Abstract

The Andromeda galaxy is surrounded by a strikingly asymmetrical distribution of satellite dwarf galaxies aligned towards the Milky Way. The standard model of cosmology predicts that most satellite galaxy systems are near-isotropic, and dwarf associations observed in the local Universe are only weakly asymmetric. Here we characterize the Andromeda system’s asymmetry and test its agreement with expectations from concordance cosmology. All but one of Andromeda’s 37 satellite galaxies are contained within 107° of our Galaxy. In standard cosmological simulations, less than 0.3% (0.5% when accounting for possible observational incompleteness) of Andromeda-like systems show a comparably significant asymmetry. None are as collectively lopsided as the observed satellite configuration. In conjunction with its satellite plane, our results paint the Andromeda system as an extreme outlier in the prevailing cosmological paradigm, further challenging our understanding of structure formation at small scales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Dwarf satellite galaxies serve as the building blocks of structure formation in the standard Λ cold dark matter (ΛCDM, where Λ is the cosmological constant) paradigm of cosmology1, and are predicted to be distributed in a near-isotropic manner around their more massive host galaxies2. The unexpected presence of flattened and co-rotating planes of satellites around the Milky Way3,4 and Andromeda5 galaxies, as well as a handful of dwarf associations beyond the Local Group6,7,8,9,10,11,12, are hence difficult to explain in the context of concordance cosmology. Similarly anisotropic satellite distributions are highly rare (<1%) in cosmological simulations based on the ΛCDM framework4,6,13, sparking an active and enduring debate on whether this discrepancy indeed constitutes a challenge to our understanding of small-scale structure formation14,15,16,17.

While satellite planes are generally characterized under an assumption of axial symmetry, an alternative signature of spatial anisotropy can be found in the strikingly asymmetrical distribution of satellites around the Andromeda galaxy (Messier 31, M31). Around 80% of M31’s satellites lie within a hemispheric region facing the Milky Way18, a fraction that has persisted throughout improvements in dwarf distance estimates and the discovery of previously unknown satellites over the past two decades19,20. While the excess of satellites detected on the near side of Andromeda may hint at the role of photometric completeness, the distribution of satellites brighter than the limiting magnitude MV ≤ −7.5 at the far side of M31’s virial radius21 shows a similar degree of lopsidedness to that of the full sample18. Surveys with a given footprint also cover a larger physical volume on the far side of Andromeda, counteracting the comparative ease of detecting satellites at closer distances. The observed asymmetry is likely of physical origin, although its formation history remains unclear22.

While the Andromeda system hosts the most populated and well-studied dwarf association that shows a prominent asymmetry in its spatial distribution, a weaker degree of lopsidedness among satellites of paired host galaxies appears to be prevalent in the local Universe. One group23 examined tens of thousands of Local Group-like host galaxy pairs in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, detecting up to a 10% excess of satellites in the region between paired hosts. A comparable overabundance was later found for analogous host pairs in cosmological N-body simulations24. Curiously, satellites observed around isolated host galaxies also show a tendency to lie on the same side of their hosts25,26 to a degree roughly consistent with their simulated analogues27.

Nevertheless, these large-volume studies are limited by their low median sample size of only three or four satellites per host. These small samples hinder any in-depth analysis of their individual satellite distributions, especially at the far end of the satellite luminosity function. This motivates a closer examination of the M31 system, which remains the most populated, strongly asymmetric satellite association in our cosmic neighbourhood. Savino et al.18 recently released a set of RR Lyrae-based distance measurements for 39 stellar systems in the M31 system. This sample includes nearly all known satellites within Andromeda’s virial radius of 266 kpc (ref. 28) and several others, as well as the Andromeda galaxy itself to anchor them. Adopting these homogeneous distances, we investigate the nature of Andromeda’s asymmetric satellite distribution and quantify the incidence of similarly lopsided analogues in ΛCDM cosmological simulations.

We use a combination of Hubble Space Telescope archival data and the recently obtained distances compiled in ref. 18. Of the 39 stellar systems listed, we mirror the authors’ analysis by excluding the Giant Stellar Stream. Accordingly, we make use of heliocentric distances for 37 satellite galaxies and M31 itself. This sample includes most satellites located within the Pan-Andromeda Archaeological Survey (PAndAS) footprint (out to a projected ~150 kpc from M31), but contains several additional dwarfs at larger radii (and the satellites XXXI–XXXIII)29,30. Of the 37 M31 satellites, 7 lie beyond Andromeda’s adopted virial radius. For ease of comparison with previous work on the Andromeda system18,19,20, satellite positions are transformed to a Cartesian reference frame aligned with the Galactic coordinate system, centred on the expected position of M31, as shown in Fig. 1. Andromeda’s galactic disk is aligned with the longitudinal plane and the positive Z axis (b = 90°) points to M31’s north galactic pole, while the Milky Way lies at the same azimuth as the positive X axis (l = 0°). Distance uncertainties are accounted for by generating 10,000 Monte Carlo realizations per satellite.

Figure constructed using data from ref. 18. Satellites are projected onto the X–Z plane of our adopted M31-centric coordinate system19—the positive X axis has the same azimuth (l = 0°) as the Milky Way (MW) and the positive Z axis points to M31’s north galactic pole. The shaded dark grey circle represents the position of M31. Satellites are coloured by their angular separation from the Milky Way as seen from M31’s expected position and the corresponding Monte Carlo uncertainties are drawn in black. The dashed circle encompasses M31’s virial radius of 266 kpc (ref. 28) and the shaded sector within represents a two-dimensional projection of the angular region within 106.5° of the Milky Way, in which all but one of M31’s 37 satellites are contained.

The on-sky distribution of Andromeda’s satellites as seen from their host galaxy is plotted in Fig. 2. Even upon a cursory examination, the area-preserving property of the adopted Aitoff–Hammer projection highlights a remarkable dearth of satellites on the far side of M31—only a single bright dwarf, NGC 205, lies within 73° of the line of sight. Twenty-nine satellites (78%) are contained within the hemisphere facing the Milky Way, and up to 32 satellites (86%) lie on one side of the Andromeda galaxy—the normal vector to the plane of maximum asymmetry separating them with the remaining 5 satellites is oriented to within 17° of the Milky Way’s direction. The geometric centroid of Andromeda’s satellite distribution is displaced by as much as 75 ± 15 kpc from M31’s position and lies at a 37° offset from our Galaxy (reduced to 22° when disregarding the outlying Pegasus Dwarf (Peg DIG) and IC 1613). The M31 satellites’ asymmetric distribution is evidently aligned quite closely with the Milky Way.

