Abstract

This study presents the first rigorous, multi-parameter evaluation of near-real-time flow cytometry (FCM) for automated on-site monitoring at a model alpine karst spring used as a drinking water resource. We tested automated FCM for its capacity to indicate microbial cell inputs from the catchment surface (SRI) and to indirectly indicate diffuse faecal contamination (DFC). A nested 10-year study design combined low-frequency monitoring with high-frequency event sampling. The instruments tested in the study performed well under challenging field conditions and reliably quantified microbial cells, as validated against established methods. FCM parameters robustly detected SRI and, indirectly, DFC, in a catchment with diffuse animal faecal contamination sources. The same performance was observed for the online physico-chemical parameters UV254 and turbidity. The combination of these biotic and abiotic indicators outperformed single parameters in early warning analyses, demonstrating their potential for water safety planning by enabling timely and specific responses. The various aspects of the automated on-site monitoring devices used are discussed in detail. While automated FCM already supports the indirect detection of diffuse faecal pollution, further technical advances are necessary to extend its scope toward the specific and sensitive detection of faecal contamination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Karst groundwater is a vital source of drinking water in many regions worldwide, with an estimated 10% of the global population depending on karst aquifers for their supply1. Despite their utility, karst aquifers are characterised by limited physical and chemical filtration capacities compared to porous media aquifers2. This vulnerability is due to their hydrogeology, which includes rapid recharge through dolines, rock fissures (“fractured flow”), or thin soil layers covering carbonate bedrock. Such recharge pathways can result in pronounced fluctuations in water quality, especially during high discharge events3, making these systems particularly susceptible to contamination4,5. Rapid responses to precipitation6 may lead to swift contamination7 when surface-derived materials enter the hydraulically conductive aquifer8. Contaminants may include chemicals such as pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and radionuclides9,10,11, however, the key health concern is often faecal contamination and the associated risk of enteric pathogens12. Faecal inputs may originate from animal droppings or failing sanitation systems and can be accompanied by terrestrial bacteria, soil, vegetation, and organic nutrients that can stimulate heterotrophic growth, potentially compromising the biological stability of drinking water during transport and distribution13.

To address microbiological risks in karst systems in the World Health Organization’s water safety planning (WSP) framework12, a three-tiered strategy has been recommended: resource protection to prevent pollution, selective abstraction, and final treatment and disinfection14. The relative importance of each tier depends on aquifer and catchment characteristics14. Standardised cultivation-based microbiological analyses play a central role at all three levels within this framework13,14. However, such methods are labour-intensive and have long time-to-result15, limiting their capability to capture short-term microbiological dynamics in response to hydrological events6, and therefore their applicability for real-time monitoring or routine operational use.

In contrast, many physico-chemical parameters – such as electrical conductivity, UV absorbance at 254 nm (UV254), pH, and turbidity – can be monitored in near-real-time with reliable on-site sensors16. Until recently, this was not possible for microbiological parameters. However, recent advances have enabled on-site, near-real-time detection of microbiological water quality changes using automated tools (automated on-site monitoring, AOM, 16) such as β-D-glucuronidase activity measurement17,18, intra- and extracellular ATP measurements19, camera-based particle classification for cell counts20, and flow cytometry (FCM21). Among these, FCM provides total (TCC) and intact cell counts (ICC) and has been shown to sensitively track microbial responses to precipitation events at karst springs22. This suggests FCM-based parameters as potential proxies for surface-derived microbial inputs. More recently, multivariate fingerprinting approaches for FCM data – such as Bray–Curtis dissimilarity, Cytometric Histogram Image Comparison (CHIC), and flowEMMi v2 – have demonstrated greater sensitivity than TCC alone in detecting changes in microbial community structure and physiology23,24,25,26,27,28.

To date, near-real-time automated FCM has been deployed at karst springs in two Swiss catchments. In the Jura Mountains, Page et al. (2017) monitored three springs over three months and linked TCC and physico-chemical parameters to rainfall events22. In northeast Switzerland, Besmer et al. (2017) linked TCC and physico-chemical indicators to faecal contamination at two karst springs6. However, no study has comprehensively assessed FCM data against a broad set of surface-derived microbiological parameters. In particular, it remains unclear to what extent FCM parameters can distinguish faecal contamination from other types of microbial fluctuations.

The goal of this study was to rigorously evaluate multivariate, near-real-time flow cytometry as a tool for AOM at an alpine karst spring used for drinking water supply. The study was conducted at a well-characterised limestone spring in the Northern Calcareous Alps with extensive prior research and long-term monitoring records13,29,30. The study design comprised four main components:

-

(i)

Collection of a comprehensive dataset representative of the hydrological and pollution dynamics of the spring using a nested sampling design. This combined a 10-year low-frequency monitoring program with two summer high-frequency campaigns, including microbiological, physico-chemical, and meteorological parameters.

-

(ii)

Method validation of fully automated on-site near-real-time FCM by testing under operational field conditions and comparison with epifluorescence microscopy (EFM) and a second FCM system.

-

(iii)

Evaluation of multiple FCM parameters – TCC, ICC, and fingerprinting – for their capacity to indicate catchment-surface-related microbial cell inputs (SRI) and to indirectly indicate faecal contamination from diffuse pollution sources (diffuse faecal contamination, DFC). FCM cannot specifically identify faecal sources but may indirectly indicate contamination as a proxy. For comparison, real-time UV254 and turbidity were also assessed for their SRI and indirect DFC indication potential against standardised cultivation-based and molecular indicators of terrestrial and diffuse faecal inputs (i.e., ruminant- and soil-associated genetic microbial source tracking markers).

-

(iv)

Early-warning potential of FCM and physico-chemical parameters was assessed using machine learning models to identify optimal parameter combinations for faecal contamination detection. In addition, FCM fingerprinting was applied to assess microbial population shifts as indicators of surface-derived microbial pollution.

Results

Adopting a nested sampling design to identify periods and extent of surface-related contamination events

The studied spring, LKAS8, displayed a highly dynamic hydrological regime, characteristic of alpine limestone karst springs in temperate climate zones. During winter, a persistent snow cover led to relatively constant and low discharge levels, followed by increased discharge during snowmelt. In contrast, during the warmer summer and autumn seasons, discharge patterns became highly variable due to the influence of heavy rainfall events13.

To capture the spring’s dynamic water quality, a nested sampling design covering multiple time scales was applied, as suggested by Farnleitner et al.14,29 (Fig. 1). To track inter-annual differences and seasonal trends in the microbiological water quality of the spring and to evaluate whether variations in cell count parameters correspond to fluctuations in surface-derived and faecal pollution, a long-term, low-frequency monitoring (LTM) program was conducted over a 10-year period (2012–2021). This included: (i) total cell counts (TCC) and other bacterial cell count parameters, measured by EFM and a laboratory benchtop flow cytometer (FCM_a); (ii) standardised, cultivation-based detection of E. coli and total coliforms; and (iii) genetic microbial source tracking markers measured by qPCR. Microbiological monitoring was complemented by meteorological, hydrological, and physico-chemical parameters, aggregated to hourly and daily values (Table 1).

Based on the LTM data with monthly sample collection for microbiological analyses, HFS campaigns were performed in the summers of 2020 and 2021. In comparison to 2020 where cultivation-based indicators and genetic markers were determined twice a week, the sampling frequency was extended to 4 times per day during the identified precipitation events (“Event sampling”).

To test the feasibility of real-time determination of bacterial cell count parameters via FCM during surface-related contamination events, we conducted targeted, high-resolution event monitoring campaigns (high-frequency sampling, HFS) during the summers of 2020 and 2021 (July to September), in parallel with the ongoing LTM program. During these campaigns, automated near-real-time FCM (FCM_b) was implemented directly at the spring outlet, substantially increasing the frequency of microbiological analyses (Fig. 1, Table 1). In 2020, intact cell counts (ICC) were measured automatically every 2 hours from July 20 to September 29 (n = 705). In addition, grab samples were collected twice weekly for analysis of TCC, ICC, E. coli, total coliforms, and genetic markers. Building on the experience from the LTM and 2020 HFS campaigns, the sampling strategy in 2021 was adapted dynamically according to spring conditions following precipitation events. From May 27 to September 23, 2021, grab samples were collected every 6 hours using an auto-sampler in response to heavy rainfall in the catchment, enabling dense, multiparametric characterization of contamination events triggered by precipitation > 40 mm day⁻¹. The interval for automated FCM measurements of TCC and ICC was also set to 6 hours (n = 476). Three distinct precipitation events were identified in the LKAS8 catchment during each of the two summer monitoring periods. This nested sampling strategy enabled the characterization of both seasonal water quality changes and short-term responses to rainfall events, capturing microbial dynamics via automated near-real-time FCM in unprecedented detail and in a resource-efficient manner.

