Abstract

Oily wastewater presents a serious environmental challenge, demanding sustainable and regenerative membrane technologies. Here, we report a green and scalable method for fabricating skin-replaceable cellulose membranes (SRC-M) from jute agro-waste, using a NaOH/urea activation route and argon-pressurized deposition onto ceramic supports. The resulting Cellulose II-based asymmetric membranes exhibit high water flux (~470 L m⁻²h⁻¹) and >98% oil rejection across various emulsions. Notably, the membrane’s surface can be fully renewed via ultrasonication, restoring >99% of the original flux after 16 fouling cycles. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations confirm the thermodynamic stability (ΔG = -0.162 eV) and low kinetic barrier (0.46 eV) of urea adsorption on cellulose, supporting the dissolution mechanism and regeneration behavior. This biodegradable, self-renewable membrane system offers a robust, circular solution for long-term oily wastewater remediation and aligns with green chemistry principles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oily wastewater is a complex mixture with a diverse physicochemical composition, generated by several industries, particularly the petroleum industry, where each barrel of crude oil can produce up to 10 barrels of wastewater1,2. These effluents are particularly challenging to treat due to the presence of emulsified oil droplets (<10 to 20 µm)1,3, surfactants, heavy metals, and bulk organic compounds. Notably, conventional separation techniques often struggle to eliminate stable emulsions effectively. While advanced remediation methods, such as chemical demulsification and adsorption, have achieved promising results, their wide-scale application is hindered by high costs, the recyclability of materials, and secondary pollution4,5. Porous electrodes have also been reported for the electro-degradation of the organic contaminants6. In the last decade, membrane-based separations have been extensively investigated as a promising alternative due to their high efficiency, selectivity, and scalability7,8,9. Therefore, the membrane-based technology is rapidly emerging for a range of applications10,11.

Polymeric membranes have been predominantly used in water and wastewater treatment, owing to their excellent separation capabilities. However, the high fouling propensity of polymeric membranes remains the major obstacle12. This problem arises mainly from their inherent hydrophobic nature, which results in rapid fouling by oil and organic contaminants, consequently reducing permeability and shortening their lifespan13,14. To address this, significant efforts have been devoted to developing membranes with engineered wettable surfaces for mitigating oil adhesion and aiding in de-emulsification15,16,17,18. These membranes are typically synthesized from complex materials such as nanoparticles, metal meshes, or advanced polymers19,20. Despite their advanced design, these membranes eventually experience fouling and require replacement. This highlights the urgent need for membranes developed from alternative polymers, which are (i) naturally hydrophilic, (ii) biodegradable, and (iii) cost-effective.

In natural environments, highly efficient separation modules exist in biological systems, such as ion-selective water channels in plant roots or hydrophobic, gas-permeable lotus leaves. These natural systems have inspired the development of a new category of bio-inspired materials, which aim to replicate the sustainability, functionality, and efficiency observed in nature. In the field of separation science, bio-inspired materials have been increasingly recognized as promising solutions for environmental remediation and alleviating membrane fouling21. In this context, naturally occurring polymers have gained attention as environmentally friendly, scalable, and sustainable alternatives to synthetic polymers. Among these, cellulose stands out as the most abundant biopolymer on Earth, known for its exceptional properties, including biodegradability, hydrophilicity, and mechanical strength. Importantly, the presence of surface hydroxyl groups in cellulose not only makes it hydrophilic but also allows for chemical modification22. The unique wetting characteristics of cellulose, its hydrophilic behavior in air and oleophobic nature when submerged, make it especially well-suited for applications in oil–water separation23,24. Its oleophobic behavior underwater can be attributed to a hydration layer formed by hydroxyl groups, which effectively repels oils and provides an antifouling surface23,24.

Compared with polymeric supports, ceramic membrane supports offer superior mechanical, thermal, and chemical stability, enabling reliable operation under harsh wastewater conditions. Ceramic substrates are inherently hydrophilic and typically exhibit greater resistance to fouling25, facilitating easier cleaning and repeated reuse. Nevertheless, fouling propensity remains sensitive to operating conditions26. The ceramic membrane can withstand higher temperatures than the polymeric one27. These attributes make ceramics particularly well-suited for treating oily wastewater and justify their selection as robust, durable supports for bio-derived cellulose barrier layers.

This natural affinity for water and resistance to oil should make cellulose an ideal candidate for developing bio-inspired membranes. However, transforming cellulose into membranes remains a significant challenge. Native cellulose is characterized by a high degree of crystallinity and limited solubility in both water and common organic solvents28. Although certain ionic liquids have been found to dissolve cellulose, their high cost, toxicity, and the complexities involved in recycling hinder their widespread industrial use. Environmentally friendly solvent systems, particularly aqueous NaOH/urea mixtures, have been identified as promising alternatives29,30. These systems can disrupt hydrogen bonds in cellulose and facilitate membrane regeneration under mild conditions31. However, due to a lack of studies on successful oil-water separation, a significant research gap exists in developing stable and superior cellulose-based membranes extracted from real plant biomass and processed using NaOH/urea.

To address this research gap, the present study investigates the potential of a rapidly growing and widely available tropical plant’s byproduct (jute stick) as a sustainable source of high-quality cellulose (Fig. 1)32,33,34. Despite its extensive production and extremely low cost, the jute stick has not been reported to be commonly used in membrane technology. The cellulose extracted from jute is expected to exhibit excellent compatibility with the NaOH/urea solvent system and form a thin barrier layer on a ceramic membrane support using a simple argon-pressurized dead-end filtration method. The membranes developed using our method are expected to exhibit high permeability and effective oil-water separation, due to their super-hydrophilic and underwater oleophobic properties. In addition to experiments, DFT simulation reveals that urea adsorption on cellulose is thermodynamically and kinetically advantageous, supporting dissolution and membrane formation. Based on a concept inspired by biological systems, this study introduces a significant advancement with the development of a skin-replaceable cellulose membrane (SRC-M) that can be generated using a robust method for multiple cycles. Specific questions that this study addresses are as follows: (i) Is it possible to sustainably extract high-purity cellulose from jute and convert it into membranes using an affordable, eco-friendly solvent system? (ii) How well does cellulose derived from jute, dissolved in NaOH/urea, perform in designing stable and uniform barrier layers that are effective for oil-water separation? (iii) Our DFT simulations support the formation and stability of the cellulose membranes (iv) What are the oil-repellent, hydrophilic, and antifouling characteristics of the resulting cellulose membranes under realistic conditions? (v) Can a membrane architecture with a replaceable skin offer a practical solution to ongoing fouling issues and facilitate efficient membrane regeneration? Overall, this study presents a bio-inspired, green membrane technology that utilizes jute-derived cellulose and a recyclable solvent system to address the dual challenges of treating oily wastewater and mitigating membrane fouling. This technology features a robust, skin-replaceable architecture that aligns well with material science and environmental sustainability.

Results and discussion

Cellulose dissolution process for membrane fabrication

Cellulose extracted from the jute plant could not be processed into membranes using water or common organic solvents. Moreover, many organic solvents typically used in polymeric membrane fabrication are highly toxic and environmentally hazardous. The high crystallinity of cellulose makes it inherently rigid and resistant to dissolution, hindering its ability to form uniform or thin films via conventional membrane fabrication methods such as casting or phase inversion. This poor solubility is primarily due to the extensive hydrogen-bonding network within cellulose, which limits its dispersion and prevents the formation of homogeneous solutions, which are essential for successful membrane fabrication. Therefore, the processability of cellulose was enhanced using the NaOH/urea system, and the dissolution process was performed in water, eliminating the need for toxic or harmful organic solvents.

