Abstract

Observational constraints on the configuration of the black hole (BH)–accretion disk–jet system are crucial to understanding BH spin, accretion disk physics and jet formation. The recently reported variation in the position angle of the M87 jet provides a new avenue for exploring these long-standing issues. The observed ~11-year periodicity, spanning over two cycles, is consistent with the Lense–Thirring precession of a compact, tilted accretion disk. However, how such a compact region decouples from the larger-scale accretion flow remains an open question in current numerical simulations. The jet precession challenges the traditional view of a strictly collimated jet by revealing a subtle curvature in the inner regions of the jet that dynamically links the jet to the spinning BH and successfully accounts for its unexpectedly wide inner projected profile. Although continued long-term observations are needed to distinguish coherent precession from stochastic fluctuations in the disk or jet orientation, these results open a new window for probing BH systems through coordinated multiscale observations and follow-on theoretical models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In 1918, the nearby radio galaxy M87 was the first observation of an astrophysical jet1. Despite extensive studies, several fundamental aspects of its central engine remain uncertain. Although the supermassive black hole (SMBH) at the core of M87 is known to accrete at a low rate through a geometrically thick, radiatively inefficient accretion flow2,3,4,5, the exact structure, size and orientation of the accretion disk are poorly constrained by current observations. Additionally, determining the spin of the SMBH in M87 has proven challenging. Traditional techniques like X-ray reflection spectroscopy6,7 and thermal continuum fitting8,9 are limited by the thick geometry and low accretion rate of the disk, making them unsuitable for M87. The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) has revolutionized our understanding of M87’s SMBH by capturing the first direct image of photon orbits at 230 GHz. This breakthrough provides robust constraints on the mass of the SMBH10,11 and offers unprecedented insights into the immediate vicinity of the event horizon. Beyond the mass determination, the EHT findings also excluded models with zero spin for the SMBH, as they failed to account for the observed jet power4. As relativistic jets in active galactic nuclei are intrinsically linked to the SMBH and the surrounding accretion disk12,13, probing the inner regions of the black hole (BH)–disk–jet system is essential for increasing our understanding of the physical conditions and relativistic effects at play near SMBHs. M87, renowned for its powerful active galactic nucleus with an extended relativistic jet, provides an ideal laboratory for this topic (see ref. 14 and references therein).

Recent high-resolution observations of the M87 jet at milliarcsecond and sub-milliarcsecond scales have provided crucial new insights into the above challenges15,16. Notably, Cui et al. identified a periodic variation in position angle with a cycle of approximately 11 years, which has been interpreted as Lense–Thirring (LT) precession due to a tilted accretion disk16. LT precession, a relativistic effect caused by frame-dragging near a spinning SMBH17, offers a unique opportunity to infer the properties of the BH–disk–jet system that are otherwise difficult to measure directly. In this work, we demonstrate that the observed jet precession provides stringent constraints on the SMBH spin and accretion disk parameters. In addition, the precession implies that the jet is not perfectly collimated, particularly in regions close to the central SMBH, which addresses the discrepancy in the projected jet width between the observations and simulations reported by ref. 15 without needing an unexpected emission component outside the Blandford–Znajek mechanism12.

The SMBH spin and accretion disk size

Owing to computational cost and technical issues, comprehensive numerical studies of tilted and geometrically thick accretion disks were not possible until recently18,19. The main body of the disk in M87 undergoes LT precession18,19, and the jet follows the disk and precesses with the same period16,20. The precession period can be calculated by

where we have taken into account the sense of the accretion flow orbit concerning the central SMBH spin and the higher-order corrections21,22 (Methods). In the above, a ≡ Jc/GM2 ∈ [−1, 1] is a dimensionless spin parameter. A positive (negative) value of a corresponds to a prograde (retrograde) disk. M is the SMBH mass, rg = GM/c2 is the gravitational radius, J is the spin angular momentum, G is the gravitational constant, c is the speed of light and rLT is an effective radius that depends on the mass distribution of the part of the disk that exhibits a coherent precession (denoted as the ‘precessing disk’). For M87, the reported precession period Tprec = 11.24 ± 0.47 years (ref. 16) and the SMBH mass MM87 = (6.5 ± 0.7) × 109 M⊙ (where M⊙ is the solar mass)10 put a constraint on the a–rLT space, which is shown in Fig. 1.