Long-term water quality monitoring revealed highest microbial variability and most sensible use of FCM during summer months

The quantitative hydrological response of the spring was influenced by multiple factors, including local precipitation events, preceding dry periods, and infiltration pathways into the karst system. Consequently, precipitation peaks recorded by a single weather station in the spring catchment often – but not always – resulted in increased discharge at the spring outlet (Fig. 2A). Snow cover was present only during the winter and early spring months (November to May). Figure 2 and Table 1 summarise the hydrological, physico-chemical, and microbiological data collected over the 10-year monitoring period (2012–2021). Spring discharge exhibited pronounced variability, with the most distinct and annually recurring peaks observed in spring (March–May) due to snowmelt (Qmax: 237,545 m3 d-1). Winter discharge was generally low (December–February, Qmin: 10,282 m3 d-1), yielding a discharge coefficient (Qmax/Qmin) of 1/23. While 66% of all peaks exceeding 100,000 m³ d⁻¹ occurred in spring, 25% were recorded between June and September. For example, the discharge peak on 20 September 2017 (154,015 m³ d⁻¹) surpassed that of the spring snowmelt in the same year, underscoring the hydrological relevance of intense summer rainfall events.

Results of the monthly long-term monitoring, showing hydrological and meteorological (A), physico-chemical (B) and microbiological (C–E) parameters between 01/2012 and 12/2021. EFM Epifluorescence Microscopy, FCM_a:Laboratory Flow Cytometer, HNA High Nucleic Acid-Containing Cells, TCC Total Cell Counts, E. coli Escherichia coli, 16S 16S rRNA gene, AllBac soil- and faeces-associated general Bacteroidetes marker, BacR faeces-associated, ruminant-specific Bacteroidetes marker, ME marker equivalents, MPN most probable number.

UV254 and turbidity exhibited high temporal variability. The most pronounced UV254-peaks over the decade were recorded in April and September, while turbidity peaked in June during extreme precipitation events. Water temperature at LKAS8 remained relatively stable (mean: 6.2 °C) and fluctuated by only ~1 °C (Fig. S1). Electrical conductivity reached its lowest values in May and June (226 µS cm⁻¹) after snowmelt and increased towards winter, peaking in February (mean max: 258 µS cm⁻¹, Fig. S1).

All biotic parameters showed distinct seasonal patterns, with higher values in summer. For many parameters, seasonal differences were statistically significant compared to at least one other season, typically winter (Fig. S3, Table S1). TCC, as measured by EFM, ranged from 0.8 × 10⁴ to 31.8 × 10⁴ cells mL⁻¹, with a summer median being 2.1 times higher than the winter median (Fig. 2C, Table 1, Fig. S3). High nucleic acid (HNA) cells, especially in combination with TCC, often provide typical information on the characteristics of the natural bacterial community by sensitively detecting small changes within it31,32. HNA cells accounted for 15% to 87% of total cells, with a median of 35%. Seasonal variation in HNA cells closely followed that of TCC (Fig. S3). The concentration of 16S rDNA marker equivalents (ME) ranged from 0.001 × 10⁶ to 153.0 × 10⁶ ME 100 mL⁻¹ and mirrored the seasonal trends observed in TCC (Fig. 2E). Particularly strong seasonal trends were observed for cultivation-based indicators: total coliforms (soil- and faeces-associated) and E. coli (faecal indicator, Fig. 2D). Total coliforms were detected mostly, while E. coli occurred almost exclusively between May and September. The overall detection rates were 47.5% for total coliforms and 32.2% for E. coli (n = 1,051; Table 1, Fig. S3), with concentrations ranging from below detection to >700 CFU 100 mL⁻¹. The ruminant-associated genetic faecal marker BacR was also detected only in summer and autumn (overall occurrence: 38%) and ranged from below detection to 9.6 × 10³ ME 100 mL⁻¹ (Fig. 2E, Table 1). The soil- and faeces-associated genetic marker AllBac was detected in all samples, with concentrations ranging from 0.02 × 10³ to 178 × 10³ ME 100 mL⁻¹, and showed clear seasonal peaks during spring and summer (Fig. 2E, Table 1). The co-occurrence of high variability in all cell count parameters with that of soil- and faecal-associated markers suggests that FCM-based parameters may serve as useful proxies for identifying contamination events at the karst spring

Application of on-site near-real-time FCM to follow microbial dynamics during summer precipitation events

Two HFS campaigns (07/2020 – 09/2020 and 05/2021 – 09/2021) were conducted. In both HFS periods three precipitation events per summer with lengths of 14 to 36 days were recorded (Fig. 3, Table 1) without any gap between the events. The onset was defined as soon as 40 mm of daily rainfall was exceeded, leading to a subsequent increase in the measured parameters, the end was defined when all parameters reached baseline levels (which did never occur during the two summers) or when the next event started. Daily initial precipitation sums of 49.0 mm (Event 1 – E1), 44.9 mm (E2), 45.2 mm (E3), 74.6 mm (E4), 50.6 mm (E5) indicated the start of each event. E6 did not meet the initial precipitation quantity criterion (36.7 mm), hence no additional samples for cultivation-based indicators and genetic markers were taken. However, a late and minor increase of turbidity and a slow onset of UV254, as well as pronounced peaks in cell counts and E. coli led to the decision to retrospectively identify this event as such. During E3, E5 and E6, further rainfall events that never exceeded 35 mm d-1 led to double peaks in UV254, E. coli, TCC and ICC. All investigated physico-chemical and biological parameters showed a rapid increase at the start of the event. Peak concentrations of cell count parameters were 50 to 100-fold higher than before the event, while the 16S marker increased up to 800-fold. As for the faecal indicators, E. coli increased from non-detect to > 500 MPN 100 mL-1 and BacR increased from non-detect to > 38,000 ME 100 mL-1. The AllBac marker increased up from 200 to 4.7×106 ME 100 mL-1. Fig. S2 provides a closer look into the initial increase phases of the six events. No systematic parameter sequence is apparent: All events were different from each other regarding the sequence and shape of the different parameters curves.

Results of the two high frequency sampling campaigns conducted during the summers 2020 and 2021: hydrological and meteorological (A), physico-chemical (B) and microbiological (C–F) parameters between 07-09/2020 and 05-09/2021. As opposed to the reference period, or “baseflow” conditions, precipitation event conditions were defined as exceeding > 40 mm day⁻¹. Cumulative precipitations per event were as follows: 154.2 mm (E1, 2020/08/04 – 08/18), 119.6 mm (E2, 2020/08/18 – 09/01), 131.4 mm (E3, 2020/09/01 – 09/27), 137.9 mm (E4, 2021/07/17 – 08/01), 123.0 mm (E5, 2021/08/01 – 08/19), and 132.5 mm (E6, 2021/08/19 – 09/24). 3 C: TCC data is almost invisible due to overlaps with ICC-data on the log-scale. No cell count data are available from 08-15/08/2020 (grey shaded areas, 92 missing values due to power cut). FCM_b Automated Near-Real-Time Flow Cytometer, HNA High Nucleic Acid-Containing Cells, ICC Intact Cell Count, TCC Total Cell Counts, E. coli Escherichia coli, 16S 16S rRNA gene, AllBac soil- and faeces-associated general Bacteroidetes marker, BacR faeces-associated, ruminant-specific Bacteroidetes marker, ME marker equivalents, MPN most probable number.

Comparing the capacity of FCM and physico-chemical on-line parameters to indicate surface-related inputs, including faecal pollution

Variations in automatically measurable parameters in the spring water may reflect, besides aquifer re-mobilisation processes, catchment surface related inputs of terrestrial origin, including potential faecal contamination events. Thus, we investigated the SRI (surface-related cell input) and indirect DFC (diffuse faecal contamination) indication capacity of the near-real-time cell count parameters (TCC, ICC, HNAP, dissimilarity score) by using comparative analysis with total coliforms, AllBac (i.e. microbiological parameters associated with cell input from catchment surface) as well as E. coli, BacR (i.e. microbiological parameters originating from general and ruminant-associated faecal pollution). As a comparison, the established on-site real-time physico-chemical parameters UV254 and turbidity were also assessed as real-time proxies for SRI and DFC (Fig. 4). The analysis is based on the LTM- (ncell counts = 111, ncultiv.-based indicators = 79, ngenetic markers = 107) and the 2021 HFS datasets (ncell counts = 265, ncultiv.-based indicators = 103, ngenetic markers = 72). Generally, higher correlations between the investigated parameters were found in the HFS set (Fig. 4, all highly significant) than in the LTM-set. Therefore, only these are described in detail below.