This equal-area Aitoff sky projection in our adopted M31-centric coordinate system19 shows the expected positions of 37 M31 satellites, coloured according to their absolute magnitudes as compiled in ref. 18. Corresponding Monte Carlo distance uncertainties are drawn in black. Satellites with over a 50% chance of participating in M31’s satellite plane18 are drawn as circles and off-plane satellites are marked with triangles. The coloured smaller points each represent the direction of the most populated conical region with a given opening angle θ. The purple cross and line indicate the orientation and bounds of the hemispheric region (θ = 90°) that contains a maximum of 32 satellites, and the dashed purple line delineates a hemispheric region with 29 satellites locked in the direction of the Milky Way. The orange cross and line represent the orientation and bounds of the most significant cone (θ = 101°) containing 36 satellites, and the dashed orange line corresponds to the smallest cone also containing 36 satellites (θ = 106.5°) but oriented towards our Galaxy. The direction of the satellite distribution’s geometric centroid and mean resultant length (Supplementary Information) are shown as blue and red plus symbols. Andromeda’s satellite galaxies form a strongly asymmetrical distribution that is aligned towards the Milky Way.

The commonly used, hemisphere-based metric for quantifying the M31 system’s lopsidedness18,19,20,21 struggles to identify less-populated satellite agglomerations constrained to small solid angles or ‘voids’ in angular space unnaturally devoid of satellites. For improved flexibility, we adopt an alternative method as follows. We generate conical regions with opening angles within θ = [0.5, 180]° in 0.5° increments (where θ = 180° corresponds to a full sphere), oriented along 105 isotropically distributed vectors on a unit sphere. For each θ, we identify the corresponding cone that encloses the maximal population N(θ) of Andromeda’s satellites (Fig. 3), which we refer to as the cone of maximum asymmetry. To quantify the M31 system’s lopsidedness specifically towards the Milky Way, we additionally generate one companion-locked cone per θ oriented in our Galaxy’s direction. The latter approach is equivalent to the hemisphere-based metric at θ = 90°. In Fig. 2, cones of maximum asymmetry with lower θ are concentrated in the southwestern quadrant along smaller clusters of satellites, many of which participate in M31’s satellite plane5,18. At larger opening angles (and correspondingly larger N(θ) in Fig. 3), cone orientations show a markedly closer alignment with the Milky Way.

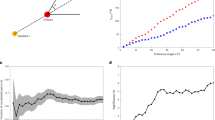

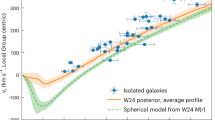

a,b, Maximum number of satellites contained within a cone facing in any direction (a) and the number of satellites contained within a cone oriented towards the companion host galaxy (b) with opening angle θ. Results for the observed Andromeda satellites are shown as black lines. The median relationship for the M31 system’s analogues in the TNG and EAGLE simulations are shown as red and blue lines, respectively, and the combined 1σ, 2σ and 3σ spreads for all simulated analogues are delineated in purple. The isotropic expectation is plotted with grey dotted lines. A significant deviation of Andromeda’s black line from the simulated medians represents a departure from ΛCDM expectations.

To determine the statistical significance of the observed asymmetry, we compare the M31 satellites with an isotropic satellite distribution. If every galaxy has a 50% chance of being on either side of M31, the probability of finding at least 29 out of 37 satellites on the near side of Andromeda is 4 × 10−4. The hemispheric M31 satellite distribution is therefore statistically different from the isotropic model with a significance of 3.3σ. We can also extend this analysis to opening angles other than 180°. Each companion-locked cone covers a fraction sin2(θ/2) of a unit sphere’s surface. The most significant configuration of Andromeda’s satellites lies within θ = 106.5° with a corresponding binomial probability of 1.6 × 10−6. The full Andromeda system is distinct from an isotropic distribution of satellites at the 4.7σ confidence level.

Comparison with ΛCDM simulations

Although the observed satellite distribution is unlikely to occur by chance, this alone does not allow us to determine the Andromeda system’s agreement with expectations from ΛCDM cosmology. Indeed, a weak degree of asymmetry appears to be prevalent among satellite galaxy systems in cosmological simulations24,27. This anisotropy can be attributed to the accretion of subhaloes from preferential directions, along cosmic filaments and in gravitationally bound groups31—thus forming a substantial population of dynamically young satellites that have yet to relax in their host galaxy’s halo32. To determine whether these processes are sufficient to explain the observed asymmetry in Andromeda’s satellite distribution, we examined the incidence of similarly lopsided distributions in two cosmological simulations: the IllustrisTNG suite’s TNG10033 run and the Evolution and Assembly of Galaxies and their Environments (EAGLE)34 suite’s fiducial run. We further validate the robustness of our results in the higher-resolution TNG50 run (Supplementary Information). In addition to gravitational effects and structure formation in a standard Planck cosmology, both simulation suites include baryonic processes such as stellar feedback and the disruption of dwarf satellites due to enhanced tidal forces from the host galaxy’s baryonic disk35.

We identify M31 analogues by finding dark matter haloes with virial masses (M200) between 5 × 1011 M⊙ and 3 × 1012 M⊙, a range centred upon but broadened from the mass criteria previously used in studies of M31’s satellite plane13,14 for improved statistics. For each simulated host galaxy, we search for nearby haloes with mass >0.25 M200 within 5 virial radii (R200) (Supplementary Information) and classify systems as paired or isolated by whether a companion is found. Each M31 analogue is required have at least 37 satellites within 2 R200, an initial sample from which the 37 most massive satellites are selected. We fix the satellite population of simulated systems as metrics of phase-space correlation show an intrinsic correlation36 with the number of satellites. We thus obtain 1,268 and 1,107 systems from TNG100 and EAGLE of which 184 and 141 have a companion galaxy, respectively.

Distance uncertainties are traditionally accounted for by sampling the prior of the observed satellites. However, this approach is equivalent to applying uncertainties twice—once upon observation and once more when compensating for the initial distance errors. If Andromeda’s true satellite distribution were heavily lopsided, we would therefore systematically wash out the existing asymmetry. We instead mock-observe the simulated host galaxies and their satellite distributions at M31’s distance of \(77{6}_{-21}^{+22}\,{\rm{kpc}}\) (ref. 18), applying the observed satellite distance uncertainties to generate 100 Monte Carlo realizations per simulated system (Supplementary Information).

