Abstract

Azo is a synthetic organic dye that has attracted considerable attention because of its recalcitrance to degradation and toxicity. An upgraded ozonation process must be developed that integrates decolorization, mineralization, and toxicity reduction to manage the residual azo dye in the effluent from the dyeing industry and reduce its associated aquatic environmental risks. In this study, an ozonation system using Meretrix lusoria (ML) shell-waste-derived biomass (ML800) that uses simple calcination was developed. The ML800/O3 system almost completely decolorized ( > 99.0%) and highly mineralized (53.6 ± 1.7%) Congo red (CR) during (CR = 100 mg∙L–1, ML800 = 0.5 g ∙ L–1), surpassing the performance of the other tested systems (single ozonation and single ML800). Moreover, the ML800/O3 system reduced the acute toxicity of CR to the bacterium Aliivibrio fischeri, whereas single ozonation showed temporarily increased the toxicity of CR. The FE-SEM/EDS, FTIR, and XRD analyses verified that Ca(OH)2 was the main calcium species in ML800, which catalyzed the decomposition of O3 into highly reactive •OH. The system was successfully applied to various azo dyes and was robust with water matrix constituents. These findings highlight the potential of marine shell waste for use as a sustainable and ecofriendly additive for ozonation, increasing azo dye removal from wastewater in practical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Synthetic organic dyes are widely used in various industrial areas such as textiles, medicine, and cosmetics, with an annual global production of over 700,000 tons1. The processing and application of dyestuffs require large amounts of water2. For example, approximately 35–60 g of dye and 70–150 L of fresh water are required to colorize 1 kg of cotton, and approximately 20–30% of the input dye is discharged in wastewater3. Dyes must be properly handled because the generation of wastewater containing residual dye has caused serious concern4. Azo dyes are prominent among the synthetic dye compounds, accounting for 70% of the total dye used5. Azo dyes contain distinctive azo bonds (N = N) coupled with at least one or two aromatic molecular systems6. Azo dyes are resistant to degradation and are hazardous to organisms, being carcinogenic, teratogenic, and mutagenic, because of their of azo bonds7,8. Therefore, azo dyes frequently remain in the effluents from conventional treatment processes, threatening the aquatic environment and human health9.

Advanced oxidative processes are widely applied to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and effectively remediate recalcitrant micropollutants10,11. Ozonation is one of these processes, which is used for treating dye wastewater and decolorizing azo dye decolorization12. The ozone (O3, E° = 2.07 V) in the ozonation system directly (Eq. 1) and indirectly (Eqs. 2 and 3) reacts with the azo dye via attacking the color-associated conjugated double bonds such as the azo or-C = C-bonds7.

These reaction mechanisms enable wastewater to be rapidly decolorized by destroying the azo chromophore13. Nevertheless, throughout the single ozonation process, decolorization by-products, such as aromatic amines, may be produced instead of achieving complete mineralization5. These intermediates can increase the effluent toxicity to above that of the original influent. Souza et al. and Dias et al. reported an increase in toxicity during single ozonation of Remazol Black 5 and Reactive Red 239 solutions, respectively6,14. For optimal azo dye wastewater treatment, it is imperative to explore a multifaceted approach that encompasses the color reductive characteristics and the total mineralization capacity.

Various combined ozonation technologies (e.g., UV, oxidants, and catalysts) have been investigated to address the limitations of the single ozonation method in treating dyes in wastewater15,16,17. These integrated systems facilitate O3 decomposition and the formation of hydroxyl radicals (•OH, E° = 2.80 V), which are less selective and more oxidative than O318,19. Consequently, further mineralization is facilitated, in contrast to the single ozonation process. However, combined ozonation systems often require additional chemical or energy inputs, which pose challenges for practical applications due to the (1) high costs associated with reagent or catalyst preparation as well as energy consumption and (2) risk for secondary contamination, particularly when catalysts are conjugated with transition metals20,21. Development of alternative strategies for advanced ozonation systems is required to achieve both mineralization efficiency and operational feasibility.

More than 10 million tons of marine shell waste are produced globally each year; proper management and disposal have become issues22. A large portion of this waste is discarded in landfills, causing environmental problems by occupying land, producing leachate, and generating odor23. Shell waste has been valorized as a low-cost precursor for bio functional materials with appropriate processing24. Biological shell-based materials have primarily been used as adsorbents for treating wastewater treatment because of their high porosity and minimal impact on the aquatic matrix25,26. These biomaterials produce calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) upon calcination owing to their high calcium carbonate (CaCO3) content, which ionizes into calcium (Ca2+) and hydroxide ions (OH–), and induces the basic catalysis of O3 (Eqs. 4 and 5)27,28.

Shell waste therefore shows considerable potential to enhance the mineralization performance of ozonation systems and to be used as a substitute for the chemical inputs, addressing some of the issues with these systems. Using shell waste in these systems could contribute to environmental sustainability through effectively using a product that would otherwise be waste. However, marine shell waste has not yet been incorporated into ozonation systems.