Near-real-time FCM-based and real-time physico-chemical parameters indicating surface related inputs and additional diffuse faecal contamination on-site: Scatter plots and Spearman rank correlation coefficients (r = rho) of microbiological (TCC, HNAP and Dissimilarity score) and physico-chemical parameters (UV254, turbidity) against indicators for surface-related contamination (general: total coliforms and Allbac; faecal: E. coli and BacR) obtained during LTM and HFS 2021. HFS = grey dots, event 4 = light red dots, event 5 = middle red dots; event 6 = dark red dots. Grey correlation coefficients correspond to LTM data, red correlation coefficients correspond to events from HFS 2021. The stars after the value of rho corresponds to the probability of the correlation to be zero. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001. EFM Epifluorescence Microscope, FCM_b Automated Near-Real-Time Flow Cytometer, HNA High Nucleic Acid-Containing Cells, ICC Intact Cell Count, E. coli Escherichia coli, AllBac soil- and faeces-associated general Bacteroidetes marker, BacR faeces-associated, ruminant-specific Bacteroidetes marker, ME marker equivalents, MPN most probable number.

As a measure of their indication capacity for microbial cell inputs from the surface (SRI), FCM-derived parameters showed Spearman rank correlation coefficients between 0.59 and 0.76 with total coliforms and between 0.59-0.67 with AllBac, the dissimilarity score had the highest correlation in both cases. The physico-chemical parameters showed correlations with similar ranges but somewhat less variability (0.75-0.76 with total coliforms and 0.66-0.72 with AllBac). As a measure of their diffuse faecal indication capacity (DFC), FCM-based parameters had correlation coefficients between 0.61 and 0.82 with E. coli and 0.74-0.88 with the ruminant-associated marker BacR, the dissimilarity score had the highest correlation with E. coli and TCC with BacR. Again, the physico-chemical parameters showed correlations in similar ranges as the FCM-based parameters (0.81 with E. coli and 0.83-0.90 for BacR). Both novel near-real-time (FCM) and established real-time (physico-chemical) on-site parameters showed higher correlations with faecal than with selected soil markers. The precipitation events of 2021, shown as dots in shades of red in Fig. 4, mostly clustered in the same regions in the scatterplots, while the grey dots of the LTM were more scattered. The high correlations in the HTS dataset provide evidence how tightly interconnected all investigated parameters are in the summer season. This points at coupled contamination processes between SRI and DFC in this system. In contrast, the LTM dataset covers the whole year, including the autumn, winter snow cover and spring snowmelt periods. The low correlations observed point at differing system dynamics in these seasons, also clearly visible from the strong seasonality of microbiological parameters.

Early warning of catchment-surface-related contamination events

Early warning, in terms of the detection of a contamination event, relies on a parameter that reacts quickly to a change in the system, earlier than other parameters might react. This early change may be due to the parameter actually changing earlier in time, or due to a higher sensitivity and/or quicker time-to-result of the measurement method. While no clear pattern was apparent in the sequence of parameters in their reaction of a contamination event (Fig. S2), FCM and the physicochemical parameters have the distinct advantage over the other, microbiological parameters of providing results real-time or near-real-time.

Qualitative changes in bacterial populations using FCM fingerprinting

Besides the large quantitative variations in microbial cell counts described in Results chapter “Application of on-site near-real-time FCM to follow microbial dynamics during summer precipitation events”, qualitative changes in the microbial community were also apparent in the FCM plots. The three-dimensional FCM-ICC data (FL1, FL2, SSC) was then used to derive the cosine dissimilarity score (DS) and to compute the two-dimensional independent component analysis (ICA, 30)32, see Methods chapter “Statistics and data analysis”. Using a threshold derived from a manually set reference period, the DS was categorised into ‘baseflow’ (i.e., similar to the reference period, piggy pink on Fig. 3D), and ‘event’ (i.e., dissimilar to the reference period, red on Fig. 3D). Thus, the DS identified E2, E3, E4, E5 and E6 as events, but not E1. One single value not related to any pollution event detected by the other parameters on July 10 2021 was classified as outlier. Baseflow populations clustered together also in the ICA analysis (Fig. 5) providing another layer of evidence that 2020 and 2021 baseflow bacterial populations were qualitatively similar between the two years. The biggest distance from the baseflow bacterial populations was observed for E4 and E5 of 2021, followed by E2 and E3 of 2020, while E1 of 2020 and E6 of 2021 could not be distinguished clearly.

Flow cytometric dissimilarity score from the summers 2020 and 2021: Independent Component Analysis (ICA) of FCM_b_ICC fingerprint embeddings, where each point represents a measurement. The points are arranged based on the distance between weights on independent components, with closer points indicating higher similarity. Data is shown for high-frequency sampling years 2020 and 2021. Points are color-coded to represent different events: Blues: 2020 data. Lighter shades correspond to specific event periods, while dark blue represents the baseflow. Reds: 2021 data. Darker shades correspond to specific event periods, while dark red represents the baseflow. X signify data points that were classified as dissimilar, while circles were similar to the reference period by the DS analyses. The base flow corresponds to the reference periods of the DS for each year, respectively.

Selection of parameter combinations using machine learning

Results of the HFS showed that parameters measurable in an automated, on-site, and near-real-time manner (UV254, turbidity, flow cytometry-derived cell count parameters) correlated strongly during summer with both SRI-indicators (total coliforms, AllBac) and DFC-indicators (E. coli, BacR; Fig. 4; Results chapter “Comparing the capacity of FCM and physico-chemical on-line parameters to indicate surface-related inputs, including faecal pollution”). Based on these findings, we applied machine learning (Random Forest Classifier, Linear Discriminant Analysis) to online data from 2021 as an early-warning tool to predict both SRI and DFC events. As the Random Forest Classifier consistently outperformed the Linear Discriminant Analysis, only results of the former are shown.

In terms of DFC detection, for the probability of ≥ 5 E. coli [MPN 100 mL⁻¹] the best single-parameter predictors were FCM_b_TCC, FCM_b_HNAICC, and turbidity, all having an accuracy of 0.94. Accuracy increased to 0.98 when using parameter pairs such as FCM_b_HNAICC + DSICC or turbidity + DSICC; adding other parameters did not improve performance. For ≥ 100 BacR [ME 100 mL⁻¹], the best single predictor was turbidity (0.90), closely followed by FCM_b_HNATCC (0.89). Combining UV254 with either FCM_b_HNAPTCC or FCM_b_ICC yielded the best two-parameter accuracy (0.93), with no gain from additional inputs.

In terms of SRI detection, the probability of ≥ 5 total coliforms [MPN 100 mL⁻¹] was predicted most accurately by FCM_b_TCC (0.90), followed by UV254 (0.84). Combining UV254 + FCM_b_TCC + DSICC + DSTCC did not improve accuracy beyond 0.90. For ≥ 10,000 AllBac [ME 100 mL⁻¹], the top single predictor was FCM_b_HNATCC (0.90), with the best two-parameter combinations being FCM_b_HNAPTCC + FCM_b_TCC (0.95) or FCM_b_HNAPTCC + turbidity (0.93); again, additional parameters did not improve results.

Comparing automated FCM to lab-based cell count methods in terms of precision and agreement

In order to validate the performance of the automated flow cytometers (FCM_b), measurement precision of the methods used, as well as reliability in comparison to, and agreement with other methods are described in this chapter. Pearson’s pairwise correlations were calculated between FCM_b and comparative cell counts obtained with FCM_a (laboratory FCM) and EFM (as established method for bacterial cell quantification in water samples), as well as to 16S rRNA gene marker equivalents (as an approximation of bacterial genome copies) of the respective samples. Bland Altman plots allowed a concise visualisation of the agreement between two methods.

Measurement precision of the methods used

Previous publications described a typical coefficient of variation (CV) of FCM in general to be in the range of 3 - 7%33 and of FCM_b_TCC specifically to be < ± 5%34 when performing multiple comparative measurements with the same sample by the same user (repeatability). In own laboratory experiments (n = 240), different concentrations and sources of contaminant material were used to challenge the FCMs. We can report a CV of 6.71% (FCM_b_TCC) and 7.19% (FCM_b_ICC) for the devices used in this study. Due to the internal standardised and automated protocol of FCM_b, also reproducibility (using another instrument handled by another operator) was in the range of 5%. Thus, we can assume that variations in cell numbers > 7% indeed did originate from dynamics in the sampled water. EFM has a similar repeatability but a much poorer reproducibility with a CV of more than 30% owing to considerable user bias35.

