Abstract

Debris disks are exosystems thought to arise from collisions among planetesimals. Despite being dust dominated, ALMA has detected reservoirs of CO gas in some debris disks. The origin of this gas is debated, as it could be primordial H2-dominated gas from the parent protoplanetary disk, or it could be released by volatile-rich minor bodies. Here we report JWST/NIRSpec observations of the 49 Ceti debris disk that spatially resolve ro-vibrational CO emission. The CO spectra can be explained by fluorescent excitation from ultraviolet and infrared stellar photons. We show that this technique of resolving fluorescently excited CO is sensitive to small CO masses that could go undetected by ALMA. We compare the CO excitation temperatures derived from our model fitting of the JWST spectra to predictions for an H2-rich and secondary gas model for the system and find that our results do not appear consistent with the H2-rich gas model. Resolving fluorescently excited CO emission opens a door for probing the nature of gas in debris disks and determining if it is long-lived primordial gas or if it is released from volatile-rich minor bodies.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data used in this work are from GO programme 1563 (PI: C.H.C.) and are publicly available from the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes at STScI (https://mast.stsci.edu). The data used for this analysis are available at https://doi.org/10.17909/07pe-y474. The PSF-subtracted data cube and extracted 1D spectra used in the analysis are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16580531 (ref. 60).

Code availability

The code used for performing PSF subtraction on the NIRSpec IFU cubes, generating the CO fluorescence model and fitting the model to the data, which were used in this analysis, is available via Code Ocean at https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.8046058.v1.

References

Hughes, A. M., Duchêne, G. & Matthews, B. C. Debris disks: structure, composition, and variability. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 56, 541–591 (2018).

Dent, W. R. F. et al. Molecular gas clumps from the destruction of icy bodies in the β Pictoris debris disk. Science 343, 1490 (2014).

Marino, S. et al. Exocometary gas in the HD 181327 debris ring. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 460, 2933–2944 (2016).

Lieman-Sifry, J. et al. Debris disks in the Scorpius-Centaurus OB association resolved by ALMA. Astrophys. J. 828, 25 (2016).

Moór, A. et al. Molecular gas in debris disks around Young A-type stars. Astrophys. J. 849, (2017).

Matrà, L. et al. Exocometary gas structure, origin, and physical properties around β Pictoris through ALMA CO multitransition observations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 464, 1415–1433 (2017).

Matrà, L. et al. On the ubiquity and stellar luminosity dependence of exocometary CO gas: detection around M Dwarf TWA 7. Astron. J. 157, 117 (2019).

Kóspál, Á. et al. ALMA observations of the molecular gas in the debris disk of the 30 Myr old star HD 21997. Astrophys. J. 776, 77 (2013).

Visser, R. et al. The photodissociation and chemistry of CO isotopologues: applications to interstellar clouds and circumstellar disks. Astron. Astrophys. 503, 323–343 (2009).

Kral, Q. et al. Imaging [CI] around HD 131835: reinterpeting young debris discs with protoplanetary disc levels of CO gas as shielded secondary discs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 489, 3670–3691 (2019).

Cataldi, G. et al. Primordial or secondary? Testing models of debris disk gas with ALMA. Astrophys. J. 951, 111 (2023).

Kral, Q., Davoult, J. & Charnay, B. Formation of secondary atmospheres on terrestrial planets by late disk accretion. Nat. Astron. 4, 769 (2020).

Troutman, M. et al. Ro-vibrational CO detected in the β Pictoris circumstellar disk. Astrophys. J. 738, 12 (2011).

Brennan, A. et al. Low CI/CO abundance ratio revealed by HST UV spectroscopy of CO-rich debris discs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 531, 4482–4502 (2024).

Najita, J. et al. Gas in the terrestrial planet region of disks: CO fundamental emission from T Tauri stars. Astrophys. J. 589, 931–952 (2003).

Brittain, S. et al. Warm gas in the inner disks around young intermediate-mass stars. Astrophys. J. 659, 685–704 (2007).

Krotkov, R. et al. Ultraviolet pumping of molecular vibrational states: the CO infrared bands. Astrophys. J. 240, 940–949 (1980).

Brown, J. M. et al. VLT-CRIRES survey of rovibrational CO emission from protoplanetary disks. Astrophys. J. 770, 21 (2013).

Brittain, S. et al. Tracing the inner edge of the disk around HD 100645 with rovibrational CO emission lines. Astrophys. J. 702, 85–99 (2009).

