Abstract

The strongly lensed gravitational wave (SLGW) is a promising transient phenomenon. However, the long-wave nature of gravitational waves poses a considerable challenge in the identification of its host galaxy. Here, to tackle this challenge, we propose a method triggered by the wave optics effect of microlensing. The microlensing interference introduces frequency-dependent fluctuations in the waveform. Our method consists of three steps. First, we reconstruct the waveforms by using template-independent and template-dependent methods. The mismatch of two reconstructions serves as an indicator of SLGWs. This step can identify approximately 10% SLGWs. Second, we pair the multiple images of the SLGWs by using sky localization overlapping. Because we have preidentified at least one image through microlensing, the false-alarm probability for pairing SLGWs is significantly reduced. Third, we search the host galaxy by requiring the consistency of time delays between galaxy–galaxy lensing and SLGW. By combing the stage-IV galaxy survey and the third-generation gravitational wave detectors, we expect to find, on average, one quadruple-image system per 3 years. This method can substantially facilitate the pursuit of time-delay cosmography, discovery of compact objects and multimessenger astronomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In the past three observing runs (O1–O3)1,2,3, advanced LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory)4, Virgo (Virgo Gravitational-Wave Detector)5 and KAGRA (Kamioka Gravitational-Wave Detector)6 collaboration has recognized 90 gravitational wave (GW) events, including 86 binary black holes (BBHs), 2 binary neutron stars and 2 neutron star–black hole binaries. In the coming years, LVK (LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA) will continue to improve their sensitivity, and LIGO India7 will join the network in the near future. It is expected that the accumulation of GW events will rapidly increase with the improvement of detector sensitivity. References. 8,9 predicted that the lensing detection rate for these upgraded second-generation (2G) detectors is 0.5–1 yr−1, consistent with current non-detection10,11,12,13,14,15. By contrast, for the third-generation (3G) detectors, such as Einstein Telescope16 and Cosmic Explorer17, the lensing detection rate will increase to 40–103 yr−1, depending on the population properties of the sources and lenses18.

The successful detection of strongly lensed GW (SLGW) events could have important implications for both cosmology and astrophysics. In cosmology, SLGWs offer the potential for more accurate Hubble parameter estimation, thanks to the millisecond-level time-delay measurements. In addition, SLGWs could improve BBH localization precision19,20 and provide a valuable tool for testing general relativity21,22,23. In astrophysics, the characteristic oscillatory behaviour in SLGW waveforms, caused by wave optics effects as the frequency sweeps upwards, could spectralize the microlens’s mass distribution, ranging from intermediate-mass black holes to substellar compact objects. This provides a novel approach to studying faint compact objects in galaxies. Unlike electromagnetic signals, the wavelength of GWs during the BBH merger phase is approximately equal to GM (where G is the gravitational constant and M is the mass of the source), which is comparable to the size of the source, approximately 3GM. This long-wave nature makes the sky localization of GW events much worse than those of the electromagnetic phenomena. In the geometric optics limit, lensing magnification is highly degenerate with the GW’s luminosity distance. It is difficult to use the magnification information to select the possible lensing candidates. Therefore, distinguishing lensing events from a vast unlensed dataset is a formidable challenge. A key issue is to reduce the false-alarm probability (FAP).

Four strategies for identification of SLGWs have been proposed in recent years: parameter overlapping24, machine learning11,25, joint-parameter estimation (joint-PE)13,26,27 and saddle image analysis with high-order modes28,29. The first two strategies exhibit a comparable FAP25. They can identify 10–15% lens pairs with a FAP per pair of 10−5 for 2G detectors. We extrapolate this detection efficiency to 3G detectors. Assuming that there are 100 lens pairs and 105 unlensed events annually, this method could potentially pick out 10–15 lens pair candidates along with 50,000 random pairs that are rejected by the null hypothesis (unlensed hypothesis).

Although we may slightly overestimate FAP, we believe that it is not significantly overestimated. The confidence is rooted in the similarity of uncertainties of sky localization between 2G and 3G detectors. This distribution ranges from 10−2 degrees to 104 degrees (ref. 30), indicating that many random cases with high coincidences will persist. For this reason, Çalışkan et al.31 have argued for the necessity of designing alternative identification criteria beyond parameter overlapping. Recently, two possible avenues for such alternatives have been proposed. The first involves the incorporation of prior knowledge, including time-delay and magnification ratio between lensing image pairs, as advanced identification criteria. The second avenue centres on using a more accurate joint-PE method to enhance identification capabilities. Currently, LVK collaboration has combined this joint-PE method with time-delay priors to determine whether or not an event pair/triplet/quadruplet is strongly lensed10,14,15.

However, both the overlapping and joint-PE methods face challenges in the future GW detection missions. The computational demands are substantial, with a complexity proportional to \({\mathcal{O}}({N}^{2})\), where N represents the number of GW events. Therefore, it is necessary to devise a new, prior-free, low-FAP and computationally efficient method as an independent alternative approach to identify SLGWs. Thanks to the long-wave nature of GWs, microlenses (for example, stars and compact objects) located within the lens galaxies could leave diffraction or interference imprints on GW’s waveform, which could be treated as a smoking gun for strong lensing events. Our strategy is to leverage these inherent features in SLGWs images. Ali et al.32 found that the diffraction induced by a point mass or singular isothermal sphere lens can be identified by using a model-independent method. However, the stochastic nature of the microlensing field poses a formidable challenge in creating a comprehensive template bank, which is capable of effectively filtering these fringes. To address this challenge, we use a template-free approach, known as the coherent wave burst (cWB)33,34, to reconstruct the GW waveform. This method primarily involves analysing the synchronized triggers from multiple detectors during the GW’s propagation from one detector to another. cWB is more suitable for finding the burst signal instead of the long duration one35. Compared with BBH mergers, binary neutron star mergers have longer durations, and neutron star–black hole mergers do not have the chirp behaviour. Hence, in this Article, we focus on the GWs generated by BBH only.

Here, we introduce an interference-based approach for the identification of SLGWs. Our approach involves the detection of SLGWs, searching for pairs of SLGWs and identifying the host galaxies. This methodology effectively addresses the inherent challenges of traditional methods. Consequently, it will enrich the utility of SLGWs in astrophysics and cosmology.