Comparability and agreement between the methods used

During LTM from 2012-2021, FCM_b_TCC correlated significantly with EFM_TCC (n = 14, r = 0.79, p ≤ 0.001), FCM_a_TCC (n = 15, r = 0.98, p < 0.001) and 16S rRNA ME (n = 15, r = 0.80, p = 0.003). Also during the high frequency summer sampling, automated FCM_b_TCC measurements correlated significantly with EFM_TCC (n = 55, r = 0.81, p < 0.001) and 16S rRNA ME (n = 93, r = 0.78, p < 0.001). Given the key role of EFM as cell counting method, we took a closer look at the agreement between FCM_b_TCC and EFM_TCC. The dataset comprised 14 samples from the LTM and 55 samples from HFS (total n = 69). A paired samples t-test revealed a significant difference between the means of the two methods (t = -3.8, df=68, p < 0.001). The agreement between the results obtained by the two methods was visualised using a Bland-Altman-plot36. Figure 6 shows the difference between the two measurements expressed as a percentage of their mean in function of the mean. On average, FCM_b_TCC values are 107,000 cells mL-1 lower than EFM_TCC values, with a limit of agreement (the mean difference ± 1.96 × standard deviation) between -563,000 and 349,000 cells mL-1 (-9.2% [-128%, 109%]). The slight tendency towards overall lower values obtained with FCM_b_TCC compared to EFM_TCC becomes more pronounced with higher measured values. Interestingly, event measurements clustered, while LTM measurements were evenly distributed throughout the graph. ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey HSD testing revealed significant differences (p ≤ 0.018) between E6 compared to all other events, 2020 baseflow and LTM. Also, each event of 2020 (E1-E3) differed significantly (p ≤ 0.049) from each event of 2021 (E4-E6).

Modified Bland-Altman plot to depict the agreement of the FCM_b and EFM measurements. Mean differences [%] of FCM_b_TCC to EFM_TCC (n = 69) were plotted against the means of the respective method. The colours code for the sample origin (events 1-6; LTM: monthly samples from long term monitoring; Baseflow 2020). The central horizontal green line represents the mean difference between the two methods, the other two horizontal dotted lines represent the limit of agreement (mean percentage differences ± 1.96 standard deviation).

Discussion

The ongoing digitalisation of the water sector is reshaping how resources are monitored and managed37,38. Within this context, the recent rise of automated AOM of microbiological parameters represents a major advancement, offering, for the first time, near-real-time, online microbiological data16. Despite this progress, systematic and foresighted evaluations of AOM technologies16,39 and FCM, in particular6,8,22, remain scarce, even though they are essential for progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals40. This study presents the first comprehensive evaluation of a near-real-time FCM system for AOM of alpine karst water resources. It assesses both instrument and parameter performance for microbiological system assessment and operational monitoring, under water safety planning12. FCM-derived parameters were evaluated for their direct cell input from the catchment surface (SRI) and indirect diffuse faecal contamination (DFC) indication capacity and as early warning parameters. In parallel, the established real-time physico-chemical parameters UV254 and turbidity were assessed to support an integrated framework16. The investigation was conducted at a karst spring in the Northern Calcareous Alps, where an integrated monitoring system has been operating for almost twenty years29,41. A nested sampling design was applied41,42, including a 10-year low frequency (LTM, n = 60–111) dataset, capturing seasonal variations, and two high frequency sampling campaigns (HFS, n = 63–193) characterising six contamination events altogether.

Automated FCM delivers instrument performance at all levels while maintaining strong agreement with existing methods: FCM_b showed high correlations and synonymous temporal trends with cell count parameters from EFM and FCM_a and also with the general bacterial 16S rRNA marker. Method agreement between the new FCM_b_TCC and EFM_TCC proved to be high with a slight tendency towards overall lower values obtained with FCM_b_TCC.

On-site FCM provides precise and coherent performance: All automated FCM_b_TCC and FCM_b_ICC samples were measured undiluted and methodically the same. With a quantification range between 100 and 2×106 cells mL-1, the lower quantification limit was never approached during the sampling period. Although the upper quantification limit was never exceeded numerically, dual-parameter FL1/FL2 dot plots of FCM_b show signals appearing outside the universal cell gate during extreme precipitation events (8% of the FCM data). Gating strategy affects cell numbers, however, separating signal from noise (e.g. electronic noise from device, but also from measuring inorganic particles) during heavy rainfall was impossible. Hence, the risk of underestimating these 8% of the data was accepted by placing the gate in an optimal position for 92% of the data43. Under demanding operating conditions, automated FCM was successfully deployed in challenging, remote spring conditions, requiring careful setup for humidity control, sediment removal, and stable flow. Despite power and connectivity limitations, data collection proved effective. An alternative to the fully automated and user-friendly BactoSense is the more flexible OC-300 Duo automation module (OnCyt Microbiology AG, Switzerland) combined with a laboratory FCM (Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences, Austria) or CytoFlex S (Beckman Coulter, Inc.)), although expertise and maintenance are then required for two devices.

Indicating and differentiating contamination events at karst springs is challenging. Microorganisms inhabit all ecological niches of karst groundwater, including planktonic phase and biofilms on rock surfaces and sediments, as well as catchment surface habitats such as soil, rhizosphere, and faecal deposits. All these microorganisms may be mobilised and transported to the spring water abstraction site during precipitation events. From a drinking water safety perspective, the challenge is to distinguish microbial cells from the catchment, including faecal ones, from the intrinsic spring water microbial community of the karst system13,44.

Through the detection of nucleic acids, FCM directly quantifies microbial cells. We investigated whether it can also indicate surface-derived cell influx based on changes in cell counts and cell morphological properties, deducted from fluorescence and scatter properties. To our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate the capacity of FCM parameters to indicate surface-related microbial cell inputs (SRI) in karst water resources.

The cell count parameters TCC and ICC-based dissimilarity score, but not HNAP, correlated highly with both SRI indicators (AllBac and total coliforms) during summer rainfall events. Both indicators responded dynamically to events, showing increases of approximately 1,000-fold (coliforms) and 10,000-fold (AllBac), while TCC increased by about 100-fold. HNAP, which previously proved informative in distribution networks45, did not perform well in this context.

Independent component analysis of FCM fingerprints revealed that event populations morphologically clearly differ from baseflow populations. Previous work at a nearby spring has demonstrated a stable core community under baseflow conditions46. During precipitation events, relative abundances among core taxa shifted, and species richness increased; however, 16S rRNA gene data provided no direct evidence of surface-derived cells entering the system46. Earlier studies suggest that most microbial activity occurs in aquifer rock- or sediment-associated biofilms, with planktonic cells originating through detachment47. Nonetheless, event-based increases in qPCR-based genetic markers and cultivation-based faecal indicators in both this and earlier studies42 confirm that catchment-surface-derived microbial inputs do occur – albeit below the detection limit of the applied sequencing strategies. Further research should clarify the relative contributions of the catchment surface (e.g. soil) versus detachment or re-suspension from aquifer biofilms to event-related shifts in microbial signatures13.

The physico-chemical parameters turbidity and UV254, detecting particles and dissolved organic matter, respectively, also correlated strongly with SRI indicators during events, albeit with lower dynamic ranges (approx. 10-fold increases), indicating lower sensitivity compared to the microbiological SRI indicators. However, the sensitivity to detect SRI depends not only on the dynamic range but many other analytical performance characteristics (e.g. precision, detection limit). In conclusion, the performed investigation clearly indicates the robust ability to directly detect SRI by near-real-time FCM and to indirectly detect SRI by real-time physico-chemical on-site sensors.

The LKAS8 spring drains a protected, largely uninhabited alpine catchment. Faecal inputs are diffuse and originate primarily from ruminants (livestock and wildlife), while human contributions are negligible30. During snow-free seasons, faecal deposits (e.g., cowpats, droppings) with other catchment-surface-related particles and dissolved substances from soil and plants may be simultaneously washed into the aquifer by rainfall. We have evaluated the indirect indication capacity of FCM-derived data for diffuse faecal contamination.