Figure 3a shows the population of satellites contained within cones of maximum asymmetry around Andromeda’s simulated analogues. Satellite systems in a ΛCDM context show a considerable degree of lopsidedness. All 37 satellites are contained within θ = 135° (or equivalently, there exists an angular void of θ = 45°) around over 70% of M31 analogues. Nevertheless, the observed Andromeda system deviates significantly from the simulated median at larger opening angles. This deviation peaks at a cone of maximum asymmetry with θ = 101° containing 36 out of 37 satellites, aligned to within 6° of the Milky Way’s direction. We find that the incidence of a similarly asymmetric configuration is 0.45% in both TNG and EAGLE (Fig. 4a). The departure from ΛCDM expectations is enhanced when solely considering asymmetry oriented towards a companion galaxy in Fig. 3b, which peaks at a companion-locked cone with θ = 106.5° also containing all but one satellite. In simulations, none of TNG and EAGLE’s 325 paired M31 analogues can reproduce the Andromeda system’s observed asymmetry towards our Galaxy (Fig. 4b), effectively setting an upper limit of 0.3% on the frequency of M31-like lopsided systems.

a,b, The fraction of simulated M31 analogues that show an equal or greater degree of asymmetry to the Andromeda system are plotted as a function of the opening angle θ of cones either facing in the direction that maximizes their contained satellites (a) or oriented towards their host galaxy’s companion (b). Comparisons for analogue systems sampled from TNG and EAGLE are drawn as red and blue lines, respectively. In b, analogue fractions corresponding to exactly one simulated realization are indicated by dashed lines of the matching colour. Each trough corresponds to an additional satellite within the conical region.

The Andromeda system shows a degree of asymmetry that, in its current configuration, is remarkably rare among its simulated analogues. However, it may be argued that our selected θ was specifically chosen to maximize Andromeda’s discrepancy with simulations—we do not know a priori the opening angle at which simulated systems are most significantly lopsided. To compare the M31 system’s generalized asymmetry with ΛCDM expectations, we need to take into account the look-elsewhere effect, a statistical phenomenon wherein an apparently significant result may arise by chance due to the extended parameter space searched15.

To compare Andromeda and its analogues on a balanced playing field, we generate a reference sample of 106 systems, each consisting of 37 unit vectors drawn from isotropy. For each simulated system (and the observed Andromeda system itself), we obtain the fraction fiso(θ) of this reference sample that matches or exceeds the given system’s satellite population N(θ) within its cone of maximum asymmetry. A companion vector is also randomly drawn to enable a similar analysis using companion-locked cones instead. For each family of cones, we determine the system’s minimum fiso(θ) across all opening angles, which we refer to as its minimum isotropic frequency (MIF). By adopting the MIF in lieu of N(θ) as our metric of lopsidedness, we compare satellite systems in their most significantly asymmetric configurations.

Using cones of maximum asymmetry, as many as 4.5% of M31 analogues in TNG and 6.2% in EAGLE match Andromeda’s MIF of 7 × 10−5. Paired and isolated analogues show similar incidences at 5.6% and 5.3%, respectively. Although the significance of a majority of these systems is driven by smaller clusters of satellites rather than a collective asymmetry (Supplementary Information), we recover a tenfold increase in incidence over the fixed-θ comparison in Fig. 4. In contrast, Andromeda’s satellite distribution remains an outlying case with regards to its asymmetry towards the Milky Way. Only 0.3% of TNG and EAGLE realizations can reproduce the observed MIF of 2 × 10−6, thus yielding an incidence that remains similar to the previous fixed-θ comparison. Strikingly, we find that none of these few realizations are driven in significance by a companion-locked asymmetry at an opening angle as large as M31’s 106.5° or a dwarf population above 33 satellites (Fig. 5). The Andromeda system’s asymmetry towards our Galaxy occurs at a more population-wide scale than any of its similarly significantly lopsided analogues in cosmological simulations. Repeating this method for the observationally complete sample of 30 M31 satellites18 instead yields an incidence of 0.5%, which serves as an upper bound to the simulated frequency of M31-like asymmetric systems (Supplementary Information).

Each simulated analogue’s cone opening angle at MIF and corresponding satellite population are plotted on the horizontal and vertical axes, respectively, when cones are oriented towards the analogue’s companion galaxy. Most systems are coloured according to their MIF, and the few simulated analogues that show MIFs equal to or less than that of Andromeda are drawn as black crosses. Satellite counts for coloured systems are shifted within [−0.5, 0.5] for visibility. The result for the M31 system itself is indicated by the white circle. The Andromeda system’s asymmetry towards the Milky Way is more population-wide than any of its similarly significantly lopsided analogues.

Implications for structure formation

We have shown that Andromeda’s asymmetric distribution of satellite galaxies towards the Milky Way is highly unexpected in a full cosmological context. The formation of this anisotropic structure around M31 poses a puzzle that—given its rarity among simulated analogues—requires a unique evolutionary history to explain. Given the excellent alignment of the Andromeda system’s asymmetry with our Galaxy, could the Milky Way potentially play a role in maintaining the observed lopsidedness? If that were the case, assuming that the two Local Group host galaxies are of similar mass, the Milky Way satellites should also experience a comparable effect from M31’s potential. However, while difficult to reliably ascertain owing to uneven sky coverage due to survey footprints and obscuration from the Galactic Disk, no noteworthy degree of asymmetry has been reported in the Milky Way’s satellite distribution37. Tidal effects are also unlikely to be strong enough to reproduce the observed asymmetry38. Nevertheless, the 6° alignment between M31’s most significant cone of maximum asymmetry and the Milky Way’s direction occurs at only a sin2(θ/2) = 0.27% likelihood if the orientation of the observed asymmetry is random—strongly hinting at the role of our Galaxy as important to the formation or evolution of the lopsided Andromeda system.

One group22 explored the possibility of a single accretion of a well-populated association of satellites forming the current Andromeda system. Given the observed distribution’s wide radial distribution and range of orbital energies, however, they found that the resulting asymmetric structure would likely dissolve as soon as 500 Myr later. In this scenario, the prominent asymmetry observed in the Andromeda system must be dominated by a dynamically young population of satellites. A similar excess of recently accreted satellites may also exist around the Milky Way39,40. While the weak lopsided signal in simulated paired hosts is indeed driven by satellites recently accreted from nearby filaments32, such processes are already self-consistently included in the cosmological simulations searched. Furthermore, if the observed asymmetry were driven by recent-infall satellites, the well-populated nature of M31’s lopsided satellite distribution would imply a catastrophic dearth of satellites with an infall time older than the asymmetry’s dispersion timescale.

Unlike the apparent ubiquity of correlated planes of satellites in our cosmic neighbourhood4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12, statistical samples of dwarf associations in the local Universe23,25,41 generally show a degree of lopsidedness consistent with simulations. This strengthens the need for a unique evolutionary history for M31 within a ΛCDM context. Nevertheless, the limited satellite populations in these samples may mask individual systems that are comparably asymmetric as the Andromeda group. Next-generation surveys with lower surface brightness limits42,43,44 will be necessary to conclusively determine whether the incidence of individual, highly asymmetric satellite systems also aligns with cosmological expectations.

