Abstract

The carbonyl group is one of the most important functional groups in organic chemistry. C=O cleavage and full transfer of the resulting fragments into final products would be extremely attractive and open up new avenues in retrosynthetic planning. In this context, as an N-containing carbonyl compound, the transformations of formamides, wherein C=O cleavage occurring with simultaneous incorporation of ‘O’ and aminomethine moieties to highly functionalized amines, remain a formidable challenge. Here we disclosed a dirhodium/Xantphos or dirhodium–palladium dual catalysed reaction of diazo compounds and allylic substrates in dimethyl formamide, giving various α-aminoketones and cyclopentenone derivatives efficiently featured with extensively reorganized structure, wherein a carbenic carbon was formally inserted into C=O bond and α-group of the carbene was shifted to the residual aminomethine moiety. Mechanistic studies revealed that three or six domino steps are involved in this catalytic process, including epoxidation, dyotropic type rearrangement, allylic alkylation, Claisen rearrangement, isomerization and Nazarov cyclization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

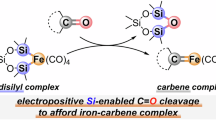

One of the most challenging tasks for current organic synthesis is to develop efficient and convenient strategies to rapidly increase structural complexity from easily available yet inert raw materials, especially for the catalytic domino reactions in the form of multi-component transformations in a single flask1,2,3. In this context, formamides are one of the most attractive basic chemicals owing to their ready availability, yet these compounds are typically inert as a result of resonance-stabilization (Fig. 1a). As an N-containing precursor, the transformation of formamide via cleavage of the C=O bond is regarded as one of the most challenging but highly rewarding topics in amine synthesis4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. A prototype formamide is dimethyl formamide (DMF), which is a widely used polar solvent with numerous applications. Moreover, in recent years, chemists have achieved important transformations using DMF as a multipurpose reagent in chemistry, delivering the groups, such as –CHO, –CO, –NMe2, and so on, to the products14,15,16. Although great progress has been achieved in this field, the long-standing difficulty in amide activation still calls for the development of new methodologies for the direct transformations of formamides involving C=O cleavage as both an oxygen source and a nitrogen source, especially in a multi-component domino reaction to access to structurally complex amines (Fig. 1b)17,18,19,20,21,22,23. In this way, the synthesis of biologically active and synthetically important α-aminoketone derivatives24,25,26,27 may be accomplished from formamides, which is highly desirable from the viewpoint of atom economy and structural complexity.

a, Formamide and its resonance stabilization. b, C=O cleavage and transfer. Transformations of formamides involving C=O cleavage as both an oxygen source and a nitrogen source are still less explored. c, Amide activation by metal carbenes via carbonyl ylides. d, Diazo compounds as carbene precursors in organic synthesis. The reconstruction of the molecular skeleton by cleavage of the carbene α C–C bond is still less developed. e, The multi-step domino reaction with the reconstitution of DMF and carbenes (this work). Full use of DMF; rearrangement of carbene α C–C bond; quick access to cyclopentenones, multi-step relay. Cat., catalyst. The red stars mark the transfer of the carbon atom of the amide carbonyl group. The yellow lightning bolt means cleavage of the amide C=O bond.

For the activation and transformation of an inert amide group, electrophilic metal carbenes have been employed to react with nucleophilic carbonyl groups of amides to form the corresponding carbonyl ylides, which in turn can generally undergo cycloadditions to build important cycloaddition products28,29,30,31 or condense to form epoxides for further transformations in rare cases17,18,19,21,22 (Fig. 1c). However, DMF has rarely been used in transition metal-catalysed carbene-transfer reactions so far19,20,32,33, probably owing to the catalyst inhibition by coordination with the metal centre (such as axial coordination with dirhodium catalyst)34,35,36. Furthermore, in transition metal-catalysed difunctionalization of diazo compounds via metal carbenoid intermediates37,38,39,40,41,42 (Fig. 1d), carbene species usually acts as a formal C1 synthon to be incorporated into the coupling partners to access one-carbon-expanded homologation products43,44,45,46. The reconstruction of the molecular skeleton of a carbene species along with the functionalization of the carbenic carbon is quite appealing, but remains largely unexplored so far21,22,47,48.

Herein, we report a serendipitously discovered three-component reaction of α-diazocarbonyl compound with an allylic substrate and DMF using a dirhodium(II)/Xantphos or dirhodium–palladium dual catalytic system, which is effective for transferring of the ‘O’ of the formamide to the carbenic carbon and insertion of the aminomethine moiety into the carbene α C–C bond, respectively, thus furnishing a large diversity of extensively rearranged products with high efficiency (Fig. 1e). A wide variety of α-diazocarbonyl compounds, formamides and allylic electrophiles were applicable in this protocol, to deliver the corresponding highly functionalized α-aminoketone derivatives in one pot. In the case of cyclic diazo substrates, the reactions delivered the corresponding products with a ring-expanded moiety. More importantly, synthetically attractive cyclopentenone derivatives, which are structural motifs prevalent in natural product skeletons and synthetic intermediates49,50, have been produced directly in this three-component reaction through a six-step domino process starting from α-diazoketones, allowing a rapid forge of four new bonds in one pot, and opening up a new avenue for building up molecular complexity from simple materials.