We used shell-waste-derived materials in the ozonation process to treat azo dye wastewater with the aim of developing a method that performs decolorization, mineralization, and detoxification. Meretrix lusoria (ML) shells were used to prepare naturally derived additives. Congo red (CR) is an acidic monoazo dye that was selected as the target pollutant. Total organic carbon (TOC) removal is a key indicator of azo dye mineralization. The acute toxicity of the remaining CR was also analyzed via detecting the inhibition of the bioluminescence of the bacteria Aliivibrio fischeri. This study offers an effective strategy to reuse shell waste to advance conventional ozonation processes.

Results

CR decolorization, mineralization, and detoxification by ML800/O3 system

The CR degradation efficiency was evaluated by measuring the decolorization and mineralization in different systems (Fig. 1a, b). All systems rapidly decolorized the CR (kCR,ML800 = 0.002 min–1, kCR,O3 = 0.056 min–1, kCR,ML800/O3 = 0.134 min–1), with the reaction mostly completed within 30 min (Fig. 1a). The ozonation systems (single ozonation and ML800/O3) almost completely decolorized the dye ( > 99.0%) after 120 min, whereas the single ML800 system partially decolorized the CR (62.6 ± 1.6%). This finding indicated that the generated O3 effectively contributed to decolorizing the CR by eliminating the chromophore, which is responsible for the visible-light absorbance of CR29. In mineralization, the TOC removal efficiency of the ML800/O3 system was higher (53.6 ± 1.7%) than that of single ozonation (11.2 ± 3.3%) or single ML800 (31.7 ± 5.8%) after 120 min (Fig. 1b). The differences in TOC removal efficiency indicated that ML800 influenced ROS generation, ultimately increasing mineralization30. The TOC removal efficiency of the single ML800 system was higher than that of the single ozonation system (Fig. 1b), in contrast to the decolorization results. This occurred because the Ca2+ generated from ML800 (Supplementary Fig. 1a) directly removed CR molecules via producing insoluble calcium sulfonate complexes31. However, the CR removed via chemical coagulation was limited, regardless of further increases in the Ca2+ concentration, as confirmed by the control experiments (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

a Decolorization and b mineralization of CR in each system. c Variation in Acute toxicity during CR degradation in single ozonation system and ML800/O3 system. d Proposed degradation pathway of CR during ozonation. Experimental conditions: CR = 100 (a, b) and 500 (c) mg∙L–1, ML800 = 0.5 g ∙ L–1, O3 dose = 44.0 mg∙L–1, reaction time = 120 min.

The hazardous intermediates can occur during the partial mineralization in ozonation systems, resulting in effluent toxicity6,14. The acute toxicity of the initial CR solution after ozonation was analyzed (Fig. 1c). The toxicity units (TU) value positively correlated with acute toxicity, with a higher TU indicating higher sample toxicity. For The TU for single ozonation markedly increased at a reaction time of 5 min, whereas the TU removal of the ML800/O3 system was similar at 5 min and 10 min. These results suggested that ML800 rapidly reduced the solution toxicity caused by the intermediates generated from the single ozonation of CR29. Nevertheless, ozonation alone and ML800/O3 eventually reduced the TU in the initial CR solution over 10 min. For further elucidation, byproducts were analyzed by liquid chromatography coupled to quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (LC-MS/QTOF) (Fig. 1d). After 5 min of treatment, CR (651 m/z) and 4-amino-1-naphthalenesulfonic acid (224 m/z) were detected as the parent compound and its reduction product, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2a-c)29,32. Benzidine (185 m/z) is one of the well-recognized carcinogenic byproducts which is widely used as base material for azo dye synthesis, including CR33,34. In the ML800/O3 system, benzidine was markedly suppressed compared to the single ozonation system (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e), demonstrating the efficacy of ML800 in mitigating the formation of hazardous aromatic amine intermediates during ozonation.

Overall, the ML800/O3 system outperformed the other considered systems in CR decolorization and mineralization. The ML800/O3 system reduced the toxicity more than the single ozonation system, underscoring its potential for practical applications.

ML shell waste valorized as Ca(OH)2 source via calcination

The field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) images displayed the morphological features of the original ML powder and the synthesized ML800 (Fig. 2a, b). Thermal treatment altered the smooth ML surface into crystalline patterns of ML800. Under the applied calcination condition, however, no significant increase in porosity was observed while the BET surface area slightly decreased from 1.0 m2 ∙ g–1 (ML) to 0.7 m2 ∙ g–1 (ML800) (Supplementary Fig. 3). The surface chemical composition was analyzed using energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) coupled with FE-SEM (Table 1). Marine seashell waste generally contains calcium, mostly in the form of CaCO335. The original ML powder had a high calcium content, accounting for 88.4% of the total weight percentage. The proportion of calcium in ML800 increased to 96.9% after calcination, whereas the carbon content decreased from 10.7% to 2.4%. This transition was ascribed to the generation of noncarbon functional groups, especially Ca(OH)2 under 800 °C36.

