Abstract

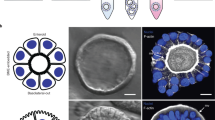

Organoids for modelling the physiology and pathology of gastrointestinal tissues are constrained by a poorly accessible lumen. Here we report the development and applicability of bilaterally accessible organoid-derived patterned epithelial monolayers that allow the independent manipulation of their apical and basal sides. We constructed gastric, small-intestinal, caecal and colonic epithelial models that faithfully reproduced their respective tissue geometries and that exhibited stem cell regionalization and transcriptional resemblance to in vivo epithelia. The models’ enhanced observability allowed single-cell tracking and studies of the motility of cells in immersion culture and at the air–liquid interface. Models mimicking infection of the caecal epithelium by the parasite Trichuris muris allowed us to live image syncytial tunnel formation. The enhanced observability of bilaterally accessible organoid-derived gastrointestinal tissue will facilitate the study of the dynamics of epithelial cells and their interactions with pathogens.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The main data supporting the results in this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. RNA sequencing source data are available from the Gene Expression Omnibus repository via the accession code GSE241012.

Code availability

Custom analysis code is available from the corresponding authors on request.

Change history

20 January 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-025-01351-6

References

Clevers, H. Modeling development and disease with organoids. Cell 165, 1586–1597 (2016).

Fatehullah, A., Tan, S. H. & Barker, N. Organoids as an in vitro model of human development and disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 246–254 (2016).

Lancaster, M. A. & Knoblich, J. A. Organogenesisin a dish: modeling development and disease using organoid technologies. Science 345, 1247125 (2014).

Sato, T. et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt–villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 459, 262–265 (2009).

Hofer, M. & Lutolf, M. P. Engineering organoids. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 402–420 (2021).

Boccellato, F. et al. Polarised epithelial monolayers of the gastric mucosa reveal insights into mucosal homeostasis and defence against infection. Gut 68, 400–413 (2019).

Liu, Y., Qi, Z., Li, X., Du, Y. & Chen, Y. G. Monolayer culture of intestinal epithelium sustains Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells. Cell Discov. 4, 4–6 (2018).

VanDussen, K. L. et al. Development of an enhanced human gastrointestinal epithelial culture system to facilitate patient-based assays. Gut 64, 911–920 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Long-term culture captures injury–repair cycles of colonic stem cells. Cell 179, 1144–1159.e15 (2019).

Roodsant, T. et al. A human 2D primary organoid-derived epithelial monolayer model to study host–pathogen interaction in the small intestine. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 10, 1–14 (2020).

Thorne, C. A. et al. Enteroid monolayers reveal an autonomous WNT and BMP circuit controlling intestinal epithelial growth and organization. Dev. Cell 44, 624–633.e4 (2018).

Jabaji, Z. et al. Use of collagen gel as an alternative extracellular matrix for the in vitro and in vivo growth of murine small intestinal epithelium. Tissue Eng. Part C 19, 961–969 (2013).

Duque-Correa, M. A. et al. Defining the early stages of intestinal colonisation by whipworms. Nat. Commun. 13, 1725 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Formation of human colonic crypt array by application of chemical gradients across a shaped epithelial monolayer. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 113–130 (2018).

Costello, C. M. et al. 3-D intestinal scaffolds for evaluating the therapeutic potential of probiotics. Mol. Pharm. 11, 2030–2039 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. A microengineered collagen scaffold for generating a polarized crypt-villus architecture of human small intestinal epithelium. Biomaterials 128, 44–55 (2017).

Creff, J. et al. Fabrication of 3D scaffolds reproducing intestinal epithelium topography by high-resolution 3D stereolithography. Biomaterials https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119404 (2019).

Verhulsel, M. et al. Developing an advanced gut on chip model enabling the study of epithelial cell/fibroblast interactions. Lab Chip 21, 365–377 (2021).

Gjorevski, N. et al. Tissue geometry drives deterministic organoid patterning. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw9021 (2022).

Nikolaev, M. et al. Homeostatic mini-intestines through scaffold-guided organoid morphogenesis. Nature 585, 574–578 (2020).

Barker, N. et al. Lgr5+ve stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell 6, 25–36 (2010).

Zhu, G., Hu, J. & Xi, R. The cellular niche for intestinal stem cells: a team effort. Cell Regen. 10, 1–16 (2021).

Casteleyn, C., Rekecki, A., Van Der Aa, A., Simoens, P. & Van Den Broeck, W. Surface area assessment of the murine intestinal tract as a prerequisite for oral dose translation from mouse to man. Lab Anim. 44, 176–183 (2010).

Choi, E. et al. Cell lineage distribution atlas of the human stomach reveals heterogeneous gland populations in the gastric antrum. Gut 63, 1711–1720 (2014).

Ootani, A., Toda, S., Fujimoto, K. & Sugihara, H. An air–liquid interface promotes the differentiation of gastric surface mucous cells (GSM06) in culture. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 271, 741–746 (2000).

Zhang, Y., Zeng, F., Han, X., Weng, J. & Gao, Y. Lineage tracing: technology tool for exploring the development, regeneration, and disease of the digestive system. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 11, 1–16 (2020).

Bartfeld, S. et al. In vitro expansion of human gastric epithelial stem cells and their responses to bacterial infection. Gastroenterology 148, 126–136.e6 (2015).

Co, J. Y. et al. Controlling epithelial polarity: a human enteroid model for host–pathogen interactions. Cell Rep. 26, 2509–2520.e4 (2019).