Results

cWB reconstruction

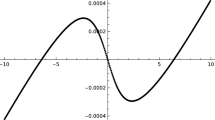

We illustrate our result by simulating an SLGW event generated by a BBH merger, as shown in Fig. 1. We adopt the single-precessing-spin waveform model IMRPhenomPv2 (refs. 36,37) encoded in PyCBC38 and three Cosmic Explorer detectors located at Livingston (USA), Hanford (USA) and Pisa (Italy) to generate the simulated strain data. To illustrate the the interference effect with better visual clarity, the macrolensing magnification of the event in Fig. 1 is chosen as 66 (macrolensing convergence κ ≈ 0.492, macrolensing shear γ ≈ 0.492). Furthermore, we conservatively choose the microlensing convergence as κ* = 0.09, which corresponds to f* ≈ 0.2. This f* value is almost the lower bound suggested by Dobler et al.39. The microlens mass function of the event shown in Fig. 1 differs from the one used throughout the rest of the Article, as it is chosen to be uniformly 1 solar mass for simplicity. The BBH parameters are listed in Table 1.

Top, the blue and red curves represent the reconstruction results of cWB and Bilby, respectively. The black curve is the injected GW waveform. The x axis is the GW frequency, and the y axis is the absolute value of the waveform. Bottom, the blue curve shows the ratio of cWB and Bilby results. The black curve is the injected ratio of the wave optics magnification factor F(f) and the square root of the macromagnification \(\sqrt{\mu }\). In this figure, the macromagnification is set to μ = 66, and the microlensing convergence is set to κ* = 0.09. The BBH parameters used in this figure are provided in Table 1.

As is shown in Fig. 1 (black curve), the microlensing wave optics effect leaves a frequency-dependent imprint on the GW waveform. Currently, while the techniques for searching this feature produced by isolated microlens have matured10,14,32, only a few pioneering works have studied the microlensing field scenario40,41,42. The waveform template of GW intersecting with the stochastic microlensing fields could not be modelled deterministically. Hence, the traditional matched filtering method is no longer suitable for our goal. Fortunately, as shown in Fig. 1, these microlensing imprints can be reconstructed using a template-free method, cWB. The blue curve in the top panel shows the reconstructed GW waveform from cWB. The x axis is the GW frequency, and the y axis is the absolute value of the waveform. The blue curve is consistent with the black one, which is our injected microlensed GW signal. The extra-fast oscillations in the blue curve compared with the black is the unwanted instrumental noise. This result demonstrates the robustness of cWB for reconstructing the microlensing effect. Furthermore, we show the best-fit waveform reconstructed from the template fitting using the template without microlensing in the smoothing red curve. The waveform template used in parameter estimation is IMRPhenomPv2 encoded in Bilby43. The Bilby result is very different from the result of cWB, which indicates that the 15-parameter waveform cannot reconstruct the microlensing wave optics effect at all. The bottom panel shows the ratio between \({\tilde{h}}_{{\rm{cWB}}}\) and \({\tilde{h}}_{{\rm{Bilby}}}\) as the blue curve. By comparing with the injected value, \(F(\,f\,)/\sqrt{\mu }\), it is clear that cWB accurately captures the microlensing effects.

Identification of SLGW signal

In this section, we introduce a new method for the authentication of SLGW events. Specifically, our approach involves the evaluation of mismatch between cWB and Bilby outcomes, serving as a means to ascertain the eligibility of a given event as an SLGW event. One can imagine that the efficiency of this method depends on the quality of the reconstruction results and the strength of the microlensing imprints. To demonstrate the reliability of the above method, we need to know the extent to which unlensed events can mimic the result of lensed events. We randomly select 200 unlensed GWs to construct the false-positive sets (see Methods for details).

The grey-shaded areas in Fig. 2 represent the match result of cWB and Bilby for these false-positive samples. The x axis stands for the matched-filter signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). It is worth mentioning that, when calculating the matching for each event, we randomly select 100 groups of parameter values from the posterior distribution of the Bilby results and match them with the best-fit result of cWB. The envelope of the shaded area is the lower matching bound of all false-positive events. The top and bottom panels stand for results without and with detector frame chirp mass \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{z}=20\,{{\rm{M}}}_{\odot }\) cut, respectively. One can find that the match value is proportional to SNR. This result is expected because, at high SNR, both cWB and Bilby can accurately reconstruct the actual GW waveform with tiny uncertainty. This is consistent with the result from another cWB reconstruction work44. Comparing the two panels demonstrates that \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{z} > 20\,{{\rm{M}}}_{\odot }\) truncation can significantly improve the matching result for events with SNR ∈ (40, 200). We note that setting a cut-off of \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{z}=20\,{{\rm{M}}}_{\odot }\) is cost-effective. It loses only approximately 17% SLGWs but can significantly reduce the FAP.

This figure shows the match between cWB’s maximum likelihood waveform and Bilby’s posterior results, as a function of SNR. The grey-shaded areas delineate the envelope of the lower matching value between the maximum likelihood waveform of cWB and the posterior results from Bilby across all unlensed events (false-positive samples). The black error bars (90% confidence interval) with blue pentagrams (mean value) represent the match results of SLGWs. The graphs show the results without (top) and with (bottom) detector frame chirp mass \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{z}\ge 20\,\rm{{M}}_{\odot }\) cut. Our simulation is conducted by assuming three Cosmic Explorer detectors over 3 years.

Based on our simulation, we expect to detect 510 SLGWs with an SNR greater than 12 over a 3-year period, originating from 256 strong lensing systems. Among these, we estimate that 85 signals exhibit strong microlensing signatures. These events are plotted as the blue pentagrams (mean value) with black error bars (90% confidence interval) in Fig. 2. They are identified by comparing the match between the theoretical input signals with and without microlensing effects. More specifically, we select events where the theoretical match is below 99.5% for signals with SNR <150, and below 99.99% for signals with SNR >150. Because these thresholds closely align with the boundary of the shaded region, we do not expect the remaining 425 events, which exhibit only weak microlensing effects, to be distinguishable. Subsequently, we conduct parameter estimation for each of the 85 events using Bilby and cWB. Among these, 58 are classified as microlensing identifiable events, where the upper error bars do not overlap with the lower boundary of the shaded region. Consequently, we conclude that 27 events are missed due to estimation uncertainties. In summary, our method has the capacity to identify more than 10% (58 out of 510) of SLGWs.