In this paper, we have demonstrated that the satellite galaxies around Andromeda form a strongly asymmetric distribution aligned with the Milky Way. Even when accounting for the look-elsewhere effect, similarly lopsided configurations of satellites only occur around <0.3% of M31 analogies in ΛCDM cosmological simulations, and no single simulated system can simultaneously reproduce the population-wide nature of the observed lopsidedness. At present, no known formation mechanism can explain the collective asymmetry of the Andromeda system22. In conjunction with M31’s plane of satellites, which holds a similar degree of tension with simulations13, our results present the satellite galaxy system of Andromeda as a striking outlier from expectations in ΛCDM cosmology.

Methods

We made use of RR Lyrae-based distances for the Andromeda galaxy and 37 of its dwarf satellites compiled in ref. 18. From this published sample of stellar systems, we excluded the heavily disrupted Giant Stellar Stream. We included IC 1613 and Peg DIG in our working sample despite their outlying distance from M31, but confirmed that their exclusion does not significantly affect our results. The recently discovered Peg V45 lacks the deep Hubble Space Telescope imaging necessary for the RR Lyrae approach. Its associated TRGB distance of \(69{2}_{-31}^{+33}\,{\rm{kpc}}\) places it firmly on the near side of M31, intensifying the existing asymmetrical trend. Dwarf coordinates were taken from the Local Volume catalogue46,47, a compilation of galactic objects within 10 Mpc from the Local Group.

We accounted for the associated distance uncertainties by generating 10,000 Monte Carlo realizations as follows. For each realization, distance errors were drawn from a Gaussian distribution for each satellite galaxy (with a standard deviation equivalent to the quoted uncertainty) and applied to their expected positions along the respective line-of-sight vectors. A distance error for M31 was then drawn in the same way, and was further applied to all satellite positions along M31’s line of sight—thus yielding realizations still centred on the system’s host galaxy. Note that errors modelled by this Monte Carlo approach were only used to quantify the properties of the observed M31 system (and hence in Fig. 2).

Primary metrics of asymmetry

The most straightforward manner in which one may quantify the degree of asymmetry in a given satellite system is by counting the number of satellites on each side of an arbitrarily oriented plane, which effectively divides the system into two hemispheres. By repeating this check for 100,000 planes with isotropically distributed normal vectors, we found the plane that shows the greatest disparity between the two hemispheric satellite populations—we refer to this plane as the ‘plane of maximum asymmetry’. The two satellite populations on either side of the plane of maximum asymmetry is usually expressed as a ratio, but as all sampled systems have exactly 37 satellite galaxies, we simply quote the number of satellites in the more populated hemisphere as the system’s maximum hemisphere population Nlop. The orientation of the system’s asymmetry is expressed as the normal vector of the plane of maximum asymmetry, pointing towards the direction of satellite excess. It is important to note that more than one hemisphere containing the same, maximized set of satellites can exist if the maximum angular range spanned by the satellites is marginally less than 180°. Hence, the orientation of a system’s lopsidedness according to the hemisphere metric entails a small degree of intrinsic error.

For systems of paired hosts, an often-used variation of this metric18,20,24 effectively ‘locks’ the dividing plane’s normal vector to the vector pointing from the satellites’ host galaxy to its companion: the ‘pair vector’, \({\hat{x}}_{{\rm{pair}}}\). The population of the hemisphere oriented in the same sense as the pair vector is denoted Nlop,pair, although it and Nlop are frequently used interchangeably in the literature due to the M31 system’s hemispheric asymmetry being roughly oriented towards the Milky Way.

Although the maximum hemisphere population of a given satellite distribution is the most intuitive metric by far, it fails in identifying satellite clusters constrained to a small solid angle or angular regions unnaturally devoid of satellites. For a more comprehensive characterization of satellite excesses and underdensities, we defined a series of cones with corresponding opening angles θ (up to a full sphere at θ = 180°). For each cone, we generated 100,000 isotropically distributed so-called grid vectors, centred the cone on each grid vector and identified the number of satellites enclosed within the conical volume. For each θ, we recorded the most populated cone—with an associated population Nθ—and its orientation. As such, each of these cones of maximum asymmetry may be oriented in different directions with varying θ. We generated 359 cones per system, spanning a range of θ = [0.5, 180]° in 0.5° increments. Much like the hemisphere metric, the orientation of the cones may be ‘locked’ to a host galaxy’s pair vector \({\hat{x}}_{{\rm{pair}}}\) (ref. 24). In this case, the number of satellites in each companion-locked cone with opening angle θ is denoted Nθ,pair.

A weakness of both of the above approaches is the unintuitive nature of deriving Nlop and Nθ expected in an isotropic satellite distribution. In the limit of an infinitely populated system, we can approximate the satellite distribution as a constant-density field, and may hence expect the hemisphere or cone of maximum asymmetry to enclose 1/2 or Ω/4π of the satellite population (where \(\varOmega =4\uppi {\sin }^{2}(\theta /2)\) is the solid angle associated with the cone’s opening angle θ). However, with a realistic and limited number of satellites, there will generally exist a hemisphere or cone that manages to capture more than the above expectation. A system of two satellites will always yield Nlop = 2, for instance, unless the satellites happen to be perfectly diametrically opposed. Conversely, the companion-locked variants follow the naive expectation from isotropy if pair vectors are randomly drawn.

Supplementary metrics of asymmetry

Lopsidedness in satellite galaxy distributions is a nuanced topic, and the metric adopted to quantify it will determine what aspects of the asymmetry are most represented. While we adopt the cone-based approach as our primary metric of asymmetry in this work, we also consider several supplementary metrics previously used in other work.

The hemisphere and cone approaches discussed above solely focus on the angular distribution of satellites while disregarding their distance from their host. Hence, the metrics are less sensitive to lopsidedness caused by a translation of the satellite distribution away from their host. To account for this, we calculated the unweighted centroid of satellites for a given system and measured its distance from the host galaxy’s position. As this centroid shift is determined by both the system’s degree of lopsidedness and the characteristic distance of its subhaloes, we normalized the shift by drms, the root-mean-square distance of the satellites from their host. This yielded dnorm, the normalized centroid shift from the system’s host galaxy. It should be noted that dnorm is highly sensitive to outlying satellites, and conversely insensitive towards those that are centrally distributed within their system. One group19 previously reported a three-dimensional centroid shift of 84 kpc derived for 16 of M31’s satellites, which drops to 50 kpc when removing the outlying Peg DIG and IC 1613 from their sample. Using the larger satellite sample from ref. 18, we recovered a similar centroid shift of 75 ± 15 kpc (or 62 ± 17 when excluding the 2 outlying satellites).

