Abstract

Magnetic reconnection is a fundamental process within highly conductive plasmas. Oppositely oriented field lines are reconfigured, releasing stored magnetic energy. It plays a vital role in shaping the dynamics of the solar corona and provides one of the main mechanisms for releasing the stored energy that powers solar eruptions. Reconnection at the Sun has been studied using remote-sensing observations, but the Parker Solar Probe (PSP) now permits in situ sampling of reconnection-related plasma in the corona. Here we report on a PSP fly-through of a reconnecting current sheet in the corona during a major solar eruption on 5–6 September 2022. We find that even 24 h after the flare peak, PSP detected the reconnection exhaust, indicating continuing fast reconnection, which we confirmed using remote-sensing observations made by the Solar Orbiter. This reconnection persisted much longer than typical timescales of a few minutes to hours. Plasma parameters measured by PSP within the reconnection region match numerical simulations. These new observations provide a key bridge between theory and measurements of plasmas in the solar atmosphere, laboratory experiments and astrophysical systems, generating new constraints required for the refinement of models and for the strengthening of their links to observations at many scales.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The PSP mission data used in this study are openly available at the CDAWeb of the NASA Space Physics Data Facility (https://cdaweb.gsfc.nasa.gov/). The SolO mission data are openly available in the ESA Solar Orbiter Archive (https://soar.esac.esa.int/soar/). The simulation data will be shared upon request to author X.X. (xiaoyan.xie@cfa.harvard.edu).

Code availability

The codes used for reducing and analysing the data are available as part of the SolarSoft library (https://www.lmsal.com/solarsoft/sswdb_description.html). The public version of the NIRVANA code is available on the GitLab repository (https://gitlab.aip.de/ziegler/NIRVANA). Python packages Astropy (v.5.1, https://github.com/astropy/astropy), Astrospice (v.0.2, now archived, https://github.com/astrospice/astrospice/tree/main/astrospice), Pyspedas (v.4.1.0, https://github.com/spedas/pyspedas), Matplotlib (v3.5.2, https://github.com/matplotlib/matplotlib) and Sunpy (v.5.0, https://github.com/sunpy/sunpy) were used in creating some of the figures.

References

Sweet, P. A. Electromagnetic phenomena in cosmical physics. In Proc. IAU Symposium No 6 (ed. Lehnert, B.) 123 (Cambridge University Press, 1958).

Parker, E. N. Sweet’s mechanism for merging magnetic fields in conducting fluids. J. Geophys. Res. 62, 509–520 (1957).

Petschek, H. E. Magnetic field annihilation. In Proc. AAS-NASA Symposium on the Physics of Solar Flares (ed. Hess, W. N.) 425–439 (NASA, 1964).

Sturrock, P. A. Model of the high-energy phase of solar flares. Nature 211, 695–697 (1966).

Kopp, R. A. & Pneuman, G. W. Magnetic reconnection in the corona and the loop prominence phenomenon. Sol. Phys. 50, 85–98 (1976).

Shibata, K. & Tanuma, S. Plasmoid-induced-reconnection and fractal reconnection. Earth Planets Space 53, 473–482 (2001).

Bhattacharjee, A. Impulsive magnetic reconnection in the Earth’s magnetotail and the solar corona. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 42, 365–384 (2004).

Cassak, P. A. & Shay, M. A. Magnetic reconnection for coronal conditions: reconnection rates, secondary islands and onset. Space Sci. Rev. 172, 283–302 (2012).

Su, Y. et al. Imaging coronal magnetic-field reconnection in a solar flare. Nat. Phys. 9, 489–493 (2013).

Reeves, K. K., McCauley, P. I. & Tian, H. Direct observations of magnetic reconnection outflow and CME triggering in a small erupting solar prominence. Astrophys. J. 807, 7 (2015).

Patel, R., Pant, V., Chandrashekhar, K. & Banerjee, D. A statistical study of plasmoids associated with a post-CME current sheet. Astron. Astrophys. 644, A158 (2020).

Chen, B. et al. Measurement of magnetic field and relativistic electrons along a solar flare current sheet. Nat. Astron. 4, 1140–1147 (2020).