Cellulose dissolution in aqueous NaOH/urea systems is facilitated by a synergistic disruption of the hydrogen bond network that stabilizes the crystalline structure of cellulose I. NaOH interacts principally with the intramolecular hydrogen bonds within cellulose chains, causing chain swelling and partial disruption of the crystalline structure. At the same time, urea specifically disrupts intermolecular hydrogen bonds by forming stable hydrogen bonds with hydroxyl groups in cellulose35,36. The presence of urea prevents the reaggregation of dissolved cellulose chains, thereby promoting solubility. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis revealed an exothermic interaction during dissolution, indicating the formation of a bond between cellulose and the solvent molecule37. DFT calculations also supported the formation of double hydrogen bonds between urea and cellulose chains, with a Gibbs free energy change of –39.2 kJ/mol, indicating a favorable interaction37.

Upon regeneration in water, the dissolved cellulose chains reorganize antiparallel in a manner characteristic of cellulose II (Fig. 2a). XRD measurements confirmed the structural transformation by the disappearance of cellulose I diffraction peaks and the appearance of peaks due to cellulose II36. The transformation results in lower crystallinity, increased hydrophilicity, and greater flexibility in regenerated cellulose membranes, which are favorable for high-flux oil–water separation.

a Dissolution of cellulose I in NaOH/Urea solution and regeneration to cellulose II. b Optimized adsorption geometry of a urea molecule on the polycellulose surface, highlighting the most stable configuration. c Plane-averaged charge density difference (Δρ) along the z-direction, indicating electron depletion on the urea molecule and accumulation on the cellulose substrate; inset shows the corresponding iso-surface plot (yellow = accumulation, cyan = depletion). d Initial and final configurations used in the climbing-image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) calculation. e Calculated minimum energy pathway showing a surface diffusion barrier of approximately 0.46 eV for urea migration on polycellulose.

DFT calculations were performed to provide a comprehensive atomic-level understanding of the interaction between the urea molecule and the cellulose surface. To accurately mimic the extended nature of a cellulose substrate, the cellulose structure was periodically extended along the a-axis. To mitigate spurious interactions between adjacent periodic images of the urea molecule, a minimum intermolecular distance of approximately 10 Å was maintained along the b-axis. A systematic exploration of twelve distinct adsorption sites revealed the most stable configuration, which is depicted in Fig. 2b. The calculated adsorption energy for urea on the cellulose surface was determined to be −0.64 eV, signifying a strong and thermodynamically favorable interaction. To further validate the spontaneity of this adsorption process, the Gibbs free energy (ΔG) is calculated. Under standard conditions (298 K, 1 atm), the obtained ΔG value of -0.162 eV confirms that urea adsorption on cellulose is both spontaneous and thermodynamically stable.

To elucidate the electronic rearrangements accompanying adsorption, the charge density difference (CDD) was analyzed (Fig. 2c). The CDD line plot exhibits a pronounced negative dip at the cellulose surface (~6 Å) and a positive peak beneath the urea, indicating net electron transfer from urea to the polymer. The iso-surface plot of the CDD (inset of Fig. 2c) further corroborates this observation, visualizing electron density accumulation on the cellulose surface and a corresponding depletion from the urea molecule, which collectively contribute to the enhanced stability of the adsorbed system.

Beyond thermodynamic favorability, the kinetic accessibility of the adsorption process was assessed by computing the energy barrier using the Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method38. Figure 2d illustrates the initial (most stable adsorbed configuration) and final (transition state) configurations, with four intermediate images generated to trace the reaction pathway. The calculated energy barrier, depicted in Fig. 2e, was determined to be 0.46 eV. This relatively low energy barrier suggests that the adsorption process is not only thermodynamically favorable but also kinetically accessible under ambient conditions. Collectively, these DFT results demonstrate that urea adsorption on polycellulose is a spontaneous, thermodynamically stable, and kinetically viable process, primarily driven by favorable electronic interactions and charge transfer mechanisms. Such robust and stable binding of urea, coupled with resistance to desorption, represents a highly desirable feature for membrane applications.

Furthermore, the OH treatment results in breaking the bulk cellulose fibers into individual strands, and the urea molecules are bound to the strands, which we have found prevents them from agglomerating into bundles. To investigate this further, we have quantified the strength of the intermolecular hydrogen bonding within bulk cellulose and urea binding to the single strands using DFT. Physical binding energies were determined through an electron localization function (ELF) analysis. The ELF offers a topological measure of electron localization, where minima along O–H···O interaction paths correspond to saddle points between valence basins and can be directly related to physical binding energies. Figure 3 shows the ELF isosurfaces together with line profiles for bulk cellulose (Fig. 3a, b) and the urea@polycellulose complex (Fig. 3c, d). In both cases, a clear ELF saddle point emerges along the hydrogen-bond path, marked by the dashed circles in the profiles. For bulk cellulose, the minimum ELF value for the strongest O···H bond was found to be 0.094, which translates, via the linear ELF–binding energy relationship established in our previous work39,40 to a binding energy of −0.186 eV. For the urea@polycellulose system, the ELF minimum has a larger value, 0.100, corresponding to a binding energy of −0.198 eV. Since urea interacts more strongly with the cellulose strands than the interaction between strands, urea effectively blocks agglomeration into bundles, and the filtering capacity can be maintained over several uses and washes (Fig. 3).

Characterization

The SRC-3-CM and the surface of p-CM were characterized by FTIR, SEM, and XRD. The FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy) spectrum of the SR (Fig. 4a) contained typical cellulose absorption peaks, i.e., a wide O–H stretching band at ~3340 cm⁻¹, a C–H stretching band at ~2900 cm⁻¹, and a strong C–O–C stretching vibration at ~1060 cm⁻¹. These indicate the presence of cellulose, preserving the significant functional groups responsible for hydrophilicity. The absence of peaks for lignin and hemicellulose ensures the purity of the cellulose layer extracted from jute. The surface hydrophilicity provided by hydroxyl groups is crucial for oil–water separation, as it enables the selective transport of water and the formation of an underwater oleophobic interface4,36.

a FTIR spectrum was scanned in the range of 500–4000 cm–1, and b XRD pattern of the SRC-3-CM. The data were recorded over a 2θ range of 3°–80°. c Cross-sectional SEM images of the free-standing cellulose separating layer. SEM micrographs of the surfaces of the (d) p-M and e SRC-3-CM. f TEM image of the cellulose extracted from the jute stick.

Figure 4b indicates the XRD pattern of SRC-3-CM with strong peaks at 2θ ≈ 12.1°, 20.1°, and 21.8°. These are corresponding characteristic diffraction planes [1̅10], [110], and [020] of Cellulose II. Apart from Cellulose II, some of the diffraction peaks of the alumina substrate were also observed at 38.3, 44.6, and 65.0°, which can be assigned to the diffraction planes of [110], [113], and [214] (PDF#10–0173)41,42. The transformation from cellulose I to cellulose II is typical of dissolution processes, particularly in alkali-based or ionic liquid systems43. Cellulose II is less crystalline than cellulose I and therefore renders the membrane more flexible and may also be responsible for enhanced water permeability through greater free volume and reduced transport resistance44.

Figure 4c shows the cross‑sectional SEM micrograph of the free‑standing cellulose separation layer, indicating that water‑processed cellulose forms a compact, well‑consolidated membrane. The surface SEM image of p‑M (Fig. 4d) reveals randomly packed alumina particles that produce irregular pore sizes and a rough surface. After formation of the cellulose skin layer, the surface becomes markedly smoother (Fig. 4e). Atomic force microscopy (AFM) validates these observations: p‑M exhibits a high arithmetic mean surface roughness (Sa) of 880 nm (Fig. 5a), whereas the cellulose‑coated membrane shows a reduced Sa of 545 nm (Fig. 5b). Consistent with the SEM images, SRC‑3‑CM is smoother than p‑M.