Results and discussion

Reaction development

In our initial studies, it was found by serendipity that the cross-coupling reaction of diazo compound 1a and allylic substrate 2a using Rh2(OAc)4/Xantphos catalytic system in DMF as solvent afforded two unexpected products 4a (66%) and its isomer 5a (6%) (Table 1, entry 1)51,52. Nuclear magnetic resonance analysis of 4a showed that this compound has the composition corresponding to cleavage of the C=O bond in DMF with ‘O’ being transferred onto the carbene carbon. Moreover, the aminomethine moiety of DMF was inserted into the carbene-carbonyl bond, followed by an allylation. In the structure of 5a, the dimethylamino group of DMF was found to be inserted into the carbene–phenyl bond. Changing Rh2(OAc)4 to Rh2(Oct)4 led to similar results, while using Rh2(esp)2 gave a slightly lower yield of 4a (entries 2 and 3). The reactions using Rh(I) or Rh(III) also gave the same products, albeit in much inferior yields (entries 4 and 5). To our delight, increasing the loading of Xantphos to 10.0 mol% together with 2.0 mol% Rh2(OAc)4 as the catalyst gave the product 4a in 80% yield (entry 6). Other bisphosphine ligands, such as Cy-Xantphos, DPPF and DPPB were also tested; however, the reactions gave inferior yields of 4a (13–76%, entries 7–9) than that using Xantphos. Without a phosphine ligand, the reaction afforded product 4a in only 15% yield (entry 10).

Reaction scope

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, the generality of this reaction was explored (Fig. 2). The scope of different acyclic diazo esters was examined in the reactions with 2a in DMF (Fig. 2a). Diazo compounds with either electron-donating (p-Me, p-tBu-, p-OMe, p-OBn, o-Me, m-Me and m-OMe) or electron-withdrawing groups (p-F, p-Cl, p-Br o-Br and m-I) on the benzene ring performed well, affording the corresponding products 4a–m smoothly in moderate yields (44–86%). Additionally, for meta, para-dichloro-substituted, 3,5-difluorine substituted phenyl, α-naphthyl and [1,3]-dioxonyl diazo substrates, the reactions also furnished the desired products 4n–q in moderate yields (48–66%). The reaction of the diazo compound bearing a thienyl motif also provided the corresponding product 4r in 64% yield. However, the reactions using alkyl diazo esters failed to give the desired products. When a series of N,N-dialkyl substituted formamides 3 was used in THF (Fig. 2b), the reactions afforded the desired products 4ab–ad in 46–69% yields. Moreover, N,N-dibenzyl formamide and N-aryl formamide smoothly afforded the desired products 4ae–ai in 36–80% yields. The formamides with cyclic amine moieties were also found reactive in the protocol, providing the corresponding products 4aj–al in 30–71% yields. The reactions using formamide (HCONH2) or N-methylformamide failed to give the desired products under the standard reaction conditions.

a–c, The scope of α-diazo esters (a), formamides (b) and allylic substrates (c). d, Late-stage functionalization of complex architectures. e, Ring expansion reaction. Unless noted otherwise, the reaction conditions are as follows: a1 or 8 (0.20 mmol), 2 (0.30 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), DMF 3a (2.0 mL), Rh2(OAc)4 (2.0 mol%), Xantphos (10 mol%), 80 °C, 9.0 h. b3 (0.8 mmol, 4.0 equiv.), THF (2 mL), 80 °C. c100 °C. dMeCN (1 ml). eRh2(OAc)4 (2.0 mol%), Xantphos (10 mol%), Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%), 80 °C, 9.0 h. Isolated yields by column chromatography. The red stars mark the transfer of the carbon atom of the amide carbonyl group. n.d., not detected.

Allylic carbonates 2 with a 1-aryl or 1-alkyl substituent were further investigated; however, all the attempts failed to afford the desired products or gave very low yields under the standard reaction conditions, which might be owing to the low activity of the Rh(II)/Xantphos system towards the activation of substituted allylic substrates. Considering that Pd catalysts were often used to activate allylic electrophiles via the formation of allylic Pd intermediates, Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%) was used as a co-catalyst in the reactions of 1a and DMF with various substituted allylic substrates, and the three-component products 6 were generated smoothly in moderate yields (Fig. 2c). For various aromatic allylic esters bearing different functional groups on the phenyl ring and 3-furyl and 2-benzothienyl allylic carbonates, the reactions provided the corresponding products 6ab–ao in moderate yields (44–76%; for details, see Supplementary Materials 19–26). Furthermore, aliphatic allylic carbonates were also explored, with substrates bearing Bn, longer alkyl chains, t-Bu or cyclohexyl-substituents, providing the corresponding products 6ap–as in moderate yields (51–60 yields). For 2-methyl-substituted substrate 2t, the reaction proceeded smoothly to give the product 6at with a yield of 64%. Notably, using 3-phenyl allylic substrate, the reaction gave the same product as that using 1-phenyl allylic carbonate, indicating that π-allylic-Pd species was involved in the reactions.

