-catalysis using polymer/metal janus composite catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c07446 (2024).

Liu, N., Wang, R., Zhao, J., Jiang, J. & Fan, F. R. Piezoelectricity and triboelectricity enhanced catalysis. NRE. https://doi.org/10.26599/NRE.2024.9120137 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. Nonaqueous contact-electro-chemistry via triboelectric charge. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c09318 (2024).

Fan, F. R., Tang, W. & Wang, Z. L. Flexible nanogenerators for energy harvesting and self-powered electronics. Adv. Mater. 28, 4283–4305 (2016).

Wang, Z. L. & Wang, A. C. On the origin of contact-electrification. Mater. Today 30, 34–51 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. Contact-electro-catalysis for the degradation of organic pollutants using pristine dielectric powders. Nat. Commun. 13, 130 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Efficient fluorocarbons capture using radical-containing covalent triazine frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 31213–31220 (2024).

Li, W. et al. Boosting reactive oxygen species generation via contact-electro-catalysis with FeIII-initiated self-cycled Fenton system. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202413246. (2024).

Zuo, S., Wang, Y., Wan, J. & Yi, J. Hydrogen bonding network in the electrical double layer mediates fast proton skipping to get rid of Fenton reaction pH dependence enables highly efficient alkaline water purification. Water Res. 268, 122612 (2025).

Xiao, J., Guo, S., Wang, D. & An, Q. Fenton-like reaction: recent advances and new trends. Chem. Eur. J. 30, e202304337. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.202304337 (2024).

Wang, Z.-K. et al. Lewis acid-facilitated deep eutectic solvent (DES) pretreatment for producing high-purity and antioxidative lignin. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8, 1050–1057 (2020).

Han, X. et al. A new strategy to strongly release sweet-enhancing volatiles from goji pomace using trivalent iron salts. Food Res. Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2023.112659 (2023).

Marcotullio, G., Krisanti, E., Giuntoli, J. & de Jong, W. Selective production of hemicellulose-derived carbohydrates from wheat straw using dilute HCl or FeCl3 solutions under mild conditions. X-ray and thermo-gravimetric analysis of the solid residues. Bioresour 102, 5917–5923 (2011).

Motohashi, N. & Saito, Y. Competitive measurement of rate constants for hydroxyl radical reactions using radiolytic hydroxylation of benzoate. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 41, 1842–1845 (1993).

Ma, D. et al. A green strategy from waste red mud to Fe0-based biochar for sulfadiazine treatment by peroxydisulfate activation. Chem. Eng. J. 446, 136944 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Aqueous iron(IV)-oxo complex: An emerging powerful reactive oxidant formed by iron(II)-based advanced oxidation processes for oxidative water treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 1492–1509 (2022).

Zhou, H. et al. Redox-active polymers as robust electron-shuttle co-catalysts for fast Fe3+/Fe2+ circulation and green Fenton oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 3334–3344 (2023).

Zhang, H., Zhang, D. B. & Zhou, J. Y. Removal of COD from landfill leachate by electro-Fenton method. J. Hazard. Mater. 135, 106–111 (2006).

Sun, Y. & Pignatello, J. J. Photochemical reactions involved in the total mineralization of 2,4-D by iron(3+)/hydrogen peroxide/UV. Environ. Sci. Technol. 27, 304–310 (1993).

Lee, J. K. et al. Spontaneous generation of hydrogen peroxide from aqueous microdroplets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 19294–19298 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [22476021 and 22476020], the National Key Research and Development Program of China [2022YFA0912503], the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong [2025A1515010771], the Key Research Platforms and Projects of Guangdong Universities [2023ZDZX3038], and the Start-up fund for Postdoctoral of Dongguan University of Technology [221110168]. XPS data were obtained using equipment maintained by Dongguan University of Technology Analytical and Testing Center. The authors gratefully acknowledge the intellectual contributions from Prof. YH. Ao of Hohai University for insightful discussions on the mechanism.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M. and J.Z. contributed equally to this work. W.L.: Writing— review & editing, writing—original draft, supervision, funding acquisition, and conceptualization. J.M.: Writing—review & editing and formal analysis. K.H. and K.Y.: Methodology, investigation, and formal analysis. J.C.: Validation and formal analysis. Q.L.: Resources and formal analysis. M.Z. and F.C.: Resources and methodology. D.X.: Writing—review & editing, funding acquisition, and formal analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, D., Zhang, J., Li, W. et al. FeIII-driven self-cycled Fenton via contact-electro-catalysis for water purification. npj Clean Water 8, 42 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00476-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00476-0