Abstract

Observations by the James Webb Space Telescope have uncovered supermassive black holes with masses exceeding 106 M⊙ at redshifts z > 8, posing serious challenges to existing models of early black hole formation and growth. Here we show, in a fully cosmological setting, that light seed black holes, remnants of population III stars, can grow rapidly to ~104 M⊙ in the early Universe. This growth is enabled by our new black hole seeding prescription and the unprecedented resolution of our zoom-in cosmological simulations, which resolve the dense environments necessary for efficient accretion. Our results provide robust evidence that light seed black holes can attain the masses required to serve as the dominant progenitors of the population of supermassive black holes observed at later cosmic epochs. These findings have far-reaching implications for the interpretation of observations by the James Webb Space Telescope and future gravitational wave detections with LISA.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The simulation outputs generated and analysed in this study amount to approximately 6 TB and cannot be hosted in a public repository due to their size. These data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, and we will provide the full set of snapshots and derived data products necessary to reproduce the analyses presented in the paper. Summary products required for figure generation (BH growth histories, gas properties, halo catalogues and extracted time series) are available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30857603 (ref. 79). Source data are available with this paper.

Code availability

The simulations were carried out with a proprietary version of the publicly available Arepo code. The publicly released version of Arepo can be obtained from the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics (https://arepo-code.org). The modified, proprietary version used for our production runs cannot be redistributed. All analysis scripts developed for this study—including routines for processing the snapshots, computing derived quantities, and generating the figures—are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17894541 (ref. 80).

References

Madau, P. & Rees, M. J. Massive black holes as population III remnants. Astrophys. J. Lett. 551, L27–L30 (2001).

Volonteri, M., Haardt, F. & Madau, P. The assembly and merging history of supermassive black holes in hierarchical models of galaxy formation. Astrophys. J. 582, 559–573 (2003).

Madau, P., Rees, M. J., Volonteri, M., Haardt, F. & Oh, S. P. Early reionization by miniquasars. Astrophys. J. 604, 484–494 (2004).

Volonteri, M. The formation and evolution of massive black holes. Science 337, 544 (2012).

Latif, M. A., Whalen, D. & Khochfar, S. The birth mass function of population III stars. Astrophys. J. 925, 28 (2022).

Abel, T., Bryan, G. L. & Norman, M. L. The formation of the first star in the Universe. Science 295, 93–98 (2002).

Bromm, V., Coppi, P. S. & Larson, R. B. The formation of the first stars. I. The primordial star-forming cloud. Astrophys. J. 564, 23–51 (2002).

O’Shea, B. W. & Norman, M. L. Population III star formation in a ΛCDM Universe. II. Effects of a photodissociating background. Astrophys. J. 673, 14–33 (2008).

Turk, M. J., Abel, T. & O’Shea, B. The formation of population III binaries from cosmological initial conditions. Science 325, 601 (2009).

Hirano, S. et al. One hundred first stars: protostellar evolution and the final masses. Astrophys. J. 781, 60 (2014).

Prole, L. R. et al. From dark matter halos to pre-stellar cores: high resolution follow-up of cosmological Lyman-Werner simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 520, 2081–2093 (2023).

Woosley, S. E. & Weaver, T. A. The evolution and explosion of massive stars. II. Explosive hydrodynamics and nucleosynthesis. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 101, 181 (1995).

Nomoto, K., Tominaga, N., Umeda, H., Kobayashi, C. & Maeda, K. Nucleosynthesis yields of core-collapse supernovae and hypernovae, and galactic chemical evolution. Nucl. Phys. A 777, 424–458 (2006).

Heger, A. & Woosley, S. E. The nucleosynthetic signature of population III. Astrophys. J. 567, 532–543 (2002).

Lupi, A. et al. Growing massive black holes through supercritical accretion of stellar-mass seeds. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 456, 2993–3003 (2016).

Smith, B. D. et al. The growth of black holes from population III remnants in the Renaissance simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 480, 3762–3773 (2018).

Regan, J. A. et al. Super-Eddington accretion and feedback from the first massive seed black holes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 486, 3892–3906 (2019).