Late-stage modification of complex architectures

To further demonstrate the applicability of the current catalysis, some derivatives of bio-relevant molecules bearing an α-diazo ester moiety, such as d-menthol, geraniol, β-citronellol and dehydroepiandrosterone, were subjected to the protocol under the standard reaction conditions (Fig. 2d). To our delight, these compounds were found to react smoothly with 2a in DMF, to afford 7a–d in moderate to good yields (52–90%). Furthermore, α-diazo esters derived from market drugs tiratricol and isoxepac also reacted smoothly with 2a in DMF, to deliver the desired products 7e and 7f in 51% and 73% yields, respectively. The structure of the product 7d was confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis.

Ring expansion reaction

Notably, the use of cyclic diazo reagents 8 could lead to one-carbon expanded ring products, with the dimethylaminomethine group of DMF being inserted into the ring system (Fig. 2e). The reaction of 8a and 2a in DMF afforded the ring expansion product 9a in high yield (84%). In this case, the original five-membered 2-indolone unit was inserted by an aminomethine moiety together with an oxygen transposition from DMF to form a six-member ring. The corresponding six-membered lactams 9b–e were obtained in good yields (73–94%) with different substituent groups on the N-atom and aryl groups. Furthermore, we attempted to challenge the synthesis of seven- and eight-membered rings by this ring expansion strategy. Six-membered diazolactones 8f–k underwent the reactions with 2a and DMF smoothly, providing the corresponding seven-membered ring products 9f–k in moderate to good yields (56–81%). The diazolactones with a –OMe, –F or –Cl substituent on the aryl group were well tolerated; thus the procedure provided a good platform for the synthesis of seven-membered rings. The expansion of seven-membered cyclic diazo compound 8l was also tested, and the reaction afforded the eight-membered lactone 9l in 20% yield. The structure of the product 9f was confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis.

Direct access to functionalized cyclopentenones

Cyclopentenones are important structural motifs not only as versatile synthetic intermediates but also as structural motifs in many bioactive natural molecules49,50. Nazarov cyclization of divinyl ketones is among the most straightforward and commonly used methods to access this attractive core53,54,55,56. In this context, the use of unconventional substrates for access to the divinyl ketone precursors attracts great attention since it can substantially increase the structural diversity of cyclopentenone derivatives. As shown in Fig. 3a, when α-diazoketone 10a was submitted to react with allylic substrate 2a in DMF using Rh2(esp)2/Xantphos, a functionalized cyclopentenone 11a with an enamine moiety and a 5-hydroxy group was isolated in 76% yield with high diastereomer ratio (d.r.) (>20/1 d.r.). For the reactions of analogous α-diazoketones, both electron-rich and electron-deficient aryl groups were well tolerated, providing the corresponding products 11b–e in moderate to high yields (49–82%). The chlorine and 3,5-disubstituted –OBn groups remained intact under the reaction conditions, thus providing good functional handles for downstream transformations (11f–j). Furthermore, diazo substrates bearing an [1,3]-dioxony, α-naphthyl or heteroaryl (furyl- and thienyl-) were amenable to the reaction (11k–o). Aliphatic diazo substrates with an adamantyl or cyclopropyl group were also tolerated in the reaction, giving the corresponding cyclopentenones 11p and 11q in moderate yields (64% and 40%, respectively). To our delight, in the presence of a catalytic amount of Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%), substituted allylic substrates were also amenable to the reaction conditions and introduced further functional groups on the alkenyl site of the products, thus leading to the formation of highly substituted cyclopentenones (Fig. 3b). A diversity of important substituents on the phenyl of the allylic substrates, including MeO, CF3, F, Br and ester moieties, were compatible with the reaction (12c–h, 58–84% yield). The reactions of allyl substrates bearing a 2-naphthyl, biphenyl, 3-furyl and 2-benzothienyl also proceeded well to provide corresponding products 12i–l in 57–70% yields. Additionally, aliphatic allylic carbonates were also found suitable substrates for the transformation, since Bn, longer alkyl chains, cyclopentyl- and cyclohexyl-substituted substrates worked well in the reaction, giving products 12m–q in moderate yields (47–75%). The structure of product 12p was further established by X-ray crystallographic analysis, confirming the presence of the substituted group on the alkenyl site. Interestingly, the reaction of allylic carbonate derived from a market drug gemfibrozil57, can also proceed smoothly to deliver the desired product 12r in 67% yield. Furthermore, allylic carbonates with a 2-alkyl, phenyl, vinyl or even phenylethynyl substituent were compatible with the reaction, giving 4,4′-disubstituted cyclopentenones 12s–v in 59–72% yields with two contiguous quarternary carbon centres. Gratifyingly, 1,2- or 1,3-disubstituted allylic carbonates were also compatible with the protocol, to provide 12w and 12x successfully in 51% and 58% yield, respectively. Notably, the reaction using ethyl diazoacetate as the diazo substrate under the standard conditions gave an α-H migration and di-allylation product in 64% yield (Supplementary Materials 58).

a,b, The scope of α-diazoketone compounds (a) and allylic substrates (b). Unless otherwise noted, the reaction conditions are as follows: a10 (0.20 mmol), 2a (0.30 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), DMF 3a (2.0 mL), Rh2(esp)2 (1.0 mol%), Xantphos (4 mol%), 80 °C, 9.0 h. bRh2(esp)2 (1.0 mol%), Xantphos (15 mol%), Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%), 80 °C, 9.0 h. Isolated yields were achieved by column chromatography. The red stars mark the transfer of the carbon atom of the amide carbonyl group.