Figure 4e, f illustrates the asymmetry of the membrane’s structure. The upper selective layer, having a thickness of approximately 4.9–5.8 µm, is dense and serves as the primary filtration barrier. A more open substructure lies below this, providing mechanical support and facilitating fast water transport. Asymmetric structures are typically employed in high-performance membranes due to their balance of selectivity and permeability45,46. The thin selective layer minimizes resistance to water permeation, and the porous base improves mechanical strength and backpressure tolerance, which is an essential need in pressure-driven membrane processes like ultrafiltration47. Based on this characterization, it is clear that the free-standing cellulose separating layer is well-structured and likely to exhibit high separation efficiency, provided the required mechanical stability is achieved. FTIR and XRD measurements confirm the chemical and structural stability of the cellulose layer. SEM micrographs display a denser, fibrous structure with superior oil-water separation efficiency compared to the virgin p-CM membrane. TEM images have revealed both fiber-like (Fig. 4f) and sheet-like morphologies of cellulose after dissolution (Fig. S1). The EDX has also shown the sharp presence of C and O, indicating that the surface of the ceramic membrane is completely covered with the jute-derived cellulose (Fig. S2). Photographs of biomass-derived cellulose and SRC are shown in Fig. S3.

Surface wettability analysis

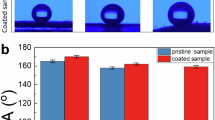

The wettability characteristics of the membranes were evaluated using static water contact angle (WCA) measurements in air and underwater oil contact angle (UWOCA) measurements, as shown in Fig. 6. Contact angle is the geometrical measurement of the wetting behavior of the surfaces with a certain liquid, and the contact angle of the liquid is measured at the three-phase boundary where the solid, liquid, and gas intersect. The measurements are crucial for revealing the surface interaction behavior of the membranes with water and oil, which in turn determines their applicability in oil–water separation and resistance to fouling. Various models, including Young’s model (Eq. (1)), the Wenzel model (Eq. (2)), and the Cassie–Baxter model (Eq. (3)), explain the liquid contact angle on different surfaces.

UWOCA measurements on the surface of the membranes for a p-M, b SRC-1-M, c SRC-2-M, d SRC-3-M, e SRC-4-M, f SRC-5-M, and g Comparative histograms of UWOCA values. h WCA measurements in air for all membranes, indicating trends in hydrophilicity. Error bars in g and h represent the standard deviation. All CA measurements were performed with a 5 µL droplet at room temperature.

Young’s model explains the contact angle on smooth surfaces, where γLV, γSV, and γSL denote the interfacial tensions of the liquid-vapor, solid-vapor, and solid-liquid interfaces, respectively. The Young Equation applies when the surface is chemically homogeneous and topographically smooth; however, surfaces are not perfectly smooth and chemically homogeneous. Wenzel explains that surface roughness is a crucial factor, and increasing surface roughness enhances wettability; surface chemistry plays a critical role in this process. The Wenzel contact angle can be measured using Eq. (2), where r is the roughness factor. Wenzel’s model states that roughness amplifies the intrinsic wettability of a surface, enhancing hydrophilicity on hydrophilic surfaces and hydrophobicity on hydrophobic ones. Furthermore, the Cassie–Baxter model is proposed for a more complex, heterogeneous, and rough surface, as explained in Eq. (3)48. Figure 6a–g illustrates the underwater oil contact angle (UWOCA) of the original membrane (p-M) and free-standing cellulose separating layer (SRC-1-M to SRC-5-M). In contrast, Fig. 6h illustrates water contact angles (WCA) in air. The membrane surfaces are hydrophilic when WCA < 90° and hydrophobic when WCA > 90°. A WCA < 10° indicates superhydrophilicity, whereas an oil contact angle (OCA) > 150° reflects superoleophobicity. These contact angle measurements are crucial in evaluating the wettability and antifouling properties of membranes used in oil–water separation applications.

The pristine ceramic membrane (p-M) presented relatively low UWOCA of approximately 140°, indicating medium underwater oleophobicity (Fig. 6a). However, it has been observed that creating an SRC separating layer on the ceramic support membrane substantially improves underwater oleophobicity. For SRC-1-M to SRC-2-M, the membranes have shown UWOCA values exceeding 150°, reaching a maximum of 153° for SRC-3-M and SRC-4-M (Fig. 6b–f, g). These values indicate a transition towards an underwater super-oleophobic state, which can play a crucial role in enhancing the membrane performance in terms of selectivity and fouling resistance49. This is primarily a result of the existence of abundant hydrophilic hydroxyl groups on the surface of skin-replaceable cellulose membrane (confirmed by FTIR), along with the increased surface roughness observed in SEM analysis (Fig. 4d). Together, these two features enable the formation of a stable hydration layer at the interface, serving as a physical and energetic barrier against the adhesion of oil droplets50.

The WCA has demonstrated the inherent hydrophilicity of the SRC barrier layer (Fig. 6h). Nearly all SRC-M samples exhibit comparable WCA owing to their identical surface chemical properties. Increasing the cellulose loading improves membrane wettability, as evidenced by a decrease in the WCA. This reduction is attributed to the greater availability of surface hydroxyl groups, which promote hydrogen bonding with water and further lower the WCA. Cellulose’s intrinsic hydrophilicity allows for rapid water spreading and permeation through the membrane. This reduced WCA may be attributed to the more porous, roughened structure of the SRC-M, which enhances surface hydrophilicity via the Wenzel effect. Interestingly, SRC-3-M and SRC-4-M exhibited slightly lower water contact angles (WCAs) than SRC-5-M (Fig. 6h). Because SRC-3 to 4 & 5 denote increasing cellulose loading, this trend can be attributed to load-dependent changes in surface morphology. At intermediate loadings (SRC-3-M and SRC-4-M), the cellulose layer forms an optimally porous and highly hydrated surface that maximizes the accessibility of surface hydroxyl groups and enhances hydrophilicity. At the highest loading (SRC-5-M), additional deposition produces a denser, smoother coating that partially shields hydrophilic sites and diminishes roughness-assisted wetting, resulting in a modest increase in WCA. Enhanced hydrophilicity not only improves selective water permeability but is also essential for achieving underwater oleophobicity, making it a crucial factor in designing high-performance separation membranes51. Hydrophilic membranes not only promote preferential water permeation but also resist oil fouling due to their low interfacial energy with water. Such synergistic performance, with low WCA in air and high UWOCA, confirms the dual-wetting nature required for effective and selective oil–water separation membranes52. The demonstrated wettability features, i.e., high UWOCA ( >150°) and low WCA ( <10°), serve as indicators of the membrane’s ability to separate oil from water with minimal fouling. This performance, owing to its surface morphology and chemistry, supports the membrane structure in achieving sustainable separation of oil from water and aligns with recent advances in cellulose-derived Janus and superwetting membranes53,54.

Oil–water separation performance

The separation performance of the SRC-M was evaluated using oil-in-water emulsions at model concentrations of 250 ppm and 500 ppm. Figure presents the membranes’ permeation flux and separation efficiency, providing a comprehensive visual confirmation of oil removal. Figure 7a presents the permeation flux of various membranes, showing an apparent trend: the flux decreased at higher emulsion concentrations due to greater oil loading and emulsion viscosity, both of which hindered water transport. Within the series, SRC-1-M exhibited the highest flux (~2000 L m–2 h–1), but with modest separation performance. The flux decreased systematically with increasing cellulose loading, with SRC-3-M balancing the flux (~486 L m–2 h–1) and demonstrating excellent separation efficiency. In particular, the SRC-3-M exhibited a high-water flux of ~480 L m–2 h–1 for 250 ppm emulsions and maintained an intense flux even at high concentrations (500 ppm), revealing excellent hydraulic performance. Figure 7b illustrates the separation efficiencies of the pristine membrane and the various SRC membrane series. The separation efficiency was poor with the pristine membrane due to its uncontrolled pore size; however, the separation efficiency improved substantially after the formation of the SRC barrier layer. SRC-3-M exhibited the best separation performance, with an efficiency of over 97.9% at 250 ppm and greater than 96% at 500 ppm, indicating that the membrane structure and surface properties were optimized for rejecting submicron oil droplets while maintaining a substantially high permeability.