Given the dilution processes in the karst aquifer and the low number of faecal-borne cells in relation to non-faecal borne cells (i.e. environmentally occurring microbiota) in the catchments, distinguishing faecal-borne inputs from general variability in TCC is unrealistic. In fact, spiking measurements with sewage or faecal slurries demonstrated that intestinal cell input was difficult to discern from the intrinsic microbial water community by TCC if the intestinal cell input falls below approx. 10% of total cells (Campostrini, unpubl.). This implies for our system that it is not possible to detect faecal pollution from point-sources (e.g. human contamination from alpine cottages) by TCC variability for realistic, low-level faecal pollution scenarios. However, faecal-borne cells and catchment-surface-associated cells, -particles and -molecules can share common origins, have spatial linkage (i.e. faecal droppings exist where soil and thus vegetation (i.e. food) for animal grazers is available) and share hydrological transport routes. We hence evaluated whether FCM- and physico-chemical parameters (UV254, particles) could serve as indirect faecal proxies.

Both faecal indicators, E. coli (for general faecal pollution) and BacR (for ruminant-associated faecal pollution), correlated strongly with TCC and dissimilarity score, but not with HNAP. While TCC followed the fluctuations of both faecal indicators, its dynamics was lower (approx. 100-fold increase by TCC, but 500-fold by E. coli and 10,000-fold by BacR). Nonetheless, these results suggest that both TCC and the dissimilarity score are useful proxies for the diffuse faecal contamination situation in the investigated karst systems.

Physico-chemical parameters also correlated remarkably strongly with the general and the ruminant-associated faecal indicators (r = 0.81-0.90) confirming earlier research that established UV254 as a proxy for diffuse faecal pollution and E. coli at the investigated spring29, though with lower dynamic ranges (10-fold increase) than the faecal indicators.

Building on existing, often abiotic measurement systems, AOM and specifically automated FCM can, when applied in a resource-specific manner, allow for a better understanding of the system. The automated systems compared in this study (Table 2) are complementary in nature, regardless of the type of comparison (e.g., primary indication capacity, time to result, cost, maintenance). Integrated molecule-, particle-, and cell-based detection strategies advance the transition towards a comprehensive and predictive, rather than reactive, water quality management approach that encompasses the physico-chemical, chemical, and microbiological properties of water.

Implementing automated FCM into an existing toolbox must balance to maximise cost efficiency and sustainability and minimise maintenance effort. Our results from the LKAS8 convincingly demonstrate that on-site FCM and physico-chemical sensors can show high agreement in detecting catchment-related microbial contamination (demonstrated for SRI and DFC) in spring water. However, such agreement between molecular and cell-based indicators is likely to occur only when cell transport in the aquifer is mainly driven by fast flow in the conduits, resulting in the same transport behaviour for microbes and molecules. In karst systems with different hydrogeological characteristics, such as a combination of fast and slower diffuse transport, the agreement between the methods is expected to diverge48. Indeed, the sixth event of 2021 hints towards differential transport dynamics49, where E. coli presence was correctly inferred by FCM, but not by SAC, underlining the value of using complementary parameters in spatially and temporally heterogeneous systems. This concept was also confirmed by the applied machine learning model, where E. coli presence was predicted most accurately when traditional physico-chemical parameters were combined with novel near-real-time microbiological parameters from FCM.

In the broader context of water safety planning, automated FCM can offer complementary value across multiple stages. During system assessment, FCM enables high-resolution analysis of microbial community dynamics, which enhances understanding of natural variability and provides source-specific microbial baselines, critical for identifying inherent vulnerabilities. In system monitoring, at critical control points where readily available information is essential, FCM can deliver microbiological data within 20 minutes, enabling event-triggered automated sampling and early warning in a multi-parametric framework alongside physico-chemical and other AOM parameters. Similarly, automated FCM can support spring water abstraction management. Moreover, within distribution networks, FCM can address key microbiological concerns such as biological instability due to internal microbial regrowth, linking internal and external microbiological quality changes within a unified detection framework.

All insights and conclusions presented in this study are based on the LKAS8 alpine limestone karst spring characterised by high hydrological dynamics. While our findings are likely applicable to similar karst and fractured groundwater systems, broader generalisations require validation across additional sites. This includes the evaluation of other AOM techniques, such as microbial enzyme activity assays and fluorescence spectroscopy16. The choice of physico-chemical sensors and AOM methods should be tailored to the specific hydrogeological and water quality characteristics of each water source, forming a customised toolbox.

Future development of automated FCM systems should prioritise the specific detection of prokaryotic faecal pollution and explore approaches for viral target identification. Targeting specific intestinal microbial genera e.g. by labelling functional components on the bacterial cell wall50 could be realised using methods such as flowFISH51 or immunomagnetic separation52 following a filtration and enrichment step. These advances will thus enable specific and sensitive detection of faecal contamination. While automated FCM already supports the indirect detection of diffuse animal-derived faecal pollution, continued progress along these lines will extend the scope of the method, as well as AOM, from general microbial monitoring to pathogen-relevant applications, greatly enhancing its value in water safety management.

Methods

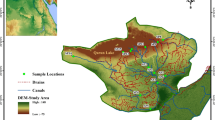

Site description

LKAS8 is a limestone karst spring in the Northern Calcareous Alps. The spring catchment has a size of 11 km2 and expands from an average elevation of 1,341 m to the spring outlet at 522 m above sea level29. LKAS8 has a mean water residence time of 1.2 years30, a highly dynamic hydrological regime with a mean daily discharge of 50,000 m3 day -1, and a Qmax/Qmin discharge ratio of 23. There are no permanent settlements in the area and the vegetation cover is composed of forests and summer pastures in the higher regions30. It was estimated that 99.8% of the faecal indicator E. coli load in the spring originates from ruminant faecal sources, roughly half of which is contributed by livestock and half by wildlife30. Despite the presence of mountain huts and restaurants, human sources of pollution are of minor importance because of efficient wastewater management53. Following selective water abstraction using turbidity and UV254 as decision parameters, the raw spring water flows by means of gravity to a central large storage facility, where it is disinfected before being distributed as drinking water.

Development of a nested sampling strategy

In order to capture the seasonal dynamics in the water quality profile of the spring LKAS8 and to identify the periods of the highest vulnerability of the spring to external pollution, we conducted a long-term monitoring (LTM) of key microbial water quality parameters over 10 years (Jan 2012-Dec 2021, Fig. 1). On a monthly basis, manual grab samples were taken and screened for total bacterial cell counts (TCC) by EFM and FCM_a as well as for genetic markers for various bacterial groups, including Microbial Source Tracking markers, by qPCR. The standard faecal indicator bacterium E. coli and the soil- and faeces associated group total coliforms were determined twice a week. Furthermore, the water supplier provided long-term operational monitoring data (2012-2021) consisting of meteorological, hydrological and physico-chemical logger data measured every 10 minutes, as well as daily discharge sums. Based on these LTM results, a nested strategy for microbiological near-real-time sampling was developed. The onset of an event was defined as soon as 40 mm of daily rainfall was exceeded (criterion 1), leading to a subsequent increase in the measured parameters (criterion 2), the end was defined when all parameters reached baseline levels (which did never occur during the two summers) or when the next event started (based on criterion 1). Sampling was carried out 4 times a day until the values started to decrease again (maximum: 10 d).

Sampling

Manual grab sampling

Spring water samples were collected in clean, autoclaved 2-L glass- and 3.8-L Nalgene- sampling bottles, stored in dark cooling boxes at ambient spring water temperatures for transportation and processed within 3 h after collection.

Automated and event sampling

In summer 2020 and 2021, spring water was continuously pumped via a stainless steel tubing over 8 m vertically upwards into a stainless steel hydrocyclone for near-real-time FCM analysis and automated sampling (Fig. S4). In the hydrocyclone, solids were separated from the bulk water to avoid instrument harm. From there the water was distributed to the flow cytometers, an autosampler with active compressor cooling (MAXX TP5 C Aktiv Vakuum, MAXX Mess- und Probenahmetechnik GmbH, Germany) and a stainless steel tap for manual sampling. In 2020, FCM_b_ICC was programmed to take automated samples every 2 h (2020/07/20 – 2020/09/29) and in 2021, FCM_b_ICC and FCM_b_TCC sampled in 6 h-intervals (2021/05/27 – 2021/09/23). Exceeding of the event criteria during this period triggered additional event sampling in 6 h-intervals using the auto-sampler. Samples were collected in sterile HPDE 1-L bottles, kept at 4-8°C and were processed within 24 h in a field lab in close vicinity to the spring outlet. Before starting the sampling campaign, the autosampler was thoroughly cleaned with hypochlorite and ethanol and rinsed with spring water. At the end of each sampling cycle (after all 24 1-L bottles have been filled), all bottles were removed from the autosampler and manually cleaned using 0.6% NaClO. Bottles were rinsed and brushed once with NaClO and subsequently rinsed 3 times with fresh spring water before being dried upside down. Preliminary tests were conducted in the lab and on site before the start of the sampling campaign to exclude potential adverse influences of bottle material and cleaning protocol on the microbiological and molecular analyses during storage and sampling. No significant influence was observed.