Sassano, F., Capelo, P. R., Mayer, L., Schneider, R. & Valiante, R. Super-critical accretion of medium-weight seed black holes in gaseous proto-galactic nuclei. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 519, 1837–1855 (2023).

Inayoshi, K., Haiman, Z. & Ostriker, J. P. Hyper-Eddington accretion flows on to massive black holes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 459, 3738–3755 (2016).

Jiang, Y.-F., Stone, J. M. & Davis, S. W. Super-Eddington accretion disks around supermassive black holes. Astrophys. J. 880, 67 (2019).

Park, K., Wise, J. H., Bogdanovic, T. & Ricotti, M. Biconical-dominated accretion flow onto seed black holes in a hyperaccretion regime. Astrophys. J. 905, 92 (2020).

Kitaki, T., Mineshige, S., Ohsuga, K. & Kawashima, T. The origins and impact of outflow from super-Eddington flow. Publ. Astron. Soc. Jpn 73, 450–466 (2021).

Botella, I., Mineshige, S., Kitaki, T., Ohsuga, K. & Kawashima, T. Structure of the super-Eddington outflow and its impact on the cosmological scale. Publ. Astron. Soc. Jpn 74, 384–397 (2022).

Lambrides, E. et al. The case for super-Eddington accretion: connecting weak X-ray and UV line emission in JWST broad-line AGN during the first Gyr of cosmic time. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.13047 (2024).

Suh, H. et al. A super-Eddington-accreting black hole ~1.5 Gyr after the Big Bang observed with JWST. Nat. Astron. 9, 271–279 (2025).

Shi, Y., Kremer, K., Grudic, M. Y., Gerling-Dunsmore, H. J. & Hopkins, P. F. Hyper-Eddington black hole growth in star-forming molecular clouds and galactic nuclei: can it happen? Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 518, 3606–3621 (2023).

Gordon, S. T., Smith, B. D., Khochfar, S. & Regan, J. A. Hungry or not: how stellar-mass black holes grow (or don’t) in dark matter mini-haloes at high resolution. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 529, 604–627 (2024).

Mehta, D., Regan, J. A. & Prole, L. Growth of light-seed black holes in gas-rich galaxies at high redshift. Open J. Astrophys. 7, 107 (2024).

Alexander, T. & Natarajan, P. Rapid growth of seed black holes in the early Universe by supra-exponential accretion. Science 345, 1330–1333 (2014).

Zana, T. et al. Super-Eddington accretion in protogalactic cores. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.21114 (2025).

Alvarez, M. A., Wise, J. H. & Abel, T. Accretion onto the first stellar-mass black holes. Astrophys. J. Lett. 701, L133–L137 (2009).

Springel, V. E pur si muove: Galilean-invariant cosmological hydrodynamical simulations on a moving mesh. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 401, 791–851 (2010).

Pakmor, R. et al. Improving the convergence properties of the moving-mesh code AREPO. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 455, 1134–1143 (2016).

Hahn, O. & Abel, T. Multi-scale initial conditions for cosmological simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 415, 2101–2121 (2011).

Prole, L. R., Regan, J. A., Mehta, D., Coles, P. & Dayal, P. Primordial black holes in cosmological simulations: growth prospects for supermassive black holes. Open J. Astrophys. 8, 126 (2025).

Prole, L. R. et al. The SEEDZ simulations: methodology and first results on massive black hole seeding and early galaxy growth. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.09640 (2025).

Qin, Y., Mesinger, A., Park, J., Greig, B. & Munoz, J. B. A tale of two sites. I. Inferring the properties of minihalo-hosted galaxies from current observations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 495, 123–140 (2020).

Shi, Y., Kremer, K. & Hopkins, P. F. Feedback-regulated seed black hole growth in star-forming molecular clouds and galactic nuclei. Astron. Astrophys. 691, A24 (2024).

Gordon, S. T., Smith, B. D., Khochfar, S. & Beckmann, R. S. Conditions for super-Eddington accretion onto the first black holes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 537, 674–690 (2025).