Strong lensing pairing

In the preceding section, we successfully authenticated 58 single-image SLGWs every 3 years. Through an analysis of the sky localization overlapping between these 58 single images and the remaining GWs, we are able to select the multiple-image systems associated with these single images.

Figure 3 shows the results of our multiple-image identification process. We always pair the GWs with the first detected signal among multiple images. Therefore, a double image corresponds to one pair, and a quadruple image corresponds to three pairs. The y axis represents the FAP including the trial factor derived from 105 false positives according to equation (7). The x axis corresponds to the event index. It is worth noting that each of the previously identified 58 images belong to either a new lens system or an old system shared with other identified images. In general, these 58 images are included in 47 strong lensing systems. The divide between differently coloured regions corresponds to FAP = 10−2, 10−4 and 10−6, respectively. The circles in the figure indicate the FAP of a doublet and stars denote the FAP of a quadruplet, which is defined in equation (8). In this Article, we adopt a threshold of FAP <10−2 for doublet and FAP <10−6 for quadruplet. With this choice, two double-image systems and one quadruple-image system were identified, which are marked as solid circles and a solid star, respectively. In particular, for the quadruple event ID-35, its FAP is <10−8, with each image pair having a FAP of <10−2.

This figure displays the results of finding SLGW pairs. The y axis represents the FAP, defined in equation (7) for doublet and equation (8) for quadruplet. The x axis corresponds to the event index. The divide between the differently coloured regions corresponds to FAP = 10−2, 10−4 and 10−6, respectively. The circles and stars indicate the FAP of doublets and quadruplets, respectively. Grey represents FAP >0.01, red represents 10−4 < FAP < 0.01 and purple represents FAP <10−4. We use a successful identification threshold of FAP <10−2 for doublets and FAP <10−6 for quadruplets. Applying these criteria, we identified two double-image systems and one quadruple-image system, which are represented by solid circles and a solid star, respectively.

Host galaxy identification

In the context of quadruple-image systems, the identification of host galaxies can be accomplished through a comparison between the time delays of SLGW and galaxy–galaxy strong lensing (GGSL) events, as detailed by Hannuksela et al.19 For double-image system, it is difficult to pinpoint the host galaxy. Hence, we do not analyse double-image systems at this step. For quadruple-image systems, the BBH must reside in the area of source galaxy, which is overlapped with the caustics. Statistically, the area that can generate the consistent time delay with those from GW shall be proportional to the probability of the source galaxy being the host. Hereafter, we will call this area ‘time-delay area’. Considering the BBH population model, we need to further weight this area according to its star formation rate (SFR).

Figure 4 showcases the host galaxy identification result of quadruple event ID-35 in Fig. 3, acquired using one of the flagship stage-IV galaxy survey, namely China Space Station Telescope (CSST)45 and James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)46. CSST is used to select the GGSL candidates thanks to its wide field of view, and JWST is used for a dedicated follow-up. Among the three purple quadruplets shown in Fig. 3, the host galaxy of the ID-35 event stands out as the brightest (smallest source redshift, zs = 1.6), as demonstrated in Extended Data Fig. 1, and the most accurately localized (1.3 square degrees) one. It is worth noting that the 1.3 square degrees is the sky localization envelope region, rather than the overlapping region, of the multiple GW counterparts. In Extended Data Fig. 2, we show the sky localization result for three quadruplets, highlighted in purple in Fig. 3. Each panel has four counters representing quadruple counterparts. The injected sky location (dashed curve) is safely within the envelope of the sky localization.

This figure displays the results of host galaxy identification. The x axis represents the logarithmic value of the time-delay area, where the time-delay ratio is within 1‰ agreement with those from SLGW. The y axis denotes the event index of the false GGSL. The vertical dashed grey line and the dark-grey circles represent the average areas for true host galaxies and false host galaxies, respectively. Both the light-grey-shaded region and the error bars of the dark-grey circles denote the 1σ confidence intervals.

The x axis of Fig. 4 represents the logarithmic value of the time-delay area. The vertical dashed grey line represents the average area for true host galaxies, while the light-grey-shaded region indicates the uncertainties, which account for variations in both the properties of the host galaxies and the positions of the BBHs within them. We randomly select 40 different host galaxies with different magnitudes, spectral energy distributions and light Sérsic profiles based on a JWST mock catalogue at the same redshift. For each host galaxy, we randomly sample 100 spatial positions to compute the time delays, accounting for the uncertainty in the exact position of the BBH. The dark-grey circles with errors represent the false hosts. Both the shaded region and error bars mark 1σ confidence intervals. To obtain reliable statistics, we included all the GGSL systems (number is 54) that pass the CSST criteria, within 20 square degrees instead of 1.3 square degrees. As been demonstrated previously, the true host galaxy has the largest area. According to our simulation, for event ID-35, the average confidence, as defined in equation (10), under the hypothesis ‘the true host galaxy has the largest area’, is approximately 7.75σ. This means that our method allows us to confidently identify the true host galaxy. We have presented all the essential components of our method. The efficiency of SLGW identification through each step is summarized in Table 2.

Discussion

Aside from false-positive events caused by random noise, another important concern is the potential degeneracy with spin precession. To explore this, we simulated another 200 unlensed signals with precession, where the probability density function of the spin orientation is uniformly distributed in spherical coordinates. As shown in Extended Data Fig. 3, the precession effect affects identification efficiency only at low SNR. Specifically, for SNR <50, the match decreases from 0.97 to 0.95, while for SNR >50, precession has no noticeable effect. After accounting for spin precession, we lose only 2 out of 58 microlensing identifiable events with SNRs below 50.

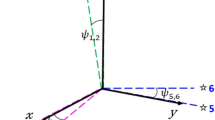

The phenomenological differences between the spin precession effect and the microlensing diffraction imprint are clear: the spin precession effect evolves gradually and smoothly over time, while the microlensing field exhibits more erratic, random fluctuations, particularly at higher frequencies. To substantiate this argument, in Extended Data Fig. 4 we show the waveform of one of the identifiable events from Fig. 2. Its macromagnification is 2.2, the SNR is 179 and the match value is 0.987. The orange curve corresponds to the injected GW waveform, which includes microlensing but excludes precession. The grey and blue curves represent the maximum likelihood reconstruction results from cWB and Bilby, respectively. In Bilby, we choose a precession template, namely IMRPhenomPv2. The first panel displays the waveform in the frequency domain, with the x axis representing the GW frequency and the y axis representing the amplitude. It is evident that the grey curve provides a better fit to the orange curve than the blue one.