Microbiological parameters

Epifluorescence microscopy for total bacterial cell counts

Total bacterial cell counts (EFM_TCC) were determined by epifluorescence microscopy after filtering 10 mL paraformaldehyde-fixed (final concentration 0.8%; overnight reaction time at 5°C ± 3°C) water sample through 0.2 µm pore-size glass fiber filters (Anodisc 25, Whatman, Germany) and staining the bacteria with SYBR® Gold (Invitrogen) at room temperature for 13 min in the dark. At least 200 cells were counted manually in 20 representative fields of view with an Nikon Eclipse 80i epifluorescence microscope (Optoteam, Austria) according to previously established protocols35. Depending on fluorescence intensity, shape and size, bright, large (rod-shaped and coccoid cells > 1 µm) and small coccoid cells ( < 1 µm) were distinguished. The total bacterial cell count was calculated as the sum of large and small cells.

Laboratory flow cytometry for total bacterial cell counts

A bench-top Attune® NxT acoustic focusing flow cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany) was used as laboratory flow cytometer between 2016 and 2020, herein referred to as “FCM_a”, equipped with a blue laser (488 nm, 50 mW), FSC, SSC (480/10) and fluorescence detectors. The instrument was serviced regularly, decontaminated with sodium hypochlorite (final concentration 0.5%) after every sampling batch and Attune™ Performance Tracking Beads were used daily to ensure the instrument’s accuracy and sensitivity. PMT voltage settings and BL-1 and intrinsic scatter-thresholds were optimised to reliably differentiate background from the bacterial populations of interest. After staining a 1 mL sample with SYBR® Green I (Invitrogen, acc. to manufacturer's instructions) the stained sample was incubated at 37°C for 13 min in the dark54,55,56 and measured with a flow rate of 100 µL min-1. According to the Swiss TCC standard procedure54, bacterial cells were identified based on their green fluorescence collected in the BL1 channel (530/30), and far red fluorescence in the BL3 channel (695/40). Cells with high green fluorescence (cells with high nucleic acid content - HNA) clustered in separate sub-populations than cells with low nucleic acid content (LNA) and were distinguished by secondary gating in BL1 vs. BL3 dotplots55,56. All data were processed with the Attune® NxT software (v2.4) provided by the manufacturer and FlowJo™ v10.7.1 Software (BD Life Sciences) and primary electronic gating was used to separate positive signals from noise57.

Automated near-real-time flow cytometry for total bacterial cell counts

TCC and ICC were determined using two fully automated BactoSense® flow cytometers (bNovate Technologies, Switzerland), herein referred to as “FCM_b”. The BactoSense is equipped with a 488-nm solid-state laser, a side-scatter detector (SSC: 488/10) and two fluorescence detectors (FL1: 535/43, FL2: 715 LP). Before analysis, 135 µL sample was automatically mixed with 15 µL 10x SYBR Green I only (TCC) or with a 10x staining solution consisting of SYBR Green I and Propidium Iodide (ICC). During each measurement, 90 µL of the stained sample was incubated for 10 min at 37°C. One universal pimary gate (fixed graphical boundary) for all density plots per dataset was constructed post-measurement to remove as much background and include as many bacterial signals as possible, but still enable comparability between the samples (Fig. S5). HNA and LNA clusters were distinguished as described above. A new FCM fingerprint parameter, the Cosine dissimilarity score (DS) was developed and applied to each sample measured by the FCM_b (see Statistical Analysis chapter and34). The values obtained from DS calculations were used in further analyses for correlations, time lag calculations and machine learning models.

Total coliforms and E. coli

The most probable numbers (MPN) of total coliforms (TC) and E. coli per 100 mL were assessed by using the IDEXX Colilert Quanti-Tray/2000 test kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ISO 9308-2:201258). In short, 100 mL of sample mixed with defined Colilert-substrate was poured into an IDEXX Quanti-Tray/2000, sealed with Quanti-Tray Sealer and incubated at 36 ± 2°C for 18-22 h. After incubation, the number of large and small wells that showed a colour change (total coliforms) or UV fluorescence (E. coli) were counted and converted to MPN ( ± 95% confidence intervals) using the IDEXX MPN Generator 1.4.4 software.

Bacterial genetic markers

For the molecular quantification of host-associated genetic microbial source tracking markers59 2 to 4 L of water sample was filtered through a 0.2 μm polycarbonate filter with 47 mm diameter. Filters were stored at −80 °C until further processing. DNA was extracted from the filters by a combined phenol-chloroform and bead-beating extraction method42,60 and eluted in 100 μL of 10 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0, 51). These markers comprised the bacterial 16S rRNA gene as general bacterial marker61, AllBac as soil- and faeces-associated marker of the bacterial phylum Bacteroidetes62,63, BacR as ruminant-associated Bacteroidetes-marker according to a previously established probe-based qPCR protocol64 and HF183/BacR287 as human-associated marker65,66. All three qPCR assays were performed on a Rotor-Gene Q thermocycler (Qiagen Inc., Germany) using the Luna Universal Probe qPCR Master Mix (NewEnglands BioLabs GmbH, Germany). Blank filter controls, blank extract (reagents only) controls and no-template qPCR controls were tested with each batch of samples and were consistently negative. Samples were measured in duplicates. Results are expressed as marker equivalents (ME) per 100 mL. As an approximation of the sample limit of detection, we calculated the thresholds of detection for each sample, assuming one copy detected in the qPCR reaction, expressed as ME per 100 mL sample67. The human-associated marker HF183/BacR287 was only detected in 23.8% of the samples (n = 25/105) ranging from 6 to 7.67×102 ME 100 mL-1 without any clear seasonality and was thus omitted from further analyses.

Physico-chemical, hydrological and meteorological data

Water temperature and conductivity of LKAS8 were measured in intervals of 10 min using an automated condu::lyser probe (s::can GmbH, Badger Meter, Austria). Turbidity, UV254, also referred to as spectral absorption coefficient (SAC254), were measured automatically in intervals of 10 min using a spectro::lyser V2 (s::can GmbH, Badger Meter, Austria). All sensors were controlled with parallel single measurements in intervals of 1-4 weeks, using instruments which were part of a certified quality management system of the water supplier30. From this data, hourly averages were calculated using the floor_date function in R (package lubridate) that logs the average between 13:00 and 13:59 to 13:00. A quality check procedure based on the difference to the previous value and visual inspection of time series graphs was developed and all suspicious data was deleted from the database with great care under the dual control principle. Table 1 provides an overview of all parameters measured.

Meteorological data was measured at one weather station in the catchment of LKAS8. Snow height was measured using a USH-9 Ultrasonic level sensor (Sommer Messtechnik, Austria) and rain quantity by using an OTT Pluvio² L Weighing Rain Gauge with 200 cm² collecting area and heating (Ott HydroMet GmbH, Germany). Data on LKAS8 discharge was recovered by in-field online water pressure sensors installed directly at the spring site via the GEALOG-S data collecting system (Logotronic, Austria). Daily sums in [m3 day−1] were calculated from water levels and rating curves.

Statistics and data analysis

Data analysis was performed in R in RStudio68 version 2023.9.0.463, IBM SPSS Statistics (v.25), Python 3.7.3 and Microsoft Excel 2016. All data was visualised using the R package ggplot2 v.3.4.2. Pair-wise Spearman’s correlation coefficients were used to measure linear correlation between two sets of data using IBM SPSS Statistics (v.25) and using the rcorr function from the Hmisc package69 in R, package version 5.2-4. Seasons were defined as follows: spring (March, April, May), summer (June, July, August), autumn (September, October, November), and winter (December, January, February). According to this categorisation, ANOVA with Games-Howell post-hoc tests were performed in SPSS to test for and localise differences between seasons and months. Bland-Altman analysis was used to visually represent the agreement between two bacterial cell quantification methods, identify possible systematic biases and find outliers and was visualised in R.