Yan, X. et al. Fast plasmoid-mediated reconnection in a solar flare. Nat. Commun. 13, 640 (2022).

Gosling, J. T., Skoug, R. M., McComas, D. J. & Smith, C. W. Direct evidence for magnetic reconnection in the solar wind near 1 au. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 110, A01107 (2005).

Gosling, J. T., Skoug, R. M., McComas, D. J. & Smith, C. W. Magnetic disconnection from the Sun: observations of a reconnection exhaust in the solar wind at the heliospheric current sheet. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L05105 (2005).

Phan, T. D. et al. Parker Solar Probe in situ observations of magnetic reconnection exhausts during Encounter 1. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 246, 34 (2020).

Lin, J. & Forbes, T. G. Effects of reconnection on the coronal mass ejection process. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 2375–2392 (2000).

Øieroset, M., Phan, T. D., Fujimoto, M., Lin, R. P. & Lepping, R. P. In situ detection of collisionless reconnection in the Earth’s magnetotail. Nature 412, 414–417 (2001).

Burch, J. L. et al. Electron-scale measurements of magnetic reconnection in space. Science 352, aaf2939 (2016).

Torbert, R. B. et al. Electron-scale dynamics of the diffusion region during symmetric magnetic reconnection in space. Science 362, 1391–1395 (2018).

Eastwood, J. P. et al. Evidence for collisionless magnetic reconnection at Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L02106 (2008).

Zhang, T. L. et al. Magnetic reconnection in the near Venusian magnetotail. Science 336, 567 (2012).

Arridge, C. S. et al. Cassini in situ observations of long-duration magnetic reconnection in Saturn’s magnetotail. Nat. Phys. 12, 268–271 (2016).

Hanasz, M. & Lesch, H. Conditions for fast magnetic reconnection in astrophysical plasmas. Astron. Astrophys. 404, 389–395 (2003).

Weżgowiec, M., Ehle, M. & Beck, R. Hot gas and magnetic arms of NGC 6946: indications for reconnection heating? Astron. Astrophys. 585, A3 (2016).

Ripperda, B., Bacchini, F. & Philippov, A. A. Magnetic reconnection and hot spot formation in black hole accretion disks. Astrophys. J. 900, 100 (2020).

Shukla, A. & Mannheim, K. Gamma-ray flares from relativistic magnetic reconnection in the jet of the quasar 3C 279. Nat. Commun. 11, 4176 (2020).

Aimar, N. et al. Magnetic reconnection plasmoid model for Sagittarius A* flares. Astron. Astrophys. 672, A62 (2023).

Bhattacharjee, A., Huang, Y.-M., Yang, H. & Rogers, B. Fast reconnection in high-Lundquist-number plasmas due to the plasmoid Instability. Phys. Plasmas 16, 112102 (2009).

Forbes, T. G., Seaton, D. B. & Reeves, K. K. Reconnection in the post-impulsive phase of solar flares. Astrophys. J. 858, 70 (2018).

Yamada, M. et al. Study of driven magnetic reconnection in a laboratory plasma. Phys. Plasmas 4, 1936–1944 (1997).

Bolaños, S. et al. Laboratory evidence of magnetic reconnection hampered in obliquely interacting flux tubes. Nat. Commun. 13, 6426 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Pree, S. & Bellan, P. M. Generation of laboratory nanoflares from multiple braided plasma loops. Nat. Astron. 7, 655–661 (2023).

Ji, H. et al. Laboratory study of collisionless magnetic reconnection. Space Sci. Rev. 219, 76 (2023).

Fox, N. J. et al. The Solar Probe Plus Mission: humanity’s first visit to our star. Space Sci. Rev. 204, 7–48 (2016).

Patel, R. et al. The closest view of a fast coronal mass ejection: how faulty assumptions near perihelion lead to unrealistic interpretations of PSP/WISPR observations. Astrophys. J. Lett. 955, L1 (2023).

García Marirrodriga, C. et al. Solar Orbiter: mission and spacecraft design. Astron. Astrophys. 646, A121 (2021).

West, M. J. & Seaton, D. B. SWAP observations of post-flare giant arches in the long-duration 14 October 2014 solar eruption. Astrophys. J. Lett. 801, L6 (2015).