Separation performance of various membranes for 250 ppm and 500 ppm oil-in-water emulsions: a permeation flux; b separation efficiency. Performance of SRC-3-M in separating different oil-in-water emulsions. Separation performance of various membranes for 250 ppm and 500 ppm oil-in-water emulsions: a permeation flux; b separation efficiency. Performance of SRC-3-M in separating different oil-in-water emulsions: c permeation flux and separation efficiency. Optical images of feed and permeate for various membranes: d overview; e p-M; f SRC-1-M; g SRC-2-M; h SRC-3-M; i SRC-4-M.

Therefore, the SRC-3-M is regarded as the optimal membrane for separating oil-in-water emulsions, offering high separation efficiency while maintaining high permeability. The SRC-3-M membrane’s versatility and effectiveness were tested with various types of oil-in-water emulsions (Fig. 7c). SRC-3-M has demonstrated high performance and permeability in separating vegetable oil-in-water and toluene-in-water emulsions, achieving separation efficiencies of 99.5% and 96.9%, respectively. Meanwhile, the membrane maintained a high flux (>400 LMH). These results are comparable to those reported in the literature for other bio-based membranes55,56. Microscopic optical images of the emulsions before and after separation also validate the membrane performance (Fig. 7d–i). The feed emulsion (Fig. 7d) exhibits a dense dispersion of emulsified oil droplets, whereas the permeate from SRC-1-M to SRC-4-M (Fig. 7i) is almost optically transparent, with fewer droplets present, indicating significant oil rejection. The permeate from the pristine membrane (Fig. 7e) shows visible residual oil. Thus, optical images agree with the quantitative rejection data. The camera photographs and the permeate are shown in Fig. S4.

The high flux and selectivity of SRC-3-M demonstrate the successful transformation of the biomass-derived cellulose into a membrane. In the literature, it has been reported that bio-based ultrafiltration membranes, where cellulose’s asymmetric structure provides low transport resistance while ensuring mechanical integrity and stability46. On the surface of SRC-3-M, the cellulose fibrous network self-organizes into a tight, porous matrix that effectively screens emulsified oil droplets. The abundance of hydrophilic functional groups, primarily hydroxyl (-OH) groups, establishes a robust hydration layer at the membrane-water interface. This hydration layer plays a crucial role in destabilizing and rejecting emulsified oil droplets, facilitating their separation from the water phase.

As the oil droplets are released from the emulsion, the hydration layer repels them, preventing them from adhering to the membrane surface. Simultaneously, the hydrophilic groups in the cellulose matrix enable rapid, selective water permeation, ensuring high flux and separation efficiency. Furthermore, the hydration layer formed by the hydroxyl-rich cellulose surface imparts underwater superoleophobicity, which resists oil adsorption and accumulation. This characteristic significantly enhances the antifouling properties of the membrane, making SRC-3-M particularly effective for long-term operation in oil-water separation applications49,57.

Fouling resistance and skin regeneration for restoring membrane performance

The long-term operational stability and antifouling performance of membranes are critical for achieving sustainable and cost-effective wastewater treatment. The fouling characteristics of the SRC-3-M membrane were studied extensively by subjecting it to multiple filtration and cleaning cycles with 200 ppm oil-in-water emulsions. The results are shown in Fig. 8a–d. As shown in Fig. 8a, a negligible decline in flux was observed during the first 16 filtration cycles due to the accumulation of oil droplets and membrane fouling. The high fouling resistance of the SRC-3-M is evident through a negligible decline in flux. After 16 cycles, the SRC-3-M maintains flux above 80% of its original value, indicating moderate but manageable fouling. The flux recovered to 93% of its original value after physical rinsing and keeping in water. Compared to the SRC separating layer, other polymeric membranes, such as PVDF, are severely fouled and exhibit poor flux recovery12. The high flux recovery indicates the formation of a stable hydration layer, attributed to the abundant hydroxyl groups present in the cellulose matrix. This hydration layer plays a crucial role in inhibiting the formation of a dense or compact cake layer and minimizing oil adsorption on the membrane surface. It functions as a physical and energetic barrier, effectively weakening van der Waals interactions between the foulants and the membrane surface, thereby enhancing antifouling performance50,51. In addition to hydration‑layer effects, the electrostatic properties of the cellulose surface play a key role in antifouling. At neutral pH, the cellulose membrane is negatively charged, and SDS produces negatively charged oil droplets; their mutual electrostatic repulsion, combined with the stable hydration layer provided by surface hydroxyl groups, effectively limits oil adhesion and pore blockage, thereby improving the antifouling behavior of SRC‑3‑M.

a Permeation flux and flux recovery ratio during filtration cycles; b separation efficiency for 200 ppm oil-in-water emulsions; c permeation flux and d separation efficiency after ultrasonic removal and renewal of the skin layer. In an underwater oil fouling study e–l, the membrane surface moves towards the underwater oil droplet m–t, while the membrane surface moves away from the underwater oil droplet.

Separation efficiency data in Fig. 8b shows a slight variation over all cycles, with the efficiency remaining above 95% even after repeated fouling and rinsing. This suggests that, despite particulate and oil build-up, the selective barrier layer remains effective over the long term, as evidenced by the mechanical and chemical integrity of the regenerated membrane. From the literature, it is well established that membrane fouling is inevitable during long-term operation. While surface modifications and material innovations can delay the fouling, they cannot eliminate it58,59. Eventually, the accumulation of foulants leads to a decline in performance, often necessitating the replacement of the entire membrane module, a major contributor to the overall operational cost in membrane-based systems. To address this issue, we introduce a cost-effective and sustainable skin-replaceable strategy based on the SRC-3-M membrane design. In this configuration, the ceramic substrate, which is the most expensive and durable component, remains permanently intact. At the same time, the functional separation layer, composed of bio-derived cellulose extracted from jute, can be easily replaced. Cellulose, being abundant, renewable, and low-cost, serves as an ideal candidate for this modular design approach. When the cellulose layer becomes fouled, it can be removed through a simple sonication-based delamination process. A fresh cellulose solution can then be re-deposited onto the ceramic support using pressure-driven casting or vacuum filtration, effectively restoring membrane performance without replacing the entire module. To experimentally validate this approach, we performed repeated skin regeneration cycles on fouled membranes. As illustrated in Fig. 8c, the normalized flux was approximately recovered after each skin replacement cycle (SR-1 to SR-5), matching the performance of the original pristine membrane (SR-0). Furthermore, Fig. 8d shows that the separation efficiency remained consistently high (~98%) across all regeneration cycles, confirming that the restoration of the cellulose barrier layer did not impact the selectivity. This skin-replaceable strategy not only significantly reduces operational and maintenance costs but also enhances the longevity and sustainability of the membrane system, offering a scalable and eco-friendly solution for long-term oil-water emulsion separation.