The differences between microlensing and precession become more evident when examined in the time domain. The second panel provides a zoomed-in view of the time-domain waveform from the merger phase. One can see that the precession waveform fails to capture certain high-frequency modulations produced by microlensing. The third and fourth panels display the full zoomed-out waveform, starting from 10 Hz. Precession clearly induces low-frequency modulation during the inspiral phase, noticeable after the red vertical line in the third panel. By contrast, microlensing shows no such effect, as evident in the fourth panel. Therefore, precession alone is unable to replicate the interference imprint caused by microlensing. However, this does not mean there is no leakage from microlensing into precession, especially in events with strong microlensing signatures. In Extended Data Fig. 5, we present the posterior distribution of the effective precession spin parameter47, χp, for the same events shown in Extended Data Fig. 4. It is obvious that the distribution deviates from zero, indicating the presence of the precession leakage.

One might question whether the ID-35 quadruple event is indeed a very special occurrence, to the extent that its discovery was purely accidental. To address this issue, we conducted simulations of SLGWs over 30 years. The results are shown in Extended Data Fig. 6. We found that 3 Cosmic Explorer detectors can identify 91 out of 516 signals in quadruple-image systems. These 91 identifiable signals and the total 516 signals are included in 38 and 129 quadruple-image systems, respectively. Extended Data Fig. 7 illustrates the redshift and sky localization of these 38 quadruple-image systems. We found that there are 18 quadruple-image systems below zs < 2.1, with sky localization areas under 5 square degrees. For them, CSST has more than 60% probability to observe its host galaxy. Therefore, the ID-35 event is not a special event by coincidence, and our proposed method is robust for identifying SLGWs and associated host galaxies.

Furthermore, it is important to note that the identification of GGSL associated with SLGW could be even more promising. In this analysis, we choose the space-borne telescopes CSST and JWST for the observation of strong lensing images. Although space-borne telescopes have more accurate angular resolution, their limiting magnitude is lower compared with large ground-based telescopes. This limitation fails to find the fainter events, such as ID-27 and ID-42. To address this challenge, we propose to use large ground-based survey telescopes, such as the Rubin Observatory48,49, to identify GGSL systems. Subsequently, telescopes with smaller fields of view equipped with adaptive optical systems, like the Thirty Meter Telescope50, can be used to conduct precise follow-up observations. The combined use of these instruments can further enhance our ability to identify the host galaxies. In summary, we propose a promising identification method for SLGW and associated host galaxy, triggered by the microlensing wave optics. We have validated that it is robust against all the uncertainties we were concerned about.

Methods

SLGW mock data simulation

To validate the method, we follow refs. 18,24 to generate a mock dataset consisting of both lensed and unlensed data using the Monte-Carlo method. The primary simulation process is as follows.

-

(1)

We sample the BBH redshift from a theoretical BBH merger rate model in which the merger rate is proportional to the SFR with a delay time Δt = 50 Myr between the star and BBH formation. The details can be found in appendix B of Xu et al.18.

-

(2)

For the events picked above, we randomly assign BBH masses (m1, m2), inclination angle (ι), polarization angle (ψ), right ascension angle (α), declination (δ), merger time (tc) and spins (a1, a2) from the following distributions.In the following, p is defined as the probability density function, and U as a uniform distribution.

-

(a)

(m1, m2) ~ power law + peak51. Here, the tilde symbol (~) is used to denote ‘distributed as’.

-

(b)

\(p(\iota )\propto \sin (\iota )\), ι ∈ [0, π].

-

(c)

p(ψ) ∝ U(0, π).

-

(d)

p(α) ∝ U(0, 2π).

-

(e)

\(p(\delta )\propto \cos (\delta )\), δ ∈ [−π/2, π/2].

-

(f)

\(p({t}_{{\mathrm{c}}})\propto {{U}}({t}_{\min },{t}_{\max })\), where \({t}_{\min }\) and \({t}_{\max }\) are the minimum and maximum merger times used in the simulation. Here, we set \({t}_{\max }-{t}_{\min }=3\,{\rm{yr}}\times 80 \%\) (duty cycle).

-

(g)

p(a1) ∝ U(0, 0.99).

-

(h)

p(a2) ∝ U(0, 0.99).

-

(a)

-

(3)

Calculate the multiple-image optical depth τ(zs) for each BBH redshift zs using the singular isothermal sphere optical depth as shown by Haris et al.24. Then, generate a random number uniformly distributed between 0 and 1 for each BBH event. Compare the calculated optical depth τ(zs) with the generated random number for each event. If the optical depth τ(zs) is greater than the random number, classify it as an SLGW event; otherwise, exclude it from the selection.

-

(4)

For the selected SLGW samples, we assume a singular isothermal ellipsoidal (SIE) lens model52 and use Lenstronomy53,54 to solve the lens equation. The velocity dispersion σv and axis ratio q of SIE are generated from the SDSS galaxy population distribution55. Note that ref. 55 has a typo in the axis ratio parameter; we use the corrected form in ref. 56. The sample details for these parameters, lens redshift and source-plane location can be found in appendix A of Haris et al.24.

After accounting for the detector’s selection effect in the provided samples, three Cosmic Explorer detectors, located at Livingston (USA), Hanford (USA) and Pisa (Italy), can potentially observe approximately 3.3 × 105 BBHs and 510 SLGWs (256 strong lensing systems) in 3 years with 80% duty cycle. This result aligns with the findings of Xu et al.18. It is important to note that, in this simulation, we assume that an event will be considered a detection if it possesses a network matched filter SNR ≥12. In addition, it is worth highlighting that, despite using three Cosmic Explorer detectors in this simulation, we calculate the SNR starting from a frequency of 20 Hz, not from 1 Hz, attributed to computational constraints. Therefore, the result is conservative.