French, R. J., Matthews, S. A., van Driel-Gesztelyi, L., Long, D. M. & Judge, P. G. Dynamics of late-stage reconnection in the 2017 September 10 solar flare. Astrophys. J. 900, 192 (2020).

Long, D. M. et al. The eruption of a magnetic flux rope observed by Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe. Astrophys. J. 955, 152 (2023).

Vourlidas, A. et al. The Wide-Field Imager for Solar Probe Plus (WISPR). Space Sci. Rev. 204, 83–130 (2016).

Howard, R. A. et al. Overview of the remote sensing observations from PSP Solar Encounter 10 with perihelion at 13.3 R⊙. Astrophys. J. 936, 43 (2022).

Romeo, O. M. et al. Near-Sun in situ and remote-sensing observations of a coronal mass ejection and its effect on the heliospheric current sheet. Astrophys. J. 954, 168 (2023).

Rochus, P. et al. The Solar Orbiter EUI instrument: the extreme ultraviolet imager. Astron. Astrophys. 642, A8 (2020).

de Jager, C. & Svestka, Z. 21 May 1980 flare review. Sol. Phys. 100, 435 (1985).

Noglik, J. B., Walsh, R. W. & Ireland, J. Indirect calculation of the magnetic reconnection rate from flare loops. Astron. Astrophys. 441, 353–360 (2005).

Savage, S. L., McKenzie, D. E., Reeves, K. K., Forbes, T. G. & Longcope, D. W. Reconnection outflows and current sheet observed with Hinode/XRT in the 2008 April 9 ‘cartwheel CME’ flare. Astrophys. J. 722, 329–342 (2010).

Cheng, X. et al. Observations of turbulent magnetic reconnection within a solar current sheet. Astrophys. J. 866, 64 (2018).

Solanki, S. K. et al. The polarimetric and helioseismic imager on Solar Orbiter. Astron. Astrophys. 642, A11 (2020).

Badman, S. T. et al. Prediction and verification of Parker Solar Probe Solar wind sources at 13.3 R⊙. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 128, e2023JA031359 (2023).

Bale, S. D. et al. The FIELDS instrument suite for Solar Probe Plus. Measuring the coronal plasma and magnetic field, plasma waves and turbulence, and radio signatures of solar transients. Space Sci. Rev. 204, 49–82 (2016).

Kasper, J. C. et al. Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons (SWEAP) investigation: design of the solar wind and coronal plasma instrument suite for Solar Probe Plus. Space Sci. Rev. 204, 131–186 (2016).

Rivera, Y. J. et al. In situ observations of large-amplitude Alfvén waves heating and accelerating the solar wind. Science 385, 962–966 (2024).

Gosling, J. T. et al. Bidirectional solar wind electron heat flux events. J. Geophys. Res. 92, 8519–8535 (1987).

Chen, Y. et al. Can the Parker Solar Probe detect a CME-flare current sheet? Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 269, 22 (2023).

Liu, Y.-H. et al. First-principles theory of the rate of magnetic reconnection in magnetospheric and solar plasmas. Commun. Phys. 5, 97 (2022).

Daughton, W. et al. Role of electron physics in the development of turbulent magnetic reconnection in collisionless plasmas. Nat. Phys. 7, 539–542 (2011).

Carcaboso, F. et al. Characterisation of suprathermal electron pitch-angle distributions. Bidirectional and isotropic periods in solar wind. Astron. Astrophys. 635, A79 (2020).

Mei, Z. X., Keppens, R., Roussev, I. I. & Lin, J. Magnetic reconnection during eruptive magnetic flux ropes. Astron. Astrophys. 604, L7 (2017).

Mei, Z. et al. Numerical simulation on the leading edge of coronal mass ejection in the near-Sun region. Astrophys. J. 958, 15 (2023).

Forbes, T. G. & Lin, J. What can we learn about reconnection from coronal mass ejections? J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 62, 1499–1507 (2000).

Liu, Y. D. et al. Direct in situ measurements of a fast coronal mass ejection and associated structures in the corona. Astrophys. J. 963, 85 (2024).