The skin-layer replacement provides a solution to delay membrane module replacement; however, as discussed above, the developed cellulose barrier layer itself shows good resistance to fouling. However, separating the oil-in-water emulsion is a complex process, and oil droplets in the emulsion can foul the membrane60 via various mechanisms during filtration. One primary fouling mode is pore blocking, where oil droplets become trapped within the membrane pores, reducing permeability. Another common mechanism is cake layer formation, wherein oil droplets accumulate on the membrane surface, forming a thick, cohesive layer that hinders flow. Additionally, oil adsorption onto the membrane surface can occur, further contributing to irreversible fouling. The extent of fouling is strongly influenced by the affinity of the membrane surface for oil. Membranes with hydrophobic surfaces tend to attract and retain oil droplets due to hydrophobic-hydrophobic interactions, often resulting in persistent and irreversible fouling. Therefore, the surface chemistry of the membrane is a crucial factor in determining its resistance to fouling.

To assess the underwater oil resistance of the SRC-M membrane, a chloroform oil droplet was generated underwater using a software-controlled syringe. The membrane was gradually moved toward the suspended oil droplet until initial contact was made. In cases where the membrane surface is hydrophobic, the oil typically spreads or adheres to the surface upon contact. However, for the SRC-M membrane, the oil droplet remained intact at the point of first contact, showing no signs of spreading or adsorption. As the membrane continued to move forward, the oil droplet was gently pressed against its surface. Though deformation of the droplet was observed due to compression, the membrane still did not exhibit any oil adsorption (Fig. 8e–l). When the membrane was slowly retracted, the pressure on the droplet was released, and the oil began to regain its original spherical shape. Ultimately, as the membrane moved away, the droplet remained adhered to the syringe needle, while the membrane surface showed no interaction or retention of oil. The droplet and the membrane cleanly separated without resistance (Fig. 8m–t), demonstrating excellent underwater oil repellence (Video S1).

The excellent antifouling performance of the SRC-3-M in this study can be attributed, partially, to the formation of a firmly attached hydration layer at the membrane-water interface. As thoroughly reviewed by Zhang et al.49, super-hydrophilic and underwater super-oleophobic surfaces effectively prevent oil adhesion by forming a dense, ordered water layer on the membrane surface. This water layer also acts as an energetic and physical barrier, restricting direct contact between foulants (such as oil droplets) and the membrane, thereby decreasing the thermodynamic driving force for adhesion (Fig. 9). In this study, jute-derived cellulose membranes exhibited water contact angles of less than 10° and underwater oil contact angles of more than 150°, indicating superhydrophilicity and underwater superoleophobicity (Fig. 6). It results in the spontaneous formation of a hydration shell due to intense hydrogen bonding between cellulose hydroxyl groups and water molecules. The hydration layer supports selective water permeation and inhibits oil intrusion, as evidenced by steady separation efficiencies (>97%) and minimal flux loss across repeated cycles (Fig. 8).

a, b The hydroxyl groups (-OH) on the membrane surface capture and immobilize water molecules through hydrogen bonding, forming a dense hydration layer. b The stabilized hydration layer prevents direct contact between oil droplets and the membrane. c The hydration shell favors selective water permeation and repels oil droplets in the bulk water phase, thereby enhancing antifouling and oil rejection performance when filtering oil-in-water emulsions.

Table 1 compares the performance of SRC-3-M membranes with other reported membranes for oil-in-water emulsion separation, highlighting their superior separation efficiency and flux. As illustrated in the radar plot (Fig. 10), the SRC-3-M membrane (denoted as “This work”) demonstrates superior overall performance in oil-in-water emulsion separation, exhibiting the highest permeability (487 LMH/bar), excellent rejection (98%), high flux recovery ratio (FRR, 99%), and skin replaceability. Compared to previously reported membranes, SRC-3-M achieves a more balanced and enhanced performance profile across all four metrics, with skin replaceability quantitatively represented as 1 for “Yes” and 0 for “No” for comparative clarity.

Additionally, the hierarchical roughness of SRC-3-M, as observed in SEM micrographs, enhances the stability of the hydration layer by providing a higher surface area and increasing the number of anchoring sites for water molecules. The synergy between surface chemistry (hydrophilic hydroxyl groups) and surface topology (micro/nano-roughness) contributes to the membrane’s sustained and stable antifouling behavior. This is why SRC-3-M can be considered a robust and efficient antifouling membrane, capable of maintaining performance under challenging operational conditions.

From a scalability viewpoint, the process used here for membrane fabrication can be applied to large scale production by using spray assisted deposition or pressure driven coating industrial systems. Nitrogen gas or compressed air can be used instead of argon gas during pilot scale production while maintaining membrane performance. Moreover, the NaOH/urea solvent can be reused by filtration and adjusting pH again which will be reduce the industrial cost production. The main obstacles for industrial deployment include maintaining uniform cellulose deposition across large membrane surfaces and ensuring efficient solvent recovery; both can be addressed by incorporating automated layer-casting units and closed-loop solvent recovery systems. Overall, these points demonstrate that the process aligns well with principles of scalable, environmentally friendly manufacturing for cellulose-based membranes. Overall, the results of this work highlight the implication of the jute-derived cellulose membranes for sustainable oily wastewater treatment, as summarized below.

This study presents a comprehensive, sustainable, and scalable approach for fabricating high-performance, antifouling, and regenerable membranes for oily wastewater treatment using cellulose derived from jute sticks. By valorizing jute agro-waste, a widely available, renewable, and low-cost biomass, we have demonstrated an environmentally friendly membrane fabrication strategy that aligns with the principles of green chemistry and the circular economy. A central challenge in utilizing cellulose for membrane applications, namely its poor processability, was effectively overcome through an aqueous NaOH/urea dissolution system. This innovative method enabled the uniform dispersion of jute-derived cellulose and its deposition onto ceramic supports under pressurized filtration, resulting in asymmetric membranes with thin (~4–5 μm), structurally robust cellulose skin layers. Characterization via FTIR, XRD, SEM, and contact angle measurements confirmed the transformation of cellulose I to cellulose II, resulting in enhanced membrane hydrophilicity, mechanical flexibility, and underwater oleophobicity. The membranes exhibited specialized wettability properties, including superhydrophilicity in air (WCA < 10°) and underwater superoleophobicity (UWOCA > 150°), which are crucial for superior antifouling performance. The optimized membrane (SRC-3-M) achieved an exceptional water permeation flux of approximately 487 L m-2 h-1 and consistently high oil rejection efficiencies, exceeding 98%, across various oil-in-water emulsions, including diesel, vegetable oil, and toluene. Long-term stability tests confirmed sustained performance over multiple filtration cycles, with flux recovery rates above 88–93% using only water rinsing. Dynamic underwater oil-droplet experiments further validated the membranes’ robust oil-repelling behavior, attributed to the stable hydration layer formed by surface hydroxyl groups and hierarchical surface roughness. A key innovation of this work is the development of a SRC-M architecture. Upon severe fouling, the cellulose barrier layer can be readily removed via ultrasonication and replaced with a freshly deposited layer, while retaining the original ceramic support. This modular regeneration strategy significantly extends membrane lifespan, reduces waste and operational costs, and circumvents the need for complete module replacement, a common drawback in conventional polymeric and ceramic membranes. DFT simulations provided atomic-level insight into the thermodynamics of cellulose dissolution and regeneration, providing fundamental support for the observed performance and guiding future optimization efforts. In conclusion, this research introduces a paradigm shift in membrane design by integrating bio-derived, biodegradable materials with durable inorganic support in a regenerable, modular format. The convergence of green feedstock, eco-friendly and straightforward fabrication, superior separation and antifouling performance, and robust regenerative capability positions this technology as a highly promising solution for sustainable industrial wastewater remediation. The demonstrated feasibility and scalability of this approach pave the way for its broader adoption in water treatment systems, contributing meaningfully to environmental protection and resource-efficient process engineering.