Attenuated total reflectance (ATR)-Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was used to further study the functional groups (Fig. 2c). ML800 showed small C–O stretching bands at approximately 712 cm–1 and 872 cm–1, indicating a decrease in CO32– content36. The broad peak near 1,420–1,490 cm–1 indicates the presence of amorphous CaCO3, the content of which was also substantially lower in ML800 than in the other system37. An O-H stretching band emerged at approximately 3645 cm–1 in ML800, indicating the presence of Ca(OH)238. Moreover, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted to elucidate the conversion of calcium species during calcination (Fig. 2d). The primary phase of original ML powder was identified as aragonite (CaCO3, JCPDS No. 01-075-9986), whereas the ML800 exhibited prominent peaks corresponding to portlandite (Ca(OH)2, JCPDS No. 01-075-9986) along with additional calcite (CaCO3, JCPDS No. 01-075-9986)39,40. These results imply the successful conversion of calcium species during calcination, where CaCO3 decomposes into CaO and CO2 following Ca(OH)2 formation (Eqs. 6 and 9).

Ca(OH)2 groups enable the two roles of ML800: (1) sustaining an alkaline pH above 8.0 (Supplementary Fig. 7) promoting •OH production through O3 catalysis (Eqs. 4 and 5) and (2) releasing Ca2+ (Supplementary Fig. 1a) to trigger chemical coagulation.

ML800/O3 system promoted •OH generation

To confirm •OH generation in ozonation systems, scavenger tests were conducted by adding 10 mM tert-butyl alcohol (TBA), a well-known •OH scavenger (k = 6.0×108 M–1 ∙ s–1)41. The ozonation systems exhibited a slight decrease in CR decolorization performance upon TBA addition, with the ML800/O3 system showing a pronounced inhibition (Supplementary Fig. 4). However, it should be noted that TBA can cause gas bubbles during ozonation, possible enhancement of O3 diffusion and underestimation of •OH effects42. For more precise detection, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) analysis was performed (Fig. 3a). The ML800/O3 system showed the DMPO-•OH signal, while single ozonation exhibited only a weak DMPOX peak, indicative of dissolved O343,44. These results suggest that ML800 effectively decomposed O3 and converted it into •OH.

Following the identification of reactive species, we conducted a semiquantitative assessment to match •OH production between the ozonation systems using the selected chemical probes: benzoic acid (BA) and 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (HBA) (Fig. 3b, c). BA is inert to O3 and selectively reacts with •OH (k = 4.2×109 M–1 ∙ s–1)10, where HBA is produced by the addition of •OH to BA45. ML800 did not affect the BA degradation or HBA generation during the probe tests (Supplementary Fig. 5). BA degradation corresponded to HBA generation, indicating •OH was involved in the indirect ozonation pathway. The ML800/O3 system degraded more BA (kBA,ML800/O3 = 0.007 min–1) than single ozonation (kBA,O3 = 0.019 min–1) and had a three times higher rate constant. In addition, ML800/O3 generated more HBA than the single ozonation system. These results demonstrate that the ML800/O3 system generates more •OH compared with the single ozonation system due to O3 catalysis of ML800. To elucidate the role of ML800, a leaching test was conducted by separating the heterogeneous phase of ML800 from biphasic ML800/O3 system (Supplementary Fig. 6). Comparable performance was observed in the leachate test compared to the ML800/O3 system (Supplementary Fig. 6a-c), indicating the predominant contribution of the homogeneous phase46. Although slight decreases in mineralization and •OH generation were detected in the leaching tests. These might be due to the absence of residual ML800, thus result in more rapid neutralization of the solution pH compared to the ML800/O3 test (Supplementary Fig. 6d).

The mechanistic scheme of the ML800/O3 system has been illustrated in Fig. 3d. Upon dissolution of Ca(OH)2-based ML800, alkaline environment established, which catalyze the decomposition of O3 into •OH (Indirect pathway). Although O3 directly reacts with CR (direct pathway), •OH enhances the degradation of CR, improving decolorization, mineralization and detoxification efficiencies. Ca2+ ions also released, which binds with CR and facilitating its removal (chemical precipitation).

Effect of ML800 dosage and initial CR concentration on ML800/O3 system

We examined the effects of the operational factors on the ML800/O3 system by conducting various experiments varying the ML800 dose and initial CR concentration. The effects of the individual parameters were concurrently evaluated with the reaction time because of the direct relationship between reaction time and degradation efficiency. The ML800 dose ranged from 0.1 to 1 g ∙ L–1 (Fig. 4a, b). Almost complete CR decolorization was achieved in 120 min under most conditions, although slightly less CR was decolorized in 30 min using 1 g ∙ L–1 ML800; the agglomeration at excessive ML800 doses may have increased the turbidity47. Nevertheless, mineralization efficiency prominently increased with the ML800 dosage, achieving the highest value (72.0 ± 1.8%) at 1 g ∙ L–1. O3 decomposed into •OH for longer durations at higher ML800 doses when the solution pH was alkaline for longer owing to ML800 (Supplementary Fig. 7).

The effect of the initial CR concentration on the CR decolorization was also investigated (Fig. 4c, d). Although CR decolorization was delayed with increasing CR concentration, ML800/O3 completely decolorized the CR after 120 min. The mineralization was similar among the conditions, with the highest value obtained with 50 mg∙L–1 (57.9% ± 7.1%). In contrast, the single ozonation system had lower CR decolorization rate and mineralization efficiency for all concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 8). These results demonstrate the high •OH availability in the ML800/O3 system, which efficiently decolorizes a range of CR concentrations.