The solid curves were calculated from the observed jet precession period and SMBH mass (equation (1)). The lightly shaded region indicates the 1σ confidence interval, which was propagated from the uncertainties in both the precession period and SMBH mass. The green shaded region is excluded based on the conservative requirement that rLT > rISCO.

The relatively short precession period puts a tight constraint on the size of the precessing disk and requires rLT ≤ 14.1 ± 0.6rg for the prograde case and rLT ≤ 16.1 ± 0.6rg for the retrograde case. Equality corresponds to maximum rotation, that is a = 1 or a = −1. For the same ∣a∣, the required rLT is somewhat smaller for a prograde disk compared to a retrograde disk. A smaller ∣a∣ requires a smaller rLT for both the prograde and retrograde cases. Thus, the precessing disk is constrained to be rather compact in the sense that the effective LT radius is, at most, around 15rg.

The constraint on a is highly sensitive to rLT. Assuming rLT > rISCO, where rISCO is the innermost stable circular orbit23, we establish a lower limit a ≳ 0.06 (ref. 16). This result is consistent with that given in ref. 24 despite the difference in the jet–disk co-precessing scenario (Methods). Although it provides a weak constraint on the value of a, the non-spinning scenario is successfully excluded, consistent with the findings of ref. 4.

Considering the extended size of the precessing disk, the assumption rLT > rISCO is highly conservative. To analyse the structure of the precessing disk, we follow refs. 19,25 and adopt a power-law surface density profile with σ(r) ∝ r−ζ. A positive (negative) ζ represents a disk that is more concentrative inwards (outwards), and ζ = 0 represents a constant surface density. The inner and outer radii of the precessing disk are denoted by rin and ro, respectively. These two characteristic radii provide an effective description of the overall extent of the precessing disk. With these settings, the effective LT radius is expressed as (ref. 19 and Methods)

It is justified to assume rin > rISCO, which sets a lower limit of a for a given ro and profile index ζ. In addition, rin < ro is geometrically required, which sets an upper limit of a for a given ro. Taking Tprec = 11.24 years (ref. 16) and MM87 = 6.5 × 109 M⊙ (ref. 10), the resultant constraints on the a–ro space, capturing rISCO < rin < ro, are shown by the shaded areas in Fig. 2. These constraints are presented for three selected values of ζ, with different senses of the disk orbit considered separately.

The upper (lower) panels are for prograde (retrograde) disks. A larger profile index ζ represents a disk that is more concentrated inwards. The shaded areas enclose the allowed region where rISCO < rin < ro. The red curves represent the cases where rin = 6rg, which was motivated by the finding from the simulations that the inner radius for prograde tilted disks is insensitive to the BH spin26 for a weakly magnetized disk. The red curves serve as a guiding and limiting case.

General-relativistic magnetohydrodynamic simulations indicate that the disk surface density is nearly constant (ζ = 0)19, which we denote as the fiducial case. For this scenario, the maximum outer radius is ~42rg (25rg) for a prograde (retrograde) disk, further indicating that the precessing disk is rather compact. The size constraint is sensitive to the profile index ζ. In general, a larger ζ allows a larger outer radius because a mass profile that is more concentrated inwards permits a larger ro to achieve the same rLT. For a fairly inward-concentrated and prograde disk with ζ = 1, the outer radius could be up to ~194rg for a maximally spinning SMBH.

For aligned accretion disks, prograde cases generally lead to a larger precessing disk compared to retrograde cases because rISCO is smaller, allowing rin to be smaller. For tilted accretion disks, this may not be true. Simulations showed that rin was nearly independent of the spin for a modest tilt in a prograde case26 with a weak magnetic field. This indicates that, even for a rapidly spinning BH, rin might not shrink with rISCO and the tight constraint on the outer radius might not be relaxed. Although similar studies are not yet available for moderate or strong magnetic fields, we consider this scenario as both a guiding and limiting case. We illustrate the cases with rin = 6rg by the red curves in the upper panels of Fig. 2. Even though retrograde disks have not been simulated, it is reasonable to assume that rin > rISCO still holds. Therefore, the conclusion that rin is nearly constant might not apply to retrograde disks.

A spinning SMBH induces an asymmetric shape in the BH ring4,27 and creates a distinctive rotational pattern in the polarization map28,29. Future EHT observations with next-generation upgrades27 that resolve these features will be essential for placing stringent constraints on the spin of the SMBH30 and breaking the spin–disk size degeneracy described above.