One of the most common metrics of lopsidedness found in the literature is the distribution of pairwise satellite angles20,27. In a given satellite system, each unique combination of two satellites has a corresponding angular separation, θij. The mean of θij across all possible satellite pairs—the mean pairwise angle θlop—should tend towards 90° in an isotropic distribution. A heavily lopsided distribution implies that a majority of satellites occupy a small region of angular space, and hence a reduced θlop. This approach can also be adapted for host galaxies with associated companions. Instead of measuring pairwise angles between all satellites, many studies23,24,25,32 instead measure the distribution of angles, θi,pair, between each satellite and the system’s \({\hat{x}}_{{\rm{pair}}}\). The corresponding mean angle is denoted θlop,pair. The same expectation of 90° holds for isotropic systems, while θlop,pair < 90° and θlop,pair > 90° indicate that the satellites are lopsided towards and away from the companion galaxy, respectively. The M31 system shows a mean pairwise angle of θlop = 83° ± 6° and a mean alignment with the Milky Way of θlop,pair = 70° ± 10° (when sampling distance errors from the Andromeda satellites).

Finally, the mean resultant length (MRL) is a circular statistic that effectively describes the directionality of a satellite distribution, and was recently adopted in ref. 26 as an alternative to their previous, pairwise angle approach25. For a system consisting of N satellites, each with position xi relative to their host, the MRL is defined by summing satellite unit vectors and dividing the resulting vector’s magnitude by N:

A perfectly isotropic distribution should yield \(\bar{R}=0\), whereas an unrealistic system with satellites located along a single angular position would produce \(\bar{R}=1\). The Andromeda system yields an MRL vector of magnitude \(R=0.3{6}_{-0.14}^{+0.10}\) oriented at 28° from the line of sight to the Milky Way (Fig. 2).

Sampling M31 analogues from simulations

We used data from the IllustrisTNG suite of large-volume cosmological simulations33, publicly available at www.tng-project.org. All runs contained therein adopt cosmological parameters taken from Planck48: ΩΛ = 0.6911, Ωm = 0.3089 and h = 0.6774. This suite includes three hydrodynamic runs with varying volume and resolution, as well as their dark matter-only counterparts. We elected to use the intermediate-volume TNG100-1 run due to the relatively large sample of M31 satellites that needs to be matched by any simulated analogues. TNG100-1 spans a simulation box of length 110.7 Mpc with dark matter and gas particle resolutions of MDM = 7.5 × 106 M⊙ and Mgas = 1.4 × 106 M⊙, respectively. We also used data from the EAGLE suite34 to augment our sample of simulated systems. Specifically, we selected the fiducial Ref-L0100N1504 run, which—with an associated simulation box length of 100 Mpc, cosmological parameters from Planck49, as well as comparable dark matter and gas particle resolutions of MDM = 9.70 × 106 M⊙ and Mgas = 1.81 × 106 M⊙, respectively—ensures a general degree of consistency with TNG100-1.

M31-like systems in TNG and EAGLE were obtained as follows. We first identified M31’s mass analogues by searching for dark haloes with virial masses within M200 = [0.5, 3.0] × 1012 M⊙, a range that accommodates literature estimates of M31’s halo mass within 0.7 × 1012–2.6 × 1012 M⊙ (refs. 28,50,51) while also including the more numerous, lower-mass haloes for improved statistics. This range encompasses but is broader than the mass criteria previously used in studies of M31’s satellite plane13,14, and was chosen to increase our final sample of M31 analogues. Within our adopted mass range, MIFs within the combined TNG and EAGLE sample do not show a significant correlation with halo mass. Kendall’s tau test, a statistical measure of rank correlation, yields coefficients (and corresponding P values) of 1.1 × 10−2 (P = 0.43) and 2.4 × 10−2 (P = 0.52) for cones of maximum asymmetry and companion-locked cones, respectively.

Next, we searched for companions by identifying haloes with a mass above 0.25 M200 within a distance of 5 R200 (approximately 1 Mpc), which can be more massive than the M31 analogues themselves. Fractional thresholds were used instead of absolute values due to the relatively large range covered by our halo mass criterion. If no such companions existed, we considered the system to be ‘isolated’. If exactly one companion was found, we required it to fulfil a so-called reciprocity criterion. We searched for its companions in turn using the same absolute mass and distance conditions as initially calculated for the original M31-like halo. If the companion’s only companion was the original halo, the reciprocity criterion was satisfied and we designated the system as ‘paired’. Otherwise, the original halo was rejected. We also did not consider triplets in this work, and thus rejected M31-like haloes in the case where it had two or more companions to avoid crowded fields. The distribution of host and companion masses in paired simulated systems along their three-dimensional separations is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

We assigned satellites to a given halo by identifying all subhaloes within a distance between 20 kpc and 2 R200, a range that fully encompasses the radial distribution of the adopted M31 satellites18. Using the K-band luminosity of the Andromeda dwarfs as an estimator of their stellar mass assuming M*/LK ≈ 1M⊙/L⊙ (ref. 52), 11 of the 37 M31 satellites have stellar masses below TNG100 and EAGLE’s specified Mgas. We did not expect this to significantly affect our results, however, as the phase-space distribution of satellites is generally unaffected by internal stellar feedback. Simulated subhaloes are ranked in descending order by stellar mass; then dark mass once no star particles are available. All M31 analogues were required to host at least 37 satellites. If more were found, the ranked sample was truncated to the most massive 37 satellites to match the observational sample. In addition, we filtered out systems currently experiencing major mergers by requiring that no satellite has a total mass greater than a quarter of the host galaxy’s mass. In this way, we obtained a total of 1,268 and 1,107 systems sampled from the hydrodynamic TNG100-1 and EAGLE Ref-L0100N1504 runs. The TNG sample consisted of 184 paired and 1,084 isolated systems—from EAGLE, we obtained 141 and 966 systems, respectively.

We mock-observed each simulated system with Andromeda-like distance uncertainties to yield 100 Monte Carlo realizations per system. Errors were drawn from a Gaussian distribution from each of the M31 satellites and applied randomly without replacement to each system of simulated satellites, and the same was performed for the host galaxy itself. For isolated systems, mock-observation was performed along line-of-sight vectors drawn from isotropy. For paired systems, two sets of realizations were produced: one adopted isotropic mock-observation vectors, while the other used the line of sight between the given M31 analogue and its sole companion. When using metrics of asymmetry (see the section below) that do not require a companion galaxy, the former set was used. If a companion’s direction is required by a given metric, the latter realizations were adopted instead. As we applied distance uncertainties to the M31 system’s simulated analogues, we consider only the expected positions for the Andromeda satellites for the remainder of this work.