Thernisien, A. F. R., Howard, R. A. & Vourlidas, A. Modeling of flux rope coronal mass ejections. Astrophys. J. 652, 763–773 (2006).

Moore, R. L., Sterling, A. C., Hudson, H. S. & Lemen, J. R. Onset of the magnetic explosion in solar flares and coronal mass ejections. Astrophys. J. 552, 833–848 (2001).

Huang, J. et al. Parker Solar Probe observations of high plasma β solar wind from the streamer belt. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 265, 47 (2023).

Yokoyama, T. & Shibata, K. Magnetohydrodynamic simulation of a solar flare with chromospheric evaporation effect based on the magnetic reconnection model. Astrophys. J. 549, 1160–1174 (2001).

Ni, L., Kliem, B., Lin, J. & Wu, N. Fast magnetic reconnection in the solar chromosphere mediated by the plasmoid instability. Astrophys. J. 799, 79 (2015).

Isobe, H. et al. Reconnection rate in the decay phase of a long duration event flare on 1997 May 12. Astrophys. J. 566, 528–538 (2002).

Ramesh, R., Narayanan, A. S., Kathiravan, C., Sastry, C. V. & Shankar, N. U. An estimation of the plasma parameters in the solar corona using quasi-periodic metric type III radio burst emission. Astron. Astrophys. 431, 353–357 (2005).

Czaykowska, A., Alexander, D. & De Pontieu, B. Chromospheric heating in the late phase of two-ribbon flares. Astrophys. J. 552, 849–857 (2001).

Ziegler, U. The NIRVANA code: parallel computational MHD with adaptive mesh refinement. Comput. Phys. Commun. 179, 227–244 (2008).

Forbes, T. G. Magnetic reconnection in solar flares. Geophys. Astrophys. Fluid Dyn. 62, 15–36 (1991).

Sittler Jr, E. C. & Guhathakurta, M. Semiempirical two-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic model of the solar corona and interplanetary medium. Astrophys. J. 523, 812–826 (1999).

Xie, X. et al. Numerical experiments on dynamic evolution of a CME-flare current sheet. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 509, 406–420 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank T. G. Forbes, N. E. Raouafi and Z. Mei for helpful discussions while we carried out the analysis for this paper. This work originally developed during the team meetings of the Connect programme of NASA’s Heliophysics System Observatory: Energetics of solar eruptions from the chromosphere to the inner heliosphere project, supported by Grant No. 80NSSC20K1283. The WISPR, FIELDS and SWEAP suites were designed, developed and are operated under NASA contract NNN06AA01C. We acknowledge the extraordinary contributions of the PSP mission operations and spacecraft engineering team at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. The PSP was designed, built and is now operated by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory as part of NASA’s Living with a Star programme (Contract No. NNN06AA01C). The EUI instrument was built by CSL, IAS, MPS, MSSL/UCL, PMOD/WRC, ROB, LCF/IO with funding from the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office (Grant Nos. BELSPO/PRODEX PEA 4000134088, 4000112292, 4000117262 and 4000134474); the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES); the UK Space Agency; the Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie (BMWi) through the Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR); and the Swiss Space Office. The space mission SolO is the result of an international collaboration between ESA and NASA, and it is operated by ESA. The NIRVANA code was developed by U. Ziegler at the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam. We are grateful to the ESA SOC and MOC teams for their support. The German contribution to SO/PHI is funded by the BMWi through DLR and by MPG central funds. The Spanish contribution is funded by AEI/MCIN/10.13039/501100011033/ and the European Union Next Generation EU/PRTR (Grant Nos. RTI2018-096886-C5, PID2021-125325OB-C5, PCI2022-135009-2 and PCI2022-135029-2) and ERDF – A way of making Europe; Center of Excellence Severo Ochoa awards to IAA-CSIC (SEV-2017-0709, CEX2021-001131-S); and a Ramón y Cajal fellowship awarded to D.O.S. The French contribution is funded by CNES. R.P., D.B.S., M.J.W., K.K.R., S.R., X.X. and T.N. were supported by the Connect programme of NASA’s Heliophysics System Observatory (Grant No. 80NSSC20K1283). S.T.B. and Y.J.R. were supported by the PSP project through the SAO/SWEAP (Subcontract No. 975569). G.S. was supported by WISPR Phase-E funds. P.H. is funded by the Office of Naval Research. This project has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement No. 101097844 for project WINSUN).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.P. led the work, carried out the analysis of the remote-sensing data and led the preparation of the paper. T.N. carried out the analysis of PSP in situ data. X.X. carried out the numerical simulation and provided its results. D.B.S. contributed towards the interpretation of the data, models and results and worked on improving the figures. S.T.B. performed the ballistic projection of the magnetogram data. S.R. interpreted the flare energetics. Y.J.R. helped interpretation of in situ signatures and results. K.K.R. interpreted the data, models and results. G.S. processed the WISPR data and provided its outputs. P.H. and M.J.W. helped in interpreting the WISPR and EUI data, respectively. A.F., J.H., D.O.S., S.K.S., H.S. and G.V. processed and provided SO/PHI data. All authors participated in discussing the results and writing the draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Astronomy thanks Philippa Browning and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