Jet structure and inner jet width

The second important implication concerns the structure of the jet and the opening angle near the BH. The observed periodic variations in the position angle of the M87 jet challenge the traditional view of it being strictly collimated and reveal a jet precession around the central spin axis of the SMBH16. The inferred precession angle reflects the angle between the SMBH spin and the tangential direction of the jet axis at the given scales. Complemented with observations showing that the structure of the jet has been stable during long-term monitoring and becomes well collimated at larger distances31,32,33,34,35, the small precession angle observed at the milliarcsecond scales (~1.25°) indicates that the SMBH spin is nearly aligned with the large-scale jet. Simulations of tilted accretion disks show that the inner precessing jets are perpendicular to the coherently precessing disk19,36. To achieve a consistent description of the above, the jet is expected to curve gradually and its precession angle to decrease with the distance from the central SMBH. Hence, we propose the following ansatz for the precession angle ψ(ρ) as a function of the intrinsic length of the jet ρ:

where ψin is the precession angle at the inner region of the jet, ρt denotes the transition location and Δ represents the transition width. This curved jet configuration with the large-scale jet aligning with the SMBH spin is a plausible outcome. Although the inner jet is tightly coupled to the randomly oriented disk at small scales20,36, both the SMBH spin and the large-scale jet are strongly influenced by the large-scale ambient medium. The SMBH spin is determined by the net angular momentum that has accumulated over time, whereas the large-scale jet is shaped by the collimating effect of the ambient medium at larger scales37. The right panel of Fig. 3 illustrates the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the resultant jet. Note that, at scales even closer to the SMBH, the structure of both the disk and the jet may align with the BH spin due to the magneto-spin alignment mechanism20. The extent of this alignment depends on the strength of the magnetic flux20. Given that the precessing disk is constrained to be compact and the accretion state is not fully concluded in M87 (Methods), this alignment configuration is expected to be more compact. Therefore, we ignored it in our analysis.

Left, the red points with 1σ error bars are the projected jet width profile data from ref. 15 based on 86-GHz GMV + ALMA + GLT observations in 2018. The measurement uncertainties account for fitting errors and resolution limits, as described in their Supplementary Information Section 8. The dashed curve shows the projected jet width of the collimated jet with a = 0.9 viewed from a fixed viewing angle ϕ = 17° (refs. 15,32). The solid curve indicates the corresponding projected jet width of a curved jet with the best-fitting parameters. The light curves are predictions with randomly selected parameter samples obtained from a MCMC analysis and represent the uncertainty of the fitting. The precession angle at milliarcsecond scales (1.25° ± 0.18°)16 was incorporated into the MCMC analysis. Right, 3D configuration of the jet structure and the corresponding profile projected onto the sky plane. The z axis is along the LOS. Positive z represents the direction pointing towards the Earth, and the x–y plane indicates the sky plane. The green cone indicates the jet, and its central green solid line represents the jet axis. The magenta arrow denotes the BH spin, which is aligned with the black dashed line representing the precession axis.

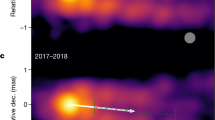

Observations of the jet structure and dynamics at various scales, especially at sub-milliarcsecond scales, are crucial for fully understanding the detailed structure of the jet. In addition to the jet precession observed at 0.7–3 mas (ref. 16), the sub-0.1-mas jet structure15 provides notable constraints. In particular, Lu et al. reported an unexpectedly large jet width at ≲0.1 mas (ref. 15). It exceeds the expected Blandford–Znajek jet12 envelope and indicates the need for another explanation in an untilted system. This discrepancy can be addressed within a precessing jet framework: a larger projected jet width with a smaller viewing angle in the inner regions, which arises naturally when the BH-driven jet is in a phase nearly coplanar with the line of sight (LOS) and the precession axis. The position angle of the jet at ≲0.1 mas aligns roughly with that at larger scales, further supporting the interpretation that the inner jet precession was in such a phase at the time of observation. For simplicity, we assumed that the inner jet was exactly coplanar with the LOS and the precession axis in 2018.