Now, our focus shifts to the simulation of microlensing field, following the instructions listed in refs. 57,58,59. In this study, we utilize the Salpeter initial mass function60 and an elliptical Sérsic profile61 to describe the stellar mass function and density associated with each SLGW. Specifically, we set the stellar mass range to be within [0.1, 1.5] solar masses, which aligns with the value used by Diego et al.62. In addition to the stellar mass component, we also consider the presence of remnant objects in the microlensing field. For this purpose, we adopt the initial–final relation from Spera et al.63. The remnant mass density has been set at 10% of the stellar mass density42.

To determine the frequency-dependent magnification, we use the algorithm introduced by Shan et al.59 to evaluate the Fresnel–Kirchhoff diffraction integral64

where F(ω, y) is the wave optics magnification factor, G is the gravitational constant. ω and y are the circular frequency of the GW and its position in the source plane in the unit of the Einstein radius, respectively. ML and zL are the lens mass and redshift, x is the lens plane coordinate and t(x, y) is the time-delay function defined as

where k = 4GMmicro(1 + zL)/c3 and xi is the coordinate of the ith microlens. The parameter Mmicro represents the average microlensing mass. It is set to 1 solar mass in Fig. 1 and 0.35 solar mass in the rest of the Article.

Here, we set the macro image point as the coordinate origin (y = 0). ϕ−(x) is the contribution from a negative mass sheet (we use the underscore to denote ‘negative’ value) that is used to cancel out the mass contribution from microlenses and keep the total convergence κ unchanged57,58,65. ts(κ, γ, x) represents the macrolens time delay and tm(x, xi) indicates the microlens time delay. Up to this step, we have successfully generated all the essential components for the GW mock data, encompassing both unlensed GWs and SLGWs with microlensing effects.

SLGW finder and pairing

The mismatch between cWB and Bilby serves as a mean to find SLGWs. Here, we define the match equation as

where \({\tilde{h}}_{{\rm{cWB}}}\) and \({\tilde{h}}_{{\rm{Bilby}}}\) are the reconstructed waveforms in the frequency domain. \(\left\langle .| .\right\rangle\) stands for the noise-weighted inner product and is defined as

where ∣.∣ refers to the absolute value, and Sn(f) is the single-side power spectral density of the detector noise. It is evident that equation (3) is ≤1, and the equality holds if and only if \({\tilde{h}}_{{\rm{cWB}}}={\tilde{h}}_{{\rm{Bilby}}}\).

We search for SLGW multiple-image pairs based on the parameter overlapping degree between two GW events. To do this, we utilize the ‘overlapping’ method introduced by Haris et al.24.

where θ represents the GW parameter, and d1 and d2 denote the strain data for event 1 and event 2, respectively. P(θ) corresponds to the prior distribution, and \(P\left({{\uptheta }}| {d}_{1}({d}_{2})\right)\) represents the posterior distribution. In this calculation, we consider only two parameters: right ascension and declination. This choice is motivated by the fact that the presence of the microlensing effect does not introduce significant bias on these two parameters.

To demonstrate the identification accuracy of the pairing method, it is crucial to assess the FAP. First, we define the FAP per pair as

The numerator is the number of false positives. The Bayes factor of these false positives \({\mathcal{B}}\) are higher than the Bayes factor of SLGW image pair \({{\mathcal{B}}}_{{\rm{L}}}\). The denominator is the total number of randomly matched unlensed pairs and unlens–lens pairs. For doublet, the FAP after including the trial factor is defined as31

It depends exponentially on the number of pairs. In our method, Nperyear represents the number of detectable GWs per year. For 3G GW detectors, we select Nperyear = 105. By contrast, without utilizing microlensing information, the exponential term becomes \({N}_{{\rm{UU}}+{\rm{UL}}}\approx {N}_{{\rm{per}}\,{\rm{year}}}^{2}\). Therefore, one can conclude that our method significantly reduces the FAP.

To estimate the FAP of a quadruplet, we simply take the product of the FAPs of three individual doublets

This estimator offers a computationally simple and mathematically conservative way to calculate the FAP for a quadruplet. It is based on the overlap between the individual doublets within the quadruplet, rather than requiring all four images to overlap simultaneously. This condition is less stringent, making our result more conservative.

GGSL simulation and host galaxy identification

In this section, we introduce our host galaxy identification method for SLGWs. We first generate a mock dataset for GGSL by utilizing a JWST mock catalogue known as JAGUAR66. For the false GGSL systems, we use the optical depth method, which is identical to the one used for generating SLGWs, to simulate GGSL events across a 20-square-degree region. We find that there are roughly 3,300 GGSL systems with Einstein radius θE > 0.2″ in 1 square degree. This number is consistent with the simulation result of the CSST strong lensing group. Subsequently, we randomly select lens galaxy magnitudes and light Sérsic radius. Note that there is a typographical error in the work of Goldstein et al.67, so we utilize the corrected formula provided by Wempe et al.68. using the fundamental plane67. For the host galaxy, we collect the galaxy properties, such as spectral energy distribution and light Sérsic profile, via a thin shell [zs − Δzs, zs + Δzs], where zs is the real host galaxy redshift and the shell width is chosen as Δzs = 0.01. The true host galaxy property parameter is assigned according to the above samples. We then rank the host probability on the basis of the SFR of each sample over the past 50 Myr.

To find the host galaxies, we propose a targeted observation strategy. First, we conduct an ordinary survey (600 s exposure time) utilizing the CSST, which has a field of view around 1.1 square degrees. The primary objective of this step is to systematically scan the sky localization envelope of multiple-image SLGWs and subsequently select the GGSL systems that are observable. Here, we use two criteria to assess the observability of GGSL systems: MAB < 26, and \({\theta }_{{\rm{E}}}^{2} > {r}_{s}^{2}+{(s/2)}^{2}\), where θE represents the Einstein radius, s denotes the seeing (for CSST s = 0.135″) and rs stands for the unlensed source size. The second criterion denotes the requirement of being able to distinguish multiple images in the GGSL system.

Subsequently, we propose to use JWST, which has a larger aperture than CSST, for dedicated follow-up observations for each of the targeted GGSLs. We propose a 1,000-s exposure for each of the targets. According to the JWST Exposure Time Calculator (https://jwst.etc.stsci.edu), an exposure time of 1,000 s yields an SNR >33 for a point source with magnitude <26 (ref. 69) in F200W band. The choice ensures the quality of lens image reconstruction. This strategy is cost-effective because CSST observation will select only around three quadruple-image GGSLs per square degree. Hence, the subsequent JWST observations time is about 1 h in total for three candidates.