ML800/O3 applicability to various azo dyes

We evaluated the feasibility of using the ML800/O3 system for treating azo-dye-contaminated wastewater by conducting degradation experiments with various azo dye compounds: TZ, methyl orange (MO), and Eriochrome black T (EBT) (Fig. 5a). The properties and ATR-FT-IR spectra of each dye are detailed in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 9, respectively. The ML800/O3 system robustly and consistently decolorized all tested dyes, completely removing color within 30 min (Fig. 5b). The mineralization efficiency differed among the dyes, being highest to lowest for TZ (67.1% ± 4.5%), EBT (56.8 ± 0.6%), MO (53.8 ± 0.6%), and CR (53.6 ± 1.7%) (Fig. 5c). The ATR-FTIR spectra (Supplementary Fig. 9) show that the dyes are characterized by azo bonds and auxochromes, such as hydroxyl (-OH), sulfonate (–SO3–), and carboxylate (–COO–)48. These negatively charged groups provide binding sites for Ca2+, which is bound via electrostatic interactions49. TZ contained the most abundant negatively charged groups, particularly sulfonate and carboxylate, suggesting high coagulation accessibility by Ca2+. This accessibility contributed to the high TZ mineralization efficiency of the single ML800 system (Supplementary Fig. 10b). In contrast, MO had the fewest Ca2+ binding sites; as such, the decolorization and mineralization efficiencies of the single ML800 system were the lowest (Supplementary Fig. 10). O3 and •OH behave as strong electrophiles, oxidizing the aromatic fragments of the dyes during treatment50,51. The functional groups accordingly dictate the reactivity of the dyes with O3 and the extent of mineralization. EBT adhered to the strong electron-donating hydroxyl groups and showed a high affinity for O3; therefore, EBT was more readily mineralized than CR and MO.

Effect of water matrix constituents coexisting ions and natural organic matter (NOM)

The effects of cations (Ca2+ and Mg2+) and anions (Cl–, NO3–, and SO42–) on the dye removal performance of the ML800/O3 system were investigated (Fig. 6a, b). Most inorganic ions negligibly inhibited decolorization at 25 mM, and the final decolorization rate was comparable to that of the control. However, the decolorization rate and the mineralization efficiency (37.7 ± 7.7%) were lower in the presence of Mg2+ than in the control group (Fig. 6a, b). Mg2+ has the smallest ionic radius (0.65 Å–1) among the cations (Ca2+: 1.14 Å–1, Na+: 1.02 Å–1), leading to strong electrostatic attractions with OH– and triggering precipitation into Mg(OH)252. Thus, the amount of available OH– may be lower in the presence of Mg2+, which decreases the O3 decomposition rate. This hypothesis is corroborated by the initially reduced pH, a behavior that differed from that in the presence of other ions (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Effects of coexisting ions on a decolorization and b mineralization of CR. Effects of NOMs on c decolorization and d mineralization of CR. Experimental conditions: CR = 100 mg∙L-1, ion concentration = 25 mM, NOM concentration = 5 mg C∙L-1, ML800 concentration = 0.5 g∙L-1, O3 dose = 44.0 mg∙L-1, and reaction time = 120 min.

The effects of NOMs (Sigma Aldrich humic acid (SAHA), Suwanee River humic acid (SRHA), Aladdin humic acid (AHA), and fulvic acid (FA); 5 mg C ∙ L–1) on the dye removal performance of the proposed system were assessed (Fig. 6c, d). The NOMs influenced mineralization efficiency as follows: SRHA (51.8 ± 5.0%) > SAHA (49.3 ± 0.6%) > AHA (49.2 ± 6.4%) > SAHA (41.8% ± 10.4%). These findings can be ascribed to the scavenging effect of NOMs (k = 104 mg C–1 ∙ s–1) given the role of •OH on mineralization performance, in agreement with the findings of oxidative process studies53. Here, FA strongly reduced mineralization efficiency owing to its high •OH affinity. This high •OH is due to the structural characteristics of its various electron-rich functional groups and its relatively small molecular size, resulting in lows steric hindrance54.

Discussion

Methods for effectively treating azo dye-containing wastewater must be developed meet the requirements of the color industry while protecting water quality. We removed aqueous azo dyes using an ozonation system that uses shell-waste-derived biomaterial. The ML800/O3 system decolorized the most CR ( > 99.0%) and removed the most TOC (53.6 ± 1.7%) at an ML800 dose of 0.5 g ∙ L–1 and initial CR concentration 100 mg∙L–1), surpassing the values achieved with the single ozonation system. ML800 reduced the toxicity of the solutions formed during ozonation because of the calcium species contained in ML800 that catalyzed the decomposition of O3 into highly oxidative and nonselective •OH. System also demonstrated robustness against water matrix constituents and applicability to other azo dye compounds.