The synthetic utility of this approach was further demonstrated in the reactions shown in Fig. 4. Gram-scale reaction of 1a and 2a in DMF proceeded smoothly, giving the desired product 4a in 72% yield. Treatment of 4a with 3-chloroperbenzoic acid resulted in a Cope elimination product 13 with 66% yield (Fig. 4a(i)). In addition, Pd/C-catalysed hydrogenation of 4a to compound 14 proceeded with 99% yield (Fig. 4a(ii)). The reductive carbon–nitrogen bond cleavage reaction of 4a, followed by a propargylation via two steps afforded product 15 with 52% yield with an all-carbon quaternary centre (Fig. 4a(iii)). Acidic hydrolysis of the ester 4a followed by an intramolecular lactonization, led to the formation of γ-butyrolactone 16 with 43% yield (Fig. 4a(iv)). Furthermore, a Pd-catalysed Heck coupling reaction of 4a with an aryl iodine 17 derived from a pharmaceutical molecule empagliflozin, providing compound 18 in 46% yield (Fig. 4a(v)). Interestingly, a copper-catalysed intermolecular trifluoromethylation of 4a provided a polysubstituted tetralone derivative 19 (Fig. 4a(vi)). The synthetic utility of 11d was also explored in Fig. 4b. A gram-scale reaction of 10d and 2a in DMF proceeded smoothly to give a good yield (1.03 g, 77%) of the desired product 11d, which was esterified to 21 in 84% yield via a reaction with (1S)-(−)-camphanic acid chloride 20. Acidic hydrolysis of 11d afforded a 93% yield of the corresponding 2-hydroxy cyclopentenone 22, which in turn was further transformed into quinoxaline 24 by condensation with 1,2-phenylenediamine 23, or derivatized to a bicyclic product 26 via an organocatalytic Michael addition–cyclization cascade with α,β-unsaturated aldehyde 25. In addition, treatment of 22 with SOCl2 afforded a Cl substitution product 27 with 66% yield. Finally, treatment of 22 with Tf2O, followed by a Pd-catalysed coupling with PhB(OH)2 provided an arylated product 28 with 74% yield.

Mechanistic investigations

To elucidate the reaction mechanism, several types of isotope-labelling experiments were carried out, to probe the roles of DMF in this transformation (Fig. 5a). The reaction with DMF-formyl-13C as a reactant gave 4a-13C with 66% yield with 99% 13C incorporation of the quaternary carbon (Fig. 5a(i)), showing that the quaternary carbon atom of 4a-13C originated from the carbonyl group of DMF. When the reaction was performed in the presence of 18O-DMF (81% enrichment), the incorporation of 4a-18O product was also observed (Fig. 5a(ii)). In contrast, the addition of 2.0 equiv of H218O completely inhibited the reaction (Fig. 5a(iii)). These results indicated that the O atom of carbonyl group of 4a was from DMF, rather than that from trace amount of (ineluctable) H2O present in the reaction system. The reaction using DMF-d7 gave the product 4a-D-6 (Fig. 5a(iv)), wherein the full incorporation of deuterium was observed at the two methyl groups, suggesting that aminomethine moiety of DMF was fully transferred into the final product. More control experiments were conducted to investigate the two-component reactions of 1a and DMF (Fig. 5b). Treatment of 1a in DMF under the standard conditions gave the corresponding two-component coupling product 29a in similar yields (84% and 87%) with or without Xantphos ligand. Notably, the product 29a can also be generated in 51% yield when treating 1a in DMF with blue light-emitting diode (LED) irradiation in the absence of any catalysts, suggesting that even a transition metal catalyst is not necessary for the coupling and rearrangement of DMF with carbene moiety under appropriate photochemical conditions. Furthermore, treatment of 29a with allylic substrate 2a under the standard conditions afforded the target product 4a with 80% yield. Under otherwise identical conditions, no allylic alkylation of 29a occurred in the absence of the Xantphos ligand. These results suggested that the current three-component reaction is a relay catalytic process, for example, two-component coupling-rearrangement of a diazo compound and DMF, followed by an allylic alkylation to generate the final product bearing a quaternary carbon centre. The role of Xantphos ligand in the titled reaction is likely to promote the Rh(II)-catalysed allylic alkylation reaction of the rearranged intermediate 29a with allylic substrate 2a, probably activated by the dirhodium core with a bidentately coordinated Xantphos51. To detect the possible carbonyl ylide intermediate between the reaction of 1a and DMF, dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate and 1a were allowed to react in DMF using Rh2/Xantphos catalytic system, and the proposed 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition product 30 was detected by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). However, attempts to isolate this product or detect it by 1H-nuclear magentic resonance failed, probably owing to the instability of this species. Control experiments have also been performed on the process for the generation of functionalized cyclopentenones (Fig. 5c). Under the standard conditions, the reaction of diazo compound 10a in DMF afforded the coupling product 31a, which reacted further with allylic substrate 2a to give the cyclopentenone 11a in 75% yield. These two-step reactions also suggested that the overall transformation is probably a relay catalytic process. Notably, the reaction of 31a with allylic bromide gave O-allylated product 32a, which can be transferred to the final product in 95% yield at 80 °C without Rh(II)/Xantphos, indicating that the cyclization reaction is an uncatalyzed process. Furthermore, the addition of D2O to the cyclization reaction of 32 afforded the deuterated 11a-D with a CH2D group, suggesting that a protonation process should be involved in the reaction.