To demonstrate that the curved jet model, inspired by the observed jet precession, effectively addresses the reported anomaly in the inner jet width, we analysed the projected jet width profile and compared it with measurements from ref. 15. The shape of an uncurved jet is modelled by a nearly parabolic cone along the z axis:

where W represents the intrinsic jet width. The parameters C = 0.19 and α = 0.6 were determined by matching the predicted profile of the projected jet width for the uncurved jet case with a = 0.9 (refs. 15,32). The jet was then curved according to the parameterized precession angle (equation (3)) and projected onto the plane perpendicular to the LOS, which allowed us to derive the predicted jet width as a function of the measured jet axial distance (Methods). To account for the precession observation by Cui et al.16, a prior on the precession angle of 1.25° ± 0.18° at 1.8 mas was incorporated into the analysis. The left panel of Fig. 3 compares the predicted jet width profile with observations from Lu et al.15. The curved jet model predicts a wider jet (solid curve) than the collimated jet model (dashed curve) at distances ≲0.1 mas, while maintaining similar jet widths at larger scales. The prediction of the best-fitting model of a precessing curved jet with ψin = 11.1°, ρt = 100rg and Δ = 0.40 aligns closely with the observed data (red dots).

Continuous monitoring of the jet in the region close to the SMBH is crucial for testing the above hypothesis. As the jet precesses, both its position angle and viewing angle vary, especially at the sub-0.1-milliarcsecond scales. The top and middle panels of Fig. 4 illustrate the time evolution of these angles on a projected scale of 0.02 mas. Importantly, the larger precession angle in the inner region causes the viewing angle to decrease when the jet approaches the LOS. This results in an asymmetric time variation curve for the position angle, which exhibits a skewness. The direction of this skewness is determined by the sense of precession and, therefore, by the direction of the SMBH spin. As mentioned above, the SMBH spin almost aligns with the large-scale jet. It can be inferred from this that the SMBH spin is oriented away from the Earth, assuming a finite spin value4. Thus, the skewness of the position angle offers a promising test of the spin direction of the SMBH. Although the time variation of the viewing angle is more challenging to observe directly, it leads to changes in the jet width, as shown in the bottom panel of Fig. 4. Long-term observations resolving sub-milliarcsecond scales15,38,39 are promising for detecting variations in both the position angle and jet width in this region.

The compact precessing disk suggested in this work challenges models with strong magnetization, as the size of the precessing disk correlates with the magnetic field strength19,40,41,42,43. As EHT observations disfavour weakly magnetized disk models4,5,44, together these results indicate that the M87 accretion disk is probably in an intermediate magnetization regime or has some more subtle magnetic field configuration. Further general-relativistic magnetohydrodynamic simulations, particularly those that systematically explore different magnetic field configurations, the environment around the compact disk and disk-tearing conditions, are essential for establishing the physical properties of the tilted accretion disk45. The curvature of the M87 jet revealed in this study reinforces the need for multi-wavelength observations spanning diverse spatial and temporal scales to resolve finer jet structures with advanced imaging techniques46,47,48,49,50 and track their evolution over time. Combined with theoretical efforts, these observations are essential for unveiling the dynamics of the surrounding materials and the processes driving jet formation in the extreme environment near the SMBH.

Methods

The precession of a coherently precessing disk

The precession of a ring of test particles

We start with the LT precession of a ring of test particles at a fixed radius around a spinning SMBH. The orbital angular frequency (Ωorb) of such a ring near the equatorial plane is given by21,22,51:

This relation accounts for the relativistic effects of frame-dragging due to the spin of the SMBH. For orbits tilted slightly out of the equatorial plane, the deviation from the plane oscillates with a vertical frequency Ωz, which differs from Ωorb. This difference arises due to the relativistic frame-dragging. The relation between Ωorb and Ωz satisfies22,52:

The precession of the tilted orbital plane arises from the difference between the orbital (Ωorb) and vertical (Ωz) frequencies: ΩLT(r) = Ωorb − Ωz. From equation (6), we can solve for ΩLT. Denoting the right-hand side of equation (6) as δ, we get:

Note that the correction terms in the parentheses with order \({\mathcal{O}}{({r}_{{\rm{g}}}/r)}^{3/2}\) cancel out upon expansion and terms with order higher than \({\mathcal{O}}{({r}_{{\rm{g}}}/r)}^{3/2}\) have been ignored. The precession period Tprec = 2π/ΩLT, shown in equation (1), is highly sensitive to the disk size.