We developed a strategy that simultaneously increases the efficacy of conventional ozonation processes and valorizes marine waste for treating dye-contaminated wastewater. Prior approaches mainly rely on transition-metal-based additives, which pose the risk of secondary contamination. As such, our proposed strategy is a more sustainable and eco-friendly alternative. The dye removal efficiency of the proposed method is higher, and the strategy enables the reuse of marine waste, contributing to the circular economy and bridging the gap between academic research and practical applications.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

CR (C32H22N6Na2O6S2), methyl orange (C14H14N3NaO3S), eriochrome black T (C20H12N3O7SNa), potassium iodide (KI, 99.0%), sodium thiosulfate pentahydrate (Na2S2O3 ∙ 5H2O, 98.5%), sodium hydrogen carbonate (NaHCO3, 99.0%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98.0%), starch (C12H22O11, EP grade), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 95.0%), tert-butyl alcohol (TBA, C4H10O, ≥99.0%), and acetonitrile (ACN, C2H3N, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade) were obtained from Samchun Pure Chemical Co. Ltd. The TZ (C16H9N4Na3O9S2) was purchased from Daejung Chemicals Co., Ltd. Methanol (MeOH, CH3OH, HPLC-grade), SAHA, formic acid (CH2O2, 99.5%), BA (C7H6O2, 99.5%), and 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-Oxide (DMPO, C6H11NO ≥ 98.0%) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich Co., Ltd. HBA (C7H6O3, 98.0%) was obtained from Junsei Chemical Co., Ltd. AHA and FA were purchased from Aladdin Industrial Co. Ltd. SRHA was obtained from International Humic Substances Society. Deionized water (DI, 18.2 MΩ∙cm–1) was generated by a Direct-Q UV system and used for preparing all solutions.

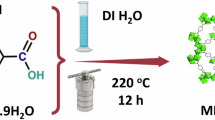

Producing and characterizing ML800

ML800 was prepared via calcination using a tube furnace (STF-1206, U1TECH) following steps40. First, ML shell waste obtained from a local restaurant in Anseong, Korea, was washed with DI water to eliminate residual impurities. Second, the washed ML shells were dried for 24 h at 110 °C in vacuum oven and finely ground into powder. Third, the ML powder was passed through a 50-mesh sieve to ensure a homogeneous size. Finally, the powders were inserted into tube furnace and calcinated for 4 h at 800 °C under a nitrogen gas purged atmosphere. The elemental composition was analyzed using FE-SEM (S-4700, Hitachi) coupled with an EDS. The functional groups were analyzed using ATR-FTIR (VERTEX 70, Bruker Optics Inc.) from 400 to 4,000 cm–1 with a spectral resolution of 0.2 cm–1.

Experimental procedures

A batch-scale experiment was conducted in a glass reactor with a 100 mL working volume containing the azo dye solution (Supplementary Fig. 12). The ozone generator (10 W, ATWFS) was equipped with a porous gas diffuser and introduced O3 gas to the bottom of the reactor for 120 min. The manufacturer-provided value of O3 input and air flow rate was 400 mg∙h–1 and 3.5 L∙min–1, respectively. The magnetic stirrer was agitated at 300 rpm to ensure a homogeneous O3 distribution in the solution. The reaction was maintained for a specified time, and aliquots were periodically collected at predefined intervals to quantify the azo dye concentration. The samples were filtered through 0.22 µm PTFE syringe membrane filter (Hyundai Micro) before analysis. The decolorization efficiency (C/C0) was evaluated as the ratio of the CR concentration at a given time (C) to the initial concentration (C0). The final mineralization efficiency (%) was determined as follows (Eq. 8):

where TOCi and TOCf are the initial and final (after 120 min) TOC content of the sample, respectively. The probe test involved adding 1 mM of BA to the reaction mixture. The leaching test was performed using ML800 leachate prepared by stirring ML800 in DI for 0.5 h and then filtering to remove residual solids. All trials were conducted in triplicate (n = 3), and error bars in the figures indicate the standard deviation of the replicates.

Determining O3 dose via iodometric titration

Iodometric titration was used to determine the O3 concentration dispersed in the solution19. A 2% KI solution was prepared by dissolving KI in a 0.01 M phosphate buffer solution (pH 7). O3 was introduced into 100 mL of the KI solution. The reaction proceeded for 0.5 h, after which the solution pH was reduced to 2 using 0.5 M sulfuric acid. Starch solution (0.5 mL; 1%) was added as an indicator and titrated with a 0.005 N Na2S2O3 solution. The O3 input/ouput (mg∙h–1) were calculated as follows (Eq. 9):

where N is the normality of Na2S2O3 (0.005 N), V is the volume of titrant consumed (mL), and t is the reaction time (0.5 h). Consequently, the concentration of the input and output O3 were 2.4 and 0.2 mg∙h–1, respectively. Based on these measurements, the utilized O3 dose has been calculated as 44.0 mg∙L–1 for the total reaction time of 2 h.