In Extended Data Fig. 1, we show the probability distribution of host galaxy apparent magnitudes for the three quadruplets. The host galaxy number density is weighted by the SFR according to the BBH population model. In this figure, the red histogram is the apparent magnitude distribution for the CSST r band, and the blue histogram is the one for the JWST F200W band. The difference between the red and blue results only from the filters and spectral energy distribution (SED) and has nothing to do with the telescope aperture and exposure time. It is worth noting that our current analysis assumes only a single photometry band; it is certain that multiband analysis will improve the current results. The grey-shaded region indicates events that cannot be observed by CSST owing to its limited magnitude (assuming a CSST limiting magnitude of MAB = 26). From this figure, it is clear that, for event ID-35, there is a remarkably high probability (approximately 80%) of being able to observe its host galaxy by CSST.

To identify host galaxies, we need to determine the consistency of time delays between GGSL and SLGW measurements. For quadruple-image systems, the estimator consists of two independent components: Δt1,2/Δt1,3 and Δt1,2/Δt1,4. Here, Δt1,2 represents the time delay between image 1 and image 2 (with Δt1,3 and Δt1,4 having similar meanings). In detail, the estimator is defined as

AGGSL(x)∣SLGW represents the area (in unit of kpc2) in the source galaxy, in which each of the pixels can generate the time-delay ratio agreeing with those from SLGW within 1‰ precision. We also tested the convergence of the result by using the precision of 10−4. Below 10−4, we can not resolve single pixel in our simulated lensing image anymore. Furthermore, we require the absolute time delay between image 1 and image 2 to be consistent with those from GWs in the range of (\(\frac{67.74}{60}\Delta {t}_{1,2}^{{\rm{GW}}},\frac{67.74}{80}\Delta {t}_{1,2}^{{\rm{GW}}}\)), where \(\Delta {t}_{1,2}^{{\rm{GW}}}\) is the GW’s time delay between image 1 and image 2. The numerical factor preceding \(\Delta {t}_{1,2}^{{\rm{GW}}}\) accounts for the uncertainty in the Hubble parameter, which lies between 60 and 80 km s−1 Mpc−1. Our fiducial Hubble paremeter value is 67.74 km s−1 Mpc−1. It is evident that the larger this area is, the greater the probability of this galaxy to be the true host.

To incorporate with the BBH population model, we weight the pixels by their SFR (WSFR). Supplementary Fig. 9 shows the relative positions of the host galaxy and caustic for one of the SLGW systems. The red curve represents the caustic of a lens galaxy, while the elliptical region indicates the half-light radius of a source galaxy, with the colour (from blue to yellow) representing the source light flux (from weak to strong) distribution. The shaded region represents the quadruple-image region in the source galaxy.

The confidence of the hypothesis ‘the true host galaxy has the largest area’ against the simulation data is defined as

where Acon,host and Acon,i are the time-delay area for hosts and false hosts, respectively, defined in equation (9). The angle bracket denotes the average over 40 realizations. The term \(\frac{1}{N}{\Sigma }_{i}^{N}\) represents the average over all false hosts, where i denotes the ith false host and N is the total number of false hosts. This formula represents the theoretical average confidence level of the hypothesis ‘the true host galaxy has the largest area’.

Up to this point, we have introduced all the simulation procedures and methods. To provide a clearer representation, we illustrate the main steps of our methodology in Supplementary Fig. 10.

Data availability

The simulated microlensing data are publicly available via the Beijing Normal University (BNU) cloud at https://pan.bnu.edu.cn/l/X1QPKG. Other datasets are available via GitHub at https://github.com/xkshan97/Micro_Interference4SLGW_identification.git.

Code availability

The code that supports the findings of this study is available via GitHub at https://github.com/xkshan97/Micro_Interference4SLGW_identification.git.

References

Abbott, B. et al. GWTC-1: a gravitational-wave transient catalog of compact binary mergers observed by LIGO and Virgo during the first and second observing runs. Phys. Rev. X 9, 031040 (2019).

Abbott, R. et al. GWTC-2: compact binary coalescences observed by LIGO and Virgo during the first half of the third observing run. Phys. Rev. X 11, 021053 (2021).

Abbott, R. et al. GWTC-3: compact binary coalescences observed by LIGO and Virgo during the second part of the third observing run. Phys. Rev. X 13, 041039 (2023).

Aasi, J. et al. Advanced LIGO. Classical Quant. Grav. 32, 074001 (2015).

Acernese, F. et al. Advanced Virgo: a second-generation interferometric gravitational wave detector. Classical Quant. Grav. 32, 024001 (2014).

Akutsu, T. et al. KAGRA: 2.5 generation interferometric gravitational wave detector. Nat. Astron. 3, 35–40 (2019).

Unnikrishnan, C. S. IndIGO and LIGO-India: scope and plans for gravitational wave research and precision metrology in India. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 22, 1341010 (2013).

Li, S.-S., Mao, S., Zhao, Y. & Lu, Y. Gravitational lensing of gravitational waves: a statistical perspective. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 476, 2220–2229 (2018).

Oguri, M. Effect of gravitational lensing on the distribution of gravitational waves from distant binary black hole mergers. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 480, 3842–3855 (2018).

Hannuksela, O. A. et al. Search for gravitational lensing signatures in LIGO–Virgo binary black hole events. Astrophys. J. Lett. 874, L2 (2019).

Kim, K., Lee, J., Yuen, R. S. H., Hannuksela, O. A. & Li, T. G. F. Identification of lensed gravitational waves with deep learning. Astrophys. J. 915, 119 (2021).

McIsaac, C. et al. Search for strongly lensed counterpart images of binary black hole mergers in the first two LIGO observing runs. Phys. Rev. D 102, 084031 (2020).

Liu, X., Magana Hernandez, I. & Creighton, J. Identifying strong gravitational-wave lensing during the second observing run of Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo. Astrophys. J. 908, 97 (2021).

Abbott, R. et al. Search for lensing signatures in the gravitational-wave observations from the first half of LIGO–Virgo’s third observing run. Astrophys. J. 923, 14 (2021).