An extended coherently precessing disk

The precessing disk can be approximated as a torus, characterized by an inner radius rin and an outer radius ro. Such a coherently precessing structure has been demonstrated in recent simulations16,19,52. The precessing disk constitutes only a portion of the accretion disk rather than its entirety. It is important to note that rin and ro should not be interpreted as sharply defined edges but rather as effective radii describing the approximate extent of the precessing disk. They are determined by the interplay between the frame-dragging effects of the spinning SMBH and the internal interactions within the disk. As the torus precesses as a whole, its inner (outer) regions precess more slowly (rapidly) compared to how they would behave as independent rings. This dynamic behaviour necessitates defining an effective radius rLT, which depends on the mass distribution of the precessing disk and serves to characterize its overall response to the frame-dragging of a spinning SMBH.

To describe a coherently precessing disk with finite radial extent and thickness, we define an angular momentum-averaged precession frequency as19,53

where l(r) is the angular momentum density. The effective LT radius rLT is then defined as:

The surface density profile of the precessing disk (integrated over the altitude direction) is assumed to follow σ(r) ∝ r−ζ. Because the region dominating the integrals in equation (8) lies far from the BH, we follow ref. 19 and approximate ΩLT(r) with its leading order in the radius dependence. Under the assumption of a Keplerian orbital velocity v ∝ r−1/2, the leading-order precession frequency is

This provides a direct link between the precession of the disk and its radial structure. The effective LT radius (rLT) arising from this relation is given by equation (2).

Note that a recent study24 also examined the implications of M87 jet precession on the properties of the SMBH spin and the accretion disk. Their Fig. 8 resembles our Fig. 1 if we equate our rLT with their warp radius. However, although they assumed that the jet motion follows a ring of the disk at the warp radius that precesses independently from the rest of the disk, our interpretation is that a torus with a certain size and the jet precess coherently as demonstrated in recent simulations. In terms of disk morphology, the warp radius serves a role like that of our inner radius of the coherently precessing disk bulk. Note that rLT is an effective radius dependent on the mass distribution within the precessing disk. Given these distinctions, we conclude that the coherently precessing disk is compact, and so we further investigate the extended disk size. Our lower bound for a is the same as that given in ref. 24, because, in that case, the coherently precessing disk was confined to a ring with r = rISCO.

The dependence on the tilt angle

Thus far, our analysis has focused on LT precession near the equatorial plane, and equation (1) does not account for the dependence on the tilt angle. The prograde and retrograde scenarios considered in this work represent the two extreme cases. The constraints on the a–rLT parameter space and disk morphology, as presented in Figs. 1 and 2, encapsulate the results for these limiting scenarios. For a general case with an arbitrary tilt angle, the constraints are expected to lie between these two extremes.

The LT precession of a single ring with an arbitrary tilt angle can be computed using the framework outlined in ref. 24, where different tilt angles correspond to different Carter constants. However, the tilt angle is constrained to ≲60° (refs. 54). From our curved jet model, the inner precession angle of the jet is constrained to approximately 11°, indicating a correspondingly small tilt angle for the accretion disk. This supports our approach of focusing on disk precession near the equatorial plane.

Curved jet and the projected width of the inner jet

As demonstrated in ‘Jet structure and inner jet width’, the inner jet may have a larger precession angle, which may explain the unexpectedly large, measured jet width at ≲0.1 mas reported in Lu et al.15. Here, we highlight the technical details in the modelling of and parameter inference for a curved jet. We assumed that the edge shape of the 3D jet can be parameterized by a nearly parabolic function given in equation (4). Both W and ρ are measured in milliarcseconds. The conversion factor is 1 mas = 250rg for M87.

We began by reproducing the theoretical prediction of the jet width as a function of the measured axial distance for a = 0.9. The coordinate system was defined with the x–y plane perpendicular to the LOS and the z axis pointing towards the observer. We constructed a parabolic cone along the z direction, tilted by 17° in the z–y plane. The projection of this cone onto the x–y plane represents the two-dimensional jet observed. The right panel of Fig. 3 is a schematic of a tilted jet and its projection onto the x–y plane (the depicted case of a curved jet will be discussed later). In this projection, the width in the x direction corresponds to the observed jet width, and the y coordinate corresponds to the observed axial distance. By matching the predicted jet width as a function of the axial distance, we determined the parameters C = 0.19 and α = 0.6. The left panel of Supplementary Fig. 1 is a 3D view of the curved jet from an edge-on view. The middle panel illustrates the two-dimensional structure of the jet axis, and the right panel displays the profiles of the precession angle and the viewing angle.