Regan, J. A. et al. The formation of very massive stars in early galaxies and implications for intermediate mass black holes. Open J. Astrophys. 3, 15 (2020).

Jaura, O. et al. Trapping of H II regions in population III star formation. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 512, 116–136 (2022).

Volonteri, M., Silk, J. & Dubus, G. The case for supercritical accretion onto massive black holes at high redshift. Astrophys. J. 804, 148 (2015).

Jiang, Y.-F., Stone, J. M. & Davis, S. W. A global three-dimensional radiation magneto-hydrodynamic simulation of super-Eddington accretion disks. Astrophys. J. 796, 106 (2014).

Tremmel, M., Governato, F., Volonteri, M. & Quinn, T. R. Off the beaten path: a new approach to realistically model the orbital decay of supermassive black holes in galaxy formation simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 451, 1868–1874 (2015).

Pfister, H., Volonteri, M., Dubois, Y., Dotti, M. & Colpi, M. The erratic dynamical life of black hole seeds in high-redshift galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 486, 101–111 (2019).

Taylor, P. & Kobayashi, C. Seeding black holes in cosmological simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 442, 2751–2767 (2014).

Habouzit, M., Volonteri, M. & Dubois, Y. Blossoms from black hole seeds: properties and early growth regulated by supernova feedback. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 468, 3935–3948 (2017).

Bhowmick, A. K. et al. Introducing the BRAHMA simulation suite: signatures of low-mass black hole seeding models in cosmological simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 531, 4311–4335 (2024).

Pérez-González, P. G. et al. What Is the nature of little red dots and what is not, MIRI SMILES Edition. Astrophys. J. 968, 4 (2024).

Kokorev, V. et al. A census of photometrically selected little red dots at 4 < z < 9 in JWST blank fields. Astrophys. J. 968, 38 (2024).

Springel, V., Pakmor, R., Zier, O. & Reinecke, M. Simulating cosmic structure formation with the GADGET-4 code. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 506, 2871–2949 (2021).

Bourne, M. A., Fiacconi, D., Sijacki, D., Piotrowska, J. M. & Koudmani, S. Dynamics and spin alignment in massive, gravito-turbulent circumbinary discs around supermassive black hole binaries. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 534, 3448–3477 (2024).

Planck Collaboration Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 641, A6 (2020).

Wollenberg, K. M. J., Glover, S. C. O., Clark, P. C. & Klessen, R. S. Formation sites of population III star formation: effects of rotation and turbulence on fragmentation. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 494, 1871–1893 (2020).

Tress, R. G. et al. Simulations of the Milky Way’s central molecular zone. I. Gas dynamics. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 499, 4455–4478 (2020).

Krumholz, M. R., McKee, C. F. & Klein, R. I. Embedding Lagrangian sink particles in Eulerian grids. Astrophys. J. 611, 399–412 (2004).

Bryan, G. L. et al. ENZO: an adaptive mesh refinement code for astrophysics. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 211, 19 (2014).

Regan, J. A. & Downes, T. P. Rise of the first supermassive stars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 478, 5037–5049 (2018).

Brummel-Smith, C. et al. ENZO: an adaptive mesh refinement code for astrophysics (version 2.6). J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1636 (2019).

Truelove, J. et al. The Jeans condition: a new constraint on spatial resolution in simulations of isothermal self-gravitational hydrodynamics. Astrophys. J. 489, L179 (1997).

Maeder, A. Physics, Formation and Evolution of Rotating Stars (Springer, 2009).

Gatto, A. et al. Modelling the supernova-driven ISM in different environments. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 449, 1057–1075 (2015).

Magg, M. et al. Metal mixing in minihalos: the descendants of pair-instability supernovae. Astrophys. J. 929, 119 (2022).

Smith, M. C., Sijacki, D. & Shen, S. Cosmological simulations of dwarfs: the need for ISM physics beyond SN feedback alone. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 485, 3317–3333 (2019).

Bondi, H. On spherically symmetrical accretion. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 112, 195 (1952).

Krumholz, M. R., McKee, C. F. & Klein, R. I. Bondi–Hoyle accretion in a turbulent medium. Astrophys. J. 638, 369–381 (2006).