Analytical method

The absorbance of the samples was measured using a UV–vis spectrometer (OPTIZEN POP-V, KLAB). The concentration of the azo dye was determined using a calibration curve, which was plotted for a specified wavelength (Supplementary Table 1). The Ca2+ concentration dissolved in the sample was determined using a specialized photometer (HI97752, HANNA Instruments). Bioluminescence inhibition was evaluated using a luminometer (Biolight Toxy, Aqua Science) based on the bacterium Aliivibrio fischeri following the ISO 11348-3 protocol (ISO 11348-3, 1998)55. While CR degradation performance has evaluated under practical level (100 mg∙L–1)56,57,58, toxicity test has employed in higher initial CR concentration (500 mg∙L–1) to improve the detectability of solution toxicity. The pH of all samples was adjusted to 7.5 by using 0.2 M HNO3 before the test, in which the bacteria were exposed for 0.5 h. EC20 was defined as the sample percentage (%v/v) that inhibited 20% of the bioluminescence and was determined by regression analysis of dose-response curve (Supplementary Fig. 13). TU was calculated as TU = 100/EC2059. Detailed EC20 and TU values for each sample were tabulated in Supplementary Table 2. Degradation byproducts were analyzed by LC-MS/QTOF (Xevo G2-XS, Waters) with 1.7 µm C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, Waters) under the following conditions: the mobile phase was DI:MeOH = 30:70, the MS was operated in ESI mode positive with a mass range of 50-1200 Da, capillary voltage of 2.5 kV, cone voltage of 30 V, source temperature of 150 °C, and collison energy of 15-45 eV. The BA and HBA concentrations were quantified via HPLC (YL 9100, YOUNGIN Chromass) with a 5 µm C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm, SunFire) and a UV–vis detector (YL9120) under the following conditions: The mobile phase was ACN:0.1% formic acid = 45:55 (BA) and DI:ACN = 50:50 (HBA). The detection wavelengths were 240 nm (BA) and 255 nm (HBA). The TOC content was determined using a TOC-L analyzer (Shimadzu) and an ASI-L autosampler. The TOC values for the 100 mg∙L–1 NOM samples were 27.22 mg C ∙ L–1 (SAHA), 47.52 mg C ∙ L–1 (SRHA), 44.52 mg C ∙ L–1 (AHA), and 40.38 mg C ∙ L–1 (FA).

Data availability

The data supporting this study are available upon reasonable request.

References

Chaturvedi, A., Rai, B. N., Singh, R. S. & Jaiswal, R. P. A comprehensive review on the integration of advanced oxidation processes with biodegradation for the treatment of textile wastewater containing azo dyes. Rev. Chem. Eng. 38, 617–639 (2022).

Keshta, B. E. et al. Preparation of unsaturated MIL-101(Cr) with Lewis acid sites for the extraordinary adsorption of anionic dyes. npj Clean Water 8, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-024-00413-7 (2025).

Sen, S. K., Raut, S., Bandyopadhyay, P. & Raut, S. Fungal decolouration and degradation of azo dyes: A review. Fungal Biol. Rev. 30, 112–133 (2016).

Shu, D. et al. Enhanced degradation and recycling of reactive dye wastewater using cobalt loaded MXene catalysts. npj Clean Water 7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-024-00391-w (2024).

Selvaraj, V., Swarna Karthika, T., Mansiya, C. & Alagar, M. An over review on recently developed techniques, mechanisms and intermediate involved in the advanced azo dye degradation for industrial applications. J. Mol. Struct. 1224, 129195 (2021).

Dias, N. C., Alves, T. L. M., Azevedo, D. A., Bassin, J. P. & Dezotti, M. Metabolization of by-products formed by ozonation of the azo dye Reactive Red 239 in moving-bed biofilm reactors in series. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 37, 495–504 (2020).

Muniyasamy, A. et al. Process development for the degradation of textile azo dyes (mono-, di-, poly-) by advanced oxidation process - Ozonation: Experimental & partial derivative modelling approach. J. Environ. Manag. 265, 110397 (2020).

Detjob, A., Boonnorat, J. & Phattarapattamawong, S. Synergistic decolorization and detoxication of reactive dye Navy Blue 250 (NB250) and dye wastewater by the UV/Chlorine process. Environ. Eng. Res. 28, 220221–220220 (2022).

Solayman, H. M. et al. Performance evaluation of dye wastewater treatment technologies: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 109610 (2023).

Lee, Y.-J., Lee, C.-G., Park, S.-J., Moon, J.-K. & Alvarez, P. J. J. pH-dependent contribution of chlorine monoxide radicals and byproducts formation during UV/chlorine treatment on clothianidin. Chem. Eng. J. 428, 132444 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. UV photoreduction-driven heterogeneous fenton-like process: Long-term reactivation of fenton sludge-derived biochar and enhanced acetaminophen degradation. J. Water Process Eng. 68, 106411 (2024).

Yin, B., Li, C., Tian, Z., Chen, R. & Zhao, Y. Effective catalytic ozonation of Orange G by supported Ce–Fe-Co oxides on Al2O3: Performance, mechanism and selective oxidation. J. Water Process Eng. 69, 106752 (2025).

Turhan, K. & Ozturkcan, S. A. Decolorization and Degradation of Reactive Dye in Aqueous Solution by Ozonation in a Semi-batch Bubble Column Reactor. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 224, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-012-1353-8 (2012).

de Souza, S. M., Bonilla, K. A. & de Souza, A. A. Removal of COD and color from hydrolyzed textile azo dye by combined ozonation and biological treatment. J. Hazard Mater. 179, 35–42 (2010).

Li, X., Chen, W., Ma, L., Huang, Y. & Wang, H. Characteristics and mechanisms of catalytic ozonation with Fe-shaving-based catalyst in industrial wastewater advanced treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 222, 174–181 (2019).

