Abstract

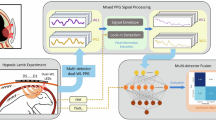

Fetal surgery offers valuable opportunities to address severe congenital disabilities, yet accurate evaluation of fetal physiological changes during in utero procedures to mitigate the risk of operative complications remains an unmet need. Conventional unimodal approaches lack predictive value, specificity and compatibility with minimally invasive interventions. Here we present a bioelectronic system featuring a multimodal, steerable filamentary probe that interfaces directly with the fetus in utero, enabling reliable and minimally invasive monitoring of various physiological parameters. Integrated soft robotic actuators ensure consistent contact through controlled navigation and force delivery, creating a gentle and secure interface with delicate fetal surfaces. In a sheep fetal surgery model, the multifunctional probe effectively monitored in utero conditions during fetoscopic surgeries, detecting fetal bradycardia, hypoxia and hypothermia, potentially informing for early intervention. Experimental results on rodents and large animal fetuses demonstrate potential for direct translation to human use. This system offers continuous, comprehensive fetal monitoring, addressing gaps in current clinical practices, and provides real-time insights during fetal surgeries.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request. The analysed data are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17371614 (ref. 71). Source data that support the findings of this study are included within this paper and its Supplementary Information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All computer code and customized software generated during and/or used in the current study are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17371614 (ref. 71).

References

CDC. Birth defects (2024); https://www.cdc.gov/birth-defects/data-research/facts-stats/index.html

Parker, S. E. et al. Updated national birth prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004–2006. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 88, 1008–1016 (2010).

Mai, C. T. et al. National population-based estimates for major birth defects, 2010–2014. Birth Defects Res. 111, 1420–1435 (2019).

Wilson, R. D. In utero therapy for fetal thoracic abnormalities. Prenat. Diagn. 28, 619–625 (2008).

Warner, L. L., Arendt, K. W., Ruano, R., Qureshi, M. Y. & Segura, L. G. A call for innovation in fetal monitoring during fetal surgery. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 35, 1817–1823 (2022).

Pinas, A. & Chandraharan, E. Continuous cardiotocography during labour: analysis, classification and management. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 30, 33–47 (2016).

Alfirevic, Z., Devane, D. & Gyte, G. M. Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd006066.pub2 (2013).

Neilson, J. P. Fetal electrocardiogram (ECG) for fetal monitoring during labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, CD000116 (2015).

Symonds, E. M., Sahota, D. & Chang, A. Fetal Electrocardiography. Cardiopulmonary Medicine from Imperial College Press (Imperial College Press, 2001).

Behar, J. A. et al. Noninvasive fetal electrocardiography for the detection of fetal arrhythmias. Prenat. Diagn. 39, 178–187 (2019).

Kahankova, R. et al. A review of recent advances and future developments in fetal phonocardiography. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 16, 653–671 (2023).

Adithya, P. C., Sankar, R., Moreno, W. A. & Hart, S. Trends in fetal monitoring through phonocardiography: challenges and future directions. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 33, 289–305 (2017).

Wacker-Gussmann, A., Strasburger, J. F. & Wakai, R. T. Contribution of fetal magnetocardiography to diagnosis, risk assessment, and treatment of fetal arrhythmia. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 11, e025224 (2021).

Strasburger, J. F., Cheulkar, B. & Wakai, R. T. Magnetocardiography for fetal arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm 5, 1073–1076 (2008).

Reuss, J. L. Factors influencing fetal pulse oximetry performance. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 18, 13–24 (2004).

East, C. E., Begg, L., Colditz, P. B. & Lau, R. Fetal pulse oximetry for fetal assessment in labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, CD004075 (2014).

Donofrio, M. T. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of fetal cardiac disease. Circulation 129, 2183–2242 (2014).

Strasburger, J. F. & Wakai, R. T. Fetal cardiac arrhythmia detection and in utero therapy. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 7, 277–290 (2010).

Engwall-Gill, A. J. & Perrone, E. E. in Pediatric Surgery (eds Coppola, C. P. et al.) 263–272 (Springer, 2022).

Kohl, T. Minimally invasive fetoscopic interventions: an overview in 2010. Surg. Endosc. 24, 2056–2067 (2010).

Ouyang, W. et al. A wireless and battery-less implant for multimodal closed-loop neuromodulation in small animals. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 7, 1252–1269 (2023).

McCall, J. G. et al. Fabrication and application of flexible, multimodal light-emitting devices for wireless optogenetics. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2413–2428 (2013).

Gutruf, P. et al. Fully implantable optoelectronic systems for battery-free, multimodal operation in neuroscience research. Nat. Electron. 1, 652–660 (2018).