a, Isotope-labelling reactions. b, Control experiments for the generation of 4a. c, Control experiments for the generation of 11a. For detailed reaction conditions, see Supplementary Materials 71–82. The red stars mark the transfer of the carbon atom of the amide carbonyl group. r.t., room temperature.

To gain a deeper understanding of the detailed mechanism underlying C–C bond rearrangement and oxygen transposition, we conducted density functional theory (DFT) calculations on the reaction of 1a and DMF (Fig. 6a; for computational details see Supplementary Materials 82–108). Initially, substrate 1a coordinates axially to one Rh centre of the Rh2 catalyst via its axial site, forming the complex Rh-INT1 with an endergonic energy change of 4.5 kcal mol−1. Subsequently, the expulsion of N2 occurs through the transition state Rh-TS1 with an barrier of 15.9 kcal mol−1, leading to the formation of a Rh-carbene species Rh-INT2 (refs. 58,59). The dissociation of the Rh catalyst from Rh-INT2 to generate a free carbene is energetically unfavourable, exhibiting a high barrier (Supplementary Fig. 10A). The subsequent step involves the attack of one molecule of DMF on the intermediate Rh-INT2 via Rh-TS2, surmounting an energy barrier of 17.0 kcal mol−1, producing a carbonyl ylide intermediate Rh-INT3. This step is consistent with the general reactivity of amide groups with electrophilic carbenes29,30. However, a Rh-bound cyclization from Rh-INT3 to form an amino epoxy intermediate INT2 was found to require a high energy barrier of 27.5 kcal mol−1 via Rh-TS3 (Supplementary Fig. 10A). Instead, a catalyst-free cyclization via TS3 (ΔG⧧ = 17.2 kcal mol−1) is more favourable. This is also consistent with the experimental result of the transition metal-free reaction of 1a in DMF under blue LED. Notably, amino epoxy intermediates have been proposed in some reactions of carbenes with amide groups17,18,19,21,22. Finally, the amino epoxy intermediate INT2 undergoes a dyotropic type rearrangement60,61 via 1,2-ester group transfer62 with a barrier of 22.6 kcal mol−1 via TS4b, resulting in the formation of the product 29a. As a comparison, phenyl group transfer was also investigated, and it was found to be unfavourable owing to its higher activation free energy (TS4a: ΔG⧧ = 24 kcal mol−1). These findings are consistent with the product selectivity of the experimental outcomes. The dyotropic type rearrangement, triggered by the 1,2-ester group transfer, is the rate-determining step in the overall reaction, with an overall free energy barrier of 26.2 kcal mol−1. On the basis of the experimental and DFT studies, a tentative mechanism for this relay catalysis is proposed in Fig. 6b. First, [Rh(II)2] catalyses the carbene reaction with DMF, to give an amino epoxy intermediate INT2 via intramolecular cyclization of a carbonyl ylide intermediate. This is followed by a dyotropic type rearrangement of INT2, proceeding preferentially via 1,2-ester group transfer to provide compound 29. Finally, a Xantphos coordinated dirhodium catalysed allylic alkylation of 29 with allylic electrophile 2a or Pd-catalysed allylic alkylation of 29 with substituted allylic substrates occurred, thus leading to the formation of the three-component product 4. When α-diazoketone 10 was applied, the corresponding product 29 would undergo a ketone–enol tautomerism to form the intermediate 31, which was O-allylated by the allylic electrophile to give intermediate 32. Under heating conditions, a Claisen rearrangement can occur to give 33 and the following isomerization will afford the key cyclization precursor 34. Finally, the stereospecific Nazarov cyclization of 34 gives the functionalized cyclopentenones.

a, DFT calculations. b, Mechanistic proposal. The Gibbs free energy profile for Rh(II)2-catalysed coupling and rearrangement of diazo ester 1a with DMF at the PBE0-D3(BJ)/6-311 + G(d,p)-SDD(Rh)-SMD(DMF)//B3LYP/6-31 G(d)-LANL2DZ(Rh)-SMD(DMF) level of theory. Relative Gibbs free energies are presented in kilocalorie per mole. Geometric structures of relative transition states are presented in ångstroms (Å). The red stars mark the transfer of the carbon atom of the amide carbonyl group.