Cosine Dissimilarity score and Independent Component Analysis: Changes in bacterial populations over the HFS periods 2020 and 2021 were tracked using flow cytometric information derived from FCM_b_FL1, FL2 and SSC channels of the FCM-ICC measurements. To do so, vector signatures of the three-dimensional FCM fingerprint were created and compared to each other using Cosine Similarity, a widely used metric in the machine learning field70, to minimise the differences between the vectors. A threshold value of Cosine Dissimilarity score was set to distinguish between base- and high flow conditions for each data set (HFS 2020 and 2021) and was defined as 8 times the median absolute deviation from the median of the baseline. The Cosine Dissimilarity score is designed to be independent from cell counts with the aim to combine it with other parameters to have an accurate detection method for contamination events. Fingerprints were constructed using a normalised Kernel Density Estimate model applied to the fluorescence (FL1, FL2) and side-scatter (SSC) distributions over a restricted dynamical range. Since embeddings have vector properties, a 2D visualisation via independent component analysis (ICA)32 was chosen to illustrate the variability within the bacterial community during baseflow conditions and compare them to event populations during high flow.

Two machine learning models (Random Forest Classifier and Linear Discriminant Analysis) were implemented to classify E. coli, total coliform, AllBac and BacR values in spring water, as a binary classification of measurement points. The threshold of ≥ 5 MPN 100 mL-1 was used for E. coli and total coliforms, a threshold of ≥102 ME 100 mL-1 for BacR and ≥104 ME 100 mL-1 for AllBac. Stratified sampling as well as k-fold cross-validation was implemented. The input parameters were: turbidity, UV254, FCM_b_TCC, FCM_b_ICC, FCM_b_HNATCC, FCM_b_HNAPTCC, FCM_b_HNAICC, FCM_b_HNAPICC, DSTCC and DSICC. The models were trained and evaluated using all combinations of single and multiple parameters through scikit-learn 0.24.1 and Python 3.7.3.

Data availability

Parts of the LKAS8 datasets generated and analysed during the current study were provided by the relevant water supplier. The data is under restrictions, including a required NDA, and is not available to the public or research community as the area is part of a protected drinking water supply region in Austria. However, data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.The underlying code for FCM fingerprinting and machine learning used in this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Olarinoye, T. et al. Global karst springs hydrograph dataset for research and management of the world’s fastest-flowing groundwater. Sci. Data 7, 1–9 (2020).

Padilla, I. Y., Vesper, D. J. Fate, Transport, and Exposure of Emerging and Legacy Contaminants in Karst Systems: State of Knowledge and Uncertainty. In: White W. B., Herman J. S., K. H. E., Rutigliano M., editors. Advances in Karst Science. Springer International Publishing AG 2018; 2018. p. 33–49.

Chen, Z. et al. The World Karst Aquifer Mapping project: concept, mapping procedure and map of Europe. Hydrogeol. J. 25, 771–85 (2017).

Frank, S., Goeppert, N. & Goldscheider, N. Fluorescence-based multi-parameter approach to characterize dynamics of organic carbon, faecal bacteria and particles at alpine karst springs. Sci. Total Environ. [Internet] 615, 1446–59 (2018).

Vucinic, L., O’Connell, D., Dubber, D., Coxon, C. & Gill, L. Multiple fluorescence approaches to identify rapid changes in microbial indicators at karst springs. J. Contam Hydrol. 254, 104129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2022.104129 (2023).

Besmer M. D., Hammes F., Sigrist J. A., Ort C. Evaluating monitoring strategies to detect precipitation-induced microbial contamination events in karstic springs used for drinking water. Front Microbiol. 2017;8.

Bucci, A., Petrella, E., Celico, F. & Naclerio, G. Use of molecular approaches in hydrogeological studies: the case of carbonate aquifers in southern Italy. Hydrogeol. J. 25, 1017–31 (2017).

Epting, J., Page, R. M., Auckenthaler, A. & Huggenberger, P. Process-based monitoring and modeling of Karst springs – Linking intrinsic to specific vulnerability. Sci. Total Environ. [Internet] 625, 403–15 (2018).

Morasch, B. Occurrence and dynamics of micropollutants in a karst aquifer. Environ. Pollut. [Internet] 173, 133–7 (2013). Available from.

Metcalfe, C. D. et al. Contaminants in the coastal karst aquifer system along the Caribbean coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Environ. Pollut. [Internet] 159, 991–7 (2011).

Sandhu, D. et al. Fate and transport of radioactive gypsum stack water entering the Floridan aquifer due to a sinkhole collapse. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–10 (2018).

WHO. Guidelines for drinking-water quality: fourth edition incorporating the first and second addenda. Geneva: Wo. World Health Organisation. 2022.

Savio, D. et al. Opening the black box of spring water microbiology from alpine karst aquifers to support proactive drinking water resource management. WIREs Water 5, 1–20 (2018).

Farnleitner A. H., et al. Integrated Strategy to Guide Health-Related Microbial Quality Management at Alpine Karstic Drinking Water Resources. In: White W. B., editor. Karst Groundwater Contamination and Public Health: Advances in Karst Science. Springer International Publishing AG 2018; 2018. p. 185–92.

Prest, E. I., Hammes, F., van Loosdrecht, M. C. M. & Vrouwenvelder, J. S. Biological stability of drinking water: Controlling factors, methods, and challenges. Front Microbiol y. 7, 1–24 (2016).

Burnet, J. B. et al. Automation of on-site microbial water quality monitoring from source to tap: Challenges and perspectives. Water Res. 2025;274.

Burnet, J. B. et al. Autonomous online measurement of Β-D-glucuronidase activity in surface water: is it suitable for rapid E. coli monitoring?. Water Res 152, 241–50 (2019).

Ryzinska-Paier, G. et al. A sensitive and robust method for automated on-line monitoring of enzymatic activities in water and water resources. Water Sci. Technol. 69, 1349–58 (2014).

Nescerecka, A., Juhna, T. & Hammes, F. Behavior and stability of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) during chlorine disinfection. Water Res [Internet] 101, 490–7 (2016). Available from.

Højris, B., Christensen, S. C. B., Albrechtsen, H. J., Smith, C. & Dahlqvist, M. A novel, optical, on-line bacteria sensor for monitoring drinking water quality. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–10 (2016).

Besmer, M. D. & Hammes, F. Short-term microbial dynamics in a drinking water plant treating groundwater with occasional high microbial loads. Water Res [Internet] 107, 11–8 (2016).

Page, R. M. et al. Online analysis: Deeper insights into water quality dynamics in spring water. Sci. Total Environ. [Internet] 599–600, 227–36 (2017).

Claveau, L., Hudson, N., Jeffrey, P. & Hassard, F. To gate or not to gate: Revisiting drinking water microbial assessment through flow cytometry fingerprinting. Sci. Total Environ. [Internet] 912, 169138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169138 (2024).

Favere, J., Buysschaert, B., Boon, N. & De Gusseme, B. Online microbial fingerprinting for quality management of drinking water: Full-scale event detection. Water Res [Internet] 170, 115353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2019.115353 (2020).

Sadler, M. C., Senouillet, J., Kuenzi, S., Grasso, L. & Watson, D. C. Computational Surveillance of Microbial Water Quality With Online Flow Cytometry. Front Water 2, 1–12 (2020).

Bruckmann, C., Müller, S. & Höner zu Siederdissen, C. Automatic, fast, hierarchical, and non-overlapping gating of flow cytometric data with flowEMMi v2. Comput Struct. Biotechnol. J. [Internet] 20, 6473–89 (2022). Available from.

Buysschaert, B. et al. Flow cytometric fingerprinting to assess the microbial community response to changing water quality and additives. Environ. Sci. Water Res Technol. 5, 1672–82 (2019).

Koch, C., Fetzer, I., Harms, H. & Müller, S. CHIC-an automated approach for the detection of dynamic variations in complexmicrobial communities. Cytom. Part A 83, 561–7 (2013).

Stadler, H. et al. The spectral absorption coefficient at 254nm as a real-time early warning proxy for detecting faecal pollution events at alpine karst water resources. Water Sci. Technol. 62, 1898–906 (2010).

Reischer, G. H. et al. Hypothesis-driven approach for the identification of fecal pollution sources in water resources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 4038–45 (2011).

Prest, E. I. et al. Combining flow cytometry and 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing: A promising approach for drinking water monitoring and characterization. Water Res [Internet] 63, 179–89 (2014).

Tharwat, A. Independent component analysis: An introduction. Appl Comput Inform. 17, 222–49 (2018).

Wilkinson, M. G. Flow cytometry as a potential method of measuring bacterial viability in probiotic products: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. [Internet] 78, 1–10 (2018).

Egli, T. et al. Domestic hot-water boilers harbour active thermophilic bacterial communities distinctly different from those in the cold-water supply. Water Res [Internet] 253, 121109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2024.121109 (2024).

Brown, M. R. et al. A flow cytometry method for bacterial quantification and biomass estimates in activated sludge. J. Microbiol Methods [Internet] 160, 73–83 (2019). Available from.