Di Matteo, T., Springel, V. & Hernquist, L. Energy input from quasars regulates the growth and activity of black holes and their host galaxies. Nature 433, 604–607 (2005).

Springel, V., Di Matteo, T. & Hernquist, L. Modelling feedback from stars and black holes in galaxy mergers. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 361, 776–794 (2005).

Sijacki, D., Springel, V., Di Matteo, T. & Hernquist, L. A unified model for AGN feedback in cosmological simulations of structure formation. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 380, 877–900 (2007).

Di Matteo, T., Colberg, J., Springel, V., Hernquist, L. & Sijacki, D. Direct cosmological simulations of the growth of black holes and galaxies. Astrophys. J. 676, 33–53 (2008).

Sadowski, A., Lasota, J.-P., Abramowicz, M. A. & Narayan, R. Energy flows in thick accretion discs and their consequences for black hole feedback. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 456, 3915–3928 (2016).

Abramowicz, M. A. & Fragile, P. C. Foundations of black hole accretion disk theory. Living Rev. Relativ. 16, 1 (2013).

Madau, P., Haardt, F. & Dotti, M. Super-critical growth of massive black holes from stellar-mass seeds. Astrophys. J. Lett. 784, L38 (2014).

Dalla Vecchia, C. & Schaye, J. Simulating galactic outflows with thermal supernova feedback. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 426, 140–158 (2012).

Prole, L. R., Clark, P. C., Klessen, R. S. & Glover, S. C. O. Fragmentation-induced starvation in population III star formation: a resolution study. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 510, 4019–4030 (2022).

Hartwig, T., Glover, S. C. O., Klessen, R. S., Latif, M. A. & Volonteri, M. How an improved implementation of H2 self-shielding influences the formation of massive stars and black holes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 452, 1233–1244 (2015).

Clark, P. C. et al. The formation and fragmentation of disks around primordial protostars. Science 331, 1040 (2011).

Schauer, A. T. P., Regan, J., Glover, S. C. O. & Klessen, R. S. The formation of direct collapse black holes under the influence of streaming velocities. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 471, 4878–4884 (2017).

Mehta, D. H., Regan, J. A. & Prole, L. Analysis datasets for Mehta et al. 202X. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30857603 (2025).

Mehta, D. H., Regan, J. A. & Prole, L. Analysis pipeline for Mehta et al. 202X. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17894541 (2025).

Acknowledgements

J.A.R. acknowledges support from the Royal Society and Research Ireland (Grant No. URF/R1/191132). D.H.M., J.A.R. and L.P. acknowledge support from the Research Ireland Laureate programme (Grant No. IRCLA/2022/1165). The simulations were performed on the Czech Republic EuroHPC machine Karolina hosted by IT4Innovations through a EuroHPC Regular Access call (EHPC-REG-2023R03-103, EHPC-REG-2025R01-008) and on the Luxembourg machine Meluxina. We acknowledge the Irish Centre for High-End Computing for the provision of computational facilities and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.H.M., J.A.R. and L.P. conceived the idea for the project. D.H.M. performed the simulation and analysis and drafted the paper. J.A.R. performed the coarse 40-Mpc simulations. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and to the text of the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Astronomy thanks Aklant Bhowmick and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Population density of PopIII stars.

We show the IMF of PopIII stars from all our simulations. The simulations L13, L14, L15 and L15_BHFB are coloured red, blue, violet and yellow respectively. This is the top-heavy IMF with a characteristic mass of 20 M⊙. The minimum mass of PopIII stars in 1 and the maximum mass is 300 M⊙.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Mass function of halos and galaxies.

We show the number of halos (dashed lines) identified through the FOF algorithm across each of our simulations. The simulations L13, L14, L15 and L15_BHFB are coloured red, blue, violet and yellow respectively. We also highlight the number of galaxies (solid lines) within the halos that went on to have star formation and host BHs. We do not count here halos with mass 105 M⊙. We find that with increasing resolution, star formation begins in smaller and smaller galaxies.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Final mass of BHs vs initial mass of their PopIII progenitor stars.