M31’s well-populated asymmetry using cones of maximum asymmetry

MIFs (see main text) enable us to compare the observed Andromeda system and its simulated analogues using the significance of their asymmetrical satellite distributions. When disregarding the asymmetry’s alignment with any companion galaxies, we obtained an incidence of M31-like lopsided systems of 4.5% and 6.2% in TNG and EAGLE, respectively. As is the case when using companion-locked cones, however, a majority of these simulated analogues were most significant with respect to smaller clusters of satellites (Supplementary Fig. 2). Only 0.1% of simulated realizations showed an equal or smaller MIF than the M31 system while also matching the observed asymmetry’s population-wide nature with a satellite count of Nsat ≥ 36. The satellite system of Andromeda remains rare in a full cosmological context regardless of its asymmetry’s orientation.

Incidence of M31-like systems using alternative metrics

Supplementary Table 1 lists the incidence of M31-like lopsided systems in cosmological simulations when adopting alternative metrics of asymmetry. Unlike the cone-based approach, which places systems in a two-dimensional Nθ–θ space, these metrics are one-dimensional and thus do not require any consideration of the look-elsewhere effect. The Andromeda system’s incidence is consistently lower when adopting metrics that take its companion galaxy’s direction into account. The remaining metrics yield a 2–6% incidence depending on the simulation used, a result roughly consistent with the 5% obtained using cones of maximum asymmetry at each simulated analogue’s MIF. The fact that Andromeda’s incidence according to its normalized centroid shift—the only metric that takes satellite distances into account—is similar or higher than the other scale-free metrics may suggest that the observed lopsidedness is not driven by an offset of M31’s position from its satellite distribution.

Robustness with simulation resolution

Andromeda’s analogues in cosmological simulations must have 37 satellite galaxies within 2 R200 to match the observed M31 system. At TNG100 and EAGLE’s baryonic resolution, many of the lower-mass satellites among the 37 per system are dark subhaloes devoid of any stellar particles. Baryonic processes within individual dwarfs are not expected to pose a notable impact on their phase-space distribution at scales of hundreds of kiloparsecs37. Nevertheless, we tested for robustness in the higher-resolution TNG50 run53, which adopts the same cosmology and feedback prescription as TNG100 with a 15-fold increase in particle resolution. Owing to TNG50’s smaller simulation volume, we only obtained a total of 256 isolated and 54 paired M31 analogues. According to their MIFs using cones of maximum asymmetry, 5.7% of simulated realizations are as significantly lopsided as the observed Andromeda system. None of the paired analogues can reproduce the M31 satellites’ asymmetry towards the Milky Way, thus setting an upper limit of 2% (<1/54) on the true incidence of Andromeda-like systems in TNG50. In both cases, the resulting incidences are fully consistent with our results in TNG100 and EAGLE. The Andromeda system’s tension with CDM simulations is not an artefact of an insufficient particle resolution.

Exclusion of outlying satellites

Of the published sample of stellar systems in ref. 18, only 2 satellite galaxies—Peg DIG and IC 1613—lie beyond 1.5 R200 of Andromeda. It has been reported that the lopsidedness of satellite galaxy systems is driven by more distant satellites in both observations25 and simulations27,32. Hence, we excluded these two outlying galaxies and performed the same analysis as described in the main text using an alternative sample of 35 satellites and a reduced search volume of 1.5 R200 around simulated hosts. As Peg DIG and IC 1613 are both located within the excess of satellites towards the Milky Way, their removal does not change the cone opening angles at which the Andromeda system is most significant, which remains at 101° and 106. 5° for cones of maximum asymmetry and companion-locked cones, respectively. The incidence of M31-like lopsided systems in simulations with respect to the Milky Way’s direction decreases slightly to 0.2%, while the rarity of the observed system without a preferred direction remains unchanged at 5%. The outlying Peg DIG and IC 1613 satellites are not key drivers of the observed asymmetry, and their exclusion does not significantly affect the lopsided Andromeda system’s tension with cosmological expectations.

Robustness with paired host selection criteria

Our selection criteria for M31 analogues in simulations was chosen to ensure a sufficiently large sample to obtain robust statistics, but the adopted range of parameters may deviate from strictly Local Group-like systems due to the enhanced abundance of lower-mass haloes in the CDM mass function. We tested whether the main outcomes of this work are sensitive to our choice of selection criteria by subdividing our fiducial sample of paired TNG100 and EAGLE hosts into 2 bins about the median host mass (M200 = 1.33 × 1012 M⊙), relative companion mass (Mcomp = 0.46 M200) or separation (Dcomp = 4.08 R200).

The results of this comparison are shown in Supplementary Table 2. We focused on the incidence of paired simulated systems that match the M31 system’s companion-locked MIF, fMIF, as the main result of this work. The two bins of varying host mass show fMIF consistent within ΔfMIF = 0.09%. A smaller pair separation and higher companion mass do slightly enhance the incidence of M31-like asymmetric systems, but neither can achieve fMIF > 0.5%. This increase in incidence is not recovered to the same extent for cones of maximum asymmetry, suggesting that this effect impacts only the direction of asymmetry (but not its magnitude). We also tested whether adopting stricter analogues of the M31 system (M200 = [1, 2] × 1012 M⊙ and Mcomp = [0.5, 1.5] M200) alleviates its tension with cosmological expectations. This selection in fact reduces fMIF for both companion-locked cones and cones of maximum asymmetry from our fiducial results, but the low sample size of 54 simulated systems across TNG100 and EAGLE renders the results of this comparison unreliable. Finally, we checked whether simulated M31 analogues with more companions more massive than the respective analogue (Nsys = 63) show an enhanced degree of asymmetry. We recover respective incidences of 0.30% and 5.29% for companion-locked cones and cones of maximum asymmetry, a result consistent with sample (i) in Supplementary Table 2. In summary, we found no evidence that adjustments in our selection criteria for simulated M31 analogues would significantly alleviate the reported discrepancy with the observed M31 system.

Impact of survey completeness

The current census of Andromeda satellites is not complete, and the prominent excess of galaxies on the near side of M31 naturally points to incompleteness as a possible factor. Reference 21 calculated detection limits within the PAndAS footprint, reporting that dwarfs brighter than MV = −7.5 should be observable throughout the M31 halo. Of the 37 M31 satellites in ref. 18, 30 lie above this luminosity threshold. Five of the 7 fainter satellites are located on the near side of M31 (and XXVI lies only a few degrees further), and their removal from our working sample is expected to increase the incidence of similarly lopsided systems.