Abbott, R. et al. Search for gravitational-lensing signatures in the full third observing run of the LIGO–Virgo network. Astrophys. J. 970, 2 (2024).

Punturo, M., Lück, H. & Beker, M. in Astrophysics and Space Science Library (ed. Bassan, M.) Vol. 404, 333 (Springer, 2014).

Abbott, B. P. et al. Exploring the sensitivity of next generation gravitational wave detectors. Classical Quant. Grav. 34, 044001 (2017).

Xu, F., Ezquiaga, J. M. & Holz, D. E. Please repeat: strong lensing of gravitational waves as a probe of compact binary and galaxy populations. Astrophys. J. 929, 9 (2022).

Hannuksela, O. A., Collett, T. E., Çalışkan, M. & Li, T. G. F. Localizing merging black holes with sub-arcsecond precision using gravitational-wave lensing. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 498, 3395–3402 (2020).

Yu, H., Zhang, P. & Wang, F.-Y. Strong lensing as a giant telescope to localize the host galaxy of gravitational wave event. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 497, 204–209 (2020).

Baker, T. & Trodden, M. Multimessenger time delays from lensed gravitational waves. Phys. Rev. D 95, 063512 (2017).

Collett, T. E. & Bacon, D. Testing the speed of gravitational waves over cosmological distances with strong gravitational lensing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 091101 (2017).

Fan, X.-L., Liao, K., Biesiada, M., Piorkowska-Kurpas, A. & Zhu, Z.-H. Speed of gravitational waves from strongly lensed gravitational waves and electromagnetic signals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 091102 (2017).

Haris, K., Mehta, A. K., Kumar, S., Venumadhav, T. & Ajith, P. Identifying strongly lensed gravitational wave signals from binary black hole mergers. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1807.07062 (2018).

Goyal, S., Kapadia, S. J. & Ajith, P. Rapid identification of strongly lensed gravitational-wave events with machine learning. Phys. Rev. D 104, 124057 (2021).

Lo, R. K. L. & Magaña Hernandez, I. Bayesian statistical framework for identifying strongly-lensed gravitational-wave signals. Phys. Rev. D 107, 123015 (2023).

Janquart, J., Hannuksela, O. A., Haris, K. & Van Den Broeck, C. A fast and precise methodology to search for and analyse strongly lensed gravitational-wave events. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 506, 5430–5438 (2021).

Dai, L. & Venumadhav, T. On the waveforms of gravitationally lensed gravitational waves. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1702.04724 (2017).

Wang, Y., Lo, R. K. L., Li, A. K. Y. & Chen, Y. Identifying type II strongly lensed gravitational-wave images in third-generation gravitational-wave detectors. Phys. Rev. D 103, 104055 (2021).

Vitale, S. & Evans, M. Parameter estimation for binary black holes with networks of third-generation gravitational-wave detectors. Phys. Rev. D 95, 064052 (2017).

Çalışkan, M., Ezquiaga, J. M., Hannuksela, O. A. & Holz, D. E. Lensing or luck? False alarm probabilities for gravitational lensing of gravitational waves. Phys. Rev. D 107, 063023 (2022).

Ali, S., Stoikos, E., Meade, E., Kesden, M. & King, L. Detectability of strongly lensed gravitational waves using model-independent image parameters. Phys. Rev. D 107, 103023 (2023).

Klimenko, S. et al. cwb pipeline library: 6.4.0. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4419902 (2021).

Klimenko, S. et al. Method for detection and reconstruction of gravitational wave transients with networks of advanced detectors. Phys. Rev. D 93, 042004 (2016).

Relton, P. et al. Addressing the challenges of detecting time-overlapping compact binary coalescences. Phys. Rev. D 106, 104045 (2022).

Hannam, M. et al. Simple model of complete precessing black-hole-binary gravitational waveforms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 151101 (2014).

LALSuite: LIGO Scientific Collaboration Algorithm Library Suite record ascl:2012.021 2012.021 (Astrophysics Source Code Library, 2020).

Nitz, A. et al. gwastro/pycbc: v2.0.2 release of pycbc. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6324278 (2022).

Dobler, G. & Keeton, C. R. Microlensing of lensed supernovae. Astrophys. J. 653, 1391–1399 (2006).

Diego, J. M. et al. Observational signatures of microlensing in gravitational waves at LIGO/Virgo frequencies. Astron. Astrophys. 627, A130 (2019).

Mishra, A., Meena, A. K., More, A., Bose, S. & Bagla, J. S. Gravitational lensing of gravitational waves: effect of microlens population in lensing galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 508, 4869–4886 (2021).

Meena, A. K., Mishra, A., More, A., Bose, S. & Bagla, J. S. Gravitational lensing of gravitational waves: probability of microlensing in galaxy-scale lens population. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 517, 872–884 (2022).

Ashton, G. et al. BILBY: a user-friendly Bayesian inference library for gravitational-wave astronomy. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 241, 27 (2019).

Bini, S. et al. Search for hyperbolic encounters of compact objects in the third LIGO–Virgo-KAGRA observing run. Phys. Rev. D 109, 042009 (2024).

Zhan, H. Consideration for a large-scale multi-color imaging and slitless spectroscopy survey on the Chinese space station and its application in dark energy research. Sci. Sin. Phys. Mech. Astron. 41, 1441 (2011).

Gardner, J. P. et al. The James Webb Space Telescope. Space Sci. Rev. 123, 485 (2006).

Schmidt, P., Ohme, F. & Hannam, M. Towards models of gravitational waveforms from generic binaries: II. Modelling precession effects with a single effective precession parameter. Phys. Rev. D 91, 024043 (2015).

Abell, P. A. et al. LSST Science Book, Version 2.0. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.0912.0201 (2009).

Smith, G. P., Robertson, A., Bianconi, M. & Jauzac, M. Discovery of strongly-lensed gravitational waves—implications for the LSST observing strategy. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.05140 (2019).

Skidmore, W. et al. Thirty meter telescope detailed science case: 2015. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 15, 1945–2140 (2015).

Abbott, B. P. et al. Binary black hole population properties inferred from the first and second observing runs of Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo. Astrophys. J. Lett. 882, L24 (2019).

Kormann, R., Schneider, P. & Bartelmann, M. Isothermal elliptical gravitational lens models. Astron. Astrophys. 284, 285–299 (1994).