Conclusion

A dirhodium/Xantphos or dirhodium–palladium dual catalysed three-component reaction of diazo compounds, allylic electrophiles and DMF was disclosed to afford a wide variety of highly functionalized tertiary amine products. Notably, a large diversity of diazo esters, formamides and allylic substrates can be applied in this reaction, providing a variety of interesting molecules with an extensively rearranged skeleton, including α-aminoketones, ring-extended structures and cyclopentenones, in a highly atom-economical and step-efficient way. Combined experimental mechanistic investigation and DFT calculations suggested that a dyotropic type rearrangement of the in situ formed amino epoxy intermediate is the key for the current catalytic Domino process.

Methods

Rh2(OAc)4 (1.77 mg, 4.0 х 10−3 mmol, 2.0 mol%), Xantphos (11.6 mg, 2.0 × 10−2 mmol, 10.0 mol%) or Rh2(esp)2 (1.53 mg, 2.0 × 10−3 mmol, 1.0 mol%), Xantphos (4.62 mg, 8.0 × 10−3 mmol, 4.0 mol%) and anhydrous DMF (2.0 mL) were added to a sealed tube equipped with a magnetic stir bar under dry argon atmosphere. Then, diazo 1 (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and allyl methyl carbonate 2 (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv) were sequentially introduced using a syringe. The mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 8–10 h. Purification was performed using flash column chromatography on silica gel to afford the desired product. Pd(OAc)2 (4.50 mg, 2.0 × 10−2 mmol, 10.0 mol%) was added as a co-catalyst when a substituted allylic carbonate was used.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the Article and its Supplementary Information. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC 2295376 (5a), 2295374 (7d), 2295375 (9f), 2305221 (11e), 2351661 (12p), 2295377 (19), 2350726 (27) and 2305222 (31). These data are available via the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre at https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/.

References

Tietze, L. F. Domino reactions in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 96, 115–136 (1996).

Lu, L.-Q., Chen, J.-R. & Xiao, W.-J. Development of cascade reactions for the concise construction of diverse heterocyclic architectures. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 1278–1293 (2012).

Bai, L. & Jiang, X. Catalytic domino reaction: a promising and economic tool in organic synthesis. Chem Catal. 3, 100752 (2023).

Volkov, A., Tinnis, F., Stagbrand, T., Trillo, P. & Adolfsson, H. Chemoselective reduction of carboxamides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 6685–6697 (2016).

Cabrero-Antonino, J. R., Adam, R., Papa, V. & Beller, M. Homogeneous and heterogeneous catalytic reduction of amides and related compounds using molecular hydrogen. Nat. Commun. 11, 3893–3910 (2020).

Huang, P. Direct transformations of amides: tactics and recent progress. Acta Chim. Sinica 76, 357–365 (2018).

Li, G., Ma, S. & Szostak, M. Amide bond activation: the power of resonance. Trends Chem. 2, 914–928 (2020).

Kaiser, D., Bauer, A., Lemmerer, M. & Maulide, N. Amide activation: an emerging tool for chemoselective synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 7899–7925 (2018).

Dander, J. E. & Garg, N. K. Breaking amides using nickel catalysis. ACS Catal. 7, 1413–1423 (2017).

Feng, M., Zhang, H. & Maulide, N. Challenges and breakthroughs in selective amide activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e20221221 (2022).

Wu, Z., Xu, X., Wang, J. & Dong, G. Carbonyl 1,2-transposition through triflate-mediated α-amination. Science 374, 734–740 (2021).

Shennan, B. D. A., Sánchez-Alonso, S., Rossini, G. & Dixon, D. J. 1,2-Redox transpositions of tertiary amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 21745–21751 (2023).

Li, J., Huang, C.-Y. & Li, C.-J. Deoxygenative functionalizations of aldehydes, ketones and carboxylic acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202112770 (2022).

Muzart, J. N,N-Dimethylformamide: much more than a solvent. Tetrahedron 65, 8313–8323 (2009).

Ding, S. & Jiao, N. N,N-Dimethylformamide: a multipurpose building block. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 9226–9237 (2012).

Bras, J. L. & Muzart, J. Recent uses of N,N-dimethylformamide and N,N-dimethylacetamide as reagents. Molecules 23, 1939–1969 (2018).

Priebbenow, D. L. & Bolm, C. The rhodium-catalysed synthesis of pyrrolidinone substituted (trialkylsilyloxy)acrylic ester. RSC Adv. 3, 10318–10322 (2013).

Li, Q. et al. Rhodium-catalyzed formal C=O bond insertion and sequential acyl 1,4-N-to‑O migratory rearrangement. J. Org. Chem. 87, 16937–16940 (2022).

Nandra, G. S., Pang, P. S., Porter, M. J. & Elliott, J. M. Synthesis of vinylogous carbamates by rhodium(II)-catalyzed olefination of tertiary formamides with a silylated diazoester. Org. Lett. 7, 3453–3455 (2005).

Jung, D. J., Jeon, H. J., Kim, J. H., Kim, Y. & Lee, S.-G. DMF as a source of oxygen and aminomethine: stereoselective 1,2-insertion of rhodium(II) azavinyl carbenes into the C=O bond of formamides for the synthesis of cis-diamino enones. Org. Lett. 16, 2208–2211 (2014).