Dutta, D. & Clevers, H. Organoid culture systems to study host–pathogen interactions. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 48, 15–22 (2017).

White, R., Blow, F., Buck, A. H. & Duque-Correa, M. A. Organoids as tools to investigate gastrointestinal nematode development and host interactions. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 12, 1–9 (2022).

Duque-Correa, M. A., Maizels, R. M., Grencis, R. K. & Berriman, M. Organoids—new models for host–helminth interactions. Trends Parasitol. 36, 170–181 (2020).

Yousefi, Y., Haq, S., Banskota, S., Kwon, Y. H. & Khan, W. I. Trichuris muris model: role in understanding intestinal immune response, inflammation and host defense. Pathogens 10, 1–21 (2021).

Bancroft, A. J. et al. The major secreted protein of the whipworm parasite tethers to matrix and inhibits interleukin-13 function. Nat Commun. 10, 2344 (2019).

Panesar, T. S. & Croll, N. A. The location of parasites within their hosts: site selection by Trichuris muris in the laboratory mouse. Int J. Parasitol. 10, 261–273 (1980).

Gjorevski, N. et al. Designer matrices for intestinal stem cell and organoid culture. Nature 539, 560–564 (2016).

Ramanujan, S. et al. Diffusion and convection in collagen gels: implications for transport in the tumor interstitium. Biophys. J. 83, 1650–1660 (2002).

Miyoshi, H. & Stappenbeck, T. S. In vitro expansion and genetic modification of gastrointestinal stem cells in spheroid culture. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2471–2482 (2013).

Bartfeld, S. & Clevers, H. Organoids as model for infectious diseases: culture of human and murine stomach organoids and microinjection of Helicobacter pylori. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/53359 (2015)

Duque-Correa, M. A. et al. Development of caecaloids to study host-pathogen interactions: new insights into immunoregulatory functions of Trichuris muris extracellular vesicles in the caecum. Int. J. Parasitol. 50, 707–718 (2020).

Nik, A. M. & Carlsson, P. Separation of intact intestinal epithelium from mesenchyme. Biotechniques 55, 42–44 (2013).

Stirling, D. R. et al. CellProfiler 4: improvements in speed, utility and usability. BMC Bioinf. 22, 1–11 (2021).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Chen, Y., Lun, A. T. L. & Smyth, G. K. From reads to genes to pathways: differential expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments using Rsubread and the edgeR quasi-likelihood pipeline. F1000Research. 5, 1–51 (2016).

Pachitariu, M. & Stringer, C. Cellpose 2.0: how to train your own model. Nat. Methods 19, 1634–1641 (2022).

Tinevez, J. Y. et al. TrackMate: an open and extensible platform for single-particle tracking. Methods 115, 80–90 (2017).

Berg, S. et al. ilastik: interactive machine learning for (bio)image analysis. Nat. Methods 16, 1226–1232 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Sharma from the Laboratory of John McKinney (EPFL) and A. Widmer from the EPFL Organ/Tissue Sharing Program for providing cadavers of mice and R. Grencis (University of Manchester) for the p43 antibody. We thank M. Nikolaev for help producing the microfabricated moulds for stamps, S. Li for help generating colonic organoids, T. Hübscher, A. Chrisnandy and B. Sen Elci for valuable discussions and primers and J. Prébandier, L. Tillard and C. Tolley for administrative and technical support. We acknowledge support from CMi, BIOP, GECF, FCCF and HCF EPFL core facilities. This work was funded by the National Center of Competence in Research Bio-Inspired Materials, the EU Horizon 2020 research programme INTENS (www.intens.info; no. 668294-2) and the Swiss National Science Foundation research grant no. 310030_179447. This work was supported by the Sir Henry Dale Fellowship jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (222546/Z/21/Z, M.A.D.-C.) and the Wellcome Trust (203151/A/16/Z, M.A.D.-C.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H. and M.P.L. conceived the study, designed experiments, interpreted data and wrote the paper. M.H. conducted all experiments and analysis. M.A.D.-C. proposed and supervised T. muris infection experiments, provided T. muris eggs, contributed to data interpretation and edited the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.P.L. is an employee of Hoffmann-La Roche. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Biomedical Engineering thanks Martin Beaumont and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary figures, tables and video captions.

Supplementary Video 1

Animated confocal live-acquired stack images of stomach, small intestine, caecum and colon transgel organoids.

Supplementary Video 2

Cellular motility of gastric transgel organoids in IMM and ALI cultures.

Supplementary Video 3

Infection of T. muris larvae on caecal transgel organoids.

Supplementary Video 4

T. muris larvae moving through epithelium by tunnel formation.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hofer, M., Duque-Correa, M.A. & Lutolf, M.P. Patterned gastrointestinal monolayers with bilateral access as observable models of parasite gut infection. Nat. Biomed. Eng 9, 1075–1085 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-024-01313-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-024-01313-4

This article is cited by

-

Biomimetic culture substrates for modelling homeostatic intestinal epithelium in vitro

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Decoding host-microbe interactions with engineered human organoids

The EMBO Journal (2025)

-

Human organoids as 3D in vitro platforms for drug discovery: opportunities and challenges

Nature Reviews Drug Discovery (2025)

-

Accessible homeostatic gastric organoids reveal secondary cell type-specific host-pathogen interactions in Helicobacter pylori infections

Nature Communications (2025)