To fully compensate for any possible incompleteness, the ideal approach would be to prepare a sample of simulated Andromeda analogues also with 30 satellites brighter than MV = −7.5. However, TNG100 produces only luminous dwarfs until MV = −9 due to its limited baryonic resolution, and only 15 such paired systems are available in the higher-resolution TNG50 run. While none of these 15 systems match the Andromeda system’s MIF using companion-locked cones, the resulting maximum incidence of fMIF < 6.7% is limited in its use due to it being an order of magnitude higher than our fiducial sample’s fMIF. To obtain meaningful results, we instead assumed that the phase-space distribution of satellites around their host is independent of their exact luminosity function—a simplifying assumption also adopted in most studies quantifying the significance of observed satellite planes in simulations6,13,16,54—and truncated each simulated analogue to its 30 most massive satellites in a manner similar to our fiducial method. In support of this, we point out that fMIF does not differ significantly when binning over the fiducial sample’s range of host (and thus satellite) mass regimes (Supplementary Table 2), and the luminosity function of our selected analogues does not to be an exact match to the M31 system to set a baseline for satellite angular phase-space distributions expected in a ΛCDM context.

Of 411 paired Andromeda analogues and their realizations, 0.5% match the M31 system’s MIF for companion-locked cones—less than a 2-fold increase in incidence from the full satellite sample. This result may be interpreted as the upper bound for the Andromeda system’s incidence, such that 0.3–0.5% of simulated analogues show an equal or more significant asymmetry. When considering cones of maximum asymmetry instead, we recovered a higher fMIF of 8.6%, which represents an increase from the full sample at a similar proportion. However, 74% of these asymmetric analogue realizations reach their MIF at θ < 60°— thus representing a more concentrated cluster of satellites rather than the observed population-wide asymmetry. In the 30-satellite sample, only 0.2% of realizations match both the M31 system’s MIF and the opening angle at which this is achieved.

Compensating for the impact of survey completeness does increase the incidence of sufficiently asymmetric analogues, but incompleteness is not the primary driver of the observed asymmetrical distribution nor the tension it holds with cosmological expectations. Indeed, we point out that the 7 satellites that lie below the completeness threshold show a mean angular separation from the Milky Way–M31 line of sight of 70 ± 8°, a result fully consistent with that of the ‘complete’ 30-satellite sample at 69 ± 9°. The fainter 7 satellites thus show a degree of asymmetry near-identical to the brighter 30, and we found no evidence that incompleteness artificially enhances the observed lopsidedness. Furthermore, a detailed analysis of the satellite system using forward modelling55 rules out the asymmetry (within the PAndAS footprint) as a straightforward consequence of incompleteness alone at >99.9% confidence. We also point out that the analysis in ref. 21 requires only ~80% of the M31 satellites to be located on the hemisphere facing the Milky Way. Explaining the more significant statistic of 36 out of 37 satellites within 106.5° of the Milky Way’s direction using incompleteness alone would be even less feasible.

Data availability

This work makes use of publicly available data products from the IllustrisTNG and EAGLE simulation suites, provided by the IllustrisTNG Collaboration and the Virgo Consortium, respectively. The observational data of the M31 satellite system used in this work are published in ref. 18.

Code availability

The code used to produce this study is not publicly available but can be communicated in response to reasonable requests to the corresponding author.

References

Sales, L. V., Wetzel, A. & Fattahi, A. Baryonic solutions and challenges for cosmological models of dwarf galaxies. Nat. Astron. 6, 897–910 (2022).

Kroupa, P., Theis, C. & Boily, C. M. The great disk of Milky-Way satellites and cosmological sub-structures. Astron. Astrophys. 431, 517–521 (2005).

Pawlowski, M. S., Pflamm-Altenburg, J. & Kroupa, P. The VPOS: a vast polar structure of satellite galaxies, globular clusters and streams around the Milky Way. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 423, 1109–1126 (2012).

Pawlowski, M. S. & Kroupa, P. The Milky Way’s disc of classical satellite galaxies in light of Gaia DR2. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 491, 3042–3059 (2020).

Ibata, R. A. et al. A vast, thin plane of corotating dwarf galaxies orbiting the Andromeda galaxy. Nature 493, 62–65 (2013).

Müller, O. et al. The coherent motion of Cen A dwarf satellite galaxies remains a challenge for ΛCDM cosmology. Astron. Astrophys. 645, L5 (2021).

Chiboucas, K., Jacobs, B. A., Tully, R. B. & Karachentsev, I. D. Confirmation of faint dwarf galaxies in the M81 group. Astron. J. 146, 126 (2013).

Müller, O., Scalera, R., Binggeli, B. & Jerjen, H. The M 101 group complex: new dwarf galaxy candidates and spatial structure. Astron. Astrophys. 602, A119 (2017).

Martínez-Delgado, D. et al. Tracing satellite planes in the Sculptor group. I. Discovery of three faint dwarf galaxies around NGC 253. Astron. Astrophys. 652, A48 (2021).

Ibata, R. A., Famaey, B., Lewis, G. F., Ibata, N. G. & Martin, N. Eppur si muove: positional and kinematic correlations of satellite pairs in the low Z universe. Astrophys. J. 805, 67 (2015).

Heesters, N. et al. Flattened structures of dwarf satellites around massive host galaxies in the MATLAS low-to-moderate density fields. Astron. Astrophys. 654, A161 (2021).

Pawlowski, M. S. et al. The satellite galaxy plane of NGC 4490 in light of ΛCDM. Sparsity of similarly extreme analogs and a possible role of satellite pairs. Astron. Astrophys. 688, A153 (2024).

Ibata, R. A. et al. A thousand shadows of Andromeda: rotating planes of satellites in the Millennium-II cosmological simulation. Astrophys. J. 784, L6 (2014).

Bahl, H. & Baumgardt, H. A comparison of the distribution of satellite galaxies around Andromeda and the results of ΛCDM simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 438, 2916–2923 (2014).

Cautun, M. et al. Planes of satellite galaxies: when exceptions are the rule. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 452, 3838–3852 (2015).

Samuel, J. et al. Planes of satellites around Milky Way/M31-mass galaxies in the FIRE simulations and comparisons with the Local Group. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 504, 1379–1397 (2021).

Sawala, T. et al. The Milky Way’s plane of satellites is consistent with ΛCDM. Nat. Astron. 7, 481–491 (2023).

Savino, A. et al. The Hubble Space Telescope survey of M31 satellite galaxies. I. RR Lyrae-based distances and refined 3D geometric structure. Astrophys. J. 938, 101 (2022).

McConnachie, A. W. & Irwin, M. J. The satellite distribution of M31. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 365, 902–914 (2006).

Conn, A. R. et al. The three-dimensional structure of the M31 satellite system; strong evidence for an inhomogeneous distribution of satellites. Astrophys. J. 766, 120 (2013).