Methods

Materials

Jute sticks were sourced from Bangladesh. All chemicals, including toluene, ethanol, sodium hydroxide, stearic acid, nitric acid, sodium nitrite, sodium sulfite, sodium hypochlorite, and urea, were purchased from Merck and used without further purification. Commercial alumina ceramic disc membranes (47 mm diameter, 0.5 µm nominal pore size) were purchased from Lianyoung Highborn Technology Ltd. Deionized water was used in all experiments.

Cellulose extraction

Cellulose was extracted from the jute sticks using a chemical treatment process as demonstrated in Figure Legends.

Figure 1 After washing and cleaning with water, jute sticks were dried for 24 h at 60 °C. After being cleaned, the jute sticks were crushed, ground into a fine powder, and then sieved through a 1.18-mm screen. A toluene-ethanol mixture (2:1 v/v) was used to extract the jute stick powder in a hot extractor at 45 °C for approximately 6 h, with three successive elutions, to remove non-polar extractives. After air drying, the material was treated with 10% (w/v) sodium hydroxide for 90 min at 55 °C. After neutralizing the residue with acetic acid, it was washed with cold water and then dried for approximately 5 h at 80 ± 5 °C in a convection oven. Finally, the dried material was stored in a sealed container for further use. After that, 30 g of jute stick powder and 4 mg of sodium nitrite were added to 400 mL of 3.5% (v/v) nitric acid, and the mixture was stirred constantly for 2 h at 90 °C to remove the lignin. After washing with distilled water and filtering, a 2% (w/v) solution of sodium hydroxide and sodium sulfite was then added to the residue, which was allowed to digest for 1 h at 50 °C. After filtering, the precipitate was washed with distilled water and treated for 10 min at 90 °C with 3.5% (w/v) sodium hypochlorite. The residue was rinsed with distilled water and treated for 30 min at 80 °C with 17.5% (w/v) sodium hydroxide to remove β- and γ- cellulose. After filtering and thoroughly washing with distilled water, the resultant α-cellulose was again treated with 3.5% (w/v) sodium hypochlorite for five minutes at 100 °C to whiten it. The bleached α-cellulose was rinsed, filtered, and gently squeezed to remove water, producing small lumps. These lumps were then dried at 60 °C in a convection oven. Finally, a 40% yield of α-cellulose was obtained from jute sticks.

Cellulose solubilization and molding into a membrane

Cellulose dispersion was prepared by mixing NaOH, urea, and cellulose in equal proportions (1:1:1) with water. The mixture was stirred at 500 rpm at room temperature for 24 h to achieve a smooth and uniform dispersion. Once a fine dispersion was achieved, loadings of 0.62 mg, 1.25 mg, 2.5 mg, 5 mg, and 10 mg were applied to form a barrier layer on the ceramic membrane surface. The resulting membranes were labeled SRC-1-M (0.62 mg), SRC-2-M (1.25 mg), SRC-3-M (2.5 mg), SRC-4-M (5 mg), and SRC-5-M (10 mg), respectively. For membrane fabrication, the ceramic support was mounted in a dead-end filtration cell connected to an argon gas source, allowing for control of the applied pressure. The cellulose dispersion was first introduced at 1 bar, followed by compaction at 2 bars for 1 h to ensure uniform layer formation. After deposition, the membranes were thoroughly rinsed with double-distilled water to remove residual base and then stored in water until use. Since the ceramic support is an expensive component, the SRC-M membrane was placed in a sonication bath for 10 min to regenerate the cellulose skin layer. This treatment effectively removed the cellulose layer. The ceramic support was then reused by reapplying the cellulose dispersion using the same procedure to restore the membrane surface.

Characterization

The functional groups of the sample were determined using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) on a Nicolet 6700 (Thermo Scientific) instrument in the range of 400–4000 cm–1. The crystal structure of the sample was studied by X-ray diffraction (XRD, D8, Bruker, Germany). The data were recorded over a 2θ range of 3° to 80°. The morphology of the sample was analyzed using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, LYRA 3 Dual Beam, Tescan) with an In-Lens detector at an acceleration voltage of 20 kV. The water contact angle (WCA), oil contact angle (OCA), and underwater contact angle (CA) of 5.0 μL droplets were measured with a goniometer (DSA25, KRÜSS) at room temperature. The atomic force microscopy (AFM) Nanosurf easyScan 2 was used to measure the surface roughness of the membranes.

Emulsion preparation and separation

Surfactant-stabilized oil-in-water emulsion was synthesized by mixing water with oil (diesel, toluene, vegetable oil, respectively). A simulated oil-in-water emulsion was prepared by initially dissolving 0.5 g of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in 1 L of double-distilled water, with continuous magnetic stirring for 15 min. Once the complete dissolution of the surfactant had occurred, 1 g of diesel oil was added dropwise while the mixture was vigorously stirred. After 24 h of vigorous stirring, a milky-colored oil-in-water emulsion is formed. The resulting emulsion, with a 1000 ppm oil concentration, was white and stored overnight under stirring at room temperature to ensure complete stabilization of the oil droplets in the aqueous phase.

Separation performance evaluation

The separation performance of the cellulose membranes prepared was evaluated using a high-pressure dead-end filtration unit (HP4750, Sterlitech, USA). The unit consists of a stainless-steel dead-end filtration cell with an internal diameter of 51 mm and an effective membrane area of 14.6 cm2. Before the tests, all the membranes were pre-compacted in the cell at a pressure of 2 bar to densify the membrane structure and eliminate any initial compaction-induced flux differences.

A two-step regulated argon gas system was used to accurately adjust the transmembrane pressure during the filtration experiments. Separation studies were conducted at room temperature using 250 ppm and 500 ppm diesel-in-water emulsions as feed solutions. The permeate was collected over time to determine membrane flux and separation stability. The separation efficiency (η) was determined from feed and permeate turbidity measurements using a calibrated nephelometric turbidity unit (NTU) meter61,62. The flux (F) of emulsions through the membrane was determined from Eq. (4).

Where V (L) is the amount of permeate, A (m2) is the effective membrane area, and T (h) is the permeation time. A certain amount of the permeate was collected for each test, and the time of filtration was recorded. The separation efficiency (E) was determined by Eq. (5).

Where E represents separation efficiency, Cp is the turbidity in the permeate, and C0 is the oil concentration in the feed.

Flux and rejection data are presented as mean ± SD; the error bars denote the standard deviation across three independent experiments (n = 3) performed on separately prepared membrane samples under identical operating conditions. Fouling/cycling analyses, by contrast, were conducted as multiple consecutive runs on a single membrane to evaluate its fouling behavior.

Computational details

All density functional theory (DFT) calculations were executed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)63,64,65. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA), specifically the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional, was employed to describe exchange-correlation effects66. A plane-wave basis set with a cutoff energy of 500 eV was employed, ensuring a total energy convergence threshold of 1 × 10–6 eV. The Brillouin zone was sampled using a Γ-centered 2 × 1 × 1 k-point mesh, which is sufficient for the large real-space polymer cell used here, and all atomic positions were relaxed until the residual forces on each atom were below 0.01 eV Å–1. Spin-unpolarized calculations without spin–orbit coupling were employed, as the system contains only closed-shell atoms. To accurately capture non-covalent interactions, the Grimme DFT-D3 method was incorporated67. Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all three directions.

The computational model was strategically designed to accurately represent the single polycellulose strand identified as the active component post-treatment. We employed a 1D periodic model, with the chain extended along the a-axis, to mimic the material’s infinite polymeric nature. To simulate the isolated environment of a single strand and ensure adsorption calculations were free from artificial inter-chain interactions, large vacuum regions were applied in the two non-periodic directions (10 Å along b and 20 Å along c), effectively decoupling the periodic images. The 10 Å separation along b ensures a minimum intermolecular distance of ~10 Å between neighboring strands, while the larger 20 Å vacuum along c suppresses spurious electrostatic interactions and allows analysis of plane-averaged charge densities. The choice of the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional is a standard Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) offering a robust balance of efficiency and accuracy. Critically, the Grimme DFT-D3 dispersion correction was included because the adsorption of urea is driven primarily by non-covalent (van der Waals) forces, which are not adequately captured by the PBE functional alone. The conservative 500 eV plane-wave cutoff and strict 1 × 10–6 eV energy convergence threshold were adopted to guarantee high precision, ensuring the calculated energetic and structural results are transferable and reproducible.