Cianchetti, M., Laschi, C., Menciassi, A. & Dario, P. Biomedical applications of soft robotics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 143–153 (2018).

Konishi, S., Kobayashi, T., Maeda, H., Asajima, S. & Makikawa, M. Cuff actuator for adaptive holding condition around nerves. Sens. Actuators B 83, 60–66 (2002).

Runciman, M., Darzi, A. & Mylonas, G. P. Soft robotics in minimally invasive surgery. Soft Robot. 6, 423–443 (2019).

Kim, Y., Parada, G. A., Liu, S. & Zhao, X. Ferromagnetic soft continuum robots. Sci. Robot. 4, 33 (2019).

Marechal, L. et al. Toward a common framework and database of materials for soft robotics. Soft Robot. 8, 284–297 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Liao, J., Chen, M., Li, X. & Jin, G. A multi-module soft robotic arm with soft actuator for minimally invasive surgery. Int. J. Med. Robot. Comput. Assist. Surg. 19, e2467 (2023).

Coutrot, M. et al. Perfusion index: physical principles, physiological meanings and clinical implications in anaesthesia and critical care. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 40, 100964 (2021).

Elgendi, M. Optimal signal quality index for photoplethysmogram signals. Bioengineering 3, 21 (2016).

McCauley, M. D. & Wehrens, X. H. T. Ambulatory ECG recording in mice. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/1739 (2010).

Fenske, S. et al. Comprehensive multilevel in vivo and in vitro analysis of heart rate fluctuations in mice by ECG telemetry and electrophysiology. Nat. Protoc. 11, 61–86 (2016).

Hennis, K. et al. In vivo and ex vivo electrophysiological study of the mouse heart to characterize the cardiac conduction system, including atrial and ventricular vulnerability. Nat. Protoc. 17, 1189–1222 (2022).

Chehbani, A., Sahuguede, S., Julien-Vergonjanne, A. & Bernard, O. Quality indexes of the ECG signal transmitted using optical wireless link. Sensors 23, 4522 (2023).

Rahman, S., Karmakar, C., Natgunanathan, I., Yearwood, J. & Palaniswami, M. Robustness of electrocardiogram signal quality indices. J. R. Soc. Interface 19, 20220012 (2022).

Wang, Y., Qu, Z., Wang, W. & Yu, D. PVA/CMC/PEDOT:PSS mixture hydrogels with high response and low impedance electronic signals for ECG monitoring. Colloids Surf. B 208, 112088 (2021).

Versek, C., Frasca, T., Zhou, J., Chowdhury, K. & Sridhar, S. Electric field encephalography for brain activity monitoring. J. Neural Eng. 15, 046027 (2018).

Rosell, J., Colominas, J., Riu, P., Pallas-Areny, R. & Webster, J. G. Skin impedance from 1 Hz to 1 MHz. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 35, 649–651 (1988).

Goyal, K., Borkholder, D. A. & Day, S. W. Dependence of skin-electrode contact impedance on material and skin hydration. Sensors 22, 8510 (2022).

Lee, S. Y. et al. Evolution and variations of the ovine model of spina bifida. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 50, 491–500 (2023).

Rosén, K. G., Hökegård, K. H. & Kjellmer, I. A study of the relationship between the electrocardiogram and hemodynamics in the fetal lamb during asphyxia. Acta Physiol. Scand. 98, 275–284 (1976).

Westgate, J. A. et al. Do fetal electrocardiogram PR-RR changes reflect progressive asphyxia after repeated umbilical cord occlusion in fetal sheep? Pediatr. Res. 44, 297–303 (1998).

Marwan, A. & Crombleholme, T. M. The EXIT procedure: principles, pitfalls, and progress. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 15, 107–115 (2006).

Spiers, A., Legendre, G., Biquard, F., Descamps, P. & Corroenne, R. Ex utero intrapartum technique (EXIT): indications, procedure methods and materno-fetal complications—a literature review. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 51, 102252 (2022).

Chen, G., Zhu, Z., Liu, J. & Wei, W. Esophageal pulse oximetry is more accurate and detects hypoxemia earlier than conventional pulse oximetry during general anesthesia. Front. Med. 6, 406–410 (2012).

Phillips, J. P., Kyriacou, P. A., Jones, D. P., Shelley, K. H. & Langford, R. M. Pulse oximetry and photoplethysmographic waveform analysis of the esophagus and bowel. Curr. Opin. Anesthesiol. 21, 779 (2008).

Varcoe, T. J. et al. Fetal cardiovascular response to acute hypoxia during maternal anesthesia. Physiol. Rep. 8, e14365 (2020).

Fong, D. D. et al. Validation of a novel transabdominal fetal oximeter in a hypoxic fetal lamb model. Reprod. Sci. 27, 1960–1966 (2020).