Goudedranche, S., Besnard, C., Egger, L. & Lacour, J. Synthesis of pyrrolidines and pyrrolizidines with α-pseudoquaternary centers by copper-catalyzed condensation of α-diazodicarbonyl compounds and aryl γ-lactams. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 13775–13779 (2016).

Tan, F. et al. Chiral Lewis acid catalyzed reactions of α-diazoester derivatives: construction of dimeric polycyclic compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 16176–16179 (2018).

Miura, T., Funakoshi, Y., Tanaka, T. & Murakami, M. Direct production of enaminones from terminal alkynes via rhodium-catalyzed reaction of formamides with N-sulfonyl-1,2,3-triazoles. Org. Lett. 16, 2760–2763 (2014).

Mukherjeea, A. et al. Synthesis of α-amino carbonyl compounds: a brief review. Russ. Chem. Rev. 92, RCR5046 (2023).

Allen, L. A. T., Raclea, R. C., Natho, P. & Parsons, P. J. Recent advances in the synthesis of α-amino ketones. Org. Biomol. Chem. 19, 498–513 (2021).

Fisher, L. E. & Muchowski, J. M. Synthesis of α-aminoaldehydes and α-aminoketones. A review. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 22, 399–484 (1990).

Wu, W., Chen, C., Peng, J. & Li, Z. Research progress of carbonyl α-position amination. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 43, 2743–2763 (2023).

Padwa, A. Domino reactions of rhodium(II) carbenoids for alkaloid synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 3072–3081 (2009).

Hashimoto, T. & Maruoka, K. Recent advances of catalytic asymmetric 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions. Chem. Rev. 115, 5366–5412 (2015).

Padwa, A. Catalytic decomposition of diazo compounds as a method for generating carbonyl-ylide dipoles. Helv. Chim. Acta 88, 1357–1374 (2005).

Padwa, A. Intramolecular cycloaddition of carbonyl ylides as a strategy for natural product synthesis. Tetrahedron 67, 8057–8072 (2011).

Ning, Y. et al. Rhodium(II) acetate-catalysed cyclization of pyrazol-5-amineand1,3-diketone-2-diazo compounds using N,N-dimethylformamide as a carbon-hydrogen source: access to pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridines. Adv. Synth. Catal. 361, 3518–3524 (2019).

Ba, D. et al. Rhodium(II)-catalyzed multicomponent assembly of α,α,α-trisubstituted esters via formal insertion of O–C(sp3)–C(sp2) into C–C bonds. Nat. Commun. 11, 4219–4224 (2020).

Trindade, A. F., Coelho, J. A. S., Afonso, C. A. M., Veiros, L. F. & Gois, P. M. P. Fine tuning of dirhodium(II) complexes: exploring the axial modification. ACS Catal. 2, 370–383 (2012).

Hong, B., Shi, L., Li, L., Zhan, S. & Gu, Z. Paddlewheel dirhodium(II) complexes with N-heterocyclic carbene or phosphine ligand: new reactivity and selectivity. Green Synth. Catal. 3, 137–149 (2022).

Wynne, D. C., Olmstead, M. M. & Jessop, P. G. Supercritical and liquid solvent effects on the enantioselectivity of asymmetric cyclopropanation with tetrakis[1-[(4-tert-butylphenyl)-sulfonyl]-(2S)-pyrrolidinecarboxylate]dirhodium(II). J Am Chem Soc 122, 7638–7647 (2000).

Guo, X. & Hu, W. Novel multicomponent reactions via trapping of protic onium ylides with electrophiles. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 2427–2440 (2013).

Xiao, Q., Zhang, Y. & Wang, J. Diazo compounds and N-tosylhydrazones: novel cross-coupling partners in transition-metal-catalyzed reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 236–247 (2013).

Xia, Y., Qiu, D. & Wang, J. Transition-metal-catalyzed cross-couplings through carbene migratory insertion. Chem. Rev. 117, 13810–13889 (2017).

Doyle, M. P., McKervey, M. A. & Ye, T. Modern Catalytic Methods for Organic Synthesis with Diazo Compounds (Wiley, 1998).

Davies, H. M. L. & Denton, J. R. Application of donor/acceptor-carbenoids to the synthesis of natural products. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 3061–3071 (2009).

Ford, A. et al. Modern organic synthesis with α-diazocarbonyl compounds. Chem. Rev. 115, 9981–10080 (2015).

Liu, Z., Sivaguru, P., Ning, Y., Wu, Y. & Bi, X. Skeletal editing of (hetero)arenes using carbenes. Chem. Eur. J. 29, e202301227 (2023).

Moebius, D. C., Rendina, V. L. & Kingsbury, J. S. Catalysis of diazoalkane–carbonyl homologation. How new developments in hydrazone oxidation enable a carbon insertion strategy for synthesis. Top. Curr. Chem. 346, 111–162 (2014).

Candeias, N. R., Paterna, R. & Gois, P. M. P. Homologation reaction of ketones with diazo compounds. Chem. Rev. 116, 2937–2981 (2016).