Birrer, S. & Amara, A. lenstronomy: multi-purpose gravitational lens modelling software package. Phys. Dark Univ. 22, 189–201 (2018).

Birrer, S. et al. lenstronomy II: a gravitational lensing software ecosystem. J. Open Source Softw. 6, 3283 (2021).

Collett, T. E. The population of galaxy–galaxy strong lenses in forthcoming optical imaging surveys. Astrophys. J. 811, 20 (2015).

Wierda, A. R. A. C., Wempe, E., Hannuksela, O. A., Koopmans, Le. V. E. & Van Den Broeck, C. Beyond the detector horizon: forecasting gravitational-wave strong lensing. Astrophys. J. 921, 154 (2021).

Chen, X., Shu, Y., Li, G. & Zheng, W. FRBs lensed by point masses. II. The multipeaked FRBs from the point view of microlensing. Astrophys. J. 923, 117 (2021).

Zheng, W., Chen, X., Li, G. & Chen, H.-z. An improved GPU-based ray-shooting code for gravitational microlensing. Astrophys. J. 931, 114 (2022).

Shan, X., Li, G., Chen, X., Zheng, W. & Zhao, W. Wave effect of gravitational waves intersected with a microlens field: a new algorithm and supplementary study. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 66, 239511 (2023).

Salpeter, E. E. The luminosity function and stellar evolution. Astrophys. J. 121, 161 (1955).

Vernardos, G. Microlensing flux ratio predictions for euclid. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 483, 5583–5594 (2018).

Diego, J. M. et al. Microlensing and the type Ia supernova iPTF16geu. Astron. Astrophys. 662, A34 (2022).

Spera, M., Mapelli, M. & Bressan, A. The mass spectrum of compact remnants from the PARSEC stellar evolution tracks. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 451, 4086–4103 (2015).

Schneider, P., Ehlers, J. & Falco, E. E. Gravitational Lenses (Springer, 1992).

Wambsganss, J. Gravitational Microlensing. PhD thesis, Munich Univ. (1990).

Williams, C. C. et al. The JWST extragalactic mock catalog: modeling galaxy populations from the UV through the near-IR over 13 billion years of cosmic history. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 236, 33 (2018).

Goldstein, D. A., Nugent, P. E. & Goobar, A. Rates and properties of supernovae strongly gravitationally lensed by elliptical galaxies in time-domain imaging surveys. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 243, 6 (2019).

Wempe, E., Koopmans, L. V. E., Wierda, A. R. A. C., Hannuksela, O. A. & Broeck, C. V. D. A lensing multi-messenger channel: combining LIGO–Virgo–KAGRA lensed gravitational-wave measurements with Euclid observations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 530, 3368–3390 (2022).

Pickering, T. E. et al. in Observatory Operations: Strategies, Processes, and Systems VI (eds Peck, A. B. et al.) page 991016 (SPIE, 2016).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by the National Key R&D Program of China grants 2021YFC2203001, 2020YFC2201502 and 2021YFA0718304 and in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grants 11821505, 11991052 and 12235019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors provided ideas throughout the project and comments on the manuscript. X.S. contributed in calculating and writing the draft. B.H. contributed in proposing the idea and writing the draft. X.C. contributed in generating the microlensing fields. R.-G.C. contributed in proposing the idea and writing the draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Astronomy thanks Jose Diego, K. Haris and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Probability distribution function of host galaxy magnitude.

This figure presents the host galaxy apparent magnitude distribution for the three quadruple-image SLGWs identified in Main Fig. 3. The red histogram is the apparent magnitude distribution for CSST r band, and the blue histogram is the one for JWST F200W band. The difference between the red and blue only results from the filters and SED, nothing to do with the telescope aperture and exposure time. The grey shaded region stands for the magnitude greater than 26 where the host galaxy cannot be observed by using the CSST main survey.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Sky localization of three identified quadruple-image SLGWs.

This figure displays the sky localization of the three high-confidence quadruple-image SLGWs. The titles in three corner figures stand for event indices in Main Fig. 3.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Identification efficiency test in the presence of precession effects.

This figure shows the match between the maximum likelihood waveform from cWB and the posterior results from Bilby, as a function of GW SNR. The light grey (dark grey) shaded area represents the lowest match values between cWB and Bilby for unlensed events with (without) precession effects. The blue pentagrams (indicating the mean value) with black error bars (representing the 90% confidence interval) depict the match results for SLGWs. This plot employs a cut-off at a detector-frame chirp mass of \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{z}\ge 20M\odot\).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Waveform comparison.

This figure illustrates the waveform of a typical microlensing event, displayed in both the time and frequency domains. The orange curve corresponds to the injected GW waveform with microlensing but without precession. The grey and blue curves represent the maximum likelihood reconstruction results from cWB and Bilby, respectively. The first panel displays the waveform in the frequency domain, with the x-axis representing the GW frequency and the y-axis representing the amplitude. The \({\mathcal{M}}\) values in the legend represent the match between the reconstructed waveform and the injected waveform. The second panel provides a zoomed-in view of the waveform in the time domain. The third and fourth panels show the complete waveform starting from 10 Hz.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Spin precession leakage from microlensing.

This figure shows the posterior distribution for χp, the effective precession spin parameter for one of the representative microlensing identifiable event in Step-1.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Identification of quadruple-image SLGWs in 30 years.

This figure shows the match between cWB’s maximum likelihood waveform and Bilby’s posterior results, as a function of SNR for quadruple-image systems. The shaded areas in grey delineate the envelope of the lower matching value between the maximum likelihood waveform of cWB and the posterior results from Bilby across all unlensed events (false positive samples). The black error bars (representing the 90% confidence interval) along with the blue pentagrams (indicating the mean value) represent the match results of SLGWs. This plot employs a cut-off of detector frame chirp mass \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{z}\ge 20M\odot\).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Redshift and sky area distributions for identifiable quadruple-image events in 30 years.

The vertical dashed black curve indicates the redshift threshold at zs = 2.1, where the host galaxy is more than 60% likely to have a magnitude less than 26. The horizontal black dashed line represents the maximum sky localization area of 5 square degrees.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–10, discussion and Table 1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shan, X., Hu, B., Chen, X. et al. An interference-based method for the detection of strongly lensed gravitational waves. Nat Astron 9, 916–924 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02519-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02519-5