Wu, G., Qin, W., Sun, L., Yuan, X. & Xia, D. Role of peroxymonosulfate on enhancing ozonation for micropollutant degradation: Performance evaluation, mechanism insight and kinetics study. Chem. Eng. J. 360, 115–123 (2019).

Yang, S., Song, Y., Chang, F. & Wang, K. Evaluation of chemistry and key reactor parameters for industrial water treatment applications of the UV/O(3) process. Environ. Res 188, 109660 (2020).

Chen, W. et al. A comprehensive review on metal based active sites and their interaction with O(3) during heterogeneous catalytic ozonation process: Types, regulation and authentication. J. Hazard Mater. 443, 130302 (2023).

Ikhlaq, A. et al. Catalytic ozonation for the removal of methyl orange in water using iron-coated Moringa oleifera seeds husk. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 199, 107248 (2025).

Niu, J., Yuan, R., Chen, H., Zhou, B. & Luo, S. Heterogeneous catalytic ozonation for the removal of antibiotics in water: A review. Environ. Res 262, 119889 (2024).

Xiong, W. et al. Ozonation catalyzed by iron- and/or manganese-supported granular activated carbons for the treatment of phenol. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res Int 26, 21022–21033 (2019).

Khan, M. D., Chottitisupawong, T., Vu, H. H. T., Ahn, J. W. & Kim, G. M. Removal of Phosphorus from an Aqueous Solution by Nanocalcium Hydroxide Derived from Waste Bivalve Seashells: Mechanism and Kinetics. ACS Omega 5, 12290–12301 (2020).

Choi, S. H. et al. Toward transformation of bivalve shell wastes into high value-added and sustainable products in South Korea: A review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 129, 38–52 (2024).

Zhan, J., Lu, J. & Wang, D. Review of shell waste reutilization to promote sustainable shellfish aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 14, 477–488 (2021).

He, C. et al. Preparation of Micro-Nano Material Composed of Oyster Shell/Fe(3)O(4) Nanoparticles/Humic Acid and Its Application in Selective Removal of Hg(II). Nanomaterials (Basel) 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9070953 (2019).

Yen, H. Y. & Li, J. Y. Process optimization for Ni(II) removal from wastewater by calcined oyster shell powders using Taguchi method. J. Environ. Manag. 161, 344–349 (2015).

Quan, X. et al. Ozonation of acid red 18 wastewater using O3/Ca(OH)2 system in a micro bubble gas-liquid reactor. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 5, 283–291 (2017).

Zhang, C. et al. Feasibility of intimately coupled CaO-catalytic-ozonation and bio-contact oxidation reactor for heavy metal and color removal and deep mineralization of refractory organics in actual coking wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 408, 131154 (2024).

Liu, J., Liu, A., Li, J., Liu, S. & Zhang, W. -x Probing the performance and mechanisms of Congo red wastewater decolorization with nanoscale zero-valent iron in the continuing flow reactor. J. Clean. Prod. 346, 131201 (2022).

Rezvani, B., Nabavi, S. R. & Ghani, M. Magnetic nanohybrid derived from MIL-53(Fe) as an efficient catalyst for catalytic ozonation of cefixime and process optimization by optimal design. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 177, 1054–1071 (2023).

Li, K. et al. Effect of pH on degradation and mineralization of catechol in calcium-aid ozonation: Performance, mechanism and products analysis. Sep. Purif. Technol. 349, 127839 (2024).

Shah, S. A. A., Gkoulemani, N., Irvine, J. T. S., Sajjad, M. T. & Baker, R. T. Synthesis of high surface area mesoporous ZnAl2O4 with excellent photocatalytic activity for the photodegradation of Congo Red dye. J. Catal. 439, 115769 (2024).

Hernandez-Zamora, M. & Martinez-Jeronimo, F. Congo red dye diversely affects organisms of different trophic levels: a comparative study with microalgae, cladocerans, and zebrafish embryos. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res Int 26, 11743–11755 (2019).

Pious, A. et al. Micelle assisted synthesis of bismuth oxide nanoparticles for improved chemocatalytic degradation of toxic Congo red into non-toxic products. N. J. Chem. 48, 96–104 (2024).

Janković, B., Manić, N., Jović, M. & Smičiklas, I. Kinetic and thermodynamic analysis of thermo-oxidative degradation of seashell powders with different particle size fractions: compensation effect and iso-equilibrium phenomena. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 147, 2305–2334 (2021).

Suwannasingha, N. et al. Effect of calcination temperature on structure and characteristics of calcium oxide powder derived from marine shell waste. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 26, 101441 (2022).

Wu, F. et al. Increasing flexural strength of CO2 cured cement paste by CaCO3 polymorph control. Cem. Concr. Compos. 141, 105128 (2023).

Bai, H., Liu, X., Bao, F. & Zhao, Z. Synthesis of micronized CaO assisted by NH4HCO3 with Ca(OH)2 and its application in heterogeneously catalyzing transesterification reaction for producing biodiesel. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 66, 1604–1609 (2019).

Choi, M.-Y., Lee, C.-G. & Park, S.-J. Conversion of Organic Waste to Novel Adsorbent for Fluoride Removal: Efficacy and Mechanism of Fluoride Adsorption by Calcined Venerupis philippinarum Shells. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 233, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-022-05757-9 (2022).