Doliva-Dolinsky, A. et al. The PAndAS view of the Andromeda satellite system. III. Dwarf galaxy detection limits. Astrophys. J. 933, 135 (2022).

Wan, Z., Oliver, W. H., Lewis, G. F., Read, J. I. & Collins, M. L. M. On the origin of the asymmetric dwarf galaxy distribution around Andromeda. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 492, 456–467 (2020).

Libeskind, N. I., Guo, Q., Tempel, E. & Ibata, R. The lopsided distribution of satellite galaxies. Astrophys. J. 830, 121 (2016).

Pawlowski, M. S., Ibata, R. A. & Bullock, J. S. The lopsidedness of satellite galaxy systems in ΛCDM simulations. Astrophys. J. 850, 132 (2017).

Brainerd, T. G. & Samuels, A. Lopsided satellite distributions around isolated host galaxies. Astrophys. J. 898, L15 (2020).

Brainerd, T. G. & Samuels, A. Mean resultant length as a measure of the lopsidedness of satellite galaxy distributions. Res. Notes Am. Astron. Soc. 5, 57 (2021).

Wang, P. et al. The lopsided distribution of satellites of isolated central galaxies. Astrophys. J. 914, 78 (2021).

Fardal, M. A. et al. Inferring the Andromeda galaxy’s mass from its giant southern stream with Bayesian simulation sampling. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 434, 2779–2802 (2013).

Martin, N. F. et al. Lacerta I and Cassiopeia III. Two luminous and distant Andromeda satellite dwarf galaxies found in the 3π Pan-STARRS1 survey. Astrophys. J. 772, 15 (2013).

Martin, N. F. et al. Perseus I: a distant satellite dwarf galaxy of Andromeda. Astrophys. J. 779, L10 (2013).

Zentner, A. R., Kravtsov, A. V., Gnedin, O. Y. & Klypin, A. A. The anisotropic distribution of galactic satellites. Astrophys. J. 629, 219–232 (2005).

Gong, C. C. et al. The origin of lopsided satellite galaxy distribution in galaxy pairs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 488, 3100–3108 (2019).

Springel, V. et al. First results from the IllustrisTNG simulations: matter and galaxy clustering. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 475, 676–698 (2018).

McAlpine, S. et al. The EAGLE simulations of galaxy formation: public release of halo and galaxy catalogues. Astron. Comput. 15, 72–89 (2016).

Garrison-Kimmel, S. et al. Not so lumpy after all: modelling the depletion of dark matter subhaloes by Milky Way-like galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 471, 1709–1727 (2017).

Pawlowski, M. S. et al. Considerations on how to investigate planes of satellite galaxies. Astron. Nachr. 338, 854–861 (2017).

Pawlowski, M. S. Phase-space correlations among systems of satellite galaxies. Galaxies 9, 66 (2021).

Bowden, A., Evans, N. W. & Belokurov, V. On asymmetric distributions of satellite galaxies. Astrophys. J. Lett. 793, L42 (2014).

Hammer, F. et al. Gaia EDR3 proper motions of Milky Way dwarfs. II Velocities, total energy, and angular momentum. Astrophys. J. 922, 93 (2021).

Taibi, S., Pawlowski, M. S., Khoperskov, S., Steinmetz, M. & Libeskind, N. I. A portrait of the vast polar structure as a young phenomenon: hints from its member satellites. Astron. Astrophys. 681, A73 (2024).

Samuels, A. & Brainerd, T. G. Lopsided satellite distributions around isolated host galaxies in a ΛCDM universe. Astrophys. J. 947, 56 (2023).

Habas, R. et al. Newly discovered dwarf galaxies in the MATLAS low-density fields. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 491, 1901–1919 (2020).

Carlsten, S. G., Greene, J. E., Beaton, R. L., Danieli, S. & Greco, J. P. The Exploration of Local VolumE Satellites (ELVES) survey: a nearly volume-limited sample of nearby dwarf satellite systems. Astrophys. J. 933, 47 (2022).

Geha, M. et al. The SAGA survey. I. Satellite galaxy populations around eight Milky Way analogs. Astrophys. J. 847, 4 (2017).

Collins, M. L. M. et al. Pegasus V/Andromeda XXXIV—a newly discovered ultrafaint dwarf galaxy on the outskirts of Andromeda. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 515, L72–L77 (2022).

Karachentsev, I. D., Karachentseva, V. E., Huchtmeier, W. K. & Makarov, D. I. A catalog of neighboring galaxies. Astron. J. 127, 2031–2068 (2004).

Karachentsev, I. D., Makarov, D. I. & Kaisina, E. I. Updated nearby galaxy catalog. Astron. J. 145, 101 (2013).

Planck Collaboration et al. Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 594, A13 (2016).

Planck Collaboration et al. Planck 2013 results. I. Overview of products and scientific results. Astron. Astrophys. 571, A1 (2014).

Tamm, A., Tempel, E., Tenjes, P., Tihhonova, O. & Tuvikene, T. Stellar mass map and dark matter distribution in M31. Astron. Astrophys. 546, A4 (2012).

Yuan, S., Zhu, L., Liu, C., Qu, H. & Fan, Z. Constraining mass of M31 combing kinematics of stars, planetary nebulae and globular clusters. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 22, 085023 (2022).

Bell, E. F., McIntosh, D. H., Katz, N. & Weinberg, M. D. The optical and near-infrared properties of galaxies. I. Luminosity and stellar mass functions. Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser. 149, 289–312 (2003).

Pillepich, A. et al. First results from the TNG50 simulation: the evolution of stellar and gaseous discs across cosmic time. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 490, 3196–3233 (2019).

Pawlowski, M. S. & Tony Sohn, S. On the co-orbitation of satellite galaxies along the Great Plane of Andromeda: NGC 147, NGC 185, and expectations from cosmological simulations. Astrophys. J. 923, 42 (2021).

Doliva-Dolinsky, A. et al. The PAndAS view of the Andromeda satellite system. IV. Global properties. Astrophys. J. 952, 72 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank O. Müller for interesting discussions and helpful inputs. K.J.K. and M.S.P. acknowledge funding via a Leibniz-Junior Research Group (project number J94/2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.J.K. lead the investigation, performed the formal analysis and wrote the initial paper. M.S.P. supervised the design and findings of this work. N.L. contributed to the interpretation of the results and revisions of the methodology. All authors contributed to the writing of the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Astronomy thanks Till Sawala and Zhen Wan for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2, and Tables 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kanehisa, K.J., Pawlowski, M.S. & Libeskind, N. Andromeda’s asymmetric satellite system as a challenge to cold dark matter cosmology. Nat Astron 9, 692–701 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02480-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02480-3