We show the final masses of BHs as a function of their progenitor PopIII stars. All black dots are BHs that grew larger than their progenitor mass while red dots are BHs that did not accrete any gas. The shaded patch in yellow denotes the BH formed after undergoing a Type-II supernova. The shaded purple patch is for PISN, so there are no BH remnants. While in the white patch are BHs formed through the direct collapse channel. Interestingly, all of the BHs that grow formed through the direct collapse channel.

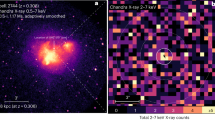

Extended Data Fig. 4 Gas temperature projection for PopIII star formation, supernova feedback, and BH feedback for the most massive BH in the L15_BHFB simulations.

a, b, c: Gas collapses to form cold galaxies in hot cosmic filaments. Within these galaxies, PopIII star formation occurs. d: The first PopIII star transitions to a BH and accretes the surrounding mass, simultaneously injecting thermal energy back into the gas. This thermal energy causes the galaxy to be distorted. e: The galaxy eventually reassembles triggering a second epoch of star formation. f: SNe from PopIII stars and BH thermal feedback heats up the gas to 105 K, which halts further BH growth and star formation.

Extended Data Fig. 5 BH particle growth plots.

We show the growth of BH particles with time after they transition from PopIII particles for BHs that accreted more than 0.1 M⊙ (dashed) and BHs that doubled their initial mass (solid lines). The simulations L13, L14, L15 and L15_BHFB are coloured red, blue, violet and yellow respectively. On average, we the find the growth phase lasting around a million years. We also see a trend that with increasing resolution, the timescales shorten.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Average metallicity of gas surrounding the BHs.

We show the average metallicity of gas surrounding the BHs during its entire growth phase. The simulations L13, L14, L15 and L15_BHFB are coloured red, blue, violet and yellow respectively. In our simulations, we have a metallicity floor of 10−10 Z⊙. We have a subset of BHs growing in pristine metal-free conditions, but we also see growth of BHs in galaxies enriched with metals.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Relation between BH growth and halo properties.

a: We show the final masses of BHs (Mf) as a function of its host halo mass. The simulations L13, L14, L15 and L15_BHFB are coloured red, blue, violet and yellow respectively. The dots show BHs that accreted more than 0.1 M⊙ and crosses focus on BHs that accreted more than their initial mass (Mi). We see no correlation between the two, suggesting that the halo does not need to be special in order for BHs to grow. b: We see a similar result when comparing the final masses with surface density of gas surrounding the BHs. However, we are incomplete in sampling larger halo masses and it is possible, even likely, that more massive halos would support additional growth and will also likely support the growth of LSBHs which have already experienced previous growth episodes.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Impact of radiation pressure on BH Growth.

We show the fraction of inward gas momentum against the outward radiation pressure flux for all BHs that accreted more than a thousand M⊙. Similar to our feedback simulation L15_BHFB, we find growth possible for a small subset of LSBHs.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Number density of MBHs and galaxies in our simulations.

We show the number density evolution of BHs above 1000 M⊙ (solid lines) along with the galaxy (dashed lines) number density. The simulations L13, L14, L15 and L15_BHFB are coloured red, blue, violet and yellow respectively. The plot highlights one of our results, that increasing resolution helps us capture LSBH growth. The number density of BHs reaches almost 100 cMpc−3 for the L15 simulation. In the L15_BHFB simulation, the number density decreases to below 20 cMpc−3, which is still much larger than the number density of the high-z AGN populations ≲ 10−2 cMpc−3, making LSBHs promising progenitors for SMBHs.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data (also uploaded to a separate repository 10.5281/zenodo.17899001).

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data (also uploaded to a separate repository 10.5281/zenodo.17899001).

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data (also uploaded to a separate repository 10.5281/zenodo.17899001).

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data (also uploaded to a separate repository 10.5281/zenodo.17899001).

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mehta, D.H., Regan, J.A. & Prole, L. The growth of light seed black holes in the early Universe. Nat Astron (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02767-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02767-5