The scenario described above is the standard case assumed in the analysis of Lu et al.15. By contrast, our curved jet model proposes that, rather than forming a collimated cone, the angle between the jet and its precession axis (referred to as the precession angle ψ) decreases from a finite value near the core to zero at large distances, as parameterized by equation (3). Motivated by the observation that the jet position angle at scales ≲0.1 mas is like that at larger scales, the precession of the inner jet is probably in a phase in which the inner jet, the large-scale jet and the LOS are nearly coplanar. Consequently, the jet viewing angle as a function of ρ is given by

assuming ψ < 17°. The value of 17° was adopted from the literature16,55,56. Like the standard case, we projected the curved jet onto the x–y plane to derive the observed jet width as a function of the measured axial distance.

The projected jet width was determined analytically. The equation for the surface of the curved jet was derived as follows. First, each point A on the uncurved jet axis was mapped to a corresponding point A’ on the curved axis, while maintaining the same intrinsic length ρ. We denote the y and z coordinates of A’ as ρy and ρz, respectively. The uncurved jet cone was divided into rings of constant z (corresponding to the length along the jet axis). Each ring was first shifted to the origin by a vector (0, 0, −ρ), rotated by an angle ϕ(ρ) and then shifted again by a vector (0, ρy, ρz). The resulting ring satisfies the following equations:

These transformed rings collectively form the surface of the curved jet. The observed jet width at a given measured jet axial distance y is twice the maximum x coordinate on the surface of the curved jet. From equation (12), the value of ρ that maximizes x for a given y satisfies:

The observed jet width can then be calculated as:

Examples of W(y) for both a curved jet and an uncurved jet are shown in the left panel of Fig. 3, represented by the solid and dashed curves, respectively. The observed jet width is larger for a curved jet than for a collimated one. This occurs because, with smaller viewing angles in the inner region, the same measured axial distance y corresponds to a longer intrinsic jet length ρ, resulting in a wider jet.

We performed a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis of the curved jet model, comparing it with the jet width profile measured by Lu et al.15. The results are presented in Supplementary Fig. 2. Current jet width observations do not uniquely constrain the transition parameters, as there is a degeneracy between the transition position ρt and the inner precession angle ψin. A smaller ρt, combined with a larger ψin, can yield the same observed jet width profile. We introduced a prior ρt > 100rg in the MCMC analysis, motivated because the inner jet remains perpendicular to the precessing disk, at least out to some intermediate scale16,20,36, although releasing this prior did not affect the goodness of fit or our main conclusion.

To predict the evolution of the position angle, viewing angle, and jet width at a projected distance of 0.02 mas from the core, first note that this scale is closer to the core than the transition region. Therefore, we approximated the jet at this scale using a fixed precession angle. Any minor discrepancies from this approximation were addressed by introducing an effective precession angle that matched the measured jet width in 2018. The position and viewing angles were calculated for different times following the method in Cui et al.16. The jet width was determined based on the previously outlined method, taking into account the evolution of the viewing angle.

Change history

14 July 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02625-4

References

Curtis, H. D. Descriptions of 762 nebulae and clusters photographed with the Crossley Reflector. Publ. Lick Obs. 13, 9–42 (1918).

Igumenshchev, I. V., Narayan, R. & Abramowicz, M. A. Three-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic simulations of radiatively inefficient accretion flows. Astrophys. J. 592, 1042–1059 (2003).

Yuan, F. & Narayan, R. Hot accretion flows around black holes. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 52, 529–588 (2014).

Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope results. V. Physical origin of the asymmetric ring. Astrophys. J. Lett. 875, L5 (2019).

Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope results. VIII. Magnetic field structure near the event horizon. Astrophys. J. Lett. 910, L13 (2021).

Reynolds, C. S. The spin of supermassive black holes. Class. Quantum Gravity 30, 244004 (2013).

Risaliti, G. et al. A rapidly spinning supermassive black hole at the centre of NGC 1365. Nature 494, 449–451 (2013).

McClintock, J. E. et al. The spin of the near-extreme Kerr black hole GRS 1915+105. Astrophys. J. 652, 518–539 (2006).

McClintock, J. E., Narayan, R. & Steiner, J. F. Black hole spin via continuum fitting and the role of spin in powering transient jets. Space Sci. Rev. 183, 295–322 (2014).

Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope results. I. The shadow of the supermassive black hole. Astrophys. J. Lett. 875, L1 (2019).

Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. VI. The shadow and mass of the central black hole. Astrophys. J. Lett. 875, L6 (2019).