The adsorption energy (Ead) of urea on polycellulose was calculated using Eq. (6).

Where Etot is the total energy of the combined urea-cellulose system, Ecellulose is the energy of the isolated polycellulose, and Eurea is the energy of the isolated urea molecule. The charge density difference (Δρ) was computed to analyze electron redistribution upon adsorption using Eq. (7).

Where ρtot, ρcellulose, and ρurea represent the charge densities of the combined system, isolated polycellulose, and isolated urea molecule, respectively. The Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of adsorption was calculated considering vibrational contributions using Eq. 8.

Here, ΔEad represents the adsorption energy, ΔEZPE is the zero-point energy difference, and ΔS denotes the entropy difference between the adsorbed state and the separated reactants. The kinetic barrier for urea adsorption was investigated using the climbing-image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method38. CI-NEB was performed with 4 intermediate images using the improved tangent scheme; images were relaxed until the maximum force dropped below 0.01 eV Å-1. All raw VASP outputs were subsequently processed and analyzed utilizing the VASPKIT code68.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kim, D., Livazovic, S., Falca, G. & Nunes, S. P. Oil-water separation using membranes manufactured from cellulose/ionic liquid solutions. ACS Sustain Chem. Eng. 7, 5649–5659 (2019).

Li, B., Qi, B., Guo, Z., Wang, D. & Jiao, T. Recent developments in the application of membrane separation technology and its challenges in oil-water separation: a review. Chemosphere 327, 138528 (2023).

Chen, M., Heijman, S. G. J., Luiten-Olieman, M. W. J. & Rietveld, L. C. Oil-in-water emulsion separation: fouling of alumina membranes with and without a silicon carbide deposition in constant flux filtration mode. Water Res. 216, 118267 (2022).

Wahid, F. et al. Designing of bacterial cellulose-based superhydrophilic/underwater superoleophobic membrane for oil/water separation. Carbohydr. Polym. 257, 117611 (2021).

Fakhru’l-Razi, A. et al. Review of technologies for oil and gas produced water treatment. J. Hazard Mater. 170, 530–551 (2009).

Zhu, Y. et al. Hierarchical porous PbO2 electrode for electro-degradation of various contaminants. Small Struct. 6, 2400389 (2025).

Zhu, Y., Wang, D., Jiang, L. & Jin, J. Recent progress in developing advanced membranes for emulsified oil/water separation. NPG Asia Mater. 6, e101 (2014).

Milić, J. K., Murić, A., Petrinić, I. & Simonič, M. Recent developments in membrane treatment of spent cutting-oils: a review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 7603–7616 (2013).

Dickhout, J. M. et al. Produced water treatment by membranes: a review from a colloidal perspective. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 487, 523–534 (2017).

Lin, T. et al. Recent advances in graphene-based membranes with nanochannels and nanopores. Small Struct. 6, 2400320 (2025).

Jia, S., Ji, D., Wang, L., Qin, X. & Ramakrishna, S. Metal–organic framework membranes: Advances, fabrication, and applications. Small Struct. 3, 2100222 (2022).

Baig, N., Arshad, Z. & Ali, S. A. Synthesis of a biomimetic zwitterionic pentapolymer to fabricate high-performance PVDF membranes for efficient separation of oil-in-water nano-emulsions. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–15 (2022).

Yang, W. J. et al. Recent progress in bio-based aerogel absorbents for oil/water separation. Cellulose 26, 6449–6476 (2019).

Xie, A. et al. Preparation of Janus membrane based on biomimetic polydopamine interface regulation and superhydrophobic attapulgite spraying for on-demand oil-water emulsion separation. J. Memb. Sci. 627, 119242 (2021).

Zuo, J. et al. A durable superwetting clusters-inlayed mesh with high efficiency and flux for emulsion separation. J. Hazard Mater. 403, 123620 (2021).

Ye, S. et al. Superhydrophobic and superelastic thermoplastic polyurethane/multiwalled carbon nanotubes porous monolith for durable oil/water separation. Compos. Commun. 21, 100378 (2020).

Xu, L. et al. Heterogeneous wettability membrane for efficient demulsification and separation of oil-in-water emulsions. Chem. Eng. J. 489, 151466 (2024).

Zhao, Y., Ji, X., Wu, L., Tian, J. & Zhang, C. Preparation of demulsifying functional membrane and its application in separation of emulsified oil. Sep Purif. Technol. 276, 119299 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. A multifunctional hierarchical porous SiO2/GO membrane for high efficiency oil/water separation and dye removal. Carbon N. Y 160, 88–97 (2020).

Cui, J., Xie, A., Yan, Z. & Yan, Y. Fabrication of crosslinking modified PVDF/GO membrane with acid, alkali and salt resistance for efficient oil-water emulsion separation. Sep Purif. Technol. 265, 118528 (2021).

Li, L. et al. Bio-inspired membrane with adaptable wettability for smart oil/water separation. J. Memb. Sci. 598, 117661 (2020).

Klemm, D. et al. Nanocelluloses: A new family of nature-based materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 5438–5466 (2011).

Heinze, T., El Seoud, O. A. & Koschella, A. Structure and properties of cellulose and its derivatives. 39–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73168-1_2 (2018).

Cheng, G., Liao, M., Zhao, D. & Zhou, J. Molecular understanding on the underwater oleophobicity of self-assembled monolayers: Zwitterionic versus nonionic. Langmuir 33, 1732–1741 (2017).

Chen, M. et al. State-of-the-art ceramic membranes for oily wastewater treatment: Modification and application. Membranes 2021, 11, (2021).

Chen, M., Rietveld, L. C. & Heijman, S. G. J. Evaluation of membrane fouling at constant flux and constant transmembrane pressure conditions: Implications for membrane modification. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 13, 117823 (2025).

Chen, M., Heijman, S. G. J. & Rietveld, L. C. Ceramic membrane filtration for oily wastewater treatment: Basics, membrane fouling and fouling control. Desalination 583, 117727 (2024).

Szabó, L., Milotskyi, R., Sharma, G. & Takahashi, K. Cellulose processing in ionic liquids from a materials science perspective: turning a versatile biopolymer into the cornerstone of our sustainable future. Green. Chem. 25, 5338–5389 (2023).

Piltonen, P. et al. Green and efficient method for preparing all-cellulose composites with NaOH/urea solvent. Compos Sci. Technol. 135, 153–158 (2016).

Padzil, F. N. M. et al. Effect of acid hydrolysis on regenerated kenaf core membrane produced using aqueous alkaline-urea systems. Carbohydr. Polym. 124, 164–171 (2015).

Cai, J. & Zhang, L. Rapid dissolution of cellulose in LiOH/urea and NaOH/urea aqueous solutions. Macromol. Biosci. 5, 539–548 (2005).

Shah, S. S. et al. Present status and future prospects of jute in nanotechnology: A review. Chem. Rec. 21, 1631–1665 (2021).

Aziz, A., Shah, S. S. & Kashem, A. Preparation and utilization of jute-derived carbon: A short review. Chem. Rec. 20, 1074–1098 (2020).

Ahmed, M. S. et al. Jute stick-derived cellulose-based hydrogel: Synthesis, characterization, and methylene blue removal from aqueous solution. ACS Omega 8, 47856–47873 (2023).