Zuckerman, B. et al. A 40 Myr old gaseous circumstellar disk at 49 Ceti: massive CO-rich comet clouds at Young A-type stars. Astrophys. J. 758, 10 (2012).

Moór, A. et al. New millimeter CO observations of the gas-rich debris disks 49 Ceti and HD 32297. Astrophys. J. 884, 15 (2019).

Higuchi, A. Physical conditions of gas components in debris disks of 49 Ceti and HD 21997. Astrophys. J. 905, 122 (2020).

Roberge, A. et al. Herschel observations of gas and dust in the unusual 49 Ceti debris disk. Astrophys. J. 771, 69 (2013).

Chen, C. H. et al. Spitzer IRS spectroscopy of IRAS-discovered debris disks. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 166, 351–337 (2006).

Higuchi, A. et al. First subarcsecond submillimeter-wave [C I] image of 49 Ceti with ALMA. Astrophys. J. 883, 180 (2019).

Hughes, A. M. et al. Radial surface density profiles of gas and dust in the debris disk around 49 Ceti. Astrophys. J. 839, 86 (2017).

Marino, S. et al. Vertical evolution of exocometary gas—I. How vertical diffusion shortens the CO lifetime. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 515, 507–524 (2022).

Li, G. et al. Rovibrational line lists for nine isotopologues of the CO molecule in the X1Σ+ ground electronic state. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 216, 18 (2015).

Beegle, L. et al. High resolution emission spectroscopy of the A1Π-X1Σ+ fourth positive band system of CO excited by electronic impact. Astron. Astrophys. 347, 375–390 (1999).

Choquet, E. et al. First scattered-light images of the gas-rich debris disk around 49 Ceti. Astrophys. J. Lett. 834, L12 (2017).

Yang, B. et al. Rotational quenching of CO due to H2 collisions. Astrophys. J. 718, 2062–2069 (2010).

Ednres, C. P. The Cologne Database for Molecular Spectroscopy, CDMS, in the Virtual Atomic and Molecular Data Centre, VAMDC. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 327, 95–104 (2016).

Wilson, T. L. & Rood, R. Abundances in the interstellar medium. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 32, 191–226 (1994).

Lewis, J. et al. Probing protoplanetary disk upper atmospheres for heating and dust settling using synthetic CO spectra. J. South. Assoc. Res. Astron. 4, 20–25 (2010).

van Dishoeck, E. F. & Black, J. H. The photodissociation and chemistry of interstellar CO. Astrophys. J. 334, 771 (1988).

Mumma, M. J. & Charnley, S. B. The chemical composition of comets—emerging taxonomies and natal heritage. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 49, 471–524 (2011).

Cutri, R. M. et al. VizieR Online Data Catalog: 2MASS ALL-Sky Catalog of Point Sources (Cutri+ 2003) (IPAC/California Institute of Technology, 2003).

Böker, T. et al. The Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) on the James Webb Space Telescope. III. Integral field spectroscopy. Astron. Astrophys. 661, 13 (2022).

Bushouse, H. et al. JWST Calibration Pipeline, 1.13.4. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10569856 (2024).

Ren, B. & Perrin, M. DebrisDiskFM, v1.0. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2398963 (2018).

Hughes, A. M. et al. A resolved molecular gas disk around the nearby A star 49 Ceti. Astrophys. J. 681, 626–635 (2008).

Gordon, I. E. et al. The HITRAN2020 molecular spectroscopic database. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 277, 107949 (2022).

Hein Bertelsen, R. P. et al. CO ro-vibrational lines in HD 100546. A search for disc asymmetries and the role of fluorescence. Astron. Astrophys. 561, A102 (2014).

Gaia Collaboration et al. GAIA Early Data Release 3. Summary of contents and survey properties. Astron. Astrophys. 649, 20 (2021).

McDowell, R. S. Rotational partition function for linear molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 88, 356–361 (1988).

Banzatti, A. et al. EX Lupi from quiescence to outburst: exploring the LTE approach in modeling blended H2O and OH mid-infrared emission. Astrophys. J. 745, 90 (2012).

Jakobsen, P. et al. The Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) on the James Webb Space Telescope. I. Overview of the instrument and its capabilities. Astron. Astrophys. 661, 22 (2022).

Castelli, F. & Kurucz, R. L. New grids of ATLAS9 model atmospheres. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0405087 (2004).