Park, J., Seok, H. S., Kim, S.-S. & Shin, H. Photoplethysmogram analysis and applications: an integrative review. Front. Physiol. 12, 808451 (2022).

Elgendi, M. On the analysis of fingertip photoplethysmogram signals. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 8, 14–25 (2012).

Abushouk, A. et al. The dicrotic notch: mechanisms, characteristics, and clinical correlations. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 25, 807–816 (2023).

Inoue, N. et al. Second derivative of the finger photoplethysmogram and cardiovascular mortality in middle-aged and elderly Japanese women. Hypertens. Res. 40, 207–211 (2017).

Hashimoto, J. et al. Pulse wave velocity and the second derivative of the finger photoplethysmogram in treated hypertensive patients: their relationship and associating factors. J. Hypertens. 20, 2415–2422 (2022).

Street, P., Dawes, G. S., Moulden, M. & Redman, C. W. G. Short-term variation in abnormal antenatal fetal heart rate records. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 165, 515–523 (1991).

Young, B. K., Katz, M. & Wilson, S. J. Sinusoidal fetal heart rate. I. Clinical significance. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 136, 587–593 (1980).

Partridge, E. A. et al. An extra-uterine system to physiologically support the extreme premature lamb. Nat. Commun. 8, 15112 (2017).

Kabagambe, S. K. et al. Lessons from the barn to the operating suite: a comprehensive review of animal models for fetal surgery. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 6, 1–21 (2017).

Petersen, R., Connelly, A., Martin, S. L. & Kupper, L. L. Preventive counseling during prenatal care: Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS). Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 56, 599–601 (2001).

Veena, S. & Aravindhar, D. J. Remote monitoring system for the detection of prenatal risk in a pregnant woman. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 119, 1051–1064 (2021).

Haga, Y. et al. Small diameter hydraulic active bending catheter using laser processed super elastic alloy and silicone rubber tube. In 2005 3rd IEEE/EMBS Special Topic Conference on Microtechnology in Medicine and Biology 245–248 (2005).

Liao, Z. et al. On the stress recovery behaviour of Ecoflex silicone rubbers. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 206, 106624 (2021).

Fung, Y.-C. in Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues 321–391 (Springer, 1993).

Fang, Q. & Boas, D. A. Monte Carlo simulation of photon migration in 3D turbid media accelerated by graphics processing units. Opt. Express 17, 20178–20190 (2009).

Yu, L., Nina-Paravecino, F., Kaeli, D. & Fang, Q. Scalable and massively parallel Monte Carlo photon transport simulations for heterogeneous computing platforms. J. Biomed. Opt. 23, 010504–010504 (2018).

Lu, W. et al. Wireless, implantable catheter-type oximeter designed for cardiac oxygen saturation. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe0579 (2021).

Bosschaart, N., Edelman, G. J., Aalders, M. C. G., Leeuwen, T. G. V. & Faber, D. J. A literature review and novel theoretical approach on the optical properties of whole blood. Lasers Med. Sci. 29, 453–479 (2014).

Khan, R., Gul, B., Khan, S., Nisar, H. & Ahmad, I. Refractive index of biological tissues: review, measurement techniques, and applications. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 33, 102192 (2021).

Morrison, J. L. et al. Improving pregnancy outcomes in humans through studies in sheep. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 315, R1123–R1153 (2018).

Joyeux, L. et al. Validation of the fetal lamb model of spina bifida. Sci. Rep. 9, 9327 (2019).

Zhou, J. et al. Data and code for the article ‘A filamentary soft robotic probe for multimodal in utero monitoring of fetal health’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17371614 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Querrey-Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics. In vivo studies were supported by the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital Foundation. This work made use of the NUFAB facility of Northwestern University’s NUANCE Center, which has received support from the SHyNE Resource (NSF ECCS-2025633), the IIN and Northwestern’s MRSEC programme (NSF DMR-2308691). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: H.B., J.Z., A.F.S. and J.A.R. Methodology: H.B., J.Z., S. Papastefan, X.L., A.F.S. and J.A.R. Theoretical simulations: X.L., H.Z. and Y.H. Investigation: H.B., J.Z., M.W., S. Papastefan, X.L., K.Z., Z.Z., W.O., C.R.R., A.M.A., H.W., Y.Z., K. Madsen, S.L., A.I.E., K. Ma, L.K., S. Patel, D.R.L., K.C.O., R.G., S.S., W.Z. and A.F.S. Software: J.Z. and W.O. Formal analysis: H.B., J.Z. and S. Papastefan. Validation: H.B., J.Z. and S. Papastefan. Data curation: H.B., J.Z., M.W. and S. Papastefan. Visualization: M.W., H.B., J.Z., S. Papastefan and X.L. Supervision: Y.H., A.F.S. and J.A.R. Funding acquisition: A.F.S. and J.A.R. Writing (original draft): H.B., J.Z., S. Papastefan and X.L. Writing (review and editing): J.Z., M.W., H.B., S. Papastefan, X.L., A.F.S. and J.A.R. H.B., J.Z., M.W., S. Papastefan and X.L. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Biomedical Engineering thanks Anna David, Ellen Roche and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1

Fabrication procedures of the 3D soft robotic actuator.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Finite element analysis of strain distribution on actuator layers.