Bland, M. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring agreement in methodcomparison studies with heteroscedasticmeasurements. Stat.Methods Med. Res. 8, 135–160 (1999).

Grievson O., Holloway T., Johnson B. A Strategic Digital Transformation for the Water Industry. A Strategic Digital Transformation for the Water Industry. 2022. 1–103 p.

Daniel, I. et al. A survey of water utilities’ digital transformation: drivers, impacts, and enabling technologies. npj Clean. Water 6, 1–9 (2023).

Demeter, K. et al. Automated online monitoring of fecal pollution in water by enzymatic methods. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Heal [Internet] 16, 82–91 (2020).

Mondejar, M. E. et al. Digitalization to achieve sustainable development goals: Steps towards a Smart Green Planet. Sci Total Environ. 2021;794.

Stadler, H. et al. Microbiological monitoring and automated event sampling at karst springs using LEO-satellites. Water Sci. Technol. 58, 899–909 (2008).

Reischer, G. H. et al. Quantitative microbial faecal source tracking with sampling guided by hydrological catchment dynamics. Environ. Microbiol 10, 2598–608 (2008).

Rubbens P., Props R. Computational Analysis of Microbial Flow Cytometry Data. mSystems. 2021;6.

Savio D., et al. From Groundwater to Drinking Water—Microbiology of Karstic Water Resources [Internet]. 2nd ed. Vol. 3, Encyclopedia of Inland Waters. Elsevier Inc.; 2022. 560–579 p. Available from:

Campostrini, L., Proksch, P., Jakwerth, S., Farnleitner, A. H. & Kirschner, A. K. T. Introducing bacterial community turnover times to elucidate temporal and spatial hotspots of biological instability in a large Austrian drinking water distribution network. Water Res [Internet] 252, 121188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2024.121188 (2024).

Savio, D. et al. Spring water of an alpine karst aquifer is dominated by a taxonomically stable but discharge-responsive bacterial community. Front Microbiol. 2019;10.

Wilhartitz, I. C. et al. Heterotrophic prokaryotic production in ultraoligotrophic alpine karst aquifers and ecological implications. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 68, 287–99 (2009).

Paiva, I. & Cunha, L. Characterization of the hydrodynamic functioning of the Degracias-Sicó Karst Aquifer, Portugal. Hydrogeol. J. 28, 2613–29 (2020).

Bradford, S. A., Simunek, J., Bettahar, M., Van Genuchten, M. T. & Yates, S. R. Modeling colloid attachment, straining, and exclusion in saturated porous media. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 2242–50 (2003).

Wang, Y., Hammes, F., De Roy, K., Verstraete, W. & Boon, N. Past, present and future applications of flow cytometry in aquatic microbiology. Trends Biotechnol. 28, 416–24 (2010).

Mermans, F. et al. Opportunities in optical and electrical single-cell technologies to study microbial ecosystems. Front Microbiol. 2023;14.

Egli T., Kötzsch S. Flow Cytometry for Rapid Microbiological Analysis of Drinking Water: From Science to Practice – An Unfinished Story. In: Wilkinson MG, editor. Flow Cytometry in Microbiology: Technology and Applications. Caister Academic Press; 2015. p. 175–216.

Kralik M. Strategie zum Schutz der Karstwassergebiete in Österreich. Umweltbund. Umweltbundesamt GmbH, Spittelauer Lände 5, A-1090 Wien; 2001. 1–99 p.

Kötzsch S., Alisch S., Egli T. Methodenschrift 333.1: Bestimmung der Totalzellzahl und des quantitativen Verhältnisses der Zellen niedrigen bzw. hohen Nukleinsäuregehaltes in Süsswasser mittels Durchflusszytomtrie. Schweizerisches Leb Schweizer Bundesamt für Gesundh. 2012.

Prest, E. I., Hammes, F., Kötzsch, S., van Loosdrecht, M. C. M. & Vrouwenvelder, J. S. Monitoring microbiological changes in drinking water systems using a fast and reproducible flow cytometric method. Water Res 47, 7131–42 (2013).

Claveau, L., Hudson, N., Jarvis, P., Jeffrey, P., Hassard, F. Microbial water quality investigation through flow cytometry fingerprinting: from source to tap. Sustain Microbiol [Internet]. 2024; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/sumbio/qvae003

Hammes, F. et al. Flow-cytometric total bacterial cell counts as a descriptive microbiological parameter for drinking water treatment processes. Water Res 42, 269–77 (2008).

International Organization for Standardization. Water Quality - enumeration of Escherichia coli and coliform bacteria - Part 2: most probable number method (ISO 9308-2:2012). 2012.

Demeter, K. et al. Have genetic targets for faecal pollution diagnostics and source tracking revolutionized water quality analysis yet?. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 47, 1–36 (2023).

Linke, R. B. et al. Identifying Inorganic Turbidity in Water Samples as Potential Loss Factor During Nucleic Acid Extraction: Implications for Molecular Fecal Pollution Diagnostics and Source Tracking. Front Microbiol 12, 1–14 (2021).

Edwards, U., Rogall, T., Blöcker, H., Emde, M. & Böttger, E. C. Isolation and direct complete nucleotide determination of entire genes. Characterization of a gene coding for 16S ribosomal RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 17, 7843–53 (1989).

Layton, A. et al. Development of Bacteroides 16S rRNA gene taqman-based real-time PCR assays for estimation of total, human, and bovine fecal pollution in water. Appl Environ. Microbiol 72, 4214–24 (2006).

Vierheilig, J., Farnleitner, A. H., Kollanur, D., Blöschl, G. & Reischer, G. H. High abundance of genetic Bacteroidetes markers for total fecal pollution in pristine alpine soils suggests lack in specificity for feces. J. Microbiol Methods [Internet] 88, 433–5 (2012). Available from.

Reischer, G. H., Kasper, D. C., Steinborn, R., Mach, R. L. & Farnleitner, A. H. Quantitative PCR method for sensitive detection of ruminant fecal pollution in freshwater and evaluation of this method in alpine karstic regions. Appl Environ. Microbiol 72, 5610–4 (2006).

Green, H. C. et al. Improved HF183 quantitative real-time PCR assay for characterization of human fecal pollution in ambient surface water samples. Appl Environ. Microbiol 80, 3086–94 (2014).

Mayer, R. E. et al. Global Distribution of Human-Associated Fecal Genetic Markers in Reference Samples from Six Continents. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 5076–84 (2018).

Schachner-Gröhs I., et al. Low antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli isolates from two large Austrian alpine karstic spring catchments. Sci Total Environ. 2023;894.

R: Posit team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R [Internet]. Boston, MA: Posit Software; 2023. Available from: http://www.posit.co/

Harrel F. E. J., Beck C., Dupont C. Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous [Internet]. 2025. Available from: https://hbiostat.org/R/Hmisc/

Saeys, Y., Van Gassen, S. & Lambrecht, B. N. Computational flow cytometry: Helping to make sense of high-dimensional immunology data. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 449–62 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the employees the water supplier for optimising the sampling point to our wishes, for actively supporting the sampling and for providing discharge, precipitation, and physico-chemical real-time data. We thank Simone Ixenmaier (TU Wien) for her lab expertise in molecular analyses. We further thank Susann Müller, Florian Schattenberg and Gorkhmaz Abbaszade (UFZ Leipzig) for their valuable insights into flow cytometry fingerprinting. This study was funded by the Eurostars-2 E!12825 MultiSense Aqua project and the ViWa2020+ project. The funder played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript. This study is a joint publication of the ICC Water & Health. The authors acknowledge TU Wien Bibliothek for financial support through its Open Access Funding Programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. and A.F. designed the study and acquired the funding. L.C., K.D., R.L., S.J., S.P. and A.K. designed the experiments and oversaw the practical implementations with inputs of M.S., J.D., M.Z. and A.F. Fieldwork was done by L.C., K.D., G.L., A.P., S.J., S.P. and A.K. L.C., R.L., A.P. and S.J. conducted experimental lab work. Data curation, processing, analyses and visualisation were performed by K.D., L.C., A.P. and A.S. L.C., K.D., A.F. and A.K. wrote the manuscript with direct contribution, edits, and critical feedback by all authors. A.P., L.G., A.S. and M.S. wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors revised, read and approved the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors LG and AS report a relationship with bNovate Technologies, SA that includes: employment, but declare no non-financial competing interests. All other authors declare no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Campostrini, L., Demeter, K., Linke, R. et al. Performance of on-site flow cytometry for near-real-time microbiological analysis of alpine karst drinking water resources. npj Clean Water 9, 6 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00536-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00536-5