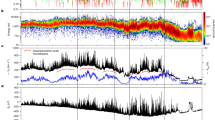

Extended Data Fig. 1 Additional plasma parameters based on PSP measurements.

(a) PSP in situ measurement of BR on 6 September 2022 from 17:25 to 17:45 UT, the time period used for generating PSP data plots in Fig. 4, right panel, shown in red for consistency with Figs. 3 and 4. Derived parameters in panels (b - e) are Alfvén speed (VA), total pressure (PTOTAL), proton plasma beta (ß) and Alfvén Mach number (MA) respectively during this period. The vertical dashed line at 17:35 UT is the same reference time as in Fig. 3.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Schematic of the September 5, 2022 CME.

The dimensions are not to scale and have been exaggerated to visualize the extent of the CME, current sheet and PSP orbit plane in the context of the CME source region. Even though the source region (shown with the red-blue pair of filled circles) is in the southern hemisphere, the CME is wide enough that PSP crosses its associated current sheet. The light blue triangle shows the part of the current sheet lying above the plane along the vector radial to the source region, whereas the magenta region is below that plane. The black arrow at the top of the sphere and the solid black curve near the center represent the solar north pole and equator, respectively. The gray shaded region bound by a dashed line shows PSP’s orbit plane. Note that in the real scenario, the active region is more complex (Fig. 3b), and the flare loops arcade shows inclined orientation as shown in Fig. 2. For simplicity, here we only show a portion of the complicated arcade system, which should not be confused with the loops orientation seen in EUI images. Further, the flux rope structure has traveled well out into interplanetary space.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Spatial distributions and parameter profiles from the 2.5D magnetohydrodynamic models.

The left panel shows a snapshot of the distributions of density (color shading) and magnetic field (solid curves) at 1641 s. Reference coordinates in R and T direction with respect to PSP are shown in the top left corner of this panel. Magnetic field, speed, density, temperature and current density as a function of distance are plotted from left to right panels along inclined cuts marked with black arrows at different heights for comparison. Note that the distance in these panels from 0 to 20 Mm in the horizontal axis corresponds to x = 10 Mm to x = -10 Mm in the left panel, that is from right to left along the black arrow. The same is applicable to the right panel based on PSP measurements, where the time axis is converted to distance.

Supplementary information

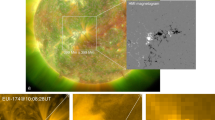

Supplementary Video 1

Imaging observation from 12:00 ut on 5 September 2022 to 23:14 ut on 6 September 2022 by the WISPR-I telescope of PSP. Snapshots of this video at various timestamps are shown in Fig. 1.

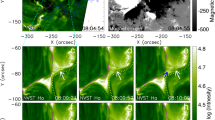

Supplementary Video 2

The evolution of the active region of interest. The left panel shows SO/PHI observations that are related to Fig. 3b. The middle and right panels show FSI observations of the same region at 174 and 304 Å, respectively. Stills from these two panels are shown in Fig. 2b,c and 2e,f, respectively.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, R., Niembro, T., Xie, X. et al. Direct in situ observations of eruption-associated magnetic reconnection in the solar corona. Nat Astron 9, 1444–1454 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02623-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02623-6