Blandford, R. D. & Znajek, R. L. Electromagnetic extraction of energy from Kerr black holes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 179, 433–456 (1977).

Blandford, R. D. & Payne, D. G. Hydromagnetic flows from accretion disks and the production of radio jets. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 199, 883–903 (1982).

Hada, K., Asada, K., Nakamura, M. & Kino, M. M 87: a cosmic laboratory for deciphering black hole accretion and jet formation. Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 32, 5 (2024).

Lu, R.-S. et al. A ring-like accretion structure in M87 connecting its black hole and jet. Nature 616, 686–690 (2023).

Cui, Y. et al. Precessing jet nozzle connecting to a spinning black hole in M87. Nature 621, 711–715 (2023).

Lense, J. & Thirring, H. Über den Einfluß der Eigenrotation der Zentralkörper auf die Bewegung der Planeten und Monde nach der Einsteinschen Gravitationstheorie. Phys. Z. 19, 156 (1918).

Fragile, P. C. & Anninos, P. Hydrodynamic simulations of tilted thick-disk accretion onto a Kerr black hole. Astrophys. J. 623, 347–361 (2005).

Fragile, P. C., Blaes, O. M., Anninos, P. & Salmonson, J. D. Global general relativistic magnetohydrodynamic simulation of a tilted black hole accretion disk. Astrophys. J. 668, 417–429 (2007).

McKinney, J. C., Tchekhovskoy, A. & Blandford, R. D. Alignment of magnetized accretion disks and relativistic jets with spinning black holes. Science 339, 49 (2013).

Kato, S. Trapped one-armed corrugation waves and QPO’s. Publ. Astron. Soc. Jpn 42, 99–113 (1990).

Franchini, A., Lodato, G. & Facchini, S. Lense–Thirring precession around supermassive black holes during tidal disruption events. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 455, 1946–1956 (2016).

Bardeen, J. M., Press, W. H. & Teukolsky, S. A. Rotating black holes: locally nonrotating frames, energy extraction, and scalar synchrotron radiation. Astrophys. J. 178, 347–370 (1972).

Wei, S.-W., Zou, Y.-C., Zhang, Y.-P. & Liu, Y.-X. Constraining black hole parameters with the precessing jet nozzle of M87*. Phys. Rev. D 110, 064006 (2024).

Liu, S.-M. & Melia, F. Spin-induced disk precession in the supermassive black hole at the Galactic Center. Astrophys. J. Lett. 573, L23 (2002).

Fragile, P. C. Effective inner radius of tilted black hole accretion disks. Astrophys. J. Lett. 706, L246–L250 (2009).

Doeleman, S. S. et al. Reference array and design consideration for the Next-Generation Event Horizon Telescope. Galaxies 11, 107 (2023).

Palumbo, D. C. M., Wong, G. N. & Prather, B. S. Discriminating accretion states via rotational symmetry in simulated polarimetric images of M87. Astrophys. J. 894, 156 (2020).

Chael, A., Lupsasca, A., Wong, G. N. & Quataert, E. Black hole polarimetry. I. A signature of electromagnetic energy extraction. Astrophys. J. 958, 65 (2023).

Ricarte, A., Tiede, P., Emami, R., Tamar, A. & Natarajan, P. The ngEHT’s role in measuring supermassive black hole spins. Galaxies 11, 6 (2023).

Asada, K. & Nakamura, M. The structure of the M87 jet: a transition from parabolic to conical streamlines. Astrophys. J. Lett. 745, L28 (2012).

Nakamura, M. et al. Parabolic jets from the spinning black hole in M87. Astrophys. J. 868, 146 (2018).

EHT MWL Science Working Groupet al. Broadband multi-wavelength properties of M87 during the 2017 Event Horizon Telescope campaign. Astrophys. J. Lett. 911, L11 (2021).

Nikonov, A. S., Kovalev, Y. Y., Kravchenko, E. V., Pashchenko, I. N. & Lobanov, A. P. Properties of the jet in M87 revealed by its helical structure imaged with the VLBA at 8 and 15 GHz. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 526, 5949–5963 (2023).

EHT MWL Science Working Groupet al. Broadband multi-wavelength properties of M87 during the 2018 EHT campaign including a very high energy flaring episode. Astron. Astrophys. 692, A140 (2024).

Liska, M. et al. Formation of precessing jets by tilted black hole discs in 3D general relativistic MHD simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 474, L81–L85 (2018).