(a) Overall strain distribution. (b) Strain distribution on the outer outer tear-resistant platinum-cure silicone elastomer (for example, DragonSkin-type, Smooth-On, Inc) layer. (c) Strain distribution on the low-modulus platinum-cure silicone (for example, Ecoflex-type, Smooth-On, Inc) chamber with enlarged views of critical edge leading to failure. (d) Strain distribution on polyimide strain limiting patterns. (e) Strain distribution on the copper layer of the probe.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Maximum strain on soft robotic structures during actuation.

(a) Left, FEA results showing cross-sectional strain distribution profile of silicone layers before and after flexion actuation. Scale bar, 1 mm. Arrows indicate the maximum strain points at the outer layer (orange) and chamber layer (blue). Right, maximum strain on different structures relative to the flexion angle. (b) Same as (a) but for torsion. (c) Same as (a) but for balloon inflation and inflation height.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Optimization of the outer layer thickness of the soft robotic actuator.

(a) Strain contour of flexion actuator with different outer layer thickness at a 180° flexion angle. (b) Simulation and experimental results of flexion angle with different outer layer thicknesses. (c) Strain contour of torsion actuator with different outer layer thickness at a 180° torsion angle. (d) Simulation and experiment result of torsion angle with different outer layer thickness. 120 µm, same data as load in Fig. 2d.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Numerical and experimental characterization of multimodal soft robotic actuator patterns.

(a) Strain contour of flexion actuator with different pattern gap widths at a 180° flexion angle. (b) Simulation and experimental results of flexion angle with different pattern gap width. (c) Strain contour of torsion actuator with different pattern angles at a 180° torsion angle. (d) Simulation and experimental results of torsion angle with different pattern angles.

Extended Data Fig. 6 ECG characteristics with different deployment approaches.

(a) Waveform and frequency spectrogram of ECG signal recorded from an adult mouse using SRFP with an epidermal approach. (b) Same as (a), but for the esophageal approach. (c) Same as (a), but for the rectal approach.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Validation of ECG signal detection in response to isoflurane euthanasia.

(a) Raw continuous ECG signals recorded during isoflurane euthanasia of an adult mouse using SRFP. (b) Frequency spectrum of recorded ECG signals during isoflurane euthanasia. (c) Calculated heart rate during isoflurane euthanasia.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Esophageal approach for physiological monitoring in a mouse model.

(a) Raw µ-IPD (Red and IR) signals showing esophageal PPG waveform recorded from an adult mouse. (b) Raw electrical signals showing esophageal ECG waveform recorded from an adult mouse.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Calibration of fetal SpO2 with cord blood gas analysis.

(a-b) Raw continuous µ-IPD signals during an ex-utero sheep fetal surgery. (c) The ratio R between the perfusion indices of red and IR µ-IPD signals. (d) Calibration of fetal SpO2 using linear regression between the perfusion index ratio R and arterial blood gas SaO2 values. (e) Computed physiological parameters, including calibrated SpO2, heart rate, and core temperature, during the same period of the experiment.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Esophageal approach for physiological monitoring during ex utero intrapartum treatment.

(a) Raw µ-IPD (Red and IR) signals showing the esophageal PPG waveform recorded from a sheep fetus. (b) PPG spectrogram (Red and IR) showing the esophageal PPG frequency recorded from a sheep fetus. (c) Calculated heart rate from esophageal PPG recording of a sheep fetus.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1–5, Table 1, Figs. 1–13 and Videos 1–6.

Supplementary Video 1

Injectable multimodal soft robotic fetal probe.

Supplementary Video 2

Probe securement with actuator expansion.

Supplementary Video 3

Soft robotic actuation in a tubular agarose gel phantom.

Supplementary Video 4

Probe steering in a branching agarose gel phantom.

Supplementary Video 5

Multimodal in utero monitoring during fetoscopic surgery.

Supplementary Video 6

Single-port soft robotic fetal probe deployment in a simulated human fetus.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Numerical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, H., Zhou, J., Wu, M. et al. A filamentary soft robotic probe for multimodal in utero monitoring of fetal health. Nat. Biomed. Eng (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-025-01605-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-025-01605-3