Padwa, A. & Hornbuckle, S. F. Ylide formation from the reaction of carbenes and carbenoids with heteroatom lone pairs. Chem. Rev. 91, 263–309 (1991).

Li, M. et al. Copper-catalyzed carbene insertion and ester migration for the synthesis of polysubstituted pyrroles. Chem. Commun. 56, 11050–11053 (2020).

Luo, K. et al. Highly regioselective synthesis of multisubstituted pyrroles via Ag-catalyzed [4+1C]insert cascade. ACS Catal. 10, 3733–3740 (2020).

Jose, J. & Mathew, T. V. Recent advances in the synthesis of 2-cyclopentenones. Tetrahedron 150, 133747–133770 (2024).

Zhou, Z., Dixon, D. D., Jolit, A. & Tius, M. A. The evolution of the total synthesis of rocaglamide. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 15929–15936 (2016).

Lu, B. et al. Dirhodium(II)/Xantphos-catalyzed relay carbene insertion and allylic alkylation process: reaction development and mechanistic insights. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 11799–11810 (2021).

Yang, Y., Lu, B., Xu, G. & Wang, X. Overcoming O–H insertion to para-selective C–H functionalization of free phenols: Rh(II)/Xantphos catalyzed geminal difunctionalization of diazo compounds. ACS Cent. Sci. 8, 581–589 (2022).

Frontier, A. J. & Hernandez, J. J. New twists in Nazarov cyclization chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1822–1832 (2020).

Wenz, D. R. & Alaniz, J. R. d. The Nazarov cyclization: a valuable method to synthesize fully substituted carbon stereocenters. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 23–37 (2014).

Grandi, M. J. D. Nazarov-like cyclization reactions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 12, 5331–5345 (2014).

Vaidya, T., Eisenberg, R. & Frontier, A. J. Catalytic Nazarov cyclization: the state of the art. ChemCatChem 3, 1531–1548 (2011).

Tornio, A., Neuvonen, P. J., Niemi, M. & Backman, J. T. Role of gemfibrozil as an inhibitor of CYP2C8 and membrane transporters. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 13, 83–95 (2017).

Berry, J. The role of three-center/four-electron bonds in superelectrophilic dirhodium carbene and nitrene catalytic intermediates. Dalton Trans. 41, 700–703 (2012).

Werlé, C., Goddard, R., Philipps, P., Farès, C. & Fürstner, A. Structures of reactive donor/acceptor and donor/donor rhodium carbenes in the solid state and their implications for catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 3797–3805 (2016).

Cao, J., Wu, H., Wang, Q. & Zhu, J. C–C bond activation enabled by dyotropic rearrangement of Pd(IV) species. Nat. Chem. 13, 671–676 (2021).

Fernandez, I., Cossio, F. P. & Sierra, M. A. Dyotropic reactions: mechanisms and synthetic applications. Chem. Rev. 109, 6687–6711 (2009).

Bach, R. D. & Domagala, J. M. The effect of Lewis acid and solvent on concerted 1,2-acyl migration. J. Org. Chem. 49, 4181–4188 (1984).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the National Key Research and Development Programme of China (grant no. 2021YFA1500100), the Strategic Priority Research Programme of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant nos XDB0610000 and XDB0590000), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos 92256303, 22171278, 22122104, 22193012 and 21933004), the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (grant no. 23ZR1482400), the Natural Science Foundation of Ningbo (grant no. 2023J034), the Chinese Academy of Sciences Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research (grant nos YSBR-052 and YSBR-095), Open Research Fund of School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Henan Normal University and the Research Funds of Hangzhou Institute for Advanced Study, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (2024HIAS-p003). The numerical calculations in this study were carried out on the ORISE Supercomputer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.D. and X.W. conceived the project in collaboration with Y.L., who performed the experimental work and led primary data interpretation and analysis. G.H. and X.-S.X. performed all the computational studies and wrote the section with the calculations.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemistry thanks Rosa Adam, Jianbo Wang, Yanying Zhao and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–11 and Figs. 1–18, starting material preparation and experimental procedures, synthetic applications, mechanistic studies and product characterization.

Supplementary Data 1

Crystallographic data for compound 5a; CCDC reference 2295376.

Supplementary Data 2

Crystallographic data for compound 7d; CCDC reference 2295374.

Supplementary Data 3

Crystallographic data for compound 9f; CCDC reference 2295375.

Supplementary Data 4

Crystallographic data for compound 11e; CCDC reference 2305221.

Supplementary Data 5

Crystallographic data for compound 12p; CCDC reference 2351661.

Supplementary Data 6

Crystallographic data for compound 19; CCDC reference 2295377.

Supplementary Data 7

Crystallographic data for compound 27; CCDC reference 2350726.

Supplementary Data 8

Crystallographic data for compound 31a; CCDC reference 2305222.

Supplementary Data 9

Computational details and Cartesian coordinates.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, Y., Huang, G., Ding, K. et al. Oxygen transposition of formamide to α-aminoketone moiety in a carbene-initiated domino reaction. Nat. Chem. 17, 1196–1206 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-01834-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-01834-8