Rohoza, V. et al. How to turn jets into cylinders near supermassive black holes in 3D general relativistic magnetohydrodynamic simulations. Astrophys. J. Lett. 963, L29 (2024).

Hada, K. et al. High-sensitivity 86 GHz (3.5 mm) VLBI observations of M87: deep imaging of the jet base at a resolution of 10 Schwarzschild radii. Astrophys. J. 817, 131 (2016).

Kim, J. Y. et al. The limb-brightened jet of M87 down to the 7 Schwarzschild radii scale. Astron. Astrophys. 616, A188 (2018).

Porth, O. et al. The event horizon general relativistic magnetohydrodynamic code comparison project. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 243, 26 (2019).

Chatterjee, K. & Narayan, R. Flux eruption events drive angular momentum transport in magnetically arrested accretion flows. Astrophys. J. 941, 30 (2022).

Tchekhovskoy, A. in The Formation and Disruption of Black Hole Jets (eds Contopoulos, I. et al.) 45–82 (Springer, 2015).

Gupta, S. & Dexter, J. Shock-induced partial alignment in geometrically thick tilted accretion disks around black holes. Astrophys. J. 974, 209 (2024).

Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope results. IX. Detection of near-horizon circular polarization. Astrophys. J. Lett. 957, L20 (2023).

Fragile, P. C. & Liska, M. in New Frontiers in GRMHD Simulations (eds Bambi, C. et al.) 361–387 (Springer, 2025).

Janssen, M. et al. rPICARD: A CASA-based calibration pipeline for VLBI data. Calibration and imaging of 7 mm VLBA observations of the AGN jet in M 87. Astron. Astrophys. 626, A75 (2019).

Chael, A. A. et al. ehtim: imaging, analysis, and simulation software for radio interferometry. Astrophysics Source Code Library ascl:1904.004 (2019).

Tiede, P. Comrade: composable modeling of radio emission. J. Open Source Softw. 7, 4457 (2022).

Tazaki, F. et al. Super-resolved image of M87 observed with East Asian VLBI network. Galaxies 11, 39 (2023).

Kim, J.-S. et al. Bayesian self-calibration and imaging in very long baseline interferometry. Astron. Astrophys. 690, A129 (2024).

Lubow, S. H., Ogilvie, G. I. & Pringle, J. E. The evolution of a warped disc around a Kerr black hole. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 337, 706–712 (2002).

Lodato, G. & Facchini, S. Wave-like warp propagation in circumbinary discs. II. Application to KH 15D. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 433, 2157–2164 (2013).

Nixon, C. J. & King, A. R. Broken discs: warp propagation in accretion discs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 421, 1201–1208 (2012).

Wielgus, M. et al. Monitoring the morphology of M87* in 2009–2017 with the Event Horizon Telescope. Astrophys. J. 901, 67 (2020).

Mertens, F., Lobanov, A. P., Walker, R. C. & Hardee, P. E. Kinematics of the jet in M 87 on scales of 100-1000 Schwarzschild radii. Astron. Astrophys. 595, A54 (2016).

Walker, R. C., Hardee, P. E., Davies, F. B., Ly, C. & Junor, W. The structure and dynamics of the subparsec jet in M87 based on 50 VLBA observations over 17 years at 43 GHz. Astrophys. J. 855, 128 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Hada and M. Honma for the valuable discussion and comments and R. Lu for sharing the measurements of the jet width from Lu et al.15. We would like to express our gratitude to P. C. Fragile for his thoughtful and detailed comments, suggestions and explanations regarding the current numerical simulations as well as for his insights into future directions for the theory. We are grateful to the South-Western Institute for Astronomy Research of Yunnan University for their support during Y.C.’s visit. Open access funding is provided by the Key Program of National Nature Science Foundation of China under grant No. 12033001. W.L. acknowledges that this work is supported by the Science & Technology Champion Project (Grant No. 202005AB160002) and the Top Team Project (Grant No. 202305AT350002), both funded by Yunnan Revitalization. W.L. is also supported by a Yunnan General Grant (Grant No. 202401AT070489). Y.C. is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12303021) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2024T170845).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors jointly contributed to all parts of this work including the research design, data analysis and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Astronomy thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary discussion and Figs. 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, Y., Lin, W. Co-precession of a curved jet and compact accretion disk in M87. Nat Astron 9, 1218–1225 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02580-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02580-0