Thompson, G. I. Catalogue of Stellar Ultraviolet Fluxes: A Compilation of Absolute Stellar Fluxes Measured by the Sky Survey Telescope (S2/68) Aboard the ESRO Satellite TD-1 (Science Research Council, 1978).

Roberge, A. et al. Volatile-rich circumstellar gas in the unusual 49 Ceti debris disk. Astrophys. J. Lett. 796, 5 (2014).

Fitzpatrick, E. Correcting for the effects of interstellar extinction. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 111, 63–75 (1999).

Morton, D. C. & Noreau, L. A complication of electronic transitions in the CO molecule and the interpretation of some puzzling interstellar absorption features. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 95, 301 (1994).

Paganini, L. et al. Ground-based infrared detections of CO in the Centaur-comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1 at 6.26 au from the Sun. Astrophys. J. 766, 100 (2013).

Brittain, S. D. et al. CO emission from disks around AB Aurigae and HD 141569: implications for disk structure and planet formation timescales. Astrophys. J. 588, 535–544 (2003).

Storn, R. & Price, K. Differential evolution—a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J. Global Optim. 11, 341–359 (1997).

Foreman-Mackey, D. et al. emcee: the MCMC hammer. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 125, 306 (2013).

Laor, A. & Draine, B. Spectroscopic constraints on the properties of dust in active galactic nuclei. Astrophys. J. 402, 441 (1993).

Wahhaj, Z. et al. High-resolution imaging of the dust disk around 49 Ceti. Astrophys. J. 661, 368–373 (2007).

Draine, B. T. & Lee, H. M. Optical properties of interstellar graphite and silicate grains. Astrophys. J. 284, 89 (1984).

Worthen, K. et al. Fluorescently excited CO emission in the 49 Ceti debris disk spatially resolved by JWST/NIRSpec: the reduced data. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16580531 (2025).

Rebollido, I. et al. The search for gas in debris discs: ALMA detection of CO gas in HD 36546. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 509, 693–700 (2022).

Matrà, L. et al. Detection of exocometary CO within the 440 Myr old Fomalhaut Belt: a similat CO+CO2 ice abundace in exocomets and Solar System comets. Astrophys. J. 842, 15 (2017).

Hales, A. et al. ALMA observations of the HD 110058 debris disk. Astrophys. J. 940, 20 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work is based on observations made with the NASA/ESA/CSA JWST. The data were obtained from the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) contract NAS 5-03127 for JWST. These observations are associated with GO programme 1563. K.W. is supported by NASA under grant no. 80NSSC22K1752 issued through the Mission Directorate. A.M.H. is supported by the National Science Foundations under grant no. AST-2307920. C.X. is supported by a grant from STScI under contract NAS 5-03127. S.K.B. is supported in part by an STScI Postdoctoral Fellowship. We acknowledge support from ESA through the ESA Space Science Faculty Visitor scheme, funding reference ESA-SCI-E-LE-109. K.W. and C.X.L. acknowledge that support for programme #2053 was provided by NASA through a grant from STScI, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under NASA contract NAS 5-03127.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.W. led the analysis and wrote the paper. K.W. performed the data reduction, PSF subtraction and CO modelling. C.H.C. is PI for the observing programme and helped with writing, analysis and interpretation. S.D.B., J.R.N., C.X.L. and I.R. assisted with the CO modelling and interpretation of the modelling results. C.X. and S.K.B. helped with the PSF subtraction, throughput correction and spectral extraction. T.B. and C.I. helped with the preprocessing of the data. A.M.H., C.M.L. and A.M.-M. helped with the interpretation of the modelling results and placing them in context with previous works. E.C. helped design the observing programme.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Astronomy thanks Gianni Cataldi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

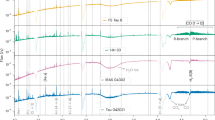

Extended Data Fig. 1 Comparison of east and west sides of disk.

a. normalized spectra extracted from a projected distance of 55 au from the east (black) and west (red) sides of the disk. The spectra are normalized to compare their shapes on the opposite sides of the disk. Note that the absolute flux values of the spectra on opposite sides of the disk differ at a less than ~5% ( < 2\(\sigma\)) level. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation. b. same as left but for the projected distance of 80 au. c. same as left but for the projected distance of 100 au.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Discussion and Figs. 1–10.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Worthen, K., Chen, C.H., Brittain, S.D. et al. Fluorescently excited CO emission in the 49 Ceti debris disk spatially resolved by JWST/NIRSpec. Nat Astron 9, 1680–1691 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02664-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02664-x