Jang, S.-H. et al. Green utilization of Meretrix lusoria shell for phosphorus removal, pathogenic bacteria inactivation, and phosphorus supply for crop growth. J. Water Process Eng. 76, 108271 (2025).

Lee, Y.-J. et al. The inhibitory mechanism of humic acids on photocatalytic generation of reactive oxygen species by TiO2 depends on the crystalline phase. Chem. Eng. J. 476, 146785 (2023).

Tizaoui, C., Grima, N. M. & Derdar, M. Z. Effect of the radical scavenger t-butanol on gas–liquid mass transfer. Chem. Eng. Sci. 64, 4375–4382 (2009).

Wang, Y., Duan, X., Xie, Y., Sun, H. & Wang, S. Nanocarbon-Based Catalytic Ozonation for Aqueous Oxidation: Engineering Defects for Active Sites and Tunable Reaction Pathways. ACS Catal. 10, 13383–13414 (2020).

Lee, Y. J., Jung, S. H. & Lee, C. G. Oxidation of urea to nitrate via persulfate activation under far-UVC light improves ultrapure water production. J. Hazard Mater. 498, 139987 (2025).

Sun, F. et al. A quantitative analysis of hydroxyl radical generation as H2O2 encounters siderite: Kinetics and effect of parameters. Appl. Geochem. 126, 104893 (2021).

Yang, W., Vogler, B., Lei, Y. & Wu, T. Metallic ion leaching from heterogeneous catalysts: an overlooked effect in the study of catalytic ozonation processes. Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol. 3, 1143–1151 (2017).

Mustafa, F. S. & Oladipo, A. A. Rapid degradation of anionic azo dye from water using visible light-enabled binary metal-organic framework. J. Water Process Eng. 64, 105686 (2024).

Zhang, C. et al. A critical review of the aniline transformation fate in azo dye wastewater treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 321, 128971 (2021).

Zhao, C. et al. Influence of multivalent background ions competition adsorption on the adsorption behavior of azo dye molecules and removal mechanism: Based on machine learning, DFT and experiments. Sep. Purif. Technol. 341, 126810 (2024).

Keshavarz, M. H., Shirazi, Z., Jafari, M. & Jorfi Shanani, S. M. Predicting aqueous-phase hydroxyl radical reaction kinetics with organic compounds in water, atmosphere, and biological systems. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 196, 106876 (2025).

Wang, Y., Rodriguez, E. M., Rentsch, D., Qiang, Z. & von Gunten, U. Ozone Reactions with Olefins and Alkynes: Kinetics, Activation Energies, and Mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 59, 4733–4744 (2025).

Du, Z., Yang, E.-H. & Unluer, C. Investigation of the properties of Mg(OH)2 extracted from magnesium-rich brine via the use of an industrial by-product. Cem. Concr. Compos. 152, 105658 (2024).

Zhang, T., Yang, P., Ji, Y. & Lu, J. The Role of Natural Organic Matter in the Degradation of Phenolic Pollutants by Sulfate Radical Oxidation: Radical Scavenging vs Reduction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 59, 3325–3335 (2025).

Zeng, Z.-J. et al. Molecular weight fraction-specific transformation of natural organic matter during hydroxyl radical and sulfate radical oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 498, 155397 (2024).

Zhang, S., Jiang, J.-Q. & Petri, M. Preliminarily comparative performance of removing bisphenol-S by ferrate oxidation and ozonation. npj Clean Water 4, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-020-00095-x (2021).

Ozdemir, S., Cirik, K., Akman, D., Sahinkaya, E. & Cinar, O. Treatment of azo dye-containing synthetic textile dye effluent using sulfidogenic anaerobic baffled reactor. Bioresour. Technol. 146, 135–143 (2013).

R Ananthashankar, A. E. G. Production, Characterization and Treatment of Textile Effluents: A Critical Review. Journal of Chemical Engineering & Process Technology 05, https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7048.1000182 (2013).

Jamee, R. & Siddique, R. Biodegradation of Synthetic Dyes of Textile Effluent by Microorganisms: An Environmentally and Economically Sustainable Approach. Eur. J. Microbiol Immunol. (Bp) 9, 114–118 (2019).

de Oliveira, D. M. et al. Identification of intermediates, acute toxicity removal, and kinetics investigation to the Ametryn treatment by direct photolysis (UV(254)), UV(254)/H(2)O(2), Fenton, and photo-Fenton processes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res Int 26, 4348–4366 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) through the Aquathermal Utilization and Energy Mix Research Program funded by the Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE) (RS-2025-02214066).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

**S.H.J** : Formal analysis, conceptualization, methodology, and writing of the original draft. **S.H.H** : Methodology and conceptualization, **Y.J.L** : Methodology and writing of the original draft. **S.J.P** : Conceptualization and supervision. **E.H.J** : Methodology, and supervision. **C.G.L** : Review and editing, funding acquisition, supervision, and validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jung, SH., Hong, SH., Lee, YJ. et al. Enhancing ozonation using Meretrix lusoria shell waste biomass: sustainable decontamination of azo dye wastewater via decolorization, mineralization, and detoxification. npj Clean Water 9, 5 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00542-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00542-7