Peng, J. et al. Influence and mechanism of NaOH concentration on the dissolution of cellulose and extraction of CNF in alkaline solvents at 15 °C. Carbohydr. Polym. 353, 123265 (2025).

Zhang, L., Ruan, D. & Gao, S. Dissolution and regeneration of cellulose in NaOH/Thiourea aqueous solution. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 40, 1521–1529 (2002).

Ai, S., Huang, Z., Yu, W. & Huang, C. Efficient dissolution of cellulose in slow-cooling alkaline systems and interacting modes between alkali and urea at the molecular level. Carbohydr. Res. 536, 109054 (2024).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Ylivainio, K. J., Sufyan, A. & Andreas Larsson, J. A quantitative relationship between electron localization function and the strength of physical binding. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 37, 205502 (2025).

Shimpi, M. T., Sajjad, M., Öberg, S. & Larsson, J. A. Physical binding energies using the electron localization function in 4-hydroxyphenylboronic acid co-crystals with aza donors. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 35, 505901 (2023).

Lu, Q. et al. Preparation of alumina crystal flower powders by molten salt method. Ceram. Int 51, 43613–43625 (2025).

Mohammed, A. A., Khodair, Z. T. & Khadom, A. A. Preparation and investigation of the structural properties of α-Al2O3 nanoparticles using the sol-gel method. Chem. Data Collect. 29, 100531 (2020).

Yu, L. et al. Cellulose nanofibrils generated from jute fibers with tunable polymorphs and crystallinity. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2, 6402–6411 (2014).

Grzybek, P., Dudek, G. & van der Bruggen, B. Cellulose-based films and membranes: A comprehensive review on preparation and applications. Chem. Eng. J. 495, 153500 (2024).

Che, W., Zhou, L., Zhou, Q., Xie, Y. & Wang, Y. Flexible Janus wood membrane with asymmetric wettability for high-efficient switchable oil/water emulsion separation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 629, 719–727 (2023).

Zhang, R., Sun, Y., Guo, Z. & Liu, W. Janus membranes with asymmetric wettability applied in oil/water emulsion separations. Adv. Sustain Syst. 5, 2000253 (2021).

Khalil, H. et al. Asymmetrical ultrafiltration membranes based on polylactic acid for the removal of organic substances from wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 45, 102510 (2022).

Wei, Y., Qi, H., Gong, X. & Zhao, S. Specially wettable membranes for oil–water separation. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 5, 1800576 (2018).

Zhang, H., Wang, F. & Guo, Z. The antifouling mechanism and application of bio-inspired superwetting surfaces with effective antifouling performance. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 325, 103097 (2024).

Zhou, D. L. et al. Fabrication of superhydrophilic and underwater superoleophobic membranes for fast and effective oil/water separation with excellent durability. J. Memb. Sci. 620, 118898 (2021).

Zheng, S. et al. Performance investigation of hydrophilic regenerated cellulose ultrafiltration membranes with excellent anti-fouling property via hydrolysis technology. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 109041 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Effects of hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity of membrane on membrane fouling in a submerged membrane bioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. 175, 59–67 (2015).

Hu, L. et al. A novel Janus composite membrane and its enhanced antifouling strategy for emulsion purification. J. Memb. Sci. 708, 123061 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Eco-friendly self-crosslinking cellulose membrane with high mechanical properties from renewable resources for oil/water emulsion separation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 105857 (2021).

Zheng, Y., Sun, F., Zeng, P. & Su, Y. Recent development of special wettability filtration membrane for selective oil/water separation applications: A review. Prog. Org. Coat. 198, 108885 (2025).

Lv, Y., Li, Q., Hou, Y., Wang, B. & Zhang, T. Facile preparation of an asymmetric wettability janus cellulose membrane for switchable emulsions’ separation and antibacterial property. ACS Sustain Chem. Eng. 7, 15002–15011 (2019).

Chen, S., Li, L., Zhao, C. & Zheng, J. Surface hydration: Principles and applications toward low-fouling/nonfouling biomaterials. Polym. (Guildf.) 51, 5283–5293 (2010).

Nunes, S. P. Can fouling in membranes be ever defeated?. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 28, 90–95 (2020).

Asif, M. B. & Zhang, Z. Ceramic membrane technology for water and wastewater treatment: A critical review of performance, full-scale applications, membrane fouling and prospects. Chem. Eng. J. 418, 129481 (2021).

Khan, R., Baig, N., Yaseen, Z. M., Younas, H. & Al-Suwaiyan, M. Self-assembled vanadium carbide MXene-modified ceramic membranes with high permeability for efficient oil-in-water emulsion separation. Langmuir 41, 23568–23581 (2025).

Moulai-Mostefa, N., Frappart, M., Akoum, O., Ding, L. H. & Jaffrin, M. Y. Separation of water from metal working emulsions by ultrafiltration using vibratory membranes. J. Hazard Mater. 177, 978–982 (2010).

Tomczak, W. & Gryta, M. Application of ultrafiltration ceramic membrane for separation of oily wastewater generated by maritime transportation. Sep Purif. Technol. 261, 118259 (2021).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Wang, V., Xu, N., Liu, J. C., Tang, G. & Geng, W. T. VASPKIT: a user-friendly interface facilitating high-throughput computing and analysis using VASP code. Comput. Phys. Commun. 267, 108033 (2021).

Zhu, X., Tu, W., Wee, K. H. & Bai, R. Effective and low fouling oil/water separation by a novel hollow fiber membrane with both hydrophilic and oleophobic surface properties. J. Memb. Sci. 466, 36–44 (2014).

Chakrabarty, B., Ghoshal, A. K. & Purkait, M. K. Ultrafiltration of stable oil-in-water emulsion by polysulfone membrane. J. Memb. Sci. 325, 427–437 (2008).

Liu, Z. et al. A mussel inspired highly stable graphene oxide membrane for efficient oil-in-water emulsions separation. Sep Purif. Technol. 199, 37–46 (2018).

Mansha, M., Salhi, B., Ali, S., Khan, S. A. & Baig, N. Novel procaine-based gemini zwitterion incorporated PVDF membranes for efficient treatment of oily wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 107935 (2022).

Wu, C. et al. Treatment of oily water by a poly(vinyl alcohol) ultrafiltration membrane. Desalination 225, 312–321 (2008).

Ahmad, A. L., Majid, M. A. & Ooi, B. S. Functionalized PSf/SiO2 nanocomposite membrane for oil-in-water emulsion separation. Desalination 268, 266–269 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support provided by the IRCMWS at KFUPM and all the universities involved in this work. The authors would like to acknowledge support from INMW2422. We thank the Knut och Alice Wallenberg Foundation, Sweden, Kempe-stiftelserna, Sweden, Wallenberg Initiative Materials Science (WISE), and Swedish Research Council (grant no. 2023-03894) for financial support. The computations were enabled by resources provided by the National Academic Infrastructure for Supercomputing in Sweden (NAISS) at HPC2N and NSC, partially funded by the Swedish Research Council through grant agreement no. 2022-06725.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lulea University of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.B.: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing-original draft, Supervision. T.A.: Investigation, Writing-original draft. A.S.: Data curation, Writing-original draft. M.B.A.: Visualization, Writing-review & editing. K.A.: Data curation & Investigation. B.A.: Data curation & Investigation. M.S.A.: Data curation & Investigation. M.M.: Data curation & Investigation. A.H.: Methodology, Writing-review & editing. S.S.S.: Methodology, Writing-review & editing. J.A.L.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing-review & editing, M.A.A.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baig, N., Ahmad, T., Sufyan, A. et al. Skin-replaceable antifouling cellulose ceramic membranes from jute agro-waste for sustainable and efficient oily wastewater treatment. npj Clean Water 9, 8 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00538-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00538-3